Introduction

Maria O. is a retired teacher in the city of Timişoara, Romania, who has been busy reclaiming her family's nationalized house since 1996 through seven different lawsuits, ultimately reaching the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Through archival research, I found out that Maria's family had contested the nationalization of their house from the moment of its taking in 1950, and that three petitions against nationalization, filed by different members of the family in 1953, 1960, and 1962, were found legitimate by the nationalization commission (none was ultimately successful). Yet Maria was not aware that hers was only the last step in a half-century-long quest to reclaim the nationalized house.

Her story is not unique, but merely an illustration of a trend begun with the nationalization itself, more than half a century ago, by owners contesting the taking of their houses by the communist regime. Post-1989, the Romanian government has estimated that over 2 million claims have been submitted by former owners and their heirs under various restitution laws, totaling 21 billion euros to cover the claims (Case of Maria Atanasiu and Others v. Romania Reference Waldron2010). The housing restitution process in Romania continues more than two decades after the fall of communism.

Post-1945, property was at the center of two radical regime changes: first, from a liberal capitalist system that prized private property above all else to a communist system that attempted to eliminate it and reconceptualize property itself; second, post-1989, from a partially successful communist system to a neoliberal one that protects private property and privileges market logic.

Prior to 1945, the expropriation of Romania's Jewish population was a hallmark of the wartime fascist regime of Ion Antonescu (1940–1944) that spearheaded the Holocaust in Romania. Jewish owners experienced multiple waves of expropriation: during the war, followed by formal but delayed and incomplete reparatory measures post-1945, then distinct immigration waves to Israel that also entailed loss of property, as well as nationalization and expropriation connected to the transition to communism (see Friling, Ioanid, and Ionescu Reference Friling, Ioanid and Ionescu2004; Rotman Reference Rotman2004, 61–65). The fascist regime did not attempt to dismantle private property as an institution and system of values, and focused on property theft from Jews as well as other groups (e.g., Roma), but there are important continuities from a property rights consciousness, which were apparent in my interviews and that are captured in this article.

In this context, Maria's case and others like it raise interesting questions about the vitality of the former owners' private property claims across radical property regime changes. What is the meaning of their property rights consciousness, and how is rights consciousness related to particular historical and institutional traditions of rights (does it make a difference that property rights are at stake, and specifically property rights related to homes)? How is rights consciousness related to various meanings of rights as law, practices, and discourses (Merry et al. Reference Merry, Levitt, Rosen and Yoon2010)? More broadly, how should one understand the role, meaning, purpose, limitations, and constraints of rights, the expectations placed on them across regime changes, and the wrongs they are meant to address (McCann Reference McCann2014; Merry Reference Merry2014; Nelken Reference Nelken2014)? Finally, to the extent that significant continuities between precommunist, communist, and postcommunist property rights consciousness can be identified, what do they say about the extent to which the state shapes rights consciousness (separately from legal consciousness) and legal culture more broadly and, ultimately, the relationship between rights and the state?

In this article, I focus on postcommunist property regulation, discourses, and rights consciousness in the field of housing restitution post-1989. I argue that property rights consciousness is only partially an outcome of state power, that it is surprisingly indifferent to radical regime changes, and that it is a distinct category from legal consciousness. Rights consciousness goes beyond formal rights and litigation, and encompasses awareness of rights broadly defined, as well as the capacity and willingness to mobilize rights. Decentering the state does not mean that the state has no role in the emergence of rights consciousness or rights mobilization. It does, however, help identify competing rights claims with different origins and expectations, including competing forms of rights consciousness forged under different regimes (such as communism and precommunism). Decentering the state, formal law, and rights illuminates how living law is itself constituted under conditions of regime change, and how rights function in an authoritarian regime or other regimes with high levels of both rights cynicism and rights mobilization. It also sheds light on the constitutive dynamic between individual and state property practices and discourses, and on the construction of complex legal cultures of property.

After introducing the site of the research, the next section of the article discusses the distinction between legal and rights consciousness and the importance of this distinction. This is followed by a section that focuses on the historicity of property rights consciousness in Romania, specifically the communist housing nationalization process. The following section discusses the state as a source of rights consciousness in postcommunism. I next zoom in on the housing restitution process as a source of rights consciousness, and on the state as a pivot in the conceptualization and mobilization of rights. The last two sections explore separately variations in legal and rights consciousness for former owners and their heirs, tenants of nationalized housing, and their lawyers.

The article is based on extensive document and archival research, as well as twenty-five interviews with former owners, tenants, and lawyers representing both owners and tenants, that I conducted in the city of Timişoara, Romania starting in 2007 (I followed up in subsequent years). The archival documents are from the Timişoara branch of the National Archives of Romania (187 files in fourteen collections) and cover the nationalization process at the local level. I also examined legislation, current case files on restitution, textbooks, academic and media articles, and court decisions of the time and post-1989.Footnote 1 (Unless otherwise noted, all translations from Romanian are mine.)

The City of Timişoara

Timişoara is the largest city of the Banat region in Romania, which is located at the western tip of the country, bordering Hungary and Serbia. Timişoara is the seat of Timiş County, which changed boundaries during the communist regime multiple times. Timişoara's history dates to Roman times. Throughout medieval times and modernity, the city has been successively ruled by the Hungarian kingdom, the Ottoman Empire, the Habsburgs, Hungary (itself part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire), and finally Romania after the end of World War I. Timişoara was also the starting point of the 1989 Revolution against the communist regime (see generally Munteanu and Munteanu Reference Munteanu and Munteanu2002).

The region's population historically included more than twenty-one ethnic groups (Munteanu and Munteanu Reference Munteanu and Munteanu2002; Neumann Reference Neumann2013, 396). The main groups in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were ethnic Germans, Hungarians, Romanians, Serbs, and Jews. During the 1930s and up to World War II, the county's population was approximately 600,000, out of which about 40 percent were ethnic Romanians, 30 percent ethnic Germans, and 15 percent ethnic Hungarians. The other 15 percent included Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Jews, Roma, Ukrainians, Russians, and Turks (Munteanu and Munteanu Reference Munteanu and Munteanu2002, 150; National Institute of Statistics 2002). While the official censuses attempted to fix nationalities, for much of the region's history boundaries among them were quite fluid, as most ethnic groups spoke more than one language, one's nationality did not necessarily coincide with one's mother tongue, and mixed marriages were common (Neumann Reference Neumann2013, 398–400).

In 1938, Timişoara had 101,951 inhabitants, was the seventh largest city in Romania, and had a population that was 26 percent Romanian, 30 percent Hungarian, 30 percent German, and 8 percent Jewish (Munteanu and Munteanu Reference Munteanu and Munteanu2002, 150). During World War II and its immediate aftermath, the city and surrounding region saw a slight increase in the overall population and some changes in percentages. The Jewish population increased after the Hitler-Stalin pact and the subsequent wave of refugees, with the vast majority concentrated in the cities of Timişoara and Arad (Federation of Jewish Communities of Romania 1993, 74–94).

The Hungarian and German minorities saw decreases in numbers, in large part because of postwar transitional justice measures (although not primarily relocations as seen in other parts of Europe). Ethnic Germans from the region (Schwab) were deported to reconstruct the USSR (Mioc Reference Mioc2007, 130), while ethnic Romanians from parts of Romania seized by the USSR after the war were relocated throughout the country, including in Banat.

Throughout the communist regime, the city's population grew steadily to over 300,000, and became increasingly dominated by ethnic Romanians (who make up 81 percent of the country according to the 2011 census), while Jewish and German inhabitants emigrated en masse. As the ethnic makeup of the city and country changed, so did the ownership of housing and its restitution post-1989.

Legal Consciousness and Rights Consciousness

Most law and society literature on legal consciousness does not directly focus on the distinction between legal and rights consciousness, although that distinction is often implicitly assumed. Rights consciousness overall is folded into broader discussions of legal consciousness and both are treated as separate but adjacent regions of the legal ideology-hegemony-consciousness triangle (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991; Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Silbey Reference Silbey2005). From a critical perspective, rights consciousness as a category of legal consciousness plays a key role in explaining legal hegemony (Silbey Reference Silbey2005).

I understand legal consciousness as a dynamic, constitutive process, a type of social practice encompassing individuals' recursive engagement with the law in all its manifestations—institutions, norms, processes, meanings, categories, boundaries, and the like (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991; Merry Reference Merry1990; Silbey Reference Silbey2005; Şerban Reference Şerban2014). The value added of the concept of legal consciousness, despite its vagueness (whose legal consciousness, what is the content?), has been to open up very productive areas of inquiry into how people engage with and mobilize the law, how they relate to it (resist, subvert, accept), and how these complex relationships with the formal legal system, broadly understood, help create meanings, identities, and subjectivities (see Merry Reference Merry1990; Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Engel and Munger Reference Engel and Frank2003; Silbey Reference Silbey2005). More recent scholarship has examined variations in legal consciousness among different groups of people (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2004; Abrego Reference Abrego2011), and some of this scholarship has directly or indirectly also studied how people engage with and mobilize rights.

The legal consciousness literature responds in some way to the challenge posed by Scheingold that the willingness to turn to law in the United States is significantly shaped by the “myth of rights,” which includes faith in the nexus of rights-litigation-social change and in the symbolic power of rights (Scheingold Reference Scheingold2004). Rights and (state, formal) law, in this framework, are thus inextricably linked, and the struggles to understand whether and how rights deliver on their promises have until recently been approached within a liberal legal tradition.

Rights Consciousness

Three types of challenges have recently been pushing toward a more clearly defined approach to rights consciousness. The first one is the global nature of rights, which includes how rights travel and translate in multiple locales (Merry Reference Merry2006), the normative pluralism of rights and hybrid rights constructions (Osanloo Reference Osanloo2009), and the limits of rights (Engel Reference Engel2012). The second is the simultaneous deployment of multiple meanings of rights as formal legal rights, international human rights, values, and practices (Merry et al. Reference Merry, Levitt, Rosen and Yoon2010), while the third is comparative approaches to rights consciousness (Li Reference Li2009, arguing that in China there is no rights consciousness but, instead, rule consciousness that follows historical patterns and supports, not subverts or challenges authoritarian rule).

The 2013 Law and Society Association presidential address and the responses to it directly address these developments. Michael McCann's hopeful address sketches four paradoxes of rights—which rights claims count, the “contradictory promise of individual freedom,” who can assert rights, and “rights as a potential resource for social justice”—and highlights key contributions to rights research from a global and comparative perspective (McCann Reference McCann2014, 245–74). David Nelken focuses on the destructive potential of rights, the dilemmas, tensions, contradictions, constraints, and limits of rights, and asks “why rights regimes claim to be better than what came before—injustice does not deserve defending just because it is hallowed by tradition” (2014, 277). Finally, Sally Merry examines both “the potential and the failure of rights: their promises of freedom, recognition, and social justice along with their limitations, exclusions, and burdens on the rights holder” (2014, 285).

The disillusion with rights and the questions and challenges raised by both the old and the new rights agendas take a distinct shape in a postcommunist context rife with rights skepticism, yet also witness to significant rights-based legal mobilization. For communist legal regimes, (some) rights were just words on paper, promises without delivery. The post-1989 period saw the establishment and growth of constitutional courts, the explosion of rights-based litigation before the ECHR, and the expansion of infrastructure and resources for domestic judicial systems. Tellingly, since its establishment in 1959, almost half the judgments delivered by the ECHR concerned only five member states, three of them from postcommunist Eastern Europe (the Russian Federation, Poland, and Romania) (ECHR 2013). For Romania, property is one of the top areas of litigation before the ECHR.

Across the board, we see citizens who are willing to defend their rights and challenge their state, each side mobilizing different understandings of rights before supranational actors, who rule and thereby privilege particular understandings of rights over others. In fields as complex as property restitution, multiple actors—former owners, tenants/new owners, state actors, and the ECHR—have distinct understandings, expectations, and goals for property rights, and rights draw no clear line of demarcation between submitting to or resisting the state. In short, there are variations in property rights consciousness, and rights consciousness emerges as a distinct category from overall legal consciousness.

In this article, I focus on (property) rights consciousness as conceptually distinct from legal consciousness. I understand rights consciousness as a recursive, fluid, evolving social practice and discourse centered on claims, expectations that are broader than formal rights awareness and mobilization through courts that draws from multiple sources (everything from ideologies to state policies), is not bound by formal state law, is anchored in different interpretive contexts, and signals distinct identities. I am interested in how individuals and groups conceive of and engage with rights, how various meanings of rights play out in rights practices (including how rights are created through practices), how various actors mobilize the symbolic value of rights and sources of rights consciousness, and how conflicting rights claims shape rights consciousness.

This is broader than “rights consciousness as a greater willingness by an aggrieved individual or group to make a claim for redress on the basis of a ‘right’” (Lorentzen and Scoggins Reference Lorentzen and Scoggins2015, 4), as it encompasses the realm of rights consciousness beyond courts and litigation (Engel and Munger 2003). It is also broader than a definition of rights consciousness as awareness of existing rights, willingness to assert rights, and the understanding of social relations in terms of rights (defined as individual claims against the state) (Li Reference Li2009, 11–12). I am interested in the construction of rights consciousness that includes rights as values and practices, which may or may not dovetail with formal rights enshrined in law. Property rights consciousness refers specifically to practices and discourses related to property, so a key source includes various property ideologies.

Understanding rights consciousness distinctly from legal consciousness captures multiple dimensions of rights that do not easily fit within the classic liberal legal paradigm, and in particular the three types of challenges identified above. Crucially, it repositions the state vis-à-vis rights, which in turn allows for a clearer understanding of the contexts in which individuals conflate law and rights, the multiple, often conflicting sources and meanings of rights, and the implications for rights mobilization in both local and global settings. If legal consciousness encompasses individuals' recursive engagement with the law in all its manifestations, rights consciousness zooms in on claims and expectations that are mediated through law, but explicitly reach beyond formal, positive law. There is significant overlap between legal and rights consciousness, but also key differences: looking through the lens of rights consciousness decenters the state in novel ways (compared to legal pluralism debates, for example), and exposes how rights are overtly reconstructed below and above the state.

Property Rights Consciousness

Property rights consciousness, and specifically consciousness of rights over homes, is an excellent site for studying rights consciousness for three reasons: the resilience of private property, the centrality of private property rights, and the distinctive nature of housing.

The first is private property's resilience across radical (property) regime changes, and specifically of ownership over housing. The goal of communist regimes, Romania included, was to dismantle the institution and concept of private property, initially through massive expropriations and the nationalization of land, industry, commerce, and housing. Housing was different from all other takings, however, because it had a much narrower scope (only involving approximately 30 percent of all housing in the country; see Chelcea Reference Chelcea2004, 1, 112; Dawidson Reference Dawidson2004, 125), it lacked finality (some restitutions took place and some of the seized housing was sold back to the population), and the regime allowed and even encouraged at times the construction of private housing (Şerban Reference Şerban2015), thus sending mixed messages about the importance of private property.

The second is the archetypal nature of property rights for all other rights in modernity, in particular in terms of the key values underpinning private property that are also central to the modern rights discourse: individual freedom, autonomy, personhood/agency, and power, the latter understood both in a relational sense and as self-mastery (MacPherson Reference MacPherson1962; Radin Reference Radin1982; Waldron Reference Verdery2004). The third is the special nature of housing as homes with emotional and cultural value, and separately as assets, again across regime changes.

Private property's resilience over time illuminates the longitudinal construction of rights consciousness and the archetypal nature of private property rights provides a baseline for understanding the broader category of rights consciousness, while the special nature of housing indicates various sources of rights consciousness.

The research for this article suggests that the state is only one source of property rights consciousness, and thus that rights consciousness should be decoupled from the state. State policies are a potential source of rights consciousness and a pivot in how rights are deployed. In Romania, former owners before the ECHR, for example, attempt to reconceptualize rights as against the state and others/tenants, and the state is a pivot in a network of rights cutting across power/resistance lines. State agents mobilize their own understandings of rights and protect, restrict, channel, or privilege different meanings of rights. “The state” is not a single external actor imposing a coherent rights regime from above, even in the area of property. Everyone has rights consciousness and mobilizes rights, including state actors, building on distinct property ideologies or policy priorities.

Sources for property rights consciousness include not just (changing) state laws, but also value systems and ideologies (coexisting, plural, occasionally overlapping or competing, both about property and about justice), history, identity, practices (such as lengthy processes of nationalization-contestation-restitution), supranational actors (such as the ECHR), and expectations of what rights can deliver.Footnote 2 For restitution, expectations for rights center as much on restitution of actual housing or compensation, as on history and identity (as Liviu Chelcea pointed out, genealogy and restitution are a collective process and genealogical practice).

The Historicity of Property Rights Consciousness

The year 1989 was a key turning point in the history of Romania, but it was by no means a complete watershed. There was no clear switch between a pre-1989 “property vacuum” and a post-1989 neoliberal property universe (Verdery 2003) but, instead, intertwined key legal, institutional, and ideological continuities and ruptures. The communist policy makers attempted to eliminate private property, but they also continued to build on precommunist legal concepts and ideologies of property, which resulted in a hybrid legal culture of property—ideologies, legal consciousness, and rights consciousness.

Romania is a civil law jurisdiction, heavily influenced historically by the French legal tradition. Between 1864 and 2011 (thus covering precommunism, communism, and postcommunism), property was regulated by the 1864 Civil Code, which was primarily inspired by the Napoleonic Code (other sources were the Italian Civil Code and Belgian law) (Hamangiu, Rosetti-Bălănescu, and Băicoianu Reference Hamangiu, Rosetti-Bălănescu and Băicoianu2002, I:22–23). Article 480 of the Romanian Civil Code (1864) defined property as “the right of someone to enjoy and dispose of a thing [lucru] exclusively and absolutely, but within the limits set by law.” In both legal theory and practice, property was supreme, absolute, and exclusive, and its limitations were exceptional and temporary, amending without fundamentally changing the property paradigm itself.

The top Romanian jurists from the interwar period explicitly linked private property to its Roman predecessor, and praised it for its “simple, practical and modern” character. They embraced a rather absolutist conception of private property, and regarded it as a universal concept and institution (Hamangiu, Rosetti-Bălănescu, and Băicoianu Reference Hamangiu, Rosetti-Bălănescu and Băicoianu2002, II:4–8). Legally, ideologically, and institutionally, property in precommunist Romania was an unexceptional capitalist example, closely resembling its Western European models. It incorporated the Roman conception of ownership as a power relationship that was all-embracing and at the center of civil law relationships and obligations, and embodied the property ideologies of individualism, personhood, and power.

Private Property in Communist Romania

Romania's transition to communism began in 1945, after World War II, and private property in particular seemed to be in free fall. Two continuities and two major ruptures are important here.Footnote 3 First, the Romanian Civil Code of 1864 was never abolished, even though it was heavily amended, and the sections on movables, immovable, and property rights remained largely intact.Footnote 4 The legal map and main attributes of property did not fundamentally change from precommunist days, but were adapted for socialist purposes. The communist property hierarchy was different—state, collective, and, lastly, personal property, but ownership was still the pinnacle right among all other property rights.Footnote 5

Second, there were fundamental ideological continuities between precommunist and communist official understandings of property, including the centrality of property, property as power, and labor as a legitimating value. Labor in particular has been the ideological linchpin between precommunist, communist, and postcommunist concepts of property. As in the Soviet Union, labor was the essence of the socialist narrative of property: the opposite of exploitation, reward, and effective guarantee for claiming rights such as housing and social security.

The three communist constitutions of Romania, from 1948, 1952, and 1965, signal the transition from private property based on exploitation—to be eliminated, to personal property based on labor—to be protected, with labor as a bulwark against exploitation. Communist lawmakers and legal scholars distinguished private property from personal property in large part based on the distinction between labor and exploitation (Fekete Reference Fekete1954), but the distinction is specious to the extent that personal property maintained key characteristics of private property and is thus best understood as a subtype of private property (narrower in scope, but not essentially different).

Personal property continued to be regulated by the same civil code provisions as private property in all its aspects (Article 480 of the 1864 Civil Code). Labor was the key ideological and moral value at the core of personal property, which provided continuity with bourgeois ideas of property, particularly Lockean theories—property as an incentive for labor (exemplified by the socialist principle of repartition according to work), and personality theories—the end result of ownership was the socialist person who fully participated in civic life. As such, the narrow scope of personal property dovetailed with a rather puritanical concept of socialist personhood that revolved around needs, avoiding exploitation, and being a responsible owner. Unsurprisingly, labor is a key constitutive value of property rights consciousness for both former owners and tenants post-1989.

The major ruptures between the property regimes of precommunism and communism are the extensive restrictions on private property and the exceptionalism of state property. The four main communist restrictions of private property were significant. First, the communist regime undertook extensive takings, primarily nationalization and expropriation. Second, the scope of private property was narrow, as it included only the home and household objects, objects of personal use, some land, income, and savings. Third, there were numerous regulatory restrictions on the circulation of property, as well as building and demolishing houses. Inheritance was protected in principle, however. Fourth, housing policies were perhaps the most significant restriction, for example, the lack of freedom of contract in the rental market.

From a legal and rights consciousness perspective, continuities and changes in the legal regime of property were reflected in the legal education of the tightly controlled labor market. There were only three law schools in the entire country, and they graduated very small numbers of legal professionals (the entering classes for all three for full-time study dwindled to about 200 overall by the late 1980s, in a country of approximately 20 million). Property law was taught as a “marriage of convenience.” The lawyers I interviewed, all of whom were trained before 1989 and are still active, were told that “there was a bourgeois point of view, and a socialist one, and regarding property, we are on the way to socialist property, but in the meantime we tolerate other forms of property, including private property, for the promotion of the interests of the individual.” Property law was then taught based on the 1864 Civil Code—the baseline, with socialist amendments as exceptions.

These continuities and changes indicate that early communism is not a story of the disappearance of private property, or about socialism creating truly new forms of ordering property relations. Rather, this is about mutual adaptation: property adapting to socialism and socialism adapting to private property, and about the conflicting property messages, ideologies, and practices embedded and constituted in law. The result was a hybrid concept of private property, drawing from both capitalist and socialist sources, which in turn contributed to the creation of new, hybrid forms of legal and property rights consciousness (Şerban Reference Şerban2014). Nowhere is this process more clearly illustrated than in the housing nationalization process of the 1950s.

Urban Housing Nationalization and Legal and Property Rights Consciousness

Nationalization of urban housing in Romania lasted for years and took place both directly, through Decree 92/1950, and indirectly for houses attached to nationalized businesses, industries, or land. It encompassed preparations for the takings, the issuing of various decrees, implementation and restitution instructions throughout the years, and dealing with claims against the takings. The focus here is only on Decree 92/1950, the emblematic legal act of urban housing nationalization in Romania. Urban housing nationalization was a process that lasted from 1950 until at least 1965,Footnote 6 was shrouded in secrecy, lack of transparency, arbitrariness, and ambiguity, and saw significant push back from the nationalized owners (Şerban Reference Şerban2010).

Decree 92 nationalized the houses and apartments of manufacturers, bankers, businessmen, and other elements of the high bourgeoisie, landlords, hotel owners, and others like them, but excluded from nationalization housing that belonged to workers, civil servants, small craftsmen, intellectuals by profession, and retirees (Article 2). The appendices to the decree listed alphabetically (by owner's name in each town and city) the nationalized buildings. Decree 92 nationalized between 120,000 and 140,000 residential units in the entire country, approximately a quarter of privately owned houses (Chelcea Reference Chelcea2004, 1, 112; Dawidson Reference Dawidson2004, 125; Stan Reference Stan2006). For Timişoara, Decree 92 listed 1,022 owners in its appendix (but buildings not listed were also de facto nationalized). Timişoara had a slightly higher nationalization rate than the rest of the country's big cities—35 percent versus 25 percent (smaller cities and towns had smaller nationalization rates) (Chelcea Reference Chelcea2004, 19–20), a large number of the nationalized owners were ethnically German, Jewish, or Hungarian, and most of the nationalized owners were not primarily landlords and can be more accurately classified as middle and even lower-middle class (Şerban Reference Şerban2010, Reference Şerban2014). Jewish owners who recovered their property after 1945 almost immediately lost it again under housing nationalization.

Decree 92 did not include any mechanism for challenging the nationalization. Despite this, however, half the nationalized owners in Timişoara contested the taking, often multiple times, both through administrative and court channels, and the process of petitioning and answering the petitions lasted for years (from 1950 to at least 1965) (Şerban Reference Şerban2010). Most petitioners considered themselves exempt from nationalization under Article 2 of Decree 92, and went to great lengths to prove that the house had been obtained through labor, not exploitation, that its primary function was as a family home and not as rental income (exploitation), and furthermore that others in a similar position had not been nationalized.

Petitioners commonly deployed two key discourses during this period: labor, and rights and justice (both mirrored in post-1989 restitution claims). Petitioners referred to their own labor and the labor of their forebears, and to the house as their home and the embodiment of family. These are efforts to contextualize and historicize the nationalization and to counter the regime's own discourse of houses as means of exploitation and assets. Labor represented a common ground between the petitioners and the socialist regime, as both considered it a legitimate fountain of private property rights.

Petitioners also brought up both rights claims and justice claims—claims that they were wronged, that the taking was not right, not just, but a “screaming injustice” [nedreptate strigătoare].Footnote 7 The petitioners' understanding of what was just and right was rooted in natural law and was entirely at odds with the local authorities' understanding, for whom justice meant class justice (and former owners were exploiters) (Şerban Reference Şerban2010, Reference Şerban2014).

Most petitioners complained administratively, as well as in court, but this was not a linear process and the court was rarely the last resort. Initially, local administrative bodies approved for restitution almost 20 percent of the nationalized housing. This decision was revisited multiple times over the subsequent years, but ultimately less than 1 percent of housing nationalized under Decree 92 in the whole country was returned to its owners.Footnote 8 In Timişoara, only 5 percent of petitions were ultimately admitted.

This brief genealogy of property (including nationalization) highlights that both law and property were sites of contestation characterized by hybridity and plurality from the very beginning of the communist regime. It is important to note here that petitioners clearly distinguished between legal consciousness and rights consciousness. Former owners engaged with the regime did not openly challenge the law or its legitimacy, but its interpretation and application in their particular cases. They attempted to capture socialist law for their own purposes, saw it alternatively as a resource to be harnessed or a potential objective arbiter, as well as a link with the past and internalized ideas of self, property, and legality (Şerban Reference Şerban2014).

From a rights consciousness perspective, dispossessed owners primarily mobilized conceptions of property rights rooted in labor, the civil code, natural rights, and as the price for obedience, overall an absolutist conception of property rights as embedded in precommunist property law. While time did not stand still between the 1960s and 1990s, there are some strong continuities with the postcommunist housing restitution process.

The State and Private Property in Postcommunism

If housing nationalization did not manage to dethrone private property and in many ways reinforced its centrality, other policy developments during the 1950s–1980s further contributed to the muted survival of private property ideologies and consciousness. The Romanian communist regime did not have a coherent and consistent policy regarding houses, even allowing for some restitutions during communism, as well as encouraging new private constructions of housing as early as the 1950s (Şerban Reference Şerban2015). In 1989, 63 percent of homes in urban areas were privately owned, while home ownership in rural areas was almost entirely private (97 percent) (Dawidson Reference Dawidson2004, 124).

The postcommunist state, like the communist one, has been somewhat ambivalent about housing and various types of rights related to housing. The state overall does not embrace a single, coherent property ideology, but vacillates between an absolutist, formalist, neoliberal concept, and an operative, pragmatic, context and policy-driven understanding of private property and property rights (see Underkuffler Reference Underkuffler2003).

Officially, private property returned with a vengeance in postcommunism: a main goal of the postcommunist transition has been the break up of state ownership (expropriating the state), and the shift from socialist legality—law with an explicit class character, to Western legality—the rule of law. The right to private property is an important centerpiece of the neoliberal agenda, and the extent and impact of Eastern European property changes have been widely studied (Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991; Frydman and Rapaczynski Reference Frydman and Rapaczynski1994; Hann Reference Hann2000; Verdery 2003).

The 1991 Romanian Constitution establishes a fairly absolutist conception of property. It discusses only two types of property—public and private—guarantees the inviolability of private property, forbids nationalization, and bans expropriation except on grounds of public utility, established according to the law, and against just compensation paid in advance. The Constitution protects the right to inheritance, bans confiscations, and establishes a constitutional presumption in favor of the legitimate acquisition of property. It also allows foreigners to acquire property in the country, with exceptions pertaining to acquisition of land (Article 44).

Owners dispossessed by the communist regime have generally promoted an absolutist, formal, title-based concept of property. Yet postcommunist restitutions are not necessarily grounded in this idea of property (for an overview, see Ciobanu Reference Ciobanu2013, 46–47). Restitutions can indeed embody an understanding of property rights as natural rights (Elster Reference Elster2004; Csongor Reference Csongor2009), and when undertaken in tandem with privatization, they can also balance the needs of reparation—backward looking—and reform—forward looking (Teitel Reference Teitel2000; Karadjova Reference Karadjova2004). This seems to point to a different conception of property rights embedded in various restitution efforts—fewer natural rights, and more open, fluid, and flexible rights. Finally, restitutions have symbolic, moral, and cultural importance, as they promote reconciliation and trust in the new democratic governments, acknowledge victims' dignity and suffering, and clarify group rights (Kritz Reference Kritz1995; Barkan Reference Barkan2000).

Romania, like other postcommunist states, embraced restitution's multiple, contradictory goals: restoration, reparation, de-communization, (re)establishing the sanctity of capitalist private property, and reinforcing a new rule of law regime. This also means a less absolutist, more operative concept of private property. The Constitution protects it, but also provides that private property rights can be limited, and that the right of property is balanced by duties, such as environmental protection (Articles 44 and 136). This concept of property is clearly visible in restitution policies that are more fluid, grounded in historical change, in the need to arbitrate between different societal interests, and reasonably attentive to the embeddedness of property in communities (Underkuffler Reference Underkuffler2003, 48, 59).

This conception is overall supported by Romania's Constitutional Court, and follows the Strasbourg Court's understanding of property rights (Sporrong and Lonnroth v. Sweden 1982). Most recently, in 2014, the court rejected a constitutional amendment aiming to eliminate constitutional provisions referring to limitations on the right to property because it would have amounted to an absolutization of the right to property (Decision 80/February 16, 2014).

In sum, neither the communist nor the postcommunist state was quite as extreme in its respective position as it might first appear. The communist state officially disdained private property, while quietly allowing significant private property in housing. The postcommunist state officially embraced private property wholeheartedly, while allowing for sufficient flexibility to balance various competing interests and continuing a strong public property regime. Various laws and policies, as well as institutional actors, created a wide enough ideological grid that positioned the state as a source of rights consciousness for widely different property claims.

Postcommunist Housing Restitutions and Property Rights Consciousness

Post-1989, housing restitution quickly became a central item on the de-communization agenda. To this day, however, it remains unfinished business. The Romanian state has not, for example, prioritized the restitution of Jewish property seized during the Holocaust or by the communist regime, and has only very recently passed a statute specifically addressing this issue (Law 103/May 2016). Like nationalization, the property question in postcommunist Romania turned out to be a lengthy and complex process, characterized by ambiguity and arbitrariness, if not secrecy. Restitution pitted former owners against socialist tenants/new owners, the state, and various vested interests throughout the bureaucracy and the new economy. Crucially, former owners mobilized supranational agents, primarily the ECHR, in support of their property claims. Claims of historical justice were countered by claims of efficiency, the needs of the market economy, and ensuring the stability of the housing market. The legislative framework of housing restitution and the implementation of restitution measures are awash in political indecision, confusion, overlapping rights, abuse at central and local levels, multiple judicial practices, and inconsistency (Romanian Academic Society [SAR] 2008).

A basic overview of the restitution landscape post-1989 includes: Law 18/1991 regulating land and restitution of land, Law 112/1995 on nationalized houses, Law 54/1998 regulating the circulation of land, Emergency Ordinance 83/1999 regulating the restitution of buildings that belonged to ethnic minorities, Law 1/2000 on the reconstitution of property rights over agricultural land and forests, Emergency Ordinance 94/2000 on the restitution of religious buildings, Law 10/2001 on restitution of buildings, Law 247/2005 on reforming property and justice, and Law 165/2013 finalizing housing restitution. All these pieces of legislation have been amended a number of times, and are implemented through a plethora of governmental decrees and local ordinances.Footnote 9

The State as a Source of Legal and Property Rights Consciousness

The first step in the housing restitution debate came early on in 1990, with Decree-Law 61/1990, which allowed 3 million state tenants to buy the state-owned and state-built apartments they occupied at very good prices (Stan Reference Stan2006). (The number sold in Timişoara is over 50,000 housing units [Timişoara City Hall 2008, 11].) This included tenants who occupied nationalized buildings. Among them were members of the new elites across the political and economic spectrum, who had either lived there before 1989 or moved in right after (under five-year rental contracts, with the possibility of renewal; see Stan Reference Stan2006, 188–90).

Many owners of nationalized buildings initiated restitution claims in court as early as 1990, including all of my interviewees in Timişoara. The number of court decisions throughout the country is estimated in the thousands (see also Stan Reference Stan2006, 191). Courts responded, for the most part, in favor of former owners and ordered the eviction of tenants.Footnote 10 The government, meanwhile, wanted a statutory solution, while major political figures such as the president of the country at the time (Ion Iliescu) publicly criticized restitutions and the courts for resolving these types of cases, and asked for the nonimplementation of court decisions in favor of former owners.

The Supreme Court obliged in 1995 when it banned lower courts from hearing cases before the adoption of the restitution statute. Moreover, the Prosecutor General began to use the recurs in anulare (annulment appeal) to overturn final court decisions (Stan Reference Stan2006). This practice was intensely criticized locally and internationally and was finally abandoned in 2008 under EU and ECHR pressure (SAR 2008).

It was only in 1995, after five years of bitter debates, that parliament managed to reach some consensus over housing restitution and compensation. The result, Law 112/1995, limited natural restitution (the house/apartment itself) to cases where the houses or apartments were either vacant or occupied by the original owners, and allowed the tenants to buy their housing, again at good prices. The 1995 statute also allowed tenants to stay for five years in the building they occupied. A buying frenzy followed, while efforts to amend the law in favor of the original owners overall failed. Critics of the 1995 statute argued that favoring tenants meant, in fact, favoring the former communist nomenklatura who occupied and bought these houses.

The Constitutional Court overall confirmed the protection afforded tenants and implicitly the operative conception of property. The court established the principle that former owners were not protected by the Constitution because of the principle of nonretroactivity of the law (Decision 62/June 13, 1995). The court also held that the Constitution guaranteed only the right to already existing property, and did not embrace the right to acquire property, which in this case meant that former owners had to observe property rights constituted under the communist regime (Decision 126/November 16, 1994). Furthermore, in a seminal 1995 decision, the court held that there was no constitutional right to restitution or compensation (later the court clarified that a statutory right was created by Law 112) (Decision 73/July 19, 1995). Finally, the court held that, as a matter of public law, there were no legal relations between former owners and tenants of nationalized housing (Decision 2/February 3, 1998).

Former owners interpreted the post-1989 restitution efforts as another nationalization. Despite their pressures, it is unlikely the situation would have changed had it not been for the aspiration of the country's elites to join the European Union. Eager to overturn perceptions of failing in transitional justice, modernization, and capitalism, parliament reversed course and adopted Law 10/2001, which established the principle of natural restitution as primary, and compensation as secondary (only when physical restitution was not possible), thus reversing the logic behind Law 112, and sending a message about the state's newfound commitment to protect private property in its more absolutist version.

Law 10 expanded the scope of claimants, allowed for restitution on the basis of court decisions, protected tenants' leases and the property rights of tenants who had bought on the basis of Law 112, imposed short statutes of limitations for owners to file restitution claims, and restricted physical restitution for buildings used for institutional purposes (see Stan Reference Stan2006, 195–96; SAR 2008). The implementation of Law 10 (amended multiple times) has also been problematic, plagued locally by wide discretion at the local level, extensive litigation, difficulties determining compensation, contradictions between Law 10 and its implementation instructions (which were issued two years after Law 10 itself!), and the lack of centralized coordination and unified implementation (Stan Reference Stan2006; SAR 2008).

The European Court of Human Rights as a Source of Legal and Rights Consciousness

A key element distinguishing restitution post-1989 from nationalization is the mobilization of supranational power structures, and in particular the ECHR. If nationalized owners in the 1950s and 1960s had as final recourse the Council of Ministers and the top level of the Communist Party, by the late 1990s they had the option of leveraging Romania's desire to become “European” and to appeal to the ECHR. Former owners challenged in particular the practice of annulment appeals, the sale of nationalized property to tenants, and the mandatory extension of rental contracts (SAR 2008). The ECHR has responded positively and found Romania responsible for failing to provide effective mechanisms for restitution and compensation (Străin and Others v. Romania 2005), failing to decide promptly on claims (Atanasiu v. Romania 2010), conflicting interpretations of restitution laws, and perpetuating legal uncertainty for former and new owners (Tudor v. Romania 2009) (Council of Europe 2011; DGIP 2010, 96–115).

In 2010, the court applied its pilot-judgment procedure (allowing the court to deal with large number of identical cases stemming from the same structural problem) for restitution issues in Romania. The court asked Romania to revise its national legislative framework and in particular to deal with two issues: the right to a fair hearing within a reasonable time, and the protection of property, more precisely, the ability to obtain compensation under the restitution laws (DGIP 2010, 96–97; Stan Reference Stan2013).

Following Atanasiu, the government recognized that the statutory framework for restitution was too complex, that it was incoherent, that the high number of unresolved claims—approximately 200,000—was unacceptable, and that the system overall was inefficient (see the statement of purpose for Law 165/2013). The Romanian government assumed responsibility and three years post-Atanasiu passed yet another restitution statute, Law 165/2013.Footnote 11 Law 165 established four principles at the heart of the process: favoring restitution over compensation, equity (fairness), transparency of the process, and, finally, maintaining a fair balance between the interests of former owners and the general interest of society. Eerily reminiscent of the nationalization process, Law 165 established a points-based compensation procedure when restitution was not possible,Footnote 12 and created the National Commission for Compensating Building Owners (Stan Reference Stan2013).

Like Laws 112 and 10, Law 165 faced numerous constitutional challenges, primarily related to its scope, deadlines, and restrictions on returned property. The Constitutional Court upheld the constitutionality of the statute overall and held fast to the concept of operative property, balancing throughout the claims of the former owners versus societal interests, for example, allowing temporary restrictions of property for buildings returned to their former owners (Decision 232/May 10, 2013), while also criticizing the government for constantly moving the goalposts for owners who had already filed a lawsuit (Decision 88/February 27, 2014).

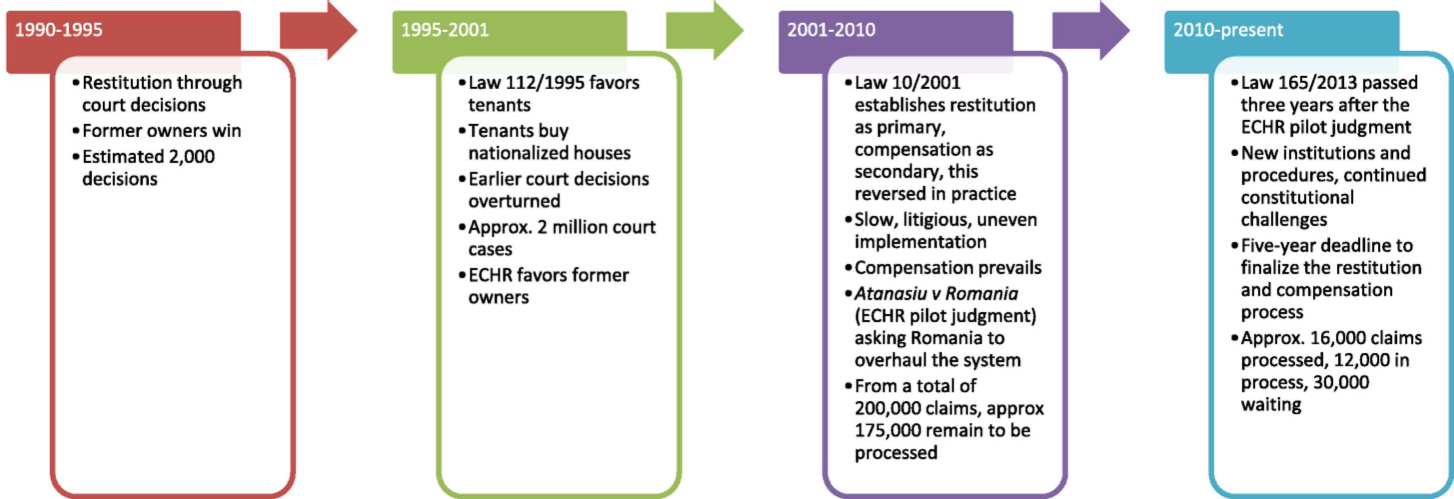

By April 2013, based on statistics offered by then Prime Minister Victor Ponta, approximately 10,000 buildings had been physically returned to the former owners (it is unclear how many residential units this includes), and only 13,000 compensation claims had been solved, out of a total number of over 200,000. Romania lost 435 property restitution cases before the ECHR, and had 3,500 pending cases before the court (Ponta Reference Ponta2013; Stan Reference Stan2013). By November 5, 2015, the National Authority for the Restitution of Property had solved 16,373 claims initiated under Law 10/2001, was working on approximately 700 claims per month, and estimated that it would finish them by June 2016. Still waiting at this point are 29,723 claims, and the Authority needs to finalize all requests by 2018 (Autoritatea Naţională pentru Restituirea Proprietăţilor 2015). Figure 1 shows key steps in the timeline of restitution.

Figure 1 Restitution Timeline. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The importance of the ECHR as a source of both legal and rights consciousness was evident during my interviews. Although the Constitutional Court's role is acknowledged, it is the ECHR that holds the emblematic role held by the Supreme Court in the United States. An attorney representing both owners and tenants was happy that there was a “true legal path” in property cases, but was also clearly bothered that “Romania is not independent from a property rights perspective … there is no national paradigm, but only the ideas of the ECHR.” Attorneys representing owners only (who are a minority; most take both types of clients) also acknowledge that the Strasbourg jurisprudence has become jus commune for property in the country, but embrace it completely, see it as more dynamic and in tune with current needs, and are deeply critical of Romania's lack of compliance with the court's decisions.

Owners, keenly aware that the ECHR has consistently ruled in their favor, see the Strasbourg Court as “Damocles' sword,” the only institution on their side, and the court's understanding of property as the true one. Some owners and their lawyers expected to lose in Romania, and therefore strategically prepared for Strasbourg from the first trial. The tenants I interviewed fear Strasbourg, but do not question its legitimacy and trust it. Tenants, like former owners, are critical of the Romanian state's approach to restitution because it did not promote legal certainty for property rights, whether old or new.

Differentiated Legal Consciousness: Owners and Tenants

There are striking similarities between communist housing nationalization and postcommunist housing restitution: they are both lengthy, convoluted, massive administrative and judicial processes that pitted former owners against the state and the tenants/new owners and revealed divisions, confusion, gaps, and inconsistencies within the owners group, tenants group, and the state apparatus, as well as the power of vested interests. There are two significant differences: the distinct ideological frameworks regarding private property, and the role of the ECHR in postcommunism. These processes clarify how various groups engage with the law, and are thus a site for the construction of legal consciousness.

Former owners, whether in communism or postcommunism, do not trust the state. Fighting against housing nationalization in the 1950s and 1960s, they attempted to harness socialist law for their own purposes, drawing from legal positivist, rule-of-law conceptions of legality (“subversive legality”; Şerban Reference Şerban2014). Post-1989, they are openly combative, do not trust the state or the law, and thus turn to supranational law. Tenants' experiences have led them to be similarly cautious and unhappy with the law. For both groups, the complexity and uncertainty of housing restitution is a common factor in the construction of their legal consciousness.

In Timişoara, by 2013 only 5 percent of the housing remained as state property, yet the restitution process has been protracted and litigious. The majority of claimants received compensation, not physical restitution of the building—for example, in 2006, only 393 housing units were given back, while for 1,732 the city hall offered compensation (Timişoara City Hall 2008, 11). Housing restitution claims are the second-largest category of civil lawsuits in the city, an average of over 300 every year (Timişoara City Hall 2013).

A typical restitution claim involves multiple steps, and I will use Maria's case as an example. Maria filed a restitution claim with the Timişoara City Hall in 1996, which forwarded the claim to the regional commission responsible for applying Law 112/1995 in 1997. The commission replied that Law 112 was not applicable in the case and that the petitioner needed to sue. Also in 1997, Maria asked the court of first instance to find the nationalization void (because the house was an Article 2 exception, and the name listed in the nationalization decree was wrong). Three years later and after city hall appealed its initial loss, the court of appeal irrevocably decided in Maria's favor in 2000.

Meanwhile, however, the tenants living in the nationalized house had bought their apartments on the basis of Law 112/1995 (three apartments out of a total of four). These purchase contracts were concluded after the decision of the regional commission finding that Law 112 was not applicable to the house. Maria sued the new owners, asking the purchase contracts to be found null and void (claiming the tenants were able to buy by taking advantage of their position as city hall employees). In 2003, the Supreme Court found in her favor, but before she could execute the decision, the new owners/former tenants sued Maria, challenging the death certificates of the original owners and her quality as heir. This became a civil as well as a criminal matter (against the notary public, who died) that dragged on until 2006 and was eventually resolved in Maria's favor.

Simultaneously, Maria petitioned the ECHR, which in 2008 rejected her complaint. Overall, Maria has been involved in at least ten different lawsuits since 1996 (all of them involving at least three different levels of appeal), against not only the tenants/new owners, but also the local authorities, which contested her title again as late as 2011. She has been in actual possession of one of the four apartments in the house (which she later sold).

Maria's case is not atypical. The attorneys I interviewed, whether they represented owners or tenants, confirmed this timeline. Not all of them specialize in property law, but most do have a solid property caseload, anywhere between twenty and thirty cases at any given time, most lasting years. Prior to the adoption of Law 112/1995, most cases were resolved within one to two years. Cases that advance to the ECHR last on average between three and five years (however, all the landmark cases that I examined lasted significantly longer, as did all the cases for which I conducted interviews). Not uncommonly, claimants die, but the heirs take over. All the attorneys, regardless of who they represented, distinguished restitution cases from other types of cases in terms of both length and impact on their own lives. One of them said these cases “have permanence,” becoming “part of the background of one's life.”

Owners' Legal Consciousness: The Weight of Unmet Expectations

Owners' legal consciousness has been shaped not just by the length, complexity, and uncertainty of the restitution process, but also by divisions among owners and relationships with tenants. There are two types of key differences that determined how and why former owners mobilized. The first is the distinction between owners nationalized under Decree 92/1950, and those who lost their property through other means, primarily expropriations. Initially, all former owners mobilized through the Association of Former Owners Victims of Communist Abuses. The association helped former owners to connect with each other, find sympathetic lawyers, gather evidence, reconstruct property genealogies for seized housing, draft restitution bills, coordinate efforts in court, mobilize public opinion, and so forth.Footnote 13

According to one of my interviewees, a retired construction manager who was very active in the local chapter of the association in the 1990s, divisions quickly emerged, however, between former owners whose houses still existed, and those whose houses had been demolished. For the former, restitution of housing itself was an option, while for the latter, compensation was the only option. The infighting led to permanent splits and distinct lobbying efforts in parliament. Separately, former owners who had also been tenants of nationalized housing simultaneously pursued restitution and purchase (of housing they occupied as tenants). For the other former owners, this was an unforgivable sin.

Another key distinction was between former owners and their heirs. Former owners had witnessed, as children or teenagers, the loss of housing and saw the impact this had on their families. One of them remembered her father walking down the street every week to check on the nationalized house throughout communism. Still alive in 1989, he immediately began efforts to reclaim the house, looking for documents and writing petitions to authorities. My interviewee's mother, who was not alive anymore, had collected ownership documents going back to 1943 in a bundle tied with a pink ribbon. My interviewee's daughter, on the other hand, who emigrated to Israel with her family after 1989, had no emotional attachment to the house, and reproached her mother for being more attached to the house than to her.

Attorneys representing owners, as well as other heirs I interviewed, confirmed this rift. Heirs were significantly less interested in fully throwing themselves into the restitution battle. Some were resigned, as was the case with the nephew of an interwar rabbi, who was living abroad and decided to pursue compensation, instead of physical restitution, for his uncle's nationalized house. Others were interested only in the financial aspects of the restitution. Whether and how one pursued restitution was thus a matter of opportunity, not just repairing a historical injustice. The value of the housing was significant enough that an entire cottage industry of both lawyers chasing restitution (a Romanian version of ambulance chasers) and buyers of claims emerged. The distinction between former owners with a stake in the restitution process and peddlers of history was recognized both by Law 165 and the Constitutional Court, which upheld the provision that compensated differently former owners from those who had merely bought the claim to restitution, precisely because of the personal connection and the abusive nature of the taking vis-à-vis the former owners (Decision 197/April 3, 2014).

Maria's case is also typical in terms of complexity of the restitution process, and in particular the evidence required. My interviewees had to prove their genealogy and family history, ownership, and that the house had been seized by the state. In the early 1990s, former owners who sued claimed they should have been exempt from nationalization. Two former owners I interviewed, both in their late seventies, had to prove their parents had not been “exploiters.” They spent time and money collecting documents of their social origin (leather craftsman and engineer, respectively), a nationalization time warp.

Another interviewee faced a Kafkaesque task: part of his garden had been expropriated to build a block of flats. The block was never built, but the state had nonetheless registered it in the real estate registry, which officially meant the building existed. My interviewee had to pay and bring three different experts to the site to certify that the block of flats had never been in fact erected.

All the former owners and heirs I interviewed deeply distrusted the legal process, in particular the lawyers and judges at the local and national level (but not at the ECHR). Their restitution claims were the first encounter with the courts, and their experiences were unsettling. Some encountered judges who swore at them (“the judge showed me the finger”) or screamed at them. One owner observed that “[t]hey—judges—do not like you talking much.” One interviewee claimed that documents disappeared from the official file (so she made copies of everything separately, as did all my interviewees). Former owners perceived the state attorneys and judges to be biased based on two factors: whether they or a family member lived in a nationalized house, and whether one of the parties in the trial knew them personally.

Confirming findings elsewhere about the link between procedural justice and trust in the legal system (Tyler and Huo Reference Tyler and Huo2002), former owners distrusted the system even when they eventually won. In one case, the prosecutor (state's attorney in restitution cases) gave up his argument that the plaintiff's father had been a businessman and therefore subject to housing nationalization when he realized his parents-in-law had been neighbors with the plaintiff's parents in the 1960s. My interviewee found this out at the end of the lower court trial, when the prosecutor approached her and congratulated her for winning.

To the extent that former owners pursued their claims to the Supreme Court (many did), their experiences and perceptions of the legal system did not improve. They did not understand the endless delays, yet were themselves willing to delay trials if they thought political changes would bring legal changes (e.g., in 1996). They followed the advice of their attorneys and, without understanding the legal reasons (by their own admission), petitioned the Constitutional Court as another delaying tactic (“with the law”).

This deep distrust in the law—“against the law” legal consciousness—was an interesting finding in light of the fairly consistent record of wins for former owners at the trial level in Timişoara and the surrounding area. Winning was not enough to counterbalance the poor treatment former owners experienced in court, the seemingly open-ended nature of the restitution process (“Nothing in Romania is definitive and irrevocable,” said one of my interviewees, echoed by others), and the counterclaims by tenants. The distrust in the law was connected, but separate, for them, from distrusting the state. All my interviewees claimed that the key reason the state did not return the seized houses was that state officials lived in them and wanted to keep them.

Finally, owners' legal consciousness is shaped by their interactions with tenants. Although state law does not acknowledge direct relations between owners and tenants, these relations are, in fact, key for understanding the restitution field. The beginning was somewhat auspicious, as former owners placed the blame for nationalization squarely at the feet of the communist regime, and depicted tenants as equal victims of the regime (Vasiliu Reference Vasiliu1992). Lawsuits and counterlawsuits, as well as Law 112, fractured this fragile peace permanently.

Former owners vacillated between feeling sorry for the tenants, to claiming they knew or should have known all along they lived in nationalized housing, to suspecting tenants of using their jobs to derail the restitutions (e.g., if tenants worked in city government). Some former owners claimed that tenants purposely neglected or destroyed housing, and there were divisions between former owners who wanted to evict the tenants immediately and those who preferred to have them stay and collect rent. This was especially true for very long-term or life tenants, such as a tenant who had lived his entire life, from the early 1930s until the present, in an apartment from a nationalized house. The owner remembered him from their childhood, and found deep meaning in his continued presence in the house.

Tenants' Legal Consciousness: Cautious Distance

Tenants' legal consciousness is not far removed from the former owners'. While they perceive themselves to be on different sides of the restitution battle, tenants share with owners the distrust in the legal process and the state, think the state favors the owners, and think that they are unfairly paying for the failings of the communist regime. While all the former owners I interviewed were either directly involved with the Association of Former Owners or used its resources, none of the tenants were involved with the local tenants' association. The tenants I interviewed had different professions: teacher (elementary and high school), university professor, musician, accountant, librarian, computer programmer, mechanic.

Half the tenants had an easy experience buying their housing from the state under Laws 61 or 112, while two found it a somewhat difficult process. Two of my interviewees did not manage to buy because former owners had started the restitution process. The owners were eventually successful and the tenants had to move out. The tenants who were sued did not expect it, and were surprised to find out that former owners even existed. One of the tenants was sued every time a new statute or implementing decree was issued, but the tenant never met the former owner or spoke to her. Another tenant, an elementary school teacher, was shocked to find out that her neighbor of twenty-five years had owned the house prenationalization and had never told her, even though they shared the same hallway. The tenant and her husband found out only by accident that the former owner had started the restitution procedure.

Tenants, like the owners, and for similar reasons, also deeply distrusted the law and legal system, and thought “the law was unfair, the Romanian state did not do what it should have done to protect tenants.” They found the frequent statutory changes confounding, and complained about legal uncertainty (length of trials and lack of resolution through multiple appeal levels), lack of clarity, and how “every political change brought a different interpretation, which is not right.” Tenants, like former owners, did not necessarily favor compensation or restitution, but wanted legal clarity and finality. They thought the law was biased in favor of former owners because “the law was so big—everyone could come and ask for property, and did not need many documents to verify their quality of former owners.”

While tenants did not experience hostility from judges, some of them thought judges were biased in favor of the owners, and that the outcome of the cases depended on judges' personal opinions on restitution. Unlike former owners, none of the tenants had to compile lengthy or complex evidence files, and some of the tenants (depending on trial type) had not only their own lawyer present, but also the lawyer representing city hall.

Tenants most distrusted the lawyers representing former owners. They found the owners' lawyers to be extremely combative, and thought a key reason for the trials and restitution overall was that the lawyers were manipulating the former owners in exchange for the house or on a contingency fee basis: “The problem is that there are too many lawyers who do not defend the interests of the real owners, but various other interests. This is a disaster, even dead people can go to court as owners, this is inadmissible, it's all because lawyers want to get rich.” (The attorneys I interviewed were paid either on an hourly basis, or based on a contingency fee type of arrangement.) Tenants were also aware that lawyers were repeat players, and thought this put them at a disadvantage.

Whether and how tenants engaged with the law, however, was significantly determined by their relations with the former owners. The elementary school teacher who had not been aware that her neighbor was the initial owner was so deeply hurt and betrayed that she decided not to engage in the restitution process or make any compensation claim for the improvements to the house. She thought the former owner had stabbed her in the back after all the help the tenant had given her over the years. Tenants who did not know the former owners, however, found it easy to use the law. The less contact they had with the former owners, the more comfortable they felt turning to the law and, to a certain extent, trusting the law to give them justice. They rarely condemned the owners outright (more often condemning their lawyers).

Tenants accused the former owners of greediness. They thought owners had already received compensation from the communist regime (or Germany or Israel, if they emigrated), so asking for restitution or compensation after 1989 was unfair. (In fact, nationalized owners received no compensation, while those who were expropriated received a nominal sum, and not always. Owners who emigrated received some minimal support from the countries of immigration to help them integrate in the new society.) Owners overall, as a category, were perceived as “having no soul” if they evicted tenants after winning back their houses, if they gloated, and if they sold the houses or apartments.

Tenants who were sued by former owners (mostly to annul purchase contracts under Law 112) deeply resented it; it is “as if we were criminals, we had to prove we did nothing wrong.” One of them, a business owner, had a stroke and blamed it on the stress of the trials, while another one developed an ulcer.

For both owners and tenants, whether and how they engaged with the law depended not only on the state, but also, equally importantly, on their expectations, experiences with courts and lawyers, and relationships with each other. Both groups distrust the state and national legal system (“against” the law, albeit at different levels), respect and value the ECHR (“before” the law), and are overall very strategic (“with” the law) (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998). That none of the lawyers, owners, or tenants were ever physically present before the court (including an attorney who won landmark ECHR cases) casts an aura of international justice with which the local courts can hardly compete.

Differentiated Property Rights Consciousness: Owners and Tenants

The state has been an equivocal source of property rights consciousness for the two key constituencies from a statutory perspective. The Constitutional Court operated fairly consistently within an ideology of operative, grounded, flexible property that favored tenants, yet also repeatedly described communist takings as abusive, thus also providing ideological grounding to former owners. Lower courts tended to find in favor of former owners, thus implicitly embracing a more absolutist conception of property rights based on title, while the ECHR embraces an operative conception of property in general, while finding in favor of former owners in restitution cases. Yet other sources of rights consciousness are equally compelling, primarily family, labor, use, historical justice, and time.

Owners and Their Heirs: Title, Labor, Historical Justice

Rights consciousness for the former owners has distinct, not necessarily consistent, sources: precommunist state laws, formal title, natural law ideas about property and justice, postcommunist restitution laws, history, and identity. Rights in this understanding, certainly property rights, have a rather static quality, in large part connected to the erasure of time, itself linked to perceptions of the lack of legitimacy of communism, and confirmation by the ECHR and postcommunist laws of former owners' property claims. Their rights expectations are intimately connected with the rejection of the prior, communist regime, and the restoration of the prewar past.

Former owners and their lawyers hold an absolutist view of private property—“the holy light of property,” said a former owner—and see it as the basis of order and civilization, and the opposite of communism. They see property titles acquired before communism as inherently beyond reproach, while property acquisition during communism, whether by the state or individuals, is inherently suspicious. Former owners did not question title acquired during the war, either, even when they had sufficient reason to do so. Two of my interviewees were aware that their houses were bought during World War II from Jewish families who were subject to policies of Romanianization (an integral part of the Holocaust) and were forced to sell at below market value. The tenants I interviewed, meanwhile, were aware of these histories and held them against the former owners when comparing title.

Former owners or their heirs also mobilize discourses of family, labor, justice, and compassion. In both written documents and interviews, they describe how their parents or grandparents had worked to build or buy houses that could serve the extended family: “My parents worked like oxen to build a house, only for the communists to take it all away.” My interviewees gave me long family histories that involved piecemeal acquisition or building of the houses, mostly by parents and grandparents of middle and lower-middle class origin (such as leather maker, carpenter, teacher, grocery store owner, etc.). Heirs were significantly less likely to romanticize the houses, and simply talked about the importance of title.

Unlike the 1950s, post-1989 the injustice of the taking became a more important source of property rights consciousness for the former owners. Former owners had always emphasized in their 1950s and 1960s petitions that housing nationalization, from their perspective, was an unjust taking, wrong based on both socialist and bourgeois notions of justice. The discourse of the fundamental injustice perpetrated through nationalization resurfaced post-1989 in the articles, bills, and memoranda prepared by the National Association of Owners Abusively Dispossessed by the State, for whom housing restitution symbolizes reparatory justice, an acknowledgment that communism was wrong and that the takings were unjust (Association of Owners Forcibly Dispossessed by the State [APDAS] 1994, comment on Law 112). Former owners repeatedly mentioned the injustice of nationalization and expropriation, and expected formal apologies from the state and from tenants of nationalized houses, whom they perceived to have taken advantage of the situation. When the former center-right president Traian Băsescu apologized to the victims of communism, one of my interviewees was very touched and cried because it was the first time any state official had addressed the issue.