In 2006 Michelle Bachelet, Chile’s only female president, was elected to a strong presidency on a platform to reduce inequality, including gender inequality, and a relatively ambitious program of positive gender change. However, the Bachelet government’s capacity to effect policy change through the creation of new formal rules was limited, and as a result, despite successes in some areas, did not achieve all it had intended. How can executive branches like Bachelet’s achieve positive gender change (namely, the modification of rules and practices in ways that advance gender equality) in such constrained circumstances, where new rules are difficult to create? This article compares efforts in three policy areas—health, pensions, and childcare— that were central to Bachelet’s first presidency to explore why positive gender change could happen in some policy areas, most notably in the public provision of childcare, but was more difficult to achieve in others, particularly health.

Our comparative analysis of the Bachelet government’s efforts to achieve change in these policy areas advances our understanding of positive gender change in three ways. First, examining policy areas that were central pillars of Bachelet’s first presidency from a gender perspective fills important gaps in the gendered analysis of Bachelet’s administration, as well as gender policy change in Chile and Latin America more broadly (Franceschet Reference Franceschet2006; Stevenson Reference Stevenson2012; Thomas Reference Thomas2016; Haas Reference Haas2010). To date, explicit gender equality policies, like domestic violence under the auspices of SERNAM, the women’s policy agency, have attracted the most scholarly attention. However, efforts to integrate gender concerns into broader, often class-based reform endeavors, notably in social protection, were also significant. The creation of a comprehensive social protection system was the bedrock of Bachelet’s first program (Bachelet Reference Bachelet2005; Valdés Reference Valdés2009). Reforms in health, pensions, and childcare were part of a longer-term strategy aimed at (re)building the state, (re)establishing solidarity, and strengthening the social rights of citizenship (Pribble Reference Pribble2014).

Second, our analysis adds a new dimension to the burgeoning gender literature on executives by examining how critical gender actors in the executive, understood as a gendered institution, can achieve positive gender change in public policy.1 Until recently, most gender scholars examining female-headed executives have concentrated on the leaders’ paths to office, parity cabinets, and only explicit doctrinal or status-based gender equality policies, such as reproductive rights and gender-based violence (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013, Reference Jalalzai2016; Montecinos Reference Montecinos2017; Schwindt-Bayer and Reyes- Housholder 2017; Reyes-Housholder and Thomas Reference Reyes-Housholder, Thomas and Schwindt-Bayer2018). We go beyond this approach to look at outcomes in more implicitly gendered executive policy priorities, as well as critical gender actors in the executive beyond the president herself.

Third, by analyzing important but underresearched forms of institutional change, we contribute to a feminist institutionalism (FI) that analyzes the gendered institutional dynamics, power, and resistance that other forms of institutionalism ignore. We concur with Streeck and Thelen (2005, 12) that public policy change is a form of institutional change because it involves “rules that assign normatively backed rights and responsibilities to actors” and provides for third party enforcement. The smaller and often more incremental forms of positive gender change that take place in constrained circumstances when creating new rules are difficult; they remain underestimated and underresearched by feminists, who frequently focus on the creation of new institutions, such as the establishment of women’s policy agencies in the bureaucracy.

We start from the assumption that positive gender change in institutional arrangements has particular characteristics that distinguishes it from other forms of institutional change. Gender equality actors (predominantly, but not only, women, who are often feminists) face gendered institutional structures and resistance from opponents that other groups of actors do not (Krook and Mackay 2011). For example, these can be inbuilt in the masculinized formal institutional structures that act to exclude or disempower women, or can manifest themselves in male-dominated informal norms and practices, like exclusionary “old boy” networks and forms of gender-based harassment (Chappell and Waylen Reference Chappell and Waylen2013). Positive gender change often invokes forms of resistance rarely seen for other polices and institutions. Most notably, for example, doctrinal gender equality issues, such as reproductive rights, like abortion, often face fearsome opposition from unlikely alliances of opponents, who can nonetheless unite in their opposition to gender equality issues (Htun and Weldon 2018). Existing institutionalist frameworks cannot capture these gendered dynamics, as they do not look at power, resistance, and institutions through a gender lens (Mackay et al. Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010).

Method and Case Selection

Opening the black box of an executive requires in-depth qualitative research to reveal usually hidden processes. We adopt a small-n research design, comparing three policy areas chosen because of their centrality to the agenda of Bachelet’s first presidency and their huge implications for positive gender change. Eliminating implicit gender biases in policies like health and pensions, which are often nominally gender-neutral but negatively and disproportionately affect women, is a centrally important way gender-positive change can occur in the executive.2

Extending Htun and Weldon’s approach, as suggested in their recent book (2018, 234–35), we look at key reforms in three policy areas—health, pensions, and childcare—that promote class-based gender equality issues (rather than doctrinal or status-based ones) with huge implications for gender equality by providing more equal access to resources for women of different social classes. Reform in each policy area required state action to enact and faced varying degrees of resistance from market institutions, depending on how far the issue threatened vested capitalist interests or, conversely, might have the potential to strengthen the market economy.

For each policy area, we focus on three central aspects: key actors (including opponents and critical gender actors), change mechanisms (creating new rules, subverting or converting existing rules), and policy outcomes. In each area, the administration confronted a complex and variegated set of vested interests, institutional resistances, and ideological opposition. Although important progress resulted from the strategic navigation of issue-specific opportunities and constraints, it also entailed compromises in the extent and ways that gender inequalities could and would be addressed. By isolating key actors (both supporters and opponents), change mechanisms (e.g., legislation, executive decree, or ministerial guideline), and policy outputs for each of our three cases, we demonstrate the differential possibilities and constraints for positive gender change in different policy areas in a context in which the creation of new rules was very difficult.

We use theory-guided process tracing—a form of comparative historical analysis that uses “case-based analyses of configurations and historical process”—to identify the interactions over multiple sites of social activity that contribute to positive gender change (Hacker et al Reference Hacker, Paul, Thelen and Mahoney2015, 182). To uncover these processes, we collected data from more than 50 semistructured interviews, with informants including critical gender actors and others centrally involved in the three reform processes in different spaces and capacities: the executive, legislature, bureaucracy (including former ministers, policy advisers, and civil servants), political think thanks, and civil society organizations. We also draw on media coverage, descriptive statistics (including household survey data), and official documents.

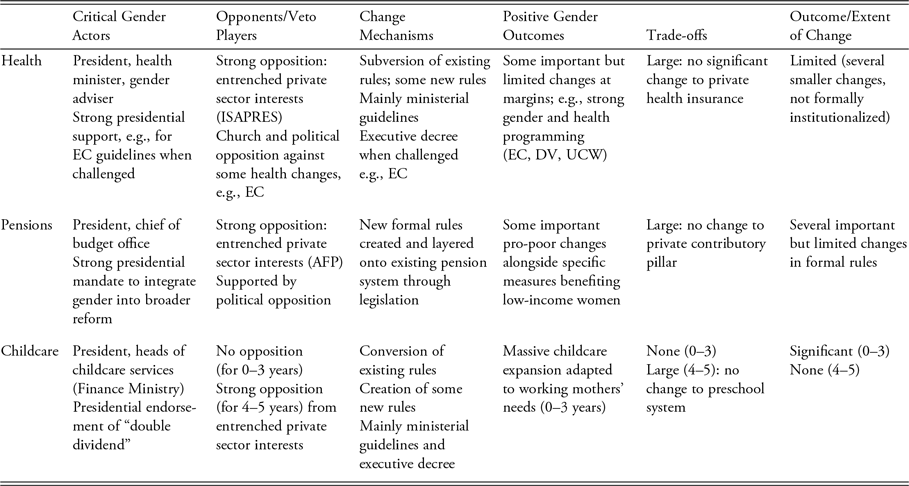

We find that despite the constraints, some reform—including positive gender change—was possible in each policy area (see table 1). But the change mechanisms and strategies that could be deployed by the relevant critical actors varied in response to the strength and character of the opposition they faced, and as a result, the trade-offs also varied. Change (through institutional conversion) could happen most easily in childcare and was most constrained in health (where subversion, or the “under the radar” manipulation of existing rules, was the predominant strategy). In pensions some limited, but significant, new elements were added onto the existing system (through layering). The differential possibilities for positive gender change were shaped by the particular interactions between actors, including critical gender actors and their opponents, the formal rules and informal norms and practices they engaged with, and the change mechanisms available in each area.

Table 1. Critical Gender Actors, Change Mechanisms, and Gender Policy Outcomes

AFP = Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones, DV = domestic violence, EC = emergency contraception, ISAPRES = Instituciones Previsionales de la Salud, UCW = unpaid care work

We structure the article as follows. To unpack how critical gender actors in the executive might achieve positive gender change in constrained circumstances, we outline a theoretical approach grounded in feminist institutionalism. We then examine the formal rules and informal norms and practices of the Chilean executive before considering the strategies that Bachelet and other critical gender actors could deploy to achieve positive gender change in each policy area.

A Feminist Institutionalist Framework for Analyzing the Executive

Feminist institutionalism (FI) provides us with the starting point to understand how executives as gendered institutions influence critical gender actors trying to introduce positive gender change in constrained circumstances (Mackay et al. Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010; Krook and Mackay 2011). Building on new institutionalism, FI sees institutions as gendered rules, norms, and processes in both formal and informal guises and examines how these shape actors’ strategies and preferences (Chappell and Waylen Reference Chappell and Waylen2013). The formal “rules of the game” and their enforcement are crucial, but the informal aspects of institutions—often less visible or taken for granted by actors inside and outside institutions—are also central. The interaction between formal and informal institutions, both the capacity for preexisting or new informal institutions to subvert and compete with formal institutions and also their potentially complementary, completing, and adaptive roles, is crucial (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004; Tsai Reference Tsai2006; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2010).

Our first task is therefore to analyze the Chilean executive in terms of the rules, both formal and informal, that Bachelet and other critical gender actors worked with and were also attempting to change in her first term. This requires an analysis of the broader structures of Chilean politics, as well as specific institutional processes in the executive, including cabinet and public service appointments. Our second task is to analyze the critical gender actors who promoted change and their opponents, including veto players, who blocked positive gender change. How did critical gender actors (male and female, including self-avowed feminists) operate within the institutional constraints in the executive and beyond? What strategies and alliances did they deploy?

Gender scholars have already shown that formal and informal networks, linking institutional insiders in the government, legislature, and bureaucracy with critical gender actors in civil society, NGOs, and feminist movements, can be crucial (Haas Reference Haas2010; Vargas and Wieringa Reference Vargas and Wieringa1998). But few have explored the gendered internal dynamics, informal networks, and alliances within the executive, those not just with the president but also between different ministers and bureaucrats and across different ministries, and how these can facilitate change. It is also crucial to examine exactly how opponents, vested interests, and veto players use formal and informal institutions to resist and block change and reform (Capoccia Reference Capoccia2016).

Furthermore, we need to look at the change mechanisms available to critical gender actors in the Chilean executive and their strategies to skirt institutional constraints and seize institutional opportunities. Since institutions like the executive branch are products of gendered power struggles and contestation, change is possible and can come from within. Actors’ challenges and changes to rules, norms, and practices can play a central part in bringing that change about (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010; Capoccia Reference Capoccia2016).

In an FI framework, positive gender change can take different forms, but primarily either the creation of new formal rules and institutions, which are sometimes layered on top of or alongside existing ones, or the reform of existing ones. Because critical gender actors—those women and men who pursue positive gender change either individually or collectively (Childs and Krook 2009)—often lack sufficient power and face considerable resistance, they are rarely able to create new institutions. Instead, they often work within existing institutions, utilizing or subverting existing rules or trying to “convert” institutions to support new ends, like greater gender equality. Because rules are often ambiguous, they can be the subject of political skirmishing and contestation (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010). Therefore, in contexts where the creation of new formal rules is impossible (e.g., because of resistance or opposition from veto players), actors, including critical gender actors, can sometimes exploit any slack and leeway in existing rules and their implementation—finding soft spots in the gaps or ignoring, reinterpreting, or breaking those rules (Streeck and Thelen 2005).

Where the rules include sufficient discretion and resistance and veto possibilities are low, existing institutions can be converted to new purposes (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010). However, when resistance and veto possibilities are high and existing rules offer little discretion, critical actors (often outsiders)—termed subversives by Mahoney and Thelen (Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010, 28)—often use more “under the radar” methods to manipulate and subvert existing rules. Actors also try either to subvert or convert existing institutions using political venues other than the legislature, like the courts and the bureaucracy (Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Paul, Thelen and Mahoney2015).

Understanding positive gender change in the executive requires understanding actors’ rule making, breaking, and manipulation, as well as informal practices in institutions that can either promote or block change, aspects that have not yet been studied sufficiently by gender scholars (Waylen 2017). We must interrogate how critical gender actors in the executive, like Bachelet and her allies, used the different institutional change mechanisms at their disposal at a time when they did not hold sufficient power on their own to displace old institutions and when they faced considerable resistance. We must explore how far critical gender actors in Bachelet’s executive could create new rules or break, bend, and manipulate existing rules. How did reform strategies and change mechanisms—whether the creation of new rules or the subversion or conversion of existing rules—vary between the different reform areas? What resistance did they face, and where?

Formal and Informal Rules, Norms, and Practices in the Chilean Presidency

As the most important critical gender actor in the executive, Bachelet became chief executive in a polity long recognized as having a strong, agenda-setting presidency with extensive formal powers, particularly in policymaking and budget setting (Siavelis Reference Siavelis2000). Chilean presidents use tools such as urgencies and presidential vetoes to influence the legislative process and implement policy change. They have sometimes used decrees, bypassing the legislature, to take their policy priorities forward. Legislators, in turn, have had relatively little power to get initiatives passed without executive support or to introduce bills that involve spending or affect the budget.

Historically, presidents also had significant individual powers (Bonvecchi and Scartascini Reference Bonvecchi and Scartascini2014). Presidents could unilaterally and strategically appoint at all levels of the state—bureaucrats as well as ministers—placing friends and political allies in key policy areas (Martínez-Gallardo Reference Martínez-Gallardo, Scartascini, Stein and Tommasi2010). Presidents could also determine how their cabinets functioned, with important business often taking place through bilateral relationships between ministers and them, rather than in thematic interministerial committees or the full cabinet. But ministers, too, could have important policymaking powers, evoking ministerial guidelines; and some ministers, notably the finance minister, and the key coordinating ministers, particularly the powerful secretary to the president (SEGPRES) and the secretary to the government, played a central role in setting agendas and blocking measures (Martínez-Gallardo Reference Martínez-Gallardo, Scartascini, Stein and Tommasi2010).

At the same time, an array of formal and informal political institutions—many an ongoing legacy of military dictatorship (1973–89) and the transition to democracy—limited the seemingly strong agenda-setting presidency Bachelet was elected to (Siavelis Reference Siavelis2000; Aninat et al. Reference Aninat, Londregan, Navia, Vial, Stein and Tommasi2008). In 2006, a binomial political system, created by the military’s 1980 Constitution, still enhanced the power of the right in the leg- islature, encouraging centrism and the formation of broad electoral coalitions (Sehnbruch and Siavelis 2013). Despite some amendment, the constitution gave considerable power to veto players like the Constitutional Tribunal, and legislative “supermajorities” were necessary for some reforms. These formal constraints produced several adaptive informal institutions to maintain coalitional cohesiveness and facilitate broad-based agreements (Siavelis Reference Siavelis, Helmke and Levitsky2006). This included government by acuerdos (agreements) and the cuoteo, an adaptive informal mechanism to distribute candidacies and executive posts between parties within the Concertación, the governing center-left coalition.

Despite their seemingly extensive formal powers, Chilean presidents have often achieved their goals through negotiation—cajoling, convincing, and accommodating the opposition—rather than by using their full constitutional capabilities, particularly in controversial areas where legislative approval was necessary but unlikely (Siavelis Reference Siavelis, Morgenstern and Nacif2002, 109). And presidents developed informal mechanisms like the Segundo piso (the second floor of the presidential palace, housing powerful presidential advisers) to circumvent constraining formal and informal mechanisms like the cuoteo.

By 2005, the Concertación coalition had won every presidential election since the transition, and was dominated by four main parties. The Christian Democrats (CDs) and varieties of democratic socialists were key players with different positions on social and economic policy. The “market-friendly sector,” dominant since 1990, supported the free market model introduced by the military regime (Pribble Reference Pribble2014). Instead of challenging dominant vested interests, the Concertación mitigated the negative effects of privatized state assets and welfare provision through greater social spending rather than fundamental reform. As the first female Concertación presidential candidate, Michelle Bachelet claimed to represent “continuity and change,” promising a new, more inclusive politics, with a different leadership style, new faces, and gender parity in the executive, when the Concertación was seen as increasingly tired and in need of a new image (Borzutzky and Weeks 2010).

Bachelet’s initial path to office was not unusual for a female president (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2016). A longtime militant of the Socialist Party, she was both “in and out” of the party—not an insider but also not an outsider (Fernández 2013). She had never held senior party or elected office or been part of male-dominated leadership. Trained as a doctor, she became health minister when Ricardo Lagos, the previous Socialist president (2000–2006), wanted more women in his cabinet, then rose to prominence as the first female defense minister (Muñoz 2011). It was her support in the opinion polls (and particularly from low-income women), rather than party elites, that enabled Bachelet to become the Concertación candidate (Ríos Tobar 2009). As a moderate socialist, she emphasized increasing equality, including gender equality, advocating greater social spending to create a more comprehensive social protection system. She was not widely considered a feminist—in the sense of having a feminist movement background—but rather a woman with a developed gender consciousness, and gender concerns figured prominently in her electoral program (Ríos Tobar 2009).

Bachelet, too, had to contend with complex formal and informal constraints. To date, gender scholars have focused on their negative implications for the formation of parity cabinets in her first presidency (Franceschet and Thomas Reference Franceschet and Thomas2015). Through the cuoteo, the elite and male-dominated parties could exert a great deal of control. Party bosses would suggest names for “their” cabinet posts, but few women were considered to have the requisite elite party background (PNUD 2010). Bachelet initially ignored some of the choices of party leaders. For example, she brought previously excluded secular socialists into the cabinet. Three of the four socialists were women—Paulina Veloso (SEGPRES), Clarisa Hardy (Planning), and Soledad Barría (Health)—the latter renowned among feminists for her history of campaigning for gender equality. But Bachelet’s attempt to renew the executive exacerbated her uneasy relationship with the coalition’s male-dominated party elites.

These constraints made balancing the demands of the cuoteo, parity, and new faces hard in the first two years of Bachelet’s presidency. It was beset with crises— including the rise of mass protests over education and an ill-fated reform of Santiago’s transport system—which considerably weakened it. As Bachelet’s power in regard to the party elites declined, several prominent women cabinet ministers, including the defense minister, Vivianne Blanlot, and Veloso, the influential SEGPRES, were replaced by longtime male party heavyweights (because the balance of the parties had to remain the same). Therefore, despite her expressed intentions, Bachelet could not circumvent the informal mechanisms that had determined previous cabinet choice (Waylen Reference Waylen2016a).

The first Bachelet government continued other trends seen in previous Concertacion administrations (Borzutzky and Weeks 2010). Technocrats, many of them U.S.-trained economists, played a dominant role in government. The Finance Ministry exemplified this, and Finance Minister Andrés Velasco, an independent and relatively orthodox U.S.-trained economist, was central to Bachelet’s first administration. Reform endeavors, including those aimed at advancing gender equality, were unlikely to succeed if the Finance Ministry opposed them. Furthermore, despite initial promises that there would be no Segundo piso, Bachelet, to sidestep her divided political team, cabinet, and political parties, created her own segundo piso of close friends and advisers, dominated by Velasco (Siavelis and Sehnbruch Reference Siavelis and Sehnbruch2009). Therefore, because Bachelet had to contend with the same formal and informal rules and norms as her predecessors, she also resorted to some of the same practices.

Critical Actors, Change Mechanisms, and Gendered Policy Reform, 2006–2010

Although the formal and informal rules, norms, and practices placed important constraints on critical gender actors, legislative and policymaking activity around gender equality increased significantly during Bachelet’s first term (Blofield and Haas 2013). However, the posttransition norm of top-down technocratic government by agreement and the informal norm of negotiating policy change with the opposition prevented controversial proposals from appearing on the agenda. Chile remained a conservative society, in which the Catholic Church maintained considerable veto power over doctrinal issues like divorce, contraception, and abortion.

The previous three Concertación governments had been unwilling to push controversial measures in the face of right-wing and religious opposition (Blofield Reference Blofield2001; Haas and Blofield 2013). As a result, key feminist demands (e.g., around reproductive rights) had fallen off the agenda. Despite the creation of SERNAM during the transition, women’s organizations had not had significant input into policymaking, and women’s political representation remained low. A lack of ambition to reassess the economic and social model inherited from the dictatorship—assigning a predominant role to market-based social provision, such as in health and pensions— also had important gender implications.

Aware of the formal and informal constraints that the political system imposed on socially progressive policy agendas, Bachelet tried unsuccessfully to reform electoral rules, failing to shift the balance of power, which favored the right (Franceschet Reference Franceschet2010). Midway through her first mandate, the Concertación also lost its majority in Congress, so legislation became harder to pass without support from the opposition. Consequently, some measures were abandoned or enacted in different ways, while others were diluted or downgraded after negotiations with right-wing legislators. An equal pay act was rendered ineffectual after opposition from the right (Stevenson Reference Stevenson2012). Mechanisms other than the creation of new formal rules through legislation—ministerial and bureaucratic as well as presidential—were used to implement other measures. But even when Bachelet invoked special presidential powers like decrees to advance contested reforms, opponents used institutions like the Constitutional Tribunal to challenge them (as happened with emergency contraception).

Within the executive, Bachelet, as the most powerful critical gender actor, used some other mechanisms to incorporate gender concerns into policymaking, from problem definition through to policy adoption, resource allocation, and dissemination. She ensured that SERNAM was present during interministerial negotiations with important gender implications, such as the pension and childcare reforms. And despite not playing a leading role, SERNAM’s influence was greater than under previous administrations, if only because gender equity was known to be something the president supported (Andrade 2011; Hardy 2011; Reyes 2011). Bachelet utilized her strategic powers of recruitment and appointment to ensure that in important areas of her reform program, like health, pensions, and childcare, the key ministers and high-level officials shared her views on positive gender change. Many of these critical gender actors were longtime friends and members of her campaign team (dubbed Bachelemenas by the media), drawn from her personal constituency of elite feminists (Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2019).

Bachelet also raised the profile of gender issues in the executive both symbolically and substantively, reinterpreting existing rules and creating new ones. First, she used preexisting institutions, like the Council of Ministers for Equality of Opportunity, created under her predecessor, Ricardo Lagos, to further her gender equality agenda.3 By reinterpreting the council’s informal rules and norms of operation, she deliberately tried to enhance its significance. In contrast to her predecessors,

Bachelet personally attended council meetings and expected ministers to do the same. Thomas (Reference Thomas2016) reports that ministers who might have previously been late or absent gave it a higher priority once Bachelet questioned them at meetings. Second, she created new mechanisms to enhance progress on gender equality goals at the cabinet level: a team of gender advisers, coordinated by SERNAM, would monitor the progress of ministerial gender commitments and give a higher priority to the equality duty that in 2002 had been incorporated into the PMG (the public sector Management Improvement Program set up in 1998) (Matamala Reference Matamala, Burotto and Torres2010; PNUD 2010). Furthermore, Bachelet ensured that commitments were followed up and evaluated by the powerful SEGPRES.

The administration promoted several explicitly doctrinal and status-based gender equality policies, particularly around women’s physical integrity and reproductive choice (Valdés Reference Valdés2009). For example, responding to longstanding pressure from women’s organizations and SERNAM, Bachelet increased resources (primarily through SERNAM, which the administration could do relatively easily) to better protect women from domestic violence (Franceschet Reference Franceschet2010). Bachelet also occasionally utilized presidential instruments like urgencies to facilitate the swift approval of congressional initiatives, such as the bill designating femicide a crime, proposed by several male and female Concertación legislators (Haas Reference Haas2010; Stevenson Reference Stevenson2012).

With this background, we can now examine in more detail attempts to achieve gender reforms in the three policy areas of health, pensions, and childcare.

Health: Limited Change Through Subversion

A set of major health reforms had been enacted under the Lagos administration between 2002 and 2004, but it was implemented largely during Bachelet’s first presidency. Despite new formal rules, such as health guarantees and expanded access to treatment, the reform did not fundamentally alter the health care model imposed by the dictatorship, in which private sector interests played a key role. It was also predominantly gender-blind (Gideon Reference Gideon2012).4

During her short tenure as Lagos’s health minister, Bachelet had pushed for more progressive and gender-sensitive reforms to strengthen the state’s role in health financing and service provision. Together with María Soledad Barría, an avowed feminist and fellow party member whom she had known since adolescence, Bachelet initiated civil society consultations and created a ministerial advisory group on gender issues. But their efforts were unsuccessful. Lagos deliberately bypassed Bachelet in the health reform process, creating a parallel technical commission, headed by a close personal friend, which operated largely in isolation from the ministry and SERNAM, considering gender issues to be largely irrelevant (Lamadrid 2011; Sandoval 2011; Reyes 2011). After disagreeing with the government’s approach, Bachelet was removed as health minister in 2002, closing down the opportunities for women’s organizations to channel their claims to the executive

(OPS 2007).

Once president, Bachelet did not formally challenge the reform but tried to reinterpret or manipulate some aspects she disagreed with, boosting the notion of rights and emphasizing the role of the state more than the reform’s designers had intended (Barría 2011; Matamala 2011; Anonymous 2011a). She also ensured that new spaces opened for integrating gender into health policy. First, critical gender actors were appointed. Her longtime ally Barría, as health minister, significantly raised the profile of gender issues, facilitated by invaluable technical and political support from the ministry’s gender adviser, María Isabel Matamala, a longtime feminist activist. Bringing outsiders in, women’s health groups now had renewed access to health policy and programming processes. Second, the participation of women’s organizations in the planning and execution of these policies was facilitated by a new consultative body, the Consejo Consultivo de Género y Salud de las Mujeres—part of Bachelet’s broader attempts to create channels for citizen participation in decisionmaking (Gideon Reference Gideon2012).

As a result, important parts of the government’s responses to key issues of doctrine and status in women’s rights—including domestic violence and reproductive rights—were engineered and implemented from within the Health Ministry, with significant input from women’s organizations. Examples included free and confidential access to emergency contraception, the implementation of health staff training and pilot programs for the detection and treatment of victims of domestic violence at the primary care level, and efforts to measure unpaid care work and integrate its contribution into health accounting via satellite accounts (Matamala et

al. 2005).

Virtually all of these changes were made in ways that did not require formal legislative approval from a potentially hostile Congress. Instead, critical gender actors utilized the gaps and soft spots in existing rules, working “under the radar” with ministerial guidelines, decrees, and health programming initiatives to subvert gender biases in the health system. The provision of free emergency contraception in public health centers, which faced powerful opposition from the Catholic Church, prolife groups, conservative legislators, and Constitutional Tribunal judges, was the exception. It began as a ministerial guideline but had to pass through Congress, where it was challenged by a coalition of right-wing parliamentarians (Guzmán et al. Reference Guzmán2010). After a long political battle forcing Bachelet, a strong advocate of the initiative, to intervene with a presidential decree, the issue reached the Constitutional Tribunal, and free and confidential access to emergency contraception at the primary care level was finally established in law in early 2010 (Sepúlveda-Zelaya Reference Sepúlveda-Zelaya2016).

The struggle to get this provision approved highlights other major unaddressed issues in women’s health. As a concession to Christian Democrat coalition partners, abortion—even on therapeutic grounds—remained firmly off the agenda (Maira Reference Maira, Burotto and Torres2010). The veto power of religious doctrine and the consensus model sustaining the Concertación prevented farther-reaching changes. Not until the end of Bachelet’s second term did a limited, yet extremely controversial, reform pass.

A different set of vested interests prevented rule changes to the discriminatory practices of private health insurance companies, the Instituciones de Salud Previsional (ISAPREs), a legacy of the 1980s market reforms under military rule.5 In response to longstanding criticism by gender advocates, Bachelet had proposed to “eradicate discrimination against women of reproductive age committed by the ISAPREs” (Bachelet Reference Bachelet2005, 89). Although Lagos’s reforms effectively ended the commercialization of planes sin utero (health plans excluding childbirth and maternity care), they did not defy the individual, risk-based logic of private health insurance per se. Expected differences in risk profiles, such as pregnancy and birth, remained a justified form of price discrimination, so women of reproductive age continued to pay significantly higher premiums than men of the same age and, as a result, were less likely to be privately insured (Ewig and Palmucci Reference Ewig and Palmucci2012).

One way to taper gender inequalities in private health premiums without banning risk discrimination altogether would be to include all maternity care in the package of specially guaranteed health conditions created in 2004—the so-called Plan AUGE.6 Plan AUGE applied to both the publicly and privately insured and was set up to pool risks and resources among all ISAPRE affiliates for selected conditions under Inter-ISAPRE com. Plan AUGE also specified treatment protocols for conditions covered, and potentially could improve the quality of maternity care in both the public and the private system (e.g., by reducing the very high rates of caesarean sections by standardizing treatment protocols in ways that guaranteed women’s right to make informed choices). Aware of these possibilities, Health Minister Barria commissioned a study on the issue. Yet the inclusion of all maternity care among the AUGE conditions was eventually discarded as, according to an official of the Superintendent of Health, the implementation of such new treatment protocols in the public health system was vetoed as too costly by the Finance Ministry (Cid 2011). Here, the reluctance to confront private sector resistance, as well as the persistent commitment to fiscal restraint, limited positive gender change in health policy.

Overall, however, gender concerns were more integrated into health policy under Bachelet than they had been under the previous administration. The presence and commitment of Bachelet and other critical gender actors with “a vision, greater conviction and [who] were also in a place where they could do it” in key positions in the Health Ministry was crucial, according to a high-ranking health official (Muñoz 2011). These actors were further aided by the administration’s commitment to gender mainstreaming, which, according to Barría, helped to facilitate a diverse set of gender-equity policies (Barría 2011). However, even with a significant commitment to gender equality, the administration shied away from farther-reaching changes in formal rules that would have required legislative approval or a significant allocation of resources. It focused instead on smaller, “under the radar” changes in health planning and programming at the ministerial level. To effectuate these, critical gender actors tried to subvert gender bias in the health system by working through existing rules and routine processes and strengthening their engagement with women’s organizations. The downside of this subversion strategy, however, was that changes were only weakly institutionalized (emergency contraception being the exception), remaining dependent on the continued presence of critical gender actors. After Barría’s removal as health minister in 2008 in a cabinet reshuffle, for example, the dialogue with women’s organizations once again stalled.

Pensions: Significant but Limited Change Through Layering

While some changes in health policy could take place largely at the ministerial level, utilizing mechanisms like the introduction of new guidelines (followed by a presidential decree for emergency contraception), reform of the pension system created during the dictatorship was a flagship project requiring formal rule change through parliamentary legislation. Gender inequalities were particularly manifest in this area. In the mid-2000s, 62 percent of those aged 65 and over received a pension; yet this share was much lower among women (55 percent) than men (71 percent) (Mesa- Lago 2009). Women’s pensions were about one-third lower than men’s, even if they retired at the same age (Arenas et al. 2006).

The reasons for this were complex. The negative impact of women’s lower labor force participation, lower earnings, and more frequent employment interruptions and therefore lower contributions was compounded by the pension system’s rules. Individual capital accounts established a particularly tight link between lifetime contributions and pension entitlements. In addition, gender-differentiated mortality tables were used to calculate monthly benefits. Due to their greater expected longevity, women received lower monthly benefits than men, even if they accumulated the same level of contributions.

The original impetus for pension reform emerged within the bureaucracy in the early 2000s, when officials started collecting systematic evidence on the system’s shortcomings (Staab Reference Staab2017). This evidence not only gradually debunked claims by private pension funds, the Administradores de Fondos de Pensiones (AFPs), that the system was functioning well, but also highlighted gender inequality by making women’s pension status blatantly clear. According to a former high-ranking SERNAM official, “the baseline assessment was so obvious, it was so clear that those who were most disadvantaged were women that I believe this didn’t allow much of a discussion” (Andrade 2011). Before the 2005 presidential election campaign, state bureaucrats successfully lobbied Michelle Bachelet and Concertación party leaders to put pension reform onto the presidential agenda.

In contrast to the Health Ministry, the male ministers tasked with taking the reform forward—a party leader in Labor and a technocrat in Finance—were not particularly sympathetic to gender equality concerns.7 However, within the Finance Ministry, pension reform was firmly located in the Budget Office, headed by Socialist and gender equality sympathizer Alberto Arenas, who had first encountered Bachelet when she was health minister in 2000 (and subsequently became finance minister at the start of her second term in 2014) (Carcamo 2013). Arenas’s exposure to gender issues dated back to the mid-1990s, during his Ph.D. studies at the University of Pittsburgh, when he co-authored a paper on the gender effects of pension privatization with a well-known gender scholar of Chilean origin (Arenas and Montecinos Reference Arenas and Montecinos1999). Therefore Arenas, described as the “ideologue of the reform,” was not only an important male critical gender actor for engendering pension reform but an actor at the center of political and fiscal power.

Bachelet used additional mechanisms to ensure that women’s pension status was of central concern to the reforms, from initial problem definition to policy adoption and dissemination. The advisory council established to provide reform recommendations was explicitly tasked with finding ways to eliminate gender discrimination; women’s organizations were invited to participate in public hearings; and SERNAM formed part of the Interministerial Committee charged with translating reform recommendations into the legislative proposals presented to Congress in December 2006. According to a SERNAM official, “the president’s will was clear on this [issue], and therefore the rest of the ministers understood that it was part of the rules of the game” (Andrade 2011).

The result was a significantly strengthened pillar of noncontributory, state- sponsored benefits, targeted at 60 percent of low-income households. Given gendered patterns of poverty and employment, women would be overrepresented as recipients of these newly created benefits.8 The reform also introduced several entitlements to improve women’s pensions: a flat-rate maternity grant (bono por hijo) added to mothers’ pension accounts; changes to disability and survivor’s insurance, likely to raise women’s pension levels; and pension-splitting on divorce or annulment—a provision for which SERNAM had “fought tooth and nail” following its exclusion from the 2003 divorce law (Iriarte 2011).9

Yet key features of the pension system remained essentially unmodified—most notably, the individual capital account system created under military rule in 1981. Benefit formulas and gender-differentiated actuarial tables continued to mitigate more gender-egalitarian pension outcomes. The limits to gender-egalitarian policy change were a result of wider coalition politics. Concertación party elites agreed that it was neither feasible nor particularly desirable to make major changes to the individual capital account system. Policy feedback from pension privatization largely explains this reluctance (Ewig and Kay Reference Ewig and Kay2011). Reformers in the executive believed that it was too economically risky to alter the private pension system’s structure because of its importance to Chile’s financial system and integration into global capital markets. Reformers also faced important political pressures from business interests, including the AFPs, which profited from the administration of individual accounts, and others benefiting from pension fund investments.

The decision to leave the individual capital account system intact had important gender implications (Yáñez Reference Yáñez2010). In particular, it precluded the modification of gender-differentiated actuarial tables—a particularly discriminatory feature of the pension system—despite the strong presidential mandate to eliminate gender discrimination. Although femocrats, SERNAM, and women’s organizations repeatedly raised the issue, their efforts were of little avail (Iriarte 2011). Compensatory measures—like the maternity grant and the redistribution of funds from disability and survivor’s insurance—would improve women’s pension outcomes but would not redress more systemic gender biases. The maternity grant, although an important recognition of unpaid care, was fraught with tensions. Directly targeting mothers explicitly reinforced their role as caregivers, missing the opportunity to send signals and set incentives to transform traditional gender roles. For many women, this low, flat-rate benefit would not compensate for the opportunity costs of interrupting paid employment for childrearing.

Overall, because of top-down executive commitment to gender equality, gender concerns were layered on top of existing institutions in the mainstream pension reform. Bachelet herself sent a clear message that the reform had to specifically address women’s old age security and eliminate gender discrimination in the pension system. This goal was not fully achieved, due to the power of vested business interests and the need to tailor broad-based agreements with bipartisan support in the legislature. As a result, more radical reform, recasting the individual capital account system, was off the agenda until Bachelet’s second term. But positive gender change took place nevertheless, even if it did not directly undermine key aspects of the existing pension system. In layering a new set of benefits that implicitly or explicitly supported women alongside existing pension schemes, Bachelet relied heavily on the technical and political expertise of other critical gender actors in the executive, in particular her budget director, Alberto Arenas.

Childcare: Significant Change Through Conversion

The expansion of childcare services, a class-based gender equality issue, was an important pillar of Bachelet’s social protection agenda. In Chile Crece Contigo (Chile Grows with You), an integrated child protection strategy launched in 2006, the government committed to greatly expand public crèches (0–1 years) and kindergartens (2–3 years), particularly for children from low-income families. By 2009, the program was formally institutionalized in law, giving children from low-income families the right to a full-time crèche and kindergarten place if their mothers were working, looking for work, or studying; or a part-time kindergarten place without preconditions. Childcare facilities were rolled out rapidly: the number of public crèches increased from about seven hundred in 2006 to more than four thousand in 2009 (Mideplan 2010). The coverage for children aged 0–2 years increased from 3.2 percent in 2003 to 10.1 percent in 2011, while coverage for 2–4-year-olds increased from 19.8 to 41.5 percent over the same period.10

Similar to the pension reform, ideas about childcare service expansion had emerged from the bureaucracy. During the second half of the Lagos government, officials in the Finance and Planning Ministries coalesced around a pro-(female)- employment/anti-(child)-poverty agenda. Ideas of social investment strongly underpinned the support for childcare expansion as an economically sound policy option that would increase children’s human capital, as well as their mothers’ employability (Staab Reference Staab2017). According to key actors, Bachelet and her campaign advisers also felt that the childcare agenda resonated with Bachelet’s profile—as a doctor and pediatrician concerned about child development and closer to people’s needs than preceding administrations.

Strong executive support—including the Finance Ministry, which considered it a way of raising women’s low economic participation rates—significantly contributed to making childcare a policy priority (Farias 2011; Hardy 2011; Anonymous 2011b). Seen as electorally attractive, economically sound, and politically feasible, it promised quick and politically uncontested progress, as there were few vested interests, and service expansion for 0–3-year-olds did not need legislative approval. The allocation of additional resources reflected executive commitment: not only did the childcare budget increase significantly between 2006 and 2009, but actual spending exceeded the resources initially allocated in the budget law (using discretionary executive funds to meet the ambitious targets). As a result, the childcare budget quadrupled between 2006 and 2010, after stagnating in the early

2000s.11

The Finance Ministry’s instrumental interest in raising Chile’s comparatively low female labor force participation rates meant that service expansion had to benefit working mothers, particularly regarding opening hours. Yet full-day and extended schedules were by no means an obvious or potentially uncontested policy choice, even in the context of Chile’s historically maternalist welfare state. During the 1990s and early 2000s, SERNAM had faced significant resistance—both ideological and corporatist—in its efforts to extend schedules in public childcare institutions (Andrade 2011; Reyes 2011). Childcare workers had resisted meeting the needs of flexible employment—including excessively long and flexible working hours—through the “institutionalization” of children for extended periods, which might reduce the quality of care (Ortiz 2011; Garate 2011; Andrade 2011). Because extra hours were to be covered by existing staff in a shift system, the policy had been seen as a degradation of working conditions. Gradually, however, extended schedules had been introduced in the limited existing public daycare network through specific initiatives targeting “vulnerable groups,” such as SERNAM’s female head of household and seasonal agricultural worker programs.

As “this battle had already been won” (Andrade 2011), the Bachelet administration could now build on SERNAM’s groundwork, converting existing public institutions. The move was further cemented with the appointment of key high-level officials—like Estela Ortiz, one of Bachelet’s closest longtime friends and allies—to head up service expansion. In contrast to their predecessors, these officials firmly supported the female employment agenda and became critical actors in the implementation of positive gender change.12 As a budget official commented, “sometimes there were formal meetings in La Moneda [the presidential palace] and you discussed things and you knew that afterwards the president could be having dinner at her house with the director of JUNJI and they would come to an agreement…. This was very different from discussion with minister X from any other area who did not have this relationship” (Anonymous 2011a). As a result, significant progress was made in institutional care for 0–3-year-olds: coverage increased significantly, class inequalities in access narrowed, and virtually all new services offered full-day schedules.13

At the same time, the executive shied away from reforming other aspects of childcare policy. Preschool services for 4–5-year-olds escaped reform completely. Here, service provision remained out of sync with the needs of working mothers, running mainly half-day programs with long school holidays. As in the private pension system, important economic and political barriers to preschool reform existed. During the early 2000s, preschool services had been locked into the institutional structure of the broader education system, where private sector interests dominated.14

In addition, constitutional provisions required any modification in this area to be made via legislative debate and approval (including quorum laws). For both reasons, the executive focused on the less contentious expansion of daycare services for 0–3-year-olds. The advisory council that developed the child protection strategy had initially produced recommendations for children from 0 to 10 years old. But the government reduced this to 0 to 4 years old. A Mideplan official involved in discussions suggested that it was to avoid major ideological battles over public and private provision in the broader educational system (Farias 2011).

Overall, childcare service expansion for 0–3-year-olds is a compelling contrast to health and pensions. Here, critical actors—Bachelet and the heads of services— supported by the Finance Ministry, facing relatively few institutional constraints, seized the opportunity to expand and convert existing public provisions. This was possible for a number of reasons. Business interests were weakly entrenched in the care of younger children, and the expansion of public services in this area did not require legislative approval beyond the annual budget allocations—where the executive held far-reaching prerogatives. Executive power over agenda setting and policy implementation could take the expansion forward in the absence of private sector resistance that had proved so critical in health and pensions, but could not extend provision for older children.

Conclusions

In contexts in which resistance is fierce and the capacity to create new rules is constrained, critical gender actors can achieve some positive gender change by using other mechanisms. This in-depth analysis of configurations and historical processes in three policy areas—focusing on critical actors (both supporters and opponents of positive gender change), formal institutional rules, and informal norms and practices that influenced their relative leverage—has demonstrated how the often underestimated subversion or conversion of existing rules can be effective strategies for some positive, if incremental, gender change. Therefore, although even powerful critical gender actors cannot always create new rules, they can sometimes exercise unexpected power through alliances and strategies that bypass the need for new rules, despite the constraining effect of opposition resistance and veto power. But to explain differing outcomes, analyses must uncover the range of change mechanisms in all the different venues available to critical actors (see table 1).

Enhancing our understanding of how the executive operates as a gendered institution, we have seen how critical actors in the executive could integrate gender equality concerns into reforms already on the agenda in ways that were highly unlikely without their presence. But these critical gender actors had to navigate the formal and informal constraints within their specific institutional contexts. Bachelet, as a chief executive with considerable formal and informal powers, was the most important critical gender actor in the executive. But in each policy area, other critical gender actors—each an appointee and ally of Bachelet—played a key role in ensuring that positive gender change was part of policymaking efforts. Many of them were Bachelet’s longtime friends, linked together in informal networks. However, key allies could also be vulnerable—the feminist health minister’s removal demonstrates the limits of Bachelet’s powers of appointment—with implications for further positive gender change.

The varying outcomes in our three policy areas also demonstrate the differing ways that powerful resistance, whether religious, ideological, or economic, affects outcomes. Despite a relatively strong presidency, positive gender change in policymaking was constrained by opposition that critical gender actors faced inside and outside the state. Opposition actors came together in different forms and used different strategies, depending on the policy area. In the case of health and pensions— two areas with significant implicit gender biases—the political constraints that enhanced the power of the right were compounded by the considerable veto power of entrenched private sector players over measures seen to damage their interests— a consequence of the inherited neoliberal economic model. These private sector interests were less important in childcare, which enabled more emphasis on public sector provision and, arguably, greater success at reform (albeit in the facilitating context of a historically maternalist state). Contested doctrinal issues, such as emergency contraception in the health sector, provoked additional opposition from the Catholic Church and right-wing legislators, who could use judicial institutions like the Constitutional Tribunal to advance their cause.

Given these formal and informal constraints, to achieve positive gender change, critical gender actors had both to create new rules and to work within the existing rules, exploiting any slack and soft spots. In only in one area—pensions—were new formal rules created in the legislature. However, this achievement necessitated important trade-offs with opponents and the layering of limited new formal rules onto existing institutions.

In both health and childcare provision, Bachelet and her allies could use existing powers to circumvent opposition and implement change. In health, greater resistance from vested interests and little capacity to create new rules prevented much reform, except by subversion and manipulation of existing rules at the margins. In contrast, because extending childcare and instrumental support drew little opposition from the Finance Ministry, given its potential to strengthen the economy, existing institutions could be converted to new purposes without recourse to formal rule change. Reform thus occurred most easily in childcare and was most constrained in health.

Overall, Bachelet’s first administration stopped short of more radical gender reforms that would have fundamentally challenged vested interests, fiscal rectitude, and the neoliberal social and economic model inherited from the dictatorship, and would have required different change mechanisms.

In contrast, during her second term (2014–18), elected with a majority in both houses, Bachelet did attempt a more far-reaching and ambitious program to reform education, taxation, and the constitution (as well as pensions) by creating new rules in the legislature. Resistance from a range of opponents was intense. Mired in scandal and soon extremely unpopular, many of the executive’s reform efforts floundered or were much diluted. And only electoral reform that included gender quotas, and the legalization of abortion in three limited cases (but with fears about implementation under the following Piñera government) brought notable positive gender change (Reyes-Housholder and Thomas Reference Reyes-Housholder, Thomas and Schwindt-Bayer2018).

In conclusion, gender scholars should explore further the extent to which critical gender actors in other contexts can achieve positive gender change through the subversion or conversion of existing rules, even in the face of powerful resistance, and how this can occur in venues other than the legislature. Although the results of these small and sometimes incremental changes may appear unimpressive, as no immediate fundamental change occurs, this is no reason to dismiss them, as they can be important in contexts in which the creation of new institutions is unlikely and equality actors face particular gender-based obstacles. These underestimated and frequently “hidden” forms of positive gender change can lay the groundwork for further reform, and, in a context of retrenchment and backlash, deserve more attention from gender scholars.

Interviews

All author interviews took place in Santiago.

Andrade, Carmen. 2011. Former Vice Minister, SERNAM (2006–10). August 2. Anonymous. 2011a. Former budget official, Santiago. October 20.

Anonymous. 2011b. Former health official. October 5.

Barría, Soledad. 2011. Former National Health Minister (2006–8). October 20.

Carcamo, Isabel. 2013. Feminist activist. August 23.

Cid, Camilo. 2011. Academic; former official at Superintendent of Health. September 14.

Farias, Ana María. 2011. Former Ministry of Planning official. August 4.

Fernández, María de los Angeles. 2013. Political analyst. July 30.

Garate, Nuri. 2011. Technical Director, JUNJI. August 26.

Hardy, Clarissa. 2011. Former Minister of Planning (2006–8). August 22.

Iriarte, Claudia. 2011. Former SERNAM official. October 3.

Lamadrid, Silvia. 2011. Academic; former SERNAM official. August 2.

Matamala, Marisa. 2011. Health activist; gender adviser in the Ministry of Health (2006–10). October 18.

Muñoz, Fernando. 2011. Academic; former official in the Ministry of Health. September 28. Ortiz, Estela. 2011. Former Vice President, JUNJI (2006–10). October 21.

Reyes, Andrea. 2011. Head of Regional and Intersectoral Coordination, SERNAM. December 7.

Sandoval, Hernán. 2011. Academic; former head, Commission on Health Reform (2000– 2006). October 26.