Introduction

From the “tough on crime” rhetoric of politicians to the everyday activities of corrections staff and law enforcement, mass incarceration has come to occupy a central place in modern American life. Research on this punitive turn describes the principal actor as an out-of-control, swollen, and invasive state. Even accounts that critique the penal state for posturing to maintain the illusion of control where there is no meaningful ability to control crime focus on the penal state's centrality in driving mass incarceration (Garland Reference Garland2001a; Wacquant Reference Wacquant2010aa). Indeed, comparative studies often conclude that the apparatus the U.S. government has developed to “monitor, incarcerate, and execute its citizens” marks it as a strong state (Gottschalk Reference Gottschalk2006, 236). Driving this punitive trend is a societal shift toward the use of expressive, victim-oriented justice to combat newly salient fears of the criminal “other”; David Garland (Reference Garland2001a, Reference Garland and Garland2001b) termed this new order the “culture of control.”

Much of the extant literature portrays an overbearing penal state that is hyperpresent, constraining every aspect of criminalized people's lives. Research has shown that mass incarceration policies involve an unprecedented reach of the carceral state into schools, homes, workplaces, neighborhoods, and routines of everyday life (Garland Reference Garland2001a; Simon Reference Simon2007; Gottschalk Reference Gottschalk2009). An increasing part of the literature does analyze penal interventions besides incarceration. Much of the literature's central focus, however—and therefore the analytical starting point of many studies—is the carceral state, with its delivery of formal punishment (such as incarceration, probation, parole, and mandated treatment) and its control of marginalized people's lives through this punishment. As Marie Gottschalk (Reference Gottschalk2015, 256) demonstrated in discussing the “prison beyond the prison,” people with felony convictions are ensnared in a “web of controls that stretches far beyond the prison gate.” Extending Gottschalk's critical gaze, this article analyzes the mechanisms through which state intervention limits the opportunities and impacts the circumstances of criminalized people in ways that surpass or act independently of mass incarceration and formal punishment. The penal state reaches beyond carceral confinement and the well documented iterations of this confinement through civil laws and regulations, bureaucratic operations, and for profit and nonprofit nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

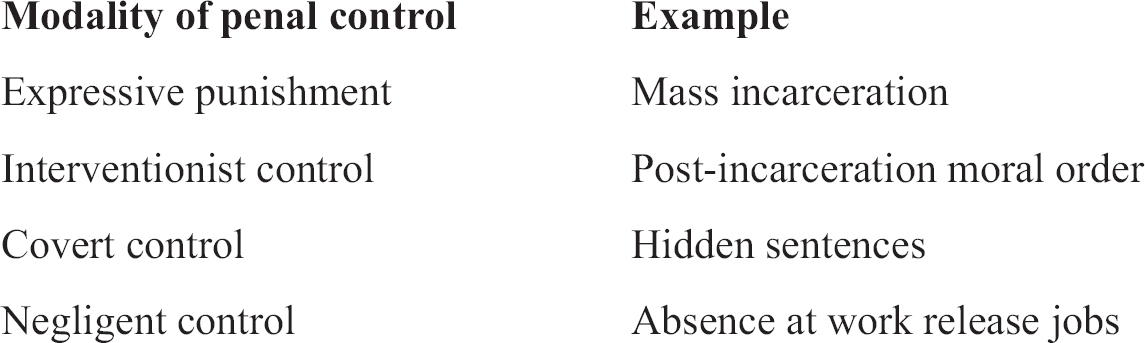

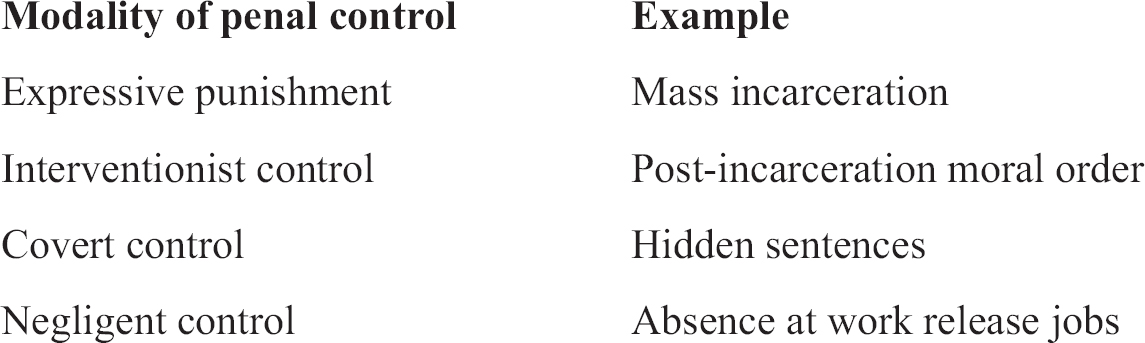

Rather than asking how the penal state punishes, we ask how it controls; this redirected focus facilitates a more nuanced understanding of how the penal state operates in intentional and unintentional ways. Footnote 1 We highlight and examine four modalities through which the state controls criminalized people's lives, although these modalities may not be exhaustive. First, expressive punishment refers to the ways in which penal officials operate legally, at the surface of public knowledge, and through committed acts. We juxtapose expressive punishment as a modality with three additional modalities that emerge from the data: interventionist penal control functions through deep, extralegal interventions into the lives of criminalized people; covert penal control operates in a submerged fashion beyond expected, formalized sentences; and negligent penal control occurs when the state withholds action that is needed to protect the well-being of people for whom it is responsible.

The cases in this article demonstrate the latter three modalities of penal control. The post-incarceration moral order (Rumpf Reference Rumpf2014) that correctional agents require women to follow after release illustrates interventionist control; the hidden sentences (Kaiser, forthcoming) that accompany more visible punishment illustrate covert control; and policies responding to the injury of incarcerated people at work release jobs illustrate negligent control. Together, these cases comprise a penal control framework that shows how the state operates in broader and more varied ways than is commonly recognized in analytical or reform-oriented discourses. The contemporary US penal state is not merely a punitive apparatus but rather a broader governmental frame that permeates and organizes social life in multiple ways.

The Controlling State

Scholarship on penal control maintains a focal point around carceral, expressive punishment, or official responses to lawbreaking that are delivered or threatened by governmental actors (see Austin [1832] Reference Austin1968; Walker Reference Walker1991). The contemporary penal state is conceptualized as the center of a populist, politically driven “culture of control,” seeking to preserve the rhetorical illusion of maintaining control of crime, even when the expanding infrastructure becomes unsustainable and disconnected with actual crime control (Garland Reference Garland2001a; Bell Reference Bell2011). This discourse describes a penal state that is overtly and increasingly punitive on all fronts, constantly seeking expressive justice via incarceration, parole, fines, and other punishments (Beckett and Sasson Reference Beckett and Sasson2000; Whitman Reference Whitman2003; Western Reference Western2006).

As we analyze the power of the contemporary penal state, we turn a critical gaze onto a wider realm of situations. The overwhelming state control in the lives of criminalized people—those who are labeled and treated as criminal—occurs to a degree to which they and the general population may not expect or recognize. The state often controls and constrains without explicitly stated or well formulated intentions of doing so, but rather through direct intervention and implications of its policies.

To extend this critical gaze, we build upon research that has highlighted several examples of this control: intergenerational social exclusion produced by incarceration (Foster and Hagan Reference Foster and Hagan2007), stratification and the reduced life chances of incarcerated African American men with low levels of educational completion (Western Reference Western2006), the “death by a thousand cuts” of poor communities with high rates of incarceration and high rates of return from incarceration (Clear Reference Clear2007), the surveillance of community members by law enforcement (Gottschalk Reference Gottschalk2015), the enactment of state violence on citizens (Richie Reference Richie2012), and the development of mass incarceration as a system of racial control (Alexander Reference Alexander2010). Whereas this research is often motivated to investigate the extended harms of mass incarceration and expressive punishment, we shift our focus directly to these other forms of penal control as important and operational in their own right. This analytical shift allows us to draw upon the new wave of scholarship on penal control besides incarceration while also going a step further to conceptualize these forms of control.

We use penal state to refer to the punishing arm of the government, consisting of corrections departments, courts, law enforcement, and legislatures. The work of the penal state is not limited to criminal sentences but crosses into civil law, and need not be performed by governmental employees. Research on governance and the mixed economy has shown that the boundaries and definition of the penal state are ambiguous: various nongovernmental parties now act in the state's name and function as part of the penal state as they work with criminalized people (Hannah-Moffat Reference Hannah‐Moffat2001; Maurutto Reference Maurutto2003; Haney Reference Haney2010; Miller Reference Miller2014). Whether by granting direct funding or making community members responsible for work without supplying direct funding, states have delegated this work to nongovernmental actors (NGOs, or organizations without governmental employees) (Marwell Reference Marwell2004). Following work on the appropriation of the power to punish by for-profit corporations (e.g., Hallett Reference Hallett2006, Burkhardt Reference Burkhardt2011), we are concerned with the role of for-profit companies that absorb responsibilities that would otherwise be held by the penal state. We are also concerned with nonprofit NGOs, which are increasingly involved in policy implementation through public–private partnerships (Haney Reference Haney2010). Defining the penal state broadly allows us to focus on a range of actions that surpass the role of the state as punisher—the source of prohibitions and sanctions—by involving “productive” uses of power (Hannah-Moffat Reference Hannah‐Moffat2001).

As we shift the focus beyond governmental actors, we also conceptualize penal control more broadly than punishment. An expressive punishment framework obscures the full range of ways in which the penal state exerts control beyond the confines of carceral settings and imposes punishments, and the ways in which these methods of control are felt and experienced by criminalized people. As Katherine Beckett and Naomi Murakawa (2012) have shown, civil and administrative law, and not only criminal law, have enabled mass incarceration. Providing examples such as legal financial obligations and the administrative back-end sentencing process of parole revocation, Beckett and Murakawa (Reference Beckett and Murakawa2012, 222) stated that “criminal law and criminal justice institutions increasingly represent only the most visible tentacles of penal power.” Yet even this astute observation of these “subterranean” forms of control beyond criminal courts does not fully encompass the scope of the penal state's power over criminalized people, which extends far beyond interactions resulting in incarceration in prison and jail (Beckett and Murakawa Reference Beckett and Murakawa2012, 223). Drawing on Cohen's (Reference Cohen1985) definition of social control, we define penal control as the way the state or more autonomous professional agents direct individuals who have been defined as criminal or problematic. Thus, penal control includes “not just the obviously coercive apparatus of the state,” but also the actions of those whose work is aligned with state policy, or as Cohen (Reference Cohen1985, 2) explains, the “putative hidden element in all state-sponsored social policy.”

Modalities of Penal Control

The term modalities of penal control identifies distinct strategies of governing criminalized people that are closely tied to the penal state (Hudson Reference Hudson1998; Hannah-Moffat Reference Hannah‐Moffat2001). For example, in a study of reform in Canadian women's prisons, Hannah-Moffat (Reference Hannah‐Moffat2001) found that governing bodies encouraged the use of strategies of empowerment and motherhood at different moments in penal history; these strategies employed distinct technologies and assumptions about femininity and agency. As this research on governance has shown, a broad range of actors may execute these modalities, and multiple forms of governance can operate simultaneously. The framework developed in this article thus recognizes the dynamic involvement of the penal state in the lives of criminalized people across multiple forms of intervention.

This analysis identifies three modalities of penal control beyond expressive punishment (Figure 1). First, the penal state engages in interventionist control by enforcing a post-incarceration moral order through parole and probation stipulations, drug treatment mandates, and relationships with recovery homes. Second, the penal state uses covert control by imposing a vast web of hidden sentences implemented behind the scenes by various judicial, legislative, and administrative actors. Third, the penal state employs negligent control through absences in protecting the well-being of criminalized people under its care.

Figure 1 Modalities of Penal Control.

The Interventionist Modality

It is crucial to recognize the productive, rather than merely repressive, use of power to achieve social control of criminalized individuals, both inside and outside the formal legal system. As Nikolas Rose and Mariana Valverde (1998, 546) asserted, “the workings of law are always intermixed with extra-legal processes and practices.” While the penal state is hyperpresent in criminalized people's lives because of legal sanctions, its involvement extends beyond these sanctions via heavy surveillance by the state or its proxies in the nongovernmental sector.

A growing body of ethnographic research has revealed how prisons and therapeutic drug treatment programs run by nonstate actors govern poor individuals and people of color (e.g., McKim Reference McKim2008; Kaye Reference Kaye2010, Reference Kaye2012; McCorkel Reference McCorkel2013). Teresa Gowan and Sarah Whetstone (2012, 70) referred to this type of arrangement as “strong-arm rehab,” and described it as “a particular type of court-mandated rehabilitation emphasizing long residential stays, high structure, mutual surveillance, and an intense process of character reform.” The authors argued that such treatment programs are “in the business of constructing … brand-new people” (Gowan and Whetstone Reference Gowan and Whetstone2012, 80). Similarly, Jill A. McCorkel (Reference McCorkel2013, 12) illustrated the advent of “habilitation” treatment in a women's prison, premised on the notion of criminalized women's “incomplete, flawed, and disordered” selves that “must be ‘surrendered’ to a lifelong process of external management and control.”

These and similar studies have built on Michel Foucault's (Reference Foucault, Burchell, Gordon and Miller1991) concept of governmentality and Rose's (Reference Rose1999) work on therapeutic governance. They have shown how drug treatment programs rooted in the therapeutic community model encourage participants to recognize their weak control of flawed selves as the core problem, one that they must address by developing new, disciplined selves capable of regulating their desires. While the research on strong-arm rehab and therapeutic communities addresses punishment and control, the literature focuses primarily on formal periods of correctional supervision, during which an explicit form of punishment is administered.

Building on this work, the concept of the post-incarceration moral order developed by Rumpf (Reference Rumpf2014) describes the way that the state and NGOs direct criminalized people to certain sites and ways of being. This moral order includes the distinct, highly regulated expectations and norms that criminalized people encounter outside explicit state sites and that carry consequences that extend far beyond periods of expressive punishment.

The Covert Modality

State interventions and goals vary from open and explicit to murky, unclear, or entirely unrecognized. Mass incarceration can be understood as the tip of the iceberg of penal policy, the exposed part that is publicly salient but is actually only a small portion of a far broader regime of penal control, much of which is submerged.Footnote 2 In the obscured portion of this regime, the penal state controls covertly, implementing policy in ways unanticipated by, and unknown to, most societal actors.

The most instructive examples of covert control are provided in Kaiser's (forthcoming) research on hidden sentences, or punishments that are legally imposed by the state as a direct result of criminalized status but are not implemented as part of a formal sentence by a criminal law judge. Examples include bans from public housing or loss of pension and Social Security benefits; tens of thousands of such restrictions and requirements can be identified during, before, and after formal supervision, and they typically last until death. These punishments are (actively) hidden in the legal system in a variety of ways: (a) through their sheer scope; (b) by their dispersal across and within federal and state constitutions, civil and criminal codes, administrative rules, and judicial decisions; (c) by the massive variation in types of triggering offense, active stages in the penal process, discretionary grants or lack thereof, potential relief, and other dimensions; and (d) by the lack of legal requirements for judges and attorneys to know, give notice of, or actively consider hidden sentences at any time (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2016a). Because these hidden sentences are usually buried in nonpunitive laws (e.g., restrictions on drug offenders' access to public housing are found in subsections of various housing codes; see Ewald Reference Ewald, Sarat, Douglas and Umphrey2011), they are obscured publicly as well as legally. This obscurity means that hidden sentences are rarely noticed by criminalized people, media, and other actors.

The hidden nature of these forms of penal control is especially remarkable. Gottschalk (Reference Gottschalk2015) and Michelle Brown (Reference Brown2009) have remarked on the troubling distance between the general public and those residing in prisons, which is facilitated by privilege and social distance, restrictive visiting policies, distorted entertainment purportedly showing prison life, and systematic biases in data collection on health and well-being that exclude incarcerated people. Many of the consequences of the carceral state's growth, Gottschalk (Reference Gottschalk2015, 242) concluded, are “invisible to the wider public but are keenly felt by released prisoners, parolees, probationers, their families, and their communities.” Andrew Dilts's (Reference Dilts2014, 202) historical and theoretical analysis on criminal disenfranchisement identified voting sanctions as one part of a vast, “increasingly buried and invisible legal structure” that accomplishes deep political exclusion of many kinds of people deemed unworthy for citizenship.

Scholars examining the expansion of probation, parole, and monetary sanctions have revealed an array of hidden punishment that is both vast and ubiquitous, legally structuring every aspect of formal supervision and post-release life (Harris, Evans, and Beckett Reference Harris, Evans and Beckett2010; Phelps Reference Phelps2013; Miller Reference Miller2014). Restrictions varying from limitations on due process and other constitutional rights to termination of parental and marital rights affect people who are incarcerated and under correctional supervision (Fliter Reference Fliter2001). In addition, post-release penalties (often called collateral consequences) range from voting restrictions and registration requirements to driver's license revocation and vast numbers of employment bans (Demleitner Reference Demleitner1999; Manza and Uggen Reference Manza and Uggen2008). This scholarship has analyzed pre- and post-release sanctions under the rubric of expressive punishment, and thus portrays them as side effects of penal state action. These hidden sentences, however, are an integral part of penal control and how it is experienced during, after, and independent of expressive punishment.Footnote 3

The Negligent Modality

Recent work has focused on the specific actions taken (as distinct from omitted) by the state: jailing those who have been arrested, warehousing incarcerated people, and restricting access to kin through long distances between prison and home. For example, Alice Goffman (Reference Goffman2009) described the hyperpresence of the penal state across sites criminalized people travel, as epitomized by police running names at a hospital to check for people with active warrants. This scenario suggests an Austinian view of law: the state is sovereign, the sovereign treats laws as commands (expressions of a wish for compliance), and the state enforces these laws by threatening transgressors with violence (Austin [1832] Reference Austin1968; Rose and Valverde Reference Rose and Valverde1998). This view of the state represents the expressive punishment framework well.

Although much of the discourse assumes that the state continually works to carry out its stated mission to punish in response to lawbreaking positively (through completed acts), state actors are also involved through their absence or failure to fulfill all of their obligations to protect the safety and well-being of incarcerated people. As the state's capacity for carceral functions grows, the state thins and becomes overly stretched (Garland Reference Garland2001a). One of the consequences is the creation of what Jonathan Simon (Reference Simon2014, 130) terms “spaces of neglect” in which penal state actors fall short of their obligation to care for people in their custody, such as the case of overcrowded prisons and inadequate health care for incarcerated people in California.

We develop a social scientific understanding of negligent penal control as a phenomenon encouraged by the thinning and overstretching of the state.Footnote 4 Corrections departments routinely offload onto third parties a range of responsibilities and risks, from the running of support groups to the operation of entire prisons (Haney Reference Haney2010; Miller Reference Miller2014; Kaufman Reference Kaufman2015), and the arrangements are not always contractual. Even when these arrangements comply with statutes and regulations, criminalized people are impacted and controlled when the penal state is absent.

In the following sections, we analyze these three modalities of penal control and their significant consequences for criminalized people's freedom, opportunities, rights, and self-definitions. Cases from three distinct data collection projects are the basis for analysis of each of the modalities. Together, these cases add nuance to the extant literature on penal control, which has remained within the bounds of the punishment framework—a framework constrained by its unquestioning emphasis on expressive punishment.

Methods and Data

The data for this article come from three separate projects conducted by each individual author. At the outset of these projects, each of us was committed to investigating how the penal state structures the lives of socially marginalized people. We began each project with distinct research questions that called for different methods. Rumpf's data come from qualitative interviews with criminalized women; Kaiser's focus is case law, statutes, and related historical documents; and Kaufman uses governmental documents, news reports, ethnographic observations, and administrative laws. Each distinct study is unified by the shared goal of developing a nuanced understanding of how the penal state operates and through what mechanisms. We use pseudonyms to refer to the names of people who took part in the research projects; however, we note when we use the real names of people, agencies, courts, and companies that are widely available on the public record.

As researchers studying related questions, we shared our analyses and findings. We realized that a common thread across our studies is that the concept of punishment did not fully capture what we were seeing. As we shared our work with one another, we began to see that our research collectively speaks to the unifying question of how the penal state controls. The complexity and extent of penal control that our data collectively reveal surpass what any of our projects could produce alone. Together, our cases show how the penal state reaches deeper into people's lives, for longer periods of time, and with longer lasting consequences than any of us individually anticipated.

First, we operationalize interventionist penal control as the work the penal state achieves through NGOs; this control may entail directing criminalized people to programs before and after release from incarceration, managing their lives within and beyond jails and prisons, and influencing the programmatic approaches adopted by NGOs. Of course, interventionist penal control likely operates through additional types of organizations as well as through governmental actors.Footnote 5 In addition, not all NGOs that offer assistance to formerly incarcerated women necessarily engage in interventionist penal control, although given the mounting research documenting the ways in which “helping” organizations reinforce neoliberal discourses of personal responsibility, it is difficult to imagine how such an organization could operate truly independently of the penal state (McKim Reference McKim2008; Haney Reference Haney2010; Hackett Reference Hackett2013; McCorkel Reference McCorkel2013).

The current analysis of interventionist penal control is based on data collected by Rumpf, who recruited thirty-six formerly incarcerated women from four community-based organizations in Chicago, Illinois.Footnote 6 She conducted ninety-nine in-depth, semi-structured qualitative interviews and photo-elicitation interviews (PEI), based on participant-generated photographs. Participants took photographs to help tell their stories of criminalization, incarceration, and post-incarceration. For the PEIs, participants selected which photographs they wanted to discuss in which order and reflected on what each image communicated. Chicago is remarkable because of the considerable Second Chance Act support for NGO-administered programs (Miller Reference Miller2014), the implementation of small-scale, realignment-type policies through new early release programs, the closure of a supermax and a women's prison, and other overcrowding reforms (see John Howard Association n.d., 2012). This policy landscape encourages the type of interventionist penal control we analyze, as illustrated by the prevalence of twelve-step programs offered during incarceration, provided at recovery homes, and required by judges.

Second, historical data on covert penal control are drawn from Kaiser's data on the rise of hidden sentences in the United States. Kaiser sought to collect data on all hidden sentences, using a combination of publicly available databases and secondary data sources covering legislative, judicial, and media accounts of hidden sentences. Hidden sentences can come from legislative and administrative codes and judicial rulings, state or federal, that implement a sanction based on some form of criminalization; these laws can become active based on conviction, sentencing, or imprisonment but also upon indictment, arrest, or even simply committing a prohibited act. Various decision makers, from judges to hiring businesses, determine criminalized statuses, but each decision maker has discretion or is mandated to take action by a judicial or legislative declaration.

Data surrounding two judicial cases that occurred in the 2000s, concerning prisoners' access to civil court and sex offender registration, are of specific concern. Data for these cases are drawn from court decisions and appeals, case filings of the plaintiffs and defendants, supporting case documents, relevant statutes, and bill files and other documents pertaining to that legislation. These cases represent broader trends in hidden sentences, for which there are thousands of little-known examples. However, it is instructive to apply the penal control framework to cases like these that are familiar but have been considered examples of side effects of punishment, rather than penal control itself.

Third, we illustrate negligent penal control using Kaufman's data from Wisconsin. This state's policies exemplify the way in which the penal state encourages partnerships with community-based actors while transferring both risk and responsibility away from the state (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2014, Reference Kaufman2015). The mission statement of the Wisconsin Department of Corrections (WDOC) stresses that the agency will “partner and collaborate with community service providers and other criminal justice entities” (WDOC n.d.). The offloading of responsibilities and care for criminalized people to third parties raises the possibility for negligent control to occur. Here we highlight the implications of the absence of the WDOC at work release job sites.

While Kaufman was collecting interview and observational data at NGOs that serve formerly incarcerated people in Milwaukee County and Dane County,Footnote 7 she learned of an instance of a workplace injury of a former inmate on his previous work release job. Knowledge of this situation initiated more research on policies that allow companies to hire people on work release to perform work outside of the correctional setting. Examining these types of situations drew our attention to how the role of the WDOC in the work release arrangement is governed through statutes and administrative rules regarding prison labor, worker's compensation, the state's purchase of services, and workplace hazards. We rely on Wisconsin statutes and administrative laws, WDOC agreements and purchasing documents, press releases and reports from the US Department of Labor's Occupational Health and Safety Administration, and local news reports.

Interventionist Penal Control

The penal state intervenes in criminalized people's lives in part by guiding them toward settings in which they must engage with a discourse of moral transformation. In examining how the state guides formerly incarcerated people toward personal transformation, we analyze what Rumpf (Reference Rumpf2014) terms the post-incarceration moral order. As Rumpf (Reference Rumpf2014) showed, formerly incarcerated women do not reintegrate into the larger moral order that governs society, but rather encounter a moral order specific to the post-incarceration experience (see also Wacquant Reference Wacquant2010bb; Bumiller Reference Bumiller, Carlton and Segrave2013). This moral order imposes high levels of surveillance and regulation on women through the stipulations of probation and parole (such as wearing an electronic monitoring device) and through the rules and requirements of recovery homes and reentry programs (such as meetings, support groups, individual counseling, vocational programs, remedial/high school/GED classes, and drug treatment). This analysis identifies the experiences of penal state involvement that is both legal and extralegal, due to the roles of probation and parole agents and recovery home workers.

The Interventionist State at the Recovery Home

The supportive recovery home programs women encountered after their release from prison stood in opposition to the explicitly punitive arms of the criminal legal system (Haney Reference Haney1996, Reference Haney2010). Staff members at these programs largely recognized the criminal legal system as unfairly targeting low-income and poor women of color and prison as a traumatic experience that further disadvantages women. Yet these programs worked alongside the criminal legal system as evidenced by funding streams and relationships with people in the system, such as judges and parole agents. Because the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) paid for some residents' rent at recovery homes, residents had on-site meetings with parole officers, and information was shared between recovery home staff and parole officers, these homes became sites of state surveillance.

The penal state also had a more indirect influence on NGOs' service approach. As independent organizations, the NGOs were free to determine their service approaches, such as using a harm-reduction rather than an abstinence-based approach to drug treatment. One director explained, however, that NGOs adopted an abstinence-based model, in part, to provide women with consistency in dealing with the multitude of state institutions that regulate their lives, including parole and child protective services (CPS). These NGOs extended the dominant twelve-step and religious discourses that women encountered while incarcerated (Rumpf Reference Rumpf2014). In these ways, reentry programming operated as an extralegal form of penal state involvement that ultimately advanced a more lasting version of the criminal legal system's framework linking women's drug use, criminality, and moral worth.

Recovery in the Post-Incarceration Moral Order

Every recovery home that women discussed had institutionalized twelve-step meetings into their programming as part of their emphasis on recovery from drug use. Red's case illustrates the interlocked control of the state corrections officials supervising her release and the recovery home where she lived—in other words, the intersection of legal and extralegal penal state involvement in her life. Red is a forty-one-year-old Puerto Rican woman who had been living at Starting Again (a recovery home) since her release from prison (about four months prior) and was on electronic monitoring. As was common among recovery homes, Starting Again required women to attend a minimum number of twelve-step meetings and to submit proof of their attendance to the director. Red took a photograph of one of her meeting attendance sheets and indicated that submitting it to the director was sometimes stressful, particularly on the three separate occasions when she lost her sign-in sheet. She explained what she did the last time she lost it:

I make it up real quick and go to the person that was chairing [the meeting] … . And I'm like, “You remember my face? Right? I was here and I lost my sheet.” And they'll re-sign it. So … I always got saved, I always saved my life. But if the person, like, doesn't want to do it or all of a sudden that person's not chairing anymore … she [Starting Again's director] could take us out for it, too … . Because you never know what people are fed up with.

Red indicated the extreme influence this document exerted over her life. Her word choices, “saved my life” and “could take us out,” revealed how much she needed the recovery home. She equated losing her spot in this home with death. Her comments were not hyperbolic given the hardships Red had faced, including drug use, domestic violence, mental illness, her mother's death, losing her children to child protective services, and incarceration. Red described Starting Again as a beautiful place where she felt that people cared for her and were concerned about her well-being. Losing this support and shelter would have been devastating. She had nowhere else to turn. Thus, the sign-in sheet was tremendously important.

The recovery home rules helped Red make sure she simultaneously met her parole requirements, such as twelve-step meeting attendance, while participating in recovery home programming. Yet by directing her to the recovery home, the prison's field services unit set in place a situation in which Red's housing, not just her parole completion, depended on her participation in twelve-step meetings. The penal state, recovery home, and even twelve-step meeting attendance were intertwined in Red's life. When these types of involvement converged, the intrusiveness of the penal state could be overwhelming.

In addition to establishing written documentation, recovery homes also monitored women's recovery processes by administering random urine tests to detect whether residents had used drugs recently. Jean, a 20-year-old Black woman who had never been to prison but was on probation, vividly captured this surveillance with her photograph of a box of “drop cups” on the counter at Growing Stronger, the recovery home where she stayed. Staff members used the cups to collect a urine sample and conduct a drug test. Jean explained that if a resident tested positive, the staff members might terminate her stay. Just seeing the box of drop cups on the counter negatively affected her. Reflecting on the picture, Jean explained:

Word'll pass that we're being dropped today. And … it's like if I've made it this far into the recovery process, why do you have to drop me? Like, do you not trust me? Well, you know, I guess not cuz you have to drop me. And … I don't really like that, because I don't identify with being an addict, but it's one of the stipulations to stay here, so … I don't … like how it looks. I don't like how they present it. I don't like how it makes me feel.

The home's regulatory practices exposed Jean to moral judgment of her character.

Jean also recalled an earlier instance when she “dropped dirty” for cocaine even though she had never used the substance. Jean was so upset when the staff member informed her that her drop was dirty that she became physically ill, vomiting for nearly twenty minutes. Jean's contestation that she never had used cocaine could not challenge the definitive results from the urine test. The staff member revoked Jean's weekend pass and would not allow her to sleep in her bedroom that night. Jean instead had to sleep on a couch downstairs, because, as the staff member told her, she was “toxic.” Jean explained the word choice: “When somebody's toxic, it's like you can like see 'em or some of their behaviors or what they're gonna be talkin' about, it'll like affect you in a negative way that'll make you want to go get high.” In other words, Jean's dirty drop (whether or not it was a false positive) marked her as an “addict” who had relapsed and thus was contagious to the other “recovering addicts” in the house. The staff member effectively quarantined Jean so that her mistake would not infect the other residents. This moral judgment took a toll on Jean and was enhanced by the many hidden sentences, discussed in the next section, that women encountered during and after incarceration.

Religion in the Post-Incarceration Moral Order

Along with recovery, religion was the foundational component of the post-incarceration moral order. The twelve-step framework establishes recovery as a moral and spiritual project (Sered and Norton-Hawk Reference Sered and Norton‐Hawk2011, Reference Sered and Norton‐Hawk2014; Tiger Reference Tiger2013; Dodes and Dodes Reference Dodes and Dodes2014). Echoing this framework, women consistently linked their work to maintain sobriety with their work to develop a relationship with God. Recovery homes stressed this message, requiring women to participate in bible study classes, church services, spiritual retreats, and various events in which prayer and religious songs were central. Religiosity was a cornerstone of establishing a life that was free from drug use and involvement with the criminal legal system. Staff members communicated this message in formal and informal ways.

The director of Starting Again required women to accompany her each Sunday to church. While some women expressed outright disapproval of this rule and said they preferred to attend a church of their choosing, others were more accepting of the rule. Red commented, “I think it's cool how [the director] loves to, I almost want to use the word manipulate, in a funny and a loving way, us to go to church … . I think it's cute how …we [are] just like her little ducklings … it's adorable to me.” While she implied some ambivalence about its mandatory nature, overall Red described attendance at this church as a helpful experience. She took a photograph at one of the church services and explained that the photograph showed how she and other residents were “recovering … changing from bad to good. God giving us a chance in life instead of keepin' us in prison … or keeping us sick, addicted to the wrong thing.” For Red, God was an integral part of her experience at the recovery home and of her overall transition from prison to society. Strengthening her faith also was a fundamental part of her personal moral transformation from “bad to good.” Her weekly church attendance, which she described as a new practice in her life since moving into Starting Again, served as a constant reminder of God's presence and the work Red still must do to reform her identity.

Like Red, many participants indicated that morality was central to their projects of personal transformation. In addition to the intense monitoring of women's recovery and punitive responses to relapse, the religious tone of reentry programs and the twelve-step logic linked women's understandings of their moral worth as connected to their sobriety and, by extension, to their “noncriminality.” Upon leaving prison or residential treatment facilities, women encountered a host of service providers and formerly incarcerated women who reinforced lessons about faith, sobriety, and morality. These providers and peers introduced women to and regulated the distinct post-incarceration moral order. Similar to the twelve-step logic women encountered in prison, the post-incarceration moral order required them to self-define as “recovering addicts,” always at risk of using again, who never would become former addicts (Leverentz Reference Leverentz2014; Sered and Norton-Hawk Reference Sered and Norton‐Hawk2014). Women understood the intertwining of the state's and the recovery home staff's identification of their sobriety as the foundation of their personal transformations and thus the most important goal of their post-prison life. Many women connected their loss of control over alcohol and drugs with their ongoing involvement with the criminal legal system, in short linking their “addict” identity with their “criminality.”

As this case illustrates, the state sought to transform those it deemed needing reconstruction of the self, but in less expressively punitive ways than those documented in studies of court-mandated drug treatment facilities (McKim Reference McKim2008; Kaye Reference Kaye2010, Reference Kaye2012; Gowan and Whetstone Reference Gowan and Whetstone2012; McCorkel Reference McCorkel2013) and long beyond the length of women's formal correctional sentences. Additionally, the moral foundation of the twelve-step logic and recovery homes' faith-based approaches drew connections between morality and sobriety. To resume drug use was to return not only to “criminal” but also immoral behavior. This linking of morality, sobriety, and personal transformation reflected the extralegal involvement of the penal state, which intervened in women's lives through program staff. Women were very aware of this degree of control over their recovery, achieved through urine tests and monitoring twelve-step meeting attendance, and the moral judgments and withdrawal of resources that followed failed performances of their rehabilitated identities.

For most of the women Rumpf interviewed, living at a recovery home no longer was required by the penal state. Yet, they reached these homes because of their criminalization. Indeed, their contact with the penal state was part of the criteria that qualified them for entrance. Thus, even when the penal state was ostensibly “hands off” in its approach to the women's lives, it intervened through nonstate actors who helped women to adjust to life after formal justice involvement via a distinct post-incarceration moral order. In this order, service providers and peers guided women through a lifelong project of personal transformation rooted in faith, sobriety, and morality (see McCorkel Reference McCorkel2013; Leverentz Reference Leverentz2014; Miller Reference Miller2014; Sered and Norton-Hawk Reference Sered and Norton‐Hawk2014). The judgment women faced for failing to uphold these standards was exacerbated by hidden sentences experienced throughout and after incarceration.

Covert Penal Control

We use the concept of hidden sentences to illustrate covert penal control: a regime of covert state sanctions that are legally instituted but nonetheless quite distinct from the expressive practices of imprisonment, precisely because they are hidden. The punishment framework largely views the state through the lens of surface-level policies that are salient to public and academic discourse because political actors expressly draw upon them. More submerged policies like hidden sentences (and to a lesser extent, noncarceral punishments such as probation or fines) are virtually absent from this discursive frame. This submergence creates a unique modality of state action that is experienced as covert penal control. This section presents two instances of covert control, both within and outside of carceral institutions.

Imprisonment in the United States: An Experience Defined by Hidden Sentences

Hidden sentences affect the lives of criminalized people at each stage of their involvement with the penal system: before, during, and after their visible sentences. Daily life inside US prisons, for instance, is recognized as exceptionally harsh, characterized by gang and guard violence, an absence of privacy, and numerous physical and mental abuses ranging from sexual assault to imposed isolation (Whitman Reference Whitman2003; Bruton Reference Bruton2004). In many cases, however, these sorts of experiences are actually structured by hidden sentence laws.

Gregory Hancock, Kevin Brian Necaise, Thomas Hebert, and Will Brown (real names) unexpectedly discovered a collection of such hidden sentences while incarcerated in Harrison County, Mississippi. The four men claimed they were sexually assaulted by a prison guard, Ernest Desautel (real name), on July 27 and July 28, 2002. After allegedly forcing the inmates to share illegal drugs with him, Desautel engaged in manual and oral sex with them—and then threatened physical retaliation and disciplinary lockdown if they reported the incident. The inmates sued Desautel and the Harrison County Adult Detention Center for damages from physical threats as well as emotional and mental suffering from the sexual assaults (Hancock v. Payne 2006).

The plaintiffs, however, did not anticipate the hidden sentences created by the Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1996 (PLRA), which seriously curtails prisoners' judicial access in every state. Under the PLRA, no incarcerated person (even those arrested but not yet convicted) can claim an indigence exemption from filing fees, be exempted from paying the prison's defense costs, proceed in civil court without exhausting all administrative remedies, including appeals and deadlines, receive any damages without proving a physical injury, or after having three suits dismissed, pursue any other claims (without imminent danger of serious physical injury). Moreover, the PLRA greatly limits plaintiffs' recoverable attorneys' fees while also restricting injunctive relief options.

The PLRA's stated purpose was to respond to a supposed nationwide overload of meritless, harassing lawsuits brought by incarcerated people by making lawsuits very expensive for them and curtailing the potential rewards (Schlanger Reference Schlanger2003). In some respects, the PLRA met its goals; prisoners' rights litigation initially declined by over 40 percent. However, these hidden sentences do not necessarily reduce “frivolous” claims as much as they make any case difficult to win (Schlanger Reference Schlanger2003).

Like most prisoners who file civil actions, Brown, Hancock, Hebert, and Necaise ran afoul of the PLRA's stringent requirements without prior warning. No law requires prisoners to receive notice about such laws at sentencing, admission to prison, or any other point in the penal process (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2016b). Prisoners' lawsuits such as Hancock v. Payne are therefore routinely dismissed for multiple PLRA violations.

In this case, the court found that only Hancock had pursued administrative remedies before filing suit. Hancock had asked officials to file charges and was denied. The other three plaintiffs apparently pursued no remedies within either Mississippi's penal system or the county detention center itself, so their claims were dismissed out of hand—consistent with many courts' treatment of the PLRA requirements (Robertson Reference Robertson2000). The court also dismissed Hancock's (and Hebert's and Brown's) suit for failure to provide notice of address changes. In 2005, Hancock was transferred between at least five prisons and sometimes failed to inform the court immediately of his new address, and at least one notification was allegedly lost by officials responsible for delivering it. With Hancock's case dismissed, no plaintiffs were left in the suit.

Then, the court dismissed the case again by finding that sexual assault alone does not satisfy the PLRA's requirements of a physical injury. According to an interpretation by the Fifth Circuit, all civil claims for emotional and mental injury must first demonstrate more than a de minimus physical injury (Siglar v. Hightower 1997). Subsequent rulings defined an injury that is more than de minimus as one that “would … require a free-world person to visit an emergency room” (Luong v. Hatt 1997), and have thus disqualified a shocking array of claims as invalid under the PLRA, from facial burns to severe asthma attacks (Human Rights Watch 2009). Based on such logic, the Mississippi district court declared that “the plaintiffs do not make any claim of physical injury beyond the bare allegation of sexual assault,” which does not qualify (Hancock v. Payne 2006, 3).

These four plaintiffs spent four years in court only to have their case dismissed for failing to fulfill requirements of a law about which they were never informed.Footnote 8 They wasted at least $150 on the filing fee, because the PLRA eliminated the traditional in forma pauperis route for indigent prisoners—in itself another hidden sentence. Because prisoners typically earn less than $10 per month, a fee of this magnitude can be detrimental. Finally, by failing to meet the requirements this time, each plaintiff became one “strike” closer to being barred by the PLRA from virtually all future lawsuits.

None of these experiences fall within the rubric of expressive punishment. In addition to the PLRA, prisoners face hidden sentences that abridge speech, press, and religious exercise; limit parental and marital rights; restrict employment; and ban them from educational and governmental programs (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2016a). Yet courts routinely hold that hidden sentences are not “punishment” and are therefore exempt from various constitutional protections—including those that would have required attorneys and judges to inform Brown, Hancock, Hebert, and Necaise that such laws exist (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2016b). Absent such notice, the plaintiffs were all but doomed to fail.

Hidden Sentences in Work, Family, and Community Life

The Supreme Court case Smith v. Doe (2003) provides a second useful example of covert penal control. In the mid-1990s, most states passed a Megan's Law, which requires sex offenders released from custody to register with local law enforcement and requires public agencies to notify communities of their status as sex offenders (Leon Reference Leon2015). In Smith v. Doe, two convicted sex offenders and one of their wives contested Alaska's version, the Alaska Sex Offender Registration Act of 1994 (ASORA).

Two of the unnamed plaintiffs had been charged with sexual abuse of a minor and had pled nolo contendere. By 1990, they had finished their prison sentences, completed treatment programs, and been released early on parole because of good behavior and established rehabilitation, including psychological evaluations that showed low reoffending risks. One plaintiff had remarried, started a business, been awarded custody of his daughter, and had reunited with his other children—including the victim. Both plaintiffs had been unconditionally released and had their civil rights restored by 1992. Two years later—about a decade after both men were initially convicted—Alaska passed ASORA, which retroactively subjected them to mandatory registration requirements and constant public stigma.

The plaintiffs therefore claimed ASORA was an ex post facto law. Article I of the US Constitution forbids any law to, after an action takes place, make the action criminal or impose new punishment for it. The question in this case, then, was whether mandatory registration and public notification of sex offenders is in fact punishment—making ASORA subject to the ex post facto prohibition and other constitutional protections.

As it has many times in the past, the Supreme Court found that hidden sentences like those in ASORA are not punishment. Under the Court's contemporary doctrine, a statute that imposes punishment must expressly or implicitly intend to punish, or be “so punitive in purpose or effect as to negate the State's intention to deem it civil” (Smith v. Doe 2003, 92). Note that this definition is a tautology, and that protecting public safety is a classic purpose of the penal system (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2016a). Nevertheless, the Supreme Court first found that ASORA explicitly pursues the “non-punitive, regulatory” aim of protecting citizens' health and safety. The opinion juxtaposed this goal with the overtly retributive motives behind imprisonment and other expressive punishments; the former is “merely” intended to combat dangerousness and not convey communal outrage and condemnation.

Next, the Court found ASORA's requirements were not so excessive in pursuing public safety that it becomes punishment anyway—even though ASORA uses an overbroad proxy for dangerousness that allows no room for evidence of rehabilitation or low reoffending risks. The opinion remarked on ASORA's similarity to historical shaming punishments, but ultimately ruled that active public notification of criminal histories is less similar to public shaming than to passive public availability of criminal records. Finally, the Court differentiated ASORA's penalties from both imprisonment and community supervision, because ASORA only required registration and did not mandate employment, living situations, and other social activities. Thus, Smith v. Doe held that it was permissible for Alaska to impose new penalties on sex offenders who had not had such penalties imposed, nor been warned of them, at their time of conviction.

At its core, then, this decision directly addressed the line between overt and covert penal control; it considered whether hidden sentences are expressive punishment for the purposes of the constitutional line between civil and criminal laws. Even when a well publicized hidden sentence such as ASORA appears before the Supreme Court, it is still considered something other than expressive punishment.Footnote 9 The same logic has been applied to countless hidden sentence laws, from civil forfeitures and fines to loss of welfare and pension benefits to bans on public and private employment (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2016a). Courts still rule that these covert state actions are “mere civil regulations.”

The Submerged Penal State and the Punishment Frame

Covert state intervention depends on obscurity. Some policymakers and academics, specifically those who consider prisoners' rights or the so-called collateral consequences of criminal convictions, are cognizant of a few hidden sentences (Demleitner Reference Demleitner1999; Manza and Uggen Reference Manza and Uggen2008). The mass incarceration discourse itself occasionally recognizes them (Garland Reference Garland2001a; Whitman Reference Whitman2003). Hidden sentences, however, are thought of as restrictions that are simply tacked onto imprisonment—additional, possibly unintentional damage following from punitive policies—while the focus remains on prisons. Likewise, courts and policymakers routinely overlook hidden sentences as the unquestioned or simply “necessary” result of criminal actions and policies. As a result, experts and laypersons alike routinely fail to recognize the intricacies of both prison and community life as characterized explicitly by penal state intervention.

Through hidden sentences, the state impedes criminalized people's lives legally but without drawing upon overtly punitive logics, and without the public notice and express condemnation of imprisonment. Such covert state action expands penal control while keeping the vast majority of the penal state submerged from view. In fact, there are more than 35,000 hidden sentence laws across the nation, and they directly impact approximately one in three American adults (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2016a)—yet academics, jurists, the public, and criminalized people themselves know very little about them.

Negligent Penal Control

The penal state also controls criminalized people through its absence. This absence is visible during work release, an arrangement in which people approaching their prison release date typically stay overnight at a minimum security correctional center and conduct paid work for a private company in the community during the day (Berk Reference Berk2008; Spicuzza Reference Spicuzza2014). Work release can be appealing because it can significantly increase incarcerated people's pay, provide opportunities for post-release employment, and lessen the chance of return to prison (Berk Reference Berk2008). However, the arrangements governing work release effectively offload responsibilities and risks onto private parties, thereby controlling the circumstances of incarcerated workers who suffer on-the-job injuries. The institutional responses to work release injuries discussed below show that these policies allow the absence of one agency, the Wisconsin Department of Corrections (WDOC), when incarcerated people need its protection the most.

Understanding negligent penal control in this context requires seeing the selective involvement of the penal state in work release and on-the-job injuries.Footnote 10 The WDOC is involved in making work release possible by performing key tasks, including managing relations with the employer, selecting eligible workers, employing a work release coordinator to handle applications and placements, withdrawing the privilege of work release when conduct is not appropriate and for other reasons, and maintaining legal custody of the person on work release (WDOC 2007; WDOC 2014). Yet the agency is also absent in key ways. The person on work release most directly works with private companies, and may travel to work sites via rides from contracted nongovernmental staff. Even preparation for the work release job is a service that WDOC contracts out to NGOs. For example, the WDOC requested bids from community-based NGOs to provide employment support services at several men's correctional centers in order to “prepare inmates for a safe and successful reintegration into the community” through work release, specifically through teaching such lessons as “developing a budget and understanding money management” and “problem solving work place issues” (Request For Bid #KK-4570 2016).Footnote 11 The very design of work release enables the relative absence of the WDOC staff as the labor is performed.

Gone When You Need Them

One illustration of how this absence constitutes negligent penal control is the way the burden falls on private companies to compensate the parties who are injured at work release jobs.Footnote 12 An incarcerated person who is injured on work release in Wisconsin may be treated in the same way as any other employee of the company. As in some other states (Dougherty Reference Dougherty2008), Wisconsin's policies allow prisoners who are injured on work release at private work sites to be eligible for worker's compensation that would be paid out by private companies (Wisconsin Statutes 2013–2014). When incarcerated people suffer from permanent incapacitation or materially reduced earning power due to a workplace injury, their compensation claims to the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development (WDWD) should be treated like the claims of nonincarcerated employees (Wisconsin Statutes 2013-2014).Footnote 13 All together, this arrangement largely removes the WDOC from the processing of these claims. The implications become clear in the example of Hank Jones's injury.

During Kaufman's fieldwork, she met Jones at a community-based group discussion session; he described having been previously injured on work release. Jones described being in pain, unable to work, and unable to cover his own medical bills. After disagreements about who should pay, he finally got supported by Badgercare (the state-supported health care program for people earning up to 185% of the federal poverty limit). He viewed this situation as unsatisfactory because it did not hold the relevant agency accountable, but at least it relieved some of the cost burden.

The policies governing work release and the agency's decisions in placing Jones at this site shaped his experience on the job and subsequently. Aside from the particulars of Jones's situation, the denial of a worker's compensation claim by the WDWD could occur for multiple reasons reflecting the actions of employers, employees, or insurance carriers (WDWD n.d.). Although appeals are possible, they may require the claimant to have significant time and legal knowledge about administrative procedures that may not be reasonable expectations for criminalized people with serious limitations in their time, expertise, and money. So, people who were previously injured on work release and remain physically unable to work face the daunting possibility of being denied claims and not being in a position to appeal them. Meanwhile, the WDOC is structurally left out of the claims process, which is handled by the WDWD and potentially the courts.

Work Release and Occupational Hazards

After meeting Jones, Kaufman learned of the case of David Champeny (real name), which concerns the penal state's supervision of worker safety at work release job sites. As in any physically demanding or potentially injurious job, work release positions that may expose employees to hazards can degrade workers' health and limit their employability after release. Unlike free workers, however, incarcerated people are in the legal custody of an agency tasked with protecting their safety (WDOC 2007). Indeed, the WDOC states in its list of core values, “We value safety—for our employees, the people in our charge and the citizens we serve” (WDOC n.d.). Meanwhile, the private employer retains responsibility for maintaining a safe work site under the standards set by federal regulators (OSHA 2014). Additionally, unlike many other forms of prison labor, corrections staff do not share the workplace with the offsite companies, and thus may be less likely to detect safety problems. These built-in forms of penal state absence indicate ways in which the design of work release jobs may allow the operation of private “spaces of neglect” (Simon Reference Simon2014).

Between 2004 and 2013, 326 incarcerated people held WDOC work release jobs at Fiberdome (real name), a fiberglass manufacturing company (Hall Reference Hall2013c). In both 2011 and 2013, the U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Agency (OSHA) cited the company for worker safety violations (OSHA 2013a, 2013b, 2014); the investigations in 2013 were in response to reports from workers about their own illness (Hall Reference Hall2013b, Reference Hall2013c; OSHA 2014). Among the violations OSHA deemed “serious” were that an employee had been exposed to styrene at excessive levels, and that Fiberdome had not developed or implemented a written respiratory protection plan or provided adequate training for respirators (OSHA 2013a, 2013b). The company paid $18,162 in fines for nine violations in a settlement with OSHA (Hall Reference Hall2014).

David Champeny was reportedly one of two people on work release who became ill while working at Fiberdome (Hall Reference Hall2013a). Journalist Dee Hall reported that Champeny was hospitalized for two days with breathing difficulty after chemical exposures at Fiberdome (Hall Reference Hall2013b). According to his doctor, he suffered from swollen bronchial tubes that occurred from the toxic exposure and was expected to sustain lung damage. The other injured man on work release at the same company reportedly had similar symptoms (Hall Reference Hall2013a, Hall Reference Hall2013c, Hall Reference Hall2014).

After the OSHA investigations, the WDOC played a role in mitigating potential harm to others on work release there. A WDOC spokesman reported to Hall that the WDOC would remove workers from this site (Hall Reference Hall2013c). He also said that the WDOC routinely checks work sites and had checked this site sixteen times prior to and after the injury of Champeny, and that it had looked into previous reports of injuries (Hall Reference Hall2013a).

However, accessing information about the risks at this site was prohibitively difficult. Champeny and his doctor could not obtain information about the chemical that made him sick; his doctor's questions of the WDOC and the company reportedly remained unanswered, as did Champeny's queries to the work release coordinator (Hall Reference Hall2013a).Footnote 14 Furthermore, when Champeny wrote his former employer a letter that demanded information about the chemical, WDOC staff regarded it as overly aggressive and used it as a key reason to deny his parole and send him to solitary confinement (Hall Reference Hall2013a). This punishment was reversed several months later (Hall Reference Hall2013c).Footnote 15

The partial absence of the WDOC from this case is first evident in the off-site location. It is plausible that an inspector making planned trips to the work site would be less likely to observe problems on this scale than would someone who was on site every day. Second, the agency's absence is evident in the way that policies making work release possible displaced responsibility for dealing with the implications of workplace hazards to this private employer. Together, these forms of absence are controlling because they shape incarcerated people's options for action and thereby their experiences. Efforts to mobilize and self-advocate in the face of injury are met with significant obstacles, not the least of which are limited ability to file and appeal claims, and limited ability to access information without sanction.

The penal state is often described as controlling through commission—for example, police use of force, surveillance by probation and parole agents—rather than omission. Champeny was punished for his letter, and this is only one way in which penal state actors and policies shaped the opportunities and risks he faced. Jones's and Champeny's cases are instances of penal state negligence that are distinct from the prominent model of control through positive action. The particular controlling aspects of the penal state occur not only through the direct implementation of punishment, but also through policies that facilitate inmates' labor at risky work sites.

Penology, Penal Reform, and Modalities of Control

Scholars across fields and disciplines are currently reconceptualizing the state amidst recent changes in governance, the unprecedented growth in the criminalized population, and the rescission of fundamental rights to the poor. In similar fashion, this article has asked: Beyond punishing criminalized people, how does the state control? In answer, we offer the concept of modalities of penal control; the three modalities we discussed—interventionist, covert, and negligent—aid in creating a framework for the analysis of current penological projects that moves beyond a simple, expressive punishment framework. Each of these modalities of control contrasts with some aspect of expressive punishment. Punishment is undoubtedly important, as it sets in motion the mechanisms through which the penal state controls. Yet as compelling as it may be as a global explanation of the work of the penal state, it is only a partial explanation for the empirical cases examined above. Thus, we have moved our focus beyond punishment in explaining instances of the penal state's controlling interventions, and have moved beyond entrenched ideas about the scope of the state's involvement in criminalized people's lives. Moving beyond punishment also involves identifying this work as not merely encompassing a “shadow carceral state” (Beckett and Murakawa Reference Beckett and Murakawa2012), but rather involving a broad array of both state and nongovernmental actors.

Combined, the cases show how a focus on expressive punishment, even with an eye toward broader implications, can obscure many aspects of the way the experiences of criminalized people are structured through a vast system of laws and relationships with nongovernmental actors. We have illuminated interventions and practices that are punitive, yet often operate in unexpected ways and through diverse mechanisms. What unites the situations of Jean, Red, the Mississippi plaintiffs, and the people injured on work release is the penal state's dismissive view of criminalized people as failed individuals deserving punishment. This stance is complemented by the penal state's reliance on third parties, who then risk worsening the situations of criminalized people or further excluding and shaming these individuals.

Together, the cases we have examined show the overwhelming constraints the penal state imposes post-incarceration, even in moments when people experience this intervention as enabling. The women interviewed in Illinois used and appreciated the available discourses to guide their personal transformations, even when these discourses constrained their behavior and carried judgments about their moral worth. The state connected people to employment in the Wisconsin data, but in a way that left them vulnerable to workplace injury and did not place the WDOC in a position to remedy the harm done. In the analysis of hidden sentences using PLRA and ASORA research, state involvement seems solely constraining. While the interventionist modality of penal control directs criminalized people to lifelong personal transformation projects, implying they are incapable of maintaining “clean” identities and staying out of trouble with the law, the covert and negligent modalities of penal control justify the routine disregard of people's well-being and rights, based solely on their involvement with the criminal legal system.

Today's penal state is not merely acting in formal, punitive ways, as portrayed in the Austinian image of the issuer of laws and commands, the prison guard, or the actor waiting to make good on the threat of incurring evil on the uncompliant (Austin [1832] Reference Austin1968), nor is the state itself monopolizing the power to exert penal control. Similarly, the three other forms of control we identify are not merely extensions of expressive punishment as prior scholarship often claims or implies, but rather modalities of penal control in their own right, operating alongside and sometimes independent of punitive control. Today's penal state operates in nuanced ways and through intermediary sites to control criminalized people in a host of overt and obscured ways. The task moving ahead is not merely to displace punishment and control outside of the prison walls; if the nuance in how the penal state operates is overlooked, any proposed solutions will fail.

Most importantly, this article illuminates an important reality in a critical moment of potential reform. Strong movements from both the political right and the political left are now converging to call for reductions in prison populations, the end of the War on Drugs, and even a potential return to rehabilitative aims. In light of the cases examined in this article, however, these reform efforts are limited if, in the same way as scholarship that informs them, their central focus is on expressive punishment.

Decarceration alone will not undo these modalities of control; closing prisons will not itself produce freedom from the penal state. As Andrew Dilts (Reference Dilts2014, 227) writes, to frankly confront the status quo we must “imagine not simply a better world but a different one … the harder and more important work is to destroy the structures, the ways of thinking, and the practices that gave rise to it.” Decarceration is not enough; even if expressive punishment decreases, this research shows how the penal state can and likely will remain involved in criminalized people's lives in consequential ways that range from legal to extralegal, surface to submerged, and present to absent. This analysis suggests that even as the type of penal state involvement varies, underlying forces of late modernity that value personal responsibility, uphold employment as salvation, and bracket questions of structural inequality and social justice may remain deeply entrenched in the many manifestations of the penal state.

Instead, we need a more comprehensive reform endeavor that overhauls not just forms of expressive punishment but penal state involvement as a whole. Efforts to reform prisons and sentencing may bring about important improvements only to leave the criminal legal system and the logics on which it rests intact. Ultimately, we need what Ruth Wilson Gilmore (Reference Gilmore2007, 242) has called “nonreformist reform … changes that, at the end of the day, unravel rather than widen the net of social control through criminalization.” Moving the focus beyond punishment may generate not only a deeper understanding of how the penal state is involved throughout criminalized people's lives, but also how to comprehensively reform a wide range of modalities of penal control. This broader focus will guard against reform efforts that serve to reproduce the status quo, those that will unintentionally change expressive punishment into new forms of penal control that are even more difficult to identify and ultimately harder to dismantle.