INTRODUCTION

The socioemotional wealth (SEW) perspective has become a dominant frame in the analysis of family firms. As firms owned and controlled by families continue to play a major role in the world economy, it is important to advance our understanding of the major factors that underpin strategy and decision-making by family firms. Common theories for understanding firm behavior dominantly consider economic motives as rationale for firm strategic activity and decision-making. However, family scholars emphasize that non-economic motives play a critical role in the management of family firms, including family control, family identity, family social status and reputation, family firm intragenerational longevity and succession, and family emotional attachment. Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson, and Moyano-Fuentes (Reference Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007) used the term ‘socioemotional wealth’ (SEW) to encompass these non-economic factors that drive family firm strategy and development. Later work advanced the idea that the conservation and enhancement of SEW are at the core of decision-making at family firms and strongly affect family firm management, strategy, governance, stakeholder relationships, and entrepreneurship (Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone, & De Castro, Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011). Refinement of the SEW concept identified five key dimensions: family control and influence, family members’ identification with the firm, binding social ties, emotional attachment, and renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession, collectively known as FIBER (Berrone, Cruz, & Gomez-Mejia, Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012). Since then, the model and its dimensions have been applied in a range of studies to further construct measurement and validation (Debicki, Kellermanns, Chrisman, Pearson, & Spencer, Reference Debicki, Kellermanns, Chrisman, Pearson and Spencer2016; Hauck, Suess-Reyes, Beck, Prugl, & Frank, Reference Hauck, Suess-Reyes, Beck, Prugl and Frank2016).

Overall, SEW research is still at an early stage, and several issues remain, such as the way in which the differentiated nature of family firms – public versus private family firms, first- or later-generation family firms, small versus large family firms, and full or distributed family control of firms – is captured by SEW and its effects on firm behavior. Furthermore, we have limited insight into how the nature of SEW and its impact on family firm behavior is influenced by different institutional and cultural contexts. Moreover, questions have arisen as to whether the SEW model and its dimensions are coherent and consistent across family firms (McLarty & Holt, Reference McLarty and Holt2019; Schulze & Kellermanns, Reference Schulze and Kellermanns2015). In this article, we systematically review conceptual papers that developed the SEW concept and empirical papers that have applied SEW in the context of family firms. We pose four basic questions concerning SEW research: (1) What is SEW and how does SEW contribute to family business research? (2) Is the SEW model theoretically and empirically valid? (3) Is the SEW concept applicable in different contexts? (4) What can we do to further develop the SEW perspective in the future?

To answer the first and second questions, we first systematically clarify relevant SEW theoretical and empirical literature, using HisCite and VOS viewer tools to show the hotspot, community, theme, and development context of SEW research. Then, we conduct a theoretical and empirical analysis on representative SEW papers. Our analysis reveals that the SEW model is based on two core dimensions: social wealth and emotional wealth. In our discussion, we deconstruct the current SEW concept, explain different S-EW and E-SW logics in the dynamic changes at family firms, and assess its applicability in the Asian context. Finally, we propose some directions for future research.

By deconstructing and reintegrating the SEW concept, we make the following contributions. First, by analyzing the sources of the values pursued by family firms, in order to explain the essence, evolution, and value of applying the SEW concept, we clarify the structure and enhance the theory of SEW. Second, we propose that the uniqueness of the SEW concept into family businesses formally due to its mechanism of interaction, balance, and change between E and S values, which results in the differentiated development of family firms. A number of studies use SEW based on one dimension without considering the other, which raises questions on the internal coherence of the concept. However, the uniqueness of family business lies in how to realize or balance these different value orientations. Third, in response to recent debates and perspectives on SEW theory (e.g., Brigham & Payne, Reference Brigham and Payne2019; Debicki et al., Reference Debicki, Kellermanns, Chrisman, Pearson and Spencer2016; Schulze, Reference Schulze2016; Swab, Sherlock, Markin, & Dibrell, Reference Swab, Sherlock, Markin and Dibrell2020), we integrate the role of SEW at different levels (individual, familial, and firm levels). We suggest that social wealth is closer to a firm-level concept, while emotional wealth seems to be more individual and familial based. This raises further methodological questions, such as how SEW works in the interaction between the individual, family, and firm level, and to what extent social and emotional wealth are relevant with these different dimensions as reinforce or contradict each other. In particular, based on the unique Asian context, we suggest that the SEW framework has great potential to develop based on different cultures and contexts.

REVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SEW

To conduct our theoretical and empirical review, we searched peer-reviewed articles (including the article title, keywords, and abstract) in the Social Science Citation Index of the Web of Science database using the keyword ‘socioemotional wealth’. The literature was limited to articles on business and management, and the search yielded 654 papers. Three researchers manually reviewed every article to verify that the content focused on family business and SEW topics. We found 43 theoretical and 151 empirical papers on SEW in the past 15 years from 2007.[Footnote 1] Then, we used HisCite and VOS viewer tools to clarify the theoretical development trajectory of SEW research and analyze the empirical research and the size of the SEW effect based on different theoretical frameworks. In the next section, we review the conceptualization of SEW from different perspectives and then discuss the empirical validation of SEW in the literature.

The Research Development Trajectory and Theoretical Themes in SEW

To show the research development trajectory of SEW, we use HistCite software (Garfield, Reference Garfield2009) to conduct the citation analysis. This method can help us quickly demonstrate the development history of SEW and identify the most important as well as most recent literature in the field. Based on their local citation score (LCS), we identified the most influential articles as those with higher-than-average citation scores compared with all those in our panel (Peteraf, Stefano, & Verona, Reference Peteraf, Stefano and Verona2013). This procedure yielded a list of the 31 leading articles (see Supplementary Figure A1 and Table A1).[Footnote 2] As shown in Supplementary Figure A1, the SEW research community is dominated by several scholars, e.g., Gomez-Mejia, Berrone, Chrisman, Zellweger, and Deephouse, who lead the development of SEW theory.[Footnote 3] The paper that remains the most influential is Gomez-Mejia et al. (Reference Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007), which introduced the SEW concept. After Berrone et al. (Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012) was published, SEW research entered a period of rapid growth, empirical studies on SEW increased, and the SEW perspective was increasingly used to explain family firms’ innovative activities, transgenerational entrepreneurship, and financial performance.

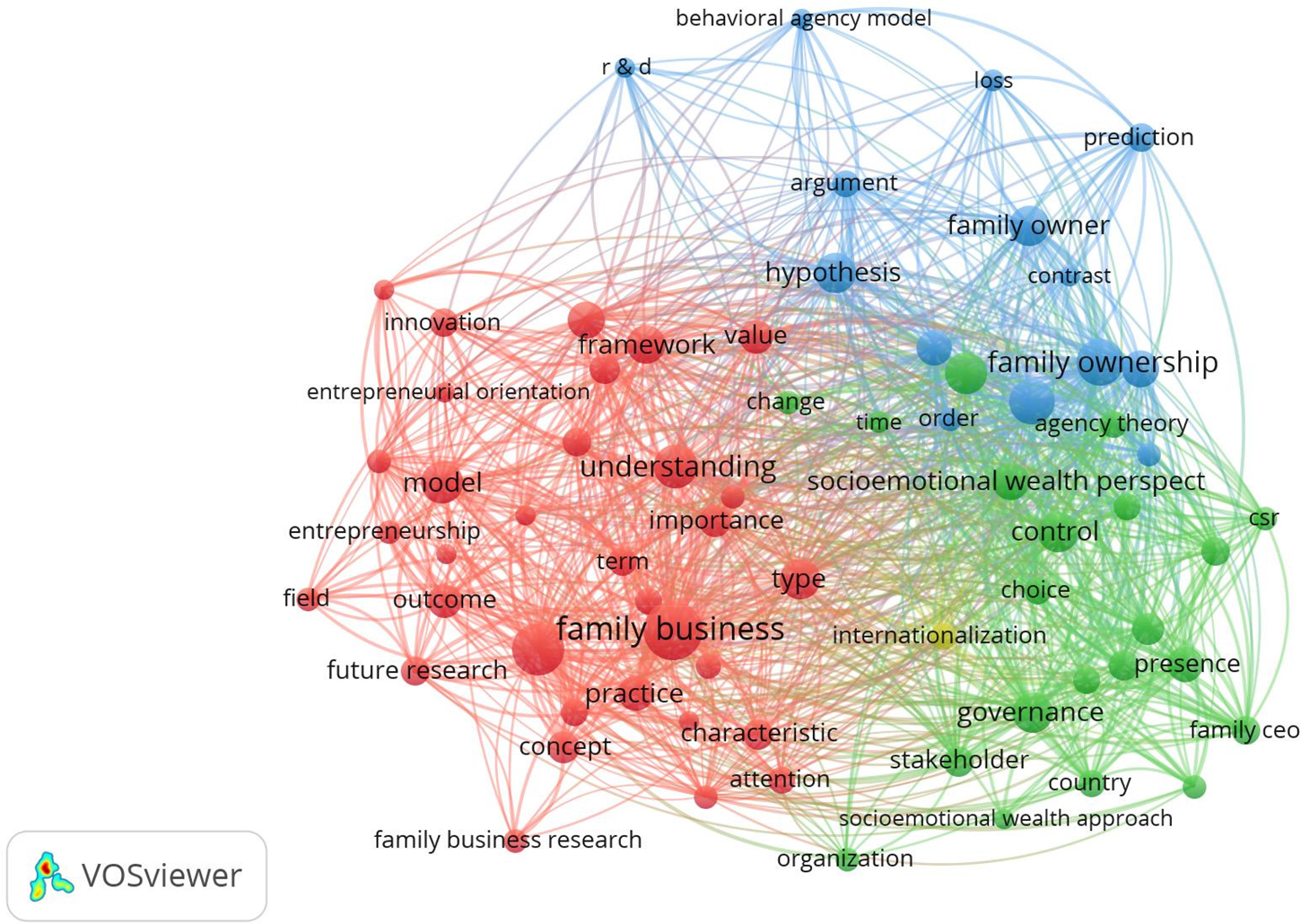

Next, we used VOS viewer software to facilitate analysis of important topics and themes in SEW over each period by examining the co-citation analysis and co-occurrence of keywords in 194 retrieved articles (Rialp, Merigo, Cancino, & Urbano, Reference Rialp, Merigo, Cancino and Urbano2019; Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010). The minimum frequency of research keyword co-occurrence was set at 10, and the results showed that 69 keywords met the requirements. As seen in Figure 1, among the most common themes, generally, three large clusters can be observed (reflected by respective colors).[Footnote 4] The first cluster (in blue) focuses on the theoretical basis of SEW, such as the behavioral agency model and agency theory, and uses the SEW concept to distinguish the family firm from other types of firms. The second cluster (in green) emphasizes family governance, family control, the role of stakeholders, the family CEO, and changeover time, which indicates that SEW research began to pay attention to the heterogeneity and dynamic changes in family business. The content of the third cluster (in red) is richer and more diverse, and the topics covered are the result of the SEW impact (e.g., innovation, entrepreneurship, and internationalization) and the elements of SEW (term/type/model/framework/characteristics, etc.). The multifaceted research on SEW in family firms can be summarized as three categories of SEW conceptual change.

Figure 1. Co-occurrence of keywords in SEW research

SEW as affective endowment of family firms

The concept of SEW was first proposed to explain the difference in risk-taking behavior between family firms and nonfamily business, such as a family firm's lower likelihood of joining cooperatives that would increase firm performance but also reduce family control (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007). SEW refers to affective endowment as ‘non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family's affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty’ (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007: 106). This definition tied SEW closely to behavioral agency perspectives and prospect theory, which are widely viewed as the basic theoretical underpinnings of SEW (Schulze & Kellermanns, Reference Schulze and Kellermanns2015). For family firm principals, risk aversion to SEW endowment loss takes priority over risk aversion to financial losses (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012; Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007), and a family firm's dominant objective is the preservation of SEW. This stream of research focuses on psychological attributes to capture a rather complex nonlinear cognitive-emotional construct. This complex and contingent SEW construct explains the specific ‘aspiration for gains and tolerance for losses’ decision criteria at family firms (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979). These studies generally consist of conceptual and theoretical analysis of SEW to compare family and nonfamily firms. Fewer empirical analyses of SEW have been conducted, and their explanatory validity remains theoretical.

SEW as cumulative stock and flow of wealth at family firms

The second category of research argues that the growth of SEW stock needs to be sustained by inflows (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, Reference Le Breton-Miller and Miller2013). In this view, SEW stock or flow (Chua, Chrisman, & De Massis, Reference Chua, Chrisman and De Massis2015) can fluctuate depending on the level of ‘familiness’ (Habbershon & Pistrui, Reference Habbershon and Pistrui2002) and other heterogeneric factors. For example, the creation and preservation of family SEW might be viewed as more important goals by firms with a high level of family involvement in management than firms with a low level of family involvement in management (Liang, Wang, & Cui, Reference Liang, Wang and Cui2014). In this view, the conceptualization of SEW can be accompanied by two effects: the ‘endowment effect’ of SEW stock and/or the incremental gain and loss effect of SEW flow (Chua et al., Reference Chua, Chrisman and De Massis2015). Scholars have used a wide range of proxy variables to reflect changes in SEW at family firms as no consensus has been reached on the measures or indicators of the level of SEW stock and its flow (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011). However, empirically it is found that families with the same characteristics (e.g., ownership ratio) can have significant differences in emotions, social capital, and family values and thus have different SEW (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012). Those issues suggest that SEW stock and flow vary across levels and family elements, and we need to further deconstruct the source of these values.

SEW as an integrated concept with different components and effects

The two perspectives discussed above generally regard the controlling family as a homogeneous group. By default, all family members are assumed to have the same degree of willingness to pursue the collective SEW (e.g., Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007; Zellweger & Dehlen, Reference Zellweger and Dehlen2012). However, SEW comprises different emotional needs by family members; therefore, the assumption of similar socioemotional needs by all family members might not hold. SEW priorities vary among family members, between generations, and among social capital networks (Nason, Mazzelli, & Carney, Reference Nason, Mazzelli and Carney2019), and SEW can also be regarded as a multidimensional concept. This has been further developed by Berrone et al. (Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012) through the FIBER framework, while also other scales have been developed, such as Debicki et al. (Reference Debicki, Kellermanns, Chrisman, Pearson and Spencer2016) and Hauck et al. (Reference Hauck, Suess-Reyes, Beck, Prugl and Frank2016). The development of multidimensional scales reflects not only changes in methodological applications but also an increase in attention paid by researchers to different influences of various SEW components. This includes research that assumes that the SEW level and its effect on firm decision-making varies with the strength of mixed characteristics at family firms. Scholars have started to indicate that SEW accrues from a variety of sources and takes different forms (Bovers & Hoon, Reference Bovers and Hoon2020).

Supplementary Table A2 provides an overview of the conceptual development of SEW, distinguishing three different approaches.

The Empirical Development of SEW

The empirical validation of SEW is built on the conceptualization of SEW. In our review of the conceptual development of SEW, we divided the conceptualization of SEW into three main types. The first type of research conceptualizes SEW as a given affective endowment in family firms from a static perspective. The second type also considers SEW as the cumulative stock and flow of wealth at family firms, but it sees SEW from a partial dynamic perspective, as it distinguishes SEW at different types of families and family firms. Most studies of these two types adopt indirect measures, such as comparing samples of family firms with nonfamily firms or using proxies to indirectly quantify SEW with secondary data extracted from databases. Some typical proxies include family control/ownership (>5%) and family management (one or more family members’ participation on the board of directors/top management team/CEO position) (e.g., Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia, & Larraza-Kintana, Reference Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia and Larraza-Kintana2010; Gomez-Mejia, Neacsu, & Martin, Reference Gomez-Mejia, Neacsu and Martin2019; Gomez-Mejia, Patel, & Zellweger, Reference Gomez-Mejia, Patel and Zellweger2018; Xu, Hitt, & Dai, Reference Xu, Hitt and Dai2020). However, it is generally agreed that using proxy measures is not an ideal approach for capturing the diversity and valence of affective values derived from family control and the theoretical construct of SEW. The third type of study views SEW as an integrated concept with multiple dimensions and uses specific measurement items to capture the construct through survey data. Nearly half of these papers (e.g., Filser, De Massis, Gast, Kraus, & Niemand, Reference Filser, De Massis, Gast, Kraus and Niemand2018; Martinez-Romero, Rojo-Ramirez, & del Pilar Casado-Belmonte, Reference Martinez-Romero, Rojo-Ramirez and del Pilar Casado-Belmonte2019) adopted the FIBER model proposed by Berrone et al. (Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012) and 27 items covering five dimensions of family control and influence, family members’ identification with the firm, building social ties, emotional attachment, and renewal of family bonds with the firm through dynastic succession.

Few studies on SEW are qualitative (e.g., Boers, Ljungkvist, Brunninge, & Nordqvist, Reference Boers, Ljungkvist, Brunninge and Nordqvist2017; Gast, Filser, Rigtering, Harms, Kraus, & Chang, Reference Gast, Filser, Rigtering, Harms, Kraus and Chang2018; Ng & Hamilton, Reference Ng and Hamilton2021; Smith, Reference Smith2016; Tomo, Mangia, Pezzillo Iacono, & Canonico, Reference Tomo, Mangia, Pezzillo Iacono and Canonico2021). Most of them also used the scale proposed by Berrone et al. (Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012). Supplementary Tables A3 and A4 summarize the empirical studies that directly and indirectly measured SEW in terms of relationships between SEW and other variables, sample size, data collection sites, and effect sizes. Although estimates of regression coefficients were reported and discussed, most of the empirical papers did not report or discuss the effect size findings of the independent variables separate from control variables (see Supplementary Tables A3 and A4). Thus, it is difficult to clearly assess the extent of the explanatory power of SEW in these studies, and it is impossible to adequately compare their main findings. Most of the empirical studies reviewed do not satisfy the current criteria of falsifiability, transparency, and discussion of effect size, which are relevant for understanding the strength of the empirical findings and drawing implications for practice (Lewin et al., Reference Lewin, Chiu, Fey, Levine, McDermott, Murmann and Tsang2016).

CHALLENGES AND CURRENT ISSUES OF SEW

We can conclude from the conceptual and empirical review that family and nonfamily firms are significantly different entities (Dyer, Reference Dyer2018), and SEW is a distinguishing feature for family firms (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011). With the deepening of research on family business behavior, the SEW framework has enhanced its explanatory power of the behavior of family firms. SEW can be seen as a concept that is rooted in individual-level characteristics of family members as well as an overarching paradigm or theoretical perspective that helps explain firm-level outcomes (e.g., Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia and Larraza-Kintana2010, Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012; Jiang & Munyon, Reference Jiang, Munyon, Kellermanns and Hoy2017; Sharma & Carney, Reference Sharma and Carney2012). On the one hand, these combined aspects enhance the explanatory power of SEW for family business, enabling scholars to explore the connotation of SEW from a multilevel and broader perspective. On the other hand, the combination of multiple perspectives creates considerable limitations that do not precisely isolate the content, cause, and effect in SEW phenomena. The analysis of our review shows that the existing SEW studies have both contributions and shortcomings in their explanations of family firms.

First, as a multidimensional concept, rather than a unidimensional concept, SEW covers non-economic orientations based on multiple relationships between family members, families, organizations, and society (Brigham & Payne, Reference Brigham and Payne2019; Swab et al., Reference Swab, Sherlock, Markin and Dibrell2020). However, at different subject levels, the value pursued can be both convergent and divergent or even conflicting. For example, the family name and family reputation enhance the personal pride and satisfaction of family members in being intimately tied to the business, and their emotional needs and family value can be satisfied or transferred to subsequent generations by controlling the business (Aronoff, Reference Aronoff2004; Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011). But sometimes firms might lose family emotional wealth for the sake of social wealth – for example, through philanthropic donations to prevent family members from fighting over family property or assets; while in another case, family firms continuously seek intergenerational emotional and non-economic wealth accumulation within the core family. This can be caused by differences and even conflicts in the pursuit of non-economic goals of family business internally (within the family) and externally (with external stakeholders), which indicates that emotional wealth and social wealth may have congruent or contradictory effects.

Second, current SEW frameworks, such as FIBER, mix the antecedents and consequences of SEW. The existing literature considers SEW the non-economic aspect of a firm that meets the family's affective needs, such as family identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and perpetuation of the family dynasty (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007). Based on our review, we find that the current SEW concept is a seductive construct that can explain a lot intuitively but explains little empirically. Further operationalization of the construct into measurable dimensions has also been problematic, leading to a fragmented and differentiated use of the construct in family firm research. Berrone et al. (Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012) believe that family control and influence should be among the key characteristics that distinguish family from nonfamily firms. However, Miller and Le Breton-Miller (Reference Miller and Le Breton-Miller2014) regard this as ‘restricted’ SEW priorities, which are highly family-centric and often run counter to the interests of nonfamily stakeholders and the firm. Factors that go beyond the family, such as a family's reputation with stakeholders and sustaining relationships with partners, really matter for the ‘extended’ priorities. Although they provide a more straightforward and context-free SEW framework, the two types of SEW are seen as somewhat opposed to each other, so they are inadequate to explain the mixed-value orientation of family business. The sources, bases, accumulation methods, and accumulation motives of the generation of emotional wealth and social wealth of family firms are often very different. Although SEW can reflect the difference between family firms and nonfamily firms to some extent (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011), combining emotional and social wealth does not explain the heterogeneity of family firms (Brigham & Payne, Reference Brigham and Payne2019; Chua, Chrisman, Steier, & Rau, Reference Chua, Chrisman, Steier and Rau2012).

This confusion not only limits the conceptual development of SEW but also constrains the empirical validation of SEW. Because conceptualization is fuzzy, a major difficulty in research on SEW concerns how to measure it in a way that allows scholars to avoid problems associated with indirect measures of SEW (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, Reference Miller and Le Breton-Miller2014) and to provide significant empirical evidence of its real effects (Schulze & Kellermanns, Reference Schulze and Kellermanns2015). As shown in our review of empirical studies, many studies adopt indirect measures or proxies, such as family control or family ownership, to measure SEW. Some studies with direct measures also adopt simplified or reduced measurement items. More importantly, most of these studies do not report or discuss the effect size of their independent variables separately from control variables, so it is difficult to clearly assess the extent of the explanatory power of SEW in these studies.

Third, extant SEW research seems to lack dimensions with cultural and institutional variation, which is acknowledged by the two major scale development studies based on Western settings, for example, Germany and the US. Family firms in societies with a strongly individualistic orientation, for example, the US, might behave differently than countries with a stronger group and/or family orientation, for example, China, especially when differences in institutions and institutional trust are considered (Peng, Sun, Vlas, Minichilli, & Corbetta, Reference Peng, Sun, Vlas, Minichilli and Corbetta2018; Redding, Reference Redding1990, Reference Redding, Yeung and Olds2000; Redding & Witt, Reference Redding and Witt2007). Most studies conducted in specific contexts of countries, for example, the US or China, adopted standardized measurement items (e.g., Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012), rather than developing contextualized items and findings. One study discussing succession at family firms in China used traditionality as its key independent variable, with two dimensions of SEW as moderators, and found that these moderators have a divergent impact on the likelihood of a family insider being chosen as successor; this gives some indication that SEW might not be so straightforward in Confucian societies (Lu, Kwan, & Zhu, Reference Lu, Kwan and Zhu2021). Those specific countries were only used as contexts for data collection, rather than for the theoretical development of SEW in different cultures. Therefore, these studies failed to indicate whether and how the specific context, for example, Asia cultures, affect and offer new insight into SEW. As an overall concept, SEW has been a well-received addition to more established theories, such as agency theory and the resource-based view. However, more conceptual clarity is required to further study the concept, in addition to the recognition of cultural and institutional underpinnings of family firms’ behavior, for example, in highly trust-based societies. Some scholars pay more attention to non-economic social aspects, such as family firm social status and reputation, whereas others focus more on the embeddedness of family identity and emotions. Therefore, we argue that it would be valuable to divide and study SEW in terms of two different but related dimensions: social wealth and emotional wealth.

RECONSTRUCTING SOCIAL WEALTH AND EMOTIONAL WEALTH

Emotional/Social Wealth Based on Different Types of Agents at a Family Business

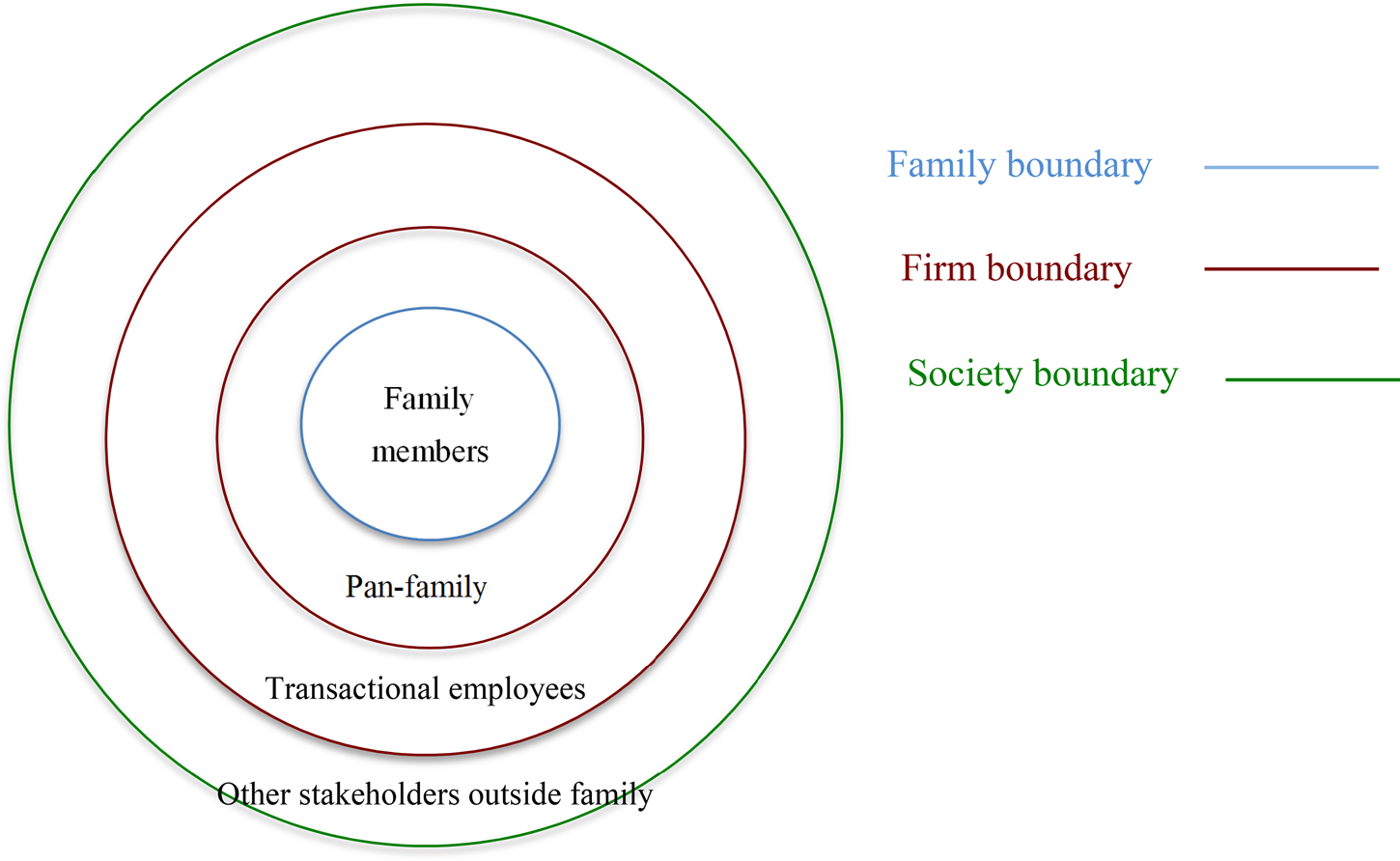

SEW is derived from affect-related values at family firms, which are significantly influenced by family relationships (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia and Larraza-Kintana2010). Family members and nonfamily employees or stakeholders are significantly different in their exchange relationships with families. These two agents have a different trust basis (Dakhli & De Clercq, Reference Dakhli and De Clercq2004; Welter & Kautonen, Reference Welter and Kautonen2005) and different degrees of emotional embeddedness (Hite, Reference Hite2003). The former agent usually views the family's thriving and sustainable growth as the most important goals and follows the ‘particularism’ principle (Parsons & Shils, Reference Parsons and Shils1951). And the latter members’ exchange is often based on the law of wider interest consideration, which focuses on the ‘universalism’ principle. Universalism refers to a value orientation toward institutionalized obligations to society, while particularism represents a value orientation toward institutionalized obligations in intimate relationships (Zurcher, Meadow, & Zurcher, Reference Zurcher, Meadow and Zurcher1965). Therefore, family business has at least four types of agents inside and outside: family members, pan- or extended family members, transactional employees, and other stakeholders outside family firms. Figure 2 illustrates this typology, showing that these four types of agents have significant differences in the pursuit of business goals, family orientation, and emotional embedding.

Figure 2. Four types of agents in family business

As mentioned earlier, in pursuing non-economic goals, some families prioritize the satisfaction of enhanced emotional needs of core family members and pan-family members, whereas other families extend their orientation to outside stakeholders, as they are also concerned with accumulating social wealth. Therefore, we conceptualize SEW and explain its two different dimensions: emotional wealth (based mostly on links within the family or pan-family) and social wealth (based mostly on links between the family firm and nonfamily stakeholders). The two dimensions, EW and SW, are not completely separate. As the agency relationship gradually shifts from close family members to members of society, the pursuit of SEW by family businesses also shifts from strong emotional wealth to social wealth.

Emotional Wealth

The original definition of SEW emphasized that its function and ultimate purpose is to meet the ‘family's affective needs’ (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007: 106). The affective needs of the family come from its formation of stable relational bonds that provide security and support developmental growth, which is the primary task of family development across cultures (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978; Rothbaum, Rosen, Ujiie, & Uchida, Reference Rothbaum, Rosen, Ujiie and Uchida2002; Shapiro, Reference Shapiro, Bennett and Nelson2010). Affective attachment as an everyday social experience (Gabb, Reference Gabb and Redman2008) can create bonds to provide care and protection and evoke emotional attachment between family members. The SEW at family firms imprints those ties derived from family employment with the characteristics of both closed (over sparse) networks and strong (over weak) ties (Cruz, Justo, & Castro, Reference Cruz, Justo and Castro2012).

According to emotional embeddedness research (Bandelj, Reference Bandelj2009), the emotional wealth of family firms can be defined as the satisfaction of family (and pan-family) members’ affective needs, which results from and is influenced by interactions and attachment between agents at family and business. Unlike nonfamily businesses, in which employees are free to leave by selling their shares, family members are generally bonded deeply to their families and businesses. Although families also pursue emotional attachment with members of society, those affective bonds are based on the enhancement of social value for their partners, which is different from the family's affective needs. The differences in family history, family structure, membership relationships, and business growth experience lead to different SEW within and between family firms. Therefore, in the following section, we try to refine the theoretical dimensions of SEW based on the source and manifestation of emotional wealth by referring to the extant literature (e.g., Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012; Debicki et al., Reference Debicki, Kellermanns, Chrisman, Pearson and Spencer2016; Hauck et al., Reference Hauck, Suess-Reyes, Beck, Prugl and Frank2016).

Family control and influence

Berrone et al. (Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012) regard family control as key characteristics of family firms to evoke SEW endowment. With SEW, family businesses are more inclined to prioritize maintaining family control, even if this might adversely affect company performance. Family control and influence should consider both ownership control and management involvement. It is through the family's actual influence on business management that the will of the family can be conveyed and become a family business, rather than just a business-owning family (Gersick, Hampton, Lansberg, & Davis, Reference Gersick, Hampton, Lansberg and Davis1997). However, founders’ control or family control form different SEW endowments at the individual and family level. Schulze (Reference Schulze2016) pointed out that a founder-controlled family firm can lead to high personal SEW wealth, which is potentially antagonistic to the development of pursuing familial SEW. For example, founders with high emotional attachment to the family firm seek longer control of the firm (to satisfy high personal affective needs), rather than transfer the business to a second generation (to create familial identification). From this perspective, private firms controlled by individuals are quite different from family businesses in the general sense, that is, firms with family members involved in management. The former is an organization that might pursue extremely high personal emotional wealth, whereas the latter regards family emotional wealth as a whole and achieves emotional satisfaction through nonfinancial activities by the firm. In terms of a research agenda, the relationship between different forms of family control and influence and SEW (specifically emotional wealth) is still poorly understood and can be further addressed, including how ownership and governance roles by various family members influence emotional wealth and whether majority ownership affects emotional wealth differently than full ownership.

Binding a kinship/close/intimate social tie

The strongest affective ties toward a social unit are formed when social exchange entails ‘high non-separability and fosters a high sense of shared responsibility’ (Lawler, Thye, & Yoon, Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2008: 524), such as in the case of close family ties. Berrone et al. (Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012) and further studies of SEW suggest that the interconnectedness of these social ties is not only between family members but can be extended to nonfamily members. For example, some family businesses have long-term partners or longtime nonfamily members who were with the family and the firm from the beginning. They share common values and have a high-level of trust with family members. These actors can be regarded as pan-family or extended family members. Other family businesses are more willing to sponsor community activities, such as charitable donations or sponsoring local sports teams. They perform these activities for either altruistic purposes or recognition. All these nonfinancial aspects help the family to gain SEW. However, the family's motivation for participating in community sponsorships or donations might differ from those of caring for the well-being of internal pan-family employees. For families, the former is to gain social recognition and maintain good social relations so as to obtain social capital and improve their corporate image and reputation (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia and Larraza-Kintana2010). The latter is to engage in relationship governance with very few nonfamily members in high-quality exchange relationships to reflect the accumulation of emotional wealth formed by family members and pan-family members with a high sense of identity and loyalty (Aldrich & Cliff, Reference Aldrich and Cliff2003). Therefore, kinship/close/intimate social ties are typical emotional wealth characteristics of SEW. In contrast, family businesses that pursue social wealth, such as external social reputation and influence, maintain looser or semi-open/friendship relationships in their social engagement.

Renewal of family bonds through dynastic succession

Successful family businesses often have a long-term orientation and sustained entrepreneurial spirit. It has two characteristics (Habbershon & Pistrui, Reference Habbershon and Pistrui2002): the family appears to be an investor and desires to create intergenerational wealth. Family businesses are oriented toward long-term development and inheritance, and their survival requires the family business to continue to innovate (Sharma, Chrisman, & Chua, Reference Sharma, Chrisman and Chua2003; Zahra, Hayton, & Salvato, Reference Zahra, Hayton and Salvato2004). Extending the family firm over different generations enhances emotional wealth through stronger bonds between the different generations and increased identification with the family firm, for example, ‘I can only lead this family firm because it was created by my parents’. However, succession also has the potential to deteriorate emotional wealth. Emotional wealth across generations does not always grow, and it can be vitiated as the number of generations increases. For example, the founders might become dissatisfied with how the new generation is running the firm, leading to a loss of identification, and the new generation might resent interference by the older generation (Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries1993). The pioneering work of Redding (Reference Redding1990) on overseas Chinese family firms discusses how complicated it can be to preserve family firms over different generations. Redding describes the third-generation trap, in which emotional attachment to a family firm is easier to maintain in moving from the first to the second generation than from the second to the third generation. This indicates that sometimes the sense of obligation by subsequent generations at family firms leads offspring to take them over despite deterioration in emotional attachment.

Social Wealth

Family firms expend energy for the good not only of the business and of family members but also the society and environment in which they are embedded (Gallo, Reference Gallo2004). We compare the attitudes of family firms and nonfamily firms toward their contributions to society for three reasons: (1) particular importance of social reputation for family firms compared to nonfamily firms; (2) stronger identification of family managers with the family firm relative to managers in nonfamily firms; and (3) importance of social capital for family firms (Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon, & Very, Reference Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon and Very2007; Carney, Reference Carney2005; Deephouse & Jaskiewicz, Reference Deephouse and Jaskiewicz2013; Dyer & Whetten, Reference Dyer and Whetten2006; Sorenson, Goodpaster, Hedberg, & Yu, Reference Sorenson, Goodpaster, Hedberg and Yu2009).

Regarding reputation, family firms do more to prevent reputational damage because it affects not just the firm but also the family and family members; this mechanism is reinforced by the strong identification of family members with the family firm (Deephouse & Jaskiewicz, Reference Deephouse and Jaskiewicz2013). Moreover, a nonfamily manager at a firm with a damaged reputation can leave for another firm, however, doing so is more difficult for a family member because of family ties and emotional attachment. Conversely, when the firm has a positive reputation, this will rub off on the family and enhance its social status and reputation. Reputation is a multidimensional concept consisting of components related to business reputation, such as product quality, innovation, service, and growth and profitability along with components related to social reputation, such as environmental responsibility, community relations, treatment of employees, ethical behavior, and charity (De Castro, Lopez, & Saez, Reference De Castro, Lopez and Saez2006). Previous research seems to confirm that family firms are more concerned with their social reputation than nonfamily firms (Dyer & Whetten, Reference Dyer and Whetten2006) and indicates that family firms are willing to sacrifice economic performance to protect their social reputation (Leitterstorf & Rau, Reference Leitterstorf and Rau2014) or have superior environmental performance to prevent damage to their social reputation (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia and Larraza-Kintana2010).

The identification of family members with a family firm is a further aspect of social wealth. Berrone et al. (Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012) pointed out that the identification of a family with a firm causes the firm to be seen by both internal and external stakeholders as an extension of the family. The family's identification with the firm forms a stronger ‘family culture’ so as to achieve the family's core values and harmonious development; it also creates a more unified image to convey the family firm's vision and values. As the external manifestation of emotional attachment, a family business is often named after the family (Rousseau, Kellermanns, Zellweger, & Beck, Reference Rousseau, Kellermanns, Zellweger and Beck2018), which further enhances integration between the corporate reputation and the family's reputation (Zellweger, Nason, Nordqvist, & Brush, Reference Zellweger, Nason, Nordqvist and Brush2013).

The importance of social capital is the final aspect of social wealth for family firms. Social capital refers to goodwill that has accumulated in social relations, which facilitates access to and leveraging of available resources (Adler & Kwon, Reference Adler and Kwon2002; Arregle et al., Reference Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon and Very2007; Zahra, Reference Zahra2010). Social capital is more critical for family firms than nonfamily firms as the former tend to build long-term relations based on trust with key stakeholders, such as suppliers and customers (Arregle et al., Reference Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon and Very2007; Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012; Carney, Reference Carney2005; Cesinger, Hughes, Mensching, Bouncken, Fredrich, & Kraus, Reference Cesinger, Hughes, Mensching, Bouncken, Fredrich and Kraus2016; Gedajlovic & Carney, Reference Gedajlovic and Carney2010). Compared to strong ties, which are the basis of emotional attachment and identification, these external social relationships by firms bring less tight social capital, but the preservation of and the goodwill from these relationships are still important for family firms as cornerstones of their social wealth. It is common for family firms to accumulate social capital from the local community to broader society (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia and Larraza-Kintana2010; Kurland & McCaffrey, Reference Kurland and McCaffrey2020; Reay, Jaskiewicz, & Hinings, Reference Reay, Jaskiewicz and Hinings2015; Zellweger & Nason, Reference Zellweger and Nason2008).

Community-level social wealth: Reputation and belongingness

Most family businesses are established and operated within a specific community. At the beginning, family firms need to pursue social wealth, such as external social reputation in the local community (e.g., Kurland & McCaffrey, Reference Kurland and McCaffrey2020). The firm needs to present itself at the community level through the development of trust, commitment, reciprocity, and a sense of shared vision (Niehm, Swinney, & Miller, Reference Niehm, Swinney and Miller2010). By doing so, family members and families can demonstrate their aspirations and social influence. This may, in turn, cause them to have greater attachment to and stronger sentiment about their communities and a greater likelihood of working for the common good of the community. This will be helpful for the successful operation of the business and enhance the sense of pride among family members and nonfamily employees. For most family businesses, success is never measured solely by the economic results achieved but also by ‘the achievement of respect gained from the surrounding community’ (Del Baldo, Reference Del Baldo2012). Therefore, by becoming more involved in local social activities, family businesses not only build an image of solidarity with the community but also obtain wider social support and value exchange from the community. This might not lead directly to economic benefits, but it is very important for maintaining the long-term orientation, continuous development, and emotional returns of the family business.

Society-level social wealth: Social legitimacy

Legitimacy refers to the recognition and evaluation of the family by other stakeholders in the broader social system, which means that the family and the firm need to comply with the requirements of the social system at the regulatory, normative, and cognitive levels or obtain their recognition and praise through strategic activities (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995). Family firms commonly achieve local legitimacy based on their close connections and contributions to the local community but enhancing legitimacy in the broader society is more of a challenge and becomes more important as the family firm expands. The legitimacy of families and family businesses in the broader society is an important part of their social wealth for the continuous development of the business. The family establishes extensive and friendly social relations with other social groups to enhance the recognition and legitimacy of the family and family firm.

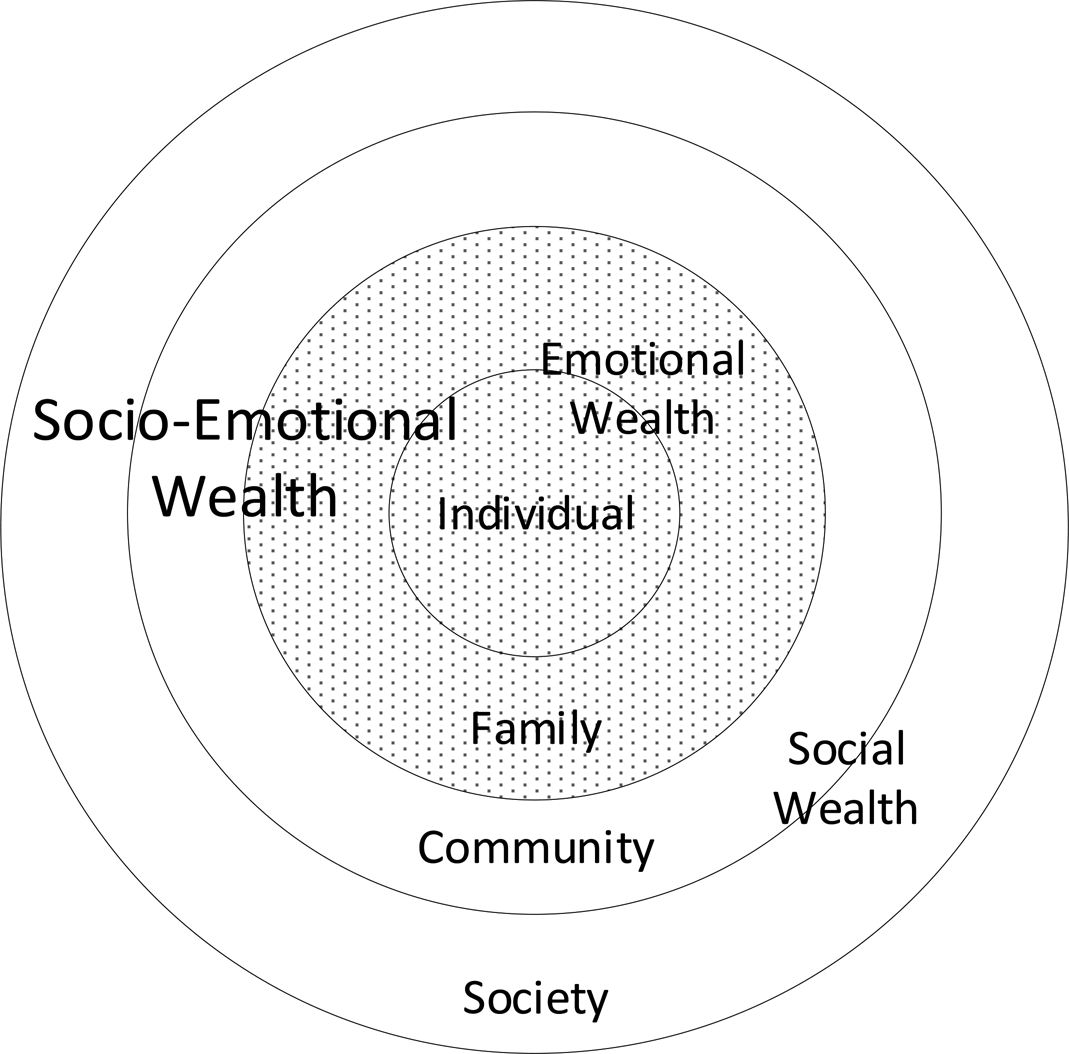

In summary, SEW consists of two key dimensions: the first is predominantly based on the wealth and meaning of the firm within the family (emotional wealth, represented by strong familial ties), whereas the second is predominantly based on the meaning and wealth of social ties with nonfamily stakeholders in the community and the broader society (social wealth). This is illustrated in Figure 3, which shows that below SEW, emotional wealth can be conceptualized as comprising individual family members, their relations with one another, and the overall family. In most cases, no conflict arises between individual and family emotional wealth; however, there are some exceptions. For the sake of family harmony, individuals sacrifice personal emotional wealth to preserve family emotional wealth. For instance, dynamic transgenerational succession maximizes family emotional wealth but might undermine some individual emotional wealth. By contrast, if a founding entrepreneur struggles to maintain control of a family firm, it preserves individual emotional wealth at the cost of losing family emotional wealth. Social wealth comprises the relationship between the family business needs and the community level as well as the societal level. The family firm's embedding in the local community and its reputation comprise their social wealth at the local community level, and social wealth is an important source of a family firm's legitimacy at the level of the broader society. We conceptualize the interaction of social and emotional wealth within family firms as a dynamic process and further explore this in the following sections.

Figure 3. Dimensions and sub-layers of SEW

The Interaction of Emotional Wealth and Social Wealth at Family Firms: Asian Family Businesses as an Example

By deconstructing SEW into emotional wealth and social wealth, we can determine the reasons for differences in the accumulation paths, goals, and orientations of SEW across family firms. This helps us understand the heterogeneity of family business. Based on the emotional wealth and social wealth dimensions of SEW, family firms can be divided into four different types, as shown in Figure 4. The first type consists of entrepreneurial family businesses, represented by high emotional wealth and low social wealth. The second type is successfully inherited family businesses with high emotional and high social wealth. The third type is professional family businesses with higher social wealth but lower emotional wealth, and the fourth type is disintegrating family businesses with low emotional and social wealth. In the Asian context, many countries or societies maintain distinctive hybrid Gemeinschaft–Gesellschaft (Tonnies, Reference Tonnies1887) relationships, and they become the basis of unique behaviors by family firms, such as the aforementioned balance and trade-off between particularism and universalism. Therefore, we examine family firms in Asia and use the EW and SW frameworks to analyze the decision logic of mixed non-economic goals of family firms.

Figure 4. Typology of family business based on emotional wealth and social wealth

Category 1: Enterprising family firm with low social wealth and high emotional wealth

This type of firm is the initial form of most family businesses, which are often entrepreneurial family firms or small private firms controlled by an individual. They seldom invest in activities that can increase social wealth but prioritize the satisfaction of the needs of the family members and harmonious development. These family firms are often family-oriented, and they are particularly concerned about the needs of family members (Ward, Reference Ward1987). Moreover, these family-oriented firms hire members of the family seeking to join the business, regardless of their qualifications or contributions to the business. The survival of the family firm and the protection of the interests of the nuclear family are the primary goals of the family business. The family's deep emotional attachment helps to enhance identification with and commitment to the family business and helps to shape the family's unified goals and consistent values, which help them to withstand the risks and uncertainties in business operation (Habbershon & Pistrui, Reference Habbershon and Pistrui2002).

However, as mentioned above, emotional wealth can be at the personal level or the familial level (Schulze, Reference Schulze2016). As a result, significant differences arise between private firms controlled by individuals and family firms that have grown over generations, although they are both high-emotion wealth-pursuing firms. The former pays more attention to the emotional embedding of individuals, especially business founders, so decision-making is often based on the expression of individual emotions. A typical manifestation is the founders’ long-term personal control of the business. The latter puts more emphasis on meeting the needs of the family, such as long-term intergenerational inheritance.

Category 2: Sustainable transgenerational family business with high social wealth and high emotional wealth

This type of family business is often the most successfully developed family business. They are concerned not only about the unity and emotional needs of the family but also about the family firm as an integral part of society. They are often adaptable family businesses that have experienced several generations of leadership changes and have survived multiple cycles of changes in the economic and social environment. As the scale of the family business gradually expands, their concept of time becomes more oriented toward the long term, focused on shifting families from participating in the internal activities of the firms to social activities with greater influence, so as to establish their core position. With the help of capable nonfamily executives, these ‘family champions of continuity’ find pathways of support among various families, industry, community, and government stakeholders to nudge the family from its strong emotional anchoring in the founder's business to entrepreneurial regeneration of the family firm (Salvato, Chirico, & Sharma, Reference Salvato, Chirico and Sharma2010).

The Lee Kum Kee (LKK) group in Hong Kong is a good example of this kind of family firm. Adhering closely to the belief that ‘harmonious families breed prosperity’ and the value of ‘considering the interests of others’ (Li, Zhu, Chen, & Fu, Reference Li, Zhu, Chen, Fu, Au, Craig and Ramachandran2011), the LKK family balances and promotes the accumulation of emotional wealth and the acquisition of social wealth to achieve continuous entrepreneurial growth of the family business. On the one hand, the LKK family deliberately designed its family governance structure to promote cooperation and prevent disruption. The family established a family council to help family members distinguish between their roles within the family and their roles as shareholders, directors, or managers. Thus, it can help to maintain a high level of identification and solidarity among family members. On the other hand, the LKK family places great importance on strengthening the shared value of ‘considering the interests of others’ in the treatment of employees and business partners. In The Power of Considering on Behalf of Others, Sammy Lee, the fourth-generation patriarch, describes how the firm gained social trust and institutional legitimacy through three key elements: empathy, concern about the feelings of others, and helicopter thinking (which refers to considering the overall interests of the entire enterprise ecosystem). In China, LKK has become a very successful long-established family business, which has been passed down for five generations and has established subsidiaries around the world.

Category 3: Professional family firms with high social wealth and low emotional wealth

One of the biggest challenges that family firms face is maintaining the success of the family firm over generations. Next-generation family firm members often lack the commitment and skills of the founding family member. One common path taken is the enhancement of the level of professional management at the family firm. These family businesses tend to follow a business-first strategic orientation, and the family becomes the steward of the business. The family name and the brand name may still be there, but the family members do not necessarily inherit the scepter. As a result, these professional companies are less able to meet the emotional needs of the core family but, rather, are more able to strengthen their value in social networks. In some cases, core family members exit the business lifecycle. For this type of family firm, the key point of strategic decision-making is preservation of the firm's social wealth, rather than retention of the family's primary emotional appeal.

An example of this type is another Hong Kong family firm, Sun Hung Kai. Kwok Tak-seng founded Sun Hung Kai (SHK) Properties in 1963, and his three sons inherited the family business after his death. The firm became one of the city's biggest development companies, building apartment complexes and developing what are now some of Hong Kong's best-known commercial buildings, including its two tallest buildings: the International Commerce Center and the International Finance Center. Although Sun Hung Kai's business is widely recognized, its family has been fighting internally and disintegrating in the course of career development. The decrease in emotional wealth might be the result of both active family choice (defamilism) and passive conflict development. However, regardless of the family, these firms maintain a strong ability to obtain social wealth through their business networks. To a certain extent, when the family completely exits the business, these companies can no longer be called family businesses. Therefore, one of the differences between family business and a purely professional company is the positive interaction between the emotional wealth from the family and the social wealth from social embedding.

Category 4: Mediocre or disintegrating family firms with low social wealth and low emotional wealth

This type of family business often has the worst performance. Such firms do not expand their social reputation and influence and reduce the emotional wealth of the family. This is often the case with companies in a recession. For example, at the Yeo Hiap Seng (YHS) company in Singapore, family members always plan for the interests of their own small families in the process of running the business. The complex relationships among family members led to a lack of common goals and mutual understanding among controlling shareholders. A series of conflicts and incidents led directly to rupture in the family's internal relations and dissipated the trust that the family had when the firm was a start-up. After the Yongtai group acquired YHS in April 1994, Yeo's family business disintegrated, and the family and business both exited the market.

The SEW of family firms, where emotional wealth and social wealth are intertwined, distinguishes them from small private companies that mainly pursue emotional wealth and professional companies that mainly pursue social wealth. For family businesses, it is important to balance the relationship between the emotional wealth generated by the family (and the pan-family) system and the social wealth generated by the enterprise system in making decisions. When the family business regards retaining emotional wealth of the family as the main orientation of the firm, they predictably pay more attention to inheritance of the firm by family members, as well as continuous family control for generations, and are less inclined to introduce professional managers or decentralize equity. However, if the family business regards the pursuit of social wealth as its main orientation, it tries to establish a strong family reputation and brand image by fostering relations with external stakeholders and contributing to the community; it is also likely to introduce nonfamily managers to achieve a higher level of professional development. These differences in SEW orientation can also help explain why the development of family businesses is very diverse.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS AND PROSPECTS

Our review of SEW research leads to several directions for future research. First, the internal logic of SEW needs to be further strengthened. The key issue that affects the strategic decision of a family business is the family's willingness to protect and improve the SEW of its members, rather than the amount of SEW they accumulate (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011). Further research can try to clarify when the protection of a certain level of cumulative SEW stock takes precedence over generating SEW flow. Also, further clarification of SEW at different levels is necessary, and ‘a reconceptualization of the construct is likely necessary’ (Brigham & Payne, Reference Brigham and Payne2019: 328). It is helpful to clarify the antecedents, consequences, and manifestations of SEW, instead of mixing them together (e.g., in the FIBER scale). The deconstruction of SEW is necessary because social and emotional wealth may be steady or in conflict at different stages, in different cultures, or in different development contexts of family businesses. We call on scholars to provide a systematic analysis of the boundaries and connotations of SEW, both SW and EW, and to develop the similarities and differences in the manifestations of SEW that can reflect family firms under different agency relationships.

Second, the dimensions of SEW and the correlation between these dimensions need to be further clarified. The strategic behavior of family businesses varies widely. It depends on factors such as their stage of development, degree of familism, and family value orientation. We cannot simply use an overall framework of SEW to explain their behaviors but, rather, need a deep analysis of the differences in the accumulation and pursuit of various dimensions of social wealth and emotional wealth at family firms, as illustrated in Figure 3. In the future, we should develop representative scale items and dimensions of emotional and social wealth, based on the framework proposed in this article.

Although some scholars, such as Miller and Le Breton-Miller (Reference Miller and Le Breton-Miller2014) and Bovers and Hoon (Reference Bovers and Hoon2020), have proposed different deconstructions of the SEW framework (e.g., restricted vs. extended SEW; achievement-related vs. ties-related SEW), we argue that, essentially, they still view SEW as a vague holistic concept, which leads to inadequate explanations of heterogeneous family firms. We believe that an important reason for this problem is that, although SW and EW are both important components of the non-economic value of family business, they have significant differences in their origin and nature. Ignoring those differences and conflating them lead to increasingly broad boundaries in the ‘umbrella’ concept growth of SEW.

Third, an avenue for further research is the question of whether feasible options are available for families to preserve their SEW outside the family firm. The wide use of family foundations suggests that, when firms are run by new generations, the emotional attachment to the firm might loosen, and this can be offset by the creation of family foundations that fulfill the goals of families and continue as a vehicle for the emotional and social bonds and wealth of the family. Moreover, the emotional wealth of the family and family firm might be able to be transferred from a family firm to a family foundation if the family has accumulated significant economic wealth over several generations, for example, established family foundations such as those of the Rockefeller, Ford, and Li Ka Shing families. Does this imply that family emotional wealth can be accumulated and maintained in various organizational forms and by maintaining some form of ownership but reducing control of family firms and/or foundations? We believe this is one direction for future research. Another relevant organizational form is that of family offices that play a key role in managing the wealth that a family has accumulated from family firm activities (Wessel, Decker, Lange, & Hack, Reference Wessel, Decker, Lange and Hack2014). Research could further investigate whether family firms at later stages of development pursue different approaches to the preservation of emotional and social wealth within and outside the family firm.

Fourth, differences in the role of the family and SW–EW between public and private firms are still poorly understood. Currently, most empirical studies on the importance of SEW focus on large publicly held family firms, and insignificant and conflicting results are common (Dyer, Reference Dyer2018; Sharma & Carney, Reference Sharma and Carney2012). If family ownership and influence are key components of SEW (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012), it is obvious that family ownership is more diffuse at public firms than private firms. However, it is not necessarily accurate to conclude that the level of SEW at public family firms is low, because social wealth can become a more dominant component of such firms. Further investigation of the dynamic interaction between emotional and social wealth in public vs. private firms is a potential topic for further research.

Fifth, the survival and growth of a family business are not a static process but, rather, a process in constant change. Therefore, family businesses also have dynamic evolution in the pursuit of emotional wealth and social wealth. Our analysis leads us to believe that the social wealth dimension of SEW could become more prominent over time, as the family firm evolves and as the pursuit of social wealth with external stakeholders expands when a family combines its family ownership with greater professionalism. Meanwhile, the family firm and its founders contemplate how the company can move into the hands of the next generation. This has repercussions for SEW, and we posit that emotional wealth, in particular, might be affected by the second-generation management of family firms as extended family members are likely to have a weaker emotional attachment to the firm than its founders. Social wealth might be affected less, but that depends on the degree to which the next generation maintains its social relations, social capital, and social reputation. In the professionalization phase, some of the social wealth might remain connected to the reputation of the family firm, and the way in which social wealth is affected depends on the degree to which the professional managers maintain the social links, reputation, and social capital. Moreover, the family can still be active in accumulating further social wealth, for example, through family foundations. Overall, the dynamics of family firms is shaped by its corporate governance and family involvement across generations in combination with its orientation on emotional and social wealth.

Lastly, the influence of different institutional and cultural contexts on the nature of SW and EW at family firms should be further investigated. Currently, theoretical and empirical SEW research is predominantly based on the experience of developed Western economies. The general relevance of SEW for family firms in an emerging economy context and non-Western context is likely to remain. Therefore, we need to re-examine the relationship between cultural contexts and SEW. For example, when we divide the concept of SEW into SW and EW, will the content and scale of SW and EW be the same or different across social contexts? We believe that the deconstruction or reconceptualization of SEW should capture its core content but without neglecting the influence of the context. For example, network-oriented firm governance has been a prevalent strategy in emerging economies (Guo, Xu, & Jacobs, Reference Guo, Xu and Jacobs2014; Luo, Huang, & Wang, Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2012), such as China. Family firms in emerging economies invest a lot of capital and energy in the construction of different types of relationships, weighing the interests of insiders and outsiders. Relationships and social ties at Chinese family firms tend to be particularistic and more personalized, whereas in the West they are often universalistic and more formal (Chen, Han, Wang, Ieromonachou, & Lu, Reference Chen, Han, Wang, Ieromonachou and Lu2021; Parsons & Shils, Reference Parsons and Shils1951; Redding & Witt, Reference Redding and Witt2007, Reference Redding and Witt2015). This might lead to a stronger focus on emotional wealth within the core family and could complicate the evolution of the firm toward accumulating social wealth by enhancing professionalism. In this article, we use the example of Asian family businesses in Hong Kong and Singapore to illustrate the differences and processes of change at family businesses in terms of SW and EW. Future research can conduct comparative research on SEW based on cross-cultural contexts.

CONCLUSION

SEW is a concept with significant traction in family firm research. The behavior of family firms is undoubtedly influenced by specific emotional and social bonds between family members and their identification with the family and the family firm. The theoretical basis, the orientation of a family firm regarding non-economic aspects of the firm often dominates the financial orientation, is sound and confirmed in various studies in which SEW is used as a latent explanatory construct (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012). We find that the direct measurement of SEW is more complex and has been used in few studies with limited explanatory power. Therefore, we suggest dividing SEW into two dimensions, EW and SW. Further research along these dimensions may provide insight into the evolution of family firms and their sources of heterogeneity, as our review shows that understanding is still limited concerning the factors that explain heterogeneity at family firms. Deconstructing SEW also offers a new perspective on other studies related to the role of the family. For instance, Burt and Opper (Reference Burt and Opper2017: 525–529) proposed a ‘cocoon theory’ about the timing when entrepreneurs ‘break’ an original family network into a more open social network. Our framework might explain the triggers and motivations for the change. We also suggest that these dimensions might differ across institutional and cultural settings and offer directions for future research. We find that the SEW concept is underused in the Asian setting, due to differences in the relevance and mechanisms of these two dimensions in the evolution of the family firm across contexts. We did not find a comprehensive paper on SEW in particular that systematically reviews and quantifies the antecedents, dimensions, and impacts of SEW in a meta-analytic framework. We hope that our deconstruction will introduce a new perspective in the study of SEW and motivate scholars to further apply and develop the SEW perspective in family business research.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2022.1