What explains the emerging patterns of paternity and maternity leave policy in Latin America? The pace of policy change has been rapid in recent years, marked by the introduction of new paternity leave measures, as well as the reform and expansion of longer-standing maternity leave policies. Sixteen of the major 18 countries in Latin America have implemented some form of paternity leave since 2000, ranging in length from 2 to 14 days, and many have increased statutory maternity leave. This trend, and variation in it, is particularly surprising, given the region’s historically conservative norms of gender relations and high reliance on nonpaid home care work, which is disproportionately performed by women (Rodríguez Enríquez Reference Rodríguez2012).

This article argues that variation in the new family leave policies is the product of contending visions of gender and the family. Rooted in political identities, such as religion and membership in political parties and civil society organizations, these visions shape the terms of debate and make particular policies take on symbolic importance. Three visions—which we term complementarity, gender parity, and workforce activation—serve as animating focal points for policy design and reform. However, symbols and ideas are not enough to make policy. Instead, they must be translated into proposals and laws, and this happens through institutional structures and procedures. In particular, in Latin America, the executive, legislature, and courts, as well as political parties, churches, and civil society organizations, have all played roles in the enacting (or alternatively, blocking) new paternity and maternity leave provisions.

This article begins by describing the recent trend of paternity leave adoption and maternity leave expansion and reform in the international arena and specifically in Latin America. In doing so, it presents a series of seven brief case descriptions that help illustrate the variation in policies across the region. It develops a theory that emphasizes how three competing visions of gender and the family have provided the rationale for the adoption of new family leave policies and how these visions have been mediated by institutions and actors. The article emphasizes that vanguard policies, like the newly articulated paternity leave policies, may be more contentious, and thus may require more support from partisan political leaders and female legislators to overcome opposition from conservative religious actors. In contrast, more mature policies, such as the region’s longstanding maternity leave policies, may have different, less contentious reform dynamics.

The study empirically tests its hypotheses about the factors shaping policymaking, using an original dataset on family leave policies in Latin America between 1970 and 2015, first analyzing paternity leave adoptions, and then comparing these patterns with results on maternity leave generosity. The article concludes with reflections on the forces and visions shaping family policy and what these portend for further policy development in the region.

The Expansion of Family Leave and Paternity Leave Policies

Family leave policies have been expanding significantly in scope and design around the globe since the turn of the twenty-first century. Broadly, these policies have shifted from a mid-twentieth-century emphasis on maternal support to a more inclusive understanding that accounts for fathers as well.

Maternity leave policies have existed since the mid-twentieth century in almost every country in the world and are longer in duration and more generous in benefits than recently introduced paternity leave measures. All but 2 of 185 countries surveyed by the International Labor Organization (ILO)—Papua New Guinea and the United States—guarantee at least partially paid maternity leave from the government, employer, or a combination of both (Economist 2015). Notably, the duration of maternity leave globally has increased significantly during the last 50 years. In 1970, mothers in developed countries had on average 17 weeks of leave available; by 2018 this had expanded to 51 weeks (OECD 2019).

Paternity leave, defined as a father-specific right to take a period of leave immediately following the birth of a child, is a more recent and less common policy (Huerta et al. Reference Huerta, Adema, Baxter, Han, Lausten, Lee and Waldfogel2013). While there is no international standard for paternity leave, in 2009 the ILO notably issued a resolution concerning gender equality, declaring that the reconciliation of work-family demands concerned both women and men and encouraging the adoption of a host of new measures—including paternity leave— to provide greater opportunities for new fathers to engage in family responsibilities (ILO 2009). By 2014, nearly half of the countries around the globe (70 of 167 surveyed) had taken the heretofore rare step of incorporating paternity leave entitlements into their national legislation (ILO 2014). These leaves vary dramatically in duration, ranging from a few days to much longer, with some countries in Europe offering fathers up to a year of paid leave, often with the freedom to divide this time over several periods during a child’s upbringing (Ray et al. Reference Ray, Gornick and Schmitt2008; Plantenga and Remery Reference Plantenga and Chantal2005; Bradshaw and Finch Reference Bradshaw and Naomi2002; Bruning and Plantenga Reference Bruning and Janneke1999). In developing and middle-income countries, these paternity leaves tend to be quite brief.

Latin American countries largely follow these patterns. Most countries in the region were relatively early adopters of maternity leave policies, establishing labor codes in the early to mid-twentieth century that regulated the work of pregnant women and paid maternity leave (Blofield and Touchton Reference Blofield and Michael2020). Indeed, in spite of its characterization as a region historically dominated by traditional gender roles, Latin America has a long tradition of following ILO recommendations, including Maternity Protection Convention No. 183, such that the majority of countries have 12 or more weeks of paid maternity leave (ECLAC 2011). Some countries, such as Venezuela, Chile, and Colombia, provide an even longer leave of 18 weeks or more for new mothers. Brazil guarantees its female public sector employees 6 months of paid leave (ECLAC 2011).

Most Latin American countries embraced paternity leave policies much later, at the start of the twenty-first century, and these have tended to range between 2 days and 14 days (see table 1). Nevertheless, the brevity and limited reach of these policies in the region—where anywhere from a third to three-quarters of the workforce operates in the informal sector—does not mean that they are not significant or contentious. On the contrary, they have received considerable attention, and once passed, they often are seen as an acquired right for those who enjoy them and an aspirational goal for those who do not yet have access to them.

Table 1. Comparison of Maternity and Paternity Leave in Latin America

Source: Authors’ elaboration from sources cited in text, including ECLAC 2017; World Bank; ILO; and countries’ laws and regulations as of 2020.

In the global distribution, then, Latin America stands in the middle of the pack. As of 2020, 16 countries in the region had adopted paternity leave provisions. The average duration of these leaves for fathers is between 2 and 5 days, with only a few countries boasting longer leaves. Ecuador offers 10 days and Venezuela 14 days (ILO 2014). A handful of countries provide no guaranteed paid leave for fathers. Somewhat surprisingly, as we will see below, leaders in maternity leave do not always have leading paternity leave policies. The examples of Costa Rica and Panama, both of which have generous maternity leave policies that comply with the ILO standard of 14 weeks, offer minimal leave for new fathers: in the former, leave is still guaranteed only for public sector workers, and in the latter, a three-day leave was not introduced until as recently as May 2017 (Costa Rica Reference Costa2013; Panama 2017).

To further appreciate how policies have changed since 2000, it is helpful to examine the experience of seven Latin American countries that were early adopters and reformers: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. These brief descriptions will serve to illustrate the three visions of family life that form the basis of this study’s theoretical argument developed in the subsequent section of the paper: parental coresponsibility, or parity; labor market activation; and gender complementarity.

Bolivia’s establishment of three days’ paternity leave in 2012 (Bolivia 2012a) represented a growing embrace of the first of these visions, that of gender parity and parental coresponsibility, which emphasizes equal roles for men and women in family life. Indeed, Labor Minister Daniel Santalla proclaimed that the legislation was intended to support the “parental responsibility” of fathers to help care for their spouse directly following childbirth (Bolivia 2012b). Furthermore, to ensure that fathers throughout the economy would be incentivized to take the full prescribed three-day leave, the decree was designed to pertain to both the public and private sectors, and it made the employer responsible for providing 100 percent salary compensation. The policy was enacted by decree by President Evo Morales, from the MAS (Movement Toward Socialism) party. It found ample support in the legislature, which, by 2014, was moving toward having the largest percentage of female legislators in Latin America (Singham Reference Singham2015). Likewise, rapid economic growth had sparked social change and the questioning of traditional family and gender norms (Vásquez Reference Vásquez2013).

In contrast, Brazil’s adoption of paternity leaves represents at least two competing visions of family life. The first, gender parity, can be observed in the early adoption of paternity leaves as part of Brazil’s rights-driven constitutional revision in 1993, making it one of the earliest countries in the region to do so (Macaulay Reference Macaulay2006). Later, the Brazilian courts played a critical role protecting and extending this vision. In 2003, the Supreme Court rejected a proposal that it said would have “facilitate[d] and stimulate[d] [firms’] option for male, instead of female, workers,” and ultimately “foster the discrimination that the Constitution sought to undercut” (Pargendler and Salama Reference Pargendler and Salama2015). And lest this be restricted to only a segment of the workforce, nearly a decade later, in 2012, the Brazilian Supreme Labor Court extended the right to maternity leave to workers on temporary contracts in an attempt to address social equity concerns and reduce the gap in labor force participation between high- and low-income female workers (Blofield and Martínez Franzoni Reference Blofield and Franzoni2014).

Beyond this framework of parity, Brazil has also pursued what we call labor market activation through family leave policies. Labor market activation focuses on ensuring that both women and men are able to participate fully in the labor market and sees leave policies tailored to diverse, gendered employment trajectories as a means to achieve this. In 2008, the Brazilian government established the Corporate Citizens Program (CCP), which offers tax deductions to larger employers that voluntarily extend their maternity leave provisions (Brazil 2008; Soares Reference Soares2008). The CCP was amended in 2016 to offer similar incentives to companies that offered enhanced paternity leave, raising the provisions from the statutory 5 days to 20 days (Taylor Reference Taylor2016).

Both of these new visions of family life were promoted by leaders across the Brazilian political spectrum, including those under the center-right President Fernando Henrique Cardoso and center-left Dilma Rousseff. Women’s voices also provided significant support, although representation in the National Congress was not sufficient to give them a decisive influence (Universo Online 2014).

Colombia’s family leave policy embodies a vision of gender complementarity, an often traditional view that places primary family care responsibility on mothers, and hence on maternity leave rather than paternity leave. Thus Colombia built its paternity leave policy on the foundation of its social security system, which relies heavily on maternity leaves. Its first provisions for paternity leave, adopted in 2002, determined the duration of leaves based on whether or not both parents were contributors to the country’s General Health System (Entidad Promotora de Salud, EPS). This legislation, known as María’s Law, allotted four days of leave if only the father was in the EPS and a more generous eight days if both parents were in the health system (Colombia 2002). In 2009, however, the Constitutional Court ruled that paternity leave should be universal: eight days in all cases (Colombia 2009). Two years later, this change was signed into Law 1468 (Colombia 2011).

For mothers, maternity leave has been gradually extended from the original 12 weeks, first to 14 weeks to meet the recommended ILO standard and then to a more generous 18 weeks in the Código Sustantivo del Trabajo (Colombia 2017). The slow process of change reflects the relatively conservative vision of family life that predominates in Colombia; it was sustained and championed by the governments from the political right, led by Álvaro Uribe and Juan Manuel Santos. And even though representation of women in the legislature was growing, with 19 percent of seats in the House and 22 percent of seats in the Senate held by women, pressure for more expansive change from these legislators was not successful (World Bank 2017).

Mexico’s approach to paternity leave and family policy has largely advanced a traditional view of the family, although recent efforts have employed a rhetorical framing of parity. When President Felipe Calderón enacted Mexico’s first paternity leave policy in 2012, the stated objective was to “promote responsible fatherhood to remove the stereotype of the absent father in the family” and foster “equity and coresponsibility between men and women” (Pérez Reference Pérez, Blum, Koslowski and Moss2017). However, this presidential initiative, which initially provided for a generous ten days of leave, was subsequently cut in half by the Chamber of Deputies (Aristegui Noticias 2015). Furthermore, because this paternity leave was covered by the employer, not by the government, many perceived a lack of symbolic governmental support for the “coresponsibility” rhetoric. And as this benefit applied only to fathers working in the formal economy, nearly 60 percent of male employees were not eligible for it, which raised questions about social equity (Peréz Reference Pérez, Blum, Koslowski and Moss2017). Although a proposed reform to Mexico’s federal labor law to substantially expand the country’s paternity leave from 5 days to 45 days to allow men to “exercise their right of paternity to the fullest” had been introduced starting in 2019, the prospects for its adoption remained uncertain.

Peru’s family policies reflect a longstanding orientation toward gender complementarity, but recent years have seen pressure for the promotion of more equal treatment of men and women. Toward this end, in 2010 President Alan García decreed a fairly limited paternity leave for all fathers working in the public and private sectors (Peru 2010). It guaranteed, at the employee’s request, four consecutive working days of leave. In addition, in March 2016, President Ollanta Humala issued a decree amending the right of Peruvian women to prenatal and postnatal leave to increase the leave provisions from a total of 90 days to 98 days (Peru 2016).

These reforms reflected demands arising from policy specialists, motivated legislators, and civil society, toward which recent governments from the center-left have been open but cautious. For example, in 2016, the Ministry of Women issued a proposal to extend paternity leave from 4 days to 15 days, calling for greater involvement of both parents, not just the mother, in the childrearing process (La República 2016). Later, in 2017, the extension of paternity leave—but only to 10 days—was reintroduced by Congresswoman Ursula Letona and cosponsored by other representatives of Fuerza Popular (Reyes Reference Reyes2017). A similar provision, introduced by Congresswoman Ana Choquehuanca of Peruvians for Change, sought to grant fathers the right to use pending vacation days as paternity leave immediately after the birth of a child (Paz Campuzano Reference Paz Campuzano2017). Both of these proposals were enacted into law the following year, enhancing paternity leave for private and public sector workers. The moment reflected new political power dynamics, given that in the 2016 election, women had won 27.7 percent of the seats in the Peruvian Congress, the highest number that female representation has reached in Peru since 2010, when paternity leave first passed (World Bank 2017).

Uruguay stands out in Latin America for its early adoption of social welfare policies at the beginning of the twentieth century and for its high levels of support for such policies throughout its modern history. Nevertheless, conventional gender norms were embedded in its family policy choices, resulting in mothers’ spending 2.7 times more than working fathers on domestic work time (OECD/ECLAC 2014). Employment-based family care policies did not make it onto a national campaign platform until 2009, when then–presidential hopeful José Mujica endorsed the Sistema Nacional de Cuidados, the National Care Plan—a plan backed by extensive feminist issue networks (Blofield and Touchton 2020). After considerable debate in both the public and private sectors, a reform bill was submitted to the legislature, resulting, in 2013, in Law 19161, which extended maternity leave, increasing its duration from 12 weeks to 14. When signed into law in January 2014 by President Mujica, it also offered paternity leave of 6 days (later increased to 10 days in 2015, with 3 additional days added in 2016). Congresswoman Berta Sanseverino from Frente Amplio argued that the provision “introduces the paradigm of shared responsibility between parents” in raising their children (Ultima Hora 2013).

Venezuela, the final example, boasts the most expansive vision of gender parity in Latin America. Adopted under President Hugo Chávez in 2007—well before that country’s economic crisis—the Law for the Protection of Families, Maternity, and Paternity guarantees 14 days of continuous paid paternity leave for new fathers. It emphasizes equality between parents regarding childcare: the father has the right to enjoy “conditions equal to the mother in the responsibilities and obligations relating to the care and assistance” of the birth of the new child (Venezuela Reference Vásquez2007). These paternity leave provisions were further defined in Venezuela’s 2013 labor law, the Ley Orgánica del Trabajo, los Trabajadores y las Trabajadoras (LOTTT), which prescribed job protection for fathers for up to 2 years following the birth of a child (Venezuela Reference Vásquez2012). It also expanded maternity leave from 18 weeks to 26 weeks.

This simultaneous expansion of both paternity and maternity leave generosity in Venezuela would seem to demonstrate a strong commitment to gender parity over complementarity. Feminist leaders took a leading role in the design of these policies, articulating their goals in a way that resonated with the larger socialist “Bolivarian” vision of Chávez. Indeed, as part of the consultation process for this new labor law, numerous feminist organizations jointly proposed a definition of labor that affirmed that “in a socialist society in construction, work should be … founded in solidarity, cooperation, and relations of equity and equality between men and women” (Gómez Reference Gómez2012).

Theory: Determinants of Family Leave

What factors account for these diverse patterns of expansion, most notably the recent rise of paternity leave policies? And to what extent do the explanations for the reform and expansion of maternity leave policies resemble or differ from those that shape paternity leave policies? The political science literature is largely silent on male-oriented family policies in Latin America, but recent work on the factors shaping maternity leave policy is helpful in understanding these different notions of family life and work (Blofield and Martínez Franzoni Reference Blofield and Franzoni2015, Reference Blofield and Franzoni2014; Piscopo Reference Piscopo2014). A seminal piece in this literature has evaluated policies based on their intended equity-enhancing effects, emphasizing whether (and how) they promote either “maternalism,” “coresponsibility,” or “social equity” (Blofield and Martínez Franzoni Reference Blofield and Franzoni2014).

Latin American and non–Latin American governments alike have historically implemented family leave policies focused on mothers, which emphasize perceived complementarity between the sexes. This model of “maternalism” is rooted in a belief that caregiving is the primary role of the mother (Molyneux Reference Molyneux2007; Molyneux and Dore 2000; Staab Reference Staab2012; Thomas Reference Thomas2011), and it sees maternity leave as the primary policy measure to support family life. It presumes heteronormative, female homemaker parental roles, despite the increased percentage of women entering the workforce and the “double burden” or “care squeeze” women face as they take on employment outside the home (Blofield and Martíinez Franzoni Reference Blofield and Franzoni2015).

The gender complementarity view sees paternity leave—to the extent that it is considered—as a means to ensure that fathers carry out their “responsibility” in helping mothers adjust after childbirth. The leave is intentionally short, designed to cover only a few days of initial return to the home. In other cases, it may be withheld altogether. In our classification, the vision of complementarity generally provides the shortest paternity leaves. Likewise, it is likely to provide only short maternity leaves as an encouragement for mothers to stay in the home for child rearing. The lack of parental leave policies has been shown to reinforce traditional gender roles, to lower the earnings of mothers relative to their spouses, and to create strong incentives for women to reduce their hours of employment (Ray et al. Reference Ray, Gornick and Schmitt2008).

The second vision, gender parity, aims to foster a mix of family life and labor in which men and women can be equal contributors in all spheres. In this view, a preference is given to an equal sharing of childcare responsibilities and working life, and it aims to redress the perceived shortcomings of the gender complementarity model (Rodríguez Enríquez Reference Rodríguez2012). Policies in this vein aim at “coresponsibility,” striving to acknowledge the role of women in various endeavors “as workers, not only as mothers,” as well as at “social equity,” aiming to treat men and women as equals in their work and family status across income groups (Blofield and Martínez Franzoni Reference Blofield and Franzoni2014, 9).

In the framing of gender parity, paternity leave policy provides an incentive for fathers to spend time in the home following the birth or adoption of a child, cultivating a lasting share of childcare and home maintenance responsibilities. This allows, at the same time, for mothers to be freed from some childcare burdens and participate more fully in the workforce. To the extent that it is adopted, it favors longer paternity leaves and maintaining maternity leaves (but it is not overeager to extend those maternity leaves).

The third vision, workforce activation, sees Latin America’s rise in female labor force participation in recent decades as a positive and productive development for long-term growth, and it aims to encourage the continuation of that trend (SEDLAC 2020). The workforce activation frame fosters family policies that facilitate the rapid return to the workforce of both mothers and fathers after childbirth (Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Smith and Verner2006; OECD 2013). In particular, family leave provisions aim to grant greater parental independence in society, especially for mothers, so as to freely participate in the labor market through maternity policies that “preemptively socialize the costs of familyhood” (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). Paternity leave is likely to follow a similar logic, especially given its potential to ease the burden on mothers at the moment of birth.

In the workforce activation framing, the aim is for workplace policies that include, but also go beyond, maternity and paternity leave. For example, state or employer support for childcare facilities and preschool programs can play an important role in this model. Such policies have seen little implementation in Latin America, but the underlying rationale is finding increasing resonance in the region (such as in the case of Brazil above).

We argue that these three visions set the overall policy goals or aspirations that leaders or citizens may adopt. Subsequently, they are mediated and enacted through several political institutional and organizational factors, many of which have been previously highlighted in our brief descriptions above. In particular, we argue that as a “vanguard” policy, the adoption of paternity leave requires concerted effort by a constellation of forward-leaning actors endowed with the institutional means to design and implement policy.

A number of institutional and social factors can foster (or alternatively, diminish) the likelihood of family policy adoption. Among these, we emphasize the importance of government partisanship and female participation in national legislatures in promoting and passing both maternity and paternity leave. At the same time, we hold that such adoption is likely to be hindered when conservative actors with traditional views of the family or concerns about labor costs resist the introduction of such measures.

One of the strongest findings in the welfare state literature is the correlation between governance by left-affiliated parties or leaders and the establishment of social policies of various types (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and John2001, Reference Huber and John2012). Parties on the left typically have ideologies that emphasize social inclusion and an expansive role for the state in redistribution, so they adopt policies ranging from pensions to health care programs to educational opportunities and maternity leave (Bonoli Reference Bonoli2005; Häusermann Reference Häusermann2006; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1999; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and John2001, Reference Huber and John2012).

In Latin America, the first decade-and-a-half of the twenty-first century saw the rise of an unprecedented number of leftist governments in the region. Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela were early examples of this phenomenon (Seligson Reference Seligson2007). This trend then continued with the election of President Evo Morales in Bolivia in 2006 and President Rafael Correa in Ecuador in 2007. We expect that the ideological leanings of these governments, which emphasized inclusion and the redressing of structural inequalities, would lead them to be supportive of paternity leave, primarily as a way of ensuring that mothers would have assistance at home in the early days after childbirth and that families might embody greater gender parity.

Furthermore, given the significant powers afforded to the executive branch by Latin American constitutions, presidents are likely to be the chief actors leading the charge on expanding family policies, including paternity leave. Among these powers, executive decree, which authorizes the executive to “establish law in lieu of action by the assembly” (Carey and Shugart Reference Carey, Shugart, Carey and Shugart1998), is found in nearly two-thirds of all constitutions of modern governments in the region (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Elkins and Ginsburg2011). In fact, since in many cases the legislature and president have come from the same party, interbranch conflict has been limited, if not inconsequential, and bargaining has been mostly “horizontal” and friendly from the congress (Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Power and Rennó2005).

Religion profoundly shapes societal values and norms, as churches can either promote or inhibit progressive developments in social policy (Fink Reference Fink2009; Korpi Reference Korpi2000). Cross-national research has revealed that “conservative religious figures and right-wing politicians” have been leading advocates of the “traditional” model of childcare and maternal responsibility (Hochschild Reference Hochschild1995). Research on family leave policies in both the United States and Germany has shown that where more conservative Christian populations predominate, policy adoption is slower or results in less expansive policies (Williamson and Carnes Reference Williamson and Carnes2013).

Latin America is home to more than 425 million Catholics, and Catholics constitute a majority of the population in most countries (Hagopian Reference Hagopian2006). We hypothesize that such Catholic populations are accustomed to more traditional family structures, with male breadwinners and female family caregivers, and they will be less likely to support the extension of paternity leave policies. In the cases where they do support paternity leave, they are likely to do so with explicit reference to temporarily facilitating the mother’s transition to home as the domestic caregiver following childbirth.

Previous work has found that the share of female representatives in national legislatures is positively correlated with the passage of policies related to “women’s issues,” including more generous maternity and paternity leave policies (Kittilson Reference Kittilson2008). Recent research supports this notion, finding that in 1993 and 1994, female legislators in Argentina sponsored 21 percent more women’s rights bills and 9.5 percent more children and family bills than their male counterparts (Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006). In addition, women were more likely to make speeches on the floor on behalf of bills for women’s rights and for children and families than they were for any other type of bill in Congress.

Over the past few decades, the percentage of women in national legislatures in Latin America has rapidly risen. In 1995, only 12 percent of legislators in the region were women (Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010). Today, one in four Latin American legislators is female, and 16 countries in the region have incorporated quotas into their electoral system (Viñas Reference Viñas2014). And perhaps more important, women have been elected to the presidency in several Latin American countries. Given the importance of the presidency in policymaking in Latin America, we expect these female presidents to have outsize influence. Thus, we hypothesize that those countries that have had female presidents and that have greater numbers of women in their legislatures are more likely to be supportive of paternity leave policy adoption.

Empirical Analysis

To test these hypotheses, we make use of a newly coded dataset on the presence and duration of family leave policies across the 18 major Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela). It includes data on both maternity and paternity leave for each country-year from 1970 to 2015. Table 2 presents summary statistics for all the variables described below.

Table 2. Summary Statistics

Sources: Cited in text. Dataset covers the period 1970–2015.

For our dependent variable, we coded a variable, Paternity Coverage, which dichotomously codes whether a country has legally mandated provisions for leaves by fathers at the birth of a child. Given that most countries in the region offer only a few days, we do not believe that the number of days constitutes a meaningful difference in policies (in the way that weeks of leave for maternity policy do), so we prefer a dichotomous coding of this variable. (Alternative models using a continuous coding, although less precise in their estimations, are consistent with the results produced by the dichotomous coding.)

We also code a second dependent variable, Maternity Leave—Weeks, which captures the length of government-protected leaves for women at the birth of a child. As table 1 shows, these policies range from a low of 12 weeks to a high of 26 weeks, with many countries clustering at 12 weeks (the former ILO standard) and 14 weeks (the new ILO standard). We chose to examine the variation in weeks because every country in the region guarantees some version of maternity leave, but the duration varies significantly. Both of these variables are drawn from publications of the World Bank Group, the International Labor Organization, and the United States Social Security Administration and verified through each country’s respective constitutions and legislation.

To test our hypothesis regarding left partisanship, we employ a variable, Left President, which measures the president’s ideological orientation in each country-year (Murillo et al. Reference Murillo, Oliveros, Vaishnav, Levitsky and Roberts2011). To test our hypothesis regarding religious affiliation, we employ a variable, Catholic, which represents the percentage of the population that is nominally Catholic (Wormald Reference Wormald2014).

In addition, in all our analyses, we include several control variables. We introduce a baseline demographic control variable, Birth Rate, as a measure of latent demand for family leave policy (Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2006). In addition, given that our hypotheses largely presume a democratic context, we use the variable Polity to measure the effective level of democracy in each country on a yearly basis, as well as a count variable, Years Democratic, to indicate the length of time (since 1970) that the country has had democratic institutions (Marshall and Jaggers Reference Marshall and Keith2007). Our expectation is that a higher level of democracy and a longer time as a democracy would make a country more likely to pass legislation for family leave policy.

We include two economic control variables. GDP per Capita offers a measure of the overall economic health of the society. Where GDP per capita is higher, we expect that countries have greater capacity to provide more generous social policies to their citizens, including longer family leave policies. Trade as a Percent of GDP measures the importance of all trade in the overall economy. Greater trade exposure may make a country less likely to pass extensive family leave policies. Consistent with a “race to the bottom” hypothesis, we expect that higher values for trade as a share of GDP will be associated with less extensive and less generous family leave policies.

With regard to the impact of women in the government, other studies have found that women—especially when they serve as elected officials—play an important role in the proposal and passage of family leave legislation (Williamson and Carnes Reference Williamson and Carnes2013). To assess this impact, we include two variables. One is a dichotomous variable, Gender Quota, which indicates whether the country in question has legislated a quota for women’s seats in the national congress. Our expectation is that where quotas are in force, women legislators are more likely to move family leave legislation effectively through the approval process. The second is another dichotomous variable, Female Leader. This variable indicates whether the president in any given year is a woman; we expect that women serving in the highest office may be more likely to pass family leave legislation.

Table 3 presents logit models for the presence of paternity leave coverage. Model 1 presents a simple model testing our key hypotheses. Having a president from the political left is positively and statistically significantly correlated with paternity coverage. The coefficient for Catholic population shows a significant negative relationship with paternity coverage; it would seem that the Catholic vision of the family privileges the father’s continued presence in the workplace, and therefore does not seek to guarantee time off from work at the birth of a child (and indeed may even actively oppose it). Furthermore, the birth rate variable has a positive (but not statistically significant) coefficient.

Table 3. Determinants of Paternity Leave Coverage

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

Logit models. Standard errors in parentheses

Models 2 and 3 add the political and economic controls. Level of democracy does not have a significant effect, but years democratic has a positive, significant coefficient. In other words, a longer history of democracy is correlated with greater likelihood of paternity coverage. Likewise, richer countries have a greater likelihood of having paternity coverage, as the coefficient for GDP per capita is positive and significant. And trade as a share of GDP has a negative, significant coefficient, implying that the competitive pressures of trade may keep countries from adopting potentially costly paternity policies. (Our variables for gender—the presence of a gender quota and of a female president—are omitted because they perfectly predict the presence of paternity policy.)

These findings help us understand the factors that have facilitated the recent adoption or extension of paternity leave in the region in countries such as Uruguay and Venezuela, where longstanding leadership from the left made them ripe for the adoption of policies emphasizing gender parity and full labor market activation for women. Likewise, they illustrate that traditional conservative forces, represented here through the Catholic population share, could act as a counterbalance, opposing paternity leave policy adoption, as occurred in Mexico. We see this as important evidence of the critical role competing policy visions play in the adoption of, or opposition to, newly emerging policies, such as paternity leave. Having a champion in the country’s executive and a supportive ideological framework, both intellectual and practical, can build support among the population and policymakers, or can, alternatively, create roadblocks that limit or recharacterize the policy.

In addition, the findings show the important role that longer-established democratic contexts, where citizen participation is more robust, and the action of committed social groups can play in the adoption of novel policies that depart from previous norms. Indeed, activism and thought leadership by women played a critical role in the adoption of paternity leave policies in Bolivia, Chile, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Where this influence was weaker or where women made up a smaller share of the legislature, policy initiatives were less successful, as in Brazil and Peru. Does maternity leave follow these same patterns? We have argued that the more mature policy measures, such as maternity leave, might have different political dynamics, and that they might complement the passage of paternity leave policies. For example, countries that were early adopters of paternity leave may also have been early adopters of maternity leave (decades earlier), but they may not see the need for reform now, given their already advanced status. Relatedly, the recent focus on innovation through paternity leave may crowd out discussion of maternity leave reform or expansion.

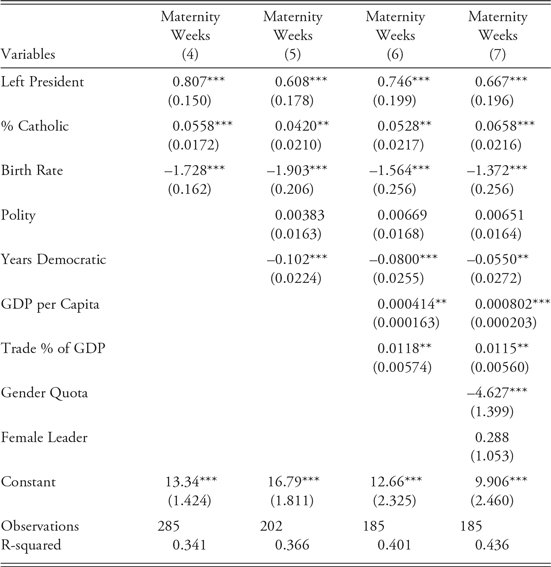

Table 4 presents OLS models for maternity leave policies, measured in terms of weeks of benefits. Model 4 is our simple model, and it is clear that the factors shaping maternity policy expansion do indeed function differently from paternity leave adoption. Nevertheless, the model shows that having a president from the political left is positively and significantly correlated with longer maternity leaves, as expected and as occurred for paternity leave adoption.

Table 4. Determinants of Maternity Leave Duration

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

OLS models. Standard errors in parentheses

Somewhat surprisingly, however, the share of the population that is Catholic also has a positive and statistically significant relationship with the length of maternity leaves. This may reflect a pronatalist bias in Catholic beliefs. It also may show that conservative forces see maternity leave as preferable to paternity leave in promoting traditional family divisions of labor. The birth rate, however, shows a negative relationship. This is also somewhat puzzling, but we will see that it is replicated in all our models. We believe that this may occur because maternity leave policies were adopted, for the most part, in the middle of the twentieth century. Therefore, the variation we observe now represents the reform—and not origins or design—of the policies. Thus, countries that adopted generous policies early on are now in the process of making only marginal changes to them. Additionally, birth rates in general have been in decline for the last several decades.

Model 5 adds political controls to the equation, and the results are unchanged for our variables of interest. Of the additional variables, only Years Democratic reaches statistical significance; its negative coefficient seems to indicate that longer periods of democracy are negatively associated with lengthy maternity leaves. This may occur because many of these policies were adopted before the return of democracy and have changed only slightly in the years since. Likewise, it could be that public opinion is directed toward paternity leave adoption rather than maternity leave expansion. Indeed, this would reflect an emphasis on the gender parity rather than gender complementarity vision.

Model 6 adds our economic controls, and here both variables, GDP per Capita and Trade as a share of GDP, have positive and statistically significant effects. Richer countries have more expansive policies, and that exposure to trade raises the duration of family leaves, a finding consistent with some earlier work (Mosley et al. Reference Mosley, Harrigan and Toye1991). Furthermore, our addition of gender controls in model 7 shows a negative and significant effect for the gender quota. This could mean that gender quotas are implemented where they are most needed—where women’s voices are weakest— and that they have not yet had an effect on increasing maternity leave. Likewise, having a female president does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. These findings regarding gender—as well as those of birth rate highlighted above—may reflect the still-unsettled vision of the family in many of these societies. As highlighted by Blofield, a tension exists between maternalism and coresponsibility in many countries, and women as well as men may not have unified around a single vision (as they have, for example, in Brazil and Peru). If this is the case, we might see the gender quota having the negative effect we observe here.

Taken together, these results suggest that the dynamics governing the adoption of paternity leave are significantly different from those that shaped maternity leave length. For paternity leave, a vanguard policy that advances a new vision of gender parity and labor market activation, the support of a president from the left is crucial, as is a longer experience of democratic governance. Having a larger Catholic population and a more trade-dependent economy coincides with a lower likelihood of adopting paternity leave policies. Maternity leave, with its longer history, seems to behave in a way consistent with its status as a “mature” policy, with the results we see here reflecting reforms to a base established in the middle of the twentieth century. Indeed, the further expansion of maternity leave might be seen as advancing an outmoded, conservative vision of gender complementarity that is espoused by a decreasing share of the population.

Conclusions

This article has examined the political dynamics shaping the adoption of family leave policies in Latin America, and it has given special attention to the new, “vanguard” policies of paternity leave. By examining the early adopters, it has inductively discerned three patterns or visions of family policy emerging in the region. And the empirical analysis shows that similar sets of political factors are highly correlated with the generosity of both maternity and paternity leave, but that these function in different ways as they advance differing policy visions.

Having a president from the political left and more years of democracy show a robust relationship with the adoption of more generous paternity leave policies, while a larger Catholic population and greater international trade serve as constraints on this policy expansion. With regard to maternity leave expansion, though, political will seems to be more attenuated and reforms less frequent, with most energy focused instead on paternity leave changes—though modest in their duration—that reflect perceived greater gender parity.

A few words of caution are in order about this last point, though. First, maternity leave policies are heavily conditioned by the “focal point” policies promoted by the International Labor Organization (ILO). This means that levels of maternity leave may be censored at the high end, in the sense that countries cap their offerings at the focal, ILO-promoted level. Thus, some countries could feasibly have increased the lengths of their maternity leaves further, especially given their political dynamics and emerging visions of family life, but the existence of ILO standards served as a brake on these efforts.

In contrast, paternity leave is a policy area evolving in real time. Standards have not yet been set, either regionally or globally, so countries are experimenting with new measures that will surely develop further in the future, and the public response to these policies remains uncertain. Indeed, the experience of European countries has shown that males have been less likely to make use of the full leaves provided them by law. As a result, both businesses and workers may not yet have fully formed opinions about paternity leave policies beyond their immediate, direct cost in productive days of work foregone. The results here may need to be reexamined as these policies become more politically contentious.

Nevertheless, our findings suggest that there is both interest in, and significant expansion of, cutting-edge paternity leave policies in Latin America in recent years. The political dynamics that shape the adoption of these paternity policies are familiar, dovetailing well with our understanding of early welfare state developments, yet their evolution seems to be on a trajectory distinct from that of current maternity policies. Given this divergence, untangling the new dynamics of family leave policy across gender lines promises to be an important and fruitful area for continued future research.

Supporting Information

For replication data, see the author’s file on the Harvard dataverse website: http://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/laps