In urban landscapes, market exchange has typically been viewed as a key provisioning strategy for households and institutions (Berdan Reference Berdan1975; Blanton Reference Blanton, Berdan, Blanton, Boone, Hodge, Smith and Umberger1996; Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008; Fargher Reference Fargher2009; Hirth Reference Hirth1998). In this regard, the organization of market economies at differing scales of interaction, such as at the household or state level, is stimulated by different motivations, with some initiated by political interests and others that originate in household decision making concerning agricultural and crafting strategies (e.g., intensification, extensification, specialization, and diversification; Fargher Reference Fargher2009; Hirth Reference Hirth and Hirth2010; Morrison Reference Morrison1994).

The large complex market systems of Late Postclassic period (LPC) Mesoamerica (AD 1350–1521) served both political and domestic needs, requiring market builders to overcome difficulties associated with self-interested, rationally motivated individuals, including local merchants, long-distance traders, elites, and commoners who supplied and consumed the goods and services offered in marketplaces (Blanton Reference Blanton, Hirth and Pillsbury2013). How did these various actors effectively navigate potentially harmful behaviors associated with rational motivations and competitive behavior involving the control and exchange of private goods? Collective action theory provides an important framework to explore this question (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008, Reference Blanton and Fargher2009).

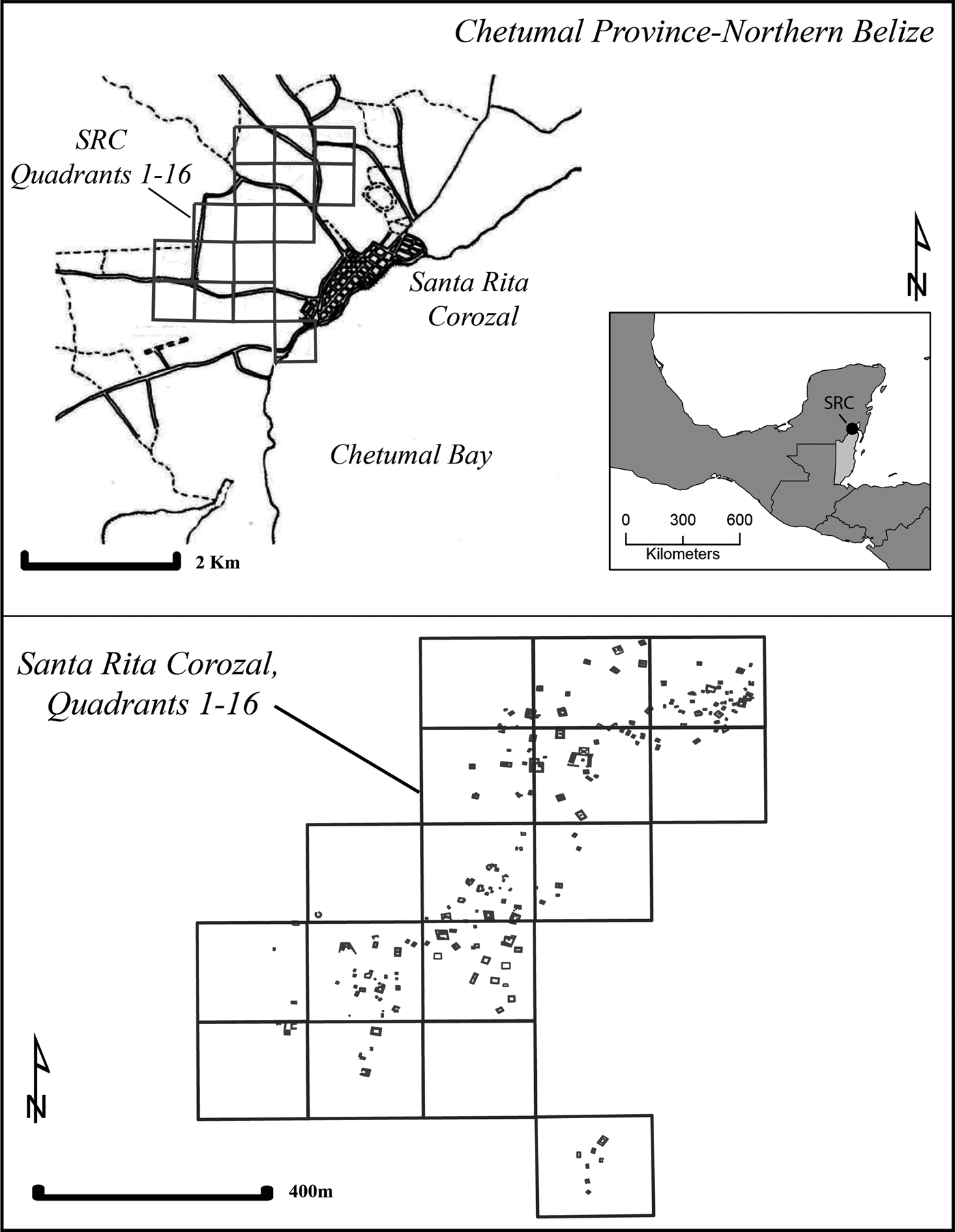

Accordingly, we compare access to projectile points, a formal tool that often figures in discussions of wealth and status variation (Andrieu Reference Andrieu2013; Carballo Reference Carballo2007; Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992; Hirth Reference Hirth, Santley and Hirth1993:136; Meissner Reference Meissner2017, Reference Meissner, Rice and Rice2018; Scholes and Roys Reference Scholes and Roys1948:344), from two LPC sites with differing governing structures. Tlaxcallan, located in Central Mexico, used a highly collective governing strategy directed toward incorporating commoners and elites in a unified political structure in which power was shared (Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010; Fargher, Blanton, et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton, Heredia Espinoza, Millhauser, Xiuhtecutli and Overholtzer2011; Fargher, Heredia, and Blanton Reference Fargher, Blanton, Heredia Espinoza, Millhauser, Xiuhtecutli and Overholtzer2011). In contrast, the coastal Maya capital of Chetumal (Figure 1), in northern Belize, used a comparatively exclusionary strategy (Chase Reference Chase1982, Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992; Masson Reference Masson2000; Oland Reference Oland and Walker2016).

Figure 1. Contemporary Santa Rita Corozal, the capital city of the Chetumal polity, with sites and sectors mentioned in text (after Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1988:Figures 41–52).

Both polities featured different political-economic strategies, and differences in the provisioning of these two cities are tested archaeologically. Collective strategies are expected to provide “open” markets that enhance market access across social sectors while providing tax revenues to the state (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016:69–98; Carballo et al. Reference Carballo, Roscoe and Feinman2014). “Restricted markets” occur where political institutions do not develop regulations that protect buyers and sellers, and the production and distribution of commodities, especially exotic and foreign goods, are manipulated by elites as part of exclusionary political strategies, resulting in a multitiered market system (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016:69–98; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016).

Collective Action Theory

Collective action theory focuses on revenues (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008; Lindkvisk Reference Lindkvist and Samson1991) and how they are allocated by governments, institutions, or elites. Internal revenues are drawn from free taxpayers, such as harvest taxes, market taxes, or corvée labor (Levi Reference Levi1988). When governments rely on joint production of these revenues, more requirements will be in place to distribute those revenues back to the state's constituents (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008). Where taxpayers (farmers, merchants, artisans) have direct control over their production and the government relies on them for revenue, they will have more say in the use of public funds (Carballo and Feinman Reference Carballo and Feinman2016). Specifically, revenues are reallocated to the populace in the form of public goods, which include infrastructure and services available to all members of society (Acheson Reference Acheson2011; Ostrom Reference Ostrom and Sabatier1999:497). Examples include roads, fortifications, plazas, ceremonies, markets, security, and redistribution (Carballo et al. Reference Carballo, Roscoe and Feinman2014).

If principals fail to provide such goods and services by (1) diverting public revenues to personal consumption, (2) failing to provide fair and just taxation procedures, (3) failing to control free riders, (4) or failing to distribute public goods across the state's geographic territory, then their constituents may withhold tax payments (Levi Reference Levi1988) and interrupt revenue flows into state coffers, impeding the ability of principals to achieve their political goals. Collective action theory predicts that principals, relying on internal revenues, will strive to ensure fair taxation and a wide distribution of public goods, control free riders, and monitor political agents (Fargher and Blanton Reference Fargher and Blanton2007).

Personalization of Power

External revenues are drawn from sources other than free taxpayers, including conquest, taxes on imperial territories, slaves, monopolization of international exchange, mines, and patrimonial estates (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008). Because external revenues are not drawn from a state's constituents, principals face fewer constraints on revenue allocation; they tend to use revenues for self-interested aggrandizement and to recruit clients needed to achieve their political goals. These co-optive strategies focus on the construction of elite-centered identities and patron-client networks through gifting, feasting, and bride exchanges (Blanton et al. Reference Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski and Peregrine1996).

Such finance strategies focus on private goods that can easily be restricted. Examples of finance strategies are control of craft production, exchange networks, ritual, and ideology, as well as the manipulation/control of market locations, items entering markets, or the sale of select goods (sumptuary items). In terms of collective action, restricted or attached production of items intended for limited distribution, as well as control of exchange networks, generates income from sources other than taxpayers, which frees principals from limits imposed on them by taxpayers (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2009:137; Carballo and Feinman Reference Carballo and Feinman2016:292).

Open and Restricted Markets

Markets are often necessary for household and political provisioning, but they require costly investments from all societal members (joint production). An organized system of infrastructure (roads, plazas, platforms, stalls, judicial structures) is necessary to support functional marketplaces (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016:69–98). If taxes drawn from the broader population are used to help produce a system from which the state and its constituents benefit, then a collective scenario occurs. Markets serve an important public service if transactions are fair and effectively regulated, allowing for the impartial settlement of grievances; protection of market participants from theft, misrepresentation, and price manipulations; and the provision of security outside of markets (Blanton Reference Blanton, Hirth and Pillsbury2013). Open markets flourish under such conditions; low-status individuals will have confidence in fair market conditions and will likely travel to markets outside their local communities. These collective behaviors require trust among governing officials, merchants, producers, and consumers. They also require a market mentality where social and class distinctions do not factor into transactions (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016), producing what Carrasco (Reference Carrasco and Ortiz1983:69) called “status-free acts of exchange.” In an open market, supply and demand determine distribution and price (Braswell Reference Braswell, Garraty and Stark2010:130–132; Carrasco Reference Carrasco and Ortiz1983:74), and staples, exotics, and nonlocal goods are exchanged as commodities among individuals from diverse social, ethnic, and economic statuses, because market cooperation is provided by institutional strategies (LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016:172).

Open markets fail when governing officials engage in price-fixing, influence exchange networks, or establish status-based segregation of market locations (Blanton Reference Blanton, Hirth and Pillsbury2013; Carrasco Reference Carrasco and Ortiz1983:74; Smith Reference Smith and Smith1976). Restricted markets emerge where elites use bottlenecks to manipulate supply and demand, prices, and access (DeMarrais and Earle Reference DeMarrais and Earle2017; Earle and Spriggs Reference Earle and Spriggs2015). This scenario is consistent with Smith's (Reference Smith and Smith1976:314) partially commercialized or controlled market system (Braswell Reference Braswell, Garraty and Stark2010:132). Restricted markets result in stratification of exchanges among different social or political groups, where foreign or exotic goods exchanges are monopolized by high-status individuals who are linked through social networks to governing principals (LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016:172). Accordingly, the exchange of ordinary goods is limited to local markets where trust is based on familiarity and reputation because institutional strategies promoting cooperation are absent.

Mesoamerican Markets

Commercialization intensified throughout Mesoamerica during the LPC (Blanton Reference Blanton, Berdan, Blanton, Boone, Hodge, Smith and Umberger1996; Chase and Rice Reference Chase and Rice1985; Hassig Reference Hassig1985; Hirth Reference Hirth1998, Reference Hirth2016; Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012; Sabloff and Rathje Reference Sabloff and Rathje1975; Smith and Berdan Reference Smith and Berdan2000). Marketplaces and commercialized exchanges (see Feinman and Garraty Reference Feinman and Garraty2010) are reported from many Yucatecan cities (Piña Chan Reference Piña Chan, Lee and Navarette1978) and have been identified archaeologically at Mayapan (Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012), Tulum (Oland Reference Oland and Walker2016), Cozumel (Freidel and Sabloff Reference Freidel and Sabloff1984), Caye Coco (Masson Reference Masson2000), Laguna de On (Masson Reference Masson, Masson and Freidel2002), and Chetumal (Marino et al. Reference Marino, Martindale Johnson, Meissner and Walker2016; Seidita et al. Reference Seidita, Chase and Chase2018). The dual role of the market system for the LPC Maya was to provision households with subsistence goods and to promote the long-distance exchange of items by governing officials to affirm status distinctions (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992; Hirth Reference Hirth, Chase and Chase1992; McAnany Reference McAnany, Hirth and Pillsbury2013; McKillop Reference McKillop2005).

In LPC Central Mexico, marketplaces served as a node at the intersection of the domestic and political economy (Berdan Reference Berdan1975; Blanton Reference Blanton, Berdan, Blanton, Boone, Hodge, Smith and Umberger1996; Charlton Reference Charlton, Hodge and Smith1994; Nichols et al. Reference Nichols, Brumfiel, Neff, Hodge and Charlton2002). Ethnohistorically, the largest market described in Central Mexico was at Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco; it hosted as many as 60,000 visitors on principal market days (Cortés Reference Cortés2007 [1522]). Such markets played key roles in provisioning governing institutions with taxes (Berdan Reference Berdan1975; Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Anawalt1997; Blanton Reference Blanton, Berdan, Blanton, Boone, Hodge, Smith and Umberger1996; Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016:69–98; Carrasco Reference Carrasco and Ortiz1983). Principals benefited from market integration and commercialization, especially the flow of goods into urban settlements destined to provision households. The revenue received from Aztec market taxes was likely substantial, nearly 20% on all commercial transactions (Blanton Reference Blanton, Berdan, Blanton, Boone, Hodge, Smith and Umberger1996; Berdan Reference Berdan1975; Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel, Brumfiel and Earle1987). Archaeological and ethnohistoric research suggest that market systems were highly organized (Blanton et al. Reference Blanton, Fargher, Heredia-Espinoza and Blanton2005; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2014; Dahlin et al. 2007; Hirth Reference Hirth2016; Levine Reference Levine2011; Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012; Smith Reference Smith, Garraty and Stark2010; Stark and Ossa Reference Stark, Ossa, Garraty and Stark2010).

Importantly, the Aztecs developed institutions to increase market participation and cooperation among producers and consumers. They monitored local marketplaces to curb the degree to which local authorities (e.g., tlatoque) could manipulate them (Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel, Brumfiel and Earle1987:103; Hassig Reference Hassig1985:113). Market transactions were restricted to official marketplaces, where participants could be provided with security and taxed (Blanton Reference Blanton, Hirth and Pillsbury2013; Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008; Carrasco Reference Carrasco and Ortiz1983:76; Smith Reference Smith2014). This was accomplished by ceding market management and conflict adjudication to the pochteca, a paragovernmental merchant guild (Blanton Reference Blanton, Berdan, Blanton, Boone, Hodge, Smith and Umberger1996). In the Classic period Maya Lowlands, similar systems were also noted. Market nodes were placed in strategic locations to promote administered exchange by central elites (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2004:122; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016). These actions directly benefited central elites through revenue collection, while reducing the income and influence of local and regional elites.

Archaeological Identification of Markets

The archaeological identification of market exchange uses distributional, configurational, spatial, and contextual approaches (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2014; Hirth Reference Hirth1998). The latter three are based on an evaluation of population estimates, ethnohistoric accounts, and placement of architecture. We take the distributional approach as our point of departure because it uses artifact densities to identify market exchange. It is based on the premise that market exchange provides equal access to goods. Therefore, artifact densities found in households should reflect the equitable distribution of commodities (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2014; Garraty Reference Garraty2009; Hirth Reference Hirth1998). However, we modify the distributional approach using the concepts of open and restricted markets.

Open Markets

Archaeological correlates for open market exchange are visible in qualitatively homogeneous consumption and production of materials across households (see Table 1), meaning that no categorical differences will be visible in artifact densities or source materials across households (Braswell Reference Braswell, Garraty and Stark2010:132; Hirth Reference Hirth1998:455; Johnson Reference Johnson2016; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016:158). In open markets, commoners feel safe engaging in exchange at broader social scales, including visiting nonlocal markets or buying from nonlocal merchants. This limits the degree to which elites can monopolize high-order exchanges. All households will have access to nonlocal goods, including ordinary goods and luxuries, circulating at the regional and macroregional scales. For example, in the LPC southern Basin of Mexico, Brumfiel (Reference Brumfiel, Claessen and van de Velde1991) found both rural and urban low-status households were well supplied with green obsidian, and those rural households directly administered by the Aztec state had slightly better access to green obsidian than those governed by local rulers. Open markets may also be identified by production and consumption practices that are exceptionally varied, meaning households are producing surplus on such a large and varied scale that one can infer market exchange based on the presence of an economic system too complex and diverse to be organized by a central institution (Feinman and Nicholas Reference Feinman, Nicholas, Manzanilla and Hirth2011; Levine Reference Levine2011; Levine et al. Reference Levine, Fargher, Cecil and Ford2015; Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012).

Table 1. Types of Exchanges Based on Embedded (“Non-Market”) or Commercial Relationships (Market Systems).

Restricted Markets

Archaeological correlates for restricted forms of exchange are visible in equal consumption of only locally produced ordinary goods across all households, with consumption of higher-quality, higher-cost, or politically charged items (exotics and nonlocal goods) limited to high-status households (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016). Thus, a stratified market develops, featuring local marketplaces with limited institutional development for cooperation, so that trust is based on familiarity and reputation, and exchanges are limited to locally produced and consumed goods. Elites monopolize exchanges at larger geographical scales, involving more exotic goods. Social embedding is key to these exchanges. Thus, elite social relationships are reinforced by the restricted exchange of prestige goods. Archaeologically, restricted markets will be materialized in the form of relatively homogeneous distributions of low-value goods over limited geographic scales (e.g., within sites or over a comparatively small territory); whereas, special, costly, nonlocal goods and raw materials should be distributed over very large areas (>100 km2) but restricted to higher-status households.

Reciprocal Exchange

Reciprocity involves low-volume, heterogeneous exchange spheres representative of households with unique social networks and procurement strategies (Braswell Reference Braswell, Garraty and Stark2010:132; Hirth Reference Hirth1998:455; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016:158). Surplus production of goods would be reduced in this system in comparison with market exchange or to centralized redistribution, since consumption is geared only toward one's own social network. Given that each household would have had its own procurement system, distinct patchworks of goods and raw materials would be visible archaeologically.

However, for low-status households, reciprocity in the absence of larger integrating mechanisms (e.g., open markets) will only provide access to local goods; whereas, high-status political agents will be connected to regional and macroregional networks. Principals and other high-level political actors develop social ties well beyond local borders, manipulating these relationships to control access to and the sale of regional or world-systems goods within settlements and their immediate hinterlands (Blanton Reference Blanton, Hirth and Pillsbury2013; Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016). In this manner, social embedding through reciprocal exchange is key to the development of restricted markets.

The merging of reciprocal exchange with restricted markets will result in three exchange spheres operating simultaneously. At the highest level, rare or singular items will be concentrated among rulers and the highest governing officials (e.g., polychrome vessels with their owners named; gold, silver, and tumbaga composite jewelry; rock-crystal chalices; and eccentrics of various materials that promote rulership, etc.). Next, a specific set of commodities, usually nonlocal goods and craft items that are difficult to produce (such as jade beads and other forms, elaborate polychromes, plumbate, codices, metal axe-monies, copper and bronze jewelry, and artifacts made using nonlocal materials, etc.) will flow through restricted markets and be most frequent in high-status contexts and taper off as these goods move down the social hierarchy. Finally, locally produced commodities made with comparatively simple techniques (e.g., low-fired monochrome jars and comales, staple foods, chipped tools made on local materials, wooden artifacts, and textiles made from locally produced fibers) will be widely distributed.

Redistribution

Redistribution will be visible in the households of governing officials having the greatest quantity of items, with comparatively fewer goods possessed by low-status households, thereby reflecting the established social hierarchy (Braswell Reference Braswell, Garraty and Stark2010:132; Hirth Reference Hirth1998:455; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016:158). The basic goods possessed by everyone would be the same, meaning access is not stratified. In this model, tools and local raw materials would be homogeneous, yet elites would have the same tools made on the same local materials, in larger volumes, with production limited to a few locations either within or near settlements. Braswell (Reference Braswell, Smith and Berdan2003:157) identifies redistribution at Postclassic Otumba, Mexico. Workshops at the site were primarily exploiting local gray Otumba obsidian, which was predominantly consumed by rural households. In contrast, urban high-status households were consuming predominantly green Pachuca obsidian alongside some local gray, and several lower-status urban households were consuming a mixture of both Otumba and Pachuca obsidian. This scenario is interpreted as controlled distribution (redistribution; Braswell Reference Braswell, Smith and Berdan2003).

Exploring Market Restriction in Postclassic Mesoamerica

Based on the preceding, we hypothesize that in Postclassic Mesoamerica, collective political-economic strategies will be associated with open markets and that exclusionary strategies will be associated with either reciprocity or a combination of restricted markets and reciprocal exchange. We selected two well-studied cities from the LPC—Chetumal and Tlaxcalla—to test these hypotheses. Both cities have extensive ethnohistoric documentation, household excavations, and well-classified assemblages.

Chetumal

Political Strategies

The political organization of Maya polities varied at the time of conquest (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992, Reference Chase1982; Fox et. al 1996; Landa Reference Landa and Pagden1975 [1566]; Masson Reference Masson2000; Oland Reference Oland and Walker2016; Roys Reference Roys1957). The Chetumal polity was organized as a kuchkabal, under the rulership of a halach winik named Nachan Kan (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain1948:100; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1988; Landa Reference Landa and Pagden1975 [1566]:33; Masson Reference Masson2000; Oland Reference Oland and Walker2016). As a kuchkabal, the Chetumal polity was organized into at least three settlement tiers. The highest tier was the noh kah (“capital”) at Chetumal, recognized archaeologically as the site of Santa Rita Corozal (SRC), Belize (Chase Reference Chase1982; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1988). Below it were batabil; they were governed by batabob (Oland Reference Oland and Walker2016:109), which controlled small local settlements or neighborhoods called cah (pl. cahob; e.g., Chase Reference Chase, Robertson and Fields1985:223–233).

Artifact patterns, ethnohistoric accounts, and architecture suggest that the halach winik sought to integrate and control lower-level elites through domination of ideological resources (e.g., ritual knowledge, including possible esoteric/exotic languages based on specialized linguistic puns; see Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2008; Roys Reference Roys1933; Stross Reference Stross1983). Batabob in turn manipulated ritual at the local level to bring low-status households under their authority. As a result, Postclassic elites were unable to build larger networks, because personal power placed structural limits on the geographical scale of integration (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008), resulting in a high degree of fragmentation and power sharing among a limited number of individuals or lineages (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Cook and Demarest1996). Thus, although Nachan Kan was the halach winik, Chase and Chase (Reference Chase and Chase1988) suggest that decision-making authority rotated among elite households or lineages.

Consequently, religious shrines, ritual caches, and paired censers used in calendric rites, as well as other religious paraphernalia, such as stingray spines, were reported to be restricted to high-status houses or nonresidential structures (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992:128). For example, caches with iconographic links to Itzamna were placed in altars and high-status residences in accordance with Wayeb rites for the Kan years in the northeastern part of the site (Chase Reference Chase, Robertson and Fields1985:228; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2008). In the southwestern part, similar caching is associated with rites involving the Muluc years, warriors, the war dance, and the sun god (Kinich Ajaw). Taube (Reference Taube, Vail and Hernández2010:161) notes a severed head of Kinich Ajaw portrayed with dancing warriors on the west wall mural at Chetumal. Rites associated with the Ix and Cauac years have been tentatively identified in other sectors (Chase Reference Chase, Robertson and Fields1985:233). Importantly, projectile points appear in the plumed serpent imagery on murals, such as in Mound 1 (Taube Reference Taube, Vail and Hernández2010:177). Quetzalcoatl and Itzamna, who were often associated with royalty in Postclassic iconography (Taube Reference Taube1989; Reference Taube, Vail and Hernández2010), appear in mural iconography, signaling an emphasis on royal lineages, personalized rulership, hereditary power, and social hierarchies (Olko Reference Olko2014; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Negrón and Bey1998; cf., Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010).

Hence, we might expect to see specialized ritual artifacts materialize this pattern by being concentrated in the largest and wealthiest houses (those of the halach winik and high-level batabob), with smaller amounts appearing in middle-level households and few or none appearing in low-status houses. This pattern might be manifested in the form of a monopoly on raw materials, on specialized artifact forms, or on both (see Peregrine Reference Peregrine1991).

Economics and Exchange at Chetumal

Substantial evidence exists at Chetumal for high-value trade items in high-status contexts, including conspicuously crafted items like metals, textiles, ceramics, polished lapidaries, and eccentrics (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1988). These items served as important symbols and as social capital, irrespective of material source (see Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986). Specifically, evidence indicates that obsidian and fine chalcedony projectile points are concentrated in high-status houses and contexts, suggesting that some may have served as potent ritual items (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992). Lithic materials were overwhelmingly comprised of cherts and chalcedonies, with obsidian recovered in lower frequencies. The most common siliceous tools were bifaces and small, triangular side-notched projectile points (<3 cm in length, <1 g in weight) with either short or elongated blades (Meissner Reference Meissner2014). Such points, common throughout LPC Mesoamerica, are associated with bow-and-arrow technology (Andresen Reference Andresen, Hester and Hammond1976; Meissner and Rice Reference Meissner and Rice2015; Shafer and Hester Reference Shafer and Hester1988; Thomas Reference Thomas1978). Obsidian tools were primarily prismatic blades; despite these patterns, obsidian points seem to have played a special political-economic role (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992:123).

The Corozal Postclassic Project excavated 43 structures, of which 35 yielded architecture or occupation surfaces dated to the LPC (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992:123). High-status households were previously identified by their association with items referencing ritual performance, including effigy censers, paired incense burners, and other ritual paraphernalia relating to bloodletting, such as stingray spines (Chase Reference Chase, Robertson and Fields1985). They also contained complex multiroom architecture and more diverse artifact assemblages (Chase Reference Chase, Robertson and Fields1985), a pattern noted in elite households throughout Mesoamerica (Hirth Reference Hirth, Santley and Hirth1993). Households of other-status lacked these ritual items and multiroom constructions (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992).

Of these 35 contexts, 286 projectile points were found in 30 structures, including 14 high-status houses, 10 other-status (either low or middle) households, and six ritual contexts (Meissner Reference Meissner2014; Seidita Reference Seidita2015). Yet only 33 points were made of obsidian (Figure 2), a nonlocal resource originating from Highland Guatemala (500 km away) and Highland Mexico (1,000 km away; Seidita Reference Seidita2015; Seidita et al. Reference Seidita, Chase and Chase2018). The other 253 points were made from locally available resources, including northern Belize chert associated with Colha (Shafer and Hester Reference Shafer and Hester1988), chalcedony likely from Caye Coco and the Laguna de On area (Masson Reference Masson2000), and other lower-quality cherts from unknown sources located throughout northern Belize (Oland Reference Oland1999, Reference Oland2013).

Figure 2. Typical obsidian side-notched points from Santa Rita Corozal (Meissner Reference Meissner2014:345, Figure 6.20).

Following Hirth's (Reference Hirth1998) distributional approach for identifying markets (see also Braswell Reference Braswell, Garraty and Stark2010; Garraty Reference Garraty2009; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016; Stark and Garraty Reference Stark, Ossa, Garraty and Stark2010), we tested the degree to which households had homogeneous access to projectile points. Specifically, we compared households containing obsidian points to those containing siliceous points using a contingency table analysis and Fisher's Exact Test. Results suggest that lower-quality chert points were uniformly distributed among houses, regardless of status differences (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.51, df = 1, n = 21), including Colha chert (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.58, df = 1, n = 21; see Figure 3a). Furthermore, the distribution of chert points among “civic/ritual” contexts, “high-status” contexts, and “other-status” contexts was subjected to a one-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA). We performed this test on the total number of chert points recovered per context, and the total number of points divided by each excavation surface area, to normalize differences in excavation size; the test results were not significant. We ran post hoc t-tests to assess for differences between “other-status” and “high-status”; again, there was no difference (see Table 2).

Figure 3. Projectile point distribution at Santa Rita Corozal (SRC): (a) Santa Rita Corozal number of households with chert points by status; (b) Santa Rita Corozal number of households with obsidian points by status.

Table 2. Santa Rita Corozal Chert Point Statistical Summary.

Note: S.A. = surface area.

In contrast, obsidian points show a skewed spatial distribution among households (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.023, df = 1, n = 21; Figure 3b). These points are concentrated in the highest-status houses, with a smaller amount appearing in intermediate-status houses and almost none in lowest-status houses. Yet, no significant difference in obsidian blade consumption was observed among these households (Seidita Reference Seidita2015). Obsidian (n = 576) recovered at Postclassic Santa Rita Corozal, including a sample analyzed with pXRF (n = 536; Seidita et al. Reference Seidita, Chase and Chase2018), indicated that all households had access to obsidian. Thus, obsidian points were restricted for social reasons and not because they were too costly for low-status households. Similarly, chalcedony points were also partially restricted to high-status houses (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.1, df = 1, n = 21).

Some metals were also likely exchanged in restricted markets at Chetumal. Gold (e.g., beads, foil) and silver (e.g., bells) commodities, along with rarer gold and silver artifacts that probably were gifts, were only found in high-status households—including those of the halach winik (see Chase Reference Chase, Sabloff and Wyllys Andrews1986:20; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1988:20). Comparatively, gold adornments were highly restricted in Aztec Mexico; these items identified the owner as possessing significant authority and power that lesser elites did not possess (Chase Reference Chase, Sabloff and Wyllys Andrews1986:20).

Interestingly, the likely residence of a principal and one other high-status house contained the highest number of obsidian and chert points (Chase Reference Chase, Sabloff and Wyllys Andrews1986:355). Examination of the chert debitage (n = 2,449) recovered from these high-status households determined that higher-quality cherts were not controlled at these locations (Marino et al. Reference Marino, Martindale Johnson, Meissner and Walker2016). When combined with the broader lithic dataset, it becomes clear that neither higher-quality cherts, obsidian blades, nor chert points were restricted.

Tlaxcallan

Political Strategies

Ethnohistoric and archaeological evidence indicate that Tlaxcallan encompassed 1,400 km2 and housed 250,000–300,000 people (Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010; Fargher, Blanton, et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton, Heredia Espinoza, Millhauser, Xiuhtecutli and Overholtzer2011). The largest settlement within Tlaxcallan was the densely occupied, 450 ha eponymous hilltop city (Figure 4). Spatial patterns coupled with ethnohistoric information indicate that it was organized in three districts (or sing. teccalli, pl. teccalleque) that were subdivided into neighborhoods (tlaca). Each teccalli was governed by a teuhctli (a titled noble), who probably acceded to his position based on merit, but heredity may have figured in an individual's success (Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010). The teteuctin (pl. of teuhctli) of these districts were important members of Tlaxcallan's ruling council.

Figure 4. Late Postclassic city of Tlaxcallan, with neighborhoods mentioned in text (Fargher, Blanton, et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton, Heredia Espinoza, Millhauser, Xiuhtecutli and Overholtzer2011).

Tlaxcallan's ruling council consisted of 50–250 members, all of whom gained their positions principally through merit accumulated by service to the state. Military service, commercial success, and religious service were the most important pathways to these positions (Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010). This council was the supreme governing authority, and all Tlaxcaltecans were under its jurisdiction. The council elected officials and monitored their official behavior; it also determined the state's political policies, including declaring war and trying high-level officials for crimes. It could sentence any Tlaxcaltecan citizen regardless of their social position (see Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010). Each teuhctli administered a district (teccalli), including tax and tribute collection, organization of military corvée, policing, and public goods supply (Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010).

On the basis of cross-cultural research (e.g., Blanton Reference Blanton, Hirth and Pillsbury2013; Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016; Fargher Reference Fargher2009), we hypothesize that the high degree of collectivity described in early colonial documents was materialized in open and accessible public spaces, where citizens could gather to participate in large collective rituals, attend open markets, and interact personally with governing officials; there was also a wide distribution of both nonlocal materials and elaborate artifacts with little emphasis on monopolies over luxury items. Systematic survey (Fargher, Blanton, et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton, Heredia Espinoza, Millhauser, Xiuhtecutli and Overholtzer2011) demonstrated that this collective organization was materialized in architectural styles that emphasized open, unrestrictive, public spaces coupled with a deemphasis on individual wealth as expressed in the form of elaborate palaces in central locations. Excavations in key public spaces (in and around temples) have demonstrated that elaborate burials typical of aggrandizing elites in other parts of Mesoamerica were not placed in these structures (Caso Reference Caso1927; Contreras Reference Contreras1992; Noguera Reference Noguera1929). Elaborate items and exotic materials, such as polychrome pottery and green obsidian, were widely distributed throughout the site and were not concentrated in “high-status” residences (Fargher, Blanton, et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton, Heredia Espinoza, Millhauser, Xiuhtecutli and Overholtzer2011; Fargher, Heredia, and Blanton Reference Fargher, Blanton, Heredia Espinoza, Millhauser, Xiuhtecutli and Overholtzer2011).

Iconography on both murals and codex-style polychrome pottery corresponds with architectural patterns. Specifically, the Tizatlan and Tlaxcallan (Ocotelulco) murals focus on themes associated with death, sacrifice, warfare, and the gods of night and death. At Tizatlan, the west altar depicts Tezcatlipoca, a god associated with merit and the value of persons regardless of ascribed status, and the Tlaltecuhtli-Tzitzimimeh complex, which references droughts, epidemics, war, death, and destruction (Caso Reference Caso1927; López Corral et al. Reference López Corral, Almanza, Ibarra Narváez and Cano2019:345). The east altar depicts Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli and Xiucoatl, indicating themes of sacrifice, captives (defeated warriors), and war (Caso Reference Caso1927; Jordan Reference Jordan2013:248). The Ocotelulco mural shows the birth of Tezcatlipoca surrounded by the Tlaltecuhtli-Tzitzimimeh complex (Contreras Reference Contreras1992; López Corral et al. Reference López Corral, Almanza, Ibarra Narváez and Cano2019:345).

Iconography on polychrome pottery includes the Tlaltecuhtli-Tzitzimimeh complex, among several others. The Xochicuica-Xochilhuitl complex is associated with ceremonies, ritual acts, and Xochipilli. The Feathers and Flowers complex references cuauhxochitl (eagle-flower) and chimalxochitl (shield-flower), invoking warrior songs and battlefields. The War, Sacrifice, and Nobility complex indicates birds, jaguars, government, and warriors, as well as aztaxelli (feathered headdresses) worn by Tlaxcaltecan warriors in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala. The Teocuitlatl complex implies divinity, foodstuffs for the gods of the night (Tezcatlipoca, Mezti, Mictlantecuhtli), and sacrifice. Lastly, the Mictlan complex references Mictlantecuhtli, the underworld, and darkness (López Corral et al. Reference López Corral, Almanza, Ibarra Narváez and Cano2019:340–346). Thus, the themes on murals and polychrome pottery emphasize service, sacrifice, warfare, death, ritual, merit, and the gods of night, instead of individuals and royal lineages (Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010; López Corral et al. Reference López Corral, Almanza, Ibarra Narváez and Cano2019). Such themes are consistent with descriptions in early colonial documents concerning rituals, religion, and ideology (Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010).

Economics and Exchange

Excavations and systematic survey indicate that much of the hilltop city was terraced using tepetate, a naturally occurring sediment, which makes poor arable (Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza2010). Thus, agriculture was displaced to the valleys that surround Tlaxcallan. Because the site is several hundred meters above zones with quality arable needed for farming, households would have engaged in craft production, including multicrafting (see Costin Reference Costin, Feinman and Douglas Price2001; Hirth Reference Hirth and Hirth2010), to provide income to purchase commodities in the city's numerous marketplaces and to pay taxes (see also López and Hirth Reference López Corral and Hirth2012). In his second letter, Cortés (Reference Cortés2007 [1522]:67) noted craft items, including pottery, feathers, lapidaries, gold, silver, precious stones, and textiles, for sale in the market at Ocotelulco, Tlaxcallan, which he estimated served many thousands of people. Cortés (Reference Cortés2007 [1522]:67) also stated that multiple marketplaces existed in Tlaxcallan. This pattern may indicate a more decentralized and open market system (see Hirth Reference Hirth2016:71). Cortés (Reference Cortés2007 [1522]; see also Zorita Reference Zorita and Keen1963 [1585]:152–154) also mentioned the presence of judges and police in the market, which would imply state investment in market security.

Archaeological data are consistent with these descriptions. The primary lithic materials recovered by the Tlaxcallan Archaeological Project were obsidian tools and debitage. PXRF analysis demonstrates that multiple sources supplied Tlaxcallan markets with obsidian nodules and prismatic cores (López Corral et al. Reference López Corral, Vera Ortiz, Cano, Hirth and Dyrdahl2015; Millhauser et al. Reference Millhauser, Fargher, Espinoza Heredia and Blanton2015). Importantly, all sources were located outside the borders of the Tlaxcaltecan polity, with most under Aztec control or in disputed regions. The most-used source by Tlaxcaltecans, El Paredón, sits roughly 70 km away in a zone nominally under Aztec supervision; whereas, green obsidian, the next most common material, originated well within the Aztec empire at a distance of approximately 100 km. Because obsidian crossed international boundaries or was purchased in enemy marketplaces, we consider it to be imported and nonlocal.

Currently, 21,000 obsidian artifacts have been analyzed, including 95 projectile points (Figure 5). However, we limited our analysis to points associated with structures (n = 50). These materials were recovered from a terrace with a public function located in the Quiahuixtlan district, three “other-status” houses in the Ocotelulco district, and two houses located in the Tepeticpac district, one of possibly “high-status” (El Fuerte Terrace [EFT.] 30) and one of “other-status.” Status determination is difficult, because extensive excavations have demonstrated that wealth inequality is highly compressed at Tlaxcallan, houses are very homogeneous, and traditional status markers are absent. We identify EFT. 30 as a possible “high-status” context because it is slightly larger than all the other excavated residences and has a slightly larger and nicer talud façade fronting one room (see Fargher et al. Reference Fargher, Antorcha-Pedemonte, Heredia Espinoza, Blanton, Corral, Cook, Millhauser, Marino, Rojo, Alcantara and Costa2020). Overall, structural contexts in each of the three districts are represented in our study; we excavated one high-status, four lower-middle status, and one public space (Figure 6a).

Figure 5. Typical obsidian side-notched projectile points from Tlaxcallan, Mexico.

Figure 6. Projectile point distribution at Tlaxcallan: (a) Tlaxcallan structures by area; (b) Tlaxcallan structures by Postclassic points; (c) Tlaxcallan structures by ratio of Postclassic points to area.

Projectile points were recovered in all of these contexts, indicating that all households had comparatively equal access to obsidian projectile points. Interestingly, a chi-square test reveals a significant difference in consumption of points among households (χ2 = 18.16, p = 0.002, df = 5, n = 50; Figure 6b,c). The house (Ocotelulco T.6, Str. 1) that contains a significantly higher amount of points (n = 18) is a comparatively humble residence with about half the surface area of the “high-status” house on EFT. 30 (Figure 6a,b). In fact, 50% of structures excavated at Tlaxcallan have equal or more points than those found in the high-status context (EFT. 30), despite all being comparatively smaller and having smaller excavation volumes. When Ocotelulco Structure 1 is removed from the sample, no pattern emerges in the consumption of Tlaxcaltecan projectile points (χ2 = 6.125, p = 0.19, df = 4, n = 32).

Discussion

The distribution of points at Chetumal suggests that lithic resources used during the LPC arrived through both local and long-distance networks. Importantly, locally available siliceous materials and the points made from them were widely available across social sectors. This is consistent with local markets and household-based provisioning for auto-consumption. The pattern of consumption for chert points is similar to that of obsidian blades, which indicates market-based distribution (Marino et al. Reference Marino, Martindale Johnson, Meissner and Walker2016; Seidita et al. Reference Seidita, Chase and Chase2018). Small, side-notched chert projectile points were produced on flakes and blades, and these resources were not controlled. Their production and consumption are visible in high-status residential contexts, ritual contexts, and in lower-status contexts (Meissner Reference Meissner2014:416–420).

Obsidian points, made using nonlocal materials, were more restricted to higher-status houses and ritual contexts (along with stingray spines, gold beads and foil, and silver bells), likely reflecting their monopolization for esoteric rituals or other activities conducted by political actors (e.g., the halach winik and batabob). It is significant that the obsidian used to make these items is not restricted, as evidenced by the equitable consumption of obsidian blades among all houses. Instead, it is the specific tool form in conjunction with foreign material that was restricted. This is suggestive of a bifurcated distribution system, which is consistent with restricted market transactions (Blanton Reference Blanton, Hirth and Pillsbury2013; Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016; LeCount Reference LeCount, Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016).

At Tlaxcallan, it is clear that high-status individuals did not monopolize access to obsidian projectile points or other nonlocal items (e.g., gold, silver, precious stones, fancy pottery) and that lower-status houses had access to them. All of the obsidian was imported, which suggests that large numbers of individuals had access to nonlocal materials and goods across social sectors and geographic space. Such a pattern is consistent with “open” markets and market management strategies designed to resolve cooperation problems and encourage exchange among strangers, foreigners, and locals, as well as across social sectors. Thus, in contrast to Chetumal, obsidian projectile points at Tlaxcallan were not an important political currency.

Energy investments are needed to establish and maintain trade networks and distribution systems. The origin of such investments is important in identifying whether such systems were (1) manipulated for political gains and oriented toward the interests of specific individuals competing for economic and political power through exclusionary strategies, or (2) oriented toward promoting cooperation across social sectors to increase market revenues as part of collective political-economic strategies. At Chetumal, the primary form of social and economic investment came from high-status political actors, as indicated by both ethnohistoric and archaeological data. Consistent with theory (Blanton et al. Reference Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski and Peregrine1996; D'Altroy and Earle Reference D'Altroy and Earle1985), elite-centered networks were materialized in the patterned consumption of many high-status goods, including obsidian projectile points. Paradigms also predict that open markets and open exchange networks are provided to constituents as a public good in societies where the interests of many are considered (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016; Carballo and Feinman Reference Carballo and Feinman2016). In the case of Tlaxcallan, ethnohistoric accounts indicate that collective strategies were used. Theoretical patterns associated with such political strategies are supported by our economic data, which indicate that formal tools made from exotic materials (like obsidian projectile points) were accessible through open market systems and distributed across social sectors. Thus, governing officials did not monopolize them for use in exclusionary rituals.

Conclusion

Comparing LPC Tlaxcallan with LPC Chetumal demonstrates major differences in production and exchange. At Chetumal, a multitiered economy existed, in which obsidian points and other politically charged artifacts were likely used as one of several high-status items to promote monopolies over ideological resources. Such data suggest limits on access to ritual knowledge, socially embedded exchange networks, and stratified consumption (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992; Hirth Reference Hirth, Chase and Chase1992; McAnany Reference McAnany, Hirth and Pillsbury2013), all of which are important characteristics of restricted markets (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016:69–98). In contrast, such controls may not have played a role in the legitimization strategies employed by governing officials at Tlaxcallan. Data from Tlaxcallan demonstrate that the state did not monopolize or manipulate the distribution of nonlocal or elaborated artifacts. All terraces and households had access in comparable amounts, which indicates that exclusionary control by high-status households was minimal. Thus, we suggest that Tlaxcaltecan officials promoted market services, which facilitated the development of open markets, and a more homogeneous distribution of goods as compared with Chetumal. In his description of the Ocotelulco market in Tlaxcallan, Cortés noted that commercial transactions occurred both within the Ocotelulco market and in various other plazas dispersed throughout the city. It is clear from these descriptions that public goods/services were provided to market attendees in the form of market infrastructure, including market security (e.g., judges and police [topiles]), marketplaces (plazas), and temples. These patterns indicate that diverse political strategies, such as elite-centered personalization of power versus collective action, differentially affect market development and the distribution of luxury or ritually charged goods.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Diane and Arlen Chase for use of SRC datasets in several theses, papers, and dissertations. We thank Belize's Institute of Archaeology and the Instituto Nacional de Antrología e Historia (INAH) for permits. We thank Aurelio López for continually providing lab space and assistance. The Tlaxcalan Mapping Project and the Tlaxcallan Archaeological Project were funded by Conacyt (Grant CB-2014-236004), the National Science Foundation (Grants 0809643-BCS, 1450630-BCS), the National Geographic Society (Grant # 8008–06), and the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. The SRC data were collected by the Corozal Postclassic Project directed by D. Z. Chase and A. F. Chase with funding from the National Science Foundation (Grant 8509304-BNS, Grant 8318531-BNS) to D. Z. Chase and A. F. Chase. No financial or institutional conflicts of interest exist.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the published sources cited within. Project reports, compiled by the Tlaxcallan Archaeological Project, are available through INAH.