1. Introduction

Empirical analyses of the ways in which international courts cite cases has attracted growing academic interest in recent years.Footnote 1 While these studies added important new insights into the use of judicial decisions by international courts, how international courts cite academic writings as the second ‘subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law’ has remained comparatively under-explored.Footnote 2 Focusing on international criminal law, the article combines quantitative and qualitative approaches to shed additional light on the ways in which international courts have referred to academic writings in their jurisprudence. The article is based on data collected from four international and hybrid criminal courts and tribunals: The ICC, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and the SCSL.

To be sure, an analysis of the role of academics might run the danger of solely appearing as a navel-gazing exercise. Nevertheless, how influential academics are within what Oscar Schachter famously called the ‘invisible college of international lawyers’ remains contested.Footnote 3 Mark Tushnet, for example, even sees legal academics as law-makers at the international level,Footnote 4 and Ilias Bantekas argued that the ad hoc Tribunals effectively treated academic writings as a primary source of international law.Footnote 5 However, Jean d’Aspremont warned against overestimating the role of legal scholars in the international law-making process.Footnote 6 Gleider Hernández, while emphasizing the ‘outsized role’ legal academics assume in international law, points out that international courts nevertheless rarely cite scholarly writings.Footnote 7 Therefore, important questions remain unanswered: Does Hernández’ observation hold true for international criminal courts and tribunals, or has the work of legal scholars been cited more frequently in international criminal law? What functions have academic writings served in the international judicial decision-making process in practice? Drawing on new empirical insights to address these questions, this article ultimately aims to shed additional light on the role and influence of legal scholars within the development of international criminal law.

Contrary to existing studies of the citation practices of international courts that are often confined to either a quantitative or a qualitative methodology, I use a mixed-methods approach. Quantitative data was collected on the use of academic citations in 91 judgments of international criminal courts and tribunals interpreting the law of war crimes. This analysis is supplemented with insights gained from in-depth, semi-structured interviews conducted with current or former judges and legal officers working at Chambers at the ICC, the ICTY, the ICTR and the SCSL. After all, a quantitative analysis of explicit citations to scholarly work only provides a partial view of the involvement of legal academics in the international legal interpretive process.

Considering the character of academic writings as a subsidiary means and not a source of international criminal law in itself, the article demonstrates that scholarly writings are strikingly visible in the judgments of international criminal courts and tribunals. References to academic publications are particularly noticeable at the ICC, even though the work of legal scholars is not even mentioned as a subsidiary interpretive means in the Rome Statute. The article serves two primary purposes. First, based on a systematic analysis of the citations used by international criminal courts and tribunals in their interpretation of the law of war crimes, the article aims to make larger patterns visible that may have remained unnoticed in the day-to-day practice at these courts that very much revolves around individual cases. Such an analysis might ultimately be informative not only for practitioners working for international criminal courts and tribunals, but also for the parties before them.Footnote 8 Second, the article provides further reflections on the functions that academic citations serve in the international legal interpretive process and, in turn, potential implications for the role of international legal scholars.

The article begins by providing a brief overview of academic writings as a subsidiary means for the interpretation of international criminal law, and of the different functions that the writings of legal scholars are typically assumed to fulfil within the international legal system. After a discussion of the article’s methodological approach, it gives an overview of the study’s findings. While the quantitative data collected for this article may only provide a first indication, it suggests that reference to academic texts – including treaty commentaries, journal articles and academic monographs – is comparatively prevalent in international criminal law: within the analyzed judgments, academic writings even amounted to the third most frequently used citation type. The qualitative analysis then explores the situations in which judges and legal officers find academic writings to be most relevant. The article concludes by outlining some of the challenges that may result from the use of academic writings that are, in the words of one of the judges I interviewed, less ‘established [in] the traditional courtroom way’.Footnote 9 It furthermore provides some preliminary thoughts on the implications of this empirical analysis for the functions scholarly writings assume in the international legal interpretive process.

2. The roles of academic writings in international criminal law

2.1. Legal writings and the sources of international criminal law

Among the sources of international criminal law legal writings only play a minor, supplementary role. With the exception of Article 21 of the Rome Statute of the ICC, neither the Statutes of the ICTY or the ICTR, nor of the SCSL explicitly enumerate the sources these courts should rely on. However, as a subfield of international law, the sources of international criminal law are generally the same as those typically outlined in Article 38(1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice: international treaties, international customary law, and general principles of law.Footnote 10 In addition to these primary sources of international law, Article 38(1)(d) lists judicial decisions and the ‘teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations’ as additional, ‘subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law’. As ‘intermediaries’,Footnote 11 academic writings, as well as judicial decisions, in themselves consequently do not qualify as sources of international criminal law.Footnote 12 Accordingly, some of the judges and legal officers I interviewed described the writings of academics as less ‘established’Footnote 13 and not a ‘proper source’.Footnote 14

Article 21 of the Rome Statute, on the other hand, contains an overview of the Court’s applicable law. As it is well-known, Article 21(1) of the Rome Statute introduces an explicit hierarchy of applicable sources.Footnote 15 The ICC should, first of all, refer to its own Statute, Elements of Crimes, and Rules of Procedure and Evidence. As a second step, the ICC may then turn to international treaties and ‘the principles and rules of international law’, or, thirdly, general principles of law based on a review of national laws from around the world. According to Article 21(2), the ICC may also refer to its own previous decisions. Finally, the ICC’s decisions must reflect ‘internationally recognized human rights’, and should not discriminate on the basis of, among others, gender, age, or race.Footnote 16 Like the judicial decisions of other international courts, including the ad hoc Tribunals,Footnote 17 academic writings are not even mentioned in Article 21 of the Rome Statute. Therefore, at least the statutory framework of the ICC suggests that scholarly writings, while generally only a subsidiary means and not a source of international criminal law, might even play a less influential role at the ICC.

2.2. Legal scholars within the ‘invisible college’

While not a source of international (criminal) law, the writings of legal scholars nevertheless, at least to a certain degree, play an influential role in the international legal system. Scholars increasingly conceptualize Schachter’s ‘invisible college’ as an interpretive community,Footnote 18 or as communities of practice generating and re-producing epistemic knowledge.Footnote 19 As Ian Johnstone explains, in a diverse but specialized community of, among others, judges, government lawyers, diplomats, academics, and staff at civil society organizations, interpretation in international law ‘is the search for an intersubjective understanding of the legal norm at issue’.Footnote 20 For every potential member of the ‘invisible college’, participation in this interpretive process is dependent on the requirement that their views are perceived by other members to be ‘competent’.Footnote 21 In what has been called ‘co-constitution’, international lawyers therefore simultaneously shape, and are shaped by, the field in which they operate.Footnote 22 Within this intersubjective interpretive process, international courts arguably assume a particularly prominent role. In Martti Koskenniemi’s words, ‘the [interpretive] debate ends – if it ends at all – with a legally competent institution providing an authoritative view on the matter’, an observation which especially applies to international courts.Footnote 23

Within such an interpretive community, legal scholars are typically seen as fulfilling two main functions, categorized as ‘theoretical’ and ‘doctrinal scholarship’ by Sergey Vasiliev in his recent editorial;Footnote 24 both of these functions may ultimately feed back into the judicial decision-making process. First, the writings of academics are often assumed to serve a systematizing or clarifying function.Footnote 25 Jean d’Aspremont consequently called legal academics the ‘grammarians of formal law-ascertainment’, as they produce epistemic knowledge especially on what counts as international law, and what does not.Footnote 26 Through this process, legal scholars may, at least to a certain degree, be able to shape legal interpretation in international law by putting forward their own understanding of legal rules and principles, which international judges might ultimately find useful.

As a second function, Mark Tushnet points out that legal scholars may play an important role by analyzing judicial decisions from a critical perspective, potentially highlighting some of the more controversial aspects of the decision’s reasoning or uncovering a possible lack of consistency.Footnote 27 In Tushnet’s view, the aim of this type of engagement is to again feed back into the judicial decision-making process, as judges might re-think their previous interpretation based on this critique.Footnote 28 In addition to a critical treatment, legal writings might, at the very least, provide a different perspective. Accordingly, as a judge at the ICTY concluded in one of the interviews, for their work as a judge, academic publications are helpful in that they will invite reflection and will assist judges to reach a more comprehensive understanding of specific aspects.Footnote 29

At the same time, it almost goes without saying that the distinction between academics and other members of the ‘invisible college’ is often blurry in practice.Footnote 30 In 2007, a study on the international judiciary found that as many as 85 out of 215 judges at international courts previously held tenured or associate academic positions (visiting or adjunct positions were not included).Footnote 31 Compared with this overall high number for the entire international judiciary, judges with a primarily academic background seem to be slightly less represented in international criminal law: At the ad hoc Tribunals, their number noticeably decreased over time,Footnote 32 and Article 36(5) of the Rome Statute even requires that a minimum of nine out of 18 ICC judges have a substantial background in criminal law and procedure, typically through domestic experience as a judge. However, as one of the judges at the ICC pointed out, the ICC also implicitly opted to employ its own academics due to the same provision, as the remaining judges (‘List B’) often have an academic background.Footnote 33 In addition, several of the judges and legal officers working at international criminal courts publish academic articles.Footnote 34 Judges may even encourage their legal staff to publish on a particular legal issue that they have worked on at the courts.Footnote 35 Consequently, whether a text can be characterized as ‘academic’ is more often than not a statement on its format, such as its publication in an academic journal, rather than the current affiliation of the author. At the same time, frequent overlap between a more practice-oriented and a more academic career arguably produces a comparatively tightly-knit epistemic community in which members are more likely to know each other and each other’s work, a factor which, in turn, may heighten the visibility of academic writings within it.

3. Methodology

Based on a mixed-methods approach, this article relies on both quantitative and qualitative data. It begins by using a quantitative analysis of the citation practices of international judicial interpretations of the law of war crimes as a starting point. I selected the law of war crimes as a case study as the international crime that has been developed most substantially through international jurisprudence.Footnote 36 Consequently, an analysis of judicial interpretations of this international crime has the potential to be particularly insightful, given that it is not only comparatively complex but can also be expected to include a relatively high number of citations to substantiate such a development. In addition, the law of war crimes is comparatively removed from more procedural legal questions and thereby aspects that are often less transferrable across courts operating under diverging institutional frameworks. Similarly, the analysis focused on final appeals and trial judgments, which allowed for an examination of comparable material across international criminal courts and tribunals regardless of potential differences in their procedural rules. As a second step, this quantitative data is enriched with insights gained from 16 in-depth, semi-structured interviews with current or former judges and legal officers at these courts.Footnote 37

For its quantitative analysis, 91 judgments of the ICC, the ICTY, the ICTR, and the SCSL were selected as all publicly available, final trial and appeals judgments rendered by these courts between May 1997 and March 2016 interpreting the law of war crimes.Footnote 38 More specifically, the analysis included 59 ICTY judgments, 22 ICTR judgments, six SCSL judgments, and four ICC judgments. Using the data analysis software QSR NVivo, I focused on the sections of these judgments that involved a discussion of the applicable law on war crimes. The study excluded, as much as possible, any analyses of the facts or the application of legal provisions to the facts, discussions on modes of liability, as well as mere summaries of the arguments brought forward by the parties.

All references included in these sections were subsequently coded to provide a first empirical indication of the sources used across international criminal courts and tribunals. The types of document coded ranged from international treaties and treaty commentaries to international court decisions and military manuals. In other words, every footnote within a judgment’s discussion of the law of war crimes was analyzed to distinguish between the different sources used. This data consisted of a total of 8,281 citations across more than 50 different types of documents.Footnote 39 Consecutive citations to the same text were counted separately to provide an indication of the comparative frequency with which different sources were cited. In cases in which one source indirectly referred to another, the indirectly cited source was only coded separately if it constituted a separate citation, for example if it explicitly referenced a specific section or paragraph. To give an example, in a citation following the format ‘Appeals Judgment X, para. 12, referring to Trial Judgment Y, para. 50’, judgment X and judgment Y were coded as separate citations.

While sufficient to give a first indication of the use of academic writings by international criminal courts and tribunals, this data can only provide a first starting point for two main reasons. First, it bears noting that the quantitative data collected is limited due to its exclusive focus on the law of war crimes. After all, it might well be that the exact composition of the group of documents cited differs across subject areas (and individual writing styles). For example, as it will be outlined below, decisions rendered by the ICTY as well as treaty commentaries prepared by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) are likely to be particularly prominent within the interpretation of the law of war crimes.Footnote 40 However, this does not necessarily imply that the types of documents cited – such as court judgments, international treaties, or treaty commentaries – will differ across subject areas as well. Nevertheless, references to some types of documents may have been more frequent in this area of international criminal law because it has seen a relatively high level of judicial development, which is a possibility that I will return to in the conclusion.

As a second limitation, a judgment’s citations arguably serve a distinct, outward-facing role: Christopher McCrudden, for example, argues that citations are a way for judges to justify and de-politicize their conclusions, as judges ‘establish the relative autonomy of … law through the sources of authority and style of judgment’.Footnote 41 Therefore, it might be the case that a type of legal text that is perceived as less authoritative, such as scholarly writings, is ultimately not cited in the final judgment. If academic writings were nevertheless frequently consulted during the judgment-drafting process, a quantitative analysis of a court’s citation practices would provide an incomplete picture of their prominence within the interpretive process. Finally, it should be added that the SCSL and the ICC have produced a limited number of judgments to date, which prevents any meaningful comparison of the total number of citations used across courts.

Due to these potential limitations, the article contextualizes this data by drawing on 16 in-depth, semi-structured interviews that I conducted with former and current judges and legal officers working at Chambers at the ICC, the ICTY, the ICTR, and the SCSL. As part of a more general discussion, interviewees were asked to what extent, and in which situations, academic writings were relevant for their everyday work. To achieve a roughly equal distribution across different courts, I conducted interviews with two judges at the ICTR, three judges at the ICTY, two judges at the ICC, and one judge at the SCSL, as well as three legal officers at the ICTR, two at the ICTY, and three at the ICC. At the same time, judges were selected to achieve a roughly equal distribution between judges trained in different legal traditions (and namely across common law, civil law, and other or mixed legal traditions), even though judges from common law traditions were slightly underrepresented. Legal officers at Chambers were interviewed due to their often significant involvement in the judgment-drafting process at international criminal courts and tribunals: At the ICC, the ICTY, and the ICTR, it is frequently the case that legal officers prepare a first draft of the judgment based on the judges’ instructions, which judges review and amend.Footnote 42

4. Legal academics and the judicial development of international criminal law

4.1. Citations to academic writings in the judicial interpretation of the law of war crimes

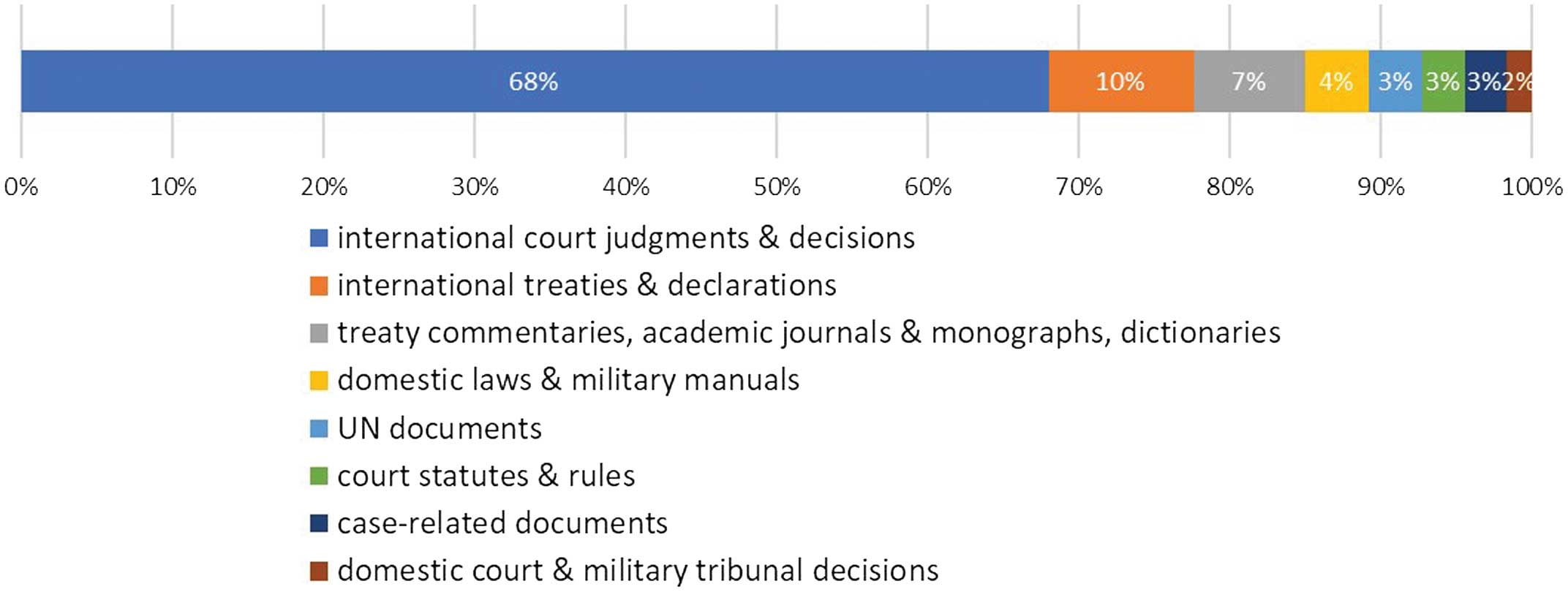

While neither judicial decisions nor academic writings qualify as a source of international criminal law, the referencing practices of the ICC, the ICTY, the ICTR, and the SCSL in their interpretation of the law of war crimes paint a different picture. In particular, judicial decisions of international courts featured dominantly in the citation practices of all of these courts: As Figure 1 illustrates, 68 per cent of the eight most frequently cited documents were international court decisions. Even though no formal rule of precedent exists at the international level,Footnote 43 this data emphasizes the highly influential role previous decisions of international courts play in international criminal law. It reflects Stewart Manley’s findings in his study of the citation practices of the ICC in the Central African Republic and the Uganda situations, in which persuasive cases constituted between 71 and 91 per cent of the references used in decisions rendered by the ICC’s Pre-Trial, Trial, and Appeals Chamber.Footnote 44

Figure 1: Eight most frequently cited types of documents (ICC, ICTY, ICTR, SCSL), in categories

Nevertheless, scholarly writings and commentaries were still notably visible in the judicial interpretation of the law of war crimes. As Figure 1 indicates, while references to judicial decisions by far overshadowed the use of any other group, academic writings were cited regularly. Academic writings – broadly understood as including treaty commentaries, academic journals and monographs, and dictionaries – even constituted the third largest group among the eight most frequently cited types of documents. Amounting to 7 per cent of the most frequently cited groups, academic texts were referred to almost as often as international treaties and declarations (10 per cent). In addition, academic writings were cited four times as often as domestic court and military tribunal decisions, and almost twice as much as domestic laws and military manuals.

While a first starting point, this categorization of both international court judgments and decisions and academic writings is rather general. After all, treaty commentaries and academic articles and monographs are somewhat different in character.Footnote 45 Consequently, Figure 2 provides a more detailed analysis that distinguishes between citations to different types of academic publications (and judgments). As probably the most striking element, Figure 2 emphasizes the prominent role of ICTY decisions and judgments, arguably reflecting the tribunal’s pioneering role in the interpretation of the law of war crimes.Footnote 46 Regarding academic writings, Figure 2 highlights the relative importance of treaty commentaries, which in this more detailed representation was the fifth most frequently used group (422 citations). Academic articles and monographs, in turn, were still the tenth most frequently used type of document (154 citations), and were therefore cited more often than, for example, domestic court judgments (113 citations).

Figure 2: Most frequently cited types of documents (ICC, ICTY, ICTR, SCSL), detail view

Notably, as Figure 3 demonstrates, the use of academic articles and monographs – also vis-à-vis treaty commentaries – is even more pronounced at the ICC, despite the lack of an explicit inclusion of academic writings in Article 21 of the Rome Statute. The ICC referred to academic articles and monographs almost as often as to ICTY trial and appeals judgments and international treaties (other than the Rome Statute). This data indicates that, at least in its initial judgments interpreting the law of war crimes, the ICC has assumed a more academic approach than the ad hoc Tribunals and the SCSL. This conclusion is also supported by Manley’s study on the ICC’s citation practices in the Central African Republic and the Uganda situations. Without exploring the ICC’s use of academic publications further, Manley’s data indicates that treatises, dictionaries, and journal articles together constituted either the second or third most frequently cited source, with percentages reaching up to 11.8 per cent at the Pre-Trial Chamber.Footnote 47

Figure 3: Most frequently cited types of documents (ICC), detail view

However, at least among the limited number of final judgments delivered by the ICC to date, the use of academic articles and monograph noticeably decreased over time, from 30 citations to academic journals and monographs in the Lubanga Trial Judgment to no academic citations at all in the Bemba Trial Judgment.Footnote 48 While potentially reflecting an increasingly settled jurisprudence on the law of war crimes, it remains to be seen how the ICC will refer to academic publications in the future. For now, however, the ICC’s current emphasis on academic writings has also been noted by some of the court’s practitioners. In one of the interviews, an ICC judge even expressed dissatisfaction with what they perceived as an overly academic drafting style. In their view, giving too much attention to legal details that may ultimately be more of an academic, rather than of practical interest, might be unnecessarily time-consuming and distract from the main purpose of the court, namely to reach a decision in the case brought before it.Footnote 49

4.2. Beyond citations: The unseen use of academic writings

Compared with the quantitative data, the interviews indicate that an analysis of the types of legal documents explicitly cited in international judgments may actually underestimate the role academic writings play in the judicial development of international criminal law. Three of the eight legal officers interviewed for this project explained that, while they would engage with academic writings as part of their work at Chambers, they would be hesitant to cite them. In the words of a legal officer at the ICTR, ‘I would say … very rarely, [academic writings] would make it into a footnote in a judgment … it’s not a proper source, really’.Footnote 50 According to a legal officer at the ICC, scholarly writings are:

helpful to sort of help you grapple with an issue … I think in terms of citing it, you don’t – if there’s something else … I wouldn’t necessarily do that. But I do think you do read a lot. I think academics actually have a huge impact in the work of the court.Footnote 51

However, the interviews reveal that judges and legal officers are prone to refer to the work of academics in three particular types of situations. First, reflecting the status of academic writings as a subsidiary means and not a source in itself, several judges indicated that they would refer to scholarly writings as a last resort should few alternative sources, including judicial decisions, be available. According to a judge at the ICTR:

being a judge by profession … my inclination is always to see to case law rather than to legal writings, so that will be my priority … So that’s when you have a choice. If you have no choice, and there is a lacuna, I assume that of course legal writings will give support for the – for a certain result.Footnote 52

Second, and in line with the idea of legal scholarship serving a clarifying function, judges and legal officers refer to academic publications to inform their thinking on particularly complex or new legal questions. Consequently, judges and legal officers stated that they would be particularly likely to seek academic input on aspects that are novel and for which it is still unclear how they should be approached.Footnote 53 Therefore, one of the legal officers I interviewed indicated, for example, that they would refer to academic writings when attempting to gain further insights on legal questions that are extraordinarily difficult and ‘thorny’.Footnote 54 Similarly, another legal officer explained that legal scholarship was useful when considering what they called ‘higher conceptual problems’, such as questions on the hierarchical relationship between specific legal provisions.Footnote 55

Third, academic sources are used to gain a first overview of the legal framework and discussions on a particular issue. As a legal officer explained, academic publications can be:

a good starting point. And I think for a lot of people it’s that … If you come across an issue and you’re not quite sure how to start thinking about it … academic articles are a good starting point for getting yourself into the broad overview.Footnote 56

Similarly, another legal officer indicated that they might review academic publications to ensure that no important aspects were overlooked.Footnote 57

At the same time, however, how judges assessed the use (and usefulness) of academic writings often seemed to have been a question of individual style that was, interestingly, not necessarily linked to whether these judges themselves held tenured or associate academic positions in the past. As mentioned above, one of the judges at the ICC even viewed abundant references to academic writings as potentially problematic.Footnote 58 Two of the judges interviewed concluded that academic publications had little importance for their work, even though they would, if necessary, occasionally refer to scholarly writings or standard academic texts.Footnote 59 On the other hand, two other judges chose to highlight the importance of scholarly writings.Footnote 60 A judge at the ICTY, for example, regarded especially the academic debate on modes of liability as crucial for their work.Footnote 61

Despite these differences, academic writings overall seem to play a more influential role in the judicial interpretative process than its characterization as a subsidiary means indicates. This is not to suggest that this development necessarily challenges the independence of international criminal courts and tribunals. When discussing the importance of academic writings for their work, several judges and legal officers either implied, or explicitly emphasized, that academic publications are just one out of several sources they refer to,Footnote 62 and that they do not necessarily find the suggested analysis convincing.Footnote 63 In the words of a legal officer at the ICTR, ‘[i]t’s not that we rely on what they [academics] say, but at least we read it’.Footnote 64

5. Implications for the role of legal scholarship

Based on these empirical insights, the following section will turn to some preliminary reflections on possible broader implications. To begin with, and perhaps unsurprisingly, the judges and legal officers interviewed for this article laid particular emphasis on the first, systematizing and clarifying function of international legal scholarship. Judges and legal officers suggested that academic writings are most relevant for their work if they concern exceptionally complex or novel legal questions, which implies that academic writings may provide guidance in an area in which the legal framework is unclear. Furthermore, the view that scholarly writings can give a comprehensive overview of, and orientation within, the interpretive landscape on a particular question similarly resonates with the systematizing function of legal scholarship.

Therefore, the interviews suggest that, through this systematizing and clarifying function, academics might indeed at times have the opportunity to indirectly shape international legal content. Such a dynamic is arguably particularly prevalent in international criminal law, a still comparatively new and skeletal branch of international law. Accordingly, judges and legal officers interviewed explained that in their daily work, they repeatedly encounter instances in which legal provisions were unclear.Footnote 65 The specific structure (and relative youth) of international criminal law, while in constant tension with the nullum crimen sine lege principle, therefore likely at least in part accounts for the comparatively high number of citations to academic sources across different international criminal courts and tribunals. This conclusion is also supported by the statements of judges, who explained that they would only refer to academic writings as a measure of last resort when considering legal aspects for which few other sources were available. Consequently, it follows that references to academic writings can be expected to decrease over time. At least on a preliminary basis, this argument is supported by the analysis of citations used in the limited number of judgments the ICC has delivered so far.

Nevertheless, for now, academic writings seem to be more visible, and potentially more influential, within the interpretive process at international criminal courts and tribunals than their characterization as a subsidiary means suggests. Such a heightened role of academic writings also entails a number of potential challenges. Several of the legal officers interviewed expressed hesitancy about the use of scholarly writings in international judgments,Footnote 66 which reflects the characterization of academic writings as potentially relevant, but as not constituting a ‘proper source’.Footnote 67 This implicit caveat was also reflected by the noticeable differences between individual judges in their assessment of the relevance of academic publications for their everyday work. As mentioned above, one of the judges at the ICC even suggested that an overly academic writing style could have negative implications, as it may unnecessarily prolong the drafting process and ultimately negatively impact on the court’s efficiency and its ability to reach a timely decision.Footnote 68

A second potential challenge concerns the ways in which academics may critically engage with judicial decisions. Based on the interviews, it is noticeable that, compared with the idea that scholarly writings may serve to clarify and systematize legal concepts, judges and legal officers placed less emphasis on this second, critical review function. Strikingly, a legal officer at the ICTR even suggested that it was ‘important to keep a square’ around the court’s legal work, and that academic publications can, at least to a certain extent, be part of the ‘noise’ that needs to be kept out.Footnote 69 This perspective suggests that at least for some practitioners, academic writings are seen as a potentially problematic outside influence, a view that is in tension with the possibility that scholars might provide constructive criticism and point out potential weaknesses. One of the judges at the ICTY, on the other hand, seems to have acknowledged this critical review function when arguing that scholarly writings are helpful because they invite reflection.Footnote 70 Furthermore, several of the judges and legal officers indicated that they are in fact often aware of academic commentary on recent court decisions – and specifically decisions that they worked on – even though they may not necessarily agree with it.Footnote 71 To the extent that judges and legal officers follow legal writings, academic contributions therefore at least have the potential to provide critical assessments, and may, in some cases, lead judges to question or revisit specific aspects.

In this context, even though arguably a relatively straightforward point, it might be worth emphasizing that the form of scholarly critique discussed here, under the heading of a critical review function, is of a comparatively limited nature. Frédéric Mégret called this type of critical engagement ‘accompaniment criticism’, a form of critique that does not criticize the international criminal justice project itself, but rather, from a more pragmatic perspective, the way in which it is implemented.Footnote 72 Therefore, it is often distinct from – and considerably more limited in scope – than the important insights that can be gained from scholarship broadly forming part of a critical academic project drawing on, for example, feminist or TWAIL (Third World Approaches to International Law) critiques.Footnote 73 Consequently, within the daily work at international courts that is subject to significant time-constraints, a focus on a particular subset of academic criticisms in a sense may, far from limiting outside influences, inadvertently serve to shield practitioners from other important types of critical engagement.

At the same time, the article’s empirical analysis emphasizes the rather tangible role that academics may play in the international legal interpretive process, a conclusion that holds important implications for the responsibility of legal scholars. On the one hand, this potential influence of legal scholars seems to leave room for some academics to successfully promote their own specific interpretations, a development that Elies van Sliedregt called ‘norm entrepreneurialism’ in her recent editorial.Footnote 74 In addition to potentially creating a ‘hodge-podge of law’,Footnote 75 this development might make it even more important to empirically research – and potentially critically assess – which scholars within the ‘invisible college’ are able to play such an influential role. As a first step in this direction, it is noticeable that many of the academic writings cited in the judgments analyzed for this article were produced by current and former employees of these courts. As noted above, significant overlap exists between more academic and more practice-oriented careers, making such a distinction at times difficult to draw. At least as a first indication, however, the Rome Statute commentaries frequently cited to by the ICC, for example, rely in large parts on the contributions of practitioners who gained practical experience at international and hybrid criminal courts or the ICRC, or who participated in the negotiations of the Rome Statute.Footnote 76 Among the academic monographs and journal articles cited by the ICC, only about half (26 out of 49) were at least co-authored by individuals with a full-time university affiliation who were not previously employed by an international criminal court or tribunal.

It might well be that this development occurred because individuals who are able to draw on their prior practical experience are more likely to publish on issues that are more applicable to the day-to-day work of international criminal courts and tribunals. In addition, among the academic publications written by practitioners, a further distinction could be drawn between practice-inspired scholarship more generally and academic writings explicitly discussing the negotiations of the Rome Statute, which arguably serve a slightly different, albeit nevertheless potentially influential function within the interpretive process. Finally, publications written by employees at international criminal courts and tribunals might provide important opportunities for cross-fertilization across different chambers and courts. For example, a legal officer at the ICTY explained that reading an article published by a colleague working at the same court enabled them to gain a new perspective on a specific legal aspect.Footnote 77 At the same time, however, in a situation in which employment at international criminal courts and tribunals is limited to a relatively small – and lately rapidly decreasing – number of individuals,Footnote 78 the circle of individuals who may offer such a new (or critical) perspective necessarily shrinks. Furthermore, as this group is consequently more likely to share a similar set of experiences, the resulting scholarship might be less likely to provide an outside perspective that – returning to an interview with one of the judges at the ICTY – is able to invite reflection.Footnote 79

6. Conclusion

Both the quantitative data of citations to academic writings and the qualitative interviews with judges and legal officers indicate that scholarly contributions play a more influential role than its formal categorization as a subsidiary means implies. In international criminal law as a subfield in which international courts and tribunals have played a particularly prominent role in the development of legal rules and principles,Footnote 80 this room for judicial creativity also seems to have indirectly opened a door for legal scholars to play a more prominent part in the interpretation, and potentially making, of international law. Inspired by Jakob v. H. Holtermann and Mikael Rask Madsen’s European New Legal Realism,Footnote 81 further research could therefore shed additional light on which individuals or groups of academics are particularly influential within the ‘invisible college’ and the judicial decision-making process.Footnote 82

This is not to suggest that the role of academics should be overestimated: For example, the article’s analysis of the citation practices of criminal courts and tribunals revealed that academic citations were by far outnumbered by references to judicial decisions. As several of the judges and legal officers emphasized, while they might engage with academic writings, they often do not agree with them. However, the hesitancy of some legal officers and judges to explicitly cite scholarly publications in their submissions and decisions also suggests that a quantitative analysis underestimates the role of academic contributions in the judicial interpretive process. Indeed, such a hesitancy points to an important tension expressed by judges and legal officers, that is, between the potential benefits of academic publications as providing insightful systematizations and critique and their categorization as not part of the ‘established’Footnote 83 sources. This tension seems to be reflected in the diversity of assessments of the usefulness of academic publications that judges and legal officers provided, which ranged from the view of academic writings as highly constructive to the criticism of such citations as unnecessary and distracting.

Furthermore, this research suggests that such a potential reach of academic writings in international criminal law is at least in part rooted in the relative youth of the field, as legal practitioners are more inclined to look to academic work as a last resort and to solve particularly complex legal issues. Therefore, the number of references to academic writings can be expected to decline as the courts’ case law becomes more settled. In accordance with this suggestion, when asked about the use of legal sources in an interview I conducted more than 20 years after the tribunal was established, one of the legal officers at the ICTY observed that ‘now the Tribunal is mature enough that it looks to its own’.Footnote 84

Consequently, this analysis also points to some more general conclusions on the potential for normative innovation in international law, and the role that different parts of the legal interpretive community play within it. Based on a comparison between the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the Andean Tribunal of Justice (ATJ), Karen Alter and Laurence Helfer theorize that international courts need to be encouraged to engage in expansionist judicial law-making, with legal scholars being among those who may push for such a development.Footnote 85 The analysis conducted for this article suggests that in addition, legal scholars also generally play a more influential – and potentially innovative – role in an international court’s early years when judges are less able to rely on an established jurisprudence.Footnote 86 Consequently, further important insights could be gained by tracing whether this trend indeed continues within the ICC’s judicial decisions as the court builds up its own jurisprudence, and whether a similar decrease in citations to academic writings exists beyond international criminal courts and tribunals and across international courts more generally.