Shell middens are archaeological sites that result from the accumulation of shellfish and other coastal refuse produced by the harvesting of marine resources (Claassen Reference Claassen1998; Stein Reference Stein1992; Waselkov Reference Waselkov1987). The study of these sites has focused mainly on the frequency and variability of the invertebrate species present in their zooarchaeological assemblages in an effort to understand their economic role in societies and climate change (Jerardino Reference Jerardino1997; Koike Reference Koike, Akazawa and Aikens1986; Sandweiss Reference Sandweiss, Reitz, Newsom and Scudder1996). Other, equally relevant groups of studies have focused on formation processes, considering, for instance, shells as sedimentary particles from a geoarchaeological perspective (Erlandson and Moss Reference Erlandson and Moss2001; Favier-Dubois and Borella Reference Dubois, Cristian and Borella2007; Mason et al. Reference Mason, Peterson and Tiffany1998; Stein Reference Stein1992). A third area of interest is the architectural dimension of mound building, which is studied by interpreting the mounds’ territorial significance (DeBlasis et al. Reference DeBlasis, Kneip, Scheel-Ybert, Giannini and Gaspar2007; Gamble Reference Gamble2017; Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020). The high frequency of shell refuse in these sites has often precluded intrasite spatial analyses, which generally require the excavation of large areas, thus creating special challenges for sampling (Jerardino Reference Jerardino2016; Niemeyer and Schiappacasse Reference Niemeyer and Schiappacasse1969; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Marquardt, Cherkinsky, Thompson, Walker, Newsom and Savarese2016). However, in some circumstances, the spatial organization of shell middens and heaps may be informative regarding the way in which activities were structured within a site. In sites such as Quebrada Jaguay (QJ280) and Quebrada de los Burros along the central Andean coast of South America, the distribution of shell remains and other features has allowed the identification of activity areas, dwelling spaces of hunter-gatherers, or both (Lavallée and Julien Reference Lavallée and Julien2012; Sandweiss et al. Reference Sandweiss, McInnis, Burger, Cano, Ojeda, Paredes, Sandweiss and Glascock1998, Reference Sandweiss, Asunción Cano and Roque1999).

Distinguishing activity areas is key to understanding the spatial organization of a settlement. Because of the high visibility and preservation of shell middens, they may be regarded as ephemeral architectural features that are useful for identifying aspects of the spatial organization of residential campsites. This article presents a case study in which the structural characteristics and location of shell middens, hearths, activity areas, void spaces, and other features are used to interpret site planning. The Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007) site is a small shell midden in the Los Vilos area of north-central Chile (Figure 1a), where preferential harvesting and processing of macha (Mesodesma donacium), a surf clam, occurred over a series of short-span occupations around 3000–3500 cal BP. The results presented here have methodological implications for understanding sites that otherwise do not show highly visible or preserved structures and organic remains. From this perspective, the two main contributions of this study are not only its characterization of middens and features as deposits bearing cultural information but also its consideration of “empty” spaces, seldom understood as sources that provide information about spatial organization.

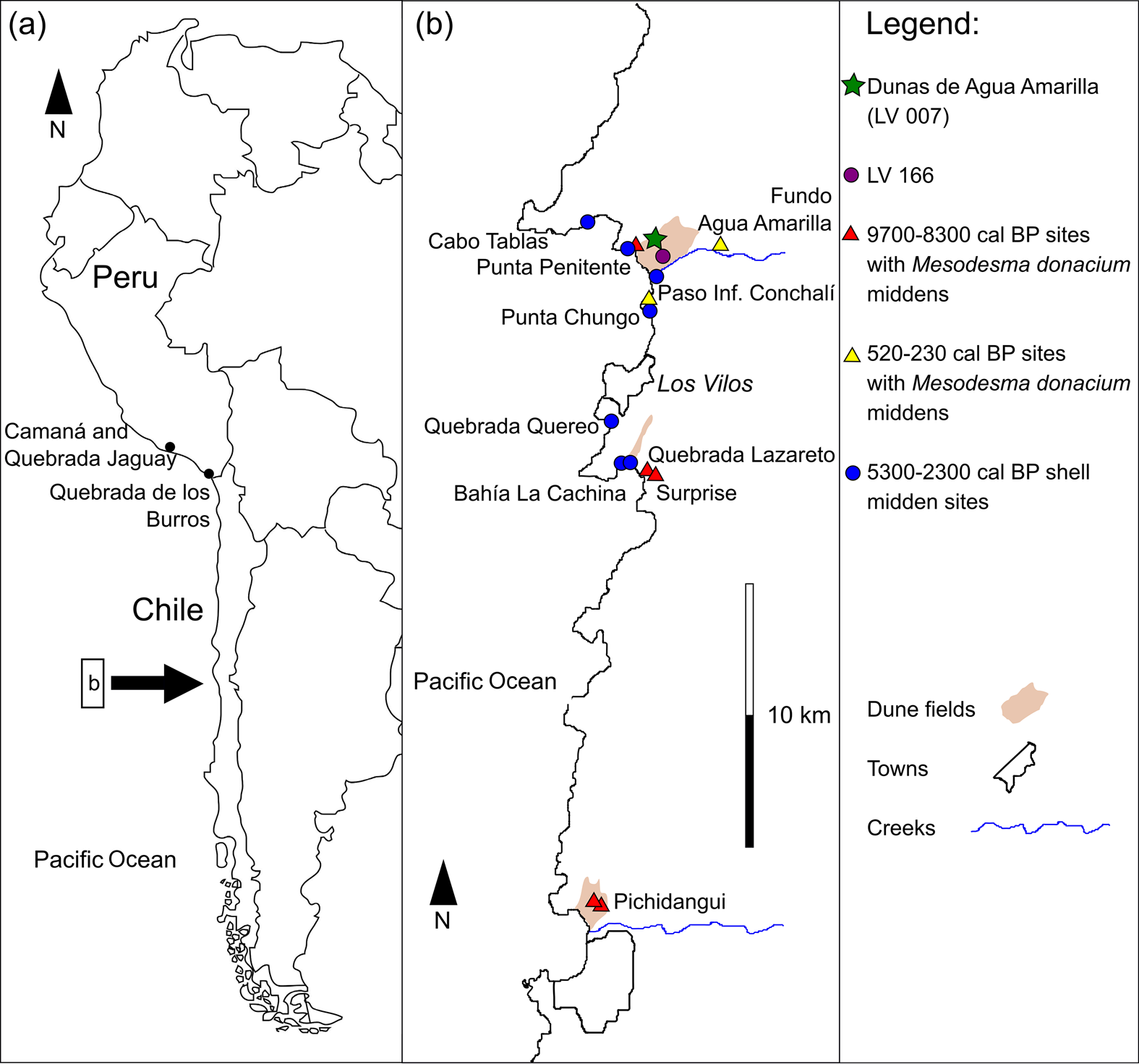

Figure 1. Map of (a) western South America and (b) the study area with the location of Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007) and other sites mentioned in the article. (Color online)

More than 400 archaeological sites of diverse characteristics have been recorded between 31°45′ and 32° S, the coastal area around the town of Los Vilos (Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020). This remarkable site density contrasts with equivalent littoral extensions to the north or south of this area. The marine richness of this protected bay area attracted coastal foragers repeatedly across the Holocene (Figure 1b). Hence, the main archaeological features are shell middens of variable sizes and degrees of redundancy (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Báez and Vargas1995).

The occupation of this coastal strip took many shapes throughout this period, as indicated by changes in invertebrate selectivity, procurement behaviors, settlement location, and refuse treatment. By 12,000 cal BP, the first colonizers with a coastal economy established settlement clusters at key locations that enabled extensive littoral provision (Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020). The advent of major regional climatic changes, of which moisture reduction was the most prominent, led to a decrease in shellfish procurement (yielding less visible and smaller middens) by 9700 cal BP, followed by an apparent abandonment of these practices by 8300 cal BP (Ballester et al. Reference Ballester, Donald Jackson, Antonio Maldonado and Seguel2012; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, César Méndez, Jackson and Seguel2005; Maldonado and Villagrán Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2006). A resurgence of shellfish gathering occurred at 7600 cal BP, when centralized campsites were used to organize the provisioning of a wide variety of resources, including marine and terrestrial mammals and fish (Jackson Reference Jackson2004). Most notably, the largest available specimens of loco (Concholepas concholepas), the highest meat-yielding invertebrate, were field processed to reduce their shell weight, thus producing large shell midden deposits close to the shore (Jackson and Méndez Reference Jackson and Méndez2005; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Báez and Arata2004). The most marked change in the interaction between humans and shellfish came with the collection of the broadest diversity of intertidal invertebrate ecosystems by 5300 cal BP (Méndez and Jackson Reference Méndez and Jackson2006). At the same time there was increased residential site frequency as suggested by the dense, organic, and fragmented shellfish-rich stratigraphic layers found atop most previously occupied sites; hence, a residential mobility pattern occurring along the coast has been proposed for this period (Méndez and Jackson Reference Méndez and Jackson2004). This prominent role of coastal ecosystems probably lasted until about 2300 cal BP, given that during the last two millennia there were variable strategies of coastal use, but with a dominant occupation of inland spaces that were better suited for horticulture and animal husbandry (Gómez and Pacheco Reference Gómez and Pacheco2016; Massone and Jackson Reference Massone and Jackson1994; Seguel et al. Reference Seguel, Jackson, Rodríguez, Báez, Novoa and Henríquez1994; Troncoso et al. Reference Troncoso, Cristian Becker, Paola González and Solervicens2009).

The Study Area and Present/Past Environmental Conditions

The study area is located 6 km north of the town of Los Vilos on the coast of north-central Chile (31°54′ S; Figure 1). This area lays in the transition between the semiarid and Mediterranean climates. It is characterized by long and dry summers, with a rainy season during the winter that is caused by the permanent presence of the South Pacific subtropical anticyclone, which seasonally blocks the westerly wind belt (Garreaud et al. Reference Garreaud, Vuille, Compagnucci and Marengo2009). This area is highly sensitive to the interannual variations associated with the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) system, which brings above-average warm and humid atmospheric conditions during El Niño years, with cold and dry conditions prevailing during La Niña years (Montecinos and Aceituno Reference Montecinos and Aceituno2003). Plant communities include Asteraceae-dominated shrubland extending across the coastal plains, whereas sclerophyll forests occur in deep gullies (Luebert and Pliscoff Reference Luebert and Pliscoff2006).

Local pollen records from coastal swamp forests indicate climatic variability during the Holocene resulting from changes in the position and strength of the South Pacific subtropical anticyclone (Maldonado and Villagrán Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2002, Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2006). Relatively humid conditions during the Pleistocene–Holocene transition were followed by an extremely arid phase from 8200–6200 cal BP (Maldonado and Villagrán Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2006; Maldonado et al. Reference Maldonado, César Méndez, Donald Jackson and Latorre2010). An increase in swamp forest taxa indicated a gradual increase in moisture, peaking at 4200 cal BP (Maldonado and Villagrán Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2002, Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2006), which was in accord with a wetter late Holocene as indicated by paleoenvironmental records in the broader area of central Chile (Maldonado et al. Reference Maldonado, De Porras, Zamora, Rivadeneira, Abarzúa, Falabella, Uribe, Sanhueza, Aldunate and Hidalgo2016). Conditions during the late Holocene fluctuated less, showing a trend to relatively drier conditions after 3800 cal BP that peaked around 2700 cal BP; after that, there was a gradual trend to wetter conditions toward 2000 cal BP (Maldonado and Villagrán Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2002, Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2006). The last 2,000 years seemed to have been the most humid period of the Holocene at this latitude, with minor variations (Maldonado et al. Reference Maldonado, De Porras, Zamora, Rivadeneira, Abarzúa, Falabella, Uribe, Sanhueza, Aldunate and Hidalgo2016); the highest ENSO activity was also recorded during this time period (Rein et al. Reference Rein, Andreas Lückge, Frank Sirocko and Dullo2005).

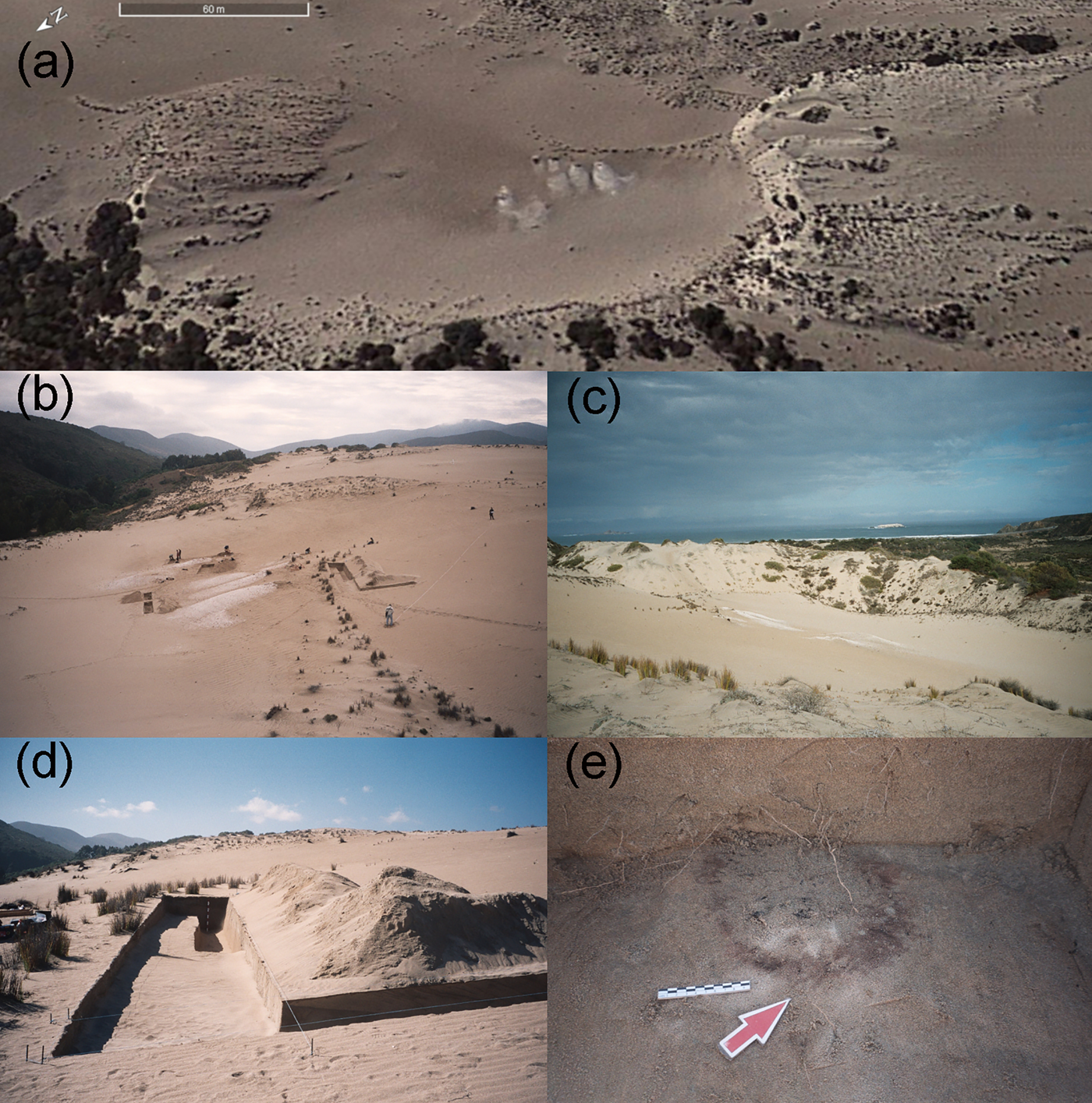

The site we studied, LV 007—31°51′20″ S; 71°29′50″ W; 40 masl—is located on an active dune field known as Agua Amarilla, which is north of Conchalí Creek. Dune crests indicate a dominant southwesterly wind (200°) direction. The dunes may have been formed as early as 30,000–16,500 cal BP, judging from the radiocarbon dates on associated deposits in the surrounding area (Méndez et al. Reference Méndez, Seguel, Nuevo-Delaunay, Murillo, Mendoza, Jackson and Maldonado2020; Ortega et al. Reference Ortega, Gabriel Vargas, Rutllant and Méndez2012). The site lies at the center of a deflated depression that offered protection from prevailing winds (Figure 2a). Archaeological material occurs over an area of approximately 1,300 m2. The Malpaso ravine, which is 100 m to the northwest, provides a semipermanent drinkable water supply (Figure 2b), whereas only 1.2 km to the west, the coast generates abundant, permanent, and varied marine biodiversity (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Images of Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007) site: (a) oblique view of the depression bounding the site (scale 60 m, Google Earth, 2012 image); (b) general view of the site and the Malpaso ravine to the north; (c) general view of the site and the Pacific Ocean (Agua Amarilla beach) to the west; (d) intersection between two excavated trenches; (e) example of one of the excavated hearths. (Color online)

Analyses of oxygen stable isotopes of δ18O on Mesodesma donacium shells obtained from the site, compared with modern samples from the coast at La Serena (~30° S) and Pullalli (~33° S), allow us to preliminarily evaluate changes in sea-surface temperatures during the site's occupation (Figure 3; Carré et al. Reference Carré, Ilhem Bentaleb, Neil Ogle, Sheyla Zevallos, Kalin and Fontugne2005). Positive δ18O values of shell samples from 2006 obtained in La Serena (200 km north of Los Vilos) are indicative of relatively dry and cool conditions. Conversely, the negative δ18O values of the shell sample from Pullalli harvested in December 1983 indicate warmer and wetter conditions experienced during the 1982–1983 El Niño event. The δ18O values from archaeological samples collected in shell midden 4 at LV 007 are close in range to those recorded at La Serena, suggesting conditions were similar to modern normal conditions at ~30° S. Lower δ18O values in shell midden 11 suggest slightly warmer environmental conditions during the deposition of this occupational event. Assuming a constant isotopic composition of the seawater, the temperature would be ca. 1°C warmer at that time. Shells from LV 007 also recorded lower seasonal amplitude than the modern samples, which may suggest less seasonal variability in the sea temperature or a different precipitation distribution across the year.

Figure 3. Values of δ18O from modern Mesodesma donacium shell samples from La Serena (30° S; black triangles), Pullalli (33° S, black square), and the archaeological samples from shell middens (SM) from LV 007 at Los Vilos (31°51′ S; white squares).

Methods

The study of the Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007) site was approached from a spatial perspective; hence, we recorded its extension, limits, and the distribution of visible surface features, primarily shell middens. We also examined areas without evident remains of cultural deposition, so we could fully understand the spatial organization of the site. Both types of areas were included in the excavation plan. Stratigraphic excavations covered 83 m2 and were organized in trenches (Figure 2d) that included continuous areas to provide an ample perspective for understanding the spatial extension of middens and other archaeological features (Table 1). We also revealed empty spaces as a way of detecting the subsurface limits of areas for presumed activities.

Table 1. Excavated Units, Dimensions, and Main Associated Archaeological Record at Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007).

Additionally, 1 m2 units were excavated on 8 of the 14 visible shell middens to define midden stratigraphy, characterize and quantify their malacological composition, and assess the superposition of individual depositional events. Other material remains, even if only represented in minor ways, were used for the overall characterization of assemblages representing site activities and preferential subsistence choices. Malacological quantification (MNI) followed key indicators based on local collections at the level of species and subspecies. Mesodesma donacium, the most abundantly represented species, was quantified based on valve laterality.

The surface distribution of the 14 small shell middens and lithic debris concentrations and their positioning next to areas devoid of archaeological material, which were suggestive of nonrefuse spaces, indicate some degree of site structure. These hypothetically “clean” areas are the locations where dwelling spaces would be expected, although they are not directly visible. Excavations distributed across the site recorded an upper single stratigraphic unit composed of sand, with subunits distinguishable by grain size, color, stratification, organic matter content, and the remains of invertebrates. The chronology of the anthropogenic deposition at LV 007 is constrained by two radiocarbon dates and one thermoluminescence date measured on a fire-cracked rock. Radiocarbon dates were calibrated with Calib 7.1 (Stuiver et al. Reference Stuiver, Reimer and Reimer2019) using ShCal 13 (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Hua, Blackwell, Niu, Buck, Guilderson, Heaton, Palmer, Reimer, Reimer, Turney and Zimmerman2013) and by applying a local reservoir correction, ΔR = 165 ± 107, to the marine sample (Carré et al. Reference Carré, Jackson, Maldonado, Chase and Sachs2016). Calibrated dates are reported as 2σ intervals.

Results

The Shell Middens: Formal Attributes and Composition

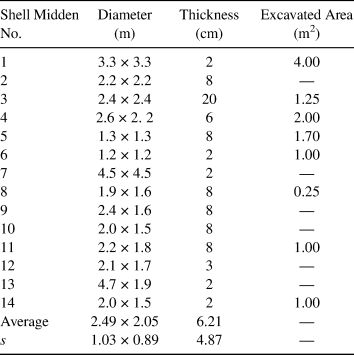

The site comprises 14 small-sized shell middens, mainly circular in shape and resulting from the processing of mollusks gathered in the close intertidal area (Table 2). Diameters of these refuse concentrations range from 1.2 to 4.9 m, and the thickness of the deposits range from 2 to 20 cm.

Table 2. Formal Characteristics of the Shell Middens at Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007).

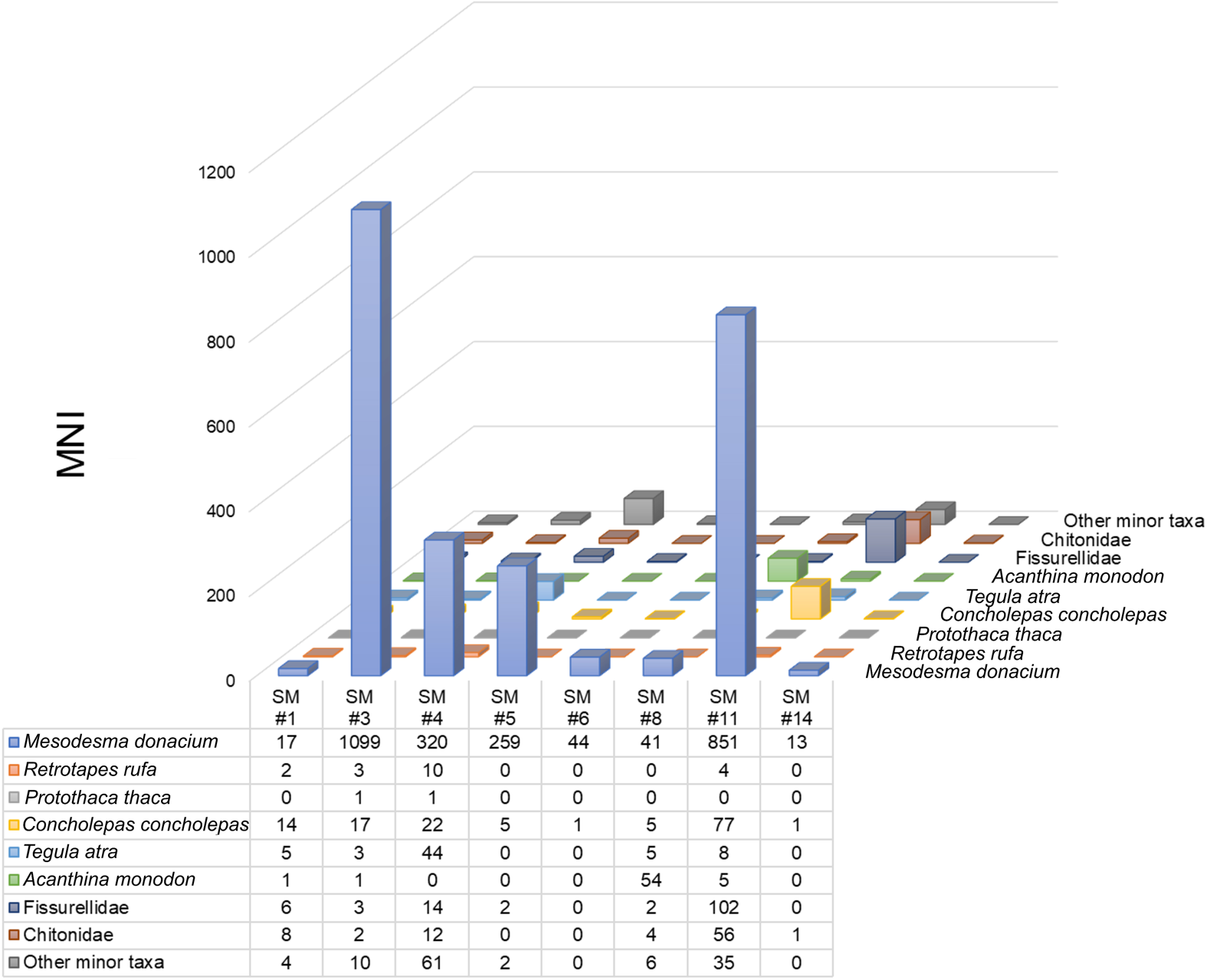

A total of 24 mollusk species are represented in the sampled middens (Supplemental Table 1). The best-represented species is the Mesodesma donacium, which comprises 81% of the cumulative evidence at the site (minimum number of individuals [MNI]; average per midden = 72.9%; s = 27.4; Figure 4). In the four largest sampled shell middens, machas represent more than 90% of the MNI. This bivalve occurs in beaches with a sandy substrate, such as the one located 1,200 m west of the site. The difference between the right and left valves within the samples is <1%, which indicates that complete individuals were transported to the site. Shannon-Weiner diversity index values for each sampled midden range from 0.96 (very diverse) to 0.05 (very homogeneous; Supplemental Table 1). The second-most represented mollusk is the abalone-type Concholepas concholepas, a high-biomass gastropod occurring in rocky intertidal to subtidal zones that are available about 1.2 km from the site. The Fissurella genus represents 3.95% of the collected mollusks. Midden 8 shows a high representation of yet another rocky gastropod, the small-sized white snail Acanthina monodon. Other species occur at frequencies less than 2% and do not contribute substantially to the gathering choices represented by this assemblage.

Figure 4. Mollusk taxa frequency (grouped) by sampled shell midden (SM) at Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007). (Color online)

Other marine invertebrates, such as sea urchins (Loxechinus albus) and crustaceans, are represented by fragments and may reflect opportunistic gathering. Fish bone remains (NISP 128) represent five species—Sebastes capensis, Thirsistes atun, Trachurus symmetricus, Cilus gilberti, and Scartichthys viridis—and comprise seven individuals (MNI; Supplemental Table 2). These were all recorded in shell middens 3 and 5. The presence of a right mandible of a camelid, most likely the wild guanaco (Lama guanicoe) in shell midden 8, occurs in the absence of any other skeletal parts, suggesting its transport from elsewhere. Finally, some unidentified carbonized seeds were found in shell middens 3, 4, and 8.

There is minimal evidence of lithic material from the shell middens, and in the great majority of cases, it represents debitage from the lithic reduction of locally procured toolstones. The presence of at least one small lithic weight suggests fishing using hook-and-line technology.

The intensive gathering of machas was probably due to their great abundance, high predictability, and ease of collection in an area close to the site. Intensive and preferential exploitation of this species, despite the availability of diverse species as indicated by other sampled sites in the environs, suggests that it was processed possibly for consumption elsewhere (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Báez and Vargas1995; Méndez Reference Méndez2002; Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020). Considering the excavated volume, a gross estimate of the total number of specimens in the site is about 8,200 individuals (MNI). Although this species has a relatively low biomass, it is the easiest to collect, perhaps even by nonspecialists and children. Its edible part is relatively simply to smoke-dry for preservation. It is most likely that each shell midden corresponds to a unique harvest event. However, larger middens, namely middens 3 and 11, may either represent the involvement of a larger number of individuals in the activity or more than a single event being deposited faster than the sedimentation rate.

Features: Hearths and Distinctive Surfaces

All the recorded hearths are simple and small fireplaces: either flat features lying directly on the sand or dug down only a few centimeters (Table 3). Thus, they have no distinctive structure (Figure 2e). Their diameters range from 22 to 75 cm, and their shapes are highly variable. Only hearth I showed a tenuous structure suggestive of a more prolonged use. In three cases, hearths were associated with shell remains, including burnt specimens of Concholepas concholepas. Nine of the 11 hearths (III–XI) are located toward the periphery of the archaeological distribution to the south and to the east of the site. Hearths I and II are the only ones located at the center of the site and are associated with a distinctive surface and shell midden 1, respectively.

Table 3. Formal Characteristics of Hearths and their Associations at Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007).

Note: ND: no data.

The excavation of trench 4, located toward the west of the site on an area devoid of superficial evidence, revealed the presence of a distinctive 1–3 mm thick buried surface. The greater compaction and darker color of the sediment were evidence of a continuous surface that formed a minor depression, which reached a maximum depth of 30 cm at the center of the trench, gradually diminishing toward the west and east (Figure 5a). The profile of this distinctive surface suggests a slightly excavated area along a 4.25 m axis. Additionally, the north–south profile of this trench showed an inclined feature at the base of the surface, resembling a buried post mold (Figure 5b). A few charcoal particles, small fish bones, two flakes, one pebble stone, and fire-cracked rocks, possibly resulting from an undetermined combustion structure, were recorded on this surface. One of these fire-cracked rocks yielded a thermoluminescence age of 2550 ± 200 BP (UCTL-1706). Adjacent excavation trenches also produced fire-cracked rocks, one core, a hammerstone, and a flake, which suggest minor lithic knapping close to this area.

Figure 5. Excavated cross sections of trench 4: (a) north profile showing distinctive buried surface and location of findings and (b) west profile showing distinctive buried surface and post mold feature. (Color online)

This distinctive surface has been preliminarily interpreted as the occupational floor of a dwelling space. It must have been a lightweight organic construction using perishable fibers, such as those from aquatic plants of local availability. These light, short-duration dwellings are consistent with high residential mobility and short occupational periods of small social units (Binford Reference Binford1990; Smith Reference Smith2003).

Interpretation of Activity Areas and Hearth Distribution

Three distinctive activity areas were defined based on the location of shell middens, site features, and the distribution of material remains (Figure 6). The activity areas enclose semicircular spaces bounded by shell middens and hearths in characteristic “clean” shallow depressions that yielded only dispersed lithic material. The central position of these clean areas suggests that activities most likely took place within them, whereas shell refuse accumulation and most burning took place on the periphery. Material remains and the distribution of features suggest activities including food preparation; lithic reduction, use, and discard; and possibly the drying of machas.

Figure 6. Interpreted site plan of Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007). (Color online)

Activity area A to the northeast of the site covers ~90 m2 and is the largest area. It is bounded by six shell middens (1–6), which form a semicircle oriented toward the south. Adjacent to shell midden 1, the remains of a hearth (II) were recorded. Additionally, beneath shell midden 6, a small hearth (III) was observed. Stratigraphic superposition of the shell middens and hearths suggests that this area formed during independent events. Shell middens 2 and 5, as well as hearth III, appear at the base of the sequence. Shell midden 3 lies on top of shell middens 2 and 5, and shell midden 4 rests on top of all three. One shell sample from shell midden 4 yielded a radiocarbon date of 3560 ± 35 BP (OS-63180; marine shell; δ13C = 1.3‰; Carré et al. Reference Carré, Jackson, Maldonado, Chase and Sachs2016). It provides a calibrated age of 2950–3530 cal BP that postdates the initial depositional events, although given the discrete nature of these middens, this temporal difference is not necessarily large. Two additional hearths, IV and V, are found to the northeast of this area at 2.5 m and 4 m from the shell middens, respectively. At least three of the shell middens show combustion activities suggestive of food preparation, as indicated by dispersed charcoal particles and the presence of occasional fire marks on shells and bones. This activity area also yielded lithic material, including debitage, bifacial tools, scrapers, milling stones, bored pebbles, and fishing weights. The conjunction of features—the hearths, middens, and the distinctive surface—and the higher frequency and density of the material remains suggest that this was the most-used area in the site.

Activity area B extends over ~74 m2 and is surrounded by shell middens 7–10. Only hearth VI was recorded between shell middens 8 and 9. Flanked by shell middens 9 and 10, excavations revealed an isolated flaking area of a single nodule that produced a core and some conjoining flakes, including one that was marginally retouched into a scraper. Conjoining of lithic materials is indicative of a high-resolution, short-span context with a low incidence of postdepositional alterations. This activity area, although containing less material than area A, yielded retouched artifacts, milling stones, flaked pebbles, and dispersed lithic debitage as well.

Activity area C is located at the southern part of the site and is bounded by four shell middens (11–14), one of which is a few meters farther away than the rest. Together with the three closer shell middens (11–13), they enclose an area of ~75 m2. Shell middens also form a semicircle oriented toward the southwest. Lithic remains are not well represented and only by fractured pebbles, flakes, and debitage. A charcoal sample from shell midden 11 yielded a radiocarbon date of 3090 ± 40 BP (OS-60569; charcoal; δ13C = −25.3‰; 3140–3370 cal BP; Carré et al. Reference Carré, Jackson, Maldonado, Chase and Sachs2016). Six meters southeast of this area, five hearths (VII–XI) are set in a curved pattern; they are located at an equivalent distance to the south of area B. The closeness of these hearths to each other and to the activity areas strongly suggests a functional association. Additionally, their depth and stratigraphic position indicate a relative contemporaneity between them and the activity areas.

Small open-air hearths with no major associations are difficult to interpret. However, their location along the periphery of the site, their relative closeness to each other and to the activity areas where preferentially machas were processed, and the absence or low frequency of other remains suggest that these hearths may have been used to smoke-dry the mollusks. Smoke-drying would have preserved them for delayed consumption, a practice known ethnographically for numerous hunter-gatherer-fishers in the Americas (Waselkov Reference Waselkov1987). It is important to note that drying for delayed consumption of the machas has also been documented in different regions along the Pacific coast of Peru and Chile (Sandweiss et al. Reference Sandweiss, Asunción Cano and Roque1999). This bivalve is boiled or dried, either hung or extended, and transported in lightweight containers to be consumed later (Daniel Sandweiss, personal communication 2019). In the area of Camaná (southernmost Peru), modern data indicate that this process is seasonal, involves minimal technology for processing and carrying, and is performed by nonspecialists, including nonlocal gatherers, who are able to obtain up to a daily yield of 50 kg per person (Masuda Reference Masuda and Mazuda1981).

Discussion

A hollow depression between dunes that provided wind protection and a circumscribed space was selected as the area for the campsite at Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007). Mainly domestic activities took place there, which included mollusk processing, food preparation of these and other coastal produce, and lithic reduction, use, and discard. The low frequency of material evidence indicates low-intensity activities that most likely occurred during a brief period. These occurred around a dwelling area, suggesting the residential character of the site. Dates on marine shell from shell midden 4 (3530–2950 cal BP) in area A and from charcoal shell midden 11 (3370–3140 cal BP) in area C provide overlapping calibrated age intervals (either 1σ or 2σ). These are close in range to a less precise thermoluminescence age on a fire-cracked rock from the proposed dwelling space. Thus, the age distribution is suggestive of a single occupation. However, the stratigraphic superposition of shell middens and other features is consistent with some degree of site redundancy, although we regard it as minor. Area A was the most intensively and redundantly used and seems to have been the foundational point from which later occupations structured campsite organization. No superposition of middens and hearths was recorded in areas B and C.

At LV 007, midden formation implied the intensive collection of machas, with a frequency of more than 81%. The total estimate of the number of Mesodesma donacium based on the excavated samples is about 8,200 specimens. This preference attests to this species’ great abundance, density, and predictability on the sandy beach located 1.2 km from the site, the most likely location for gathering. This species has a low biomass and low protein content per individual; however, its insubstantial dietary contribution was compensated for by its abundance and low collection costs, even potentially by gatherers of different ages. A few harvest days may have provided important quantities of this mollusk, which is consistent with the processing of unique resources typically involved in short stays (Smith Reference Smith2003). Each midden was possibly the result of a unique collection event. If this was the case, then the number of shell middens could indicate an approximate number of days for site occupation, although it is likely that more than one shell midden could have been formed per day, depending on the number of collectors involved in the harvest. Given the limited evidence for other foods (fish = seven individuals; guanaco = one part of one individual) and the few lithic artifacts, the occupation may have lasted only a few days.

The presence of other gastropods, echinoderms, and crustaceans suggests a relatively minor contribution of food gathering on intertidal rocky shores, possibly during low tides. The small mussel Perumytilus purpuratus is often a byproduct of algae collection; however, other small gastropods (e.g., Tegula tridentata, Prisogaster niger, Diloma nigerrina, and Acanthina monodon) require individual extraction, thus suggesting they were nonoptimal targets. The high frequencies of Diloma nigerrina (10.33%) in shell midden 4 and of Acanthina monodon (46.16%) in shell midden 8 are noteworthy. Such choices suggest the active presence of children in gathering activities, as has been proposed for other archaeological contexts in the region, as well as by ethnoarchaeological data from Australian coastal groups (Bird and Bliege Bird Reference Bird and Bird2000; Méndez and Jackson Reference Méndez and Jackson2004; Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020).

The presence of small, simple hearths lacking any structure or distinctive association with food or other material remains and located toward the periphery of the site and close to the activity areas suggests a functional association with those areas. Based on the mollusk selection preferences, we argue that such hearths may have been used for smoke-drying machas, given their potential for short-term storage (Smith Reference Smith2003). Dried machas may have been carried in lightweight containers out of the campsite, allowing a surplus to buffer the possibility of unstable resources in areas distant from the coast where less predictable resources were expected. Other sites in the area with preferential selection of machas are Punta Penitente (LV 014), Quebrada Lazareto (LV 089), and Pichidangui (LV 531, LV 533; Ballester et al. Reference Ballester, Donald Jackson, Antonio Maldonado and Seguel2012; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, César Méndez, Jackson and Seguel2005; Méndez Reference Méndez2002). These are all single-species (Mesodesma donacium) middens with ages between 9700 and 8300 cal BP, yet none have been observed in association with dwelling structures or hearths (Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020). However, south of the dune system, a field-processing site at Punta Chungo (LV 039) and a residential site at Fundo de Agua Amarilla (LV 099b) yielded frequencies of machas exceeding 93% of the molluscan assemblages in an overlapping range between 520 and 230 cal BP (Massone and Jackson Reference Massone and Jackson1994; Troncoso et al. Reference Troncoso, Cristian Becker, Paola González and Solervicens2009). In this case, the contexts suggest intensified gathering for transporting dried coastal resources inland where a much more stable settlement has been suggested (Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020; Seguel et al. Reference Seguel, Jackson, Rodríguez, Báez, Novoa and Henríquez1994).

In Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007), the dwelling space is represented by the subtle traces of a slightly excavated semicircular floor, most likely made of perishable materials. One additional 7500 cal BP site within the dune system (LV 166) also shows areas free of residue bounded by shell middens and was earlier interpreted as a residential site with a central dwelling space (Jackson Reference Jackson2004). Lightweight tents or windbreaks would be expected for hunter-gatherers with high residential mobility in short-span occupations, where the energy invested and the costs of maintenance are minimum (Binford Reference Binford1990; McGuire and Schiffer Reference McGuire and Schiffer1983; Smith Reference Smith2003). The small size for the proposed dwelling implies a small number of site occupants, most likely a family unit.

The evidence from other sites dated between 5300 and 2300 cal BP on the coast of Los Vilos supports a highly mobile residential pattern preferentially along the coast (Méndez and Jackson Reference Méndez and Jackson2004, Reference Méndez and Jackson2006; Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020). Among these sites, eight are dated shell middens in which marine invertebrates constitute a principal sedimentary particle in thick and dense charcoal-rich middens where their processing is observed alongside hearth features, fire-cracked rocks, and lithic and bone material (Jackson and Méndez Reference Jackson and Méndez2005; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Báez and Arata2004; Méndez Reference Méndez2002). These highly diverse malacological assemblages show fragmented and burnt evidence as a result of intrasite activities and possible trampling (Méndez and Jackson Reference Méndez and Jackson2004). LV 007 differs from these dense middens and adds variability to the archaeological record of the period between 5300 and 2300 cal BP. As a small camp with ephemeral architecture located far away from the coastline, its faunal evidence indicates the transport of specific resources from procurement locations. The spatial distribution of the shell middens and features reveals a spatial organization otherwise unseen at sites of the same age. As such, this site may be considered as a logistical camp where key resources were processed; in this case, dried for delayed consumption (Binford Reference Binford1980:8). This variability is expected for a period in which increased archaeological deposition suggests a more sustained human presence along the coast (Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020). Additionally, the interpretation of mollusks being processed for delayed consumption has not been suggested for other contemporaneous sites in the area and further implies that resources were transported elsewhere, most likely inland. This agrees with current radiocarbon evidence suggesting an increase in records of human occupation in the El Mauro valley, 45 km inland, at about 3000 cal BP (Gómez and Pacheco Reference Gómez and Pacheco2016; López-Mendoza et al. Reference López-Mendoza, Isabel Cartajena, Daniela Villalón and Rivera2016). In this way, given the predictability of resources in coastal environments, these sites may have provided a buffer during relatively dry periods, such as between 3800 and 2700 cal BP when regional climate variability produced stress on resources (Maldonado and Villagrán Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2002, Reference Maldonado and Villagrán2006).

Conclusion

The Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007) site may be defined as a small, short-span residential campsite, as indicated by the limited diversity of activities conducted within it and by the small accumulation of refuse over few repeated occupational events. Its targeting of one single, easy-to-obtain, invertebrate resource, the macha, which was available within 1.2 km of the settlement, underscores the knowledge of the distribution and predictability of marine resources by populations long adapted to this coast. Campsites between 5300 and 2300 cal BP in the area were characterized by brief occupational events framed within a pattern of littoral residential mobility in which predictable coastal resources became a staple for groups residing over long periods in the area (Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay Reference Méndez and Nuevo-Delaunay2020).

Shell middens, especially those with few cultural remains, may be uncritically seen as mere processing areas (Gamble Reference Gamble2017). However, detailed excavations may provide evidence revealing a more complex picture, in which the distribution of features, degrees of redundancy, and the diversity of activities, or lack thereof, may be informative of the characteristics of site planning. In this sense, shell middens, as well as other small features, may indicate a structural and functional complexity that cannot be reduced to serving only as refuse dumps resulting from the exploitation of marine resources. As such, they have the potential to reveal meaningful associations that may increase our understanding of hunter-gatherer site planning and decision making.

Acknowledgments

This investigation reported in this study was funded by the National Geographic Society grant 8122-06, ANID-FONDECYT 1170408, and Programa CONICYT Regional R17A10002. We owe the design of this research and his contribution to an earlier version of the article to the late Donald Jackson. He conducted the excavation, planned the methodology, and provided an initial interpretation of the site context. We are enormously indebted to his contribution and leadership. We acknowledge Daniel Sandweiss for his observations on macha gathering and processing, Fernanda Falabella for providing us with the modern shell sample from Pullalli, Jimena Torres for taxonomical determinations of fish, Canek Jackson for mollusk quantification, César Miranda and Gregorio Calvo for field assistance, Paulina Chávez for help with some of the figures, and Amalia Nuevo Delaunay for her help in various stages of preparing this article.

Data Availability Statement

All specimens in this study are curated in the Anthropology Department, Universidad de Chile (Capitán Ignacio Carrera Pinto 1045, Ñuñoa, Santiago, 7800284, Chile). They are available after consultation with the collection curator: http://www.facso.uchile.cl/antropologia/patrimonio/55923/colecciones-de-antropologia.

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.60.

Supplementary Figure 1: Context images of the excavations at Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007): (a) shell midden distribution, (b) location of the excavations (northern trench), (c) excavation of unit 2, (d) excavation of unit 3.

Supplementary Table 1: Absolute frequency of mollusk remains (MNI) from sampled shell middens (SM) and the percentage of Mesodesma donacium in each sample.

Supplementary Table 2: NISP and MNI for fish remains recorded at Dunas de Agua Amarilla (LV 007).