1. Introduction

The axiom that states are bound by the international law that they themselves make as equal sovereigns participating in the international sphere is at the centre of mainstream approaches to our discipline. This state-centric, voluntarist narrative, reproduced widely in sources literature, veils the importance of other factors in the making of international law, such as the prominence of an ‘invisible college of international lawyers’ (hereafter the college or ‘the invisible college’). While many problems emerge from the college’s invisibility, this article is concerned with our own incapacity, as international lawyers, to see and question the college’s power and homogeneity.

We will use obituaries of renowned international lawyers published in the British Yearbook of International Law (hereafter BYIL or Yearbook) Footnote 1 to map the ‘invisible college’ through social network analysis (SNA). Footnote 2 Our portrait of the international legal profession Footnote 3 shows, for the first time, relationships between groups of individual international lawyers with similar educational and professional characteristics, and the interconnectedness between groups that form the community as a whole. Network analysis also illuminates patterns in career progress, and how lawyers move between the roles of academic, government lawyer, advocate, and sometimes judge or ILC member. This analysis gives empirical backing to hitherto anecdotal accounts of how the profession in international law promotes a dedoublement fonctionnel, Footnote 4 and allows for a unique picture of the college. The portrait revealed in our network of lawyers is much more vivid than the partial glimpses provided by anecdotal evidence, not only because of its size but also because of the long historical trajectory that it depicts. Obituaries give us a distinctive prism, and thus constitute a powerful tool of analysis. With the exception of the more ad hoc Liber Amicorum, memorial conferences, and acknowledgments in books, obituaries are the only standardized forum where international lawyers elaborate publicly about one another’s personal connections, professional achievements, and individual contributions to substantive law. Footnote 5 The network sketched here does not purport to be the final word on the subject or provide a numerus clausus list of the ‘invisible college’ – the dataset is, after all, based on a national Yearbook, and is thus warped towards the British experience of international lawyering. To this we first propose our work be read in light of and in tandem with other works on the profession that use more traditional sources to sketch out sectors of international legal practice. Footnote 6 Secondly, we ask the reader to take a leap of faith and embark with us as we take the ‘dead white men’ trope to an extreme, providing subversive insight into a profession that purports to be an impersonal expert science. Footnote 7 Our work should be read instead as an alternative and playful means of unveiling connections between members of the international legal profession that highlights the personal nature of the discipline – more than studies that depict networks of rosters or map citations, obituaries unveil the intimate connections, amities and even enmities – and thus further remind us that our discipline is made of ‘people with projects’. In privileging creativity over formality, Footnote 8 we seek to produce work that is experimental, and thus ‘not bulletproof’, ‘but reliable’, Footnote 9 harnessing our ability to connect with personal elements of the discipline, nurturing the ‘emotional life’ Footnote 10 of our work, and open us up for the ‘kaleidoscope of possibility’ Footnote 11 dormant in our professional practices. By painting a richer picture of the ‘invisible college of international lawyers’ that cuts across professional strands and sheds light on personal ties, our work bolsters claims for transparency, responsibility, ethics, and for more diversity in the international legal profession in a way that captures the imagination.

1.1 Schachter’s ‘invisible college of international lawyers’

The term ‘invisible college of international lawyers’, ‘one of the most popular descriptions of our profession’, Footnote 12 was first coined by Oscar Schachter in a 1973 piece commemorating the centenary of the Institut de Droit International Footnote 13 and later on expanded in a discrete journal article. Footnote 14 Although Schachter’s 1973/7 articles explored issues such as interdisciplinarity and the specialization in the profession, his most long-lasting point is that in the course of their multiple duties and roles, international lawyers perform a legislative role by transporting ideas between institutions. Alternating between official and unofficial roles, they informally weave a ‘sense of justice’ into international law, without the consent of states. This ‘sense of justice’, or ‘conscience juridique’, would not be present, says Schachter, if international law depended exclusively on states’ will. He argues the vehicles for inserting this conscience juridique into international law include ‘non-legislative resolutions’ and ‘reports/proposals by non-binding authoritative bodies’, but also judgments, ILC documents, arguments made by advocates before international courts, and reports of international organization expert bodies such as those issued by Special Rapporteurs and Commissioners in human rights organs. Footnote 15 In summary, Schachter’s argument, to which we subscribe, is that international law is not only propelled by states, but also by members of the invisible college since (i) in the absence of a central legislature the system is highly decentralized and heavily reliant on custom and social practices, and (ii) the profession not only allows but encourages individuals to move between different authoritative roles. The modern rediscovery of the concept of ‘invisible college’ transposed by Schachter to international law is to be ascribed to the American sociologist Diana Crane, Footnote 16 who was in turn influenced by Derek de Solla Price’s work on networks of citations between scientists. Footnote 17 Schachter and subsequent generations of international lawyers that appropriate his iteration of the concept, however, incorporate it as ‘folk’ terminology to capture the profession’s club-like nature – some also describe the profession in the equally a-technical (and less neutral) term ‘mafia’. Footnote 18

It may seem ironic that we chose to expand upon the iteration coined by Schachter, a card-carrying member of the invisible college, who adopted the term to describe a tout court invisible college institution, the Institut de Droit International. Schachter’s model remains useful, but while the notion of an invisible college has since been accepted by the discipline, Footnote 19 the international law literature still falls short of explaining this phenomenon, perhaps because membership to the college almost immediately results in naturalization of the phenomenon. Schachter himself does not explain how the invisible college functions, nor does he trace the different professional roles between which individual members of the profession transition. Instead, he only comments on the move between academia and governmental advice, overlooking other sides of the profession such as judgeships and ILC membership. Some useful revisitations of Schachter’s concept focus on sections of the profession to explore the diversity or impact of members of the ‘invisible college’ – Anne van Aaken, Footnote 20 for instance, explores the invisible college of arbitrators, whereas Gleider Hernandez looks into the role of academics in streamlining the profession. Footnote 21 Looking at these separate ‘rooms’ within the college, however, negates Schachter’s central thesis – that individual influence is bolstered by the unique fluidity of the international legal profession. The same people transition between the separate rooms that make up the college – the academy, law office, government department, arbitration panel, and international bench. It is in these transitions that lawyers weave a ‘sense of justice’ into international law. Those who do look at the full blueprint of the college, on the other hand, have relied mostly on a few anecdotal accounts. Santiago Villalpando updates Schachter’s argument for the twenty-first century, exploring the transitions between ILC membership, scholarship, and legal counsel through the example of James Crawford, the defence of necessity, and the Articles on State Responsibility which he helped construct. Although this is a useful starting point, the comprehensive picture of the profession provided in this article is Villalpando’s puzzle writ large. Andrea Bianchi’s reflections on epistemic communities, Footnote 22 or Michael Waibel’s interpretive communities, Footnote 23 support this work’s assumptions that the social groups in which individuals organize themselves matter for the content of the law. Their focus, however, is on explaining why these groups have power in either knowledge production or interpretation. Our work differs in that it seeks to answer the prior question of who the interpreters and knowledge-producers are, and what sensibilities and biases they carry with them.

In light of the recent ‘turn to history’ in international law scholarship, there has been a growing interest in scrutinizing our profession.Footnote 24 There are similarities between Schachter’s concept of an ‘invisible college of international lawyers’ and contemporary works on the profession such as Martti Koskenniemi’s Gentle Civilizer of Nations (Gentle Civilizer).Footnote 25 Both put international lawyers at the forefront of the development of international law. Schachter’s ‘sense of justice’ is related to Koskenniemi’s concept of ‘sensibilities’ explored in Gentle Civilizer, and the former’s plea against specialization is akin to the latter’s critique of managerialism. In this sense, both represent calls for international lawyers to reconnect with or reflect upon ‘broader aspects of the political faith, image of self and society, as well as the structural constraints within which international law professionals live and work’.Footnote 26 However, while The Gentle Civilizer explores the role of individuals, notably the ‘men of 1873’, as creators of the discipline, Schachter’s article is more concerned with lawyers’ influence in the making of positive law. This article weaves these two strands together, filling gaps which both Schachter and Koskenniemi have left open. By focusing on the core of the community, we help uncover the concentration of powerFootnote 27 therein, as well as its lack of diversity.Footnote 28

1.2 Invisibility in sources debate

The backdrop of this work on obituaries is that international lawyers’ contributions are not recognized in sources literature. If we look at the sources literature approach to ‘teachings of the most highly qualified publicists’ in Article 38 of the ICJ Statute, the embodiment of one aspect of individual participation, we see that it is often dismissed as a nineteenth-century relic. Sources literature rejects the importance of ‘teachings’Footnote 29 primarily because states are most evidently not involved in their production, and state-centrism is an axiom of traditional approaches to our discipline. Portraying international law as ‘real law’ that can be objectively distilled by a neutral observer is at the core of the project of positivism in international law,Footnote 30 and acknowledging a role of individuals in law making is diametrically against this. In obituaries, however, the influence of individual lawyers is not only freely admitted, but celebrated. Indeed, some deny the role of individuals in their scholarship while simultaneously acknowledging the individual role on an ad hoc basis when writing obituaries. Compare, for instance, Sir Michael Wood’s ‘Teachings of Publicists’ entry in the Max Planck EncyclopaediaFootnote 31 with his position expressed in the obituary of Sir Ian Sinclair jointly written with Sir Frank Berman.Footnote 32 In the former, Wood states that writers’ influence lies in promoting ‘better understanding’ of the law rather than ‘dictating’ it. Their writings are ‘evidence’ rather than a ‘source’ of law.Footnote 33 Yet in reflecting on Sinclair’s time spent at the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), Wood does not fail to concede that he ‘played a significant role in the recognition of the [commercial exception to state immunity] doctrine in international law’.Footnote 34 The rejection of the importance of individual professionals in sources literature cannot stand the scrutiny of a case study. Obituaries – as windows into the invisible college ‘club house’ – are one of the best sources to debunk this positivist myth.

More than in domestic legal systems, international law is to a large extent moved by internationally-minded individuals. Whereas some want to promote liberal ideals and constrain states’ actions through law, Footnote 35 others may seek to utilize their position to broaden the power of the(ir) state vis-à-vis their citizens or weaker nations. This internationally-minded community is small, and thus its power is amplified. Unlike national legal systems where institutions are numerous and equipped by large bureaucracies, those who work in international law are comparatively few. This small roster of individuals is relatively untethered due to the absence of overarching institutions regulating the profession. Footnote 36 Although the ‘club’ may have specialized and broadened with the proliferation of international institutions, white men from the developed world are still the majority of its members. Footnote 37

2. Methodology

2.1 The relationship between method and a research question

Obituaries are overlooked in international law scholarship beyond the odd biographical reference. Footnote 38 However, much like the acknowledgements section of a book, Footnote 39 the obituary departs from the detached language of academic work, allowing us to peer behind the veil of a seemingly expert science. Bearing in mind their particularities as a genre, the possible tendency to over-congratulate the subject, and the belief that ‘one does not speak ill of the dead’, read carefully and systematically obituaries can be very revealing, and historically and sociologically relevant. Footnote 40 The heartfelt and somewhat informal nature of these writings offers us a unique glimpse into the lives of international lawyers: who their mentors, successors, colleagues, and friends were, Footnote 41 as well as which positions they occupied at which time and what the exact nature of their contributions were. In other words, obituaries, however obsequious, offer evidence of deeds and relationships – unstructured, but very meaningful data – which can be employed fruitfully to map out the field. Moreover, while similar information could be collected through interviews, obituaries provide distinct advantages: first, their sheer volume and historical span (1920 to the present day in the case of the Yearbook, amounting to 58 obituaries in total), supplements what could be realistically obtained with interviews with such diverse individuals and on such a diverse range of topics. Second, information provided in obituaries is possibly more reliable and less prone to confirmation bias than that which could be obtained in interviews: unlike an interviewee who responds to – or, evades – a question, here all the information is provided freely by the obituary’s author, often more candidly than one would expect from such a genre. Footnote 42 Third, obituaries contain evidence concerning relationships of an official nature, which could be reconstructed from official records, but also provide a more colourful and detailed picture. Indeed, we argue that it is often the more informal ties are a fundamental feature of the invisible college. Diana Crane, who inaugurated the study of the ‘invisible college’ in sociology, confirmed the importance of connections and communication between scientists by looking at evidence far more informal than citations, which obituaries allow us to do. An example of the type of informal ties systematically available in obituaries, for example, is the parallel development in the careers of Sir Ian Brownlie and Sir Derek Bowett, Footnote 43 Sir Francis Vallat’s ‘unconventional and progressive’ championing of the careers of women such as Eileen Denza and Joyce Gutteridge at the Foreign Office, Footnote 44 or the friendship between the aforementioned Gutteridge and Gillian White. Footnote 45 Although sometimes similarly personal and revealing in nature, and definitely useful for qualitative research on the profession and its professionals, Libri Amicorum/Festschriften are less homogenous in content, as they are organized ad hoc and not as part of a series. They are often less concerned with personal histories and professional paths and more concerned with the substance of the law itself, thus wielding less information about human relationships. A systematic study such as this benefits from obituaries’ continuity in format. Footnote 46

We anticipate objections regarding the scope and size of the dataset, which may be deemed incomplete, either because not all important international lawyers have their obituaries published, or because the decision to publish one’s obituary may be due to personal proximity to the editors rather than merit or intellectual significance. In response, we argue firstly that our claim is not one of completeness, but of disruption. Our use of social network analysis does not purport to share the same rigour that sets apart other studies employing it. Beyond some elementary ranking and partitioning, the present endeavour does not take advantage of techniques commonly used in SNA, such as the determination of centrality measures,Footnote 47 the network’s overall density,Footnote 48 or its clustering.Footnote 49 This choice is partially imposed by the nature of the dataset, which is inherently partial and would inevitably import biases in our analysis if mathematical measurements of this kind were to be deployed directly. Rather, we use social network analysis in a more impressionistic, and even playful fashion. While acknowledging the limitations of this approach on the basis of the relatively limited dataset, we insist on using SNA because it provides a unique and subversive insight, drawing the reader’s attention to a phenomenon that is, to some extent, self-evident for those at the centre, but to which the periphery does not have access. We do so by relying on a respected, mainstream channel of communication and restructuring the information it conveys through SNA, thereby confronting the centre with its own self-reflection. Thus, our approach must be seen as an effort to bring to light latent patterns in ways that would be difficult to accomplish otherwise. It does not clash with – and, indeed, complements – other efforts aimed at better understanding the complexity of social and professional networks and the importance of the personal element in the field of international law, be they based on the use of SNA,Footnote 50 citations to authority,Footnote 51 or the determination of consensus.Footnote 52

We believe that self-selectivity enriches, rather than limits, this study. Whose lives are worth memorializing in itself speaks volumes as to how the group operates at a social level. If we employ the term ‘invisible college’ by embracing the personal alongside the professional, and how it is the interplay of both that allow for the bolstering of an individuals’ authority within the group, obituaries give clues about the biases and patterns of dominance that are of interest here. Who these obituaries do not memorialize – women, non-white scholars, scholars from the Global South – is indicative of whose lives matter enough within the community for their deaths to be acknowledged, Footnote 53 and thus whose voices were likely to make an impact during substantive discussions. This is especially relevant in light of the inclusion, however occasional, of non-British jurists – very much exceptions proving the rule. Footnote 54 International law has a long history of individual contributions from the global South in the highest echelons of scholarship and practice. Yet, even if one were to adopt an approach as selective as that of the obituaries we consider, the absence of key writers such as Alejandro Alvarez, Christopher Weeramantry, and Eduardo Jimenez de Aréchaga is striking. Footnote 55 Felice Morgenstern and Suzanne Basdevant Bastid as prominent women are also absent from this roll. Footnote 56

The Yearbook’s tradition of publishing obituaries, its long span of publication, and the wide representation of British institutions in the high echelons of the profession reinforce the relevance of our dataset. Indeed, the first substantial pages of its first edition are occupied by an obituary of Lassa Oppenheim, one of the Yearbook’s founders, although his premature death did not allow him to see the Yearbook to fruition. Footnote 57 This is in contrast with the longer-running Revue Générale de Droit International Public et Comparé (1894–present), which between 1894 and 1946 published less than ten obituaries, three of them for one of its first editors, the legal historian Paul Fauchille. Footnote 58 The BYIL has published pieces on the lives of prominent international lawyers consistently throughout its span of publication, amounting to a total of 58 shorter obituary notes and notices (between 1–12 pages) and 16 longer articles dealing with more substantive aspects of the work of deceased international lawyers. Footnote 59 Second, spanning almost a century, the BYIL is one of the oldest international law journals in the world, and the oldest British journal focusing solely on international law. Footnote 60 Alongside publications such as the American Journal of International Law (AJIL) (1907–present), the Revue Générale de Droit International Public et Comparé (1894–present), it is one of the longest-running international law journals still in print, Footnote 61 informing, being informed, and recounting the lives of several generations of international lawyers. Moreover, as other empirical studies have suggested, British institutions such as the universities of Cambridge and Oxford, as well as the University of London, occupy an important place among the elite educational centres with significant representation of its faculty and alumni in international institutions and, even more so, the ‘international judiciary’. Footnote 62 Accordingly, the quintessentially British nature of the Yearbook as an institution is not incompatible with and, in fact, is conducive to the understanding of the making of the community of practice under investigation.

We recognize that, despite not being made up exclusively of British individuals, our network’s reliance on the Yearbook privileges the British experience. There are also temporal issues that restrict the breadth of our dataset. By their very nature, obituaries provide evidence of the landscape as it was when the subjects were professionally active. Issues such as the increased institutionalization of international practice with the proliferation of international tribunals since the 1990s, the specialization of international legal practice, potential changes in the composition of the invisible college, and the rise of international private practice are likely to be more prominent than our study suggests.

However, we maintain that our analysis contributes to a greater understanding of the internal dynamics of the international legal profession that stand scrutiny and deserve to be publicised. It must not be read in a vacuum, but as a piece of the puzzle of a larger landscape making up the body of literature on the profession, such as network analysis of professional rosters, or histories of sections of the profession.Footnote 63 Although these studies provide greater contemporary insight and geographical breadth, they lack information about informal links amongst international lawyers, such as mentorships, friendships, rivalries, and lines of succession, which are in turn abundant in our dataset. In any event, the aforementioned support, rather than negate, our findings on the lack of diversity in the composition of the college. As such, our work must be read as playful and creative, a ‘reliable, not bulletproof’Footnote 64 exercise of academic transgression, that allows us to bring to the fore reflections about the personal nature of international legal practice.

The reason for the choice of network analysis as a method for this project was its potential for another angle from which to map the invisible college of international lawyers, thereby demonstrating the inner mechanics of the profession. Conveying the sheer complexity of the relationships between the individual lawyers involved, the nature of their professional involvement, and each individual’s professional trajectories poses a seemingly impossible challenge. Narrating the ‘lineage’ of international lawyers by tracing the relationships within a segment of the group would not only consume the majority of this article but would do nothing to render visible this invisible college as is the article’s main aspiration. Narration did not do the dataset justice – since this study comprises over 175 lawyers and their respective relationships, apprehended from careful examination of the 58 obituariesFootnote 65 depicting only one snippet from this complex web would deprive readers from observing these connections for themselves. Doubtless there are revelations within the dataset which, while fascinating for some, we have had to gloss over. As detailed later, networks are appropriate tools here because they perfectly capture the fluidity of the profession as described by Schachter.Footnote 66 They also reveal the degrees of interconnectedness between members of the profession and organize the picture accordingly, reinforcing an understanding of the college as a highly exclusive group whose members share common characteristics.

This having been said, it is important to add a final caveat regarding our methodology. Specifically, our use of methods normally adopted by purely empirical research should not be seen as implying a belief in the possibility of reducing the topic at issue to its quantitative components. Rather, we acknowledge that empirical methods can sometimes import a mystique of scientism and capable of persuading us to overlook presumptions and biases through displays of numbers, graphs, facts, and figures.Footnote 67 We acknowledge these dangers, and submit that our contribution should be read as a creative and provocative attempt, carried out with the aid of empirical tools, to confront international lawyers with the personal nature of their discipline, and the interconnectedness of its members, rather than the final word on the make-up of the ‘invisible college’.

2.2 Social network analysis

SNA ‘comprises a broad approach to sociological analysis and a set of methodological techniques that aim to describe and explore the patterns apparent in the social relationships that individuals and groups form with each other’.Footnote 68 At the simplest possible level it can be defined as a methodology for the study of relations between specific actors (e.g., individuals) or institutions. SNA is based on network theory, which may be defined as the study of graphs as the representation of relationships (generally, as in our case, dyadic) between discrete objects.

The use of SNA in the social sciences has a long history. Indeed, its potential for highlighting the prominence of certain actors, as well as – and most importantly – latent patterns in the relationships between them, has made it a popular tool for the study of a broad variety of social groups. The use of SNA in law, though, has been more specific. In a first phase, of prolonged success, it has been used for the study of case law. Footnote 69 However, more recently, different studies have employed SNA to other ends, and specifically to shed light on the social dimension of prominent, but rather secretive, groups of actors having significant influence on certain regimes. Examples may be found in writings of Sergio Puig, who has employed this methodology to uncover the connections between arbitrators in ICSID cases gathering data on arbitral appointments, Footnote 70 as well as those of Malcolm Langford and Daniel Behn, who have expanded Puig’s analysis to investigate double-hatting in international investment arbitration and draw normative conclusions on the implications of the ‘revolving door’ phenomenon. Footnote 71

This work differs significantly from the two mentioned above. On the one hand, it explores a much lower number of connections within a smaller pool of individuals. On the other hand, we eschew reliance on official records and sources in favour of material more likely to yield relevant information on the informal connections between the subjects of our investigation. We are less concerned with comprehensiveness in the depiction of the profession and more with unveiling what more formal and structured records cannot. These connections include mentorships, friendships, successions in international institutions and universities, and family ties. The mapping of ‘invisible colleges’ through the combined use of SNA and informal sources is not unprecedented. On the contrary, similar methodologies have been employed successfully in other areas, including by the sociologist who crafted the term to describe networks of scientists, Diana Crane.Footnote 72

2.3 Making the most of the network metaphor

The data from the British Yearbook obituaries was first organized in a set of two spreadsheets. The first collects the data relating to the ‘nodes’ of the network, that is to say, international lawyers. Accordingly, we collect their names and relevant characteristics – professional positions they occupied, where they were educated, their affiliations with professional bodies or academic journals – organizing them in four columns. The first column lists the names of international lawyers, including those whose obituaries were written as well as those of the author(s) of each obituary and the names of people cited in it. An example would be Sir Derek Bowett’s obituary: it was written by James Crawford and cited Sir Ian Brownlie as his opponent in many ICJ cases. All three, deceased jurist, obituary author, and relations mentioned in the obituary (hence living jurists’ presence in the list), were logged in the ‘Nodes’ spreadsheet. The second column lists the professional roles occupied by the person mentioned. Again for Sir Derek Bowett his roles were of ICJ counsel, Whewell Chair of International Law at Cambridge, barrister, UN Legal Adviser, ILC member, and Academic.Footnote 73 A third column lists their year of death (where applicable), whereas the final one lists their membership of organizations if mentioned in their obituary – Derek Bowett was a member of the editorial board of the British Yearbook of International Law and of the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL), and a Fellow of Queens’ College, Cambridge.

While these data already provide us with a vast amount of information, SNA allows us to map the connections between international lawyers and to see this information in context. What is more, it is possible to go one step further, by taking advantage of the unique data structure on which SNA is based. Specifically, we go beyond focusing on the ‘nodes’ only, and we do so by storing relevant information on, and relating to, the ‘edges’ of the network. Specifically, a second spreadsheet (‘Edges’) collects the connections between different individuals. However, instead of just containing a long list of binary connections, it also holds elements relating to the type of connection between the individuals at issue. This is accomplished by a data structure built around three columns: the first one, entitled ‘Source’, lists the person whose obituary it was, thus where the information about a certain relationship came from. The second column, entitled ‘Target’, lists the person who either wrote the obituary or whose name was mentioned therein, and the third and final column, entitled ‘Relationship’, lists the type of relationship between the person in the first column and the person in the second. Footnote 74 We often had to list the same two people twice, if they had more than one ‘Relationship’ – for instance, the relationship between Lassa Oppenheim, in the first column ‘Source’, is listed next to A. Pearce-Higgins as his ‘Target’ twice: their ‘Relationships’ are both of ‘LSE Successor’ as well as ‘Whewell Chair Successor’. Other ‘Personal Connections’ of Oppenheim include Ronald Roxburgh, under ‘Mentor’, and many others.

2.4 Processing the data

In order to carry out or network analysis and create our visualizations, we used three software packages: Gephi, Footnote 75 NodeXL, Footnote 76 and Cytoscape. Footnote 77 The first is a popular choice among social scientists and digital humanities scholars, by virtue of its open source licensing and its rather powerful statistical and rendering engines. Footnote 78 The second is proprietary software which has been developed as an extension of the common spreadsheet software Microsoft Excel. Though not as powerful as Gephi in the rendering department, it can rely on the more advanced filtering features included in Microsoft Excel, which proved helpful for our analysis. Footnote 79 Finally, the third is generally used in bioinformatics research for the purposes of visualizing molecular interaction. Accordingly, it retains features that do not find much use in mainstream network analysis, but which remain exceptionally useful for our research, such as the ability to display and render parallel edges. This, too, proved beneficial for our approach, allowing us to make sense of the multi-layered relationships linking international lawyers to each other.

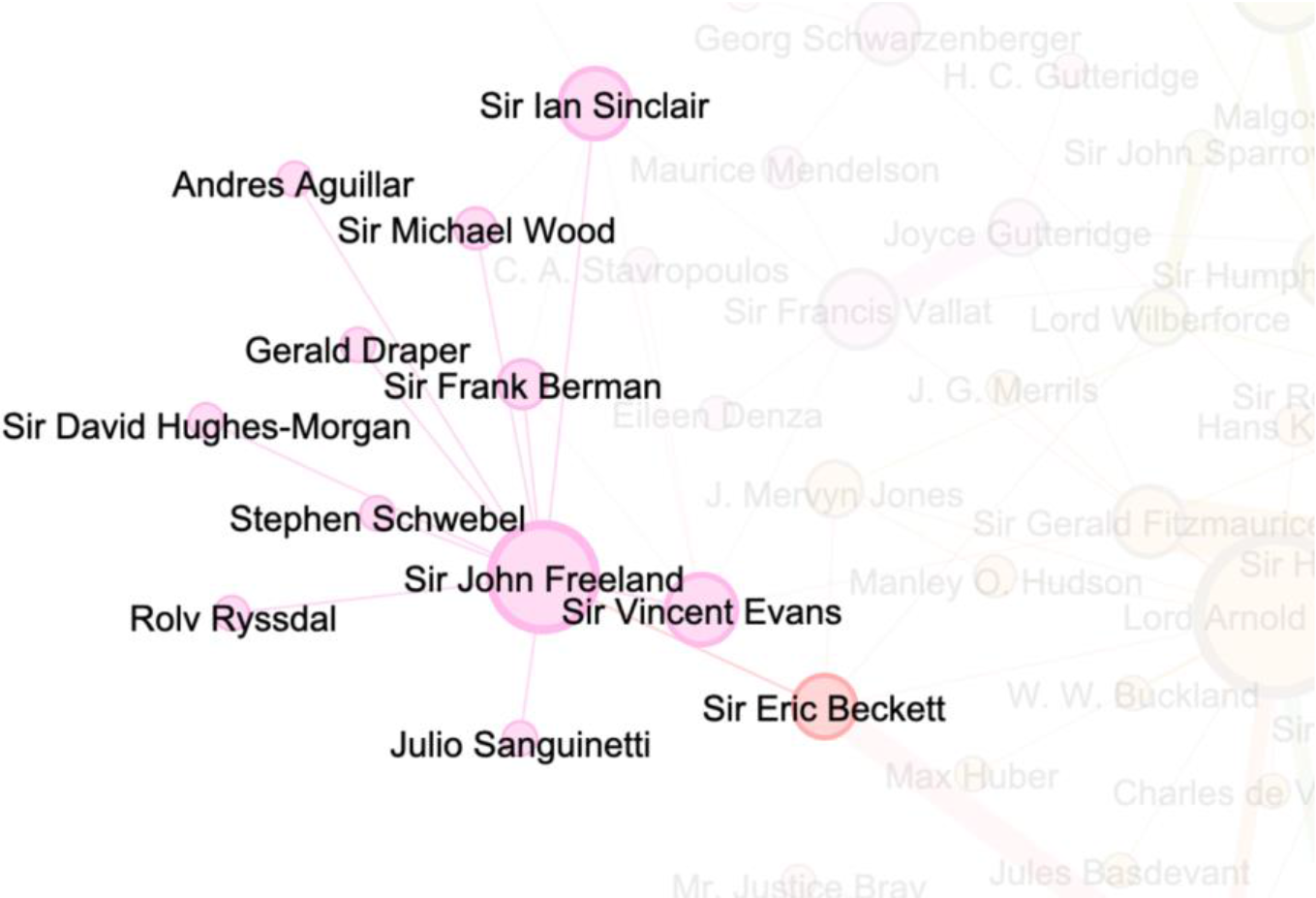

The software draws non-directional connections between the people listed in the ‘Nodes’ spreadsheet following the data structure in the ‘Edges’ spreadsheet. Taking, for example, the node corresponding to ‘Sir John Freeland’ (see Figure 2, below), we can find information as to its 11 edges (or connections) leading to 11 nodes – though, as explained, the number of connected nodes could be lower than the number of edges, which may describe different types of connections. The connected nodes (see Figure 3, below) are: Sir Frank Berman and Sir Michael Wood (Obituary writers), Sir Ian Sinclair (whom he preceded at the FCO), Sir Eric Beckett (his mentor at the FCO), Stephen Schwebel (co-worker at the United Nations), Gerald Draper and Sir David Hughes-Morgan (with whom he worked in the drafting of the 1977 Geneva Conventions), Julio Sanguinetti and Adres Aguillar (with whom he worked in the Letelier-Moffitt affair), Sir Vincent Evans (his European Court of Human Rights (hereafter ECtHR) predecessor), and Rolv Ryssdal (with whom he served as a judge at the ECtHR). Figure 4, above, represents Sir John Freeland’s network, resulting from the juxtaposition of the data collected as per Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 1. The full network.Footnote 80

Figure 2. Sir John Freeland nodes spreadsheet.

Figure 3. Sir John Freeland edges spreadsheet.

Figure 4. Sir John Freeland’s ‘ego network’.

3. Results

3.1 The full picture

The full network can be seen in Figure 1, above. Much can already be grasped from looking at the graph as a whole, without focusing on any specific names or relationships. The complexity of relationships and the interconnectedness of the community stand out, with numerous edges uniting the different nodes. This bolsters the claim that the community of influential international lawyers part of the ‘invisible college’ is very close-knitted.

Secondly, we can observe that there are certain central figures in the community of British international lawyers – people who are very connected and thus whose influence is perhaps particularly pervasive within the group. The algorithm automatically positions the nodes representing those individuals towards the centre of the graph and creates clusters of other relevant people around them.

As explained above, centrality in the graph is a function of centrality in mathematical – and, specifically, network – terms. Greater interconnectedness means greater centrality, so that ‘important’ figures gradually shift towards the centre of the graph. We also deployed a simple degree centrality algorithm, which shows the number of connections (incoming and outgoing) of specific nodes. Accordingly, the largest in the graph are the most ‘connected’ – because they are the ones whose obituaries were richest with citations of relationships to others, and/or who were continuously cited in other obituaries. A good example is Lord McNair. He was the mentor of many international lawyers from Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, to Sir Robert Jennings, to Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice, and was succeeded by Sir Humphrey Waldock at the European Court of Human Rights (hearafter ECtHR or European Court).

Thirdly, the software automatically organizes clusters according to profession in different areas of the graph, giving their members’ nodes different colours according to their modularity class, which parallels the similarity in their career paths. FCO members are quite distinctively at the top right corner of the graph in teal colour, with predecessors, successors, and lawyers who were their contemporaries organized around them. Another area densely populated and bunched together is that of academics/ICJ counsel/ICJ judges, in the central area (teal and dark blue). Lord Arnold McNair and Hersch Lauterpacht, for instance, occupy the centre of that area due to their great connectedness. Sir Derek Bowett, Sir Ian Brownlie, and James Crawford are also in that group. The bottom and bottom-right side of the graph is populated mainly by those involved in the setting up and functioning of the League of Nations. It is the only area of the graph that is mostly non-British; European figures such as Edouard Rolin-Jaequemyns are at its edges and important British and American figures of the time such as Lord Finlay or Elihu Root closer to the centre of the network.

A fourth and final interesting finding is whom the graph shows as outliers – those whose obituaries show no connections to the rest of the international lawyers in the main graph. There we have those whose obituaries appear in very early editions of the Yearbook, which did not contain an author, and which are thus left floating in the bottom right hand-side of the figure. The same is true of members of the editorial board or academics that dealt with private rather than public international law, and indeed the only Asian members in the dataset, Sakuye Takahashi and Inazo Nitobé. Footnote 81 Takahashi was an important Japanese international lawyer Footnote 82 who collected and translated Japanese materials into English, and his obituary writer was a Japanese intellectual and later important figure in the League of Nations. One may infer their lack of connectedness with other members of the profession in the main graph as lessening their prominence within the community. Again, it must be stressed that the community described here is the one resulting from the analysis of the Yearbook’s obituaries, with no prejudice to other possible communities that might be reconstructed through different means and sources. Within this community, other individuals may be very well connected, but have lesser prominence due to their connectedness to peripheral, rather than central members – the latter, thus, matter more. A good example is that of Gillian White, who, despite a large number of connections, in our dataset mostly appears as liaising with other women, and not many members who mixed (or who could mix) academia with practice.

3.2 Professional lineages – Jennings and others as example

Finally, and perhaps primarily, these obituaries give us a unique glimpse into the personal lives of international lawyers, especially insofar as they tell us about what their personal relationships and liaisons were. These connections are not obvious for those studying international law at the periphery, to whom mainstream scholarship, judgments, or ILC documents are the available windows into international law. Much in the way Anthea Roberts’ book Is International Law International? Footnote 83 made the familiar strange to those at the global ‘centre’ – i.e., those located in the West – explaining that different places learn international law from different sources and in different ways, this dataset reminds us that the invisible college is homogenous and self-perpetuating. Although looking at the list of attendants of an international conference, or the composition of the ILC or the ICJ can give us clues about connections between international lawyers, obituaries provide us a richer, personal and first-hand account of the close-knit nature of the profession, revealing professional and even blood-related ‘lineages’ of international lawyers, allowing us to trace how interconnected the ‘college’ can be in a personal register. Footnote 84

Stories of personal relationships between members of the profession abound in these materials. In some instances, international law is the family business. Lord Phillimore, for instance, the UK representative in the Advisory Committee of Jurists which drafted the PCIJ Statute, was the son of a prominent judge at the Admiralty Court in the UK which, at that time, was responsible for the majority of the cases with international law elements. Footnote 85 The UK considered nominating Phillimore for the PCIJ, but Lord Finlay prevailed. Similarly, Baron Édouard Rolin-Jaequemyns, described by Jenks as being ‘born in the purple’ due to his international law pedigree, was the son of Gustave Rolin-Jaequemyns. His father created the RGDIP and the IDI (his obituary reveals that he was present, as a child, at the founding meeting of the IDI in Ghent), Footnote 86 and he followed his father as an editor of the former and member of the latter. Other examples of family lineages outside the dataset famously include the late Sir Elihu Lauterpacht, son of Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, Footnote 87 Pierre-Marie Dupuy, Professor at Pantheón-Assas and son of Rene-Jean Dupuy, one of Cassese’s ‘Five Masters’ Footnote 88 of international law, Footnote 89 and Jules Basdevant, father of the first female ad hoc judge before the International Court of Justice, Suzanne Basdevant-Bastid. Footnote 90 Suzanne Basdevant-Bastid’s daughter, Professor Genevieve Burdeau-Bastid, is an international lawyer and former Secretary-General of the Hague Academy of International Law.

Added to these blood ties are professional ties, formed around prominent scholars or practitioners. A holistic appraisal of these connections paints an intricate but small community, with numerous links and cross-links. To reinforce the point, the following figure focuses in on certain prominent individuals.

See above, Figure 5, Oppenheim’s ego network: Oppenheim’s obituary was published in the first edition of the Yearbook in 1920, written by Edward Arthur Whittuck, a Liberal philanthropist Footnote 91 who worked in university administration at the London School of Economics (LSE) and was keen on promoting the study of the international law in the UK. He was one of the people responsible for bringing Oppenheim to the country and guaranteeing his first position there – a chair at the LSE. Footnote 92 Thereafter, Oppenheim was personally invited by John Westlake to succeed him as the fourth Whewell Chair of International Law at the University Cambridge. During his tenure, he wrote prolifically on matters of international law and worked tirelessly for its dissemination; his seminal International Law Footnote 93 manual was a game-changer in terms of textbooks in the discipline. Footnote 94 The book’s clarity and organization warranted the title of ‘the outstanding and most frequently employed systematic treatise on the subject in English-speaking countries’. Footnote 95 It was useful for both practitioners and students. Footnote 96

Figure 5. Oppenheim’s ego network.

Oppenheim’s LSE position was then occupied by Alexander Pearce Higgins, who later went on to follow him as the fifth Whewell Chair in Cambridge.

The study of international law was popularized, fostered and bolstered in the UK by those such as Oppenheim, leading to an increase in the number of members of the profession and subsequent thickening of the ties between them. A good illustration of the phenomenon are the ties between Lord Arnold McNair, Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice, Sir Humphrey Waldock, Sir Robert Jennings, Dame Rosalyn Higgins, Sir Derek Bowett, Sir Ian Brownlie, James Crawford, Vaughan Lowe, and Sir Christopher Greenwood. These individuals held or hold prestigious judgeships and teaching positions in the UK, and obituaries narrate how these positions change hands, often between mentor and mentee, and how close-knit these personal and professional relationships can be.

These individuals’ careers and personal lives are deeply intertwined, as demonstrated in Figure 6, Robert Jennings’s ego network, above. Lord Arnold McNair was educated in Cambridge, and subsequently taught international law at the London School of Economics; during his time at the LSE he updated Oppenheim’s International Law 4th edition. After publishing his famous Law of Treaties, he replaced Pearce-Higgins Footnote 97 as the Whewell Chair of International Law in Cambridge, a post which he held for two years before taking up administrative duties at Liverpool. Following Liverpool, McNair was elected as the first UK ICJ judge, Footnote 98 moving on to become later the first UK judge and first President of the ECtHR. McNair became very close to Hersch Lauterpacht, and their relationship was a mix of friendship and professional mentorship. Footnote 99 According to Jennings, ‘[i]t is quite right to couple a recollection of Hersch Lauterpacht with Arnold McNair’, Footnote 100 as ‘[t]hey became very close friends … until Lauterpacht’s premature death’, and ‘[Lauterpacht] would have never failed to do anything that Arnold McNair thought important for him to do’. Footnote 101 They first became friends during the difficult period after Lauterpacht moved from Austria to the UK, Footnote 102 and since then Lauterpacht’s career mirrored that of McNair – he succeeded McNair at the LSE, in the Whewell Chair position, and finally at the ICJ, having even moved in with his wife and son to McNair’s former home in Cambridge. Footnote 103 Lauterpacht’s successor at the ICJ was another of McNair’s Cambridge pupils, Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice. Fitzmaurice held McNair in high regard, Footnote 104 and was also close to Lauterpacht. It was Fitzmaurice, in fact, who wrote extensively on Lauterpacht’s attitude towards the judicial function in pieces also published in the British Yearbook. Footnote 105 Fitzmaurice, unlike McNair and Lauterpacht, became a government adviser to the Foreign Office instead of becoming an academic. During Lauterpacht’s and Fitzmaurice’s time at the ICJ, McNair was a judge at the ECtHR, where he was appointed the Court’s first president. Upon McNair leaving the ECtHR, he was replaced by Sir Humphrey Waldock. Although Waldock’s direct relationship with McNair cannot be distilled directly from the Yearbook’s obituaries, it can be established that they were members of the same distinguished circle: Waldock held the prestigious Chichele Chair of International Law in Oxford before ascending to the European Court, and his obituary was written by Jennings, McNair’s pupil. The absence of connection between these two personalities shows that, although uniquely rich with personal information, obituaries are not fool-proof and can be complemented by other biographical sources.

Figure 6. Robert Jennings’s ego network.

This picture of successions and relations of friendship and mentorship intensifies: Fitzmaurice and Waldock switch seats – Waldock succeeds Fitzmaurice at the ICJ, and Fitzmaurice replaces Waldock as the UK judge at the ECtHR. Footnote 106 All the while, Sir Robert Jennings takes over as the Whewell Chair at Cambridge, which he held for an impressive 21 years. As Jennings states in his heartfelt homage to Lauterpacht, he drew great inspiration from his two friends, mentors, and Whewell predecessors, McNair and Lauterpacht; he then followed his two mentors’ career paths ‘to the t’. First a lecturer at the LSE following Lauterpacht while also holding a fellowship at Cambridge, Jennings becomes somewhat unexpectedly Footnote 107 Lauterpacht’s Whewell Chair successor. After a long career in academia where he published extensively and on occasion practiced on matters of international law, Jennings is then nominated to the ICJ following Waldock’s death, leading a long mandate and presidency at the Court until 1995, when he retired.

Jennings’ retirement from the ICJ in turn led to the appointment of another pupil who led a similar life to the Court – the first female ICJ Judge, Dame Rosalyn Higgins – this next set of relationships is illustrated in Figure 7: Sir Derek Bowett’s ego network, above. Higgins developed a close relationship with Jennings during her time as a student at Cambridge. Footnote 108 She practiced at the Bar in international law cases and pleaded before the ICJ following her appointment to the LSE as international law chair, following Jennings. She also maintained very strong personal and intellectual ties to Myres S. McDougal at Yale. Footnote 109

Figure 7. Sir Derek Bowett’s ego network.

Jennings’ Whewell successor was however not Higgins, but another illustrious international lawyer with many similar connections, Sir Derek Bowett. Bowett was encouraged by Sir Hersch Lauterpacht to take up a career in international law during his undergraduate degree at Cambridge, leading him to pursue the then LL.B. in international law, for which he received the prestigious Whewell Scholarship in International Law. He was both academic and practitioner, and his practice grew as international law developed into a more complex and institutionalized system. Footnote 110 His career was paralleled by Ian Brownlie’s – they wrote and published seminal PhD theses reaching opposing conclusions on the law governing the use of force, often plead against each other at the ICJ and held the equally prestigious international law chairs in the rival institutions of Oxford and Cambridge. Footnote 111 While Bowett and Brownlie were active as counsel for the Court, other now-prominent ICJ figures began their own careers in practice, notably Sir Christopher Greenwood, Vaughan Lowe, and James Crawford. Lowe followed Brownlie as Chichele Chair, and appeared extensively before the ICJ. Greenwood practiced and taught at Cambridge and then LSE, being one of the mentees of Sir Elihu Lauterpacht during his Cambridge LL.B. Footnote 112 In turn, Crawford, who has had one of the most extensive international law practices in history, Footnote 113 was Brownlie’s supervisee in Oxford, and now, leaving the Whewell Chair after 21 years, also sits at the ICJ as of 2014 as the Australian judge.

This is a glimpse into the lives of international lawyers and is by no means exhaustive. Yet it provides a sense of the relationship between appointees for prominent teaching positions, legal advisers, and judgeships, as evidence of the ‘professional family trees’ of international lawyers. They are much better illustrated by the networks in the Figures above.

3.3 Characteristics – diversity

Exploring the network also allows us to test hypotheses concerning diversity within the profession. While many of these conclusions can be guessed, especially by those who are at the centre of the community, the dataset turns these guesses into visible pictures for the first time. Under the columns ‘profession’ and ‘organization’, we logged the characteristics of the members of the profession who had their lives recounted, who authored obituaries, or who was mentioned therein. This allows us to use these attributes as filters to further clarify the makeup of the community.

Education serves as a paradigmatic example. By filtering the network using the term ‘Cambridge’, ‘Oxford’, or using additional operators to show results matching both ‘Oxford and ‘Cambridge’, we can see that almost all nodes continue to appear in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Filtered by Oxbridge.

This tells us that as far as education is concerned, the members of the profession whose lives were sufficiently important to be recounted in the Yearbook, and thus potentially had a high degree of influence within the community, are not at all diverse. Footnote 114 The second filter used here is that of ‘male’ and ‘female’. The most stunning characteristic is that out of 64 obituaries, only one of them was dedicated to a woman until the publication of Gillian White’s obituary by Joyce Gutteridge in 2017. Although the male-dominated makeup of the community of international law professionals has been commented upon since the 1990s, Footnote 115 it is still shocking that, until 2017, those whose death is considered worthy of recounting are still so predominantly male. The implications of the lack of gender diversity in the profession is increasingly explored by feminist scholars. Footnote 116

Francis Vallat, whose own obituary mentions his dedication to hiring women in the Foreign Office, Footnote 117 is the author of Joyce Gutteridge’s Yearbook obituary. She was educated in Oxford and the daughter of Cambridge professor of comparative law, G. H. Gutteridge. Mentored by Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice, with whom she came into contact at the legal department during the war years, she began ‘her pioneer work as a woman lawyer’. She was the first woman to be appointed Assistant Legal Adviser at the Foreign Office in 1950, and at the time of her retirement, in 1966, she was ‘the most senior woman member of the Diplomatic Service’ in the UK. Gutteridge experienced difficulties being a woman in ‘a man’s world’: had she ‘been a man’, Footnote 118 Vallat says, she would have been awarded the more prestigious title of CMG rather than CBE for her work at the Foreign Office.

One more woman international lawyer graced the pages of the Yearbook in an In memoriam in its latest issue: Professor Gillian White. Having studied at King’s College London (LL.B.) and attained a doctorate in international law at the University of London, White then became a research assistant to Sir Elihu Lauterpacht in Cambridge, as well as a Fellow at, now, Murray Edwards College. She then transitioned into a lectureship at Manchester, where she stayed for the remainder of her career. While at Manchester, she became the first female Professor in Law in mainland Britain. She published a book on the use of experts before international courts and tribunals, but her main focus was on international economic law, in which she was one of the pioneers. She maintained a longstanding friendship with Joyce Gutteridge, who she often visited in Cambridge.

Two women have contributed by writing obituaries – Rosalyn Higgins, writing about Sir Robert Jennings, and Felice Morgenstern, writing alongside two other international lawyers about Sir Clarence Wilfred Jenks. In Sir Francis Vallat’s obituary written by Maurice Mendelson, two women are mentioned as having their careers duly fostered while at the FCO by Vallat, Miss Joyce Gutteridge and Eileen Denza. In Sir Derek Bowett’s obituary, Cherry Hopkins is mentioned. Gillian White’s obituary mentions, as well as Joyce Gutteridge, Chichele Professor Catherine Redgwell, who was her research assistant,Footnote 119 and Professors Hilary Charlesworth and Christine Chinkin whose book The Boundaries of International Law: A Feminist Analysis was published under the auspices of the Melland Schill Studies in International Law organized by White.Footnote 120 Sir Robert Jennings’ obituary mentions Malgosia Fitzmaurice, who edited a book in his honour alongside Vaughan Lowe.Footnote 121 The remaining women who are at all mentioned in obituaries are widows, ex-wives, and daughters whose husbands and fathers were eminent members of the profession.

In order to verify the dedoublement fonctionnel of international legal professionals, the network can be filtered by professional role, showing the commonalities in career paths of members. If we apply the filter ‘ICJ Judge AND ILC member’, five records out of 180 remain. Footnote 122 If we apply the filter ‘FCO adviser AND barrister’, 15 records out of 180 remain. Footnote 123 If we apply the filter ‘academic AND barrister’, 30 records out of 180 remain. Footnote 124

Additional information is unearthed by filtering the nodes according to nationality. To be sure, the British Yearbook is obviously British. Yet, it is possible to observe some variation in the nationalities of the international lawyers whose obituaries are published therein. Footnote 125 International lawyers not born in Britain but who made their careers therein, such as the towering figures of Lauterpacht Footnote 126 and Oppenheim, Footnote 127 have been given space in the Yearbook, as have a few prominent non-British judges of the World Court Footnote 128 and members of the Institut de Droit International, such as Édouard Rolin-Jaequemyns, Footnote 129 Elihu Root, Footnote 130 and Manley O. Hudson. Footnote 131 Out of these 14 non-British international lawyers, however, only four are non-European, Footnote 132 and out of these four, two are from the United States. We also observed greater openness to non-British subjects in the earlier editions of the Yearbook. Footnote 133 This is unsurprising, and confirms longstanding claims for more diversity: those who are sufficiently memorable to have their deaths reported widely, and thus those whose lives are deemed to have truly influenced the international legal world, are located, first and foremost, in Europe and North America.

Although this glimpse into the lives of international lawyers is by no means exhaustive, it provides a sense of the relationships between appointees for prominent teaching positions, legal adviser roles, and judgeships, as evidence of the professional (and sometimes literal) ‘family trees’ of international lawyers.

4. Conclusions

Using empirical methods, we playfully illuminate an obscure concept that albeit widely utilised is still poorly understood, that of the ‘invisible college of international lawyers’. We were able to produce a graphic representation of a section of the profession containing many insights into the community of international lawyers. Reliance on the obituaries published in the British Yearbook of International Law allowed us to build a dataset that is, despite the abovementioned limitations, both representative of the discipline throughout almost an entire century and rich with evidence on the professional and personal connections between international lawyers, as well as of information about the roles they occupied and educational background. Our network does not purport to be complete, but it sheds light on often invisible aspects of international lawyers’ lives that may seem frivolous or obvious to ‘members of the club’, but that are invisible from the periphery. Perhaps the greatest downside of using obituaries is their (obvious) impossibility to reflect the most current professional trends. This reinforces the need for our study to be complemented by quantitative and qualitative works that use other data, and surveying substantive literature on the international legal profession. The entry of large law firms into international legal practice, for example, has not been captured here but is something to be kept in mind.Footnote 134

Social network analysis allowed us to map the otherwise anecdotal accounts of an ‘invisible college of international lawyers’, providing us with novel and robust evidence that (i) that international lawyers constantly transition between professional roles, and (ii) that they are a small and tight-knit community (iii) composed of white men from the developed world. We accept the persuasive proposition that ‘(i)nternational law is, if not in whole at least in large part, what international lawyers do and how they think’.Footnote 135 We also acknowledge that ‘it would be myopic to minimize the influence of national [gender, class, educational background] positions on the views taken by the great majority of international lawyers’.Footnote 136 Thus, we must also acknowledge the power of evidence-based approaches for the proper appreciation of the legitimate critiques that call for increased diversity in the profession. Although our approach here privileged the use the networks to illustrate the complexity of career paths and connections between members, this does not mean that our data cannot be used by others to extrapolate on our conclusions. In fact, we hope that it will start a conversation and stimulate similarly disruptive and creative contributions that either use our network, expand upon it, or attempt to rebut our conclusions.