This paper presents four previously unpublished inscriptions recently found in ancient Cyrenaica, namely in the chora east and south-east of Cyrene (Figure 1). Three of them (nos 1, 2 and 3) come from tombs destroyed in the course of uncontrolled development and one (no. 4) is a chance find.Footnote 1

Figure 1. Map of central Cyrenaica (from Laronde Reference Laronde1987, 286, Fig. 87).

1. Funerary stele with verse-inscription from Mgarnes

The ancient village of Mgarnes lies about 13 km to the east of the city of Cyrene (Figure 2). The place has been mentioned many times by ancient travellers since the beginning of the nineteenth century. Modern archaeologists and historians have described its remains, some of them well-preserved, dated from the Hellenistic period down to the Byzantine period, and also two built tombs, just to the north-east of the settlement, one circular tomb and one temple-tomb.Footnote 2

Figure 2. Main places mentioned in the text. Outlined in blue is the wadi al Mahajjah (background image: Google Earth).

The settlement is enclosed inside a fence for protection, but no excavations have been carried out on this site.Footnote 3 Situated on the edge of the upper escarpment, at a slightly higher altitude than the plateau which extends to the south, the settlement of Mgarnes is also linked with the intermediate plateau (the so-called ‘Hills’) through the nearest wadi to the west. It was evidently an important settlement with good agricultural potential, situated on the ancient road from Cyrene towards Tart, Lamludah and Al Qubbah, whereas the modern road runs about 0.8 km away to the south. In 2015, five small funerary busts were brought to the Department of Antiquities at Shahat by a Libyan citizen. After some time, Hamid Alshareef, then director of the Department of Archaeological Research, was able to visit the place, distant c. 1.5 km from the village to the north-east, and he could only photograph the remains of a large tomb, which had been destroyed. Many pieces had been moved with a bulldozer and the tomb was overturned. Without further investigations, it is not even possible to decide whether the tomb was built or rock-cut. However, some features of the fragments lying upside down permit dating its earliest phase to the Hellenistic period, some blocks still showing a Doric frieze with metopes and triglyphs. In the Roman period some metopes were chiselled away, allowing placement for small funerary busts similar to those presented to the Department.Footnote 4 If some of the busts are really related to that tomb, they provide a more precise date for the Roman phase, which might have lasted several generations during the first century and the first half of the second century AD.Footnote 5 The tomb has thus been in use for a rather long time. Beside those distressing remains, Alshareef discovered an inscribed stele lying on the ground and was able to take good photographs of it. In publishing it, we hope to preserve it from total loss.

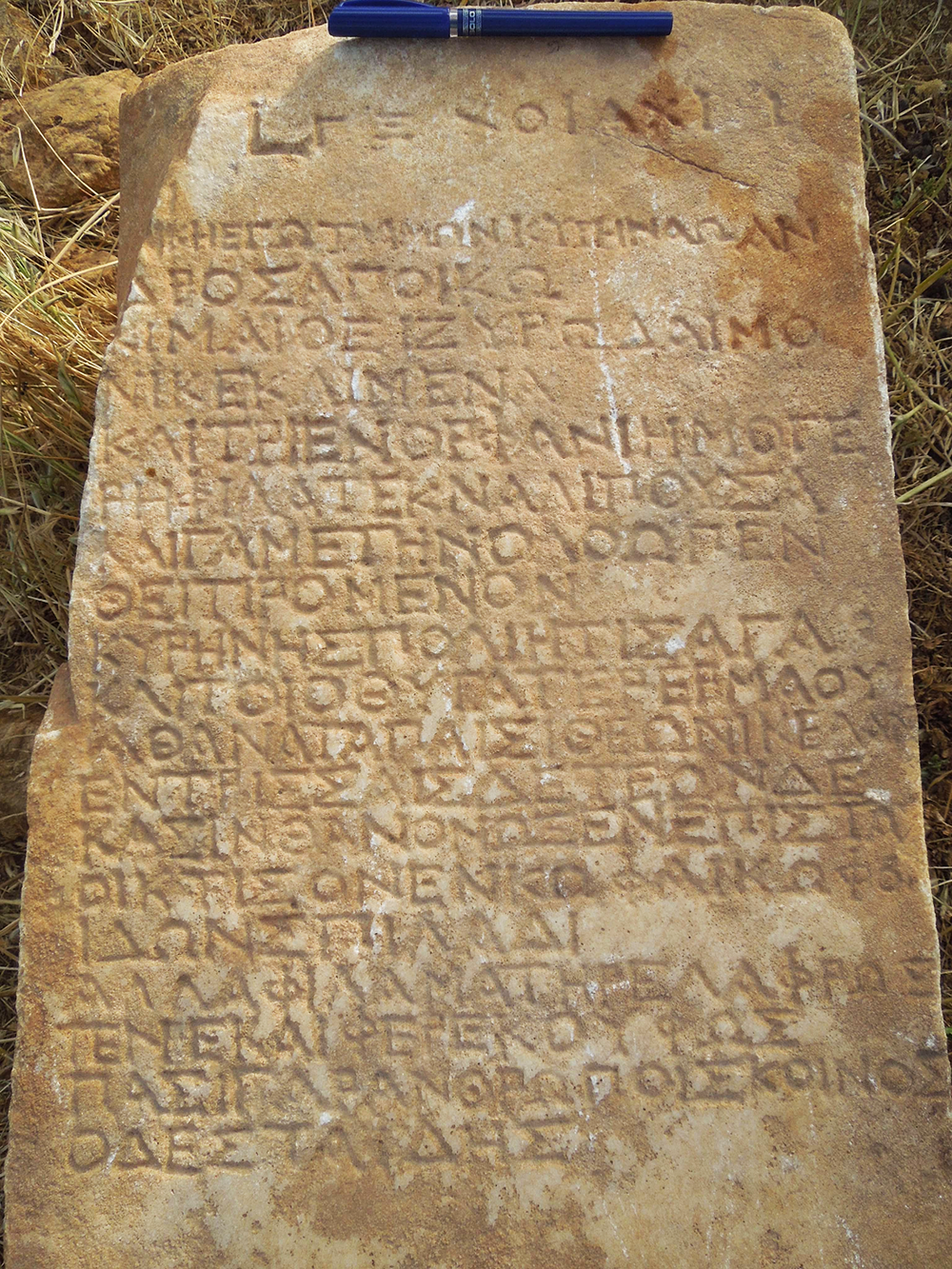

The stele, made of local limestone, is still reddish from the earth. The fresh colours of the stele (h.: 107 cm; w.: 35 cm; d.: 24 cm) (Figure 3) reveal that it has not been exposed to air and rain for a long time and was recently unearthed. The photo shows that it was, as usual, slightly slanting. The stele is plain, without any ornament or moulding. The inscription is very well-preserved and nearly all letters are easy to read. With each line beginning at left after a small margin, the break of the upper left corner did not affect the inscription. The stone is also slightly split off on its right edge at lines 14 (where the Σ however may be seen) and 15 (where only a small dot is preserved below, after the O). The letters are carefully cut.

LΓΞΧΟΙΑΧΙΙ (ἔτους) γξ´ Χοιαχι ι´

ΝΙΚΗΕΓΩΤΛΗΜΩΝΚΥΡΗΝΑΩΑΝ Νίκη ἐγὼ τλήμων Κυρηνάω ἀν-

ΔΡΟΣΑΠΟΙΚΩ δρὸς ἀποίκω

ΚΙΜΑΙΟΕΙΖΥΡΩΔΑΙΜΟ κῖμαι οɛἰζυρῷ δαίμο-

ΝΙΚΕΚΛΙΜΕΝΑ 5 νι κɛκλιμένα

ΚΑΙΤΡΙΕΝΘΕΦΑΝΙΗΜΟΓΕ καὶ τρι᾿ ἔνθ᾿ ἐφάν{ι}η μογɛ-

ΡΗΦΙΛΑΤΕΚΝΑΛΙΠΟΥΣΑ ρὴ φίλα τέκνα λιποῦσα

ΚΑΙΓΑΜΕΤΗΝΟΛΟΩΠΕΝ καὶ γαμέτην ὀλοῷ πέν-

ΘΕΙΤΙΡΟΜΕΝΟΝ θɛι τιρόμɛνον,

ΚΥΡΗΝΗΣΠΟΛΙΗΤΙΣΑΓΑ 10 Κυρήνης πολιήτις ἀγα-

ΚΛΙΤΟΙΟΘΥΓΑΤΕΡΕΡΜΑΟΥ κλίτοιο θυγάτɛρ Ἑρμάου

ΑΘΑΝΑΤΑΠΑΙΣΙΘΕΩΝΙΚΕΛΑ̣ ἀθανάτα, παισὶ θɛῶν ἰκέλα·

ΕΝΤΡΙΣΣΑΙΣΔΕΤΕΩΝΔΕ ἐν τρίσσαις δ´ ἐτέων δɛ-

ΚΑΣΙΝΘΑΝΟΝΩΞ ΕΝΕΠΙΣΤΑΣ κάσιν θάνον· ὦ ξέν´, ἐπίστας

ΟΙΚΤΙΣΟΝΕΝΚΩΦΑΙΚΩΦΟ.15 οἰκτίσον ἐν κώφαι κῶφο[ς]

ΙΔΩΝΣΠΙΛΑΔΙ ἰδὼν σπιλάδι·

ΑΛΛΑΦΙΛΑΜΑΤΗΡΕΛΑΦΡΩΣ ἀλλὰ, φίλα μάτηρ, ἐλαφρῶς

ΤΕΝΕΚΑΙΦΕΡΕΚΟΥΦΩΣ τ´ἐνέκαι φέρɛ κούφως·

ΠΑΣΙΓΑΡΑΝΘΡΩΠΟΙΣΚΟΙΝΟΣ πᾶσι γὰρ ἀνθρώποις κοῖνος

ΟΔΕΣΤΑΙΔΗΣ 20 ὅδ’ ἔστ´ Ἀΐδης

ΝΙΚΗΕΡΜΑΙΟΥ Νίκη Ἑρμαίου

L Λ (ἐτῶν) λ᾿

Translation:

Year 63, Khoiaki 10th.

I unfortunate Nike, wife of a Cyrenaean colonist, lie, laid down by a dreary deity, and I was seen sadly leaving here three dear children and a husband distressed by deadly grief, I a citizen of Cyrene, I immortal, equal to divine children, daughter of the famous Hermaios, and I died within three tens of years. Stranger, stop and have pity, having a dumb look at me in this dumb stone. And you, dear mother, please, light-hearted, bear it lightly, for this Hades is common to all humans.

Figure 3. Inscription no. 1, view (photo H. Alshareef).

Nike daughter of Hermaios, 30 years old.

The inscription is made of three parts, clearly separated by spaces on the face. On one line in larger letters, we have the date (Figure 4); after a space, the core of the inscription, running on 19 lines, is verse; below a larger space, the name of the dead person and her age. The first line of the verse-text is cut in smaller letters; having cut it, the stonecutter probably found out that anyway he could not have a full verse-line on one line of script and decided to display one verse on two lines, being thus able to produce larger letters. The local limestone allowed the cutting of deep letters, which are quite regular, with classical forms such as Ε, Σ, Ω. This lettering is rather similar to that of IG Cyrenaica Verse 007, which was attributed to the second half of the first century AD only on the basis of the lettering. In fact, we have a date at the top of this inscription: year 63. Referring to the Actian era, this means AD 32/33. More precisely, the 10th of month Khoiak is in modern terms October 26. The Egyptian months were in use in Cyrenaica since the time of the Ptolemies and were kept during the Roman period, as we may see in the numerous epitaphs at Cyrene, Ptolemais and especially at Taucheira. The siglum L, an abbreviation for ‘year’, used for the date and for the age of the dead, is also of Egyptian origin.

Figure 4. Inscription no. 1, lines 1–20 (photo H. Alshareef).

Contrasting with the classical lettering and the traditional ideas developed in the poem, some spellings are no longer classical. For instance, EI is written for I in οɛἰζυρῷ and I for EI in κῖμαι, τιρόμɛνον, ἀγακλίτοιο, E for H in θυγάτɛρ. Furthermore, the I of the diphthong AI is lost before another vowel: Κυρηνάω, Ἑρμάου. Those features are well-known in all parts of the Greek-speaking world and prefigurate the future evolution of the language, but it is not usual to find them in carefully cut verse-inscriptions. The fact that the monument was erected, and perhaps cut, in the countryside might explain this. On the whole, only one word should be corrected, because no other solution emerges: ἐφάν{ι}η has a superfluous iota.

In spite of the neglected spellings, this tombstone shows a rather wealthy family and the text itself was composed by a very well-educated person. An ordinary funerary inscription would be sufficient with (ἔτους) γξ´ Χοιαχι ι´ Νίκη Ἑρμαίου (ἐτῶν) λ᾿.

Here, a piece of verse, inserted in the middle of the usual information, allows us to add some facts: mention of her husband, whose name is not given, and further details about her life, that she left three children and that her mother was still alive.

As a funerary poem, the verses may be presented as follows:

They are made of five pairs named ‘elegiac couplets’: one hexameter and one pentameter each. The verse is metrically quite regular. The caesurae of the hexameters (penthemimeris at v. 1, 5, 9; hephthemimeris at v. 3, 7)Footnote 6 all sustain the syntactic divisions.

The language shows a mixture usual in funerary verse:

a) A mixture of dialectal and koine forms: endings in -ω instead of -ου (Κυρηνάω, ἀποίκω) contrasting with Ἑρμάου; dialectal A in κɛκλιμένα, ἀθανάτα, ἰκέλα, κώφα, φίλα μάτηρ, contrasting with H in τλήμων, Κυρήνης, μογɛρὴ, γαμέτην, πολιήτις, Ἀΐδης. The mixture happens even within one word in Κυρηνάω. The very name of the woman has the non-dialectal ending: Νίκη.

b) Poetic features: in the vocabulary we find οἰζυρός δαίμων, μογɛρός, ὀλοός, ἀγάκλɛιτος, ἴκɛλος; a verbal form of past without augment θάνον; τɛ ‘and’ is used here to relate ἐλαφρῶς and κούφως, but awkwardly placed. Rare words are often used in this sort of poem, such as here σπιλάς, already used in Homer with the meaning ‘rock over which the sea dashes, reef’. With this proper meaning the adjective κῶφος ‘dumb, mute’ would make no sense; we should thus take it as a metaphor for the tombstone. There are examples of the same meaning of σπιλάς in several funerary verses of various regions.Footnote 7 The idea of a ‘dumb’ or ‘mute’ tombstone is also well attested. Furthermore, with the adjective κῶφος, twice mentioned here, both the tombstone and the passer-by are termed ‘dumb’. There is a very similar instance in a contemporary verse-inscription from Mysia, in Asia Minor, where the mother of a dead man is said to be ‘pouring dumb tears on dumb tomb-stones’.Footnote 8

In such poems, called ‘epigrams’, the main pieces of information are scattered in the text with complicated formulation. We find here a combination of the usual elements of funerary epigrams, such as the sadness of the family, the address to the passer-by, who will read the epitaph, and the idea that everyone should die. Nike herself is the speaking person in the whole poem. Up to v. 7, she is speaking about herself with the verbs in the first person (κɛῖμαι, θάνον). Then she is briefly addressing any person who will in the future pass by her tomb (ὦ ξένɛ). Eventually, with another address, she is speaking to her mother with comforting words. In the last sentence, Hades is both the god of the netherworld and death itself. Playing with his name Aides, which resembles ‘not (a) - seeing (id-)’ it is also a play on the use of the verb ἰδών just above.

Νίκη, which is the name for ‘Victory’, is rather rare as a personal name. In Cyrenaica we have a possible instance in a funerary inscription of Ptolemais, only known from Pacho's copy in 1825.Footnote 9 But many names, with one or two stems, built on νίκη are known from Cyrenaica. The most frequent is the masculine Νίκαιος, also often spelled Νɛίκαιος. As to the father's name, Ἑρμαῖος, it is well known in all regions of Greece; although not very frequent in Cyrenaica, it is attested there from the fifth century BC to the first century AD.

As a historical testimony, this inscription is also very interesting. The political status of the family is precisely mentioned. The woman was a polietis, a ‘she-citizen’. This does not mean that she took part personally in the political life of the city, although the role of women of high-rank families did increase in the Roman period. It may simply mean that her father was a full citizen of Cyrene, and a ‘famous’ one, as the text tells us. Her husband is called apoikos, which means ‘colonist’. This word, in inscriptions and used by ancient historians, refers to the first Greek settlers who founded Cyrene about 630 BC. A possible explanation would be that her husband belonged to a family claiming direct descent from the first settlers. Surprisingly, his name is not even mentioned and his occupation is not otherwise stressed. It would have seemed sufficient to relate him to one of the most ancient families of Cyrene. One instance of this inclination for relating to the origins of the city is another epigram, where a priest named Aristoteles is celebrated for having rebuilt Apollo's temple, built for the first time nine centuries earlier by his homonymous predecessor, the founder Battos Aristoteles.Footnote 10

A distinctive feature of the Cyrenaean elite during the Imperial period is the growing trend for self-celebration; choosing the name Battos for the richer families’ sons was therefore a sign of social differentiation. Several examples are given by inscriptions, particularly an epitaph from the Cyrene necropolis which mentions the names of the deceased's ancestors over seven generations, the most ancient one being called Aladdeir son of Battos. Aladdeir reminds of Αλαζɛιρ, king of Barca in the fifth century BC and step-father of king Arkesilas IV of Cyrene mentioned by Herodotus (Histories 4.164), whereas Battos refers to the mythical founder of Cyrene.Footnote 11 The local aristocrats were thus emphasizing their role in the glorious history of their city, still called ‘city of Battos’ in an epigram whose date is very close to the one published here (IG Cyrenaica Verse 027). It is also worth noting that Battos was supposedly depicted on the column capitals in the House of Jason Magnus in second-century Cyrene (Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975, 326 with Fig. 339). This narrow group of aristocrats claimed the city's identity for their self-glorification, but we read for the first time, in the Mgarnes epigram, that a man is said to be an apoikos, as if his own actions had refounded Cyrene again. Another explanation might come to mind, which however seems anachronistic: the Greek word ἄποικος is also the translation of the Latin word colonus and is used for people to whom a plot was assigned by the Roman authority. However, at the date of the inscription, there is not yet any trace of such a process. The allotment of plots to new colonists is known only after the Jewish revolt of AD 117 and the date of this inscription is nearly one century earlier.

Anyhow, this is an important piece of information about the village of Mgarnes. From there, we already knew a fragmentary decree of the first century BC,Footnote 12 which provides much interesting information about the life of the village.Footnote 13 In that text, a man whose name is lost is honoured for his benefaction. The general formulation is very similar to honorary decrees from cities such as Cyrene, Berenike and Arsinoe-Taucheira: the authorities are granting some privileges to a good citizen and publishing their decision in order to encourage others to follow suit. The privileges are of three types: (a) to be inscribed in the list of past priests;Footnote 14 (b) that his well-doing will be inscribed in a public space; (c) to be free of some duties toward the community. Those guidelines are adapted to the context: (a) the priests among whom he will be inscribed are not those of Apollo, as at Cyrene and Apollonia, but those of Dionysos, a deity more appropriate to an agricultural community; (b) his name will be inscribed, if he wants, on the public granary and not, as in large cities, ‘in the most prominent place of the city’, i.e. usually on the agora or in another public building; (c) the duties he is exempted from are normally ‘due to the kome’ and are probably some sort of work done in common rather than taxes. We are namely not in a city, but in a kome, a ‘village’, a rural community, very well organized, with cults, common activities and even officers. In the latters’ title, polianomoi ‘those who manage the polis’, the setting of a political organization is implicit.Footnote 15 At Mgarnes, the polianomoi are in charge of inscribing the decree (psaphisma, same word as in cities) and keep it ‘in full view’ in the public archive.Footnote 16 Beside and not far away from a large city like Cyrene, this kome had a life of its own. Living either in the city or in the country, Nike's father and husband owned large farms and prestigious tombs were tokens of their wealthy life. Their way of life seems to some degree similar to that of the aristocratic Athenians, who played an important role in the political life at Athens and lived in the countryside estates of their demes, the resources of which allowed an affluent lifestyle.

We know from the new funerary inscription that Mgarnes’ territory extended for some kilometres. Unfortunately, the invaluable testimony of the decree has no parallel in other villages of the chora. However, on the intermediate plateau as well as on the upper one, many sites, now under threat, are or were recently visible. Even if smaller than Mgarnes and limited to large farms with a fortified building (pyrgos), they left remains, the most lasting ones often being the tombs nearby. Surrounded by basins of terra rossa, watered by springs, they offered good resources for life, while outcrops of the manageable local limestone allowed them to build for the afterlife as well.

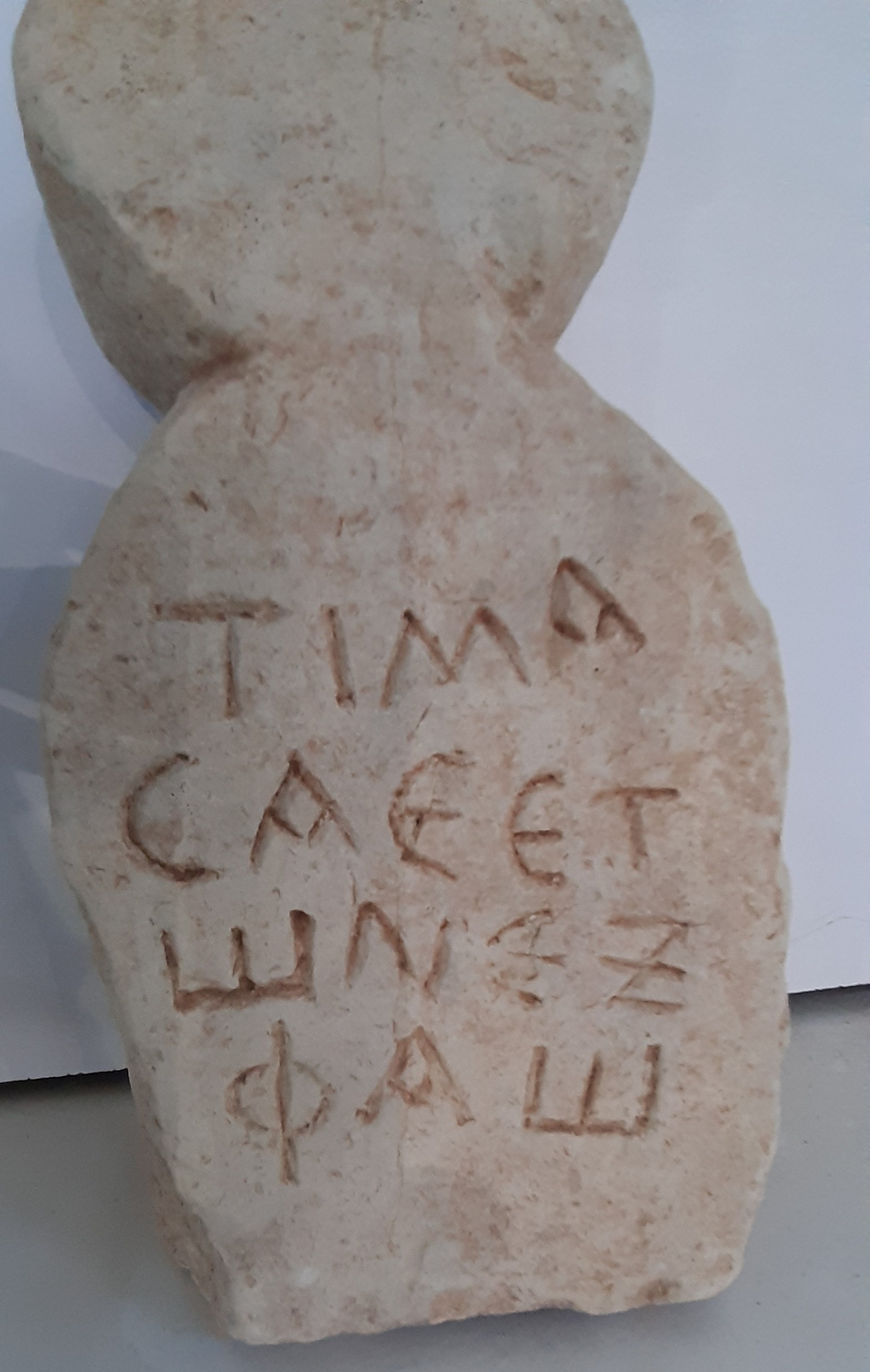

2. An inscribed anthropomorphic stela from Mgarnes

Another funerary stele (Figure 5) was found in the same tomb as the previous inscription near Mgarnes. It belongs to the group of so-called ‘anthropomorphic funerary steles’ studied both for their sculptural aspect (Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1987) and for the inscriptions found on them (Bacchielli and Reynolds Reference Bacchielli and Reynolds1987). The top of those middle-sized steles, made out of local limestone, has a shape representing more or less the upper part of a human body. The new item offers a head well detached from the body, whereas on some others only three slight protuberances, the central one larger than the two others, suggest a head and shoulders. Moreover, for this new item the word ‘stele’ is perhaps not quite fitting, as it consists of a head and a body without shoulders. This outline is suggestive enough and there was no need here for any design depicting the face on the ‘head’. Another feature of the new item is that the inscription engraved on the body is deeply and rather carefully cut, which contrasts with the very raw lettering and spelling of many other anthropomorphic steles.

Figure 5. Inscription no. 2 (photo H. Alshareef).

The lettering, with dropped-bar alpha, lunate epsilon and sigma, square omega, could be attributed to the second century AD. The letters were rubricated. We read as follows:

-

Τιμᾶ-

-

σα {ἐ(τῶν)} ἐτ-

-

ῶν ɛξ´

-

Φάω

Translation: Timassa, 65 years old, daughter of Phaos.

The usual elements of a funerary inscription in Cyrenaica in the Roman period are the name of the dead, his/her father's name and age. On anthropomorphic steles the date of death is often omitted, whereas other funerary inscriptions do mention the year, month and day.Footnote 17 The age was awkwardly cut. We find an E, which sometimes occurs as the abbreviation of the word ‘year’ (for instance IRCyr2020 P.292). The stonecutter was probably overzealous and added the word ἐτῶν spelled in full. This brings to mind a few instances where we read ἐτῶν spelled in full and thereafter the siglum L, which has the same meaning (IRCyr2020 M.164).

In the name Τιμᾶσσα the spelling with only one sigma is very common at this date. The occurrences of Timassa are currently increasing. At Cyrene, two women bearing that name are mentioned in the first century BC or AD: one was a priestess of Artemis (IRCyr2020 C.130. 22) and another one was buried in a rock-cut tomb of the Southern necropolis (IRCyr2020 C.545). Two further instances from the countryside around Cyrene have just been published as IRCyr2020 C.754 and M.216. This name, meaning ‘deserving honour’, was chosen in families of a rather high standard. Although not very common in the rest of the Greek world, it is well-formed and its origin may be found in the Homeric vocabulary (Le Feuvre Reference Le Feuvre, Alonso Déniz, Dubois, Le Feuvre and Minon2017, 496–504).

The father's name, oddly placed here after Timassa's age, also deserves commentary. Two priests of Apollo bore that name, Phaos son of Klearchos c. AD 20 (IRCyr2020 C.48.4; C.416) and Phaos son of Karnedas c. AD 35 (IRCyr2020 C.48.14; perhaps the same IRCyr2020 C.781).Footnote 18 The latter has been identified with Phaos, father of a priestess of Hera, Fabia Kydimacha, in charge in AD 61/62 (IRCyr2020 C.103.34–35). Also during the first century AD, an ephebe, son of Phaos and grandson of another Phaos scratched his name onto a base dedicated to Hermes and Heracles and assumed to have stood in the gymnasium (IRCyr2020 C.56.6).Footnote 19 Later on, under Hadrianus or Antoninus, a man named Ti(berios) Claudios Phaos (IRCyr2020 C.414.10) is probably the same as the priest Ti(berios) Claudios Phaos Titianos (IRCyr2020 C.396). The name did not disappear from the region, as another Phaos is mentioned, after his death, by Synesios in a letter dated AD 412 (Epistulae 61; Roques Reference Roques1989, 230–31). With this form, the name is attested only in Cyrenaica, whereas older forms are known from Cyprus and Crete (Masson Reference Masson1976, 81).

On the whole, father's and daughter's names were fashionable in families of high rank in the society of Cyrene. This is in contrast with the type of funerary monument. Anthropomorphic steles were typically produced in the countryside, connected with poorly literate circles. It has been argued (Bacchielli Reference Bacchielli1987) that the sculptural features of this group of monuments reveal a mixed Libyan–Greek culture. At least, their provenance is rural. Amongst the 47 items collected by Bacchielli and Reynolds (Reference Bacchielli and Reynolds1987), only one (no. 28) has been found in a necropolis of Cyrene and one perhaps (no. 29) in the necropolis of Apollonia. Eight come from rural sites around Taucheira and five from the vicinity of Ptolemais. Some have been found at al Haniyah and al Faidiyah, but the largest number comes from the eastern part, either the upper plateau east of Cyrene, mainly Lamludah (20 of them), or the middle plateau (Siret Sidi Massaoud), or the coast east of Apollonia: of the two items from near Derna in the former collection, 13 more have been added from the cemetery at Karsa, ancient Chersis, 20 km westward on the coast (Mohamed and Reynolds Reference Mohamed and Reynolds1995). The new stele is the first one found at Mgarnes. Although it was, as stated above, more carefully made and inscribed than other similar items, it is the first time that one is found in a given context together with a traditional stele bearing a verse-inscription. It is not plausible that Timassa daughter of Phaos belonged to the same family as the priests and priestesses mentioned above. However, her funerary stele testifies to an elaborated mixture of Greek and Libyan traditions.

3. A funerary inscription for two women

The inscription lies on a slab of white marble whose lower right corner is missing and the left side broken off (h.: 45 cm; w.: 61 cm; d.: 3 cm) (Figure 6). It was found as a result of random construction in the intermediary plateau in an area which may be defined in alignment with tomb N1 of Cyrene's Northern necropolis, but outside the necropolis proper. It was probably related to some settlement along the modern road to the hospital. The slab seems too small to have been a closure for a loculus; its dimensions would rather fit a niche, such as the one in room F of the ‘tomba dei Carboncini’ in the Southern necropolis of Cyrene (Cinalli Reference Cinalli, Benefiel and Keegan2016, 206) and the numerous niches in tombs at Tokra (Elhaddar Reference Elhaddar2018, 271–74). It may also have been fixed over a funerary stele or used as a panel for a sarcophagus.Footnote 20 The slab bears the following text:

-

Κορνηλία Ἰουλία

-

(ἐτῶν) λα´

-

Κορνηλία Λαυδίκη

-

(ἐτῶν) θ´

Translation: Cornelia Iulia, 31 years old. Cornelia Laudike, 9 years old.

Figure 6. Inscription no. 3 (photo H. Alshareef).

The two names, preserved in their entirety, may have been written by two different stonecutters, as shown by the shape of the kappas, although the differences are slight. The second name may have been inscribed a little later in a more awkward manner, perhaps when the panel was already fixed to the support, which could explain how the engraving became more difficult for the stonecutter. Space was lacking at the end of line 3 and therefore the last letters of the name Λαυδίκη are smaller and narrower. Palaeography and the name Ἰουλία both point to a date in the first century AD for this funerary inscription. As the two names seem to have been engraved at a rather close date, we can guess that we are dealing with a mother and her daughter, particularly since they bear the same nomen.

The name Cornelia is interesting, because it refers to the gens Cornelia, a Roman family who had connexions with Cyrenaica since the Republican era. Publius Cornelius Lentulus was sent to Cyrenaica as ambassador of Rome during the second century BC. In 75 or 74 BC, Publius Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus was appointed quaestor of Cyrenaica and was the first Roman magistrate in the region (Sallust, Histories, 2.41–42). Later on, in 67 BC, his brother Cnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus came to Cyrenaica as legate of Pompey and the acts he accomplished are known from the epigraphical record (Reynolds Reference Reynolds1962). The presence of the Cornelii Lentuli at Cyrene during the second and first centuries BC explain the close ties between this Roman family and the cities of Cyrenaica.

However, Cornelii are pretty rare in the region: one Κορνήλιος was the father of Καρνήδας, an archon of the Jewish community in Berenike (IRCyr2020 B.45.11). At Cyrene, two ephebes from the time of Marcus Aurelius bear the nomen Cornelius (IRCyr2020 C.143.b.24 and 26). We also know of a Cornelia Polla in a Latin epitaph at Ptolemais (IRCyr2020 P.390). The Cornelii of Cyrenaica may be families who received Roman citizenship from the Republican Cornelii, but they may have been descendants from Italian merchants as well, or have been granted citizenship from another intermediary such as the Tiberian proconsul Cornelius Lupus. It is worth noting that Iulii – the second name of the first woman is Ἰουλία – are also very rare in Cyrenaica.

The second woman has a Greek name used as cognomen in the Latin onomastic formula. It is the first epigraphic occurrence in Cyrenaica of this name and its form belongs to the koine. The first syllable Λαυ- is not common in the region, as the names in Λᾱο- normally became Λᾱ- in the local dialect. However, the name was famous in Cyrenaica; the daughter of the first king Battos, whose story was told by Herodotus (Histories, 2.181), bore the name Λαδίκα. In the Roman period, there was another good reason for choosing this name, borne by several women and queens in the Seleucid family and thus fashionable since the end of the Hellenistic period in the same way as Arsinoe and Berenice.

4. A boundary inscription and the Roman limes of Cyrenaica

On 11 April 2020, a Libyan citizen, Al-Ferjani Shuaib, posted photographs of a Latin inscription on his Facebook page, inquiring about what it was. He rapidly deleted the post upon request of Hamid Alshareef. The following morning, Mr Shuaib drove Dr Hamid to the discovery spot located near a very difficult road. The inscription was cleaned on site, deciphered and photographed. The following day, Alshareef went again to the site with cleaning tools and a GPS in order to carry out a more accurate documentation of the inscription. The stone was then turned over, with the engraved face on the soil, in order to protect it. The inscription was later moved to the Agabis Museum, at el-Gaygab, seat of the municipality.

The stone was discovered on the northern bank of the wadi al Mahajjah (coordinates 32°34′59″ N 22°00′54″ E), ten kilometres west of the village of Qasr Khawlan, about 10 km from the fortress of Bellqes south-eastwards and approximately 40 km south of Cyrene (see Fig. 2). This must have been a chance discovery, as the area is frequented by loggers; one of them may have found the stone buried in the earth and believed that it was part of a grave. He thus dug it, causing some damage, and when it became clear to him that it was not a gravestone, he left it in this position and condition.

The monument is broken into two pieces (Fig. 7). The upper part is an originally rectangular limestone stele about 145 cm high, 86 cm wide and 30 cm deep. The upper and lower right corners are missing. The inscription is on the main face, whereas the back is uninscribed. The separated lower part must have been its base (height: 60 cm; depth: 45 cm) since a frame is designed to fit the two parts together. The stone is badly worn with multiple cracks and chips, so that some letters have been completely erased. The Latin inscription reads (Fig. 8):

-

TI CLAVDIVS CAES[..]

-

AVG GERMAN PV[.]

-

MAX TRIB POT XIII I[..]

-

XXVII P P CENS COS V

-

PER L ACILIVM STABONEM LEGA

-

TVM SVVM FINES INTER AIGVPVM

-

ET PROVICIAM CVREMSEM

-

[…….]IT

-

XXX

-

VIII

It can be restored as follows:

1 Ti(berius) Claudius Caes[ar]

Aug(ustus), German(icus), pu[n(tifex)]

max(imus), trib(unicia) pot(estate) XIII,i[mp(erator)]

4 XXVII, p(ater) p(atriae), co(n)s(ul) V,

per L(ucium) Acilium St<r>abonem lega-

-tum suum, fines inter Aigupum

et proui<n>ciam C{y}re{nen}sem

8 [ 5-6 ]it

XXX

VIII

Figure 7. Inscription no. 4 (photo H. Alshareef).

Figure 8. Detail of inscription no. 4 (photo H. Alshareef).

Translation: Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, high priest, holding the tribunician power for the 13th time, acclaimed imperator for the 27th time, father of the fatherland, consul for the 5th time, by the action of Lucius Acilius Strabo, his personal envoy, (…)ed the boundaries between Aigupus and the province of Cyrene. 38th <mile ?>.

This inscription at first sight recalls the well-known group of restitutio steles. Contrary to the others known from Cyrenaica, this one does not seem to be bilingual; at least, the Greek part did not survive. If it ever existed, it was perhaps cut on another stele, as the back of the stone bears no inscription. The Latin text has several mistakes, such as an omitted R in the legate's cognomen Strabo, an omitted N in prouinciam and the spelling of CVREMSEM, which is a haplology and a phonetic deformation to be corrected to Cyrenensem, as the official name of the province is Prouincia Cyrenensis. It should be noted here that the mention of Crete is lacking, although Crete and Cyrenaica were united in the same province at that time. However, the mention of Cyrene only is attested in other official inscriptions (for instance IRCyr2020 C.609) as long as the island was not otherwise relevant. Puntifex instead of pontifex is also quite regular in the Latin inscriptions from Cyrenaica.Footnote 21 Such errors may be explained by a poor knowledge of Latin and by the absence of a Greek model on the other side of the stone. The text must have been written by a person whose Latin level was weak or who had read the official record badly before engraving the text.

The emperor mentioned at lines 1–4 is Claudius. According to the imperial titulature, the date of the inscription is AD 53 (Claudius held his 27th tribunician power from January 53 to January 54). The titulature is exactly the same as the one on two other boundary stones respectively found in Beit Tamer (IRCyr2020 M.275) and in el-Khweimat (IRCyr2020 M.141). The new stele is therefore the third one from that year and belongs to the earliest phase of Strabo's mission.

We know of the restitutio operations led by Claudius’ and Nero's legate Lucius Acilius Strabo thanks to a series of inscriptions whose dates range from AD 53 to 55 and which come from the whole of Cyrenaica, from Ptolemais to Derna. Almost 20 boundary stones are now known.Footnote 22 Tacitus (Annals, 14, 18) states that Strabo had been sent by Claudius in order to restore the estates given by Ptolemy Apion to the Roman people in 96 BC and which had been illegally occupied by private owners. Strabo's tasks were mainly focused on the re-establishment of the boundaries between public and private lands. His mission was extended by Nero, but L. Acilius Strabo was brought to trial by the Cyreneans in AD 59 because the local aristocrats were losing lands due to the restitutio operations. The Senate declared itself as not having jurisdiction to pass such a judgment in this matter and Nero finally decided the case himself. He stated that Strabo's decisions were correct but paradoxically he left the lands to be occupied by their illegal squatters. Years later, Vespasian sent Q. Paconius Agrippinus to complete the restoration of the public estates and 14 other boundary stones referring to this stage have been found.

L. Acilius Strabo, probably originating from Neapolis (Naples) in southern Italy, was praetor c. AD 50 and then legatus Augusti in Cyrenaica between AD 53 and 55. A homonym was consul of Rome in AD 80 but it is not certain whether he is the same man or his son.Footnote 23 Thirty years between praetorship and consulship seem quite long, but the AD 59 trial should have slowed down his career. As a consequence, the identification between the legate and the consul is not totally impossible.

The majority of the boundary stones bearing the name of Lucius Acilius Strabo relate to the restoration to the Roman people of public lands illegally occupied by private citizens, with the formula ‘praedia/agros a priuatis occupatos Populo Romano restituit’ uel sim. When the word fines (or ὅροι in Greek) is used, it means that the legate had restored the boundaries to their previous condition by putting back the boundary stones (termini) in their legal position (Dobias-Lalou Reference Dobias-Lalou and Brunet2008). The new inscription seems to belong to this category. It is, however, quite unique in the corpus since it refers to an operation performed on the border between the Roman province and a place hitherto unknown called Aigupos/Aigupus. This is the first time in the epigraphy of the region that the name of an ancient place beyond the border has come to light. As a result, the text gives invaluable information on the outline of the Roman limes of Cyrenaica.

The problem lies with the identification of Aigupos. It is unlikely that this is another mistake and that the toponym would be rather read Aigup{t}us = Aegyptus. If so, the stele would be a marker of the border between Cyrenaica and Egypt but it makes no sense in this area. Aigupos is more probably the name of a small village (kome) outside the province, or rather one of those pyrgoi Diodorus Siculus speaks about when he describes the nomadic way of life of the southern Libyan tribes.Footnote 24 As a diphthong AI does not exist in the Latin language the name seems to be Greek or alternatively a Greek derivation from a Libyan name. If Greek, this name might refer to a vulture (αἰγυπιός). Checking the local toponyms available in ancient sources did not produce results.Footnote 25 The localization of Aigupus consequently remains unknown but should be looked for south of the wadi al Mahajjah where the stele has been discovered.

The new inscription should be compared to the one discovered in el-Khweimat (Elmayer and Maehler Reference Elmayer and Maehler2008; IRCyr2020 M.141), which also refers to the demarcation of the provincial border. Like the one from Khawlan, it has only one face inscribed, and it is in Greek. As read by the first editors the text is the following: Τι(βέριος) Κλαύδιος Καῖσαρ Σɛϐαστὸς Γɛρμανικὸς ἀρχιɛρɛὺς μέγι̣σ̣[τ]ο̣ς, δημαρχικῆς [ἐξου]σ̣ίας τὸ ιγ΄, αὐτοκ[ρά]τωρ τὸ κζ΄, πατὴ̣[ρ] πατρίδος, τιμητὴς, ὕπατος [τὸ] ɛ΄, διὰ Λ(ɛυκίου) Ἀκ̣[ιλί]ου Στράβωνος, ἰδίου π[ρ]ɛσβɛυτοῦ, μɛταξ[υ]μ̣ɛ̣σίτου καὶ τῆς Κυρ[ηναικῆς ἐ]παρχίας ὅρους [διακατɛχομένους ὑπὸ ἰδιωτῶν δ(ήμῳ) Ῥ(ωμαίω) ἀποκατέστησɛν]. The inscription begins as usual with the titulature of the emperor and the name of the legate as responsible for the operation, up to the word π[ρ]ɛσβɛυτοῦ. At the end of the preserved part, we find again a mention of the boundary stones (ὅρους), leading at first sight to the formulation predictable from other restitutio steles such as IRCyr2020 M.143. What was inscribed in the middle escapes the ordinary formulation; the editors admitted the plausible mention of the province of Cyrenaica (the reference without Crete is now corroborated by the new stele) and identified before it the very rare word μɛταξυμɛσίτης. The latter, meaning literally ‘intermediary’, would be the Greek translation of Latin disceptator, ‘arbitrator’, the very word used by Tacitus when he explains why Acilius Strabo was sent to Cyrenaica.Footnote 26 This restoration seemed at first sight plausible.Footnote 27 However, the Greek word is known only from an Egyptian papyrus of AD 330 in the context of a private dispute and it is not proven either that disceptator belonged to the official vocabulary or that it would be translated with μɛταξυμɛσίτης by the Roman chancellery. Anyway, if it was Acilius Strabo's title, its absence from the numerous documents of the series is very surprising. Furthermore, in the restored text καί seems quite out of place. The parallel with the Khawlan stele suggests that μɛταξύ corresponds to inter of the stele in Latin and that a toponym in the genitive would be hidden behind Μ̣Ε̣ΣΙΤΟΥ in the el-Khweimat text. This Mesites or Mesitos would appear in a position similar to Aigupos in the new stele; unfortunately, we cannot identify either of those place names. As a consequence, the restoration [διακατɛχομένους ὑπὸ ἰδιωτῶν δ(ήμῳ) Ῥ(ωμαίω) ἀποκατέστησɛν] at the end of the el-Khweimat stele now appears debatable, as it seems unlikely that a border could be ‘occupied by private persons’ and ‘returned to the Roman people’. Even the verb [ἀποκατέστησɛν] becomes now less plausible; the traces of letters on the Khawlan stele, although belonging to a form of the perfect tense, do not seem fitting with restituit. After that, a number of miles would have been mentioned, as we can see on the Khawlan stele.

These two inscriptions on boundary steles are the southernmost we know of in the region and they are markers of the limes in the central part of the provincial territory (Fig. 9). As the el-Khweimat stone has lost its lower part, the number of miles between Cyrene and the spot of discovery remains unknown. This difficulty had been strengthened by a confusion on the localization of el-Khweimat. In a 1996 paper, Mohamed and Reynolds alluded to an inscription bearing the name of the same legate which allegedly comes from Kwemet (el-Khweimat), 150 km south of Cyrene.Footnote 28 There is indeed a village called el-Khweimat 60 km south of Marawa, but this area is well beyond the Roman provincial border. In April 2020, Hamid Alshareef was able to ascertain the findspot of the stone: it actually comes from the cemetery of el-Khweimat, south-east of Gerdes el-Gerrari and about 3 km south of the village of el-Bouerat.Footnote 29 The fact that Mohamed (Reference Mohamed1992) wrongly mentioned el-Bouerat as being 150 km distant from Cyrene and that another village called el-Khweimat precisely existed further south generated the misunderstanding about the localization of the discovery spot, which has now been clarified.Footnote 30

Figure 9. Detailed map of the wadi al Mahajjah area (outlined in blue) with the location of the al Khawlan and the al Khweimat steles (background image: Google Earth).

In the Khawlan inscription, 38 miles are equivalent to approximately 55–56 km. The Khawlan area seems less distant from Cyrene (35–40 km as the crow flies), but the measurement may have been done following the ancient roads and the distance was therefore longer, since there was no direct route between Cyrene and Khawlan.Footnote 31 There is also a possibility that the stone has not been discovered at its original location. If so, it may not have been moved very far from it, and we can therefore be quite sure that the provincial border was located in this area.

As shown on the map, El-Khweimat and Khawlan are on the same line and direction and the inscriptions allow us to fix the Cyrenaican southern limes on the map, at least in this area: it passed around Qasr Khawlan, ran to the west along the wadi al Mahajjah, which served as a natural border for the province, and ended south of Suluntah in the area of el-Khweimat before probably turning south towards Marawa (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Map of the central part of the Cyrenaican chora with the localization of the steles and the approximate outline of the limes in this area (background image: Google Earth).

Be it as it may, both the findspots of both inscriptions and our interpretation of the outline of the limes confirm what Laronde (Reference Laronde1987, 308–13) had shown in his study of the chora of Cyrene: that the maximal extension of the city-state's territory (and later of the Roman province) was delimited by a line linking Kelida-al-Qubbah to Khawlan, to an area south of Lasamices-Suluntah (now located around el-Khweimat) and then southwards to Marawa. Between Suluntah and Marawa, it partly follows the inland road between Cyrene and Ptolemais. The limes outline should also be seen from an agricultural and economic perspective since it perfectly matches the climatic division between the garigue lands and the pre-desertic steppe.Footnote 32 The border was indeed following the 300 mm isohyet beyond which the rainfall lowers under 250 mm per year. North of that line, starting south of al-Faidiah and el-Gaygab, the quantity of Graeco-Roman remains had already started to decrease sharply and were replaced by troglodytic settlements (Marini Reference Marini2018, 49–58). Thus, epigraphy clearly corroborates what Laronde demonstrated based on geographical studies and surveys of archaeological sites.

South of the limes is the beginning of a pre-desertic area where agriculture is no longer possible and where several Libyan tribes were living. The latter were feared both by the Greek cities, as testified by Synesios of Cyrene, possessor of landed estates around Lasamices-Suluntah (Chevrollier Reference Chevrollier2014, 301), and by the semi-nomadic Libyan groups living inside the territory of the province. Those tribes outside of the province sometimes crossed the border to pillage the richer lands further north (Marini Reference Marini2018, 103–106). They are the ones the historian Strabo calls the ‘barbarians of the interior’ (Geography, 17, 3, 21). We can suppose that L. Acilius Strabo made it his first priority to secure the southernmost area of the Roman presence as soon as he came to Cyrenaica: in this view, the new inscription may be related to security more than agriculture.

The boundary stone is connected with a line of small stones which extends for a long distance to the east, and then changes its direction and continues north-east, passing north of Khawlan (Figure 11). It is conceivable that this line goes on to Beit Tamer where another boundary inscription was discovered, even if this one does not mention the provincial border (IRCyr2020 M.275; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1971).Footnote 33 An archaeological exploration of this line of stones should provide valuable information on its meaning and reveal its connection with the political border of the Roman province, as it might actually mark out the limes itself. It may also be compared to the clausurae known in the province of Tripolitania. The clausurae are linear barriers that may have served for customs regulations and the supervision of transhumance movements in the frontier area, as was suggested by archaeologists who surveyed them in the desert of Tunisia and western Libya.Footnote 34 We may have here the first clausura attested in Cyrenaica. Aerial photographs also show a circular feature about 1 km north of the findspot of the Khawlan boundary marker, but its identification remains so far unknown. If we really deal with a clausura, this feature may very well be a cistern or a watchtower, but, here again, the whole complex has to be investigated further to clarify its function, as much as we cannot exclude that we are dealing here with agricultural features and harvesting water systems such as the ones discovered in several wadis of Marmarica (Vetter et al. Reference Vetter, Rieger and Nicolay2009; Rieger Reference Rieger2017). The inscription should also be replaced into the archaeological context of the Roman forts and fortified farms marking out the limes. Several forts and farms are precisely located in this area, such as Qasr Wurtij near Khawlan or Qasr al-Maraghah and Qasr ar-Rimthayat further west.Footnote 35 The 10 km-long line of stones near which the inscription has been discovered may therefore also be connected to the defensive system of Roman Cyrenaica partially studied by R. G. Goodchild (Goodchild Reference Goodchild and Reynolds1976).

Figure 11. The long line of stones possibly outlining the limes or a clausura (photo H. Alshareef).

In conclusion, the inscription gives invaluable information on the southern political boundary between the Roman province and the Libyan tribes, and therefore on the outline of the Roman limes in the central part of the djebel al-Akhdar. It reveals a place so far unknown called Aigupos and demonstrates the continuing interest of the Roman provincial authorities in securing the border in this remote area. Finally, the stone adds another piece to the dossier of the restitutio operations that took place under Claudius and Nero. Further studies may enlighten the outline of the provincial border in other parts of Cyrenaica as other boundary inscriptions may very well be discovered along the limes.

However, the primary requirement is to conduct a full and extensive survey of the wadi al Mahajjah and of the whole area between Khawlan and Marawa. Such an exploration would be an important step in order to clarify the archaeological context of the long row of stones and to understand better how the Roman forts and the boundary stones fit with the defensive system of Cyrenaica during the first century AD.