INTRODUCTION

Corporate philanthropy plays a vital role in addressing some social problems, especially in emerging economies. For example, it accounted for 61.89% of the total social giving in China in 2018.[Footnote 1] As a type of discretionary corporate social responsibility, corporate philanthropy is ‘guided by businesses’ desire to engage in social roles not mandated or required by law and not expected of businesses in an ethical sense’ (Carroll, Reference Carroll1999: 284). Although it is not mandatory, it is, nevertheless, subject to an increased level of managerial discretion. Corporate philanthropy often generates firms with long-term social assets, such as improved reputations (Brammer & Millington, Reference Brammer and Millington2005), legitimacy (Zhang, Xu, Chen, & Jing, Reference Zhang, Xu, Chen and Jing2020), and innovative efforts and loyalty from employees (Flammer & Kacperczyk, Reference Flammer and Kacperczyk2019). However, it can prevent executives from maximizing firms’ profits, induce unnecessary costs, and impede firms from competing (Friedman, Reference Friedman1970). Therefore, different executives may have varying views on both corporate philanthropy and its impacts on the firm.

Studies that examined the antecedents of corporate philanthropy focused on the characteristics of individual leaders, mainly the chief executive officer (CEO) (Marquis & Lee, Reference Marquis and Lee2013), or on the demographic compositions of the boards or top management teams, such as board size, gender composition, and network types (e.g., Jia & Coffey, Reference Jia and Coffey1992; Li, Song, & Wu, Reference Li, Song and Wu2015). However, the literature predominantly neglects the chief financial officer (CFO). Owing to the increasing need for internal control and monitoring in recent years, the importance of the CFO in top management teams has grown significantly worldwide, even in emerging economies such as China (Deng, Qiu, & Deng, Reference Deng, Qiu and Deng2003). Thus, examining the CFO and their role differences from and interactions with the CEO may yield valuable insights on the determinants of firms’ decision making on philanthropic contributions.

In this study, we attempt to address this gap in the literature by considering the two most important figures on the top management team (i.e., the CEO and the CFO) and examining their differential and interactive impact on corporate philanthropy. By integrating both role theory (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986; Turner, Reference Turner1978) and social identity theory (Hogg, Terry, & White, Reference Hogg, Terry and White1995; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel and Tajfel1978; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1985), we develop our theoretical model that highlights the different attitudes of CEOs and CFOs about corporate philanthropy owing to their different role expectations and that organizational identification strengthens their motivations to express their attitudes.

Specifically, role theory (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986) explains how and why roles and role expectations can influence individual behaviors. The CEO and the CFO are expected to play different functional roles within companies. The CEO is responsible for every aspect of the company, while the CFO is required to ‘not only monitor company behavior but also promote development’ (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Qiu and Deng2003: 12). They are associated with different role expectations, which are beliefs about what is required for successful role performance (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986). We adopt role theory to propose that executives with various functional roles may interpret firm investment decisions differently (e.g., corporate philanthropy). The CEO, who is responsible for the firm's long-term prospects and functions as a bridge between the firm and external stakeholders (i.e., both core and peripheral stakeholders) (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1973), would view corporate philanthropy positively because the roles the CEO plays would enable him/her to discern the results of corporate philanthropy: improved firm reputation, legitimacy, and employee loyalty. Conversely, the CFO, who is responsible for overseeing firm investment decisions and maximizing financial returns from firm resource allocation (Habib & Hossain, Reference Habib and Hossain2013), would view corporate philanthropy negatively because his/her roles are focused on the potential immediate financial returns from investment.

According to social identity theory, identification with a group or an organization influences the behavior of its members by depersonalizing their self-concept (Ashforth & Johnson, Reference Ashforth, Johnson, Hogg and Terry2001; Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, Terry and White1995). Executives who identify highly with their firms would act on what they believe to be in the firm's best interests (Boivie, Lange, McDonald, & Westphal, Reference Boivie, Lange, McDonald and Westphal2011). Therefore, we focus on organizational identification, which refers to the perception of oneness with or belongingness to an organization (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989). We propose that as the CEO and the CFO have different attitudes about corporate philanthropy and its organizational impact, organizational identification of these would differentially influence corporate philanthropy. Therefore, CEO organizational identification is positively associated with corporate philanthropy, while CFO organizational identification is the opposite.

In addition, attitudes of top executives are the outcomes of interdependence and interactions with other executives (Chattopadhyay, Glick, Miller, & Huber, Reference Chattopadhyay, Glick, Miller and Huber1999; Hambrick & Cannella, Reference Hambrick and Cannella2004). CFOs with strong organizational identification are more willing to fulfill their role expectations by providing suggestions, persuading the CEO, and influencing the CEO's decisions on corporate philanthropic donations and activities. Therefore, CFO organizational identification is expected to undermine the relationship between CFO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy. As individuals’ role behaviors and interactions are shaped by the relational and structural features of their social units (Biddle, Reference Biddle2013; Katz & Kahn, Reference Katz and Kahn1978), we further propose that the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification hinges on CEO–CFO gender similarity and CFO ownership, which indicate the relational and structural features between them.

We found empirical support for our arguments from a sample of CEOs and CFOs from 880 publicly traded firms in China. Our study has two important contributions. First, it contributes to the literature on corporate social responsibility, particularly corporate philanthropy research, by focusing on the differential impacts of CEO and CFO organizational identification and their interaction effects on corporate philanthropy. Existing research has mainly focused on the demographic characteristics of CEOs or average top management teams (e.g., Marquis & Lee, Reference Marquis and Lee2013). However, recently, studies began to examine the deep-level psychological factors of executives (e.g., Tang, Mack, & Chen, Reference Tang, Mack and Chen2018; Zhu & Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen2015). In particular, our study advances research on executive roles in corporate social responsibility by highlighting the importance of organizational identification and interaction between the CEO and CFO.

Second, our study can also advance strategic leadership research. Existing studies have investigated the influence of the CEO or the entire top management team on strategic decisions of firms. Recently, scholars are beginning to explore the social interactions among different executives (e.g., Shi, Zhang, & Hoskisson, Reference Shi, Zhang and Hoskisson2019). Studying the interactions among top executives can inform the processes of firm strategic decision making (Westphal & Zajac, Reference Westphal and Zajac2013). Our findings on the interaction effect between the CEO and CFO and the moderating effect of CEO–CFO gender similarity and CFO ownership provide us with in-depth understanding of when and how executives interact to influence firm decisions, thus providing new insight into strategic leadership research.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Corporate Philanthropy Research

Corporate philanthropy involves firms’ donations of cash or other assets to social and charitable causes (Cuypers, Koh, & Wang, Reference Cuypers, Koh and Wang2015; Galaskiewicz, Reference Galaskiewicz1997; Godfrey, Reference Godfrey2005). Although corporate philanthropy has received substantial attention from research and practice (e.g., Godfrey, Reference Godfrey2005; Marquis & Lee, Reference Marquis and Lee2013; Wang, Choi, & Li, Reference Wang, Choi and Li2008), its impact on firms is unclear. Some argue that CEOs engage in corporate philanthropy to enhance firm reputation and create ‘moral capital’ for firms (Brammer & Millington, Reference Brammer and Millington2005; Godfrey, Reference Godfrey2005), which is in the long-term interests of shareholders. However, others argue that corporate philanthropy is a waste of corporate resources (Friedman, Reference Friedman1970) and is mostly used by top executives to improve their personal reputation and career prospects (Galaskiewicz, Reference Galaskiewicz1997; Haley, Reference Haley1991).

Corporate philanthropic decisions can be influenced by the characteristics of a firm or its executives (Brammer & Millington, Reference Brammer and Millington2005; Li et al., Reference Li, Song and Wu2015). Prior studies that used strategic or institutional perspectives suggest that firms use corporate philanthropy as a nonmarket strategy to obtain legitimacy from key stakeholders (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Song and Wu2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xu, Chen and Jing2020). Therefore, firm characteristics such as political connections and state ownership are positively associated with corporate philanthropic contributions (Li et al., Reference Li, Song and Wu2015). In addition, upper echelons theory (Carpenter, Geletkanycz, & Sanders, Reference Carpenter, Geletkanycz and Sanders2004; Hambrick & Mason, Reference Hambrick and Mason1984) suggests that managerial cognitions, values, and perceptions can influence philanthropic giving. Given the difficulty of measuring psychological characteristics, most studies have used demographic characteristics as proxies for underlying psychological traits and investigated the relationship between these proxies and corporate philanthropy. For instance, the findings of Wang and Coffey (Reference Wang and Coffey1992) and Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Geletkanycz and Sanders2004) indicate that a higher proportion of female directors is positively associated with corporate philanthropy. In addition, Marquis and Lee (Reference Marquis and Lee2013) show that the characteristics of senior executives and directors (e.g., tenure, gender, interlock network) are crucial determinants of corporate philanthropy.

Nevertheless, only a few studies (e.g., Fu, Tang, & Chen, 2020; Tang, Qian, Chen, & Shen, Reference Tang, Qian, Chen and Shen2015) have investigated how the deep-level psychological characteristics of executives influence philanthropic donations, or corporate social responsibility in general. As different people have different attitudes about corporate philanthropy, do different executives and their characteristics affect corporate philanthropy differently? To answer this question, this study examines how the CEO and CFO's roles and their organizational identification influence corporate philanthropy. Our theoretical model integrates both role theory and social identity theory. Before presenting our theoretical model, we first review the two theories below.

Role Theory and Role Expectations for CEO and CFO

Role theory describes the generalized behavioral patterns, or roles, which apply to actors attempting to accomplish specific functions within a system. Roles are the shared, normative expectations directed by others toward a social actor who occupies a certain position within a social system (Stein, Reference Stein1982; Turner, Reference Turner1978). Crucial to role theory is the concept of roles as social positions that influence the expectations for normative behaviors (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986). Different from the statements in bureaucracy theory (Gerth & Wright Mills, Reference Gerth and Wright Mills1946), which focus on the power of positions and the selection of the best individual for each position in the organization, role theory focuses on role expectations and the resulting behavior (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986).

Role expectations refer to the expectations for what constitutes appropriate behavior for those holding a given role (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986; Linton, Reference Linton1936; Shaw & Costanzo, Reference Shaw and Costanzo1982). Role expectations are often defined by others within the organization (Ashforth, Kreiner, & Fugate, Reference Ashforth, Kreiner and Fugate2000). Thus, the behavioral characteristics of roles are directly linked to interactions (Stryker & Statham, Reference Stryker, Statham, Lindzey and Aronson1985). These interactions shape how individuals cognitively perceive role expectations, which in turn affects their behaviors (Biddle, Reference Biddle1979, Reference Biddle1986). This is particularly true for top executives as it is impossible for them to have expertise in all the functional areas under their purview. As difficulties are inherent in undertaking activities outside an individual's direct role within an organization, individuals are unlikely to engage in such activities unless they believe it is part of their personal role responsibilities (Katz & Kahn, Reference Katz and Kahn1978).

The CEO position emerged with the advent of the modern corporation, which has a managerial structure that requires individual managers handling different business units and functions with the CEO overseeing them as a high-level panoramic manager (Parker, Reference Parker2020). In contrast, the role of CFO emerged much later. Before the 1960s, the term CFO did not exist, with accountant being the equivalent term (Granlund & Lukka, Reference Granlund and Lukka1998; Sharma & Jones, Reference Sharma and Jones2010; Zorn, Reference Zorn2004), whose responsibility was ‘to prepare the books and report back to higher level management on the overall financial risk and performance of the enterprise’ (Sharma & Jones, Reference Sharma and Jones2010:1). With the financialization of economy, the term CFO was coined due to legislative changes in Western countries (Zorn, Reference Zorn2004).

The roles of the CEO and the CFO have evolved over time. Globalization and innovative technologies in the past decades have changed the roles of the CEO. The CEO is now expected to have more open-minded views that align with the interests of stakeholders and shareholders alike (Parker, Reference Parker2020). The roles of CFOs are also evolving, but the change varies across different countries. In Western countries, CFOs are expected to go beyond the traditional role of balancing the books to a broader role, which involves managing risks, preserving liquidity, maintaining shareholders’ confidence, and being a key value driver in the business.[Footnote 2] In contrast, the roles of CFOs in emerging economies such as China are still more traditional and narrowly focused on accounting or investments.[Footnote 3]

As the CEO and CFO are expected to play different roles in the organizations, they have different interpretations and preferences for firm decisions. The CFO often has a narrow mindset, which makes the CFO's attitude different from that of the CEO. According to Ximing Zheng, CEO of Kailongrui Project Investment Consulting Company, ‘[the] CFO often says, “this can't be done, and that can't be done”; in contrast, the CEO's job is to get things done’.[Footnote 4] Moreover, their views could be complementary. In a round-table discussion on the value of the modern CFO, a CEO stated, ‘If a CEO is very strategic, then the CFO has to play that complementary operational role. If the CEO is more of a big picture type who likes to seek consensus, but sometimes at the expense of reaching a decision, then the CFO will do the CEO a favor by bringing an element of decisiveness to the team’.[Footnote 5]

Social Identity Theory and Organizational Identification

Social identity theory describes how individuals distinguish themselves from the identity of the categories or groups they belong to (Ashforth & Johnson, Reference Ashforth, Johnson, Hogg and Terry2001; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel and Tajfel1978; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1985). Specifically, social identity is ‘that part of an individual's self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership to a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership’ (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel and Tajfel1978: 63). The members of a social group share the basic traits of the group, which depersonalize their self-concepts (Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, Terry and White1995) through a categorization process, ‘where I becomes we’ (Brewer, Reference Brewer1991: 476). The degree wherein an individual's behavior is shaped by a particular group identity depends on how strongly he or she identifies with the group (Ashforth & Johnson, Reference Ashforth, Johnson, Hogg and Terry2001).

Organizations are important social domains that provide their members with a significant social identity (Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2000). When social identity theory is applied to organizational settings, organizational identification reflects how a member defines his/her relationship with the organization (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989). Two different perspectives over the outcomes of organizational identification exist. A general perspective, focusing on the positive side of organizational identification, proposes that when members have strong organizational identification, they are more likely to act to benefit the organization as doing so would enhance their self-concept (Boivie et al., Reference Boivie, Lange, McDonald and Westphal2011). In contrast, when members have low organizational identification, they are more likely to act for their own interests even if it hurts the organization. This is because their self-concept is disconnected from the attributes of the organization.

Nevertheless, some studies focus on the detrimental outcomes of organizational identification (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Ryan, Postmes, Spears, Jetten and Webley2006). High organizational identification may lead individuals to lose their distinctiveness (Dukerich, Kramer, & Parks, Reference Dukerich, Kramer, Parks, Whetten and Godfrey1998), reflected in their conformity with organizational customs and a loss of objectivity (Conroy, Henle, Shore, & Stelman, Reference Conroy, Henle, Shore and Stelman2017). These would make individuals vulnerable to problematic behaviors or outcomes, such as behaviors that may benefit the organization in the short run but may hurt it in the long run (Umphress, Bingham, & Mitchell, Reference Umphress, Bingham and Mitchell2010).

While existing identification research has mainly focused on the organizational identification of the employees (He & Brown, Reference He and Brown2013; Lee, Park, & Koo, Reference Lee, Park and Koo2015), recent strategic leadership research has begun exploring the organizational identification of top executives and the associated implications (e.g., Abernethy, Bouwens, & Kroos, Reference Abernethy, Bouwens and Kroos2017; Boivie et al., Reference Boivie, Lange, McDonald and Westphal2011). Because top executives are essential in firm decisions (Finkelstein, Hambrick, & Cannella, Reference Finkelstein, Hambrick and Cannella2009), their organizational identification can exert profound influence on firm outcomes (Abernethy et al., Reference Abernethy, Bouwens and Kroos2017). However, extant research implicitly assumes that the influence of organizational identification on organizational outcomes is identical for all executives. This view neglects the fact that top executives may have different attitudes toward firm strategic behaviors owing to their distinct role expectations (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986; Linton, Reference Linton1936). As such, the effect of organizational identification on firm behavior such as corporate philanthropy may vary depending on the different roles of the executives.

Differential Impact of CEO and CFO Organizational Identification on Corporate Philanthropy

Based on both role theory (Biddle, Reference Biddle1979, Reference Biddle1986) and social identity theory (Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, Terry and White1995; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel and Tajfel1978; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1985), we propose that executives in different roles often have different attitudes about any strategic behavior of the firm (e.g., corporate philanthropy) due to their distinct role expectations, and a high level of organizational identification of them would motivate them to act based on their attitudes. On one hand, executives’ understanding of ‘the best of the organization’ (i.e., where their efforts toward) should be shaped by their roles (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986). Therefore, a CEO and a CFO may hold different views about the value and costs of a specific strategic behavior. Despite the different views, they may not express and practice their views until they are highly motivated to. However, high organizational identification means members align themselves with the identity of the organization they belong to (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel and Tajfel1978). Executives with high organizational identification often act in their organization's best interests (Boivie et al., Reference Boivie, Lange, McDonald and Westphal2011). As a result of the integrative influence of role expectations and identification with the organization, the organizational identification of both the CEO and the CFO should have differential impacts on the strategic behavior, such as corporate philanthropy.

Specifically, each social role is a set of rights, duties, expectations, norms, and behaviors that an individual must face and fulfill (e.g., Eagly & Steffen, Reference Eagly and Steffen1984; Koenig & Eagly, Reference Koenig and Eagly2014). The CEO is the face of the firm and bridges the firm and external parties (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1973). Thus, CEO can recognize the demands of various stakeholders, including peripheral stakeholders. Corporate philanthropy often plays a significant role in stakeholder management, resulting in stakeholders holding the more favorable impression of the firm. In the 2010 Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy Board of Boards CEO Conference, 62% of the surveyed CEOs agreed that taking a proactive approach to solving relevant social issues is necessary as they are in a unique position to make a difference (McKinsey & Company, 2017).

In addition, the CEO remains responsible for creating a firm's sustainable competitive advantages. Thus, the CEO would often adopt a comprehensive view and focus on not only initiatives that bring short-term performance benefits but also those that provide long-term benefits such as corporate philanthropy (e.g., improved reputation, legitimacy, and employee loyalty). Although corporate philanthropy does not directly influence firm performance, it can bring long-term social benefits for firms such as improved reputation (Brammer & Millington, Reference Brammer and Millington2005), legitimacy (Muller & Kraussl, Reference Muller and Kraussl2011; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xu, Chen and Jing2020), and innovative efforts and loyalty from employees (Flammer & Kacperczyk, Reference Flammer and Kacperczyk2019). Aware of the value of the benefits that corporate philanthropy can bring for the firm (Haley, Reference Haley1991; Muller & Kraussl, Reference Muller and Kraussl2011), the CEO would view corporate philanthropy positively.

In contrast, the CFO is mainly responsible for protecting firm assets and maximizing financial returns from firm resource allocation (Chava & Purnanandam, Reference Chava and Purnanandam2010; Habib & Hossain, Reference Habib and Hossain2013). Thus, when deciding whether to engage in corporate philanthropy, the CFO's main consideration is the potential financial returns and costs of corporate philanthropy rather than how much firm reputation, legitimacy, or employee loyalty it may bring. Returns from philanthropy are difficult to quantify and seldom manifest in the short term. The resources allocated to philanthropy cannot be allocated for other purposes, thus generating high opportunity costs. Moreover, corporate philanthropy is associated with high cost, which may be at the consumer's expense, leading to the loss of price-sensitive customers (Cui, Liang, & Lu, Reference Cui, Liang and Lu2014).

Furthermore, the CFO is tasked with overseeing firm compliance with legal regulations and managing financial risks (Tulimieri & Banai, Reference Tulimieri and Banai2010). Consequently, their attention would be devoted to managing relationships with core stakeholders such as employees and investors. Corporate philanthropy giving is intended to create goodwill with peripheral stakeholders, particularly local communities (Brown, Helland, & Smith, Reference Brown and Caylor2006). Thus, the CFO may not see much value in corporate philanthropy.

The above discussion suggests that both the CEO and CFO have different interpretations on the value, benefits, and costs of corporate philanthropy and because of the distinct roles they are expected to play. Meanwhile, the top executives with strong organizational identification are more likely to act in the organization's best interests (Boivie et al., Reference Boivie, Lange, McDonald and Westphal2011). This is because the self-esteem of individuals with strong organizational identification overlaps with the well-being of the organizations to which they belong; executives who identify strongly with their organizations would perceive threats to the latter's well-being as threats to their self-esteem (Boivie et al., Reference Boivie, Lange, McDonald and Westphal2011). Humans are naturally driven to mitigate threats to their self-esteem. As such, when their self-esteem is threatened, CEOs and CFOs with strong organizational identification would act to improve the firm's well-being. Because the CEO tends to perceive philanthropy positively, we expect CEO organizational identification to be positively related to corporate philanthropy. In contrast, as the CFO tends to view philanthropy negatively, we expect CFO organizational identification to be negatively associated with corporate philanthropy.

Hypothesis 1: CEO organizational identification is positively associated with corporate philanthropy.

Hypothesis 2: CFO organizational identification is negatively associated with corporate philanthropy.

Interactions between the CEO and the CFO and the Constraints on Their Interactions

Firm investment decisions are the outcomes of interactions among the top executives (Hambrick & Mason, Reference Hambrick and Mason1984). The roles of the CEO and other executives are separate but complementary (Hambrick & Cannella, Reference Hambrick and Cannella2004). Thus, there is horizontal interdependence between the CEO and CFO, defined as ‘the degree to which roles are arranged such that actions and effectiveness of peers affect each other’ (Hambrick, Humphrey, & Gupta, Reference Hambrick, Humphrey and Gupta2015: 451). The CFO may play his/her role by providing suggestions to the CEO. Therefore, we examine how the CFO interacts with the CEO to influence corporate philanthropy. First, we propose that the CFO who highly identifies with the organization would make efforts to persuade the CEO to accept his/her attitudes about the strategic behavior, thereby weakening the effect of CEO organizational identification.

Moreover, role theory implies that individuals also behave according to the relational and structural features of their organization (Biddle, Reference Biddle2013; Katz & Kahn, Reference Katz and Kahn1978). Individual roles are collectively determined and relationally negotiated (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986; Raes, Heijltjes, Glunk, & Roe, Reference Raes, Heijltjes, Glunk and Roe2011) and are simultaneously constrained by their structural power (Cannella & Holcomb, Reference Cannella, Holcomb, Dansereau and Yammarino2005). Therefore, we further propose that the interactions of the CEO and CFO also depend on their relational and structural features. By examining CEO–CFO gender similarity and CFO power, which indicate the CFO's competitive relationship with the CEO (Gupta, Jenkins, & Beehr, Reference Gupta, Jenkins and Beehr1983) and CFO's structural power (Cannella & Shen, Reference Cannella and Shen2001), respectively, we propose that these two factors can affect the extent to which the CEO accepts the CFO's suggestion.

Interactions between the CEO and the CFO

The CEO and other executives have separate yet complementary functional roles in the top management team (Hambrick & Cannella, Reference Hambrick and Cannella2004). Although the CEO generally has the final say on investment decisions, other top executives can influence these decisions by providing their insights and opinions and by playing devil's advocate (Schweiger, Sandberg, & Rechner, Reference Schweiger, Sandberg and Rechner1989). Consistent with such arguments, Chattopadhyay et al. (Reference Chattopadhyay, Glick, Miller and Huber1999) found that top executives’ beliefs are subject to each other's influence and are socially reproduced through interactions with each other.

While the CEO is the primary decision-maker of the firm and often has more structural power than the CFO, the latter remains an important partner of and interacts closely with the former (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhang and Hoskisson2019). Although the CEO and the CFO have distinct interpretations of investment decisions because of different role expectations, they can influence each other's decisions through communications and solving problems together (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Glick, Miller and Huber1999). Particularly, the CFO often ‘change(s) or further develop(s) the strategic plans through challenging and questioning in the process of strategy formation’ (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Qiu and Deng2003: 12). Therefore, we focus on the interaction between the CEO and the CFO by examining how CFO organizational identification moderates the relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy.

A CFO with strong organizational identification is highly motivated to act in the best interests of the firms and fulfill his/her roles. As the CFO tends to view corporate philanthropy as a waste of the firm's financial resources, he/she would attempt to influence the CEO against making a high level of corporate philanthropic investment. The CFO could directly communicate his or her concerns about philanthropic donations to the CEO (Falcione, Sussman, & Herden, Reference Falcione, Sussman, Herden and Jablin1987). The CFO may also express his or her concerns during the process of sense-making with the CEO and other non-CEO top executives (Gioia, Reference Gioia and Thomas1996; Louis, Reference Louis1980). The CEO may reduce philanthropic donations when paired with a CFO with strong organizational identification as the former's beliefs are subject to the latter's social influence.

When the CFO has weak organizational identification, he/she may be less likely to act in the firm's best interests and fulfill his/her roles. As mentioned earlier, the CEO's beliefs are influenced by other top executives including the CFO. The CFO is expected to play the role of internal control in decision making (Hoitash, Hoitash, & Johnstone, Reference Hoitash, Hoitash and Johnstone2012) and guide the CEO toward carefully evaluating the costs and benefits of investment decisions. However, a CFO with weak identification may be less inclined to argue against the CEO's beliefs and decisions as doing so may potentially harm his/her relationships with the CEO who, as the supervisor, can affect the CFO's compensation level and career opportunities (Feng, Ge, Luo, & Shevlin, Reference Feng, Ge, Luo and Shevlin2011). In summary, the positive influence of CEO organizational identification on corporate philanthropy is stronger when the CEO is paired with a CFO with weak organizational identification.

Hypothesis 3: CFO organizational identification weakens the positive relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy.

Gender similarity as the constraint on CEO and CFO interactions

The interactions between the CEO and CFO may depend on their relationship. On one hand, as a supervisor (CEO) and subordinate (CFO) dyad, the CFO is supposed to support the CEO. On the other hand, the CFO could become a successor to the CEO. Therefore, competition and cooperation may coexist between them (Mobbs & Shawn, Reference Mobbs2013; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhang and Hoskisson2019). We focus on CEO–CFO gender similarity, which marks the competition-cooperation relationship (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Jenkins and Beehr1983).

We propose that when paired with a different-gender CFO, the CEO is more likely to take the CFO's suggestion. First, different-gender dyads are more likely to trust each other than same-gender dyads. When the CEO and the CFO are of the same gender, the CEO is more likely to perceive the latter as a competitor. As indicated by previous studies (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Jenkins and Beehr1983; Mobbs, & Shawn, Reference Mobbs2013), same-gender competition can result in less trust in the dyad of male supervisor and male subordinate and the dyad of female supervisor and female subordinate. Second, a different-gender CFO often has different perspectives from those of the CEO, enabling the former to offer perspectives complementary to those of the latter. Therefore, the CEO may find the CFO's suggestions valuable and implement them.

Based on the arguments above, we propose that the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification would be weakened by CEO–CFO gender similarity.

Hypothesis 4: The moderating effect of CFO organizational identification on the relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy becomes weaker when the CEO and the CFO are of the same gender than when they are of different genders.

CFO ownership as the constraint on the interaction

Ownership is an important source of power (Cannella & Shen, Reference Cannella and Shen2001; Combs, Jr., Perryman, & Donahue, Reference Combs, Ketchen, Perryman and Donahue2010). It determines the CFO's position in the principal-agent relationship and indicates the possibility of the CFO closely interacting with the board and powerful shareholders (Cannella & Shen, Reference Cannella and Shen2001). Previous studies indicate that executives with high levels of ownership power are more likely to hold on to their positions despite their performance than those with low levels of ownership or none at all (Boeker, Reference Boeker1992; Ocasio, Reference Ocasio1994). Therefore, ownership provides the CFO with legitimate authority to influence the behavior of others, including the CEO.

Ownership is also a salient indicator of the CFO's incentive, which helps the CEO interpret the motives of the CFO. Ownership can bind the CFO with shareholder wealth, and this is a strong performance incentive (Fama & Jensen, Reference Fama and Jensen1983). When the CFO expresses attitudes different from those of the CEO, the CEO may interpret such attitudes as goodwill if the CFO has a high level of ownership. In contrast, if the CFO has a low level of ownership or none at all, the CEO may question the motives of the CFO, thus making the former less likely to take the suggestion of the latter. Based on the arguments above, we propose that the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification would be strengthened by CFO ownership.

Hypothesis 5: The moderating effect of CFO organizational identification on the relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy becomes stronger when the CFO has a high level of ownership compared to that with a low level of ownership.

METHODS

Interviews on CEOs and CFOs

To obtain greater insight on CEOs and CFOs’ understanding of their roles and their attitudes toward corporate philanthropy, before collecting data for empirical analyses, we randomly chose and interviewed 4 CEOs and 4 CFOs from listed firms in China. We mainly asked these executives some open questions related to their understanding of CEOs/CFOs’ roles and their own views about corporate philanthropy.

In general, the CEOs we interviewed have stated that they are responsible for every aspect of a firm's decisions. For example, one CEO told us that the ‘CEO is the top executive in charge of daily affairs in a firm, whose responsibilities include company operation, marketing, strategy, finance, corporate culture, human resources, employment, dismissal, compliance with laws and regulations, sales, public relations, and so on’. In contrast, CFOs mainly focus on the finance and accounting aspects of the firm. One CFO told us that ‘while the CEO is fully responsible for the operation and overall performance of the enterprise, the CFO is instrumental in determining the success or failure of the CEO's operation of the enterprise and the first person in the management of the enterprise's financial efficiency and risk’. In addition, among the CEOs and CFOs we interviewed, different from the CEOs who viewed firm reputation as important as the firm's long-term profits, the CFOs viewed financial returns and compliance as the most important factors for the firm.

Among the CEOs we interviewed, they generally viewed corporate donation both as the firm's responsibility to give back to society and as a strategic way for the firm to improve its reputation. They admitted that when deciding the amount of donation, they may also consider the firm's financial ability and the economic value of the donation, such as a tax credit. As one CEO opined, ‘Firms should make some charitable donations to serve the society when they prosper financially. It's a way of fulfilling social responsibility…Donation can also promote a sense of responsibility in the employees and improve the company's reputation. There's nothing wrong as far as you are not donating too much’. In contrast, the CFOs we interviewed generally took a cautious approach to donation. Most of them used the term ‘acting according to the firm's own abilities’ (‘量力而行’ in Chinese). According to another CFO, ‘Firms are essentially for-profit organizations. Therefore, they should first meet their own production and development demands (including R&D) and then make charitable donations according to their own abilities. With this prerequisite, charitable donations can become the icing on the cake for firms’.

Data and Sample

The sample of this study begins with all of the listed firms in China. We tested our hypotheses using Chinese data for two reasons. First, China lacks a well-developed corporate governance system (Braendle, Gasser, & Noll, Reference Braendle, Gasser and Noll2005), and board of directors are not instrumental in firm investment decisions (Chen, Sun, Tang, & Wu, Reference Chen, Sun, Tang and Wu2011; Zhang, An, & Zhong, Reference Zhang, An and Zhong2019). Therefore, firm investment decisions are subject to greater influence from top executives in China than in the United States. Second, since 2006, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has required listed firms to disclose philanthropic donations in their financial restatements. Thus, the philanthropic donation data in China are readily available. The data used in this study were mainly collected from three sources. Corporate philanthropy data were obtained from the iFinD database, which contains information on the corporate philanthropy of A-share firms[Footnote 6] in China from 2006 to 2015. Firm demographic and financial data were collected from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. These two databases have been extensively used in prior studies (e.g., Giannetti, Liao, & Yu, Reference Giannetti, Liao and Yu2015; Hung, Wong, & Zhang, Reference Hung, Wong and Zhang2012). We obtained our CEO and CFO organizational identification data through a national survey of listed companies. Specifically, we cooperated with the CSRC's Listing Department to conduct the survey at the end of 2014. The survey was mainly designed to assess the status and effectiveness of the internal control of the listed companies in China. We included the organizational identification measure to assess CEO and CFO organizational identification. The Listing Department of the CSRC distributed questionnaires with the help of its Accounting Department, the China Association for Public Companies, and the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges.

Considering that business executives are usually reluctant to participate in surveys (Chatterjee & Hambrick, Reference Chatterjee and Hambrick2007; Cycyota & Harrison, Reference Cycyota and Harrison2006), several measures were taken to increase response rate and improve data quality. First, as the scale of organizational identification was originally in English, we followed Brislin's (Reference Brislin, Triandis and Berry1980) back-translation method to translate it into Mandarin Chinese. We pretested the Chinese version of questionnaires of organizational identification in 15 A-share firms. Second, we provided three telephone numbers for consultation if the participants had any concerns or questions about the surveys. Third, we distributed the questionnaires to the listed firms with the help of the CSRC and Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. To ensure the questionnaires were completed by CEOs and CFOs, we sent a notice issued by the CSRC and the two stock exchanges, asking firm executives to answer the questionnaires truthfully and seriously. This means that answering the questionnaires is not mandatory, but if they choose to provide their answers, the questionnaires should be filled out as the things really are. Finally, we randomly chose 12 listed firms from the firms completed the questionnaires for field research. In the field research, we interviewed the CEOs and the CFOs personally, wherein we asked the same questions as those in the surveys to check whether they were familiar with the answers provided in the questionnaire surveys. All the answers we received in the interviews were consistent with those in their questionnaire surveys. Therefore, we are confident that the questionnaires were personally completed by the CEOs and CFOs.

In the end, we obtained questionnaires from 2,173 listed companies (with a response rate of 80.5%). The t-tests revealed that the 2,173 listed companies that responded did not differ significantly from other A-share firms in China in firm size, age, ownership or return on assets (ROA).[Footnote 7] In other words, the companies that participated in this national survey are representative of A-share companies in China (Conover, Reference Conover1999). In the survey, the CEOs and the CFOs of listed companies were asked to provide their own organizational identification. We excluded firms under financial distress as indicated by their special treatment status. Among all the firms in the survey, 226 of them had only one executive who responded. After matching all of the variables and dropping cases with missing values, we obtained a total of 880 firm observations. To assess the possible response bias, we again compared these 880 A-share companies with all the other A-share companies in China. The results do not indicate any significant differences between these two groups in firm size and age, state ownership, or ROA.

Among the 880 A-share companies, 93.75% of CEOs and 68.30% of CFOs were male. CEOs’ average age was 49 years, while CFOs’ average age was 45 years. CEOs’ and CFOs’ average tenure were 6 years and 5 years, respectively. Most held a bachelor's degree or higher. Over 30% of the firms were state-owned enterprises, and the average firm age was 15 years.

Measures

CEO and CFO organizational identification

We assessed CEO and CFO organizational identification using the six-item scale developed by Mael and Ashforth (Reference Mael and Ashforth1992). This scale was widely employed and validated in prior management studies (e.g., Lange, Boivie, & Westphal, Reference Lange, Boivie and Westphal2015). The CEOs and CFOs of the listed companies were instructed to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the items using a five-point Likert scale (with 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 = ‘strongly agree’). Example items included ‘When someone criticizes my company, I feel like he is criticizing me’, and ‘I usually use “we” to describe my company rather than “they”’ (α = 0.87 for CEO organizational identification; α = 0.87 for CFO organizational identification).

Corporate philanthropy

Based on prior corporate philanthropy research (Qian, Gao, & Tsang, Reference Qian, Gao and Tsang2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Choi and Li2008), we measured corporate philanthropy using the ratio of charitable donations to sales revenue. As the value of this ratio was typically quite low, we multiplied it by 10,000 to ease the interpretation of coefficient estimates. Moreover, as our survey data on CEO and CFO organizational identification, i.e., the key independent variables, were obtained in the second half of 2014 and considering the influence of temporal precedence (a condition that provides stronger support for hypothesized causal relationships in correlation research) (Brewer, Reference Brewer, Reis and Judd2000) and the possible turnover of the CEO or CFO of the firm, we employed charitable donations and sales revenue averaged over 2 years (i.e., 2014 and 2015) to generate our dependent variable.

Gender similarity

It is a dummy variable, equal to 1 when the CEO and CFO are of the same gender and 0 if otherwise.

CFO ownership

This variable was measured as the total number of shares held by the CFO divided by the total shareholding of the firm.

Control variables

We included several control variables to exclude observable confounding effects. Managerial demographic characteristics may influence corporate philanthropy (e.g., Marquis & Lee, Reference Marquis and Lee2013). Thus, we control for several CEO and CFO demographic variables, including gender (0 = female; 1 = male), age (in years), education (1 = a technical degree or below; 2 = a high school diploma; 3 = an associate degree; 4 = a bachelor's degree; 5 = a master's degree; 6 = a doctorate degree), and tenure (in years). We also control for CEO duality (1 = CEO is also the chairman of the board; 0 = otherwise) because CEOs who are board chairmen may have higher levels of decision discretion (Finkelstein, 1992).

In addition, we controlled for several firm-level characteristics known to influence corporate philanthropy (e.g., Brown et al., Reference Brown, Helland and Smith2006; Gautier & Pache, Reference Gautier and Pache2015; Li et al., Reference Li, Song and Wu2015; Lin, Tan, Zhao, & Karim, Reference Lin, Tan, Zhao and Karim2015). We controlled for firm size (the natural logarithm of total assets), firm age (in years), state ownership (1 = state-owned enterprise; and 0 = otherwise), return on equity (ROE; measured as the ratio of earnings before interest and tax on owner's equity and adjusted by industry-averaged ROE), leverage ratio (long-term debt divided by total assets). We also controlled for industry dummies (49 of them) based on the CSMAR's industry classification.

Analytical Strategy

As only firms that disclose the information of corporate philanthropy were included in our analysis and non-disclosing firms were not randomly distributed, to alleviate the endogeneity problem, we followed prior studies (Lennox, Francis, & Wang, Reference Lennox, Francis and Wang2012 Wolfolds & Siegel, Reference Wolfolds and Siegel2019) and used Heckman model to test our hypotheses. In the first stage of Heckman model, we used probit regression to predict corporate philanthropy disclosure (a dummy variable, coded as ‘1’ when the amount of corporate philanthropy is large than zero and ‘0’ if it is equal to 0 or is with missing value). Employee number (measured as the logarithmic value of employee number) is the instrument variable. In large countries like China, employing more people often helps the government alleviate the social burden, indicating the firm has a strong sense of corporate social responsibility. Thus, firms with more employees may actively disclose the information of corporate philanthropy. Empirically, the employee number is positively and significantly associated with the disclosure of corporate philanthropy (β = 0.22, p = 0.01), but it is not significantly related to corporate philanthropy (the correlation between the two was only −0.08). In the second stage of the Heckman model, we used ordinary least squares regression to predict corporate philanthropy. The inverse mills ratio obtained from the first stage model was controlled for in the second-stage model.

RESULTS

In Table 1, we report the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all the variables included in this study. In our sample, the CEOs’ and the CFOs’ average organizational identification were 4.24 and 4.23, respectively. The sampled firms donated 0.03% of their sales revenue on average.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Notes: N = 880. a, b, c denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels based on a two-tailed test.

As elaborated above, we used the Heckman model to test our hypotheses (see Table 2). The results of the first stage of Heckman model are shown in Model 1 of Table 2. The results of the second stage of Heckman model are presented in Models 2–6 of Table 2. The coefficient estimate of the inverse mills ratio is statistically significant in all second-stage models in Table 2, indicating that self-selection bias exists owing to missing values of corporate philanthropy. Thus, the Heckman model is appropriate for our analyses.

Table 2. CEO and CFO organization identification and corporate philanthropy (Heckman two-stage model)

Notes: Model 4–6 report Heckman estimates; across all models, the p-values are reported in parentheses. ***, **, * denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels based on a two-tailed test.

Hypothesis 1 proposes that CEO organizational identification is positively associated with corporate philanthropy. Model 2 of Table 2 shows that the coefficient estimate of CEO organizational identification is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.81, p = 0.00), supporting Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 proposes that CFO organizational identification is negatively associated with corporate philanthropy. In Model 2 of Table 2, the coefficient estimate of CFO organizational identification is negative and statistically significant (β = −1.18, p = 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 2. On economic magnitude, when CEO organizational identification increases by one standard deviation, corporate philanthropic donations would increase by 7.77%. In contrast, when CFO organizational identification increases by one standard deviation, corporate philanthropic donations would decrease by 9.43%.

Hypothesis 3 proposes that CFO organizational identification moderates the positive relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy. Model 3 of Table 2 shows that the coefficient estimate of the interaction term of CEO and CFO organizational identification is negative and statistically significant (β = −1.73, p = 0.00), supporting Hypothesis 3. To obtain greater insight into the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification, we plotted the interaction effect in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The moderating effect of CFO organization identification on the relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy

We used mean plus and minus one standard deviation to represent the high and low levels of CEO and CFO organizational identification (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991). In Figure 1, when CFO organizational identification considers its low value (the dotted line), we found a strong positive relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy. However, when CFO organizational identification takes its high value (the solid line), we found a negative relationship between CEO organizational identification and philanthropy. The simple slope analysis shows that CEO organizational identification positively and significantly predicts corporate philanthropy when CFO organizational identification is weak (β = 1.54, p = 0.00) but not when it is strong (β = −0.40, n.s.). These results provide further support to Hypothesis 3.

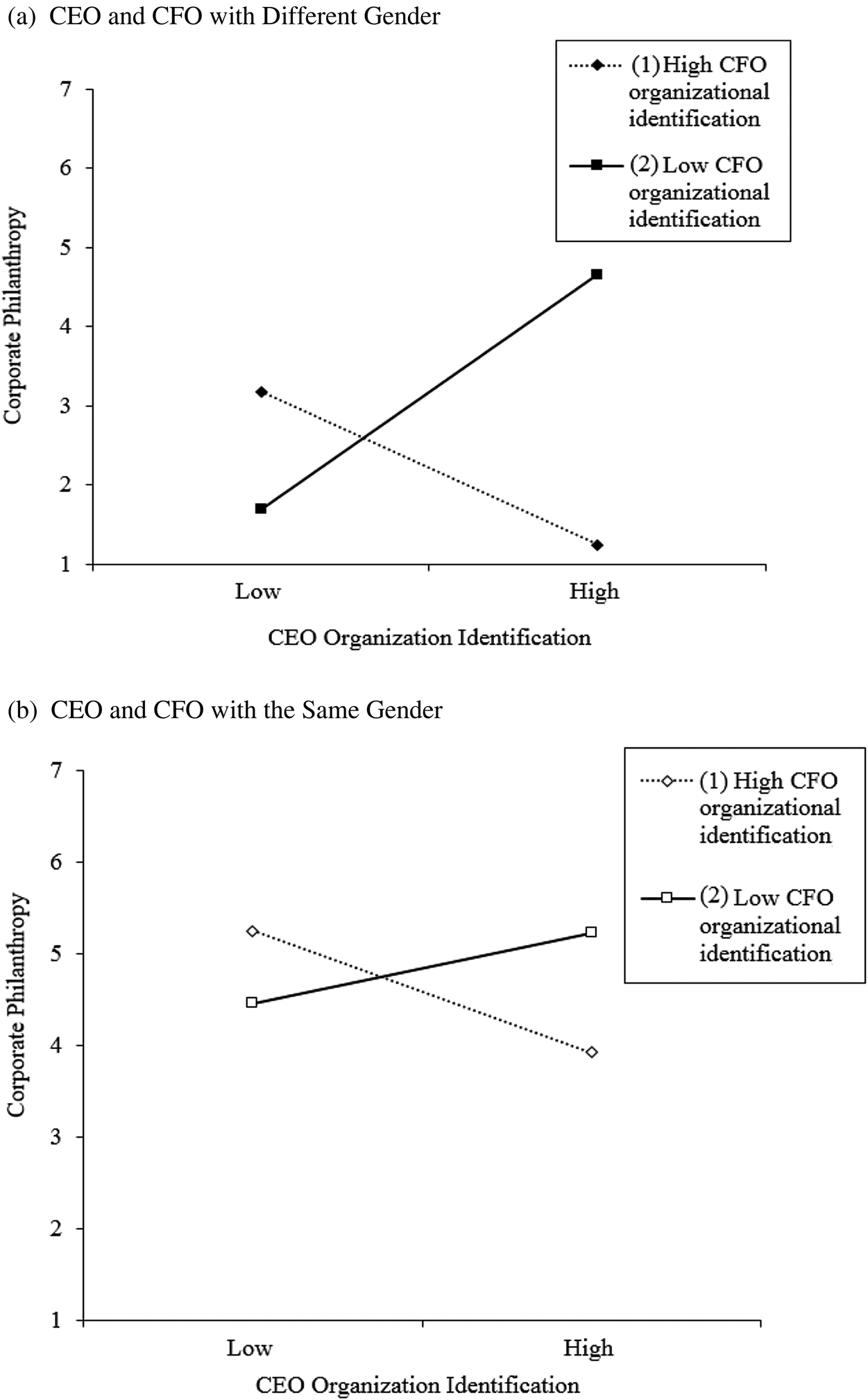

Hypothesis 4 proposes that the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification becomes weaker when the CEO and the CFO are of the same gender than when they are of different genders. In Models 4 and 6 of Table 2, the coefficient estimate of the three-way interaction term among CEO–CFO gender similarity, CEO organizational identification, and CFO organizational identification is positive and statistically significant (β = 2.10, p = 0.02; β = 1.82, p = 0.03), supporting Hypothesis 4. To obtain greater insight into the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification, we plotted the interaction effect in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The moderating effect of gender similarity on the relationship between CEO and CFO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy

In Figure 2, in the conditions when the CEO and the CFO are of the same gender, the gap in the two lines (Lines 1 and 2 in Figure 2b) representing the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification becomes smaller than the gap when the CEO and the CFO are of different genders (Lines 1 and 2 in Figure 2a). The results provide further support for Hypothesis 4.

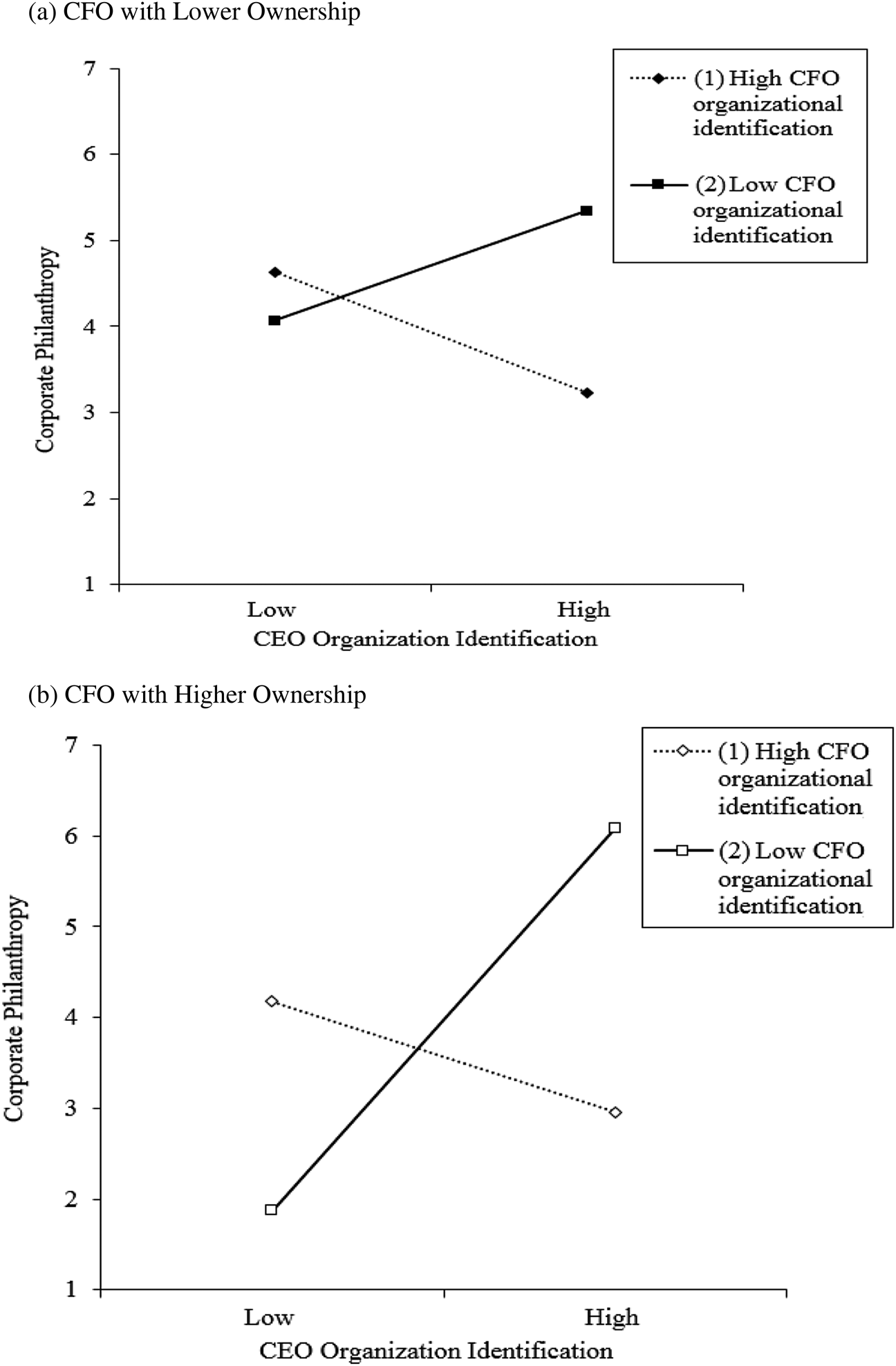

Hypothesis 5 proposes that the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification becomes stronger when the CFO has a high level (compared to a low level) of ownership. In Models 5 and 6 of Table 2, the coefficient estimate of the three-way interaction term among CFO ownership, CEO organizational identification, and CFO organizational identification is negative and statistically significant (β = −95.67, p = 0.00; β = −82.89, p = 0.00), supporting Hypothesis 5. To obtain greater insight into the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification, we plotted the interaction effect in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The moderating effect of CFO ownership on the relationship between CEO and CFO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy

In Figure 3, in the conditions when the CFO has a high level of ownership, the gap in the two lines (Lines 1 and 2 in Figure 3b) representing the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification becomes larger than the gap when the CFO has a low level of ownership (Lines 1 and 2 in Figure 3a). The results provide further support for Hypothesis 5.

Supplementary Analyses

We conducted several supplementary analyses to confirm the robustness of our results. As noted before, top executives’ characteristics can affect corporate philanthropy (Gautier & Pache, Reference Gautier and Pache2015; Marquis & Lee, Reference Marquis and Lee2013). In the first supplementary analysis, we included additional executive-level control variables.

The first is incumbent, which indicates whether there is CEO or CFO turnover in the survey year. This control variable adopts a value of ‘1’ if CEO or CFO turnover (or both) is present and ‘0’ if otherwise. We also controlled for several CEO and CFO background characteristics, including CEO throughput background (1 = CEO throughput background of production, process engineering, and finance; 0 = CEO output background of marketing, sales, product research, and development) (Waller, Huber, & Glick, Reference Waller, Huber and Glick1995), CFO throughput background (1 = CFO throughput background of production, process engineering, and finance; 0 = CFO output background of marketing, sales, product research, and development) (Waller et al., Reference Waller, Huber and Glick1995), CFO-turned CEO (1 = CEO worked as CFO previously, 0 = otherwise), and CFO on board (1 = CFO is on the board of directors; 0 = otherwise). Results after controlling for these variables are consistent with those from our main tests.

Second, in the main analyses, we used CFO ownership as the proxy of CFO structural power. However, CFO ownership may also have an important connection to the organization, which is somewhat similar to organizational identification. As such, we also conducted robustness tests using privately-controlled firms only, as CFOs seldom have ownership in state-owned firms. As reported in Table 3, the results, including those of the three-way interaction among CFO ownership, CEO organizational identification, and CFO organizational identification, are consistent with those from our main tests.

Table 3. CEO and CFO organization identification and corporate philanthropy (using the sample of privately-controlled firms only, Heckman two-stage model)

Notes: Model 1–5 report Heckman estimates; across all models, the p-values are reported in parentheses. ***, **, * denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels based on a two-tailed test.

Moreover, previous studies also used CFO relative compensation as another proxy of CFO structural power (Baker, Lopez, Reitenga, & Ruch, Reference Baker, Lopez, Reitenga and Ruch2018). Therefore, we created a composite index to operationalize CFO structural power. Specifically, the index consists of CFO ownership and CFO relative compensation. CFO relative compensation is measured as the ratio of CFO compensation in the total compensation of all directors and executives. CFO structural power is then obtained by taking the averaged value of both the standardized CFO ownership and CFO relative compensation. We examined the three-way interaction among CEO and CFO organizational identification and CFO structural power. The empirical results show that the coefficient of the three-way interaction term is negative and statistically significant (β = −1.04, p = 0.03). The results are consistent with those using CFO ownership as the proxy for structural power.

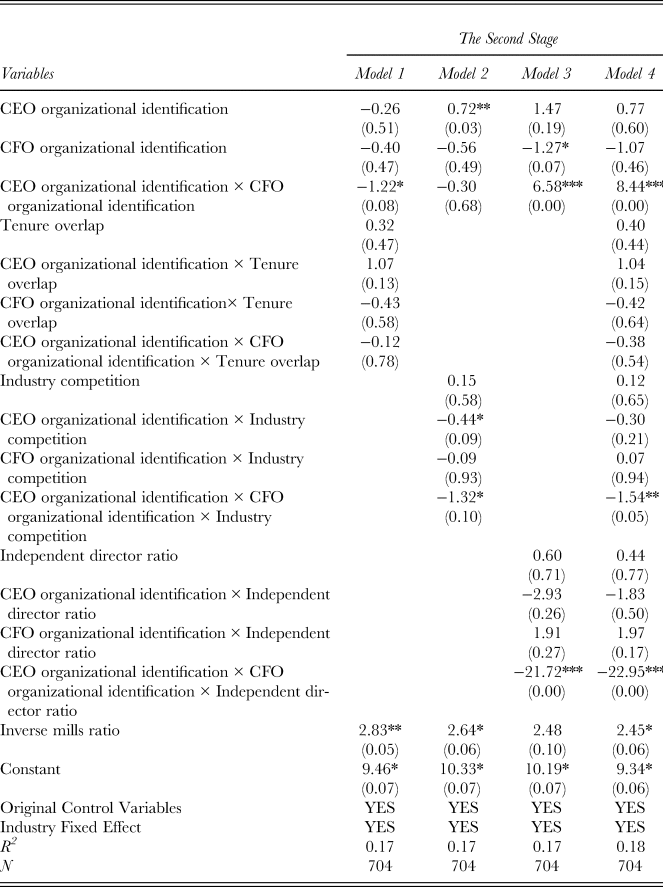

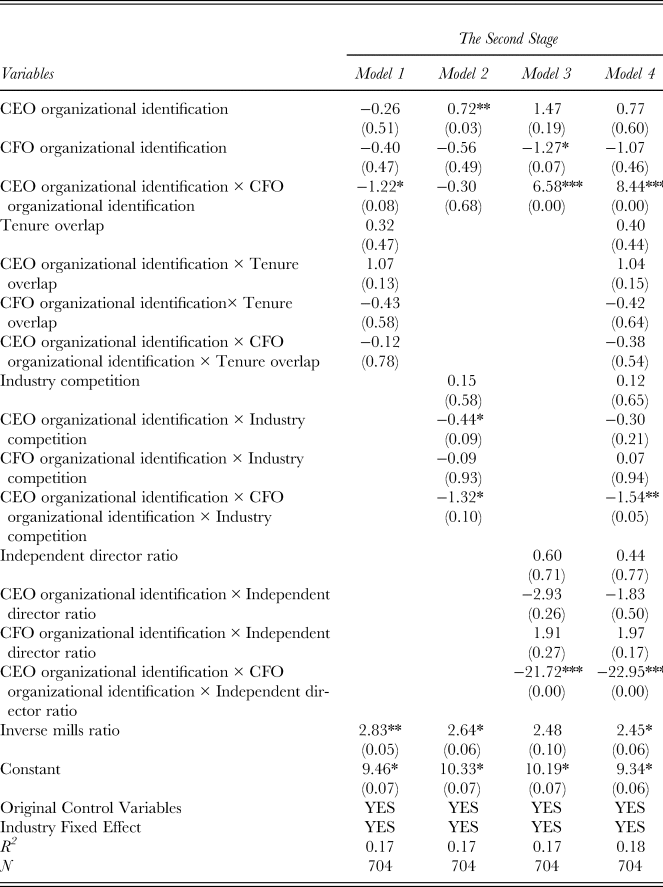

Third, we also empirically examined whether the CEO and CFO interaction effect is affected by CEO–CFO tenure overlap, industry competition, and independent director ratio. Specifically, if our theory holds, the CEO and the CFO who have been working together for a long time (i.e., having a large tenure overlap) would have developed well-defined roles. In that case, CFO organizational identification would have a stronger dampening effect on the relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy. Similarly, the industry competition (a dummy variable equaling 1 for firms in industries with an above-average level of competition as indicated by the Herfindahl index and 0 otherwise) and independent director ratio (measured as the number of independent directors divided by all the directors), which are variables representing external pressures for the CEO and the CFO, may also strengthen the interaction effect by binding them together. The results of the additional tests are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. CEO and CFO organization identification and corporate philanthropy (analyses of additional moderators, Heckman two-stage model)

Notes: Model 1–4 report Heckman estimates; across all models, the p-values are reported in parentheses. ***, **, * denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels based on a two-tailed test.

In Models 1 and 4 of Table 4, the coefficient estimate of the three-way interaction among CEO–CFO tenure overlap, CEO organizational identification and CFO organizational identification is negative, but the effect is not statistically significant (β = −0.12, p = 0.78; β = −0.38, p = 0.54). Furthermore, as shown in Models 2 and 4 of Table 4, the coefficient estimate of the three-way interaction among industry competition, CEO organizational identification, and CFO organizational identification is negative and statistically significant (β = −1.32, p = 0.10; β = −1.54, p = 0.05). In addition, results in Models 3 and 4 of Table 4 demonstrate that the coefficient estimate of the three-way interaction among independent director ratio, CEO organizational identification, and CFO organizational identification is negative and statistically significant (β = −21.72, p = 0.00; β = −22.95, p = 0.00). In summary, the results presented in Table 4 indicate that industry competition and independent director ratio, which represent the external and internal environment, significantly affect the CEO and CFO interaction effect.

In addition, we conducted some tests to compare the validity between agency theory and identification theory, which are two opposing perspectives. According to agency theory, executives with more ownership would work for the best of the firm because ownership may align executives’ interests with that of shareholders (Fama & Jensen, Reference Fama and Jensen1983). If agency theory has a high validity in explaining corporate philanthropy, we would observe the significant effects of CEO/CFO ownership on corporate philanthropy. As all the firms in our sample are listed firms, we were able to access the archival data of CEO and CFO ownership. The empirical tests show that the main effects of these two variables are not significant (β = 5.05, p = 0.19; β = −2.33, p = 0.41). Moreover, we also tested the moderating effects of CEO/CFO ownership on the relationships between CEO–CFO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy. The empirical results show that the coefficient of the interaction term of CEO ownership and organizational identification is not statistically significant (β = 3.12, p = 0.26). In addition, the interaction term of CFO ownership and organizational identification is not statistically significant either (β = 4.00, p = 0.62). In summary, the above results suggest that agency theory cannot explain corporate philanthropy in our study and that the effects of organizational identification found in our main tests may be explained by both social identity theory and role theory.

DISCUSSION

Does executives’ varying organizational identification result in the same organizational outcome? Based on both role theory and social identity theory, this study proposed that organizational identification of both the CEO and the CFO have differential impacts on corporate philanthropy. This is because CEOs and CFOs have different attitudes about the benefits and costs of corporate philanthropy for the firm due to their different role expectations, and they would act in their firm's best interests when they highly identify with the firm. Using a large sample of Chinese CEOs and CFOs, we found that CEO organizational identification is positively associated with corporate philanthropy, whereas CFO organizational identification is negatively associated with corporate philanthropy.

Our findings also indicate that CFO organizational identification attenuates the relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy. Such a moderating effect of CFO organizational identification becomes weaker when the CEO and the CFO are of the same gender as compared to when they are of different genders, but becomes stronger when the CFO has a higher level of ownership than when the CFO has a lower level of ownership. Furthermore, our supplementary analyses also demonstrate that when industry competition or the independent director ratio is high, the moderating effect of CFO organizational identification becomes stronger.

Contributions and Implications

Our findings have several important theoretical implications. First, this study advances corporate social responsibility research by highlighting the different roles of top executives in corporate social responsibility. Although previous studies have acknowledged the importance of top executives in shaping philanthropic donations, only recently have they begun to examine the deep-level psychological factors of executives (e.g., Tang et al., Reference Tang, Mack and Chen2018; Zhu & Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen2015). By showing how a top executive's role and psychological factor – organizational identification – can work together to predict corporate philanthropy, our findings indicate that corporate philanthropy decisions are subject to the different roles and motivations of different executives.

Second, our findings also contribute to strategic leadership research. The importance of CFOs in firms has grown remarkably with the increasing need for firms to control and cut costs in the past decades, particularly in Western countries (Zorn, Reference Zorn2004). Nevertheless, past studies mainly focus on the CEO or the entire top management team, while our understanding of the role of the CFO in firm investment decisions remains limited. The findings on the CEO and CFO organizational identification and their interaction effects in this study enhance our understanding of when and how the CEO and the CFO interact to influence firm decisions.

Third, our findings also extend executive organizational identification research by presenting the differential effects of CEO and CFO organizational identification and their interactions. Our study highlights the importance of incorporating executives’ roles in research on executive organizational identification. Top executives have different roles and are thus subject to distinct role expectations, which can lead to executives with strong organizational identification making different decisions. Thus, the role of organizational identification in their decisions is contingent on the expectations associated with their distinct roles. Because of the different roles they are expected to play, CEOs’ and CFOs’ organizational identification may have an inverse relationship with the firm's strategic behavior, such as corporate philanthropy. Our findings suggest the need to consider executives’ roles when studying the implications of executive organizational identification.

In addition to theoretical implications, this study is of interest to practitioners in two ways. First, our findings indicate that executives must be aware of potential cognitive biases associated with their distinct roles. CEOs with strong organizational identification are more committed to corporate philanthropy, while the opposite holds for CFOs. For CEOs with strong organizational identification and appreciation for the strategic value of corporate philanthropy, caution should be exercised to not ‘overinvest’ in corporate philanthropy. However, for those CFOs with strong organizational identification who are opposed to corporate philanthropy, philanthropic donation can have strategic implications. Second, the board of directors may be interested in our findings that indicate that the positive relationship between CEO organizational identification and corporate philanthropy is weaker when CFO organizational identification is stronger and that such a moderating effect is affected by several factors (i.e., CEO–CFO gender similarity, CFO ownership, industry competition, and independent director ratio). These findings indicate that firms’ strategic decisions are outcomes of social interactions between CEOs and CFOs. CFOs with strong organizational identification may play a peer monitoring role to prevent CEOs from making excessive philanthropic donations. Therefore, the board must guide the CFO. For example, a CEO with strong organizational identification could be paired with a CFO with the same characteristic to ensure effective strategic decisions.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has limitations that provide promising directions for future research. Although we have provided some evidence from interviews and news reports, we have not directly measured CEOs’ and CFOs’ distinct role expectations or their different attitudes toward corporate philanthropy. Future research can use survey instruments or case studies to obtain greater insight into how CEOs’ role expectations differ from those of CFOs and how they view corporate philanthropy differently. Our study has focused on corporate philanthropy because of its discretionary nature. To enhance our understanding of the differential implications of executive organizational identification, future research can investigate other strategic investment decisions and firm performance.

In addition, we focused only on two types of executives – the CEO and the CFO. The interactions between them could be very intricate (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhang and Hoskisson2019). Although we have explored some factors that can influence their interactions, future studies can continue exploring other boundary conditions of these intricate interactions. Moreover, future studies could assess the effects of other executives’ organizational identification on firm decisions and how the results might change. They can examine how board members or other executives in the top management team interact with the CEO or how executives’ detailed role differences interact with their organizational identification to influence firm behavior. Alternatively, they can examine the diversity or fault lines in the boardroom or in the top management team and how they interact with organizational identification to influence firm decisions.

Lastly, in this study, we only used cross-sectional data to test our hypotheses. This is a limitation of our study. Future research can use panel data and fixed-effect models to test whether the effects found in our study still hold. In addition, we used Chinese data to test our hypotheses as Chinese executives have greater decision autonomy due to ineffective internal and external governance mechanisms. However, China as an emerging economy has its unique informal institutions; thus, our findings may not be applicable to other countries. Comparative research is needed to understand the role of informal institutions, such as regional culture, in shaping the relationship between executive organizational identification and corporate philanthropy.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we used role theory and social identity theory to examine the differential impacts of CEO and CFO organizational identification on firm decisions. Using corporate philanthropy as our empirical context, we found that organizational identification of the CEO positively predicts corporate philanthropy while that of the CFO negatively predicts corporate philanthropy. We further found that CFO organizational identification weakens the effect of CEO organizational identification and that such an effect is affected by CEO–CFO gender similarity and CFO ownership. By conducting a survey of CEOs and CFOs of listed firms in China, we found empirical support for our hypotheses. Our findings have important contributions and implications to literature and practice.