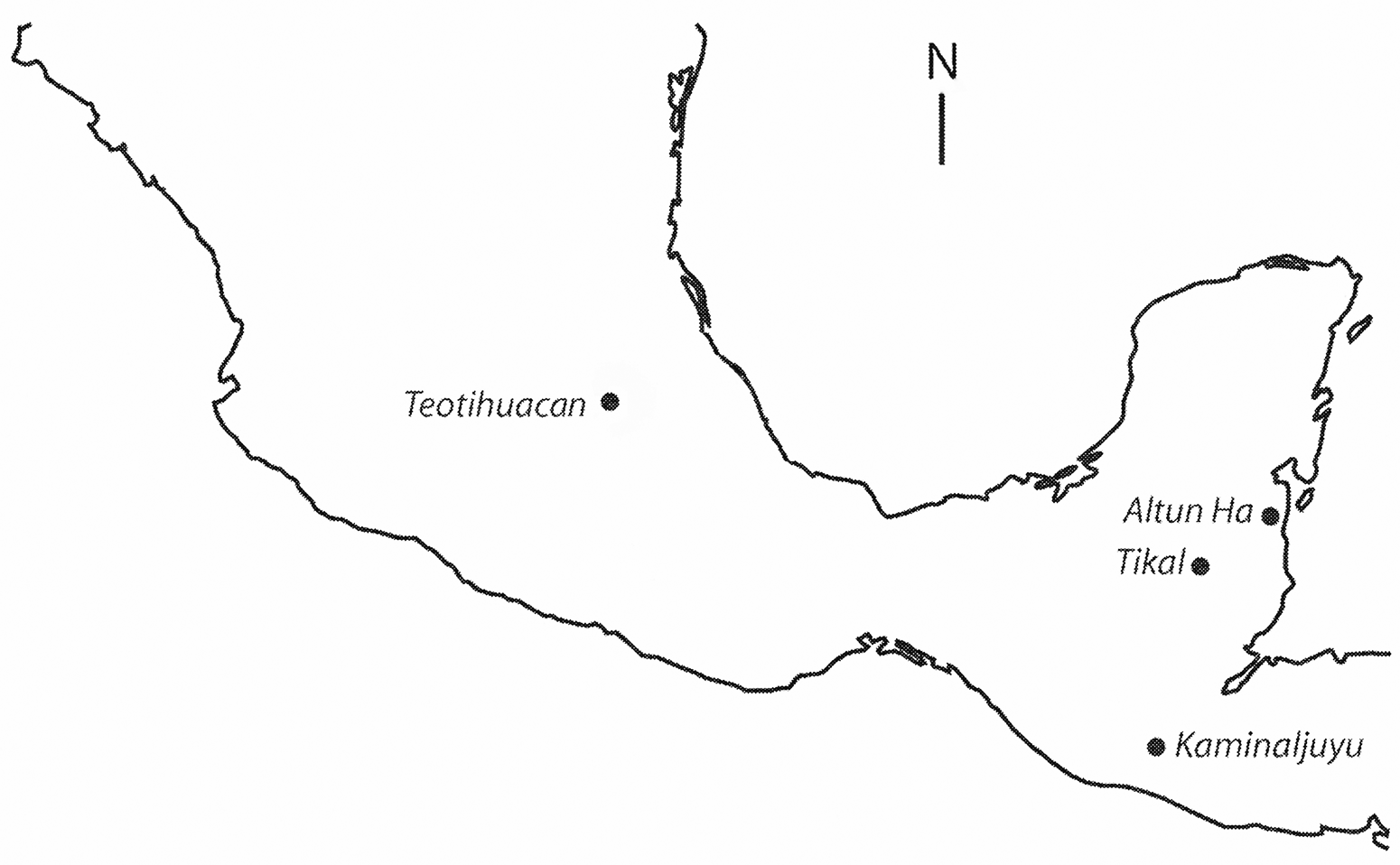

In the summer of 1959 Problematical Deposit 50 (PD 50) was excavated by Stuart D. Scott of the Tikal Project of the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Since then, PD 50 continues to be referenced in the literature because of an extraordinary pottery vessel found in it, nicknamed here the “Arrival Bowl.” Both the vessel and the PD bear on the ongoing debate about the nature of contacts between the Maya area and the Central Mexican polity of Teotihuacan (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Mesoamerica. Tikal is about 1,026 air-km southeast of Teotihuacan (map by the author).

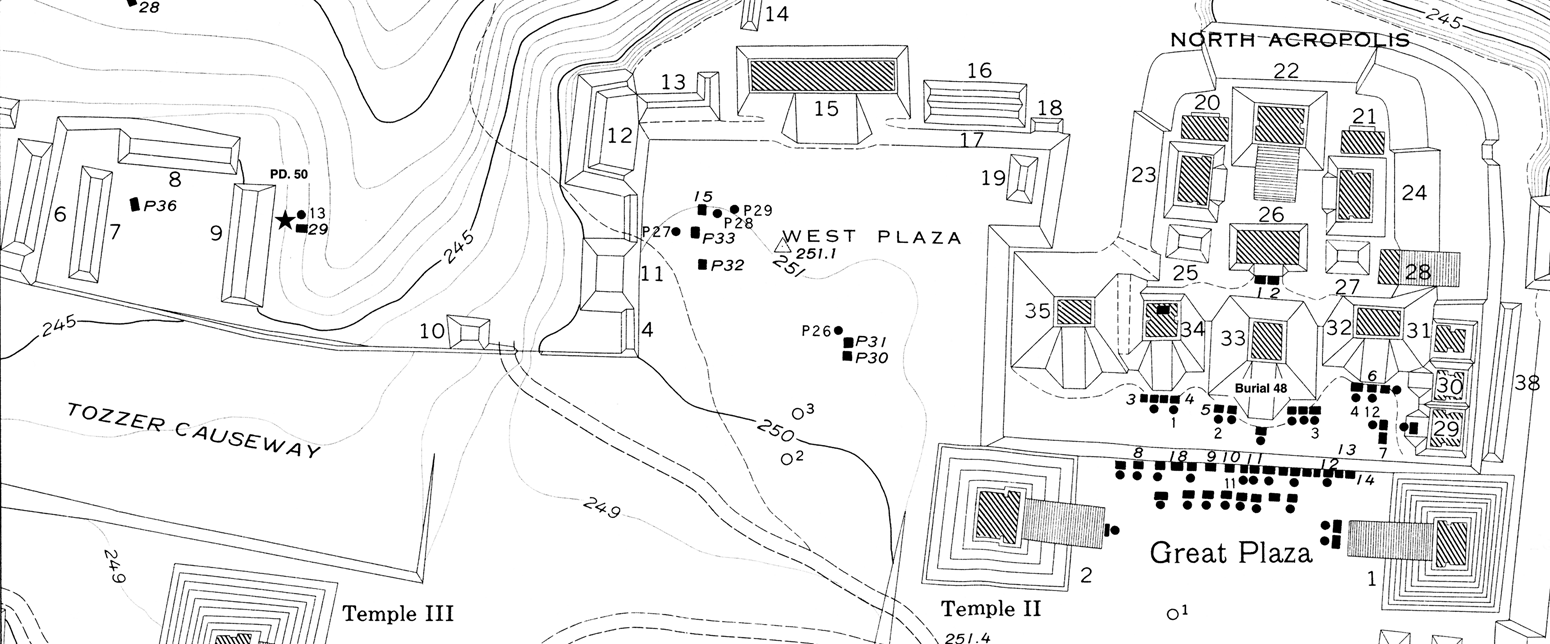

PD 50 came to light during the course of Scott's exploratory excavations in the vicinity of Stela 29 (Figure 2), which is noteworthy for its carved Initial Series date corresponding to AD 292, still the earliest known in the Southern Maya Lowlands (Shook Reference Shook1960). The scene on the carved-incised bowl appears to depict a meeting of Mayas and Teotihuacanos (Figures 3–5; Greene and Moholy-Nagy Reference Greene and Moholy-Nagy1966). Scott's excavations remain unpublished, and no author has been assigned to them. This article reports on what is known about the material contents and archaeological context of PD 50 and offers some speculations about what this feature might indicate about Maya–Teotihuacan relationships during the Early Classic period.

Figure 2. Location of Problematical Deposit 50, approximately 260 m west of the center of the North Acropolis of Group 5D-2, Tikal's epicenter (Carr and Hazard Reference Carr and Hazard1961, reprinted with permission from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology).

Figure 3. The Arrival Bowl from PD 50 after mending (screenshot from Tikal Project 1960 #1, Penn Museum, reprinted with permission from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology).

Figure 4. Drawing of the Arrival Bowl from PD 50. The vessel is 15 cm tall (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figure 128a, reprinted with permission from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology).

Figure 5. Figure G from the Arrival Bowl. Note the differential weathering (Greene and Moholy-Nagy Reference Greene and Moholy-Nagy1966:Figure 2, reprinted with permission from American Antiquity).

A description of the archaeological context of the Arrival Bowl can enhance its explanatory potential. PD 50 can be linked to events that took place at Tikal and in the Maya area in the middle and late Early Classic period, during the time of the Manik 3 ceramic complex (AD 380–550; Culbert and Kosakowsky Reference Culbert and Kosakowsky2019:Table 1.3). Manik 3 is thought to be approximately contemporary with Teotihuacan's Early Xolalpan phase (AD 350–450), when that polity reached its zenith in power and geographical extent of influence (Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015:140, Table 1.1). Goods and iconography of Teotihuacan origin or inspiration reached their maximum expression at Tikal at that time, especially during the Manik 3A ceramic complex (AD 380–475).

Table 1. Comparison of Problematical Deposit 50 and Burial 48.

a Coe Reference Coe1990:118–123.

b Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008.

c Moholy-Nagy 2003b.

d Culbert 1993.

We are gradually achieving a better understanding of this period and its turbulent end through archaeological and physico-chemical analyses, as well as epigraphic and iconographic research. Generally, iconography and epigraphy tend to support hypotheses of an imposition of Teotihuacan influence through an incursion into the Southern Maya Lowlands referred to as the entrada. In contrast, archaeological and instrument analyses tend to support local ideological emulation and adaptation over a longer period of time, which could have been inspired and reinforced by intermittent contacts with Teotihuacanos (e.g., Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Auld-Thomas, Arredondo, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020; Iglesias Reference Iglesias Ponce de León2008; Millon Reference Millon and Berrin1988; Pendergast Reference Pendergast and Braswell2003; Stanton Reference Stanton2005; Stuart Reference Stuart, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000; Varela and Braswell Reference Varela Torrecilla, Braswell and Braswell2003).

Recovery Context

PD 50 was excavated during the early years of the Tikal Project. At the time its significance was not fully appreciated, and it was not recorded in detail. The sources I consulted include Stuart Scott's field notes (Reference Scott1959), information recorded in the field on lot cards and object catalog cards, William A. Haviland's notes on the human remains (William A. Haviland and Janet Monge, personal communication 2019), Tikal Report 25A on the pottery vessels from special deposits (Culbert Reference Culbert1993), Lisa Ferree's dissertation (Reference Ferree1972) on Tikal censers, and Tikal Reports 27A and 27B on most of the other portable artifacts (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy and Sabloff2003a, Reference Moholy-Nagy2003b; Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008).

Location

Scott's excavations in the PD 50 area were prompted by the exciting discovery of Stela 29, a large fragment of a carved stone monument with an Initial Series date equivalent to AD 292, which was near the beginning of the Early Classic period (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:61–62, Figures 49a, b and 103a, b; Shook Reference Shook1960). Nearby was Altar 13, a fragment of a stone altar carved in Early Classic style but without a date (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:80, Figures 60a–c). PD 50 was found somewhat to the west of these broken and relocated monuments and might have been placed at the same time. The two monument fragments and PD 50 are approximately 260 m directly west of the center of the North Acropolis of Group 5D-2 and a few meters east of Structure 5D-9 of Group 5D-1, an unexcavated group of range structures (Figure 2). There are no data on possible stratigraphic relationships among the monument fragments, PD 50, or Structure Group 5D-1. The absence of architecture or other features suggests that the area was used as a dump during the Classic period (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:61).

Repository

In his explorations of the area around Stela 29, Scott encountered a few jade beads, burned bone fragments, and a tripod metate fragment about 70 cm beneath the ground surface. These materials turned out to be the uppermost fill of a large deposit of broken and burned pottery vessels, human remains, and artifacts of stone, shell, and bone jumbled together in a large pit of unrecorded dimensions, which had been excavated into bedrock. The feature was first designated Burial 9. When it became evident that it did not conform to standard Tikal mortuary practice it was reclassified as PD 50.

Recorded Contents and Arrangement

The bedrock pit was completely excavated from east to west. The contents were deposited without any discernible arrangement in a fill of soft black soil. Scott observed that there were only a few fragmentary human bones and teeth. Most of the larger bone fragments were found lying on the floor of the bedrock pit.

Remnants of a standard Tikal cache offering of the Acach offertory complex (Begel Reference Begel2020:343–348; Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008:18) were recovered, which included a set of broken lidded cylindrical and flaring-sided cache vessels (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figure 130). Most of the jade beads and two small pearl bead pendants had been placed inside the cylindrical cache vessels (Table 1). Bivalve and univalve marine shells were found in the western part of the deposit. In contrast to the burned and splintered condition of most of the human bones, Scott reported a small, saucer-like pottery bowl, scorched on one side, which contained a large fragment of an unburned, unspecified human longbone. The small, scorched vessel had been placed inside a thick-walled unburned bowl. I was not able to identify either of these vessels in Culbert's (Reference Culbert1993) ceramics report. Scott (Reference Scott1959:145) mentioned several incised, calcined whitetail deer phalanges. He did not state whether the pit itself was burned, but the condition and juxtapositions of the contents indicate that they were smashed and burned elsewhere before some of the objects were taken away and dumped into the pit to form PD 50. This kind of treatment is a stark contrast to the usually complete condition and patterned arrangement of the contents of standard Tikal burials and caches (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2020:48).

Some of the contents of PD 50 closely resembled those of Burial 48, which imply approximate contemporaneity (Table 1; Coe Reference Coe1990:118–123; Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 28–32; Shook and Kidder Reference Shook and Kidder1961) and identify the social rank, gender, and ethnicity of its subject. Burial 48 is a chamber burial below Structure 5D-33 in the epicenter of Tikal (Figure 2). Because of its size and the richness of its contents, it is assumed to be the grave of a powerful ruler of Tikal, Sihyaj Chan K'awiil II. An Initial Series date equivalent to AD 456 painted on the north wall of the bedrock chamber is widely accepted as the date of his death (Coe Reference Coe1990:Figure 175; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:35–36). Apparently only adult males were accorded chamber burials at Tikal during the Classic period (Begel Reference Begel2020:Table VIII.3a–c; Coe Reference Coe1990). The principal of Burial 48 had been given the standard Tikal Classic period chamber grave and offerings. Among the offerings were two subadult attendants of undetermined sex, fine pottery vessels, many ornaments of greenstone and Spondylus shell, and an Acach Complex cache. Tikal Classic period chamber burials and cached offerings are distinguished by distinctive material assemblages, together with several kinds of goods that occur regularly in both contexts. The offerings interred in Burial 48 include fine pottery vessels and sets of elaborate personal ornaments of stone and shell, which occur only rarly in cached offerings. Caches, in turn, are characterized by ceremonial lithics, specialized pottery containers, and unworked marine shells and other invertebrates (Begel Reference Begel2020; Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2020; Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008).

Among the most interesting similarities between PD 50 and Burial 48 was the inclusion in each of a set of worked and unworked deer phalanges (Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008:Figure 215n) and a tripod metate and mano set of vesicular basalt (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2003b:Figures 74a, b). Tripod metate and mano sets, a utilitarian artifact type introduced into the Maya area from Highland Mexico during the Early Classic period, were included among the Teotihuacan-style grave offerings in all but two of the Early Classic burials in Mounds A and B at Kaminaljuyu. Virtually all were of vesicular basalt (Kidder et al. Reference Kidder, Jennings and Shook1946:140, Figure 158).

The goods and human remains deposited in PD 50 conform to the program of standard elite Tikal burials, rather than standard cached offerings (Table 1; Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2020:48). The original chamber burial was exhumed, and its contents were smashed, burned, and scattered. Some were carried to another location, dumped into a pit, and reburied to form PD 50. The location of the original repository and other contents is unknown.

Human Remains

In a preliminary examination William Haviland attributed the recovered fragmentary, partly burned human bones and teeth to four children and one subadult (William A. Haviland and Janet Monge, personal communication 2019). This finding suggests that only the sacrificed attendants are represented in PD 50 and that the principal subject lies elsewhere, perhaps with the rest of the contents of his destroyed grave.

The charred condition of some of the human remains first led me to the conclusion that PD 50 was the primary cremation burial of a high-ranking person from Teotihuacan. This notion seemed plausible at the time, but advances in knowledge now make it untenable. Although investigations conducted at Tikal by other project teams have defined some special deposits containing burnt human remains as burials (e.g., Chinchilla Mazariegos and Gómez Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos, Gómez, Arroyo, Linares and Paiz Aragón2010), their contexts and arrangements differ markedly from the standard burial pattern of Tikal, which was inhumation of a single principal individual (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2020:48). The Tikal Project would have designated the burnt deposits as problematical.

Comparison with the burials, caches, and problematical deposits recovered by the Tikal Project indicates that PD 50 includes the remnants of a demolished elite burial. It can be characterized as a desecratory termination deposit (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Kathryn Brown and Pagliaro2008:235), inasmuch as there does not appear to have been any reverential intent in the behavior that created this feature. The materials that can be attributed to the original burial conform to the standard elite mortuary program of Classic Period Tikal, which suggests that the principal of this interment was of local origin. Yet Lori Wright was able to establish significant migration to Tikal from other parts of the Maya area, particularly during the Early Classic period (Scherer and Wright Reference Scherer, Wright and Cucina2015; Wright Reference Wright2002, Reference Wright2005, Reference Wright2012), so a nonlocal origin remains a possibility.

Pottery Vessels

Nearly all of the ceramic offerings were broken and incomplete. Some display the eclectic style that characterizes many of the serving vessels of the Manik 3A ceramic complex; that is, their shapes are copied from the cylindrical tripod bowls and jars and round-side bowls in use at Teotihuacan, but their decorative motifs incorporate Maya stylistic traits (Figures 3–7; Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer, Englehardt and Carrasco2019). Thirty-six serving vessels and cache containers were cataloged from PD 50 (Table 1). Culbert illustrates 33 vessels in his Tikal Report on the ceramics from special deposits (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 128–130). The cataloged vessels include five Aguila Orange flaring-sided cache bowls; nine Balanza Black cylindrical cache vessels and seven lids; a two-part hourglass censer and an incomplete ladle censer; a Dos Arroyos Orange Polychrome basal flange bowl; a miniature Aguila Orange dish or cover; a Quintal Unslipped miniature jar; four Aguila Orange round-sided bowls, two with tripod feet and two on low ringstand bases; an Aguila Orange cover or plate; an Aguila Orange jar with a tall neck and everted rim; and four atypical, possibly imported cylindrical tripod bowls.

One of the cylindrical tripods is undecorated (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figure 129b), and one has an incised step-fret band around the base (Figure 129a). The other two are once-magnificent examples of Maya display ceramics. The better-known vessel is the Arrival Bowl (Figures 3–5; Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figure 128a). The other bowl is decorated with a striking incised design of two entwined rattlesnakes, the kind of serpent often depicted at Teotihuacan (Figure 6; Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figure 128b).

Figure 6. The Snake Bowl from PD 50. The vessel is 14.4 cm tall (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figure 128b, reprinted with permission from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology).

Other Artifacts and Unworked Materials

A remarkable aspect of the assemblage of stone and shell offerings from PD 50 is the absence of the large or highly crafted ornaments found with undisturbed Tikal chamber burials, including the earlier mentioned Burial 48. The burial that became PD 50 was plundered as well as desecrated. Destruction of carved stone monuments, caches, and burials associated with the rulers and upper ranks of Tikal society can be observed in the archaeology throughout Tikal's occupation, although it is especially evident during the Early Classic to Late Classic transition (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2016:Figure 5). This kind of targeted damage has been tentatively attributed to rival elite factions (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Guernsey, Arroyo, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:23; Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2016:259). The most highly crafted ornaments of jade and Spondylus shell, as well as minor sculptures of stone, may have been reinterred in chamber burials and temple caches, suggested by the presence of minor sculptures and ornaments of styles earlier than the deposits in which they occur; for example, the Late Preclassic objects in Early Classic and Late Classic special deposits (Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008:Figures 103e, 144a’, 144a”) and those of Early Classic style included in Late Classic chamber burials (Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008:Figures 108c, 109c). These may also have been taken off-site as gifts, trade goods, tribute, or keepsakes (Begel Reference Begel2020:515).

The contents, arrangement, and recovery context of PD 50 closely resemble a group of 17 PDs from Tikal temporarily classified as Subtype 43-3 and thought to be the remnants of desecrated and relocated burials of the elite and well-to-do because of their included markers of high status (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2020:56–57). All examples of Subtype 43-3 PDs contained significant amounts of household trash and durable production debitage of stone, shell, and bone, and all showed some degree of burning. Although they occurred sporadically from Preclassic into Terminal Classic times, nine, or a little more than half of the sample, had been deposited during the middle and late Early Classic period. The PDs in this group of nine included burial offerings in eclectic Teotihuacan-Maya style, including two large pieces of a stone monument, Stela 32 (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2020:Figure 7), carved with the head of a man wearing a tasseled headdress (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:Figure 55a). PD 50 was given a different subtype, 43-4, because of an apparent absence of household trash or debitage. Yet a closer look at the contents listed in Table 1 indicates that some household midden material was probably added when PD 50 was formed, such as the large number of incomplete pottery vessels (19+) that are neither cache vessels nor censers, the quartzite mano fragment, and the perforated dolomite disk. The contents of PD 50 share traits with general excavations, elite Chamber Burial 48, and Subtype 43-3 problematical deposits (Table 1).

Figure 7. A fine example of an eclectic “international style.” The shape and monochrome black surface of the vessel were inspired by Teotihuacan, but the gouged-incised decoration and modeled handle are Maya. From Burial 48, Manik 3A Ceramic Complex. The jar without the lid is 16.6 cm tall (Coe Reference Coe1965:28, reprinted with permission from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology).

Date

The original burial, the source of PD 50, was interred during the time the Manik 3A ceramic complex was in use, around AD 380–475 (Coggins Reference Coggins1975; Culbert and Kosakowsky Reference Culbert and Kosakowsky2019). A somewhat more precise date of around AD 450 is suggested by the close resemblance of its contents to those of Burial 48.

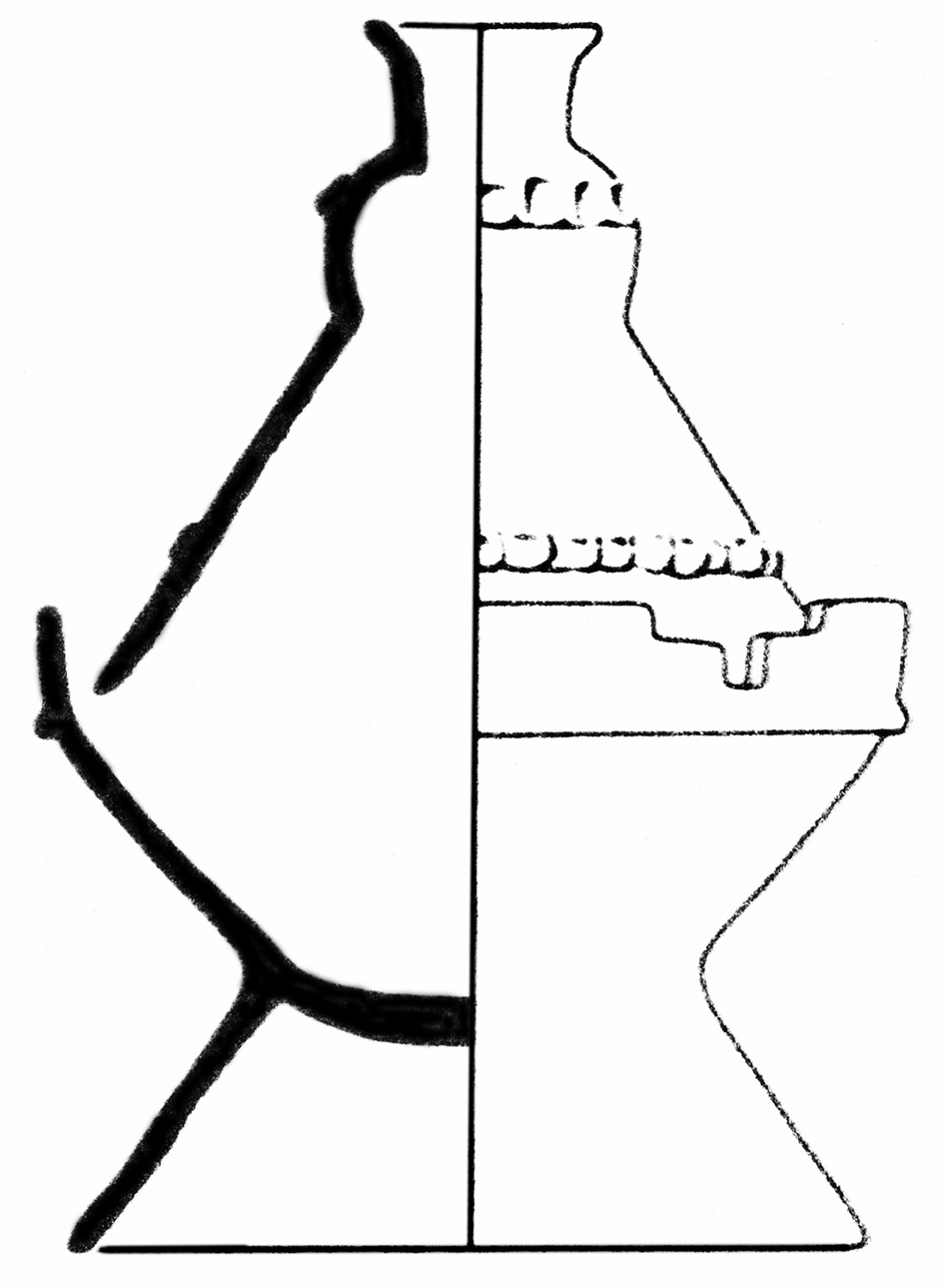

Sherds from general excavations in the vicinity of the deposit ranged from the Late Preclassic through Late Classic periods. In the absence of directly associated architecture or in situ carved monuments, a date for the deposition of PD 50 is suggested by the two included censers, under the currently unverifiable assumption that the original burial was dislocated and redeposited only once. Censers were never included in Tikal standard burials, and Ferree (Reference Ferree1972:5) suggested that those found in PD 50 might have been added when the feature was formed. Ferree assigns the hourglass censer (Figure 8) to the Late Kataan Complex, which was contemporary with Manik 3B (ca. AD 475–550). Therefore, the deposition of PD 50 might have occurred from 25 years to a century after the interment of the original burial.

Figure 8. Hourglass censer from PD 50. The height of the lower element is 16.3 cm (redrawn from Ferree Reference Ferree1972:Figure 8a).

The Arrival Bowl

The best-known artifact from PD 50 is a large, well-made, incomplete, cylindrical tripod pottery bowl (Figures 3–5). I refer to it here as the Arrival Bowl, because its carved-incised decoration appears to depict the welcomed arrival of a group of Teotihuacanos at a Maya settlement. The Teotihuacanos and Mayas can be readily distinguished from each other by their clothing, headdresses, and the objects they hold in their hands. All of the identifiable figures are adult males.

The Arrival Bowl is 15 cm tall and 34 cm in diameter and of an unnamed black monochrome ceramic type with an elaborate carved-incised scene. The bowl was broken, parts of it were burned, and not all of it ended up in PD 50. Its overall style can be described as eclectic. The cylindrical tripod form, shape of the tripod supports, and incised monochrome decoration were inspired by Teotihuacan, but the proportions of the vessel and style of the depictions are Maya. We intended to send the bowl to the United States for instrument analysis, but the shipment was stolen en route. However, the current assessment, based on its shape, large size, and style of decoration, is that it was probably made somewhere in the Maya Lowlands.

What makes this vessel extraordinary is the narrative content of its decoration, which depicts an actual or imagined event or series of events. Narrative scenes are uncommon on pottery vessels during the Early Classic period; at that time, similar scenes were more often found on murals and stone monuments. The scene is incomplete, and it is difficult to determine the beginning and ending points in the continuous design. No glyphs are present.

Three structures are shown (Figure 4). There is a probable Maya temple with a radial plan at 1 and a Teotihuacan temple at 3 with a talud-tablero platform. Structure 2 is of an eclectic architectural style that combines a talud-tablero platform with non-Teotihuacan stylistic traits. A seated figure is shown inside the structure, and a standard or marker of non-Maya style is set next to it. Robb (Reference Robb, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020:181) refers to this type of standard as a feathered banner, an artifact that symbolized Teotihuacan. The structure at 3 and the two figures at K and L may represent Teotihuacan. They are depicted with their knees raised in Central Mexican style, instead of flat in tailor fashion as in Maya style.

The two men look toward a procession of six Teotihuacanos at E through J. The first four are warriors armed with atlatls and darts. The last two wear a distinctive tasseled headdress, which may identify them as elite traders, envoys, or missionaries (Millon Reference Millon and Berrin1988; Nielsen and Helmke Reference Nielsen and Helmke2020:320–321; Paulinyi Reference Paulinyi2001). Each man holds a large, covered container. The procession of Teotihuacanos faces a man, apparently a Maya, who is standing on the steps of Structure 2. He wears an elaborate headdress and loincloth and holds a feathered object resembling a whisk, perhaps a marker of social rank. A similar artifact may be held by the individual inside Structure 2; other examples are shown in depictions of elite men on Late Classic Tikal pottery vessels (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 68a, 85b). The Maya appears to be welcoming the Teotihuacanos. Although armed warriors are depicted, the scene is peaceful (Marcus Reference Marcus and Braswell2003:339). Warriors may have been necessary to protect this delegation of elites if they traveled through contested territory.

The opposite end of the social scale may be represented by the individual at A, who is ascending the stairs of Structure 1. He appears to be a Maya. However, his lack of headdress and ear ornaments suggests he is of low social rank, perhaps even a captive (see Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008:Figures 200a, 200b). He is holding an unidentified object in his upraised hand. It is harder to guess at what is shown because of the missing areas between Structures 1 and 3 and Figures A and B.

The scene on this bowl is widely interpreted as depicting a meeting of Mayas and Teotihuacanos (Stuart Reference Stuart, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000), although the figure at A and the missing portions of the vessel suggest that other events may have been shown as well. The bowl may have been specially commissioned by its original owner to commemorate the peaceful arrival of a delegation from Teotihuacan. The eclectic architectural style of Structure 2 raises questions as to where in the Maya area this event is taking place. The talud-tablero platform might designate Tikal, which constructed several building platforms with talud-tablero facades in Group 5C-11 (the Mundo Perdido), Group 6E-2, and Group 6C-XVI (Laporte Reference Laporte Molina1989:133–141, Figures 48–55). Kaminaljuyu with its famous talud-tablero platforms would be equally likely (Arroyo Reference Arroyo, Hirth, Carballo and Arroyo2020:442; Kidder et al. Reference Kidder, Jennings and Shook1946:Figure 113).

The Materialization of Ideology

A significant impediment to understanding the function and meaning of the changes observed in the archaeological record during the middle Early Classic period is the lumping together of imported traits of material, style, and iconography without regard to the past systemic functions implied by their date, mode of use, or recovery context. The material indicators accepted as evidence of contact with Teotihuacan had both economic and ideological functions. Two intertwined aspects appear to be involved: a long-lived exchange interaction sphere that encompassed much of Mesoamerica at various times and a comparatively brief, more limited diffusion of a Teotihuacan-inspired ideology that it facilitated.

The overland, riverine, and coastal routes of the interaction sphere linked different regions from the Early Preclassic period or earlier to the Spanish conquest. Various kinds of materials were brought to Tikal from the time of its founding in the Middle Preclassic period until its abandonment at the end of the Terminal Classic period, from about 800 BC–AD 900; virtually only the durable components of these materials have survived.

Imported goods were recovered from all but the poorest and most peripheral residential structure groups. They are primarily of utilitarian function and were used in everyday activities in domestic settings (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2003b; Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008). However, some of these imports—notably, stemmed chert and obsidian dart points and tripod metate and mano sets—could also assume ritual functions. Their spatial contexts indicate marketplace distribution (Hirth Reference Hirth1998). They constitute socioeconomic indicators of contact and exchange from a potentially wide range of sources including, but not invariably, Teotihuacan. Economic contacts with Central Mexico via the interaction sphere brought green obsidian prismatic blades and blade cores and Pacific marine shells to Tikal during the Early Late Preclassic. Exchange with the Mexican and Guatemalan highlands during the course of the Early Classic period is indicated by tripod metate and mano sets of vesicular basalt, thin bifaces (stemmed dart points and laurel leaf knives) made of Central Mexican sources, and the use of molds for pottery figurines, censer ornaments, lid handles, and spindle whorls, all of which continued in domestic use until site abandonment (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy and Sabloff2003a; Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008; Moholy-Nagy et al. Reference Moholy-Nagy, James Meierhoff and Kestle2013).

The interaction sphere reached a peak in areal extent and stylistic homogeneity during the middle and late Early Classic period—the time of Manik 3 at Tikal, the Xolalpan phase at Teotihuacan, and the Esperanza phase at Kaminaluyu (Willey et al. Reference Willey, Patrick Culbert and Adams1967). Its presence is visible in the spatial distribution of actual imports, as well as a larger quantity of foreign-inspired locally produced goods (Arroyo Reference Arroyo, Hirth, Carballo and Arroyo2020:444; Clayton Reference Clayton2005; Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015:190; Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 19, 20, 37b5; Ferree Reference Ferree1972; Stanton Reference Stanton2005). Tikal had close social and economic ties with Kaminaljuyu from the Late Preclassic through the Early Classic (Coggins Reference Coggins1975:82), demonstrated by the overwhelming predominance of obsidian from the El Chayal source (Moholy-Nagy et al. Reference Moholy-Nagy, James Meierhoff and Kestle2013), imitation or actual examples of Kaminaljuyu pottery in Late Preclassic and Early Classic period elite burials (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 5c–e, 6a, 12b, c, 18a), and probably the tripod metate and mano sets of volcanic stone.

However, there are goods and depictions in Teotihuacan style that are present for only a comparatively short time during the middle and late Early Classic period. Teotihuacan influence at Tikal should be restricted to these traits that materialize an adopted ideology (Borowicz Reference Borowicz and Braswell2003; Coggins Reference Coggins1975; Pasztory Reference Pasztory and Rice1993). Their archaeological context differentiates them from the primarily domestic goods that were brought in through the exchange interaction sphere.

Artifacts and iconography on stone monuments, murals, and ceramics that express local interpretations of Teotihuacan ideology are associated almost exclusively with rulers and the highest ranked elite. Teotihuacan motifs incorporated into an eclectic style are featured on Stelae 4, 18, 31, and 32 (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:Figures 5, 26, 51–52, 55a), the Arrival Bowl, and many of the pottery vessels offered in Burials 10 and 48 (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 15–21, 29–31). Locally made pottery imitates typical Teotihuacan forms such as cylindrical tripod jars and bowls (Figures 3–7), round-side ringstand bowls (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 29h, i and 129i, j), single-chambered candeleros (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2003b:Figures 141g–u), two-part incensarios (Figure 8), and a very few pottery figurines (Iglesias Reference Iglesias Ponce de León1987:Figures 110a, c). Rare eccentrics made on green obsidian prismatic blades and some species of Pacific coast shells appear to be actual imports (Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008:Figure 34).

Prominent motifs include armed warriors, men wearing the tasseled headdress, the Storm God, the Year Sign, and the feline-headed Feathered Serpent. Feathered headdresses appear at this time. These conspicuous signs of Teotihuacan influence are expressed most strongly during Manik 3A times, diminish in Manik 3B, are absent during Ik, and have a weak revival during Late Classic Imix times (e.g., Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figure 64c2).

For decades, talud-tablero facades on building platforms were regarded as a dependable sign of Teotihuacan influence. However, further research places their appearance at Tikal toward the end of the Manik 2 ceramic complex and extends their spatial distribution to other sites in addition to Teotihuacan (Laporte Reference Laporte Molina and Braswell2003:200–203).

The Entrada

Teotihuacan is considered to have reached its zenith during its Early Xolalpan phase (ca. AD 350–450), when its influence is most widely apparent throughout Mesoamerica, although manifested differently in different regions. Inscriptions found at the Southern Lowland Maya sites of Tikal, Holmul, and El Perú-Waka’ refer to an entrada or incursion of foreigners led by a military leader named Sihyaj K'ahk’. When Sihyaj K'ahk’ arrived at Tikal in AD 378, the reigning king is said to have died. After a short interregnum Sihyaj K'ahk’ installed a new ruler, Yax Nuun Ayiin I, in AD 379. It is of special interest that inscriptions identify Yax Nuun Ayiin as a foreigner, the son of Spearthrower Owl, who was the ruler of a polity that might be Teotihuacan (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Auld-Thomas, Arredondo, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020:380). According to the epigraphic record, Yax Nuun Ayiin founded a new dynasty at Tikal that ruled until the death of his great-grandson, Chak Tok Ich'aak II, in AD 508, and possibly longer (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:37–38).

There is a lack of consensus among Mayanists regarding the nature of the entrada, where it came from, or even if it happened. The absence to date of human remains in the Maya area that can unequivocally be identified as natives of Central Mexico has suggested to some researchers that the incursion might have been from Kaminaljuyu. Teotihuacan settlers on the Pacific coast of Guatemala may have moved into the Guatemalan highlands and made forays into the lowlands from there (Arroyo Reference Arroyo, Hirth, Carballo and Arroyo2020:454; Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Auld-Thomas, Arredondo, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020:378; Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015:201; García-Des Lauriers Reference García-Des Lauriers, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020). The presence at Tikal of material culture from or inspired by Kaminaljuyu lends support to this hypothesis. At present we can only speculate whether the incursion of Sihyaj K'ahk’ is the event commemorated on the Arrival Bowl.

The entrada date of AD 378 recorded at several Lowland Maya cities is approximately equivalent to the appearance at Tikal of the Teotihuacan traits considered here as ideological. There are discernible changes in styles of public architecture, inscribed stone monuments, cached offerings, human sacrifice, and iconography. New ceramic types appear in an eclectic style that incorporates traits from Teotihuacan. These observable developments testify to changes in local sociopolitical conditions.

The iconography is clearly about power and military might, as seen in depictions of Teotihuacan warriors armed with shields, atlatls, and stone-tipped darts. The appearance of stemmed dart points of Central Mexican obsidian suggests that some Maya polities adopted a new, more efficient weapons system. Improved weapons, in turn, may have had military and political effects, similar to the effect of swords on political conditions in Bronze Age Europe (Estrada-Belli et al. Reference Estrada-Belli, Tokovinine, Foley, Hurst, Ware, Stuart and Grube2009:249; Hruby Reference Hruby2020; Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Horn and Kristiansen2018). Inscriptions, murals, and instrument sourcing of human remains attest to Tikal's territorial expansion at Holmul (Estrada-Belli et al. Reference Estrada-Belli, Tokovinine, Foley, Hurst, Ware, Stuart and Grube2009:Figure 12) and possibly Copan (Buikstra et al. Reference Buikstra, Douglas Price, Wright, Burton, Bell, Canuto and Sharer2004).

There is archaeological evidence of increased violence. Although the occasional inclusion of whole or partial human adults and children in offerings was a well-established local tradition, during the middle to late Early Classic period the quantity and frequency of human remains in ritual contexts peaked. Prominent examples are the 10 sacrificed children and subadults that accompanied Yax Nuun Ayiin I in Burial 10 (Coe Reference Coe1990:480), the caches and PDs of freshly decapitated heads in pottery bowls (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2020:53, Figure 6), and the deposit of two cremated individuals as Burial PP7TT-01 in Group 5C-11, the Mundo Perdido, one of whom was apparently burned alive (Chinchilla Mazariegos and Gómez Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos, Gómez, Arroyo, Linares and Paiz Aragón2010). These features strongly suggest the use of human sacrifice as a means of social control.

Instrument analysis has determined that Yax Nuun Ayiin I was a native of the Petén, possibly from Tikal (Wright Reference Wright2005), contradicting texts that describe him as a foreigner. Presently available evidence indicates that the change of rulers and establishment of new rulership at the end of the fourth century could equally well have been a power grab by a local Tikaleño as the installation of a new king by a foreign military power. By adopting Teotihuacan iconography, especially on highly visible stone monuments, Yax Nuun Ayiin I and his son could legitimize their regimes and fashion a new lineage for themselves (Sugiyama et al. Reference Sugiyama, Fash, Fash, Sugiyama, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020:144). Even if we assume that the decipherments of Maya texts are accurate, the hypotheses built on them often cannot be supported by available archaeological evidence and may become a hindrance to research. The archaeological record should remain our interpretive standard.

However, men from Teotihuacan wearing the tasseled headdress and escorted by armed bodyguards may well have visited Tikal and other cities in the Southern Lowlands, as recorded in representations on stone and pottery. The event depicted on the Arrival Bowl could have happened, but it is not necessary to posit an actual encounter to account for the presence of Teotihuacan-style iconography at Tikal.

Throughout recorded history, governing elites in different parts of the world have adopted stylistic and material traits from powerful, distant, or venerated cultures to elevate and legitimize themselves and their values. Some traits become incorporated into eclectic international styles (Marcus Reference Marcus and Braswell2003:342; Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer, Englehardt and Carrasco2019; Stanton Reference Stanton2005:31). Typically, international style elements move between elites before they are adopted by lower ranked members of a society.

International styles often accompany interactions with foreigners, but they can also move through time and space without direct contact. Once adopted they can be especially widespread and durable where they promote established ideology. In the United States, reverence for Classical Greece of the fifth century BC has inspired the Greek Revival architectural style among the political and economic elite since the late eighteenth century (Stanton Reference Stanton2005:31). Familiar examples are the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC (1922), and the Parthenon in Nashville, Tennessee (1897), each furnished with its own supersized deity statue. The Greek Revival style, particularly in banks, universities, and government buildings, evokes tradition, legitimacy, and democracy. During the late fourth century, Teotihuacan at its apogee could have been a source of inspiration for the Maya elite (Demarest Reference Demarest2004:104; Demarest and Foias Reference Demarest, Foias and Rice1993).

A Reversal of Fortune

Yet the archaeological record also indicates that some Maya resisted the new ideology associated with Teotihuacan. At Tikal Teotihuacan iconographic elements were adopted by Yax Nuun Ayiin I and his son, Sihyaj Chan K'awiil II, and displayed on their monuments (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:32, 34) and on ceramics among the offerings in their standard burials (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 15–21, 29–31). Teotihuacan traits and styles are otherwise absent from Group 5D-2 architecture, which, except for the early part of the Early Classic period, was the political and ritual center of Tikal. There are no talud-tablero facades on North Acropolis temples, nor are there any large obsidian biface knives or eccentrics of Teotihuacan style in any of Tikal's standard caches. At other Maya cities, such as Kaminaljuyu, Altun Ha, and Holmul, the most striking manifestations of Teotihuacan styles are at some distance from the city epicenters (Estrada-Belli et al. Reference Estrada-Belli, Tokovinine, Foley, Hurst, Ware, Stuart and Grube2009; Kidder et al. Reference Kidder, Jennings and Shook1946; Pendergast Reference Pendergast1990:266–272).

Around AD 550 the archaeology of Tikal records a violent rejection of the ruling dynasty and allied members of the elite. Images and features, especially those that evoked Teotihuacan, were damaged or destroyed. Discontent with despotic rulers may have caused elite fracture (Carballo Reference Carballo, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020:85) that led to the overthrow of the king, as well as the destruction of stone monuments, caches, and elite burials (Coe Reference Coe1990:486; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008; Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2016:Figure 5). Construction in Group 5D-2, the monumental epicenter, virtually ceased for several decades (Coe Reference Coe1990:839, Chart 1). The breaking, scattering, and relocation of Stela 29, Altar 13, and the burial that was the source of PD 50 could have been related to events that took place during this time of political disorder. Approximately contemporaneous episodes of destruction are present at other Maya cities where Teotihuacan influence is evident; for example, in the devastation of the epicenter of Río Azul (Sharer with Traxler Reference Sharer and Traxler2006:327) and the demolition of talud-tablero facades on buildings at Kaminaljuyu (Arroyo Reference Arroyo, Hirth, Carballo and Arroyo2020:447). Early Classic Special Deposit C117F-1 at Caracol shows numerous similarities with PD 50 and may also be the smashed, burned, and relocated remnants of the richly provisioned burial of a high-status individual who was accompanied by sacrificed retainers (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2011:9–14).

An early, often-referenced rejection event is recorded at Altun Ha. A set of 235 Teotihuacan-style green obsidian eccentrics, 13 green obsidian stemmed projectile points, and pottery vessels probably imported from Teotihuacan were found jumbled together in a large deposit of sherds, small shell and jade beads, chipped stone artifacts, and chert and shell debitage above Burial F-8/1, an elite burial of the third century AD (Pendergast Reference Pendergast1990:266–272). Pendergast refers to this deposit as a post-interment offering. However, its contents other than the green obsidian artifacts are rarely mentioned. The mix of exotic ritual artifacts, ornaments, and household and workshop debris would have been classified as a problematical deposit had it been found at Tikal (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2020). Pendergast (Reference Pendergast and Braswell2003:246–247) remarks on the absence of Teotihuacan-derived traits at Altun Ha after the placing of the burial and deposit. The early rejection of Teotihuacan ideology at Altun Ha appears to have been decisive.

There may also have been animosity against the Maya at Teotihuacan, suggested by isotopic and cultural evidence. The three high-status victims of Burial 5 in the Moon Pyramid were sacrificed around AD 350. All may have had connections of some kind to the Maya area (Sugiyama et al. Reference Sugiyama, Fash, Fash, Sugiyama, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020:144; White et al. Reference White, Douglas Price and Longstaffe2007:168). At about the same time, a mural painted in Maya style in a palace in the Plaza of the Columns was destroyed (Sugiyama et al. Reference Sugiyama, Fash, Fash, Sugiyama, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020:140). Fragments of another Maya mural at Tetitla, the pinturas realisticas, are thought to have been destroyed about a century later (Sugiyama et al. Reference Sugiyama, Fash, Fash, Sugiyama, Hirth, Caballo and Arroyo2020:145).

At the beginning of the Early Late Classic period (ca. AD 550), Tikal broke with the past and set off in a new direction. A hiatus in dates on Tikal's carved stone monuments, the longest gap of three or four in the sequence, is one of the most discussed features of this period. The prevailing opinion is that Tikal went into a period of decline during this time caused by a military defeat by Calakmul or Caracol in AD 562. However, this view is contradicted by the archaeological record. Tikal's Early Late Classic period was characterized by population growth, general material prosperity, notable innovation in civic architecture such as the first Great Temples and Twin Pyramid Complexes, new types of portable material culture, the emergence of new forms in utilitarian and display pottery, and the extraordinary, naturalistic, painted, and incised decorative style of the Ik ceramic complex (Coe Reference Coe1990:840–846; Culbert Reference Culbert1993; Culbert and Kosakowsky Reference Culbert and Kosakowsky2019:11). Cached offerings in temples peak in size, richness, and diversity (Begel Reference Begel2020; Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy2016; Moholy-Nagy with Coe Reference Moholy-Nagy and Coe2008), while offerings of durable materials in rulers’ burials are more modest compared to earlier and later periods. Sacrificed human attendants are no longer included in standard burials after the interment of Burial 200 at around AD 550–600 (Coe Reference Coe1990:404–405). It seems as though limits had been imposed on the power of the rulers after the authoritarianism of the Early Classic (Adams Reference Adams1999:144–145). During the Late Xolalpan phase, Teotihuacan experienced social disarray, conceivably culminating in the burning of its epicenter around AD 550 (Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015:233). The decline of Teotihuacan may have contributed to the rejection of ideology associated with it (Coe Reference Coe1990:946).

Conclusion

The eclecticism evident in middle and late Early Classic iconography, architecture, and ceramics strongly suggests that an authoritarian and militaristic ideology arose from political developments within the Maya area and was refined and reinforced by direct contacts with Teotihuacan. The selective, relatively short-lived manifestation of Teotihuacan style and iconography among Tikal's elite suggests that some resistance may always have been present, which could have played into the archaeologically observed disorder at the end of the Early Classic period. PD 50, the remnants of the desecrated burial of a high-ranked adherent of the new ideology, is an especially intriguing example.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to William Haviland, Esther Pasztory, and Julia Hendon for their thoughtful comments on earlier versions of this article. It also benefited considerably from the critiques and suggestions of three anonymous reviewers. Virginia Greene made the rollout drawing of the Arrival Bowl and provided a copy of Stuart Scott's fieldnotes.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data used in this article are published. Unpublished excavation lot cards, object catalog cards, and Stuart Scott's field notes are held in the Tikal Project archive at the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.