I. Introduction

Involuntary property loss is ubiquitous. During conquest and colonialism, European powers robbed native peoples of their lands; wars and civil conflicts have undermined and rearranged ownership rights; communist regimes have upended existing ownership rights in attempts to usher in a more egalitarian property distribution; and most constitutional democracies sanction the forced taking of property as long as the state pays just compensation and it is for a public purpose. In some of these examples, state or nonstate actors have taken property from an individual or a group and material compensation is an appropriate remedy. In other instances, however, the property confiscation resulted in the dehumanization or infantilization of the dispossessed, and so providing material compensation is not enough because they lost more than their property—they were also deprived of their dignity. In We Want What's Ours: Learning from South Africa's Land Restitution Program (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a), I labeled this dual harm a “dignity taking” and argued that the appropriate remedy is something more than mere compensation for things taken (reparations). What is instead required, I argue, is “dignity restoration,” which addresses deprivations of both property and dignity by providing material compensation to dispossessed populations through processes that affirm their humanity and establish their agency.

Although pervasive, sociolegal scholars have not treated the intersecting deprivation of property and dignity as an area worthy of systematic examination and analysis. Using South Africa's recent efforts to restore land to those dispossessed under the colonial and apartheid regimes, We Want What's Ours empirically develops the concepts of dignity takings and dignity restoration. My study is based on 150 interviews conducted with South Africans who were forcibly removed from their urban properties and who received some form of compensation through the Land Restitution Commission, twenty-six interviews of officials from the Land Restitution Commission, and nine months of participant observation in the commission itself (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a). South Africa is a critical case for exploring the concept of dignity takings because when it transitioned from apartheid to democracy in 1994, 87 percent of the land was owned by whites although they constituted only about 10 percent of the population. This was due to rampant colonial and apartheid era land theft, which Europeans rationalized by invoking the myth that Africans were inferior, uncivilized savages, and white Christians had a duty to take care of this childlike people (van der Westhuizen Reference Van der Westhuizen2007). Consequently, colonial and apartheid era land dispossession occurred in the context of dehumanization and infantilization and therefore is a quintessential case of dignity takings.

Another reason that South Africa is a critical case for theory development is because the government has actually tried to move from reparations to the larger more robust task of dignity restoration. To address past land theft, the drafters of the postapartheid constitution included Section 25.7, which states that all individuals or communities who were dispossessed of any right in land after 1913 as a result of a racially discriminatory law or policy are entitled to an equitable remedy (South African Constitution 1996). The South African Parliament fulfilled this constitutional mandate by enacting the Land Restitution Act (1994), and creating the Land Claims Commission to implement it. The former Minister of Agriculture and Land Affairs, Thoko Didiza, explained that “the struggle for dignity, equality and a sense of belonging has been the driving force behind our work as the Land Claims Commission. …” We Want What's Ours empirically examines the ways that the Land Claims Commission succeeded and failed at this larger task of dignity restoration.

To further develop and refine the concepts of dignity takings and dignity restoration, symposium authors consider their application beyond the South African context. Case studies include: the separation of Hopi people from their sacred lands (Richland Reference Richland2016); the requirement that all married women give their property to their husbands under the laws of coverture (Hartog Reference Hartog2016); the dispossession of Bedouins and Arab citizens in Israel (Kedar Reference Kedar2016); the looting, burning, and destruction of African American property during and after the 1921 Tulsa race riot (Brophy Reference Brophy2016); the property taken from Loyalists during the course of the American Revolution (Hulsebosch Reference Hulsebosch2016); the forced evictions in China intended to create space for its rapidly expanding cities (Pils Reference Pils2016); the use of racially restrictive covenants in the United States (Rose Reference Rose2016); and the taking of Jewish property in France and the Netherlands during World War II (Veraart Reference Veraart2016). By testing the concepts of dignity takings and dignity restoration in a variety of cases, contributors are able to confirm, extend, or revise my original formulation of these concepts.

Section II of this article explains how the concepts of dignity takings and dignity restoration originated from the South African case. Using the eight case studies written for this symposium, Section III establishes the parameters of a dignity taking and what dignity restoration entails. Section IV concludes by presenting the revised definition of dignity takings and dignity restoration, and suggesting areas for future research. The ultimate goal of this article and the larger symposium is to refine the concepts and thereby provide a theoretical framework that scholars can use to better understand the material and immaterial dimensions of involuntary property loss as well as what is required to fully remedy the loss. The framework also allows an interdisciplinary cast of scholars to draw connections between seemingly disparate instances of property deprivation.

II. Dignity Takings and Dignity Restoration—The Original Theoretical Framework

A. Dignity Takings

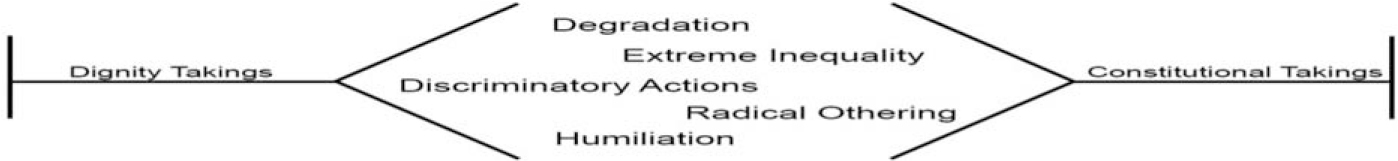

Constitutional takings are when a state confiscates property against an owner's will, but it is for a public use or purpose and just, fair, or adequate compensation is paid (Van der Walt Reference Van der Walt1998). With the exception of Canada, every constitutional democracy has a takings clause, and there has been substantial scholarship on the subject. Scholars have extensively debated when property loss caused by regulatory change is covered by the takings clause and thus requires compensation (Fischel Reference Fischel1995; Rose Reference Rose2000), which factors should be included and excluded from compensation calculations (Michelman Reference Michelman1967; Blume and Rubinfeld Reference Blume and Rubinfeld1984; Serkin Reference Serkin2005), and what constitutes a public purpose (Dana and Merrill Reference Dana and Merrill2002; Kelly Reference Kelly2006). Although the terms “taking” and “constitutional taking” are often used interchangeably in the legal academy (Epstein Reference Epstein1985), a promising field of research unfolds when the term “taking” is expanded to include various types of involuntary property loss across a wide spectrum.

As redefined, a taking is when the state directly or indirectly takes property ownership or use rights from individuals or communities without permission. It is involuntary property loss that can involve displacement (physically moving people from the property they occupy or possess), dispossession (annulling or diminishing people's property rights), or both forms of deprivation. As shown in Figure 1, on one side of the takings spectrum are constitutional takings, which have been thoroughly studied. There has, however, been scant scholarship about the opposite side of the takings spectrum where dehumanization or infantilizaiton results. These dignity takings can occur in liberal regimes where the forcible taking of property is exceptional; during the massive restructuring of property rights brought on by regime change or societal upheaval; or as the normal operation of an oppressive regime as happened in South Africa during white rule. Most importantly, subordinated and vulnerable populations have been consistently subjected to dignity takings throughout history, yet the legal scholarship on takings has primarily focused on constitutional takings, rendering this outsized suffering largely invisible. By developing the concept of a dignity taking, I provide a common vocabulary to systematically discuss and analyze deprivations of property that also involve a loss of dignity, bringing this important conversation out of the dimly lit basement of sociolegal inquiry and onto its center stage.

1 The Takings Spectrum

In the middle of the takings spectrum are property confiscations that are not quite dignity takings and also do not qualify as constitutional takings. These takings occur as a result of humiliation, degradation, radical othering, unequal status, or discriminatory actions that do not rise to the level of dehumanization or infantilization. Since both dignity takings and constitutional takings are narrowly defined, the middle category is expansive. Certain authors in this symposium argue that their case study falls into this category (Hartog Reference Hartog2016; Hulsebosch Reference Hulsebosch2016; Kedar Reference Kedar2016). To preview one example discussed later in more detail, Hartog (Reference Hartog2016) argues that, from the perspective of the women who were subject to coverture, the fact that marriage required them to forfeit their property to their husbands was not dehumanizing or infantilizing, and hence there was no dignity taking. Nor was this a constitutional taking, so the case would fall in the middle of the takings spectrum.

1. Theoretical Underpinnings

The concept of a dignity taking was born from two observations about how individuals and groups are removed from or subordinated within the social contract. The first is John Locke's point about the relationship between property and dignified membership in a political community, which highlights the deep-seated consequences of state-sanctioned property confiscation (Locke [1690] Reference Locke and Laslett1980). Locke argues that the social contract came into existence when men gave up their God-given individual sovereignty and vested it in the state in exchange for the protection of their lives, liberty, and estates. He further argues that all men are bound by the social contract and are not allowed to exit unless the state's unjust actions annul their equal standing in society. The wrongful confiscation of property is sufficient to rescind the social contract because it is an act that subordinates the dispossessed and prevents them from being full and equal members of the polity.

The second observation comes from Pateman and Mills's criticism of Locke and other mainstream social contract theorists for failing to acknowledge that only white men entered the social contract as full and equal members. They argue that the systematic dehumanization of people of color and the infantilization of women kept them subordinated within the social contract and deprived of their full dignity (Pateman Reference Pateman1988; Mills Reference Mills1997). In The Sexual Contract, Carole Pateman argues that alongside the social contract exists a corollary sexual contract that ensures and solidifies men's political right over women (Pateman Reference Pateman1988). The imaginations of Locke, Hobbes, Kant, Rousseau, and other social contract theorists were arrested by the myths of female inferiority that reigned unchallenged in their respective time periods. One factor that harmonized the writings of these men was the transformation of anatomical differences between women and men into political difference such that women were not considered full-fledged persons who possessed the mental acumen necessary to enter into the social contract on the same terms as their male counterparts. As a consequence, women were subordinated within the social contract and deprived of their dignity.

In The Racial Contract, Charles Mills explains that one fundamental premise of social contract theory is that men are born free and live as such in the state of nature, but European powers considered nonwhite people to be savages born “unfree and unequal” (Mills Reference Mills1997, 16). Through conquest and colonialism, European powers legally codified this subordinate status, which was then perpetuated by both individuals and institutions. As evidence that the great philosophers considered nonwhites to be a savage, separate species who did not have the capacity to reason, Mills points to “Locke's speculations on the incapacities of primitive minds, David Hume's denial that any other race but whites had created worthwhile civilizations, Kant's thoughts on the rationality differentials between blacks and whites, Voltaire's polygenetic conclusion that blacks were a distinct and less able species, and John Stuart Mill's judgment that those races ‘in their nonage’ were fit only for ‘despotism’” (Mills Reference Mills1997, 59–60). Due to these racist beliefs, people of color were subordinated within the social contract and denied their dignity.

There are many different ways that individuals and groups have been excluded from or subordinated within the social contract and denied their dignity, including rape, torture, execution, disappearance, unequal opportunity, social exclusion, and psychological abuse. But, the idea of a dignity taking is predicated on Locke's observations as well as on Pateman and Mills's critique of Locke, which taken together highlight two particular ways to subordinate or exclude an individual or community from the social contract: the state can unjustly deprive people of their property or their dignity (through acts that dehumanize or infantilize them). A dignity taking is when these two strands intersect and a state directly or indirectly deprives people of their property and their dignity.

2. Definitions

A dignity taking involves involuntary property loss accompanied by dehumanization or infantilization. As I originally defined the term, “dignity takings are when a state directly or indirectly destroys or confiscates property rights from owners or occupiers whom it deems to be sub persons without paying just compensation and without a legitimate public purpose,” and I define a sub person as someone who has been either dehumanized or infantilized intentionally or unintentionally (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a, 3, 30). I use dignity as the central concept because it resonates across cultural, geographic, and religious divides. Although moral philosophers such as Kant ([1785] Reference Kant and Gregor1998) have been important for how Western thinkers understand dignity, it is a concept that also can be located within cultural and religious belief systems found in regions such as Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. There are many different definitions of dignity, but the one I adopt is based on two central elements: equal human worth and autonomy. I define dignity as the notion that people have equal worth, which gives them the right to live as autonomous beings not under the authority of another. Consequently, individuals and communities are deprived of dignity when subject to dehumanization, infantilization, or community destruction.

Dehumanization is the failure to recognize an individual's or group's humanity. When peoples' humanity is invisible, they are no longer regarded as humans having the mental acumen, soul, or agency necessary to enter into the social contract. Examples of dehumanization include the Nazis' belief that Jews were vermin, the South African colonial and apartheid governments' undisguised belief that blacks were savages, and the militant Hutus' belief that Tutsis' lives were worth no more than cockroaches. Infantilization is a dignity deprivation distinct from dehumanization because it is predicated on lack of autonomy rather than on a lack of human worth. Infantilization is the restriction of an individual's or group's autonomy based on the failure to recognize and respect their full capacity to reason. While the person's humanness may be acknowledged, his or her capacity for rational self-governance is not. Most commonly, infantilization involves treating adults as if they were minors, and thus placing them under the authority of another, robbing them of their autonomy.

While infantilization negates independence, community destruction undermines interdependence. Community destruction is when a community of people is dehumanized or infantilized, involuntarily uprooted, and deprived of the social and emotional ties that define and sustain them. Within the liberal tradition, autonomy is defined narrowly and equated with individualism, independence, and choice, but Jennifer Nedelsky argues for a more robust conception of autonomy, which acknowledges that both independence and interdependence are key elements because it is impossible to become an autonomous person without the support and assistance of others (Nedelsky Reference Nedelsky2011). Also, people do not choose many of the relationships central to developing their capacity for autonomy, such as their parents, teachers, and the structures of state assistance. Including community destruction as a core dignity deprivation acknowledges that when people are separated from their cultural anchors, faith communities, jobs, families, neighbors, and schools, they are robbed of vital sources of interdependence—and hence their autonomy.

The consequences of community destruction can be severe. Through in-depth interviews with people uprooted by the urban renewal programs of the 1950s and 1960s, Mindy Fullilove found that these displaced populations often suffered from root shock—“[t]he traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of all or part of one's emotional ecosystem” (Fullilove Reference Fullilove2004, 11). Root shock can result from state-led displacement (such as urban renewal), natural disasters, armed conflict, and the simmering effects of gentrification. Fullilove argues that displacement from homes and property can create psychological trauma, anxiety, destabilized anchoring relationships, weakened communities more vulnerable to negative forces, chronic illness, and even death. These negative consequences can extend to multiple generations.

B. Dignity Restoration

In We Want What's Ours, I also consider the remedies available for victims of dignity takings. I argue that mere reparations are not a sufficient remedy. A comprehensive remedy for dignity takings involves addressing the deprivation of property and dignity, which can be accomplished through a mixture of reparation and restorative justice. Reparation is “the right to have restored to them property of which they were deprived in the course of the conflict and to be compensated appropriately for any such property that cannot be restored to them” (United Nations 1996, 2(c)). The goal of restorative justice is “restoring property loss, restoring injury, restoring a sense of security, restoring dignity, restoring a sense of empowerment, restoring deliberate democracy, restoring harmony based on a feeling that justice has been done, and restoring social support” (Braithwaite Reference Braithwaite1999). The offspring of this formidable union between reparations and restorative justice is dignity restoration. I define dignity restoration as “compensation that addresses both the economic harms and the dignity deprivations involved” (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a, 4), and its purpose is to “rehabilitate dispossessed populations and reintegrate them into the fabric of society through an emphasis on process” (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a, 57).

Restitution, redistribution, reparations, and restoration are all remedies, so it is important to understand how they relate to dignity restoration. Restitution and redistribution address property deprivation because they are methods of reallocating wealth. Restitution provides compensation to dispossessed individuals or communities for property rights unjustly expropriated in the past, while redistribution provides assets based on current need or ability to use the property rather than based on prior ownership rights. Since dignity restoration is not only about addressing deprivations of property but also of dignity, attention to process is necessary because this is the dignity-restoring aspect. As defined here, reparation and restoration are process-oriented terms. Reparation is a widely used term with multiple meanings, but at its lowest common denominator it entails providing compensation for material deprivations and the focus is on outcomes. Restoration moves beyond the focus on outcomes, places great importance on how the process transpires, and can thus potentially address dignity deprivations. Nevertheless, most state-sponsored initiatives to remedy past property seizures have focused on reparations rather than dignity restoration because reparations are less time consuming, complicated, and expensive (Leckie Reference Leckie2000). South Africa's postapartheid government is, however, unique because it understood its land restitution program as an opportunity to restore property as well as dignity to its citizens.

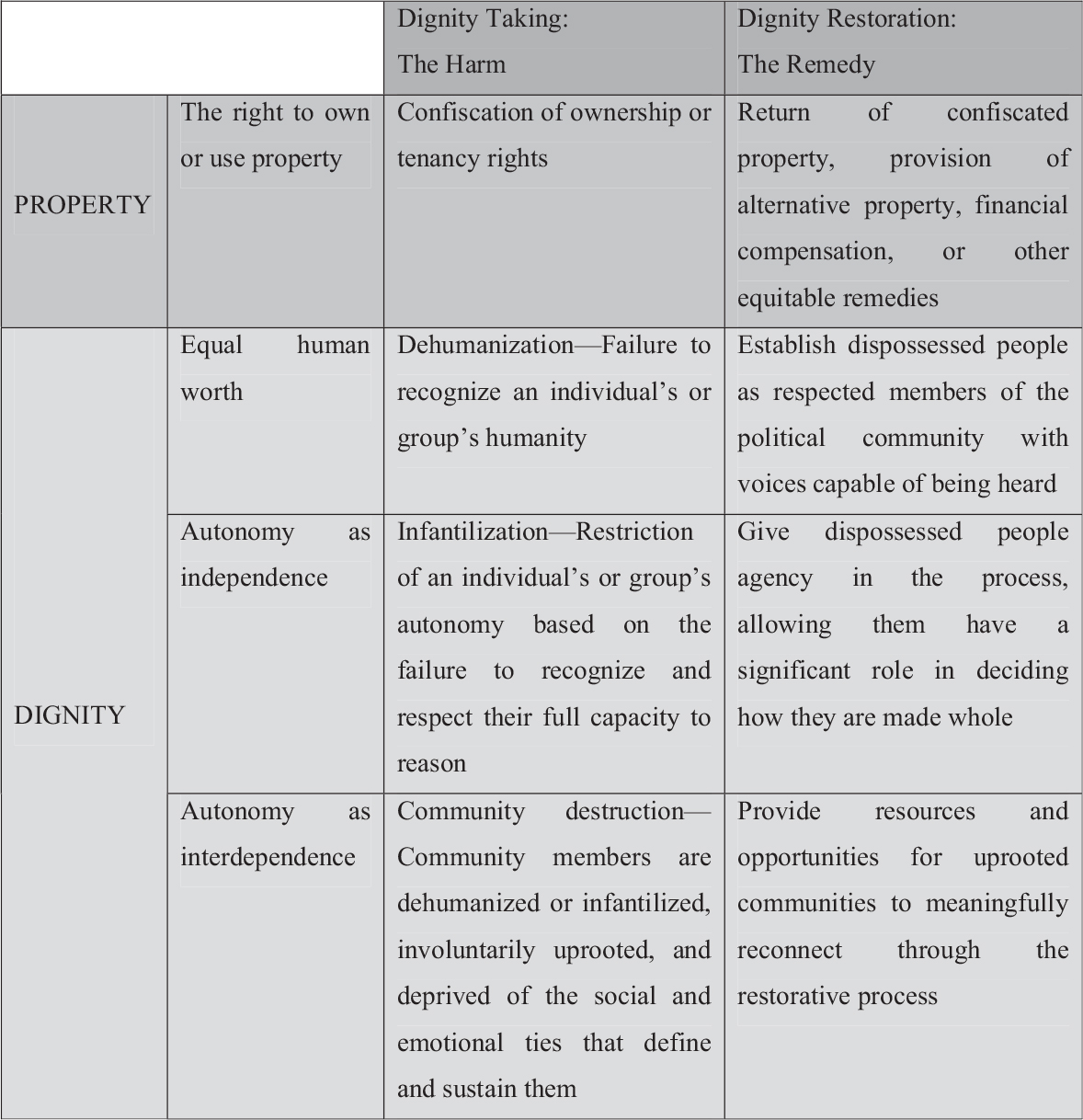

Dignity restoration can take several forms, occur over any length of time, and have either state or nonstate actors create and implement the resulting initiatives. Full dignity restoration requires that dispossessed people receive adequate material compensation as well as uniquely fashioned remedies for the dehumanization, infantilization, and community destruction experienced. We Want What's Ours provides a detailed assessment of the failures and successes of the South African Land Claims Commission in its struggle to move from reparations to the more difficult task of dignity restoration (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a). The intent of Figure 2 is to outline the different types of harms experienced in South Africa and the potential remedies in order to illustrate what dignity takings and dignity restoration can look like.

2 Dignity Takings vs. Dignity Restoration in the South African Context

The material compensation that the commission provided to dispossessed populations was supposed to include a choice between the return of confiscated property, provision of alternative property, adequate financial compensation, or a host of other equitable remedies. But, material compensation was inadequate because about 88 percent of claims were urban and 73 percent of those claimants received financial payouts, which were not based on the market value of the property rights confiscated (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2011, 3). There were also many mechanisms the commission could have used to address dignity deprivations. The commission had an opportunity to address the dehumanization of dispossessed groups and acknowledge their equal human worth by establishing their equal standing in the polity as full citizens with voices capable of being heard by prevailing power structures. But, communication breakdowns abounded, undermining the commission's ability to show respect by listening to dispossessed populations (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014b). To remedy the infantililzation experienced, one thing the commission could have done was to allow dispossessed populations to have a heavy hand in deciding which remedy they would receive. Most claimants, however, had no choice (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a). To address community destruction, the commission could have created opportunities for dismembered communities to meaningfully reconnect through the remedial process. Communities were, in fact, able to meaningfully reconnect when communication between the commission and claimants went well, but when communication breakdowns proliferated, severe community tensions often resulted (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014b).

It is important to note that efforts to promote dignity restoration in South Africa happened in tandem with other non-property-related measures. As in many other nations, dignity takings in South Africa occurred within a larger process of subjugation that included disappearance, torture, educational disruption, political exclusion, incarceration, sexual violence, and even death. Property dispossession both exacerbated and reflected blacks' subordinate position in the polity. Consequently, the postapartheid state has tried to remedy the full spectrum of dignity deprivations through several distinct, but interrelated measures. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission brought to light the political repression, psychological violence, death, and torture perpetrated under past regimes. The postapartheid constitution made blacks equal before the law by giving them civil, political, and socioeconomic rights; and the Constitutional Court was the new institution created to defend these newly acquired rights. Also, affirmative action programs have tried to overcome the historic exclusion of blacks from opportunities in the public and private sectors. The postapartheid state's attempts to facilitate dignity restoration have occurred in conjunction with all these other efforts to upgrade blacks from their old status as sub persons to their new status as dignified members of the polity. If dignity restoration efforts are not accompanied by programs to rectify non-property-related dignity deprivations, then owners are unjustly placed above those who were never able to acquire property in the first place.

III. Developing the Theoretical Framework: Dignity Taking and Dignity Restoration Beyond the South African Context

A. Dignity Taking

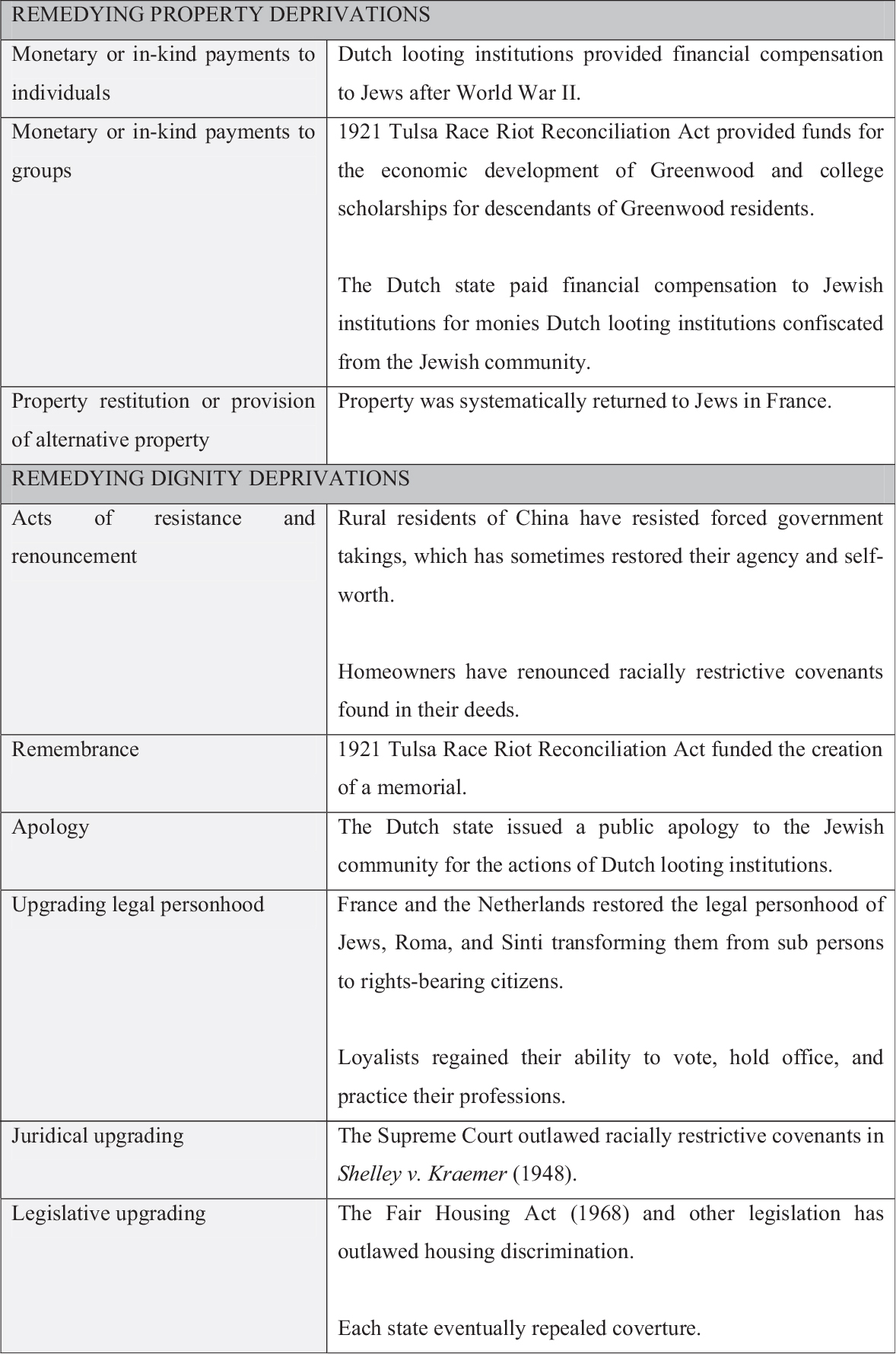

When introducing a new theoretical framework, it is imperative to clearly state its parameters. To qualify as a dignity taking, there must be involuntary property loss plus either dehumanization or infantilization. If there is a taking that entails humiliation or degradation, but no dehumanization or infantilization has occurred, then there has been no dignity taking. To develop the theory and identify where it needs to be refined or qualified, this section explores whether or not each of the eight case studies examined in this symposium qualifies as a dignity taking, and the evidence required to make this determination. In some cases, the evidence presented allows us to make a definitive assessment of whether or not dignity takings occurred, but in other cases the quantity or quality of the evidence does not permit definitive conclusions. There is often significant room for debate. This is why the conclusions I draw are sometimes different from those of the case study authors, which are displayed in Figure 3. My goal here is to use the theoretical framework as the starting point for a critical conversation about the tangible and intangible impacts of involuntary property loss.

3 Moving Beyond South Africa: Establishing the Parameters of a Dignity Taking

4 Dignity Restoration: Remedying Property and Dignity Deprivations

1. Dignity Takings Did Occur

For many people, the emblematic example of a dignity taking is the wholesale slaughter and looting of Jews, Sinti, and Roma during World War II. Veraart (Reference Veraart2016) argues that there is incontrovertible evidence that the property theft perpetrated by the Nazis in the Netherlands and France from 1940–1945 was accompanied by the intentional dehumanization and infantilization of Jews. While this is an important and renowned example of dignity takings, there are also many others.

Throughout US history, African Americans have been subjected to dignity takings in a variety of contexts. As Brophy (Reference Brophy2016) argues, one of the most notorious examples was the 1921 Tulsa race riot. Extralegal lynchings were rampant, and the riot began because the African American community in Tulsa decided to finally take a stand against this injustice. A standoff between black and white residents over an impending lynching escalated into a riot and chaos ensued. State authorities, aided by white residents, callously destroyed the Greenwood district, which was known then as the Negro Wall Street because it was one of the most prosperous black communities in the United States at that time, with a solid professional class of doctors, lawyers, dentists, and clergy as well as multiple black-owned groceries, movie theatres, independent newspapers, and nightclubs. The visible damage was severe. White mobs razed homes, charred hospitals, demolished businesses, felled churches, and took lives. But, the intangible damage that eludes sight was even worse because African Americans were treated as sub persons and denied their dignity. Brophy (Reference Brophy2016) reports that after the riot, the denial of rights continued and the humiliation escalated when blacks were tagged like dogs and placed in concentration camps. The extreme violence perpetrated by the white community was an attempt to keep African Americans in their subordinate position, making it clear that they were not equals, had no basic rights, and thus extralegal lynchings would continue unabated. Like in South Africa, community destruction occurred as residents of Greenwood were collectively dehumanized and infantilized.

In her account of how China's rapid urbanization has resulted in the frequent displacement of rural people, Pils (Reference Pils2016) deepens our understanding of what qualifies as a dignity taking and what does not. Although all lands are in socialist public ownership and inalienable in China, private ownership of buildings (but not the underlying land) is allowed. According to rules introduced in the 1980s, urban owners can freely buy and sell their buildings, which has resulted in a real estate boom, accelerated urban expansion, and created significant demand for rural lands abutting urban areas. The Chinese government has expropriated rural buildings and lands for urban development.

Expropriation is not, however, unique to China. Eminent domain provisions in constitutional democracies allow the state to take property from owners without consent so long as it is for a public purpose and the state pays just compensation. China's expropriations may seem like a legitimate exercise of eminent domain because the state pays rural owners compensation and economic development is a valid public purpose, even by US standards. In a controversial decision, the US Supreme Court has allowed states to take private property without owner consent and give it to private-sector developers, so long as the state pays just compensation and the planned development has the potential to generate economic growth for the city (Kelo v. City of New London 2005). But, Pils argues that there are important differences. Namely, Chinese evictees lack adequate, officially recognized, and safe legal and political channels through which they can formally resist the state's decision to usurp their land and homes. This is because access to Chinese courts is generally limited (and in some cases unlawfully blocked altogether) and expression and association are severely restricted. Without accountability, state officials can run amok and, according to Pils, this is exactly what has happened in cases she has observed.

Using rich ethnographic interviews, Pils finds that Chinese citizens who resist takings are not only denied access to justice, but are also routinely infantilized and dehumanized. Rural people who resist takings are viewed as unruly, “low-quality” people who need to be educated and shown the way. As the Chinese state insists that, for the good of the nation, all citizens should forego their self-interest and accept the taking of their property, it plays the role of wise teacher and the peasants are relegated to the role of impressionable children. More insidiously, if the children do not listen, they are first pressurized and then spanked. The pressure takes many forms, but Pils argues that the most subversive are threats made against and delivered by people the resisters know. For instance, the state dispatches relatives in its employ to cajole their loved ones to stop resisting, or the state pressurizes managers to convince their subordinates to stop resisting. Just as a cruel parent denies his or her disobedient child dinner, the state has also threatened to deny the resisters' family members access to state-run schools and other state-provided entitlements. Pils reports that the most recalcitrant resisters are temporarily detained and placed in what the state euphemistically calls study classes, which are designed to reeducate communist detractors. When all these methods fail to convince rural people to stop resisting, then the corporal punishment begins. Pils interviews are replete with harrowing stories about attacks by thugs and incapacitating beatings.

Based on the South African case study, the existing definition of dignity takings requires the property confiscation to occur “without paying just compensation or without a legitimate public purpose.” Pils (Reference Pils2016) argues that even if the Chinese state pays just compensation and the taking is for the legitimate purpose of economic development, a dignity taking has still occurred because the method used to acquire the land and remove its inhabitants was dehumanizing and infantilizing. The revised definition of dignity takings produced in response to this symposium will account for this very valuable observation.

Kedar (Reference Kedar2016) examines whether Bedouins, a semi-nomadic group occupying the southern region of Israel, were subjected to dignity takings. His conclusion is, yes. The State of Israel expelled more than 70,000 Bedouins and then physically confined those remaining first to an enclosed zone under military control and then to state planned townships. There is significant evidence that the enclosures have occurred because state officials believe Bedouins are an uncivilized, savage people who require authorities to protect them from their own primitive traditions. Many Bedouins have resisted this infantilizing and dehumanizing spatial relegation by living in unrecognized or partially recognized Bedouin villages where, unfortunately, the specter of eviction and demolition are ever present.

The Bedouin case highlights how the determination of what constitutes property and who owns it provide the substance from which dignity takings are forged. Similar to the terra nullius doctrine that legally justified the dispossession of native people in some parts of the common law world, a comparable doctrine in Israel declared that nomadic Bedouins never owned the lands they occupied because agriculture was nonexistent, and thus the land was unoccupied wasteland prior to British rule. In the attempt to fit property rights as conceived by Bedouins within the narrow categories imposed by Israel's property regime, the relationship that Bedouins had to the land was intentionally disfigured, creating space for the legal nonrecognition of property rights.

This rights denial is the method by which several indigenous groups, including Native Americans, have been dispossessed. Although most Native American tribes have been subjected to dignity takings, the case of the Hopi illuminates the iterative potential of dignity takings, which is especially likely when displaced populations maintain a strong connection to the lands taken (Richland Reference Richland2016). Nuvatukya'ovi—also known as the San Francisco mountains—is a sacred site for the Hopi. Between 1879 and 1882, the federal government confiscated it and it is now run by the US Forest Service. Despite the spiritual significance of the land, the Forest Service has authorized a ski resort to operate and create snow by spraying the mountain with reclaimed wastewater. As a result, after initially losing their lands in the seventeenth century, the resort is now literally and metaphorically defecating on their sacred mountain. The indignity suffered by the Hopi was not a discrete event of dispossession, but is ongoing and ever present.

2. Dignity Takings Did Not Occur

Many times, a case will not rise to the level of a dignity taking either because there is no involuntary property loss or there was a taking but no dehumanization or infantilization was involved. Kedar (Reference Kedar2016) examines the dispossession and displacement of the Ikrit villagers—who are Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel—to assess whether dignity takings occurred under the pretense of security concerns. Kedar describes the two-step process the State of Israel used to remove the villagers. First, the Ikrit villagers lost title to their lands under the Land Acquisition Act (1953), which retroactively legalized the confiscation of property from Arabs between 1948 and 1952. To remedy this situation and to create a land regime that would support the Zionist postwar sociospatial vision, Israel nationalized most of the land in its control. The second step was displacement. Under the guise of security concerns, the Israeli military evacuated the village of Ikrit, initially promising the villagers would be able to return. When this promise failed to materialize, the villagers went to the Israeli Supreme Court, which ruled the military must facilitate their return, but the military flat out ignored the Court and proceeded to demolish the village while the Court proceedings were still pending. Despite securing a favorable judgment from Israel's highest court, even today, the Ikrit villagers have not been able to return.

In the case of the Ikrit village, there has definitely been a wrongful taking, but in order for it to rise to the level of a dignity taking, there must be evidence that the state has directly or indirectly participated in the dehumanization or infantilization of the Ikrit villagers. Kedar argues that “[w]hile the Israeli judicial system delegitimized Arabs and conceived them as radical others, enemies, or potential enemies, I doubt if this amounted to an overall dehumanization of Palestinians … I also doubt whether infantilization served as a major component in the expropriation of Arab land, except in the case of the Bedouins” (Kedar Reference Kedar2016, 883). For Kedar, the Ikrit villagers were subjected only to a radical othering that falls short of a dignity taking. The problem with Kedar's analysis is that the judicial system vindicated the rights of the Ikrit villagers and it was instead the military who disregarded their rights and dispossessed them from their lands. Determining whether a dignity taking has or has not occurred requires an analysis of the military, not the court.

Carol Rose (Reference Rose2016) explores whether or not the racially restrictive covenants, popular in the United States during the first half of the twentieth century, qualify as dignity takings. Restrictive covenants are private agreements between landowners where parties restrict the use of their land in order to benefit another's land. They are most commonly used in planned developments and monitored by homeowners associations. Negative covenants prevent owners from performing a specific act, like blocking a view, while positive covenants require owners to perform specific tasks, like paying dues or keeping the exterior of their homes or lawns up to a certain standard. Covenants are recorded in the title deed and apply to subsequent purchasers who were never party to the original agreement. The majority of racially restrictive covenants prevented whites from selling or renting their homes to African Americans (and sometimes Asians).

Rose concludes that racially restrictive covenants were not dignity takings because there was no involuntary property loss. She argues that the covenants “did not so much take a ‘thing’ as they took an opportunity to acquire a thing, a kind of a foreshadowing of a taking” (Rose Reference Rose2016, 950). Consequently, we must ask whether the concept of dignity takings should be expanded to include not only the taking of property, but also the taking of the opportunity to acquire property. Although enticing, the answer is no because the analytic power of any concept is depleted when it is stretched too far. Among the many challenges is that lost opportunities abound and while sometimes people are aware that an opportunity has slipped from their grasp, others times the loss goes totally unnoticed. Rose's contribution provides clarity: the concept of a dignity taking is a theoretical framework designed to discuss and analyze the confiscation of property rights already obtained. There may, however, be an exception as the opportunity to acquire property becomes increasingly concrete.

Using the case of coverture, like Rose, Hartog underscores the limits of a dignity taking. Coverture was a legal doctrine that, upon marriage, suspended the legal personality of a wife, giving her husband full legal authority and reneging her right to own property or enter into contracts in her own name. The husband's duty was to protect his wife who, like a child, was viewed as not having the mental acumen to control her own legal affairs. Coverture, a classic example of infantilization, was developed in Britain and disseminated to many common law nations. Until coverture gradually subsided in the late twentieth century, it was an inescapable and ordinary consequence of marriage. While Hartog argues that “several historians and legal analysts continue today to argue for the salience of coverture as what might be called a ‘dignity taking’” (Hartog Reference Hartog2016, 835), he, however, disagrees. He argues that once the matter is analyzed from the perspective of women living under coverture, it becomes clear that coverture does not qualify as a dignity taking.

For women who owned property, the act that precipitated the alleged dignity taking was marriage, which Hartog (Reference Hartog2016) argues is more accurately understood as dignity bestowing rather than dignity denying. Becoming a wife was a source of dignity and it was spinsterhood that was a source of shame. Hartog posits that marriage was a gateway to adulthood and did not trap women in a permanent form of childhood, as the language of infantilization suggests. In fact, in an exercise of autonomy, most women chose to enter into relationships where they were subordinate to and dependent on a man. Although it was possible, few women chose to remain single and keep their legal rights. Consequently, Hartog argues that the loss of property was not involuntary. Ideally, women living prior to the twentieth century would have been able to get married and maintain their legal identity and property, but coverture was an ineludible legal, cultural, and social reality prohibiting this utopia from materializing at that time. Hartog states that “marriage was understood as a privileged status. Marriage endowed a wife, gave her a dignitary identity. Coverture was one of the consequences of that privilege, of the dignities that came with marriage” (2016, 838).

Hartog may, indeed, be correct in arguing that the concept of a dignity taking is ill fit to describe the harms of coverture, but one point needs further consideration. Women subjected to coverture may have considered marriage to be a source of dignity, while also considering certain aspects of marriage to be dignity degrading—Hartog does not fully embrace this duality. The uncomfortable yet poignant example of sex work makes this duality clear. Many men and women involved in sex work may view certain lewd acts that they are paid to perform as dehumanizing, but have nonetheless chosen to continue because they have few other economic options. Paradoxically, the money that the sex workers earn can give them the ability to live an autonomous and dignified life. As such, sex work can be both dignity degrading and enhancing, just as marriage can have both qualities simultaneously. If the historical record shows that this type of dignity duality was pervasive, it is possible to view coverture as a dignity taking. Only by weighing the available evidence can we make a definitive judgment. Hartog's larger point, however, is well taken: while marriage was the proximate cause of coverture-related property takings, it was not the underlying cause. The true culprit was the invisible, constant, and normalized subordination of women, which is not well captured by the concept of dignity takings because its focus is on events of dispossession (Hartog Reference Hartog2016).

Using the case of the American Revolution, Hulsebosch (Reference Hulsebosch2016) also proposes limits on what should be considered a dignity taking. As part of the indignities tolerated during war and other atrocities, property rights are often disheveled. After tensions have cooled and the dust has settled, authorities have to decide how to move forward. After the American revolutionaries defeated the British, they were faced with the herculean task of forging a new political community. One important challenge was deciding how to deal with British Loyalists who, in the course of war, were subjected to a civil death of sorts: American revolutionary governments expropriated Loyalists' properties, annulled their civil and political rights, revoked their professional licenses, and detained and banished them.

Although Loyalists became the hated enemy, prior to the war, these men were the brothers, uncles, sons, neighbors, schoolmates, and fellow parishioners of the victorious revolutionaries. Consequently, instead of further punishing Loyalists and excluding them from the political community, Hulsebosch reports that the fledgling American nation permitted its brothers to once again rejoin the fold as equal citizens, so long as they solemnly renounced their loyalties to the British empire. While many Loyalists refused this offer, relocated to Canada or back to Britain, and stayed true to their political beliefs, most of them turned their backs on their defeated patron and reclaimed their place as full citizens in America.

Hulsebosch argues that Loyalists were not subjected to dignity takings because both the decision to become a Loyalist and then to renounce the allegiance were choices that these men had the privilege to make. Hulsebosch argues that the source of their oppression was their identity as Loyalists, which was highly malleable, and many Loyalists abandoned it when it no longer served them—a luxury many did not have. For instance, blacks forcibly removed from their homes and other property by the colonial and apartheid authorities in South Africa had no choice. As one South African so vividly put it, “I was a toothless citizen” (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a, 45). In this symposium, we learn of others who had no choice, namely, African Americans whose property was destroyed and confiscated as a consequence of the Tulsa riot (Brophy Reference Brophy2016), members of the Hopi tribe who were deprived of their native lands and then decades later forced to endure the desecration of their sacred mountain (Richland Reference Richland2016), Jews, Roma, and Sinti fleeced and exterminated by the Nazis during World War II (Veraart Reference Veraart2016), Bedouins forcibly removed from their native lands and prevented from living according to their nomadic customs (Kedar Reference Kedar2016), the Ikrit villagers summarily uprooted by the Israeli military (Kedar Reference Kedar2016), and Chinese peasants removed from their farms and made casualties of China's urban expansion (Pils Reference Pils2016).

Although Hulsebosch's observations about chosen versus ineludible identities are crucial and important, they take us down a slippery slope. If Loyalists are categorically not subject to dignity takings because they chose their identity and could just as easily choose to renounce it, then this also excludes people who are deprived of their property due to other forms of ideological or religious repression. If, for instance, religious minorities such as Coptic Christians in Egypt or Baha'i in Iran were stripped of their property and deprived of their dignity, then this is correctly called a dignity taking even though their identities are chosen and they could have avoided harm by renouncing their faith. Hulsebosch's main point, however, is not lost: for some people, the source of their oppression is an identity that they chose and can disavow at any time, while others are subjugated due to an identity that they cannot escape, and these two qualitatively different circumstances should be differentiated. But, this only means there are many different circumstances under which dignity takings occur, and not that certain categories of people cannot experience a dignity taking.

It is more productive to focus on whether people were dehumanized or infantilized regardless of their power to choose their identity. Although anti-Loyalist legislation rendered Loyalists second-class citizens, this was a form of punishment and this restriction of autonomy was not based on the state's failure to recognize and respect their full capacity to reason. So, it seems there is no strong argument for infantilization. Also, there is no evidence that the American revolutionary government failed to acknowledge Loyalists as humans. In fact, as discussed more below, because they were seen as brothers, most were allowed to rejoin the fold as full and equal members of the polity. In the end, there was no dignity taking because there was no evidence of dehumanization or infantilization.

3. Evidence Required to Determine Whether or Not a Dignity Taking Occurred

The presence or absence of the dehumanization or infantilization that forms the basis of a dignity taking is most appropriately determined through empirical interrogation. Since the dehumanization or infantilization can be either intentional or unintentional, a two-prong research strategy is required. First, scholars can perform a top-down analysis that examines the intentions and actions of the various parties responsible for the involuntary property loss. This can involve interviewing these actors as well as surveying official statements, court records, policy documents, legislation, and other documentary evidence that evinces the attitudes and positions of both the state and nonstate actors responsible for the involuntary property loss. Second, scholars can examine the intended and unintended consequences of the involuntary property loss by performing a bottom up analysis. This can entail examining firsthand accounts of dispossessed populations through surveys, interviews, oral histories, and ethnographic work, as well as analyzing second-hand accounts found in the media and elsewhere.

The case of racially restrictive covenants helps us think about the types of evidence that scholars can marshal to assess whether the taking was accompanied by intentional or unintentional dehumanization or infantilization. Rose argues that whites excluded blacks from their neighborhoods principally because whites feared neighborhood integration would cause property values to decline. It was that kind of indifference through which racially restrictive covenants inflicted dignitary harm. Meyer (2000), however, has a different perspective. In his book, As Long as They Don't Move Next Door, Meyer points out that behind the fears about property values was another major plot line: whites believed blacks were an inferior people. He claims that white resistance to residential integration was based on stereotypes that marked blacks as criminal, licentious, slum dwellers and that whites believed “African Americans preferred this ‘uncivilized’ life or, worse still, that they were racially predisposed to such a life” (Meyer 2000, 8).

While the motives of whites who created racially restrictive covenants were varied, it is important to know which perspectives were dominant. Empirical interrogation can help determine whether the intent of white homeowners was to exclude African Americans who they thought to be inferior, as argued by Meyer, or if (whatever their racial beliefs) white homeowners were primarily concerned about their own property values and simply indifferent to the affront that exclusion implied, as Rose suggests. Primary sources such as diaries, editorials, and personal letters written by white homeowners, as well as interviews and homeowner association meeting transcripts, could shed light on these important issues. Despite their different perspectives on the motivations of white homeowners, Rose and Meyer do agree that as a consequence of racially restrictive covenants, many African Americans felt dehumanized. Again, this contention is best confirmed or rejected through empirical interrogation. Most importantly, the intentions of whites who created the covenants as well as the intended or unintended impacts of racially restrictive covenants on African Americans are both equally important in determining whether the constitutive elements of a dignity taking—dehumanization or infantilization—are present.

The importance of a two-prong research approach is also highlighted by the case of the Ikrit villagers in Israel. Relying primarily on evidence from the Israeli judicial system, Kedar concludes that while there was a “radical othering,” there was no dehumanization or infantilzation involved (Kedar Reference Kedar2016, 868). A two-prong research approach requires scholars to assess the intentions and actions of the various state and nonstate actors who caused the involuntary property loss. In this case, the Israeli military is the central actor and not the court. In fact, the military blatantly ignored the constitutional court's order to facilitate the villagers' return. The military's institutional intentions can be uncovered through an examination of its official documents, statements by those in positions of authority, and interviews of those involved. In addition, scholars can assess whether dehumanization or infantilization were consequences of the involuntary property loss, which is best determined through first-hand accounts of the Ikrit villagers. The case study on the Ikrit villagers presented by Kedar is a good start, but more research on the presence or absence of dehumanization or infantilization is required.

B. Dignity Restoration

I argue that dignity restoration is the appropriate remedy for a dignity taking because it addresses the dual axes of deprivation—the loss of property and dignity. Facilitating dignity restoration is, however, often complicated by uncertainty over which individuals or groups have been affected, how they have been affected, and how much they have been affected. While these complications are sometimes used to justify a society's failure to provide a remedy for dignity takings that have occurred, this can be a morally precarious justification. Nonetheless, for those societies that do decide to provide a remedy, dignity restoration is a valuable way to think about the repair required. The following sections use the case studies presented in this symposium to test my initial conception of dignity restoration and, more importantly, to press beyond it.

1. The Contours of Dignity Restoration

To elaborate the contours of dignity restoration, Veraart examines the multiple rounds of compensation offered to Jews in France and the Netherlands after World War II (Veraart Reference Veraart2016). The first round began immediately after the war's conclusion and lasted through the 1950s. Dutch authorities formed a special institution with extraordinary powers to dispose of wartime claims. Veraart argues that since it was more focused on restoring the Dutch legal and economic system than with addressing the moral and legal harms suffered by Dutch Jews, the Dutch process shielded owners of looted property from restitution and damage actions brought by dispossessed former owners as long as current owners demonstrated that they were good-faith purchasers. When, however, the various looting institutions held their stolen assets, former owners were able to recover between 75–90 percent of the value—an acceptable sum at the time. In contrast, Veraart reports that those dispossessed in France were more likely to receive most of their property back because claims went through the normal judicial process, which was slow but effective.

Although the first round of dignity restoration transpired differently in France and the Netherlands, the legal processes in both nations transformed dispossessed populations from victims into rights-bearing citizens able to put claims before an independent and fair judiciary. Round 1 restored legal equality to people who had just been thoroughly dehumanized—an impressive feat given the times. The second round of dignity restoration began in the 1990s and the focus shifted from solely monetary remedies for individual harms to monetary and moral remedies for group harms. Veraart reports that although 75–90 percent of the value of stolen assets recovered from Dutch looting institutions was acceptable in Round 1, anything less than the full value failed to meet new demands for justice. After intense negotiations, the remaining 10–25 percent was eventually paid to Jewish institutions accompanied by a public apology, which had been absent in the first round, and this brought Round 2 to a close.

Through the case of the Netherlands and France, the mechanisms by which dignity restoration can be achieved are clarified. First, whether dignity restoration occurs or not is context specific and contingent on a host of factors such as the political and economic power of the victims, the level of political will among powerbrokers, and the zeitgeist. In both rounds of restitution, Jews were successful in obtaining some form of dignity restoration, while Roma and Sinti have received nominal monetary and symbolic compensation because they are a poor and politically marginalized group that has not been able to effectively demand redress (Woolford and Wolejszo Reference Woolford and Wolejszo2006). Second, sometimes multiple rounds of dignity restoration are necessary because prevailing political, economic, and social circumstances may not be favorable to an immediate and comprehensive solution. Third, the ultimate goal of dignity restoration may change as time progresses, conceptions of justice evolve, and material conditions shift. What is fair, necessary, or acceptable at one time may be unfair, worthless, and unacceptable under different circumstances.

To further clarify how states have facilitated dignity restoration, the case of the Tulsa race riot is critical. State authorities did not begin fashioning a remedy for property deprivations that occurred during the riot until seventy-five years later when the legislature authorized the Tulsa Race Riot Commission. In 2001, the commission's report was delivered and the legislature passed the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act, which provides funds for the economic development of Greenwood, creation of a memorial, and college scholarships for descendants of Greenwood residents. But, by Brophy's account, the state began remedying dignity deprivations that marked African Americans as sub persons within the US polity far before this time. Even though certain discrete incidents like the riot were routinely overlooked and forgotten, dignity restoration commenced when, during the course of the twentieth century, state institutions began legislatively and juridically remedying systemic group discrimination by passing legislation such as the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965), and by producing several landmark court decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The United States slowly recognized African Americans as rights-bearing citizens with a full panoply of substantive rights that they could finally defend before a court. Just as the denial of rights and full legal personhood can be dignity degrading, bestowing rights and giving people access to formal legal processes can be dignity enhancing. This legal upgrading is very similar to the first round of dignity restoration that occurred in France and the Netherlands just after the close of World War II (Veraart Reference Veraart2016).

The reintegration of Loyalists into America's young democracy stands as an important yet incomplete instance of dignity restoration because although their property was most often not restored, their dignity was. Hulsebosch writes that even after renouncing their allegiances to Britain, most Loyalists either did not receive their property, had to repurchase it, or had to pay fines. But, as the stories of Richard Harison and William Rawle highlight, Loyalists regained their ability to vote, hold office, and practice their professions. Harison and Rawle differed in many ways—they had varying degrees of Loyalism and suffered different indignities during the war—but, all the same, their political standing was restored and they were allowed to reach their highest professional potential, as demonstrated by the fact that both were appointed by George Washington to serve as the Federal District Attorney in their respective states (Hulsebosch Reference Hulsebosch2016). Although American revolutionaries did not return the properties of their Loyalist brethren, they initiated a restorative process that affirmed their agency, and restored their dignity. Unfortunately, the United States has not facilitated the restoration of property or dignity for many other groups, including the Hopi, who continue to suffer indignities today.

2. Expanding the Concept of Dignity Restoration

In We Want What's Ours, I argued that the restoration of dignity entails “rehabilitat[ing] dispossessed populations and reintegrate[ing] them into the fabric of society through an emphasis on process” (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a, 57). This definition is based on the South African case where, after centuries of exclusion, blacks demanded integration and inclusion into the polity. The Hopi case study, however, suggests that this definition requires rethinking because Native Americans have been calling for increased sovereignty and separation, not integration. Since dignity restoration is predicated upon autonomy, the concept has to make space for dispossessed peoples who are calling for both integration and separation. The revised definition of dignity restoration generated by this symposium will take this crucial point into account.

The China case also illuminates aspects of dignity restoration imperceptible in the South African case. Although agency features prominently in the concept of dignity restoration, agency is seriously curtailed in the context of a communist nation with severe limitations on speech, virtually no avenues of democratic dissent, and politically disempowered denizens. Pils argues that when formal structures make it difficult for citizens to mobilize, and thus barriers to dignity restoration are inescapable, the act of resistance itself can become a form of dignity restoration. Beyond the confines of the question of self-defense in this specific case, this raises the wider question of how, if ever, violent resistance to dignity takings can restore one's sense of dignity and moral agency and bring the sort of recognition of past wrongs that is the appropriate reaction to a dignity taking. Resistance, however, is a double-edged sword, it has the potential to restore someone's dignity or result in social ostracism, denied opportunities, physical abuse, or even death.

The case of racially restrictive covenants demonstrates that dignity restoration can also be a remedy for involuntary property loss that does not involve dehumanization or infantilization. Rose argues that although racially restrictive covenants were not dignity takings, the Fair Housing Act and other legislation that outlaws housing discrimination initiated the process of dignity restoration. In addition, the case of racially restrictive covenants helps us understand what private actors can do to facilitate dignity restoration. Rose reports that homeowners throughout the United States have found racially restrictive covenants in their deeds, reminding them of the nation's painful history. Some have expended great effort to formally renounce the racist restrictions in their deeds, even though they are inoperative. Certain states, such as California, have statutes that allow new buyers to drop racial restrictions from new deeds. Also, homeowners have entered into new covenants that declare they no longer abide by the old racial restrictions, which they name and reject. These individualized efforts have great symbolic value and effectively facilitate dignity restoration.

IV. Conclusion: Dignity Takings and Dignity Restoration—The Revised Theoretical Framework

Dignity takings and dignity restoration are sociolegal concepts I developed based on an extensive ethnographic study of South Africa's land restitution program. The eight case studies presented in this symposium elaborate and redefine the theoretical framework in important ways. They sharpen the concepts' parameters, and confirm that the concepts provide a durable and effective theoretical framework to examine involuntary property loss in diverse geographical settings and historical periods. The case studies also help establish the limits of the concepts. This concluding section presents the revised definitions of dignity takings and dignity restoration based on the insights the case studies provide.

A. Dignity Takings

I originally conceived of a dignity taking as occurring “when a state directly or indirectly destroys or confiscates property rights from owners or occupiers whom it deems to be sub persons without paying just compensation or without a legitimate public purpose” (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a, 3). While seven of the case studies suggest that this definition is durable across a range of contexts and within varying historical periods, Pils's study of the displacement of rural Chinese as a result of China's rapid urbanization suggests an adjustment is necessary. Pils argues that although the Chinese government arguably paid compensation and had a legitimate public purpose, the means the state has used to acquire these rural properties has been both dehumanizing and infantilizing. The China case helps us see that the making of sub persons is important, not whether the state pays just compensation or it is for a legitimate purpose. Accordingly, I have revised my definition of a dignity taking. A dignity taking occurs when a state directly or indirectly destroys or confiscates property rights from owners or occupiers and the intentional or unintentional outcome is dehumanization or infantilization.

In addition to refining the definition of a dignity taking, the case studies presented in the symposium have unearthed several key aspects of a dignity taking. From the case study on coverture (Hartog Reference Hartog2016), we come to understand that dignity is not an on/off switch; instead, acts or institutions can be simultaneously dignity degrading and dignity enhancing. Without close examination, a dignity taking can quietly lurk behind this duality, hiding in plain sight. The case studies on takings from the Bedouins in Israel and the Hopi people lay bare the origins of many dignity takings—the determination of what constitutes property and who owns it (Kedar Reference Kedar2016; Richland Reference Richland2016). In a game of legal smoke and mirrors played by many conquering nations, property confiscation is rendered invisible through the claim that the conquered never owned the property in the first place.

While the symposium has shown that a dignity taking is a conceptually sound and useful theoretical framework, the symposium has also exposed the limits of this concept. As Rose highlights in her study of racially restrictive covenants, dignity takings only apply to the confiscation of property and not to the taking of a more nebulous opportunity to acquire property. Another limitation is revealed by Hartog's case study on coverture. Although it is within reason to describe a wife's expunged property rights as a dignity taking, this declaration may not bring conceptual clarity to the situation. Instead, as Hartog suggest, focusing on the event of dispossession may draw attention away from the larger, more invidious problem—the invisible, constant, and normalized oppression of women. Similarly, as Richland shows in his study of the Hopi, when property rights are slowly eroded and the dispossession is ongoing, focusing on a singular event of dispossession can obscure the iterative nature of the harm involved. In many cases, the dignity takings framework and its focus on discrete instances of involuntary property loss can bring conceptual clarity to messy realities, but not always.

Sometimes it is readily apparent that the involuntary property loss was accompanied by dehumanization or infantilization, but as the cases of racially restrictive covenants and takings from the Ikrit villagers of Israel exhibit, other times it is not so clear. Establishing whether or not a dignity taking exists requires empirical interrogation, and scholars must find reliable evidence of the intentional or unintentional dehumanization or infantilization of an individual or group. Evidence clarifying the dignity degrading intent or actions of the dispossessing parties or the impact of the involuntary property loss on its victims can come from diverse sources such as interviews, surveys, policy documents, laws, judgments, official statements, diaries, meeting transcripts, editorials, or ethnography.

B. Dignity Restoration

Based on my work on South Africa, I defined dignity restoration as “compensation that addresses both the economic harms and the dignity deprivations involved” (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a, 4), and its purpose is to “rehabilitate dispossessed populations and reintegrate them into the fabric of society through an emphasis on process” (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2014a, 57). The Hopi case, however, demonstrates that some victims of dignity takings are not demanding integration, but call instead for separation and sovereignty (Richland Reference Richland2016). Since dignity restoration is about allowing dispossessed individuals to have significant say in how they are made whole, an adjustment in the definition is necessary to account for the different routes to restoration that they may choose to take. Accordingly, I have refined my definition of dignity restoration. I now define it as a remedy that seeks to provide dispossessed individuals and communities with material compensation through processes that affirm their humanity and reinforce their agency.

The symposium has provided an expansive view of the power and purpose of dignity restoration, which can take many forms. In some cases, while the particular act of property confiscation may go unaddressed, the society upgrades the dispossessed from sub persons to rights-bearing citizens protected by the legal system and its formal processes. This juridical and legislative upgrading can remedy the systemic group harms that led to the dehumanization and infantilization at the core of a dignity taking. For instance, after World War II, France and Netherlands restored the legal personhood of Gypsies and Jews in the first round of reparations (Veraart Reference Veraart2016); the Supreme Court ruled racially restrictive covenants unenforceable in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) and legislators put in place prohibitions on housing discrimination (Rose Reference Rose2016); coverture was repealed and the legal structures that kept women subordinate to men have been slowly eviscerated (Hartog Reference Hartog2016); and during the course of the twentieth century, the United States began recognizing the civil rights of African Americans and they have gradually overcome the de jure segregation, extralegal violence, and racial oppression that caused the Tulsa race riot.

The symposium has demonstrated that dignity restoration is context specific. The occurrence of dignity restoration is contingent on several factors, such as the political and economic power of the victims, the level of political will among powerbrokers, and the zeitgeist. When dignity restoration does happen, it can include individual or group redress. For instance, after World War II, the first round of compensation in France and the Netherlands was focused on individuals while subsequent rounds focused on collective harms (Veraart Reference Veraart2016). Dignity restoration can also take the form of material or symbolic redress. The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act (2001) provides monies for Greenwood's economic development and college scholarships for the descendants of Greenwood residents, as well as the creation of a memorial (Brophy Reference Brophy2016).

There are many ways that the timing of redress can unfold, if it happens at all. When the political, economic, and social circumstances are not conducive to an immediate and comprehensive solution, dignity restoration can occur in multiple rounds, as witnessed in France and the Netherlands (Veraart Reference Veraart2016). When there are multiple rounds, the objective of dignity restoration may evolve as ideologies and constraints change over time. Also, as in the case of the Tulsa race riot, dignity deprivations were addressed before property deprivations (Brophy Reference Brophy2016). Sometimes, the reverse occurs. Other times, only property or only dignity deprivations are addressed. For instance, even though the property of most Loyalists was never restored, so long as they renounced their allegiances to Britain, the nascent American nation allowed its brothers to rejoin the political community as full and equal members, which allowed former Loyalists to even obtain prized political appointments in the incipient democracy.

Dignity restoration can be state driven or initiated by nonstate actors. In China, for instance, Pils (Reference Pils2016) argues that state repression is so acute that the act of resisting the dignity taking itself can be a form of dignity restoration, albeit a precarious one because it could be restorative or result in further degradation. In addition, Rose (Reference Rose2016) explains that many US homeowners who have found racially restrictive covenants recorded in their deeds have expended great effort to renounce these racist restrictions. Although these declaratory acts are purely symbolic because the racist restrictions no longer have legal effect, they are a solid example of how nonstate actors can facilitate dignity restoration. Lastly, as the case of racially restrictive covenants shows, dignity restoration, while primarily a remedy for dignity takings, is also an effective remedy for involuntary property loss that involves humiliation and degradation, but not dehumanization or infantilization.

C. Future Research

The existing literature on involuntary property loss is scattered in various disciplinary journals. Although involuntary property loss has been a pervasive phenomenon, there are no prominent theoretical frameworks that scholars can use to have a coherent interdisciplinary conversation about this important topic (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2016). The dignity takings framework provides a common vocabulary to describe and analyze takings that involve the loss of property and dignity. Likewise, the dignity restoration framework carves out intellectual space to reimagine the possibilities of redress. This Law & Social Inquiry symposium is just the beginning of a larger, interdisciplinary conversation about takings and the remedies required. Other scholars have already begun to use the dignity takings and dignity restoration frameworks to further examine instances of involuntary property loss in various contexts around the globe and in different historical periods.

Acevedo (Reference Acevedo2016) explores the ideas of dignity takings and dignity restoration in the context of police misconduct, specifically examining police violence against African Americans and the remedies required. In the spring 2017 issue of the Chicago-Kent Law Review, anthropologists, lawyers, sociologists, political scientists, historians, and education specialists will use disparate cases of involuntary property loss to empirically explore the concepts of dignity takings and dignity restoration in four specific contexts: criminal punishment, labor relations, individual property, and collective property. First, since there is sometimes a very thin line between legitimate punishment and an illegitimate dignity taking, scholars clarify which forms of criminal punishment qualify as a dignity taking and what type of dignity restoration may be required. The cases explored are the hidden sentences of criminal punishment (Kaiser in press), criminal punishment in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Acevedo in press), and the Chicago police torture reparations ordinance (Baer 2017). Second, using the case studies of American chattel slavery (Henderson in press), unpaid wages to undocumented citizens (Rosado in press), and dangerous work conditions that cause bodily injury and fatalities (Nadas and Rathod in press), scholars investigate when and how dignity takings arise in the context of labor relations and whether dignity restoration is required. Third, a variety of mechanisms have been used to dispossess people of their individual property rights all over the world, and some may qualify as dignity takings that require dignity restoration. Colombia's ongoing civil war has displaced millions of its citizens (Guzmán-Rodríguez in press); tax discrimination led to massive tax foreclosure and displacement in the US (Kahrl in press); property has been damaged and destroyed in the West Bank and Gaza Strip by the Israeli military (Bachar in press); and Iraqi Kurds have been subjected to multiple waves of displacement under both Hussein's Baath regime and ISIS (Albert in press). Fourth, just as individuals have been dispossessed, communities have also been deprived of important collective property. This is evident in the case of the closure of King-Drew Hospital in Los Angeles (Ossei-Owusu in press), the shuttering of gay bathhouses in New York at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Engel and Lyle in press), the controversial closure of public schools in Chicago (Shaw in press), the demolition of Japantown in Sacramento due to urban renewal (Joo in press), and the unconsented taking and transformation of the Native American image into a savage mascot used by many sports teams (Phillips in press).