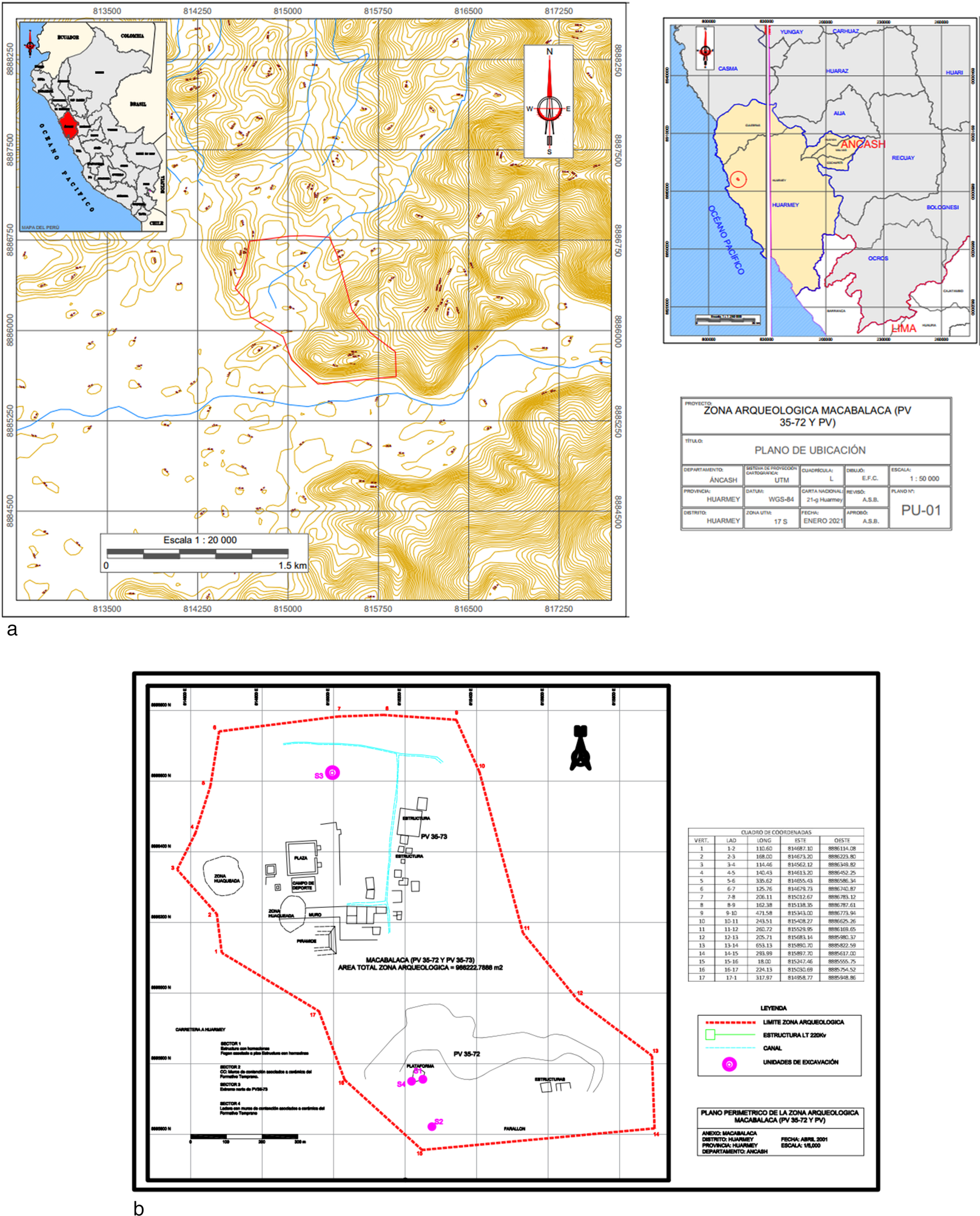

The site of Macabalaca (PV35-72) is in the northern section of the Huarmey Valley, Peru, 5.4 km from the seashore (Figure 1). It is located on top of the Huasmani mound, 24 m above the valley floor. Duccio Bonavia (Reference Bonavia1982) described it as a site with simple architecture and three tall walls; he also reported “early ceramics” and dated the site to the Early Horizon (Middle and Late Formative) and Early Intermediate periods. Additionally, Ernesto Tabío (Reference Tabío1977) noted that he found Viru ceramics (Early Intermediate period) on its surface. The walls that Bonavia refers to are at the southeast section of the mound top and are currently fallen.

Figure 1. (a) Location of Macabalaca; (b) general plan of the site of Macabalaca; the Kotosh Religious Tradition (KRT) chamber is located on S1 (maps by Jennifer Perez-Varillas). (Color online)

Rescue excavations at the site identified an artificial rectangular terrace 270 m2 from the northwest section of the hilltop. This terrace, which was neither described by Bonavia nor Tabío, is the location of a structure that we identify as belonging to the Kotosh Religious Tradition (KRT). This tradition is known for the burning of offerings in a central hearth (Burger Reference Burger1992; Burger and Salazar Reference Burger and Salazar1980, Reference Burger, Salazar and Donnan1985). Though prevalent during the Late Archaic period (2800–1800 BC), the KRT continues well into the Middle Formative and is even present during the Black and White phase of the Late Formative period (900–550 BC) at Chavín de Huántar (Contreras Reference Contreras2010).

Our new data allow us to state that KRT architecture has been found in almost all the valleys on the central coast, extending at least from Santa (Montoya Reference Montoya2007) to Supe (Shady Reference Shady1997). The finding has important implications for the understanding of religious and social dynamics during the Late Archaic and Early Formative periods.

Excavations

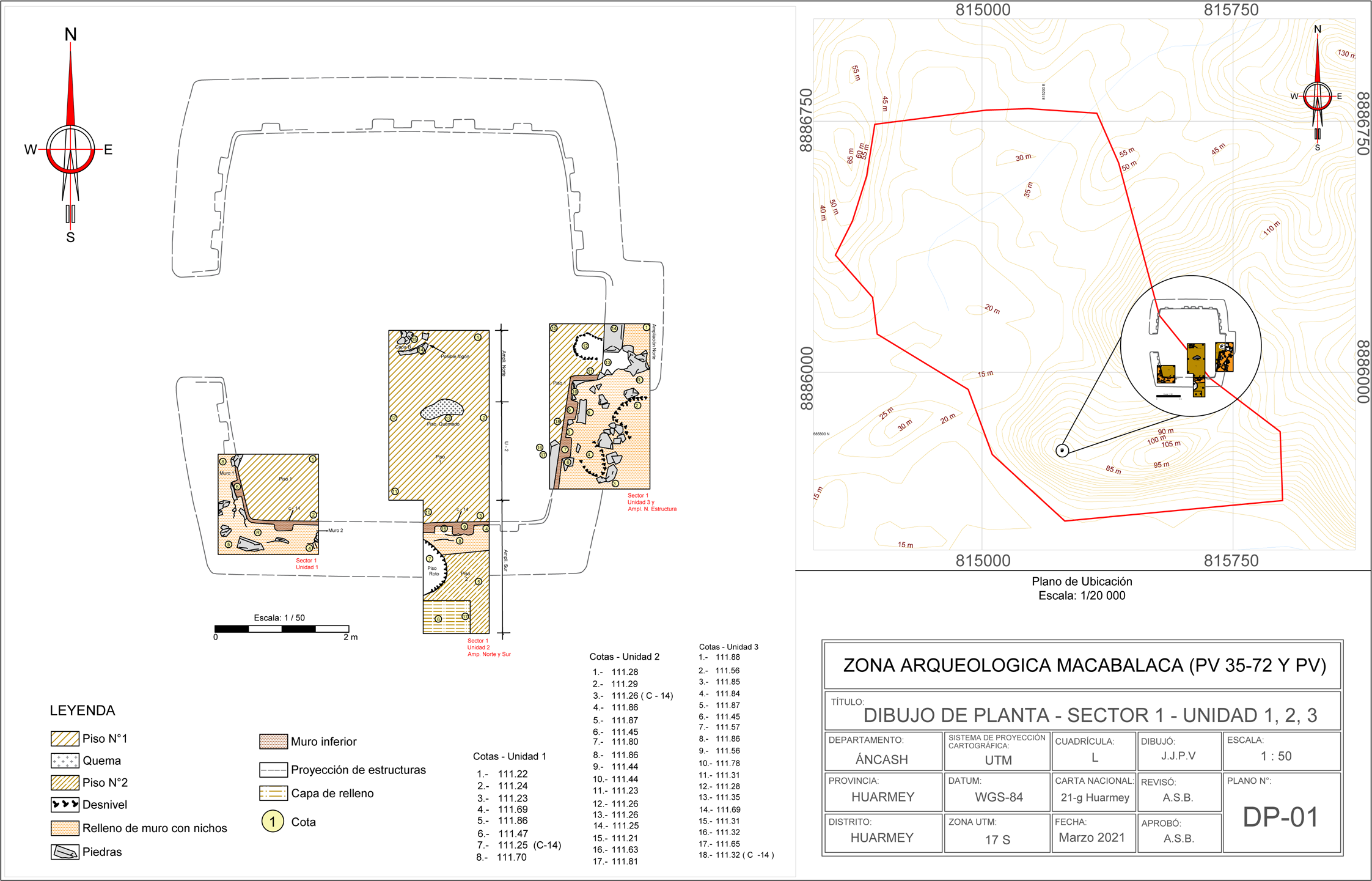

Nine units, which measured between 1.5 m2 and 2.0 m2, were excavated on the terrace. Units 1, 2, and 3 yielded architectural evidence of a rectangular structure with rounded corners, small rectangular niches on its walls, and a central hearth (Figure 2). Units 2 and 3 allowed us to trace the architectural features identified. The north expansion of Unit 2 was carried out to find the central hearth that should be located to the north. This enlargement measured 1.5 m2; it was then expanded 1.5 m2 to the south to determine the external face of the KRT structure, which revealed an apparently late intrusion that disarticulated the wall. The expansion to the north of Unit 3 was carried out to find the wall that should define the eastern side and to establish the width of the east wall; this extension measured 0.5 m2.

Figure 2. Plan of the KRT chamber (plans by Jennifer Perez-Varillas). (Color online)

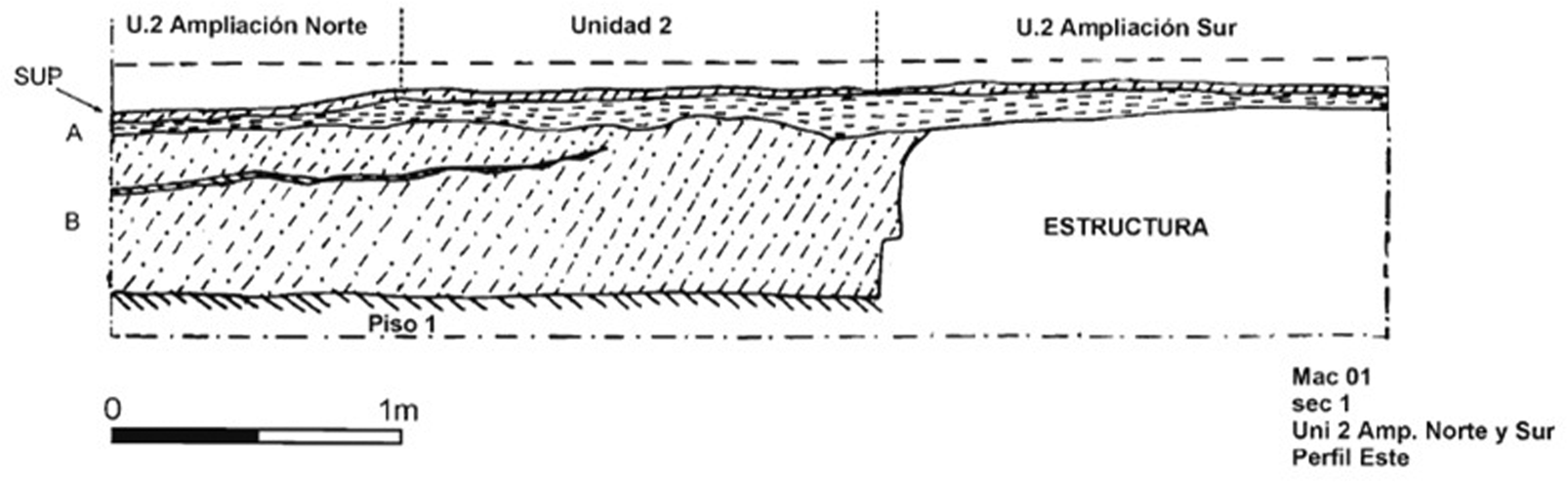

The stratigraphy of all units is similar. The structure was covered with a clean fill comprising small-sized stones and earth, with no cultural elements; this fill was placed on top of the floor and its walls (Figure 3). The floor is located 0.60 m below the surface and is characterized by the presence of a central hearth, three small burnt areas on its southwest corner, and an elongated burnt patch located south of the central hearth (Figure 4a). On top of the hearth there was a layer that was 0.10 m wide and made of compressed totora mixed with clay (Figure 4b). The platform was leveled by a layer of small pebbles and irregular stones, ceramic fragments, malacological materials, and macrobotanic plant remains placed on top of the clean fill. The ceramics retrieved from this layer may be assigned to the Early Formative period.

Figure 3. Stratigraphy of Unit 2 (drawn by Angel Sánchez-Borjas).

Figure 4. (a) Southwest corner of the KRT structure; (b) stratigraphy of the north profile of Unit 2; note the totora and clay layer (photos by Christian Mesía-Montenegro). (Color online)

Architectural Features

The architectural features found in the structure include niches, a bench, a hearth, and a floor. Five complete rectangular niches with rounded corners and plastered walls were uncovered (Figure 5), the mean measurements of which are 0.29 m wide, 0.28 m high, and 0.10 m deep (Table 1). Although we did not find any objects such as small religious tokens in the niches, we suggest that they could have been used for this purpose.

Figure 5. (a) KRT structure's south wall in Unit 1; note the niches and floor; (b) different view of the south wall in Unit 1; (c) KRT structure's south wall in Unit 1; note the plaster on the niches and walls; (d) KRT structure's east wall; the round corner leads to the bench (photos by Christian Mesía-Montenegro). (Color online)

Table 1. Niche Measurements in Meters.

A bench, which was partially uncovered on the east wall, was aligned with the circular hearth located in the center of the floor. We only uncovered a portion of the bench that was 0.73 m wide, 0.29 m high, and 0.47 m deep. We hypothesize that the bench had a total width of 1.40 m, large enough for two people to sit on it. Its location is prominent: it faces the entrance of the chamber.

The hearth is in the center of the chamber's floor; we uncovered the south half of it. The hearth is roughly circular and is delimited by irregular medium and small-sized rocks. It has an estimated area of 0.27 m and an estimated diameter of 0.59 m. It was not excavated.

The floor is a flat surface covered with white plaster, probably the same plaster used on the niches and walls (Figures 4 and 5). There is an elongated patch of burnt soil (0.12 m2) located 0.8 m south of the hearth. and three roughly circular patches of burnt soil are at the temple's southwest corner. We have not ruled out the presence of a subterranean ventilation shaft, which is present in some KRT structures (Bonnier Reference Bonnier, Bonnier and Bischof1997; Izumi and Terada Reference Izumi and Terada1972; Izumi et al. Reference Izumi, Cuculiza and Kano1972). The walls were made of middle-sized rectangular stones, joined together with clay and covered with white plaster, reaching a height of 0.5 m.

The temple's entrance may have been located at the west section of the temple (in what would have been the center of the west wall) following the west–east central axis and aligned with the bench and hearth (Figure 3).

Excavations covered only 6.2.m2 (20.7%) of the estimated 29.7 m2 area structure. The layer made of totora and clay may be a portion of the roof that covered the temple and that was buried alongside the structure, as seen in the site of Bahía Seca (Pozorski and Pozorski Reference Pozorski and Pozorski1996).

The structure has rounded corners, like the KRT temples from the Late Archaic and Early Formative periods in La Galgada (Grieder and Bueno Reference Grieder and Bueno1981; Grieder et al. Reference Grieder, Bueno Mendoza, Smith and Malina2012), which is 180 km north of Macabalaca in the Tablachaca Valley. The walls of Macabalaca are decorated by rectangular niches with rounded corners. The third reconstruction shows the probable presence of 24 small niches (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Daylight three-dimensional reconstruction of the MT structure (re-creation by Jennifer Perez-Varillas).

Discussion

The location of Macabalaca facilitated aspects of land management and control of water resources because the top of the Huasmani hill provides a strategic view of the lower Huarmey Valley and its resources. Unlike other KRT chambers in the Andes, there is no succession of superimposed constructions at Macabalaca: the terrace where the chamber is located was built on top of sterile soil, and there is no indication of the presence of more chambers in the hill. If no additional chambers are to be found in the platform, this pattern would be consistent with what has been reported at coastal sites such as Huaynuná and Bahía Seca in the Casma Valley (Pozorski and Pozorski Reference Pozorski and Pozorski1990, Reference Pozorski and Pozorski1996) and the so-called Altar del Fuego Sagrado at Caral in the Supe Valley (Shady Reference Shady1997), which are stand-alone structures.

A great deal of complexity is represented in the spread of monumental architecture through the Central Andes as early as 3600 BC (Fuchs and Patzschke Reference Fuchs, Patzschke and Fux2013). The progression from small mounds to large ones can be seen in the central coast from the valleys of Casma to Huacho, where a nucleus of complex monumental architecture dominated the landscape (Hass and Creamer Reference Hass, Creamer and Silverman2004, Reference Hass and Creamer2006; Pozorski and Pozorski Reference Pozorski and Pozorski1996, Reference Pozorski and Pozorski2018). In the highlands, the KRT tradition became popular between the regions of Ancash and Huánuco (i.e., Kotosh, Shillacoto. Huaricoto, Galgada, El Silencio). KRT structures vary in shape and the presence of split-level floors and freestanding structures with niche. Overall, though, the principle is the same: they are circular (e.g., Bahia Seca, Huaricoto, Piruro, Caral) or rectangular structures (e.g., Shillacoto, Kotosh, Piruro, Caral, Huaricanga) with a central hearth. Structures can have surrounding tall walls covered with log roofs (e.g., Galgada, Kotosh) or be open and exposed (e.g., El Silencio). More complex ones such as at Kotosh even have molded friezes and niches. In the Norte Chico, KRT structures coexist with large, superimposed platforms and large circular plazas, as can be seen in Caral and Huaricanga (Piscitelli Reference Piscitelli, Barber and Joyce2017; Shady and Leyva Reference Shady and Leyva2003). The structure found at Macabalaca has features common to KRT structures, such as a rectangular plan, a central hearth, and niches; it was probably roofed judging by the compressed totora layer mixed with clay recorded on top of the hearth, which resembles the roof registered at Bahía Seca.

Despite the differences among KRT chambers, the main architectural elements where rituals were performed were maintained throughout (Burger Reference Burger1992), as can be seen in the sites already mentioned. These sites shared common beliefs translated into similar rituals, performed in analogous settings.

Seventy kilometers north of Macabalaca in the Casma Valley, Pozorski and Pozorski (Reference Pozorski and Pozorski1996) identified both circular and rectangular KRT structures. Circular structures are found in multicomponent sites such as Haynuná and Pampa de Llamas Moxeque, whereas rectangular ones are present in sites such as Bahía Seca, Pampa de Llamas Moxeque, and Taukachi-Konkan. Absolute dates from these sites put their construction in the transition between the Late Archaic and Early Formative periods (Pozorski and Pozorski Reference Pozorski and Pozorski1996). To the south of Macabalaca, the sites of Caral (112 km south) and Huaricanga (60 km south) have KRT structures as well. Huaricanga is a multicomponent site with at least five superimposed KRT structures dated between 2800 and 2200 BC (Creamer et al. Reference Creamer, Alvaro Ruiz, Perales and Haas2013; Piscitelli Reference Piscitelli, Barber and Joyce2017).

During the Late Archaic and Formative periods, the highlands and coast were interconnected, judging by the spread of the KRT. These sites shared beliefs but maintained their political autonomy (Vega-Centeno Reference Vega-Centeno and Vega-Centeno2017), building an economic exchange system and a network of shared ideas. The chambers were not only religious catalyzers but also ideological ones, because all social relations (including political and economic ones) were embedded in the religious system. Leaders, chiefs, and aggrandizers played an important role in managing not only architectural projects such as Macabalaca but also all the aspects related to what was being mediated in these structures.

We cannot be definitive regarding the chronology of the site. Based on the lack of cultural materials in the temple's fill, one could propose a Late Archaic date. But there are some caveats. A ritual entombment lacks cultural materials so it can embody cleanliness (Onuki Reference Onuki1999, Reference Onuki and Seki2014); therefore, the lack of materials can be more an indicator of sacredness than a chronological marker. Even though the layer that convers the fill does not contain diagnostic cultural materials (except for a neckless jar rim), there are indications of small Formative structures on the upper west and south slopes of the Huasmani hill (Sectors 2 and 4). These yielded Formative ceramics (Figure 7), including neckless jars and bowls; the brown, smoothed surface and the lack of decorations might indicate an Early Formative date. We did not find any shicra bag in any excavation at Macabalaca (shicra bags are ubiquitous in Late Archaic structures). Thus, we can only hypothesize that the KRT structure excavated at Macabalaca can either be assigned to the Late Archaic or Early Formative. Further excavations and 14C dates will corroborate the site's date.

Figure 7. Ceramics retrieved from Sector 2 (drawn by Angel Sánchez-Borjas).

Conclusions

Excavations at Macabalaca uncovered a KRT chamber, which is located on the hilltop of the Huasmani mound in the lower Huarmey Valley. It has an estimated area of 29.72 m2 and has the following features: a quadrangular floor with rounded corners, niches, a seating bench, a plastered floor, and a central hearth.

After the site was constructed and used, a new architectural project began in which adjacent structures were built without affecting the floor area or its internal walls. At some point in time the project was abandoned, and the site was completely covered by clean refuse, following the pattern of ritual entombment described by Onuki (Reference Onuki1999, Reference Onuki and Seki2014) that is prevalent in sites belonging to the Mito Tradition (MT; Bonnier Reference Bonnier, Bonnier and Bischof1997; Grieder et al. Reference Grieder, Bueno Mendoza, Smith and Malina2012; Onuki Reference Onuki and Seki2014). After the temple's entombment, the platform was completely leveled. The site may be dated either to the Late Archaic period (based on the lack of ceramics in the fill covering the MT structure) or to the Early Formative (based on the ceramics retrieved from the nearby slopes). Only further excavations and absolute dates will confirm its date.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Empresa de Transmisión Electrica Centro Norte, which financed the excavations as part of a CRM project authorized by the Peruvian government. We also thank the anonymous reviewers who took the time to review this article and to provide insightful recommendations.

Data Availability Statement

Excavated materials are curated at the Museo Regional de Casma, Peru.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.