INTRODUCTION

In August 2017 Middle Temple Library re-organised its main collection of textbooks from alphabetical arrangement into subject order using the Moys Classification Scheme. This was part of a plan to classify all of the main texts in use at Middle Temple. The remainder of the books (approximately 20,000 volumes), which consist of previous editions and superseded books kept in the basement, are being classified for a move planned in August 2018. This article will cover both the process and impact of the first part of the project, and the progress of the second larger half of the project which is looming ahead of us.

THE LIBRARY

Middle Temple Library is a legal reference library which serves The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, one of the four Inns of Court (the other three being Inner Temple, Gray's Inn, and Lincoln's Inn). As well as being essential for admittance to the Bar, these Inns play a supporting and educational role in the lives of practicing and future barristers, providing them with a hub for their legal studies and careers. Each Inn offers a library service (amongst other benefits) to its members for both their studies and their legal work.

Though Middle Temple Library's history possibly goes back as far as the time of Henry VIII, the library really came into being in 1641 when a member of the Inn, one Robert Ashley, bequeathed 3,700 volumes of his personal collection to the Inn, as well as a sum of £300 to a library keeper. This generous contribution forms a part of the history of the library and is now part of a collection of over 9,000 early printed books and 300 manuscripts which are in addition to the core of our main collection containing over 250,000 volumes that cover a range of research resources on British, Irish, EU and US law in the form of law reports, journals, textbooks, loose-leafs, e-books and databases.

Middle Temple Library is very much what one might think of when they think of a library. A long airy space with a high ceiling and that distinctive gentleman's club feel in the decor and arrangement of materials. It's not such a surprise then that a library such as this might take a while before considering changes that are visible to the eye. If one thinks of any library made in the mould of the gentleman's library, one would not imagine classification stickers on the spine of a book. For many years, library staff were told that a classification scheme was not possible due to a dislike by the members, and in particular the Benchers (i.e. senior members of the Inn) of such labels. Thus the books were traditionally shelved by author (or title for edited works) with their location (consisting of a bay number) written in pencil on the front fly-leaf. It would take a lot of archival research to learn the truth of the matter, however, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

Figure 1. The Middle Temple Library: a view from the gallery.

The alphabetised scheme worked well for years and is still working with the majority of our materials. However, it fell down whenever we had to move books, as it meant re-cataloguing every title to show its new location and erasing and re-writing the bay number in each individual book. Additionally, members were increasingly requesting books by their subject, rather than their author. This was especially true for younger members and students. As the textbooks comprised a smaller portion of the overall collection they seemed ideal for classification into subject order. Unlike periodicals or law reports, the textbooks do not extend into date ranges that take up entire bays. They do not require as much forward thinking in terms of space allocation for growth - as we all know, a nudge and push here is sometimes all one needs to open up the shelf to another book. Alphabetisation continues to serve our journals and law reports well, but classification has definitely allowed us to exploit the presence of our textbooks to better effect.

THE SCHEME

Middle Temple Library is using the 5th edition of the Moys Classification and Thesaurus for Legal Materials, first published in 1968 by librarian Elizabeth Moys, a founding member of BIALL. Moys is designed to work with the Library of Congress Classification scheme, expanding on its K class for legal materials. It uses notations that can fit into both LCC's K class and Dewey's 340s, allowing libraries to both integrate legal materials into wider collections and not be limited by schemes that aren't expansive enough when it comes to covering the law.

Materials are arranged in a fairly logical manner, with primary and secondary materials separated, the former (law reports, journals, etc.) being ordered by format, and the latter by subject (textbooks, monographs, etc.). Like most schemes, subjects are ordered from the general to specific, the schedules beginning at K for reference items, KA for jurisprudence, KB for comparative law, KC for international law, KD for religious legal systems, KE for ancient and medieval law, KF-KW for modern law arranged by jurisdiction, KZ for non-legal subjects, and an appendix for criminology. There is also a thesaurus for quick classification, and tables allowing for number building through Cutters (alphanumeric codes that allow for finer sorting) as well as number substitutions.

Importantly, for us, Moys has an understanding of how law library users approach the materials they use, which is why the primary and secondary materials are separated the way they are. There's an understanding that where textbooks are concerned unknown quantities are made better visible through subject arrangement, whereas law reports, very much known quantities, need only be made accessible through good library signage or library guides. Most library users know the report they want, and simply need to know where to get it. With textbooks there's always an element of ‘do you have a book dealing with?’ and Moys recognises that distinction, allowing for two kinds of order using the same scheme.

Figure 2. Law journals in the library.

There is much more to be said about the scheme itself, but I'll limit myself here to how we took advantage of its flexibility when it came to arranging our materials.

THE BOOK MOVE

Moys was implemented in two very distinct phases. The first phase began before I started my role as Assistant Librarian in April 2017. By the time of my arrival, my predecessor Louise James had already classified the main textbook collection of near 3,000 titles, spread across two floors of the library. There was plenty of preparatory work already done so I was able to get stuck into the project right away. A Gantt chart lay out the projected progress of the work as well as how particular tasks had been allocated. A spreadsheet was on hand listing all the new classifications, which had already been added into catalogue records. This meant we had two sets of classmarks running in parallel for a while, but this would be dealt with after the reorganisation of the books.

Figure 3. Moys Classification.

The first task allocated to me was to put together a plan to move all the classified books into their new order during our summer closure. What followed was a labelling spree between May and August where we attached labels to their spines in preparation for the move. The classification marks had already been written in prior to labelling, which made the labelling process easier. Once the books were all labelled, it made their re-organising much easier too, as visible classmarks allowed for quicker sorting. With all the textbooks labelled, it was now just a simple matter of physically shifting the books.

This was done over two and a half days, during which the whole team removed all labelled books from their shelves, sorted them into classmark order across tables and trolleys, re-shelved them into subject order, and then erased the old locations from each book. After the team had finished with the physical aspect, we split the work amongst us of editing the catalogue records to remove references to the old locations of the textbooks, and within a week the book move for all intents and purposes was complete and a success, measured by the fact that members of the library team were still talking to each other.

THE NEW ORDER

Our textbook collection is comprised of works that cover common law in England and Wales, as well as the Inn's specialisms of Irish law, US law, European and EU law, and international law. Prior to re-classification, the collection had a loose subject division, in that there was an English common law section, international law section, an Irish law section, a Europe and European Union law section, a human rights section, and a section on Scottish law. Within these physically divided sections, all works were filed alphabetically. This wasn't without its merits. All systems of organisation have some value, and for our members the value was in their being able to locate the books of authors most used by them, books that had only marginally shifted to the left or right over previous years. However, as a scheme based on the alphabetical organisation of titles by their author names, there was the obvious drawback of not being able to offer our members the opportunity for some serendipitous searching.

Figure 4. US law at US KL.

Re-ordering the textbooks from alphabetical into subject order has changed the nature of interaction between our members and our textbook collection. Those who know what book they want can learn its new location and still go straight to that book. Those looking for useful materials on a particular subject have guidance in the form of classmarks that allow them to discover a range of materials related to each other. The impact of the switch from alphabetic to subject order became apparent within weeks of the change through the increase in the number of books removed from the shelves. The uptake has been noticeable and we are continuing to see a greater portion of the collection being used.

Figure 5. Classified books on a shelving trolley.

Moys has thus far been fairly adaptable in how we want the classification scheme to work (more as guidelines than rules). The priority concerning how we are classifying is whether the work classified will find its reader, and from where is that work likely to find its reader. As so often happens, works can be classified into more than one area, and most of the time Moys is equipped to handle this. Some areas are a bit lacking (the arrival of a book on Brexit was quite the afternoon), but again, the scheme is malleable enough to tweak for our own uses, which we have done in a number of places.

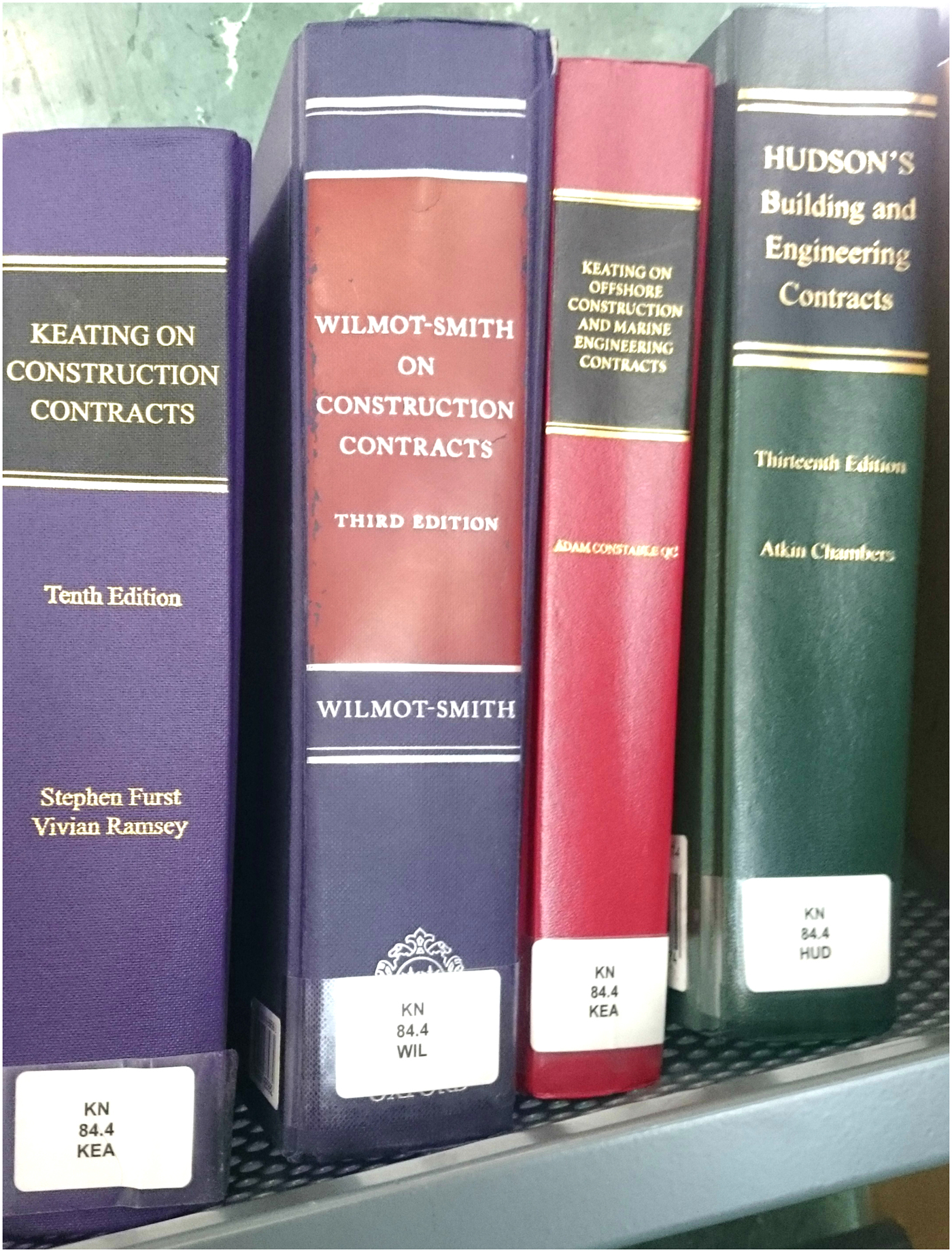

Prior to my arrival at Middle Temple, it had already been decided that our US collection would have a prefix to identify jurisdiction, rather than a Cutter. This works for us perfectly because the US law section is physically separate from the rest of our collection and having US as a prefix allows for members to make a mental shortcut in terms of the difference between KN 10 (KN 10 being contract law) and US KN 10. Similarly, as the Inn specialises in Irish law, we have decided to use the prefix IE instead of the addition of .I5 to classmarks to indicate common law in Ireland. Both US and Irish collections would be scattered to some degree if integrated into the wider collection, so for the meat of the classmark we use Moys, and for added accessibility, our own prefixes.

As European and European Union law is one of the library's specialisms, there's a great deal of scrutiny applied to books that straddle international and European/European Union law, and where we think those books are more likely to find a reader through shelf-browsing. In one area, our solution has been to lift out a small portion of the international law section and create an annex of sorts at the end of Europe (KV) where we can use the slightly tweaked numbers, but still within the parameters of how the scheme functions. Classifying materials on Europe and the European Union can be a little challenging on occasion, but never impossible. The arrival of some books on Brexit did give me pause for thought, but I ended up admiring the pragmatism of a scheme that classed the enlargement of the European Union (KV 87) but was unable to envision the opposite.

Figure 6. Basement stack.

The books on Brexit, like other books that fit into tricky spaces, posed no real problem due to the flexible nature of the scheme and the scope to create numbers, though there is a little reluctance to deviate too much from the scheme in terms of our own classification-hacks. We're trying to strike a good balance where the scheme forms the solid foundation of how we're classifying and into what area we are classifying, but never to the detriment of the collection or how members interact with that collection. However, it is of vital importance that if someone were to take over the classification of the collection in the future they would be able to make sense of any deviations, and trace them back to their origins.

The way we classify needs to make sense to everyone interacting with the scheme we've put into place. At Middle Temple Library I've provided supporting materials for the team and encouraged conversation and questions about how we're using Moys. If library members are to query anyone about why a book is at a certain location, all staff should be well equipped to give a reasonably believable answer. In terms of preparing for the future, a classification policy is under way to set out how we're currently using Moys as well as where and why we've deviated from schedule suggestions, so anyone classifying in the future will come to the scheme ready to hit the ground running, much in the way I did when I started last year.

In terms of supporting members, we've produced small subject guides that allow them to make the connection between subject and number. We have shelf-marks to indicate where subjects begin (e.g., KN 10 Contracts, KM 500 Criminal Law), but other than that there is no glaring signage to shepherd members to shelves, and they seem to have acclimatised well regardless. Going forward there will be more done to make the scheme accessible, and some of this rests on how we carry out the final phase of the classification project, which is the reordering of our previous editions/superseded books.

The presently classified section is the tip of a very large iceberg that contains older textbooks and previous editions spread across two floors of our basement. This summer we are hoping to move the books occupying the ground floor of the basement. At rough count it looks like about 20,000 volumes will be shifted out of alphabetical arrangement and into subject order. For months I have been classifying the unclassified titles, and the entire team has been labelling the books with new classmarks in preparation for the move.

The move when it happens is unlikely to take a mere two and a half days like the previous one. We will be moving almost seven times more volumes (6.66 my calculator tells me, not like an omen at all), in extremely close quarters. Anyone who knows a library basement knows that the conditions there during summer are not going to be favourable, and moving books out of rolling stacks is going to result in at least one or two squashed members of the team. Of course, innovation sometimes demands sacrifice, and at the end of this project we will be rewarded with standardised ordering of all our textbooks. All that will then remain is for the team to erase the old shelf-marks from the catalogue records of books moved.

It could be said that it's not really necessary to extend the scheme to our previous editions as they are used differently to the current texts. However one of the things we've noticed after the Moyification of our main collection is that a lot more books are being taken from the shelves, and they are consistently removed in subject chunks. In a blog post I wrote for the Middle Temple Library blog, I spoke of witnessing a barrister bear-hug where a member had been seen sweeping an arm full of books in one go, taking entire portions of a subject. This was unlikely to happen under the previous arrangement as members were too busy going to A first for one book, and then a related book filed bays away at Z. Having the previous editions arranged into subject order will really open up their usefulness beyond the usual fraught descent into the basement in search of a single volume.

THE END (A CONCLUSION)

Every classification scheme has its drawbacks, which seems to be one of those eternal library truths. Moys is similar in that it is far from perfect, but it is near perfect for what Middle Temple Library needs at this time. It is a classification that deals specifically with the law, and is flexible and logical. I've mentioned some areas were tweaked where the scheme might not have felt comprehensive enough, but these tweaks are few and far between. Moys has actually provided substantial coverage for most of our textbooks and as barrister bear-hugs testify, the scheme is doing a good job of bringing books and their readers together.

Having perused earlier editions of Moys it's easy to see that there's been a lot of work done between the first and fifth edition, so I'm hopeful that a new edition, if and when it emerges, will similarly offer good expansion in as yet under-represented areas, and as I said, Moys is flexible enough that one can still classify materials into meaningful divisions with confidence.