Taxation is the lifeblood of a modern liberal democracy. It is the one policy area without which nearly all of the other functions and aspects of the state would not be possible. Yet in the face of this reality, many Americans continue to believe that they can receive the goods and services provided by a modern regulatory, administrative, social-welfare state with low taxes and limited government. Many politicians and everyday Americans have even perpetuated the myth that they are “overtaxed” compared to the citizens of other advanced, industrialized nations.Footnote 1

Unsurprisingly, political leaders opposed to increased government spending frequently perpetuate the myth of the “overtaxed” American. “I oppose any new spending programs which will increase the tax burden,” Richard Nixon proclaimed in 1972 as he accepted the Republican Party's presidential nomination.Footnote 2 “The truth is that Americans are overtaxed, not undertaxed,” Newt Gingrich claimed in 1993. “Besides, it's not the people who need to sacrifice, it's the bloated Government.”Footnote 3 More recently, false claims about high American taxes have also provided political cover for tax cuts. “We're the highest taxed nation in the world,” President Donald Trump has repeatedly asserted. “People want to see massive tax cuts.”Footnote 4

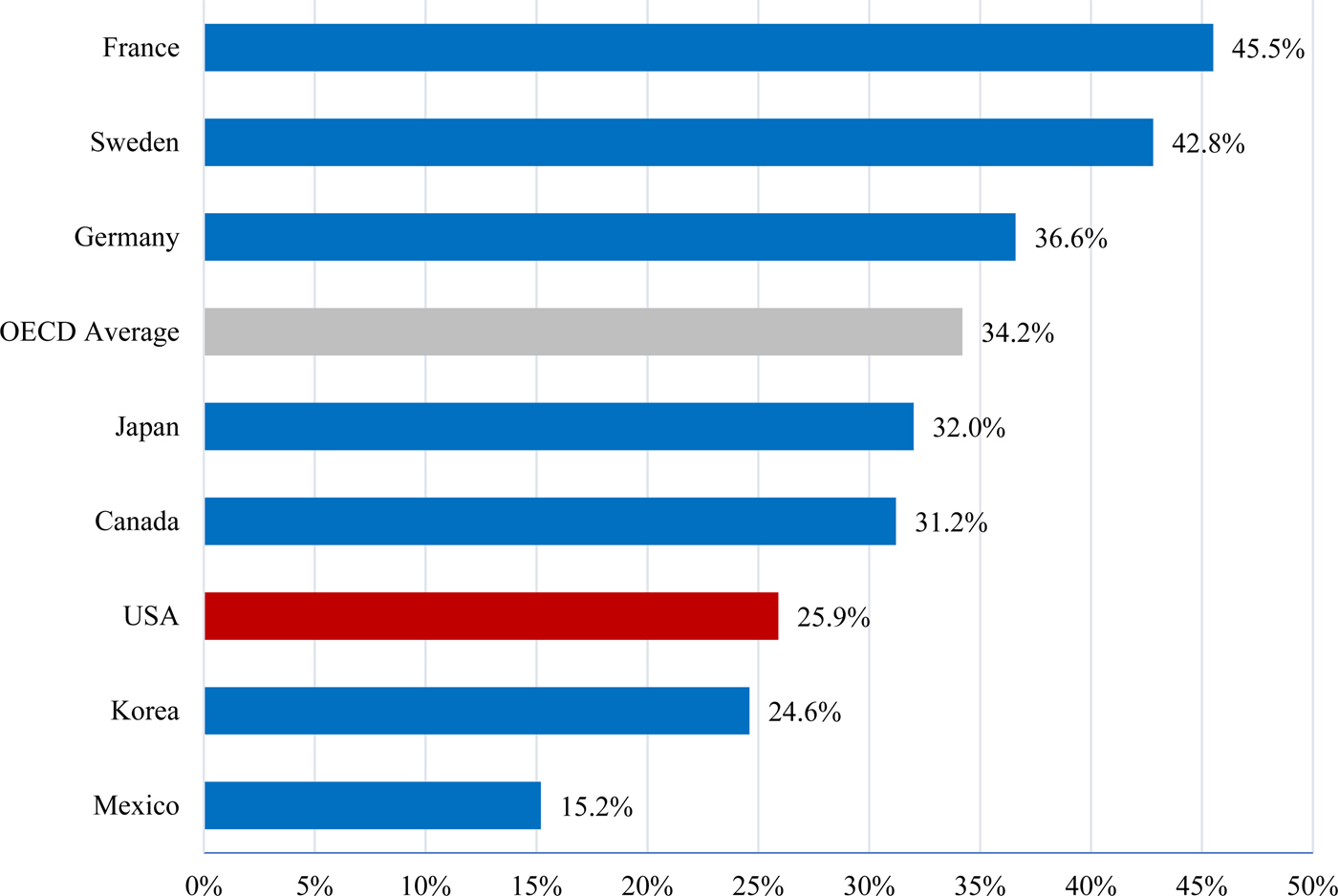

Despite these claims, there is little comparative empirical evidence to support the fable of the “overtaxed American.” Even a cursory examination of well-known statistics shows that the United States is a stark outlier in how little it taxes its citizens. Not only is the United States well behind other advanced countries in the total amount of taxes raised as a portion of national income; more conspicuously, the United States is one of the few industrialized nations without a national consumption tax such as a value-added tax (VAT). Indeed, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United States is among the least taxed industrialized nations in the world, with a total taxes/GDP ratio of roughly 26 percent, well below the OECD average of 34 percent for 2014. (See Table 1 and Chart 1.) This fact has been historically consistent since the post–World War II period.Footnote 5

Chart 1. International comparison of total taxes as a percentage of GDP, 2014. Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “Revenue Statistics – OECD Countries: Comparative tables,” OECD, last modified Nov. 30, 2016, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REV (accessed Mar. 27, 2018).

Table 1. International Comparison of Total Taxes as a % of GDP, 2014

* Income, profits taxes: composed of income, profits, and capital gains of individuals and corporates.

∧ Other includes the OECD subcategories: “other” general taxes on goods and services, taxes on specific goods and services, and unallocable taxes on production, sales, transfer, etc.

# Unallocable taxes: The OECD database does not specify the contents of this category, but does distinguish between those paid exclusively by business, and those not.

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “Revenue Statistics – OECD Countries: Comparative tables,” OECD, last modified Nov. 30, 2016, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REV (accessed Mar. 27, 2018).

One reason for this stark difference is the U.S. resistance to a national consumption tax. Whereas nearly all other OECD countries have a national consumption tax, usually in the form of a VAT, the United States has throughout its modern fiscal history rejected any type of federal consumption tax. Since the VAT accounts, on average, for about 7 percent of total taxes/GDP among OECD countries, the U.S. rejection of a VAT explains much of the American shortfall in total taxation as a percentage of GDP.Footnote 6

Although the notion of “American exceptionalism” has in recent years come under increasing scholarly scrutiny, there appears to be something genuinely unique about American fiscal policy.Footnote 7 Why is the United States such an outlier when it comes to national taxes? Why have Americans historically resisted national consumption taxes?

Part of the answer may have something to do with the relationship between taxes and spending. There is considerable empirical evidence indicating that regressive consumption taxes, like a VAT, are highly correlated with robust public-sector, social-welfare spending.Footnote 8 This correlation may help explain the U.S. resistance to a VAT. In fact, there is an old Washington, DC saying, frequently attributed—apocryphally perhaps—to Harvard University economist and former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, which states that the VAT has not been adopted in the United States because liberals fear that it will have a regressive impact on low-income Americans, and conservatives fear that it will be a “money machine” for big government.Footnote 9

There may be a great deal of truth to this adage. But determining precisely why American liberals and conservatives have consistently rejected national consumption taxes requires a long historical view. Complex and changing historical conditions, seminal events, and contingent forces have shaped contemporary American tax law and political economy. In the language of the historical social sciences, the U.S. resistance to the VAT has been a “path-dependent process.” During past “critical junctures,” American lawmakers “locked-in” U.S. tax policy with particular political decisions, and have subsequently created “feedback mechanisms” that have ossified the U.S. resistance to national consumption taxes.Footnote 10

Rejecting national consumption taxes was not, however, the only path that was historically available to Americans. Throughout the twentieth century, there were several moments of plasticity when U.S. policy makers could have adopted a crude form of federal consumption taxes, but chose not to. Exploring those historically contingent moments of contestation may help explain why the United States has continued to reject national consumption taxes.

The first of these critical junctures came in the early 1920s, during the aftermath of the First World War. At the height of the war, the U.S. national tax system had been transformed in response to the national emergency. A mildly progressive income tax, enacted in 1913 on the heels of the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment, was turned into a fiscal workhorse during the international conflict. Income tax rates skyrocketed from 7 percent in 1913 to a top rate of 77 percent in 1919. During the same period, exemption levels declined, bringing nearly 20 percent of American wage-earners onto federal tax rolls. Innovative “excess-profits” taxes on businesses were also adopted. Led by President Woodrow Wilson, the federal government actively transformed American state, economy, and society during the war.Footnote 11

After the Great War, when Republicans swept into office and took control of national policy-making, economic and political retrenchment soon became an integral part of the “return to normalcy.” Among the first targets was the robust wartime fiscal state. While some progressive and populist lawmakers sought to retain high income tax rates and innovative business levies to pay off war debts and to regulate large corporations, conservative business leaders and politicians sought to dismantle the steeply progressive wartime tax system. A mild postwar economic recession brought increased attention to tax policy. Prevailing economic and political conditions thus provided lawmakers with a unique opportunity to reconsider the future trajectory of American tax law and policy.Footnote 12

A national consumption tax was among the ideas in circulation at the time. Although a number of business leaders called for a national sales tax to replace the income tax, it was U.S. Treasury Department and Yale University political economist Thomas S. Adams who articulated the most sophisticated version of a national consumption tax as a complement to the existing income tax. Adams had a long and distinguished career as a “scholar in politics,” and his ideas and theories had a significant impact on fiscal policy-making, both at the state level when he was at the University of Wisconsin and at the federal level during his World War I tenure at the Treasury Department.Footnote 13

In a seminal 1921 journal article, Adams made the case for the administrative simplicity and economic efficiency of a national business sales tax. As an academic who spent a great deal of time working as a tax administrator, Adams was well-versed in the theoretical as well as the practical aspects of tax law and administration. His central goal was not to replace the fledgling progressive income tax with a regressive sales tax, as some conservative politicians had hoped. Rather, Adams had a sophisticated “scientific” vision of combining high-end progressive income taxes with a unique business tax on manufacturers and retailers and a series of smaller excise levies or commodity taxes “capable of clear definition and successful administration.” His ultimate objective was to ease the administrative burden on the existing tax system as a way to save the income tax. “The simple truth is that we are overburdening the income tax,” Adams argued. “Nothing is more common in the history of taxation than the demoralization of what has been a good tax, as taxes go, by increasing its rates until the breaking point is reached.”Footnote 14

A key component in Adams's broad-minded reform vision was a special kind of business sales tax. “In the case of producers and sellers of ‘goods, wares and merchandise’ further simplicity could be achieved,” he wrote, “by giving the tax the form of a sales tax with a credit or refund for taxes paid by the producer or dealer (as purchaser) on goods bought for resale or for necessary use in the production of goods for sale.” This specific proposal was arguably one of the first conceptual articulations of what tax experts today would call a “credit-invoice” method of value-added taxation. Adams can, thus, be seen as one of the intellectual godfathers of the VAT.Footnote 15

Despite his innovative economic ideas, Adams understood the political challenges of his time. After more than two decades of public service at the state and national level, he had come to realize that economic ideas did not exist in a vacuum, and that broader social and political factors frequently determined the development of fiscal policies. “The plan has little chance of adoption,” Adams presciently observed about his proposal toward the end of his 1921 essay. But that did not mean that one could not learn from this potential failure. In words that would resonate for decades, as future U.S. policy makers and analysts considered other forms of consumption taxes, Adams eloquently explained how and why the democratic desire for fairness and equity always seemed to trump the economic logic of simplicity and administrative ease. The failure to adopt a consumption tax serves “the useful purpose of illustrating the futility of basing one's principles on one's personal experience,” Adams conceded:

It demonstrates the supreme necessity of subordinating administrative logic and personal predilections to the great political and social forces which control the evolution of tax systems. These forces must be accepted as facts. The historical fact is that modern states prefer equity and complexity to simplicity and inequality. The cry for equality and justice is louder and more unanswerable than the demand for certainty and convenience. You may think it sentimental and stupid, but that does not alter the fact.Footnote 16

Adams's prediction soon came true. Although no lawmaker in 1921 endorsed the nuanced, proto-VAT that Adams had recommended, several crude forms of national sales taxes were proposed in Congress. Like European countries experimenting with sales taxes at the time, the United States in 1921 could have adopted a national sales tax; doing so may have led subsequently to the creation of a U.S. VAT. Indeed, some of the most effective VATs in existence today trace their roots to earlier more rudimentary forms of consumption taxes.

None of the sales tax proposals, however, was enacted in 1921. A fragmented business community, uncertain about how a new sales tax would affect its bottom line, refrained from supporting the new levy. Progressive activists exploited the business community's ambivalence and galvanized democratic support for equality and justice to retain the progressive income tax—just as Adams had anticipated. The democratic desire for fairness and complexity trumped the economic calls for efficiency and administrative simplicity. Eventually the early-1920s promise of radical and comprehensive tax reform dissipated into simple tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans.

If the 1920s were a critical juncture for American fiscal policy, the decision to reject Adams's recommendation and the other sales tax proposals seemed to lock in U.S. tax policy on a particular path. In the early 1940s, at the start of World War II and another moment of historical contingency, national lawmakers seriously reconsidered the idea of adopting a federal sales tax. But by then many U.S. states were already using sales taxes to fund their governments, thus creating tension between the states and the federal government over a consumption tax base.Footnote 17

During the 1970s, national lawmakers once again flirted with federal consumption taxes. The Nixon administration considered a VAT as a way to reform educational financing in the United States.Footnote 18 In 1979, House Ways and Means Chairman Al Ullman went so far as to propose a 10 percent national VAT. Both proposals quickly failed. Ullman lost his re-election bid in 1980, and many politicians thereafter became reluctant to recommend any kind of national consumption tax.Footnote 19

Today, the notion of the United States joining the rest of the advanced, industrialized world by adopting a VAT seems highly unlikely. Although a recent tax reform proposal floated by Congressmen Paul Ryan and Kevin Brady in fall 2017 included a pseudo-VAT, the plan was eventually rejected by the Trump administration. Past moments of historical contingency, when the United States may have taken an alternative fiscal path, seem to be closed off—at least for now—and as a result everyday Americans and politicians, like Donald Trump, can continue to falsely assert that the United Sates is “the highest taxed nation in the world.”Footnote 20