Introduction

In the last decade, the Islamic period Palermo phases have been the focus of many projects, which have demonstrated the importance of the city in Sicily and as a hub in the central Mediterranean. The goals of these new studies were the identification of the type of products circulating from the ninth to the eleventh century, their distinction from the Norman period ceramics, the recognition of the evolution over time of the different classes and, more in general, the identification of the chronological indicators. The increased number of systematic analyses of pottery assemblages coming from stratigraphic excavations rather than by selections based on aesthetic characteristics is providing an increasingly reliable relative sequence for Palermo's ceramics. The analysis of ceramics associations allows also to build absolute chronological references. However, it is still difficult to establish definitive and precise absolute chronologies for the individual types identified, with a few exceptions. The assemblages analysed so far are ascribable to the end of the ninth until the first half of the eleventh century; however, ceramics from the first part of the ninth century and the second half of the eleventh century are not well understood. It means that we cannot observe the process of the Islamization of material culture, which is already accomplished at the end of the ninth and the beginning of the tenth century. The dynamics of pottery exchange and production is difficult to reconstruct for the eleventh century, in particular the second half of the century, when Sicily underwent a political change from Islamic to Norman rulers.

Palermitan pottery was investigated to reconstruct socio-economic dynamics. In particular the topic of Islamization of material culture has been discussed thanks to the analysis of assemblages dated to the end of the ninth and the first half of the tenth century (Nef and Ardizzone Reference Nef and Ardizzone2014). Furthermore, the distribution of Palermitan ceramics and the importation of pottery in the Sicilian capital provide some new information useful to contribute to the reconstruction of the economic dynamics in the Mediterranean (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini and Sacco2016; Sacco Reference Sacco2018b).

In this paper, we aim to present an overview of Palermo pottery production from the end of the ninth to the eleventh century. The great part of the chrono-typology here exposed comes from the study of the assemblages of the Gancia Church and Bonagia palace excavations (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Ardizzone and Nef2014, Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Anderson, Fenwick and Rosser-Owen2018a; Pezzini and Sacco Reference Pezzini, Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018; Sacco Reference Sacco2016, Reference Sacco2017, Reference Sacco2018b). Both sites (Fig. 1) are situated along the Via Alloro, in a quartier that included the palatine city Khalisa (founded in 937–38, according to Ibn al-Athīr) and the ḥārat al-ǧadīda (‘new quartier’ perhaps developed in connection with the Khalisa, cf. Reference Nef, Arcifa and SgarlataNef (in press)) (Pezzini Reference Pezzini1998; Pezzini et al. Reference Pezzini, Sacco, Spatafora, Sogliani, Gargiulo, Annunziata and Vitale2018). In both cases, traces of several settlement phases, datable from the end of the ninth to the eleventh century, have been documented. An Islamic necropolis has been identified before the settlement in Gancia Church (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Ardizzone and Nef2014). The information coming from the systematic analysis of the assemblages of these two sites was integrated by published data (for example Aleo Nero Reference Aleo Nero2017; Aleo Nero and Vassallo Reference Aleo Nero and Vassallo2014; Arcifa Reference Arcifa1996; Arcifa and Bagnera Reference Arcifa, Bagnera, Ardizzone and Nef2014, Reference Arcifa, Bagnera, Anderson, Fenwick and Rosser-Owen2018b; Arcifa and Lesnes Reference Arcifa, Lesnes and Démians D'Archimbaud1997).

Figure 1. Sicily and the localization of Gancia and Bonagia palace in Palermo.

Palermitan pottery production: generalities

During the Islamic period, Palermo was a self-sufficient city, producing the whole range of ceramics needed in the city: cooking pots, serving dishes, tableware, ceramics for hygienic use, architectural, illumination, polyfunctional and irrigation ceramics, storage and transport jars (Arcifa and Bagnera Reference Arcifa and Bagnera2018a; Sacco Reference Sacco2016). The imported pottery products are very few: amphorae, tableware (both luxury and common wares) and cooking ware. The provenance of the cooking ware is unknown for the majority of the cases, while most of the imported amphorae and tableware (glazed or not) come from the Tunisian and Sicilian area (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini and Sacco2016; Sacco Reference Sacco2017, Reference Sacco2018b). Few Egyptian, al-Andalus and Chinese glazed tablewares were found in assemblages dated to the end of the tenth and the first half of the eleventh century (Sacco Reference Sacco2017).

The existence of pottery made in Palermo is testified by petrographic analysis carried out on entire assemblages (Testolini Reference Testolini2018, 176–202). In particular, the Ficarazzi clay, coming from pits located between ‘Acqua dei Corsari’ and the mouths of the rivers Eleuterio and Oreto, has been employed (Giarrusso and Mulone Reference Giarrusso, Mulone, Ardizzone and Nef2014, 192; Orecchioni and Capelli Reference Orecchioni and Capelli2018, 261). Even though traces of ceramic workshops are few and dated to a later period (Arcifa Reference Arcifa1996; Arcifa and Bagnera Reference Arcifa and Bagnera2018a; D'Angelo Reference D'Angelo2005; Spatafora et al. Reference Spatafora, Canzonieri, Di Leonardo, Milanese, Caminneci, Parello and Rizzo2014), macroscopic observations of fabrics and surface treatments, as well as the traces left by the use of spacers in the kiln and the type of firing, allowed us to formulate hypotheses about the general organization of the ceramic production. First, two main fabric groups can be recognized macroscopically. The first one (fabric group 1) is red with abundant little and medium white pierced inclusions and few little matt transparent inclusions, and it is observable in tableware and lamps, glazed or not. In the second group (fabric group 2) different functional categories have been recognized: transport, storage/tableware amphorae and small amphorae, handled jars, basins, noria pots, and occasional open-shaped bowls and lamps. It is similar to the fabric group 1 but the white inclusions are generally macroscopically not pierced. This different appearance is the result of a single firing, while the fabric group 1 is double fired. Palermo also produced cooking pots (Testolini Reference Testolini2018, 177–79), but the fabrics are less homogeneous and harder to systematize macroscopically. In particular, for the ollae products (a closed, globular-shaped cooking pot) two main fabrics have been recognized (Pezzini and Sacco Reference Pezzini, Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018, 348). They are both associated with the same morphologic panorama and with the same surface treatment: the first one is a fine fabric, while the second one is quite similar to the amphorae fabric (fabric group 2) and is characterized by more inclusions. This last fabric, with different surface treatments (plain or with a white surface), is observed also in some baking dishes, lids and ‘braziers’ (Sacco Reference Sacco2016). These forms are also documented with a third fabric, also similar to the amphorae fabric but probably coarser and fired at lower temperatures (Pezzini and Sacco Reference Pezzini, Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018, 349, 352). For other cooking pots products identified in Palermo assemblages, it is still not clear if they were produced locally or imported (Pezzini and Sacco Reference Pezzini, Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018).

Fabric group 1: tablewares and illumination

Among the Palermitan pottery, tablewares and illumination pots – above all, the glazed ones – have been the objects of different publications due to their aesthetic value since the 1930s (for example Bonanno Reference Bonanno1979; D'Angelo Reference D'Angelo1972; Ragona Reference Ragona1966; Russo Perez Reference Russo Perez1932). These products, generally characterized by a white salt surface (Reference Sacco, Testolini, Civantos and DaySacco et al. in press), exist in glazed or unglazed versions with no particular morphological differences between the two. A greater tendency to open forms can just be noticed for glazed tableware, while unglazed tableware tends to have closed shapes (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Ardizzone and Nef2014, 208). Instead, the plain tablewares without the white salt surface are rarer (for example Arcifa and Bagnera Reference Arcifa, Bagnera, Ardizzone and Nef2014, 169; Sacco Reference Sacco2016). The evidence suggests that both tablewares and illumination pottery have been fired in side bars kilns (Sacco Reference Sacco2016, 450).

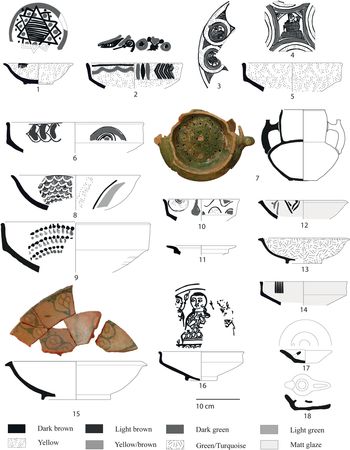

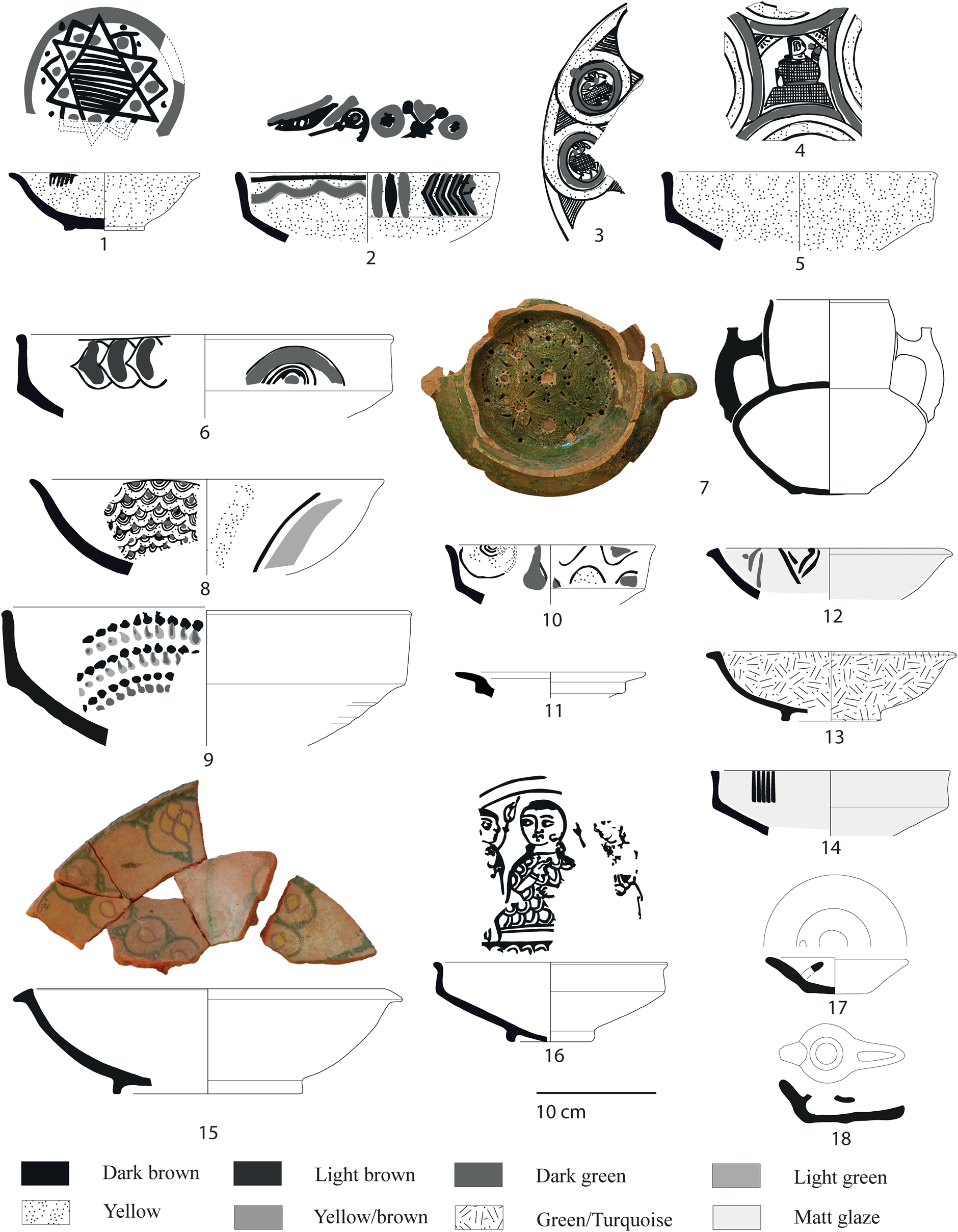

From a morphologic point of view, one of the biggest changes in pottery production in respect of the past is the increased presence of open vessels. For all the Islamic period the carinated bowl is the most widespread, but pseudo-conical and hemispheric bowls are also diffused. The table set also consists of closed forms such as small bottles, jugs with filter, cups and small pots. This panorama seems to be maintained throughout the Islamic age and it is quite conservative over time. These morphological variants are not exclusive to specific techniques nor to particular decoration motifs. So far, the available data allow us to observe evolution details only in some specific forms. For the carinated bowls, from around the mid tenth century, a slight concavity appears just below the carina (Fig. 2.6) and enlarged rims are documented (Fig. 2.6). From the end of the tenth century it is worth noting the presence of bifid rims in the carinated bowls (Fig. 2.14), and the appearance of a specific variant of a carinated bowl (Fig. 2.10) and the flat plate (Fig. 2.11). For the filter jugs, in the first period the filter holes are simple, then becoming increasingly elaborate (Fig. 2.7). During the eleventh century, the progressive replacement of the carinated bowl with the hemispheric one has been documented (Arcifa Reference Arcifa1996; Reference Sacco, Testolini, Civantos and DaySacco et al. in press).

Figure 2. Palermitan fabric group 1.

Palermo workshops were the first in Sicily to produce glazed pottery with the technique of double firing. Recent studies demonstrate that this started at the end of the ninth century (Arcifa and Bagnera Reference Arcifa, Bagnera, Ardizzone and Nef2014, Reference Arcifa, Bagnera, Anderson, Fenwick and Rosser-Owen2018b; Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Ardizzone and Nef2014, Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Anderson, Fenwick and Rosser-Owen2018a), while other centres in Sicily seem to have begun this production about a century later (Fiorilla Reference Fiorilla, Volpe and Favia2009, 197–99; Mazara, Molinari and Valente Reference Molinari, Valente, El Hraiki and Erbati1995; Paternò, Messina et al. Reference Messina, Arcifa, Barone, Finocchiaro and Mazzoleni2018; Piazza Armerina, Alfano Reference Alfano, Pensabene and Barresi2019; Syracuse, Amara et al. Reference Amara, Schoerer, Salvina, Platamone, Thierrin-Michael and Delerue2009).The transmission of some aspects of the new glazing technology from Ifrīqiya has been proved (for example, for the giallo di Palermo, cf. infra), while the arrival of other aspects of glazing technology from other areas cannot be excluded (Reference Capelli, Arcifa, Bagnera, Cabella, Sacco, Testolini and WaksmanCapelli et al. in press).

Five horizons for the glazed wares have been proposed thanks to the systematic analysis of trusted stratigraphic sequences from the Gancia excavations (Sacco Reference Sacco2017). Each horizon has been identified through a combination of information: associations with other functional categories, position in the stratigraphic sequence, introduction or evolution of some specific elements such as decoration motifs, forms and wares.

Palermitan glazed pottery is quite conservative over time from a technological point of view. It seems that no particular technique is linked to a specific shape or decoration style. Consequently, different types of glaze and decorative motifs can characterize the same shapes. The sole exception is probably the mid-eleventh-century pottery known as ‘boli gialli’ (yellow dots), which is characterized by a specific combination of form/technique/decoration (cf. infra) (Reference Capelli, Arcifa, Bagnera, Cabella, Sacco, Testolini and WaksmanCapelli et al. in press).

From a macroscopic point of view, glazed pottery can be divided into two main families: transparent glazes and matt glazes. The most widespread is the transparent lead-glazed ware group, which is divided in two main classes: the polychrome wares (POLY.GW) and the monochrome wares (MON.GW).

The POLY.GW are characterized by a green, brown and/or yellow decoration under a transparent glaze, mostly clear, but also yellow or green. Such glazed pottery groups have been found since the end of the ninth century and during the entire Islamic period. Transparent glazes are characterized by a varied panorama of geometric, pseudo-epigraphic, phytomorphic, zoomorphic and anthropomorphic painted decorative motifs matched in a different way to each other. The combination of technological characteristics (macroscopically analysed) and of the form and decoration style allow us to identify three specific and distinct wares named giallo di Palermo (Palermo yellow), ‘graticcio ware’ and a pottery with a splashed decoration.

Giallo di Palermo (Fig. 2.1–2) is a Palermitan yellow lead-glazed ware (Capelli et al. Reference Capelli, Arcifa, Bagnera, Cabella, Sacco, Testolini and Waksmanin press; Testolini Reference Testolini2018) characterized by its own decorative painted style in green and brown underglaze. Dated from the end of the ninth to the beginning of the tenth century, this production recalls the contemporary jaune de Raqqāda (Raqqāda yellow). Based on the current state of knowledge, we can suppose that the giallo di Palermo was made by artisans probably originating from Ifrīqiya (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Ardizzone and Nef2014; Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 343).

‘Graticcio ware’ (Fig. 2.3–4) is a Palermitan lead-glazed ware (Capelli et al. Reference Capelli, Arcifa, Bagnera, Cabella, Sacco, Testolini and Waksmanin press), also known as ‘tipo pavoncella’ (peacock type) (Molinari Reference Molinari and Pensabene2010), which stands out for the presence of zoomorphic and anthropomorphic motifs filled by a grid (graticcio in Italian). The beginning of this ware is in the middle of the tenth century, and it continued to be produced until the first half of the eleventh century (Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 346–48).

The pottery characterized by a splash decoration appears at the end of the tenth to the beginning of the eleventh century, and can be distinguished in two main decorative variants: with a streak or a pois (Fig. 2.9) decoration (Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 352; Reference Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018a).

The rest of the POLY.GW is more difficult to characterize and group. It is worth noting that the ware with a brown decoration under a green glaze is documented from the end of the tenth to the beginning of the eleventh century. Other than that, the POLY.GW share a similar technique as well as a general style of decoration and vessel shape, but at the same time with a unique combination of decorative variants, which makes it difficult to attribute precise chronologies, and to better connote the production and to identify further modes. However, some decorative motifs occur in specific contexts in our relative stratigraphic sequence, which allows us to suggest chronologies. For example, the chained hearts motif (Fig. 2.6) appears during the first half of the tenth century, after the contexts with the giallo di Palermo, and continues until at least the first half of the eleventh century. The anthropomorphic (Fig. 2.4 and 16) and the scale (Fig. 2.8) decorations appear starting from the end of the tenth to the beginning of the eleventh century and they do not continue much further the mid eleventh century. During the second half of the eleventh century the decorative motifs of POLY.GW underwent a process of simplification (Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 362; Reference Sacco, Testolini, Civantos and DaySacco et al. in press).

The MON.GW are less numerous. The green version is documented in assemblages starting from the first Islamic period at the end of the ninth century (Arcifa and Bagnera Reference Arcifa, Bagnera, Ardizzone and Nef2014, Fig. 1.13; Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Anderson, Fenwick and Rosser-Owen2018a, Fig. 18.1.1). On the other hand, the yellow (Fig. 2.5) and brown monochrome glazed wares are documented starting from the first half of the tenth century (Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 344–46). The morphologic panorama associated with the MON.GW is the same as the POLY.GW.

The same technological characteristics are documented for the lamps. In particular, the white salt surface version, the POLY.GW and MON.GW have been identified. Palermitan workshops produced two main types of lamp: the circular lamps (Fig. 2.17) and the ‘becco canale’ lamps (Fig. 2.18) with a handle and a long spout. From a chronological point of view, during the end of the ninth to the first half of the tenth century the circular lamps are more widespread, while there are fewer examples of the ‘becco canale’ type. During the second half of the tenth century, the trend reversed, with the progressive decrease of the circular lamps in favour of the ‘becco canale’. The ‘becco canale’ continue to circulate during the eleventh century and the circular lamps are absent (Aleo Nero Reference Aleo Nero2018; Alfano and Sacco Reference Alfano and Sacco2018). The ‘becco canale’ lamps are replaced by the open shape lamps probably during the second half of the eleventh century (Arcifa Reference Arcifa1996; Arcifa and Lesnes Reference Arcifa, Lesnes and Démians D'Archimbaud1997).

The second family is the matt glazed wares (MATT.GW), which are also characterized by an under- or overglaze painted decoration. During the end of the ninth to the beginning of the tenth century the MATT.GW are rare and not specific to a form or a decorative style, which are shared with the POLY.GW. They are always characterized by the white salt surface and by a painted decoration under the glaze (Reference Capelli, Arcifa, Bagnera, Cabella, Sacco, Testolini and WaksmanCapelli et al. in press). The first analysis revealed a diversified technological panorama, which includes a combination of undissolved quartz and gas bubbles (Reference Capelli, Arcifa, Bagnera, Cabella, Sacco, Testolini and WaksmanCapelli et al. in press; Testolini Reference Testolini2018, 191) and/or the presence of tin (Reference Capelli, Arcifa, Bagnera, Cabella, Sacco, Testolini and WaksmanCapelli et al. in press). From the end of the tenth to the eleventh century, three new distinct wares can be recognized. The first one is the so-called ‘tipo D'Angelo’ (D'Angelo type), which is characterized by an alternated geometric green and brown motif realized with the same thickness under a matt glaze known as ‘tratti in verde e bruno di uguale spessore’ (Fig. 2.12 and 14) The morphological variants include some closed forms and the carinated bowl exclusively associated with the bifid rim. The SEM-EDS analysis revealed different technologies (Reference Capelli, Arcifa, Bagnera, Cabella, Sacco, Testolini and WaksmanCapelli et al. in press; Capelli and D'Angelo Reference Capelli and D'Angelo1997). Another type of product from the mid eleventh century is a tin-overglazed ware known as ‘boli gialli’ (yellow dots). This ware is characterized by a specific style and morphologic panorama (Fig. 2.15). The analysis showed that the decoration is above the overall glaze, and the yellow dots are made with antimony (Sacco et al. in press; Testolini Reference Testolini2018, 192–94). Finally, a monochrome green/turquoise matt ware has been identified starting from the end of the tenth century. It is generally associated with hemispheric bowls (Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 350).

The picture of Palermitan tableware and lamps is increasingly clear and shows that the city was a well-established production centre, popular throughout Sicily. Most of the information comes from glazed wares, whose characteristics offer the possibility to propose reflexions about different topics such as technology and the evolution of decorative styles. Both themes show that Palermo workshops develop their language which is perfectly integrated in the Islamic Mediterranean context. Particularly interesting is the comparison with Ifrīqiya, whose tableware and lamps have many characteristics in common with the Palermitan ones. The evolution of this pottery is in many ways similar (Gragueb Chatti et al. Reference Gragueb Chatti, Sacco, Touihri, Hamrouni and El Bahi2019). From a chronological point of view, we have seen that the first Palermitan glazed products date back to the end of the ninth to the beginning of the tenth century, when the production of giallo di Palermo has been identified; however the giallo di Palermo does not seem to be the first type of glazed ware produced in Palermo. The morphological panorama documented in this first phase will continue to be produced throughout the Islamic period. During the first half of the tenth century the Palermitan decorative language, widespread in the second half of the tenth century, is developed. During this period one of the most successful wares is the ‘graticcio ware’, which has been recognized as starting in the mid tenth century. Major changes have been identified during the end of the tenth to the beginning of the eleventh century with the introduction of new morphologic (bifid rim, new carinated bowl variant, hemispheric bowls, flat plate) and decorative variants (anthropomorphic, splashed), as well as new wares (brown decoration under green glaze, ‘tipo D'Angelo’, monochrome green/turquoise matt glaze). Furthermore, imports coming from new regions have been identified in this period (Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 357–58). These changes have been linked with the reconfiguration of the Mediterranean commerce after the transfer of the Fatimid capital in Egypt in 973 AD (Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 350–57; on the reconfiguration of the markets, cf. Picard Reference Picard2015, 324–29).

Another turning point is the eleventh century. Palermo starts to lose its centrality in Sicily and the Mediterranean (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2012, 322–28) and, from a production point of view, a polycentric scenario is testified: the morphologic panorama of both Palermitan tableware and lamps changes, the decorative motifs become simpler and the introduction of the overglaze ware is documented.

Fabric group 2: table/storage/transport wares and others

The second group of Palermitan products was specialized in different functional types of pottery, including table, storage, transport and polyfunctional wares. These ceramics are usually plain, with grey or white salt surfaces.

Palermo amphorae products are known thanks to a group of pottery employed for lightening the vaults of some Norman (twelfth-century) buildings in Palermo (Ardizzone Reference Ardizzone1999, Reference Ardizzone2012; D'Angelo Reference D'Angelo1976). Just a few types have been attributed to the Islamic period (Arcifa and Lesnes Reference Arcifa, Lesnes and Démians D'Archimbaud1997; Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, D'Angelo, Pezzini, Sacco and Gelichi2012). Recent studies have finally recognized the Islamic period amphorae and now we begin to understand their typology and evolution over time (Sacco Reference Sacco2018b). Such studies led to anticipating the tenth century as the beginning of Palermitan amphorae export to the rest of Sicily and the central Mediterranean. This phenomenon was previously thought to date to the eleventh and twelfth century.

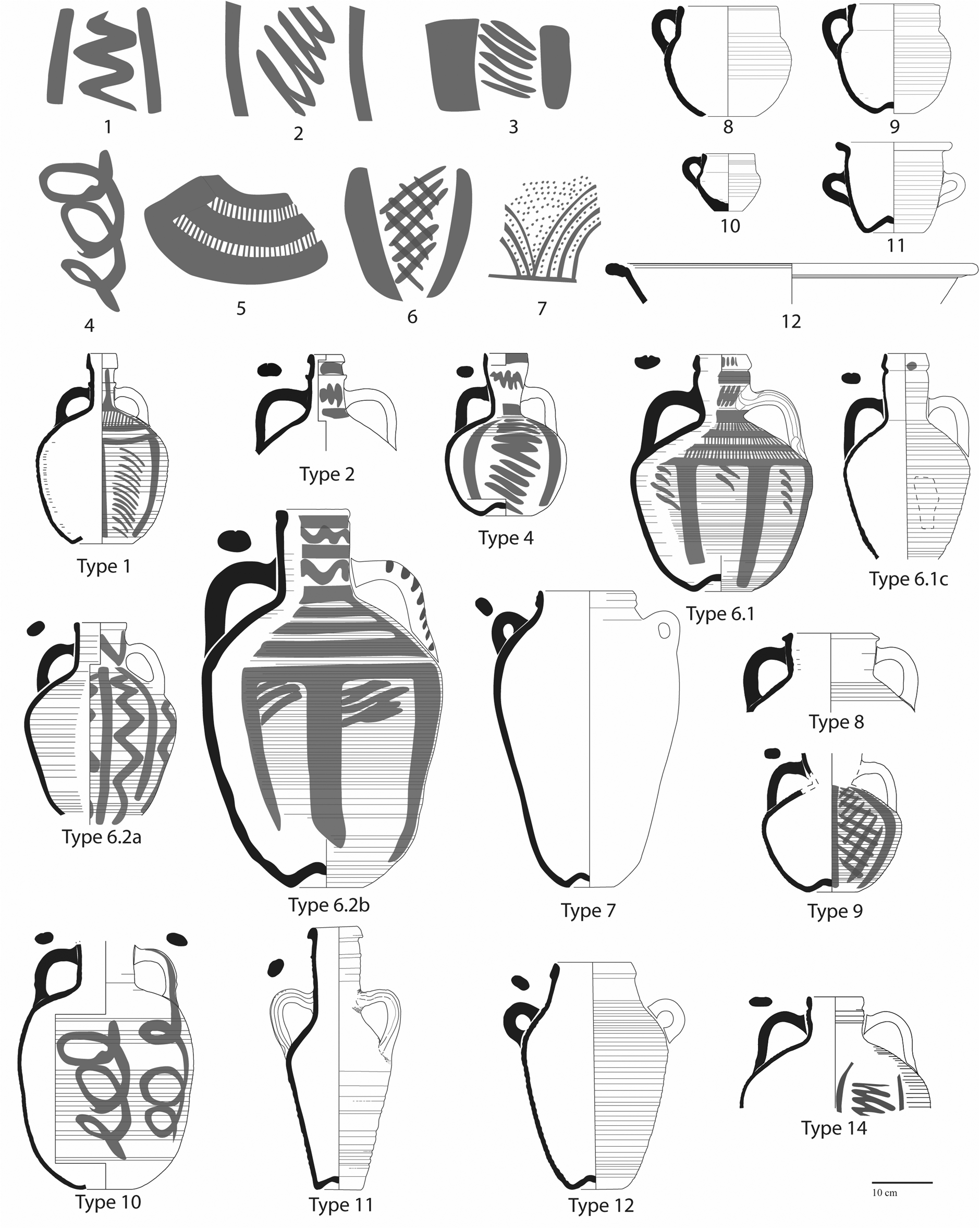

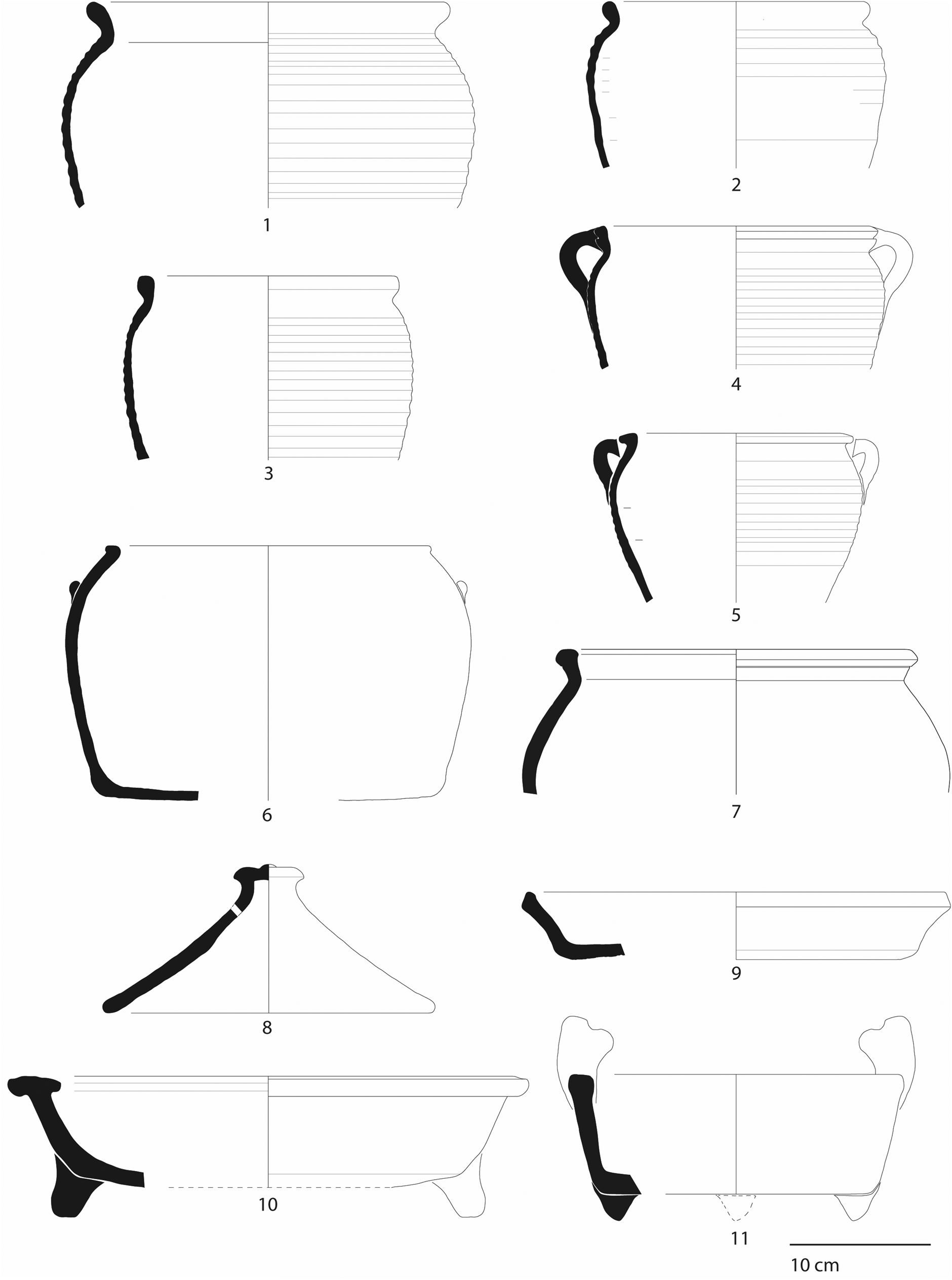

Palermo amphorae production has well-defined characteristics such as the cannelures (ribs), concave bases (flat in the smallest tableware versions) and grooved or simple handles. Almost all types of amphorae are also red-painted, and the different patterns are not specific to a particular morphologic type (Sacco Reference Sacco2018b). The evolution of the decorative motifs provides chronological indications. In the firsts assemblages (end of the ninth to the beginning of the tenth century) two main decorations have been documented: (1) loops (Fig. 3.4) and (2) vertical lines alternated with sinusoidal ones (Fig. 3.1). The loops motif found comparisons with eastern Sicily and southern Italy products (Arcifa and Ardizzone Reference Arcifa, Ardizzone and De Minicis2009; Raimondo Reference Raimondo2002, 519, Fig. 7.4) and runs out during the first half of the tenth century. Instead, the second motif undergoes an evolution: the sinusoidal line becomes more cursive (Fig. 3.2) during the first half of the tenth century, until around the mid-century it turns into a series of oblique lines alternated with large vertical lines (Fig. 3.3) (Arcifa and Lesnes Reference Arcifa, Lesnes and Démians D'Archimbaud1997, 407–408; Ardizzone Reference Ardizzone2012, 122–24; Sacco Reference Sacco2018b, 178–79). This last motif is the most typical of the Palermitan amphorae production and is documented until the eleventh century. Another common and typical motif from the mid-tenth to the mid eleventh century is located on the shoulder of some types (for example types 1 and 6, Fig. 3): horizontal large stripes separated by several short and thin vertical lines (Fig. 3.5). The other decorations are less common and it is still difficult to establish their duration over time. For example, the dots alternated with arched lines (Fig. 3.7) are documented in the first half of the tenth century, while the grid motif (Fig. 3.8) seems rather from the second half of the tenth century.

Figure 3. Palermitan fabric group 2.

From a morphological point of view, 12 main types have been produced in Palermo during the Islamic period. They display several morphological and size varieties and, from a functional point of view, they could have been employed for transport, storage or for table sets. In assemblages from the ninth to the first half of the tenth century, six main types have been recognized (Fig. 3 types 4, 6.2a, 7, 8, 10 and 14). Two of those (Fig. 3 types 8 and 14) disappear during the first half of the tenth century. As far as the others are concerned, we are not sure about types 6.2a and 10 (Fig. 3), while types 4 and 7 (Fig. 3) are widely documented up to the eleventh century. Starting from the mid tenth century, new typologies have been introduced (Fig. 3 types 1, 2, 6.1, 9, 11). The most diffused is type 6.1 (Fig. 3), an amphora shape testified for over a century whose body and neck tend to elongate during the eleventh century, while the concavity of the internal part of the rim is deeper (Fig. 3 type 6.1c). Type 11 (Fig. 3) is the sole Palermitan amphora not painted and is infrequent in Palermo assemblages. This amphora was, instead, employed as a container to export victuals, probably wine (Bramoullé et al. Reference Bramoullé, Richarté-Manfredi, Sacco and Garnier2017; Pisciotta and Garnier Reference Pisciotta and Garnier2018; Sacco Reference Sacco2019). Type 11 amphora is the main cargo of three Sicilian shipwrecks (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pisciotta, Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018b; Faccenna Reference Faccenna2006; Ferroni and Meucci Reference Ferroni and Meucci1996; Sacco Reference Sacco2019). The first examples of type 12 (Fig. 3) have been discovered at the end of the tenth century, but are more diffused during the eleventh century. The other amphorae (Fig. 3 types 1, 9 and 6.2b) are represented by few examples, and it is difficult to estimate their exact duration. Finally, it is worth noting that variants of types 7 and 12 are documented in twelfth-century assemblages, while it has been suggested that types 6.2b and 2 discovered in the Norman building vaults could be residuals (Sacco Reference Sacco2018b).

Another very common container in Palermitan assemblages is the handled jar (Fig. 3.8–9), maybe for the storage of food. This jar is very similar to amphorae products showing concave bases and cannelures, but it is never painted. It has usually a grey/greenish fabric and surface, certainly due to the type of firing, and its handles are never grooved. With some exceptions, we observe that usually the oldest handled jars (end of the ninth to the first half of the tenth century) have simple rims (Fig. 3.8); later the rims become progressively thicker and/or with a groove (Fig. 3.9), perhaps to host a lid.

Some other vessels are probably tableware. Few carinated bowls and cups (Fig. 3.10) have been identified. These have similar shapes to the handled jars, but they are smaller and painted. The decorative motifs are the same as the amphorae. Some small amphorae and jugs with filter known as ‘sovradipinta in bianco’ are, instead, characterized by a brown or red slip and white decoration (Arcifa Reference Arcifa1996, 468–70; Arcifa and Bagnera Reference Arcifa and Bagnera2018a, 22; Arcifa and Lesnes Reference Arcifa, Lesnes and Démians D'Archimbaud1997, 408; Sacco Reference Sacco2017, 356). These small amphorae, probably part of the table set, are the only Palermitan products to be characterized by a slip, and are documented starting from the end of the tenth to the beginning of the eleventh century.

This second Palermitan fabric group is completed by a series of other pottery which has the same surface characteristics compared to those discussed so far, but with different functions. During the Islamic period polyfunctional basins (Fig. 3.12), with a conic body, two handles and several variants of everted rims, have been documented, as well as some other vessels, interpreted as chamber pots (Fig. 3.11). During the tenth century, a few circular lamps were also produced within this second fabric group. The alfabeguer (pots for the cultivation of basil) and the conic and pierced formae for sugar production are rarest and come from the end of the tenth to the first half of the eleventh century assemblages. Finally, noria pots, which mark the introduction of new irrigation systems, have been found since the end of the ninth century up to the eleventh century assemblages. Their morphology remain unchanged, while this same shape found in particular contexts could sometimes have a different function (Sacco Reference Sacco2019).

Cooking pots

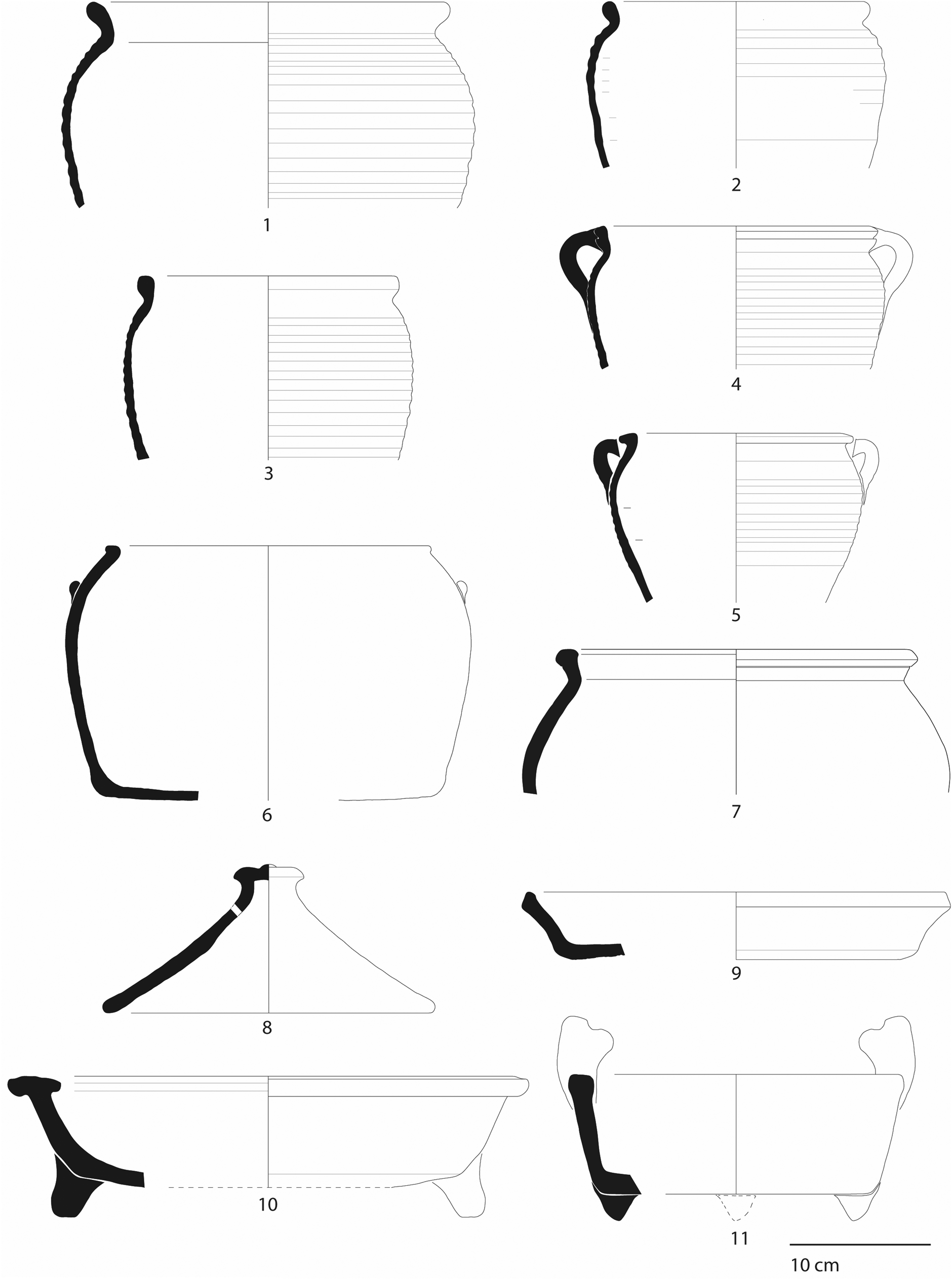

The informative potentialities of Palermitan cooking pots have only recently sparked the interest of scholars. This delay in cooking wares studies is the reason why it is still difficult to fully understand the entire production of this functional category. The most widespread form is the olla (a closed, globular cooking pot usually with a rounded base but sometimes with a flat base) characterized by thin ribbed walls, with surfaces often covered by a thin dark clay film. From a macroscopic point of view, as we already have seen, two main Palermitan fabrics have been recognized, associated with the same morphologic panorama (cf. supra). The evolution of Palermitan ollae over time concerns mostly the rims and the appearance of handles. In the earliest Islamic phases (end of the ninth to the beginning of the tenth century) the rim is everted, developed and simple (Fig. 4.1). In lesser quantity, the ollae with a shorter everted simple rim are documented (Fig. 4.2). During the first half of the tenth century, a turnaround between the two variants is observed with a progressive drastic decrease of the first type. In later contexts (second half of the tenth century) a first element to assess is the appearance of handles, which therefore indicate a change in the prehension system and so probably some aspects of the cooking techniques.When the handles changed also the rims evolved, with the presence, in the second half of the tenth century, of quadrangular section rims (Fig. 4.3). During this period, the olla with a rim characterized by an incision outside (Fig. 4.4), and sometimes by a plastic decoration, appears, even if it has the greatest diffusion between the end of the tenth and the beginning of the eleventh century. Finally, in the first half of the eleventh century, the olla with triangular section rim (Fig. 4.5), which is flat on the top, is documented (Pezzini and Sacco Reference Pezzini, Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018). After the mid eleventh century, we do not know exactly what happens to Palermitan ollae production, beyond assuming a progressive decrease of production. We start to see the arrival already during the eleventh century of the first glazed cooking pots coming from north-east Sicily, which achieve success during the twelfth century.

Figure 4. Palermitan cooking pots.

It is worth mentioning two other cooking pot types, even if we are not sure they were produced in the Palermo area. The first one is the cylindric pot with an inturned rim and flat base, probably made with the coil technique, finished on the slow wheel and characterized by a Numidic Flysch clay (Fig. 4.6). This type of pottery is constantly documented from the late ninth to the eleventh century, and it is not subjected to morphological changes. Other similar pots, but with different fabrics, have been documented in Sicily, which suggests that the cooking pots with this shape documented in Palermo could be a local production. The second cooking pot group is the so-called ‘macrogruppo A’ (macro group A), fired in a half-reducing atmosphere with a fabric characterized by a grey core that changes into orange/pink towards the surface. It is typical of ollae with smooth surfaces and vertical or everted rims (Fig. 4.7). Such ollae are not attested beyond the beginning of the tenth century (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Ardizzone and Nef2014, 211–12). This early chronology, as well as the morphologic comparisons with products from eastern Sicily (which remains in Byzantine hands for a longer period during the tenth century), allows us to suppose a technological continuity with a Byzantine tradition (Ardizzone et al. Reference Ardizzone, Pezzini, Sacco, Ardizzone and Nef2014, 215; Pezzini and Sacco Reference Pezzini, Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018, 349–52).

The set of Palermitan kitchenware is also composed of baking pans (Fig. 4.9) and lids (conic with holes and dome-shaped) (Fig. 4.8). The fabric of these vessels is similar to that of the Palermitan amphorae but in many cases is coarser and fired differently (cf. supra). From a morphological point of view, baking pans and lids are quite conservative, but at the same time it is worth mentioning the high variability of some details (most of all rims). Both elements make it difficult to formulate hypotheses on their evolution through the ninth to eleventh centuries.

Finally, we must mention the so-called ‘braziers’, whose function has recently been called into question. The use of these braziers to support cooking pots with convex bases has been suggested, instead of the classic interpretation of embers holders (Pezzini and Sacco Reference Pezzini, Sacco and Yenişehirlioğlu2018). In this case, both fabric and surface treatments are often similar to the amphorae ones, and an incised decoration on the internal base surface is present. Furthermore, the examples of the end of the ninth to the first half of the tenth century do not have the vertical handles (Fig. 4.10) which, instead, characterize the later variants (second half of the tenth to the eleventh century) (Fig. 4.11).

Conclusion

The Islamic conquest of Palermo and the new role played as the capital of Sicily have major consequences, including on pottery production. New techniques, shapes and decorations appeared in the ceramics sets, which are the sign of a change in the population habits. The percentage ratio between local and imported products (Sacco Reference Sacco2017, Reference Sacco2018b) shows that during the Islamic period Palermo was a self-sufficient city. In fact, the arrival of imports, although constant, were very few. Vice versa, the volume of pottery produced in Palermo workshops testifies that, in addition to satisfying the capital's demand, it also met the island's needs, at least during the tenth century. The general panorama of pottery production observed during the end of the ninth and the beginning of the tenth century assemblages does not seem to change significantly until the first half of the eleventh century. At the same time, the evolution of a series of morphological details, decorative motifs and the introduction of new amphorae variants have allowed us to establish the chrono-typology of the Palermitan products.

Overall, the set of forms, fabrics and decorations make Islamic Palermitan products easily recognizable. In particular, the amphorae characteristics could be considered a sort of brand, which makes Palermo products immediately recognizable outside the city and the island. It will be important in the future to multiply systematic studies on Palermitan assemblages to clarify chrono-typological aspects, and to better understand the reasons and the dynamics that brought changes in Palermitan pottery over time.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Palermo for the access to pottery during these years of research. I am deeply grateful to Veronica Testolini for the revision of the English and her advice to improve the text.