INTRODUCTION

In a transition economy like China, firms are embedded in an environment with underdeveloped institutions and various deficiencies in laws and enforcement (Peng & Health, Reference Peng and Heath1996). To leverage loopholes for benefits, firms may be tempted to engage in opportunistic behaviors (Luo, Reference Luo2006; Zhao, Reference Zhao2006). As such, the public has witnessed a significant increase in industry scandals, such as melamine additives in the milk industry in 2008, illegal cooking oil in the food industry in 2010, and plasticizers in the liquor industry in 2012. Although researchers have expended great efforts to understand firms’ opportunistic behaviors in developed countries (e.g., Jonsson, Greve, & Fujiwara-Greve, Reference Jonsson, Greve and Fujiwara-Greve2009; Lamin & Zaheer, Reference Lamin and Zaheer2012), we still have little systematic knowledge of these behaviors in other countries such as China.

Opportunism, defined as ‘self-interest seeking with guile’ (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985: 47), has two major forms discussed in different research streams but with little conversation. First, from the perspective of transaction cost economics, within-dyad opportunism (WDO) involves actions by one firm that are directly detrimental to the interests of a partner; for example, one buyer firm may lie about certain things or take advantage of the holes in the contracts to protect its interests in a relationship with the supplier (Wathne & Heide, Reference Wathne and Heide2000; Williamson, Reference Williamson1985). Second, pro-relational opportunism (PRO) discussed in the ethical decision-making literature (Moore & Gino, Reference Moore and Gino2013; Umphress, Bingham, & Mitchell, Reference Umphress, Bingham and Mitchell2010) involves violations of societal norms that do not directly work against a partner but affect society as a whole. For example, in the melamine additive scandal in 2008, Sanlu Group was caught adulterating milk powder with melamine, while hundreds of distributors and partner firms were found to have collaborated with Sanlu Group to distribute poisoned milk for economic benefits. Their actions affected 39,965 babies and caused four deaths.

What are the consequences of WDO and PRO for business dyads? Although previous meta-analysis has found that WDO is negatively related to exchange performance (e.g., Crosno & Dahlstrom, Reference Crosno and Dahlstrom2008), the effects of PRO and the differences between WDO and PRO have not been empirically examined. Moreover, our understanding of the underlying mechanism through which WDO and PRO take effect is still very limited. Drawing on the identity and identification literature, we try to fill this gap. The notion of identity, or the central and distinctive characteristics of an entity, constitutes a ‘root construct’ (Albert, Ashforth, & Dutton, Reference Albert, Ashforth and Dutton2000: 13) for explaining phenomena across different levels (Ashforth, Rogers, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011). Firms define themselves in terms of their relationships with different business partners (Anderson, Håkansson, & Johanson, Reference Anderson, Håkansson and Johanson1994; Dyer & Nobeoka, Reference Dyer and Nobeoka2000). Such interorganizational identification enhances firm legitimacy, contributes to efficiency, and affects the cooperative – competitive balance (Ingram & Yue, Reference Ingram and Yue2008). However, when partner firms experience negative publicity, firms may worry about the stigma-by-association effect (Kulik et al., 2008) and dis-identify with the partner firms (Rao, Davis, & Ward, Reference Rao, Davis and Ward2000).

To fully understand the relationships between organizations, we must account for boundary spanners who engage in significant transactions with their counterparts in other firms (Ring & Van de Ven, Reference Ring and Van De Ven1994; Zaheer, McEvily, & Perrone, Reference Zaheer, McEvily and Perrone1998). Boundary spanners strive to construct personal identity via their relationships with the counterparts, which significantly affects exchange performance at the interorganizational level (Ellis & Ybema, Reference Ellis and Ybema2010; Marchington & Vincent, Reference Marchington and Vincent2004). Such interpersonal identification is even more meaningful in the context of opportunism, because of ‘the banality of evil’ (Arendt, Reference Arendt1963/2006): what are the reactions of individuals when their firms are victims of WDO, or accomplices of PRO?

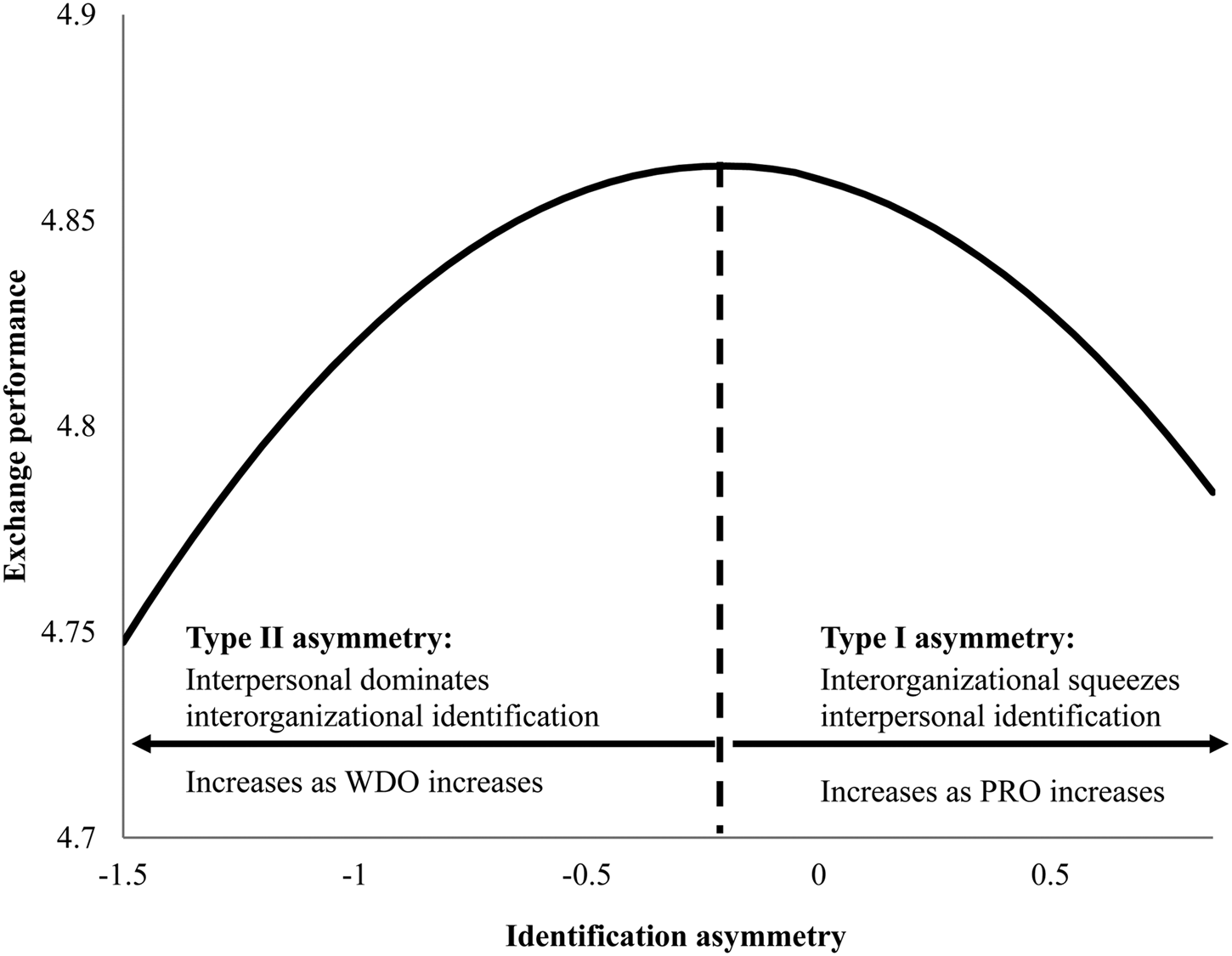

We propose a concept of identification asymmetry, which captures the extent to which interorganizational identification between firms and interpersonal identification between boundary spanners are out of balance.[Footnote 1] When interorganizational identification is much stronger than or even squeezes out interpersonal identification (Type-I asymmetry), exchanges focus on de-personalized, structural, and routine firm-to-firm interactions, and boundary spanners just follow the orders of their firms (Ellis & Ybema, Reference Ellis and Ybema2010; Zaheer et al., Reference Zaheer, McEvily and Perrone1998). In contrast, when interpersonal identification is much stronger than or even dominates interorganizational identification (Type-II asymmetry), exchanges focus on informal and relational person-to-person interactions and firms just provide support for boundary spanners (Adler & Kwon, Reference Adler and Kwon2002). For instance, Chinese firms rely heavily on personal connections to do business, while using formal relations as ex post backup (Li, Reference Li2007; Zhou & Poppo, Reference Zhou and Poppo2010).

Firms and boundary spanners enact their respective identities through different social processes of interactions, negotiation, and sense-making (Sluss & Ashforth, Reference Sluss and Ashforth2007, Reference Sluss and Ashforth2008). Thus, we argue that WDO and PRO trigger different dynamics of identification at different levels, leading to different degrees of identification asymmetry, and further influencing exchange performance in business dyads. In sum, we propose a model in which identification asymmetry mediates the effects of WDO and PRO on exchange performance. Opportunism involves very high risks which force firms to calculate the transaction cost and gains of such behaviors. One of the most important factors affecting the transaction cost calculus and the reaction to partner behaviors is fairness (Ariño & Ring, Reference Arino and Ring2010; Husted & Folger, Reference Husted and Folger2004; Ring & Van de Ven, Reference Ring and Van De Ven1994). Thus, we suggest that both distributive and interactive fairness are relevant in interorganizational relationships (IORs). We argue that distributive fairness (Folger & Konovsky, Reference Folger and Konovsky1989) increases a firm's tendency to collude with the partner for gains, while interactive fairness (Luo, Reference Luo2007) facilitates trust and reduces the boundary manager's concern about the counterpart manager's identity being contaminated by an opportunistic firm.

We aim to contribute to the literature in the following ways. First, we try to empirically differentiate between WDO and PRO in the context of transition economy like China. The prevalence of two kinds of opportunism, the enhanced tensions of identity asymmetry (e.g., Chinese people tend to focus on more interpersonal than interorganizational issues), and the significant losses caused by such opportunism and Machiavellian reasoning all make our study important to both theory and practice. Second, by simultaneously considering identification at the interorganizational and the interpersonal levels, we empirically explore an integrative view of identification between levels and confirm that WDO and PRO affect exchange performance through either Type-I or Type-II asymmetry. Third, we examine the important roles of fairness perceptions and differentiate the effects of different fairness in the identification process. Thus, we provide new insights into the opportunism and identity literature. Taken together, we enrich and expand our understanding of relational dynamics across levels. We present our theoretical framework in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Interorganizational versus Interpersonal Identification in IORs

Identity captures the central, distinctive, and enduring characteristic of an entity (Whetten, Reference Whetten, Bartel, Blader and Wrzesniewski2007) and describes how the entity answers the question ‘who am I or who are we as an entity’? (Albert & Whetten, Reference Albert, Whetten, Cummings and Staw1985), while identification refers to the ‘perception of oneness or belongingness to some human aggregate’ (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989: 21). At the IOR level, some researchers focus on the role of prototype-based de-personalization and social categorization in reducing uncertainty (Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2000), while others highlight the extent to which members of a group of firms develop a set of mutual understandings on the core characteristic of the group as a whole. For example, Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Håkansson and Johanson1994) propose a concept of network identity while Dyer and Nobeoka (Reference Dyer and Nobeoka2000) demonstrate that Toyota's suppliers develop a network identity that facilities knowledge sharing between Toyota and its suppliers.

However, the literature on identity and identification across levels is scant compared with research on identity and identification at a single level (See a detailed comparison in Table 1). Identification at the interorganizational and interpersonal (i.e., boundary managers) levels both are relational – that is, they aim to develop relational identity (Hogg, van Knippenberg, & Rast, Reference Hogg, van Knippenberg and Rast2012). At the interorganizational level, the manufacturer–supplier relational identity focuses on the role relationships between a manufacturer and a supplier. The role of the manufacturer may be assumed to provide accurate requirements for products, while the role of the supplier may be assumed to provide products of good quality. However, although a supplier may have a clear sense of what it means to be a supplier vis-à-vis its manufacturer, the supplier may not define itself in terms of its relationship with the manufacturer. In a similar vein, at the interpersonal level, the purchasing manager–sales manager entity emphasizes the role relationships between a purchasing manager from a manufacturer and a sales manager from a supplier. Thus, interpersonal identification captures the extent to which the purchasing (sales) manager defines herself/himself in terms of the relationship with the sales (purchasing) manager.

Table 1. Taxonomy of literature on identity and identification

Research on the relationship dynamics at the interorganizational and interpersonal levels has tended to focus on convergence across levels. For example, Narayandas and Rangan (Reference Narayandas and Rangan2004) find that initial asymmetries between weaker firms and their more powerful partners decreased because interpersonal trust across the dyad increased interorganizational commitment. Interpersonal trust among boundary spanners and interorganizational trust exert positive effects on each other (Zaheer et al., Reference Zaheer, McEvily and Perrone1998). The focus on convergence across levels has contributed important insights, but also produced inconsistent and sometimes anomalous results. For example, Zaheer et al. (Reference Zaheer, McEvily and Perrone1998) find that interorganizational trust is strongly negatively related to negotiation costs while interpersonal trust is anomalously positively related to negotiation costs. Extant literature is still silent on whether identification across levels is different in relationship dynamics.

In this study, we aim to show that imbalance across levels are important for examining business exchanges in the interfirm setting. Interorganizational and interpersonal identification are different in at least the following aspects. First, the content of interorganizational identification differs from that of interpersonal identification. For example, while interpersonal identification includes three necessary components (Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, van Knippenberg and Rast2012) – cognition (awareness of the relationship), evaluation (awareness related to some value connotations), and emotion (an emotional investment in the awareness and evaluations) – emotion is less applicable to interorganizational identification. In contrast, interorganizational identification is characterized by shared purposes, common frameworks for action, and institutionalized coordinating routines. For example, when firms identify with each other, they will ‘feel a shared sense of purpose with the collective’ (Dyer & Nobeoka, Reference Dyer and Nobeoka2000: 352). Kogut and Zander (Reference Kogut and Zander1996) also argue that shared identity does not only lower the costs of communication, but also establishes explicit and tacit rules of coordination and influences the direction of search and learning.

Second, the natures of the underlying relationships in interorganizational and interpersonal identification are quite different. Interpersonal identification is often intrinsic in boundary spanners’ self-definitions (Sluss & Ashforth, Reference Sluss and Ashforth2008); it may not be instrumental at all, but be purely affective (Gulati, Lavie, & Madhavan, Reference Gulati, Lavie and Madhavan2011). In contrast, interorganizational identification is more likely to be used as a utilitarian approach for organizational goals such as operational and strategic autonomy (Salk & Shenkar, Reference Salk and Shenkar2001), relational cohesion (Khanna & Rivkin, Reference Khanna and Rivkin2006), and legitimation and competition effects (Li, Yang, & Yue, Reference Li, Yang and Yue2007).

Third, the consequences of interorganizational and interpersonal identification are distinct. If individuals identify with each other, boundary spanners may transfer the affect generated to the related organization, become more likely to socially influence each other, and behave in ways that benefit their counterparts. Therefore, interpersonal identification makes boundary spanners more likely to exchange favors and gifts (Adler & Kwon, Reference Adler and Kwon2002). In contrast, interorganizational identification drives firms to invest relationship-specific assets, exchange critical information, and build routines for knowledge learning (Corsten, Gruen, & Peyinghaus, Reference Corsten, Gruen and Peyinghaus2011; Dyer & Nobeoka, Reference Dyer and Nobeoka2000).

Finally, the change patterns of interorganizational and interpersonal identification are different. Identity is by definition enduring, permanent, unchanging, and stable (Whetten & Mackey, Reference Whetten and Mackey2002). When identity is threatened, a process of relational disidentification occurs (Sluss & Ashforth, Reference Sluss and Ashforth2007). However, interorganizational and interpersonal identification vary in their pace of change (quick versus slow), source of change (organizational actions versus individual actions), and effect of change on exchange performance (direct versus indirect). For example, although interorganizational identification may be abruptly shifted or even terminated, interpersonal identification may continue to persist (Havila & Wilkinson, Reference Havila and Wilkinson2002).

In summary, in IORs, interorganizational and interpersonal identification may demonstrate different levels of strength. Our focus in this study is not identification at each level but the simultaneous consideration of both levels. We conceptualize the concept of identification asymmetry to capture the extent to which identification between firms and between boundary spanners are out of balance. In the next section, we propose that WDO and PRO result in different relational identification and disidentification processes at different levels and thus affect identification asymmetry. We also examine the boundary conditions of the process and the exchange performance effect of identification asymmetry.

Opportunistic Behavior as a Threat to Identity

Relational identification reflects the extent to which firms view a relationship as part of their definition of self and an extension of self (Aron & Aron, Reference Aron, Aron, Ickes and Duck2000). Such relational identification is based on the evaluation of role-based characteristics (e.g., shared value and goals, Anderson & Weitz, Reference Anderson and Weitz1992) and firm-based characteristics (e.g., trustworthiness, Dyer & Chu, Reference Dyer and Chu2003). Depending on the other's actions and interactions, partners actively process information and evaluate whether the relational aspects they value (as part of their own identity) are confirmed or threatened. Thus, the established relationship roles are subject to reassessment. The reassessment outcomes may lead to relational identification or disidentification. Although many types of partner actions may threaten relational identity, we focus on opportunistic behavior, which occurs frequently and threatens long-term relationships in IORs.

WDO has long been the interest of the transaction cost economics (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985) while PRO is a hot topic in the ethical-decision-making literature (Moore & Gino, Reference Moore and Gino2013). However, these two streams of research have flourished largely on their own with little conversation (See the summary of studies in Table 2). We try to examine their effects simultaneously in the IOR setting. Recall that we define Type-II identification asymmetry as an imbalance in which interpersonal identification between boundary spanners dominate interorganizational identification between the firms. Examples of Type-II identification asymmetry is documented in Anderson and Jap (2005) in which the anonymous supplier and the automaker do not identify with each other while their own personnel build good relationships with each other. We argue that the damaging effects of WDO on interorganizational identification are stronger than those of WDO on interpersonal identification, leading to a move toward Type-II identification asymmetry.

Table 2. Summary of existing literature on different kinds of opportunism in interfirm settings

One of the most important roles of relational identification is to create sets of positive behavioral expectations associated with the roles of and relationship between partners (Sluss & Ashforth, Reference Sluss and Ashforth2007), such as seeking mutual benefits, sharing critical knowledge, and following formal and informal agreements (Dyer & Nobeoka, Reference Dyer and Nobeoka2000; Luo, Reference Luo2001). However, WDO leads to the reassessment of the partner's characteristics because it is directly detrimental to the interests of the firm. As WDO is target-specific, the victim firm is more likely to attribute the transgression to an enduring characteristic of the partner (Kim, Dirks, & Cooper, Reference Kim, Dirks and Cooper2009). Moreover, WDO violates positive expectations in a negative way, which can lead to intense negative reactions such as forced negotiation, stricter and more rigid formal governance, and even relationship termination (Heide & John, Reference Heide and John1990; Wathne & Heide, Reference Wathne and Heide2000). Thus, both the partner's role-based (e.g., supplying qualified products/services) and organization-based (e.g., this supplier is responsible) identities have negative valences. The firm begins to doubt the viability of the existing relationship roles and the characteristics of the partner. Thus, interorganizational disidentification occurs.

WDO may also negatively affect interpersonal identification among boundary spanners, who are motivated to search for information on their counterparts to affirm a positive social identity for themselves. If boundary spanners of one firm perceive that their counterparts are affiliated with a firm conducting WDO toward their firm, their interpersonal identification may decrease.[Footnote 2] However, we argue that this kind of decrease is less severe than interorganizational identification, as interpersonal identification is a lower-order identity and much slower in change pace (Ashforth & Johnson, Reference Ashforth, Johnson, Hogg and Terry2001). Research has shown that individuals tend to identify more strongly with lower- rather than higher-order identities (Riketta & van Dick, Reference Riketta and Van Dick2005). Thus, idiosyncratic information about what boundary spanners find more distinct and attractive about distant higher-order identities (e.g., interorganizational identity) is missing (Wieseke, Kraus, Ahearne, & Mikolon, Reference Wieseke, Kraus, Ahearne and Mikolon2012). In contrast, boundary spanners find relational identity with their counterparts – a localized and concrete identity – more attractive. Although they may question their counterparts who are affiliated with the partner firm conducting WDO toward their firm, they are more likely to attribute the affiliation and their counterparts’ ignorance of WDO to external reasons such as obedience to authority and codes of conduct (Brass, Butterfield, & Skaggs, Reference Brass, Butterfield and Skaggs1998; Ellegaard, Reference Ellegaard2012; Trevino, Reference Trevino1986). Their counterparts are also perceived to have less control over WDO. Thus, the boundary spanners are less likely to blame their counterparts, resulting in a smaller decrease in interpersonal identification. In sum, WDO decreases interorganizational identification much more than it affects interpersonal identification. Therefore, we make the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: WDO will be positively related to identification asymmetry (Type II).

Type-I identification asymmetry refers to a kind of imbalance in which interorganizational identification squeezes out interpersonal identification. Examples of Type-I asymmetry are found in the literature. The interviews conducted by Zaheer et al. (Reference Zaheer, McEvily and Perrone1998) showed that some purchasing managers had limited identification with their suppliers whereas their firms displayed higher level of identification due to institutionalized routines of exchange. Bachmann (Reference Bachmann2001) also found that German businessmen do not need to develop interpersonal identification because interorganizational identification is higher in a powerful institutional framework. We contend that PRO affects interorganizational identification only slightly while decreases interpersonal identification to a larger extent. As mentioned, interorganizational identification tends to be more instrumental for organizational gains. Therefore, PRO, as a Machiavellian way of realizing relational rents, may decrease interorganizational identification only slightly. The firm may prioritize self-serving over pro-social interests, develop motivated blindness (Gino, Moore, & Bazerman, Reference Gino, Moore and Bazerman2008), and attribute the partner's unethical behavior to external reasons such as collaborative goals (Barsky, Reference Barsky2008; Schweitzer, Ordóñez, & Douma, Reference Schweitzer, Ordonez and Douma2004), customer demands (Bennett, Pierce, Snyder, & Toffel, Reference Bennett, Pierce, Snyder and Toffel2013), and external competition (Charness, Masclet, & Villeval, Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014).

Moreover, PRO makes the firm view the partner as an in-group member and use different norms to judge the partner's behavior (Moore & Gino, Reference Moore and Gino2013). For instance, Rao et al. (Reference Rao, Davis and Ward2000) finds that strong ties to in-group members (NASDAQ members) reduced the effects of identity-discrepant cues and decreased firms’ defections to the New York Stock Exchange. Thus, PRO may not lead to the relational disidentification process but even increase interorganizational identification. In practice, we observe that some firms still outsource production to offshore subcontractors that enjoy production cost advantages related to extremely low labor and environmental standards (Hill, Eckerd, Wilson, & Greer, Reference Hill, Eckerd, Wilson and Greer2009).

In contrast, PRO decreases interpersonal identification. Although PRO still involves actions taking place at distant levels, boundary spanners may begin to question the characteristics of their counterparts who are affiliated with the firm conducting PRO. Boundary spanners may still attribute the counterparts’ ignorance of PRO to external reasons such as obedience to authority. However, they will add more factors to their attributions because PRO violates societal norms (Ganesan, Brown, Mariadoss, & Ho, Reference Ganesan, Brown, Mariadoss and Ho2010). Boundary spanners may view their counterparts as proponents of profiting at the expense of society because the partner firm conducting PRO represents the social identity of these counterparts. Boundary spanners may also view their counterparts as being high in complicity, which would make it more difficult for these counterparts to elicit understanding from the boundary spanners (Lange & Washbum, Reference Lange and Washburn2012). To affirm ‘positive distinctiveness and avoid negative distinctiveness by distancing themselves from incongruent values and negative stereotypes’ (Elsbach & Bhattacharya, Reference Elsbach and Bhattacharya2001: 393), boundary spanners may develop negative relational categorizations of themselves and their counterparts, leading to interpersonal disidentification.

In sum, PRO affects interorganizational identification only slightly or even increases it but decreases interpersonal identification. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: PRO will be positively related to identification asymmetry (Type I).

Identification Asymmetry and Exchange Performance

At each level, relational identification may have positive effects on exchange performance (defined as a firm's satisfaction with its partner firm). For example, interorganizational identification increases operational and market performance because it increases trust, drives firms to invest relationship-specific assets, and facilitates information sharing (Corsten et al., Reference Corsten, Gruen and Peyinghaus2011; Dyer & Nobeoka, Reference Dyer and Nobeoka2000). Interpersonal identification may also improve exchange performance because it brings the firms together, creates flexibility and responsiveness, and facilitates the accumulation of bilateral moral obligations. Embeddedness and moral obligations then motivate firms to demonstrate their allegiance to a cooperative group, leading to resource contribution, value creation, and profit sharing. However, combining interorganizational and interpersonal identification, we argue that identification asymmetry may have complicated effects on exchange performance.

When interorganizational identification is much stronger than interpersonal identification, a higher level of Type-I asymmetry occurs which leads to an IOR functioning mainly upon formal relationships. A high level of interorganizational identification facilitates the development of common frameworks for action and the institutionalization of coordinating routines for knowledge sharing (Dyer & Nobeoka, Reference Dyer and Nobeoka2000). However, a low level of interpersonal identification makes the implementation of shared goals less likely because flexibility and responsiveness are missing, bargaining and coordination costs are higher, and boundary spanners may intentionally distort important information (Dyer & Chu, Reference Dyer and Chu2003). Based on a single longitudinal case study, Salk and Shenkar (Reference Salk and Shenkar2001) also provided empirical evidence to such argument. Interorganizational identification overrides interpersonal identification to a large extent, making it impossible for organizations to reap the benefits of boundary managers’ efforts. Thus, as Type-I asymmetry increases, exchange performance decreases.

When interorganizational identification is much weaker than interpersonal identification, a higher level Type-II asymmetry occurs which leads to an IOR mainly functioning upon informal relationships. A low level of interorganizational identification results in the underdevelopment of the common frameworks for action and makes coordinating routines for knowledge sharing less likely to be institutionalized. Although high interpersonal identification is helpful for interactions and exchanges, a low level of interorganizational identification results in a lack of shared goals and loosely organized interactions. Moreover, high interpersonal identification may hurt exchange performance because it mainly drives boundary spanners to exchange favors and gifts (Adler & Kwon, Reference Adler and Kwon2002). These favors and gifts may not be congruent with the goals of IORs, and they thus cannot fully account for the economic benefits that firms derive from interorganizational identification (Gulati et al., Reference Gulati, Lavie and Madhavan2011). Boundary spanners may try to preserve their relational identities at the expense of organizational benefits, leading to the costs of reciprocal favors exceeding the gains. Such phenomena is especially prevalent in China (Chen, Chen, & Huang, 2013; Lin, Lu, Li, & Liu Reference Lin, Lu, Li and Liu2015). For example, Chen, Chen, and Xin (Reference Chen, Chen and Xin2004) documented that managers use their positions and firm resources to benefit those with whom they have interpersonal ties at the expense of the firm. Thus, as Type-II identification asymmetry increases, exchange performance decreases.

Notice that we do not imply that we have to develop a very accurate balance between interorganizational and interpersonal identification. Rather, we highlight a dynamic and situational balance (Li, Reference Li2015). Case studies by Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Lu, Li and Liu2015) help understand our hypotheses. They compare how returnee and local firms balance formal (e.g., interorganizational) and informal (e.g., interpersonal) business exchanges and find that at first returnee firms preferred formal to informal elements whereas local firms preferred informal to formal elements in customer relationships. However, over time returnee firms placed increased importance on informal elements while local firms emphasized more on formal elements. Such kind of firms can achieve better performance (Li, Reference Li2015). Thus, in this study we highlight the degree of asymmetry and argue that as identification asymmetry moves from Type-II (interpersonal identification stronger than interorganizational identification) to Type-I (interorganizational identification stronger than interpersonal identification), we should observe that exchange performance first increases and then, beyond a certain threshold (i.e., the identification fit point), begins to decrease, resulting in an inverted U-shaped relationship. In sum, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Identification asymmetry will have a curvilinear (inverted U-shaped) relationship with exchange performance.

To build a mediation model, we need to link WDO and PRO directly with exchange performance. We argue that WDO is negatively related to exchange performance, for two reasons. First, WDO increases transaction costs in business dyads because partners have to design complex governance mechanisms to screen, negotiate, and monitor each other's behavior (Nooteboom et al., 1997). Second, WDO escalates inter-party conflicts and thus increases coordination difficulty and uncertainty between partners, making the value-creation of interfirm collaboration less likely (Luo, Reference Luo2006). Thus, we posit,

Hypothesis 4: WDO will be negatively related to exchange performance.

Regarding PRO, however, we argue that it is positively related to exchange performance. PRO is not directed specifically against a partner, and thus it will not directly threaten another's immediate interests. Instead, PRO may benefit the relationship as a whole, even at the expense of society as a whole. In such circumstances, a firm may even view another firm engaging in PRO as a more reliable partner. This case is much more prevalent in China, in which in-group favoritism drives firms to value partners that can protect their interests even to the point of circumventing the law (Farh, Tsui, Xin, & Cheng, Reference Farh, Tsui, Xin and Cheng1998; Hwang, Reference Hwang1987). Such reciprocity, in terms of favors and collective gains, facilitates relationship development and resource exchange and thus increases exchange performance. Ganesan et al. (Reference Ganesan, Brown, Mariadoss and Ho2010) have also provided empirical evidence that buyers are more tolerant of suppliers’ unethical behaviors. Thus, we propose,

Hypothesis 5: PRO will be positively related to exchange performance.

In addition to their direct effects on exchange performance, based on Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3, we suggest that WDO and PRO also take effect indirectly through the identification process at different levels. Specifically, WDO negatively affects exchange performance by pushing identity asymmetry toward Type-II asymmetry, while PRO negatively influences exchange performance by pushing identity asymmetry toward Type-I asymmetry. Therefore, we make the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6a: Identification asymmetry will partially mediate the negative effect of within-dyad opportunism on exchange performance.

Hypothesis 6b: Identification asymmetry will partially mediate the negative effect of pro-relational opportunism on exchange performance.

The Moderating Roles of Fairness Perceptions

In this section, we examine the boundary condition of the opportunism – relational identification process. Based on our logic, the factors that can alter the attribution reasoning of the victim firm or the boundary spanners should influence the opportunism – identification asymmetry relationship. Specifically, we focus on fairness perceptions because ‘justice (fairness) is a foundation for all types of economic transactions’ (Luo, Reference Luo2008: 27) and adds equity considerations to the typical efficiency (e.g., opportunism for benefits) considerations in IORs, providing a more comprehensive explanation of interorganizational interactions and exchanges (Ariño & Ring, Reference Arino and Ring2010; Ring & Van de Ven, Reference Ring and Van De Ven1994).

Fairness is a perception ‘that a decision, outcome, or procedure is both balanced and correct’ (Husted & Folger, Reference Husted and Folger2004: 720) and is usually a relative evaluation based on comparisons of efforts (i.e., value creation) and gains (i.e., value capture) to others’ efforts and gains (Luo, Reference Luo2007; Poppo & Zhou, Reference Poppo and Zhou2014). Based on the literature, we focus on opportunism – identification asymmetry and highlight and distinguish between distributive and interactive fairness. Distributive fairness refers to the evaluation of an outcome related to an allocation decision, such as the value a firm captures from the value creation process with its partner (Ariño & Ring, Reference Arino and Ring2010). A firm that captures compensation matching its role behavior, recognized status, and risks taken will experience distributive fairness (Luo, Reference Luo2007; Poppo & Zhou, Reference Poppo and Zhou2014). Interactive fairness refers to the extent to which partners perceive the nuances of interpersonal treatment to be fair and respectful (Luo, Reference Luo2007). Interactive fairness is characterized by heightened communication and socialization and bolsters relational attachment. We argue that these two kinds of fairness influence the identification process differently.[Footnote 3]

Distributive fairness positively moderates the relationship between PRO and identification asymmetry, mainly by affecting the interorganizational identification process. Higher perceived distributive fairness confirms the expectations of the firm that does not conduct PRO and highlights the belief that the partner firm is a loyal in-group member (Moore & Gino, Reference Moore and Gino2013). Thus, the firm is more likely to develop ‘motivated blindness’ (Gino et al., Reference Gino, Moore and Bazerman2008) and to seek more external reasons to morally justify the partner's unethical behavior. Moreover, a firm extending itself to a partner conducting PRO entails high risks and vulnerabilities. A questionable partner creates status anxiety (i.e., concerns about being devalued; Jensen, Reference Jensen2006) and uncertainty from stakeholders, such as the public (Jonsson et al., Reference Jonsson, Greve and Fujiwara-Greve2009), customers (McLane, Bratic, & Bersin, Reference McLane, Bratic and Bersin1999), and investors (Zuckerman, Reference Zuckerman1999). Higher distributive fairness provides the firm with a means to cope with the anxiety and uncertainties it encounters, making it more likely to prioritize self-serving interests over pro-social ones (Barsky, Reference Barsky2008; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Ordonez and Douma2004). In contrast, when distributive fairness is lower, the firm (i.e., the manufacturer) has no incentive to bear the risks and uncertainties related to the partner firm's (i.e., the supplier) PRO. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 7: When perceived distributive fairness between the manufacturer and supplier is higher, the relationship between PRO and identification asymmetry will become stronger.

Interactive fairness moderates these relationships, largely by affecting the interpersonal identification process. In the IOR setting, interactive fairness mainly involves two-way respect and communication between firms (Luo, Reference Luo2007). When interactive fairness is higher, boundary spanners and their counterparts respect each other more, and their communication is more open and timely. They thus provide sensegiving regarding their firms’ behavior and their attitudes about that behavior (Ashforth, Harrison, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Harrison and Corley2008). Sensegiving can enable the counterparts to guide the meaning construction of boundary spanners toward a preferred redefinition of their relational reality (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Reference Gioia and Chittipeddi1991). Through the development of understanding and consensus and communication, boundary spanners are more likely to attribute their counterparts’ ignorance of the partner firm's opportunistic behavior to external reasons, mitigating the negative effects of WDO and PRO on interpersonal identification. However, when interactive fairness is lower, misunderstanding occurs and negative attitudes, hostility, and factionalism increase (Pearce, Reference Pearce1997; Salk & Shenkar, Reference Salk and Shenkar2001), thus increasing boundary spanners’ tendency to attribute the ignorance of opportunism to the characteristics of their counterparts. As interactive fairness does not directly affect the relationship between opportunism and interorganizational identification, we make the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 8a: When interactive fairness between the manufacturer and supplier is higher, the negative relationship between WDO and identification asymmetry will become stronger.

Hypothesis 8b: When interactive fairness between the manufacturer and supplier is higher, the positive relationship between PRO and identification asymmetry will become weaker.

METHODS

Data and Sample

We tested the hypotheses with a matched sample of the manufacturer–supplier dyads across different industries in different locations of China. Our sampling frame consisted of all of the manufacturing firms in the electronic and electrical equipment and components manufacturing industry (industry codes 4011–4090) located in Jiangsu and Shanghai, the two most developed eastern areas in China. To collect the data, we collaborated with Industrial and Commercial Bureau of the local government and employed local research assistants and trained interviewers to conduct field surveys. Given the paucity of research differentiating between WDO and PRO, we first applied standard psychometric scale development procedures to develop a scale to measure WDO and PRO. Then, we attempted to identify scales verified by previous studies and obtained valid measurement items for other constructs.

We randomly selected 1,000 firms and called them to solicit their willingness to participate in the study. We asked the firms that were willing to participate to provide two informants (executives, regional managers, and/or purchasing managers) who were knowledgeable about the relationships with their primary suppliers. We interviewed the informants face-to-face, asked them to complete the questionnaire, and requested the names, addresses, and contact information of their primary suppliers. Afterward, we contacted the corresponding suppliers. We likewise asked for two informants to complete the questionnaire on the supplier side. We ensured the cooperation of the suppliers and accuracy of the responses by telling them that their manufacturers had completed a similar questionnaire, that there were no correct or incorrect responses, and that their responses would be kept confidential. We promised a copy of a best-selling business book and a copy of the research report to both the manufacturers and suppliers in exchange for their participation.

Of the target sample, 104 firms could not be reached and 433 refused to cooperate. The remaining 463 firms agreed to participate. Of the 463 potential primary suppliers provided by these manufacturers, 15 firms could not be reached, 134 firms refused to participate, and 59 firms returned significantly incomplete questionnaires. Thus, we succeeded in collecting questionnaires from 255 manufacturer–supplier dyads, for an effective response rate of 25.5% (255 of 1,000 potential dyads).

The 255 manufacturing firms in the final sample represented the major subsections in the industry, including communication exchange equipment manufacturing (19.6%), electrical equipment manufacturing (18.1%), electronic computer machine manufacturing (16.9%), discrete semiconductor device manufacturing (14.2%), electronic components and component manufacturing (7.5%), audio-visual equipment manufacturing (4.8%), and others (18.9%). The average number of employees of these firms was 399, with a minimum of 50 and a maximum of 8,000. The average age of these firms was 14.86 years, with a minimum of 8 and a maximum of 59. In terms of annual sales income, 54.3% reported less than RMB30 million, 21.2% between RMB30 million and RMB60 million, 12.8 between RMB60 million and RMB100 million, and 11.7% more than RMB100 million.

We gathered secondary data about the manufacturers’ characteristics for both the responding and nonresponding firms to examine the nonresponse bias. The company archives were obtained from local bureaus of statistics. A comparison of the number of employees, firm assets, and annual sales volume across the two groups showed no statistically significant differences, so nonresponse bias does not appear to be a concern.

To minimize the potential for key informant bias in our field study, we surveyed the most knowledgeable informants, including procurement and sales managers, who were in charge of the interaction and cooperation between the manufacturer and primary supplier. A knowledge test based on a 7-point Likert scale indicated that the informants had adequate knowledge levels (mean = 5.49; SD = 1.01). The average length of experience the procurement managers had with the supplier was 2.54 years (SD = 1.38), and the average experience of the sales managers with the manufacturer was 3.95 years (SD = 2.04), so the key informants probably possessed adequate knowledge of the study issues.

Measures

We attempted to identify scales verified by previous studies and obtained valid measurement items, as we report in Appendix I. Notice that, we used key informant technique, a typical method of data collection used in interorganizational literature (for details, please see Kumar, Stern, & Anderson, Reference Kumar, Stern and Anderson1993) to collect data. The basic assumption of this technique is that key informants summarize either observed or expected organizational relations to generalize the patterns of IORs. The key informants answer the questionnaire from the viewpoint of the firm as a whole, not from the viewpoint of the informants themselves. A sample item, for instance, ‘Our relationship with the supplier is vital to the kind of organization with which our firm identifies’, implies that the informants answer the extent to which members in the firm collectively identify the supplier, based on the summary of their observations. Regarding to the measures of interpersonal identification, we anchored the informants to answer from their own viewpoint rather than their firms.

Within-dyad and pro-relational opportunism were developed from prior studies such as measures of opportunism (e.g., Jap & Anderson, Reference Jap and Anderson2003; Stump & Heide, Reference Stump and Heide1996), the interview records of case studies (e.g., Carter, Reference Carter2000), and items on unethical behavior (e.g., Ganesan et al., Reference Ganesan, Brown, Mariadoss and Ho2010). Sample items for WDO include ‘The supplier tries to take advantage of “holes” in our contract to further their own interests’ and ‘The supplier sometimes alters facts to get what it wanted from our firm’. Cronbach's α for the seven items of WDO was 0.88 for WDO. Sample items for PRO include ‘To benefit our relationship, the supplier sometimes exaggerates the truth about our products/services to clients’ and ‘Although we may not be competent enough, the supplier has recommended our firm to other firms in the hope of benefiting our relationship as a whole’. Cronbach's α for the five items of PRO was 0.87.

Identification asymmetry

We first needed to measure both interorganizational and interpersonal identification. We measured interorganizational identification as the extent to which the manufacturer identified with the supplier. Four items were adapted from Bhattacharya and Sen (Reference Bhattacharya and Sen2003) and Homburg, Wieseke, and Hoyer (Reference Homburg, Wieseke and Hoyer2009), sample items including ‘If someone criticized our relationship with the supplier, it would be an insult for our firm’ and ‘We are proud to tell others we collaborate with this supplier’. The items were answered by both the manufacturer and supplier. Cronbach's α was 0.87 for the manufacturer and 0.83 for the supplier. We used another four-item Likert-type scale to measure the interpersonal identification of the boundary managers from both the manufacturer and supplier, sample items including ‘If someone criticized my relationship with the manager, it would be a personal insult for me’ and ‘My relationship with the manager is vital to the kind of person I am at work’. Cronbach's α was 0.88 for the manufacturer manager and 0.90 for the supplier manager. We then calculated identification asymmetry as the difference between the average score of interorganizational identification and the average score of interpersonal identification.

Fairness perceptions

We adapted four items from Kumar, Scheer, and Steenkamp (Reference Kumar, Scheer and Steenkamp1995) to measure distributive fairness, the manufacturer's perception of the fairness of earnings and other outcomes it receives from its relationship with the supplier. For example, the manufacturer is asked to indicate how fair are its outcomes and earnings compared to ‘the effort and investment that we have made to support the supplier’. Cronbach's α was 0.90. To measure interactive fairness, we used four items adapted from Luo (Reference Luo2007) to capture the degree of perceived fairness of the nuances of interpersonal treatment between the boundary spanners of both firms. Cronbach's α was 0.87. Sample item includes ‘The representatives from the supplier and our representatives always communicate openly and directly’.

Exchange performance

Exchange performance refers to the extent to which exchanges between the manufacturer and supplier perform well. Four items were obtained from Bercovitz, Jap, and Nickerson (Reference Bercovitz, Jap and Nickerson2006), sample item including ‘We are satisfied with the outcomes from the collaboration with the supplier’. Cronbach's α was 0.93.

Controls

We also included multiple control variables in the questionnaires. Based on Gulati and Sytch's (Reference Gulati and Sytch2007) dyadic view of interorganizational relationships, when considering identification asymmetry, the total identification of interorganizational and interpersonal identification must be considered. We thus controlled for total identification by summing the scores of interorganizational and interpersonal identification. Exchange frequency could also influence the development of trust and the use of contracts, so we measured it with a frequency count of partners’ interactions. Whether the product is customized may influence the manufacturer's attitude toward the supplier. We thus controlled for customized product in the model. Firm size may influence organizational behavior and decisions because a large firm can commit more resources to the relationship and enjoys more bargaining power, thus influencing governance patterns. We measured firm size by the number of employees. Foreign firms may adopt different kinds of governance and interaction modes with their suppliers. We controlled for foreign ownership by coding foreign firms as one in the dummy variable. Past performance may influence a firm's willingness to continue the relationship (Ganesan, Reference Ganesan1994). We controlled for firms’ past profit to deal with this potential feedback effect of performance.

As environmental uncertainty – the extent to which changes in the external environment are unpredictable – creates exchange hazards, it can affect interorganizational exchange. We controlled for two kinds of uncertainty: market uncertainty (Cronbach's α was 0.73) and competition intensity (Cronbach's α was 0.67). Six items were adapted from Jaworski and Kohli (Reference Jaworski and Kohli1993). Performance uncertainty captures the degree of difficulty in assessing the actual performance of the supplier. It may affect the level of trust between the manufacturer and supplier. We controlled it using a five-item scale adapted from Heide (Reference Heide2003). Cronbach's α was 0.80. c, the extent to which a focal firm needs its partner to achieve its desired goals, is a critical determinant of governance choices because it affects firm risk perceptions (Gulati & Sytch, Reference Gulati and Sytch2007). We used four items from Lusch and Brown (Reference Lusch and Brown1996) to measure the manufacturer's dependence on the supplier. Cronbach's α was 0.70.

Construct Validity

We used the two-step approach to assess the validity of the multi-item measures. First, we conducted exploratory factor analysis for the multiple-item surveyed variables. The extracted factor solutions were as expected. Second, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses to assess the fit of our full measurement model. The results suggested the 11-factor model provided the best fit with our data according to our primary measurement model (χ2 = 2,200.46, df = 979, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.070, confirmatory fit index [CFI] = 0.94, non-normed fit index [NNFI] = 0.89). We also compared this primary measurement model against alternative (i.e., 1-, 3-, 6-, and 9-factor) models. A series of sequential chi-square difference tests confirmed that our model provided the best fit, as did the 90% confidence intervals of the RMSEA parameters and the Akaike information criterion.

The overall fit measures also achieved the recommended values, and the standardized item loadings on the hypothesized factors were significant. To examine the internal consistency and convergent validity, we calculated the construct reliability and average variance extracted (AVE). Almost all of the composite reliabilities were greater than 0.70, and most of the AVEs exceeded 0.50. Thus, our measures possess satisfactory reliability and validity. In Table 3, we report the correlations, means, and standard deviations for all of these variables.

Table 3. Correlations, means, and standard deviations

Notes: Two-tailed tests; n = 255. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Assessment of Common Method Biases

To address potential common method variance (CMV), we used several strategies to avoid it ex ante and to control it ex post (Rindfleisch, Malter, Ganesan, & Moorman, Reference Rindfleisch, Malter, Ganesan and Moorman2008). First, to avoid any potential CMV in the research design stage, we used information from different sources for our key measures with a time lag. In particular, we had more than one person answer the questionnaire as often as possible and incorporated data from multiple sources (e.g., survey and archive data) into the estimation model. Second, we designed complicated specifications for the regression models to create cognitive difficulties for respondents to infer the exact goal of the research. Specifically, we included a composite construct (i.e., identification asymmetry) and two first-stage moderators in our model, which made CMV less likely to affect our estimation. Third, we used a post hoc Harman one-factor analysis of all of the questionnaire-based variables to check whether the variance in the data can be largely attributed to a single factor. The test did not yield one overarching factor, suggesting the absence of CMV. Fourth, to further ensure that CMV bias was not a serious concern, we added a first-order factor (a single unmeasured latent method factor) to the hypothesized measurement model (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The increase in model fit obtained by accounting for the common method factor was not significant, and the variance extracted by the method factor was well below the 0.50 cutoff. Finally, we conducted a marker variable test (Lindell & Whitney, Reference Lindell and Whitney2001). We used a dummy variable theoretically unrelated to our principal constructs: whether the date of the questionnaires returned was an even number. The results showed that the average correlation between our principal constructs and the marker variable was –0.02 (p > 0.10). These efforts confirmed that the CMV bias was insignificant in this study.

RESULTS

We used OLS regression in study 2 to test our hypotheses. We centered the predictor variables in all of the analyses to reduce nonessential collinearity and increase the interpretability of the results (Dalal & Zickar, 2012). We examined the collinearity diagnostics of the OLS regression. The maximum variance inflation factor (VIF) for all of the models was 1.89 for the interaction term between PRO and interactive fairness, and the average VIF was approximately 1.34 in all of the models, well below the threshold of VIF. Therefore, multicollinearity does not appear to be a major concern.

Table 2 presents the regression results. For the effects of the control variables, customized product was positively associated with identification asymmetry, indicating that interorganizational identification is higher than interpersonal identification in the customized products context. Relationship duration was negatively associated with identification asymmetry, extending the findings of Zaheer et al. (Reference Zaheer, McEvily and Perrone1998) and Gulati and Sytch (Reference Gulati and Sytch2007) and showing that although relationship duration facilitates both interorganizational and interpersonal socialization, it facilitates the development of interpersonal identification more. The results also showed that market uncertainty was negatively related to identification asymmetry, indicating that the higher external uncertainty becomes, the greater the difference between interorganizational and interpersonal identification will be. For the exchange performance model, we found that performance uncertainty was negatively related to exchange performance, while total identification had a positive effect on exchange performance, consistent with previous findings (e.g., Corsten et al., Reference Corsten, Gruen and Peyinghaus2011).

As shown in Model 3 of Table 4, within-dyad opportunism had a negative and significant effect on identification asymmetry (b = −0.35, p < 0.001), whereas pro-relational opportunism displayed a positive and significant effect on identification asymmetry (b = 0.54, p < 0.001). Regarding to the effect size, one unit increase of within-dyad opportunism results in a 0.35 unit drop in identification asymmetry whereas one unit increase of pro-relational opportunism leads to 0.54 unit increase in identification asymmetry. Methodologically speaking, Type-I asymmetry increases with the increase of interorganizational or the decrease of interpersonal identification. In contrast, Type-II asymmetry increases with the decrease of interorganizational or the increase of interpersonal identification. Thus, within-dyad opportunism is positively related to Type-II asymmetry while pro-relational opportunism is positively related to Type-I asymmetry. Both H1 and H2 are supported.

Table 4. Regression on identification asymmetry and exchange performance

Notes: n = 255; unstandardized coefficients; p-values are reported in parentheses.

+p < 0.10. *p <0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

H3 predicts that identification asymmetry has a curvilinear (inverted U-shaped) relationship with exchange performance. As shown in Model 6 of Table 4, the regression coefficient of identification asymmetry is insignificant (b = −0.01, p > 0.10). However, the quadratic term of identification asymmetry is significant (b = −0.07, p < 0.01), indicating an inverted U-shaped relationship between identification asymmetry and exchange performance, with the highest point indicated by the regression results appearing at around -0.21. This value is approximately a balanced value of identification asymmetry in our observations (mean = −0.83 and s. d. = 1.35). Meanwhile, when identification asymmetry is below -0.21, exchange performance decreases by 0.6 with an additional unit of identification asymmetry, whereas when identification asymmetry is above -0.21, exchange performance decreases by 0.66 with an additional unit of identification asymmetry. The effect sizes are considerable compared with the mean level of exchange performance, 4.78. Thus, H3 is supported.

In addition, we found that the direct effect of within-dyad opportunism on exchange performance is negative and significant (b = −0.19, p < 0.01) while pro-relational opportunism does not show a significant effect on exchange performance (b = 0.02, p > 0.10). As such H4 is supported while H5 is rejected. We speculate that the rejected H5 may indicate that pro-relational opportunism involves complicated effects on exchange performance. On the one hand, it can improve performance for the relationship as a whole. On the other hand, it may also hurt the reputation of the relationship and brings more costs to the relationship. Taken together, the total effects may not be significantly beneficial to the exchange relationship.

A typical concern with the mediation test is that we may fail to find a significant zero-order effect of the predictor variable (X) on the outcome variable (Y) (e.g., we found no significant relationship between pro-relational opportunism and exchange performance and we have to reject Hypothesis H5). Such concern originates from the mediation test using Baron and Kenny's (1986) regression approach. However, recent advances in this area indicate that only the significant indirect effect is required to establish mediation, and researchers in psychology, marketing, and organizational behavior have begun accepting this strategy to remove the requirement of a significant zero-order effect of X on Y (e.g., Krishnan, Miller, & Judge, Reference Krishnan, Miller and Judge1997; Miller, Triana, Reutzel, & Certo, Reference Miller, Triana, Reutzel and Certo2007; Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, Reference Zhao, Lynch and Chen2010). Thus, we proceeded to establish mediation following Edwards and Lambert's (Reference Edwards and Lambert2007) procedures.

Given the curvilinear relationship between identification asymmetry and exchange performance, we used identification asymmetry as a moderator in the second stage of the model to estimate the mediation effects (Edwards & Lambert, Reference Edwards and Lambert2007: 19). We first conducted a regression for the identification asymmetry on two kinds of opportunism and then regressed exchange performance on opportunism, identification asymmetry, and its quadratic term. Next, we entered the coefficient gained from the two-step regression into the constrained nonlinear regression (CNLR) module to produce, via bootstrapping, 1,000 unstandardized coefficient estimates of each simple path, indirect effect, and total effect. For the significance test, we used the bias-corrected confidence intervals produced by the 1,000 bootstrap estimates. We did the same to compute the differences between each path and effect across levels of identification asymmetry. We used one standard deviation above or below the centered mean to indicate a high or low level of identification asymmetry. Table 5 presents the results.

Table 5. Tests on the mediation effect of identification asymmetry a

Notes: a Results are based on 1,000 bootstrapping sample; Number in the parentheses is standard errors.

+p < 0.10; *p < 0.05.

As shown in Table 5, for both the within-dyad and pro-relational opportunism paths, the second stage of the indirect effects (i.e., the quadratic term in OLS regression) is negative for a higher level of identification asymmetry but positive for a lower level of identification asymmetry, and the differences are significant (-0.20, p < 0.01), providing further support for H3. However, for the within-dyad opportunism path, the indirect effects (i.e., the mediating effect) and their difference are insignificant; thus, H6a is rejected. In contrast, for the pro-relational opportunism path, the indirect effect is negative and marginally significant for a higher level of identification asymmetry (-0.05, p < 0.10) and positive for a lower level of identification asymmetry (0.04, p < 0.05), and their difference is significant (0.09, p < 0.05). Thus, identification asymmetry mediates the effect of pro-relational asymmetry on exchange performance, which supports H6b.

We examine the moderating effects of distributive and interactive fairness by entering all of the interaction terms into the regression model. H7 predicts that the relationship between pro-relational opportunism and identification asymmetry becomes stronger when distributive fairness between the manufacturer and supplier is higher. As Table 4 shows, the interaction term between pro-relational opportunism and distributive fairness is positive and significant (b = 0.15, p < 0.01), which supports H7. To illustrate the effect sizes, we find that when distributive fairness is higher (one standard deviation above the mean), one unit increase in pro-relational opportunism leads to 0.75 increase in identification asymmetry. When distributive fairness is lower (one standard deviation below the mean), one unit increase in pro-relational opportunism leads to 0.32 increase in identification asymmetry.

H8a posits that the relationship between within-dyad opportunism and identification asymmetry becomes stronger when interactive fairness between the manufacturer and supplier is higher. As shown in Model 3 of Table 4, the interaction term between within-dyad opportunism and interactive fairness is insignificant (b = 0.01, p < 0.10), rejecting H8a. The null finding may be due to the fact that the effects of within-dyad opportunism on damaging relationship is so strong that interactive fairness cannot mitigate such negative effects.

H8b proposes that the relationship between pro-relational opportunism and identification asymmetry becomes weaker when interactive fairness between the manufacturer and supplier is higher. As shown in Table 4, the interaction term between pro-relational opportunism and interactive fairness is negative and significant (b = −0.14, p < 0.05), supporting H8b. To illustrate the effect sizes, we find that when interactive fairness is higher (one standard deviation above the mean), one unit increase in pro-relational opportunism leads to 0.34 increase in identification asymmetry. When interactive fairness is lower (one standard deviation below the mean), one unit increase in pro-relational opportunism leads to 0.74 increase in identification asymmetry.

DISCUSSION

We propose a concept of identification asymmetry to examine the relationships between different kinds of opportunism and exchange performance. Figure 2 summarize the main effects and illustrate the results shown in Table 4.

Figure 2. Illustration of the effects of identification asymmetry

As shown in Figure 2, identification asymmetry displays an inverted U-shaped relationship with exchange performance. Moreover, we find that within-dyad opportunism is negatively related and pro-relational opportunism is positively related to identification asymmetry. Theoretically we propose that as within-dyad opportunism increases, identification asymmetry moves toward Type II asymmetry, while as pro-relational opportunism increases, identification asymmetry moves toward Type I asymmetry. Both types of asymmetry harm exchange performance. The empirical evidence of pro-relational opportunism is consistent with our theory. It demonstrates that pro-relational opportunism negatively affects exchange performance via identification asymmetry. However, within-dyad opportunism has only direct and negative effect on exchange performance. Moreover, our findings also reveal that the effect of pro-relational opportunism is contingent on distributive and interactive fairness perceptions. Distributive fairness strengthens the effect of pro-relational opportunism on identification asymmetry while interactive fairness weakens such relationship. Taken together, this study makes several contributions.

Theoretical Contributions

We contribute to the transaction cost economics and ethical-decision-making literature by proposing and differentiating between the roles of within-dyad and pro-relational opportunism in business exchange. Although the two streams treat the concept of opportunism as an important focus, they have not communicated with each other to generate more insights. The opportunism research has done little to theoretically and empirically examine the possibility that firms may engage in opportunism toward society for mutual gains. Our study takes an initial step toward integrating the two streams and provides empirical evidence that within-dyad and pro-relational opportunism are related but distinct constructs that have different outcomes on relational identification in IORs. Much more research is needed to further identify the inherent differences between the two types of opportunism, particularly the complexities of pro-relational opportunism.

Moreover, we demonstrate that an identification asymmetry framework is helpful for understanding exchange performance in IORs. To our best knowledge, this study is among the first to unambiguously examine the relational identification at both the interorganizational and interpersonal levels. In so doing, we contribute by responding to calls for the examination of the more important questions of between-level dynamics (Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Harrison and Corley2008; Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011; Homburg et al., Reference Homburg, Wieseke and Hoyer2009). We demonstrate that identity cascade, in which higher-order identification directly informs and legitimates lower-order identification, is impeded in IORs. Instead, an identification differentiation occurs. Our findings also lend empirical support to the argument that formal and informal relationships in organizations tend to be characterized by different relational dynamics (Gulati et al., Reference Gulati, Lavie and Madhavan2011; Poppo & Zhou, Reference Poppo and Zhou2014).

Furthermore, we find that both Type I and Type II asymmetry are triggered by different opportunistic behaviors and mediate their effects on exchange performance. We thus significantly contribute by revealing the underlying mechanisms of Type I asymmetry through which pro-relational opportunism negatively affects exchange performance. Responding to the question of ‘the banality of evil’ (Arendt, Reference Arendt1963/2006), our study shows that boundary spanners are still conscious of their identity but respond to the interorganizational ‘evil’ by disidentification with the counterpart managers. Therefore, the performance outcomes of different kinds of opportunism may be similar, but the processes can be quite different. We call for future research to further examine the nuanced effects of different kinds of opportunism on relational interactions.

In addition, it seems that a balance of identification at the interorganizational and interpersonal levels would be more beneficial for business exchange. However, balance does not mean equal to each other (Li, Reference Li2007). For example, in our case, the optimal identification asymmetry is that interpersonal identification is slightly stronger than interorganizational identification. As Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Lu, Li and Liu2015) discussed, interorganizational and interpersonal identification may be simultaneously complementary and substitutive, and ‘the specific balances of the two elements are asymmetrical’ (317) in a spatial and temporal pattern. Thus, when we have already achieved strong degrees in both interorganizational and interpersonal identification, we may still be able to reach a high level of performance only if the increase in either interorganizational or interpersonal identification does not exceed certain degree of identification asymmetry. However, the focus of this study is not only the level of the performance but also the changing patterns as identification asymmetry changes. This finding extends the previous research that focuses only on interorganizational identification (e.g., Dyer & Nobeoka, Reference Dyer and Nobeoka2000). Thus, identification asymmetry may provide an important avenue for examining the between-level relational dynamics in IORs and highlights the need for greater attention to the social identity approach in business exchange research.

Regarding the moderating effects of distributive and interactive fairness, our findings directly address the paucity of research regarding the roles of fairness perceptions in IORs (e.g., Luo, Reference Luo2007; Poppo & Zhou, Reference Poppo and Zhou2014). We show that distributive fairness enhances the relationship between pro-relational opportunism and identification asymmetry and that interactive fairness weakens the relationship. Thus, we empirically confirm that distributive fairness aggravates the Machiavellian reasoning of firms when their partners engage in unethical behavior, lending support to the previous theoretical speculations (e.g., Brass et al., Reference Brass, Butterfield and Skaggs1998; Gino et al., Reference Gino, Moore and Bazerman2008; Moore & Gino, Reference Moore and Gino2013). From this perspective, our findings also contribute to the fairness literature (Luo, Reference Luo2007). We explore the dark side of distributive fairness and suggest that constructs that are often considered constructive may have unexpected negative effects. Further analysis of exchange performance shows that distributive fairness actually damages rather than helps firms seeking to benefit from unethical business exchanges. In addition, the different moderating effects of distributive and interactive fairness indicate that the effects of different components of fairness may differ in business exchange. Poppo and Zhou (Reference Poppo and Zhou2014) also find that distributive and procedural fairness have different roles in contractual design. We call for future research to examine the roles of fairness.

Managerial Implications

Our study reveals the dynamics of the identification process across levels in IORs. Managers should be aware of the need to balance relational identification at the interorganizational and interpersonal levels. Neither too much interorganizational identification nor too much interpersonal identification is good for exchange performance. How to balance relational identification across levels may be a strategic capability for firms to effectively leverage interorganizational relationships to gain competitive advantages. Managers should form shared goals and build mutually agreeable routines for knowledge sharing to increase interorganizational identification. They should also nurture an environment favorable to the development of relational bonds for boundary spanners to facilitate the development of interpersonal identification. However, in the transition economies like China where business rely more on personal ties, managers must pay special attention to the tendency of over-informality (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lu, Li and Liu2015), resulting in Type II asymmetry. Using the differentiation and integration techniques (e.g., Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011), managers could find an optimal balance between interorganizational and interpersonal identification to improve exchange performance.

Managers should also understand the differential effects of opportunistic behavior on relational identification at different levels. Interorganizational identification tends to be more sensitive to within-dyad opportunism than does interpersonal identification. More importantly, managers should be wary of the dangers of their partners engaging in unethical behavior in the name of the partnership. In the transition economies where law and other regulatory institutions are under-developed, such dangers in the tendency of Machiavellian reasoning is much higher. According to our research, this kind of seemingly beneficial complicity in the short term (Pinto, Leana, & Pil, 2008) actually increases identification asymmetry across levels, which negatively affects exchange performance.

Understanding the different triggers and dynamics of identification at different levels can help managers design optimal mechanisms to manage and leverage their IORs and thereby achieve competitive advantages. Our findings thus remind managers that they should design systems to proactively monitor their partners’ opportunistic behavior, especially pro-relational opportunism. They should evaluate these kinds of opportunism in all of their business exchanges. Moreover, interactive fairness can mitigate the relationship between pro-relational opportunism and identification asymmetry. Thus, when pro-relational opportunism may exist, managers should deliberately create an open, respectful, timely, and constructive environment for boundary spanners to reduce the potential negative effects of pro-relational opportunism.

Limitations and Future Research Implications

Although our study provides a number of insights, it has several limitations that suggest directions for further research. First, we assume that boundary spanners’ identification with their respective firms is constant. However, if boundary spanners strongly identify with their firms, they may view the interests of the firms as their own interests and agree with what the firms do (e.g., opportunism toward society or the partner firm). If so, the predictions in our theory may change. We therefore call for future research to incorporate person–firm identification into the framework to further examine the dynamics of relational identification across levels. Second, we argue that identification asymmetry affects exchange performance through different mechanisms at different levels. We did not directly measure these mechanisms; thus, future research can provide more insights by empirically examining these mechanisms. Third, although we spent a great deal of effort to collect data from both sides, this study remains cross-sectional by nature. Thus, we may suffer from causality problems. For example, identification asymmetry may encourage firms to conduct within-dyad or pro-relational opportunism. Case analyses and longitudinal studies may help attenuate the causality concern. Fourth, we examine only the boundary condition of our theory from the fairness perceptions in IORs. Our study is also limited to the single national context of China which has higher level of in-group favoritism. However, the effects of opportunism on identification asymmetry may be contingent on cultural (Carter, Reference Carter2000), institutional (Pinto et al., 2008), and personal (Moore & Gino, Reference Moore and Gino2013) factors. Future research examining the generalizability of this study is critically warranted. Finally, subjective surveys on opportunism are susceptible to the socially desirable response bias (Steenkamp, de Jong, & Baumgartner, Reference Steenkamp, de Jong and Baumgartner2010). Future research should use methods such as the item randomized response technique (de Jong, Pieters, & Fox, Reference De Jong, Pieters and Fox2010) to reduce bias and further examine the relationships proposed in our study.

APPENDIX I

Measurement Items and Validity Assessment a