Introduction

There is a lack of scholarship on film production in Macau. Most aspects of the history of cinema in Macau are understudied, be it the production, reception, or, to a lesser extent, the image of Macau in cinema, which has received more attention.Footnote 3 Yet, although Macau did not have a film industry per se and filmic output was always small, film production was carried out in the territory throughout most of the twentieth century. Most production consisted in short documentary films made by people with links to the (colonial) government, which often received official support as well as some input from the neighbouring Hong Kong film industry, due to the lack of film professionals and facilities in Macau. The main objective was to propagate a positive image of Macau, in response to its pervasive negative portrayal in the international media and Western films, which often characterized it as a centre of vice. Official publications and the Portuguese press in Macau repeatedly protested against these depictions.

Furthermore, the 1950s were a period of crisis for the Portuguese regime and its colonial empire, as the post-war era saw the beginning of decolonization. Portugal was then run by the New State (Estado Novo, 1933–1974), a right-wing dictatorship whose policy was to preserve the colonies. These films were therefore also part of a larger effort to portray Portugal and its overseas territories in a positive way, as well as emphasize their unity at a time when Portugal was under increasing international pressure to decolonize. In the post-war period, the Portuguese government appropriated ‘Luso-tropicalism’, a theory developed by Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre (1900–1987), which argued that the Portuguese had created a harmonious hybrid civilization in the ‘tropics’ through both biological and cultural miscegenation. Luso-tropicalism became one of the main propaganda tools used to deflect decolonization.

Long Way (dir. Eurico Ferreira, Reference Ferreira1955), made by Macau's Eurasia Film Company, was the first full-length fiction film produced and shot in Macau. Eurasia presented a Luso-tropical ideal not only in terms of the film's subject matter, which celebrated interracial love, but also in terms of the company's very nature—a Sino-Portuguese enterprise that also had Eurasians as shareholders—and in its production method. Long Way featured a multi-ethnic crew and cast that included Portuguese, Chinese, and Eurasians, and the film was a multi-lingual one, with actors speaking Portuguese, Chinese, and English.Footnote 4 The film was released in 1955 but was subsequently lost, so this analysis mostly relies on untapped primary sources, such as contemporary press reports and archival materials in Portuguese, Chinese, French, and English; it simultaneously relates Long Way to the socio-political contexts of Macau, Portugal, and China during this period.

This article hence explores the film's production by placing it within its overall context. It first examines the pressures and anxiety of decolonization felt by Portugal in the post-war era and the discourses circulating about Macau which shaped the films that were made, including Long Way. It then turns to film production in Macau by discussing the making of the film and also addresses Long Way as a direct response to some prominent Western films set in Macau that portrayed a mainly negative image of the territory. Finally, it examines that project's engagement with politics, including the cultural Cold War in Asia and the 400 Years celebration of the anniversary of the establishment of the Portuguese in Macau, which was meant to affirm Portuguese sovereignty in the territory but received strong condemnation from China.

Long Way's overall message and production methods are representative of a filmic pattern that continued throughout the New State period, consisting in an effort to depict Macau positively and often through a Luso-tropical lens, in response to international criticism and with the aim of cleansing the territory's image and thereby justifying Portuguese rule in Macau in a period of crisis and uncertainty.

The anxiety of decolonization and Luso-tropicalism

Although the post-war period ushered in the beginning of decolonization, Portugal refused to contemplate it, despite increasing international pressure, including from the United Nations (UN) which upheld self-determination for colonized people. In 1951 the New State changed the status of the colonies—consisting of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea, the islands of Cape Verde and Sao Tome and Principe in Africa, and Portuguese India, Macau, and Timor in Asia—to ‘Overseas Provinces’, thereby making them an integral part of the nation. Portugal thus presented itself as a pluri-continental and multiracial nation to deflect international pressure.

Some opposition to Portuguese rule in the African colonies began to surface in the 1940s and 1950s (Brookshaw Reference Brookshaw, Poddar, Patke and Jensen2008, 445). India became independent in 1947 and claimed Portuguese India. Then in 1954 it annexed the Portuguese enclaves of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, signalling ‘the beginning of the end’ (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 125) for the Portuguese empire and exacerbating the sense of crisis. In that same year the UN condemned colonialism in all its manifestations (Gupta Reference Gupta2019, 14).Footnote 5 In the mid-1950s, the international situation became even more challenging for Portugal, as ‘gradually the European colonial empires in Africa began to disappear. The so-called third world emerged and became a decisive actor in international relations with the Bandung Conference in 1955, the general condemnation of colonialism, and the global Cold War’ (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues, Jerónimo and Pinto2015, 244). In 1955, Portugal was accepted into the UN, yet the latter ‘put colonies in general, and Portuguese colonies in particular on the spot’ (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues, Jerónimo and Pinto2015, 244).

In order to justify its overseas possessions, Portugal adopted a simplified version of Luso-tropicalism in the post-war era. Gilberto Freyre developed this theory in several of his writings, which centred on the Portuguese having created a hybrid civilization overseas through miscegenation on both a biological and cultural level.Footnote 6 Freyre argued that the Portuguese had a unique capacity to fraternize and miscegenate with people in the colonies and to harmoniously embrace ‘tropical’ values while mixing them with European ones. He proposed that the Portuguese adapted to the ‘tropics’ better than other colonizers because of two main factors: one being geographical as Portugal was more like Africa than Europe, and the other being their intense mixing with Moors, Jews, and Africans since ancient times. According to Freyre (Reference Freyre and Putnam1946, 203), the fact that the Portuguese were ‘anthropologically and culturally a mixed people’ endowed them with a certain plasticity and flexibility. He defined Portuguese colonialism as Christocentric rather than ethnocentric, because the Portuguese saw themselves more as Christians than Europeans. He contrasted this with the Eurocentrism of other colonizers who maintained their identity as Europeans in their colonies, segregated themselves, and valued ethnic purity. Additionally, Freyre argued that, unlike the Portuguese, their motivation was mainly economic gain.

In her study on the reception of Freyre's ideas in Portugal, Cláudia Castelo (Reference Castelo1999) has argued that in the 1930s and 1940s they were not well received by the Portuguese regime, due to the prominence he gave to miscegenation and to Moorish and African legacies, though there was more receptivity in the cultural field and among intellectuals in the colonies. At the time, colonial discourse mostly focused on notions of a ‘civilizing mission’ and ‘imperial rejuvenation’. However, in the post-war era when the New State was confronted with a new world order, his concepts were increasingly appropriated into Portuguese colonial discourse. In 1951, the year when the status of the colonies was changed, Freyre accepted an invitation from Sarmento Rodrigues, the minister of the overseas, to tour Portugal and its Overseas Provinces. It was in a lecture given while visiting Goa in Portuguese India that Freyre (Reference Freyre1953b, 136) coined the term ‘Luso-tropicalism’ to characterize a new civilization that ‘harmonized Europe with the tropics without imperialism or violence’.Footnote 7 As Castelo (Reference Castelo1999) has argued, some of Freyre's ideas, particularly the Portuguese propensity to fraternize with non-Western people, had been inspired by earlier Portuguese writings, but he developed them into a theory in which miscegenation, hybridism, and the contribution of others towards a Luso-tropical civilization were given more prominence than in previous iterations.

Throughout the New State period, a diluted version of Luso-tropicalism, which focused more on the supposed lack of racial prejudice of the Portuguese and their capacity to fraternize with non-Western people, emerged. It was used as a propaganda tool by the regime in its attempt to maintain the status quo and convince the international community of the well-integrated, multi-racial entity formed by Portugal and its Overseas Provinces.

Freyre was among the most pre-eminent intellectuals in Brazil at the time and was also renowned worldwide. As a foreigner who seemed impartial, and furthermore one who enjoyed international prestige, he was particularly useful to the regime.Footnote 8 In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the government commissioned two books by Freyre.Footnote 9 With the onset of the Colonial War (1961–1974) in the Portuguese African colonies and in the face of more international criticism directed at Portugal, ‘abundant copies were distributed globally by the Portuguese Colonial Ministry [the Ministry of the Overseas]’ (Dávila Reference Dávila, Anderson, Roque and Santos2019, 65) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to foreign embassies and the UN as well to Portuguese embassies abroad to instruct diplomats about Luso-tropicalism. This indoctrination of diplomats had already begun in the mid-1950s.Footnote 10

There was a considerable gap, however, between Luso-tropicalism and reality, especially in most of the African territories where a legal distinction was made between white settlers, assimilated people, and ‘uncivilized people’, and forms of forced labour were instituted, which would only be repelled in 1961 (Alexandre Reference Alexandre and Vala1999, 143). Luso-tropicalism was therefore subjected to substantial criticism, especially from the mid-1950s onwards. It was first challenged by the anti-colonial leaders in the Portuguese African colonies, such as the Angolan Mário Pinto de Andrade who, in the 1950s, denounced the disparities between reality and theory (Castelo Reference Castelo1999, 42; Dávila Reference Dávila, Anderson, Roque and Santos2019, 67). In academia, the British historian Charles Boxer, a prominent specialist on the Portuguese empire, was among the first to dispute Luso-tropicalism. In 1961 he delivered a lecture at the British Academy entitled ‘The Colour Question in the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1825’, which was published later in the same year. Boxer (Reference Boxer1961, 113) began the lecture by alluding to Freyre (and his supporters), stating that ‘there is no lack of distinguished authorities who assure us that the Portuguese never had any colour-bar worth mentioning’. Boxer (Reference Boxer1961, 114) then proceeded to cite various examples from across the Portuguese empire before concluding that although ‘the Portuguese did mix more with coloured races than did other Europeans and they had, as a rule, less colour prejudice’, there was nevertheless a colour-bar which ‘assumed different forms at different times and places’.Footnote 11

In the past few decades, there have been reassessments of Luso-tropicalism and Freyre's overall oeuvre by scholars working on the Lusophone world who continue to point out the gap between reality and theory. The recent volume by Anderson, Roque and Santos (Reference Anderson, Roque, Santos, Anderson, Roque and Santos2019, 8) ‘tests the concept against racialized practices in the remnants of the Portuguese Empire’, demonstrating that there was a variety of racial conceptions and race mixing was not consensual.Footnote 12 Despite the flaws present in Freyre's theories and his instrumentalization by conservative regimes, his legacy is a mixed one. His writings were ambiguous, ever-evolving, and allow for various readings and appropriations. In the case of the Eurasians discussed later in this article, one objective of their appropriation of Freyre's theories may have been to call for a truer celebration of hybridity and a more egalitarian society in Macau.

Macau in the post-war era

In the post-war period, Macau faced a tense politico-economic situation and found itself under pressure from both the West and China. Following China's participation in the Korean War (1950–1953), the UN imposed an embargo on the country in 1951 which affected Macau's trade with China and its economy. The territory had a long history of being portrayed as a centre of vice, and its reputation worsened as it was frequently accused of violating the embargo by the international press, foreign governments, and COCOM (Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export), the organization responsible for controlling exports to the communist bloc, and later CHINCOM (China Committee), the subcommission responsible for China, North Korea, and North Vietnam, which were established in 1949 and 1952 respectively. In his memoir, Calvet de Magalhães (Reference Magalhães1992, 78), the Portuguese delegate to COCOM, reminisced about the constant complaints against Macau that were made by American and British representatives.

A number of damaging articles depicting Macau as a dangerous centre of vice and smuggling emerged at the time. A 1949 issue of Life magazine wrote about the omnipresence of smuggling, about opium dens and prostitution, and that the ‘ways’ of the ‘City of the name of God’ (part of Macau's official appellation) were ‘far from godly’ (Rowan Reference Rowan1949, 21). Time published two particularly damaging articles, one in 1951 describing Macau as a place addicted to smuggling ‘with custom officers who look the other way and businessmen who deal with anybody’ (Time 1951, 23) and another in 1953 stating that ‘Macau's legitimate industries are the packaging of materials, firecrackers and sin (and that) Portugal is pledged to enforce the UN embargo […] but Macau lives in such dependence on China that it considers it a question of smuggle or die’ (Time 1953, 27). In contrast, these reports applauded British authorities in Hong Kong by stating that they had reduced smuggling, unlike Macau.

Macau was also plagued by particularly tense Sino-Portuguese relations in the post-war era and there was always an anxiety that China could retake Macau. In his memoir, Calvet de Magalhães (Reference Magalhães1992, 23) also recalls violent campaigns against Macau when he served as the Portuguese consul in Guangzhou, at a time when China had just emerged as a victorious ally after the Second World War and was attempting to negotiate Macau's retrocession. These campaigns were carried out through the press, with manifestations and petitions calling for the reunification of Macau. An association was established for that purpose in 1947 (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 39). Macau was accused of having collaborated with Japan during the War and of being a sanctuary for criminals and a centre of immoral activities (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 539), which again distinguished it from Hong Kong. The Chinese press, such as the Chongqing Dagongbao (1945, 2), depicted Macau as a shameful ‘Oriental Monte-Carlo’ filled with all kinds of immorality and claimed that it must be returned to China. In an article entitled ‘Macao: Unfinished Business’ published in China Magazine, Chu Chi (Reference Chu1946, 34) similarly argued that China still had an urgent matter to deal with: that of recovering Macau and ‘cleansing a land that was long dipped in opium, gambling, and crime’.

Portuguese authorities launched a counter-campaign to legitimate its presence in Macau. This included sponsoring a visit to the territory by Guangzhou journalists in 1948, during which they were told the tone their articles should take (Magalhães Reference Magalhães1992, 49) and commissioning the Ministries of Colonies and Foreign Affairs with works on Macau's origins and history (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2008, 54).

Tensions persisted in the early People's Republic of China (PRC) period and were complicated by Portugal having no diplomatic relations with China owing to its anti-communist position. There were a number of skirmishes between the two in 1949 largely due to the protection given to Kuomintang (KMT) agents in Macau who carried out sabotage missions in China. In 1949, an article in the Wenhui bao by Hu Shuqi (Reference Hu1949, 5) again demanded the return of Macau.

As argued by anthropologist Pina Cabral (Reference Cabral2002) (and Cabral and Lourenço Reference Cabral and Lourenço1993), throughout its history Macau has been assailed by crises of legitimacy. In the post-war era the most serious crises were the 1952 border conflict and the government's plan to celebrate 400 years of the Portuguese presence in Macau in 1955.

The 1952 border conflict saw fire exchanged between both sides that resulted in military deaths and China ceasing to provide food, as well as people in Macau seeking refuge in Hong Kong.Footnote 13 One of China's main motivations in initiating the conflict was to warn the Portuguese administration not to comply with the UN embargo: under UN pressure, a commission had just been established in Macau to control breaches of the embargo, which was detrimental to China getting the strategic materials it needed (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 114).

The 400 Years celebration, meant to affirm Portuguese sovereignty in Macau, was planned as a month-long extravaganza but it was cancelled after China threatened to stir up trouble in Macau if it proceeded. A campaign against Portuguese imperialism in Macau and Asia followed, in which China claimed Macau as Chinese territory. This will be discussed later as Long Way was caught up in it.

‘The Monte Carlo of the Orient’ vs ‘the jewel of the Orient’: discourses on Macau

As mentioned, a deep-rooted negative discourse about Macau circulated internationally that defined the territory as a centre of vice and illicit businesses. Such censure appeared in the foreign media, in books, and also films. Portuguese publications often vehemently protested against this ‘campaign of discredit against Macau’ (Inso Reference Inso1932, 31), denying the veracity of the reports, and instead attempted to convey a positive discourse.

Entries on Macau in the General Bulletin of the Colonies/Overseas, which was the official journal of the colonies, abound with such contestations, revealing an anxiety about Macau's international image and reputation. In 1932 colonial official Jaime do Inso (Reference Inso1932, 31) protested against Macau being ‘the object of endless attacks […] as a dangerous centre of vice’ in an article in the Bulletin. In the 1950s international criticism continued to be a serious enough issue for Sarmento Rodrigues, the minister of overseas, to address it in his speech in 1951 to mark the appointment of the new governor of Macau, Marques Esparteiro, which was reproduced in the Bulletin: ‘Forgetting the services that Macau has rendered humanity, there has been no lack of accusations directed at us […] Macau's vices are fewer than in the larger area […] only those who have a fertile imagination and wish to illustrate magazines […] with sensational and imaginary reports can point them out’ (Boletim Geral do Ultramar 1951, 9). In Portuguese official discourse, then, Macau was instead presented as having ‘a moral value that no other foreign possession has’ (Boletim Geral das Colónias 1926, 241) and a long and continuous history as a peaceful refuge, and as an exemplary centre of Sino-Portuguese friendship.

Publications repeatedly celebrated Macau as a refuge. In a 1933 interview, Governor Bernardes de Miranda declared that ‘rich men from China's hinterland live here, placing themselves under Portuguese protection […] these men know that there are no risks here […] they can live in harmony with other Chinese and Portuguese’ (Boletim Geral das Colónias 1933, 237). During the Second World War the Bulletin wrote of ‘the valuable assistance given to war refugees without distinction of race or nationality’ (Boletim Geral das Colónias 1943, 61; my emphasis). In 1945 it similarly celebrated that ‘thousands of refugees have found a solid refuge here […] Macau is a peaceful place in the midst of the burning Orient’ (Boletim Geral das Colónias 1945, 134–135). This refuge discourse became particularly prominent from the War onwards thanks to Macau's role as a sanctuary during the conflict, for Portugal had remained neutral throughout the War, and though ‘under Japan's shadow’ (Gunn Reference Gunn2016), it had not been occupied by the Japanese. After the establishment of the PRC in 1949, Macau as a shelter from communism was likewise extolled, and that year the governor stated that ‘it is in Macau where Chinese who suffer from political oscillations find refuge’ (Boletim Geral das Colónias 1949, 159). A 1954 entry referred to the many poor people coming from ‘Red China’ and the assistance they received (Boletim Geral do Ultramar 1954, 163).

The Bulletin also frequently praised Macau as a centre of Sino-Portuguese friendship. It frequently pointed out that Macau differed from other colonies or concessions in China, in that it was neither a conquest, nor the result of violence but was kept thanks to the excellence of Sino-Portuguese relations and the respect shown towards Chinese.Footnote 14 One entry raved, in typical Luso-tropical fashion: ‘The perfect understanding of […] Chinese, without violence against their religion, traditions, and rights is […] one of the most beautiful oeuvres of fraternity carried out in the Orient’ (Boletim Geral do Ultramar 1952, 58). The aforementioned speech by the minister of overseas also underscored Macau's harmonious interracial relations, and is likely to have been inspired by Freyre who would soon debut his trip across the Portuguese world upon his invitation. The minister further noted that: ‘a sociologist would admire this work of the heart […] Macau is an example which merits to be studied by those who have responsibilities in the relationships between people, to learn the most profitable lesson […] But the world persists in not taking notice of the Portuguese example’ (Boletim Geral do Ultramar 1951, 7–8).

These counter-narratives frequently praised Macau as the ‘jewel of the Orient’, an ‘oasis of peace’, or a ‘sheltered port’ in a turbulent world, particularly in an Asia ensnared in constant conflicts, and also a ‘lighthouse of civilization’ ‘irradiating Western culture in the Far East’ (Boletim Geral do Ultramar 1952, 58). This lighthouse citation comes from a 1952 article, which also recycled the idea that in Macau there had always been a perfect Sino-Portuguese fraternization. Though official discourse had always been a mixed one, oscillating from ‘civilizing mission’ to Luso-tropical-like Sino-Portuguese friendship, which both happen to be present in the latter instance, in the 1950s a Luso-tropical discourse, which was becoming increasingly popularized across the Portuguese world, was more consciously adopted. In these narratives, Macau became the symbol of interracial harmony, from which the world should learn. These discourses, as will be discussed later, found themselves reproduced in the films about Macau: in Western films a mostly negative one highlighting Macau as a centre of vice, and in local productions a positive one celebrating Macau as a site of refuge and Sino-Portuguese friendship, which served as a response to the former.

Eurasia, Eurasians, and film production in Macau in the 1950s

Long Way was produced by Eurasia, which had been founded in 1954 in Macau. Eurasia's activities encompassed production, with a view to establishing a film industry in Macau, and also distribution and exhibition.

A number of propagandistic documentaries had been locally produced in 1952 through a combination of official and private efforts by people from both the metropole and Macau. That year the minister of overseas, Sarmento Rodrigues, went on a highly publicized tour of Portuguese possessions in Asia: Portuguese India, Macau, and Timor. The objective of the trip was to consolidate ties between the metropole and its Overseas Provinces in a time of anxiety, as well as to advertise this unity and Portuguese sovereignty to the world. It was also an opportunity for the minister to better understand the problems assailing these places. He was accompanied by film-maker Ricardo Malheiro who was commissioned to make a documentary about the trip (Noticias de Macau 1952a, 5). After the minister's departure from Macau, Malheiro stayed on to make documentaries. These were made with the support of the local government, and strove to present a positive image of Macau and reaffirm Portuguese sovereignty. One production involved the direct participation of Governor Marques Esparteiro (1951–1956). Macau, Portuguese Land (Noticias de Macau 1953c, 2) began and ended with him.Footnote 15 Active governmental participation would also be the case for other films made in the 1950s. Macau, Jewel of the Orient (dir. Miguel Spiguel, Reference Spiguel1956) also featured the governor condemning Macau's negative depiction abroad and declaring that the film was an effort to redress that. In his words: ‘Among our Overseas Provinces […] Macau has certainly been the most targeted by unjust critiques from certain sectors of international public opinion. I am convinced this documentary will contribute to a better understanding of Macau and destroy those nefarious impressions that circulate overseas.’

The production of short documentaries in Macau would boom in the mid-1950s, which, as discussed, was a period of increasing crisis for Portugal following the annexation of Portuguese enclaves in 1954 by India, which also claimed the rest of Portuguese India; the rise of the Afro-Asian bloc at the Bandung Conference (1955), in which the PRC played a leading role; and the intensification of decolonization. As also mentioned, the 1950s witnessed much tension between the Portuguese administration and China, aggravating the situation in Macau.

Eurasia followed on from the 1952 filmic initiatives. In fact, some of its partners had participated in those productions, and now they sought to create a film industry in Macau that would celebrate the territory, affirm Portuguese presence, and cleanse its image. Most of its shareholders were linked to the colonial administration and Eurasia also received official support at the governor's level. Its partners visited Marques Esparteiro to inform him of their motivations and purpose in establishing Eurasia and eventually a film industry in Macau. They also handed him the script of Long Way. The governor offered his support and collaboration, and the heads of other departments similarly gave their backing (O Clarim 1954e, 4).

Eurasia's most active members were the Portuguese José Silveira Machado and Eurico Ferreira who initiated the enterprise. Machado, a long-term resident who had moved to Macau as a youngster, worked for Macau's Economic Services and was responsible for its propaganda and tourism section. He also collaborated with various Macau periodicals as a journalist. Machado was the writer and producer of Long Way's script. Ferreira was a sergeant posted in Macau and a cinema aficionado who had cinematic experience, having worked for film studios in Portugal and France. He directed the film (O Clarim 1954a, 4).

Another important figure was the Portuguese Eurasian Pedro José Lobo. Though not a partner at Eurasia, he at least partly financed Long Way and also composed its music. He remained active in film-making throughout the period, mainly as a musician, but also as a producer and financier. Lobo was among the most powerful and richest men in Macau. He was the head of the Economic Services and therefore Machado's boss. Additionally, Lobo had various business interests, and was implicated in some of the scandals that tarnished Macau's image, like smuggling. These were exposed in the international press and an accusatory finger was pointed at him. Life (Rowan Reference Rowan1949, 21) wrote that the ‘the economy of Macau is in the hands of the […] Chinese-Portuguese named Lobo’ and referred to him as the ‘real ruler’ of Macau. Time (1951, 23) likewise accused Lobo of being the man behind smuggling and claimed that in fact he ran Macau. There had also been doubts in the metropole about Lobo at different times and there had even been a prison order made against him (Silvério and Borges Reference Silvério Marques and Borges2012, 74). Both Lobo's image and that of Macau suffered, so it was in his interest to correct these negative images.

Figure 1. Pedro José Lobo, head of the Economic Services. Source: Boletim Geral do Ultramar (General Bulletin of Overseas), nos. 341 and 342, November–December 1953, p. 202.

Hence, both Lobo and Machado had a stake in the good name of Macau and were directly involved in the propaganda about the territory. On the occasion of a conference on the ethics of journalism that Machado gave in 1953, Lobo, who acted as the moderator, praised his writings ‘in the defense of Macau against the defamatory accusations unjustly laid down in the foreign press’ (Circulo Cultural de Macau 1954, 166).Footnote 16

Alberto Dias Ferreira, a Eurasian, was the other Eurasia partner who also worked for the Portuguese administration as the subchief of police.Footnote 17 As mentioned, Macau was often portrayed as a centre of vice and crime, with a corrupt and inefficient police force. This was an image that was omnipresent in Western films about Macau, as will be discussed later, and so it was equally in the interest of the police to dispel it. (In fact, one of Long Way's protagonists is a dutiful police inspector.)

Eurasia's other partners were Margarida Botelho, Machado's Eurasian wife (Forjaz Reference Forjaz1996, 1:557); Adelino de Almeida, a metropolitan school teacher who wrote some of the film's dialogues (O Clarim 1954f, 4); and Adrião Pinto Marques, a Eurasian (Forjaz Reference Forjaz2017, 4:176) who served as the company's accountant (Boletim Oficial de Macau 1954, 471–472).

Another key partner was the Hong Kong-based cinematographer Albert Young (Yang Jun). Young not only represented a vital Hong Kong connection but was in fact Eurasia's sole full-time bona fide film professional. He was Long Way's cinematographer. Moreover, over half of the film's main characters were played by Hong Kong actors associated with the ‘free bloc’ Hong Kong film industry. In 1954, Eurasia was accepted into the Federation of Motion Picture Producers in Southeast Asia (FPA), which was funded by The Asia Foundation (TAF), an American organization that aimed to block communist interests in the film industry. The Hong Kong connection, which was also essential in the 1952 films, with links to the anti-communist camp in the Asian film industry, will be discussed in more detail.

Machado (as script-writer), Ferreira (as assistant director), Young (as cinematographer), and Lobo (as musician, general facilitator, and probably financier) had all collaborated with Malheiro in the making of the 1952 documentaries.

As seen above, about half of Eurasia's members were Portuguese Eurasians from Macau.Footnote 18 ‘In general Iberian colonial societies were shaped through hierarchical interethnic integration […] along with a graduated scale of mixed-race people’ (Bethencourt Reference Bethencourt2013, 340), with the Americas (Brazil in the case of the Portuguese) exhibiting the most complexity, but ‘the configuration and status of mixed-race people communities were different in Portuguese colonies in Asia, Africa, and America’ (Bethencourt Reference Bethencourt and Levenson2007, 49). In Asia, due to Portuguese reliance on local communities, this ‘racial regime was not reproduced in its full complexity’ (Bethencourt Reference Bethencourt2013, 256). Miscegenation even became part of official policy, with Portuguese India's Governor Afonso de Albuquerque's encouragement of mixed marriages in Asia in 1510, his goal being ‘to create an elite of Euro-descendants capable of managing the empire at a local level’ (Bethencourt Reference Bethencourt and Levenson2007, 48).Footnote 19 This practice spread throughout Portuguese Asia, creating a status group of mixed-race people, due to the ‘inability to renew the European stock […] in faraway territories’ (Bethencourt Reference Bethencourt and Levenson2007, 49). A Luso-Asian mixed community also quickly grew in Macau as it became a Portuguese settlement in the mid-sixteenth century. These ‘Portuguese of the Orient’, as they were also known, had ‘origins from everywhere in the Asian seafaring world’ (Cabral Reference Cabral2002, 21), originally through the female line. Besides marriage/concubinage with a wide variety of ethnicities, people from other groups were integrated by converting to Catholicism (Cabral Reference Cabral2002, 22). Hence, they were a broadly mixed group that formed their own distinctive Creole culture and language (Patuá) (Cabral Reference Cabral2002, 22).Footnote 20

Eurasians, however, suffered some degree of discrimination. During much of Macau's history, metropolitan Portuguese generally occupied the most prominent positions (Miranda and Serafim Reference Miranda, Serafim and de Oliveira Marques2001, 236). Only a few Eurasians were able to rise to the top (Miranda and Serafim Reference Miranda, Serafim and de Oliveira Marques2001, 238).Footnote 21 The Eurasian community was also shaped through hierarchical relations, with the more prestigious traditional families striving to renew their Portuguese blood by marrying their daughters to metropolitan men, especially officials (Miranda and Serafim Reference Miranda, Serafim and de Oliveira Marques2001, 238), or they married among themselves to preserve their lineages (Reis Reference Reis and de Oliveira Marques2003b, 354).Footnote 22 The children resulting from relations between masters and their slaves, or adopted Chinese orphans (usually females), and, according to Amaro (Reference Amaro1994), possibly also converted Chinese were categories within the Eurasian community that enjoyed less prestige (Amaro Reference Amaro1994; Teixeira Reference Teixeira1994; and Morbey Reference Morbey1994).

In the twentieth century, due to closer contacts with the metropole, and particularly in the post-war era due to the sense of crisis and uncertainty, Eurasians came to associate more with a metropolitan Portuguese identity and maximize their ‘capital of Portugueseness’ (Cabral and Lourenço Reference Cabral and Lourenço1993, 77). This gave them access to middle-range positions in the Portuguese administration. They also acted as mediators between Portuguese and Chinese, including the Chinese business elite, which gave them benefits.Footnote 23 Hence, they largely identified with Portuguese colonial power (Cabral and Lourenço Reference Cabral and Lourenço1993, 87).Footnote 24 In Macau, there were hardly any opponents to the New State, unlike in Portugal or Portuguese Africa (Cabral and Lourenço Reference Cabral and Lourenço1993, 126), and, for Macau's Eurasians, keeping Macau Portuguese was more attractive than the alternative: Chinese retrocession, which would either make them foreigners in their own land (Cabral and Lourenço Reference Cabral and Lourenço1993, 126) or force them into exile, thus spelling ‘the end of their existence as a group’.Footnote 25 The global decolonization process and the loss of Portuguese territories in India therefore caused much anxiety.

The main purpose of making Long Way was to clean up the image of Macau from accusations circulating in the international media and film, which ultimately served to defend Portuguese sovereignty in Macau. Not only were most of Eurasia's partners working for the Portuguese administration, but Eurasians as well as long-term residents such as Machado had affective ties to Macau, which further compelled them to defend it. Yet, as shall be discussed, through the promotion of Luso-tropicalism in the film, Eurasians may also have meant to call for a more egalitarian society in Macau and at the same time celebrate their hybrid culture which was often looked down upon by metropolitans and was furthermore in the process of disappearing (Cabral and Lourenço Reference Cabral and Lourenço1993, 183).

Finally, the other goals of the Eurasia partners were mainly business and industrial ones. One of them was to establish a film industry in Macau. As mentioned, Macau was then suffering from an economic crisis, mainly resulting from the embargo. A film industry would contribute with new revenues for the Economic Services headed by Lobo. Newspaper articles reporting on Eurasia's intention to create a film industry in Macau observed that: ‘at a time when destiny appears to hamper Macau's economic life, everything that can contribute to improve the financial situation must be embraced […] Macau must create new sources of revenue to face present and future setbacks’ (Fernandes Reference Fernandes1954, 4). Eurasia partners believed Macau, with its magnificent landscape and Oriental atmosphere, had great potential for a film industry and could also be a centre for films made in Asia (Fernandes, Reference Fernandes1954, 4). Hooking up with the Hong Kong film industry would therefore jump-start this process since Macau had no film professionals or facilities.

Long Way as a response to Western films I: cleansing Macau's image

On one level Long Way aimed to propagate a positive image of Macau and seems to have been a response to Western films set in the territory, particularly the French Gambling Hell (dir. Jean Delannoy, Reference Delannoy1939/1942, hereafter Gambling) as well as Hollywood's Macao (dir. Josef von Sternberg, Reference Sternberg1952) and Forbidden (dir. Rudolph Maté, Reference Maté1953), which mostly conveyed a negative and Orientalist image of Macau.

Overall these films reflected the unfavourable discourse on Macau circulating in the international arena, as previously discussed. As a result of these negative portrayals, both Gambling and Macao were censored in Portugal (Vasques Reference Vasques1995, 67–68).Footnote 26 Gambling was allowed to be screened in 1947 after scenes that located the film in Macau and Portuguese references had been cut, so that the film might have been set in any East Asian location (Vasques Reference Vasques1995, 67). Macao would only be screened in Portugal in 1982, eight years after the end of the New State and the beginning of democratization (Vasques Reference Vasques1995, 67). Neither were the films shown in Macau in the 1950s.

These films share similarities in plot, characterization, and their depiction of Macau. In fact, Macao seems to have been inspired by the earlier French film. Forbidden also seems to have been influenced by these two earlier productions. In these films Macau is portrayed a lawless hell in which a ruthless casino/smuggling king reigns over the territory. There is a love triangle, with the kingpin wanting to possess a (recently arrived) woman (a songstress in Gambling and Macao), yet she and an adventurer/gangster underling are in love, which aggravates the men's conflict. The Portuguese characters, for their part, are corrupt and submissive. Most of the action takes place in the casino and the shady port area, but the new arrivals (and audience) are also shown around an exotic and wicked Macau at the beginning of the films. Long Way also shared some of these tropes but resolved all conflicts to present a positive counter-image of Macau.

In Gambling, filmed and set during the Second World War, Macau is run by the all-powerful Chinese Tchai who owns the casino and a bank and is also an arms smuggler. There are no policemen or authorities in the film, despite racketeers shooting in the streets and people being kidnapped and murdered, or a naval battle between Tchai and the adventurer whose arms smuggling deal goes wrong. Crime is routine and goes unpunished.

In Macao, a voiceover at the beginning of the film declares that ‘Macau has two faces, one open, the other veiled’. In this film, Macau is run by an American casino owner who also deals in smuggling. Though policemen are present, they are utterly corrupt. One Portuguese police officer acts as the American's informant, facilitating his criminal activities for personal gain. Emigration police let businessmen enter Macau with undeclared goods in exchange for bribes. Upon arriving in Macau, the protagonists, an American adventurer and a songstress, make denigrating comments about its rampant smuggling. The Portuguese characters in the films, however, praise Macau, welcoming visitors to a paradise on earth. ‘Any visitor to Macau should feel as untroubled as in the Garden of Eden,’ says the policeman in Macao. Similarly, in Gambling, a Portuguese petty crook who acts as a guide for newcomers announces that ‘Macau is the most wonderful city in the world, there is no desolation, no war, only happiness and joy.’ Forbidden similarly depicts a crime-ridden Macau with street shootings and inefficient police, which is likewise run by an American who owns the casino and is involved in smuggling.

In these films, the police are either absent (Gambling), corrupt (Macao), or inefficient (Forbidden). In the latter two films they are contrasted with the efficient and uncorrupt Hong Kong police and also an American undercover police officer in Macao who sacrifices himself in order to arrest the criminal.

Gambling dealt specifically with arms smuggling, and the French journalist, upon disembarking, warns that ‘the world is anguished by the arms smuggling going on in Macau’. Gun-running is also present in Long Way, though the latter's message is that of the Portuguese police zealously resolving an arms smuggling operation perpetrated by foreign gangsters. Gambling is part of a lineage of Western films in which Macau stood as a centre of arms smuggling. This can be traced back to Hong Kong Nights (dir. E. Mason Hopper, Reference Hopper1935) which featured a foreign criminal who operated a casino and ran a gun smuggling ring. It was followed by Windjammer (dir. Ewing Scott, 1937) where, in spite of Macau not appearing in the film, the protagonists were stuck on a boat sailing to Macau as its captain was smuggling arms to the territory.

During the late Qing, Republican, and also PRC eras, arms smuggling did take place in Macau (and Hong Kong), eliciting international attention. This topic received particular scrutiny during the period of the China arms embargo (1919–1929). The embargo was imposed on China by Western powers, with Portugal also a signatory, during the Warlord era in order to end the Civil War and ‘facilitate the formation of a unified national government in China […] under pro-Western leadership’ (Valone Reference Valone1991, xviii–xix). All powers, however, infringed upon the agreement (Chan Reference Chan2010, 133), and smuggling through treaty ports, Hong Kong, and Macau was rife (Chan Reference Chan2010, 105). Furthermore, as Chan (Reference Chan2010, 136) has pointed out, the beginning of the ‘Nationalist government […] did not mean the end […] to the Western armaments trade’.

The international press pinpointed Macau as a site where arms smuggling took place. For instance, an article in the Manchester Guardian (1934, 9) mentioned that during the Chinese arms embargo, Macau was the channel used by munition-makers. The French press also featured such reports, as in a 1935 article that stated that anyone who wanted to buy arms just needed to go to Macau (Demaître Reference Demaître1935, 2). A number of reports about Gambling highlighted that during the Sino-Japanese War ‘Macau has become the favorite rendez-vous for arms smugglers’ (La Petite Gironde 1939, 8). Popular French writer Maurice Dekobra, the author of the novel Macao, Gambling Hell (Reference Dekobra1938) on which Gambling is based, pointed out in interviews that ‘Macau is a particularly favourable place […] for arms smuggling’ and other vices (G.T 1939, 4).

Besides Long Way functioning as a response to Macau's depiction in these films as a hotbed of arms smuggling, this subject matter again gained currency around the time the film was being made. One of the scandals assailing Macau in the mid-1940s and early 1950s, and which was frequently reported in the international press, was its role as a centre of arms smuggling to China and to communist forces in North Vietnam and Thailand (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 588–589). Starting in 1949, the French, who had been fighting the Vietminh, had protested and demanded the traffic stop (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 77) and there were also protests by Taiwan. In 1950 The China Mail (1950, 1) reported that Taiwan's ‘Ministry of Defense condemned Chinese smugglers in Macao for trafficking in arms and ammunitions into Indo-China, Siam and Malaya […] to support local communists’. In 1951 it again reported that the Ministry had ‘charged that Macao has become a transit port for war materials from Hong Kong to communist China’ (The China Mail 1951, 1). In some reports Lobo was accused of being a player in the trade and Pinto Marques, one of Eurasia's partners, is also reputed to have dealt in arms smuggling (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 591–592).Footnote 27 Portuguese government documents reveal there was a preoccupation that such accusations ‘gravely affect the reputation of the Portuguese administration’ (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 593). Hence, Long Way was responding to a history of denunciations about arms smuggling in Macau which during the Cold War was again under the spotlight due to the First Indochina (1946–1954) and Korean Wars as well as communist insurgencies across Asia.

Yet, in all three films it is not the Portuguese (who actually ruled Macau), but an American criminal (Macao, Forbidden) or a Chinese (Gambling) who control the casino and smuggling operations. Portuguese characters in Gambling and Macao are portrayed as deceitful and weak, working as flattering lackeys to the criminal kingpins. They seem to symbolize the nature of Portuguese colonialism, with its long history of decadence and accusations of immorality. As Lopes (Reference Lopes2016, 73) has written, the films also conjured what Boaventura de Sousa Santos has called the Portuguese empire's ‘subaltern colonialism’, since the Portuguese are characterized as inefficient colonizers while ‘the colonies (are) submitted to a double colonization—by Portugal and the countries it depended on’.

Lopes (Reference Lopes2016, 79) has shown that in the case of Macao the original material presented an even more negative image of Portuguese colonial rule in Macau. This was to some extent toned down due to the interference of the Production Code Administration of the Motion Picture Association of America that strove to represent all nations fairly.

These productions prompted protests in both Portugal's and Macau's press. Dekobra's novel Gambling Hell had already caused an outcry. Letters were sent to the Portuguese press, such as one in 1938 by a former Macau official: ‘I cannot repress my indignation protesting energetically against all the falsehoods about our beautiful Far-Eastern colony […] There is no hell whatsoever in Macau […] What some writers and international journalists have invented is nothing more than mere fantasy’ (Cruz Reference Cruz1938, 2). Dekobra was interviewed by a Portuguese journalist posted in France when the film was being shot in 1939, and he felt compelled, prompted by the journalist, to write a letter, which was reprinted in a Portuguese and Macau daily, reiterating his respect for Portugal, confirming that none of the characters in the novel is Portuguese, and stating ‘that Macau is very well administered by Portugal’ (Osorio, Reference Osorio1939, 3).

A vigorous critique of Macao, which called the film a ‘shameful cinematic campaign’, likewise appeared in the Portuguese press. It was reprinted in the Macao daily: ‘for the criminals responsible for this film, Macau is […] the city of sin and obscure business […] it insults a nation and city […] Macau is nothing like the film […] Macau possesses in the Far-East a moral value without equal’ (Noticias de Macau 1952e, 3).

Long Way used similar elements but these were now employed to counteract these negative films. It presented Macau as a lawful place in which an upright police force, led by one of the protagonists, a dutiful Portuguese police inspector, successfully fought arms smuggling by a sinful capitalist who patronized the casino. The criminals were apprehended, and one of them, the Chinese male protagonist, was set on the right path with the help of the policeman and a Portuguese priest. Hence, Long Way's portrayal of the police is the opposite of the French and Hollywood films and also differed from the police's detrimental image in the international press.

In January 1953, the French paper Le Monde published a special report on Macau, describing it as a ‘city of fear’ with an inefficient police force and rampant smuggling. This prompted an outcry from both the local and metropolitan Portuguese press which responded by unanimously praising the police's efficiency, in one instance even claiming that it was the most orderly in the Orient (Noticias de Macau 1953a, 3). The local press reprinted an open letter by a French resident of Macau to Le Monde objecting to the calumnies, and recalling that Dekobra too had been wrong in what he wrote about Macau (Wengraf Reference Wengraf1953, 1 and 2). This month-long outburst culminated with a protest about the defamatory campaign against Macau by its deputy at the Portuguese National Assembly (Noticias de Macau 1953d, 3). All reports highlighted that instead of being a city of fear and vice, Macau was orderly, well-policed, and a site of refuge.

In the French and Hollywood films, some of the characters are refugees, such as the French songstress in Gambling who escapes war in China, and the woman in Forbidden who flees the United States to get away from gangsters. In Macao, the new arrivals are also running away from their previous lives. However, none finds peace in Macau. The French songstress even meets her death as her boat is bombarded in the conflict between the adventurer and Tchai.

Most of Long Way's protagonists were also refugees, in this case fleeing the Civil War and communist rule in China and the film extols Macau as a place of refuge. Unlike in the Hollywood and French films, they are able to rebuild their lives in Macau. As discussed before, Macau's function as a sanctuary at various times in its history was frequently celebrated in official publications and the Portuguese press in Macau. The film's promotional materials in Revista da Semana (1954a and 1954b) asserted that ‘Macau is […] a refuge for those persecuted by war, a blessed oasis’ and ‘an open city […] for people of all origins’. An article in the Macau daily similarly claimed the film ‘will bring to the whole world the reality of Macau—an oasis of peace in the troubled orient’ (Noticias de Macau 1955c, 7).

As aforementioned, in the French and Hollywood films, the protagonists went on a tour of Macau, and it is a sensational, mysterious, and dark Macau that is emphasized. In Gambling, tourists even witness shootings in the streets. Long Way, however, showcased Macau's most beautiful spots as the police inspector takes his love interest on a tour of Macau, further promoting it as a lovely and peaceful place. It also functioned almost as an advertisement for tourism, for which Machado and Lobo were responsible. If the film could seduce potential tourists, all the better, as this would bring further revenue to Macau. Tourism was also seen as a way to promote a positive image of Macau as a tranquil place. For instance, articles in the Macau press in 1956 claimed tourism as ‘a way to deny the calumnies’ against Macau (Noticias de Macau 1956, 1). Yet, the medium of cinema was seen as one of the most efficient ways to transmit a positive image of Macau. As Machado pointed out, through cinema ‘the real action of Macau in the Orient […] humanitarian and pacific will be better propagated and understood by the world […] than all the books that […] exist’ (Fernandes Reference Fernandes1954, 4; my emphasis).

Long Way as a response to Western films II: interracial love and Luso-tropicalism

All the films depicted love triangles between similar characters, namely songstresses, adventurers, casino owners, and in the French and Portuguese films, Eurasians. These two films involved interracial love, yet with different outcomes.

In Gambling there are two parallel love stories. One is between the French journalist who comes to Macau to investigate arms smuggling and a Sino-French Eurasian, Jasmine, who is the daughter of Tchai, but knows nothing about her father's illicit dealings. In her study of interracial love and sexuality in Hollywood cinema, Gina Marchetti (Reference Marchetti1993, 109) has argued that, though miscegenation is mostly taboo, in some films it is allowed by showing the West's superiority in a romance between a Westerner and a local woman whom he saves from the excesses of her own decadent culture. This Marchetti calls the ‘salvation narrative’. Behind the scenes Tchai tries to separate the lovers, yet in the competition between the French lover and the Chinese father over Jasmine, the former is victorious as he rescues her from her father and culture. Jasmine rejects her father (and Macau) when she discovers he is the owner of the casino and takes refuge offshore, on the boat where her lover is staying.Footnote 28

Jasmine also corresponds to what Marchetti (Reference Marchetti1993) identifies as the assimilation narrative in Hollywood interracial romance, when non-(fully)-Caucasian characters relinquish their culture in order to assimilate into the West. Although Jasmine has just returned to Macau, she soon expresses her desire to leave and go to France as ‘it's mummy's country’ and also because she is in love with the Frenchman. She has spent many years in France, was educated there, has a French governess, wears Western clothes, and there is nothing much that marks her as Eurasian, except for her Chinese father whom she eventually rejects.

Kennedy-Karpat (Reference Kennedy-Karpat2013, 101), in her analysis of exoticism in French cinema of the 1930s, identifies a plot device she labels ‘second-generation miscegenation’ that couples a (generally female) mixed-race character with a Westerner, pushing the mixed race person to their Western roots and away from the non-Western side of their heritage. As she notes in her discussion of Gambling, Jasmine belongs to that category. Hence it is similar to the assimilation narrative, with the difference that one of the lovers is mixed-race. Although the film's ending is open-ended and it is not entirely clear whether the couple escaped or died, the latter seems more likely. This is a frequent trope in interracial romances where characters are punished for their transgression, as discussed by Marchetti (Reference Marchetti1993).

The second romance is a love triangle involving the French songstress, the German adventurer, and Tchai. Tchai, who has a soft spot for French women (his late wife was French), covets the songstress. There are a few scenes set in the casino where he gazes lustfully at her behind a curtain or through a hidden camera while proclaiming ‘she is beautiful’. This role is played by Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa: as Kennedy-Karpat (Reference Kennedy-Karpat2013, 170) has pointed out, it is one that is typical of his screen persona in both Hollywood (first moulded in The Cheat, dir. Cecil DeMille, Reference DeMille1915) and French cinema, where ‘subjugation of white woman (was) a key trope of Hayakawa’. In his long career in both Hollywood and French cinema, Hayakawa played roles in which he personified the ‘yellow peril’, desiring white women and plotting to forcefully take them away from their white partners (Kennedy-Karpat Reference Kennedy-Karpat2013, 274). Wong (Reference Wong1978, 26–27) has observed that in Hollywood cinema, Asian men often function as sexless eunuchs or threatening rapists. In Gambling, the Hayakawa character belongs to the rapist type (as he did in The Cheat), since he forces himself onto the songstress, revealing his intention of keeping her captive. Captivity tales are also one of the narrative strategies in Hollywood interracial romances that Marchetti (Reference Marchetti1993) discusses. She flees his near rape by spraying pepper into his eyes. What Marchetti (Reference Marchetti1993) has argued for Hollywood cinema may also apply to Gambling—that Asian men represent a threat to the white woman, which works as a metaphor for the Asian threat to the West. Ultimately, white supremacy is maintained as Tchai's interference in the two love stories is unsuccessful.

In Macao and Forbidden, the love triangles are strictly between Americans. In Macao, the songstress and the adventurer, who come to Macau to look for work, soon fall in love. Yet, the casino owner attempts to seduce the songstress and discard his American girlfriend. In Forbidden, the casino boss is engaged to a woman until her former lover appears and they reignite their affair while being pursued by the boss who seeks revenge. In these two films interracial love is absent. Marchetti (Reference Marchetti1993, 1) has argued that, despite there being a fascination for Asia and Asians in Hollywood, usually these do not exceed erotic fantasies: ‘any radical deviation from the mainstream is unlikely to be voiced openly because of the possibility of a poor box-office showing. Therefore Hollywood's romance with Asia tends to be a flirtation with the exotic rather than an attempt at any genuine intercultural understanding.’ There was also a practical reason for this: at the time the United States had anti-miscegenation laws and the depiction of interracial relationships was forbidden (Marchetti, Reference Marchetti1993, 5). However, in Macao's original conception, the girlfriend of the casino boss was to be a Portuguese Eurasian (in ‘yellowface’) to make it more understandable to audiences why he would want to discard her for an American girl. A letter from the film's executive producer Samuel Bischoff (Reference Bischoffn.d.) shows that interracial love was perceived as inferior and meant to be short-lived: ‘It's quite understandable that a man living […] in the Far East […] would soon tire of an Eurasian or half-breed particularly if an American girl came along […] that is why we should have a girl made up for a Eurasian.’Footnote 29

In Long Way, there were two interracial love triangles. One was between Helen, a Portuguese-Eurasian refugee from Shanghai who had fled that city as it was taken by the communists, and two metropolitan Portuguese men, the aforementioned police inspector and a soldier stationed in Macau. Her relationship with the police inspector remains platonic because he was too busy with his duties to properly court her. She eventually got engaged to the soldier, thanks to the policeman's selfless intervention when he prevented the soldier from being assigned elsewhere as had been planned. Hence, their love was able to flourish, unlike in Gambling, in which the young interracial couple must either escape Macau or die. The other love triangle was between Tam, a Chinese refugee, who was involved in arms smuggling for a capitalist, and a Sino-French Eurasian songstress; he later falls in love with and marries a Chinese Catholic nurse who brings him back into the right path with the help of advice from a Portuguese priest and the police inspector.

The Eurasian songstress at first glance resembles the mixed-raced characters depicted in Hollywood. Marchetti (Reference Marchetti1993) has argued that Eurasians, seen as neither East nor West, are characterized as duplicitous. As embodiments of the threat to racial boundaries, they generally fail in their obsession to be accepted ‘into white society and put aside their racial heritage’ (Marchetti Reference Marchetti1993, 69), usually through a romance with a white lover. In Long Way, however, the Eurasian's duplicity is more likely due to her profession as a cabaret's songstress than her mixed-race background. In contrast, the Portuguese Eurasian refugee is described as simple, modest, and honest (O Clarim 1954f, 4). Furthermore, the songstress loves a Chinese man, not a Westerner, unlike Eurasian characters in Hollywood who reject non-Western lovers in their desire to blend into a Western world, as discussed by Marchetti (Reference Marchetti1993).

Overall, Long Way celebrated interracial love. In the film, Portuguese, Eurasians, and Chinese were on friendly terms and some of the romances crossed racial lines. It also lauded Eurasians and hybridism in accordance with Luso-tropicalism which proclaimed that the Portuguese world created a harmonious, hybrid civilization through miscegenation. Even the name of the company—Eurasia—pointed to this ideal of hybridity. This was conveyed in various press releases that insistently highlighted that the film showcased Macau as a place where different races could live harmoniously side by side (Revista da Semana 1954a).Footnote 30 Press releases further claimed the film was meant to show the world what relations between the races should be like, so that in the near future humanity might benefit from peace (Revista da Semana 1954a).

However, there were also limits to Luso-tropicalism in the film and some ambivalence towards fully embracing it. There was no direct Portuguese-Chinese miscegenation, Eurasians served as mediators in both films, and ultimately Chinese marry within their group. Furthermore, the Portuguese still have a ‘civilizing mission’, as the Portuguese priest and police inspector, with the help of the acculturated Chinese Catholic nurse, guide the Chinese protagonist back to the right path. Hence, the film embodied the transition from a previously more conventional colonial discourse incorporating concepts of the ‘civilizing mission’ to Luso-tropicalism in the post-war era. In fact, it mostly conformed to the one-dimensional version of Luso-tropicalism appropriated by the regime that transformed Freyre's ‘intercultural and interracial symbiosis into a sanitized ideal of Christian brotherhood’ (Klobucka Reference Klobucka, Poddar, Patke and Jensen2008, 473). Christianity here did play a key role in bringing the wayward Chinese back into the fold. Nonetheless, a multiracial and ultimately harmonious society, in which some form of interracial love took place and where everyone found refuge, was celebrated in Long Way. This Luso-tropical eulogy of the harmonious meeting of cultures and races as depicted in the film aimed to legitimize Portuguese rule in Macau in a period of decolonization.

Methodology, realism, and Luso-tropicalism

Besides political and commercial interests, Long Way's film-makers were concerned with artistry and experimentalism. In press releases, they repeatedly stressed what they called the film's unprecedented innovations in terms of the multicultural and ethnic cast, its multilinguism with culturally realistic characters who spoke in their native languages, and their policy of showing the film in subtitled Portuguese, Chinese, and English versions, as well as the use of location shooting. To some extent this was aligned with realist trends in post-war European cinema. The film's director had worked in French film studios and was particularly interested in the innovative aspects of the film. Yet, regardless of all the agents’ exact intentions, this methodology overall was meant to make the film realistic and truthful, unlike foreign productions set in Macau that centred on artifice. The film-makers highlighted that actors played characters from their own ethnicities, including Eurasians (Lola Young as Sino-French and Irene Matos as Macanese).Footnote 31

Indeed, no one was in ‘yellow face’, unlike in the French and Hollywood productions. For instance, in Gambling, a French actress (Louise Carletti) starred as the Eurasian and, except for Hayakawa, most Asian characters were played by Western actors in ‘yellow face’. Nor are the portrayals of Asians Orientalist; rather, the idea was to make them culturally realistic. The Chinese protagonist was depicted as virile and physically strong, diverging from Orientalist images of Asian men as effeminate and weak, yet he was weak in spirit, hence needing Portuguese guidance. His characterization was therefore still partly shaped by concepts of the ‘civilizing mission’.

As mentioned, in Long Way, characters spoke in their own languages. This is unlike the inauthentic Portuguese in Gambling and Macao, in which Portuguese characters speak some words in Spanish, and Forbidden, where Portuguese signage is wrongly spelled.

Much was also made of the film being shot on location and not fabricated in a studio, which indicated its supposed authenticity (e.g. Noticias de Macau 1955b, 11), unlike Gambling, Macao, and Forbidden (though teams were sent to Macau to capture footage in Macao). A Chinese advertisement of the film in the Huaqiao bao (1955a) jokingly asserted that every part of Macau was filmed and that it was so realistic that ‘even me, you and him could possibly appear on the screen’. Long Way's film-makers similarly claimed the film was based on real-life facts and had a realistic script, and ‘was made by people who lived and worked in Macau’ (O Clarim 1954d, 4). Another layer of realism was that, like the characters they portrayed on screen, the Hong Kong cast (Zhong Qing, Wang Hao, and Lola Young), as well as Albert Young, were indeed refugees from communist China. Matos, like the character she portrayed in Long Way, had been a war refugee in Macau, fleeing the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong.

Most significantly, the film-makers underscored that the truthfulness of the film was meant as a corrective to the negative image of Macau that circulated internationally (the French and Hollywood productions would be in this category). It ‘will show […] the real sphere of activities of Macau, an open door for all races […] where all can live with honesty […] without recurring to immorality and crime […] unlike what is unfortunately propagated by a malevolent media’ (Fernandes Reference Fernandes1954, 4; my emphasis).

Long Way, to a large extent, was meant to exemplify the multicultural and racial environment eulogized in Luso-tropicalism, which was put into practice not only in terms of the content of the film but also in terms of production, thanks to the multi-ethnic cast and crew. The same applies to Eurasia: three of its partners were Portuguese Eurasians, three metropolitan Portuguese, and one Hong Kong-based Chinese. In celebration of this multiculturalism, reports put the limelight on the Chinese stars and images of Zhong Qing (Chung Ching) in particular, but Wang Hao (Wong Hou) also often graced reports. Yet, this must also have been because they were real stars, whereas the Portuguese actors were amateurs. In any case, the producers claimed in Luso-tropical fashion that ‘Portuguese and Chinese working together will contribute further for an approximation and communion between the two friendly people’ (Fernandes Reference Fernandes1954, 4).

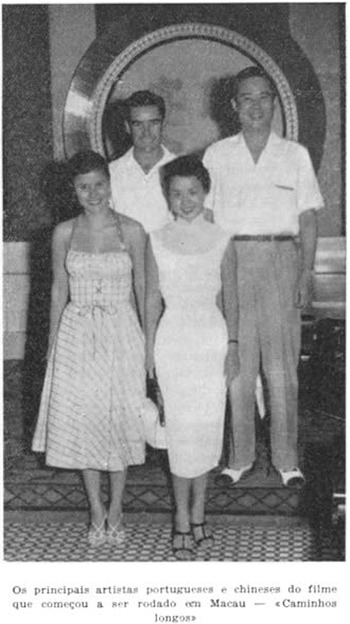

Figure 2. Some of Long Way's main actors: in the back row, José Pedro (as the police inspector) and Wang Hao (as Tam, the Chinese refugee); in the front row Irene Matos (as Helen, the Portuguese Eurasian refugee from Shanghai) and Zhong Qing (as the Chinese nurse). Source: Boletim Geral do Ultramar (General Bulletin of Overseas), no. 351, September 1954, p. 200.

Links to the cultural Cold War and the Hong Kong film industry

Long Way responded to accusations that arms smuggling to communist areas took place in Macau by instead presenting it as a place that not only combated arms smuggling but also provided refuge for people fleeing communist rule in China. This in turn served to firmly position Macau in the ‘free world’ camp and publicize its utility during the Cold War. A Eurasia promotional press release drew attention to the fact that ‘Macau's position, by the Bamboo Curtain, provides an excellent observation point’ (Revista da Semana 1954b). Emphasizing this aspect of Macau may have been an attempt to legitimize Portuguese rule in Macau in the eyes of the ‘free world’. This was significant in a new world order in which Portugal was, to some degree, isolated due to its fascist-like regime and colonial position.

Originally, Eurasia partners aimed to submit Long Way for screening at the Southeast Asian Film Festival (SAFF) held in Singapore in May 1955. The festival, which had been organized by the FPA since 1954, functioned, in the words of film scholar Lee Sangjoon (Reference Lee2017, 112), as an ‘alliance of anti-communist film producers in Asia’. Besides commercial interests, the FPA's main goal was ‘to protect “free Asia” from the invasion of the communist force throughout the cinema’ (Lee Reference Lee2017, 112). It received funding from The Asia Foundation (TAF), an American organization that aimed to boost the anti-communist position in Asia, particularly in the film industry (TAF itself received secret funding from the CIA) (Lee Reference Lee2017).Footnote 32 Members included ‘free bloc’ territories such as Hong Kong, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaya, Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia. In the event, the film was not screened as it was not finished on time; nevertheless in 1954 Eurasia was accepted into the FPA, with Macau added as a member (O Clarim 1955b, 4).

There were, moreover, vital connections with Hong Kong's ‘free bloc’ film industry, which was roughly divided into right and left camps. After relocating to Hong Kong from China, Albert Young, Eurasia's Chinese partner, worked for Hong Kong ‘free bloc’ studios. In 1951 he joined Shanghai émigré film-maker Bu Wancang's Taishan Studio (Stokes Reference Stokes2007, 538).Footnote 33 Moreover, just before Eurasia's formal founding, Machado and Ferreira carried out study tours of the Hong Kong film industry, such as the pro-KMT Wader Studio (O Clarim 1954b, 6), since Macau lacked production capability or experience in full-length feature film-making. This was also done with a view to establishing a film industry in Macau and fostering future and long-term collaborations with Hong Kong, which never happened on the large-scale initially envisioned.

For the shooting of Long Way, Eurasia hired Hong Kong ‘free bloc’ technicians and actors working in Mandarin cinema. These were the increasingly popular Zhong Qing, the well-established Wang Hao, and Lola Young (Yang Luona). Zhong Qing had begun her career a few years before at the Taishan Studio where Albert Young worked, while Wang Hao had been working at Wader Studio when Machado and Ferreira visited and they were introduced to one another (O Clarim 1954b, 6). At the time Zhong Qing and Wang Hao were both starring in the multi-cast pro-KMT film The Sacrifice (Reference Bu Wancang1954) ‘by the vocally pro-Taiwan Xinhua studio’ (Fu Reference Fu2018, 23). In 1955, these two actors found themselves working for Asia Pictures, a Hong Kong company that had been established in 1953 for the purpose of making anti-communist films. Asia Pictures had close links with Taiwan and was also funded by TAF.Footnote 34 Eurasia emphasized their cast's ‘free bloc’ connections. Press releases pointed out that Zhong Qing had been part of the committee travelling to Taiwan in 1954 to celebrate Chiang Kai-shek's inauguration as president of the Republic of China (O Clarim 1954g, 4) and that Lola Young, a Sino-French Eurasian, was the daughter of a high-ranking KMT official (Revista da Semana 1954a). Historian Fu Poshek (Reference Fu2018, 22) has pointed out that the trip was part of ‘Taiwan's involvement in Hong Kong's Cinematic Cold War’.

Thus Eurasia collaborated with Hong Kong film professionals closely linked to the ‘free bloc’ who shared the same anti-communist ideology. Macau's Huaqiao bao (1954, 6) revealed that the Hong Kong actors were carefully selected after the producers gathered all kinds of information on them, and that all equipment was rented from the Nanyang/Shaw Brothers Studio, which was also part of the ‘free bloc’.

The Hong Kong connection was also crucial in terms of technology, know-how, facilities, and the networks it provided. Editing and post-production had to be done in Hong Kong, as Macau did not have the necessary facilities. Without the Hong Kong connection, Eurasia's functioning capability would have been much more limited and the making of the film would have been fraught with difficulties due to the lack of experience, technicians, equipment, and artists in Macau. A critique of the film's premiere particularly praised the Hong Kong contribution, saying that the Chinese actors and the photography were good, while the amateur Portuguese actors (Irene Matos and José Pedro) were not as skilled (Religião e Pátria 1955, 1075).

This was not the first Macau-Hong Kong cinematic collaboration. Young had been the cinematographer of all the 1952 films directed by Malheiro in Macau, and all post-production and editing work had been done in Hong Kong, which enabled the films to come to fruition (Noticias de Macau 1952d, 4). Most critiques of Malheiro's documentary Macau again praised the Hong Kong contribution. One of them read: ‘The beautiful and clear images honour […] Albert Young’ (Noticias de Macau 1952b, 6). Another observed that ‘the photography is good and clear, and uses good angles’ (Noticias de Macau 1952c, 6), while the pickiest critic, though criticizing the film's shortcomings, noted: ‘the work by the Hong Kong laboratory is good’ (C.F.M. 1952, 5).

Even after Eurasia's dissolution, Young continued to collaborate on films made in Macau in the 1950s and 1960s.

Release and the 400 Years celebration of Macau

Long Way was screened at the Victoria cinema in Macau during four days in November 1955 to mostly full houses. The governor, Lobo, and other officials attended its premiere (Macau, Boletim Informativo 1955, 6–7). The governor and Lobo were thanked by Machado for their support of the film (Macau, Boletim Informativo 1955, 7). There were plans to show it in another Macau cinema—the Capitol—in its Chinese version (Noticias de Macau 1955a, 8), and in Hong Kong, Portugal, and cinemas across the world, which never materialized. In fact, the film's lifespan was cut short, for reasons that are not entirely clear. Oral history and secondary sources offer differing explanations on this matter.

In recollections about Long Way, Ferreira (Reference Ferreira2009) stated that the film had to give way to an American one at the Victoria cinema, that there was a conflict between him and other members of Eurasia on how to remedy the film's sound problems, and that he had backed away from the project. He also asserted that He Xian (Ho Yin), the ‘red capitalist’ to whom the cinema belonged and a pro-PRC figure who acted as an intermediary between the Portuguese administration and the PRC, opposed the film because he viewed it as competing with the Hong Kong film industry in which he had investments, and he had therefore requested Lobo to stop financing the film. In an interview, Machado reminisced that the film had had to be sent to Hong Kong to fix the sound problems (Saraiva Reference Saraiva2009). Journalist Li Fulin (Reference Li2009, 240) has written that Machado mentioned that celluloid could not be stored in Macau because conditions were unsuitable, so the film was sent to Hong Kong. Saraiva (Reference Saraiva2009) has suggested that the film was censored by the Portuguese administration because of Macau's negative image. However, it seems more likely that the film quickly disappeared from circulation due to its unflattering portrayal of the PRC (that is, refugees fleeing the latter stages of the Civil War and the newly established regime) and its association with the 400 Years celebration (Revista da Semana 1954a).Footnote 35

Long Way became associated with the commemoration of 400 years of the Portuguese presence in Macau that was to take place throughout the month of November. The commemorations aimed to affirm Portuguese sovereignty in Macau, and also ‘strengthen ties between Macau and the metropole’ (Religião e Patria 1953, 463), laud ‘Sino-Portuguese friendship’, and ‘also convince other parts of the world about this’ (Correia Reference Correia1954, 4). The commemoration, however, provoked fierce opposition in the PRC. In his memoir, Alexander Grantham, then governor of Hong Kong, writes that, on a visit to Beijing in October 1955, he met with Zhou Enlai who sternly informed him of Chinese opposition to the celebrations and insisted that they should be called off. By the end of the meeting, though, Zhou Enlai conceded to Grantham's (Reference Grantham1965, 186) suggestion ‘that one day's innocuous celebrations would be unobjectionable’. He recalls that there was a ‘thinly veiled threat that the communists would stir up trouble, and probably serious trouble, in the two colonies’ if the bulk of the commemorations were not cancelled. He later passed this message to the Portuguese governor, and the Foreign Office also informed the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs about this. The Chinese position greatly worried Macau's governor and on 21 October he cancelled the commemorations, the official excuse being that there was a lack of funds (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2000, 619).