Introduction

The introduction of the ASBO in the late 1990s and of the post-conviction ASBO (CrASBO) in the early 2000s,Footnote 1 was presented by the then Labour Government as a direct response to ‘the newly identified scourge of anti-social behaviour’.Footnote 2 Although some of the kinds of behaviour commonly regarded as anti-social were already criminalised,Footnote 3 the introduction of these measures was justified by the alleged inability of the criminal law to deal swiftly and effectively with the cumulative effect of low-level criminality.Footnote 4 This was mainly due to the fact that the criminal law paradigmatically focuses on isolated events rather than on the cumulative effect of prolonged low-level criminality.Footnote 5 Other reasons included the costs of dealing with this kind of criminality and the barriers posed by the enhanced procedural protections – such as the higher standard of proof – afforded to those facing criminal prosecution.Footnote 6 For these reasons, an alternative method of regulation was sought that would deal with anti-social behaviour ‘effectively’ whilst circumventing the abovementioned obstacles.Footnote 7 To this end, the ASBO was an amalgamation of civil and criminal processes aiming to combine the best of both worlds.Footnote 8

Despite the Labour Government's efforts to encourage the use of the ASBO and the CrASBO,Footnote 9 the anti-social behaviour regime faced fierce opposition from human rights activists and academics and soon fell out of favour.Footnote 10 The ASBO, for instance, attracted significant criticism on the grounds that it was a de facto criminal measure, as well as for its expansive definition of anti-social behaviour; and the imposition of custodial sentences following breach of this supposedly civil order.Footnote 11 In response to the criticisms raised about the ASBO and in line with its promise for a more victim-oriented approach, the Conservative-Lib Dem Coalition Government promised the repeal and replacement of the ASBO by a more flexible and effective legal framework.Footnote 12

This paper begins by offering a critical evaluation of the ASBO's successor, introduced under Part 1 of the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014. Although at first sight the repeal and replacement of the ASBO by a purely civil injunction appears to be a positive development, the close evaluation of the ASBO's successor reveals that many of the concerns raised about the order and its potential misuse remain largely unaddressed.Footnote 13 The importance of this evaluation is heightened by the fact that the injunction appears to be operating in the shadows. This is primarily due to the paucity of empirical research on the implementation of the ASBO's successor and the Government's conscious decision not to collect data about its use, such as the number of successful applications made to court.

The paper then proceeds to offer original insights, based on an empirical study in two areas of England, on the implementation of the injunction focusing on the procedure followed by local enforcement agents when dealing with an incident of anti-social behaviour.Footnote 14 Although there is a significant body of literature on the ASBO, both at a theoreticalFootnote 15 and an empirical level,Footnote 16 this is the first empirical data collected and presented (that the author is aware of) on the implementation of the injunction. The findings presented in this paper suggest that the 2014 amendments had no substantial impact on the daily management and regulation of anti-social behaviour at a local level. The findings presented also highlight some important tensions that lie at the heart of practice, such as the need to prevent further anti-social behaviour while addressing its underlying causes.

The paper concludes by further reflecting on the data collected in both sites and identifies mechanisms through which some of the main concerns raised about the potential misuse of the injunction can be mitigated against. The importance of this analysis lies in the fact that based on the data collected, it is the implementation and the procedures in place at a local level that manage to constrain what is an otherwise far-reaching legal instrument.

1. Reflecting on the 2014 amendments

Although the ASBO was portrayed by the Labour Government as an effective means of dealing with anti-social behaviour,Footnote 17 the order attracted considerable academic criticism for three main reasons. First, one of the most contested and heavily criticised aspects of the ASBO was the statutory definition of anti-social behaviour which, according to Ashworth et al, was ‘sweeping and vague’.Footnote 18 Based on the wording of section 1(1)(a) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, any kind of behaviour could be regarded as anti-social as long as it was likely to cause ‘harassment, alarm or distress to one or more persons not of the same household as [the perpetrator] himself’.Footnote 19 The wording adopted afforded a significant magnitude of discretion to courts and local enforcement agents to determine the contours of the law, with some of its critics noting that this could potentially result in the ‘prohibit[ion of] conduct that is otherwise lawful and remains lawful if undertaken by anyone other than the defendant’.Footnote 20 This is due to the fact that the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, section 1(1)(a) focused ‘on the impact or potential impact of someone's behaviour on others’ rather than on its nature.Footnote 21

Secondly, another highly opposed feature of the ASBO was its hybrid nature. Similar to other civil preventive measures, such as the Football Banning Orders, both the ASBO and the CrASBO sought to address the behaviour at hand ‘by restrict[ing] the activities of the alleged protagonists by subjecting them to restrictions … supported by criminal sanctions when breached’.Footnote 22 Those who behaved in an anti-social manner could, for instance, through the issue of an ASBO, be excluded from a particular area where they would usually cause trouble. Although under the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, section 1(10) breach of the restrictions imposed, without reasonable excuse, constituted a criminal offence, the order was civil in nature.Footnote 23 This meant that some minor anti-social behaviour, accompanied by a breach of the restrictions imposed, could result in the imposition of a lengthy custodial sentence.Footnote 24 The CrASBO on the other hand, appeared to be less contentious than the ASBO since it could only be issued following a criminal conviction. There was no need however, for the triggering offence to be associated with the anti-social behaviour at hand. In fact, conviction for any criminal offence, accompanied by evidence of some unrelated and potentially minor anti-social behaviour, could (at least as the law appeared on the statute book) result in the imposition of a CrASBO.

Finally, concerns have been raised about the severity of the restrictions imposed on the liberty of those against whom these orders were issued. As Duff and Marshall point out, the restrictions imposed when an ASBO was issued could be so severe that they could constitute a form of punishment in their own right, albeit ‘not subject to the kind of constraint that could legitimise them as punishments’.Footnote 25 On this view, it was possible for the first limb of this two-part process of regulation to constitute a form of indirect criminalisation, ie the imposition of criminal punishment through the implementation of non-criminal interventions, and therefore the ASBO could operate as a de facto criminal measure.Footnote 26

At first sight, the repeal and replacement of the ASBO by a purely civil injunction can be regarded as a positive development, since it mitigates the concerns raised about the ASBO's hybrid nature.Footnote 27 The civil nature of the injunction, though, means that its implementation might attract less attention and external scrutiny. This is evidenced by the Government's failure to collect data about the implementation of the injunction. The importance of this lack of scrutiny lies in the potential punitive nature of the injunction.Footnote 28 Notwithstanding the shift to a purely civil method of regulation, the issue of an injunction can result in the imposition of even more burdensome restrictions on the liberty of those subjected to it than those that could be imposed through an ASBO. In particular, under the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, section 1, a court, through the issue of an ASBO, could impose any prohibitions it deemed necessary on the perpetrator in order to prevent them from behaving in a similar manner in the future. In contrast, the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, section 1(4) provides that the issue of an injunction can result in the imposition of both negative and positive requirements on the perpetrator.

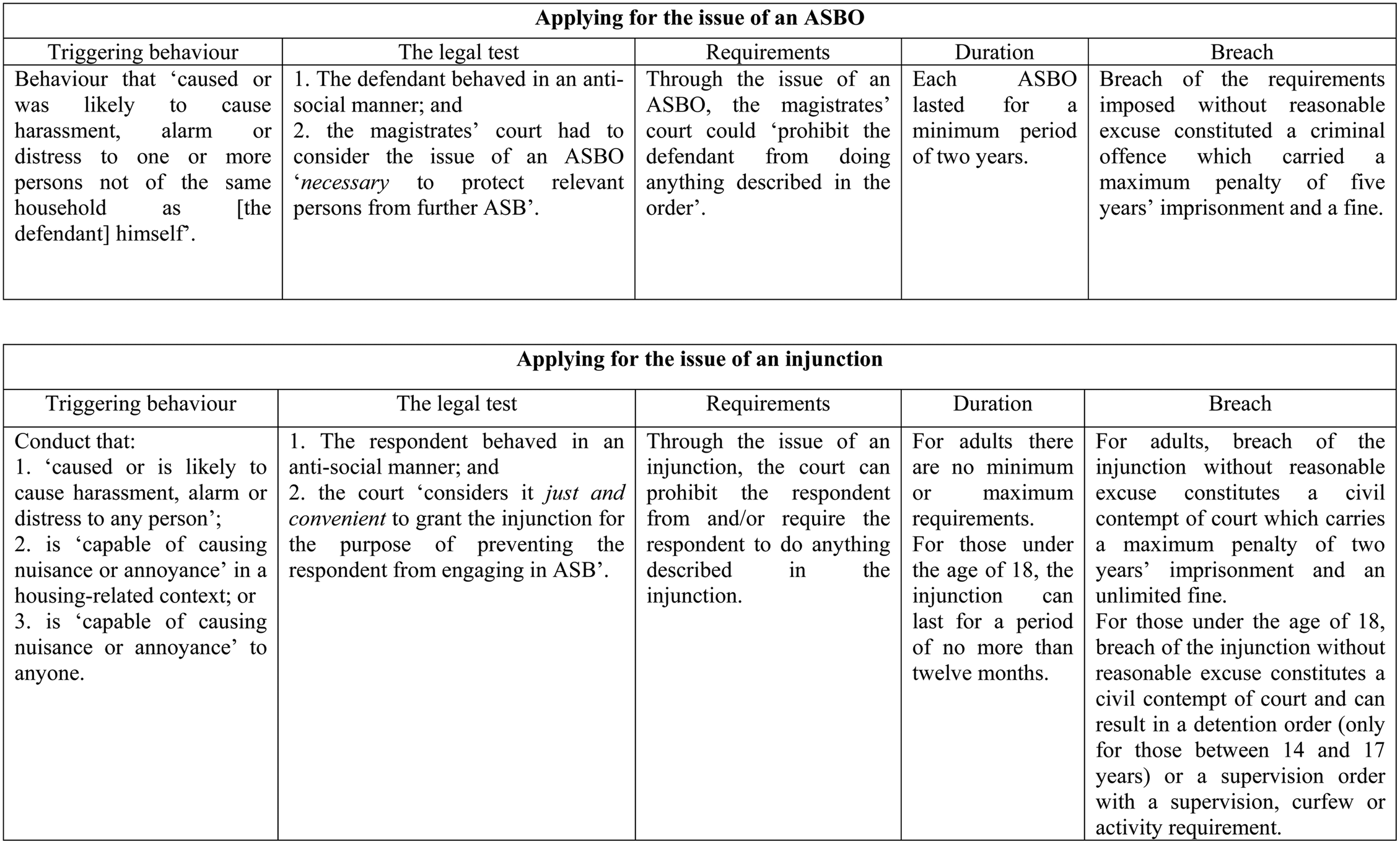

The potential severity of the restrictions that can be imposed on the liberty of those against whom an injunction is issued becomes even more worrisome in light of the fact that the threshold that must be met for the issue of an injunction is lower than the one required for the imposition of an ASBO.Footnote 29 As shown in Figure 1, an ASBO could only be issued if the court examining the application was satisfied that the order was ‘necessary to protect relevant persons from further anti-social acts’ by the defendant.Footnote 30 In contrast, a court examining an application under the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, section 1(3) must only consider ‘it just and convenient to grant the injunction for the purpose of preventing the respondent from engaging in anti-social behaviour’ (emphasis added) – something which can raise questions about the necessity and proportionality of the requirements imposed. Although the imposition of a lower threshold can partly be compensated by the abolition of the ASBO's minimum duration requirement, it still seems possible for the injunction to result in the imposition of significant and long-lasting restrictions on someone's liberty.Footnote 31

Figure 1: From the ASBO to the injunction

Moreover, although breach of the injunction does not constitute a criminal offence, those found in breach of the requirements imposed on them face a maximum sentence of two years’ imprisonment and an unlimited fine.Footnote 32 Hence, although the hybrid model adopted by the ASBO was abandoned, serious concerns can still be raised about the potential (punitive) ramifications that breach of this supposedly civil measure can have.

There is also evidence to suggest that the ‘ASBOs represent[ed] only the very tip of a much larger structure of proactive anti-social behaviour interventions’.Footnote 33 Evidence suggests that sometimes young people were forced to sign an acceptable behaviour contract (ABC)Footnote 34 out of fear of losing their accommodation, something that highlights the potential punitive nature of these informal interventions.Footnote 35

Allowing the state to criminalise behaviour indirectly through non-criminal interventions is morally problematic since it is possible for law enforcement agents to expand (even unwittingly) the reach of criminal punishment into areas that had been concluded by the legislature to be not appropriate for criminalisation. This becomes more problematic in light of the fact that those subjected to indirect criminalisation are denied, at least to some extent, all of those enhanced procedural protections afforded to those facing criminal prosecution.Footnote 36 In order to prevent this from happening, the European Court of Human Rights formulated the anti-subversion doctrine, which supposedly enables courts to look beyond the label attached to each legal instrument by the legislature and scrutinise the true nature of the penalty imposed on the perpetrator.Footnote 37 If, following the application of the anti-subversion doctrine, the court believes that the sanction imposed is criminal in nature, ie it constitutes a form of punishment, then the legal instrument at hand should be regarded as a ‘criminal charge’ and those against whom it is used should be afforded the same procedural and evidential protections as those facing criminal prosecution.Footnote 38

As far as the statutory definition of anti-social behaviour is concerned, it is worth mentioning that the ambit of the injunction extends well beyond that of the ASBO. The ASBO only dealt with behaviour that ‘caused or was likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress to … persons not of the same household’ as the perpetrator himself.Footnote 39 The injunction, on the other hand, not only deals with behaviour that ‘caused or is likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress to any person’ but it also covers conduct that is capable of ‘causing nuisance or annoyance’.Footnote 40 Consequently, through the 2014 amendments, the Conservative-Lib Dem Coalition Government failed to address the concerns raised about the subjective nature of the statutory definition of anti-social behaviour, and in fact extended the reach of the law even further.Footnote 41

It is evident from the above analysis of the injunction that although the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 was a great opportunity for the then government to address some of the many concerns raised about the ASBO, these remained largely unaddressed (at least as the law appears on the statute book). The failure of the 2014 Act to adequately address the abovementioned concerns, along with the potential absence of outside scrutiny regarding the use of the injunction, necessitates a close examination of how the ASBO's successor has been implemented at a local level.

2. Addressing anti-social behaviour at a local level

In this second part of the paper a qualitative analysis of the injunction will be provided. The data presented below was collated as part of a two-year empirical study conducted with local enforcement agents in two counties in England, focusing on the impact of the 2014 amendments on the daily regulation of anti-social behaviour. The data was collected between May 2015 and April 2016.

The identification of potential sites was based on the data published through the Crime Survey for England and Wales.Footnote 42 The study focused on one area with high levels of anti-social behaviour (Site A), and on one with significantly lower levels of anti-social behaviour (Site B). As part of this study, 29 semi-structured interviews were conducted across both sites. In Site A, 19 semi-structured interviews were conducted, ten with local practitioners, ie anti-social behaviour officers working for local authorities and housing associations, and nine with police officers.Footnote 43 In Site B, ten interviews were conducted, six with local practitioners and four with police officers.Footnote 44 The study focused only on local enforcement agents who had a daily interaction with anti-social behaviour and were responsible for the implementation of the injunction.

The data collected through these interviews were later analysed thematically. The findings of this study are presented in four subsections. The first subsection focuses on the procedure followed by local enforcement agents when notified about a potential incident of anti-social behaviour.Footnote 45 Central to the procedure followed in both sites is the level of risk posed by the perpetrator to the alleged victim and how this can be best managed and addressed. It is also worth noting that ‘risk’ had major implications not just in terms of the procedure followed before applying for the issue of an injunction, but throughout the whole process. The second set of data presented focuses on the various interventions utilised by local enforcement agents as a means of dealing with the perpetrator's behaviour. The findings of this study clearly suggest that the regulation of anti-social behaviour takes place primarily in the shadows, since local enforcement agents try to use a range of informal interventions before applying to court for the issue of an injunction. The paper next presents data on the requirements that local enforcement agents seek to impose on those against whom an application is made in court for the issue of an injunction. Although many research participants acknowledged how impactful these requirements can be on the liberty of the perpetrators, most of them firmly believed that they would only seek to obtain those requirements that are necessary and proportionate to the risk posed. The final set of data focuses on whether the injunction was used as a means of publically and purposefully condemning the perpetrators. Although the publication of certain information about perpetrators and their conduct was not deemed by many participants to be inappropriate per se, there was a general consensus that information should only be shared with those directly affected by the anti-social behaviour at hand.

(a) Procedure followed

Based on the data collected, it was evident that in both sites the administration of anti-social behaviour was primarily risk-driven. When local enforcement agencies were notified about a potential incident of anti-social behaviour, a risk assessment was carried out to assess the level of risk faced by the victim. This risk assessment comprised of ‘a series of questions which would be asked to the victims of anti-social behaviour to identify what risk level they are at: being standard, medium or high’ (Int.12/PO/Site B).

What was clear from the evidence collected in both areas was that the level of risk faced by the victim informed the entire procedure followed by local enforcement agents, and not just the initial stage of their investigation. According to one police officer, the level of risk faced by the victim ‘will [be] monitored until we have reduced that risk right down to a level where we can say actually “we have solved this problem. The person is no longer at risk”’ (Int.18/PO/Site A). As far as high-risk cases are concerned, evidence collected from both areas suggests that these cases were regarded as a top priority and were discussed at the local community safety partnership multi-agency meetings. As one police officer noted, ‘once a week we will meet with the local authority and we will basically discuss all of our high-risk cases and just check that we are doing everything that we can in a timely manner and that we have not missed anything’ (Int.12/PO/Site B).

The role and importance attributed to the risk posed to victims was an unsurprising discovery mainly due to the prevalence of risk assessments in the development of crime policies since the late twentieth century,Footnote 46 which led to what Feeley and Simon describe as the evolution of ‘new penology’.Footnote 47 Central to new penology is the ‘retrospective orientation of the criminal justice process’.Footnote 48 As Garland explains, perpetrators are increasingly ‘seen as risks that must be managed rather than rehabilitated’.Footnote 49 As a result of this, particular attention is paid by various criminal justice institutions, such as the police, to the level of risk posed by certain individuals rather than focusing exclusively on the nature of the wrong committed. In many jurisdictions,Footnote 50 risk calculating tools were incorporated in sentencing policies as a means of identifying and managing ‘those offenders who pose a real and present risk of harm to others’.Footnote 51 In similar fashion, in England and Wales, the ambit of the criminal law, especially with regard to terrorism-related activities, has been extended well beyond traditional inchoate liability to criminal offences ‘targeted at non-imminent crimes’.Footnote 52

The use of risk assessment tools to calculate the level of risk posed by those who behave in an anti-social manner appears to be a sensible approach, since these tools usually operate on ‘a standard set of criteria on which to base decisions of risk’ and therefore eliminate any elements of subjectivity.Footnote 53 This enables local enforcement agents to calculate more accurately the level of risk faced by those affected by the perpetrator's behaviour. Nevertheless, the outcome of these assessments should be approached with caution, especially when dealing with anti-social behaviour, for a number of reasons. First, the increased reliance on risk assessments in the 1990s played a pivotal role in the establishment of a ‘culture of control’ the main focus of which is how potential risks can be identified and excluded rather than reformed.Footnote 54 This shift from welfarism to crime management highlights an important tension faced by contemporary liberal societies, which not only need to reassure the public that potential risks are promptly identified and addressed, but also need to deal with the underlying causes of criminality.

Secondly, it is worth reiterating here that in contrast to the pre-2014 era, there is no need for the court examining an application under the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, Part 1 to consider the issue of an injunction (and therefore the imposition of certain restrictions on the liberty of the perpetrator) as a necessary means for the prevention of further anti-social behaviour.Footnote 55 Instead, the court only needs to be satisfied that the issue of the injunction is a ‘just and convenient’ response for the prevention of further anti-social behaviour.Footnote 56 This lower threshold, in conjunction with an extensive reliance on risk assessments, can result in the imposition of significant and potentially disproportionate (bearing in mind what the perpetrator has actually done rather than what they might do in the future) restrictions on the liberty of those who are thought to pose a risk to others.

Moreover, although a risk-based approach can be beneficial in terms of identifying potential wrongdoers, as O'Malley points out, this is also likely to create new risks, such as the social ostracisation of the potential wrongdoer.Footnote 57 Finally (and most importantly), a risk-based approach can result in the expansion of the net of social control. As pointed out by Ansbro, when assessing the level of risk posed by someone, ‘practitioners feel an understandable pressure to err on the side of caution’ and they might therefore decide to use the injunction pre-emptively despite the perpetrator not actually causing harassment, alarm or distress.Footnote 58 As mentioned above, this can lead not only to the inconsistent implementation of the law, but can also result in the imposition of disproportionate and potentially punitive restrictions on the liberty of those who are deemed to pose a risk to others.

As far as the sites under study are concerned, there was no evidence to suggest that the adoption of this risk-driven approach resulted in the pre-emptive and/or unjustifiable use of the relevant tools and powers.Footnote 59 In fact, many of the abovementioned concerns raised regarding the use of risk assessment tools were partly mitigated by the adoption of a multi-agency and multi-disciplinary approach.Footnote 60

Before illustrating how the adoption of this multi-agency and multi-disciplinary approach mitigated some of the concerns raised by the use of risk assessment tools, it will be instructive to elaborate further on the collaboration between the various enforcement agencies dealing with anti-social behaviour at a local level. The next testimony is illustrative of this close collaboration among the various enforcement agencies in both sites:

We must make sure that other agencies are aware of that person … so it is really the case that a lot more agencies are involved now. Obviously in the past it was unstructured … with this new computer system we can put entries into the system which the council can read instantly (Int.15/PO/Site A).

To emphasise the importance of these information-sharing agreements, one of the interviewees made reference to the case of Fiona Pilkington: ‘we all knew a little bit about it and this is where the sharing of information comes in. Each individual person had bits and pieces but it was never joined up and brought together’ (Int.18/PO/Site A).Footnote 61

What is of particular importance for the purposes of this paper is that high-risk cases were examined from various perspectives and a collective decision was taken as to the best way forward. The importance of this strategy lies in the very nature of anti-social behaviour, which on some occasions requires a multi-agency approach. This can be attributed to the fact that some people behave in an anti-social manner not simply by choice, but due to a number of deep-seated social problems that require careful attention.Footnote 62 Consequently, in order for local enforcement agents to be able to permanently address the perpetrator's behaviour, due attention and consideration must be paid to its underlying causes. To this end, local enforcement agents need to consult with other relevant institutions, such as the local mental health team, which might be in a better position to deal with the causes of the anti-social behaviour. This close collaboration with other agencies clearly enables local enforcement agents to assess more accurately both the needs and the risk posed by each perpetrator. Moreover, the adoption of this multi-agency and multi-disciplinary approach not only added an extra layer of review in the whole process, but it was also instrumental in the adoption of a less enforcement-led stance towards anti-social behaviour. The following narrative both explains how police attitudes towards homeless people changed following their collaboration with local practitioners who had a social care background and more experience in dealing with this group of people, and also illustrates how the adoption of this multi-disciplinary approach mitigated against some of the abovementioned concerns about the use of risk assessment tools:

The police had a very negative attitude to them … we had to work together for two weeks solid and they had a no-arrest policy and we got them to take off their hats, they still had uniform, to start breaking down those barriers which we found very difficult (Int.3/LP/Site A).

The above statement demonstrates how the occupational background of local enforcement agents can influence their approach to anti-social behaviour, and also highlights the impact that this might have on other enforcement agents.Footnote 63 Hence, despite the potential adverse effects that a risk-driven approach can have on the regulation of anti-social behaviour, these were compensated (at least to some extent) by the adoption of a multi-agency and multi-disciplinary approach in both sites.

Moreover, it was evident from the data collected from both sites that there was an effective ‘responsibilisation strategy’ in place.Footnote 64 As Garland explains, the ‘responsibilisation strategy’ refers to the process of connecting ‘state agencies … with practices of actors in the “private sector” and “the community”’ in order to delegate the responsibility of crime management and prevention.Footnote 65 As far as the sites under study are concerned, there was evidence to suggest that housing providers and the public were asked to take an active role in the policing of injunctions. Similarly, perpetrators were often asked, through the imposition of positive requirements, to address the underlying causes of their behaviour.

The delegation of responsibility to non-state actors and the public regarding crime management is not a new phenomenon.Footnote 66 Instead, it is a well-established form of governance through which society is regulated indirectly.Footnote 67 For O'Malley and Palmer a possible explanation for the rise of this form of social control is that ‘good governance came to be identified with dependency on expertise, as the locus of objective knowledge required for scientific and professional management of the social’.Footnote 68 The importance of this need to rely on expertise is even more apparent in the context of anti-social behaviour, the regulation of which involves ‘a diverse range of work [that] requires a comprehensive knowledge and skill set’.Footnote 69 As one police officer explained:

We will always look at a sort of multi-agency approach. If there are other agencies that can be involved in order to get them the kind of support they need in order to prevent them from committing further offences, we will ask them to get involved. (Int.27/PO/Site A)

As the following testimony demonstrates, this shift of responsibility can also be attributed to the limited resources available to local enforcement agencies: ‘there are not enough police officers as there used to be to deal with this and in theory you have partners who are trying to deal with it as well’ (Int.8/LP/Site B).

Overall, evidence from both sites suggests that the majority of the participants strongly believed that a multi-agency approach was the best way forward, both in terms of information-sharing and the administration of high-risk cases. This well-established multi-agency approach in both sites contrasts the findings of previous studies according to which there was ‘a lack of joined-up approaches within and between partners’Footnote 70 and ‘inconsistent attitudes towards information sharing’.Footnote 71 Some possible explanations for this include the limited availability of resources and the realisation by local enforcement agents that on many occasions anti-social behaviour is the precursor to a number of other issues that need to be addressed.Footnote 72

Regardless of the true causes and alleged efficacy of this responsibilisation strategy, attention should be paid to its potential adverse consequences as well. For instance, not only can an extensive responsibilisation strategy dramatically transform the criminal justice system, but it can also have a profound effect on the relationship between the state and the public.Footnote 73 The risk is that the state no longer assumes responsibility for the (mis)management of crime and anti-social behaviour, and instead accountability for failing crime prevention strategies can be shifted to non-state actors.Footnote 74 The result is that state agencies escape accountability for such matters and government institutions deflect blame that might otherwise be allocated by the public. Therefore, although the adoption of a multi-agency and multi-disciplinary approach towards anti-social behaviour is not a panacea, it can at least mitigate against some of the abovementioned concerns raised about the potential misuse of the relevant tools and powers, such as the regulation of purely innocent kinds of behaviour.

(b) Applying for the issue of an injunction

Evidence from previous studies suggests that applying to court for the issue of an ASBO was not, in general, a first resort measure for local enforcement agents.Footnote 75 Instead, according to Lewis et al, the measures used to address anti-social behaviour ‘form[ed] a pyramidal system of regulation’ with the ASBO being located at its apex.Footnote 76 Based on this system, those whose behaviour was deemed as anti-social would initially receive a warning letter urging them to alter their behaviour. Failure to comply with this warning letter would result in the issue of an ABC. The final stage would include an application for the issue of an ASBO.Footnote 77 Based on their findings, although the existence of this ‘pyramidal system’ was confirmed, in practice Lewis et al found that there were ‘myriad variations’ amongst the sites under investigation with some of them adding extra layers of regulation.Footnote 78

This pyramidal system of social control is closely associated with Ayres and Braithwaite's model of responsive regulation.Footnote 79 Responsive regulation starts from the premise that it is more likely for the regulator to ‘convince’ the regulatee to comply, in this case stop behaving in an anti-social manner, if a pyramidal system of regulation is in place.Footnote 80 The rationale for this system is for the regulator to ‘escalate to somewhat punitive approaches only reluctantly and only when dialogue fails. Then escalate to even more punitive approaches only when more modest sanctions fail’.Footnote 81 As Braithwaite maintains, if less punitive/coercive responses have been used first, then the regulation will be ‘seen as more legitimate and procedurally fair [and therefore] compliance with the law is more likely’.Footnote 82

Despite the different levels of anti-social behaviour experienced, evidence collected by this present study confirms the existence of a ‘pyramidal system of regulation’ in both sites, with the injunction located at its apex. In both sites, there was a genuine belief that applying to court for the issue of an injunction should generally be reserved as a last resort measure. As one local practitioner explained, ‘taking it to court, for me personally is failure on what we can do otherwise to remove the anti-social behaviour’ (Int.10/LP/Site B).

Figure 2 is illustrative of the procedure followed by local enforcement agents in both sites with regard to the management of anti-social behaviour. Initially, a risk assessment will be conducted in order to assess the level of risk posed by the alleged perpetrator. The next step will be an informal discussion with those involved in order to address the anti-social behaviour. If this does not work, then a warning letter will be issued against the perpetrator, explaining the potential consequences of non-compliance. There was strong evidence to suggest that in both sites local enforcement agents would then examine the possibility of utilising certain restorative justice (RJ) processes, with the majority of them noting that the most commonly used process was victim-offender mediation. As one interviewee from Site A noted:

We are trying to move … to a more restorative type of language and approach … [if] somebody has come to our attention for the first time and they are willing to engage we will try and look at restorative options. Will they be willing to write a letter of apology? Will they be willing to meet and have like a community conference? (Int.4/LP/Site A)

Figure 2: The standard process of regulation followed in both sites

A similar approach was also adopted in Site B. As one interviewee pointed out ‘we are using more of the RJ side of things … a lot of us have received RJ training and we are trying to get the local communities to solve the problem’ (Int.8/LP/Site B).

The importance of the adoption of a more RJ approach should not be underestimated. The use of victim-offender or community mediation in the context of hate crimes, for example, has been very successful in ‘reducing [victims’] emotional harm and preventing further hate incidents from recurring’.Footnote 83 This was also confirmed by one local practitioner, who argued that their ‘best success rate is around mediation’ (Int.9/LP/Site B). The availability of RJ processes also adds an extra and less coercive layer to the pyramidal system of regulation used in both sites. Consequently, those who behave in an anti-social manner are provided with more opportunities to comply before local enforcement agents apply for an injunction to be issued.Footnote 84 It should be borne in mind though that the use of RJ processes is contingent upon the willingness of both the perpetrator and those affected by their behaviour to participate.

Evidence from both sites also suggests that when the level of risk posed by that person was high, then the perpetrator would move through (or even skip some of) the above steps very quickly. One interviewee noted that ‘if there is physical violence or if there is a hate element it will be much more likely to go to court and speed it up’ (Int.5/LP/Site A). This replicates the findings of previous studies which demonstrate that the use of formal legal action was neither a first nor a last resort measure.Footnote 85 Instead, this was done ‘on a case by case basis … depending on the specific facts of the incidents reported’ (Int.3/LP/Site B).

Despite the move towards a purely civil injunction, it was evident from the data collected that in both sites the regulation of anti-social behaviour takes place in the ‘shadows’, with local enforcement agents utilising an array of informal interventions before an application is submitted to the court for the issue of an injunction. Notwithstanding the potential benefits of responsive regulation, ie seeking to achieve compliance through less punitive interventions before resorting to formal (and potentially more punitive) legal action, it is apparent that robust review procedures must be put in place in order to ensure that these informal interventions are not operating as de facto criminal measures.

(c) Requirements imposed

The presence of the aforementioned system of regulation appears to provide perpetrators with ample opportunity to alter their behaviour, and demonstrates that applying to court for the issue of an injunction is usually reserved as a last resort measure. It should be borne in mind though that the pinnacle of the pyramid is enforcement, which can still result in the indirect criminalisation of certain kinds of anti-social behaviour. Hence, despite the presence of this pyramid, it is still imperative to scrutinise the ramifications that enforcement can have on those who reach the apex of this system.

As expected, and in line with the findings of a previous study, according to many participants, the most common types of restrictions imposed on those against whom these measures were used included: ‘(i) people being prohibited from doing certain things; (ii) going to certain places; (iii) being with certain people; and (iv) being out and about in certain times’ (Int.2/LP/Site A).Footnote 86 As acknowledged by one interviewee, congregating with certain individuals, entering into specific parts of town or feeding pigeons ‘appear to the surface to be everyday lawful activities’ (Int.4/LP/Site A).

Most of the participants also made particular reference to the imposition of positive obligations and their potential benefits. Some of the most commonly cited examples included: (i) attending drug or alcohol related treatments; and (ii) engaging with the ‘mental health services’ (Int.8/LP/Site B). The importance of this, according to many of the participants, lies with the fact that if ‘someone is addicted to drugs and you just tell them to stop, then they will not stop’ behaving in an anti-social manner (Int.16/LP/Site B). For this reason, local enforcement agents tried to utilise positive requirements in an attempt to address the underlying causes of anti-social behaviour (Int.8/LP/Site B). As the following testimony illustrates, if the perpetrator refused to utilise the services provided to them, then local enforcement agents could apply for the issue of an injunction as a means of forcing the perpetrator to engage with the relevant service provider: ‘For me is about using enforcement as a tool to get people to engage in social care and make significant sustainable changes in their life style. That is the only way it will sit comfortably with me’ (Int.3/LP/Site A). As another local practitioner noted, obtaining an injunction is not a panacea for addressing the underlying causes of anti-social behaviour: ‘if we know that someone would never stick to anything, then we would never want to set up someone to fail’ (Int.20/LP/Site A). Rather, based on their account these measures should only be used if there is a realistic prospect of success.

The use of the injunction on purely paternalistic grounds can be criticised for denying perpetrators the opportunity to reject treatment. Rather than treating the perpetrator as a rational agent who is capable of deciding whether (and how) he should address the underlying causes of his behaviour, local enforcement agents seek through formal interventions (approved by courts) to dictate what they regard as the most appropriate treatment.Footnote 87 That said, this finding should be examined in light of the multi-agency and multi-disciplinary approach adopted in both sites which enabled local enforcement agents to examine high-risk anti-social behaviour from various perspectives. Participants to these multi-agency meetings had different skills, backgrounds and experience, all of which were brought together in order to reach to a collective decision as to the best way forward. Moreover, the importance attributed to the underlying causes of anti-social behaviour demonstrates that even when someone reaches the apex of this pyramidal system, they are still provided with an opportunity to change their behaviour.

Although many of the participants acknowledged that some of the requirements imposed interfered with the perpetrator's liberty, for most of them this interference was warranted because their objective was to ‘prevent them from conducting behaviour which is not acceptable’ (Int.19/PO/Site A). As one police officer noted:

If somebody has not stepped over the line, they will be allowed to carry on doing what they were doing. If they have stepped over the line … then yes it would stop them doing something that might be legitimate to them, such as walking down the high street. (Int.14/PO/Site B)

To support the justifiability of these restrictions, most of the participants emphasised that they should be both necessary and proportionate:

We always say ‘Is it necessary to ask for that restriction?’ and ‘Is it proportionate to ask for that restriction?’ … If we do not feel that we have the evidence to support and say ‘yes’ to both of these questions, then we would not have included them. (Int.4/LP/Site A)

Although local enforcement agents firmly believed that the requirements imposed were necessary and proportionate to the risk posed by the perpetrators, prohibiting someone from engaging in otherwise lawful activities can be criticised for creating personalised prohibitions which only apply to certain individuals rather to the whole of society. This clearly raises serious concerns about the actual (if there are any) limits of the anti-social behaviour legal framework in terms of the restrictions that can be imposed on the liberty of those whose behaviour is regarded as anti-social, despite this shift to what appears to be a purely civil injunction. Moreover, it highlights the potential for these measures to be implemented inconsistently across England and Wales. The adoption of the abovementioned pyramidal system though can contribute to the consistent implementation of the law, while the adoption of a multi-agency and multi-disciplinary approach can act as a safety net against the misuse of these measures.

(d) As a means of communicating censure?

The implementation of the ASBO was heavily criticised due to the ‘naming and shaming’ practices used by many local enforcement agencies in previous years,Footnote 88 which contributed significantly to the demonisation and social ostracisation of certain social groups, such as young people.Footnote 89 Nonetheless, in R (on the application of Stanley) v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis the publication of the ASBO recipients’ personal details along with the restrictions imposed on them was deemed compatible with the provisions of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, ie the right to private and family life, with the court noting that the publication of this kind of information was essential for the effective enforcement of the ASBOs.Footnote 90

A similar approach with regard to the publication of information about those who behave in an anti-social manner is adopted under the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, with the Statutory Guidance emphasising the need to reassure victims and local ‘communities that action is being taken’.Footnote 91 Although the publication of certain information can be necessary for the effective enforcement of the requirements imposed, it was evident in some cases, such as in Stanley where colourful language was used against the perpetrators, that this could also be used as a means of publically condemning the ASBO recipients. This led many legal commentators, such as Duff and Marshall and Brown, to label the ASBO a de facto punitive measure.Footnote 92

In Site A, most of the participants stated that they would publicise information about the perpetrator and the restrictions imposed on them only to those affected by their behaviour, in order to facilitate the effective policing of the measures put in place (Int.19/PO/Site A). As one local practitioner explained, ‘you have to be very proportionate as to how you ensure that people are aware of the order … if a person is banned from going to Co-op you do not need to inform the national press about it?’ (Int.16/LP/Site A).

Moreover, what was clear from the evidence collected is that for the majority of the participants it was important to ensure that ‘each case [was] dealt with on its own merits’ (Int.21/PO/Site A). The following account provided by one local practitioner is representative of most of the testimonies given in Site A:

Every case needs to be risk-assessed … there will be a multi-agency risk assessment that will need to take place. What are the risks to the individual if the public finds out about what they have done? You look at age. You look at personal circumstances. (Int.9/LP/Site A)

The need to take into account the potential impact that the publication of certain information might have on the perpetrator was emphasised by many participants, especially in cases involving young people. As one local practitioner mentioned, publicising information about a young individual can be counterproductive because it is likely to ‘increase the fear of harm and the negative views about young people’ (Int.2/LP/Site A).

Nonetheless, many interviewees noted that under certain circumstances information should be shared more widely. They noted that this would only happen in cases where the ‘victim is at real risk and any further anti-social behaviour by the perpetrator … can make them really suffer’ (Int.29/PO/Site A). For three out of the 19 participants from Site A, however, it appeared that ‘the norm is that if you are dealing with an adult, then you are going to inform the public’ (Int.23/PO/Site A). One police officer noted the following: ‘I think it is not necessarily a bad thing. I think that other people from the wider society have a right to know if somebody has breached the law in a sense and has certain conditions in order to safeguard and protect them’ (Int.21/PO/Site A). This officer then went on to explain that through this process the public are also made ‘aware [of the requirements imposed and] are able to notify the police that they [were] breached’ (Int.21/PO/Site A).

In Site B, five out of the ten participants mentioned that certain pieces of information were only shared with those affected or likely to have been affected by the perpetrator's behaviour. As one local practitioner explained:

We will always consider to who we are telling about this … so we told the estate what has actually been done because we obviously believed that everyone would have been affected because of the nature of the behaviour and because of where the behaviour was happening. (Int.16/LP/Site B)

As one interviewee noted, to publicise information to people who have not been affected by the perpetrator's behaviour ‘would be a disproportionate’ response (Int.17/PO/Site B). Again, it was clear that the sharing of information was ‘case specific’ (Int.8/LP/Site B). A risk-assessment was carried out in advance, taking into consideration the impact of the perpetrators’ behaviour and any personal issues they might be facing, such as mental health issues (Int.8/LP/Site B). One interviewee noted that in order for them to publicise the issue of an injunction the behaviour in question must have had a ‘community impact’ (Int.8/LP/Site B). They stated, however, that their aim was to ‘inform [the public] rather than to identify’ the perpetrators (Int.8/LP/Site B).

As far as the remaining five participants are concerned, there was an impression that ‘the public at large need to be advised … because clearly that person has not changed from all the efforts you have put in beforehand’ (Int.22/LP/Site B). The following statement is illustrative of this approach:

It is incredibly difficult to prove that somebody has breached the sanctions that they have been placed upon them without the community taking ownership. It was never a particular popular concept across the country. You know the old ‘name it and shame it’ … Did it breach their human rights? My personal opinion is that the rights of the victims should be held at a higher level than the rights of the perpetrator (Int.9/LP/Site B).

The above testimony is not to suggest that in Site B ‘name and shame’ practices were used. Rather, it is to illustrate that half of the participants from Site B were in favour of a broader approach in terms of how information about the perpetrator and their behaviour should be managed. Indeed, these participants emphasised that such measures can hardly be monitored. As one police officer pointed out ‘unfortunately, there are not enough of us to police every single injunction or criminal behaviour order. So, we rely upon whoever sees or if the victim sees to come forward with the details of the breaches’ (Int.13/PO/Site B).

Based on the data collected, the proportion of local enforcement agents from Site B who were in favour of wider publicity was higher than Site A, where the vast majority of the participants advocated for a more measured approached. Nonetheless, evidence from both sites suggests that in most cases information about the perpetrators was only shared with those directly affected by their behaviour as a means of facilitating the effective policing of the requirements imposed rather than as a means of publically condemning those who behaved in an anti-social manner. The importance of this finding lies in the potential impact that ‘name and shame’ practices can have on those subjected to the measures. Such practices can result not only in the stigmatisation and social ostracisation of certain individuals, but in a ‘risk obsessed’ society they can also be utilised to legitimise – by increasing the level of insecurity in society – more punitive methods of regulation in the absence of compelling evidence.Footnote 93 In the context of anti-social behaviour, this might result in the extensive use of the injunction pre-emptively and the imposition of disproportionate restrictions on the liberty of those subjected to this measure. This not only highlights further the welfare–crime management tension that lies at the heart of practice, but it also demonstrates the need for robust procedures at a local level through which it can be ensured that the injunction remains a preventative rather than a punitive measure.

Conclusion

At first sight, the repeal and replacement of the ASBO by a purely civil injunction appears to mitigate some of the concerns raised about its hybrid nature. For Brown, this shift towards what appears to be a less punitive approach to anti-social behaviour is part of the Coalition Government's efforts to re-brand the new anti-social behaviour regime in an attempt to ‘change the [negative] narrative associated with the ASBO’.Footnote 94 As part of this re-branding effort, the Coalition Government promised a more victim-oriented approach whilst providing local enforcement agents with the flexibility needed to deal with anti-social behaviour swiftly and effectively.Footnote 95 Still though, this shift towards a purely civil injunction should be approached with caution. The reason for this is twofold. First, the implementation of the injunction might not be subjected to the same level of judicial and academic scrutiny due to its civil nature. This is further evidenced by the Government's decision not to collect data regarding the number of applications submitted for the issue of an injunction to courts. The importance of this omission is heightened by: (i) the data published by the Crime Survey for England and Wales, which found that almost 37% of the adult population has experienced some kind of anti-social behaviour in the year ending in December 2018; and (ii) the fact that the implementation of the injunction can still operate as a de facto criminal measure, despite this shift towards a purely civil response.Footnote 96

Secondly, notwithstanding the 2014 amendments, it was evident from the data collected that in both sites the regulation of anti-social behaviour takes place primarily in the ‘shadows’, with local enforcement agents still relying heavily on various informal interventions before applying to court for the issue of an injunction.

Notwithstanding the concerns raised about the potential misuse of the injunction, it was evident from the data collected during this study that in both sites under investigation, the implementation of the injunction was informed by the principles of necessity and proportionality. That said, the findings of this study should be approached with caution, since they do not necessarily represent how the anti-social behaviour tools and powers are implemented across England and Wales. The Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 provides local enforcement agents with a considerable magnitude of discretion both in terms of the scope of the law, i.e. how anti-social behaviour is to be conceptualised, and its implementation.Footnote 97 Moreover, it should be borne in mind that this study examined the implementation of the injunction from a practitioner's perspective. Those against whom the anti-social behaviour measures were used might feel that the requirements imposed on them were grossly disproportionate and that they amounted to a form of punishment in their own right.

Despite the limitations of this study, its findings can be further analysed in order to identify those factors that contributed to the adoption of a more welfarist as opposed to enforcement-led approach, whilst mitigating some of the concerns raised about the potential misuse of the injunction. It is argued that these factors can inform existing anti-social behaviour policies as a means of preventing the injunction from operating as de facto criminal measure while securing a more consistent implementation of the law across England and Wales.

Analysis of the data collected reveals three main factors that can contribute to this end. First, it was evident upon closer scrutiny of the data collected from both sites that in most of the participating institutions there were both internal and external review procedures in place. As to the former, most of the interviewees pointed out that ‘it is not just one officer on their own’ who decides whether someone's behaviour is anti-social and whether they should apply for the issue of an injunction (Int.12/PO/Site B). The procedure followed by local enforcement agents was largely determined by the outcome of the risk assessment carried out after a potential incident of anti-social behaviour was reported to them. After the initial assessment was conducted by the ‘call taker’, the case was then assigned to an anti-social behaviour officer who would review the incident further (Int.21/PO/Site A). It was clear that there were a number of review layers throughout this process, to ensure that the implementation of the injunction adhered to the guidelines issued by ‘people in high command’ (Int.15/PO/Site A).

Reference was also made by most interviewees to the local multi-agency meetings held on a regular basis. It was evident in the data that these multi-agency meetings enabled local enforcement agents to combine their knowledge and expertise, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the perpetrators’ behaviour and needs. It is worth mentioning that this multi-agency and multi-disciplinary approach was not limited to information-sharing agreements, but it also included a close collaboration between the various institutions and collective decision taking.

The presence of these internal and external review procedures also promotes professional accountability. Moreover, the presence of these review procedures can result in the more consistent implementation of the law at a local level. Conducting a risk assessment, for instance, allows local enforcement agents to better assess the level of risk posed by the perpetrators.Footnote 98 As rightly pointed out by Donoghue, though, ‘divergence in the organisational cultures, practices and experiences of [the relevant] agencies means that anti-social behaviour is identified and categorised inconsistently’ even within the same area.Footnote 99 Robust external review procedures can partly compensate for these divergences, and can lead to a more structured and coherent approach at a local level while constraining an otherwise expansive legal framework.

Another important factor that prevented the adoption of a purely enforcement-led approach was the fact that most of the interviewees acknowledged that on many occasions anti-social behaviour involves complex situational and contextual causal variables. As many research participants pointed out, some of the main causes of anti-social behaviour included alcohol problems, drug misuse and other socio-economic issues which created a vicious circle of anti-social behaviour and criminality. This led them to the realisation that a purely enforcement-driven approach is not always the answer to such problems. Instead, most of them believed that the administration of anti-social behaviour should be complemented by an attempt to address the underlying causes of this behaviour. Central to this realisation was the need to work with the perpetrators in order to divert them away from anti-social behaviour and criminality. Consequently, there was a shift towards a more welfarist approach as a means of providing the perpetrators with the support needed in order to tackle what really causes them to behave in an anti-social manner. This also enabled local enforcement agents to address (at least to some extent) the tension between welfarism and crime management that lies at the heart of practice.

Finally, another decisive factor that contributed towards the adoption of a more welfarist approach to anti-social behaviour was the fact that many local enforcement agents planned their strategies whilst contemplating what the potential implications of their actions on the perpetrator would be. As the following testimony illustrates, before applying to the court for the issue of an injunction, local enforcement agents tried to design the proposed requirements in a manner that would not pose barriers to the perpetrator's needs: ‘It has to be specifically related to their offending behaviour. You know you cannot just say “You cannot go to retail shops because you are a shoplifter”. That person is going to say: “How am I supposed to buy my shopping?”’ (Int.26/PO/Site A). This need to consider what the potential implications of their decisions on the perpetrator could be, was also particularly prevalent when deciding the level of publicity required for each case.

By contemplating the potential implications of their decisions and by acknowledging the need to address the underlying causes of anti-social behaviour, local enforcement agents were able to move away from a censure-based approach towards a more welfare-driven strategy. This led to the realisation that a purely censure-based approach which fails to engage with these problems is likely to result in a vicious circle of anti-social behaviour and criminality, which will inevitably stigmatise perpetrators further and possibly lead to their social ostracisation.Footnote 100