INTRODUCTION

To obtain economic advantages, leaders of family firms often seek to build ties with political elites. Such ties can be formed through developing friendships with politicians, inviting them to join the board or management team, encouraging managers to take up political positions, or by making political contributions to candidates’ election campaigns (Cooper, Gulen, & Ovtchinnikov, Reference Cooper, Gulen and Ovtchinnikov2010; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Hillman, Keim, & Schuler, Reference Hillman, Keim and Schuler2004; Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2015; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007). The social capital extracted from these connections can help a firm to reduce uncertainty and transaction costs, manage resource dependencies, and gain access to unique markets and valuable resources (Agrawal & Knoeber, Reference Agrawal and Knoeber2001; Lux, Crook, & Woehr, Reference Lux, Crook and Woehr2011; Perry & Goldman, Reference Perry and Goldman2009).

Although research on the social capital of firms has its roots in the study of family relationships and kinship (Coleman, Reference Coleman1988), such research has mainly focused on personal links, including friendships with political elites, managers’ political party memberships (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Gulen and Ovtchinnikov2010), and organization-level links such as government ownership ties (Inoue, Lazzarini, & Musacchio, Reference Inoue, Lazzarini and Musacchio2013). Research on family business can benefit from investigating family relationships and kinship ties, because many contemporary family firms continue to use kinship ties, typically through inter-family marriages, to strengthen their social capital (Bird & Zellweger, Reference Bird and Zellweger2018; Bunkanwanicha, Fan, & Wiwattanakantang, Reference Bunkanwanicha, Fan and Wiwattanakantang2013; Landes, Reference Landes2006). However, we still know little about whether or how political ties based on inter-family or political marriages contribute to the growth of contemporary family firms.

We define ‘political marriage’ as a marital relationship between a son/daughter of a family business owner and a daughter/son of a politician. Political marriage was a common strategy that ancient monarchs used to protect their interests, and this is often still the case in today's family business empires. Zhao (Reference Zhao2008) examined the Mongolian royal family's marriages from 1206 to 1368 and found that offspring of the royal family were married into ruling families of other kingdoms. This strategy was effective in strengthening the Mongolian Empire, fostering its economic growth, and expanding its territories. More recently in 2008, the marriage between Jessica Sebaoun-Darty (the daughter of the heiress of a huge French family-owned electronics vending firm [Darty]) and Jean Sarkozy (the youngest son of French President Nicolas Sarkozy) boosted investor confidence in the growth of that family firm. The price of Darty group's shares increased from 82 euros in 2008 to 170 euros by 2016. In general, both historical records and anecdotal evidence suggest that political marriage has a positive effect on firm growth.

Many firms have found that political ties are instrumental for soliciting rare resources and reinforcing competitive advantages (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Gulen and Ovtchinnikov2010; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Keim and Schuler2004; Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2015; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007). However, we suggest that models of social capital that emphasize the ‘instrumentality’ of political ties may fall short of explaining the effects of political marriage on firm growth. As a type of political tie, political marriage is an instrumental vehicle, but this vehicle is ideally based on a romantic relationship. Thus, the paradoxical nature of political marriage becomes apparent, as firms gain instrumental benefits through supposedly noninstrumental romantic relationships. The characteristic of ‘romance’ that is implicit in marriage tends to make married couples view their relationships as based on the purity of love, but this ideal stands in stark contrast to the instrumental results expected from political marriage. Thus, social capital theory has difficulty modeling this complex relationship, which is based on both instrumentality and romance.

To deal with this challenge, we integrate social capital theory with self-verification theory. With this dual-theory approach, we hope to gain a deeper understanding of the paradoxical nature of political marriage. Our findings offer a counter-intuitive prediction regarding the effects of political marriage on firm growth. We propose that political marriage has strong beneficial effects for family firms, as it enables firms to assimilate political and kinship connections to develop strong and enduring social capital (Bunkanwanicha et al., Reference Bunkanwanicha, Fan and Wiwattanakantang2013). Then, we further argue that family firms can gain greater benefits from political marriages when the marriages last longer, because these family firms can then accumulate more information and resources over a longer period.

The key caveat of the logic of social capital regarding political marriages is that these marriages serve an instrumental purpose in terms of firm growth. However, this assumption is untenable if the marriage is based on truly romantic love, rather than instrumental relations. We define ‘romantic love’ as the natural emotional attraction toward another person, which is primarily based on the strength of intimacy and passion (Sternberg, Reference Sternberg1986). Drawing on self-verification theory (Cable & Kay, Reference Cable and Kay2012; Swann, Reference Swann1983, Reference Swann2011), we counter-intuitively propose that when the offspring of family firm owners marry into politically powerful families, a strong sentiment of romantic love can undermine the benefits of these political marriages for firm growth. When such couples experience a high degree of romantic love, they are more likely to affirm their romantic bonds by disengaging from the political activities that can instrumentally benefit their family businesses. In contrast, when the degree of romantic love is low, the partners are more likely to affirm their instrumental roles by actively engaging in political acts that help the family business. Therefore, we examine how firms are most likely to benefit from political marriages by testing two moderators (i.e., duration of the marriage and degree of romantic love) and examining their joint effects on family businesses. To consider the effects of ‘instrumental love’, we test a three-way interaction model, examining the benefits of political marriages when the duration of marriage is longer (or shorter) and when the degree of romantic love is lower (or higher).

Our study makes several contributions to research on social capital. First, we examine the interacting effects of political ties and family ties by investigating how political marriages affect the growth of family firms. Thus, we contribute to the understanding of the heterogeneity of political ties and the roles these ties play in shaping firm growth (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sun, Mellahi, Wright, & Xu, Reference Sun, Mellahi, Wright and Xu2015). Second, our study contributes to the family business literature by relaxing the strict assumption that expanded family ties always have positive effects (e.g., Hsueh & Gomez-Solorzano, Reference Hsueh and Gomez-Solorzano2019). We suggest that family ties established via political marriage can have neutral or even negative effects on business growth, due to the disruptive influence of romantic love (Umphress, Labianca, Brass, Kass, & Scholten, Reference Umphress, Labianca, Brass, Kass and Scholten2003). The relationships between people bonded by marriage contracts can differ for each couple (Discua Cruz, Howorth, & Hamilton, Reference Discua Cruz, Howorth and Hamilton2013), and these differences can change the effects and uses of family ties. Third, we extend the social ties literature by taking a new approach. Instead of examining the categorical or quantitative nature of social ties, such as examining the effects of weak versus strong ties (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1983; Krackhardt, Reference Krackhardt, Nohria and Eccles1992) or of external versus internal ties (Lee, Lee, & Pennings, Reference Lee, Lee and Pennings2001), we suggest that the effects of social capital are constrained by the qualitative nature of specific social ties, such as the duration of a relationship and the level of romantic love. Based on our analysis of these qualitative factors, we offer a comprehensive research framework for examining the effects of political marriages on family businesses, and we explore three types of mediating mechanisms to deepen our understanding of the relationship between political ties and firm growth.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Social Capital Theory, Political Marriage, and the Growth of Family Firms

Social capital theory suggests that firms typically perform better when they are embedded in a wider range of exchange relationships with other organizational actors (such as competitors, customers, financial institutors, and regulators). Such well-connected firms are better able to access and mobilize valuable resources (Adler & Kwon, Reference Adler and Kwon2002; Batjargal, Reference Batjargal2003; Stam & Elfring, Reference Stam and Elfring2008). In such economic and social interorganizational networks, business–government relations play a significant role in determining the market value and the growth of a firm (Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Keim and Schuler2004; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). Political ties help firms to secure favorable regulatory conditions (Agrawal & Knoeber, Reference Agrawal and Knoeber2001), achieve legitimacy (Baum & Oliver, Reference Baum and Oliver1991), erect entry barriers (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000), and gain preferential access to credit (Claessens, Feijen, & Laeven, Reference Claessens, Feijen and Laeven2008; Khwaja & Mian, Reference Khwaja and Mian2005; Leuz & Oberholzer-Gee, Reference Leuz and Oberholzer-Gee2006). Such benefits can increase a firm's market value and stimulate its organizational growth (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). Thus, through developing its political connections, a firm can gain valuable social capital and enhance its growth (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000).

A firm's political strategy is often regarded as an important component of its overall plan for achieving business success (Chen, Sun, Tang, & Wu, Reference Chen, Sun, Tang and Wu2011). Firms establish political ties through various methods, such as developing friendships with government officials, inviting political elites to join their management teams or boards, or encouraging senior executives to take up political positions (Hillman, Zardkoohi, & Bierman, Reference Hillman, Zardkoohi and Bierman1999; Sun, Mellahi, & Wright, Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012). Family firms, however, can take advantage of a unique method of establishing political ties: the development of kinship relationships with politicians through marriages between the business owners’ offspring and government officials or their offspring (Bunkanwanicha et al., Reference Bunkanwanicha, Fan and Wiwattanakantang2013).

Political marriages help family firms develop strong and enduring political capital. As a long-term commitment, marriage can establish a strong link between two individuals and their families (Becker & Becker, Reference Becker and Becker2009). As the children of these marriages have relatives in both camps, these relationships tend to bind the two kinship groups together and strengthen their cooperation (Coontz, Reference Coontz2006). In terms of human capital, family ties work via a mutual bonding process within a closed network, which manifests itself as enforceable trust (Adler & Kwon, Reference Adler and Kwon2002; Ge, Carney, & Kellermanns, Reference Ge, Carney and Kellermanns2019). Family ties have indeed been characterized as a powerful, enduring form of social capital (Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon, & Very, Reference Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon and Very2007; Hoffman, Hoelscher, & Sorenson, Reference Hoffman, Hoelscher and Sorenson2006). Thus, political marriages can be expected to be more reliable and reciprocal than other forms of political ties that are built on friendships or strategic partnerships. Political marriages can lead to the formation of a stable network that integrates external political connections with internal family and kinship relations (Bunkanwanicha et al., Reference Bunkanwanicha, Fan and Wiwattanakantang2013). Such networks are conductive to mutual ties, social interactions, and supportive exchanges (Arregle et al., Reference Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon and Very2007). Through such business–political networks, members of family firms are more likely to gain valuable information and resources from members of political families, thus facilitating the growth of their firms.

We argue that political marriages contribute to the growth of family firms in two ways. First, this type of marriage can provide firms with access to valuable information and scarce resources (Sheng, Zhou, & Li, Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011), such as access to information about relevant government policies (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000), bank loans (Khwaja & Mian, Reference Khwaja and Mian2005), bailouts from the government (Faccio, Masulis, & McConnell, Reference Faccio, Masulis and McConnell2006), and favorable tax treatment (Claessens et al., Reference Claessens, Feijen and Laeven2008). Second, political marriages may increase the benefits of political ties by encouraging higher levels of trust between family businesses and politicians. Having family ties can reduce uncertainty, lower transaction costs, and lead to greater levels of information and resource sharing (Ensley & Pearson, Reference Ensley and Pearson2005; Luo, Reference Luo2012). Political marriages cement relationships between families, and by extension they construct secure, long-term political ties between family businesses and government officials (Bunkanwanicha et al., Reference Bunkanwanicha, Fan and Wiwattanakantang2013). These family relationship-based political ties can provide a stable foundation for the exchange of social capital between family members (Bubolz, Reference Bubolz2001). In addition, the family social networks established through political marriage can enable family firms to obtain valuable resources at lower risk and cost (Gomez-Mejia, Nunez-Nickel, & Gutierrez, Reference Gomez-Mejia, Nunez-Nickel and Gutierrez2001; Palloni, Massey, Ceballos, Espinosa, & Spittel, Reference Palloni, Massey, Ceballos, Espinosa and Spittel2001). We argue that political marriage, as a unique family–political form of social capital, facilitates the increased growth of family firms. Hence, we predict the following:

Hypothesis 1: Political marriage is positively related to the growth of family firms.

The Moderating Role of Marriage Length

The word ‘capital’ in ‘social capital’ implies an important characteristic: this kind of capital can be extended and accumulated over time. It takes time for individuals to acquire information and the know-how needed to exchange resources with each other (McFadyen & Cannella, Reference McFadyen and Cannella2004). Parties involved in long-term relationships are better able to exchange information and know-how, and therefore they typically have more effective interactions than people involved in short-term relationships (Bouty, Reference Bouty2000). Longer relationships typically involve more frequent daily interactions and greater interdependence (Adams, Laursen, & Wilder, Reference Adams, Laursen and Wilder2001). As relationships develop over time, more dynamic gains and exchanges of resources can be expected to occur (Laursen & Jensen-Campbell, Reference Laursen, Jensen-Campbell, Furman, Brown and Feiring1999). Building on social capital theory, we suggest that the length of a political marriage indicates a growing accumulation of resources created and leveraged through political ties (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). Therefore, the duration of a political marriage moderates its effects on the growth of a family firm.

Compared to family firms with nonpolitical marriage, family firms with political marriage will gain additional information and resources if the length of marriage is longer. At the beginning of a marital relationship, members of a family firm may know little about the personal social networks of the government officials they have married (Verhoef, Franses, & Hoekstra, Reference Verhoef, Franses and Hoekstra2002). A short relationship may not give the family sufficient access to useful resources. Conversely, longer political marriages provide more opportunities to develop a shared understanding and a basis for interaction between two actors over time (McFadyen & Cannella, Reference McFadyen and Cannella2004). The more encounters the offspring of family firm owners have with their parents-in-law (government officials), the more information they can accumulate, and the more knowledge they can gain on how to obtain political resources. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998) suggested that the frequency of interaction strengthens the trust, mutual obligation, and reciprocity between two parties, which in turn enhances relational capital. Such interactions may bring family businesses and government officials closer together, reduce the risk of opportunistic behavior from both sides, and facilitate deeper collaboration (Inkpen & Tsang, Reference Inkpen and Tsang2005). This relatedness can further reduce the cost of political capital exchange and facilitate the growth of a family business. On the contrary, following the logic of Hypothesis 1, as family firms with nonpolitical marriage cannot gain political capital from their offspring's marriage, the length of offspring's marriage may not add value to the firms. We, therefore, expect that the positive relationship between political marriage and the growth of family firms is stronger when the marriages last longer. Hence, we predict the following:

Hypothesis 2: The length of marriage moderates the positive relationship between political marriage and firm growth, so that the effects are more positive when the marriage lasts longer.

The Moderating Role of Romantic Love

The specific relational content of social ties can vary greatly, and this heterogeneity can influence how business owners use their interpersonal ties (Hsueh & Gomez-Solorzano, Reference Hsueh and Gomez-Solorzano2019). Literature has suggested that firms typically benefit from instrumental political connections (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Gulen and Ovtchinnikov2010; Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2015; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007). However, unlike traditional political ties that focus on instrumentality, political marriages include a noninstrumental relational element, namely the quality of romance in marital relationships. The paradox of political marriage is that family firms can obtain instrumental benefits through a purportedly noninstrumental romantic relationship. Therefore, social capital theory, which emphasizes the instrumental motivation in reciprocal exchange, cannot adequately explain the complex effects of political marriage on firm growth. In drawing on self-verification theory (Swann, Reference Swann2011), we contend the extent to which family firms can obtain economic benefits from political marriages hinges on the experienced quality of romantic love.

Self-verification theory suggests that people are motivated to ensure that their exhibited behavior confirms and reinforces their personal beliefs or views about themselves (Swann, Reference Swann2011). Individuals organize their behavior to support and reinforce their self-conceptions, and to ensure that others see them as they see themselves (Swann, Reference Swann1983, Reference Swann2011). Therefore, people view actions and behaviors that are inconsistent with their views of themselves as threatening. Such inconsistent behavior may make them feel anxious and uncomfortable. They may feel a need to disengage from anything inconsistent with or that contradicts their self-image. Political marriages present a paradox to partners involved, as they may be trapped in the dichotomous roles of both ‘romantic lover’ and ‘instrumental actor’. Thus, partners’ experiences of romantic love in their relationships may determine whether they actively engage in or disengage from political activities.

Individuals who experience high levels of romantic love are likely to see their marriages as based on true devotion and view their primary roles in the relationship as being romantic lovers. In that case, they are motivated to exhibit behavior that is consistent with such a self-view. To verify this self-identified role, the offspring of family firm owners who experience high levels of romantic love may neglect activities associated with the family business, as they seek to engage more fully in their marriages. They may deliberately distance themselves from social activities that facilitate business transactions. These people may grow unwilling to offer extra help to family business in terms of seeking and bringing valuable information or resources. They are likely to view romantic love as their primary goal and regard obtaining economic benefits via marriage as an anathema (e.g., Vernon, Reference Vernon2010). The euphoria and happiness (Fisher, Aron, Mashek, Li, & Brown, Reference Fisher, Aron, Mashek, Li and Brown2002) they experience in their romantic relationships may further reinforce their self-image, so that they direct more of their attention toward their marriage rather than business activities.

Conversely, if family firm members experience lower levels of romantic love, they may be more inclined to identify with their roles as instrumental actors in their political marriages. These people are less likely to see their marital relationships as the outcome of true love, and therefore the inherent features of political marriage may drive them to internalize the instrumentality associated with that sort of marital relationship. Consequently, partners are more likely to accept and assume roles as instrumental actors. To confirm this self-view, they are likely to actively engage in political activities in the capacity of a marital partner, and actualize the political capital embedded in their relationship for the sake of the family firm. This self-view may direct their attention and energy toward achieving instrumental goals for their family business, rather than prioritizing their romantic relationships with their partners.

Following our logic for Hypothesis 1, when family firms do not have political marriage, the firms cannot gain political capital from their offspring marriage, and thus, the self-verification process is less likely to be triggered by romantic love. We therefore propose romantic love, as perceived by the offspring of the family business owners, moderates the relationship between political marriage and the growth of the family firm.

Hypothesis 3: Romantic love, as experienced by the offspring of family firm owners, moderates the positive relationship between political marriage and family firm growth, so this positive relationship is stronger when the offspring experience a lower rather than a higher degree of romantic love.

Political Marriage, Length of Marriage, Romantic Love, and Firm Growth

On the basis of social capital theory and self-verification theory, we identify length of marriage and romantic love as two boundary conditions that affect the link between political marriage and a family firm's growth. We further argue that the strength of these two moderators may be complementary in regulating the instrumental gains of political marriage. On the one hand, when family firms have political marriage, firms may gain optimal benefits from political ties through inter-family marriage if they can accumulate political capital through longer marriages, and if the married offspring play more the role of instrumental actors than of romantic lovers in their marriage relationships. However, political marriages may fail to benefit family firms if the duration of the marriage is too short to materialize potential social capital, or if the partners prioritize their roles as romantic lovers rather than as instrumental actors. On the other hand, when family firms do not have political marriage, marital relationship does not help the firms to get instrumental access to political resources. Under such circumstance, the characteristics of marriage (e.g., length of marriage and romantic love) have less effect on firm's financial performance and growth. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 4: There is a three-way interaction between political marriage, length of marriage, and romantic love, such that the positive relationship between political marriage and firm growth is stronger when the marriage is longer and the level of romantic love is lower.

METHODS

We conducted two studies to test our hypotheses. In Study 1, we tested the relationship between political marriage and family firm growth, and the moderating effects of marriage duration and intensity of romantic love. We analyzed these factors using survey data collected from parent–child dyads of 164 family firms in mainland China. In Study 2, we conducted semi-structured interviews with eight family business owners in various provinces, including Zhejiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Hainan. These interviews were done to check the robustness of the quantitative results of Study 1, and to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the link between political marriage and family firm growth.

Study 1: Sample, Procedure, and Participants

In Study 1, participants were recruited from family firms in Shanghai, Beijing, Jiangsu, Fujian, and Zhejiang, which are major provinces of mainland China. We used three criteria suggested by Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman, and Chua (Reference Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman and Chua2012) to define family firms: (1) the business owners identified their firms as family firms (e.g., Westhead & Cowling, Reference Westhead and Cowling1998); (2) the firm was owned by its founding family (e.g., Faccio & Lang, Reference Faccio and Lang2002; Holderness, Reference Holderness2009); and (3) more than two of the family members occupied management positions (e.g., Eddleston, Kellermanns, & Sarathy, Reference Eddleston, Kellermanns and Sarathy2008).

As political marriage is a sensitive issue, the individuals and groups involved in such marriages often seek to stay ‘hidden’ in society. Individuals in political marriages are often difficult to reach, as they may be concerned about the social effects of disclosing their identities. Thus, we used snowball sampling in this study, because this approach allows the use of individuals’ social networks for accessing hard to reach or sensitive populations (Biernacki & Waldorf, Reference Biernacki and Waldorf1981; Browne, Reference Browne2005). First, we collected data from family firms with political marriage based on researcher's personal social networks. Second, to match this sample, we further collected data from family firms without political marriage with similar characteristics of firm's age, size, and industry. Following this two-step data collection method, we contacted 65 owners of family firms with political marriage and 115 owners of family firms without political marriage, respectively. In total, we distributed 180 pairs of questionnaires, which were marked with identification numbers to match the responses of family business owners with their offspring. Our research team members informed all respondents in advance of the academic purpose of the study. They also explained the procedures for implementing the survey. They assured the respondents that their responses would remain confidential and only the aggregate findings would be reported.

To collect our data on firm-level information and the characteristics of marital relationships, we invited both the owners of the family firms and their married sons/daughters to participate in our study. Two sets of questionnaires were used, one for the family business owners to report on their firms’ growth, and the other set for their married offspring, to give their perceptions of romantic love. To meet the design requirements, we contacted family firms with married offspring through the researcher's personal social networks. The surveys were administered in Chinese. To ensure their validity, we translated and then back-translated all of the measures (Brislin, Lonner, & Thorndike, Reference Brislin, Lonner and Thorndike1973).

Data on 16 dyads were removed because their questionnaires were incomplete. Therefore, the final sample for this study consisted of 164 dyadic relationships, which yielded an effective response rate of 91.1%. Male respondents constituted 73.2% of the sample (142 male firm owners and 98 male second-generation members). The mean age of the owners was 55, and approximately 38.4% of the respondents had at least a four-year Bachelor's degree (9% of the family business owners and 67.7% of their offspring). Due to the one-child policy in China (Cao, Cumming, & Wang, Reference Cao, Cumming and Wang2015), 97.56% of family business owners in our sample had only one child.

Measures

Political marriage

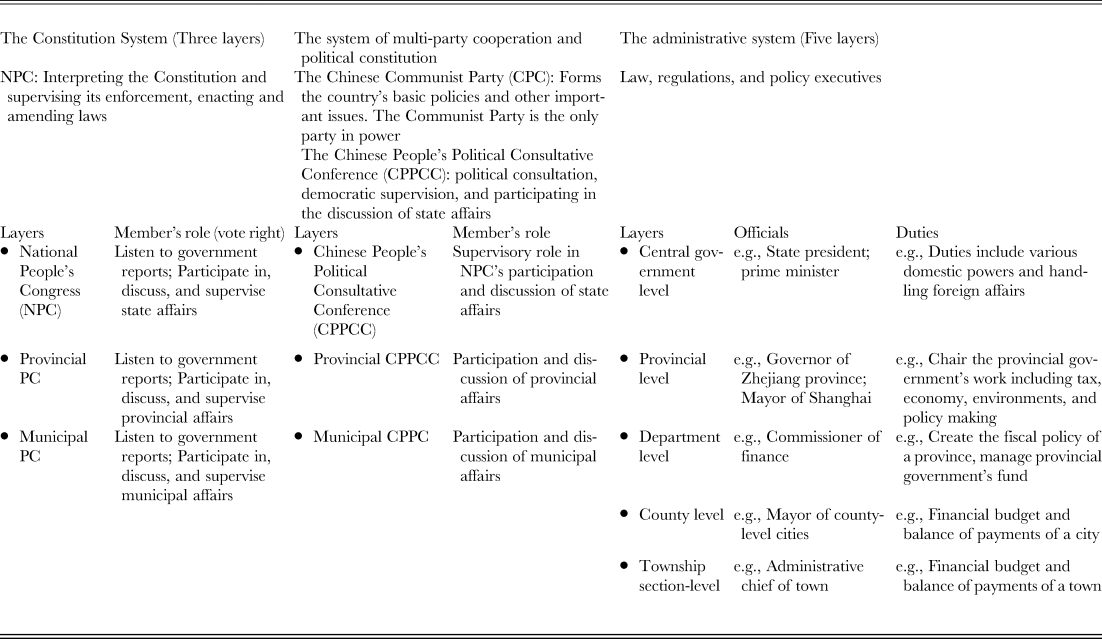

We created a dummy variable to code ‘political marriage’. If a son/daughter of a family business owner was married to a daughter/son of a politician, we coded this marriage as 1 (to indicate political marriage) and 0 otherwise. We defined politicians as people holding administrative positions at various levels of the Chinese government, because in China's political system, government officials generally have more power than members of China's ‘parliaments’ to provide political resources for family firms.

China has two parliaments: the People's Congress (PC) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPC). Previous studies have used memberships of entrepreneurs or top management team members in the PC or CPPC to measure the political ties of Chinese firms (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Sun, Tang and Wu2011). However, members of the PC only have the right to submit bills, suggestions, and recommendations in congress, and have no authority to make real government decisions. The CPPC functions more like a political consultation council and has even less power to influence government decisions and policies. Both the PC and CPPC are regarded as ‘rubber stamps’, because all of the Chinese government's decisions are made by the state's executive organs (Pei, Reference Pei1995). We argue that members of the PC and CPPC who are not government officials are less likely to obtain access to the scarce political resources controlled by governments. Government officials who hold real political positions, such as mayors and municipal party secretaries of cities, are the actual controllers of valuable political resources in China. Therefore, to ensure that family firm offspring can access sufficient political capital via political marriage, we only defined political marriage when political actors hold administrative positions.

In the Chinese administrative system, the political powers of government officials can be classified into five levels: the central government level (e.g., state president and prime minister), the provincial level (e.g., governors, ministers of education, and finance ministers), the department level (e.g., Chief of the Bureau of Public Security of Shanghai), the county level (e.g., mayors of county-level cities), and the township section-level (e.g., administrative chiefs of towns) (Chen, Li, & Zhou, Reference Chen, Li and Zhou2005). A town chief is responsible for the local financial budget and balance of payments, social stability of the town, management of enterprises, and environmental governance. Township section-level officials have sufficient power to make policies that can affect the growth of local firms, such as setting compensation packages, credit policies, and taxation policies. Thus, for our sample, we selected government officials in political positions higher than the township section-level, to guarantee the political capital involved in a political marriage was sufficient. Out of the 164 dyadic relationships in our sample, 63 (38%) of the family firms were involved in such political marriages. Table 1 illustrates the political system of China.

Table 1. Political system of China

Length of marriage

We measured the length of marriage by asking the children of family business owners, ‘How long have you been in your marriage relationship'?

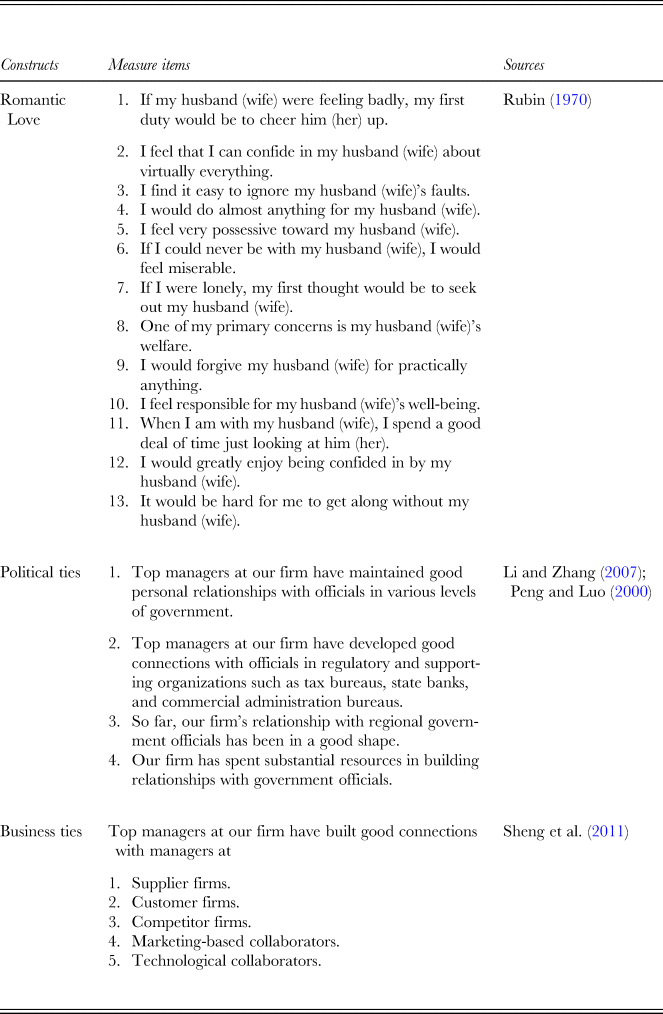

Romantic love

We used a 13-item scale (Rubin, Reference Rubin1970) to measure romantic love, as reported by respondents from the family firms. Examples of these items included the following: ‘If my wife/husband were feeling bad, my first duty would be to cheer her/him up’, ‘I feel that I can confide in my wife/husband about virtually everything’, ‘I find it easy to ignore my wife/husband's faults’, ‘When I am with my wife/husband, I spend a good deal of time just looking at her/him’, and ‘It would be hard for me to get along without my wife/husband’ (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The items of the romantic love scale are listed in Appendix I. Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.86. The item scores were averaged to form overall scores for romantic love.

Family firm growth

We used two indicators to measure firm growth: the rate of growth in assets (e.g., McGuire, Sundgren, & Schneeweis, Reference McGuire, Sundgren and Schneeweis1988) and the rate of growth in the number of employees (e.g., Batt, Reference Batt2002). To measure the rate of asset growth, we asked a single question: ‘What is the average rate of growth in assets for your company over the last three years'? Respondents are required to answer the question by using a percentage and the ratio can be either positive or negative. The second question concerned growth in the rate of the number of employees: ‘What is the average rate of growth in your company's number of employees over the last three years'? Respondents are also requested to use a ratio to show the firm's growth rate of the number of employees. These questions were answered directly by the owners of the family firms.

Control variables

We controlled for the characteristics of family business owners and their married children, political power of the government officials, management and political ties of the companies, and firm-level variables (e.g., size and age) that could influence the growth of family firms. We controlled for demographic attributes of both family firm owners and their offspring, namely gender, age, and education level. In considering the career choices of the family business owner's children could affect their commitment to the business (Sharma & Irving, Reference Sharma and Irving2005), we controlled for the effect of the second generations’ occupations, to rule out the influence of occupation on their participation in the family business. We used a dummy variable to measure whether the child of a business owner worked in the family business. For firm-level control variables, we measured firm size by the logarithm of the number of employees (Guthrie & Olian, Reference Guthrie and Olian1991). Prior studies have suggested that large firms are more likely to have the necessary resources to engage in political activity (Meznar & Nigh, Reference Meznar and Nigh1995). We also included industry dummy variables to control for the effects of different industries on a firm's growth.

In addition, we sought to separate out the effects of other types of social capital beyond political marriage by controlling for the effects of business ties and political ties for each family firm (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). We measured business ties by using the 5-item scale developed by Dubini and Aldrich (Reference Dubini and Aldrich1991) and Peng and Luo (Reference Peng and Luo2000). This scale captured the extent to which firm executives had good relations with different market players. A sample item was ‘Top managers at our firm have built good connections with managers of our supplier firms’. Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.81. We used a 4-item measure to capture political ties, which can describe the connections between a firm and the various levels of government (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). Sample items were (1) ‘Top managers at our firm have maintained good personal relationships with officials in various levels of government’ and (2) ‘Our firm has devoted substantial resources to building relationships with government officials’ (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Cronbach's alpha for this measure was 0.84. All of the items in the scales for measuring business ties and political ties are listed in Appendix I. Moreover, we controlled for the effects of government officials’ political ranks, because the different levels of political power held by politicians determine their ability to allocate resources (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi, Wright and Xu2015). We measured the government official's rank by using civil service levels and ranking system in China. After we dropped all of the control variables, the results remained the same.

Results for Study 1

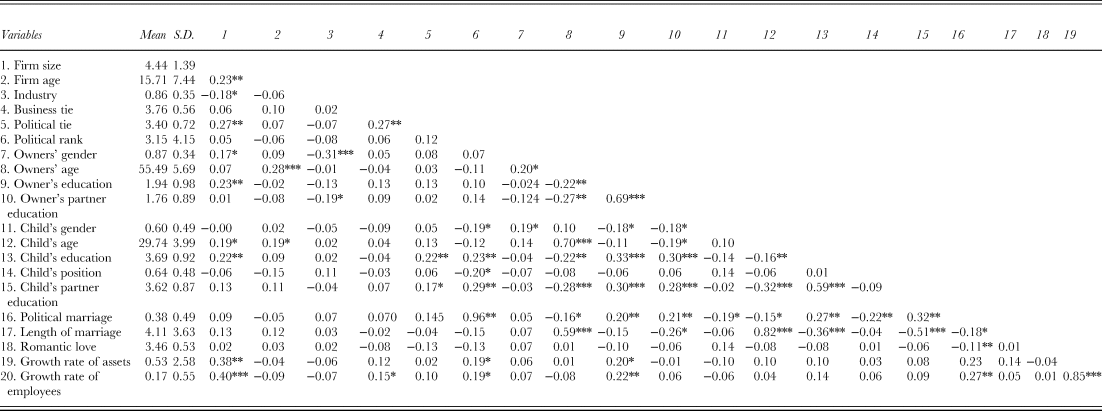

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and the bivariate correlations for the main variables. Political marriage was positively related to both the growth rate of firm assets (r = 0.23, p < 0.01) and the rate of growth in the numbers of employees (r = 0.27, p < 0.01). Romantic love was not significantly correlated with the growth rates of assets or of the number of employees.

Table 2. Means, standards deviations, and correlations

Notes: N = 164; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

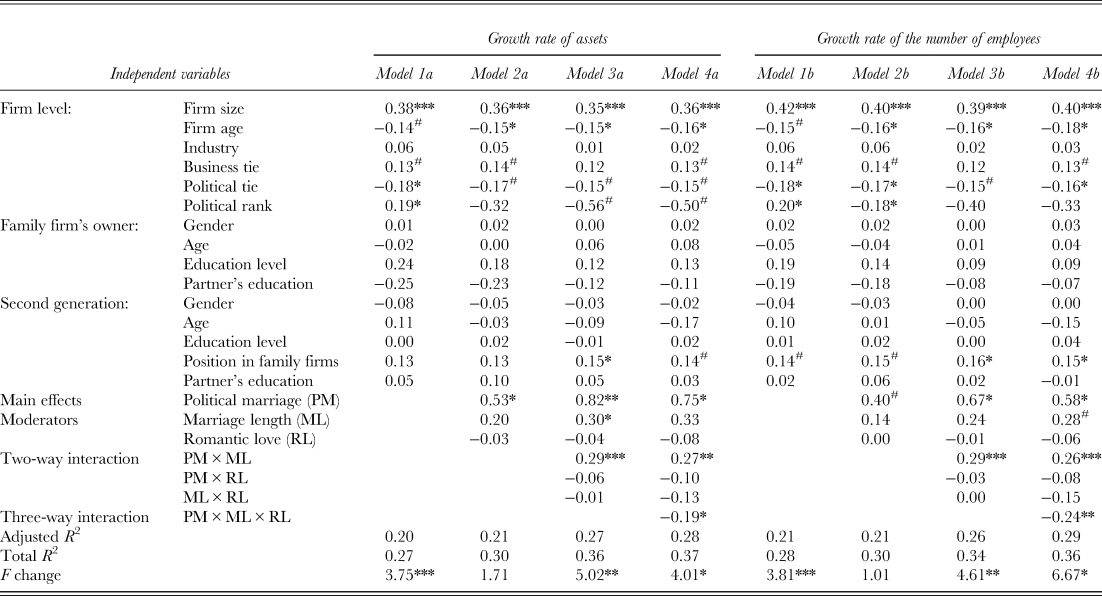

We performed a hierarchical linear regression to test the hypotheses by using control variables, independent variables, and all of the higher order interactions of political marriage, length of marriage, and romantic love, as predictors of firm growth. To minimize any potential problems of multicollinearity, the variables of political marriage, length of marriage, and romantic love were standardized prior to the analysis (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991). We entered these variables in the regression analyses in four hierarchical steps: (1) control variables, (2) three main effects (political marriage, length of marriage, and romantic love), (3) three two-way interactions, and (4) three-way interaction. We tested for the presence of multicollinearity in each model, and the values of the variance inflation factors were all less than 10.0, which indicated no multicollinearity (Kutner, Nachtsheim, & Neter, Reference Kutner, Nachtsheim and Neter2004).

Table 3 gives the results of the regression analysis with interaction effects. In support of Hypothesis 1 (the positive effect of political marriage on firm growth), the beta associated with political marriage was statistically significant and positive in the regression models on both the growth rate of assets (Model 2a, Table 3; β = 0.53, p < 0.05) and the growth rate of the number of employees (Model 2b, Table 3; β = 0.40, p < 0.1). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Table 3. Results of regression analyses predicting firm growth

Notes: N = 164 unstandardized beta are reported. #p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

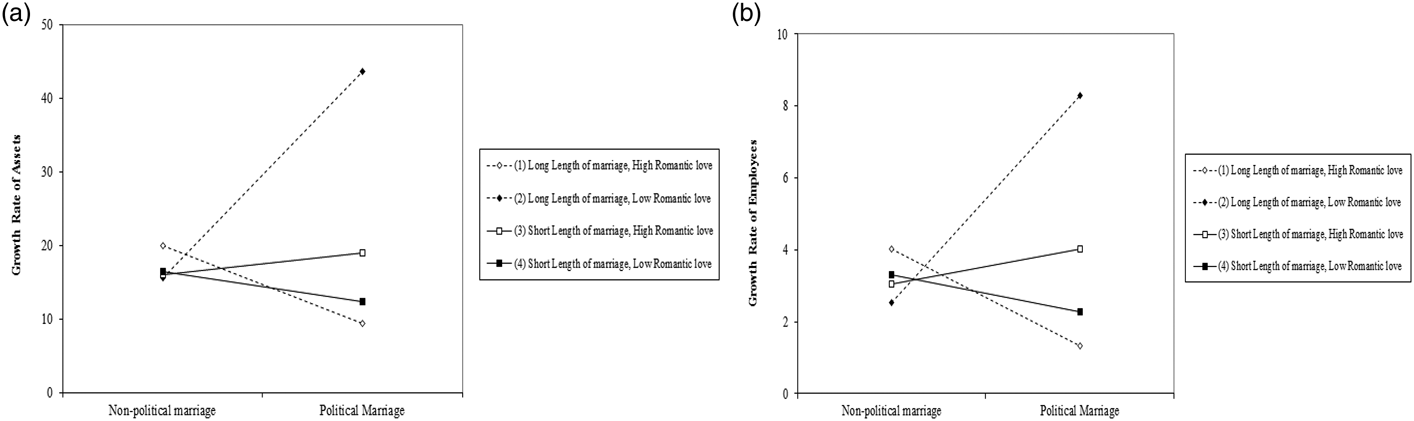

Hypothesis 2 predicted a two-way interaction between political marriage and the length of marriage would affect the rate of firm growth. As shown in Model 3a and Model 3b in Table 3, this two-way interaction was positively and significantly related to the rate of growth in assets (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) and the rate of growth in the number of employees (β = 0.29, p < 0.001). Simple slope tests further confirmed in longer marriages (1 SD above the mean), the relationship between political marriage and the rate of growth in assets was positive and significant (β = 2.92, p < 0.001). For shorter marriages (1 SD below the mean), the relationship between political marriage and the growth rate of assets was less significant (β = 2.09, p < 0.05). In addition, longer political marriages (1 SD above the mean) were found to result in a significant relationship between political marriage and the rate of growth in the number of employees (β = 0.87, p < 0.001). For shorter political marriages, this positive relationship was less significant (β = 0.59, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. The two-way interaction is plotted in Figures 1a and 1b.

Figure 1. Effects of the two-way interaction: (a) Effects of the two-way interaction of political marriage by the length of marriage on the growth rate of assets. (b) Effects of the two-way interaction of political marriage by the length of marriage on the growth rate of the number of employees.

Hypothesis 3 proposes romantic love weakens the positive effects of political marriage on firm growth. However, the interaction term was not significantly related to the rate of growth in assets or in the number of employees. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was not supported.

Hypothesis 4 predicts a three-way interaction effect of political marriage, length of marriage, and romantic love on firm growth. As Models 4a and 4b show, the three-way interaction term was significantly related to the rate of growth in assets (β = −0.19, p < 0.05) and the rate of growth in the number of employees (β = −0.24, p < 0.01). The Cohen's f square of Model 4a is 0.159 which is over the medium critical value suggested by Cohen (Reference Cohen1988). The Cohen's f square of Model 4b is 0.16 which also shows the medium effect size. We then conducted simple slope tests to further confirm our findings. We found that political marriage was positively related to family firm growth for longer marriages with lower levels of romantic love (simple slope test: β = 2.01, p < 0.001). The other three slopes, for longer marriages with higher levels of romantic love (β = 0.47, n.s.), shorter marriages with higher levels of romantic love (β = 0.42, n.s.), and shorter marriages with lower levels of romantic love (β = −0.59, n.s.), had no significant effect on family firm growth. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was not supported. Three-way interactions are plotted in Figures 2a and 2b. These figures show that political marriage had the strongest positive relationship with the rate of growth in assets and in the number of employees when marriages were longer, and the level of romantic love was low. These results supported Hypothesis 4.

Figure 2. Effects of the three-way interaction: (a) Effects of the three-way interaction of political marriage by the length of marriage by romantic love on the growth rate of assets. (b) Effects of the three-way interaction of political marriage by the length of marriage by romantic love on the growth rate of employees.

Study 2: Semi-Structured Interviews

To better understand the mechanisms underlying the links between political marriage, growth of family firms, and contextual effects of romantic love, we conducted a qualitative study. We considered family businesses that have political marriages commonly avoid revealing their growth strategies to the public, and usually keep their plans to themselves. In this situation, we deemed a qualitative research design that was particularly appropriate for our research purpose of seeking to understand the pathways of how political marriage contributes to a family firm's growth (Yin, Reference Yin1994).

Interviews are a useful and highly efficient way to collect primary data in case studies (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007), especially in cases where the phenomenon of interest is highly sensitive and uncommon (e.g., political marriage). Thus, given the importance of interviews as a powerful means of gaining in-depth understanding of the respondents’ experiences (Thompson, Locander, & Pollio, Reference Thompson, Locander and Pollio1989), we conducted a series of semi-structured interviews to find out what family business owners thought about the relationship between political marriage and firm growth.

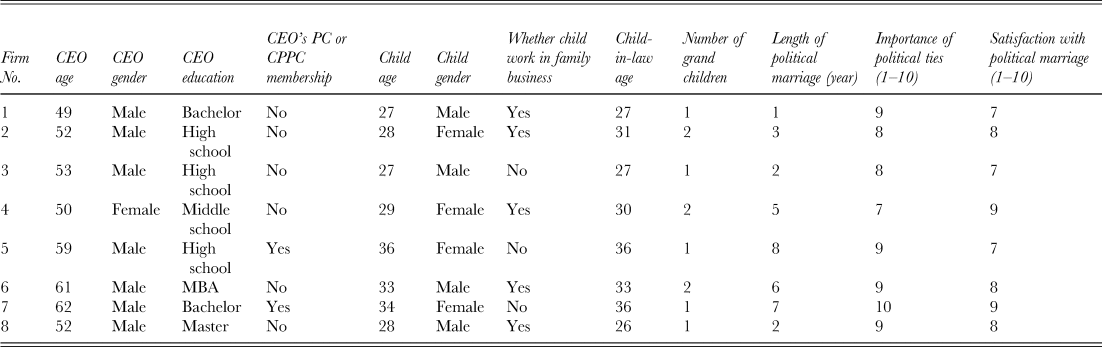

Following Eisenhardt's (Reference Eisenhardt1989) recommendation that researchers should select between four and ten cases in qualitative studies, we interviewed eight owners of family firms with political marriages, all of whom had completed our surveys in Study 1. These firm owners were asked to provide qualitative descriptions of how political marriages had contributed to their family firm's growth. We first randomly selected 20 family businesses with political marriages from Study 1 and collected the business owners’ contact details via the researcher's personal social networks. Then, we contacted these owners’ businesses via phone or WeChat, and eight of them agreed to participate in our study. Among these participating family business owners, seven were men and one was a woman, and their ages ranged from 49 to 61. Table 4 presents the demographic information of these interviewees.

Table 4. Descriptive information of interviewees

During the interviews, we first asked the respondents to rate the importance of political ties for their family firm's growth on a scale of 1 (unimportant) to 10 (very important). Table 4 illustrates these family business owners’ ratings on the importance of political ties and their levels of satisfaction with their children's marriages. All of the respondents in our study suggested that political ties were important in helping them run their businesses in China, with an average rating of 9.13 out of 10 (see Table 5). Then we asked the family business owners several questions related to marriage partner selection, political ties, and the value of marriage to their family firms. For instance, we asked several questions about their values regarding marriage, such as ‘What are the key factors influencing your choices of marriage partners, and why’? ‘What are the key factors influencing your choices of a son-in-law or daughter-in-law, and why’? ‘What roles did these factors play in the process of selecting your children's marriage partners'?

Table 5. Key initial concepts and examples of interview quotes

In addition, we asked the respondents a number of questions related to political ties, such as the following: ‘In the Chinese context, what kinds of resources do you need to run a business'? ‘How do political ties influence your business's performance and growth'? ‘What are the key differences between family ties and ordinary social ties'?

To further explore their attitudes toward family ties, we asked three key questions about the value of political marriage for family firms: ‘How do you view the political ties established via your child's marriage'? ‘How does this kind of special political tie influence your strategic decision-making'? ‘How does political marriage contribute to or hinder your family firm's growth'?

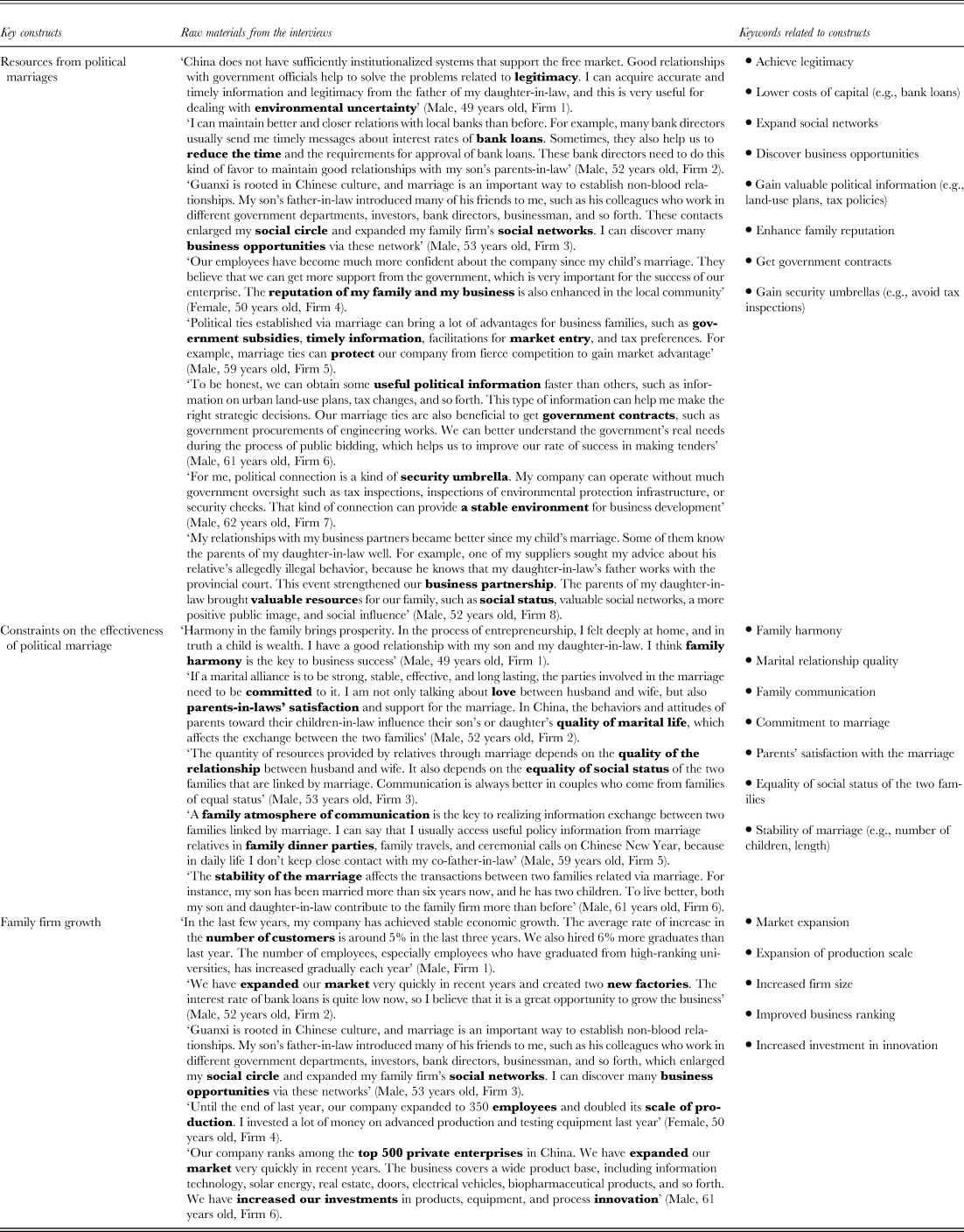

Coding Process

According to the principles of grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967; Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1990), we read and reread the textual data collected from the interviews, labeling the key constructs (key resources from political marriage, key constraints of political marriage, and family firm growth). Following grounded theory with regards to qualitative studies (Glaser, Reference Glaser1978), we used open coding to classify the data collected from the interviews. Following the two-step method suggested by Mayring (Reference Mayring2014), we first used sentence-by-sentence coding. Then we logically structured the descriptions of each of the eight family business owners into categories of relevant information about political marriage, valuable resources, and family firm growth. Two independent coders read and coded the interview transcripts’ statements regarding political marriage and family firm growth. Table 6 describes the key constructs and gives examples of our open coding.

Table 6. Mediating processes between political marriage and family firm growth

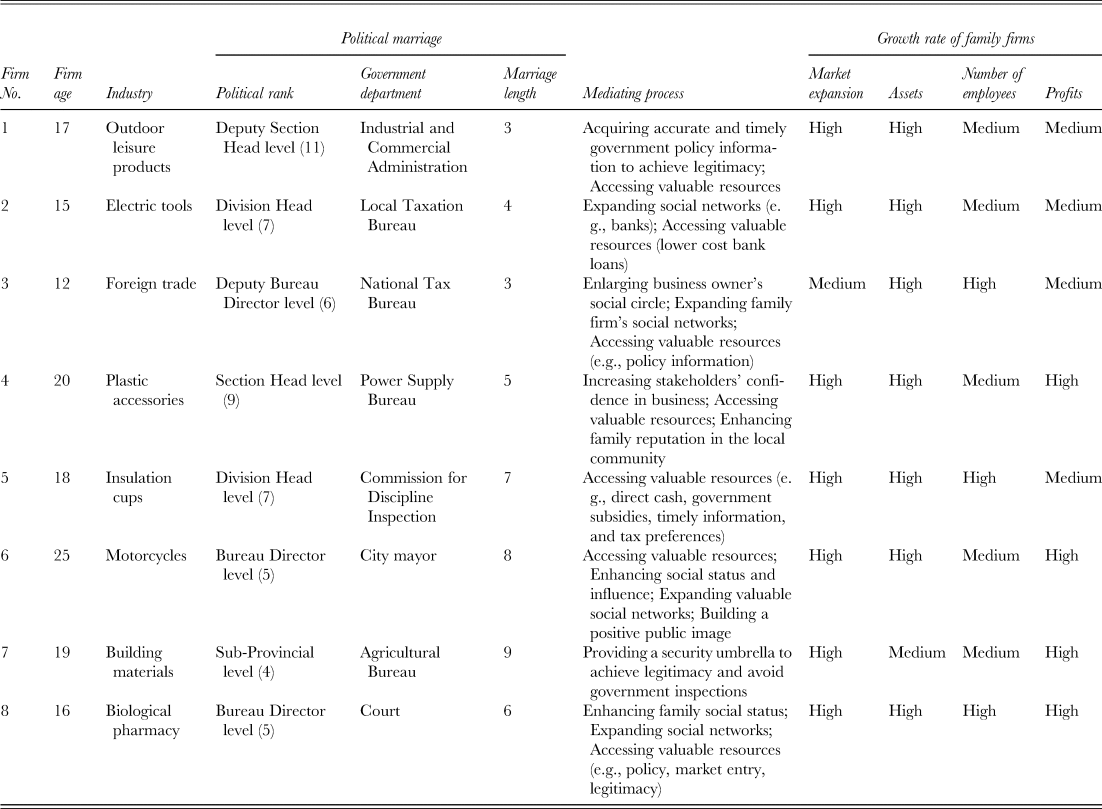

In the second step, we performed a cross-interview analysis to better understand how political marriage was associated with each family firm's growth. We first hand-coded the interviews with respect to key variables in the research model. Then, we classified the information into different categories of political marriages, based on the different political ranks and departments involved. Next, we further categorized and identified the significant mechanisms that linked political marriage and family firms’ rates of growth (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). According to the results of Table 5, several key measurements of firm's rate of growth can be identified including market expansion and the growth rate of assets, the number of employees, and profit. For instance, Mr. Hu, 52 years old, a CEO of an electric tools manufacturer, suggested political marriage enabled him to build good relationships with bank directors and contribute to his firm's market expansion. Compared with the measurements of dependent variable in Study 1, we added two additional measurements of firm's growth rate (profit and market expansion) based on the results of qualitative analysis. We suggest that market expansion indicates added firm's value due to growth opportunities (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994), which is an appropriate measurement of a firm's growth (e.g., Mishina, Pollock, & Porac, Reference Mishina, Pollock and Porac2004). Using four indicators to measure firm's growth in Study 2 compensates for the limitation of measurement of the outcome variable in Study 1 because multiple indicators of growth provide richer information than single indicators (Davidsson, Delmar, & Wiklund, Reference Davidsson, Delmar and Wiklund2006).

Results for Study 2

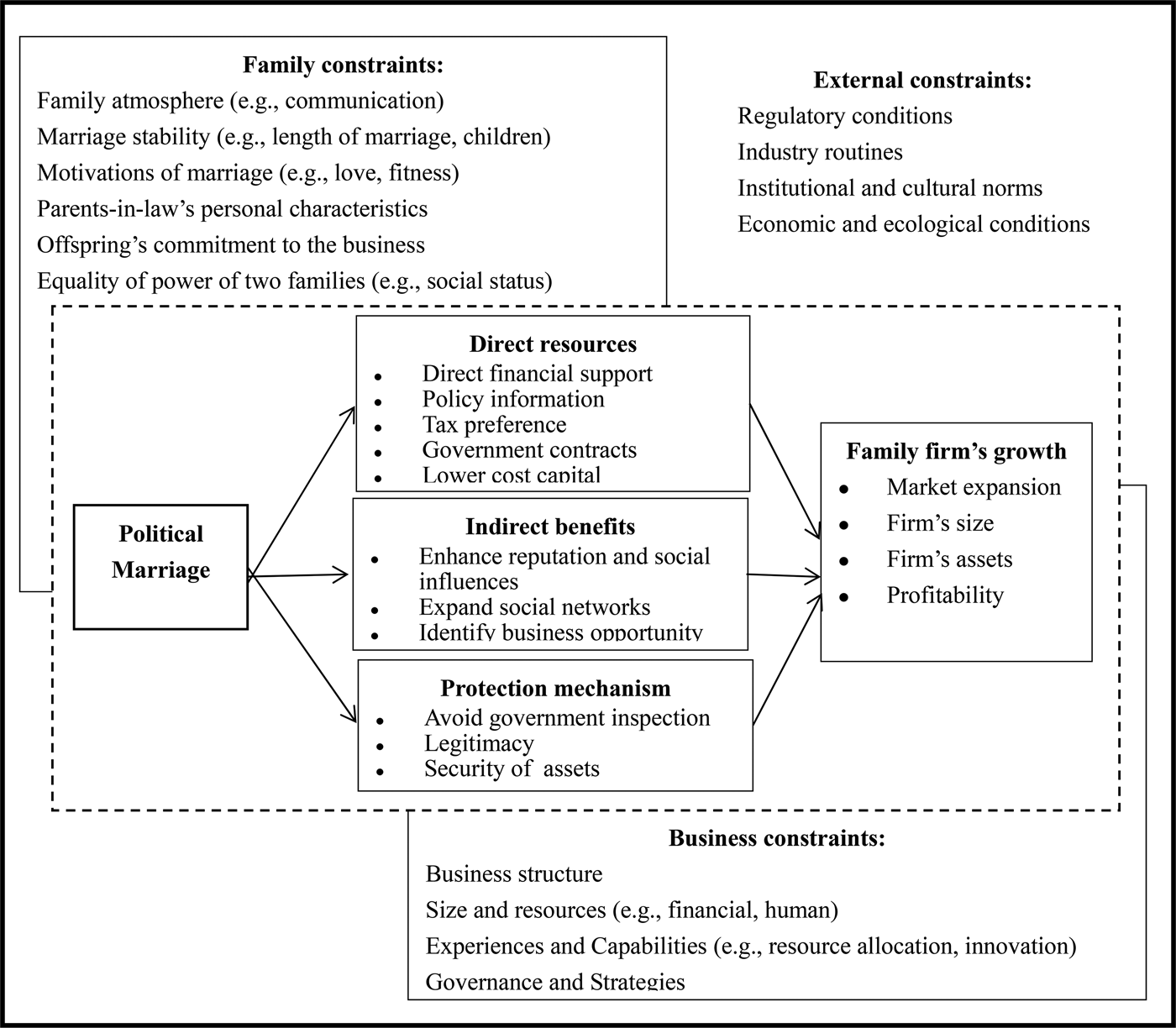

The main purpose of Study 2 was to investigate how political marriages contribute to or constrain the growth of family firms. Table 5 provides an overview of the benefits of political marriages between family firm members and officials of different political rankings, along with the ratings given by family business owners on the four aspects of family firm growth (e.g., market expansion, rates of growth in assets, the number of employees, and profits). According to the results of the interviews, seven of the eight respondents believed that political marriages contributed to their family firms’ growth in assets and market expansion. According to patterns identified in our analysis, we suggest that three main processes mediated the relationship between political marriage and family firm growth, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Political marriage research model in family business

Our first observation is that political marriage provides direct access to valuable resources. Most of the respondents suggested that the marriage partners whose parents worked for the government were able to share timely information on public policy (e.g., government land-use plans, preferential tax policies, government subsidies) with their spouses’ family firm members via family parties, family trips, and other household activities. Respondents indicated such shared information helped to guide them in formulating strategies to promote the development of their enterprises. For instance, Mr. Wu, a 61-year-old founder of an electromobile company, stated the following:

To be honest, via communication with the father of my daughter-in-law, I can obtain some useful political information faster than others on things such as urban land-use plans, tax changes, and so forth, and this type of information can help me make the right strategic decisions. It also benefits us through helping us to get government contracts, such as government procurements of engineering works. We can better understand the government's real needs during the process of public bidding, which helps us to improve our rate of success in tenders. … Our company also obtained a local government subsidy for our electric car program, and it greatly lowered the cost of innovation.

Mr. Wang, a 52-year-old founder of a biopharmaceutical company, explained the following:

Considering the unique characteristics of the pharmaceutical industry, I need to follow the policies of relevant government departments all the time. Our company's development is largely influenced by government support. My relatives through my son's marriage often share information with me about government support policies on developing high-quality biomedical products. Our company won a government award of about RMB2 million due to our contribution to innovation in preparing Chinese medicine.

In our sample, all respondents indicated that political marriages brought various forms of valuable political resources, which contributed to their family firms’ growth. These qualitative results also further supported our arguments that we developed in Study 1 for testing Hypothesis 1.

In addition to the direct benefits, we found that political marriages could bring various indirect benefits for both families and businesses, such as expanded social networks, improved family social status, enhanced family reputation and social influence, and increased stakeholder confidence in the family firms (see Figure 3). We observed that family business owners’ social circles could be enlarged by establishing political marriages. For example, as Mr. Zhao, a founder of a foreign trade company, suggested:

My son's father-in-law introduced many of his friends to me, such as his colleagues who work in different departments of the government, investors, bank directors, businessman, and so forth. These contacts enlarged my social circle and expanded our family firm's social networks. I found some good suppliers for my company via these networks. I could also discover many business opportunities via these networks.

Furthermore, some respondents noticed an upgrade in social status since forming political marriages. For instance, an owner of a plastic accessories manufacturing company said ‘Our employees became much more confident about the company since my child's marriage. They believed that we could get more support from the government, which is very important for an enterprise's success. The reputation of my family and business has also been enhanced in the local community’. Another respondent provided a similar argument: ‘My relationships with business partners became better since my child's marriage. … Some of them know the parents of my daughter-in-law well’.

Another important finding from Study 2 was related to the protection mechanisms by which political marriages enabled family firm growth. For instance, Mr. Huang, an owner of a building materials company, suggested ‘To me, political connection is a kind of security umbrella. My company could operate without much government scrutiny in matters such as tax inspection, inspection of environmental protection infrastructure, security checks, and so forth. The connection could provide a stable environment for business development’. These results indicate that protection mechanisms served as a salient factor underlying the effects political marriage had on family firms’ growth.

In total, we explored three types of explanatory mechanisms that underlie the positive effects of political marriage on family firm growth. These mechanisms included direct access to valuable resources (e.g., lower cost bank loans, government subsidies, and contracts), indirect benefits (e.g., enhanced reputation and social status, expanded social networks), and protection mechanisms (e.g., avoidance of government inspections, enhanced legitimacy, security of assets) (see Figure 3).

Furthermore, the findings from interviews confirmed the important moderating role of romantic love. Several respondents mentioned their children's perceptions of love in political marriage affected their behaviors and attitudes toward exchanges of political resources between their two families. For example, a business owner said that

My son loves my daughter-in-law very much. They met at an alumni gathering. They graduated from the same university in London. He didn't know his wife's family background in their early dating. He refused several times when I asked him to seek help from his father-in-law. He believes that marriage is not a financial deal. He does not want his wife and her family to view his love and dignity as valueless.

Another respondent also explained:

My son and his partner united in marriage only because of their love for each other. My son chose his partner on his own, and I respect his choice. He never thought to use his marriage to gain some benefits for our business, because he has an unwritten rule to avoid talking about work with his partner at home. He believes that family is the place to find love rather than a job.

These statements further demonstrate that romantic love moderates the effects of political marriage on a family firm's growth. In addition to romantic love, respondents mentioned a number of other contextual factors that influence the effects of political marriage, which are summarized in Figure 3. These factors include macro-environmental conditions (e.g., industrial routines, economic and ecological conditions, cultural norms, and regulatory conditions), family-related factors (e.g., family structure, marriage stability, motivations of marriage, equality of power between two-related families), and business-related factors (e.g., business structure, resources, experience, capability, governance, and strategy).

Discussion of Study 2

The results of Study 2 further supported Hypothesis 1, which posits that political marriage has positive effects on a family firm's growth. Political marriage can bring both direct and indirect resources for a business, and it can serve as a protective umbrella to shape a stable environment for a family firm's growth. Our findings are consistent with literature on political ties, showing that the direct acquisition of valuable resources (e.g., policy information, direct financial support, government contract) is an important mediator of the link between family ties and business performance (Wang, Jiang, Yuan, & Yi, Reference Wang, Jiang, Yuan and Yi2013). Furthermore, our findings showed that indirect benefits obtained via political marriage (e.g., enhancement of family business reputation, expansion of social networks, and identification of new business opportunities) contribute to a firm's growth, consistent with our findings that recognition of entrepreneurial opportunity mediates the relationship between political ties and a firm's financial performance. In addition, our findings enrich literature on the mechanisms by which social ties affect economic performance, by suggesting political marriages help family firms to avoid government inspection, achieve legitimacy, and secure their assets – all of which are in turn conducive to a firm's growth.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Our study aimed to provide a clearer understanding of the under-investigated political connections that are established via marriages of the offspring of family business owners, and effects of these marriages on firm growth. The results of our two studies show that political marriage creates an enduring form of political capital, which is positively related to the growth of family firms.

In Study 1, we examined the moderating role of the length of a marital relationship. We found that the positive effect of political marriage on firm growth is stronger when the duration of the marriage is longer. Although ‘capital’ is essentially an economic concept, social capital theory incorporates social factors into econometric models to include the intrinsic characteristics of instrumentality. Previous studies have found that corporate political ties have instrumental functions in gaining valuable information and benefits. However, unlike purely instrumental political relationships, the function of political marriages involves the irrational and noninstrumental factor of romance in marital relationships. Thus, by integrating social capital theory and self-verification theory, we found that the positive effects of political marriage on firm growth were stronger when the marriages were longer and when the levels of romantic love were lower. The results of Study 2 confirmed the results of Study 1. This study identified three pathways of influence (i.e., direct resources, indirect benefits, and protection mechanisms) that underlie the links between political marriage and family firm growth.

Theoretical Contributions and Managerial Implications

The findings of this study have several theoretical implications. First, our findings clarify conditions under which political marriage is most positively associated with the growth of family firms. Although extensive empirical studies have focused on political ties as causal antecedents that promote firm growth (e.g., Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000), we show that some types of political ties contribute more to firm growth than others (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Stam & Elfring, Reference Stam and Elfring2008). Political marriage involves an enduring, loyal, and cohesive relationship between two families (one of them involved in business and the other in politics). This kind of relationship is relatively stable, so it can effectively facilitate the exchange of economic benefits.

Literature on political ties also suggests opportunistic behaviors of politicians tend to occur when they are much more powerful than their contracting parties in the business (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012). The patron/client system is defined as a mutual arrangement between a person that has authority, social status, wealth, or some other personal resource (patron), and another who benefits from their support or influence (client). However, political marriage in our study is not a simple patron–client relationship that can be easily explained by the mechanics of clientelism. Political marriage is different from political ties that only involves with instrumental benefits exchange, it bonded political and business families via a long-term contract. In other words, political marriage internalizes political ties as a strong and reliable family relationship (e.g., Bunkanwanicha et al., Reference Bunkanwanicha, Fan and Wiwattanakantang2013). Marriage creates a trustworthy relationship between the couple and their related families (Becker Landes, & Michael Reference Becker, Landes and Michael1977). The relationship between political and business families boned via children's marriage goes beyond patron–client relations. Therefore, arguments toward patron–client relationship may not be applicable to our study.

Political marriage produces a strong family tie between a family firm and a government authority based on a lifelong marital contract (Becker, Reference Becker1973; Becker & Becker, Reference Becker and Becker2009). The uniqueness of family ties reduces the possibility that political patron acquiring resources from family business instrumentally and unilaterally via political marriage. Because family relationships are characterized by higher levels of trust, empathy, and reciprocity, which do not exist in relationships established for purely instrumental reasons (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985). Marriage is considered as an especially powerful way of binding patron and client (e.g., government officials and family business owners) together because it produces children who have relatives in both camps (Coontz, Reference Coontz2006). Relational trust developed via political marriage is one of the most effective means to mitigate political hazards caused by status and power gap between patron and clients (Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012). Therefore, we suggest the unique characteristics of family ties embodied in political marriage enable families to reduce agency cost in resource exchange between patrons and family business owners. We are not saying that family business enjoys substantial agency, but ‘grabbing hand’ risks of government officials is largely reduced in political marriage. By distinguishing between traditional corporate political ties and political marriage (which is based on the dual characteristics of political and family ties), our study contributes to the literature on the heterogeneity of political ties (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi, Wright and Xu2015).

Based on the analysis of our qualitative data, we uncover three fundamental mediating mechanisms that can translate political marriage into growth for a firm: direct resources, indirect benefits, and protective umbrellas. This identification of mechanisms enriches the social network literature. Some studies have examined a number of mediating mechanisms through which social ties can lead to improved economic performance, such as resource acquisition, institutional support, and partner opportunism (e.g., Zhu, Su, & Shou , Reference Zhu, Su and Shou2017). However, this process-based approach is used relatively less than the contingency-based approach in the literature on political ties (e.g., Guo, Xu, & Jacobs, Reference Guo, Xu and Jacobs2014), and previous studies have failed to consider the protection mechanism of political ties. We present evidence that the protective umbrella established via political marriage helps firms to avoid government inspection and to create stable environments for their business to grow. Therefore, our study offers new insight that opens the black box regarding the intriguing relationship between political ties and firm performance (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Xu and Jacobs2014).

Our findings also add to the literature on family ties by exploring contingencies involved in the effective use of family ties. This study shows that a longer duration for a political marriage fosters the positive effects of family ties on firm growth, but romantic love weakens the instrumental function of political marriages. A core assumption of the family business literature is that family ties have a positive effect, because they foster family-centered noneconomic goals and increased trust among family members (Mani & Durand, Reference Mani and Durand2019). Our study expands this explanation by considering the potential negative effects of romantic relationships embedded in political marriages (e.g., Hsueh & Gomez-Solorzano, Reference Hsueh and Gomez-Solorzano2019; Verver & Koning, Reference Verver and Koning2018). This investigation contributes to research on the heterogeneity of family ties. Our findings show that compared with blood ties, the family ties established via marriage contracts may involve a higher emotional cost. To validate their role as ‘romantic lovers’, the children of business owners in political marriages tend to deliberately distance themselves from social activities that facilitate business transactions. Although we emphasize the instrumental functional role that family ties play in offering political resources to business families, we also reveal that the family ties (e.g., romantic marital relationships) in an entrepreneur's social network may have negative effects on a firm's capacity to access political resources (Arregle, Batjargal, Hitt, Webb, Miller, & Tsui, Reference Arregle, Batjargal, Hitt, Webb, Miller and Tsui2015).

In addition, rather than emphasizing the categorical or quantitative aspects of social ties, we suggest the effect of social capital is constrained by the quality and nature of social ties. These qualitative factors include the length of a relationship and the level of romantic love. Some sociologists have conceptualized the importance of relational embeddedness, or the extent to which economic outcomes are affected by the quality of an actor's personal ties (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter2005), as such ties are a key dimension of social capital. However, the process by which the quality of social ties is shaped remains unclear. The differences in relational content, such as variations in the strength of ties (Marsden & Campbell, Reference Marsden and Campbell1984) and the levels of relational trust (Moran, Reference Moran2005; Tsai & Ghoshal, Reference Tsai and Ghoshal1998), have mainly been examined from an instrumental perspective. However, political marriage is a complex social phenomenon that possesses the characteristics of both instrumentality in strategic alliances and romance in marital relationships. This duality of purpose limits the ability of social capital theory to explain the effectiveness of political marriage. By integrating economic and emotional perspectives, we are able to examine the unique boundary conditions of political marriage. We consider both the economic feature of increased benefits according to the length of a marital relationship and the emotional feature of romantic love in a marital relationship. Our findings suggest that the efficiency of social capital is enhanced or constrained by the quality and nature of social relationships (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Pennings2001).

FUTURE AGENDA AND CONCLUSION

Our study has several limitations and opens new avenues for future research. Collecting more data about the different political backgrounds of government officials could more effectively inform our measures of political marriage. One concern regarding the causal effect of political marriage is that some unobserved or omitted variables (e.g., relative power and status of the politician and business owner) may correlate with both political marriage and firm's growth. This positive association may also be driven by reverse causality, where politicians are more likely to seek ties with wealthy business families (e.g., family firms with high growth rates) to advance their economic interests. Previous research also shows that wealthy business owners are more likely to be the attractive targets for government officials to exchange interests privately (Hunt & Laszlo, Reference Hunt and Laszlo2012). Although results of our qualitative study provide initial evidence supporting the causal direction from political marriage to firm growth, the cross-sectional research design prevents us from examining a temporal relationship between predictors and outcomes. Without longitudinal data, it is difficult to establish a causal link between political marriage and firm's growth (Carlson & Morrison, Reference Carlson and Morrison2009). Therefore, we call for further research to address the potential issue of reversal causality by using longitudinal data. Additionally, system GMM technique (Arellano & Bover, Reference Arellano and Bover1995; Blundell & Bond, Reference Blundell and Bond1998) is recommended to tackle endogeneity problems. Furthermore, future studies can conduct a natural experiment using panel data and apply a difference-in-difference (DID) technique to test the casual relationship between political marriage and family firm's growth to mitigate the effects of extraneous factors and sample selection bias (Chabé-Ferret, Reference Chabé-Ferret2015). More specifically, a DID technique enables researchers to compare the differences of family firm's growth before and after political marriage.

As our study also suffers from within population, contextual, and temporal generalization problems (Tsang & Williams, Reference Tsang and Williams2012), we offer several directions for future research to address these issues. First, although our research model controlled for the effects of political power (e.g., Zheng, Singh, & Mitchell, Reference Zheng, Singh and Mitchell2015), we did not consider that government officials from different departments (e.g., environment, justice, trade and industry, or tax departments) may differ in their levels of political power to allocate different types of resources. Collecting more data from government officials with different political backgrounds will help capture the within population diversity. Thus, we encourage future researchers to theorize and examine the consequences of political marriage in diverse political contexts. Second, given the world-wide phenomena of political marriage, we suggest future studies collecting data across different settings (e.g., both eastern and western countries) to enhance the contextual generalizability of our model (Lucas, Reference Lucas2003). Different socio-cultural contexts could influence the effects of political marriage on firm growth. For example, the Chinese government still controls a large proportion of available scarce resources such as land, bank loans, financial assistance, and tax breaks (Faccio, Reference Faccio2006; Khwaja & Mian, Reference Khwaja and Mian2005), so managing business–government relationships have become essential components of the core strategies of private firms in China (e.g., Bai, Lu, & Tao, Reference Bai, Lu and Tao2006; Cull & Xu, Reference Cull and Xu2005). Therefore, we strongly encourage future researchers to test the effects of political marriage in different countries, particularly in the West, to enhance the applicability of our theories to other national contexts (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1993). Finally, our study can also be extended by using a longitudinal design, not only to address the issue of political marriage as discussed in this study but also to observe the process through which political marriages accumulate political capital for family firms over time. Cronbach (Reference Cronbach1975) argues that generalizations in the social sciences decay fast over time due to the lack of analysis on temporariness. Further insights can be generated in the future through longitudinal studies that trace the evolution of how family firms acquire benefits and grow via political marriage and observe the dynamic benefit exchange process between two-related parties. Such research can deepen our knowledge of how political capital embedded in family networks changes over time.

Furthermore, like many other studies on networks (e.g., McEvily, Jaffee, & Tortoriello, Reference McEvily, Jaffee and Tortoriello2012), our data only consist of marital relationships between children of the business and politicians’ families without investigating the roles of multiplex relationships. Although we believe that political marriage is directly relevant to the mechanisms and outcomes in our study, we cannot rule out the possibility that other types of family ties (e.g., relationship between parents and children) also matter. Although our findings suggest that family firms’ growth is well explained by political marriage and its unique characteristics of length and romantic love, other factors related to family ties remain unexplored. For instance, relationship quality between family business owners and their children (e.g., Lee, Zhao, & Lu, Reference Lee, Zhao and Lu2019), offspring’ s self-esteem and identification with the firm (Craig, Dibbrell, & Davis, Reference Craig, Dibbrell and Davis2008; Zellweger, Eddleston, & Kellermanns, Reference Zellweger, Eddleston and Kellermanns2010), and the degrees of family harmony (Graves & Thomas, Reference Graves and Thomas2008) affects family members’ motivation to access resources via political marriage and thus in turn determines the growth pathways of family firms. As such, it would be interesting to explore how different types and characteristics of family ties affect a firm's growth.

This study draws on social capital and self-verification theories to develop new insights into the effects of political marriage on firm growth. Our findings indicate a complex contingency model, in which the positive effects of political marriage are particularly pronounced if the duration of the marriage is long, and the level of romantic love is low. Thus, this study expands our knowledge of the effects of political marriage in the family business context and enriches our knowledge of the features of kinship-based political capital. More generally, our focus emphasizes the need for a detailed inquiry into the heterogeneity of political connections and the effects that noninstrumental relational characteristics such as romantic love can have on the quality of social capital.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework (OFS) at https://osf.io/8fd6t/

APPENDIX I Measurements of key constructs