Introduction: Sunrise at Sipaulovi, Second Mesa, Arizona

Just after 6:00 a.m., on a Saturday in July 2013, I found myself standing toe to talon with a large golden eagle (Aquila Chrysaetos canadensis). As is often the case in my trips to the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona, it was I who was out of place. I was visiting for the day, in the village of Sipaulovi on Second Mesa, there to celebrate the Hopi katsinam (ancestor spirits) as they performed their last dances of the year in what the Hopi call the Niman. The Niman marks the end of the Hopi ceremonial period during which the katsinam live among them, showering their beneficence on the people (with rain and the crops it brings) before returning to their homes some 120 miles away, at Nuvatukya'ovi (“Snow-on-top-of-it”), otherwise known as the San Francisco Peaks, located in the Coconino National Forest.

In truth, the eagle seemed to ignore me, as I was just one among the many other people, both Hopi and non-Hopi, who had gathered on and around his rooftop perch, the place where he had likely been living for much of the year. The Hopi call these eagles kwaahut (sg. kwaahu), but these eagles, which have been collected as nestlings by Hopi men at various sacred sites across northern Arizona, are given individual names by the families that care for them. I did not know the given name for this kwaahu, but clearly he had one, and it was quite possible that he too had come to this family from lands on or near Nuvatukya'ovi, the place to the katsinam would be traveling later that day.

I did not need to know this eagle's name to appreciate the importance he had for the family, and the Hopi in general (see also Fewkes Reference Fewkes1900). Thus I know from my (superficial) understanding of Hopi religious beliefs—and without claiming knowledge that, as a noninitiate, I am not entitled to know—that these eagles are considered clan ancestors, which explains why each of the several clans that constitute Hopi village communities only collect eaglets from their clan's specific collecting grounds. These collecting grounds are often on or near Hopi shrines and other landmarks (like the highest peak of Nuvatukya'ovi, the cardinal southwesterly direction marker for the Hopi) that trace the historic boundaries of Hopitutskwa—Hopi homeland. Indeed, Hopi often call shrines, ancestral archaeological sites, and sacred landmarks by the term itakuku (“our footprints”), marking as they do the vast territory covering much of the northeastern quarter of the state of Arizona, but also beyond, which the Hopi call “home.” Just as the English-language term “home” signifies a concept so much richer in affect and meaning than merely the physical space captured by the term “house” in English, so too does Hopitutskwa for the Hopi. Dotted as it is by the sacred places known by members of the various Hopi clans to be where their ancestors lived and traveled in the past, and thus where their contemporary religious obligations require them to go today, for eagles, but also for so much more—Hopitutskwa forms the essential contours not just of the space, but the very way of life, of being Hopi. It is a life and land that archaeologists believe have been intertwined in the fabric of being Hopi since at least the fourteenth century, but the Hopi say they have always been precisely who, and where, they are (Eggan Reference Eggan1950; James Reference James1974; Rushforth and Upham Reference Rushforth and Upham1992; Dongoske et al. Reference Dongoske, Ferguson and Jenkins1993,Reference Dongoske, Yeats, Anyon and Ferguson1997; Jenkins, Ferguson, and Dongoske Reference Jenkins, Ferguson and Dongoske1994; Clemmer Reference Clemmer1995; Whiteley Reference Whiteley2008).

If it were possible to compare the significance of different sites in the sacred Hopi landscape (though I am quite sure one cannot, at least from a Hopi perspective), few would be more significant than Nuvatukya'ovi, the mountains known in English as the San Francisco Peaks. As the highest peaks in all of Arizona, and one of the few places that regularly receives visible precipitation in this otherwise arid region, it is difficult to overstate their centrality to Hopi values, beliefs, and everyday life. Though its highest peak rises some ninety-five miles southwest of the current Hopi reservation, it is, on most days, clearly visible from their mesa-top villages. Indeed, as the cardinal marker for one of the five sacred Hopi directions, its visibility from the villages is critical not only because it delimits the southwesterly most part of Hopitutskwa, but is the direction that Hopi ceremonial leaders look to as they gauge the timing of certain parts of their annual ceremonial calendar. It is what all Hopi people, despite some differences in their particular clan histories and traditions, understand to be the home of the ancestor spirits, the katsinam, who come to visit them during the first half of the year. If the people have been acting humbly, thinking good thoughts, working hard, and performing their ceremonies properly, the katsinam will bring their gifts of rain, productive crops, and even new family members (both human and nonhuman) as they renew life in and across Hopitutskwa.

But this beneficence must go two ways. As much as the katsinam come to the homes of today's Hopi communities, just as they always have, so too must the Hopi never forget to visit the homes of the katsinam. Correct performance of the elaborate rituals, both esoteric and public, that make up Hopi ceremonial life, demands strict observance with protocols that include traveling to the shrines on and around Nuvatukya'ovi. Whether it is to collect eaglets, various kinds of spruce pine sprigs, or simply to give thanks at the shrines and landmarks they are required to pray at there—the significance of Nuvatukya'ovi not just to Hopi pasts, but to their current well-being and renewal—indeed to the whole of Hopi life—cannot be overstated. No surprise then that it has also been continuously attested to in the prehistorical, archival, and contemporary scientific record over many centuries (see, e.g., Hough Reference Hough1897,Reference Hough1898; Voth Reference Voth1912; Parsons Reference Parsons1936; Glowacka, Washburn, and Richland Reference Glowacka, Washburn and Richland2009).

But the Hopi I have more recently spoken to explain that pilgrimages to Nuvatukya'ovi, though no less imperative, have of late become especially dangerous. When I asked why, I was surprised to hear them tell of matters both legal and historical in nature. Despite the fact that Hopi and non-Hopi agree that Nuvatukya'ovi is within Hopi aboriginal territory (indeed, defines it), today it falls outside the Hopi Indian Reservation, and its 1.5 million acres (Whiteley Reference Whiteley1998). The nonreservation lands that make up the bulk of Hopitutskwa including Nuvatukya'ovi, but also much more, constitute a mix of public and private, federal, Arizona state, and Navajo tribal lands. Thus the risks to Hopi traveling across Hopitutskwa come from a dizzying array of federal, state, and tribal statutory restrictions that they have to navigate and, in some cases, preemptively challenge in courts across Arizona and even in Washington, DC.

This article considers the circumstances that make travel across off-reservation Hopitutskwa so difficult. As I will suggest, to the extent that much Hopi ceremonialism points to and demands attention to sacred spaces beyond the current Hopi Reservation, it puts Hopis in a precarious position, one that compels them to make terrible choices between observing their religion or breaking the law.

More specifically, I will attempt to trace the administrative wrangling that dispossessed the Hopi of Nuvatukya'ovi, now part of the Coconino National Forest, in 1908. I will then explain how, a century later, recent decisions by the USFS to allow a ski resort located there to use reclaimed wastewater for the purposes of making artificial snow is just the last in a long line of legally backed indignities perpetrated by the United States against the Hopi.

I will reflect on the particular value and insight afforded to the Hopi context by Bernadette Atuahene's provocative notion of “dignity takings” (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014). Atuahene's concept looks beyond the brute economics of state dispossession and remuneration of marginalized groups' property rights, and to those circumstances where “the expropriation of property is part of a larger strategy to dehumanize or infantilize a group” (2014, 164).

Atuahene's Dignity Takings as “Reminder”

To make her case for the notion of a “dignity taking,” Autuahene builds from a unique admixture of two arenas of legal scholarship that have recently begun to reconsider age-old questions of human worth in both metaphysical and material terms. On the one hand, in invoking the concept of “takings,” Atuahene engages with some of the hoariest questions of the rights of individuals to their material property and, in particular, those rights as they relate to the protection by, and against, exercises of state power. Coupling this with the notion of “dignity” invests concerns with state infringements of individual property rights with an increased attention to such rights as extend beyond economic considerations, and inhere, like “dignity” itself, “in the autonomy of self and self-worth that is reflected in every human being's right to individual self-determination … universal and uninfringeable by the state or private parties” (Glesney Reference Glesney2011, 67–68; see also Paust Reference Paust1984; Harris Reference Harris1997; Reáume 2002; Castiglione Reference Castiglione2008).

These considerations trace their origins in Euro-American thought back to the classical liberalism of European political philosophy of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most famously in the writings of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, John Stuart Mill, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. These thinkers, informed by the rising market logics of the time, and with Renaissance notions of man as uniquely ennobled with God-given powers of reason and free will, argued that the only way political systems and their laws could claim legitimacy over their subjects was if those over whom they governed freely and rationally agreed to be constrained by those systems. Importantly, this individual liberty, understood as it was to inhere in individuals' rights to determine how best to ensure the satisfaction of their basic physical and spiritual needs, was often understood as the rights of individuals to pursue, acquire, and then secure private property.

For Locke especially, securing an individual's rights to property was the sine qua non of legitimate state formations, and the only justifiable explanation for why a naturally free individual would rationally submit to state power was if it involved a trade of some of that freedom for greater protection of his or her property interests. Indeed, to the extent that the unique place of humans in the great chain of being was understood by these thinkers (and Pico Della Miranda, Descartes, Pufednorf, and others before them) to be grounded on the dignity afforded humans to their freedom and rationality, the primary way in which political formations could ensure that dignity was through the protection of rights to property (Barak Reference Barak and Kayros2015). From this perspective, a state taking of property can also be understood as always, necessarily, an infringement on individual rights to self-determination—that is, as a taking of the individual's dignity. By giving voice to this sometimes forgotten dimension of liberal political theory, and especially its application to the complexities of today's global legal orders, Atuahene's notion of “dignity takings” offers legal scholars that which Ludwig Wittgenstein famously understood to be the most important work of the philosopher, namely, that “the work of the philosopher consists in assembling reminders for a particular purpose” (Wittgenstein 1959).

To provide us with this reminder, Atuahene turns to relational theories of property law (Radin 1982; Rose 2000; Singer 2006). In so doing, she deploys the way this work turns over conventional theories of property and property law as concerned with the rights of people to their things, and instead argues that property is ultimately about the relationships between people vis-à-vis their things. Tacking this way, Atuahene extends these theories to suggest that when and how property rights are summarily denied to certain classes of subjects, the effect is not just a loss of monetary value but, even more fundamentally, an indignity.

Given that much classic liberal political theory at once understands the state as justified by its capacity to protect individual property rights but also “considered non-whites to be a savage separate species who did not have the capacity to reason” (2014, 32), Atuahene finds it unsurprising that colonial agents who embraced these theories also “justified Europe's domination and authority over [nonwhites]” (32) through a taking of their property. Moreover, such indignities are in full view, in the “speeches of state agents, official documents, oral histories or archival records”—by which those dispossessions were undertaken and papered over (2014, 34).

As Atuahene rightly notes, and has been well described by many, the circumstances surrounding Native American dispossession of nearly 80 percent of their aboriginal lands at the hands of US settler colonial regimes make up an undeniably horrific, violent, and tragic record of indigenous genocide and ethnocide (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson1988; Byrd Reference Byrd2011). As Atuahene convincingly argues, “dignity takings” like these are extraordinary precisely because they have lasting effect beyond the economic loss of value suffered by their victims, one grounded as much in their dehumanization as in their dispossession. The state taking of property—especially land—of those it deems incapable of holding it underwrites a kind of violence whose “significant emotional consequences” (2014, 29) have ramifications across history. For these reasons their redress through monetary compensation alone remains unsatisfying, and helps explain why many, such as the Lakota, refuse it outright (Ostler Reference Ostler2010).

In what follows, I will show how the conditions described by Atuahene as constitutive of dignity takings are on full display in the Hopis' ongoing efforts to stop the development of Nuvatukya'ovi. I will try to give a sense of the ongoing indignities Hopi are suffering as a result of their dispossession of these lands and will show how, at different moments in the history of the present, federal actors addressing Hopi claims to aboriginal title in the lands within and around Nuvatukya'ovi sometimes appreciate and sometimes ignore Hopi perspectives on their relationships to these lands. In conclusion, I will argue how, even though Atuahene's notion of a “dignity taking” is an apt description for many aspects of the Hopi's experiences with US misappropriation of their lands, there are certain important ways in which the remedy she suggests, “dignity restoration,” which involves the reintegration of victims of dignity takings into full membership in the state, may not quite take full measure of the problems, or the possible responses, that these injuries pose for the Hopi and other Native American nations.

For what cannot be ignored is that, despite Native American individuals being granted citizenship in 1924 (Indian Citizenship Act, 43 U.S. Stats. At Large, Ch, 233, 253, [1924]), Native American nations have always claimed a political autonomy separate and distinct from the larger US polity that surrounds them.

For Hopi, then, dignity restoration requires something other than a return to a civil society that they have never entirely embraced. I propose instead taking seriously native nations' views of their inherent sovereignty, a sovereignty recognized in principles of Native American and US federal law, which is that tribes are “domestic dependent nations” that have “an unquestioned right to the occupancy of their lands they occupy, until that right be extinguished by a voluntary cession to our government” (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 US [5 Peters] 1, 17 [1831]). I will suggest that what we may be called on to consider for Native American nations is that the circumstances of their indignities demand not so much a need “to rehabilitate the dispossessed and reintegrate them into the fabric of society” (2014, 14), but a strengthening and emboldening of their claims and rights to their sovereignty. Their dignity, I will argue, is to be found in precisely the place they have always insisted it is—in their (self-)determination.

The Hopi, their Lands, and their Dignity

As can probably be imagined, the Niman ceremony I attended that day in 2013 marks one of the most important days in the Hopi ceremonial calendar. It is occasioned not just by leave-takings, but also by joyous reunions around bountiful feasts, which, as the day goes on, are impressive for the spectacular coordination of material, symbolic, and natural phenomena that constitute the ceremony and its effects. By day's end, the crowds of friends and family who have come to the Niman have swollen the village population, and so has the sky. What starts as a cloudless cobalt expanse becomes a cottoned field of billowing clouds, some pregnant with rain, others already sporting the long curtains of gentle showers approaching the Hopi villages across the desert valleys. For the Hopi, these clouds are the katsinam themselves, and the kwaahut too, providing for their children like they always have, and reminding everyone there why the Hopi call this not just their homeland, or their religion, but their Hopivewat, their way of life.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Hopitutskwa, or aboriginal homelands, to the Hopi people. As one of the few contemporary Native American nations to have never been relocated from their aboriginal lands, the importance of the region of what is now northeastern Arizona and parts of western New Mexico that the Hopi have always called home are regularly described both in the past, and now, as central not only to their past, but to their present, and future. This is evident in the stories about the origins of the Hopi people, which have been regularly told both to me, and are also found in the many volumes of scholarly ink spilled on the Hopi since the nineteenth century (for good reviews of the relevant literatures, see Laird Reference Laird1977; Whiteley Reference Whiteley1998).

In general outline, as it was told to me, the story goes that when the ancestors of the Hopi people came into this, the fourth world, they emerged from a hole in the ground, the Sipaponi, or navel, located near the confluence of the Little Colorado River and the Colorado on the eastern end of what Hopi call Öngtupqa, or the Grand Canyon. They came to escape the corruption that had made their lives unbearable in the world below, the third world, but only after sending several emissaries up to this world to see what, or who, was here. When below, the Hopi recall hearing footsteps above them, and so they suspected someone, or something, was living in the world above them, and they were desperate to escape the wickedness that had befallen them. After three failed attempts, on the fourth, an emissary successfully made it through the hole and discovered that, indeed, a being was living there, Maasaw, the mysterious keeper of this world. After securing his permission, the ancestors of the Hopi climbed up through the Sipaponi to meet Maasaw.

Upon their arrival, Maasaw presented the people with three ears of corn, two long beautiful ears and one rather short and stubby one. Maasaw then invited the people to step forward and select an ear, each one representative of the life they will lead in this fourth world. The first two to step forward took the long beautiful ears, and they were each sent off to find the fertile lands, far away, that could support such bountiful growth. Those people, my friends told me, were the ancestors of the Navajo and European peoples who would make their way to, and find easy lifestyles in, their faraway homelands. When all he had left was the short, stubby corn, Maasaw turned to the people who remained and explained to them that though this was a very plain ear, it was hardy, and meant to endure the sun-parched, arid lands of the plateau deserts right where they now found themselves. He then handed these people a simple planting stick, and the small ear, and explained to them that though they too had to first go away to travel across the lands, each going their separate ways, eventually they would all come back, and it was here that they were destined to make their homes and live the humble, hard way of life that was promised to them.

It is these people, these hisatsinom, who are the ancestors of the Hopi. It is these people, and their descendants, whose history is evidenced in the thousands of shrines, archaeological sites, and sacred spaces that mark the places where they traveled in the centuries before their return to the lands promised them by Maasaw, areas on and around the mesa tops they currently occupy. But these places, many of which mark the boundaries of Hopitutskwa itself, are important not just as markers of history. For from the Hopi perspective there really is no difference between their history and their destiny. For these shrines, sites, and sacred spaces are also the places where, during those migrations, different groups of people would acquire sacred knowledge (navoti, or tradition), given to them by different beings whose names they would later take as their clan names (e.g., Hoonaw, Honani, Kyaaru, Kwaahu or Bear, Badger, Parrot, Eagle, respectively) and are critical to them in performing ceremonies necessary to living a good and bountiful life. This knowledge, and the ceremonies by which it is enacted, were what the different Hopi clans had to acquire on their migrations to make life livable back on the lands promised them by Maasaw. It was these ceremonies that each clan had to perform before being admitted by the other clans to join the village communities of which they are now a part, and by which they are entitled to farm certain lands set aside for them. And it is these ceremonies, many of which require the return to the shrines, sites, and spaces across Hopitutskwa, that form the respective parts of the year-long ceremonial cycle that, ideally, each Hopi clan continues to play a part in to this day. A Hopi advocate I once heard arguing before the Hopi tribal court perhaps put it best, showing the intertwining of Hopi life and land to the norms governing Hopi life both past and present, sacred and secular, in ways that defy easy separation. As she said: “You can't separate Hopi and religion and land, language, court, constitution. It's all tied up into one” (see Richland 2009).

And so what I was witnessing on that day in Sipaulovi was a synchronizing of nature and culture, physical forces and spiritual meanings, all of which come together in a totalizing sense of Hopi life on Hopi land. Indeed, the crescendo offered up on that day was very much like the ones I had seen in years before, and always to equally spectacular effect. When the sun rays and soaring clouds combine to cast a pink and purple hue across the sky, and the dusky covers of rain bring the desert smells before them, they remind one of not only the vibrant colored blues, yellows, reds, and whites of the plumed and garbed katsinam dancing alongside them, but also of the multicolored faces of the small children, chasing each other around the village, bearing all the treacle-sweet traces of the snow cones and popcorn balls that they had been eating over the day.

And yet, on that day in Sipaulovi, there were other palls gathering too, ones that threatened the good things that the Hopi people associate with summer rains. The threat that seemed most acute on that day involved the very place—Nuvatukya'ovi—the San Francisco Peaks—to which the katsinam would return just as they always do (see Figure 1).

1 Nuvatukya'ovi, as seen from Fort Valley. Photo taken on 3-24-10 by Brady Smith. Courtesy of the USDA Forest Service.

Earlier that year, a decades-long fight led by the Hopi (with other tribal nations) against a ski resort on the western slopes of Nuvatukya'ovi's highest peak had reached its lowest point. In what may be the most outrageous affront in the ongoing battle, the resort, which operates pursuant to a forty-year permit on US forest lands, had begun to make artificial snow on the mountain, using reclaimed wastewater pumped up from Flagstaff.

Consider this for a moment. In the desert environment that has always shaped and constrained Hopi life, there are few places like the San Francisco Peaks. It is one of the few locations where water is in visible abundance year round and, at a peak elevation of nearly 12,400 feet, is the highest point in all of Arizona. It is the place that Hopi hold as a key source for much-needed rain to their fields, where the average rainfall measures only 5–15” per annum (Annual Climate Statistics, Hopi Tribal Department of Natural Resources, March 5, 2012).

This is the place that the owners and operators of the Arizona Snow Bowl had sought and for which had won US Forest Service approval to spray frozen reclaimed wastewater for the purposes of expanding and enhancing skiing and snowboarding opportunities at their resort. Environmental impacts aside, the ski resort operators were almost literally pissing on Hopi sacred ground (see Figure 2).

2 Images of Snow Made Using Reclaimed Wastewater at Arizona Snow Bowl. From “Discolored Slopes Mar Debut of Snow-Making Effort,” by Leslie MacMillian. Originally published on January 11, 2013 6:02 p.m., New York Times, Green Blog. http://green.blogs.nytimes.com (accessed March 2, 2015).

It is the effects of this particular indignity that had not just physically tainted the mountain and its life-giving waters, but threatened almost everything and everyone that had gathered to celebrate Hopi life on that day in Sipaulovi, and every other day in Hopiland (Glowacka, Washburn, and Richland Reference Glowacka, Washburn and Richland2009).

How did this happen? How is it that the Hopi, who have occupied their current homelands since at least the fourteenth century (e.g., Whiteley Reference Whiteley1998; Ferguson, Berlin, and Kuwanwisiwma Reference Ferguson, Berlin, Kuwanwisiwma, Snead, Erikson and Darling2009; Kuwanwisiwma and Ferguson Reference Kuwanwisiwma and Ferguson2009), find themselves violated with the desecration of one of their most sacred mountains, and with dirty snow? To understand this requires a tracing of the history of land possession in the region, and how, in the case of the Hopi, Nuvatukya'ovi may very well have been taken without the Hopi ever having the chance to object, at least initially.

The Shaky Legal Ground of Hopi Land Dispossessions

Writing in 1879 to his superior in Washington, DC, W. H. Mateer, the federal agent assigned by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to the Hopi tribe, was clearly frustrated by his inability to deal with the small group of white settlers who had set up homesteads in a place the Hopi call Múnqapi. Mateer reported a visit from some Hopi leaders complaining that their farming lands had been taken over by the newcomers, and were thus asking the Agent to have them removed.

Mateer writes to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, E. A. Hyat, to determine “whether there is not some law by which the Indians could be protected in their rights to lands, which they have cultivated for a century or more” (Letter of W. H. Mateer to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, E. A. Hayt, 1 May 1879).

Hyat's reply is not encouraging. “As the Moqui [Hopi] Indians occupy public lands without any authority of law, the provisions of the statutes enacted by Congress for the protection of Indians in their occupancy of lands within a reservation, cannot be invoked to protect the Moquis, and remove and punish White settlers” (Letter of Commissioner Ezra A. Hayt to W. H. Mateer, 14 August 1879). Despite the fact that the Hopi were never relocated from their aboriginal lands—Mateer's comment at least acknowledges their use rights as preceding those of the Americans who, as we shall see, took legal control over the area from Mexico in 1848—the Commissioner nonetheless determines that the Hopi have no legal right to the lands that can be protected by the United States. Hyat does, however, ask Mateer to provide him with some dimensions of a possible reservation that the Hopi would need to survive (Letter of Commissioner Ezra A. Hayt to W. H. Mateer, 14 August 1879). And while Mateer initiates the process, it is not until 1881 that any official action is taken. By then, J. H. Fleming is the Agent, and the Hopi complaints regarding settler encroachment have persisted. Fleming's complaint, however, is different. He argues that a reservation is needed not to protect Hopi land rights, but so that he can do his job. In his letter to then Commissioner Hiram Price, he explains that because of a particular white settler who the “[Hopi] seem to regard … as a bigger man than the Agent,” the Hopi had started ignoring several BIA mandates, especially those requiring they send their children to boarding school in Albuquerque (Letter of J. H. Flemming to H. S. Price, 11 November 1882). Fleming also sends along proposed coordinates for the reservation boundaries, demarcating a rectangle that follows the 109th and 108th longitude verticals and the 35th to 36th latitude horizontals.

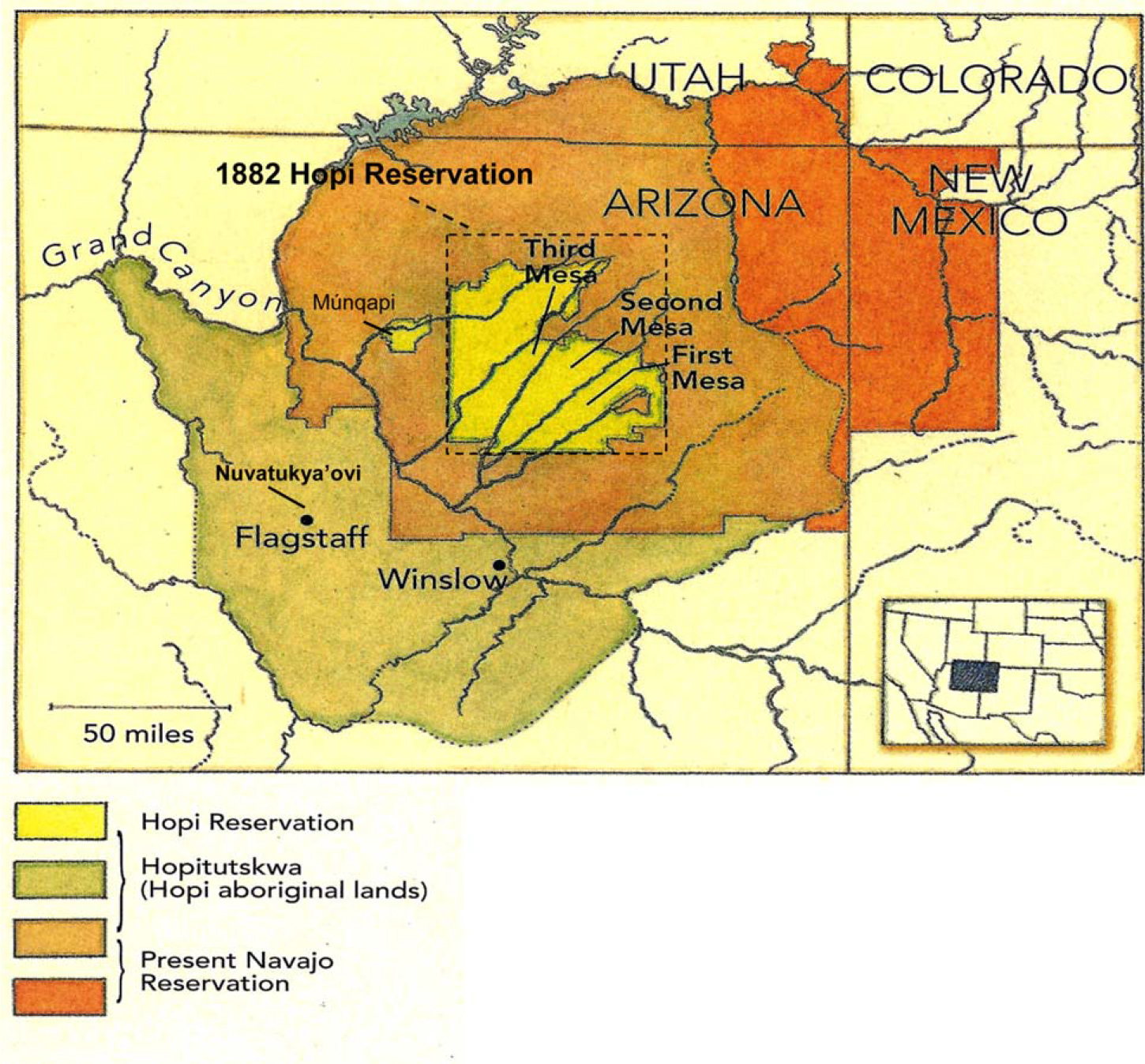

With these coordinates in hand, Commissioner Price writes to Secretary of Interior, H. M. Teller, recommending the “withdrawing the lands indicated … from white settlement” (Letter of Commissioner Price to Secretary Teller, 13 December 1882). Three days later, on December 16, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur issues an executive order creating a reservation “set apart for the use and occupancy of the Moqui [Hopi], and such other Indians the secretary of the Interior may see fit to settle thereon” (Moqui Reserve, Executive Order of President Chester A. Arthur, 16 December 1882). Significantly, the dimensions for the reservation and the 2,477,780 acres it sets aside follow exactly the coordinates proposed by Fleming (see Figure 3).

3 Map of Hopi Lands Over the Years. Adapted by author from a map prepared by Peter M. Whiteley and Patricia J. Wynne (2004). Map provided courtesy of Patricia J. Wynne.

And so a Hopi reservation was made, largely for the stated needs of federal agents, rather than the Hopi themselves. This may explain why the original 1882 boundaries, shown in dashed lines in Figure 3, make a perfect rectangle, rather than following Hopi logics of place, space, or aboriginal claim—Hopitutskwa. Indeed, one need only notice that the area around the village of Múnqapi, the area that Agent Mateer originally wanted protected, lies well outside the 1882 boundaries.

Since that time, the boundaries of the Hopi reservation have been redrawn several times by federal action, adding some lands—including the area around Múnqapi—but more often with the effect of shrinking it to the current size of 1.5 million acres (as shown in Figure 3). Either way, and in comparison to the nearly 15 million acres that the Hopi claim as Hopitutskwa, the creation of a Hopi reservation had the effect of drastically reducing the amount of land that the Hopi could claim as theirs.

Or did it?

It is generally recognized that the century-long period from the Indian Removal Act of 1830 to the Dawes Severalty (or Allotment) Act (1887–1934) effectuated the greatest dispossession of Indian lands in US history, and often in the name of safeguarding the Indians' best interests. Of course, before this time, nothing like fee simple ownership was ever recognized as inhering in Indian tribes' property claims to their aboriginal lands. This had been established law in the United States as early as 1823, when Chief Justice Marshall issued his decision in Johnson v. M'Intosh, 21 US (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823), which, along with Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 US (5 Peters) 1,(1831) and Worcester v. Georgia, 31 US 515 (1832), are considered the founding pillars of federal Indian law. In Johnson, a case that considers whether US citizens could purchase lands from Indian tribes, the Court held that the United States, by its victory over England in the Revolutionary War, had succeeded to absolute title in the lands in North America that the British Crown acquired through conquest. As such, tribal nations do not have the power to alienate tribal lands.

Marshall bases his reasoning on a principle often referred to as the “Doctrine of Discovery,” which recognizes the title of those European nations that have claimed to discover and/or conquer, and colonize, foreign lands. However, Marshall explains, this “title by conquest” found its limits in the Indian tribes, largely because they refused either to “be blended with the conquerors or safely governed as a distinct people” (21 US 543, 589 [1823]). Holding themselves apart, “as savages whose occupation was war and whose subsistence was drawn from the forest,” meant that “a new rule” had to be devised, one providing that “the Indian inhabitants are to be considered … occupants, to be protected … in the possession of their lands, but to be deemed incapable of transferring the absolute title to others” (id. at 592). Such was and is the nature of aboriginal title in the United States. It is a right, acknowledged by US law, which accrues to Indian tribes both as sovereigns and as “savages.” That is, their aboriginal right of occupancy, however constrained, is nonetheless a right that stems both from a sovereignty that preexists the Constitution, but also because they refuse, either out of irrationality or inhumanity, to voluntarily yield their sovereignty up to the nation that claims its superiority over them. Although this is a right not of absolute ownership, but merely of occupancy, it is still a right to which tribal nations are entitled and one that is to be protected by their “guardian,” the federal government (id. at 592).

At least that is the theory and the law, as it is appears in writing. The practice and implementation of these rules and policies have been uneven, at best. By the end of the nineteenth century, even the idea of an aboriginal right of occupancy came under threat. In Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 503 (1903), the Supreme Court found it had no authority to review congressional acts, like the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, even though the Act had vitiated prior treaties with tribes regarding their occupancy rights to lands, like those of the Kiowa in this case, to which they had been removed and were reserved for their exclusive use. This is true because the Act was not a dissolution of their rights and interests, says the Court, but “was … a mere change in the form of investment of Indian tribal property” (187 U.S. 503, 556 [1904]). Backed by decisions like these, actions administered under the removal, reservation, and allotment eras of federal Indian policy regularly forced Indian tribes to accept substantially smaller, poorer quality lands than those to which they had aboriginal title (Prucha Reference Prucha1986; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson1988).

The Hopi were never removed from their aboriginal territory, nor was their territory or reservation ever substantially allotted, as was the case with the Kiowas in Lone Wolf. And while the reservation delimited an area of land much smaller than their aboriginal territory, it does not seem to be the case that the effect of creating the reservation was intended by federal agents to extinguish Hopi rights of occupancy and use of those other lands that fell outside of it.

But, arguably, the injustices committed here against the Hopi are even worse. Recall that Hyat's letter to Matter suggests that the Hopi were already held by the Commission of Indian Affairs to “occupy public land without authority of law” (Letter of E. A. Hayt to W. H. Matter, 14 August 1879). How could this be? How was it that the Hopi did not have aboriginal title in Hopitutskwa before the creation of the reservation? What had happened to the “right of occupancy” that, under Johnson v. M'Intosh, they were entitled not only to enjoy but also have protected?

In pursuing these matters, it remains unclear, at least to this researcher, how the Commissioner of Indian Affairs legally determined that the Hopi “occupy public lands.” What is evident is that, to the extent to which this determination was used as an explanation for the inability of federal agents to protect the Hopi in their lands, it was at least understood by them (including President Arthur himself) that the Hopi had no legal right under US law, even of occupancy, in the lands that they had always called their home.

Meanwhile … the Creation of the Coconino National Forest

Other actions by the federal government during this same period confirm the sense that its agents seem unconcerned with Hopi aboriginal title to lands off of their reservation. Chief among these is the 1898 Executive Proclamation, made by President William McKinley at the suggestion of Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of Forestry (and a towering figure in conservation) to create the San Francisco Mountains Forest Reserve.

When the San Francisco Mountain Reserve was made by President McKinley, it was done pursuant to the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 (26 Stats. 1095 [March 3, 1891]), but the Forest Reserve Act did not provide for any management of those lands. That came six years later, with the Forest Service Organic Administration Act of 1897. It is this legislation that stands to this day as the foundational document establishing the US Forest Service and that delegates to the federal executive branch the power “to improve and protect the forest within the reservation … for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States” (16 U.S.C. § 475). Thus, within a year of the creation of the US Forest Service, President McKinley sets aside the San Francisco Mountain Reserve out of the “public lands” in the area. Later, the San Francisco Reserve would be joined with lands from other nearby reserves to create a single, consolidated Coconino National Forest (Proclamation of President T. Roosevelt, 2 July 1908).

Significant again is the fact that the lands taken into this reserve were presumed to be public lands, despite the fact that Nuvatukya'ovi rests at their very heart. And while the creation of the Forest was not an uncontroversial act—large landowners around Flagstaff and Williams contested it (Letter, Sec. of Interior to the House re: San Francisco Mountains, 10 March 1906)—there is no mention, anywhere, of any Native American claims to the lands, or concerns regarding its use and occupancy. Even today, Hopi religious practitioners are required under federal law to obtain special use permits from the USFS any time they want to collect ceremonial materials or, sometimes, to even visit the shrines and landmarks that mark the land as aboriginally theirs (see, e.g., Forest Service Manual Chapter 2360, Heritage Program Management, 2367 Permitting). And though they are not the same, it is more than a little ironic that just as the Hopi need USFS permits to undertake their sacred obligations to Nuvatukya'ovi, it is also pursuant to USFS permits that reclaimed wastewater is now being used to make and blow artificial snow on its western slopes.

The Indignities of Skiing and Snowmaking in “Snow-on-top-of-it”

Skiing in Nuvatukya'ovi

Not long after its creation, recreational uses of the lands within the Coconino National Forest would run alongside the conservation and economic activities for which it was originally created. Records indicate that as early as the 1930s, skiers were taking a portable rope tow up to the area known as Hart Prairie, midway up Mt. Humphries Peak, to access the snowy slopes of its western-facing bowl. At the time, local USFS managers allowed use of a small cabin located on the prairie as their base lodge. In 1935, a dirt road was built by Civilian Conservation Corps, and the USFS then built a bigger lodge to accommodate the larger crowds. After purchasing the operation in 1956, the Arnal Corporation built a second lodge, extended the road, and, in 1958, talked the USFS into permitting their plan to install a permanent ski lift. A second was added in 1962, and by the early 1970s, the resort now known as the Arizona Snowbowl was in full swing. At no time during this history is there any evidence to suggest that the Hopi were consulted regarding their aboriginal claims to the lands being developed, either by the USFS or the operators of the Snowbowl itself, despite its location on the western slopes of Nuvatukya'ovi (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2011).

Arizona Snowbowl and the Save the Peaks Protests

The impetus for Hopi involvement in the Arizona Snowbowl development came in the early 1970s when its new owner, Summit Properties, Inc., petitioned the USFS to have the area around the resort rezoned for mixed recreational, commercial, and residential use. It then announced its plans to expand the resort's operation to include condominiums and a commercial “ski village” development.

It was during Summit's simultaneous efforts to lobby the Coconino County Board of Supervisors to approve the development plans that some of the earliest evidence of Hopi opposition to the Snowbowl appear in the record. In a public hearing held on April 27, 1974 in Flagstaff, Hopi tribal members presented testimony objecting to the requested development permit (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2011).

In one exchange, the chairman of the board attempted to explain the board's position regarding Hopi and Navajo beliefs and commitments concerning the Peaks. Addressing Robert Lomadofkie, a Hopi tribal member, he said: “We don't want the elders or the traditionalists to think that everybody is opposed to their religious beliefs” (Reporter's Transcript, 27 April 1974, p. 259). Lomadofkie responds: “We respect your rights to worship in the way that you do. … So, we understand that you do not put us down, although that is what we have heard plenty of today” (ibid). Despite some support, Hopi and other tribal objections to the development plan were ultimately passed over when the board's majority voted to approve Summit's development plans.

The Hopi and their fellow antidevelopment advocates kept up the pressure, however, holding out hope that the USFS, which had not yet approved the master plan, would be more amenable to tribal claims. Meanwhile, the chorus of objections swelled. In subsequent public hearings, as well as through letters to the editor in various local, regional, and national media outlets, tribal opposition to Summit's plans was joined by the voices of non-Indians concerned about the negative effects—environmental, cultural, and otherwise—that development might cause. Benefits, protests, and other public events were regularly staged in nearby Flagstaff, all of which featured express concerns for protecting the sacredness and dignity of Native American beliefs as they related to the Peaks (see Figure 4).

4 Flyer for the Save the Peaks Benefit Concert, February 23, 1974. Image reproduced with permission from the NAU Special Collections (Call Number: nm59g000s004b001f0023i001p001). Accessed online March 2, 2015.

For its part, the Hopi Tribe also took its complaints to Washington, DC. In an August 1978 meeting with Senator Barry Goldwater, representatives of the Hopi Tribe explained the indignities they would suffer should the USFS approve the plans to develop Nuvatukya'ovi. Despite his pro-business reputation, Goldwater seemed to get the message. In a series of letters written in 1978 to the Forest Service head, Arizona's Governor, and President Jimmy Carter, Sen. Goldwater personally conveyed his support for the Hopi position, and even recommended the Peaks be given a legal designation that would offer them “perpetual protection” (Letter of B. Goldwater to Superintendent J. McGuire, 9 August 1978). In his letter to John McGuire, Chief Superintendent of the Forest Service, Goldwater writes, “I think the time has come to make it abundantly clear to commercial interests in Arizona that the forest lands of the Peaks are lands that will never be taken away from the religious concept of the Hopi” (ibid).

These appeals fell on deaf ears. On February 27, 1979, the USFS issued its decision, approving part of the master plan to expand the Arizona Snowbowl Resort. The plan, which the USFS Supervisor labeled a “compromise,” permitted the planned expansion of the ski resort lift operation and lodges, including the building of three new lifts, the clear cutting of fifty additional acres of forest land, and the paving and widening of the Snowbowl road (Wilson v. Block, 708 F.2d 735 [1983]).

The Hopi and their allies appealed through the USFS appeals process, but on December 31, 1980, the Chief Forester upheld permitting the plan. In March 1981, the Hopi filed suit against the USFS in federal court in Washington, DC and were joined in the suit by the Navajo Medicine Men's Association, local residents, and other activist groups (Wilson v. Block, 708 F.2d 735 [1983]).

Importantly, the grounds for the suit were not, as they were on other fronts, that the USFS had violated their claims to aboriginal use and occupancy of the lands. Instead, they argued that the USFS permit of the Snowbowl development violated the sanctity and dignity of their religious beliefs, and in so doing infringed on their First Amendment rights to free exercise of their religion. The litigation on these matters would stretch out over the next thirty years, and two separate suits. The Hopi and their co-petitioners lost in the first round of litigation, and appealed to the DC Circuit Court in 1983.

In his opinion in that case, Judge J. Edward Lumbard pointed to a long line of case law to explain that the free exercise clause of the First Amendment does not proscribe government burdens on religion “unless the challenged action serves a compelling governmental interest that cannot be achieved in a less restrictive manner” (Wilson v. Block, 708 F.2d 735, 740 [1983]). As a result, governmental actions must not just offend religious believers or even casts doubt on their beliefs, but actively “penalize faith, to run afoul of the First Amendment” (ibid).

While Lumbard found evidence sufficient “to establish the indispensability of the Peaks” to their religion, he also found that the Hopi had not proven that they were prevented or penalized in their efforts to enter the sites to be developed. Thus he found that that USFS had not imposed an “impermissible burden” on Hopi religion when it permitted the Snowbowl development plan, and affirmed the lower court's decision in favor of the USFS.

The Hopi would come back to federal court in 2005 to once again challenge the actions taken by the USFS regarding a second plan for development of Arizona Snowbowl. The occasion this time was the Forest Supervisor's approval of the Snowbowl's plans to augment the natural snowfall on Nuvatukya'ovi with artificial snowmaking using reclaimed wastewater pumped up the mountain from nearby Flagstaff.

This time, the Hopi and their lawyers felt they had a stronger case than in 1981. They believed they had new federal laws that would work in their favor. In 1993, Congress passed the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act (RFRA) (42 U.S.C.§ 2000(bb)(b)1), intending by it to require the federal government to show a “compelling interest” whenever it imposes a “substantial burden” on someone's free exercise of religion, and to show how such imposition is by the “least restrictive” means available (ibid).

After losing again, in Arizona District Court this time, the Hopi and their allies appealed to the Ninth Circuit. This time their arguments seemed to gain some traction. In writing for the three-judge panel, Judge William Fletcher held that through RFRA, Congress had intended to substantially expand the free exercise protections far beyond what the lower court held (Navajo Nation v. U.S. Forest Service, 479 F.3d 1024, 1033 [2007]). Fletcher explained that RFRA redefines the exercise of religion in ways that do not require protected beliefs be “compelled by … a system of religious belief” (ibid). A burden on religion is thus “substantial” where it would “undermine their entire system of belief and the associated practices of song, worship, and prayer that depend on the purity of the Peaks” (ibid). For these and other reasons, the panel reversed the decision of the district court, casting doubt on the validity of USFS approval of the snowmaking plans.

The Hopi tribe and their co-petitioners and allies were right to celebrate this victory. It stood as the closest thing to a true “win” that the Hopi have experienced in their long battle to protect Nuvatukya'ovi.

Alas, the victory was short-lived. In response to the panel's judgment, the ski resort and the US government petitioned the Ninth Circuit to rehear the case by a full panel of eleven judges and, in October 2007, the petition was granted (Navajo Nation et al. v. USFS, 535 F.3d 1058 [2008]).

After a hearing held just two months later, the court ruled 10–1 to reject Fletcher's analysis and reinstated the judgment below in favor of the USFS. The majority opinion held that even though RFRA had expanded the kinds of religious practices that cannot be substantially burdened by government actions, it did not change the kinds of burdens that would be considered substantial. The court thus held that while the proposed snowmaking may violate the Hopis' religious beliefs, “the diminishment of spiritual fulfillment—serious though it may be—is not a ‘substantial burden’ on the free exercise of religion” even as defined in RFRA (id. at 1070). Once again, then, the Hopi found themselves and their religious integrity and dignity on losing side of their battle to protect Nuvatukya'ovi.

Conclusion: Dignity as Self-Determination

In recounting this history of the various indignities suffered by the Hopi at the hands of US settler colonialism, I have attempted to identify the many ways in which Atuahene's concept of “dignity takings” resonates with the circumstances and lived experiences of their repeated losses of aboriginal territory. From the summary conclusions by federal agents in the 1880s that the Hopi “occupy public lands without authority of law,” what is set in motion is a series of legal acts—from executive proclamations to administrative decisions to legal orders—that together constitute the gravest of indignities that Hopi people continue to face to this very day. Moreover, this dispossession and indignity is accomplished by the kind of regulatory sleight of hand—a callous erasure of Hopi rights to their aboriginal lands as something that always already happened and thus could never have been addressed head on. How could Hopis have imagined, in the 1870s, that by complaining to Agent Mateer of white settler encroachment on their farm lands, they had somehow set in motion the conditions for determining their aboriginal claims as already lost. Nor could they have anticipated that the creation of the 1882 reservation would or could be taken by federal agents as defining them out of their aboriginal claims to use and occupy lands beyond its borders. And thus they could not have known that this would also make Nuvatukya'ovi public lands, susceptible to reservation as a National Forest, upon which Euro-American rights to use would be given priority over their ceremonial obligations and religious observances in the area. Above all, they could not have possibly imagined that this would result in having the sacred place they call “Snow-on-top-of-it”—the place where their life-giving rains, clouds, and katsinam come from—suffer the gravest indignity of having frozen wastewater blown over its peaks.

To the extent to which Atuahene's notion of “dignity takings” points up the ongoing social and emotional consequences of land dispossessions that dehumanize and infantilize—as surely federal agents and their acts did and continue to do to the Hopi—the concept aids understanding how the disparate acts and omissions of the federal government form a pattern of ongoing indignity and dispossession to which Hopi object. Indeed, without Atuahene's concept, and its invitation to consider the larger fields of meaning that suture together these otherwise piecemeal erasures of aboriginal claims to land, we risk losing sight of the suffering that native peoples like the Hopi continue to endure in the present. We also naturalize the logics of settler colonial dispossession themselves that work precisely by arguing that native claims are illegitimate because they were not originally raised, or consistently pressed, over the course of this history. Instead, the concept of “dignity takings” allows us to see just how this partiality is itself a tactic in undermining and overwriting aboriginal rights, like those that the Hopi nonetheless continue to press to Nuvatukya'ovi, and other parts of their Hopitutskwa.

At the same time, there are ways in which US dispossessions and indignities against the Hopi and other Native American nations are different than the “dignity takings” that Atuahene describes in the South African context. For native nations in the United States cannot be understood as having entered into anything like a social contract with the settler colonial regimes of the United States and other Euro-Americans before them. The consequences of this are, I think, important for understanding the consequences that might attend efforts at remedying the harms suffered by such indignities.

First, insofar as this story reveals how, over the nearly 150-year history of their engagements with the US settler colonial regime, the Hopi have ceaselessly persisted in their dignity (religious or otherwise) as a people, a culture, and a nation with aboriginal claims to the sacred spaces and places they call Hopitutskwa, it is a story not just of the ravages of US colonialism, but equally of Hopi ceaseless insistence and exercise of their sovereignty and self-determination.

This is true precisely because the history of Hopi engagement with the United States does not include a moment when the meetings between the two nations were taken, by federal agents, as meetings between equally free peoples who mutually constrain themselves to the rules of their polity in exchange for greater protections to their respective property rights. And there has never been a treaty between the United States and Hopi of the sort that both defined, and was often defied by, subsequent relations between the United States and other tribal nations.

As such, we are hard pressed to explain a Hopi expectation that the United States would secure them in their property as grounded in anything like a social contract. Which means, following Atuahene's model of the dignity taking, that when their land was misappropriated by the United States—as it surely was—we cannot then presume that what the Hopi would ever want as recompense for their injuries (and indignities) would be to join in some sort of shared polity with the United States. Thus what Atuahene advocates as a proper response to the harms of the dignity takings she studied in South Africa—something she calls “dignity restoration” and that involves the harmed groups being reinstated as full members of the social polity that had oppressed them—may not make sense for redressing Hopi indignities and dispossessions suffered at the hands of US agents.

Instead, what the Hopi have, then, to turn to when demanding the right to their dignity is nothing neither more nor less than their sovereign right to self-determination. This quality of being in the possession of and persisting in their rights to self-determination and sovereignty, on their own terms, is arguably the very meaning of human dignity as a human right that applies to nations like the Hopi (Rosen Reference Rosen2012). And when the Hopi are able to persist in their demands to aboriginal title when their property rights were not recognized by the United States in the first place, when they were dehumanized either because of or in justification for the misappropriation and misrecognition their land, we see that they nonetheless can and do persist in pressing their land claims. That is, the Hopi, across this history, show themselves, repeatedly, to act with and command the self-determination that constitutes not just their unextinguished claim to use and occupy their aboriginal lands, but the very dignity and humanity that such a claim underwrites, even when the lands are no longer in their possession.

What remains undeniable is the injustice and indignities that the Hopi faced and continue to face at the hands of US settler colonialism. What is also undeniable is the ongoing and ceaseless demand that Hopi make, in the name of their sovereignty, to define the terms of their own dignity, as part of the woof and weave that makes up their life, on their land. To that end, Atuahene's concept reminds us of the demands that dignity can and should make on us all.