1. Introduction

As states actively attempt to reform the system of investor-state dispute settlement,Footnote 1 this article provides a theoretical foundation for distinguishing between three ideal models of adjudication: private, public, and hybrid. It examines the implications of each model for the efficiency and legitimacy of dispute resolution institutions. The article demonstrates how inherent differences between models of adjudication affect the legitimacy of such institutions, the rule of law, and the facilitation of legal certainty. Regardless of whether the adjudication model is called adjudication or arbitrationFootnote 2 private, public, and hybrid models differ when it comes to the appointment of adjudicators, their professional background, and how long they serve.

While the distinction between substantive public and private law is widely recognized,Footnote 3 the distinction between private and public adjudication is less familiar. Scholars agree that states cannot be subject to the same legal procedures and moral approaches as private individuals,Footnote 4 but the features distinguishing private and public adjudication remain largely unexplored.

Private adjudication existed long before the emergence of states and subsequently flourished in various forms, including as lex mercatoria (the law of merchants) in the Middle Ages.Footnote 5 It still remains the only method of dispute settlement in some tribal societies.Footnote 6 Public courts in many countries for a long time had characteristics of private institutions funded by court fees, with each court trying to secure as much business as possible, including attracting claims not originally intended to fall under its jurisdiction.Footnote 7

At the end of the twentieth century, in the context of post-Cold War globalization, powerful private actors began to play a more important role in the world economy, controlling greater financial and political resources than many states and shaping dispute resolution methods.Footnote 8 Today multinational enterprises often avoid what they perceive as inefficient and oft-biased domestic courtsFootnote 9 and prefer to rely on international dispute resolution institutions.Footnote 10

The emergence of new fields, such as international human rights law and international investment law enables private claims against states and led to the emergence of new dispute resolution institutions. These institutions try to strike proper balancing of the protection of private interests (including property rights) against the public interest.Footnote 11 In this context, states are increasingly worried about powerful private actors, which limit what they consider as their sovereign powersFootnote 12 and undermine the legitimacy of dispute settlement mechanisms.Footnote 13

To protect their property, private parties may resort to various institutions, on some occasions even simultaneouslyFootnote 14 and may rely upon sophisticated corporate structures to access more favourable dispute resolution mechanisms.Footnote 15 Public adjudication institutions such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) coexist alongside private institutions such as the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC)Footnote 16 and the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC).Footnote 17 The dramatic rise of foreign direct investments created a new economic and political context and a demand for hybrid institutions tasked with the protection of foreign investments such as the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).Footnote 18

This article demonstrates that although private adjudication is usually quicker and may work well to resolve a specific dispute, it fails to facilitate legal certainty by setting precedents or clarifying the rules of conduct for future disputes. On the other hand, public adjudication institutions normally have the power to shape the interpretation of law for other parties in the future, not involved in the current dispute. They typically rely on earlier decisions to substantiate their rulings and generally aim at protecting the public interest and preventing the undesirable conduct in the future. Private adjudication always remains constrained by higher legal orders (through domestic courts) and does not have a pronounced ‘law-making’ function.

By examining the procedural rules and practices of selected institutions, the article asserts three main claims. First, the choice of public or private adjudication is likely to lead to different procedural outcomes, including the cost of the process and the duration. Avoiding the uncritical use of private dispute resolution mechanisms for essentially public disputes, and conversely, of public adjudication for private disputes will help improve the legitimacy of these institutions and better manage expectations of their users. Second, the legitimacy of any dispute resolution system must rest on both procedural and substantive aspects, but in reality, these two are often viewed in isolation. Finally, the article argues that private and public adjudication institutions have much to learn from each other and proposes how they could learn from each other to become more efficient and strengthen their legitimacy.

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 illustrates how different institutions serve to secure property rights. Section 3 focuses on procedural aspects of dispute resolution across different institutions: appointment and tenure of adjudicators, transparency and confidentiality, the length and the cost of adjudication. Section 4 discusses the substantive aspects of adjudication including applicable law and review mechanisms. Section 5 takes a normative approach and considers procedural and substantive legitimacy of dispute resolution. In particular, it demonstrates how public, hybrid and private adjudication can learn from each other. Section 6 concludes.

2. Conceptual framework

Since the emergence of states, property rights have come under threat, primarily from other private actors and from the state. The risks from the private direction include monopolizing the markets, dumping practices, criminal conduct or even outright violence (‘the risk of disorder’).Footnote 19 States can infringe property rights by expropriation without appropriate compensation, denial of justice and other infringements (‘the risk of dictatorship’).Footnote 20

The traditional response to securing property rights is to assert claims through neutral adjudication. In theory, independent domestic courts should resolve disputes involving non-public and public infringement of rights. In practice, the lack of institutional capacity to efficiently resolve such disputes on a domestic level (e.g., insufficient expertise, lack of resources or corruption) means that international courts and tribunals often fill the gap.Footnote 21 The idea of international adjudication is that highly qualified independent adjudicators with experience in handling similar disputes should resolve disputes related to property rights efficiently, thus restoring market discipline.Footnote 22

This article analyses five dispute resolution mechanisms relevant to securing property rights to explore differences between procedural rules, practices and institutional capacity of these institutions: ICJ, ECtHR, ICSID, ICSID, and SIAC. All these institutions serve the goal of securing property rights, among other goals. However, they differ significantly when it comes to their institutional design and procedures, which affects their efficiency and legitimacy. The selection of these five institutions allows us to draw a manageable illustration of the public–private spectrum: two public, one hybrid, and two private adjudication institutions. The aim is not to express a view as to their quality and efficiency but to facilitate presentation of the key ideas. Before discussing the differences between public, hybrid and private adjudication models and their implications, it will be useful to illustrate the conceptual differences with a few examples related to securing property rights.

A dispute between the United States and Italy decided by the ICJ illustrates purely public adjudication.Footnote 23 In that case, the court considered alleged interference with the shareholders’ right to ‘control and manage’ a US company, by Italy’s requisition of the company’s plant and equipment. The US brought a claim to protect the private investor’s property rightsFootnote 24 on the basis of an international treaty.Footnote 25 The judges, all experts in public international law with fixed-term appointments,Footnote 26 decided the case in accordance with the applicable municipal and international law and rendered a publicly available judgment, Footnote 27 which could not be challenged in domestic courts.Footnote 28

Another example of a property dispute resolved by a public institution comes from the ECtHR. Yukos, once the largest Russian oil company, asserted a claim based on breaches of the right to property under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).Footnote 29 The dispute arose out of tax assessments and enforcement of the debt resulting from these assessments. The panel of judges, consisting of experts on international human rights lawFootnote 30 appointed for fixed periods of time,Footnote 31 delivered a judgment Footnote 32 which, similar to ICJ judgments, domestic courts cannot revisit.Footnote 33

The Exxon Mobil v. Venezuela case serves as an illustration of how ICSID, a hybrid public-private adjudication mechanism, functions.Footnote 34 In that case, a foreign investor alleged that the host state breached a treaty by adopting regulatory measures resulting in the expropriation of its property.Footnote 35 The parties decided to conduct their proceedings in Paris and appointed their arbitrators for this particular case, who rendered a publicly available award. Footnote 36 This award can be revised and annulled by a special committee appointed by the ICSID Secretariat, but not by domestic courts.Footnote 37

Finally, private commercial arbitration institutions such as ICC and SIAC decide a significant number of international disputes related to the protection of private property. The vast majority of awards remains confidential,Footnote 38 which makes it difficult to give an example of a typical case. Both institutions allow the parties to agree on the law applicable to the merits of the dispute,Footnote 39 the seat of arbitration,Footnote 40 and the identity of arbitrators – most of whom tend to have backgrounds in private legal practice.Footnote 41 The awards are not subject to appealFootnote 42 but domestic courts can set them aside or refuse their enforcement in case of certain procedural irregularities.Footnote 43

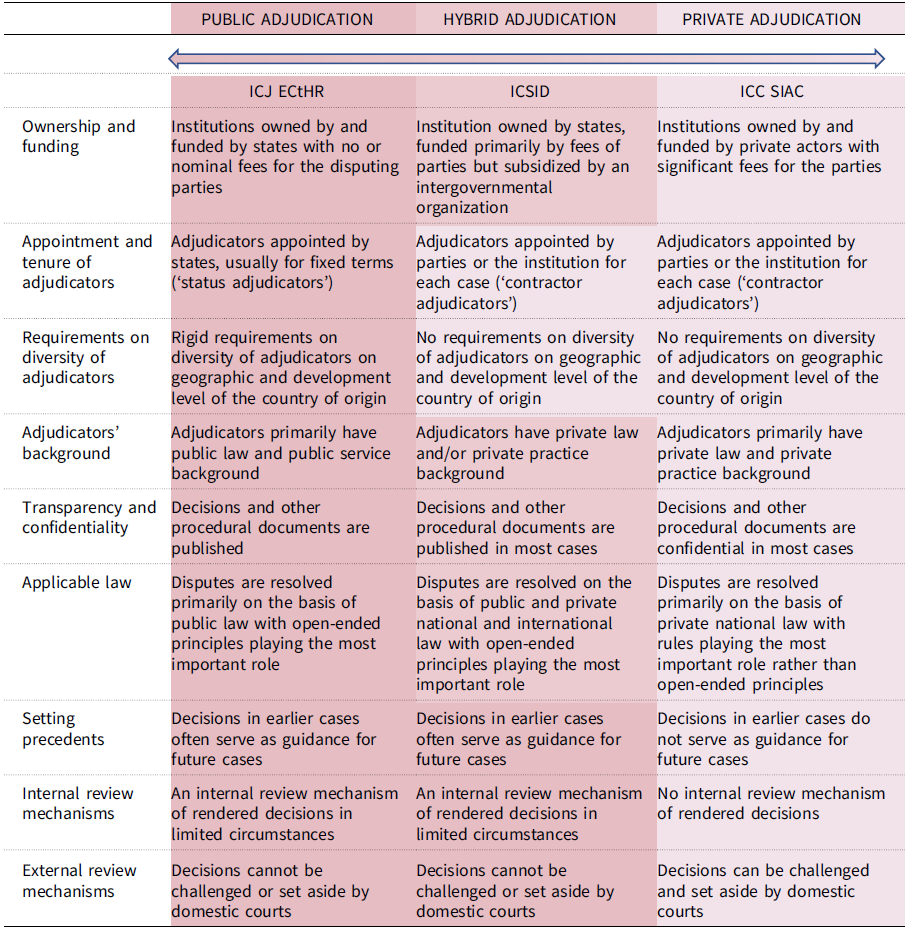

Table 1 demonstrates the essential differences between public, hybrid and private dispute resolution institutions explained in more detail in subsequent sections of this article.

Table 1. Public and private adjudication continuum

3. Procedural aspects of adjudication

3.1. Appointment of adjudicators

Empirical studies demonstrate that in the domestic context, the identity of adjudicators may correlate with decision-making patterns. For example, the race,Footnote 44 gender,Footnote 45 and even whether adjudicators have daughtersFootnote 46 have a proven effect on decision-making. Not surprisingly, determining the procedure for adjudicators’ appointments often lead to political battles at nationalFootnote 47 and international levels.Footnote 48

Procedural rules of the vast majority of dispute resolution institutions, regardless of their public or private nature, explicitly require that adjudicators act impartially.Footnote 49 However, approaches on how to achieve this diverge. Dispute resolution systems on the public end of the spectrum, such as the ICJ and ECtHR, favour appointing judges for fixed periods of time. Although both the ICJ and ECtHR allow the appointment of ad hoc judges, the vast majority of judges are appointed according to the procedure explained below.Footnote 50

The United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Security Council elect the majority of ICJ judges Footnote 51 from candidates nominated by state parties to the ICJ Statute.Footnote 52 Each judge serves for a renewable fixed term.Footnote 53 ECtHR judges are also elected by states for fixed terms.Footnote 54 Public adjudication institutions have strict conflict of interest rules. In order to ensure the independence and impartiality of the judges, the ICJ Statute prohibits them from exercising any political or administrative function, engaging in any other occupation of a professional nature, or acting as agent, counsel, or advocate in any case.Footnote 55 Similar to the ICJ, ECtHR judges cannot engage in any political, administrative activity or professional activity incompatible with their independence or impartiality or with the demands of a full-time office.Footnote 56

Private dispute resolution offered by SIACFootnote 57 and ICCFootnote 58 allows parties significant freedom to appoint their own arbitrators. Usually, each party appoints its own arbitrator for a specific case and if there is a disagreement on who should be the third presiding arbitrator, the relevant institution appoints the presiding arbitrator. The parties may agree upon the method of appointment that they would like to apply to a certain dispute, and the institutional procedures only apply in the absence of an agreement between the parties. Private arbitration institutions normally impose no restrictions on engaging in political, administrative activity or other professional activities.

The hybrid ICSID adjudication largely follows the private adjudication model appointing adjudicators for each specific case.Footnote 59 However, the system also provides for annulment, where the members of annulment committees are appointed not by the parties but by the Chairman of the ISCID Administrative Council Secretariat in each case.Footnote 60

3.2. Public or private law background of adjudicators

The adjudicators at dispute resolution institutions on the public side of the spectrum such as the ICJ tend to have held senior administrative, judicial or legal academic positions in the past.Footnote 61 The vast majority of ECtHR judges have public sector or academic backgroundsFootnote 62 and similar patterns can be observed in other public dispute resolution institutions.Footnote 63 In private adjudication, private practitioners dominate comprising nearly 80 per cent of all ICC arbitrators.Footnote 64 The majority of arbitrators sitting in ICSID tribunals have backgrounds working in private law firms,Footnote 65 which arguably can make them less familiar with public law approaches to interpretation and less sensitive to the public interest.Footnote 66

Adjudicators in public adjudication are appointed for specific periods with fixed salaries as well as diplomatic immunity (‘status adjudicators’)Footnote 67 whereas arbitrators in private and hybrid adjudication are normally paid on an hourly basis and their income depends on the number of appointments they secure (‘contractor adjudicators’). Arguably fixed-term appointments make adjudicators less sensitive about the needs of the parties. However, they may pay more attention to the public interests of the governments, which elect them, and their decisions are likely to affect their re-election prospects.Footnote 68 On the other hand, party-appointed adjudicators may have more ‘feel of the issues’ because of their expertise and them being under more pressure to satisfy the parties to secure future appointments.

Empirical studies show that the professional background of adjudicators influences their approaches to questions of law.Footnote 69 For example, a study of ECtHR practice demonstrated that adjudicators with a career in the public sector (either as diplomats, state officials, or at other government offices) are more likely to defer to the national interests of the states.Footnote 70 Another empirical study shows that in ICSID cases where the presiding arbitrator is a national of an advanced economy with a private practice background rather than a governmental background, investors have a 25 per cent greater chance of receiving an award of damages.Footnote 71 Presiding arbitrators with a background in private practice are more likely to assert jurisdiction and in a three-member tribunal; the policy preferences and incentives of party-appointed arbitrators are likely to offset each other, leaving the ultimate decision to presiding arbitrators,Footnote 72 normally appointed by ICSID in the absence of agreement between the parties.

3.3. Geographic diversity of adjudicators

In international adjudication, the country of nationality of adjudicators has a proven effect on the substance of decisions. One study found evidence that arbitrators originating from developing countries are more likely to render smaller awards against developing countries.Footnote 73 Public and private adjudication differ significantly when it comes to principles related to the nationality of arbitrators. Some argue that a small number of powerful states tend to dominate the institutional design of international dispute resolution institutions, which led to decisions of questionable legitimacy in themes of developing states, which did not have much say in the design of those institutions and were ultimately left powerless.Footnote 74

In public adjudication, such as ICJ and ECtHR the rules mandate equitable geographical distribution of adjudicators.Footnote 75 ICJ judges are supposed to represent ‘the main forms of civilization and of the principal legal systems of the world’.Footnote 76 Indeed, current members of the ICJ have different nationalities, come from almost all continents of the world, and represent both civil and common law legal systems.Footnote 77 Similarly, each Council of Europe member state can appoint a judge of its choosing to the ECtHR.Footnote 78 Although states are not bound by the nationality criterion, most judges tend to be nationals of the appointing state.Footnote 79 In other words, public adjudication institutions aim at an equitable representation of all states involved in the work of these institutions and as a result, adjudicators reflect the diversity of the disputing parties.Footnote 80

In contrast, private adjudication institutions have very few restrictions on where the arbitrators should come from. For example, the ICC merely requires that the sole arbitrator or the president of the arbitral tribunal is of a different nationality than those of the parties (unless they agree otherwise)Footnote 81 while the SIAC imposes no restrictions on the parties with respect to nationality.Footnote 82 A review of the caseload of private institutions such as the ICCFootnote 83 and SIACFootnote 84 suggests that most arbitrators originate from regions from where the biggest share of their users come.Footnote 85

Private disputes are resolved primarily on the basis of domestic law, which leads to appointments from relevant jurisdictions making it nearly as diverse as the number of legal systems involved.Footnote 86 As market-driven institutions, they aspire to facilitate the needs of their users. Private institutions are not under pressure to secure a certain geographic distribution of adjudicators, but the body of arbitrators is rather diverse because of the need to engage domestic law experts.Footnote 87

Hybrid adjudication institutions, such as ICSID, do not show the same degree of representation of the disputing parties as private and public institutions. ICSID has no formal rules aimed at ensuring equitable representation of states among adjudicators similar to those found at the ICJ or ECtHR.Footnote 88 In practice, this results in a mismatch between the regions where the parties come from and the appointed adjudicators. The largest share of respondents in ICSID disputes comprises states from Eastern Europe and Central Asia (26%) and South America (23%), but the majority of adjudicators come from Western Europe (47%) and North America (20%).Footnote 89

What explains this mismatch between the respondent states and adjudicators in the hybrid model? In the absence of mandatory rules, developing countries tend to appoint well-known arbitrators from the Global North to maximize their chances of winning, even if their appointees know very little about the laws, the culture of doing business, or the languages of the region. This has become a major concern for a number of states, which point out that the pool of arbitrators is homogenous in terms of its origin,Footnote 90 and for some scholars, who view the ICSID system as a way to undermine developing countries or as a form of colonialism.Footnote 91 Many developing states consider that this weakens the legitimacy of the system of investor-state disputes.Footnote 92

Although individuals from developing countries comprise half of the recent designations by the Chairman of the ICSID Administrative Council to the ICSID Panel of Arbitrators and Conciliators,Footnote 93 in practice their appointments remain rare. The ICSID Secretariat also favours Western European adjudicators who recently comprised 44 per cent of all appointments made by it, while representatives of the largest group of respondent states (Eastern Europe and Central Asia) accounted for only around 2 per cent.Footnote 94

To sum up, the identity and the method of appointment of adjudicators differ in public, private dispute and hybrid dispute resolution. Judges in public adjudication systems better reflect various regions where various parties come from compared to hybrid adjudication because of rules on fixed-term appointments. Somewhat unexpectedly, the diversity of arbitrators in private, market-driven adjudication is greater compared to hybrid adjudication. The main reason is that most disputes are decided under domestic law rather than on the basis of open-ended and often ambiguous international law principles or standards.

3.4. Transparency and confidentiality

Approaches to transparency significantly differ in private and public adjudication. In private adjudication, the normal approach is confidentiality; in public adjudication, the norm is maximum transparency.

A typical example of transparency under a public adjudication procedure is the ICJ, which publishes judgments, orders, advisory opinions, and any other document that the court may direct to be published.Footnote 95 The ICJ can decide to make copies of the pleadings and annexed documents accessible to the public. Footnote 96 Likewise, the ECtHR rules provide that final judgments and nearly all procedural documents are published in a free public database.Footnote 97 Private adjudication institutions such as the ICC and SIAC normally do not provide such information: to avoid disclosure of sensitive information, confidentiality remains the norm.Footnote 98

In hybrid adjudication such as ICSID, the situation is different. If both parties consent, the institution can publish arbitral awards, minutes and other records of proceedings.Footnote 99 In the absence of consent, the institution is under an obligation to promptly include excerpts of the legal reasoning of the tribunal in its publications.Footnote 101 Once a case is registered to ICSID, the relevant information on particular aspects of the dispute (including the parties, subject of dispute, economic sector, instrument invoked, and applicable rules) becomes available online for public access.Footnote 102

The summary of procedural rules in Table 2 shows that transparency standards in public adjudication institutions are relatively high, since almost all the documents and the hearings are public. At the other end of the spectrum are hybrid and private adjudication models. ICSID, SIAC and ICC rules do not provide for greater transparency unless the parties decide to apply the UNCITRAL Rules of Transparency.Footnote 103 At ICSID, public access to documents and hearings depends entirely on the parties or the applicable law (e.g., a relevant treaty may provide for transparency rules). Private adjudication institutions have more restrictive rules on public access, reflecting the needs of private users for confidentiality.

Table 2. Publication of dispute-related materials (as a general rule)Footnote 100

It appears that without the legitimacy of being selected by the parties, the least public adjudicators can do is to publicly explain the logic of their decisions, including by means of dissenting or concurring opinions. As Table 2 demonstrates, the public and private adjudication approaches to confidentiality clash in hybrid regimes, as tribunals have to engage in balancing private parties’ entitlement to commercial confidentiality and the public’s right to information about issues that affect the public at large.Footnote 104 The ongoing reforms have resulted in efforts to introduce greater transparency in hybrid investor-state dispute settlement.Footnote 105

Arguably, in public adjudication, adjudicators have a greater motivation to explain their reasoning for future disputes because their decisions are public. Private adjudicators who derive their appointments and legitimacy from private parties, the need to inform the public at large is less pressing. As the next subsection will show, this also has a knock-on effect on the cost and duration of proceedings.

3.5. Duration of proceedings

Resolving disputes in a time-efficient and cost-efficient manner is an important component of the rule of law and expectations of the parties.Footnote 106 Comparing the selected five institutions suggests that public and hybrid adjudication cases on average last longer than private adjudication.

The median duration of ICJ cases is around four years and the median length is around 28,000 words.Footnote 107 The median duration of ICSID proceedings was also around four years, but the median length of decisions was much longer – around 50,000 words.Footnote 108 The median duration of 20 ECtHR proceedings related to the protection of property was nearly nine years but with comparatively short judgements – around 5,500 words.Footnote 109

As awards in private adjudications normally remain confidential, it is more difficult to access the duration of proceedings and length of decisions. However, arbitration institutions track the duration of their proceedings to retain their competitiveness. For example, according to one study by SIAC, the median duration of their proceedings in cases filed under SIAC Rules in 2013 was approximately one year.Footnote 110 Rules of arbitration institutions can also give a clue as to the ‘normal’ duration of the proceeding. For instance, under ICC rules the arbitral tribunal must render its final award within six months from the signing of the terms of reference.Footnote 111 That suggests that private adjudication proceedings are significantly shorter than public adjudication, where proceedings take years.

Surprisingly, ICSID decisions, being a hybrid of public and private procedures, turned out to be the second-longest after ECtHR. While the high volume of cases and a limited number of adjudicators explains the long duration of ECtHR proceedings,Footnote 112 the explanation for ICSID with access to an infinite number of adjudicators is different. Legal reasoning in ICSID awards often counts hundreds of pages resulting from the public international law character of investment disputesFootnote 113 as well as the reliance of tribunals on vague and ill-defined principles, as explained in subsection 4.1 below. Arguably, the involvement of states in investment disputes, the relevance of local industries, and implications of these disputes for economies result in more extensive reasoning in investment treaty arbitration than in international commercial arbitration.Footnote 114

As a prominent arbitrator explained, in private disputes, national laws are ‘sufficiently developed to be predictable, and the arbitrators’ role does not involve developing rules belonging to this national law’,Footnote 115 whereas in public disputes, international law is ‘less developed and is still in the process of being formed’ and therefore the arbitrators’ role in the establishment of predictable rules becomes much more important.Footnote 116 This is one of the reasons why proceedings end up being shorter in private adjudication.

The hybrid private-public ICSID proceedings appear to be an outlier in terms of length also because of the ease of challenging adjudicators which slows down the proceedings.Footnote 117 Some explain it by the reluctance of tribunals to act decisively in certain situations to avoid challenges, or setting aside or annulment of the award, which may also lead to multiple extensions of time or rescheduling of hearings.Footnote 118

3.6. Cost of proceedings

In public adjudication institutions, such as the ICJ and the ECtHR, disputing parties normally bear only the legal costs of their legal representation and experts.Footnote 119 Governments, which established such institutions, cover nearly all other costs, including the salaries of judges, which do not depend upon the number of cases.Footnote 120 Parties to ICJ and ECtHR disputes can also benefit from legal aid to access these dispute settlement mechanisms.Footnote 121 Such institutions serve to promote important public goals, such as protection of human rights or peaceful resolution of disputes between states,Footnote 122 which may explain the reason why they do not charge the disputing parties for their services and offer legal aid.

Private adjudication institutions focus on the resolution of specific disputes between partiesFootnote 123 rather than on achieving certain public policy objectives. In private dispute resolution institutions, such as the ICC and SCC, in addition to costs of representation (counsel, experts), the parties also pay the fees and expenses of arbitrators and tribunal secretaries, as well as administrative costs charged by arbitral institutions. Footnote 124 Moreover, in some situations the losing party also needs to contribute or entirely cover the costs of the winning party.Footnote 125

The ICSID model of funding and costs reflects its public-private hybrid nature: the institution itself is a creature of an international treaty and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development makes a significant in-kind contribution to the expenses of ICSID. Footnote 126 On the other hand, adjudicators get their appointments on a case-by-case basis and much of the institution’s funding comes from the income generated from its users.Footnote 127

Despite being an intergovernmental organization, ICSID is rather expensive to accessFootnote 128 and offers no legal aid for investors or states, which may struggle to afford the high costs of ICSID proceedings. Footnote 129 This is why the high cost of investor-state arbitration remains an important criticism of the ICSID system,Footnote 130 with developing states in particular feeling that the system imposes a disproportionately heavy burden on them. Footnote 131 The lack of precedent and reliance on vague standards also adds to the cost of proceedings as many issues dealing with jurisdiction and merits remain unsettled.

To sum up, the difference between public adjudication is evident when it comes to costs of proceedings. The system with salaried judges and no or nominal payments to access dispute resolution institutions and access to legal aid is expensive to maintain for states but cheap to access for the users. The private adjudication institutions are normally more expensive to access for the parties but require no funding from states. Although ICSID as a hybrid institution is established and partially funded by states, most of its income comes from the disputing parties, it is rather expensive to use and offers no access to legal aid.

4. Substantive aspects of adjudication

4.1. Applicable substantive law: principles and rules

Procedural aspects of adjudication institutions cannot be isolated from their substantive aspects. The distinction between public and private substantive law can be traced at least to Roman law, under which all disputes to which the state was a party belonged to jus publicum. In disputes related to jus publicum, the norms of jus privatum as enforced by courts between private parties did not apply. State officials observed the relevant legislation but were not subject to other principles except for a vague notion of promoting the public interest.Footnote 132 On the other hand, the state abstained from interference into jus privatum, leaving it to the private parties – something which Roman lawyers considered a significant achievement.Footnote 133

In other words, a more general principle of pursuing the public interest rather than formal rules primarily constrained public law. However, adjudicators often used precedent as a way to avoid blame, particularly where deliberations were made in public.Footnote 134 Judges could shelter themselves from blame by using examples of precedents of other judges, which also helped to form an orderly system. As this section will show, the same public-private distinction to a certain degree has survived in public adjudication, often guided by open-ended principles.

The ICJ Statute specifies that the function of the court is to decide the disputes in accordance with international law and lists the primary sources and subsidiary means for its determination. Footnote 135 The applicable law before the ECtHR is primarily the ECHR and its protocols, but in practice, the Court often makes reference to other human rights treaties, as well as other relevant rules and principles of international law, especially on treaty interpretation.Footnote 136 Both the ICJ and the ECtHR primarily rely on public international law, including decisions in previous cases.Footnote 137

The ICSID Convention does not provide a set of applicable substantive rules but states that, unless otherwise agreed by the parties, the law of the host state and international law apply.Footnote 138 The term ‘international law’ corresponds to Article 38(1) of the ICJ Statute, bearing in mind that this Article was designed for inter-state disputes.Footnote 139 In other words, in the ICSID system, both international public law and domestic law serve as the main sources of applicable law.

Under the ICC and SIAC arbitration regimes the parties agree on the applicable law, and if not, the tribunal will apply the rules of law that it considers appropriate.Footnote 140 The ICC Arbitration Rules also expressly set out that the tribunal shall take account of the contractual provisions agreed by the parties and any relevant trade usages.Footnote 141 In practice, choice-of-law clauses in ICC and SIAC disputes almost always provide for national laws of a particular jurisdiction.Footnote 142 Although national law includes private and public law, most disputes resolved in commercial arbitration relate to the interpretation of private law, particularly contract law.

Public law does not necessarily rely on principles more than on rules compared to private law.Footnote 143 However, the analysis of the selected five institutions suggests that public adjudication (ICJ, ECtHR) demonstrate a greater degree of reliance on open-ended principles compared to private adjudication (ICC, SCC) where domestic law applies and usually contains comprehensive rules on various issues.

Typically, rules offer more legal certainty than principles. When formulated as rules, the distinction between the impermissible and permissible conduct is more clear compared to principles, this clarity is crucial for the legitimacy of any adjudication procedure and the rule of law.Footnote 144 Formal rules as opposed to open-ended principles help to restrain official arbitrariness and to provide legal certainty.Footnote 145 Substantive rules drawn in advance also reduce the burden on the parties of having to research and argue the law, resulting in shorter duration and as a result lower costs of adjudication which also helps to address the problem of inequality of the parties.Footnote 146 However, the lack of detailed public international law rules often forces public adjudicators to resort to open-ended principles. The imprecise nature of principles gives tribunals extensive interpretative freedoms, and this can lead to lengthy and costly proceedings. It also gives more room for the adjudicators’ discretion, which may even result in politically motivated bias or corruption.Footnote 147

The reliance on broadly formulated principles becomes particularly problematic when it results in multiple conflicting interpretations of various standards, which is not helping future dispute resolution.Footnote 148 This supports the view that arbitration is normally suitable only for disputes where the rules are perfectly clear.Footnote 149 For example, in the ICSID system, although most decisions are public, they do not serve as precedents. In the absence of an appeal mechanism, there is no obvious way of harmonizing conflicting awards and adjudicators take a variety of different approaches to interpreting vague standards even in situations where the factual and legal issues are very similar. When private adjudicators have a nearly unrestricted freedom to interpret broad principles involving public policy concerns, that poses a significant problem for the legitimacy of the hybrid ICSID system and investor-state dispute settlement more generally.Footnote 150

Vague principles also lead to an increase in the number of disputes because the vagueness creates an impression that each party has a chance to win. Not surprisingly, states complain about long duration, unpredictability, and a lack of consistency in arbitral decisions resulting from the significant interpretative discretion of adjudicators.Footnote 151 Tribunals may interpret the same treaty standard or principle of international law differently without a justifiable ground for the distinction.Footnote 152 This has a direct relevance to the development of the applicable substantive law, as it fails to help the parties to understand their rights and obligations.

This analysis of five selected institutions suggests that in public adjudication, disputes are resolved primarily on the basis of public law with open-ended principles playing the most important role. In hybrid adjudication, disputes are resolved on the basis of public and private national and international law with a significant reliance on open-ended principles. In private adjudication, disputes are resolved primarily on the basis of private national law with rules playing the most important role. While public adjudication institutions aim at facilitating consistency and coherence, private and hybrid adjudication focuses primarily on the dispute at hand.

4.2. Review of decisions: Internal and external

Review mechanisms such as internal appeals or challenges in domestic courts serve the function of making substantive rules more coherent and predictable thus facilitating legal certainty. Virtually all domestic legal systems provide for the right to appeal judicial decisions to correct errors. Review mechanisms also serve a ‘law-making’ function to inform other stakeholders about erroneous decisions and reduce the number of future mistakes.Footnote 153 States see the absence of review mechanisms and the inconsistency of arbitration awards in the hybrid investor-state arbitration such as ICSID, as a major setback to their legitimacy.Footnote 154

Public adjudication systems tend to provide for limited internal review mechanisms but no right of appeal. For example, once rendered, ICJ judgments are final Footnote 155 and the parties may only resort to the revision of judgments of the court on limited grounds such as the discovery of a previously unknown potentially decisive fact. Footnote 156 Similarly, the rules of the ECtHR do not provide for appeal but for revision in case of discovery of a fact of a decisive influence.Footnote 157 Moreover, in exceptional circumstances, the ECtHR Grand Chamber can review decisions of the Chambers on the merits to deal with a serious issue of general importance that affects the interpretation or application of the ECHR and its protocols.Footnote 158 Essentially, the ECtHR reduces the cost of errors by selectively reviewing the cases where errors are most likely to occur rather than allowing a general right of appeal.

The ICSID model is similar to those adopted by other public dispute resolution institutions – it does not provide for an appeals procedure or an external review mechanism for awards,Footnote 159 enforceable as if they were a final judgment rendered by states’ domestic courts.Footnote 160 However, the ICSID Convention allows the parties to request revision in case of discovery of a potentially decisive factFootnote 161 or to request annulment of an award. A specially constituted ad hoc committee appointed by the ICSID Secretariat from a panel of arbitrators may annul the award if the tribunal was not properly constituted, has manifestly exceeded its powers, because of corruption on the part of an arbitrator, a serious departure from a fundamental rule of procedure, or for failure to state the reasons on which the award is based.Footnote 162 In other words, it provides for additional grounds to challenge decisions internally compared to ICJ and ECtHR.

Domestic courts cannot review decisions resulting from public adjudication, but they can review private arbitration awards. Each party may file an application to set aside an arbitral award in courts of the seat of arbitration.Footnote 163 The parties may also resist recognition and enforcement of an award in domestic courts on the grounds provided in the New York Convention.Footnote 164 In most jurisdictions, this review is confined to procedural issues, such as the validity of arbitration agreements, respect for due process, or constitution and competence of the tribunal.Footnote 165 However, state courts can also set aside or annul awards on public policy grounds.Footnote 166

The ICC Arbitration Rules provide for a peculiar internal review mechanism, which is not available in SIAC arbitration. According to this procedure, the International Court of Arbitration, acting as an independent body, may modify the form of the award or draw the arbitral tribunal’s attention to substantive issues before the signing of the award.Footnote 167 This, however, cannot be regarded as an award review mechanism because the court essentially reviews the draft award before it becomes final.

This section shows that public procedures such as those at the ICJ or the ECtHR leave no room for the review of final decisions by domestic courts but normally provide for a self-contained form of review within the institution itself. In public adjudication, national courts cannot review public international law judgments and awards because international law normally prevails over domestic law.Footnote 168 On the other hand, awards resulting from private adjudication are not subject to internal appeal but can be challenged in domestic courts according to national arbitration laws.

Not surprisingly, public adjudication institutions such as ICJ or ECtHR established by states do not allow review of their decisions by domestic courts. This is partly compensated by their internal review mechanisms. It also makes sense that decisions of private institutions can be reviewed by domestic courts, which helps states to protect certain public policy objectives.

5. Strengthening legitimacy and efficiency of dispute resolution

5.1. Procedural legitimacy

The legitimacy of a dispute resolution institution is understood here as acceptance of an institution as designed and operated in accordance with generally recognized principles of due process.Footnote 169 To a significant extent, legitimacy depends on who has established an institution – public or private actors. For example, hybrid adjudication is substantively public but procedurally private, which leads to legitimacy disconnect as some states are unwilling to accept private foreign arbitrators deciding on important public policy issues.Footnote 170 On the other hand, foreign investors may have good reasons to avoid domestic courts, as even in countries with a strong rule of law, courts are political institutions if the dispute concerns implementation of regulatory policy.Footnote 171 This may undermine the legitimacy of the procedure in the eyes of a foreign investor. In other words, legitimacy is not absolute but relative.

The legitimacy of any dispute resolution institution must rest on both procedural and substantive aspects, while in reality these two are often viewed in isolation. Even if one can imagine a fair and efficient procedure, it may not appear legitimate if it does not rest on a consistent and predictable body of substantive law but on principles. On the other hand, a body of substantive rules without a satisfactory procedure (e.g., excessively expensive) will not result in a system based on strong legitimacy.

This article demonstrates that it is not enough to distinguish between private and public adjudication only by looking at the nature of the parties (e.g., state or private), the subject matter of the dispute (e.g., a contractual dispute or a challenge to regulatory measures of states), the ownership of the institution (e.g., public or private), the name of the dispute resolution body (court or tribunal), or whether the procedure is described as arbitration, litigation, contentious proceedings or by another term. A range of procedural and substantive aspects of adjudication determine their public, private or hybrid nature and affect their legitimacy.

Appointment mechanisms constitute an important element of legitimacy and the rule of law. It is generally expected that disputes are resolved by those who reflect the makeup of the communities they serve.Footnote 172 In domestic legal systems, judicial function is traditionally regarded as resting on delegation from the people’s representatives.Footnote 173 In international adjudication, the chain of delegation is further removed: people elect politicians, who in turn delegate their judicial power to international or foreign institutions, which in many cases delegate it further to foreign arbitrators rather than domestic courts.

As discussed in Section 3.3, in public adjudication such as that of the ICJ and the ECtHR, states appoint judges who represent different developmental and geographic constituencies and in private adjudication institutions appointees generally reflect the countries involved in the disputes. However, appointed arbitrators in hybrid adjudication rarely reflect the regions of the disputing parties they serve as discussed in Section 3.1.

The background of arbitrators is particularly important when disputes are resolved on the basis of open-ended principles as opposed to detailed rules, as adjudicators have a significant discretion to interpret such laws and practices imposing their vision on sovereign states. This mismatch can be tackled either by establishing additional requirements to adjudicators (e.g., to ensure regional representation) or introducing fixed-term appointments.

Although parties make most of the ICSID appointments, appointments by arbitration institutions can potentially play a significant role in enhancing the diversity of arbitrators.Footnote 174 In this context, it could be useful to look at the efforts of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to balance the position of developing and developed states in the WTO dispute settlement procedure.Footnote 175 The WTO created an explicit expectation that special attention should be given to the particular problems and interests of developing country members.Footnote 176 In a dispute between a developing country member and a developed country member, upon the request of the developing country member, the panel shall include at least one panellist from a developing country.Footnote 177

Qualifications of adjudicators also matter. In ICSID adjudication, individuals with only commercial law experience without any meaningful exposure to public international law can get appointments to resolve public law disputes. That reduces the quality and consistency of awards. To illustrate this problem – in a commercial dispute governed by English law, it would be highly unusual to appoint as an adjudicator someone without any proven expertise in English law. However, this is not unusual to appoint in investor-state disputes individuals with no meaningful experience in the area of public international law. Although the parties decide whom to appoint as arbitrators in ICSID disputes, requirements for qualifications of arbitrators can be set out in the relevant arbitration rules.

Duration and costs of adjudication proceedings also affect their legitimacy. For example, as discussed in Section 3.6, the costs of resolving public disputes using private adjudication can be prohibitively expensive, particularly for smaller claimants, which results, among other things from the lack of a consistent body of laws. The pressure to justify publicly available decisions in the absence of clearly defined rules impacts the duration as well as the length of awards.

Funding of dispute resolution institutions and the availability of legal aid also shape their legitimacy. States financially support public adjudication institutions with most services provided for free or at a nominal charge. One reason why private adjudication institutions may survive and flourish is because they rely on the applicable law created by legislators and public adjudicators without the expense of contributing to it. To enhance legitimacy and legal certainty, private dispute resolution institutions may look to adopt approaches used in public adjudication – such as introducing greater transparencyFootnote 178 and publishing anonymized decisions or summaries of such decisions. ICSID may wish to learn from public adjudication institutions by facilitating access to legal aid to the parties as both ECtHR and the ICJ are doing.Footnote 179

5.2. Substantive legitimacy

A core element of the rule of law is the resolution of disputes by application of the law, rather than the exercise of discretion.Footnote 180 Greater consistency and predictivity of substantive law strengthens the legitimacy of a dispute resolution institution. Traditionally, an important function of domestic litigation (at least in common law jurisdictions) has been to clarify the law to guide future private actions.Footnote 181 However, international private adjudication has almost exclusively focused on the settlement of the dispute at hand, without taking into account the normative implications of their decisions. To contribute to the development of law and legal certainty, private adjudication must become more visible and depart from the default rule of confidentiality of awards.

Hybrid adjudication has shaped to a certain extent the normative expectations of both investors and host states but the lack of legal certainty on many issues has undermined its legitimacy. It has resulted in a closely-knit system of investment law, significantly removed from the reach of states.Footnote 182 While the self-contained nature of the ICSID system removes it from domestic political pressures, it also undermines the legitimacy of the system when decisions are viewed as fundamentally unfair or inconsistent. The ICSID system may want to improve consistency by introducing a selective review of the most important decisions following the ECtHR approach or by establishing a standing annulment committee.Footnote 183

When disputes affecting public policy are no longer resolved by judges with tenure but by private adjudicators insulated from court supervision,Footnote 184 that poses serious challenges to the legitimacy of the system.Footnote 185 In this context, a mechanism for setting aside fundamentally unfair awards as a result of a system of appeal or internal review could bolster the legitimacy of the procedure in a similar way as public law institutions such as ICJ and ECtHR do. A greater reliance on domestic law of host states in investor-state disputes could help the facilitation of greater legal certainty.Footnote 186

6. Conclusion

As this article has demonstrated, differences between public and private adjudication affect the legitimacy of such institutions, the rule of law, and the facilitation of legal certainty. Private and public adjudication institutions have much to learn from each other and comparative law analysis and dialogue between different institutions may help to identify the most effective procedural approaches.

It is hardly possible to make a clear distinction between permanent core and peripheral features of ‘publicness’ or ‘privateness’ of adjudication. Only by looking at the combination of key features can one make a judgement about the nature of the institution. For example, while commercial arbitration institutions (falling under ‘private adjudication’) are usually separate from states in most countries, in some jurisdictions they may be state-owned,Footnote 187 which does not automatically make the adjudicative procedure public given all other features. Similarly, a particular subject matter is not definitive to characterize a system as private or public. We have already discussed examples of how essentially the same property-related dispute may find itself in private, hybrid and public adjudication.Footnote 188

Equally, private adjudication does not have to be confidential and there is an increasing trend towards making awards in commercial arbitration more public to facilitate the development of private law.Footnote 189 Adjudication mechanism may also change over time and move towards either a private or a public end of the spectrum. For example, the hybrid investor-state arbitration has evolved from public compensation commissions by gradually acquiring more features characteristic of private adjudication.Footnote 190

However, despite these variations and changes, private and public adjudication possess a number of distinct features and their own legitimacy mechanisms. The analysis above suggests that when parties face the choice of a remedy to protect their property rights, they may resort to private adjudication to resolve disputes faster and confidentially. Private adjudication institutions are usually cheaper for the taxpayers, as the disputing parties cover the costs of proceedings.

Private adjudication institutions focus on a dispute at hand rather than on setting or clarifying the rules of conduct for future disputes. In other words, they are in an inferior position compared to public adjudication to facilitate legal certainty, secure a consistent body of case law, promote public policy goals or allow third parties to know the rules of conduct in advance to prevent undesirable activities. The transactional nature of private adjudication institutions, the lack of publicity and their much weaker law-making function prevents them from promoting reforms or socially desirable outcomes. On the other hand, public adjudication institutions have a greater capacity to serve as vehicles for reform or judicial activism to achieve socially desirable outcomes.

Legitimacy understood as acceptance of the institution by its users as operating in accordance with the rule of law is ‘in the eye of the beholder’ and depends on who is using an adjudication mechanism. The legitimacy concerns raised by states in relation to hybrid dispute resolution mechanisms, which they created, will sooner or later result in fundamental reforms on issues such as confidentiality, appointment of adjudicators, applicable law and review mechanisms.Footnote 191 If private parties no longer find a particular dispute settlement mechanism attractive or legitimate, they can switch to other dispute resolution institutions or rely on private contracts with private adjudication rather than hybrid or public adjudication.Footnote 192

Private adjudication dressed in public clothes or imposing public adjudication for private disputes is likely to perpetuate a legitimacy crisis of such institutions. Any reform, moral or economic assessment of different models of adjudication should take into account their public or private nature.