Introduction

Lichenized Basidiomycota make up less than one percent of all lichenized Fungi in terms of species number, but play an important role in ecosystems and habitats such as tropical alpine regions, conserved forests, and roadbanks (Petersen Reference Petersen1967; Oberwinkler Reference Oberwinkler1970, Reference Oberwinkler1984, Reference Oberwinkler and Hock2012; Gómez Reference Gómez1972; Parmasto Reference Parmasto1978; Lutzoni & Vilgalys Reference Lutzoni and Vilgalys1995; Redhead et al. Reference Redhead, Lutzoni, Moncalvo and Vilgalys2002; Lawrey et al. Reference Lawrey, Binder, Diederich, Molina, Sikaroodi and Ertz2007, Reference Lawrey, Lücking, Sipman, Chaves, Redhead, Bungartz, Sikaroodi and Gillevet2009; Ertz et al. Reference Ertz, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Gillevet, Fischer, Killmann and Sérusiaux2008; Yánez et al. Reference Yánez, Dal-Forno, Bungartz, Lücking and Lawrey2012). The largest lichenized clade within the Basidiomycota is Dictyonema s. lat., with c. 50 species (Chaves et al. Reference Chaves, Lücking, Sipman, Umaña and Navarro2004; Lawrey et al. Reference Lawrey, Lücking, Sipman, Chaves, Redhead, Bungartz, Sikaroodi and Gillevet2009; Dal-Forno et al. Reference Dal-Forno, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Bhattarai, Gillevet, Sulzbacher and Lücking2013). The genus is largely tropical and only a few species of Dictyonema extend into subtropical and temperate regions, one being D. interruptum, which is known from the British Isles, western Europe, and the Canary Islands and Azores (Parmasto Reference Parmasto1978; Coppins & James Reference Coppins and James1979; Etayo et al. Reference Etayo, Diederich and Sérusiaux1995; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Aptroot, Coppins, Fletcher, Gilbert, James and Wolseley2009).

Apart from its extratropical distribution, Dictyonema interruptum is notable for the nomenclatural problems associated with its name. The taxon was first described in the cyanobacterial genus Calothrix, as C. interrupta Carmich. ex Hook. (Smith Reference Smith1833), and then subsequently transferred to the cyanobacterial genera Rhizonema (Smith & Sowerby Reference Smith and Sowerby1849), Stigonema (Hassall Reference Hassall1852), and Scytonema (Cooke Reference Cooke1882). The species was considered to be a non-lichenized cyanobacterium until Bornet (Reference Bornet1873), Hariot (Reference Hariot1891), and Zahlbruckner (Reference Zahlbruckner1931) placed it into synonymy with Dictyonema sericeum. This was based on a drawing first published by Thwaites (Smith & Sowerby Reference Smith and Sowerby1849; see also Cooke Reference Cooke1882; Parmasto Reference Parmasto1978), which shows the jigsaw-shaped hyphal sheath cells around the cyanobacterial filaments characteristic of Dictyonema (Parmasto Reference Parmasto1978; Chaves et al. Reference Chaves, Lücking, Sipman, Umaña and Navarro2004). Parmasto (Reference Parmasto1978) considered the material to represent a separate species of Dictyonema and proposed (ad int.) the combination of the epithet interruptum into that genus. Parmasto himself had seen only Thwaites's drawing and not actual specimens, but Coppins & James (Reference Coppins and James1979) provided a detailed account of Carmichal's original material and other collections made later, and the name Dictyonema interruptum has been applied to this taxon ever since.

Recently, it was discovered that the photobiont of Dictyonema and other cyanobacterial lichens, such as Coccocarpia, does not belong to the genus Scytonema but represents a separate lineage different from Scytonemataceae (Lücking et al. Reference Lücking, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Gillevet, Chaves, Sipman and Bungartz2009; Büdel & Kauff Reference Büdel, Kauff and Frey2012). Since Calothrix interrupta appeared to represent the first name for a cyanobacterial species described in this lineage, and a new genus, Rhizonema, had been proposed for it by Thwaites (Smith & Sowerby Reference Smith and Sowerby1849), Lücking et al. (Reference Lücking, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Gillevet, Chaves, Sipman and Bungartz2009) took up the name Rhizonema for the novel cyanobacterial lineage. However, under the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi and Plants (ICN; McNeill et al. Reference McNeill, Barrie, Buck, Demoulin, Greuter, Hawksworth, Herendeen, Knapp, Marhold and Prado2012), the starting date for heterocystous bacterial nomenclature is 1 January 1886 (ICN Art. 13.1.e), following Bornet & Flahault (Reference Bornet and Flahault1886). Therefore, the name Rhizonema, published in 1849 and never formally redescribed, is not validly published. Also, Calothrix was not validly published until 1886, and hence the name C. interrupta is invalid and no combination based on this name, in any genus, is validly published.

One might argue that the nomenclatural starting point that determines validity of the name Calothrix interrupta is 1 May 1753 (ICN Art. 13.1.d), since the original material is lichenized and ICN Art. 13.1.d states: “For nomenclatural purposes names given to lichens apply to their fungal component.” This view could be defended considering that the lichen symbiosis had not been discovered at the time of the description of Calothrix interrupta and hence the name would apply to the (lichenized) entity, with ICN Art. 13.2. coming into play: “The group to which a name is assigned for the purposes of this Article is determined by the accepted taxonomic position of the type of the name.” However, such considerations are irrelevant since the material was described in Calothrix, and the accepted taxonomic position of Calothrix is in the cyanobacteria, fixing the starting date of any name described in this genus to 1 January 1886.

This paper remedies the current situation by providing validly published names for both the lichenized fungus and its photobiont. The genus Rhizonema and the type species, R. interruptum, are formally described, as well as the containing family, Rhizonemataceae. While we retain the epithet interruptum for the photobiont, we abandon it for the lichen fungus, instead naming the latter Dictyonema coppinsii, in honour of Coppins's jubilee and his many outstanding contributions to lichenology.

Dictyonema coppinsii Lücking, Barrie & Genney sp. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB803241

Differing from Dictyonema schenkianum in the presence of clamp connections and its extratropical, western European distribution.

Type: Ireland, County Kerry, Killarney, Turk Cascade, on mosses and lichens, 1832, Harvey s. n. (E—holotype; BM—isotype).

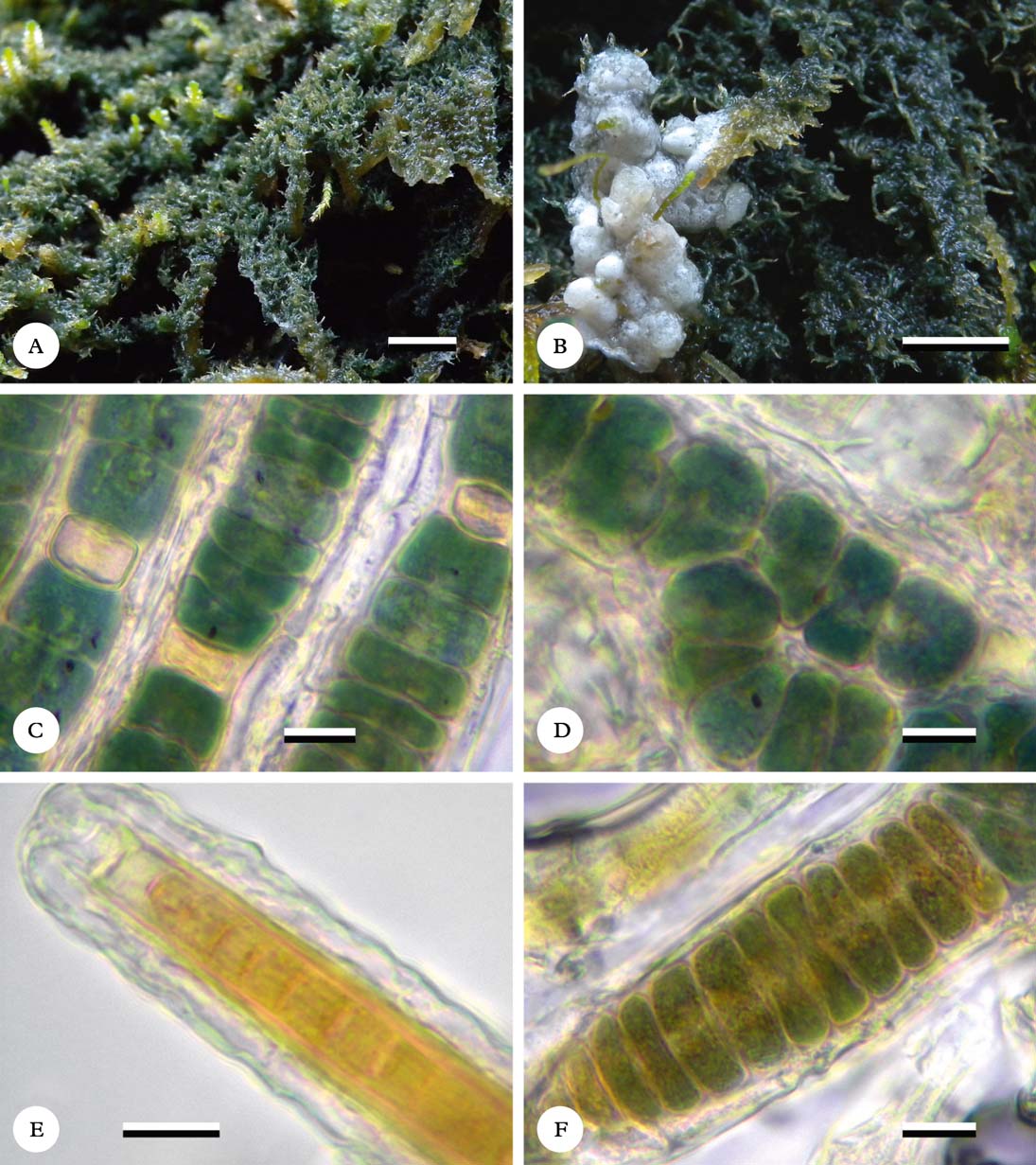

Fig. 1. Dictyonema coppinsii; A & B, habit showing appressed filamentous thallus and hymenophores (Corrieshalloch Gorge National Nature Reserve). Rhizonema sp., (C–F), microscope images of lichenized trichomes of from the lichenized fungus Dictyonema schenkianum (Brazil, Lücking 30062, F), C, showing trichomes with heterocytes; D, true branching; E, terminal; F, development of hormogonium. Scales: A & B=1 mm; C–F=10 µm. A & B field images photographed by David Genney.

Thallus appressed filamentous, bluish green, loosely encrusting the substratum; filaments irregularly interwoven, suberect to erect, up to 5 mm above the substratum. Marginal prothallus absent or indistinct. Photobiont a species of Rhizonema; individual cells 15–20 µm wide and 5–10 µm high, blue-green; heterocytes sparse, yellow. Filaments surrounded by a closed hyphal sheath formed by jigsaw-puzzle-shaped, hyaline cells. Free (generative) hyphae hyaline, branched and sometimes anastomosing, 4–6 µm wide, rather thick walled (wall to 1 µm thick).

Basidiomata rare, emerging from the underside of the filaments but becoming fully exposed, irregularly corticioid and bumpy, white. Hymenium composed of a compact layer of pallisadic basidioles with scattered basidia; basidioles cylindrical, 10–20×5–8 µm; basidia cylindrical, 10–20×5–7 µm, 4-spored, with curved, about 2 µm long sterigmata; basidiospores drop-shaped, 6–8×3–4 µm. Subhymenial hyphae vertical, branched, 5–7 µm wide. Clamp connections present but rare in generative and subhymenial hyphae.

Etymology

It is with great pleasure that we dedicate this new lichen to our esteemed colleague Brian Coppins, for his invaluable contributions to lichenology, particularly in the British Isles.

Ecology and distribution

On mossy soil or rocks or epiphytic, often overgrowing bryophytes. The species appears to be restricted to natural forest remnants in oceanic western Europe and has been reported from the British Isles, the Pyrenees, the Azores, and Madeira (Parmasto Reference Parmasto1978; Coppins & James Reference Coppins and James1979; Hafellner Reference Hafellner1995; Rodrigues & Aptroot Reference Rodrigues, Aptroot, Borges, Cunha, Gabriel, Martins, Silva and Vieira2005; Lawrey et al. Reference Lawrey, Lücking, Sipman, Chaves, Redhead, Bungartz, Sikaroodi and Gillevet2009).

Notes

Dictyonema coppinsii belongs to a diverse group of appressed filamentous species with a jigsaw-puzzle-shaped hyphal sheath. These species were considered forms of D. sericeum by Parmasto (Reference Parmasto1978), lacking any taxonomic value, but morphological and molecular phylogenetic studies showed that they are not only specifically different but represent a large number of separate species (Chaves et al. Reference Chaves, Lücking, Sipman, Umaña and Navarro2004; Lawrey et al. Reference Lawrey, Lücking, Sipman, Chaves, Redhead, Bungartz, Sikaroodi and Gillevet2009; Yánez et al. Reference Yánez, Dal-Forno, Bungartz, Lücking and Lawrey2012; Dal-Forno et al. Reference Dal-Forno, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Bhattarai, Gillevet, Sulzbacher and Lücking2013). Dictyonema coppinsii is morphologically most similar to the tropical D. schenkianum (Müll. Arg.) Zahlbr. (Chaves et al. Reference Chaves, Lücking, Sipman, Umaña and Navarro2004; Yánez et al. Reference Yánez, Dal-Forno, Bungartz, Lücking and Lawrey2012) and differs chiefly in the presence of (scattered) clamp connections. Based on nuLSU, ITS, and RPB2 sequence data from a specimen from Madeira (Ertz 10475; Lawrey et al. Reference Lawrey, Lücking, Sipman, Chaves, Redhead, Bungartz, Sikaroodi and Gillevet2009; Dal-Forno et al. Reference Dal-Forno, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Bhattarai, Gillevet, Sulzbacher and Lücking2013), the species is indeed closely related to D. schenkianum s. lat., which itself is a collective taxon with several distinct, species-level lineages (Lawrey et al. Reference Lawrey, Lücking, Sipman, Chaves, Redhead, Bungartz, Sikaroodi and Gillevet2009; Dal-Forno et al. Reference Dal-Forno, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Bhattarai, Gillevet, Sulzbacher and Lücking2013).

Additional specimens examined (paratypes). Great Britain: Scotland: V.C. 105, Ross and Cromarty: Corrieshalloch Gorge National Nature Reserve, along Droma River 20 km S of Ullapool, between the A832 and A835 roads near Braemore, Scottish Highlands, 2011, Douglass s. n. (F, hb. Douglass).—Portugal: Azores: Terceira, Serra de Santa Barbara, 38°44′N, 27°19′W, 930 m, vii 2008, Aptroot & Schumm s. n. (hb. Schumm 14158). Madeira: Ribeiro Frio, Ertz 10475 (BR, GMUF).

Rhizonemataceae Büdel & Kauff ex Lücking & Barrie fam. nov.

Differing from Scytonemataceae in the formation of true branching of the T type; from Microchaetaceae and Rivulariaceae in the isopolar trichomes with true branching and lacking terminal hairs, from Nostocaceae in the lack of distinct constrictions between cells, from Fischerellaceae and Stigonemataceae in the always uniseriate trichomes, and from Hapalosiphonaceae in the short, broad cells lacking distinct constrictions.

Type (and only genus): Rhizonema Lücking & Barrie.

Lichenized with Asco- or Basidiomycota (e.g. Acantholichen, Coccocarpia, Cora, Corella, Cyphellostereum, Dictyonema). Filamentous or broken into irregular clusters of rounded cells when lichenized with Acantholichen, Coccocarpia, Cora or Corella. Trichomes (observed when lichenized with Cyphellostereum and Dictyonema) isopolar, uniseriate, cylindrical, formed by rectangular cells with blue-green to olive-green pigmentation embedded in a thin, dense, gelatinous, hyaline or brownish sheath; terminal cells smaller and often yellow rather than blue-green but not rounded or hair-like. Branching rare, representing true branching of T or akin towards V type, with the division plane periclinal or slightly oblique. Heterocytes frequent, intercalar. Asexual reproduction rare, by hormogonia and akinetes.

Notes

This family was introduced as a nomen nudum by Büdel & Kauff (Reference Büdel, Kauff and Frey2012), who recognized the taxonomic distinctiveness of this group; the name is validated here. Thus far it only includes the type genus, Rhizonema. It appears to have a unique combination of morphological characters not found in other families of Nostocales: the trichomes are isopolar and uniseriate as in Hapalosiphonaceae, Nostocaceae, and Scytonemataceae, but differ from the latter in the formation of true branches, mostly of the T type (Büdel & Kauff Reference Büdel, Kauff and Frey2012). Hapalosiphonaceae and Nostocaceae, which are both related to Rhizonemataceae (Lücking et al. Reference Lücking, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Gillevet, Chaves, Sipman and Bungartz2009), have rounded to elongate cells with often distinct constrictions, whereas Rhizonemataceae have short, broad cells with slight constrictions, resembling a ‘vertebral column’, more similar to Scytonemataceae. A particular feature of Rhizonemataceae appears to be the change in pigmentation towards more exposed portions of the trichome or cells. While shaded portions or cells are deeply blue-green to olive-green, exposed portions or cells may become yellow-green to yellow-orange. In addition, in some species of Rhizonema, the gelatinous sheath can be brownish, whereas the colour of the cells remains blue-green. The yellow to brown pigments possibly capture damaging UV radiation levels and transform them into visible light energy that can be used by the photosynthetic pigments. Attempts are in progress to obtain cultures from several species of Rhizonema in order to describe their features in the non-lichenized stage (B. Büdel, pers. comm. 2012).

Rhizonema Lücking & Barrie gen. nov.

Differing from Scytonema in the formation of true branching of the T type and the possibly exclusively lichenized biological lifestyle.

Type: Rhizonema interruptum Lücking & Barrie.

Filamentous or broken into irregular clusters of rounded cells. Trichomes isopolar, uniseriate, cylindrical, formed by rectangular cells with blue-green to olive-green pigmentation embedded in a thin, dense, gelatinous, hyaline or brownish sheath (Fig. 1C); terminal cells smaller and often yellow rather than blue-green but not rounded or hair-like (Fig. 1E). Branching rare, representing true branching of T or akin towards V type, with the division plane periclinal or slightly oblique (Fig. 1D). Heterocytes frequent, intercalar (Fig. 1C). Asexual reproduction rare, by hormogonia (Fig. 1F) and akinetes.

Notes

Based on 16S sequence data, this genus contains a large number of phylogenetically defined species (Lücking et al. Reference Lücking, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Gillevet, Chaves, Sipman and Bungartz2009). Of 22 lichenized samples analyzed from different lichenized fungal genera and species from different geographical regions, 21 were shown to be specifically distinct and only two samples, from two different, closely related lichenized fungal species collected at the same locality, represented the same species. Preliminary 454 pyrosequencing data of 47 samples of Dictyonema s. lat. lichens revealed an even higher phylogenetic diversity of Rhizonema photobionts (J. D. Lawrey, M. Dal-Forno, R. Lücking, P. M. Gillevet & M. Sikaroodi, unpublished data). Thus, Rhizonema is the second most diverse lichenized cyanobacterial genus after Nostoc. The phylogenetic data also show that the cyanobacteria in this genus are highly plastic, forming clusters of cells, rather than filaments, in lichens with the fungi Acantholichen, Coccocarpia, Cora, Corella, and Stereocaulon, but phylogenetically these are mixed with filamentous forms from Dictyonema lichens (Lücking et al. Reference Lücking, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Gillevet, Chaves, Sipman and Bungartz2009). On the other hand, the filamentous forms, which are supposed to be hardly altered in the lichenized stage, form two distinct morphological groups, one being found in Dictyonema lichens, with rather broad, low cells, and the other in Cyphellostereum lichens, with narrower, higher, quadratic cells. Their colour also differs, being more distinctly blue in the Cyphellostereum photobiont. Yet these morphological groups do not appear to be correlated with phylogenetically defined species or species groups (J. D. Lawrey, M. Dal-Forno, R. Lücking, P. M. Gillevet & M. Sikaroodi, unpublished data).

Rhizonema interruptum Lücking & Barrie sp. nov.

Characterized by trichomes with broad, low cells with blue-green colour and sparse to abundant, intercalar, yellowish heterocytes.

Calothrix interrupta Carmich. ex Hook. in Smith, Engl. Fl. (London) 5: 368 (1833) [nom. inval., ICN 13.1.e]; Stigonema interruptum (Carmich. ex Hook.) Hassall, Hist. Br. Freshw. Algae 2: 229 (1852) [comb. inval., ICN 13.1.e, 43.1]; Rhizonema interruptum (Carmich. ex Hook.) Thwaites in Smith & Sowerby, Manual of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology (Washington) 4: tab. 2454 (1849) [comb. inval., ICN 13.1.e, 43.1]; Scytonema interruptum (Carmich. ex Hook.) Cooke, Br. Freshw. Algae 1: 266 (1882) [comb. inval., ICN 13.1.e, 43.1]; Dictyonema interruptum (Carmich. ex Hook.) Parmasto [ad int.], Nova Hedwigia 29: 122 (1978) [comb. inval., ICN 13.1.e, 34.1.b]

Type: Ireland, County Kerry, Killarney, Turk Cascade, 1832, Harvey s. n. (E—holotype; BM—isotype; the photobiont present in the type material of the lichenized fungus Dictyonema coppinsii).

Photobiont of Dictyonema coppinsii; filamentous. Trichomes isopolar, uniseriate, cylindrical, formed by low rectangular cells 15–20 µm wide and 5–10 µm high, with blue-green pigmentation embedded in a thin, dense, gelatinous, hyaline sheath; terminal cells smaller, 7–13 µm wide and 3–7 µm high. Branching rare, representing true branching of T type. Heterocytes sparse to frequent, intercalar, yellowish, 12–18 µm wide and 4–8 µm high. Asexual reproduction not observed.

Ecology and distribution

Lichen-forming; on mossy soil or rocks or epiphytic, often overgrowing bryophytes. Currently assumed to have the same distribution as Dictyonema coppinsii but sequence data are required to test this assumption.

Notes

The description of Rhizonema interruptum represents the morphotype of Rhizonema found in lichens formed by Dictyonema species, characterized by broad, low cells with blue-green to olive-green colour. Except possibly for colour, there do not seem to be any characters that would distinguish Rhizonema species at the species level, so culture data are required to test whether phylogenetically defined species (Lücking et al. Reference Lücking, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Gillevet, Chaves, Sipman and Bungartz2009) also differ in phenotypic or physiological aspects (B. Büdel, pers. comm. 2012 ). Sequence data of the 16S gene indicate that Rhizonema interruptum is restricted to lichens formed by the western European Dictyonema coppinsii and has so far not been found in other lichens from tropical regions (Lawrey et al. Reference Lawrey, Lücking, Sipman, Chaves, Redhead, Bungartz, Sikaroodi and Gillevet2009; Lücking et al. Reference Lücking, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Gillevet, Chaves, Sipman and Bungartz2009; Dal Forno et al. Reference Dal-Forno, Lawrey, Sikaroodi, Bhattarai, Gillevet, Sulzbacher and Lücking2013).

Additional specimens examined (paratypes; the photobiont present in the lichen material cited). Great Britain: Scotland: V.C. 105, Ross and Cromarty: Corrieshalloch Gorge National Nature Reserve, along Droma River 20 km S of Ullapool, between the A832 and A835 roads near Braemore, Scottish Highlands, 2011, Douglass s. n. (F, hb. Douglass).—Portugal: Azores: Terceira, Serra de Santa Barbara, 38°44′N, 27°19′W, 930 m, vii 2008, Aptroot & Schumm s. n. (hb. Schumm 14158). Madeira: Ribeiro Frio, Ertz 10475 (BR, GMUF).

Financial support for this study was in part provided by grant DEB 0841405 from the National Science Foundation to George Mason University: “Phylogenetic Diversity of Mycobionts and Photobionts in the Cyanolichen Genus Dictyonema, with Emphasis on the Neotropics and the Galapagos Islands” (PI: J. Lawrey; Co-PIs: R. Lücking, P. Gillevet). We thank David Hawksworth for valuable discussions on nomenclatural issues and Manuela Dal-Forno, James Lawrey, and John Douglass for access to material.