The establishment of direction and control of defense policymaking is one of the significant steps civilians must take to fully democratize civil-military relations (Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017; Serra Reference Serra2010). To get there, some crucial preconditions must be met: the creation of a ministry of defense, led by a civilian with a permanent civilian staff (Martínez Reference Martínez2014); an institutional design of defense organization that lowers the military’s vertical authority along the chain of command (Pion-Berlin Reference Pion-Berlin2009); and the building of civilian expertise on military affairs (Barany Reference Barany2012, 353; Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017). Recent scholarship on civil-military relations in Latin America has been busy trying to identify how far the countries of the region have gone in fulfilling those conditions (Bruneau Reference Bruneau2013; Mares and Martínez Reference Martínez2014; Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017; Serra Reference Serra2010).

Another strand of the recent literature on civil-military relations proposes to shift the analytical focus from Samuel Huntington’s obsession with civilian control to issues related to military effectiveness and efficiency associated with that control (Bruneau and Matei Reference Bruneau2013; Croissant and Kuehn Reference Croissant and Kuehn2017; Pion-Berlin Reference Pion-Berlin2016; Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017). Investigation of such issues is key to answering the “so what?” question in the study of civil-military relations in democratic regimes, given that, as democracy consolidates, civilian control becomes a less relevant problem. In fact, the research questions posed by this strand and those outlined in the paragraph above are convergent: both emphasize the need to connect the study of civil-military relations with the analysis of defense policymaking, broadly speaking.

This article tries to contribute to this growing research agenda by using systematic data to address the following question: what are the policy consequences of growing civilian involvement in the defense sector? Brazil—a country that has recently been making some relevant strides in establishing civilian control of the military but is still a laggard compared to its Southern Cone counterparts (Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017)—will provide the case study. In addition, this country is located in a region where the external security environment has not changed during the period covered by this study, 1996–2012. This means that changes in defense policy have been driven mostly, but not exclusively, by changes in the balance of power between civilians and the military and in civilian preferences, as we can control for the security environment.

One of the main contributions of this article will be to present more fine-grained indicators of, and data on, civilian participation in defense policymaking, and its defense policy consequences in Brazil, than those offered by the comparative literature cited above. Those studies rely mostly on constitutional, legal, and institutional measures of the democratization of civil-military relations (henceforth CMR) in Latin America. These measures are certainly the most relevant to comparatively analyze CMR, but the existing literature tends to apply them in a casuistic fashion. The idea here is to supplement them with systematic quantitative information.

Moreover, anyone who has tried to obtain precise and reliable data on the relative shares of civilian and military personnel working at Brazil’s Ministry of Defense has failed to do so because the ministry treats retired officers as civilians. This obviously overestimates the weight of civilians and underestimates that of the military. This article offers a partial solution to this problem by means of a close look at the makeup of the committees that drafted the 1996 and 2005 National Defense Policies and the 2012 White Paper on National Defense. By doing so, this research is able to differentiate not only between civilians and retired officers but also between “co-opted” civilians (those who work at military institutions and thus tend to share the preferences of the military) and “authentic” civilians. Such differentiation is key for developing fine-grained indicators of the balance of power between civilians and the military in Brazil. To the author’s knowledge, the phenomenon of “co-opted” civilians is largely Brazilian. However, future research may eventually find functional equivalents in other countries.

This article proceeds to describe how civilian direction of defense policy has evolved since the country democratized in 1985. It offers some hypotheses regarding the policy consequences of greater civilian involvement in the defense sector, and then associates those hypotheses with changes in defense policy orientation. To do so, the analysis first evaluates the political makeup of the committees that drafted the 1996 and 2005 National Defense Policies and the 2012 White Paper on National Defense. Then it attempts to establish the links between, on the one hand, the makeup of drafting committees, and on the other, the documents’ directives on interoperability, operations outside the national territory, and coordination between defense and diplomacy. Empirical data—mostly quantitative—on the implementation of such directives are provided, and final conclusions are drawn from the analysis.

Civilian Involvement in Defense Policymaking in Brazil

In their recent book on the democratization of CMR in the Southern Cone, Pion-Berlin and Martínez (Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017) demonstrate forcefully that, as compared to Argentina and Chile, Brazil, along with Uruguay, is a laggard in most of their evaluation criteria. As regards specifically the building of defense institutions, despite some recent progress, Brazil is still an underperformer in terms of properly organizing a civilian-led ministry of defense, a joint military staff, a national defense council, and congressional defense committees (Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017, 167–210). In their words,

And yet there has been an internal delegation of vital tasks to military agencies and personnel in Brazil and Uruguay, where the general and JMSs [Joint Military Staffs] have taken on (or have been granted) the most important defense-related assignments, leaving it to civilians to handle administrative, personnel, accounting, and legal issues. Ironically, as these democratic governments, through their ministries, have attained higher levels of political control over the armed forces, they have ceded authority to officers to do the actual defense planning within those very ministries. This is why, in our view, Brazil and Uruguay are still in a transitional phase of ministerial development. (Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017, 207)

The literature by experts on CMR and defense policymaking in Brazil widely corroborates Pion-Berlin and Martínez’s findings (C. Almeida Reference Almeida2010; Alsina Reference Alsina Júnior2009; Brigagão and Proença Reference Brigagão, Proença, Lúcia and Octávio Cintra2015; Bruneau and Tollefson Reference Bruneau and Tollefson2014; D’Araujo Reference D’Araujo2010; Cepik and Licks-Bertol Reference Cepik and Licks-Bertol2016; García Reference García2014; Winand and Saint-Pierre Reference Winand and Luis Saint-Pierre2010; Zaverucha Reference Zaverucha2006). Yet there is still a gap in the comparative and country-specific literature on Brazil’s CMR that needs to be addressed: the lack of precise empirical assessment of the extent of civilian participation in defense policymaking. All the texts cited above highlight the increasing involvement of civilians in the drafting of the country’s main national security strategy documents since the mid-1990s. However, the degree of that involvement has varied from document to document. This variation and its policy consequences need to be investigated so we can have a better understanding of the actual benefits (or lack thereof) of civilian control, other than democratic consolidation. Thus, what does greater civilian involvement mean in terms of defense policy choices and implementation? Tackling this issue is the contribution of this article to the scholarly debate on CMR in Brazil and the Southern Cone.

That said, table 1 provides data on the political makeup of the committees that drafted the 1996 National Defense Policy (NDP 1996), the 2005 National Defense Policy (NDP 2005), and the 2012 White Paper on National Defense (WP). Despite its importance, the 2008 National Strategy of Defense (NSD 2008) is not included in the sample because it was meant to present the operational instruments of Brazil’s defense policy. Moreover, the NSD 2008 drafting committee was not meant to be inclusive.Footnote 1 So NSD 2008 is of a different nature than that of the other three documents, and should thus be set apart. However, the political makeup of the workshops that contributed ideas to the committee that drafted the White Paper (henceforth, those workshops will be labeled WPworks) is also included.

Table 1. Makeup of the Drafting Committees of Brazil’s National Security Strategy Documents, 1996–2012

All categories and their respective subcategories reported in table 1 are self-explanatory, except for “authentic civilians” and “co-opted civilians.” The latter are civilians who work or have had a close professional association with military institutions, particularly the military schools, such as, for example, the General Staff and High Command School of the Army (ECEME), the Naval War College (EGN), the General Staff and High Command School of the Air Force (ECEMAR), or the Superior War School (ESG). Civilians who work there tend to espouse the same worldview and political and defense policy inclinations as the military; otherwise they would not have been hired in the first place, given that Brazil’s military schools have been historically closed to outside influences (Proença Reference Proença2000). This is conventional wisdom in Brazil. Things have been changing recently, but the senior civilians who still work at those schools come from this closed world.

Therefore, it is relevant to pin down those co-opted civilians, so the effective participation of civilians in the drafting of the three documents can be validly gauged. Thus, authentic civilians exclude co-opted civilians and diplomats. It is also relevant to identify the number of diplomats among the civilians to check the former’s impact on defense-diplomacy coordination. Therefore, the measure of the effective civilian contingent on the drafting committees is the sum of authentic civilians and diplomats.

Here is the effective civilian contingent on each drafting committee and the White Paper workshops: NDP 1996 = 44.4 percent; NDP 2005 = 76.6 percent; WP = 66.7 percent; WPworks = 32.3 percent. The average effective civilian contingent is 55.0 percent, with a standard deviation (SD) of 15.5 percent. Military officers have the following figures: NDP 1996 = 55.6 percent; NDP 2005 = 19.1 percent; WP = 33.3 percent; WPworks = 54.8 percent; averaging 40.7 percent (SD = 15.3 percent). Co-opted civilians: NDP 1996 = 0 percent; NDP 2005 = 4.3 percent; WP = 0 percent; WPworks = 12.9 percent; averaging 4.3 percent (SD = 5.3 percent).

There is thus considerable inter-and intracategory variation. While civilians were in the minority on NDP 1996 and WPworks, they held ample majorities on NDP 2005 and WP. Given that NDP 2005 and WP were the most important documents drafted in the period, real progress was made in terms of civilian participation in defense policymaking. Surprisingly, the drafting body that had the highest effective civilian contingent was not the white paper workshops. According to the very white paper, “The Ministry of Defense, including the Armed Forces, has created mechanisms and programs which contribute to the increase of social participation in defense and security issues” (Brazil 2012, 170). Actually, the makeup of the white paper workshops made civilian participation decrease relative to its peak under NDP 2005. This was due to the high number of co-opted civilians (12). The number of diplomats in the white paper workshops is also very small (1). At any rate, while Brazil has not yet reached civilian supremacy as far as the direction of defense policymaking is concerned, substantial improvement was achieved.

Table 1 also indicates that one of the potential ways the Brazilian military has been able to retain its influence over defense policymaking is the appointment of co-opted civilians to defense policy–drafting committees. Co-opted civilians provide the double benefit of formally being civilians but with military-friendly preferences. The number of co-opted civilians was relatively high, particularly on WPworks. However, given that this was not the most important committee, the role of such civilians should be viewed carefully.

Now the question is, what are the policy consequences of varying effective civilian participation in the directives found in national security strategy documents? To answer this question, we need first to come up with hypotheses regarding such participation.

The Policy Consequences of Civilians in the Defense Sector

In the past three decades, the main issues of CMR have evolved from military meddling in politics to defense policy management in many Latin American countries (Pion-Berlin Reference Pion-Berlin2016). This is a most welcome development from the point of view of democratic consolidation. Once civilians in a Southern Cone country that had a military regime begin to take a growing participation in defense policymaking, what should we expect in terms of defense policy orientation?

This article argues that growing civilian direction of the defense sector should generate, ceteris paribus, three consequences: greater interoperability; a stronger emphasis on operations outside the national territory—let us call it stronger “exter-nalism”—and better coordination between defense and diplomacy. Why?

Greater interoperability is precisely one of the main reasons why armed forces are willing to accept a civilian-led MOD. Interoperability is key to maximizing the effectiveness and efficiency of the defense sector as a whole (Pion-Berlin and Ugarte Reference Pion-Berlin and Manuel Ugarte2013b, 15). Military history is full of cases of interforce disjointedness that led to enormous waste of lives and treasury, duplication of efforts, unnecessary mistakes, and ultimately, military defeat. If each branch of the armed forces has its own ministry, coordination among the forces is much more difficult because the head of each of them will have more incentives and resources not to make concessions to the other forces.

Each branch will be more likely to defend its own turf tooth and nail and to see its relationship with the other branches as a zero-sum game. That is, without a civilian-led MOD, what Americans call servicism will be rampant (Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017, 170). Military and civilian leaders easily perceive all those risks and see the MOD as the best instrument to minimize them. So here we have a first hypothesis to assess defense sector reform over time, which can be stated as follows: the more extensive civilians’ participation in defense policymaking, the more interoper-ability norms and practices should be adopted, ceteris paribus.

Note that the military may change its views on interoperability and, over time, may see it more favorably. According to Antonio Jorge Ramalho, a top civilian adviser to Brazil’s Ministry of Defense and Secretariat for Strategic Affairs in the 2000s and 2010s, officers working on the joint staff, created in 2010 to promote interoperability, “start to open their minds to the necessity of coordinating actions” (quoted in Dreisbach Reference Dreisbach2016, 6). While in a few cases the military itself may be the primary mover in promoting interoperability, the latter is always difficult and heavily dependent on civilian leadership.

A classic example is Wilhelmine Germany. Before and during World War I, the German army and navy never consulted each other—and were never made to consult by their civilian masters—about their respective war plans, resulting in an impressive waste of potentially combinable resources for a country surrounded by powerful enemies (Afflerbach Reference Afflerbach, Mombauer and Deist2004). In Brazil it was precisely a heated conflict over carrier aviation between the Navy and the Air Force in 1995, and the need for strong political leadership to promote interservice cooperation made clear by this squabble, that led then-president Fernando Henrique Cardoso to establish a committee that would draft the first official study on the creation of a ministry of defense (Alsina Reference Alsina Júnior2006, 106–8).

Stronger externalism also has to do with Southern Cone history. Given the sub-region’s past of military meddling in politics and military regimes, it is clear that a defense policy that places a heavy emphasis on domestic or internal missions for the military is risky in terms of civilian control, as emphasized by some prominent students of CMR (Desch Reference Desch1999; Loveman Reference Loveman1999; Stepan Reference Stepan1986). Pion-Berlin and Martínez (Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017) consider withdrawal from internal security key for the democratization of CMR.

Moreover, there is a potential trade-off between internal missions and external ones, particularly expeditionary action, in terms of military preparation. An officer who has to expend effort X to prepare for policing favelas will, of necessity, incur an opportunity cost in terms of preparing, for example, for infantry action in interstate conflicts. Some military leaders may like internal missions because the latter sometimes may provide the armed forces with more budget and political influence. In any case, the trade-off between internal missions and military effectiveness in external missions is undeniable, as recently and forcefully shown by White (Reference White2017).

Civilian leaders understand this trade-off, although they may be resigned to promoting internal missions out of sheer pragmatism (Pion-Berlin Reference Pion-Berlin2016). At any rate, our second hypothesis might be, the more extensive civilian involvement in defense policymaking, a stronger emphasis on external missions should be expected, ceteris paribus.Footnote 2 External missions consist of expeditionary action or peacekeeping. While peacekeeping often resembles police work (Sotomayor Reference Sotomayor2014), the former’s key aspect, for the purposes of this study, is its location outside the national territory.

The hypothesis about externalism, however, needs to be better explained in light of the literature on military missions in democratic Latin America. Pion-Berlin and Arceneaux (Reference Pion-Berlin and Arceneaux2000) show that there is no intrinsic reason why a military should be more subservient to political leaders just because it is engaged in a foreign mission. In addition, based on a study of Argentina and Venezuela, Pion-Berlin and Trinkunas (Reference Pion-Berlin and Trinkunas2005) provide evidence that armies cannot easily translate domestic roles into political power. More recently, Pion-Berlin (Reference Pion-Berlin2016) has argued that if Latin American armies are deployed in domestic missions for which they have proper preparation, such armies can be effective, and the trade-off referred to above does not necessarily take place. This article does not challenge these relevant points. The hypothesis developed here is simply that civilians are likely to promote more foreign missions and fewer internal missions as they get more involved in defense policymaking. This task is certainly facilitated when the armed forces are reluctant to take on internal roles.

With regard to coordination between defense and diplomacy, Posen states, “A military doctrine may harm the security interests of the state if it is not integrated with the political objectives of the state’s grand strategy—if it fails to provide the statesman with the tools suitable for the pursuit of those objectives” (1984, 16). Civilian control of the military is thus essential not only to safeguard democracy but also to promote what Posen calls political-military integration, “the knitting together of political ends and military means” (1984, 25). Defense-diplomacy coordination is therefore vital for the effectiveness of a country’s grand strategy. If interforce coordination is extremely difficult without a civilian-led MOD, even more so is coordination between the diplomatic corps and the branches of the armed forces. Moreover, while defense-diplomacy coordination may often fail because of bureaucratic politics, civilian elites in democratizing countries are likely to prefer such coordination as a sort of “policy handle.”Footnote 3 They could use it to reduce the autonomy on international security issues that the military enjoyed during the previous authoritarian regime and the transition period.Footnote 4

Is there any evidence that Brazilian civilians hold the preferences over defense policy postulated above?

At the elite level, Souza (Reference Souza2009) presents data based on a survey applied to 150 members of Brazil’s foreign policy community (there are only 5 military in the sample, so the survey is overwhelmingly an expression of civilian elites’ opinions). In 2008, 27 percent of the respondents answered that relocating existing military units from the South and Southeast to the Amazon was of “extreme importance,” while 48 percent considered it to be “very important” and 25 percent thought it was of “little or no importance.” These figures suggest that there is ample majority support, albeit indirect, for externalism, because such relocation removes the armed forces from the main political and economic centers of the country and redirects them to a frontier region with many defense-related problems. Moreover, the foreign policy community strongly believes that Brazil should participate in UN peace-keeping (74 percent of the respondents agreed to this proposition). This is evidence that corroborates the idea that civilians want the military to operate outside the national territory.

However, in 2008, 27 percent of the respondents also considered training troops to perform law-and-order operations to be of “extreme importance,” while 26 percent reputed it to be “very important,” and 46 percent of the respondents said that such training was of “little or no importance.” Thus, Brazil’s foreign policy community appears to be divided over such internal operations.

Furthermore, 66 percent of the respondents in 2008 answered that the integration of the strategies pursued by each branch of the armed forces under the command of the Ministry of Defense was of “extreme importance,” while 29 percent considered it to be “very important.” Thus, there was near unanimity as far as inter-operability was concerned.

At the public opinion level, Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira Júnior, Edison Benedito, Fracalossi de Moraes, Marcelo and Schia vinatto2014) describe the answers to questions about national defense in a mass survey conducted by IPEA, a Brazilian government think tank, in 2011. A majority of Brazilians believed that it was the military’s role to assist police forces in fighting crime: 58.1 percent versus 41.9 percent. However, Brazilians were divided over whether the armed forces should provide medical and social services to the population: 50.3 percent of the respondents believed that this was not the military’s role, while 49.7 percent believed that it was. When it came to building roads and railways, 79 percent of the respondents said that the military had no responsibility for it, while 21 percent disagreed. In addition, 57.3 percent of the respondents believed that fighting terrorism was not a responsibility of the armed forces, while 42.7 percent thought it was. These figures can be construed as a lack of majority support for internal missions. Surprisingly, 66 percent of the respondents said they were against peacekeeping operations, while 34 percent were favorable to them.

In sum, as far as the two surveys described above allow one to say anything about Brazilian civilians’ preferences for defense policy, elites seem to like the idea of redirecting military operations away from the national territory and are keen on integrating the three branches of the armed forces. However, while elites are divided over the most sensitive internal military operation (the enforcement of law and order), mass opinion favors it. Moreover, mass opinion is against peacekeeping operations. Thus, assuming some measure of stability in preferences over time, while there is some survey data supporting the notion that Brazilian civilian elites tend to be inclined toward “externalism” and “integrationism,” the mass public seems to be more “internalist” than elites as far as policing functions are concerned. There are no survey data on defense-diplomacy coordination.

All said, given that civilian participation in defense policymaking is mostly an elite affair, we can expect that the civilian preferences that affect national security strategy the most are those of the elites rather than those of the mass public. This also means that the propositions regarding civilian preferences developed above are not wide off the mark.

The Defense Policy Orientation of Brazil’s National Security Strategy Documents

The drafting and defense policy options of Latin America’s national security strategy documents have been receiving growing attention from scholars (Pion-Berlin and Ugarte Reference Pion-Berlin and Manuel Ugarte2013a; Pion-Berlin Reference Pion-Berlin2016, 41–72; Quintana Reference Quintana2001; Sepúlveda and Alda Reference Sepúlveda and Alda2008). Brazil’s are no exception. There are now several works on them (C. Almeida Reference Almeida2010; P. Almeida Reference Almeida2010; Alsina Reference Alsina Júnior2009; Bertonha Reference Bertonha2010; Brands Reference Brands2010; Cepik and Licks-Bertol Reference Cepik and Licks-Bertol2016; Dreisbach Reference Dreisbach2016; Duarte Reference Duarte2014; Lima Reference Lima2013; Mares and Trinkunas Reference Mares and Trinkunas2016, 85–107; Proença Júnior and Diniz Reference Proença, Diniz and Hans2008; Seabra Reference Seabra2014; Stolberg Reference Stolberg2012; Villa and Viana Reference Villa and Viana2010). Yet no work has yet tried systematically to associate the makeup of Brazilian national security strategy documents’ drafting committees with their defense policy orientations. To do so, this study evaluates the three hypotheses fleshed out above by confronting the data exhibited in table 1 with the guidelines of the 1996 National Defense Policy (NDP 1996), the 2005 National Defense Policy (NDP 2005), and the 2012 White Paper on National Defense (WP) summarized in tables 2 and 2.1.

The 1996 National Defense Policy

The 1996 National Defense Policy (NDP 1996) was drafted under the first term of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995–99). He was the second democratically elected president since 1985. Ten years after the end of military rule, it was expected that Brazil’s defense policy would assign a more specific role to the armed forces. The creation of the Ministry of Defense was Cardoso’s campaign promise and would become the flagship of his defense policy.

The creation of the ministry was the result of a bargaining process that began in 1995 and ended in 1999 (Alsina Reference Alsina Júnior2006, 126). The process included the drafting of the National Defense Policy, a declaratory document hitherto nonexistent because during the military period (1964–85) the paper that determined Brazil’s defense policy was the National Security Doctrine, which focused almost exclusively on fighting the “internal enemy.”

In 1995, as mentioned above, after a squabble between the Navy and the Air Force over which branch would have jurisdiction over carrier aircraft, President Cardoso issued an order creating the Chamber of Foreign Relations and National Defense (CREDN) and instructed its members to initiate the drafting of a national defense policy. The drafting committee was composed of ministers and deputy ministers. A total of 18 government officials participated in the drafting of NDP 1996, 8 civilians (44.4 percent) and 10 military officers (55.6 percent). Three diplomats were among the civilians, and no co-opted civilians.

Table 2 summarizes the key NDP 1996 directives on “externalism” versus “internalism,” interoperability, and defense-diplomacy coordination. The document has a generalist content, with several statements common in the discourse of Brazil’s foreign policy. The most relevant aspects are the absence of separate roles for the Navy, Army, or Air Force and the superficial approach to interoperability.

Table 2. Brazil’s Defense Policy Directives

TABLE 2.1. White Paper 2012 Directives on Internalism versus Externalism, per Branch of the Armed Forces

Sources: NDP 2005; WP 2012.

NDP 1996 was essentially an effort to legitimate the need for a defense system in the post–Cold War period, emphasizing the relevance of stability and democracy and directing, in a vague and timid manner, the armed forces to fight foreign threats. However, the document outlines, in a more precise fashion, traditional domestic roles of the armed forces (protection of the Amazon, involvement in national integration, safeguarding democratic institutions).

Overall, 8 of the document’s 11 directives have to do with foreign policy issues. Defense-diplomacy coordination is thus one of the boldest aspects of NDP 1996. This was very likely the consequence of the 3 diplomats on the drafting committee, representing 16.7 percent of the committee membership and 37.5 percent of the civilians. While in terms of raw numbers, 3 diplomats were unlikely to override the 10 military officers on the committee, the considerable influence exerted by the former had to do with the key role played by Ronaldo Sardenberg, then secretary for strategic affairs. A respected ambassador with a long history of interest in the area of strategic studies, Sardenberg also had a good personal rapport with President Cardoso, as shown by Alsina’s detailed account of the making of NDP 1996 (2006, see esp. 109).

All told, NDP 1996 seems to corroborate the hypotheses regarding interoper-ability and defense-diplomacy coordination. In addition, given the high number of military officers on the drafting committee (55.6 percent) and the vagueness or weakness of the directives on “externalism,” the document seems to uphold the third hypothesis, too.

The 2005 National Defense Policy

The 2005 National Defense Policy (NDP 2005) was drafted during the first term of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003–7). After three unsuccessful attempts, Lula was finally elected president in October 2002. Of humble origins and leader of a left-wing party, the Workers’ Party (PT), Lula’s rise to the highest office would inevitably be a turning point in Brazil’s history. This included civil-military relations.

NDP 2005 deepens the content of NDP 1996 by offering more detailed policy directives. The 2005 policy was elaborated through a host of meetings convened by Ambassador José Viegas Filho, then minister of defense. The committee that drafted NDP 2005 had the largest membership of the three committees analyzed here (47) and the highest effective civilian contingent (76.6 percent). The NDP 2005 committee also harbored the highest number of diplomats, 6 (12.8 percent of the total membership, 16.7 percent of the effective civilian contingent).

The larger participation of civilians in NDP 2005 than in NDP 1996 seems to have generated some of the consequences expected by the hypotheses proposed in this study. In terms of externalism, the 2005 document is broader and more specific than the 1996 one: it determines that Brazil can participate in collective defense arrangements authorized by the UN and in peace and humanitarian operations; and, more important, NDP 2005 states that the country should have the necessary means to patrol and project power in the South Atlantic.

As regards interoperability, NDP 2005 is more specific than NDP 1996, given that it explicitly advocates flexibility and interoperability, also emphasizing potential mobilization and Brazil’s need to have modern, balanced, and prepared armed forces.

Concerning defense-diplomacy coordination, it seems that the decrease in the percentage of diplomats on NDP 2005 relative to NDP 1996 led to a weaker emphasis on the integration of foreign and defense policies. Only 6 of the 26 directives of NDP 2005 are closely related to foreign policy. The 6 directives focus on intensifying exchanges with the armed forces of South America and South Atlantic African countries, fostering international partnerships in defense technology, supporting peacekeeping missions, and increasing the country’s influence in the international arena.

The 2012 White Paper on National Defense

The 2012 White Paper on National Defense (WP) was drafted under the first term of President Dilma Rousseff (2011–15). The white paper is meant to be a communication tool of the Brazilian state, with its national society and a confidence-building measure, toward the international community as regards Brazil’s goals, institutions, and resources for national defense. The New Defense Law, promulgated in August 2010, mandates that this kind of document be published every four years.

The white paper was drafted by a committee, and, unlike the other two documents, also received ideas and suggestions from six thematic workshops where civilians should have had a majority. Yet although one of WP 2012’s stated goals was to promote civil society participation in defense organization, as table 1 indicates, if we take into account the presence of co-opted civilians, the effective civilian contingent in the total membership of the workshops was less than a majority (32.3 percent). Maybe this was not a great problem, because the workshops’ role was secondary to that of the drafting committee. However, symbolically, this effective civilian minority in the workshops should be seen as a setback from the goal of promoting greater societal involvement in security affairs.

And here one can also see another potential way that the Brazilian armed forces have been able to retain their still-ample influence over defense policymaking: through the appointment of co-opted civilians to defense policy–drafting committees. This is a smart ruse, given that co-opted civilians provide the double benefit of giving the appearance of civilians but ultimately holding military-friendly preferences.

Let us now focus on the WP 2012 drafting committee. Its membership was 21, with 66.7 percent of effective civilians (12 authentic civilians and 2 diplomats; see table 1). Here, civilian preponderance is clear. As for their impact on the WP directives, tables 2 and 2.1 suggest that the three hypotheses fleshed out in the previous section are borne out. Actually, WP 2012 is probably the most emphatic document on externalism, interoperability, and defense-diplomacy coordination. Note that the directives on the Navy’s external missions clearly mention the Marine Corps as an expeditionary force.

All said and done, comparing table 1 with tables 2 and 2.1 provides suggestive associations between the degree of civilian participation in defense policymaking and the degree to which national security strategy documents place emphasis on external missions, interoperability, and defense-diplomacy coordination.

Empirical Trends

To deepen the analysis of the policy consequences of greater civilian participation in defense management in Brazil, it is important to go beyond the directives enshrined in national security strategy documents and check whether the promises of the defense directives have been implemented. Quantitative data on interoperability and troops engaged in military operations inside and outside Brazil’s national territory, information on the creation of institutional mechanisms of defense-diplomacy coordination, and numbers of official meetings between the minister of defense and the minister of foreign relations can help answer this question. It is expected that, over time, interoperability rates go up, military operations become more externally focused, and more defense-diplomacy coordination mechanisms are created.

Interoperability

To empirically assess interoperability, the first step is to classify military operations. Here they are divided into five categories: law and order (their acronym in Brazil is GLO), peace operations, civic action (their acronym in Brazil is ACISO), humanitarian relief, and national defense.

For GLO operations, the armed forces are granted police power and are tasked to enforce law and order. There is a constitutional provision (Article 142) on these operations, as well an organic law (Lei Complementar 97, 1999); an ordinary law promulgated in October 2017 that stipulates that crimes committed by troops during a GLO operation will be judged by military justice (Lei 13.491/17); a presidential decree (Decreto 3897, 2001); and a number of ordinances by the Ministry of Defense (Brazil 2014). While a GLO operation has to be signed by the president, Congress, the judiciary, subnational executives and legislatures, and judges are empowered by the constitution to request such operations. Any GLO operation must have a specific goal, and its location and duration are restricted.

As for civic action operations (ACISO), in Brazil they are ad hoc, socially oriented deployments, which take place in small municipalities or poor communities, usually near the country’s vast borders. They range from medical officers performing consultations or giving lectures to raise awareness of best health practices to streamlining bureaucratic processes to obtain documents, free haircuts, and so on. They also serve to disseminate ways to join the military.

ACISO operations are not to be confused with humanitarian relief operations. The latter take place when the military is called in to act in the wake of natural disasters, such as floods, forest fires, or huge landslides. Brazil’s armed forces provide relief to endangered communities or populations, as they did in the 2011 landslides in the mountainous region of Rio de Janeiro or the floods in the state of Rondônia in 2014.

Many of the operations in which the Brazilian armed forces are engaged have to do with national defense. These include a wide range of activities aimed at protecting the national territory and strengthening the national state’s presence along Brazil’s porous borders. Most operations in this category exist under the umbrella of the Strategic Border Plan of 2011. Many civic action operations are also performed to further the objectives of this plan. Three national defense operations should be highlighted: Operation Sentinela, led by the Ministry of Justice, which brings together the investigation and intelligence sectors of the armed forces and other national security agencies (the Federal Police and the National Force); Operation Ágata, led by the Joint Staff of the Armed Forces (EMCFA), which deploys the military along the borders in specific actions to curb drug and weapon trafficking, contraband, illegal immigration, and so on; and SISFRON, led by the Army, which aims to implement an integrated border monitoring system through various technological means by 2020.

Note that an operation can be classified as more than one type, which causes the totals not always to amount to 100 percent. Then, interoperability rates are calculated. Those in which more than one service participated are considered to be joint operations. These joint operations are always planned, coordinated, or monitored by the Joint Staff of the Armed Forces—at least since its creation in 2010.

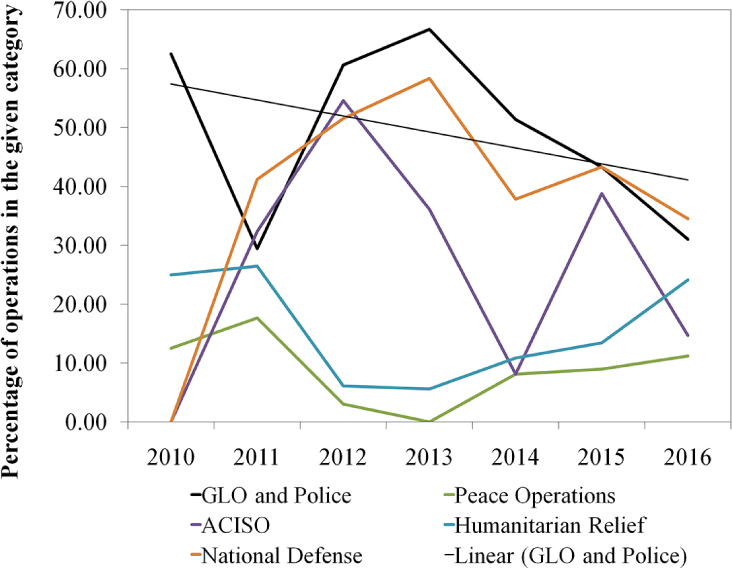

The data used to analyze military operations in Brazil are based on the coding of the news releases published on the Ministry of Defense website. This source presents three problems. Some confidential operations are not publicized by the ministry; coding the operations entails a measure of subjectivity; and if an operation is the topic of more than one news release, it will be counted more than once. However, these problems do not mean that this kind of data is not a useful source of information, especially when it comes to identifying trends. This is because omissions are very likely to be equally or almost equally distributed among different types of operations. And frankly, there is no other way of assessing military operations in Brazil. Furthermore, note that although the Ministry of Defense has published news about operations since 2006, such items were very scarce before 2010. This is the reason why the years 2006–2009 are omitted. Figures 1–3 and tables 3 and 4 report data on military operations per year only for 2010–2016.

Figure 1. Total Number of Reported Military Operations in Brazil, 2010–2016

Figure 2. Types of Reported Military Operations in Brazil per Year, 2010–2016 (percent)

Figure 3. Total Number of Reported Military Operations and Joint Military Operations in Brazil per Year, 2010–2016

Table 3. Types of Reported Military Operation in Brazil per Year, 2010–2016 (percent)

Source: Ministry of Defense

Table 4. Number of Reported Military Operations and Joint Military Operations in Brazil per Year, 2010–2016

Source: Ministry of Defense

The figures and tables make clear that the frequency of joint military operations has been growing since 2010, quantitively corroborating Cepik and Licks-Bertol’s (Reference Cepik and Licks-Bertol2016, 4) and Dreisbach’s (Reference Dreisbach2016, 14–15) positive qualitative assessment of the role played by the Joint Staff in promoting interoperability. Although the time series is small, the trend reported in figure 3 suggests that Brazil has been moving in the direction expected by the hypothesis in this study.

As for the types of operations in which the Brazilian armed forces engaged in 2010–2016, the positive trend is that national defense operations grew over this period. The negative trend is that GLO operations were the most prevalent type in all years except 2016.

Military Operations Inside and Outside the National Territory

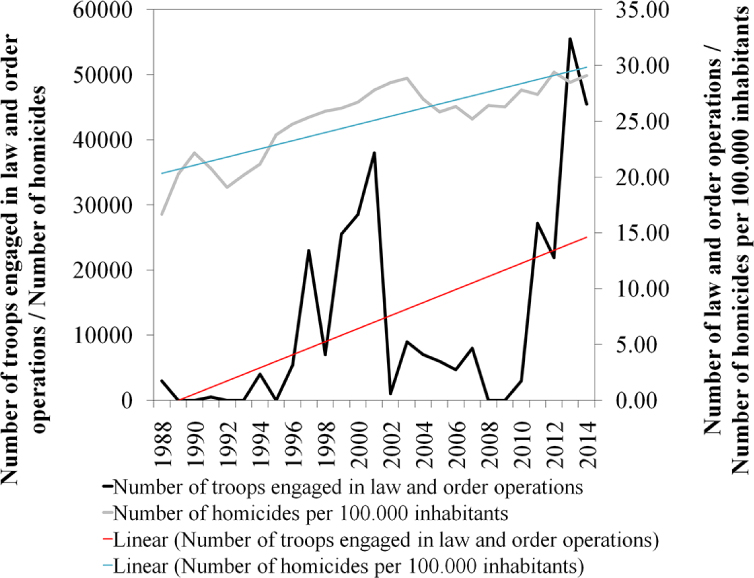

To quantitatively evaluate the degree of “internalism” versus “externalism” in Brazil, data on the number of troops engaged in UN peacekeeping and GLO operations per year were gathered. This is a more precise measure than the simple count of news items. Moreover, here the time series is more extensive than that reported above. Note also that because Brazil has not engaged in foreign wars since 1945, the number of troops engaged in UN peacekeeping operations is a valid indicator of the country’s externalism.

Figure 4 displays yearly data on the number of Brazilian troops engaged in UN peacekeeping operations in 1990–2014. The central trend is clear: this number grew steadily over this quarter of a century. Again, this evidence suggests that Brazil has been moving in the expected direction.

Figure 4. Brazilian Troops Engaged in UN Peacekeeping Missions per Year, 1990–2014 Source: Perry and Smith Reference Perry and Smith2013; United Nations 2014

Now data on externalism must be compared with data on internalism. The clearest expression of Brazilian armed forces’ internal functions is their engagement in law-and-order (or GLO) operations, as table 3 shows. Figure 5 displays data on the number of troops engaged in such operations per year in 1988–2015. The trends are unmistakable: internalism has been growing steadily in Brazil too. Why is this so?

Figure 5. Number of Troops Engaged in Law-and-Order Operations, 1988–2015

It is not mainly because the Brazilian armed forces still have a large legal role in internal security (as evidenced by Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017, 146–48). Such a role is just a necessary condition. The sufficient condition has to do with violence. The latter has been rising in the past three decades, as figure 5 eloquently demonstrates with yearly data on homicide rates. With ever-growing violence and deficient state police forces, state governments have been pragmatically resorting to the armed forces to enforce law and order when state police forces fail to do so. When the author of this article interviewed former minister of defense Nelson Jobim at his law firm in Brasília on December 6, 2012, and asked him about the reasons the Brazilian armed forces were still ordered to perform internal missions, he answered the following:

Just pragmatism. Of course, pragmatism. It is not simply occupation of space [by the armed forces]. And then, another thing, the governors themselves like [the internal missions], because then they do not need to invest in their [police] forces. There’s a weird logic there.

Thus, the linear trends displayed in figure 5 are a relative setback to one of this article’s hypotheses. While the eventual use of the armed forces in law-and-order operations is not necessarily bad for a developing democracy attempting to modernize its civil-military relations and defense sector (Pion-Berlin Reference Pion-Berlin2016), the upward trend in the employment of troops in such missions provides only moderate to weak reasons for optimism about the future of externalism in Brazil. Moreover, it should be emphasized that civilians have been the main driving force behind the growing employment of the armed forces in law-and-order operations, as acknowledged by Jobim.

Defense-Diplomacy Coordination

Evaluating progress in defense-diplomacy coordination involves focusing first on institutional arenas in which diplomats and the military regularly interact, where members of both the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Relations work together, where diplomats must deal with defense issues, or where Ministry of Defense officials must consider the diplomatic side of their policies. These mechanisms do not include informal interactions, such as academic courses or ad hoc work groups or meetings. The information presented here draws on several sources: email interviews, the Diário Oficial da União (the official gazette of the Brazilian government), standing orders of the Foreign Ministry, the official websites of the Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Defense, and the works of Castro and Castro (Reference Castro and de Oliveira Castro2009), Lins (Reference Lins2007), and Paiva (Reference Paiva2016).

Theoretically, the National Defense Council (NDC), enshrined in the 1988 Constitution, would be the first place to look. After all, it has the right to opine on matters of war, states of siege, federal intervention, and the use of security forces. Moreover, the ministers of defense and foreign relations have permanent seats on the council. However, presidents have rarely convened this group (Cepik and Licks-Bertol Reference Cepik and Licks-Bertol2016). As Pion-Berlin and Martínez state, “Brazil has made little progress in designing an NDC that is civilian and policy relevant” (2017, 189). Therefore, we should look in other places.

From the 1990s on, the executive branch has developed a growing number of coordination mechanisms. Efforts at the ministerial level have been much more frequent than at the presidential level. At the presidential level, the work groups charged to draft defense policy papers are the most relevant ones, but they have all been ad hoc. The Secretariat of Strategic Affairs (SAE), created in 1990; the Center for Strategic Affairs (NAE), created in 2003; and the Secretariat of Long-Term Planning, created in 2007, disbanded in 2015, and recreated in 2017, are basically iterations of the same agency, ended and created again. The fact that this kind of agency has been either created or recreated or renamed or extinguished 5 times over 27 years speaks volumes about its relevance.

At the ministerial level, a number of bodies arose from obligations undertaken by the Brazilian government in ratifying international treaties. The most important mechanisms, though, were established by the most relevant players, the Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Defense. The Foreign Ministry took the lead by creating the Secretariat of Diplomatic Planning in 1997. In the 2000s, a few divisions were created within the Foreign Ministry to address various issues associated with national defense, such as borders, regional cooperation, and trade promotion. The Ministry of Defense, in turn, was born in 1999, already with an important coordination mechanism: the Political-Strategic and Foreign Affairs Secretariat. A Division of Strategic Affairs was established within the Joint Staff of the Armed Forces (created in 2010). This division has been growing, and now it has one subdivision specializing in policy and strategy and another one focused on international issues.

Within the Foreign Ministry, the key step was taken in 2010 with the creation of the General Coordination of Defense Affairs (CGDEF), placed under the Secretary-General (or deputy minister) of the ministry. In 2016 it became the Department of Defense and Security Affairs. It now lies under the Undersecretariat for Policy on Multilateral, European, and North American Issues, which reports to the Secretary-General. While this seems to be a setback to CGDEF, only time will tell whether this agency has actually been downgraded.

As for quantitative data, table 5 displays information on the yearly number of official meetings between of the minister of defense and the minister of foreign relations from 2003 to 2016. While coordination efforts certainly take place at informal meetings or by means of phone calls or emails, the number of official meetings can reveal trends. In this sense, table 5 indicates that there is no upward trend relating to defense-diplomacy coordination.

Table 5. Official Meetings Between the Minister of Defense (MOD) and the Minister of Foreign Relations (MFR), 2003–2016

Source: Brazil, Ministry of Foreign Relations, through a formal request based on the Freedom of Information Law

In short, the very creation of the abovementioned coordination mechanisms in Brazil is a sign that the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Relations take the need to integrate defense and diplomacy more seriously than before. This points to the direction expected by the hypothesis in this article. However, as far as table 5 can tell, such mechanisms have not been really activated. So here is an intermediate situation: defense-diplomacy coordination is an institutional promise recently made by the pertinent ministries (through agency creation) but one that has yet to be fulfilled on the ground.

Conclusions

This article has attempted to contribute to the growing research agenda on the links between civil-military relations and defense policy in Latin America. Theoretically, it has argued that growing civilian direction of the defense sector should generate— in the Latin American context—three consequences: greater interoperability, a stronger emphasis on operations outside the national territory (externalism versus internalism), and better coordination between defense and diplomacy.

Empirically, the analysis of three national security strategy documents published in Brazil—the 1996 National Defense Policy, the 2005 National Defense Policy, and the 2012 White Paper on National Defense—along with data on the makeup of each of their respective drafting committees, has indicated that varying rates of civilian participation in defense policymaking committees have generated an impact on defense policy choices commensurate with the hypotheses fleshed out in the third section of this article.

However, in terms of defense policy implementation, there are varying degrees of success. Interoperability has made progress. Defense-diplomacy coordination has had a promising start with the creation of agencies within the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Relations, but this institutional promise, so to speak, has yet to be fulfilled on the ground. Externalism has not been a failure because in the period analyzed, the number of troops engaged in peacekeeping missions trended upward. But another upward trend in the number of troops engaged in law-and-order operations means that externalism is still far from successful.

Given Brazil’s history of military intervention in domestic politics, lack of intense geopolitical threats, and grave law-and-order problems, externalism was bound to be the most difficult area. However, this article has highlighted the fact that internalism is still rampant not only because of the armed forces’ legal role in internal security. The problem is more complex because the mass public is internalist and civilian elites are pragmatic about the domestic use of the military. Brazil is thus trapped in a vicious cycle. The military has ample prerogatives in internal security; crime rates keep rising; state police forces are deficient; civilians frequently call the armed forces to perform law-and-order operations; the mass public supports these operations; the military appreciates the short-term budgetary and reputational benefits generated by such operations; and the combination of all these conditions weakens civilian resolve to reduce military prerogatives in internal security. This cycle is probably not unique to Brazil.Footnote 5 Verifying whether it exists in other countries will shed light on the sources of military prerogatives and missions in developing democracies.

Future research should also try to apply the hypotheses and measures developed here to Brazil from 2017 on, and to other Latin American countries, particularly those of the Southern Cone.Footnote 6 The use of quantitative data on the balance of power between civilians and the military and on defense policy implementation is likely to provide a solid complement to the outstanding works on CMR recently published that rely heavily on constitutional, legal, and institutional indicators. It is also likely eventually to pave the way for more fine-grained, cross-national comparisons.