Laura Weinstein and Murray Heimberg's 1961 divorce was highly contentious. A decade after divorcing, the couple, both college faculty members in Nashville, Tennessee, were still battling about support payments for their two minor sons. In May 1971, a clearly frustrated trial court judge ordered Mr. Heimberg to spend five weekends in jail for refusing to pay child support. On appeal, the Tennessee Court of Appeals not only reversed the “extremely harsh” jail sentence but also found that Mr. Heimberg's support obligation had been extinguished by a new law that lowered the age of majority in Tennessee from twenty-one to eighteen. With almost palpable relief, the appeals court noted that both sons were now over the new statutory age of majority and therefore declared that “Dr. Heimberg's legal duty to furnish maintenance, support, and education for these two sons [had] ceased” when each boy turned eighteen.Footnote 1

The Weinstein–Heimberg divorce, while perhaps unusually combative, raised legal issues that were far from unique. After the national minimum voting age was lowered to eighteen in 1971, most U.S. states immediately lowered their statutory ages of majority to eighteen as well. At common law, parents are required to financially support their children until they reach the age of majority, so state courts quickly began holding that under these new laws, noncustodial parents only had to pay child support until age eighteen, not twenty-one.Footnote 2 In the decades since, there has been extensive litigation about parents’ financial obligations toward children who are eighteen or older, particularly with respect to college costs.Footnote 3

It is somewhat surprising that state legislatures reacted to eighteen-year-old voting the way they did, however. During the three decades of debate over the minimum voting age, from 1942 through 1971, the idea of lowering the age of majority was anathema to both sides. Furthermore, right up until ratification, most state legislatures were hostile to lowering the voting age, let alone revising other age-based laws. And as a general matter, states usually conceptualize their own interest as forcing family members to financially support dependents—especially children—as much as possible. Yet as soon as the voting age was reduced to eighteen through constitutional amendment, the overwhelming majority of state legislatures promptly revised their state laws to make eighteen the new age of adulthood for practically everything, not just the right to cast a ballot.

On July 5, 1971, President Nixon signed the Twenty-Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which lowered the minimum voting age for state and federal elections from twenty-one to eighteen. While the amendment itself was the most quickly ratified constitutional amendment in U.S. history, beating out the record previously set by the Twelfth Amendment, eighteen-year-old voting had been nearly thirty years in the making. Congressional advocates offered the first proposals to lower the voting age in October 1942, right after Congress voted to lower the draft age to eighteen. The issue then surfaced periodically over the next three decades before really gaining steam in the late 1960s and ultimately culminating in the passage of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment.Footnote 4

The Congressional debates over the voting age suggest that federal legislators were focused almost exclusively on the age limit for the franchise, not other age-based laws. When lawmakers did refer to other laws that included minimum ages, it was to argue that the effective age of legal adulthood was already eighteen. Most obviously, advocates pointed often to the minimum draft age, but they also cited marriage, tort, tax, and criminal law. Representative Richard Ottinger's (D-NY) June 1970 remarks on the House floor are typical: “If an 18-year-old is mature enough to bear arms in defense of his country, if he is expected and required to pay taxes, if he can be tried as an adult in our courts, and if he has the right to marry at 18, then we have surely discarded the notion of immaturity at 18 in every area except enfranchisement.”Footnote 5

Significantly, such sweeping statements were not entirely accurate. Not all states had set an age of majority, but most of the ones that did set the age at twenty-one.Footnote 6 A few states put eighteen as the age of majority for women and twenty-one as the age for men.Footnote 7 And even in states without a single age of majority, the minimum age for entering into contracts was nearly always twenty-one, as was the drinking age and the age for carrying firearms.Footnote 8

For their part, advocates of eighteen-year-old voting emphasized that they wanted to lower only the voting age, not any other minimum age requirements, and they quickly batted down any suggestions to reduce the age of majority. Indeed, many legislators regarded such proposals as spoilers for the voting age question. In the middle of 1970 floor debate over the voting age, for example, Senator Jack Miller (R-IA) introduced an amendment that would have essentially prohibited any age-based restrictions over eighteen.Footnote 9 Senator Miller had long opposed lowering the voting age, however, and Senator Mansfield—a strong proponent of eighteen-year-old voting—carefully distanced himself from Miller's amendment, declaring that it “would tend to becloud and befuddle the issue of the vote.”Footnote 10

The age of majority question was even more toxic at the state level. During public referenda on lowering the voting age, opponents frequently introduced proposals to lower the age of majority and/or the drinking age to eighteen precisely in order to turn public sentiment against eighteen-year-old voting.Footnote 12 Indeed, the voting age issue itself was always more popular at the federal level than it was in the states. Particularly during the 1960s, there was much more support among members of Congress for lowering the voting age than there was among state legislators or voters in state referenda, both of whom regularly rejected proposals to reduce the voting age in their states.Footnote 13

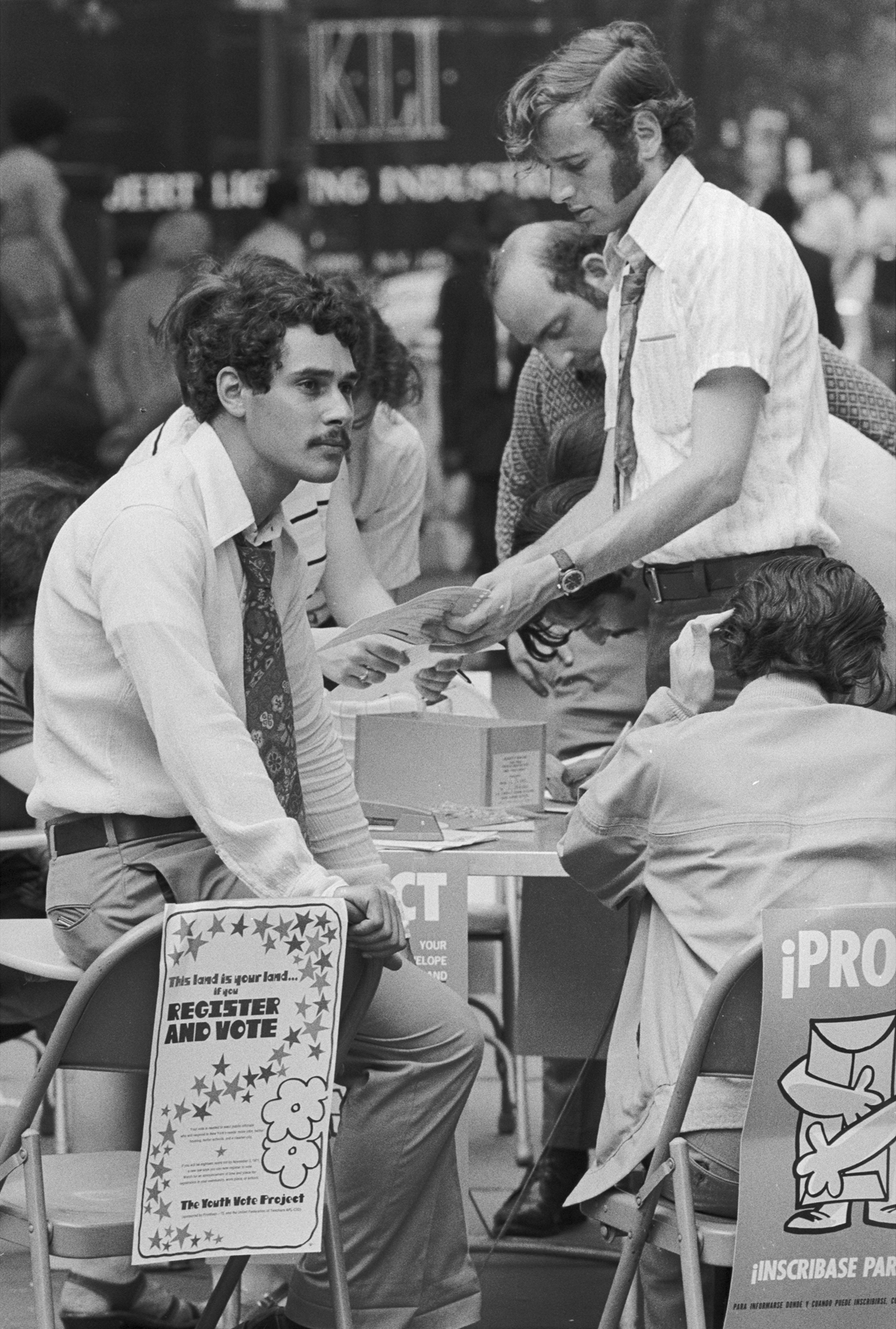

Figure 1. Registering young voters in New York City, summer 1971.Footnote 11

Nevertheless, immediately after the Twenty-Sixth amendment was ratified, states began lowering their ages of majority. About half the states took a gradual approach, establishing eighteen as the legal age for various matters over a period of several years. Other states just set eighteen as the new age of majority for everything. A couple of states set nineteen as the age of majority, and a very small minority of states did not do anything at all.Footnote 14 Mississippi, for example, still sets its age of majority at twenty-one.Footnote 15

Why this sudden change of heart among so many state legislators? To some extent, this phenomenon demonstrates that the voting age debate was not, in fact, just about young people casting ballots. Clearly the general idea that eighteen-, nineteen-, and twenty-year-olds were adults had a lot of momentum at the moment. As mentioned earlier, quite a few of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment's strongest proponents argued—in many cases incorrectly—that eighteen-year-olds were already legal adults for all intents and purposes, and that the franchise was just the final imprimatur of that status. This framing then carried over into state legislative discussions about the age of majority.Footnote 16

It is also very plausible that once eighteen- to twenty-year-olds had the franchise, politicians thought that removing other age-based restrictions would appeal to these new voters. Both the Republican and Democratic platforms of 1972 included language saying that the age of majority should be reduced to eighteen.Footnote 17 In particular, lowering the drinking age might have been an especially attractive issue for elected officials trying to woo young voters.

For the most part, though, state legislative efforts to lower the age of majority in the 1970s seemed more haphazard than calculated.Footnote 18 There were a few naysayers who warned of the potentially far-reaching consequences of these legal changes, including not only for child support obligations but also foster care, juvenile justice, welfare, liability for auto accidents, and nonresident college tuition.Footnote 19 Nonresident tuition became an issue almost immediately, in fact, as students began registering to vote in towns where they went to college and then claiming they should pay in-state tuition. By May 1972, there were already lawsuits pending in Maryland, Michigan, North Carolina, California, and Kansas, and states quickly began setting new residency term requirements for in-state tuition.Footnote 20

The main sticking point for lowering the age of majority was the drinking age. In state after state, the only real opposition to setting eighteen as the age of majority was with respect to allowing eighteen-, nineteen-, and twenty-year-olds to buy and serve alcohol.Footnote 21 In the states that followed a gradual approach to lowering the age of majority, the drinking age was inevitably the last thing to be reset.Footnote 22

In the immediate short term, concerns about reducing the drinking age to eighteen swamped discussion about nearly all other possible consequences of changing the age of majority. In 1976, the Supreme Court took up the issue of gender discrimination in the form of a case challenging an Oklahoma law that set eighteen as the minimum age for women to buy 3.2 beer but restricted sales to men until age twenty-one.Footnote 23 The drinking age would continue to be a significant public policy matter throughout the 1970s, as traffic accidents involving young drivers skyrocketed in the many states that had lowered their drinking ages to eighteen.Footnote 24 The issue culminated in 1984, when Congress passed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act, which withholds federal highway funds from states that set their drinking ages below twenty-one.Footnote 25

In the longer term, though, the duration of noncustodial child support became a significant family law issue. A sharp rise in nonmarital families, the greatly increased value and cost of a college education, and expanded federal involvement in enforcing child support obligations dramatically magnified the consequences of the changes made during the 1970s. Today, both state legislatures and courts continue to grapple with questions about post-majority child support and whether divorced parents can, or should, be ordered to contribute to their children's college education.

Over the last few years, there has been a surge of interest, particularly among progressives, in lowering the voting age yet again, perhaps to sixteen.Footnote 26 While it would be a stretch to declare the aftermath of the Twenty-Sixth amendment a cautionary tale, those involved in this issue would do well to bear in mind the powerful historical relationship between the voting age and state laws governing parents’ financial obligations to their children.