And so, making the people joyful and giving their solemn banquets and drinking feasts, great taquis, and other celebrations such as they use, completely different from ours, in which the Incas show their splendor, and all the feasting is at their expense [Cieza de León Reference Cieza de León and de Onis1959:191].

Food is a subsistence resource, “utterly essential to human existence” (Mintz and Du Bois Reference Mintz and Du Bois2002:99) and a powerful symbol of cultural identity (Mintz Reference Mintz1985; Twiss Reference Twiss and Twiss2007); it plays a prominent role in the establishment of social bonds and political alliances (Dietler Reference Dietler, Dietler and Hayden2001; Goldstein Reference Goldstein and Bray2003; Meigs Reference Meigs, Counihan and Van Esterik1997). Because of its capacity to attract people (Krögel Reference Krögel2011), food is often used as a resource to draw large crowds together and is an essential element of ritual celebrations and the execution of labor-demanding tasks. Such gatherings are critical for socialization and the creation of togetherness and social cohesion (Whitehouse and Lanman Reference Whitehouse and Lanman2014). The Inka state was aware that eating and drinking together provided unparalleled opportunities to establish trust, friendship, and mutual reciprocal obligations; to that end, the state invested time and resources and purposely staged extravagant banquets in which food played a prominent role (Morris Reference Morris, Collier, Rosaldo and Wirth1982).

Morris (Reference Morris, Collier, Rosaldo and Wirth1982) documented at Huánuco Pampa large quantities of culinary paraphernalia that he interpreted to be evidence for large-scale ceremonial feasts and drinking sessions staged by the Inka state to cement and maintain political loyalty. At Jauja, another Inka provincial center, Costin and Earle (Reference Costin and Earle1989) and D'Altroy (Reference D'Altroy1992) showed that commensal hospitality was a recurrent strategy employed by the state. Public spaces were the appropriate settings for feasting sessions; hence, all Inka provincial centers were built with plazas (Hyslop Reference Hyslop1990).

The drink distributed at such celebrations was maize beer (Hastorf and Johannesen Reference Hastorf and Johannessen1993), but the specific food available at such festivities has been less certain. A wide variety of foods were offered to the Inka (Cobo Reference Cobo1964 [1653]), but their cooking methods reportedly consisted mainly of boiling and roasting; thus, their meals were mostly “soups and stews” (Bray Reference Bray and Bray2003:103). Following Cobo, Jennings and Duke (Reference Jennings, Duke, Alconini and Covey2018:305) claim that Inka “cuisine was more modest in its scope, more local in its focus, and simpler in its preparation.” Perhaps this was the case for the everyday meals. If so, what about the food prepared and served at special occasions? It is worth stressing that in Inka times meat was rarely consumed, except at banquets and festivities (Cobo Reference Cobo1964:244). This observation indicates that meals consumed on a daily basis were different from those prepared for special occasions. Meat is a highly valued product, and its consumption makes the meals special.

A recent archaeological excavation at Tambo Viejo, an Inka center in the Acari Valley of the Peruvian south coast (Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Huamaní, Bettcher, Liza, Aylas and Alarcón2020), made the unprecedented finding of three earthen ovens found in association with food remains. In this report, we describe and discuss the implications of the ovens and associated food remains.

Tambo Viejo and the Earthen Ovens

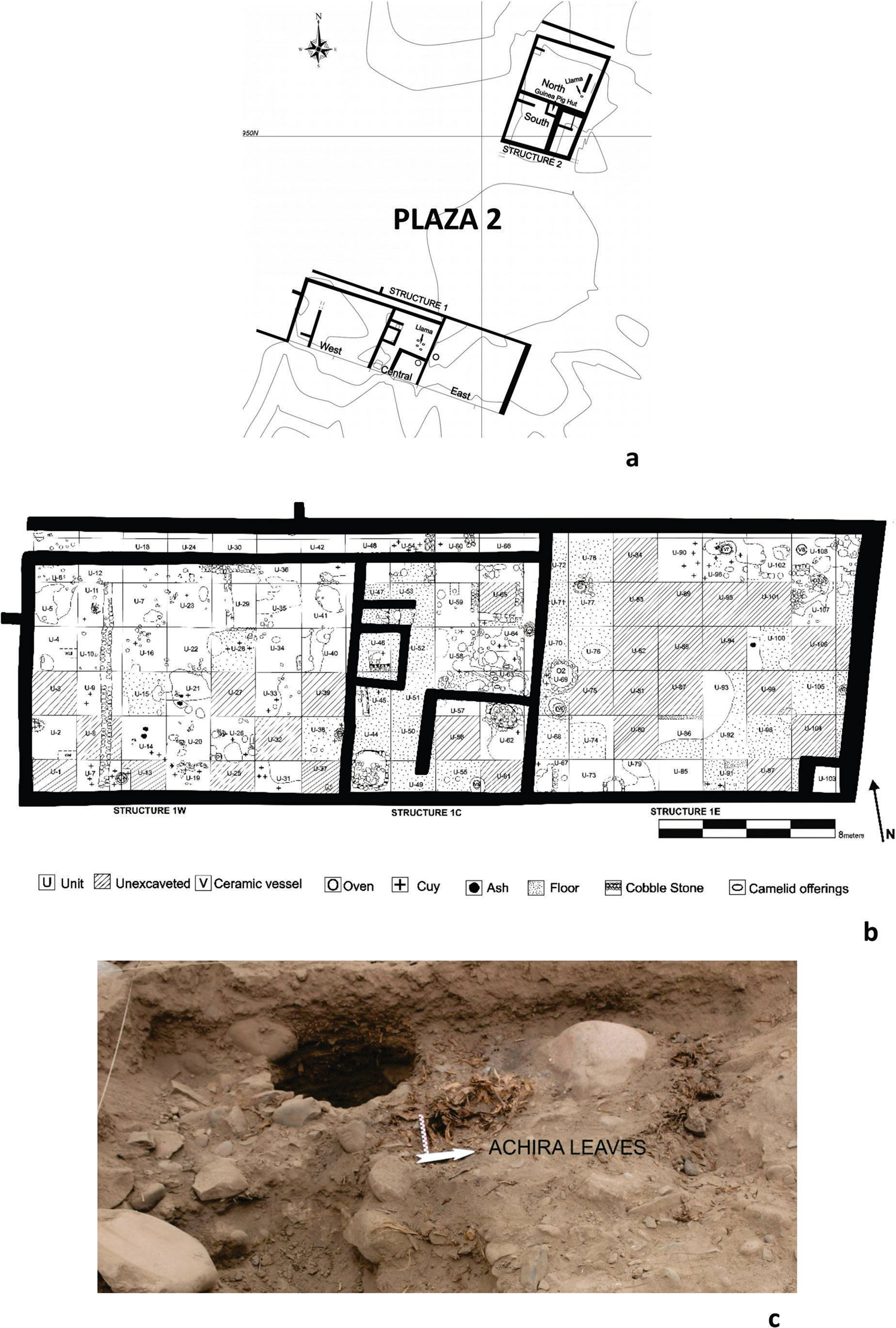

Following the annexation of the Peruvian south coast, the Inka established several provincial centers (Figure 1a). Tambo Viejo was established in the Acari Valley and built with two spacious plazas (Figure 1b), around which many structures were laid out. Plaza 1, the larger plaza, dominates the northern portion of the site; a smaller plaza (Plaza 2) is found about 100 m to its south. Two structures adjacent to Plaza 2 were recently excavated to gain a better understanding of the role of Tambo Viejo within the Inka empire (Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Huamaní, Bettcher, Liza, Aylas and Alarcón2020). These structures were selected because of their location adjacent to the plaza, a culturally constructed open and public space (Moore Reference Moore1996). Structure 1 is a large rectangular building that extends almost the entire length of the southern side of Plaza 2 (Figures 2a and 2b). Structure 2 is a smaller building found immediately north of Plaza 2. The data discussed here come from Structure 1.

Figure 1. (a) Location of Tambo Viejo (prepared by Miguel A. Liza); (b) site plan (prepared by Benjamín Guerrero). (Color online)

Figure 2. (a) Location of excavated structures and Plaza 2 (prepared by by Benjamín Guerrero); (b) plan view Structure 1 (prepared by Miguel A. Liza); (c) Oven 1 and associated achira leaves (photo by Lidio M. Valdez). (Color online)

Archaeological excavation conducted in Structure 1 revealed three earthen ovens. Oven 1 (Figure 2c) was found in the central-south section of the western division of Structure 1 (southwest of U26). It consists of a cylindrical pit that is 48 cm in diameter and 60 cm in depth, extending down into a sterile soil. The pit's opening was marked with cobblestones that formed a circle. At the base of the pit was an accumulation of ash and charcoal; immediately above that was an accumulation of achira leaves (Canna edulis). More achira leaves were found next to the opening of the oven, and plant remains and camelid bones were scattered around the oven. Several guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) offerings were also found in the immediate area (Valdez Reference Valdez2019); some were adorned with elegant sets of long, beautiful string earrings and necklaces made of camelid hair.

Oven 1 was established at the time the southern wall of Structure 1 was built but before the rest of Structure 1 was completed. Other structures were subsequently demolished, leaving behind only some traces of the old cobblestone walls. The excavation work in Structure 1 revealed the clay floor that sealed Oven 1. The oven and associated guinea pig offerings are indicative of ritual celebrations performed at the time that construction of Tambo Viejo began.

Subsequently, Structure 1 was constructed seemingly as a single large building, during which a new oven (Oven 2, Figure 3a) was established at the western side of what eventually became the eastern division (U69–70). Oven 2 is much larger than Oven 1 and is cylindrical in shape, 1 m in diameter, and 1.2 m in depth. Its walls were constructed of small cobblestones mortared with clay, with its opening at the floor level. The fact that it was well constructed and was larger than Oven 1 suggests that it was built to function for a longer time and to cook food for large crowds. The oven was filled with debris that included charcoal and some pacay (Inga feullei) and achira leaves. Some partially burned sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) and camelid bones (Figure 3b, 3c, and 3d) were found inside the oven. Just south of the oven a large broken narrow-neck ceramic vessel was found. As with Oven 1, there were guinea pig offerings around the opening of Oven 2 (and the narrow-neck vessel). The finding of mixed debris inside the oven suggests that it was disturbed, possibly by looters. Except for its vertical wall, Oven 2 is comparable to the earthen oven from the early Nasca ceremonial center of Cahuachi, which also had stone walls and was large (Valdez Reference Valdez1994).

Figure 3. (a) View of Oven 2; (b) partially burned sweet potatoes; (c–d) partially burned camelid bones; (e) plate fragment found near Oven 2 (photos by Lidio M. Valdez). (Color online)

Oven 3 was excavated at the northeast corner of Structure 1 (U107–108). It consists of a cylindrical pit, only 40 cm in diameter and 30 cm in depth. At its base there was an accumulation of ash; at the surface level several cobblestones formed a circle, above which an accumulation of achira leaves was found. The oven was established by breaking the most recent clay floor, which suggests that it was built after Oven 2 was abandoned.

These features, including the oven from Cahuachi, are analogous to contemporary earthen ovens used to prepare a present-day meal known in Peru as pachamanka. The four steps for cooking this type of meal are as follows: (1) a pit is dug; (2) the oven is heated for about an hour with plenty of firewood; (3) a layer of achira leaves is placed right over the hot charcoal, above which all the food is placed and covered with a second layer of achira leaves; and (4) the entire oven is completely buried with dirt. After about an hour the oven is opened, and first the dirt and then the top layer of achira leaves are removed to expose the cooked food. Pachamanka is usually prepared for special occasions.

In association with the Tambo Viejo ovens (especially Oven 2), our analysis revealed bones of all body parts of camelid, some of which were partially burned (Table 1), indicating that live animals were brought and slaughtered in the site. We determined that most of the animals had been in the prime of life. Several limb bones were about to fuse or had just fused, indicating an age about two to four years old. This is in line with historical accounts that state that the camelids slaughtered for feasts were mostly young males (Murra Reference Murra1983). Several limb bones were found unfractured, indicating that the meat probably was not boiled in a ceramic vessel, because it would have been impossible to introduce entire body parts into a cooking pot. Instead, such findings indicate that food was cooked in the pachamanka style. The evidence coming from a nondomestic context seems to show that food for special occasions was prepared in earthen ovens. The finding of broken plates along the camelid bones indicates that food was served on decorated dishes (Figure 3e).

Table 1. Representative Camelid Bones from the Eastern Side of Oven 2.

Notes: Other body parts (vertebrae, ribs, carpals, tarsals and phalanges) are also present. A = adult; SA = subadult; MNI = minimum number of individuals.

Concluding Comments

This evidence reveals that the Inka state staged special celebrations at Tambo Viejo that included the placement of special offerings and the consumption of food prepared for the occasion. The special offerings included adorned guinea pigs and llamas (Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Huamaní, Bettcher, Liza, Aylas and Alarcón2020), perhaps deposited as gifts to supernatural entities. It also appears that, for these occasions, large local crowds were brought together. At the culmination of the festivities, the participants received food as a sign of generosity and reciprocity that ultimately served to cement political loyalty and to legitimate the Inka presence.

Food consumed at Inka public ceremonies staged at Tambo Viejo was prepared in a manner that is analogous to contemporary pachamanka. Although it is likely that most people throughout the Inka realm were familiar with camelid meat, the ordinary was made exceptional through the use of earthen ovens that probably added a different flavor, thus making the occasion memorable. Moreover, instead of cooking food in several ceramic vessels, the most efficient way of preparing food for large crowds was in the pachamanka style: its use in Inka times has been suggested by other researchers after finding some partially burned bones (Costin and Earle Reference Costin and Earle1989; Quave et al. Reference Quave, Kennedy and Covey2019; Sanderfur Reference Sandefur, Altroy and Hastorf2001). The presence of earthen ovens at Tambo Viejo confirms these suggestions, demonstrating that, as in more recent times, pachamanka was the special-occasion food for the Inka.

Acknowledgments

Research at Tambo Viejo was authorized by the Peruvian Ministerio de Cultura (Resolución Directoral 086-2018/DGPA/VMPCIC/MC). The first author received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data are currently housed at the storage facility of the Ministerio de Cultura–Arequipa, in the city of Arequipa, Peru.