Scholars, journalists, and government authorities report that Mexican drug-trafficking organizations—commonly known as drug cartels, such as the Zetas, the Gulf Cartel, and the Sinaloa Cartel—have expanded their repertoire of illegal revenue-generating activities to include, among other endeavors, human trafficking for the purposes of labor and sexual exploitation and bodily organ harvesting (Correa-Cabrera Reference Correa-Cabrera2017; Murray Reference Murray2020).Footnote 1 The massacre of 72 migrants in San Fernando, Tamaulipas in 2010 by the Zetas for lack of cooperation, and recently documented cases of sex trafficking and labor trafficking (including compelled labor for criminal activities) along Mexico’s migration routes—which allegedly involve drug cartels—illustrate these phenomena.

What is the relationship between trafficking of migrants and other forms of organized crime, such as drug trafficking, human smuggling, and other local criminal activities?Footnote 2 To what extent are criminal actors or organizations involved in trafficking of migrants, and what is the nature of their involvement? Mexico is a source, transit, and destination country for trafficking in persons. Human-trafficking patterns have been documented by some scholars and organizations (Rietig Reference Rietig2015; Torres Falcón Reference Torres Falcón2016; HIP 2017), but not many studies have provided comprehensive information about the role of drug cartels and other local and transnational criminal actors on these activities.

Overall, some attention has been given to the connection between human trafficking and other forms of transnational organized crime (such as drug trafficking) in different parts of the world (Shelley Reference Shelley2012; Sheinis Reference Sheinis2012; Sampó Reference Sampó2017), but mechanisms of transmission have not been thoroughly analyzed and described. While an increasing number of studies mention the connections between trafficking in persons and other forms of organized crime, most of the existing literature examines such relations without providing sufficient details. Further empirical data are needed to better comprehend these phenomena. At the same time, policymakers and scholars often make broad estimates of the scale of involvement of cartels or gangs in human trafficking without providing much supporting evidence. This is understandable, considering the significant risks that empirical work of this kind entails. Not many researchers are willing to risk their physical integrity conducting these studies, which involve extremely violent actors. There are certainly important limits to the comprehensive understanding of these phenomena.

There have been a small number of analyses of the involvement of Mexican-origin drug cartels or Central American gangs in the phenomenon of trafficking of migrants (Casillas Reference Casillas2012; Correa-Cabrera and Machuca Reference Correa-Cabrera and Machuca2018; Izcara Palacios 2019). Therefore it is worth conducting further studies that analyze the situation in Mexico and Central America (particularly the so-called Northern Triangle). One should consider the current economic and safety conditions that have been driving mass migrations from these regions to the United States and have placed irregular migrants at great risk of exploitation, trafficking, and other types of abuses. Moreover, these difficult conditions have significantly worsened during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article examines the interplay between transnational criminal actors (e.g., human smugglers), local crime groups, and drug cartels in the phenomenon of human trafficking along Mexico’s eastern migration routes from Central America (mainly from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador) to the Mexican northeastern border. In this region, certain drug-trafficking organizations (commonly known as ‘drug cartels’), as well as some local criminal groups controlling key territories, also smuggle and traffic irregular migrants in order to diversify their revenue streams. The involvement of these criminal actors in the trafficking of irregular migrants in transit from Central America to the United States is a key hemispheric problem that needs to be further analyzed.

Many researchers and public officials interested in this phenomenon have relied on anecdotal evidence, informants of dubious credibility, and informal sources that have not been appropriately verified or systematized. This type of work is dangerous, but more extensive field research is needed to better understand such a phenomenon that involves transnational actors, generates billions of dollars in profits, and represents a very complex human problem.

Methodology

Due to the inherently hidden nature of organized crime and the great limitations when trying to quantify and analyze illicit activities, qualitative and ethnographic methods provide greater insights into these activities than other methodological approaches. Data for the present project were collected through semistructured interviews conducted with migrants in key shelters, prisoners charged with human-trafficking crimes, academics, journalists, and other relevant actors in Central America and along Mexico’s eastern migration routes. The following sections include research notes based on 336 semistructured interviews, which can be divided into three groups:Footnote 3

-

1. Interviews with migrants, shelter workers, and human rights NGOs and practitioners in Tapachula, Chiapas; Tenosique, Tabasco; the migrant routes along the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Veracruz, Puebla, Tlaxcala, the State of Mexico, Querétaro, Guanajuato, and San Luis Potosí; Saltillo, Torreón, Piedras Negras, and Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila; Reynosa, Matamoros, and Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas; Monterrey, Nuevo León; and Cancún, Quintana Roo.Footnote 4

-

2. Interviews with law enforcement agents, experts or academics, human rights NGOs and practitioners, repatriated migrants, lawyers, and prosecutors in Mexico City, Cancún, San Salvador, Guatemala City, Tegucigalpa, San Pedro Sula, and La Ceiba.

-

3. Interviews with prisoners charged with human-trafficking crimes in Tapachula.

The usual duration of the interviews was between 30 minutes and one hour. They were conducted following separate interview guidelines.Footnote 5 Interviews were complemented by ethnographic work conducted at key migrant shelters in Mexico and the three airports receiving deported migrants in San Salvador, San Pedro Sula and Guatemala City.Footnote 6 A total of 168 migrants were interviewed for this work, and none of them were victims of human trafficking.Footnote 7 Some migrants were interviewed in groups, and the duration of those interviews fluctuated substantially. The selection of interviewees at migrant shelters or other migrant facilities was random, and none of these conversations was recorded. Written notes were taken considering the respective interview guidelines.

The rest of the interviewees were initially selected on the basis of preliminary research on the subject matter, prior identification of available sources, and contact with experts on related topics and organizations located in the field sites. Additional interviewees were selected by using a snowball sampling technique. The following topics were discussed during the interviews: reasons for emigrating; security situation in the country of origin; type of transaction with the smuggler; abuses experienced or identified along Mexico’s migration routes; encounters with criminal organizations; and incidents of labor exploitation or trafficking, both in their countries of origin and along Mexico’s migration routes.

The analysis of the data provided by the interviewees, together with the background information available in secondary sources, was utilized to re-create the current dynamics of trafficking of migrants by transnational criminal actors along Mexico’s eastern migration routes. These patterns were located on maps designed with help of ArcGIS Online software.Footnote 8 Responses by the interviewees were organized or systematized according to the topics delineated in the five interview guidelines designed to answer the main questions of this project. For the present work, quotes of (or observations from) only 15 interviewees were used. They represent the opinions of many others and depict key aspects that needed to be highlighted.

In sum, the present study analyzes the relation between trafficking of migrants and other forms of organized crime and tries to determine the extent to which the involvement of cartels, smugglers (coyotes), and other criminal groups in human trafficking is opportunistic or is more premeditated and systemic. These research notes can help to create a more current, nuanced, and theoretical understanding of human trafficking that takes into account the range of conditions that lead migrants into situations where gangs or drug cartels coerce them into performing activities without receiving compensation.

This article is divided into two main sections. The first section describes and maps human-trafficking trends along Mexico’s eastern migration routes. The second part explains the specific roles performed by Mexican cartels and other criminal groups in the trafficking of migrants. This report concludes by reflecting on these trends in times of further migration and border enforcement and the COVID-19 pandemic, and provides some recommendations to alleviate this human problem. The present analysis finishes at the end of Donald J. Trump’s administration (2017).Footnote 9

Regional Patterns of Migrant Trafficking

The practice of human trafficking and the modus operandi of traffickers in Mexico are not homogenous. The purpose for which people are trafficked and the profile of the victims vary depending on the region of the country. From what was observed through the fieldwork and interviews conducted for this study, human traffickers target migrants who are already in a vulnerable situation and who are passing (or being smuggled) through their territories, instead of transporting their victims themselves. The transportation is carried out by human smugglers (also referred to as coyotes).Footnote 10 Usually, these two activities are performed by different networks of actors. Although one cannot rule out the existence of more sophisticated trafficking networks moving victims across state and international borders, the present work mainly verifies the trafficking of migrants in a local context and as a crime of opportunity.

By exploring Mexico’s eastern migration routes, one can observe that trafficking of migrants in southern and northern Mexico presents two distinct patterns. Criminals traffic migrants in transit along the migration routes to sexually exploit them and to compel them to commit crimes, but the incidence of each type of crime varies depending on the region of the country. In the south of Mexico, trafficking in persons for the purpose of sexual exploitation is the most common practice, while in the north, trafficking for the purpose of compelled criminal activity prevails (see appendix maps 2 and 4).

Southern Mexico

The southern states of Quintana Roo and Chiapas, “once only transition points for migrants seeking to reach [the United States], have become, in recent years, desired destinations for migrants hoping to settle down in Mexico” (Correa-Cabrera and Clark Reference Correa-Cabrera2017, 68). Crime groups and corporate interests in this region target Central American migrants; some groups demand extortion fees and others exploit their cheap labor in the touristic and construction sectors, as well as in the sex trade. With regard to trafficking in persons, bar and brothel owners often (but not always) force young female migrants to work in the sex industry in what constitutes, by Mexican and international definitions, human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation.

Migrants from Central America cross into Mexico through a variety of entry points along the Mexican southern border, but mainly follow two key routes (see appendix map 1). It is worth noting that the dynamics of human mobility from Central America to the United States are in constant change. According to some accounts, the state of Chiapas is the preferred—and more convenient—point of entry into Mexico for Salvadorans, while a large number of Honduran citizens prefer to enter Mexico through the state of Tabasco (see appendix map 1). A number of migrants from Guatemala, particularly women and girls, decide to stay in the city of Tapachula instead of continuing their journey to the United States. In a context of stricter border controls in the United States and Mexico, the close proximity of this Mexican border city to their country of origin makes it easier for undocumented migrants to send money to their relatives and to visit their families more frequently.

Impoverished migrant women often find jobs as waitresses or sex workers in the city’s numerous bars and brothels. According to one staff member of the NGO Casa de la Mujer in Tecún Umán, Guatemala, some of these women become indebted to persons who provide clients or to the bar owners (interview 1). They are then forced to work for food, clothing, or a place to stay. It is worth noting that not all Central American “prostitutes” are victims of trafficking, and some willingly work in the sex industry. Nevertheless, the line between “willingly working as a prostitute” and “being forced” to do so is often hard to assess, considering the enormous vulnerability of undocumented migrant women from Central America. Moreover, it is not always clear if the sex worker is speaking honestly about choosing to be a prostitute or out of fear of what the bar or brothel owner might do to her in case she reports abuses, fraud, or coercion.

One of the places where trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation recurs in Mexico is the so-called botaneros. These establishments serve inexpensive appetizers (botanas) and alcoholic beverages. Owners of such bars located near Mexico’s southern border regularly offer employment to young migrant women. Although Mexico does not issue permits allowing prostitution to take place in botaneros, female employees in some of these establishments are required to take health exams and prove that they do not have any sexually transmitted disease (STD). “In order to increase profits and bring more clients, bar owners force or convince waitresses to drink with the clients.” In a practice known as fichar, a client who would normally pay 45 pesos for a beer (2.25 US dollars) “pays four times that amount to have a waitress sit with him, whom he can sexually caress. The waitress has little to no say in the matter, and most of the profit goes to the bar owner” (Correa-Cabrera and Clark Reference Correa-Cabrera2017, 66).

Law enforcement authorities routinely raid botaneros, but there are strong indications of collusion between bar owners and them. In a fieldtrip to Chiapas, one of the authors of this study interviewed a migrant woman who worked in a bar and was jailed for trafficking. She was eventually acquitted. The woman claimed to have worked in a number of bars or botaneros in Tapachula and described the close relationship that allegedly exists between law enforcement authorities and owners of this kind of establishment in the city. According to her, “officials responsible for issuing restaurant licenses would demand bribes from botanero owners, who regularly break the law.” The woman also stated that “whenever authorities raided bars, the owners were never present and the bar staff, often poor migrants, were arrested for trafficking instead.” She assumed that officials informed bar owners of incoming raids (interview 2).Footnote 11

Migrant sex workers find themselves often in an ambiguous position in cities that are important prostitution hubs, like Tapachula, where they tend to be revictimized because law enforcement does not usually differentiate between a consensual prostitute, a human-trafficking victim, and a trafficker. Mexico’s trafficking legislation and the economic incentives available to a number of actors, including human rights NGOs and practitioners, contribute to perpetuating the problem (Correa-Cabrera and Sanders Montandon Reference Correa-Cabrera and Sanders Montandon2018). The production of victims or revictimization of migrant sex workers is frequent in cities of southern Mexico like Tapachula because victims are a source of income—both to anti–human-trafficking NGOs and to certain government agencies.

The phenomenon of human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation is also frequent in the Yucatán Peninsula, and particularly in Cancún. This city attracts tourists from all over the world to its beautiful beaches. Cancún’s well-developed tourism industry also attracts a significant number of Central American irregular migrants who decide to stay in Mexico instead of traveling to the United States. These individuals are extremely poorand uneducated and lack family networks. Therefore they are particularly vulnerable to labor exploitation and trafficking in persons.

While sex trafficking in Tapachula usually takes place in cheap bars, cantinas, or botaneros, this phenomenon in Cancún takes place frequently in brothels and spas. Traffickers approach foreign tourists, often from the United States and Europe, and take them to establishments of this type, where forced prostitution of migrants and minors occurs. According to a women’s rights advocate working in Cancún, foreign female victims of sex trafficking in this city “can be divided into two groups based on their places of origin. Migrants from South America, the Caribbean, and Eastern Europe are usually sought by traffickers for their beauty. Migrants from Central America, typically of indigenous descent, are prized for their youth and virginity.” In fact, “minors constitute a significant portion of Central American migrants sexually exploited in Cancún.”Footnote 12 However, it is impossible to assess the actual dimension of the problem. One cannot calculate with accuracy the number of foreign-born underage victims of trafficking in this tourist city; there is no comprehensive data to correctly assess the dimension of this problem (Correa-Cabrera and Clark Reference Correa-Cabrera2017, 69).

Northeastern Mexico

While sexual exploitation is the prevailing purpose for trafficking in southern Mexico (perpetrated mainly by local groups consisting of families and bar and brothel owners), in northeastern Mexico migrants are trafficked by cartels for the purpose of compelled criminal activity. In the states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, and Coahuila, where intense clashes among competing cartels and law enforcement have claimed the lives of thousands of people since the late 2000s, criminals have forced migrants to join their ranks to compensate for casualties. Cartels also eventually force migrants to perform as lookouts, migrant smugglers, and sicarios, or hitmen (interview 6).

Two main factors influence the shift in trafficking trends from southern states to northern states. First, because the United States is the main consumer of cartels’ narcotics, drug-trafficking organizations fight over strategic cities along the border from where they can control the flow of drugs. Cartels are in constant need of manpower to overcome rival gangs and law enforcement. Second, many migrant advocates have claimed that the number of male Central American migrants arriving in the northern states is significantly higher than that of female migrants. The state of Mexico is roughly the midway point for migrants attempting to reach the northern states. According to migrant activists there, 80 percent of Central American women in Mexico stay in the southern states, some of them working in botaneros. Only 20 percent of them allegedly move north (interview 3). Human rights advocates also claim that only one in ten migrants arriving at the Lechería train station in the Mexico City metropolitan area, where migrants can still board the infamous La Bestia train, is female (interview 4).Footnote 13 The disproportionate number of migrant men in the north are more profitable to criminals as cannon fodder than for sexual exploitation.

From the late 2000s to the early 2010s, cartel violence reached its peak in the northeastern Mexican states. The homicide rate in the city of Torreón, Coahuila, provides a good example of the magnitude of violence northern Mexico experienced. In 2006, authorities registered 62 homicides in Torreón. Five years later, that number was 990 (Graham Reference Graham2012). Although no cases of trafficking of migrants were registered in Torreón, as the city is not a major migration hub, migrants were still caught in the midst of cartel violence and were still trafficked in Coahuila. A social worker volunteering in a migrant shelter in Saltillo reported that cartels, particularly the Zetas, kidnapped male and female migrants and exploited their labor. Forced activities ranged from domestic labor, such as cooking and cleaning hideouts, to washing vehicles used in killings, sexual servitude, and assassinating rival cartel members (interview 5). Nevertheless, other social workers in Saltillo stated that it is hard to assess when migrants join cartels because they are forced to and when they do so voluntarily. Similar to migrant women who choose to become sex workers in southern states, some migrants decide to join cartels in northern Mexico voluntarily for the money.

The main border cities of the state of Tamaulipas, such as Matamoros, Reynosa, and Nuevo Laredo, are hotspots for trafficking for the purpose of compelled criminal activities (see map 4). These cities are points of convergence between migrants arriving from the south at the end of their journey (and eager to cross into the United States) and migrants deported from the United States. In the early 2010s in the state of Tamaulipas, both the warring Gulf Cartel and the Zetas frequently kidnapped migrants and forced them to join their ranks. The experts interviewed for this work believe that the Zetas (or related criminal cells) were involved in the trafficking of migrants in the southern regions of Tamaulipas and Nuevo Laredo, while the Gulf Cartel controlled the forced recruitment of migrants in Matamoros and Reynosa (interview 6). This situation has changed nowadays to some extent. Forced labor for criminal activities seems to be less frequent, but cartels still recruit migrants, who work for them voluntarily most times.

The city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, is (according to some) “the main point of entry of undocumented Central American migrants into the United States” (interview 6). According to some testimonies, in Reynosa, cartel members not only force migrants to commit crimes but also allegedly force female migrants into prostitution (interview 7). That was the case of a Salvadoran migrant woman. According to Mirna Salazar de Calles, lead prosecutor for a special human-trafficking unit in El Salvador, the woman hired a smuggler who, instead of getting her to the United States, sold her to Los Zetas. The prosecutor described how the woman was forced to take drugs, then forced to work as a prostitute in Reynosa, and was even tattooed to denote that she was the “property” of the cartel (Zamudio Reference Zamudio2014).

The Washington Post reported the arrest of a cartel leader accused of “purchasing” Central American teenagers from a smuggler and forcing them into prostitution in bars and hotels in Reynosa (O’Connor Reference O’Connor2011). Although there are some anecdotal accounts of cartels’ participation in prostitution in Reynosa, it is difficult to determine if drug-trafficking organizations actually manage human-trafficking rings. It is important to note that in the fieldwork conducted for the present study, Reynosa was the only city where cartels seemed to have a direct participation in prostitution operations, instead of merely charging prostitutes and brothels an extortion fee (interview 7).

Transnational Criminal Actors and Trafficking of Migrants

With the exception of trafficking cases for the purpose of compelled criminal activities in Tamaulipas and some other northern Mexican cities in the state of Sonora, the role played by cartels in migrant smuggling and trafficking in persons in Mexico is opportunistic rather than structured or highly organized. Evidence from the present research shows that it is very infrequent that drug cartels manage human trafficking rings directly in addition to their involvement in drug distribution in brothels and bars. However, these crime groups seem to restrict their interactions with human smugglers and traffickers to charging migrants a fee to transit through their territories unharmed, as well as charging sex traffickers and sex workers a fee for the right to conduct their activities in cartel-controlled territory.

According to a sex worker interviewed for this work, in Cancún during the years 2014–16, the Zetas demanded that some sex workers work only in Zeta-approved spas and pay the cartel extortion fees (interview 8). In early 2016, Boris Calex Madariaga Hidalgo, a 22-year-old Honduran migrant and male sex worker, refused to pay the extortion fee. On April 8, two days after answering an online request for sex services and not returning home, local authorities found Madariaga’s lifeless body abandoned in a mangrove near Cancún. He had his hands tied behind his back, duct tape covering his mouth, and a gunshot wound to the head (interview 8).

In Chiapas, police believe that the Zetas ceased to operate in the state several years ago (interview 9). Criminal activity in the state—and particularly in the border region with Guatemala—is allegedly spearheaded by local gangs and some elements of Central American gangs, notably the Maras. However, the Maras, having suffered greatly from law enforcement operations and infighting feuds, are not nearly as active in Chiapas as they are in Central America. According to some sources, their operations are almost exclusively confined to areas adjacent to train tracks, where they extort migrants; some of them also operate in the city of Tapachula (interview 10). Nevertheless, some local activists and experts, including a migrant shelter director and a former coordinator at the National Commission of Human Rights (CNDH) office in Tapachula, claim that drug cartels are also involved in human trafficking in the state (interviews 11 and 12). It is worth noting that they did not provide evidence to substantiate their claims.

The majority of human traffickers targeting Central American migrants along Mexico’s eastern migration routes seem to be part of local trafficking rings, usually formed by families or bar and brothel owners. These traffickers, in turn, pay the cartels to operate in their territories. However, human trafficking in Mexico is not confined to targeting foreign migrants or to urban and rural areas along the migration routes. The state of Tlaxcala has long been a hub for sex trafficking, where family-led prostitution rings in the city of Tenancingo have operated since the 1950s. Family members, including sons, mothers, and grandmothers, lure young Mexican girls from impoverished states, such as Oaxaca, Tabasco, Puebla, Chiapas, Veracruz, and Guerrero, into forced prostitution (interview 13). In this case, undocumented migrants do not seem to be the main targets of these crime groups.

A victim interviewed by the Attorney General’s organized crime unit (SEIDO) in Tlaxcala claimed that there are links between crime families in Tlaxcala and cartels including the Gulf Cartel, some criminal cells of Los Zetas, the Knights Templar, and the Familia Michoacana.Footnote 14 The sex-trafficking rings would transport their victims by truck to safe houses in Tlaxcala, from where victims were moved either to Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, or Nuevo Laredo and finally on to the United States (Kutner Reference Kutner2015). These claims, however, have not been corroborated.

Conclusions

This research is situated in a pressing humanitarian context, in which thousands of people moving along Mexican and Central American migration routes face the threats of trafficking and violence. By the end of the Trump administration, tens of thousands of asylum seekers were stranded in Mexico, due to restrictive immigration policies, such as the Migration Protection Protocols (MPP or Stay in Mexico Program), the Department of Homeland Security’s metering policies, and Title 42 expulsions because of the COVID-19 virus. The situation under the Biden administration has not improved much, even though the current president ended MPP at the beginning of his tenure and despite a new, more favorable rhetoric regarding immigration coming from the White House. These advances notwithstanding, the reality is that the United States has maintained key restrictive immigration policies. In August 2021, the US Supreme Court decided that the Biden administration must comply with a lower court’s ruling to reinstate MPP (Barnes Reference Barnes2021). At the same time, Mexico has strengthened immigration enforcement, particularly on its southern border (Ugarte Reference Ugarte2021). This country continues cooperating closely with the United States to limit mass migration flows coming from the south of the continent.

Irregular migrants waiting on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border can easily become victims of murder, rape, extortion, kidnapping, and trafficking. In order to determine how to enhance the protection of migrants and reduce their risks of being trafficked—both at the border and along the migration routes—it is crucial to understand how cartels operate in these areas. While the connection between cartels, migrant-smuggling networks, and human-trafficking rings has been difficult at times to discern, due to conflicting reports and a lack of centralized oversight from Mexican and Central American authorities, this research has revealed important characteristics of such relationships. Further work needs to be done to theorize about these links and respective transmission mechanisms.

Perhaps most important, this study has found that the relationship between drug cartels and labor- and sex-trafficking rings seems to be mainly opportunistic. Such a relationship lacks any systematic or organized involvement by drug cartels in human trafficking, but instead is characterized by separate, specialized cartel operations with occasional collaboration. While these groups are not necessarily linked to one another through human-trafficking activities, they are intimately linked to migrant smuggling (Izcara Palacios Reference Palacios and Pedro2017). Along Mexico’s eastern migration routes, cartels and other criminal groups exploit migrants for various purposes, including forced labor, kidnapping, and extortion. While these purposes vary by region, they could eventually end up in or combine with human trafficking, due to an increase in migrant vulnerability.

When analyzing the factors that contribute to increased emigration from Central America, this study found that many migrants are motivated by violence and extreme poverty at home. Furthermore, these motivations significantly increase migrants’ vulnerability to human trafficking, partly because of a lack of protection from the government, corruption, and a weak rule of law. Justice systems in Mexico and Central America bear severe limitations, including lack of resources and inadequate enforcement of antitrafficking legislation, which prevent successful efforts to combat human trafficking (and particularly trafficking of migrants) in this region. These failures, combined with migrants’ economic and physical vulnerability, exacerbate migrants’ susceptibility to trafficking.

As a result of the implementation of MPP, tens of thousands of Central American migrants were placed at risk of being trafficked, and such conditions posed a deeply concerning threat to migrant livelihood. The partial closure of the US-Mexico border as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic and Title 42 expulsions greatly heightened the negative effects of MPP—terminated by Biden but reinstated by the US Supreme Court. The stalling of migrants at the border under this new restriction not only leaves them prey to poverty and disease, especially in light of the Coronavirus pandemic and lack of healthcare access, but also places them at risk of human trafficking, extreme exploitation, extortion, and other crimes committed by the actors analyzed in this article.

Mexico’s militarized approach to migration places migrants in further danger. After creating the National Guard out of military and police personnel, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador placed units along both of Mexico’s borders in response to pressures from the US government. There is evidence that the presence of the National Guard has led many migrants to utilize less frequently traveled migration paths, on which they are more likely to encounter criminal groups, including human traffickers (Meyer and Isacson Reference Meyer and Isacson2019). Moreover, Mexico’s kingpin strategy, implemented in the two previous administrations, while successful in debilitating some top cartel leaders, has also contributed to fragmentation of and violent struggles between drug cartels. This has exacerbated instability in the region and migrants’ vulnerability to trafficking (Beittel Reference Beittel2020).

Furthermore, Mexico’s uneven enforcement of punishments against human traffickers, as well as unreliable methods of reporting and seeking justice, represent considerable problems in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. With thousands of individuals being deported to various border cities in Mexico—several of which are locations for drug cartel activity—and thousands more waiting in these regions for their asylum cases to be considered, inadequate enforcement places thousands of migrants at risk of becoming victims of trafficking. Many of these migrants and asylum seekers lack housing and work and easily fall prey to individual criminals or organized crime efforts. This research demonstrates not only the ways the so-called drug cartels may take advantage of migrants but also an increased need to monitor the effects of US immigration policy on criminal activity in the region.

In this complex context, where the role of the state in aiding human-trafficking victims has been limited, we can think about some concrete policy recommendations. In the short term, it will be necessary for law enforcement to conduct more investigations into the corruption and violence in certain areas of Mexico and Central America. Reynosa, Matamoros, and Nuevo Laredo in Tamaulipas are particularly critical regions for further investigation. In these areas, cartel members have allegedly exploited deportees and migrants in transit and have also forced them to carry out criminal acts on behalf of their organizations (interview 6). Coatzacoalcos in Veracruz is another important area for investigation, as collusion between criminal organizations and state and local authorities there is evident (interview 14). Moreover, Cancún’s growing organized crime problem has yet to be investigated by Mexican authorities, who refuse to address human trafficking in the city in order to protect its tourism industry (interview 15). The criminal issues in these areas demonstrate the lack of accountability by state and local actors and a need to examine their activities.

In the long term, there are several potential ways that authorities could strengthen protection for migrants and deter activities of traffickers. Improvements to Mexico’s antitrafficking legislation should be made in order to raise these policies to international standards (Correa-Cabrera and Sanders Montandon Reference Correa-Cabrera and Sanders Montandon2018). The United States should also play a role in preventing human trafficking by considering alternatives to its deportation policy that stop or drastically reduce repatriations to cities where deportees are likely to be trafficked and exploited.

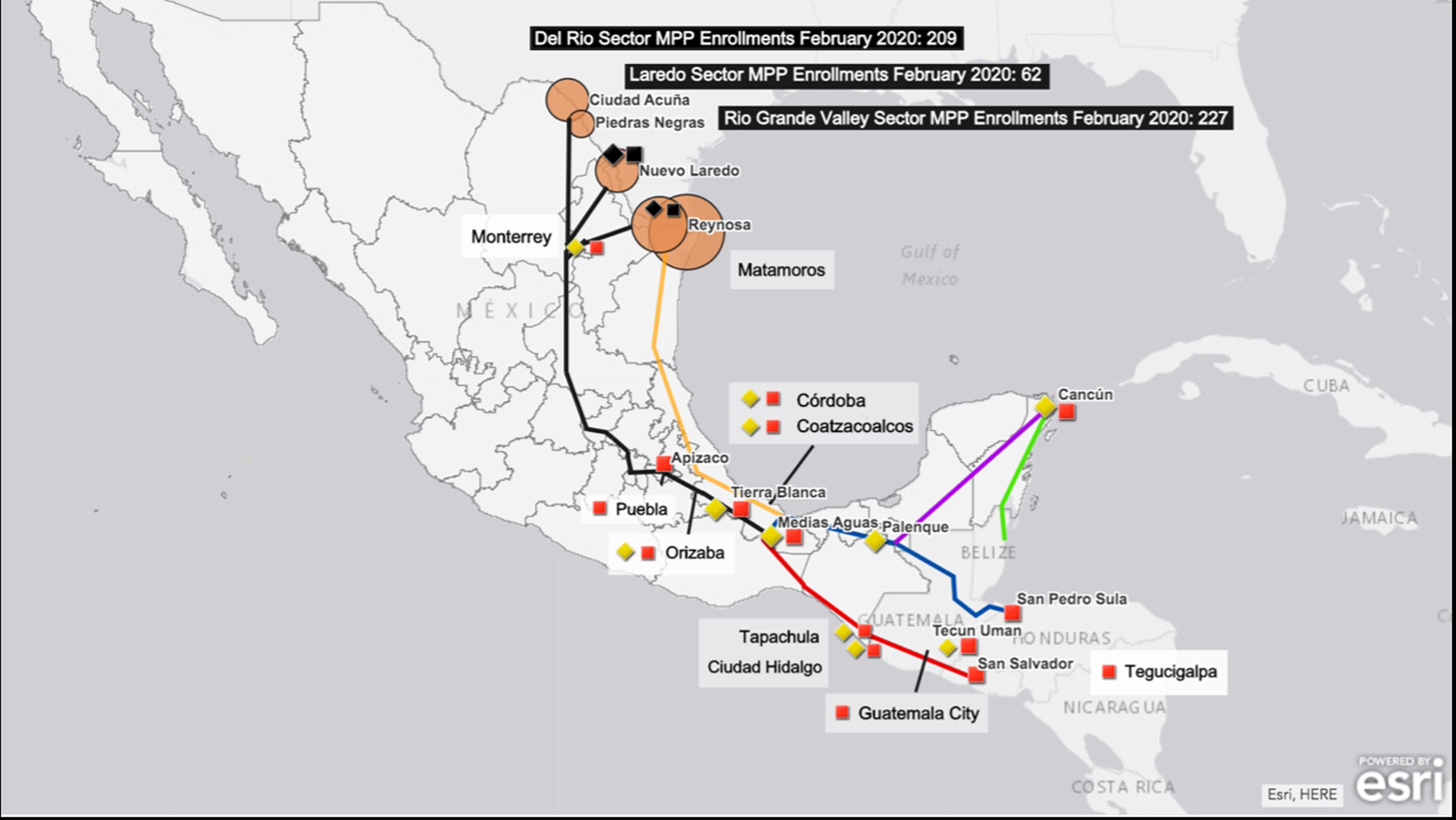

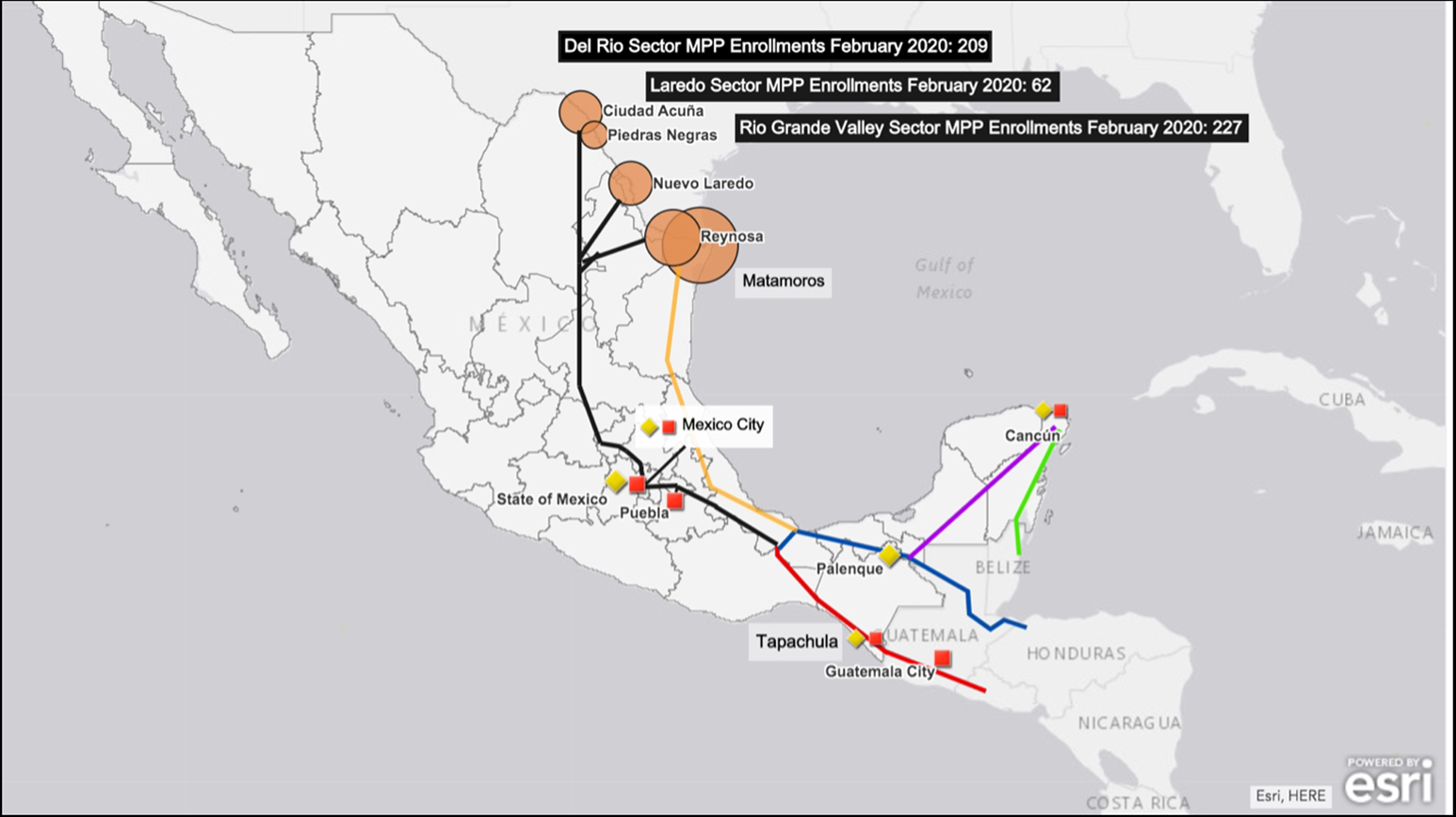

Appendix: Mapping Human Trafficking Along Mexico’s Eastern Migrant Routes

The following maps identify Mexico’s eastern migration routes, migrant shelters along the way, and the main human-trafficking hubs located along these routes (from the countries of the Northern Triangle to the Tamaulipas-Coahuila border with Texas). The aim of this section is to indicate the activities some migrants are forced to perform and the key regions where this happens. These maps differentiate international from domestic human trafficking in Central America and along Mexico’s eastern migration routes.

Map 1. Migrant Shelters Along Mexico’s Eastern Migration Routes.

Source: BBVA Research, Map 2020 of migrant houses, shelters, and soup kitchens for migrants in Mexico. https://www.bbvaresearch.com/en/publicaciones/map-2020-of-migrant-houses-shelters-and-soup-kitchens-for-migrants-in-mexico.

Map sources: Esri, DeLorme, HERE, MapmyIndia, Michael Bauer Research, GmbH, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Esri, World Light Gray Base (basemap), https://services.arcgisonline.com/ArcGIS/rest/services/Canvas/World_Light_Gray_Base/. Esri. Mexico Estado Boundaries 2018 (layer) https://services.arcgis.com/P3ePLMYs2RVChkJx/arcgis/rest/services/MEX_Boundaries_2018/FeatureServer.

Map 2. Sex Trafficking Along Mexico’s Eastern Migration Routes.

Sources: Information on sex trafficking: field research (May 2015–October 2016) [IRB approved April 22, 2015, #884206 (2015-100-09)]. Asylum waitlist. https://usmex.ucsd.edu/_files/metering-update_may-2020.pdf. Apprehensions. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions.

Map 3. Labor Trafficking Along Mexico’s Eastern Migration Routes.

Note: This map does not include compelled labor for criminal activity.Sources: Information on labor trafficking: field research (May 2015–October 2016) [IRB approved April 22, 2015, #884206 (2015-100-09)]. Asylum waitlist. https://usmex.ucsd.edu/_files/metering-update_may-2020.pdf. Apprehensions. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions

Map 4. Forced Labor for Criminal Activity Along Mexico’s Eastern Migration Routes.

Sources: Information on forced labor for criminal activities: Field research (May 2015–October 2016) [IRB approved April 22, 2015, #884206 (2015-100-09)]. Asylum waitlist. https://usmex.ucsd.edu/_files/metering-update_may-2020.pdf. Apprehensions. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions.