Introduction

Forty years have passed since Lord Diplock's seminal judgment in United City Merchants v Royal Bank of Canada (The American Accord) Footnote 1 which established the fraud exception in transactions financed by documentary credit. Fraud is a significant risk in credit transactions; the system is reliant on documents which can be easily forged,Footnote 2 goods are frequently shipped in containersFootnote 3 between parties unknown to each other and separated by geographical, cultural and legal distance.Footnote 4 Consequently, it is almost inconceivable that fraud does not happen in these transactions, particularly given the volume of global trade the device supports.Footnote 5 And yet, the fraud exception has never been successfully invoked to prevent payment. This is attributed to both the narrow confines of the fraud exception, as constructed by Lord Diplock, and the fact that fraud must be proved within a short timeframe for the exception to operate. This non-use of the fraud exception should not be confused with an argument that fraud is rife in transactions financed by documentary credit. It may well be that, in practice, fraud is constrained in other ways, such as by the doctrine of strict complianceFootnote 6 or reputational forces that serve to reduce wrongdoing. However, an examination of the fraud rule is important – this is ostensibly the judicial response to wrongdoing by credit beneficiaries – and timely, given developments in credit law since the decision in United City Merchants.

The judgment has divided the legal community over the last four decades. On the one hand, subsequent case lawFootnote 7 and several academic commentatorsFootnote 8 have endorsed Lord Diplock's approach, while, on the other hand, the judgment has received stringent criticism from leading scholars, such as Roy GoodeFootnote 9 and Michael Bridge.Footnote 10 This paper joins the dissenters and argues that judicial, legislative and academic developments since Lord Diplock's judgment and Goode's critique justify a re-examination of the fraud exception and, in particular, a departure from United City Merchants.

To make this argument, this paper re-examines the facts and decision in United City Merchants in Part 1.Footnote 11 It demonstrates the importance that policy considerations – most notably, the efficiency of the credit mechanism – played in Lord Diplock's decision to confine the fraud exception within narrow parameters. This provides a useful foundation to consider two distinct, although often conflated, areas of debate which flow from Lord Diplock's analysis. First, the narrow parameters of the fraud exception have prompted much discussion about whether it should be widened to encompass a broader range of wrongdoing by the credit beneficiary. A comparative approach, drawing on the American response to fraud in credit transactions, is used in Part 2 to reflect on English insistence that a narrow fraud rule is justified by commercial need. It argues that the broader exception employed in the US has not resulted in the ‘thrombosis’Footnote 12 so feared by English courts and, moreover, that recent American commentary endorses their current position. This provides scope for a modern court to reconsider the policies underpinning the rule, and consign United City Merchants to history.

The second area of debate focuses on the doctrine of strict compliance. This is because Lord Diplock failed to give due weight to this doctrine in his analysis of the credit mechanism. Indeed, he characterised the bank as being under a contractual obligation to make payment against documents which were known to be forged at the time of presentation.Footnote 13 This conflation was noted by GoodeFootnote 14 shortly after the judgment in United City Merchants and his analysis is necessarily central to any critique of Lord Diplock's approach. However, this paper argues that recent developments – including the UCP 600 and case law on null documents – further justify a departure from the analysis in United City Merchants. Accordingly, the paper concludes by outlining an approach more faithful to both the UCP 600 and the needs of modern commercial parties when documents are proven nullities or forgeries at the time of presentation.

1. United City Merchants v Royal Bank of CanadaFootnote 15

A transaction financed by documentary credit is, at its heart, a simple transaction for the sale of goods. This is complicated, however, by the international context in which the transaction occurs. The great distances separating parties means that in the majority of cases shipment and payment are not simultaneous.Footnote 16 Sequential contractual performance creates risks for both parties, as Thomas Hobbes argued in Leviathan:

for he that performeth first, has no assurance the other will perform after, because the bonds of words are too weak to bridle men's ambition, avarice, anger, and other passions, without the fear of some coercive power…Footnote 17

These risks are exacerbated in credit transactions when, as will often be the case, the parties are unknown to each other. From the seller's perspective, the risk associated with shipping the goods in advance is that it creates an incentive for the buyer to identify a trivial defect in the goods to withhold payment.Footnote 18 Conversely, the buyer will not want to pay in advance since he cannot ascertain the quality of the goods.Footnote 19 If cross-border transactions are going to succeed, therefore, parties must incorporate a mechanism to mitigate these risks and render performance as simultaneous as possible.

To illustrate how the documentary credit serves this purpose and to reacquaint readers with the principles underpinning the mechanism, it is convenient to begin with the facts of United City Merchants.Footnote 20 The case is a paradigmatic example of the circumstances in which we would expect a credit to be used; an English seller contracting to supply a fibre glass plant to Peruvian buyers. Cognisant of the risks inherent in the transaction, the parties financed their transaction by documentary credit and incorporated the Uniform Customs & Practice for Documentary Credits (UCP), a voluntary set of ‘best practice’ rules for credit transactions produced by the International Chamber of Commerce.Footnote 21 The UCP is adopted in almost all credit transactionsFootnote 22 and has become the ‘most successful set of private rules for trade ever developed’.Footnote 23

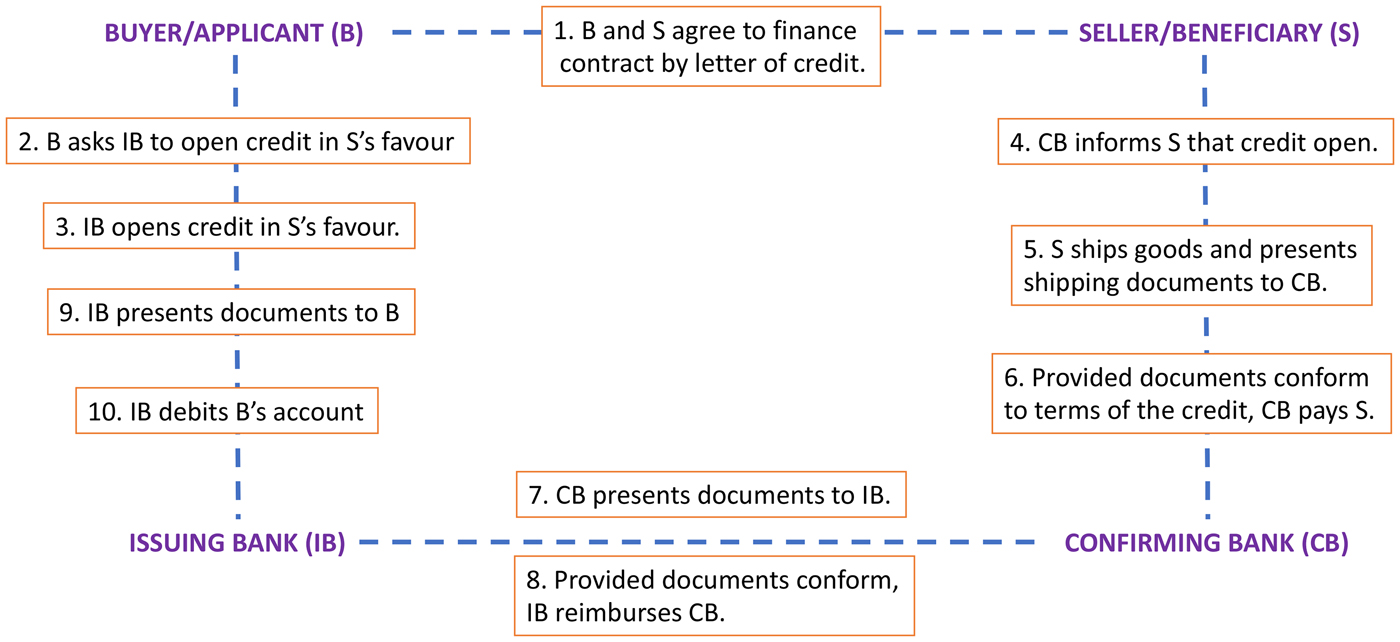

Put simply, the credit transforms the sale into one conducted through the medium of documents and introduces banks to the contractual network. This creates a channel through which payment is made to the seller and the documents are passed to the buyer. The resulting network of contracts, and the stages of the transaction, are illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1. The structure of a transaction financed by letter of credit

These contracts are subject to the twin principles of autonomy and strict compliance. The doctrine of autonomy requires each contract to be seen in isolation from all other contracts in the network, meaning that it is enforced by reference to its own terms. This renders the transaction less susceptible to judicial intervention, since neither the paying bank nor the credit applicant will be able to raise issues elsewhere in the credit network, most notably a breach of the underlying contract, to prevent payment under the instant contract.Footnote 24 In United City Merchants, Lord Diplock referred to autonomy in the following terms:

The whole commercial purpose for which the system of confirmed irrevocable documentary credits has been developed in international trade is to give to the seller an assured right to be paid before he parts with control of the goods that does not permit of any dispute with the buyer as to the performance of the contract of sale being used as a ground for non-payment or reduction or deferment of payment.Footnote 25

The second principle – the doctrine of strict compliance – dictates the standard against which presented documents are assessed. When the beneficiary presents documents – typically a clean bill of lading, insurance policy and a quality certificate issued by a third partyFootnote 26 – which strictly conform to what has been agreed in the underlying contract, payment will be made. The quality of the presentation is clearly vital in a sale conducted through the medium of documents. This was made plain by Viscount Cave in Equitable Trust Co of New York v Dawson Partners:

there is no room for documents which are almost the same, or which will do just as well. Business could not proceed securely on any other lines.Footnote 27

Simply, commercial parties must be able to trust that the documents are genuine and represent the goods in question. This is particularly critical given that the goods will either arrive much later than the documents or may never reach the intermediate buyer when the goods are sold afloat. Genuine documentation has a further significance in credit transactions, as noted by Lord Diplock,Footnote 28 because of the risk that the credit applicant may become insolvent before he has reimbursed the issuing bank. In a standard contract of sale, the risk of buyer insolvency falls on the seller, but in a documentary credit transaction this risk is transferred to the issuing bank. The bank is willing to accept this risk since it has prior knowledge of the applicant's creditworthiness and can price the credit commensurate to the level of risk the customer represents.Footnote 29 In addition, as the bank retains the shipping documents until it has been reimbursed by the applicant, the documents represent security and can be sold to a third party in the event of the applicant's insolvency.Footnote 30 That the insolvency risk is the major concern for the banks was underlined in the celebrated discussionFootnote 31 in Sanders v Maclean.Footnote 32 In that case, Bowen LJ stated that ‘the object of mercantile usages is to prevent the risk of insolvency, not of fraud’Footnote 33 and, moreover, that this foundation was critical to understanding ‘the law merchant’.Footnote 34 Accordingly, from the banks’ perspective, for the credit to effectively mitigate the risk of applicant insolvency, it is vital that the documents are what they appear to be.

Lord Diplock referred to ‘stipulated documents’Footnote 35 throughout his judgment and, at first, correctly characterised the paying bank's obligation in the following terms:

If, on their face, the documents presented to the confirming bank by the seller conform with the requirements of the credit as notified to him by the confirming bank, that bank is under a contractual obligation to the seller to honour the credit.Footnote 36

The reference to ‘on their face’ in this part of the analysis merits consideration. The bank's role is simply to examine the documents for compliance with the terms and conditions of the credit. Banks are not investigators and do not assume any liability for the genuineness or accuracy of the documents,Footnote 37 beyond the fact that they appear to be what the credit demands. Couching the bank's role in administrative terms ensures that payments are made swiftly and is said to reflect the fact that banks cannot be expected to be experts in all transaction they agree to finance.Footnote 38 Prompt payment is necessarily beneficial for the seller but it also enables the buyer to take actions in respect of the goods, including selling them afloat, as soon as he receives the documents. Critically, ahead of the analysis in Part 3, the ‘on their face’ approach to compliance contained in the UCP did not oblige the bank to pay if it actually knew that the documents were not what they appeared to be. It merely specified that the bank's examination was confined to the documents alone.Footnote 39

The network of contracts created by the credit redistributes many of the risks inherent in an international contract of sale. As Figure 1 above shows, instead of the buyer paying the seller directly, the seller receives payment from the confirming bank – a bank located in his own country – which is then reimbursed by the issuing bank. As noted above, this shifts the risk of buyer insolvency from the seller-beneficiary to the issuing bank.Footnote 40 In addition, conditioning payment on the presentation of complying documents protects both buyer and seller from the risk of their counterpart's opportunistic behaviour due to the sequential nature of contractual performance. From the buyer's perspective, the inclusion of a quality certificate issued by an independent party provides reassurance that the contract goods have been shipped,Footnote 41 while for the seller, strict compliance prevents the buyer withholding payment on the basis of a trivial defect in the goods.

To return to the facts of United City Merchants, the credit required that the vessel departed Felixstowe, England by 15 December 1976 and the seller-beneficiary presented documents appearing to show that this had taken place. In reality, however, the goods were shipped two days late and from a different port. A third-party loading broker had falsified the bill of lading to give the impression of compliance with the credit.Footnote 42 Before the documents were presented for examination, the shipping line had informed the buyer of the late shipment. The issuing bank had also been notified at this time.Footnote 43 When the confirming bank was made aware of this, it refused to pay due to the fraudulent nature of the documents. The beneficiary then brought an action for wrongful dishonour of the credit.

The question for the House of Lords was whether fraud perpetrated by a third party could be used to justify non-payment by the bank. Put another way, in what circumstances would the court recognise an exception to the autonomy of the credit and permit evidence extraneous to the goods to substantiate a fraud? In a unanimous judgment delivered by Lord Diplock, the Court answered the first question in the negative. Payment could only be legitimately refused:

where the seller, for the purpose of drawing on the credit, fraudulently presents to the confirming bank documents that contain, expressly or by implication, material representations of fact that to his knowledge are untrue.Footnote 44

The rule was explained as ‘a clear application of the maxim ex turpi causa non oritur actio or, if plain English is to be preferred, fraud unravels all’.Footnote 45 This directs the court to focus its attention on the beneficiary to determine whether he has engaged in any wrongdoing in relation to the documents. In such circumstances where, for example, the beneficiary had deliberately falsified the documents or presented documents without having shipped the contract goods, the court will accept evidence extraneous to the documents to substantiate the beneficiary's wrongdoing. This may involve direct evidence from a third party, documentary evidence relating to the underlying contract or a sample of the contractual goods.Footnote 46 However, in United City Merchants, the fraud was perpetrated by a third party without the beneficiary's knowledge meaning that the fraud exception could not operate.

There is no doubt that in constructing the fraud exception in this way, Lord Diplock was attempting to limit the scope of judicial intervention. To do otherwise, his Lordship argued, ‘would… undermine the whole system of financing international trade by means of documentary credits’.Footnote 47 In addition to the narrow parameters of the fraud exception, if it is to be employed to prevent payment reaching the beneficiary, evidence of fraud must gathered within the five banking days permitted for document examination. In addition to these time constraints, the standard of proof, as is common in allegations of fraud, is high. For several years, the courts struggled to explain exactly what was required in order to prove fraud. The case law, for example, contains references to proof of ‘established or obvious fraud’,Footnote 48 a ‘real prospect’Footnote 49 of establishing fraud and ‘a good arguable case that on the material available the only realistic inference’ is fraud.Footnote 50 However expressed, there is a crucial balance to ensure that the courts do not:

adopt so restrictive an approach to the evidence required as to prevent themselves from intervening. Were this to be the case, impressive and high-sounding phrases such as ‘fraud unravels all’ would become meaningless.Footnote 51

The standard of proof was most recently considered in Alternative Power Supply v Central Electricity Board. In that case, the Privy Council reviewed the authorities and concluded:

it must be clearly established at the interlocutory stage that the only realistic inference is (a) that the beneficiary could not honestly have believed in the validity of its demands under the letter of credit and (b) that the bank was aware of the fraud.Footnote 52

This usefully clarifies the position but does not mitigate the practical difficulty of amassing sufficient evidence within five banking days.Footnote 53 This must be borne in mind in any critique of the fraud rule. However, this paper focuses on the two specific, although often conflated, areas of debate flowing from Lord Diplock's judgment. First, his decision to limit judicial intervention to preserve the efficiency of the credit mechanism has prompted consideration of the proper bounds of the fraud rule. In Part 2, the policy justification of the English rule will be challenged in light of the broader exception codified in the American Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) and recent commentary suggesting that the American exception functions satisfactorily.

Secondly, the focus on wrongdoing by the beneficiary means that defects in the documents perpetrated by a third party will not trigger the fraud exception. Specifically, documents which are known to be forged at the time of presentation but which appear to conform did not, on Lord Diplock's analysis, justify non-payment by the bank. This undermined the doctrine of strict compliance. Recent developments in documentary credit law, most notably the UCP 600 and judicial decisions on null documents, strengthen this analysis and are used, in Part 3, to argue in favour of a new approach when documents are proven forgeries or nullities at presentation.

2. The narrow confines of the English fraud exception

The driving force behind the narrow parameters of the fraud exception was, as noted above, Lord Diplock's desire to maintain the efficiency of the credit mechanism. This argument had been well-rehearsed in earlier case law, as demonstrated by Donaldson LJ's discussion in The Bhoja Trader:

thrombosis will occur if, unless fraud is involved, the Courts intervene and thereby disturb the mercantile practice of treating rights thereunder as being the equivalent of cash in hand.Footnote 54

This is a laudable policy objective and, since the ICC has repeatedly maintained that fraud is best dealt with by national jurisdictions,Footnote 55 was an entirely legitimate path for the House of Lords to take. It is interesting, however, to reflect on the narrowness of the exception in light of the more expansive approach taken in the US. This comparison is triggered by Lord Diplock's comments in United City Merchants:

… [the fraud exception] is well established in the American cases of which the leading or ‘landmark’ case is Sztejn v J Henry Schroeder Banking Corp… This judgment of the New York Court of Appeals was referred to with approval by the English Court of Appeal in Edward Owen Engineering Ltd v Barclays Bank International Ltd…Footnote 56

In addition, Ackner LJ subsequently commented on the American approach in United Trading which speaks directly to English fears connected to a broader exception:

It is interesting to observe that in America, where concern to avoid irreparable damage to international commerce is hardly likely to be lacking, interlocutory relief appears to be more easily obtainable… There is no suggestion that this more liberal approach has resulted in… commercial dislocation…Footnote 57

In Sztejn the fraudulent seller had deliberately failed to ship any of the contract goods. This was analysed by Shientag J as fraud in the transactionFootnote 58 but because the documents appeared to conform, the fraud was also documentary in nature, consisting of material misrepresentations in the bill of lading.Footnote 59 This was subsequently codified in UCC, Art 5. Accordingly, unless the presentation was made by an innocent third party – a nominated bank or a person in the position of a holder in due courseFootnote 60 – the bank was entitled to reject:

when documents appear on their face to comply with the terms of the credit but a required document… is forged or fraudulent or there is fraud in the transaction.Footnote 61

This is broader than the English exception. It recognises forgery as a basis for intervention and does not require that the beneficiary was the author or aware of the defects. Applying this to United City Merchants, the bank would have been justified in rejecting the presentation; the bill of lading contained a false shipment date and the person seeking payment – the beneficiary – was not a protected party under the UCC. This was not the conclusion drawn by Lord Diplock. Instead, he argued that a beneficiary unaware of defects remained entitled to payment in America:

This is certainly not so under the Uniform Commercial Code as against a person who has taken a draft drawn under the credit in circumstances that would make him a holder in due course, and I see no reason why, and there is nothing in the Uniform Commercial Code to suggest that, a seller/beneficiary who is ignorant of the forgery should be in any worse position because he has not negotiated the draft before presentation.

But this, with respect, was incorrect. The UCC did not extend protection to the beneficiary in these circumstances and, moreover, to equate the beneficiary with the holder in due course is spurious. This is because, as Goode has argued, ‘the beneficiary under a credit is not like a holder in due course of a bill of exchange; he is only entitled to be paid if the documents are in order’.Footnote 62 Accordingly, a significant strand of Lord Diplock's analysis was dependent on a flawed reading of US law.

Article 5 was revised in 1995. This recodification was designed to narrow the fraud exception and clarify the criteria for the grant of an injunction.Footnote 63 As such, Art 5 now provides that unless payment is demanded by a protected party,Footnote 64 the bank can reject a presentation which:

appears on its face strictly to comply with the terms and conditions of the letter of credit, but a required document is forged or materially fraudulent, or honor of the presentation would facilitate a material fraud by the beneficiary on the issuer or applicant.Footnote 65

Whilst noting the express purpose of the 1995 revisions, it remains the case that the American exception is broader and more likely to be invoked than its English counterpart. The opening sentence of Art 5 confirms that the court has jurisdiction in cases where the fraud appears on the face of the documents. Despite the apparent similarity with the English approach, Art 5 is substantially broader because it does not require that the fraud be connected to the beneficiary.Footnote 66 Thus, where a document has been forged or is materially fraudulent, the court will focus on the character of the document rather than the identity of the wrongdoer.Footnote 67 This means that fraud by a third party unconnected to the beneficiary – as was the case in United City Merchants – remains actionable under the UCC since payment was not demanded by a protected party.Footnote 68

Article 5 then clearly departs from the English approach by recognising that fraud in the transaction also triggers the exception. This is evident in the phrase ‘honor of the presentation would facilitate a material fraud by the beneficiary on the issuer or applicant’. This permits the court to intervene in cases of fraudulent misrepresentation by the beneficiary which either induced the documentary credit itselfFootnote 69 or the underlying contract of sale.Footnote 70 Significantly, judicial intervention in these circumstances requires that the wrongdoing is authored by the beneficiary. Irrespective of this limitation, the recognition of non-documentary fraud establishes the breadth of the US position in comparison to its English equivalent.

In both jurisdictions, actionable fraud is characterised as material, but this standard has been defined differently. In line with the general trend of Art 5, the American courts have conceptualised material fraud more expansively than their English counterparts. Lord Diplock failed to define materiality in United City Merchants, although in rejecting two conceptionsFootnote 71 did provide some guidance as to what would not be material. In English law, materiality has since been related to the bank's obligation to pay so that if the shipping documents stated the truth the bank would not be bound to pay since the documents would fail the compliance test.Footnote 72 The American approach to materiality is more flexible, and therefore more generous,Footnote 73 to the party seeking to invoke the fraud exception. In particular, materiality is judged by reference to the underlying contract and to the impact of fraud on the purchaser.Footnote 74 This makes sense given that the American exception encompasses both documentary fraud and that related to the underlying contract. By way of illustration, a material fraud would have been committed where, in a contract for the sale of 1000 barrels of oil, the beneficiary presented apparently complying documentation but had only shipped five of the required barrels.Footnote 75 A shipment of 998 barrels would be regarded as an ‘insubstantial and immaterial’ breach of the underlying contract.Footnote 76 Clearly, these examples drawn from the Official Comment to the 1995 Revisions represent the very extremes of partial shipment. There was no further discussion at the time nor subsequently as to where the tipping point should lie; exactly when does short shipment become fraud?Footnote 77 Recently, Dolan has argued that materiality will not be easy to satisfy since the courts’ intention, in interpreting Art 5, is to narrow the fraud exception.Footnote 78 It is likely, therefore, that the courts will require a greater number of the barrels to be missing before short delivery is deemed fraudulent. It is also arguable that permitted tolerances in the UCP would influence the appropriate tipping point. In particular, Art 30b permits a tolerance of +/- 5% in quantity unless the credit explicitly stipulates the ‘number of packing units or individual items’.Footnote 79 This is not directly applicable to the above example since 1000 barrels are expressly stipulated. However, a court may well be influenced by the 5% threshold in the UCP so that short delivery would only be regarded as fraud when at least 50 barrels were missing. Irrespective of where the tipping point actually falls – and this will often necessitate a complex factual enquiry – the US conception of materiality gives the courts greater scope to intervene than in England.

Divergent responses to fraud in credit transactions stem from the ICC's repeated refusal to include fraud within the UCP. The comparative discussion undertaken is not a suggestion that the English courts should simply import the American exception. However, this evidence of a different approach to fraud allows us to reflect on Lord Diplock's steadfast insistence that a narrow exception was required to maintain the efficiency of the documentary credit, and to consider whether ‘thrombosis’Footnote 80 has occurred in the US. Indeed, both the traditional credit mechanism and standby credits – to which Art 5 also appliesFootnote 81 have remained popular in the US.Footnote 82 Moreover, recent commentary in the US suggests that the position with respect to fraud is settled; the courts faithfully apply the provisions of Art 5 and there is no clamour for reform.Footnote 83 More generally, there is sufficient litigation on credit issues to warrant an annual survey in The Business Lawyer.Footnote 84 Interestingly, the consequent delay in payment and potential for judicial intervention does not appear to have to have affected the credit market. This is fascinating in light of the English view that judicial intervention in credit transactions would destroy the very essence of a swift, autonomous payment mechanism.

The discussion in the conclusion, below, will reflect on what the comparative discussion means for the future of the English fraud rule. Specifically, it will be argued that the narrow parameters established by Lord Diplock can no longer be justified in the interests of commercial need and demand reconsideration. Attention now turns to the second difficulty following Lord Diplock's analysis; the fate of documents proven to be forged or null at the time of presentation.

3. The conflation of fraud and documentary compliance

Having determined that the fraud exception was not operative, Lord Diplock then proceeded to consider the impact of documents which appeared to be those demanded by the credit but were actually forged or null. This, as shall be seen in due course, had occupied significant time at the Court of Appeal. However, before the substantive aspects of Lord Diplock's judgment are considered, the concepts of forgery and nullity will be illustrated. The first, forgery, is a document which ‘tell[s] a lie about itself’,Footnote 85 such as the date or place of shipment or the apparent good order of the goods on loading.Footnote 86 Notwithstanding such lies, forged documents remain capable of serving their intended commercial purposes,Footnote 87 as a receipt or evidence of the contract of carriage. By contrast, a nullity is devoid of legal value.Footnote 88 This would be the case where clean shipping documents were presented in respect of a phantom shipmentFootnote 89 or signed by an individual without the authority to do so.Footnote 90 Certain forgeries, for example a bill of lading not issued by the purported issuer or a certificate of insurance tendered without a valid policyFootnote 91 may also render the document a nullity. Nullities are particularly problematic since they cannot be used to obtain delivery or provide other security over the goods.Footnote 92 This clearly impacts the ultimate purchaser of the goods but, more significantly, will also deprive the issuing bank of protection in the event of its customer's insolvency.

So, how should banks respond to presentations which contain forged or null documents? Lord Diplock first approached this issue by setting out the bank's contractual obligation, namely to pay against presentations which appeared to conform to the credit:

… as between confirming bank and issuing bank and as between issuing bank and the buyer the contractual duty of each bank under a confirmed irrevocable credit is to examine with reasonable care all documents presented in order to ascertain that they appear on their face to be in accordance with the terms and conditions of the credit, and, if they do so appear, to pay…Footnote 93

It was correct to characterise the bank's duty under the UCP to examine the documents with reasonable care as a contractual obligation.Footnote 94 This examination is confined to the documents themselves as is evident in the phrase ‘on their face’.Footnote 95 However, Lord Diplock then further characterised the bank's contractual obligation to pay as triggered by documents which appeared to conform. This was incorrect; the UCP characterised payment on the basis of apparent compliance as an entitlement, as distinct from a contractual duty.Footnote 96 To justify this, Lord Diplock cited Gian Singh v Banque de l'Indochine, a case in which the credit required a quality certificate to be signed by a ‘Balwant Singh, holder of Malaysian passport no. E.13276’.Footnote 97 It later transpired that the document was an ingenious forgery, although the paying bank had not been negligent in failing to detect this. The bank, faithful to its duty under the UCP, had carried out a ‘visual inspection of the actual documents’ and was not required ‘to investigate the genuineness of a signature which, on the face of it, purports to be the signature of the person named or described in the letter of credit’.Footnote 98 Accordingly, Gian Singh is authority for the proposition that the paying bank is entitled to reimbursement if, despite a reasonable examination,Footnote 99 defects in the documents were subsequently discovered.Footnote 100 This is entirely appropriate where defects come to light after the beneficiary has received payment. The judgment in United City Merchants, however, recommends the same approach to presentations which are known to contain a forgery at the time of presentation. This is apparent in Lord Diplock's later comments:

It would be strange from the commercial point of view, although not theoretically impossible in law, if the contractual duty owed by confirming and issuing banks to the buyer to honour the credit on presentation of apparently conforming documents despite the fact that they contain inaccuracies or even are forged, were not matched by a corresponding contractual liability of the confirming bank to the seller/beneficiary (in the absence, of course, of any fraud on his part) to pay the sum stipulated in the credit upon presentation of apparently conforming documents…Footnote 101

This goes too far. To characterise the bank as legally liable to the beneficiary for non-compliant presentations wholly overlooks the significance of conformity in a sale by documents. The suggestion that the contracts created by the credit should be identical – ‘matched by a corresponding contractual liability’ – also undermines the doctrine of autonomy. As noted earlier, autonomy demands that each contract is enforced on its own terms and treated as distinct from the other contracts within the network. This is not the same as requiring each contract to mirror the others in the network, as appears to be the thrust of Lord Diplock's argument here. The determination that forgery could not ground rejection of the documents was also reliant on Lord Diplock's reading of the UCC. He argued:

I would not wish to be taken as accepting that the premiss as to forged documents is correct, even where the fact that the document is forged deprives it of all legal effect and makes it a nullity, and so worthless to the confirming bank as security for its advances to the buyer. This is certainly not so under the Uniform Commercial Code as against a person who has taken a draft drawn under the credit in circumstances that would make him a holder in due course, and I see no reason why, and there is nothing in the Uniform Commercial Code to suggest that, a seller/beneficiary who is ignorant of the forgery should be in any worse position because he has not negotiated the draft before presentation.Footnote 102

We know from the earlier discussion, however, that this was incorrect; the UCC does not and did not equate the holder in due course with the innocent beneficiary. The former is entitled to payment when they are unaware of the forgery,Footnote 103 the latter is not. His Lordship declined to reach a conclusion on the nullity point since the issue did not arise directly.Footnote 104 This would subsequently come before the Court of Appeal in Montrod v Grundkotter.Footnote 105

Respectfully, therefore, Lord Diplock was incorrect to characterise the bank as obliged to pay against documents proven to contain defects at presentation. This was apparent at the time; a different analysis more faithful to the UCP had been adopted by the Court of AppealFootnote 106 and also prompted contemporaneous criticism from Roy Goode.Footnote 107 The Court of Appeal focused on documentary compliance and concluded, critically, that a forged document was to be regarded as non-complying even if the beneficiary was unaware of it:

If the signature on the bill of lading had been forged, a fact of which the sellers were ex hypothesi ignorant, but of which the bank was aware when the document was presented, I can see no valid basis upon which the bank would be entitled to take up the drafts and debit their customer… A banker cannot be compelled to honour a credit unless all the conditions precedent have been performed, and he ought not to be under an obligation to accept or pay against documents which he knows to be waste paper. To hold otherwise would be to deprive the banker of that security for his advances, which is a cardinal feature of the process of financing carried out by means of the credit.Footnote 108

As such, documentary compliance was considered wholly distinct from the wrongdoing of the beneficiary, the latter being dealt with under the fraud exception. This distinction, significantly, did not mean that the policy arguments employed by Lord Diplock had been ignored by the Court of Appeal:

… the fewer the cases in which a bank is entitled to hold up payment the better for the smooth running of international trade. But I do not think that the Courts have a duty to assist international trade to run smoothly if it is fraudulent … Banks trust beneficiaries to present honest documents; if beneficiaries go to others (as they have to) for the documents they present, it is important to all concerned that those documents should accord.Footnote 109

The differences in approach adopted by the appellate courts are fascinating. Significantly, it cannot be explained by differences in counsel nor the arguments employed before the respective courts.Footnote 110 Perhaps the only basis for explaining this difference is that it is an ‘uncharacteristic error of the late Lord Diplock’.Footnote 111 This analysis is all the more compelling in light of his Lordship's earlier comments in Gian Singh, in which he appears to argue that known forgery would justify rejection by the bank:

But if it did not conform, the customer does not need to rely on any negligence by the issuing or notifying bank in failing to detect the forgery, for independently of negligence, the issuing bank would be in breach of its contract with the customer if it paid the beneficiary on presentation of that document.Footnote 112

This, it is submitted, represents Lord Diplock analysing forgery as a matter of documentary compliance in which the knowledge of the beneficiary is irrelevant. This is wholly opposed to the position he adopted in United City Merchants and adds weight to the suggestion that his subsequent analysis was mistaken.

Goode's critique, which emerged shortly after United City Merchants, mirrored the logic of the Court of Appeal judgment. His main contention was that the House of Lords had overlooked two distinct aspects of the enquiry when documents are presented under a credit: pre-conditions that the beneficiary must satisfy to become entitled to payment and defences to payment.Footnote 113 In Goode's analysis, these operated sequentially with the initial focus on whether the beneficiary had done everything required by the contract to become entitled to payment, namely to present the documents stipulated by the credit.Footnote 114 Significantly, this obligation does not depend on the documents merely appearing to conform. Therefore, if there are known defects at the time of presentation, the bank would be entitled to reject the presentation irrespective of who was responsible for the defects and of whether the beneficiary was aware of it. Non-conforming documents cannot be rendered conforming simply by virtue of the beneficiary's ignorance of those defects.Footnote 115 This was the very myth that Lord Diplock's judgment appeared to be premised on. Importantly, this does not change the bank's duty of examination; the bank remains entitled to pay in circumstances where the documents appear to conform, but should not be so entitled where defects have been established at the time of presentation. If the bank opts to reject, the beneficiary may retender within the timeframe permitted under the credit.Footnote 116 Once the documents are deemed to comply, the autonomous nature of the credit means that it should be virtually impossible to disrupt payment to the beneficiary.Footnote 117 Indeed, the only justification for non-payment would be where the beneficiary had engaged in wrongdoing or was aware of material misrepresentations in the documents and evidence of this was demonstrated within the short timeframe permitted for document examination.

Legal analysis aside, Lord Diplock's judgment has had significant practical consequences for the efficiency of the credit mechanism, ironically the very thing that he sought to safeguard. The orthodox account of the credit mechanism values the doctrines of autonomy and strict compliance equally; both are considered vital for the success of the mechanism. However, in United City Merchants, the repeated (and incorrect) references to apparent compliance as the contractual basis for payment undermined the significance of strict compliance. This overrode the agreed risk allocation in respect of defects known at the time of presentation. Characterised correctly, the risk of such defects falls on the credit beneficiary, since the presentation would not be complying and thus susceptible to rejection by the bank. Not only is this the allocation agreed by the parties in the credit by virtue of the doctrine of strict compliance, it is also the allocation traditionally recognised as the most efficient since the beneficiary is best placed to choose, and then exert control over, the person issuing the requisite documents.Footnote 118 In practice, Lord Diplock's judgment means that banks are obligated to accept documents known to be defective as good currency.Footnote 119 This is despite the fact that such documents have been colourfully described as ‘the cancer of international trade’.Footnote 120 At best, for example where the documents are forged and remain capable of serving their intended purpose, this is likely to reduce parties’ confidence in a mechanism dependent on the veracity of documents. The position is more concerning where the documents are null given the consequences for the ultimate buyer and the issuing bank in the event of the credit applicant's insolvency. It is also interesting to reflect on Lord Diplock's analysis in light of the ICC's International Maritime Bureau, a wing of the Commercial Crime Service, to which banks can refer documents for authentication within the period permitted for examination.Footnote 121 If Lord Diplock's account of the bank's obligation was correct, the referral service creates the distinct possibility that the bank would definitively know a document was incorrect yet nevertheless be compelled to pay.Footnote 122 While this is surely bizarre, it is impossible to direct too much criticism at Lord Diplock here; the Service was established in 1981 and may have not permeated judicial mindsets so soon after its creation. There is, after all, no reference to the Service in arguments made by counsel for the bank. However, the modern significance of the Service casts further doubt on United City Merchants since its role in relation to documentary credits would be considerably reduced if payment obligations were as Lord Diplock suggested. In advocating a new approach to defective documents, the practical shortcomings of the current fraud exception cannot be ignored, particularly given the policy considerations underpinning Lord Diplock's judgment.

Despite powerful academic dissents, Lord Diplock's analysis has remained persuasive in subsequent judicial considerations of documentary credits. This makes it all the more important that the proper treatment of defective documents is reconsidered in light of recent developments. Happily, this conflation is much harder to justify following the most recent version of the UCP and comparative case law on nullities. The most significant of these – the UCP 600 – was introduced in 2007 to overcome inter alia the high rate of discrepant presentations, estimated to affect 70% of presentations.Footnote 123

The UCP 600 deletes all but one reference to ‘on their face’. It is now explicit that the paying bank's contractual obligation is only engaged when ‘a presentation is complying’,Footnote 124 as distinct from a presentation which appears to comply. In cases where the presentation is not complying, banks ‘may refuse to honour or negotiate’ the credit.Footnote 125 The notion of apparent compliance now only appears in establishing the banks’ duty when documents are presented; namely to assess whether the documents ‘appear on their face to constitute a complying presentation’.Footnote 126 This reinforces the fact that banks must not look beyond the documents nor investigate their genuineness but simply conduct a visual examination of the documents.Footnote 127 This preserves the earlier position, established in Gian Singh, that banks which have examined documents without negligence will be entitled to reimbursement notwithstanding the subsequent discovery of defects.Footnote 128

Two matters pertaining to the standard of documents tendered under the credit have also been modified under the UCP 600. First, ‘complying presentation’ has been clarified as one in accordance with ‘the terms and conditions of the credit, the applicable provisions of these rules and international standard banking practice (ISBP)’.Footnote 129 By way of illustration, the ISBP does not recognise documents with typographical or grammatical errors as non-compliant where these issues do not affect the meaning of the documents.Footnote 130 Accordingly, this should ensure that immaterial discrepancies are not capable of disrupting payment. Secondly, the UCP 600, prima facie paradoxically, also establishes a more flexible approach to compliance by permitting certain tolerances between the documents and the goods. To be explicit, Art 30 permits a tolerance of +/-10% in cases where the amount of the credit quantity of goods or unit price are qualified with ‘about’ or ‘approximately’Footnote 131 and a tolerance of +/-5% of the quantity of goods is permitted in other cases, unless a stipulated number of items is explicit in the credit.Footnote 132 Significantly, this is a pragmatic response to the need to reduce the high number of discrepant presentations but it does not permit any degree of flexibility in relation to the quality of the tendered documents.

Null documents require further consideration. Lord Diplock left the matter openFootnote 133 and the issue subsequently came before the Court of Appeal in Montrod.Footnote 134 In that case, Potter LJ cited extensively from Lord Diplock's judgment and, after discussing the fraud exception at length, continued:

[The fraud exception] should not be avoided or extended by the argument that a document presented, which conforms on its face with the terms of the letter of the credit, is none the less of a character which disentitles the person making the demand to payment because it is fraudulent in itself, independently of the knowledge and bona fides of the demanding party. In my view, that is the clear import of Lord Diplock's observations in the Gian Singh case … and in the United City Merchants case.Footnote 135

This repeats the mistake of United City Merchants; null documents are tied to the fraud exception and beneficiary misconduct and not considered as a matter affecting compliance. Furthermore, the policy arguments used to justify this position were, with respect, specious. Potter LJ suggested that a nullity exception would result in ‘undesirable inroads into the principles of autonomy and negotiability’.Footnote 136 This supposes that nullities should be treated similarly to fraud by the beneficiary; as a defence to payment by the bank. This is misleading, since nullities are an aspect of documentary compliance affecting only the instant contract under consideration.Footnote 137 Viewed in this way, recognising nullity as a basis for rejection – and not a defence – should not engage any concerns about the autonomy or negotiability of the credit. His Lordship was also of the view that courts would struggle to comprehensively define nullity, which would thus render the law uncertain.Footnote 138 Having said this, however, Potter LJ then proceeded to suggest that ‘unscrupulous’Footnote 139 conduct – arguably a much woollier term than nullity – might justify banks’ rejection of presentations in future. This has yet to attract further comment in the case law. Overall, however, Potter LJ's judgment is unhelpful; it continues in the same vein as United City Merchants and extends that analysis to nullities.

Notwithstanding Potter LJ's policy arguments, the abandonment of references to ‘on their face’ in the UCP 600, much like the discussion above, means that the decision in Montrod is now difficult to reconcile with the UCP. Moreover, appellate litigation in Singapore has taken a different approach to nullity and provides another perspective from which to consider English law. In Beam Technology,Footnote 140 the credit required inter alia an air waybill and the buyer had notified the seller that this would be issued by freight forwarders, Link Express. It later transpired that the named entity did not exist, meaning that a document purporting to be issued by this company could only be a nullity. The Singaporean Court of Appeal, correctly it is argued here, treated nullity as an aspect of compliance:

While the underlying principle is that the negotiating/confirming bank need not investigate the documents tendered, it is altogether a different proposition to say that the bank should ignore what is clearly a null and void document and proceed nevertheless to pay. Implicit in the requirement of a conforming document is the assumption that the document is true and genuine although under the UCP 500 and common law, and in the interest of international trade, the bank is not required to look beyond what appears on the surface of the documents. But to say that a bank, in the face of a forged null and void document (even though the beneficiary is not privy to that forgery), must still pay on the credit, defies reason and good sense.Footnote 141

This, without doubt, departs from the position adopted by the House of Lords in United City Merchants. Furthermore, the Singaporean court suggested that the definitional issues identified by Potter LJFootnote 142 could be overcome:

… there could be difficulties in determining under what circumstances a document would be considered material or a nullity, such a question can only be answered on the facts of each case. One cannot generalise. It is not possible to define when is a document a nullity. But it is really not that much more difficult to answer such questions than to determine what is reasonable, an exercise which the courts are all too familiar with.Footnote 143

Consideration of the IMB document authentication service leads to the same conclusion on the definitional point, since it stands to reason that a workable definition of nullity must have been developed in order to identify documents as ‘fake or false’.Footnote 144 In Ren's critique of the nullity concept, however, he described the current absence of a definition as rendering the nullity concept ‘unworkable’Footnote 145 and suggested that reasonableness was not, therefore, a suitable comparator. A future English court, perhaps emboldened both by the Singaporean experience in Beam Technology and the existence of the IMB, would seem capable of defining nullity in a more concrete manner. This would seem to satisfactorily answer this aspect of Ren's critique. Accordingly, the paper concludes by determining how the foregoing analysis should affect the legal response to fraud and defects known at presentation.

Conclusion

This paper has argued that recent judicial and legislative developments require reconsideration of the key debates triggered by Lord Diplock's analysis in United City Merchants. Accordingly, consideration now turns to how a modern court should approach the fraud exception and documents known to contain defects on presentation.

To begin with the shape of the fraud exception, it will be recalled that Lord Diplock constructed the fraud exception narrowly so that courts could only intervene in the most exceptional of circumstances. To do otherwise, he argued, would ‘undermine the whole system’Footnote 146 on which financing by documentary credits was based. However, consideration of the American approach to fraud reveals that this policy consideration does not withstand scrutiny. This is because the broader approach to fraud enshrined in the UCC has not resulted in the commercial disruption feared by Lord Diplock and subsequent English courts. Conversely, in fact, Barnes and Byrne have welcomed the ‘specificity with which the LC fraud exception is addressed in section 5–109’Footnote 147 and attribute this to a reduction in litigation. In this way, the 1995 revisions achieve their aim, namely to reduce the likelihood of judicial intervention in credit transactions.Footnote 148

The development of the respective fraud rules also merits brief comment. The English rule, as we know, is wholly a product of the common law. By contrast, the American exception codified the decision in Sztejn Footnote 149 and was subsequently amended in 1995. This legislative process facilitated the ‘balance [of] competing interests or perspectives in a manner which fairly reflects the reasonable commercial expectations of the parties’Footnote 150 and, importantly, involved both banks and traders in the drafting process. This is an enviable positionFootnote 151 which the English judiciary cannot replicate within the confines of a single case. This lends further weight to the argument that the policy arguments said to justify the English exception are not fixed and demand reassessment in a suitable case.

This is not to say, of course, that England should simply import the American fraud exception. A continued preference for a narrow exception would be entirely acceptable; indeed, this much is explicit in the ICC's continued refusal to legislate for fraud in the UCP. If a future English court wishes to retain a narrow fraud exception, however, the American experience tells us that more compelling policy arguments will be required to justify this approach. The suggestion made here is that a modern court needs not only to strengthen the policy analysis of the fraud exception but also to view beneficiary wrongdoing holistically. To regard beneficiary wrongdoing as the trigger for the fraud exception is wholly correct since, on the analysis adopted here, all known defects will be dealt with as a matter of compliance. However, wrongdoing should be defined broadly so as to include fraud by the beneficiary in the underlying transaction. To do otherwise emasculates the notion of ex turpi causa and prevents the court from carrying out this important policy role. The current myopic focus on the documents is illogical and it would clearly be preferable if any fraud by the beneficiary in connection with the credit could oust the doctrine of autonomy. Indeed, in the context of preventing payment under a performance guarantee, the Court of Appeal have appeared receptive to the notion that fraudulent misrepresentation inducing the underlying contract justified judicial intervention.Footnote 152 It is hoped that this decision would be persuasive to the Supreme Court should a similar issue arise involving a documentary credit.

The second issue triggered by United City Merchants was the fate of documents known to contain defects at the time of presentation. As a reminder, Lord Diplock's analysis obliged banks to pay notwithstanding that the presentation contained a forgery.Footnote 153 This analysis was subsequently extended to null documents in Montrod.Footnote 154 The underlying premise of this analysis – that beneficiary knowledge was required before the bank could reject the presentation – was flawed. In this regard, the UCP 600 fundamentally changes matters and makes it much easier to recognise known defects as an objective issue affecting documentary compliance. Indeed, the abandonment of all but one reference to ‘on their face’ confirms that the beneficiary is only guaranteed payment in return for a ‘complying presentation’.Footnote 155 The notion of apparent compliance is now solely tied to the bank's entitlement to reimbursement in circumstances where, despite a visual examination of the documents, they could not have uncovered the defect.Footnote 156 Accordingly, the current UCP provides clear doctrinal support for a distinction between strict compliance and defences to payment.

So how then should a modern court respond to known nullities and forgeries? The weight of academic comment favours a right to reject nullities.Footnote 157 Clearly, there is no way that a null document can be described as complying if the defect is known at the time of presentation and so to require payment in these circumstances would be preposterous. To entitle rejection, conversely, is clearly correct when the broader significance of nullities for the ultimate purchaser and the issuing bank is considered. This approach, moreover, would reflect the rationale in Sanders v Maclean, which prioritised protection against insolvency in commercial transactions. Indeed, to do otherwise may well result in banks becoming less willing to finance documentary credit transactions.

Recent appellate litigation on nullities lends further support to the notion that null documents should justify rejection by the bank. In particular, the discussion in Beam Technology correctly distinguishes compliance from beneficiary wrongdoing and this analysis, in contrast to that in Montrod, is more compatible with the UCP 600. Critically, Beam Technology also provides a route by which to circumvent supposed definitional issues surrounding nullity which could be employed to distinguish Montrod in a suitable case.

However, academic commentators have failed to reach unanimity in respect of forged documents. At its broadest, the notion of non-conformity would entitle the bank to reject documents containing any known forgery, fraudulent misstatement or nullity at the time of presentation. There is considerable support for this standard of non-conformity,Footnote 158 including from Goode himself:

The short point is that the UCP and the terms of every credit require the presentation of specified documents, that is, documents which are what they purport to be, and there is no warrant for the conclusion that this entitles the beneficiary to present, for example, any old piece of paper which purports to be a bill of lading … even if it is forged, unauthorised, or otherwise fraudulent.Footnote 159

However, other commentators – including Goode elsewhere in his workFootnote 160 – have favoured a narrower approach which only recognises nullities as non-complying.Footnote 161 Goode's rationale was that the document in question remained capable of serving its intended commercial purpose; ‘the insertion of a false shipping date in the bill of lading did not prevent it from being what it purported to be’.Footnote 162 Respectfully, this is Goode having his cake and eating it too; it is impossible to champion the sequential analysis and simultaneously affirm the outcome in United City Merchants. Put simply, a falsely dated bill of lading is not a complying document and should thus justify rejection. Accordingly, the broad view of non-conformity is preferred here.

Of course, a broader conception of non-conformity carries the risk that more presentations would be rejected. This is significant given that the impetus for reform of the UCP was to reduce the high rate of discrepant presentations. This, it is submitted, would not cause problems in practice since the doctrine of waiver in the UCP enables the issuing bank to approach the applicant where the documents do not appear to constitute a complying presentation to authorise payment.Footnote 163 This should mean that defective presentations would only be rejected when payment had not been authorised by the applicant. We already know that waiver is used extensively in practice. In Ronald Mann's empirical study from the late 1990s, more than 70% of presentations in 500 credit transactions were discrepantFootnote 164 and these discrepancies ranged from minor, immaterial matters to substantive non-performance by the beneficiary.Footnote 165 Notwithstanding these discrepancies, full payment was made via waiver in all but one case, in which a payment of 94% of the contract price was made.Footnote 166 If applicants are typically prepared to waive documentary issues when they know substantive performance is forthcoming,Footnote 167 this should overcome concern about the disruptive effect of recognising forged documents as non-compliant. Indeed, the speed with which waiver was obtained in this study – typically within one banking dayFootnote 168 – coupled with the fact that waiver does not extend the time for document examination,Footnote 169 should allay fears that credit transactions will become less secure if forged and null documents are to justify rejection. The development of modern communications since Mann's study should facilitate both the speed of the waiver process and interactions between the contracting parties.Footnote 170 As a result, the prevalence of waiver in practice suggests that banks would only need to exercise an entitlement to reject rarely as a means of safeguarding their position. Critically, nothing in this analysis would prevent the beneficiary from retendering documents before the expiry of the credit.

The standard of proof, discussed earlier, is also relevant to the treatment of forged and null documents. The same time constraints which affect the invocation of the fraud exception would apply here; evidence of the defect would need to be established within five banking days to reject the documents as non-complying. This issue may well be less problematic in this context. First, evidence would be limited to the existence of the forgery or nullity itself; the applicant or issuing bank would not be required to attribute the defect to the beneficiary. This clearly reduces the evidential burden. In addition, the availability of the International Maritime Bureau's document authentication service, coupled with improvements in technology and communication, must surely allay the fear that a new approach to forged or null documents would be stymied by evidential concerns.

Much has changed in the legal world in the last four decades. In the context of documentary credits, the introduction of the UCP 600, the revised UCC and case law on nullities have been significant developments. However, the fraud exception remains unchanged; constrained within the same narrow parameters that Lord Diplock established in United City Merchants. Clearly the policy argument which dictated this decision – to preserve the efficiency of the credit mechanism – was compelling, but the flaws in Lord Diplock's analysis are clearly illuminated by these recent developments. It is hoped, therefore, that in a suitable case, a modern Supreme Court will confine United City Merchants to history so that the next 40 years are not premised on an outdated and flawed approach to fraud and documentary compliance.

Author ORCIDs

Katie Richards, 0000-0002-2201-7079