Introduction

Wrightite, a new oxo-orthoarsenate mineral, was found by L.P. Vergasova and S.K. Filatov, in 1983, in the fumarole on the east side of the micrograben of the Second scoria cone of the Northern Breakthrough of the Great Tolbachik Fissure Eruption, Tolbachik volcano, Kamchatka, Russia. The temperature of the volcanic gases in the fumarole was 410–420°C and the vent was encrusted with ponomarevite K4Cu4OCl10, while piypite K4Cu4O2(SO4)4·(Na,Cu)Cl prevailed at a depth of 0.5 m. The bottom of the visible part of the fumarole was encrusted with sylvite KCl. Minor phases in the sylvite-crusted part of the fumarole included dolerophanite Cu2OSO4, euchlorine KNaCu3O(SO4)3, lammerite Cu3(AsO4)3, johillerite NaCuMg3(AsO4)3, urusovite CuAlO(AsO4), bradaczekite NaCu4(AsO4)3, filatovite K(Al,Zn)2(As,Si)2O8, hatertite Na2(Ca,Na)(Fe3+,Cu2)(AsO4)3, hematite Fe2O3, ozerovaite Na2KAl3(AsO4)4 and tenorite CuO. Based on this mineralogical association, the formation temperature of the arsenate minerals is estimated as 500–600°C.

Reviews on the mineralization and fumarole activity of the Second scoria cone were reported by Vergasova and Filatov (Reference Vergasova and Filatov2012, Reference Vergasova and Filatov2016). The majority of arsenates from Great Fissure Tolbachik Eruption were discovered in the Arsenatnaya fumarole in the period 2014–2016 (Pekov et al., Reference Pekov, Zubkova, Yapaskurt, Belakovskiy, Lykova, Vigasina, Sidorov and Pushcharovsky2014a,Reference Pekov, Zubkova, Yapaskurt, Belakovskiy, Vigasina, Sidorov and Pushcharovskyb, Reference Pekov, Zubkova, Belakovskiy, Yapaskurt, Vigasina, Sidorov and Pushcharovsky2015a,Reference Pekov, Zubkova, Yapaskurt, Belakovskiy, Vigasina, Sidorov and Pushcharovskyb, Reference Pekov, Yapaskurt, Britvin, Zubkova, Vigasina and Sidorov2016a,Reference Pekov, Zubkova, Yapaskurt, Polekhovsky, Vigasina, Belakovskiy, Britvin, Sidorov and Pushcharovskyb). Hatertite (Krivovichev et al., Reference Krivovichev, Vergasova, Filatov, Rybin, Britvin and Ananiev2013) was only found in the fumarole on the east side of micrograben of the Second scoria cone. The discovery of other arsenate minerals (bradaczekite and filatovite) from the Second scoria cone was reported by Filatov et al. (Reference Filatov, Vergasova, Gorskaya, Krivovichev, Burns and Ananiev2001, Reference Filatov, Krivovichev, Burns and Vergasova2004).

The mineral is named wrightite (Russian Cyrillic: райтит) in honour of Adrian Carl Wright, Emeritus Professor at the University of Reading, UK, for many years the Professor in Amorphous Solid State Physics. Professor A.C. Wright was born in 1944. He is a well-known expert in structural studies of glass-forming systems. His works (Wright, Reference Wright2010; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Dalba, Rocca and Vedishcheva2010) are very important for understanding processes in both synthetic and natural (volcanic glass) systems. The mineral and its name were approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association (IMA2015–120). The type material is deposited at the Mineralogical Museum, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia (catalogue no. 1/19653).

Appearance and physical properties

Wrightite crystals are tabular, colourless to light yellow and transparent with an average size of 0.05 mm × 0.03 mm × 0.005 mm (Fig. 1). Well-formed crystals are very rare. Formation of aggregates occurs due to intergrowths of crystals along a flattened plane. The lustre is vitreous and the streak is white. The mineral is brittle; the hardness could not be determined due to the small crystal size. The determination of wrightite properties was in association with other arsenate minerals and in close intergrowth with sylvite. The density calculated from the empirical formula and single-crystal data is 3.499(1) g/cm3.

Fig. 1. Scanning electron microscope image of a tabular crystal of wrightite.

Optically the mineral is biaxial (−), with α = 1.679(2), β = 1.685(2), γ (calc.) =1.687 and 2V measured using the Wright method = 62(10)° (λ = 589 nm). The X and Y directions are located in the plane of tabular crystals, other orientation details are not obvious; tabular crystals have a positive sign of elongation. No pleochroism is observed.

Chemical data

Quantitative elemental microanalysis for 11 grains was carried out using an electron microprobe TESCAN ‘Vega3’ equipped with an Oxford Instruments X-Max 50 silicon drift EDS system operated at 20 kV and 0.445 nA and with a beam size of 0.22 µm. Analytical results are given in Table 1. No elements other than those listed here were detected. The empirical formula based on 9 O atoms per formula unit is (K1.69Na0.38)Σ2.07(Al1.80Fe0.24)Σ2.04As1.96O9. The simplified formula is K2Al2As2O9 which requires K2O 22.1, Al2O3 23.9, As2O5 54.0, total 100.0 wt.%.

Table 1. Analytical data (in wt.%) for wrightite.

S.D. – standard deviation.

Powder X-ray diffraction data

Powder X-ray diffraction data were collected from three grains using a Rigaku R-AXIS RAPID II (Gandolfi mode and CoKα radiation). An additional experiment was performed on a powdered sample of wrightite with sylvite impurities using a Rigaku MiniFlex II with CuKα radiation. This data was consistent with that collected on the Rigaku R-AXIS RAPID II. The measured and calculated powder diffraction data are given in Table 2. The unit-cell parameters, a = 8.230(5), b = 5.555(4), c = 17.584(1) Å and V = 803.9(6) Å3, were calculated from these data using the least-squares method in the programme PDWIN (Fundamensky and Firsova, Reference Fundamensky and Firsova2009). The diagnostic lines are [d,Å(I)(hkl)] are: 8.77(36)(002); 6.01(18)(102); 4.458(17)(111); 4.097(16)(112); 4.010(19)(201,013); 3.875(19)(104); 3.003(16)(204); and 2.972(100)(015)

Table 2. Powder X-ray diffraction data (d in Å) for wrightite (Gandolfi mode, CoKα radiation).

The strongest lines are given in bold.

Crystal-structure determination

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected using a Bruker Smart APEX diffractometer equipped with CCD detector. A hemisphere of three-dimensional data was collected using MoKα X-radiation and frame widths of 0.5° in ω, with 60 s used to acquire each frame. The data were corrected for Lorentz, polarization and background effects using the Bruker programs APEX and XPREP. A semi-empirical absorption-correction based upon the intensities of equivalent reflections was applied in the Bruker program SADABS.

The structure was solved by charge flipping and refined on the basis of 1924 unique observed reflections using the Jana2006 program suite (Petříček et al., Reference Petříček, Dusek and Palatinus2014) (Table 3). The crystal structure was refined on the basis of F 2. Refinement of all atom-position parameters, allowing for the anisotropic displacement of all atoms, and the inclusion of a refinable weighting-scheme of the structure factors, resulted in a final agreement index (R 1) of 0.043, calculated for the 1924 independent reflections, and a goodness-of-fit (S) of 1.56. Atomic coordinates, atomic displacement parameters and selected bond distances are summarized in Tables 4–6. Projections of the crystal structure, coordination polyhedra of alkali cations and coordination of the additional oxygen atom are provided in Figs 2–4. The crystallographic information file has been deposited with the Principal Editor of Mineralogical Magazine and is available as Supplementary material (see below).

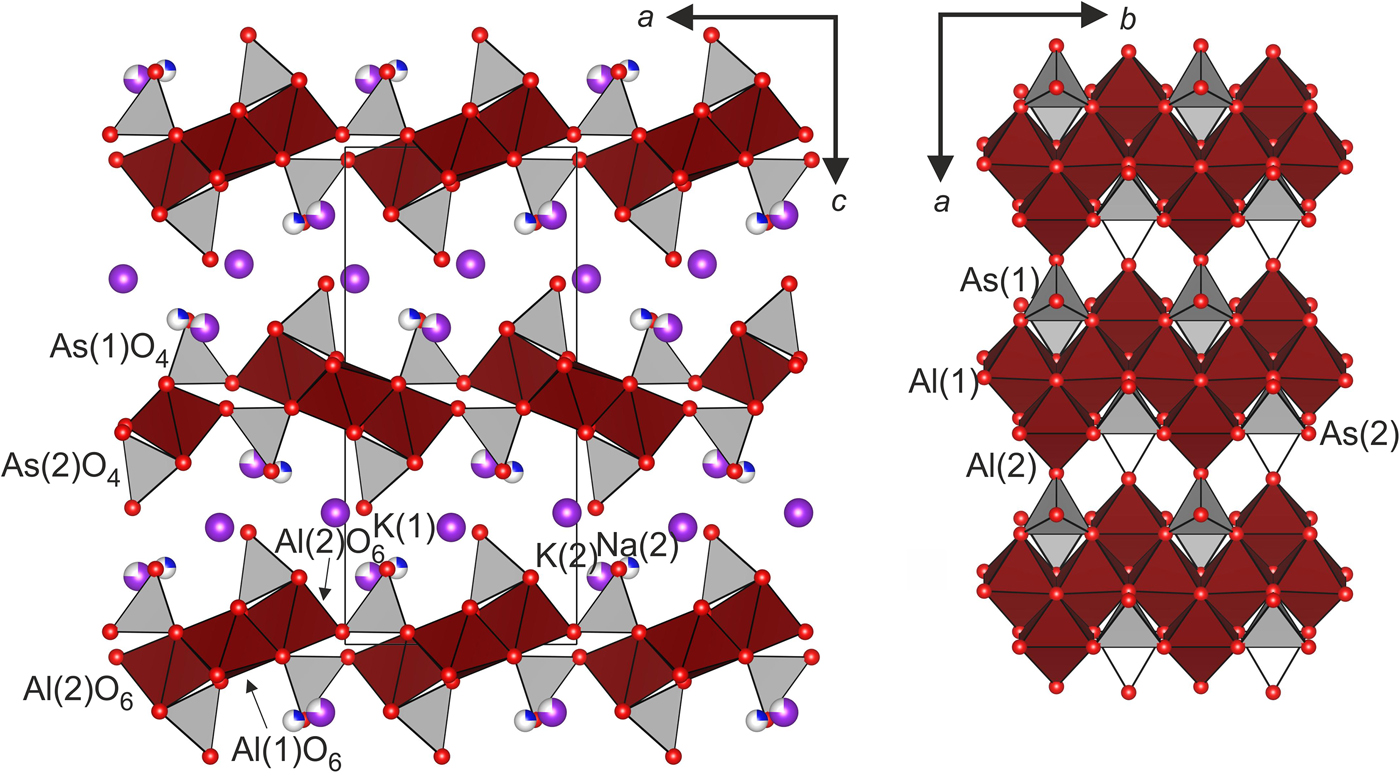

Fig. 2. Crystal structure of wrightite: (left) crystal structure; and (right) zigzag chains of AlO6 octahedra.

Fig. 3. Coordination of alkali elements in the crystal structure of wrightite: (a) K1O9 polyhedra; and (b) splitting of the M2 site into Na2' and K2' sub-positions.

Fig. 4. Coordination of the additional oxygen atom, O1, in the crystal structure of wrightite.

Table 3. Crystal data and data collection parameters.

Table 4. Atomic coordinates and isotropic or equivalent displacement parameters (Å2).

*U iso; Occ. = occupancy

Table 5. Atomic displacement parameters (Å2)*.

*Na2' and K2' parameters are constrained to be the same.

Table 6. Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond-valence sums.

Symmetry codes: (i) x–1, y, z; (ii) –x + 2, y + 1/2, –z; (iii) x, y–1, z; (iv) x, –y + 1/2, z; (v) x + 1, y–1, z; (vi) x + 1, y, z; (vii) x, –y–1/2, z; (viii) –x + 1, y + 1/2, –z; (ix) –x + 1, –y, –z; (x) x–1, –y + 1/2, z; (xi) x–1/2, –y + 1/2, –z + 1/2; (xii) x–1/2, y, –z + 1/2; (xiii) x–1, y + 1, z; (xiv) –x + 3, y–1/2, –z; (xv) –x + 3, y + 1/2, –z; (xvi) –x + 2, –y, –z; (xvii) x, y + 1, z.

Discussion

Wrightite is orthorhombic, space group Pnma, with a = 8.2377(3), b = 5.5731(6), c = 17.683(1) Å, V = 811.8(1) Å3 and Z = 4.

The crystal structure of wrightite is similar to those of the synthetic analogues such as NaKAl2O(AsO4)2 (Yania et al., Reference Yania, Nilges, Rodewald and Pottgen2010; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Wang and Lii1997; Boughzala and Jouini, Reference Boughzala and Jouini1997). This structure consists of Al2O(AsO4)2 layers in the ab plane (Fig. 2a). Each layer contains two independent isolated AsO4 tetrahedra and two AlO6 octahedra. AlO6 octahedra are linked by edges, forming zigzag chains along the b axis inside the Al–As layer (Fig. 2b). Eight- and seven-coordinated K atoms are located in the interlayer space between layers.

There are two sites for alkaline elements: M1 and M2. The M1 site is only occupied by K atoms. The K1 cation is surrounded by nine oxygen atoms with bond lengths of 2.719−3.632 Å and forms a distorted polyhedra K1O9 (Fig. 3a). The bond-valence sum for K1 is 0.89 valence units (vu). The M2 site splits into the K2’ and Na2’ sub-positions, and the coordination of K2’ and Na2’ is different. K2’ polyhedra are eightfold-coordinated with one short bond length, 2.451 Å, and seven bond lengths varying over the interval 2.804−2.965 Å. The bond-valence sum for K2' is 1.07 vu (Table 7). The excess of the ideal value of 1 is caused mainly by the short bond in the K2'O8 polyhedron. Na2' is coordinated by seven oxygen atoms with bond distances in the range of 2.434−2.965 Å and a bond-valence sum of 0.12 (Fig 3b). The distance between K2’−Na2’ sub-positions is 1.00(2) Å.

Table 7. Bond-valence analysis for wrightite.

Bond valences for positions with occupation not equal to unity are marked with an asterisk.

Parameters from Brown and Altermatt (Reference Brown and Altermatt1985).

The Al1O6 octahedron is only occupied by Al. The Al1 site is located in the inversion centre and it forms an octahedron with bond lengths in the range of 1.818−1.936 Å. The Al2 site occurs in a very distorted octahedron with the distance range varying from 1.826 to 2.148 Å. An additional oxygen O1 is coordinated by three Al atoms with bond lengths ranging from 1.818 to 1.891 Å (Fig. 4).

The connection of AlO6 octahedra via shared O–O edges leads to the convergence of three Al3+ octahedra on the O1 atom. This approach may be excessive and causes the repulsion of Al atoms from each other. There are two ways Al atoms can be repulsed from each other: (1) by extending the Al–O bonds; or (2) the Al–Al distance can be increased by shortening the shared edges O–O of the AlO6 octahedra. Analysis of the values of the interatomic distances Al–O and O–O allows us to determine which of these mechanisms occurs. In accordance with the first mechanism, the Al–O bonds in the Al–O–Al chains are on average 1.95 Å, which is 0.06 Å more than the average value of the bonds of O atoms with an Al atom (1.89 Å) (Fig. 4). In accordance with the second mechanism, all three shared edges have a reduced length (their average value is 2.52 Å) relative to the average length of the unshared edges of 2.68 Å (Fig. 4). So, both mechanisms of repulsing Al atoms from each other are actually realized in the crystal structure of wrightite.

The AsO4 tetrahedra are slightly distorted; and the average As−O bond length in the crystal structure is 1.68 Å in As1O4 and 1.69 Å in As2O4. In comparison with the average As5+−O bond length of 1.66 Å indicated in Janssen et al. (Reference Janssen, Janner, Looijenga-Vos and de Wolff2006), the above values can be considered as acceptable.

Wrightite, K2Al2O(AsO4)2, is the first mineral of the K2Fe2O(AsO4)2 structure type (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Wang and Lii1997). The similar inorganic compound, NaKAl2O(AsO4)2, was synthesized by a gas transport reaction method in an alumina tube (Yania et al., Reference Yania, Nilges, Rodewald and Pottgen2010). K2Fe2O(AsO4)2 and Rb2Fe2O(AsO4)2 have been obtained by the solid-state reaction method from KH2AsO4 (or RbH2AsO4) and Fe2O3 (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Wang and Lii1997). Rb2Cr2O(AsO4)2 has been prepared by solid-state reactions from Rb2CO3, Cr2O3 and NH4H2AsO4 (Boughzala and Jouini, Reference Boughzala and Jouini1997). All inorganic analogues crystallize in the same space group, Pnma, and their unit-cell parameters vary depending on the composition. The comparison of crystal chemical parameters of wrightite and synthetic analogues are listed in Table 8. In the crystal structure of Rb2Fe2O(AsO4)2, one of the Rb atomic positions is split into two sub-positions (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Wang and Lii1997). In the crystal structure of wrightite, the position of K2’/Na2’ is also split. A possible reason for splitting is the difference between cation sizes.

Table 8. Crystal chemical parameters of wrightite and synthetic isotypes (space group Pmna, Z = 4).

Refs: [1] this work; [2] Chang et al. (1997); [3] Boughzala and Jouini (1997); and [4] Yania et al. (2010).

The Al2/Fe2–O distances and bond-valence sums indicate clearly that Fe is 3+ . In the synthetic analogues of wrightite, K2Fe2O(AsO4)2 and Rb2Fe2O(AsO4)2, the trivalent state of Fe has been confirmed by Mössbauer data.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank S.N. Britvin for help in operating the Rigaku R-AXIS RAPID II diffractometer, Peter Leverett, Antony Kampf and an anonymous referee for valuable comments. X-ray measurements were performed in the XRD Research Centre of St. Petersburg State University.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1180/minmag.2017.081.091