Introduction

The amazing Cyrenean cemeteries are the product of a monumental funerary culture, manifested through an incredibly large number of tomb-types. New tomb models frequently appeared, evolved, intermixed and changed during the long lifespan of use of this necropolis, lasting about a millennium, from the Archaic period to Late Antiquity (Cassels Reference Cassels1955; Rowe Reference Rowe1956, Reference Rowe1959; Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975; Thorn Reference Thorn2005).

In this context Fabbricotti (Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006) identified a peculiar group of Cyrenan rock-cut tombs whose interiors had architecturally elaborate full Doric façades with loculi opening off the intercolumnia. The type was already known (Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975, 155–156), as it includes famous tombs like W16, W20 and the ‘Altalena Tomb’ (Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1976, Reference Bacchielli1993, 22–81; Thorn and Thorn Reference Thorn and Thorn2009, 295). However, FabbricottiFootnote 1 had the merit not only to have identified more examples, but also to have considered, for the first time, the whole series as a coherent typological group, whose specimens are all clustered on two specific spots in the Western Necropolis: three examples (W16, W17 bis, W20) on the steep western side of Wadi Bel Ghadir (Di Valerio Reference Di Valerio and Menozzi2008, Reference Di Valerio and Menozzi2020) and four examples (Altalena, W96, W97, W98) on the nearby Haleg Stawat (Cherstich I. Reference Cherstich, Menozzi, Di Marzio and Fossataro2008). Other similar tombs can still be hidden and buried in those areas, especially in the lowermost parts, where the natural colluvial deposits seem thicker.

The role of these tombs in the history of the Cyrenean cemeteries is important. For centuries the local funerary monumental culture was focused on spending resources only for external façades, but an augmented complexity of the interiors can be seen during Late Hellenistic times, as a consequence of a complex dialogue with the Alexandrian world, as discussed more in detail elsewhere (Cherstich Reference Cherstich, Menozzi, Di Marzio and Fossataro2008a: 77–84; Reference Cherstich2008b). In this context the tombs of the ‘Internal Doric Façade’ group are a key element, due to their possible dating, between late 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, which would make them the earliest Cyrenean rock-cut tombs where a certain degree of attention was focused on the interiors.

The present article must be considered as a kind of ‘addition’ to the Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006 article, as well as an homage to her efforts. The tomb here proposed is certainly not identical to the ‘Internal Doric Façade’ group, but it is certainly closely related in terms of both position and type, as a variation of the same model. Tomb S181 has only been briefly mentioned before in Cassels’ gazetteer which did not report about its interior (Cherstich Reference Cherstich2008b: 84; Cassels Reference Cassels1955: 35; Thorn and Thorn Reference Thorn and Thorn2009: 238). This article aims at completing this gap in the knowledge.Footnote 2

The topographic context

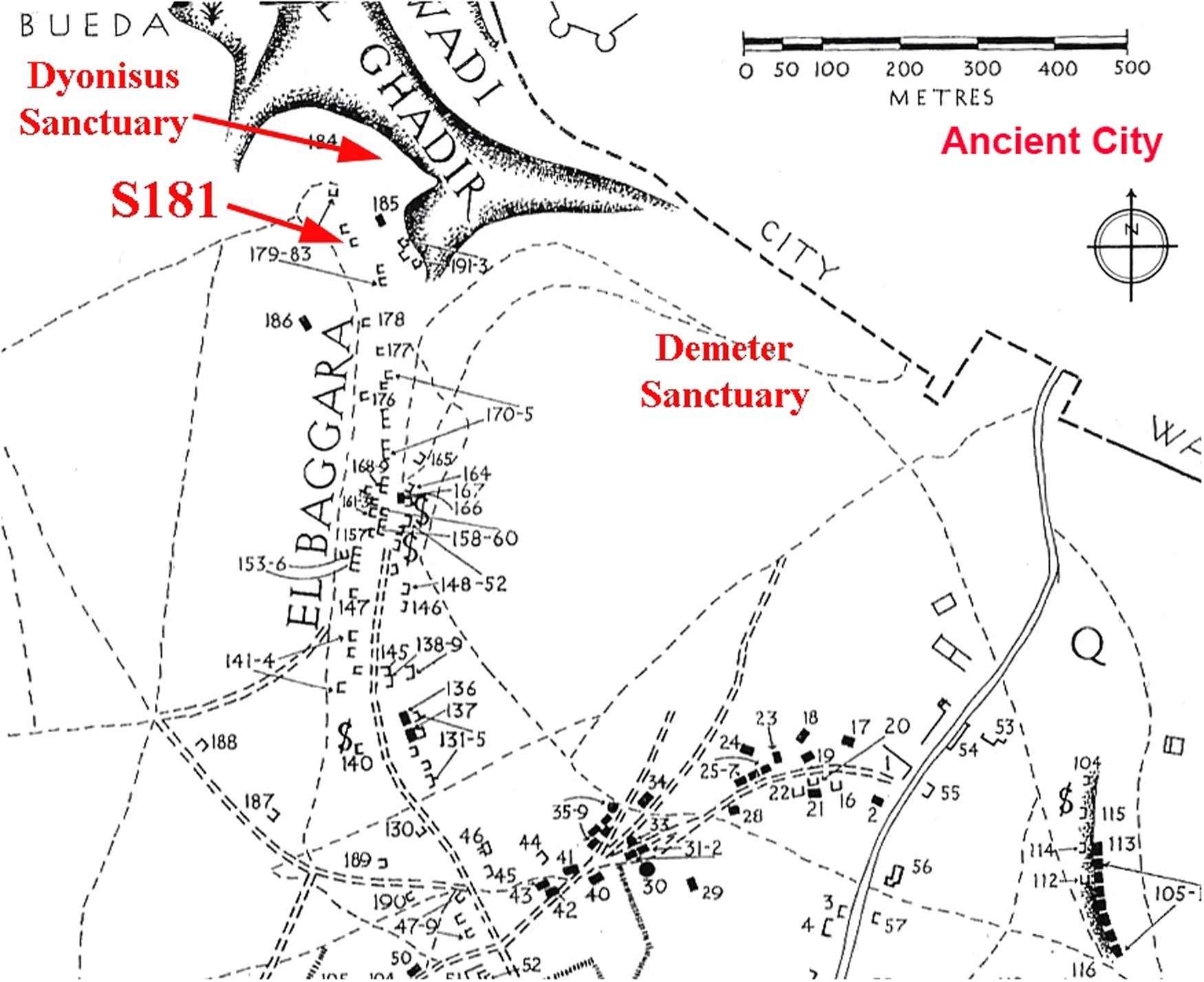

The tomb is located on the north-westernmost corner of what Cassels defines as ‘Southern Necropolis’ (Cassels Reference Cassels1955: Plate I), but which is still part of the same Wadi Bel Ghadir on which the tombs of Cassels’ Western Necropolis described by Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006 are located, albeit on a southernmost portion, south-east of Ain Bueda (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Position of Tomb S181 over Cassels 1995 pl.1 map of the Southern Necropolis.

Figure 2. Topographical Context of Tomb S181 (GIS: L.Cherstich, Chieti Mission, Satellite ©2020 Google, Image © 2021 Maxar Technologies, used as a background image through the ‘QuickMapServices’ plugin in the QGIS software). See colour version online.

Tomb S181 is on the left flank of an ‘alek’ or small wadi mouth which ends in Wadi Bel Ghadir. Cassels’ map of the Southern Necropolis calls it ‘El-Baggara’ (Figure 1): a rather problematic toponym, as the locals use it for the whole area above the southern, and sometimes western, edges of Wadi Bel Ghadir.

The rock-cut monuments of this side of the small wadi are organized on different levels and Tomb S181 is located on the edge of the uppermost terrace. Here the number of tombs is lower than what is below or in the inner part of the small wadi (Figure 2). If one also considers the shape of nearby tombs, it is possible that tombs in this line are later Hellenistic additions to an otherwise dense sepulchral landscape which started to be filled in its lowermost part with monuments during earlier time periods. On the lower level it is also possible to see the rock-cut sanctuary of Dionysus (Menozzi Reference Menozzi2015: 60–62; Reference Menozzi, Russo Tagliente and Guarneri2016: 586–588). All these levels are the continuations (on different heights) of the same, possibly forking, track coming from the area of Tomb S140 (Cassels Reference Cassels1955: pl.1) (Fig. 1). This route has been used at least since Late Archaic times, due to the presence of sarcophagus chamber tombs (Cherstich Reference Cherstich2008b: Figure 1).

The lower level was possibly the main and oldest route connecting to the road passing through the Western Necropolis and the tombs described in Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006. This route was believed by Stucchi (Reference Stucchi, Barker, Lloyd and Reynolds1985: 69, 71, Cherstich Reference Cherstich, Muskett, Koltsida and Georgiadis2002: 21) to be the main road to Phykous.Footnote 3 However, the complex tracks’ system was possibly more aimed at local traffic, connecting tombs, springs, and sanctuaries (Figure 2).

Tomb S181 is on the fringes of this ancient tracks’ system, in an area which was possibly unoccupied by tombs during earlier time-periods, farther from the most-trafficked route below. The tomb was cut off a geological rocky wall, naturally exposed by the erosion of Wadi bel Ghadir. On the other hand, if one looks at the area above the tomb, on the upper part of the valley slope, on the top of the hill, there is only a couple of built tombs (Figure 2, leftmost part). Here the bedrock is less visible, hidden as it is by a thicker layer of superficial soil. It is not to exclude that the area hosted some agricultural fields in antiquity, as they are in use now. There are also a few lines of orthostats, typically used in Cyrene for marking roads and land divisions (see Figure 2 for their positions), and their presence may make sense in this context. Whether the holders of Tomb S181 were also somehow connected to these fields above it is difficult to ascertain, albeit it is a possibility.

Description of the exterior

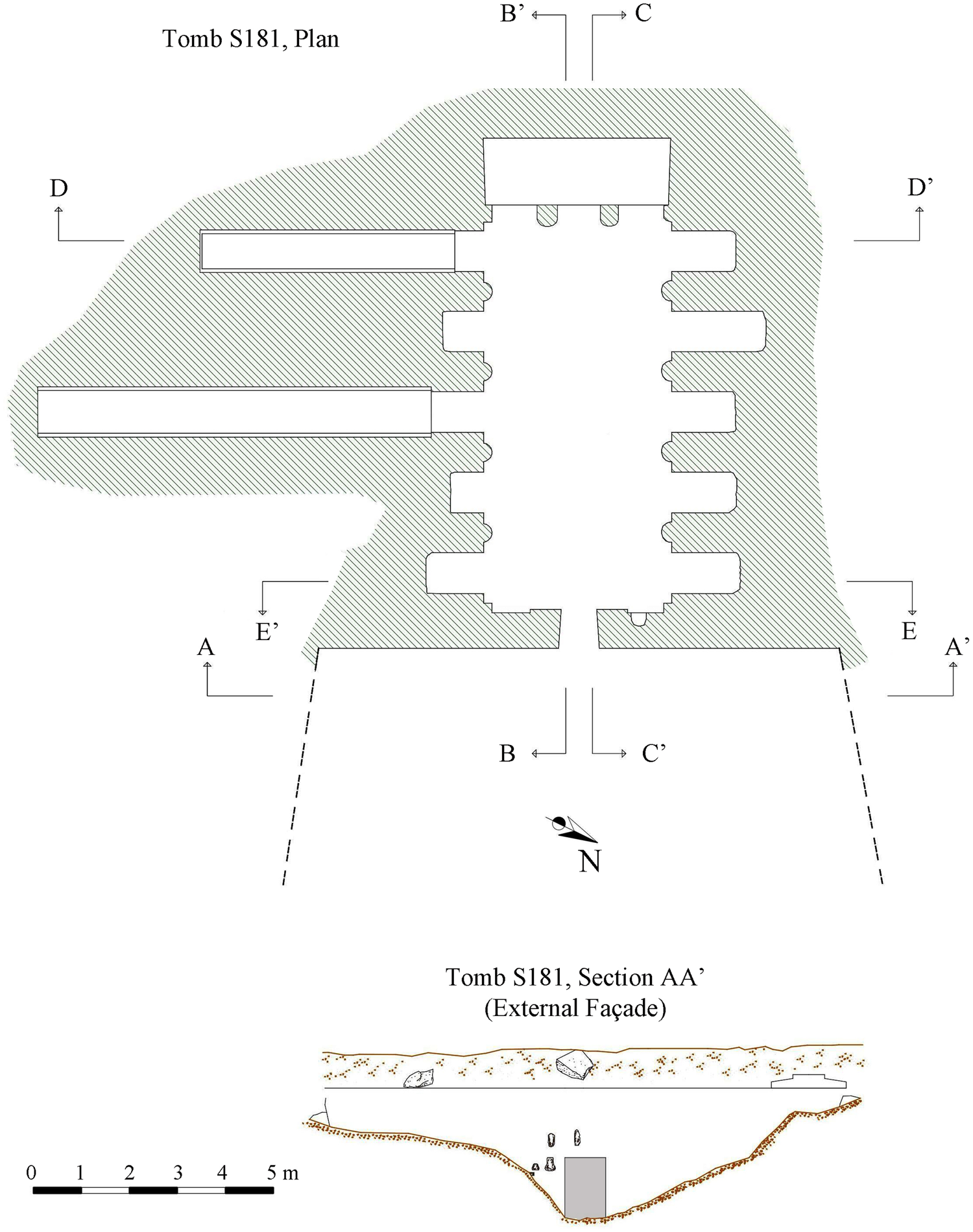

Like almost all the Cyrenean rock-tombs, Tomb S181 opens off an open-air courtyard (Figure 3), probably created by ancient quarrying activities (Cherstich et al. Reference Cherstich, Menozzi, Antonelli and Cherstich2018). When the tomb was visited by the present writer, in 2006, the court was still mostly buried, but the general framework was clear: the north-eastern side was open to the track, while the south-western side hosted the façade and the entrance. The court was about 5 m long (from the external façade to the possible end of the court), but one could not be accurate about it since its eastern limits were buried and the length had to be estimated from the soil's level.

Figure 3. Tomb S181, Map and External Façade (Drawing: L. Cherstich).

The external façade (Figure 3, lower part) was c. 11 m wide, and most of it was invisible, buried under the soil deposit and vegetation. The visible part of the façade looked like an almost smooth rock-cut wall with a single entrance in the middle. The upper rock-cut ridge was barely visible, but it could have been the external limit of a now-buried rock-cut long socket, possibly originally conceived to host a few lines of isodomic masonry. On the northernmost corner of this socket one can see a small roof-shaped slab which may have fallen from uphill, behind the tomb. Due to its shape, it may have been part of the roof of a small isodomic-built tomb or built sarcophagus (e.g. Thorn Reference Thorn2005: Figure 252), located somewhere behind and above Tomb S181.

Five niches were cut nearby the entrance: one of them is very small but the other four were certainly constructed for Roman portraits (Di Valerio et al. Reference Di Valerio, Cherstich, Carinci, Siciliano, D'Addazio, Cinalli, Briault, Green, Kaldelis and Stellatou2005; Cherstich and Cherstich Reference Cherstich, Menozzi, Di Marzio and Fossataro2008; Cherstich Reference Cherstich2011). Their presence attests how the bare rock of the façade was certainly visible in that time-period, and not hidden behind a hypothetical, now-lost masonry. On the other hand, we cannot exclude that the upper part of Tomb S181's façade originally had an isodomic built part resting on the above-mentioned socket. Unfortunately, without an excavation of the silted court it is impossible to ascertain it.

Description of the interior: the plan

The entrance leads to a long chamber (Figure 3) which, for its size, may even be considered like a shorter version of a ‘galleried’ long chamber (rock-cut types N and O in Thorn Reference Thorn2005: 349–352). The chamber is roughly regular, measuring c. 845 cm in length and c. 385 cm in width. The accuracy of these measurements must be taken with a pinch of salt, given the roughness of the lower part of the rock-cut walls. Furthermore, the floor of the chamber was hidden, visible under the soil which penetrated from the entrance during the centuries. This soil deposit should be at least 60 cm thick in the deepest point of the chamber (judging it from the loculi, as shown in Figure 5, upper part) while at the entrance it should have been 120–140 cm thick, at least.

Figure 5. Tomb S181, Interior Chamber, Short Sides (Drawing: L. Cherstich).

Each of the two long sides of the chamber hosts five loculus entrances, each one c. 85 to c. 95 cm wide, while a false, rock-cut full Doric peristyle can be seen running all around the chamber.

All the entrances on the right, northern-western side lead only to unfinished, roughed-out loculi, mostly too short to have been used.

Of the entrances on the left, southern-eastern side, only the third and fifth ones lead to real loculi, of the Cyrenaican type (with multiple internal levels). The third loculus is c. 8 m long and it has 2 levels, while the fifth loculus is c. 5.3 m long and it has 3 levels, each one c.130 cm deep (see section in Figure 5). These two loculi were mostly empty in 2006, if not for their lowermost parts filled with debris and soil, possibly having been looted in unknown time-periods. Judging from the fifth loculus, it seems like the finished entrances were tall (c.240 cm), suggesting that the chamber's floor may be even deeper, unless the soil deposit hides a step descending towards the loculi, and the floor is therefore higher.

Half-columns separate each entrance (Figure 4), and the same colonnade continues also on the front wall, the south-western side, (Figure 5, upper part) where a space or rough recess has been cut off behind a couple of columns whose rears are square-cut, as if they were jointed to half pilasters on their backs. This recess is also quite high, elevated above ground level. The two corners between the front wall and the two long walls are decorated with roughly cut, unfluted quarter columns. On the other hand, the easternmost endings of the two long walls (nearer to the tomb's entrance) are marked by pilasters which are half the width of a half-column.

Figure 4. Tomb S181, Interior Chamber, Long Sides (Drawing: L. Cherstich).

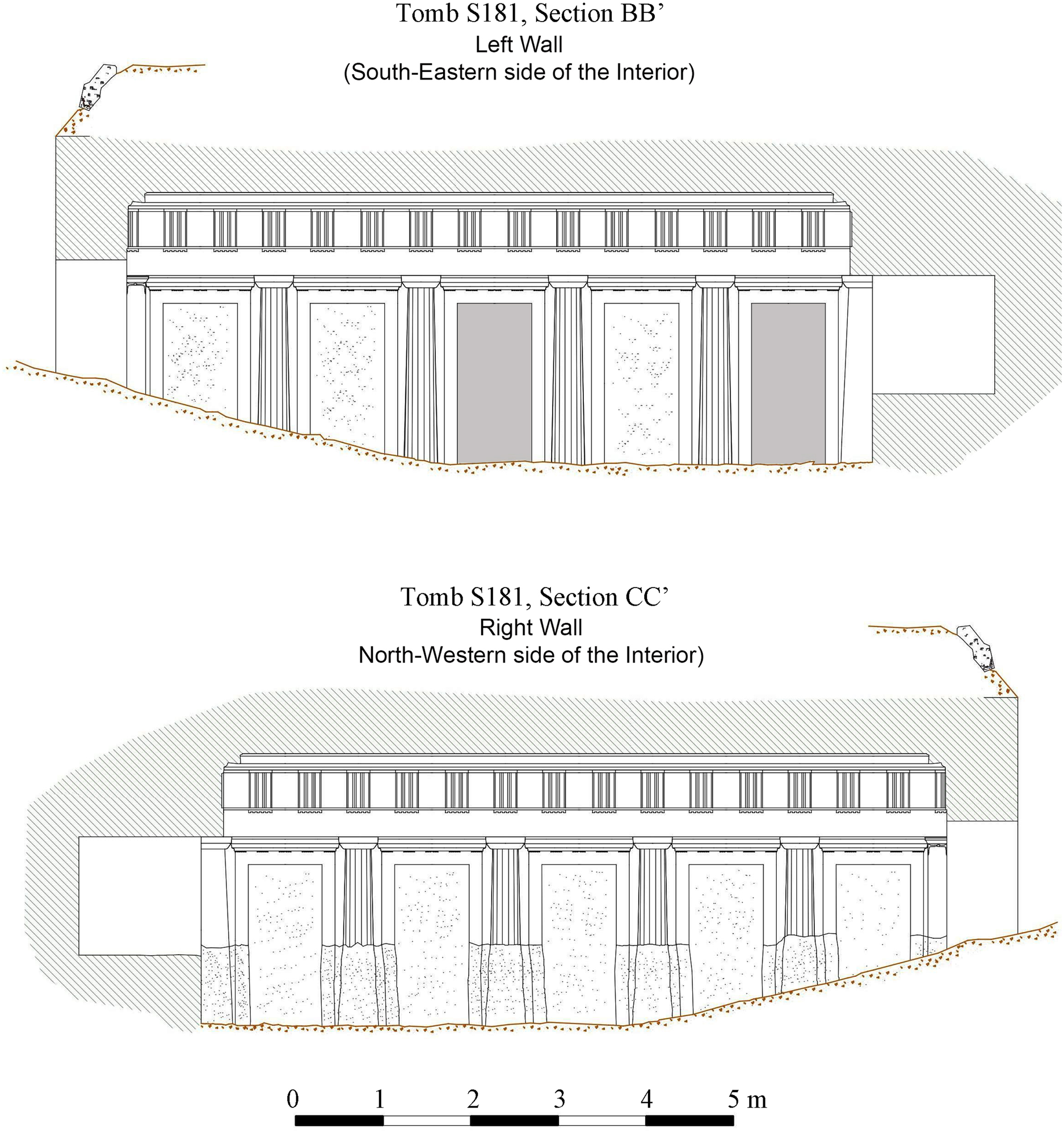

Description of the Interior: the elevations

The half-columns’ shafts seem to have a simple style of fluting with wide-angled arises, while the fluting itself is almost flat (and somehow almost invisible). On the other hand, there is no fluting at all on the two quarter-columns on the corners between the front wall and the westernmost endings of the two long walls. It is worth noting that the peristyle is not in a finished state and, while the half-columns on the left, long side (south-east) seem to be almost (albeit not completely) finished, those on the right, long wall (north-western side) and on the front wall (south-western side) still have their lower parts un-worked and only roughed-out (compare Figures 4 and 5). Looking at the left, long side (where shafts are possibly more finished) one can see how these half-columns have no entasis at all, but they taper upwards: the lowermost recordable diameters are of c. 37.8 cm, while the upper diameters, just below the capitals, are of c. 29.3–29.5 cm.

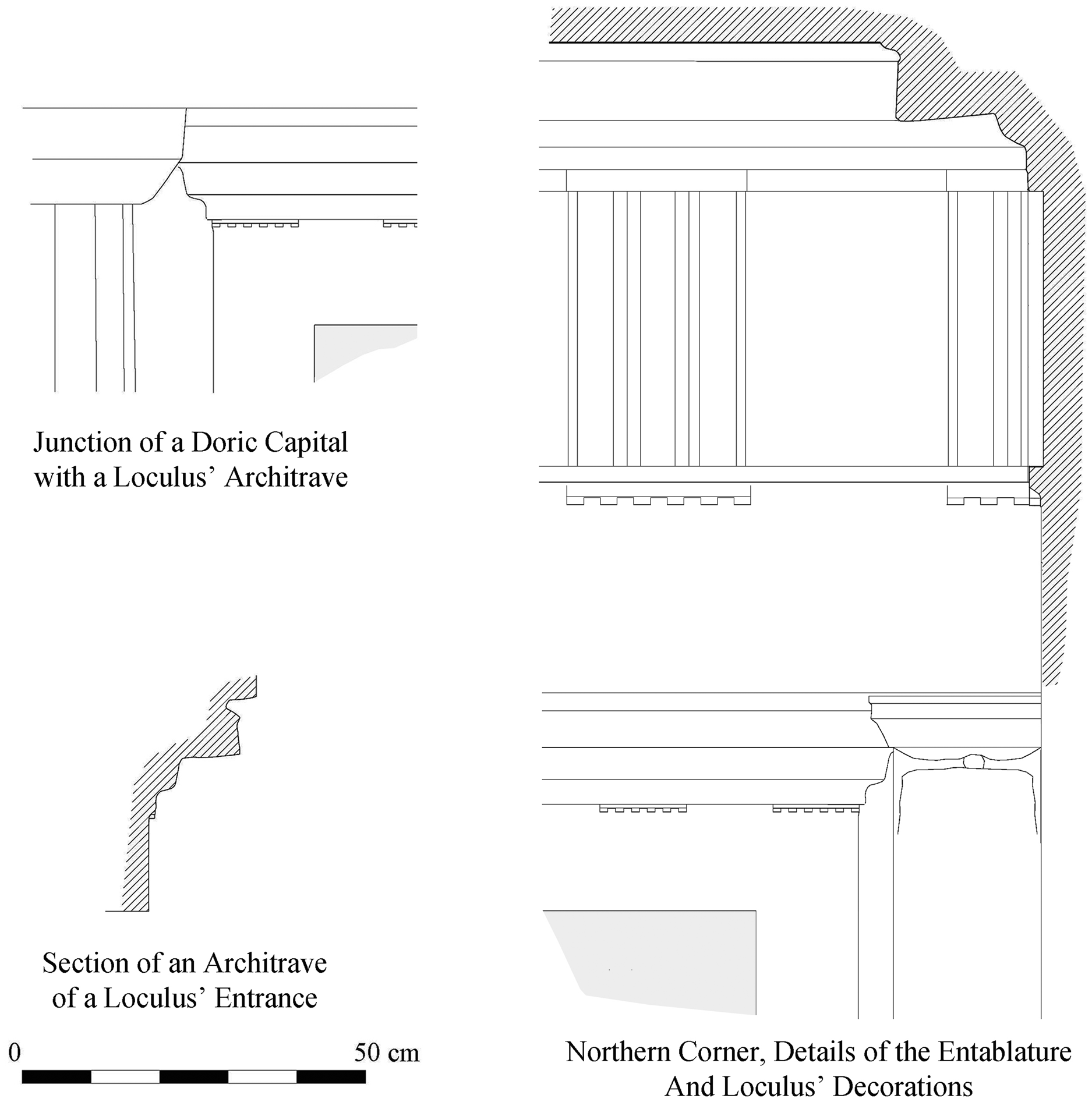

Each half-column is topped by a simple Doric capital of Classical/Hellenistic model, while the two ending pilasters on the easternmost parts of the long sides have simple capitals (a plain square echinus surmounted by a cavetto/splay capital) with a ribbon decoration below (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Tomb S181, Details of Mouldings and Decorations (Drawing: L. Cherstich).

Looking above the capitals to the entablature, it is possible to see how the architrave is c. 33 cm high (from the bottom of the architrave to the top of the taenia above the regulae) while the Doric frieze is c. 43 cm high (from the bottom of the metopes and triglyphs to their upper parts).

Triglyphs are 26.3–26.4 cm wide, while the metopes’ widths vary more. Those on the interior front wall, the south-western side, are wider (c. 38–38.25 cm) than those of the two long sides (c. 29–29.5 cm). The reason behind this scheme is, off course, the clear and obvious relationship with the intercolumniations of the half-columns. The artisans respected the canonic tradition of putting a triglyph on the axis of each column (as clearly visible on Figures 4 and 5), however they applied a different spacing rhythm to different sides of this chamber. In fact, on the front wall (south-western side) the intercolumniation between the two half-columns is 130.26 cm, but there is only one triglyph in the middle (Figure 5, upper part). On the other hand, on the two long sides the intercolumniations are of c. 168 cm, and there are two triglyphs in the middle (Figure 4).

The endings of the south-western façade (the front wall) (Figure 5, upper part) have metopes which, just above the quarter-columns on the corners, are marked by single, thin rectangular elements which are just one-thirds of triglyphs. These elements act as junctions with the metopes on the westernmost corners of the two long sides’ friezes. Looking the opposite way, on the easternmost corners of the long sides, one can see half-triglyphs ending the long friezes, just above the pilasters (Figure 5, lower part, and Figure 6, right part).

The same Doric frieze continues in the north-eastern side of the chamber, except for a band around the entrance which abruptly breaks the frieze's shape (Figure 5, lower part and Figure 8). Here the triglyphs have the usual width (c. 26.3 cm) while the four central metopes are 37.5–38 cm wide, and the two side metopes are c. 29.8 cm wide. The two corners of the frieze end with half triglyphs, joining the half-triglyphs which are on the long sides’ endings (Figure 6, on the right).

Figure 8. Tomb S181, View towards Back Wall of the interior in May 2006 (Photo: L. Cherstich).

On all the four walls the upper part of the entablature is finished by a simplified gheison with no mutules and which continues all around the chamber. The passage between the frieze and the gheison is marked by a simple and squat ovolo moulding, while the passage between the gheison and ceiling is marked by a kyma reversa (Figure 6).

Looking again at the area below the entablature, it is possible to notice how all the loculi's entrances on the long sides are decorated with rock-cut mouldings (Figures 4 and 6). Each door has a kind of architrave with five regulae (each one is 12.6 cm wide). Above this element it is possible to notice a kyma reversa leading to a small, projecting cornice.

Then at the north-eastern side near the entrance (Figure 5, lower part), it is possible to see a few roughly cut niches: one big 32.6 × 28 cm on the left side and two smaller ones on the right side. All of them seem too small to be ossuaries: they could have hosted tiny offerings or lamps.

Display strategies and Cyrenean/Alexandrian hybridity

The presence of a peristyle in a tomb (even if false) is traditionally connected with the possible imitation of a house courtyard in some academic literature (Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975: 149–155). However, no firm data confirms the hypothesis. A peristyle is just an architectural model, possibly used for the most different buildings, and one cannot be sure that, when looking at these tombs, the ancient viewer certainly thought about houses. A more contextual approach is to look not for comparisons in domestic architecture, but rather to funerary architecture itself.

Tomb S181 is clearly related to the Internal Doric Façade group of the Western Necropolis, but there are also obvious differences. The tombs described in Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006 usually recall Thorn Type L or ‘wide chambers’ (Thorn Reference Thorn2005: 348–349). However, in two tombs (W16 and Altalena) a different plan-type was chosen due to specific topographical and pre-existing conditions. The ‘long chamber’ of Tomb W16 was carved in this way due to a lack of space since the monument is a re-cutting of an earlier tomb, squat in a line of small Archaic rock-cut monuments. Its inner chamber has the Internal Doric Façade and the connected loculi are only on the front wall, like in all other tombs of the group. On the other hand, the famous Altalena tomb has a small, square chamber with the internal façade on the right side, but this configuration was forced by the natural shape of the wadi wall in that point.

Compared to those examples, Tomb S181 is different, as its long chamber was possibly carved with this peculiar plan-type on purpose, and not due to pre-existing natural conditions. In this context (of a consciously chosen plan model) everything was adapted to the chosen chamber type.

In the tombs of the ‘Internal Façade Group’ the full Doric peristyle with half-columns is used to enhance the entrances to the burial spaces (the loculi) while pilasters with ribbons are used to ‘close’ the sequence of loculi which is concentrated on a single side, the front wall, which is the first visible side of the interior as one enters the chamber. The whole scene is visible with a single glance with the pilasters framing the edges of the visual field.

In S181 the display strategies are similar but distorted. Loculi are in fact on the long sides, and therefore the half-columns and full Doric entablature is present too, while the pilasters are on the extreme eastern corners of the two long sides, as a way of visually closing the sequence of loculi (Figures 4 and 5). It is worth noting that to appreciate the whole false Doric peristyle a single glance is not enough, and one must enter and turn his head to appreciate the Doric frieze continuing also on the back wall (Figure 5, lower part and Figure 7).

Figure 7. Tomb S181, View towards the Front Wall of the interior in May 2006 (Photo: L. Cherstich).

Such an organization of the architectural details suggests great care for the interior, a place which is supposed to be walked around inside, since only those who (are allowed to?) enter the tomb can appreciate the full false Doric peristyle. There is a parallel with the painted false architectures (including an illusionistic colonnade!) which are visible in Tomb S64 (Cherstich and Santucci Reference Cherstich and Santucci2010), visible only for those spending time in the antechamber, given that they are present on its back wall, like the continuing frieze of Tomb S181's back wall, visible only for those who turn their heads.

It is useful to remember how all these details in the tombs’ interiors speak of Alexandrian influences (as widely discussed in Cherstich Reference Cherstich, Menozzi, Di Marzio and Fossataro2008a), and how they were received in Cyrene.

The old local, Cyrenean tradition in funerary architecture, from Archaic to Hellenistic times, was usually focused on positioning decorations and refined architecture on the external façades and open courtyards, where rituals were almost certainly held. Here the decorative elements could be seen even by the casual passerby, while the interiors were usually simple. Decorated open-air courtyards are frequent in Alexandria too, but are usually sunken into the ground and, differently from Cyrene, the façades are usually invisible to those which are not near the court's borders. Furthermore, Alexandrian tombs tend to have elaborate plans and lavishly decorated interiors, and this is the element which is more important to consider when analyzing the possible Alexandrian influences in Tomb S181. More importantly, it is worth reminding as these differences in display strategies and spatial organization may hide different ritual practices and cultural habits regarding the funerary monuments (e.g. the visibility of rituals).

It is important to stress that the connection between Tomb S181 and the Alexandrian funerary architecture is not about exact comparisons in decorative motifs, but rather about where such decorations are located inside the tombs. In fact, the analysis of such comparisons should not be focused on finding similarities for the exact shapes of mouldings or of other tiny decorations. On the contrary, it is more fruitful to compare which are the display strategies and the spatial organization expressed in these rock-cut monuments, by trying to see where the attention of ancient visitors was focused by choosing where to position the decoration. These issues, in fact, may help to (at least partially) reconstruct how the ancients experienced these funerary spaces.

The inclusion of internal elaboration may speak of the imitation/adaptation of Alexandrian ritual (?) behaviours focused on the interiors, and not visible to the casual passersby. However, the Late Hellenistic Cyrenean tombs which display internal decoration, almost always also have an elaborate façade on the outside, suggesting a combination of ancient local ritual customs (focused on the exterior) with new Alexandrian (ritual?) influences (focused on the interior). An example is the monumental, external false façade of Tomb S147 coupled with its elaborate interior with multiple chambers (Cherstich et al. Reference Cherstich, Cinalli, Lagatta, Álvarez, Nogales and Rodà2014). The same is true for Tomb S64, with its external isodomic built façade coupled with a painted and decorated interior (Cherstich and Santucci Reference Cherstich and Santucci2010).

Tomb S181 possibly also had an elaborate external façade, like an isodomic-built screen once resting on the top of the rock-cut wall, and whose collapsed blocks are now hidden in the silted courtyard, as often happens in other Cyrenean tombs (e.g. Tomb S227 in Cherstich Reference Cherstich2008b: Fig. 4). Nonetheless there is certainly a clue that the exterior was also important in S181 and that rituals were also happening in the courtyard: the presence of later, Roman niches for portraits. These objects were aimed at displaying the deceased ancestors on the external façade, somehow continuining a more ancient behaviour, previously practised with the names on the half-figures' bases. The ancient Cyrenaican funerary world did not passively accept Alexandrian and Roman influences, but it changed and adapted them to local customs, or at least this is what seems to have happened in Cyrenean tombs from Late Hellenistic to Early Imperial times, as widely discussed in Cherstich Reference Cherstich2011 and also in Cherstich and Cherstich Reference Cherstich, Cherstich and Rakoczy2008.

The presence of the false peristyle in Tomb S181 may suggest an obvious connection with the famous peristyle-tombs in Alexandria (Venit Reference Venit2002 for full bibliography) but, in terms of structure, Tomb S181 is definitively not a sunken courtyard with chambers opening off it, but it rather respects the ancient and simple Cyrenean scheme of ‘Courtyard-External Façade-Inner Chamber’, which is also more adapt to the steep geomorphology of the area.

It is undeniable that, even if not a pure Alexandrian-style peristyle tomb, Tomb S181 is rather an adaptation to local needs and ancient traditions. Cyrene is, in fact, not Nea Paphos in Cyprus, where Alexandrian models seem to have been used in a purer form in the local peristyle tombs (the ‘Tombs of the Kings’), whose display strategies seem to better reflect purer Alexandrian fashions, at least in their general scheme of the elaborate architecture and real porticoes placed in sunken courtyards.Footnote 4

There is only one pure Alexandrian peristyle tomb in Cyrene (Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1996), in contrast to the hundreds of tombs which respect the ancient local tradition. The reasons behind this difference are not just geo-morphological, as demonstrated by the façades on the flat southern cemeteries (Cherstich Reference Cherstich2008b, 78–80). The main explanation is the strength of a funerary monumental tradition which surely included also ritual behaviours, and which was already ancient when Alexandria was founded. Cyrene possibly even influenced part of the Alexandrian tradition, albeit certainly not being the main inspiration behind that funerary world. On the other hand, Cyrene gradually somehow opened to the new Alexandrian ideas during later Hellenistic times, although always changing and adapting customs and fashions (Cherstich Reference Cherstich, Menozzi, Di Marzio and Fossataro2008a: 134–5; Cherstich and Santucci Reference Cherstich and Santucci2010, 35–8).

The tombs of the ‘Internal Doric Façade Group’ described by Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006 must be analyzed in the same cultural context, but Tomb S181 is definitively more ‘advanced’ in terms of taking Alexandrian strategies in the organization of the interior's decorations. The false peristyle is not limited just to the first wall visible to the visitor, but it is spread all around the chamber.

Speaking of the ‘first wall visible to the visitor’ in Tomb S181, here one can possibly spot further Alexandrian influences on the end part of the chamber (Figures 3, 5 upper part and Figure 7). In the Ptolemaic capitol is in fact not rare to see an ‘elite burial’ at the end of a chamber, something which is unheard of in the old Cyrenean tradition. Such burial is usually defined by an elevated element, cut parallel to the rock-cut wall, like a kline or, later, an arcosolium. In this sense, the elevated recess beyond the two columns in the front, south-western side of Tomb S181 may recall similar solutions with architectural elements, like columns or even full entablatures, in Alexandria. Examples can be seen in Sidi Gabr (Venit Reference Venit2002, 38–41, 195, Figures 20, 23), in the Tomb of the Antoniadis Garden (Venit Reference Venit2002, 41–44, 191–192, Figures 25, 27), Moustapha Pasha/Kamel nos. 2–3 (Venit 2002, 45–49, 61–65, 194–195, Figures 30, 46–47) and in Ras el Tin Tomb 8 (Venit Reference Venit2002, 72–73, 200, Figure 55).

Architecture and Chronology

Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006: 98) identifies four elements as typical of the Cyrenean variant of Doric: simple moulded bases, Ionic fluting, the half-columns engaged against the inner sides of antae or porch walls (the ‘Cyrenaican Antae’ in Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975: 83–84; Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1981, 123–125) and the heavy double soffit moulding under the gheison. Most of these elements can be seen in tombs of the Hellenistic period which have full Doric orders in their external façades, as well as in those tombs which have internal ones (i.e. the Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006 tombs).

Surprisingly enough, Tomb S181 does not show any of those details. The finished shafts have simple Doric fluting while the quarter columns on the corners are unfluted, the Cyrenaican antae are missing (in fact there are pilasters at the ends of the half-columns lines) and the moulding under the gheison is a simple ovolo. On the other hand, one cannot be sure about the bases, since the bottom of the chamber is buried, and the lower shafts may be unfinished.

In general, it seems that even if the general architecture of S181 is more complicated than other Cyrenean tombs, its tiny details seem simplified, if compared to those of the Internal Doric Façade group. This is furthermore confirmed by the lack of mutules on the lower flat surfaces of the gheison. This absence of mutules has comparisons with monuments in the Cyrenean Agora like the mid-third century BC Portico O2 which has also a similar pilaster with ribbon (Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1981: 111–138, in particular p. 133 Figures 82, 91, 95) or the ‘Water-well Cover’ which has also unfluted column shafts (Stucchi Reference Stucchi1965: Figures 114, 121; 1975: 131–132, Figure 114) possibly dated to Late Hellenistic times.Footnote 5

The ovolo moulding connecting frieze and gheison in Tomb S181 can be also seen in some tombs of the Interior Doric Frieze group like the Altalena (Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1976: 359 Figure 4) and W98 (Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006: Figure 24).

The architrave height (33 cm) to frieze height (43 cm) ratio in Tomb S181 is 1:1.3 which, according to the list made by Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006: 101), is identical to what can be seen in the Doric entablatures of external façades of Tombs N178, W80 and N151. This last tomb has also the same, identical measurements of S181: 33 cm (architrave) and 43 cm (frieze). The external façade of Tomb W80 (Thorn and Thorn Reference Thorn and Thorn2009: 293) has another feature: the unfluted Doric columns, which recall the lightly fluted columns and unfluted quarter-columns of Tomb S181. Stucchi (Reference Stucchi1975: 153) dates W80 to the first century BC, although he does not specify on which grounds. Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006, 99) seems to suggest that the higher the frieze, the later the tomb may be. In this sense it is worth noting how the architrave to frieze ratio of 1:3 in Tomb S181 is not far from the 1.27 ratio of the mid-third century BC Portico O2 in the Agora, but it is definitively different from (and possibly later than) the 1:1.2 ratio of the late fourth century Strategheion. In any case, these ratios cannot be used as straight date-indicators, as they must always be considered in their wider contexts, and combined with other chronological indicators: in fact even the possibly Roman period-dated Stoa B5 shows a similar 1:1.18 ratio (Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006, 99).

The triglyphs of Tomb S181 lack the under-cut (‘sottosquadro’) and this phenomenon, according to Bacchielli (Reference Bacchielli1981, 133) in Cyrene starts during the second century BC.

Compared to the Internal Doric Group, Tomb S181 seems to have proposed a more coherent solution to the problem of the Doric Frieze's ends. Many tombs of the Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006 group (Altalena, W20, W98) display half a metope at the ends, which recall a solution seen on the entablatures of some (albeit not all) Doric external façades in tombs like N171 (Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975: 150–151 Figs. 123, 125) and N228 (Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1980). Tomb S181 uses a different solution, also because its frieze must be adapted to a sequence of four inner surfaces, a situation which is not present in the other tombs. The artisans here varied the metopes’ lengths, so that the ending corners of the front wall were finished by whole metopes (Figure 5, upper part). On the other hand, on the back wall they applied half a triglyphFootnote 6 on the corners (Figures 4 and 6), according to a solution which recalls the friezes on Mustapha Pasha Tomb no.1 in Alexandria (Venit Reference Venit2002, 53, Figure 37) dated to the third century BC.

The decoration of the loculus entrances with regulae on the architrave recalls something seen in the ‘Portico O3’ of the Agora (Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1981: 149–150, Figures 108, 109), dated to the early second century BC. Such regulae were already present in the architrave of the Strategheion (dated to the late fourth century BC) (Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975, Figure 87), but the general door decoration seems more complicated: the Portico O3 remains a better comparison. Similar regulae are also present in the door of a few Hellenistic tombs, although their exact chronology to the century is not fixed (Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975, Figures 125–126) but it can be postulated to range between the 3rd and the 2nd centuries BC.

Since there is no stratigraphy or artefacts to use as chronological bases, the above-mentioned stylistic comparisons are the only available date indicators. Not all of them are really fixed or helpful, but a general trend is clear. Summing up all the available comparisons, Tomb S181 cannot have been cut before the middle Hellenistic period: a date in the second century BC is here proposed.

Conclusions

Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006 identified common details in the whole Internal Doric Frieze Group suggesting that those tombs reflect the craftmanship of the same atelier or of the same tradition. On the other hand, Tomb S181, even if related, seems to be more unique. Some traits are definitively like those of the Fabbricotti Reference Fabbricotti, Fabbricotti and Menozzi2006 group, but these have been re-formulated in a more grandiose setting, while some motifs were also simplified, as described above. A higher degree of influence from the Alexandrian world is detectable, although still hybridized within the milieu of the ancient local funerary culture.

Tomb S181 is a revolutionary tomb, but one must also consider that its internal architecture was never finished. Even so, even if uncompleted, the tomb has been almost certainly used. This seems suggested not only by the two finished loculi, but also by the presence of niches for roman portrait busts on the external façade. These niches clearly suggest how, during the Imperial period, some ‘ancestors' were certainly buried inside and ostentatiouly displayed on the exterior.

Given these considerations, the reasons why S181 was never finished are, for the moment, unknown. However, its uniqueness and way to re-elaborate the ancient local tradition may have something to do with its story. Possibly resources ended since the aimed plan was too expensive, or the revolutionary rock-carving masters died. Whatever the cause, Tomb S181 remained as it is now: a unique tomb in the necropolis of Cyrene.