As international delegates launched the annual round of talks to decide which countries would take the available seats on the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in October 2019, Latin American candidates began to articulate in order to secure a place. Besides Brazil, which has the largest territory and population in the region, two other possible candidacies were introduced: Costa Rica and Venezuela. In the eyes of the world community, it is no secret that San José’s credentials in the realm of human rights promotion and protection far outweigh those of Caracas. Therefore, one could promptly infer, Costa Rica was bound to easily defeat Venezuela and claim this regional representation at the world’s highest human rights body. But at the end of the day, this did not happen (BBC World 2019).

Despite its domestic political situation, which includes abundant charges of human rights violations and arguably antidemocratic measures taken by President Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela was elected in 2019 to a seat on the UNHRC, garnering 105 votes against 96 for Costa Rica. Not to mention that, although most OAS (Organization of American States) members oppose Maduro’s government, a resolution condemning Venezuela’s human rights abuses could not be approved because of Caracas’s alliance system (Bahar et al. Reference Bahar, Piccone and Trinkunas2018). In sum, Venezuela’s Chavismo, a movement first led by then-president Hugo Chávez and now by Maduro, has displayed diplomatic strength, getting support both at the United Nations (UN) and the OAS.

In spite of the relatively radical nature of Venezuelan foreign policy under Maduro and Chávez (Giacalone Reference Giacalone and Beasley2013; Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2011), which has tended to move states away from the country, this level of political support enjoyed by Venezuela can be achieved through many diverse mechanisms—including diplomatic skills and ideological proximity. Chávez used all these tools to recruit allies. He supported, for instance, the Southern Cone Common Market (Mercosur), increasing Venezuela’s partnership with Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay—but that did not damage Venezuela’s long-established ties with Andean and Caribbean countries and institutions. He also took advantage of a period when left-wing leaders came to office in several countries in the region—the so-called Left Turn—thus producing ideological convergences between them to advance common foreign policy views.

After all, there was one more grand strategy behind these moves: the cultivation of a robust clientelistic network of international partners. It basically consists, as this article argues, of a structural arrangement, built up over the two decades under Chávez’s and Maduro’s rule, which enables Venezuela to exchange several favors and benefits, financial or not, for political support and deference from vulnerable actors, including votes and automatic alignments in international organizations. This network should not be mistaken for episodic, short-lived individual transactions between two or more countries. It involves a long-term link, in which clients become heavily connected and dependent on patrons over time (Nunes Reference Nunes1997; Veenendaal Reference Veenendaal2014).

Since the second half of the twentieth century, IR researchers such as Keohane (Reference Keohane1967) and Wittkopf (Reference Wittkopf1973) have been studying the vote market in international institutions. Some research works note that the United States was and still is the most frequent buyer in this market, exchanging money for political support since the Cold War. Afoaku (Reference Afoaku2000) associates patron-client dynamics with the US-waged campaign to export democracy and human rights to a very heterogeneous set of partners in the Middle East, Asia, Latin America, and Africa, while conceding that this stance always lacked coherence and consistency, as Washington seemed “often unprepared for the fall of polical clients abroad” (Afoaku Reference Afoaku2000, 37).

Another strand of literature sheds light on the US “foreign aid as foreign policy” strategy; that is, the weaponization of loans obtained from multilateral agencies for geopolitical purposes, which is perfectly applicable to Latin America even before the Cold War years (Taffet Reference Taffet2007). G7 countries are also among the most frequent “buyers” in this market, providing foreign aid, trade flows, and money lending from financial institutions to their allies (Dreher and Sturm Reference Dreher and Sturm2012). Along the same lines, one case to be further assessed in fuller detail is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—which was officially launched in the year 2017—and all the financial reliance on Beijing’s funds it has entailed so far, especially in Africa, inasmuch as BRI’s beneficiary countries may resort to massive long-term loans to gain economic leverage and bring some ambitious infrastructural projects to life (Fang and Nolan Reference Fang and Nolan2019; Maçães Reference Maçães2018).

Still, there is arguably in today’s Eurasia one phenomenon Obydenkova and Libman (Reference Obydenkova and Libman2019) have dubbed authoritarian regionalism, which alludes to Russia’s military maneuvers toward former Soviet republics; namely Ukraine and Georgia. It does this in order to secure unconditional allegiance—or to contain a perceived “westernization” of these countries, thus discouraging any prospective approximation between them and NATO or the European Union. This satellization of minor Eurasian countries is noticeable if one looks into the functioning of regional organizations like the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Eurasian Economic Union. But again, this is not what the Venezuelan experience is all about.

As Chávez took office and became politically stronger during his mandate, he increasingly implemented a “rebel” foreign policy, fiercely criticizing the existing global order. To propose alternatives to that order and implement his objectives, he increased the provision of foreign aid and foreign direct investment and used petroleum to get political support (Giacalone Reference Giacalone and Beasley2013). Not that this was an entirely original move in the history of Venezuela’s foreign policy. Since the early twentieth century, oil has played a decisive role in the country’s international positioning. Leaders as diverse as Rómulo Betancourt, Rafael Caldera, and Carlos Andrés Pérez explored Venezuela’s pivotal place in South America and reached out to Central American and Caribbean officials in an attempt to project Caracas beyond its territorial limits (Mijares Reference Mijares and Baisotti2021). But it clearly benefited Chávez that Venezuela has one of the largest oil reserves in the world and the price of this commodity soared during the 2000s, enabling him to pursue a position of regional leadership for his country (Romero and Mijares Reference Romero and Mijares2016). The president began to sell petroleum to strategic partners under very special repayment conditions and sponsored policies and projects in these countries (Sanders Reference Sanders2007; Cusack Reference Cusack2019; Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2011).

He also came up with alternatives to traditional institutions at all levels (domestic, regional, global); for example, the Bolivarian Alternative for Our American People (ALBA) and PetroCaribe, heavily based on Venezuelan oil shipments (Bryan Reference Bryan, Cooper and Shaw2009).Footnote 1 Chavistas became valuable partners to several Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries, providing benefits to improve their economic situation, given their vulnerabilities. Hence, according to the clientelistic framework, one could expect that the antisystemic attitudes adopted by Chávez and Maduro were promptly emulated to some degree by Venezuela’s main partners. However, unlike a tit-for-tat dynamic, Chávez’s alternatives consisted of long-term, loyalty-based projects. This is why we posit a clientelistic lens to properly analyze this phenomenon.

This article aims to investigate whether international clientelism was a mechanism through which Venezuela gathered political support from Latin American and Caribbean countries in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). We use votes at this forum as proxy variables to represent foreign policy orientations at large of their member states and to understand who their actual international allies are (see Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017). This article’s main hypothesis is that Chávez’s clientelistic attitudes would increase international political support to Venezuela during the “radicalization” of its foreign policy, a time when the ideological discourse was louder and sharper. Precisely, we expect this support to be more substantial in the main axes of Chávez’s foreign policy: anti-Americanism, sovereignty and self-determination, and the reduction of global asymmetries, translated into both economic and human rights policies. Therefore we use panel data for all Latin American and Caribbean countries from 1999 to 2015, together with qualitative evidence, to support our claims.

This article is organized as follows. First it provides an overview of the literature related to vote buying at the UNGA. While doing so, it proposes the operationalization of a concept that seems well suited to account for Venezuelan practices inside international organizations: international clientelism (Veenendaal Reference Veenendaal2014; Afoaku Reference Afoaku2000). While vote buying consists basically of a purely transactional “cash for vote” dynamic, clientelistic networks are firmly structured and loyalty-driven, including a variety of potential long-term benefits to would-be partners. The empirical research design and statistical tests are presented, followed by the qualitative evidence to support our findings.

The International Market of Foreign Policy Positions: Vote Buying and International Clientelism

Since the inception of the United Nations, analyzing voting patterns at the UN General Assembly has been the standard tool to infer states’ foreign policy preferences. UNGA is a forum where all the states of the world regularly meet to discuss matters, from the environment and gender to finance and security. Thus they provide scholars with “comparable and observable actions taken by many countries at set points in time” (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017, 2), an appropriate proxy to assess states’ preferences at the international level.

While trying to identify causes for states’ international behavior, several authors have identified correlations between voting patterns at the UNGA and the concession of foreign aid (see Keohane Reference Keohane1967; Wittkopf Reference Wittkopf1973; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008; Carter and Stone Reference Carter and Stone2015; Woo and Chung Reference Woo and Chung2017, among others). This phenomenon has become widely known in the literature as vote buying. The mechanism is relatively simple: a country offers (typically financial) benefits to another state, often under a “foreign aid” rubric, in exchange for support in the approval of a relevant resolution (or a set of them). The conditional concession of bilateral foreign aid is not the only UN vote-buying method. Dreher and Sturm (Reference Dreher and Sturm2012) note that countries that received more nonconcessional loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank tended to present higher voting similarity with the G7 countries. Since the G7 countries exert control over decisionmaking levers at both institutions, it is reasonable to infer that these actors could use their degree of influence to indirectly make both multilateral banks concede money to their allies.

Trade flows are also an indirect tool for UN vote buying. Keohane (Reference Keohane1967), Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008), and Stone (Reference Stone2004) point out that the concession of trade preferences may bring together two (or more) countries. Liberals claim, for example, that greater interdependence could lead to more similar opinions shared about a host of issues. On the other hand, the fear of losing access to markets may prevent a state from adopting some measures. Although higher trade dependence is not necessarily related to more significant political support, it can often be a useful tool to persuade one actor to vote according to another’s preferences at the UNGA.

These mechanisms are based on richer countries’ providing money in different forms to the poorer to get allies for their primary foreign policy purposes. However, in this article, we intend to go beyond this notion of cash for vote. Several Latin American and Caribbean countries are vulnerable in different senses—social, economic, military, and so on. This general weakness may give birth to dense clientelistic networks of political support (Stokes Reference Stokes, Boix and Stokes2009; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2000). For Martz (Reference Martz1997), this concept still lies at the heart of social practices in South American modern political systems. Although clientelistic practices basically consist of the exchange of material benefits for political support and are not necessarily programmatic—that is to say, they do not have to come attached with ideological or broad interest-based agreements—they will often involve some degree of allegiance and vassalage (Carvalho Reference Carvalho1997). Clientelistic networks relate to patron-client connections, in which clients will consistently support their patrons to gain certain benefits.

A conceptual note should be introduced regarding this notion. It should be emphasized that the sum of individual transactions involving two or more states is essentially different from a generalized scheme led by a patroncountry (a relatively powerful state, compared to its partners) to which clients (a group of vulnerable states) become strongly connected and dependent over time. Nunes (Reference Nunes1997) even associates clientelism with kinship, but not in a literal connotation. This sense of belongingness, of constituting a family of a kind, a community of fate and value, is arguably the bulk of a traditional clientelistic network, particularly in rural Latin America and the Caribbean (Martz Reference Martz1997). Having a long-term partner to mitigate vulnerabilities and protect against potential menaces allegedly is a key component to build ingroup confidence and familiarity.

Therefore, clientelism as a concept cannot be mistaken for a much simpler transactional, contingent, vote-buying dynamic. It always is context-based and covers the expectations of future, nonimmediate interactions between and among the parties. And this thick web of alliances that nurtures a successful diplomatic operation, we argue, has not failed Venezuela’s Chavismo as yet. Exchanging cash for money—what we called here vote buying—is only one possible way to establish links between “clients” and “support buyers.” Still, not every transaction of this sort may lead to a clientelistic relationship. As González-Ocantos and Oliveros (Reference González-Ocantos and Oliveros2019) note for the domestic level, it may also consist of repeatedly providing services and facilities for those who need them and other advantages in order to get frequent support.

Hence, our operational concept of international clientelism can be disaggregated into seven propositions—which, if properly met, will make up a clientelistic link.

-

1. Country A pursues a particular set of objectives in the international arena. The accomplishment of these objectives depends on political support from other states (especially on votes in international fora).

-

2. Country A gathers enough resources to afford the pursuit of these objectives on the international scene.

-

3. Country A decides to go beyond regular diplomatic negotiations, shared interests, and ideological convergences to get political support in international arenas. It decides to employ its own resources to provide other state(s) with benefits in exchange for political support.

-

4. Country B shows vulnerability or weakness at some substantive dimension, or in a given issue area, or on a particular situation.

-

5. Country A offers resources to address Country B’s topical vulnerabilities. They may include financial means, the provision of services, and even the building of facilities in Country B—but they are not limited to these options and must relate to long-term benefits, not only ephemeral ones.

-

6. Country B increases its political support to Country A in a concrete and consistent way: voting for and taking sides with Country A’s proposals. It does not depend on specific programmatic convergences. Even if Country B has a right-wing party or leader in power, it could easily vote for resolutions on defense of left-wing positions.

-

7. The political support from Country B to Country A remains not only for one or two sessions and not only for a few particular resolutions. It involves long-term ties related to Country A’s main foreign policy objectives.

Figure 1 summarizes the building up of a clientelistic link between any two countries. These links can simultaneously reach several countries, thus transforming these bilateral connections into a far-reaching and deeply rooted clientelistic network.

Figure 1. Building a Clientelistic Link Between Two Countries.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Considering the particular strategy Hugo Chávez put forth, especially in providing oil and other facilities to LAC countries, and this theoretical argument, three hypotheses arise regarding the Venezuelan action in the region.

H1. Members of the Venezuelan clientelistic network will vote more similarly to the country than will nonmembers.

If increased political support is the main objective of building a clientelistic network, then one could expect LAC countries that received advantages from Venezuela to present a voting behavior more similar to that of their patron after receiving the related benefits.

H2. This voting similarity will predominantly occur with regard to leading Venezuelan foreign policy topics.

As mentioned, one of the main conditions for a country to engage in creating a clientelistic network is the existence of foreign policy objectives that can be achieved only through foreign support. Therefore, if our theoretical proposition is correct, the network will be built on key values for the patron and, as a consequence, an increased voting similarity among the patron and its clients will be observed on these topics. In the case of Venezuela, as noted, these issues should be anti-Americanism, sovereignty and self-determination, the reduction of global asymmetries, translated into both economic and human rights policies.

H3. Clientelistic networks work primarily for vulnerable countries.

The provision of benefits in exchange for foreign policy support tends not to work with larger and richer countries because the offers tend not to be attractive. In contrast, vulnerable countries, especially in the economic sense, will adhere to clientelistic networks because these promise to address their vulnerabilities.

Before proceeding to empirical tests, we cannot ignore our main alternative hypothesis. While Chávez was establishing his clientelistic network in the region, left-wing leaders were taking office in several LAC countries. The Venezuelan president was the first of these. Some scholars (Levitsky and Roberts Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011; Potrafke Reference Potrafke2009; Amorim Neto and Malamud Reference Amorim Neto and Malamud2015; Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017) perceived that the political orientation of the head of government influences a country’s voting behavior at the UNGA. According to these authors, when it comes to foreign policy positions, left-wing governments, especially in Latin America, have moved away from the United States over the years.

Riggirozzi and Grugel (Reference Riggirozzi and Grugel2015), Merke et al. (Reference Merke, Reynoso and Schenoni2020), and Wiesehomeier and Doyle (Reference Wiesehomeier and Doyle2012) note that changes in foreign policy behavior in Latin American countries under left-wing presidents also included supporting the reduction of inequalities worldwide, the criticism of liberal institutions, and a renewed discourse with an emphasis on national sovereignty. These claims are similar to Chávez’s foreign policy principles, even if not displaying the same level of intensity and virulence; authors such as Levitsky and Roberts (Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011) and Castañeda (Reference Castañeda2006) consider the Chavistas too radical as compared to other left-wing leaders. If this is so, the “left turn” in the region leads us to the following alternative hypothesis:

H4. Latin America’s left turn triggered more similarity in foreign policies between Venezuela and Latin American countries with left-wing governments in office, mostly due to their ideological convergence.

Empirical Strategy

We relied on a database containing information for all Latin American and Caribbean countries from 1999 (Chávez’s first year in office) to 2015. We utilized a three-step methodology to empirically test our theory. First, we ran panel data analysis to identify the effects of our proposed mechanism: international clientelism. This first step intends to show that Venezuela was able to gather political support for Chávez’s foreign policy through clientelistic means (H1), as well as to test the alternative hypothesis (H4). As we are talking about a clientelistic network, we also provide further evidence using network analysis. In the second step, we tested for H3 using logistic regressions to assess the role of vulnerabilities in allowing for countries’ adherence to the Venezuelan clientelistic network. Finally, we used panel data to investigate our H2. Summary statistics and robustness checks are available in the supplementary materials.

Dependent Variable

We assessed foreign policy positions from LAC states by evaluating the voting similarity between Venezuela and these countries in each year as the dependent variable, either overall or by issue areas. We relied on Voeten et al.’s Reference Voeten, Strezhnev and Bailey2009 database, updated in 2020, containing votes for all countries at the UNGA since 1946. The voting agreement was calculated using Thacker’s 1999 procedure. For every resolution, we attributed a score of +1 when Venezuela and a LAC country voted in the same way, 0 when they disagreed over a resolution, and +0.5 when one of them abstained. Absences were not considered because, as Voeten (Reference Voeten and Reinalda2013) notes, they tend not to be related to foreign policy preferences but to other factors beyond their control, such as civil wars or the temporary lack of government. Then we totaled the scores for all resolutions of each country in a year and divided the result for the annual number of resolutions.

Key Independent Variable

Chávez proposed at least two Venezuelan-led alternatives to the existing multilateral institutions in order to implement his foreign policy objectives: ALBA in 2004 and PetroCaribe in 2005. These institutions were based on a “solidarity mechanism,” in which each member should provide what it could and receive what it needed. As both programs involved the exchange of benefits provided by Venezuela, which would be the “paymaster” in the two cases (Giacalone Reference Giacalone and Beasley2013), these institutional alternatives provide us with a useful option to assess membership in the analyzed clientelistic network in an objective and comparable way.

The first of these institutions was ALBA. It included financial aid and cooperation involving oil by Venezuela, while other governments provided what they could; Cuba, for example, contributed health services and goods. However, we cannot consider ALBA membership as a determining condition for the membership in the Venezuelan clientelistic network because, despite the exchange of benefits, it also had a strong ideological component. ALBA members were supposed to agree and manifest alignment with Chávez’s “twenty-first-century socialism” and were essentially left-wing governments (Cusack Reference Cusack2019; Belém Lopes and Faria Reference Belém Lopes and Faria2016; Raby Reference Raby2011; Girvan Reference Girvan2011). Therefore, since we cannot accurately identify the mechanism operating behind ALBA, we may not consider it as a treatment variable but rather as a control one, containing a hybrid mechanism combining ideology and clientelism.

The same does not apply to PetroCaribe. It consisted of a mechanism through which special conditions were provided for its signatories to buy Venezuelan oil and petroleum products, not to mention that energy projects in these countries were financed by Chávez’s and Maduro’s governments (Sanders Reference Sanders2007). The agreement offered two primary benefits to its signatories. One was cheap credit and advantageous conditions to acquire Venezuelan oil, with the possibility to finance about 40 percent of oil shipments for 25 years, with an interest rate that was below market value (1 percent per annum). It could also be repaid with other means, such as food and medical services (Cusack Reference Cusack2019; Giacalone Reference Giacalone and Beasley2013). The other benefit was funding for development initiatives in these countries by allowing PetroCaribe members to invest in projects with “social purpose,” especially the money they would not spend acquiring oil at that moment because of such special conditions. Also, Venezuela would arguably provide money for some projects in those countries (Cusack Reference Cusack2019; Giacalone Reference Giacalone and Beasley2013).

While ALBA had an underlying ideological component, PetroCaribe had not. PetroCaribe was first offered to all LAC countries (under the rubric PetroAmérica) and finally was accepted only by the Caribbean and Central American countries. One cannot claim that signing PetroCaribe was a reward for political support, since the mechanism was offered for the entire region. Contrary to ALBA, non–left-wing governments also joined the PetroCaribe agreement, like Belize, Grenada (under Tillman Thomas), and Honduras (under Porfírio Sosa). Figure 2 presents countries that joined these institutions at any point in time—some of them joined both institutions later, while others left before 2015.

Figure 2. ALBA and PetroCaribe Membership.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Therefore, we used PetroCaribe membership each year to assess countries’ belongingness to a Venezuelan clientelistic network. It is a dummy variable—countries can be members (1) or nonmembers (0) for each year under assessment. ALBA, considered here as a control variable because of its hybrid mechanism, received the same score attribution treatment. We also considered PetroCaribe members those countries that signed the agreement and received Venezuelan oil at any time.Footnote 3 To identify oil shipments under the agreement’s umbrella, we relied on annual official reports from Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA).Footnote 4

Control Variables

Together with ALBA membership, which received the same codification procedure as PetroCaribe, we controlled for variables based on the literature as conditioners of voting in the UNGA. First, the United States remains an important actor in the vote-buying market, making it essential to control for this variable (Alesina and Dollar Reference Alesina and Dollar2000; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008). As we expect Venezuela to gather political support against the United States, we can also expect that US action in this market moved LAC countries away from the Chavistas.

We assessed the US action in three ways, following the vote-buying literature (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008; Flores-Macías and Kreps Reference Flores-Macías and Kreps2013). First, we measured each country’s trade flow with the United States. We looked for the log of both imports and exports (respectively coded as logusimport and logusexport). Data were obtained from the US Census Bureau. We also tested the US foreign aid effect, based on the log of values to which the US government was committed, instead of actual disbursements (coded as logusaid). We chose this option because a promised value may not be delivered to a country as a punishment for disagreement over some topical question. It could eschew the estimation, since the amount received would be a consequence of the country’s voting behavior, not its actual cause. Data were retrieved from the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

According to Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008), more democratic nations are likelier to follow the US recommendations in the General Assembly. The authors adopt the Freedom House index of democracy, based on civil liberty and political rights, to infer how democratic a state is. Considering such a Western approach (based on the notion of liberal representative democracy), we assume that countries with a higher score are more similar to the United States on political grounds. Consequently, they tend to support Washington in foreign policy moves. We also used Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Index and coded it as dem (Freedom House 2019). Lower counts flag countries as more democratic than the average.

We also tested for the alternative hypothesis: left-wing governments tended to present higher voting similarities with Chávez’s Venezuela (Potrafke Reference Potrafke2009; Amorim Neto and Malamud Reference Amorim Neto and Malamud2015; Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017). Lacking a classification that included all the Latin American and the Caribbean governments in the analyzed period, in order to objectively identify the ideologies behind each government, we considered as left-wing the presidents and prime ministers whose parties were members of the Foro de São Paulo or the Progressive Alliance in each year, considering that these organizations include all Latin American associations often mentioned by scholars who study the Left Turn (Castañeda Reference Castañeda2006; Levitsky and Roberts Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011; Riggirozzi and Grugel Reference Riggirozzi and Grugel2015).

This criterion may not perfectly fit most parties in the Caribbean, since there is not just “one left” in LAC countries. Left-wing organizations in these countries have very different trajectories, especially when we consider that these are long-lasting movements, originated at the beginning of the twentieth century, rooted in race and colonial struggles. Most of these states would become independent only during the 1960s, 1970s, or even 1980s. Therefore, to better classify parties from these nations, we rely on Mars’s 1998 classification of political parties in the region. The variable was coded as polori and consists of a dummy variable: governments that met these requisites were considered to be leftist and received a score of +1. The others were given a score of 0. Summary statistics for all variables are available in the online appendix, as well as a detailed description of the codification on the political orientation.

Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008), Dreher and Jensen (Reference Flores-Macías and Kreps2013), Flores-Macías and Kreps (Reference Dreher and Jensen2013), and Amorim Neto and Malamud (Reference Amorim Neto and Malamud2015) note that states’ capabilities, especially the economic ones, may affect their voting behavior—which matches H3. However, controlling for the country’s size is harder because we use models in which time-invariant variables are not useful, and capabilities vary too little over 15 years in LAC countries, except for the economic ones. We included GDP as a control in our models to better address this issue, using data from the World Bank, coded as loggdp. While testing for H3, we also relied on each country’s population size (logtpop) and oil rents, as a percentage of the GDP (oilrent). Both these indicators were also obtained from the World Bank. Finally, as we are dealing with a period in which oil prices skyrocketed, we also controlled for this variable, using data retrieved from Our World in Data. Detailed variables, codes, and sources are available in the supplementary material.

Results

Did membership in the Venezuelan clientelistic network lead to an increased voting similarity at the UNGA? We begin by testing H1—meaning that the membership in the Venezuelan clientelistic network, proxied by the variable PetroCaribe, is expected to deliver greater voting similarity with Venezuela since the year 1999. In this section, we also tested for the alternative hypothesis (H4); that is, ideological similarities should lead to more voting convergence. Descriptive evidence, available in figure 3, provides empirical support to both claims.Footnote 5

Figure 3. Latin American and Caribbean Countries’ Voting Agreement with Venezuela, 1999–2015.

Note: Measured according to the statistical means of political orientation and Venezuela-led institutions membership.Source: Authors, based on Voeten et al. (Reference Voeten, Strezhnev and Bailey2009).

As we can see, as Chávez’s foreign policy became more radical during the 2000s, there was a general trend to reduce voting similarities between LAC countries and Venezuela. Considering that, we can observe that both PetroCaribe signatories and left-wing countries were the ones that voted more similarly to Venezuela since then, as well as those ALBA members. That is, in a context of increasing voting divergence between LAC countries and Chávez’s government, political orientation and membership in Venezuela-led institutions seemed to play a role in reducing these disagreements. This finding provides evidence to the idea that both hypotheses tend to be correct. Also, figure 3 suggests that one mechanism (ideology or clientelism) does not depend on the other to work. Both PetroCaribe members with non–left-wing governments and PetroCaribe nonmembers ruled by left-wing leaders voted more similarly to Venezuela than those that do not present any of these characteristics. We can also observe that, looking only at left-wing governments, PetroCaribe members presented increased voting similarity to Venezuela, and the same applies to non–left-wing governments.

These descriptive findings are confirmed by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) models, including fixed effects for countries and years, having voting similarity with Venezuela as the dependent variable.Footnote 6 Results are available in table 1. PetroCaribe effects proved to be significant whatever the specification is. In model 2, we controlled for political orientation and membership in ALBA. As we expected, left-wing governments tended to move LAC countries closer to Venezuela. Also, both ALBA and PetroCaribe produced significant effects. These results, which were corroborated by all models, provide strong evidence for both H1 and H4. As ideology and international clientelism are not mutually exclusive mechanisms, we can accept both hypotheses.

Table 1. Effects of Venezuelan Clientelistic Links on Voting Agreement with Venezuela

*p < 0.1. **p < 0.05. ***p < 0.01.

Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses, clustered by country. Models 1 to 6 include country and year fixed effects. Model 7 includes only country fixed effects, because oil prices are a unit-invariant variable.

As for model 3, we controlled for economic relations with the United States, the political regime, and economic development over time. Exports to the United States and the foreign aid provided by the great power proved to be a significant factor, moving LAC countries away from Venezuela—and probably closer to the United States. In model 4, we used all variables, while in models 5 and 6, we included interactions between PetroCaribe and ALBA and PetroCaribe and the political orientation variable, respectively. Results show that the agreement effectively produced political support for the Chavistas independently of the recipient’s ideology—in other words, ideology and clientelism are not mutually exclusive mechanisms and can even work in tandem.

In model 7, we substituted year fixed effects for the yearly average oil price per barrel and interacted it with PetroCaribe membership. When we look only at the oil prices, results show that the higher the value, the less the voting similarity between LAC countries and Venezuela. This is expected because, at the same time this value skyrocketed, Chavistas were adopting a radical foreign policy, consequently different from all other states’ regular practices. However, results also show that as these prices rose, PetroCaribe signatory countries shifted to a greater voting convergence with Venezuela than the convergence found with nonsignatories, thus providing more evidence for H1. These results are all supported by the robustness checks available in the supplementary material.

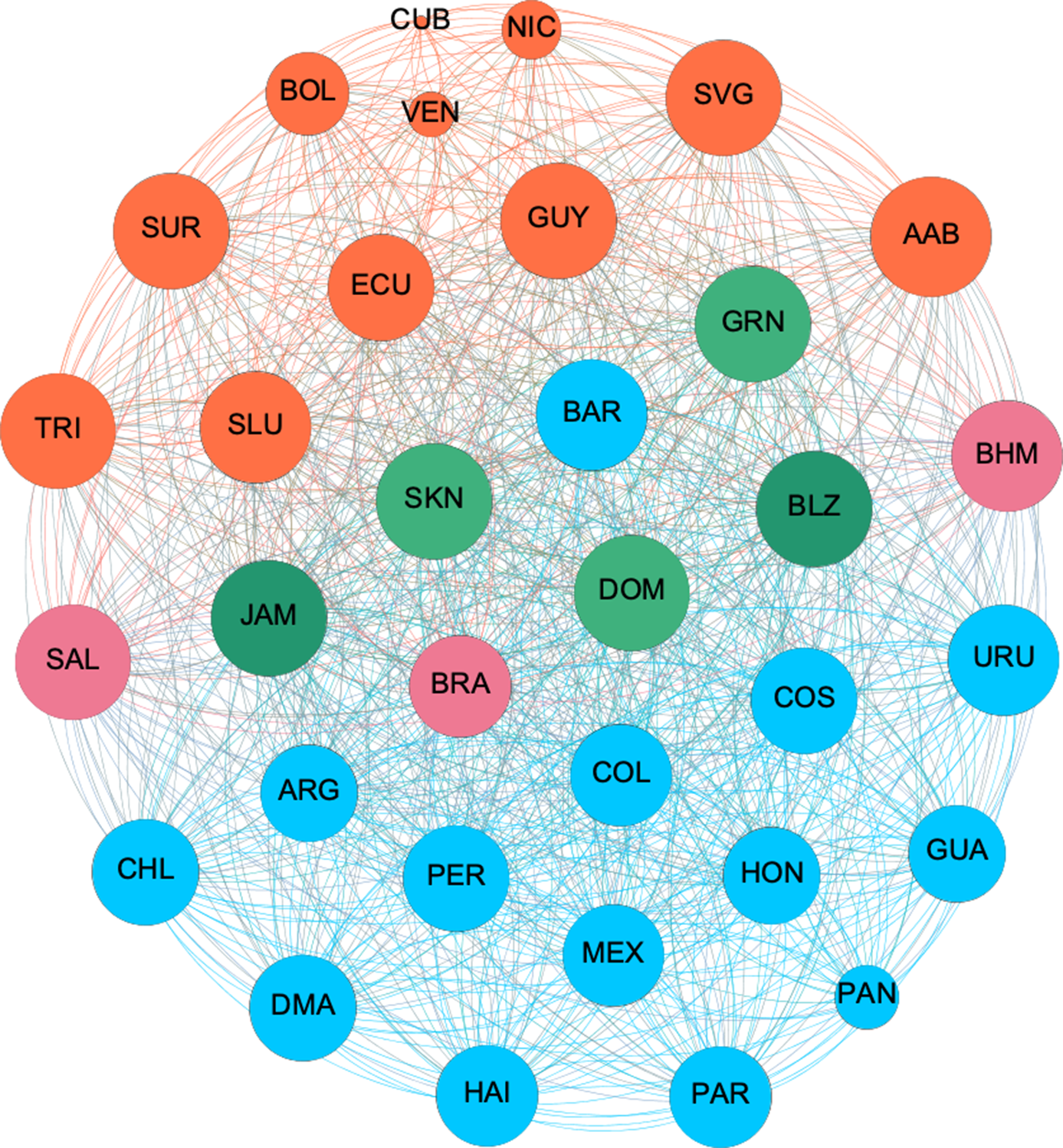

The Venezuelan clientelistic network can also be observed while relying on a network approach, as we show in figure 4. We applied a descriptive network analysis, intending to provide evidence that clientelistic practices gave place to a real network of clients based on Venezuela’s Chavismo. Each country is represented as a node—a vertex; that is to say, a point in the network—and when they agree with each other above an established threshold, they become connected by edges—lines linking nodes (Wasserman and Faust Reference Wasserman and Faust1994; Newman Reference Newman2010). As Venezuela is the case study of this article, we mobilized the median of the agreement score between LAC countries and Venezuelan governments from 2008 to 2015 as a threshold to determine the existence of edges between two nodes—which was precisely 0.8959. Whenever the voting agreement between two states was equal to or higher than this value, we considered them connected in the network.

Figure 4. A Network of Voting Agreement Between LAC countries, 2008–2015.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, based on Voeten et al. (Reference Voeten, Strezhnev and Bailey2009).

We considered the period from 2008 to 2015 to provide a sufficiently good depiction of this phenomenon. During this time window, almost all PetroCaribe members had already signed the agreement and received subsidized oil shipments, making it arguable that vote buying was in progress. Then we considered the mean agreement score between each dyad (made up of LAC countries) for the timeframe of this analysis, using Voeten et al.’s (Reference Voeten, Strezhnev and Bailey2009) data.

We used two network statistics in the graph that allowed the data to meet the conditions in order to reach our conclusions. The first one was the degree of a vertex, applied to the size of each node. According to Newman (Reference Newman2010, 9), “the degree of a vertex in a network is the number of edges attached to it.” Therefore, the greater the node, the larger the set of countries that present a voting similarity of at least 89.59 percent, considering the stock of UNGA resolutions. The second condition was modularity, as applied to the color of each node. Modularity indicates particular divisions within networks by comparing the actual number of existing edges within groups with an expected number within simulated networks with random edges. Based on these measures, we can statistically assess group divisions in the network under analysis (Newman Reference Newman2006, Reference Newman2010). Therefore, node colors represent belongingness to specific groups.

One can promptly infer that more radical left-wing governments—Cuba, Nicaragua, Bolivia, and Venezuela (Castañeda Reference Castañeda2006; Levitsky and Roberts Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011)—display a lower degree as compared to other nodes. This demonstrates that fewer states tended to agree with states that adopted radical postures on UNGA resolutions. This network suggests the existence of five groups: one that is relatively apart from Venezuela (in blue), one comprising close Venezuelan supporters (in orange), and three middle-ground groups (represented in green and in pink). The clientelistic network might include member countries from the latter four groups.

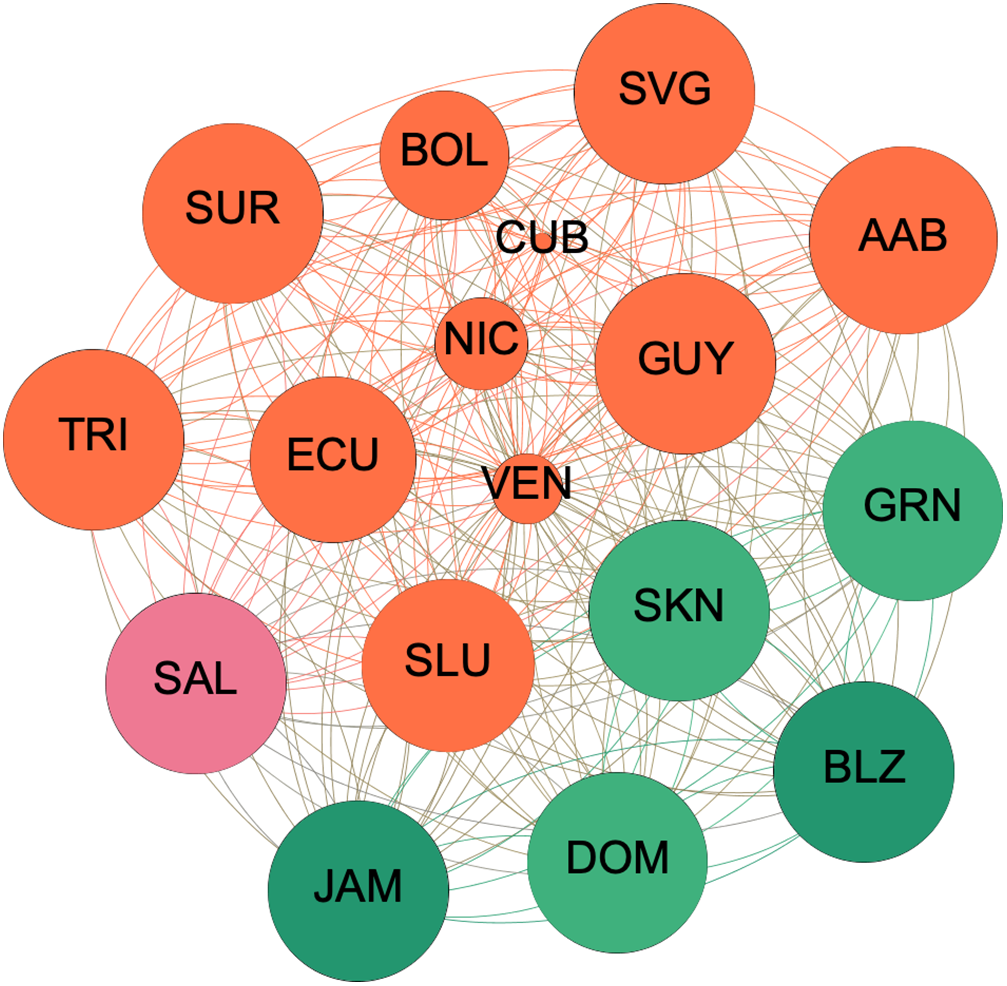

The Venezuelan ego-centered network allows for a more accurate diagnosis. We present it in figure 5—maintaining the same node sizes and colors as in figure 3. First, there is a group based on ideological support of Chavistas, including Bolivia, Cuba, Ecuador, and Nicaragua. Second, there is another group in which support is based on clientelistic instruments, made up of Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Suriname. We acknowledge that some of those countries had left-wing governments in office and even some of Chávez’s sympathizers, such as Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. However, as we have shown in our previous section, ideological convergences do not nullify the effect of clientelism, allowing us to infer that this was the clientelistic network built by Hugo Chávez’s (and eventually Nicolás Maduro’s) Venezuela paying dividends.

Figure 5. Venezuelan Ego-centered Network.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, based on Voeten et al. (Reference Voeten, Strezhnev and Bailey2009).

Therefore, we can affirm that both ideological convergences and international clientelism were significant mechanisms to produce political support for Venezuela, and even that the latter gave birth to a network of Chávez’s and Maduro’s clients. In other words, we can consider H1 and H4 corroborated. In the context of decreasing agreement between LAC countries and Chavistas, mostly due to radical foreign policy measures implemented by Caracas, each of these instruments helped to maintain voting coincidence between Venezuela and LAC countries at the UNGA by around two percentage points higher than the expected.

Did vulnerability play a role in the construction of the Venezuelan clientelistic network? Descriptive statistics provide evidence for H3—that is, greater state vulnerability leads to increased efficiency of the clientelistic network. As we show in the supplementary materials, 15 out of the 20 smallest LAC economies in the region adhered to at least one of the Venezuelan cooperative schemes between 2004 and 2015. On the other hand, considering the other 12 largest economies, only 3 effectively joined at least one of these arrangements: Cuba and Ecuador, which had radical left-wing governments at the time, and the Dominican Republic, which was also ruled by a left-wing president (Levitsky and Roberts Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011).Footnote 7 Preliminary evidence shows that vulnerability led the poorer countries in the region to adhere to Venezuelan-led institutions.

This argument is corroborated by the logistic regression models in table 2. We used data from 2005 to 2015 because both institutions—ALBA and PetroCaribe—did not exist before this time period. We also ran separate tests for a subsample, including only the Central American and Caribbean states. As our objective was to provide cross-sectional evidence about the role of vulnerability, we did not use fixed effects. Results show that as states’ GDP grow higher, the probability of their adhering to either ALBA or PetroCaribe decreases. Oil rents seem not to have effects on the admission to either institution, while the size of the population unexpectedly seems to play a role regarding PetroCaribe. In the end, the link between vulnerability and adherence to the Venezuelan clientelistic network was corroborated. In order to provide an additional test for it, we also ran models interacting the log of the GDP with the political orientation of each government in the region. The predicted effects are illustrated in figure 6.

Table 2. Effects of Vulnerability on Adhering to PetroCaribe and ALBA

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Figure 6. Marginal Effects of GDP on the Probability of Becoming a Member of ALBA and PetroCaribe.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The results fit our theory and provide more evidence for H2. Regarding PetroCaribe, when we look at the poorer countries, the probability of their signing the agreement is near 100 percent, regardless of the government’s political orientation. Ideology will only play a role with medium-income states, while richer states will not adhere to the institution. Economic vulnerability is thus a valuable condition to understand PetroCaribe membership. In the case of ALBA, economic vulnerability will play a role in regard to the poorest countries. However, as the GDP increases, adherence to the institution will be conditioned on the existence of a left-wing leadership. The “hybrid mechanism” behind ALBA—partly ideological, partly clientelistic—can thus be inferred. Therefore, we consider H3 to be corroborated. Vulnerability was a key component for the Venezuelan clientelistic network to work, in the sense that low GDPs produced higher probabilities to sign the agreement and led to an increasing voting similarity with the patron.

Was the increased political support related to the main Venezuelan foreign policy topics?We provide evidence for H2—that is, that increased political support provided by the Venezuelan clients centered on the leading Venezuelan foreign policy topics. Table 3 disaggregates voting behavior in specific thematic areas as per Voeten et al.’s (Reference Voeten, Strezhnev and Bailey2009) classification in six different categories: human rights, economic development, colonialism, the Palestinian conflict, nuclear materials (including nuclear weapons), and arms control and disarmament.Footnote 8 We also estimate the effect of Venezuelan practices for a voting alignment on resolutions considered important by the US State Department. We use OLS regressions with country and year fixed effects in all models.

Table 3. Effects of Venezuelan Clientelistic Links on Latin American and Caribbean Countries’ Voting Agreement with Venezuela at the UNGA, by Thematic Area

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Robust standard errors are in parentheses, clustered by country. All models include country and year fixed effects.

When we disaggregate votes by thematic areas, we can observe some interesting additional findings. US economic influence tends to have almost no impact in separate thematic areas. The only perceived effect was that of the US foreign aid provision in moving countries away from Venezuela on resolutions considered priorities according to the US State Department. Also, we can perceive that the less democratic or the more prosperous a country becomes, the more it moves away from Venezuela’s pattern when colonialism is concerned. In contrast, wealthier countries voted more similarly to Chavistas on economic development issues, suggesting that wealthier countries uphold a different economic system.

Left-wing countries voted more similarly to Venezuela in resolutions connected to human rights, colonialism, and the Palestinian conflict, as well as in those considered to be important by the United States. As noted, this is expected to be connected with foreign policy changes in Latin America during the Left Turn (Riggirozzi and Grugel Reference Riggirozzi and Grugel2015; Belém Lopes and Faria Reference Belém Lopes and Faria2016). ALBA members tended to present increased voting coincidence with Chavistas on human rights, economic development, and matters important for the United States, which also meets our expectations regarding the coexistence of ideological and financial interests to drive countries’ choices.

The results also provide strong evidence for our H2. PetroCaribe drove its members closer to Venezuela in priority areas of Chávez’s foreign policy: socioeconomic asymmetries (human rights and economic development), sovereignty and self-determination of the peoples (colonialism and the Palestinian conflict), and US hegemony in the world (important resolutions for the United States). On the other side, although the agreement on arms control resolutions proved to have some level of significance in model 6, it could not be sustained in our robustness checks, as in the case of nuclear matters. It was an expected outcome because these two areas did not appear as priorities in Chávez’s foreign policy.

Therefore we can conclude that Venezuela was able to acquire political support from small or vulnerable countries from Central America and the Caribbean in order to implement Hugo Chávez’s foreign policy. It is important to consider this result within the context of the Left Turn in Latin America. While the foreign policy implemented by the Chavistas tended to move LAC countries away from Venezuela in international fora, ideological convergences allowed for some increased support for Chávez’s projects. When this mechanism was not present or sufficient to gather support and nations displayed vulnerabilities, then Venezuela was able to deploy international clientelistic measures to secure itself allies. Even when there were left-wing governments in office, Chavistas were able to increase support for their ideas with clientelistic practices.

Qualitative Evidence: The Venezuelan Oil-based Diplomacy Under Chávez and Maduro

Having corroborated all hypotheses through statistical tests, we now present further qualitative evidence on our causal mechanism, international clientelism. It is important to acknowledge that Venezuelan oil-based diplomacy was not invented during Chávez’s rule; it dates from the first part of the twentieth century. Even the provision of oil benefits and subsidies to LAC countries was not new; the San José Accord, signed in 1980, is a previous example of this kind of agreement (Ewell Reference Ewell1982; Trinkunas 2008; Reference Trinkunas, Clem and Maingot2011; Clem and Maingot Reference Clem and Maingot2011; Giacalone 2013). These precedents notwithstanding, what was new in the Venezuelan foreign policy that allows us to talk about international clientelistic practices?

First, Venezuelan foreign policy objectives were drastically different. Chávez implemented a highly antisystemic and anti-American policy, while most of its predecessors were somehow pro-American. Implementing a pro-American (or, at least, a non-antisystemic) policy did not require a clientelistic network because several other variables were acting on these objectives (such as US action). When it was not the case (i.e., during Carlos Andrés Pérez’s rule), there were no conditions at all to go beyond instruments such as diplomatic negotiations, shared interests, and ideological convergences to get international political support, for several reasons, such as international and domestic contexts and constraints—that is, lack of internal support (Clem and Maingot Reference Clem and Maingot2011; Trinkunas Reference Trinkunas, Clem and Maingot2011).

Second, we lack evidence on points 6 and 7 of our concept to consider previous experiences as clientelistic. There is no evidence of persistent political support by Venezuela that was rewarded with international political support, independently of the programmatic convergences. On the contrary, Venezuelan support of democracy in the region, for example, found its partners in programmatic links (i.e., democracy-prone states). Therefore, we cannot relate Venezuelan petrodiplomacy before Chávez to an international clientelistic network.

Therefore the focus shifts back to PetroCaribe. Although the agreement was offered to all Caribbean and most Central American countries, some received this initiative with caution. Barbadian representatives refused to join the initiative with the justification that it would generate fiscal debt to the country—a loan facility. In Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, while the government in charge signed the agreement, the leader of the opposition party and former prime minister, James Mitchell, criticized the alliance with Venezuela. In the case of Saint Lucia and the Bahamas, prime ministers who took office after the agreement was signed decided not to pursue membership in the institution (Sanders Reference Sanders2007).

At the same time, several countries in the region welcomed the agreement, which they believed could benefit them. After his interviews with officials from Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Girvan (Reference Girvan2011) noted that the main benefit for the members of the Venezuelan-led initiatives, in their opinion, was the financial cooperation. In some cases, these countries did not even have the specialized workforce to deal with bureaucracies and request money from other institutions, such as the IMF and the European Union.

Regarding policymakers’ perceptions about these initiatives, as the former Honduran minister for planning and foreign cooperation, Arturo Corrales, summarized it: “PetroCaribe is a trade mechanism, strictly commercial, while ALBA is a political mechanism” (Efe 2011). Corrales was a member of a non–left-wing government, as was the former Jamaican prime minister, Bruce Golding, who, according to Clem and Maingot (Reference Clem and Maingot2011, 108), saw PetroCaribe as “a purely business arrangement.” Thus, we can reinforce the claim that while ALBA presents a hybrid causal mechanism, PetroCaribe focuses on the exchange of benefits.

According to the Latin American and the Caribbean Economic System (SELA 2015), from 2005 to 2014, Venezuela funded 432 projects in the region through PetroCaribe, in fields as diverse as infrastructure, housing, agriculture, education, and health services. Just to mention some examples, Girvan (Reference Girvan2011) and Cusack (Reference Cusack2019) show that St. Vincent and the Grenadines received money to build a new international airport and a fuel storage plant, while Dominica received EC$40.2 million for low-income housing projects. Sewage and road infrastructure were also improved in the country through PetroCaribe. Plants to store and distribute oil were built in Nicaragua, St. Kitts and Nevis, El Salvador, and Grenada (SELA 2015). In Jamaica, improvements in the Norman Manley International Airport, the Petrojam refinery, and docks, as well as the refinancing of Jamaican public debt, were all funded through PetroCaribe mechanisms (Transparencia Venezuela 2013). Last but not least, we need to mention that the increasing improvement in social conditions and spending was also reflected in the popularity of the domestic heads of government, allowing them to get re-elected (Cusack Reference Cusack2019). Hence, PetroCaribe not only consisted in a typical cash for vote instrument but included a broad set of benefits and facilities provided to its members. And they were not tit-for-tat exchanges but long-term advantages provided by the patron all along the analyzed period.

Chavistas’ clientelistic actions produced changes in regional leaders’ attitudes beyond UN votes perceived during the 2000s. The former US secretary of state Hillary Clinton noted that after getting Venezuelan benefits, “Eastern Caribbean leaders [had] been more outspoken—and some unusually critical of the United States when praising Venezuela” (US State Department 2009). For example, the Antiguan prime minister, Baldwin Spencer, who was seen as a “fairly calculating pragmatist,” surprised US diplomats by saying that “Latin America and the Caribbean have suffered greatly as a result of coercive and imperialistic models of colonialism and later the Washington Consensus” (Embassy Barbados 2009). Another illustrative comment was provided by the Belizean ambassador for foreign trade, Adalbert Tucker. Despite speaking on behalf of a right-wing government, in his words,

It is to give encouragement to Venezuela to continue the good work it is doing for democracy, for progress, development for the people of Latin America and the Caribbean…. President Chavez and Venezuela embraced all of us as part of the family. And that Bolivarian Revolution is what we need to become human beings in the 21st century. He shared wealth, ideas and he also encouraged us to share back with them what we can share. (Amandala 2013)

It provides evidence of the common values shared within the loyalty-based clientelistic network, just as our theory claims. It also shows that these values did not depend on the political orientation of the governments in charge, but only on the membership on these networks. And this support has been durable, as as demonstrated by votes at OAS and the election to the United Nations Human Rights Council. Therefore, we consider this qualitative evidence to support the claims and findings of this article.

Conclusions

Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela has adopted an increasingly radical foreign policy in international fora over the years and perpetuated it under Nicolás Maduro’s rule. For the purposes of this article,Chávez’s foreign policy can be split into two main components: the contestation of US hegemony in the world and an agenda related to reducing inequalities and asymmetries across the globe, reinforcing peoples’ self-determination to decide how to pursue their own destinies. As our empirical analysis shows, two fundamental mechanisms explain political support for this agenda: ideological convergences and clientelistic practices. While the former was partly covered by authors such as Amorim Neto and Malamud (Reference Amorim Neto and Malamud2015), Potrafke (Reference Potrafke2009), and Bailey et al. (Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017), the latter consists of this work’s potential original contribution.

We claimed that international clientelism is a mechanism much broader and deeper than mere vote-buying practices. Over 15 years or so, Venezuela not only provided money to its partners in exchange for political support but also created a solid and durable network based on dependency ties of vulnerable Central American and Caribbean countries, providing them with other services in kind, such as subsidized oil, refineries, airports, and housing. Qualitative evidence, and especially statistical findings, support this claim, showing that membership in PetroCaribe produced increasing similarities in voting at the UNGA between its members and Venezuela, and movement away from the US voting pattern. These convergences mostly relate to human rights, colonialism, and matters related to the Palestinian conflict, being noticed primarily in resolutions whose subjects are considered important by the US Department of State.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting materials may be found with the online version of this article at the publisher’s website: Appendix. For replication data, see the author’s file on the Harvard Dataverse website: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/laps