Starting with the Maya Long Count date 9.19.0.0.0 (AD 810) and continuing until at least 10.4.0.0.0 (AD 909), an era commonly described as the Terminal Classic period, there was severe political disruption across the Southern Maya Lowlands (Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, Rice and Rice2004; Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Prufer, Macri, Winterhalder and Kennett2014; Munson and Macri Reference Munson and Macri2009). The recent discovery of a Terminal Classic monument, Stela 29, at the archaeological site of Ucanal, in Peten, Guatemala, enlarges a relatively small corpus of carved records dating to this era (see Figures 1 and 2). The monument conforms to a new political order in which a limited number of upstart polities in Peten began to express political identities and statements of self that differed from those that traditionally marked Classic Maya culture. The meaning of these changes and their relationship to internal and external political developments have long been topics of debate.

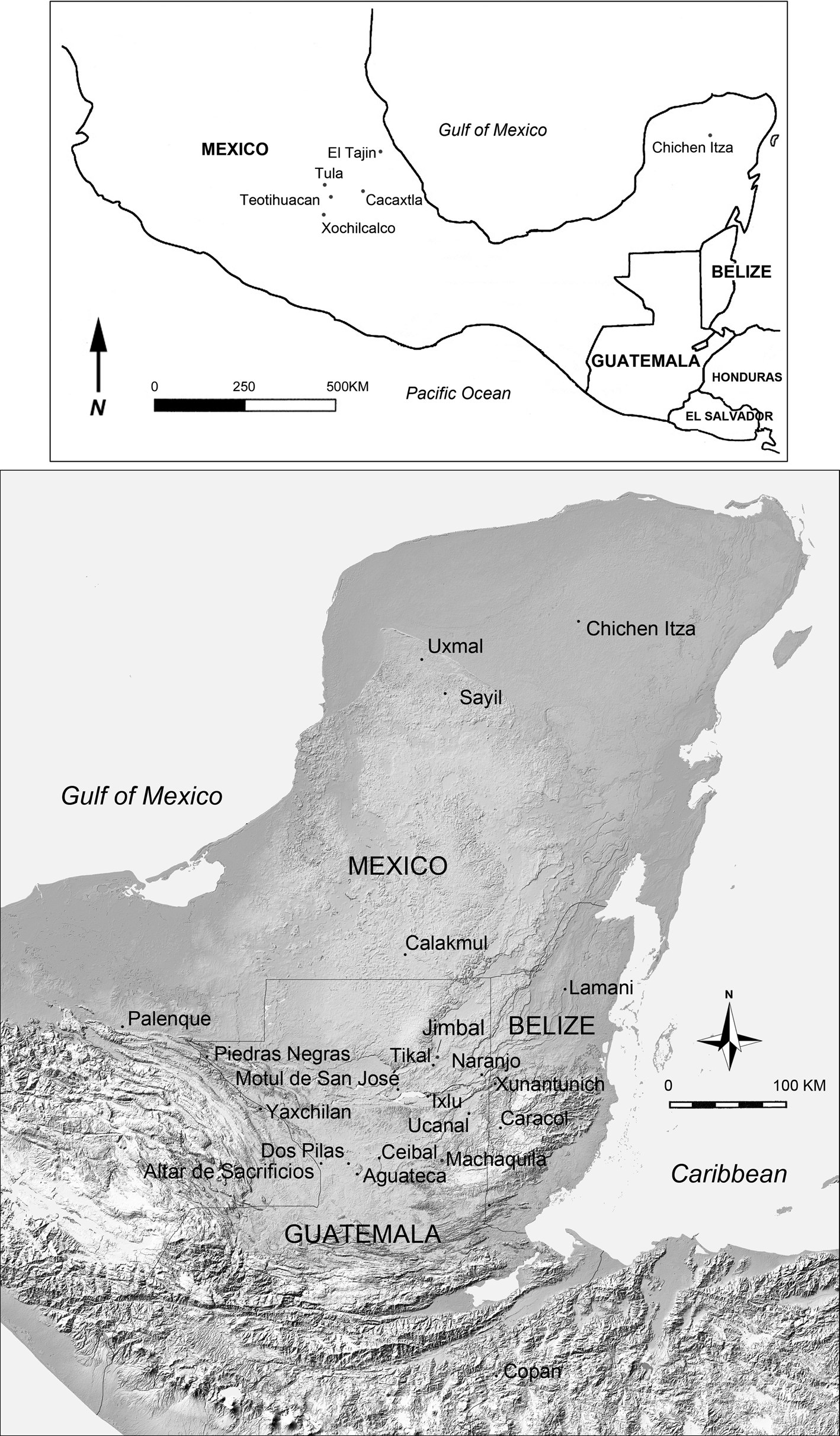

Figure 1. Map of Mesoamerica (top) and the Maya area (below) with sites mentioned in the text.

Although there are different ways in which this new order could have come about, in this article we explore this question through the paradigm of “cosmopolitanism.” This approach posits that, rather than representing a wholesale emulation of a single foreign power or entity, monuments like Ucanal Stela 29 were formed out of an internationalist aesthetic that rooted local expressions of authority within a broader Mesoamerican cultural milieu. Such an aesthetic, in turn, provokes questions about the modes of transmission that linked this site to others throughout Mesoamerica. The necessarily vague notion of “influence” needs to be accompanied by a model of how ideas travel through space and time.

Monumental Art and Cosmopolitanism in the Ninth Century

Explorations of ancient cosmopolitanism are less about articulating a moral philosophy or a Western elite ideal for universal individual rights (Appiah Reference Appiah2007; Wallace Brown and Held Reference Wallace Brown and Held2010) than an examination of the ways in which social groups accommodated, depended on, conflicted with, and creatively incorporated peoples and influences across polity, ethnic, and cultural boundaries (Cobb Reference Cobb2019; Halperin Reference Halperin2017a; Kaur Reference Kaur2011; Richard Reference Richard2013). These entanglements ultimately created new senses of identity and belonging.

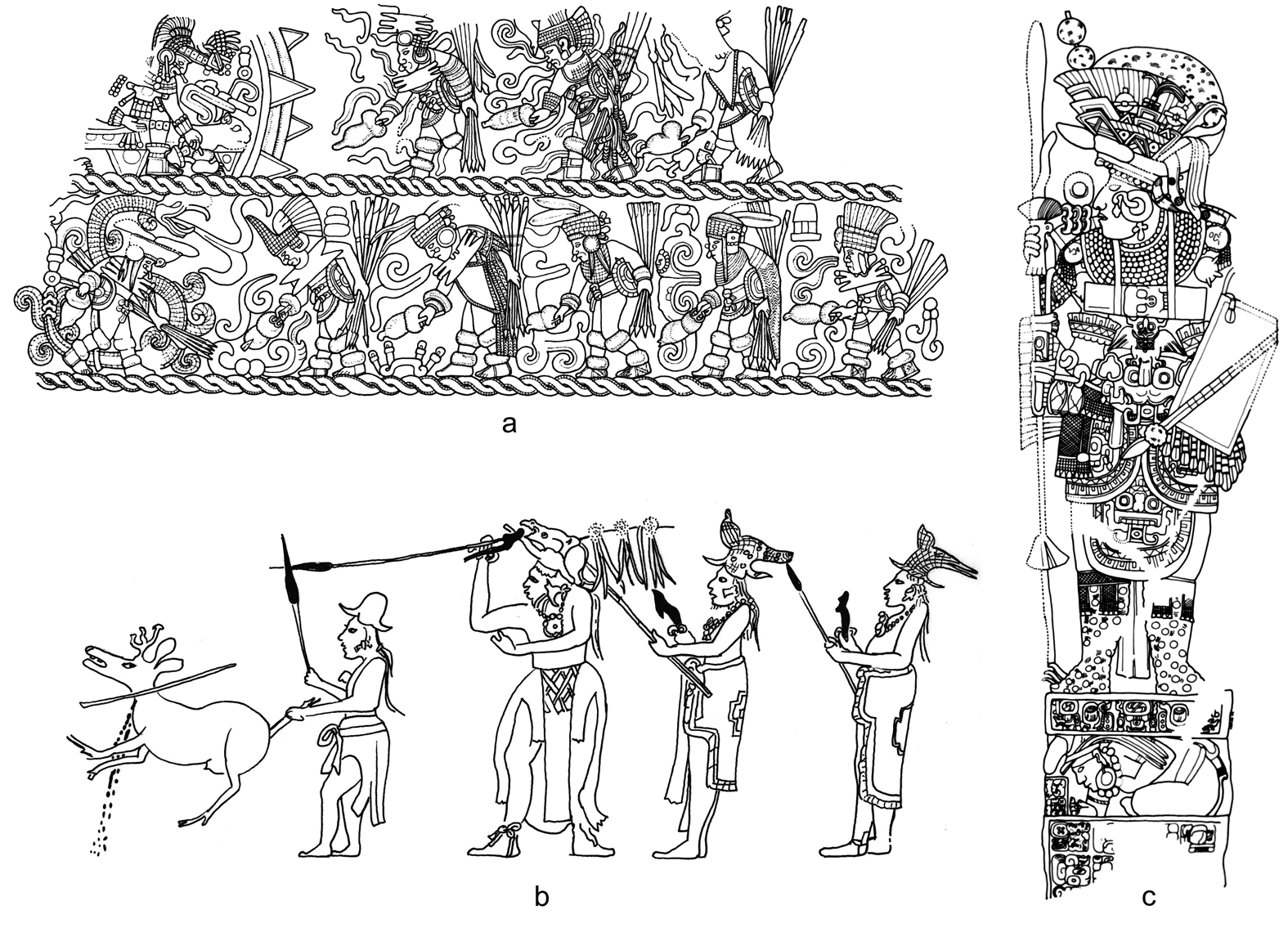

Early interpretations of ninth-century monuments from the Maya Lowlands proposed that Classic centers collapsed as a result of an invasion of “Mexicanized” peoples who took over sites such as Ceibal, Altar de Sacrificios, and Ucanal, bringing with them iconographic innovations and fine paste pottery from the west (Adams Reference Adams and Patrick Culbert1973; Sabloff and Willey Reference Sabloff and Willey1967). For J. Eric S. Thompson, these intruders were Putun Maya, a “hybrid Maya-Nahuat” people from the Gulf Coast of Mexico, who could be identified by their “foreign” traits, such as warrior figures holding darts and atlatls seen floating within beaded scrolls and the use of square-framed glyphs holding Central Mexican day signs (Thompson Reference Thompson1970:3–44). As he pointed out, both of these features appear together on Ucanal Stela 4 from AD 849 (see Figure 3b). It has the “Mexican”-style floating warrior of a type also seen at Ixlu (Stela 1, 2), as well as square day signs within its two royal names, a feature shared with Terminal Classic monuments at Jimbal (Stela 1, 2), Ceibal (Stelae 3, 13), and Calakmul (Stela 86; see Justeson et al. Reference Justeson, Norman, Campbell and Kaufman1985:53–54; Lacadena Reference Lacadena, Vail and Hernández2010:385–389; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:153). More of these day signs are seen on molded-carved fine paste pottery, where they act as names identifying warriors dressed in non-Maya garb.

Yet there is a greater appreciation today that identity markers of these kinds are not necessarily rigidly ascribed to people, geography, or cultural settings. They can instead become an ideological currency or language that can be transferred, appropriated, or emulated by others. The very definition of Mesoamerica is one that sees it as a zone of cultural, intellectual, and material exchange—one in which different ethnocultural and linguistic groups were long in dialogue with one another. Interest in these processes in recent years has steadily shifted emphasis from the idea of military action and toward more complex and nonaggressive contacts. Today a consensus has emerged that foreign artistic or written conventions do not necessarily reflect the presence of foreign peoples or political authorities in any straightforward one-to-one fashion (Nagao Reference Nagao, Diehl and Berlo1989; Stuart Reference Stuart, Sabloff and Henderson1993; Tourtellot and González Reference Tourtellot, González, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004).

Instead, the proposal is that decentralized political networking, pilgrimages, economic exchanges, and information sharing, in addition to warfare, sparked a cosmopolitan milieu of eclectic borrowing during the ninth century (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham Reference Kowalski and Kristan-Graham2011; López Austin and Luján Reference López Austin, Luján, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000; Nagao Reference Nagao, Diehl and Berlo1989; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Negrón and Bey1998). After the fall of Teotihuacan at the end of the Early Classic period (ca. AD 550–600), political centers such as Cacaxtla-Xochitécatl, Xochicalco, Tula, El Tajin, Cerro de las Mesas, and Chichen Itza flourished but did not draw inspiration from a single, dominant power. Rather, they were influenced by, shared ritual practices with, and combined visual repertoires from multiple distant regions that merged local senses of identity within a larger cultural world (Brittenham Reference Brittenham2015; Carter Reference Carter2014; Kowalski and Kristan-Graham Reference Kowalski and Kristan-Graham2011; Nagao Reference Nagao, Diehl and Berlo1989; Testard Reference Testard2018). As such, many recent formulations of Epiclassic (ca. AD 600–900) art and architecture align with what social thinkers and philosophers call “situated,” “rooted,” or “vernacular” cosmopolitanism, whereby worldly dispositions, values, and identities are held in tension with local and more personalized practices and experiences. For example, “rooted cosmopolitanism” underscores that one can simultaneously have roots and wings, because alignment with the values and rights of world citizenry are both informed and understood through situated local identities (Appiah Reference Appiah2007; Beck Reference Beck2002), and “vernacular cosmopolitanism” emphasizes that the ethics of coexistence and broader universal connections emerge in and through local vernaculars and ways of being (Bhabha Reference Bhabha, García-Moreno and Pfeiffer1996; Pollack Reference Pollack, Breckenridge, Pollack, Bhabha and Chakrabarty2002). For precolumbian Mesoamericans, such connections were not about global citizenship but likely focused on the positioning of themselves or their community within a broader discourse of social values, religious mores, and political practices that could be manifested in different ways by different peoples, status groups, genders, and the like (Halperin Reference Halperin2017a).

Because many of the powerful Classic period centers from the Southern Maya Lowlands had stopped erecting monuments by the ninth century, this region is sometimes seen as peripheral to the developments in the Northern Maya Lowlands, Gulf Coast, or Central Mexican regions (Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Negrón and Bey1998). Postcolonial reworkings of ideas of cosmopolitanism, however, emphasize that it can emerge from the peripheries as much as from the centers of global powers (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1994, Reference Bhabha, García-Moreno and Pfeiffer1996). Indeed, the monumental visual repertoires of upstart Terminal Classic centers from the Southern Maya Lowlands, such as Ceibal, Machaquilá, Jimbal, and Ucanal, were active in asserting their outward ties during this time while also making use of more localized artistic norms. Bryan Just (Reference Just2006), for example, has characterized the visual discourses of ninth-century monuments from Ceibal in terms of linguistic heteroglossia. Reflecting the coexistence of multiple languages and points of view within a single community, Ceibal's ninth-century monumental program incorporated, often within the same monument, multiple visual convention systems from the Gulf Coast, Chichen Itza, and the “Classic” Lowlands. Such eclecticism, he argued, may have been promoted to address an increasingly diverse audience or the international connections of the Ceibal kings. Likewise, the newly discovered Terminal Classic Stela 29 from Ucanal eclectically incorporated elements and stylistic conventions from both near and far.

The Monumental Corpus from Ucanal

Since the earliest documentation of monuments at Ucanal—a site identified epigraphically as K'anwitznal (“Yellow Hill Place”) in Classic period texts—scholars have recognized the presence of important monuments dating to the Terminal Classic period.Footnote 1 For example, fieldnotes by Raymond Merwin and C. W. Bishop from the eleventh Peabody Museum Expedition in 1914 and detailed in a publication by Sylvanus Morley (Reference Morley1938:2:186–201) recorded six sculpted (Stela 1–6) and 11 uncarved stelae. Merwin and Bishop suggested that these monuments spanned the Late and Terminal Classic periods from 9.18.0.0.0 to 10.1.0.0.0, although Morley (Reference Morley1938:2:190–191, 200) emphasized that such a statement could not be made with precision because they had not provided drawings of all the stelae, most notably Stela 1 and 5. Today, these monuments are so heavily eroded that no inscriptions are visible. Nonetheless, Morley stressed the importance of Stela 4, mentioned earlier, because its date at 10.1.0.0.0 (AD 849) was secure, placing it among the few monuments then documented for this late period of time (see Figure 3b).

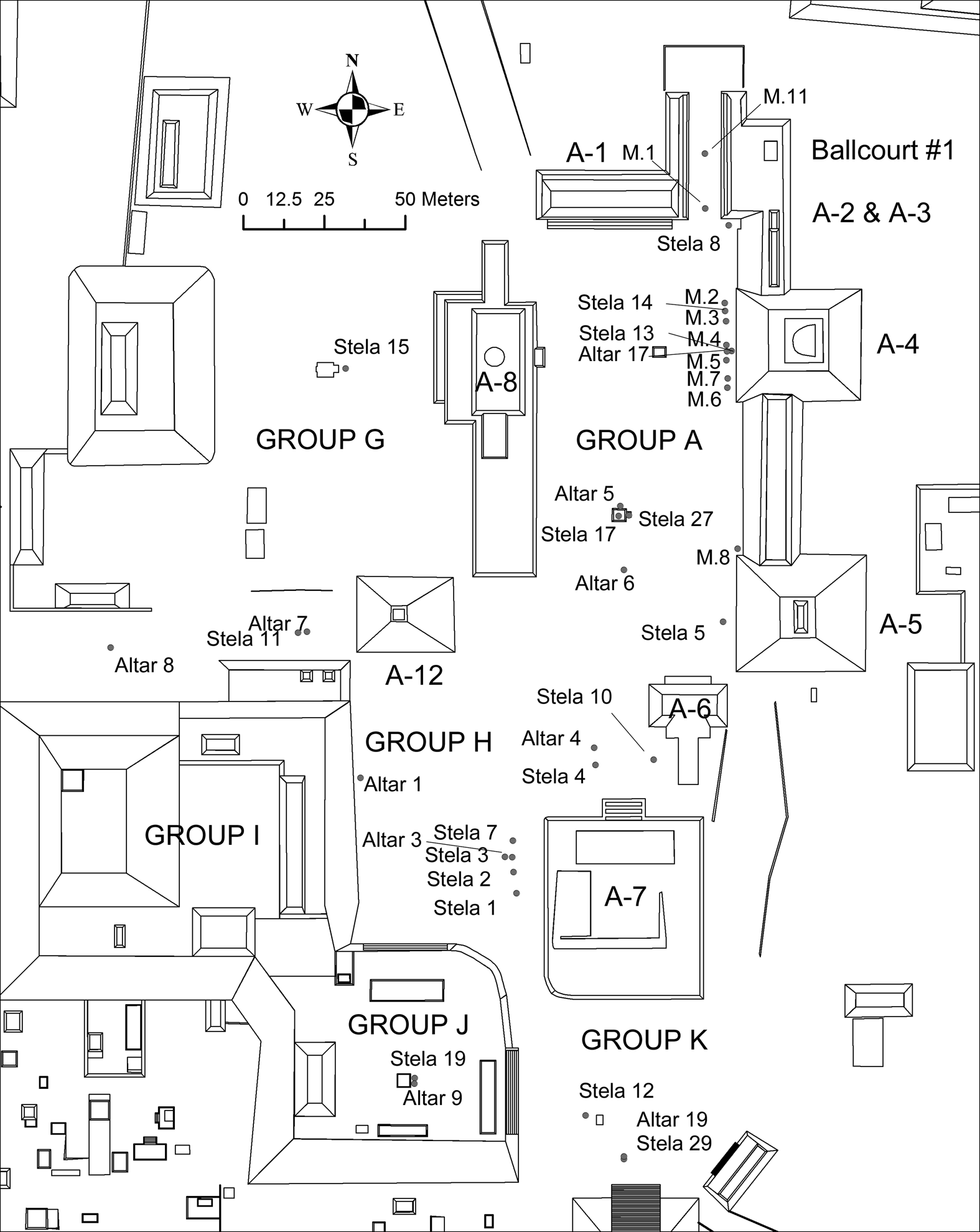

In 1972, Ian Graham visited the site and provided photographs and drawings of Stela 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 and Altars 1 and 3 (Graham Reference Graham1980). Of particular significance was his finding of Miscellaneous Monument 1, a rectangular block with a carved cartouche containing well-preserved hieroglyphs. He recognized it as being from the same monumental program as Naranjo's Hieroglyphic Stairway, assigning it the additional designation of Step XIII in that program (Graham Reference Graham1978:107, 110). Ucanal Miscellaneous Monument 1 was located 5 cm below the ground surface in the center line of Ballcourt #1 at the northern side of Plaza A (note: its location on the map [Figure 1] is approximate). Subsequent excavations of the ballcourt (see Halperin, Cruz Gómez, et al. Reference Halperin, Gómez, Radenne, Bigué, Halperin and Garrido2020; Laporte and Mejía Reference Laporte and Mejía2002a) revealed that its construction dates to the Terminal Classic period, indicating that the monument's placement in the ballcourt was done during this time period or afterward. This monument provides a rare example of the transport of monumental blocks from one site to another. Although Graham had suggested that the Ucanal block was transported from Naranjo to Ucanal, later research indicated that it was once part of a seventh-century monumental program at the site of Caracol, a hieroglyphic stairway that had been dismantled, with its parts seemingly removed as war trophies (Martin Reference Martin, Colas, Delvendahl and Schubart2000, Reference Martin2017). This reuse of monuments involved not only Naranjo and Ucanal but also Xunantunich, where two additional blocks from this stairway were recovered in 2016 (Helmke and Awe Reference Helmke and Awe2016a, Reference Helmke and Awe2016b).

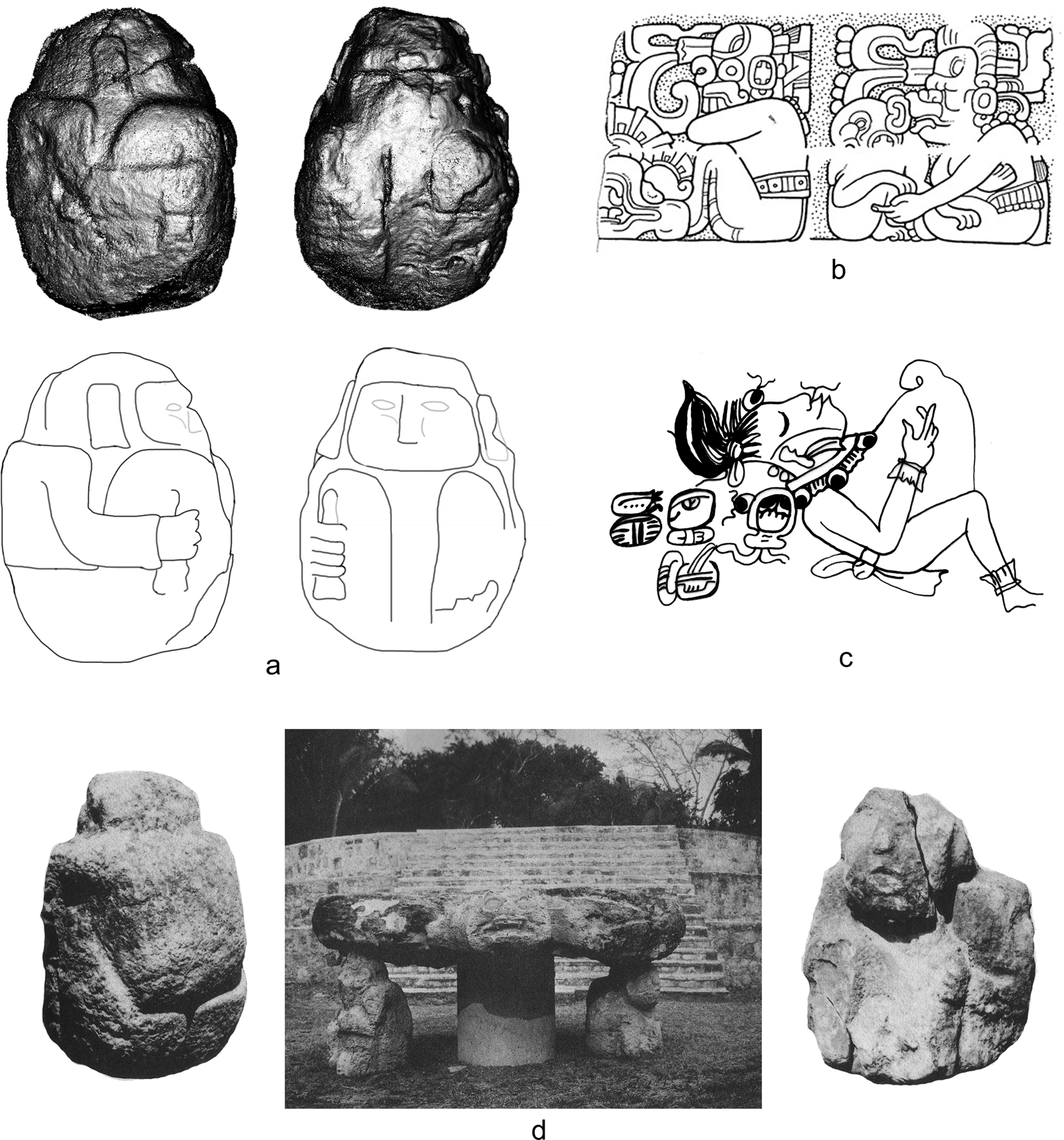

Investigations in the late 1990s and early 2000s by the Proyecto Atlas Arqueológico de Guatemala, directed by Juan Pedro Laporte, revealed that the site of Ucanal dates from the Middle Preclassic period to the Postclassic period, with the densest occupation and building activity occurring during the Late Classic and Terminal Classic periods (Corzo et al. Reference Corzo, Alvarado, Laporte, Laporte and E.1998; Laporte and Mejía Reference Laporte and Mejía2002a, Reference Laporte, Mejía, Laporte, Escobedo E. and Arroyo2002b; Laporte et al. Reference Laporte, Mejía, Acuña, Alvarado, Alvarez and Arroyave2002). The Atlas Project identified a significant number of additional monuments, the majority of which were either uncarved or too eroded to make out glyphic inscriptions or iconography (Altars 5–18, Monuments 2–8, Stelae 8–26; some uncarved stela were identified by Merwin and Bishop but renumbered by the Atlas project).Footnote 2 Nonetheless, some of the monuments were identified during excavations, providing secure dates for their erection (or re-erection) in their in situ locations of discovery. Most notably, uncarved Stela 13 and its associated Altar 17, Stela 14, and Monuments 2–7 were dated to the Terminal Classic period based on their context in the Terminal Classic stela platforms and plaza foundation just in front of Structure A-4, a pyramidal building with a semicircular temple (see Figure 2; Halperin and Garrido Reference Halperin and Garrido2019:52–53, Figure 4; Laporte and Mejia Reference Laporte and Mejía2002a:8–9). Interestingly, all of the six monuments (Monuments 2–7) are noted to have been carved in the round and identified as figures in a squatting position with knees in front of the chest. Together they form three pairs of squatting figures, each between 0.9 and 0.5 m in height, with Monuments 2 and 3 on either side of Stela 14, Monuments 4 and 5 on either side of Altar 17/Stela 13, and Monuments 6 and 7 as a pair to the south, perhaps on either side of a monument no longer present at the site (see Figures 4a and 5a).Footnote 3

Figure 2. Map of the H-10 sector of Ucanal showing the location of Stela 29 in Group K and other monuments.

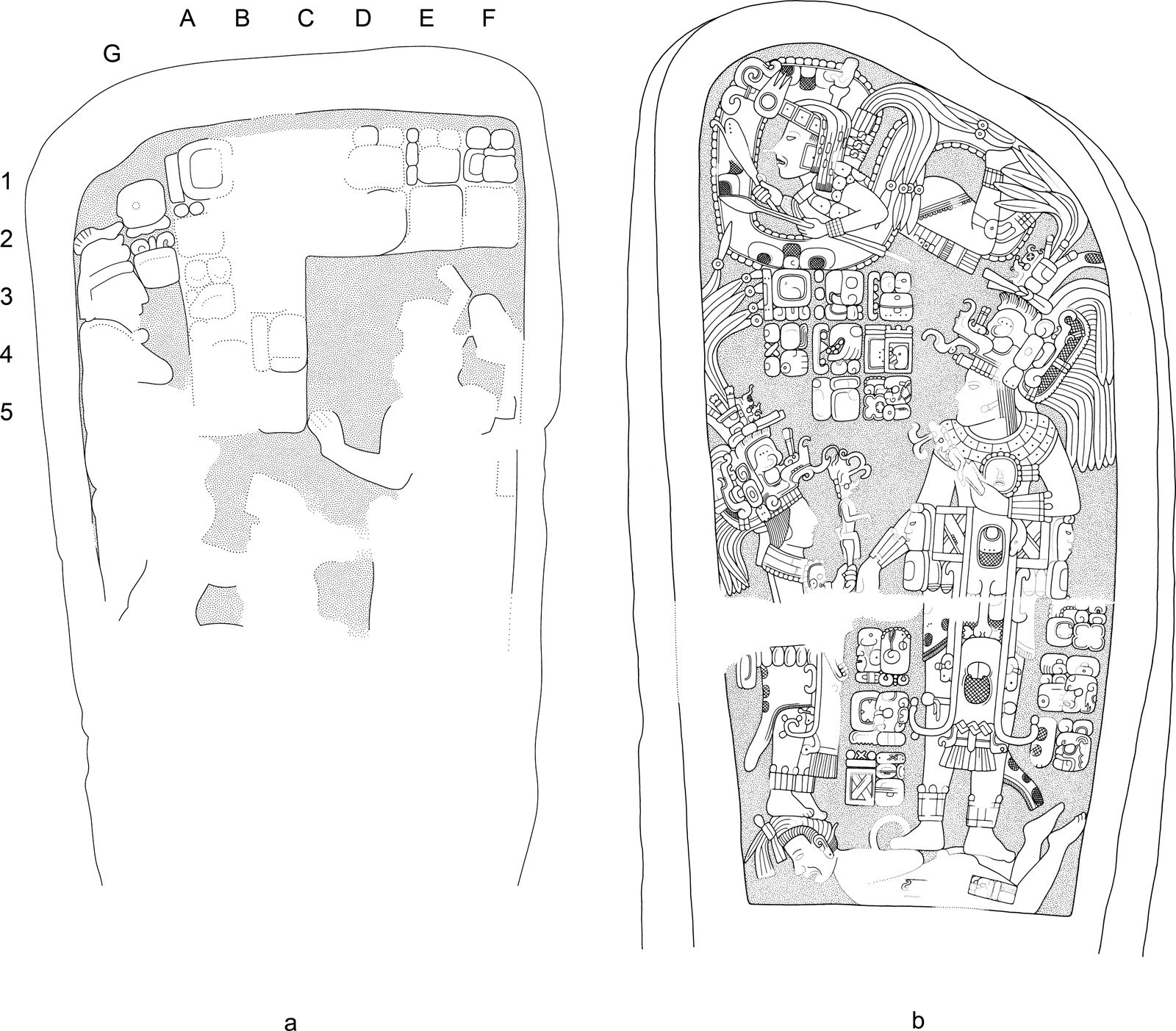

Figure 3. Terminal Classic stelae from Ucanal: (a) Stela 10 (drawing by S. Martin after photogrammetry photos by C. Halperin and M. Radenne; dimensions 2.13 × 0.95 × 0.35 m); (b) Stela 4 (drawing by I. Graham; courtesy of the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Peabody Museum, Harvard University; dimensions 1.90 × 1.00 × 0.53 m).

Figure 4. Squatting and fat figures: (a) squatting, fat figure with cloth ear pendants, Ucanal Monument 7 (dimensions 85 × 65 × 65 cm; photogrammetry by J-B. LeMoine & drawing by C. Halperin); (b) squatting Teotihuacan deity paired with cross-legged Maya K'awiil, Copan Structure 10L-26-1st (after Stuart Reference Stuart, Andrews and Fash2005:Figure 10.6a); (c) sitz’ winik way with cloth ear pendants (Fat Man spirit companion), detail from polychrome vessel, K927, drawing by C. Halperin); (d) paired squatting figures, Ceibal Altar 1, in front of circular Terminal Classic Structure 79 (after Willey Reference Willey1982: Figure 140).

Figure 5. Terminal Classic simian imagery: (a) Ucanal Monument 3 (dimensions 80 × 50 cm; photogrammetry reconstruction by J-B. LeMoine); (b) Fine Orange squatting monkey figurine from Altar de Sacrificios (after Willey Reference Willey1972:Figure11a); (c) simian figure from stucco facade of Ceibal Structure A-3 (photograph by C. Halperin). (Color online)

Although some of the monuments were extremely eroded and were not drawn, our analysis of the Atlas project descriptions and of the two monuments (Monuments 3 and 7) currently available for study indicate that these figures fall outside the Classic period norms of monumental conventions and highlight themes of liminality, foreignness, and the transgressive. In particular, the squatting position of these figures is decidedly uncharacteristic of Lowland Maya peoples. Although this position is acceptable for some animals and supernaturals, such as death gods, human seated figures in Maya art are usually portrayed cross-legged or, less commonly, kneeling. As Andrew Scherer and colleagues (Reference Scherer, Golden, Houston, Willermet and Cucina2018:174–179) point out, however, when squatting figures with knees bent in front of the chest are portrayed in Classic Maya art, they are always portrayed as foreigners. One excellent example of such contrasting behavioral affinities is the text from Copan's Structure 10L-26-1st, whose full-figure glyphs of Central Mexican deities are depicted squatting. These full-figure glyphs stand out from those of Maya deities and elites in the same text who sit in typical cross-legged fashion (see Figure 4b; Stuart Reference Stuart, Andrews and Fash2005:387–390).

Ucanal Monument 2 appears to represent a fat squatting figure in the round (0.55 × 0.55 m), whereas Monument 3 is slightly taller at 0.8 × 0.50 m and has his male genitals exposed (see Figure 5a). Although Monument 3's face appears to have been purposefully removed, it likely represents a monkey. Monkeys, jaguars, and captives are some of the few figures in Maya imagery that transgress conventional norms of depiction in exposing their genitals, thereby emphasizing their liminal status (see Figure 5b; Benson Reference Benson, Robertson and Fields1994; Halperin Reference Halperin2014:94–142). In addition, Monument 6, which has the same spatial proportion (0.95 × 0.60 m) and form as Monument 3, also represents a monkey (Laporte and Mejia Reference Laporte and Mejía2002a:31). Monument 7 (see Figure 4a), which is paired with Monument 6, represents a round, fat squatting figure similar in proportion to Monument 2. Rather than the typical ear spool, the figure dons cloth ear pendants, adornment worn by captives, monkeys, trickster figures, spirit companions, and ritual clowns—most notably the Fat Man, who had the capacity to imitate and make fun of royal mores (Halperin Reference Halperin2014:94–144; Taube Reference Taube, Hanks and Rice1989). In turn, corpulence, as seen in Monument 2 and likely in Monuments 4, 5, and 6, is also a characteristic of Fat Men (see Figure 4c), dwarves, ritual clowns, spirit companions, and other trickster figures whose potbellies and bulging cheeks strayed from Classic Maya ideals of beauty, which emphasized slim and evenly proportioned bodies.

Ritual clowns, spirit companions, monkeys, death gods, and other trickster figures were rarely, with the exception of dwarves, depicted on Classic Maya monuments in the Southern Maya Lowlands. Rather, they appear primarily in smaller-scale and more informal media, such as polychrome pottery and figurines, where social commentary and more varied visual narratives were tolerated (Halperin Reference Halperin2014). Nonetheless, these norms started to break down in the Terminal Classic period, as seen in these examples from Ucanal, as well as two very similar paired squatting figures associated with Ceibal Altar 1, located in front of a Terminal Classic circular structure, Structure 79 (see Figure 4d). Monkey-like figures and other zoomorphic beings also appear on the painted stucco frieze on Terminal Classic Structure A-3 (see Figure 5c; Willey Reference Willey1982:30–51, Figure 140). Such openness in monumental depictions of these types of figures was also apparent during this time at sites along the west coast of the Northern Maya Lowlands where the Fat Man appears on large carved columns (Miller Reference Miller and Benson1985:Figures 14 and 15).

In addition to these monuments, another Terminal Classic stela, Stela 10, was reported by the Proyecto Atlas Arqueológico, although it did not publish a drawing or photo. Karl H. Mayer (Reference Mayer2006) visited the site of Ucanal in 1996 and 2004 and did publish a photograph of this monument. Our more recent documentation of this highly eroded stela used photogrammetry for light manipulation as the base material for a new drawing. This stela shows a ruler on its right side, who may be enthroned, with an outstretched arm, facing one or two captives and a standing lieutenant at the far left (see Figure 3a). Examination of the text shows an opening tzolk'in day at A1 with a coefficient of “5” and a haab month at A2 that has a probable coefficient of “3” (the B1 position would be filled with a combined G-F glyph in this case). Given these values, the most likely date would be the Calendar Round 5 Ajaw 3 K'ayab, corresponding to the major period ending 10.1.0.0.0 (AD 849), which is the same date found on Stela 4. Stelae 4 and 10 were originally placed on opposite sides of the stairway leading down from Structure A-7—and in this sense formed a pair (see Figure 2). The only other glyph on Stela 10 that seems to be readable is the one at F1, which could well be a version of the Ucanal emblem glyph K'uhul K'anwitznal Ajaw (“Holy Yellow Hill Place Lord”). The two-glyph caption to the standing lieutenant features one other candidate for a legible sign, potentially concluding with the noble title ti'huun. In sum, Stela 4 and Stela 10 were probably dedicated together in AD 849 and celebrated the same ruler. Even though Stela 10 is much deteriorated today, its surviving details suggest that it was an inferior carving compared to the finely hewn Stela 4.

More recent archaeological research at the site by the Proyecto Arqueológico Ucanal (PAU; 2014, 2016–2019) directed by Christina Halperin and Jose Luis Garrido has revealed that the site of Ucanal was much more urban than previously considered: it has a core zone of at least 7.5 km2 of continuous settlement and a wider periphery that extends at least to a zone of 26 km2 (Halperin and Garrido Reference Halperin and Garrido2019; Halperin and Garrido, ed. Reference Halperin and Garrido2016, Reference Halperin and Garrido2018, Reference Halperin and Garrido2019, Reference Halperin and Garrido2020). Excavations in the residential and monumental zones of the city confirm earlier findings by the Proyecto Atlas that the site was most heavily occupied during the Late Classic and Terminal Classic periods, with its population either remaining stable or increasing slightly during the Terminal Classic period. To date, the PAU has identified six new monuments (carved Stela 27–29 and uncarved Stela 30–32), two altars (Altars 19, 20), three miscellaneous monuments, and an unfinished altar (Halperin Reference Halperin, Halperin and Garrido2020). The most complete and best preserved of these monuments is Stela 29.

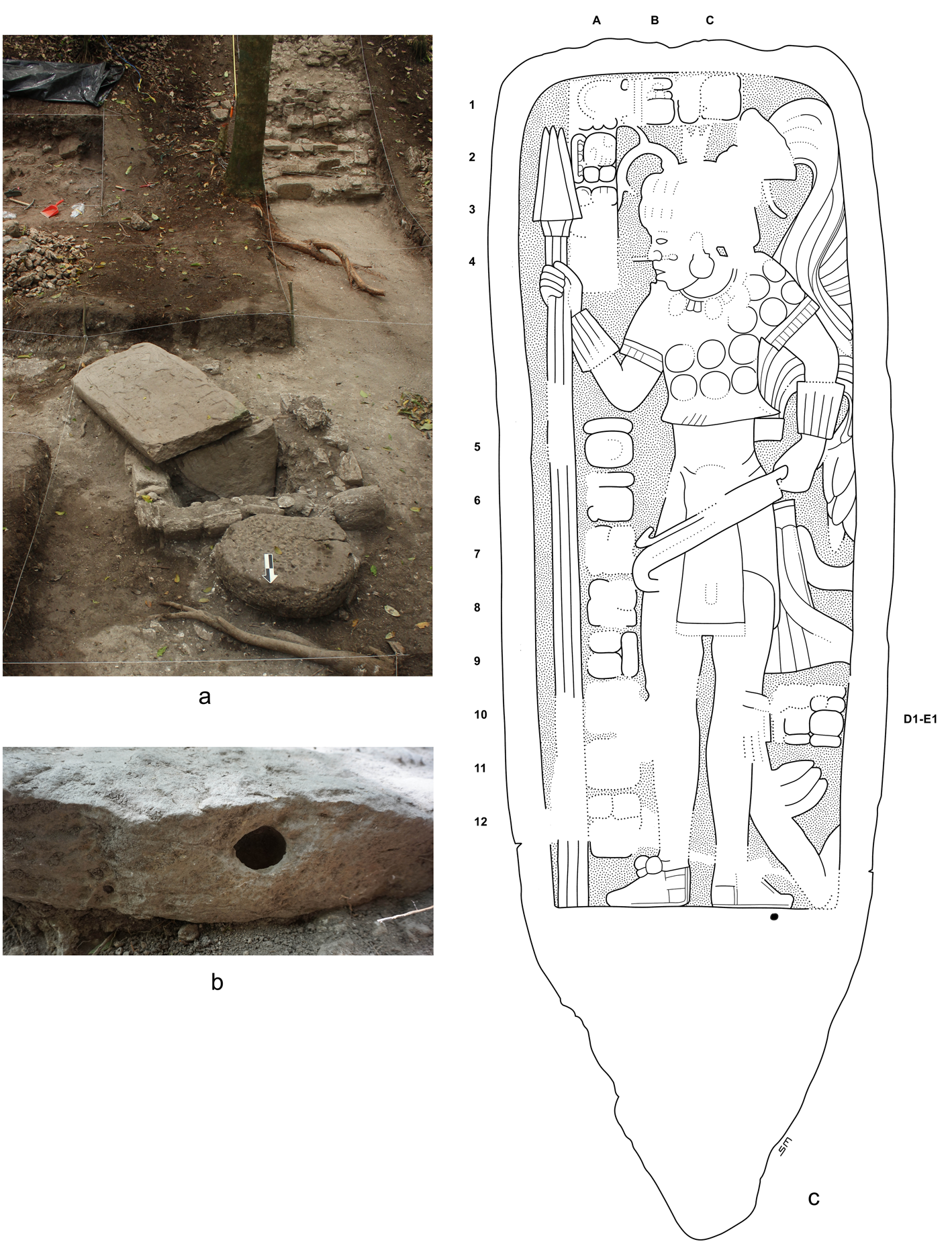

Ucanal Stela 29

Excavations by the PAU in 2019 uncovered Stela 29 and its associated Altar 19 in front of pyramid Structure K-2 in the public ceremonial Group K (see Figures 2 and 6; López López Reference López López, Halperin and Garrido2020). The stela broke at its base sometime in antiquity and was discovered face up, just 5–10 cm below the ground surface. As such, it was not well protected from the elements. Its base was still located in situ within a small, low masonry platform built during the Terminal Classic period to hold the stela and raise it above the patio floor surface. Altar 19 is circular, measuring 0.80 m in diameter and 0.65 m in height, and uncarved (see Figure 6a). The limestone material of the altar is encrusted heavily with pisolites and vadolites, which form from the continuous movement of grains that become coated with calcite in marine or cave environments. Excavations inside the low platform revealed a cache, Offering 20-1, of 18 obsidian and nine chert eccentrics in typical Peten/Belize Valley style. In addition to its archaeologically dated Terminal Classic context, the stela monument style fully conforms to this time period.

Figure 6. Ucanal Stela 29: (a) context of recovery in Group K on small platform with uncarved Altar 19; stairs of Structure K-2 in background (photo by M. F. López López); (b) top of stela showing 5 cm diameter hole (photo by M.F. López López); (c) drawing of stela (by S. Martin after photographs by C. Halperin and photogrammetry by M. Radenne; dimensions 2.47 × 0.80 × 0.13 m). (Color online)

The inscription on Stela 29 is, like that of Stela 10, badly preserved and has no surviving personal names or royal titles (see Figure 6c). What can be discerned is an opening Calendar Round date in which the coefficient for the tzolk'in day is a low number, and a coefficient for the haab month is fairly clearly “13.” That month sign has the distinctive outlines of a “color month” of either Yax, Ch'en, or Keh (Sak can be excluded). The sign at A2, directly beneath the tzolk'in, is what remains of the verb uchokow ch'aaj (“he scatters incense”)—a rite typically performed on period endings. The date that best fits these parameters, given the Terminal Classic style of the piece, is 2 Ajaw 13 Ch'en, corresponding to 10.2.10.0.0 (AD 879). If so, this would add three decades to the known history of Ucanal, thereby demonstrating that it was one of the last Classic period centers of the Southern Lowlands to have an active monument tradition.

Stela 29 depicts a ruler bedecked as a warrior, which indicates a cosmopolitan visual repertoire of clothing, accoutrements, and artistic styles. The most prominent references to foreign militarism are the long darts and atlatl wielded in his right and left hand, respectively. Although much eroded, the decorative plumage or cotton attached to the atlatl marks it as Central Mexican in style (see Figure 7a; Hruby Reference Hruby2020; Slater Reference Slater2011). During the Early Classic period, atlatls with such decorations in Maya art were wielded by warriors and rulers donning Teotihuacan-style clothing and adornments; they came to signify the power and alterity of this foreign place. Although Southern Maya Lowland peoples did use atlatls, the type they used is stylistically different: its slightly bent rod and its hooked feature (where the dart is supported) is located approximately one-third from the distal end, rather than at the very distal end. Such dart throwers rarely appear in Classic Maya art, and when they do, they are often brandished in hunting scenes (see Figure 7b) or are associated with the Maya hunting god Zip (Houston Reference Houston2019; Hruby Reference Hruby2020; Taube Reference Taube1992). The darts on Stela 29 are identified by both the triangular shape of the stone point and their plurality, because darts are almost always carried in multiples. The long length of the darts is a particular feature of warriors from Chichen Itza (Ringle Reference Ringle2009) and Cacaxtla (see Figures 6a and 7c; Brittenham Reference Brittenham2011:Figures 4 and 6). Shorter darts, however, are featured on Ucanal Stela 4 (AD 849; see Figure 3b), Cancuen Stela 2 (AD 790?; Maler Reference Maler1908:Plate 12), and Ceibal Stela 20 (AD 889; Just Reference Just2006:323). In contrast, on Classic period stelae, Maya rulers with weapons are commonly depicted with a single spear, identified by the laurel shape of the stone point (see Figure 6c).

Figure 7. Spears and darts: (a) Central Mexican style atlatl and darts, Upper register, interior wall, Lower Temple of the Jaguars, Chichen Itza (modified after Schele Drawing #5019); (b) hunting scene with Maya Lowland atlatl and darts (drawing by C. Halperin after K5857); (c) spear held in typical Late Classic pose of outward pointing feet and face in profile, Dos Pilas Stela 2 (Schele Drawing #7317).

Despite the reference to Central Mexican weapons, the artisans of Stela 29 rendered the ruler in a typical pose of Lowland Maya kings, thereby mixing foreign symbolism with local compositional rendering. This pose—his feet pointing outward, the body in a frontal position, and the head in profile facing to his right—is a quintessential pose of Late and Terminal Classic Maya stelae (see Figure 7c; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:22–28). Likewise, whereas Terminal Classic and Postclassic figures from the Northern Maya Lowlands and Central Mexico hold darts in active poses, often with the darts crossing the body or with the distal ends pointing downward (see Figure 7a), the Stela 29 figure holds the long darts in the same rigid pose as Classic Maya rulers: with his right arm extended and the darts placed vertically with the distal end upright similar to the way Maya rulers hold their spears.

Another cosmopolitan element in Stela 29 is the figure's tubular nose bar. Although nose beads and other nose ornaments are common paraphernalia of Maya elites during every period, this tubular form is very rarely seen with Classic Maya kings until the Terminal Classic period (Halperin Reference Halperin2017b:519–522; Kettunen Reference Kettunen2006). For example, such an ornament does not make an appearance among the monuments from Machaquilá until late in the reign of Juun Tzuk Took’ with his Stela 6 and 11 (AD 836, AD 840), the latest monuments known from the site (see Figure 8e; Just Reference Just2006). Likewise at Ceibal, rulers do not wear the tubular nose bar until AD 849 with Wat'ul K'atel (Stela 10) and various monuments after this date (Stela 3, 13). Although such a nose ornament did indeed become popular during the Terminal Classic period, it is difficult to tie it to a single origin point or region (Halperin Reference Halperin2017b; Kettunen Reference Kettunen2006). Classic Maya deity depictions, most notably God C and more rarely rulers (e.g., Yaxchilan Lintel 17), could wear similar tubular nose ornaments. They were also a common feature of rulers and warriors throughout Epiclassic Mesoamerica, including those depicted at the sites of Tula, Cacaxtla (see Figure 8c), and Chichen Itza (see Figure 7a). Such widespread adoption of the tubular nose ornament likely rendered it as part of an “international” style that crosscut regional or cultural affinity.

Figure 8. Changing Terminal Classic clothing and adornment: (a) short-sleeved ichachuipilli, Battle Mural, Cacaxtla (photograph by R. Alvardo and M.J. Chávez, used with permission from the Proyecto La Pintura Mural Prehispánica en México); (b) short-sleeved warrior top, Battle Mural, Cacaxtla (photograph by R. Alvardo and M. J. Chávez, used with permission from the Proyecto La Pintura Mural Prehispánica en México); (c) warrior with tubular nose bar and atlatl-dart, Battle Mural, Cacaxtla (photograph by R. Alvardo and M. J. Chávez, used with permission from the Proyecto La Pintura Mural Prehispánica en México); (d) feathered serpent warrior wearing short-sleeved ichachuipilli adorned with circles and wielding atlatl and darts, south mural, Upper Temple of the Jaguars, Chichen Itza (drawn by C. Halperin after Ringle Reference Ringle2009:Figure15c); (e) details of rulers on ninth-century Machaquilá's stelae in chronological order from left to right (AD 801, AD 816, AD 820, AD 825, AD 831, AD 836, AD 840) with tubular nose bars worn only on the final two stelae, Stela 6 and 5 (after Just Reference Just2007:Figure 12). (Color online)

In addition to the tubular nose bar, the ruler on Stela 29 wears a garment that became popular across many different regions of Mesoamerica during the Terminal Classic period (see Figure 8a, b, d). This jerkin-like garment, called an ichachuipilli in Nahuatl (Anawalt Reference Anawalt1981:47–48), is a closed-sewn, short-sleeved shirt. The ichachuipilli was an abbreviated, more breathable (albeit less protective) form of cotton armor than the full-length, long-sleeved cotton body suit. In depictions of Late Classic Maya kings from the Southern Lowlands, the rulers occasionally wear warrior garb of this general sort (e.g., Yaxchilan Lintel 16), and it is common in the battle scenes on two polychrome vessels from the Nebaj region of Highland Guatemala (Kerr Reference Kerr2019:K2352, K2206). It is, however, more frequently seen in Epiclassic and Terminal Classic warrior depictions from Chichen Itza, Kabah, Cacaxtla, and Tula, as well as those from the later Postclassic Central Mexican codices (Anawalt Reference Anawalt1981; Brittenham Reference Brittenham2015; Ringle Reference Ringle2009). The ichachuipilli from Stela 29, with its distinctive decorative circles, closely resembles one worn by a figure Ringle (Reference Ringle2009) calls “warrior B” on the Upper Temple of the Jaguars, in Chichen Itza (see Figure 8d; Ringle Reference Ringle2009:Figure 15c), and by a central figure on the north wall of the North Temple of Chichen Itza's great ballcourt (Ringle Reference Ringle2004:Figure 3). It also appears closer to home on the floating figure in Ucanal Stela 4, whose foreign allusions are made clear by the plumed Central Mexican atlatl and darts he holds, as mentioned earlier (Figure 2a).

The ruler from Stela 29 is also typical of late Maya depictions of rulership in his slim bodily proportions and modest display of jewelry and other adornment. The move away from ostentatious displays and toward a slimmer form began in the early ninth century and became more pronounced through time, as Just (Reference Just2006, Reference Just2007) documented for the site of Machaquilá (see Figure 8e). Likewise, Halperin and Garrido (Reference Halperin and Garrido2019) note a rejection of ostentatious adornment and elaboration in the Terminal Classic architecture at the site of Ucanal.

In addition to Stela 29's visual system of representation and style, it is worth noting that it has two holes, features that hint at its performative capabilities. The locations of these holes contrast with carved markings or bash marks that appear to have been aimed at vital parts of the individual depicted to deface, deactivate, or destroy their essence (Just Reference Just2005:75–80). One hole (5 cm in diameter and 8 cm in depth) is located at the top of the monument and appears to have been drilled vertically into the superior end of the monument (see Figure 6b). Such a location would have rendered the hole invisible to observers at ground level but visible to individuals located high up on Pyramid K-2 or to deities hovering in the sky. The hole may have been used to secure a perishable object, such as a wooden rod or plug (compare Machaquilá Stela 13, which has a plug-like top), or it may have captured rainwater, albeit in a minuscule quantity. The other hole, which may have been natural because another hole similar to it is found in the buried, butt end of the stela, is located near the figure's left foot and measures 2 cm in diameter and 3 cm in depth. Quartz crystal flakes were found lodged within the hole and were absent in the hole in the buried, butt end of the stela (López López Reference López López, Halperin and Garrido2020). Quartz crystal is used for divinatory purposes among contemporary Maya peoples and is often found archaeologically in ritual contexts, such as caves and shrines (Brady and Prufer Reference Brady and Prufer2001). Elsewhere in Mesoamerica, holes or niches within monuments and sculptures may have served as places for offerings for animating the monument or communicating with the supernatural, such as those from the “Great Goddess” monuments from Teotihuacan (Paulinyi Reference Paulinyi2006:Figure 11a) or the stucco friezes and sculptures from Postclassic Mayapan (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff and Wauchope1965:Figure 105). These holes, located at the heart or heads of the figures, however, clearly differ in their placement from those of Stela 29.

Discussion

Although the region of the Southern Maya Lowlands is often considered peripheral to the artistic borrowings, religious pilgrimages, diplomatic gift giving, and political networking of Mesoamerica during the ninth century, Terminal Classic monuments from this region—in particular, the newly discovered Ucanal Stela 29—point to the active role that local elites played in embedding themselves into and contributing to the cosmopolitan discourses of their era. This cosmopolitan aesthetic drew its inspiration from multiple sources, rather than from a deep affinity to a single site or region of political power. Mesoamerican sites, such as Ceibal, Xochicalco, Cacaxtla, El Tajin, Tula, and Chichen Itza, adopted visual programs that emphasized eclecticism, mixing elements, styles, and techniques from multiple cultural regions and political centers. Although, in some cases, the direction of influence appears obvious, such as the Maya-style seated figures at the bottom register of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent at Xochicalco, these elements were often combined, in the same monument program, with Zapotec-style glyphic elements, Teotihuacan-inspired feathered serpents, Central Mexican-style warriors, and an architectural form that crosscut multiple regions (Nagao Reference Nagao, Diehl and Berlo1989).

Ucanal Stela 29 embodies such eclecticism in incorporating elements with foreign affinities, such as the non-Maya-style atlatl and the wearing of an ichachuipilli, with a conventional and highly localized bodily pose, layout of text and image, and, from what can be identified, its writing program. The slim bodily proportions and simplicity of adornment on the figure of Stela 29 stray from Classic period norms and conform to the simplicity and proportions of ninth-century bodily depictions elsewhere in Mesoamerica. Likewise, although some affinities to Chichen Itza may be suggested, such as the circle-decorated ichachuipilli warrior shirts found both there and at Ucanal (Stela 4 and 29), other features, such as the tubular nose bar, were less a sign of singular origin or belonging and more an indication of the sharing of practices and traditions that crosscut region, language, or culture. As such, Stela 29 exhibits a vernacular cosmopolitanism by holding in tension local expressions of identity and affiliation with a broader sense of belonging.

In addition to its monuments, Ucanal's ceremonial architecture exhibited ties with peoples and places from afar. For example, its circular and semicircular shrines in Group A (Halperin and Garrido Reference Halperin and Garrido2019; Laporte and Mejia Reference Laporte, Mejía, Acuña, Alvarado, Alvarez and Arroyave2002:Figure 15a) exhibited trends shared by both small and large centers throughout northern Belize, northern Yucatan, and the Gulf Coast running all the way up to the Huasteca (Alarcón and Ahuja Reference Alarcón, Ahuja, Faust and Richter2015; Halperin Reference Halperin, Halperin and Schwartz2017c; Harrison-Buck and McAnany Reference Harrison-Buck and McAnany2013; Pollock Reference Pollock1936). Likewise, Ucanal's adoption of a half-enclosed or “T”-shaped ballcourt, Ballcourt #1, during the Terminal Classic period was part of a new ballcourt style found not only at a small handful of centers in the Southern Maya Lowlands, such as Jimbal, Calzada Mopan, and Xunantunich, but also at centers farther away in northern Yucatan (Chichen Itza and Sayil) and Chiapas, Mexico (Halperin, Garrido, et al. Reference Halperin, Garrido, Salas and LeMoine2020; Montmollin Reference Montmollin1997; Scarborough Reference Scarborough, Scarborough and Wilcox1991; Taladoire and Colsnet Reference Taladoire, Colsenet, Scarborough and Wilcox1991).

What is clear is that Ucanal had a broad-scale network of exchange relations from multiple places during the Terminal Classic period. But ideas and styles do not float on the wind, and any understanding of cosmopolitanism is one that must include viable modes of transmission. Importantly, this concept presupposes substantial circulation of peoples who spread both foreign symbols and the contextual knowledge of how they could be used. The disappearance of former Classic Maya power structures created new entrepreneurial opportunities in the Terminal Classic, reinvigorating long-distance commercial exchange. This should be seen as multidirectional in that Maya traders could have been traveling west as easily as Gulf Coast and Central Mexican merchants were journeying east. Likewise, movements of families, diplomats, and traders between the Southern and Northern Lowlands were also in play (Boot Reference Boot2005; Rice and Rice Reference Rice, Rice, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004). There is some evidence at Ucanal for contacts with the wider world, including a small frequency of ceramic types common to northern Yucatan. Fine Orange ceramics, a type originating in the western zone of the Maya area, were well distributed throughout the site, and households began to have greater access to extrusive igneous groundstone tools from Highland Guatemala (De Chantal Reference De Chantal2019; Halperin, Garrido, et al. Reference Halperin, Garrido, Salas and LeMoine2020). Excavations have also uncovered limited quantities of obsidian from the Central Mexican highlands (Pachuca, Tulancingo, Ucareo) during this time (Hruby et al. Reference Hruby, Halperin, Gariépy, Bourgeois and Powell2019).

In their exploration of the Quetzalcoatl “cult” that accompanies many ninth-century developments—especially in the Northern Lowlands—William Ringle, Tomas Gallareta Negrón, and George Bey (Reference Ringle, Negrón and Bey1998:213–214) posit some potential pathways. Comparing the phenomenon to the spread of Christianity and Islam, they note how these religious movements expanded by multimodal processes of commerce, pilgrimage, migration, and militarism. In Postclassic Central Mexico we know that elite actors engaged in pilgrimages to places of special religious significance, and the spread of nonlocal deities in the ninth century could have stimulated similar visits to cult centers in foreign lands. The rapid and comprehensive diffusion of ideas may implicate another potential mode of transmission: intellectual exchanges that were independent of political control. The homogeneity of Classic Maya culture and the speedy dissemination of innovations speak to ongoing contacts between various specialists, including savants and master artists, that crosscut political and linguistic boundaries (Martin Reference Martin2020:306–307). A system of communication such as this may have persisted and helped shape the developments of the ninth century as well. Less frequently considered are the movement of women, sometimes as captives and sometimes as brides, as well as the migrations of families that invigorated the spread of ideas and reworked local identities (Halperin Reference Halperin2017a). The introduction of comales, griddles used to toast foods such as tortillas, to the site of Ucanal during the Terminal Classic period underscores that cooking practices long common in Central Mexico and other regions in Mesoamerica were also quick to spread to the Maya area during this time (Halperin Reference Halperin2017a).

In terms of migration, today we recognize that Maya cities were diverse places in which between 11% and 40% of inhabitants might be born outside their immediate region (Miller Wolf Reference Miller Wolf2015; Price et al. Reference Price, Burton, Sharer, Buikstra, Wright, Traxler and Miller2010; Wright Reference Wright2012). Thus far, archaeological research at the site of Ucanal does not provide evidence for a wholesale population replacement by new immigrants during the Terminal Classic period; excavations instead reveal substantial occupational continuity between Late Classic and Terminal Classic residences (Halperin and Garrido, ed. Reference Halperin and Garrido2016, Reference Halperin and Garrido2018, Reference Halperin and Garrido2019). Isotopic analyses of human teeth indicate primarily local-born individuals for the Terminal Classic period (Flynn Arajdal Reference Flynn-Arajdal2020), although these preliminary data need to be expanded to provide more conclusive patterns.

There is, nonetheless, reason to believe that the cosmopolitan aesthetic of ninth-century monuments at Ucanal may have been stimulated by foreign peoples visiting or even living at the site. The possibility that a foreign lord presided over K'anwitznal is suggested by the name of a character directly associated with the site in the early ninth century called Papamalil (Guenter Reference Guenter1999:104–107; Pallán Gayol and Meléndez Guadarrama Reference Pallán Gayol, Guadarrama and van Broekhoven2010:18–19) or Papmalil (Martin Reference Martin2020:295–296). The latter name has clear correspondences with naming practices among the Chontal Maya of the Gulf Coast and, as a result, offers what could be the first direct connection to this part of Mesoamerica, one that features strongly in past theories about the Terminal Classic developments.Footnote 4 Inscriptions at both Caracol and Naranjo—traditional enemies of Ucanal—describe Papmalil hosting rituals for the Caracol and Naranjo kings at Ucanal in about AD 817–820, and these include phrasings that make his superior status very clear. Significantly, he is never ascribed the Ucanal emblem glyph but instead carries the title chik'in kaloomte’ (“western great lord”)—a high epithet that alludes to real or symbolic ties to western realms. In the two depictions of Papmalil at Caracol (Altar 12, 13) he wears specific headgear—a beaded wrap tied at the back, with a hair knot topped in one case by three feathers—that elsewhere signals a western cultural affiliation.

This lack of a local title—an otherwise indispensable marker of Classic Maya kingship—offers the interesting prospect that, while Papmalil ruled at Ucanal, he did not do so as a conventional king. His “foreignness” is clearly relevant to the hybridity of Ucanal Stela 4, the product of the next generation, where lords do carry the Ucanal emblem glyph. Since that title is closely linked to bloodline, we may be looking at the products of intermarriage and a local legitimacy that had been restored through the maternal line. The square day names of the senior and junior kings depicted on Stela 4—one a kaloomte’ (“great lord”) the other simply an ajaw (“lord”)—appear within conventional Maya royal nomenclature, producing hybrid identities to match that of the monument's iconographic program.

Further, it can be no coincidence that Ucanal is cited as the point of origin for a new king at Ceibal, the aforementioned Wat'ul K'atel, the same character linked to the onset of cosmopolitan features at that site after AD 849 (Schele and Mathews Reference Schele and Mathews1998:183). Ceibal went on to become the focus of this eclecticism, making it, along with Ucanal, one of the ninth-century upstart polities that defied the wider trend toward decline and dissolution. The key importance of Ucanal lies in its place within these wider developments and shifting power structures, which we are only just beginning to understand (Martin Reference Martin2020:284–299).

Conclusion

A renewed look at previously documented monuments and an analysis of a newly discovered one, Stela 29, reveal an important corpus of Terminal Classic period stone monuments at the site of Ucanal. These monuments indicate that Ucanal actively participated in the shifting artistic and political trends of this late time period. In several paired monuments in the round, there was an openness to depicting liminal and ulterior trickster figures in the form of squatting monkeys and squatting fat supernaturals, figures who had been restricted primarily to small-scale media earlier in the Classic period. In addition, iconographic, stylistic, and textual features of the monuments, most particularly Stela 29 and Stela 4, make increasing references to foreign peoples and practices. Such elements were not wholesale adoptions of foreign monumental styles. Rather, they reflect an engagement with a vernacular cosmopolitanism, whereby critical choices were made to demonstrate connections with both local traditions in the Southern Maya Lowlands and political and cultural entities that lay much farther afield.

Acknowledgments

Research by the Proyecto Arquólogico Ucanal during the 2019 field season was supported by grants from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC/CRSH), San Diego Mesa College, and the Université de Montréal. We are grateful to field personnel from San José, Barrio Nuevo San José, and Pichelito II, as well as students and professional archaeologists from Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (CUDEP and Guatemala City), Université de Montréal, San Diego Mesa College, University of West Florida, University of Mississippi, and University of Kentucky. We owe special thanks to project codirector Jose Luis Garrido, project lab director Miriam Salas, and project archaeologist María Fernanda López, who helped excavate Stela 29. Thanks are extended to the Departmento de Monumentos Prehispanicos y Coloniales from the Ministerio de Culture y Deportes in Guatemala for their support and permission to work at Ucanal. Finally, we are grateful to three annoymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Digital data are housed in the Ancient Mesoamerican Laboratory at the Université de Montréal. Stela 29 and Altar 19 are currently housed in the Salón Rigoberta Menchú in the old Convento de Santo Domingo, Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural, Guatemala City, Guatemala.