In June 1902, the Smithsonian Institution received a letter from Alfred Bishop Mason addressed to “Manager Archaeological Department.” Mason was president of the Vera Cruz and Pacific Railroad, which he built under a concession from the Mexican government to join the city of Veracruz to Salina Cruz on the southern coast of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. On stationery of the Ferrocarril de Veracruz al Pacifico, Oficina del Presidente, he wrote that he was sending two photographs of a “Jade Idol which was dug up by the plow in the district of San Andrés Tuxtla on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, about 100 miles southeast of Veracruz.” Mason's letter was delivered to William Henry Holmes, then chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution.

This object, which the Smithsonian ultimately purchased, came to be known as the Tuxtla Statuette (Figure 1). The name seems to have originated in the extensive comments by Sylvanus Morley, then an undergraduate student of archaeology at Harvard, who referred to it descriptively as “the Tuxtla statuette” 11 times in an extensive commentary quoted by Holmes (Reference Holmes1907:696–700). By 1914, Morley had come to treat this standard way of referring to the statuette as a proper name and so used “Tuxtla Statuette” throughout his monograph on Mayan hieroglyphic writing (Morley Reference Morley1915:179, 194–196). Thereafter, this was the standard practice.

Figure 1. The Tuxtla Statuette. Dimensions: height 15 cm, width at base 10 cm, depth across base 8.2 cm (Washington Reference Washington1922:3). (Photograph by Peter Selverstone and John Justeson, spring 1999, with the assistance of Loa Traxler; drawing by Justeson [Justeson and Kaufman Reference Justeson and Kaufman1993:Figure 3].) (Color online)

The statuette was noteworthy at the time of Holmes's publication as a unique artifact, bearing a hieroglyphic text in a writing system distinct from Mayan, but sharing with Mayan writing alone both the long count calendar and a system of positional numerical notation, and bearing the earliest then-known long count date. According to Justeson and Kaufman, it documents epi-Olmec religious practices (Justeson and Kaufman Reference Justeson, Kaufman, Kettunen, López, Kupprat, Lorenzo, Cosme and Ponce de León2018; Kaufman and Justeson Reference Kaufman and Justeson2001). It is one of only a dozen objects known to bear a text in this script and, as one of the longest and most legible, has been crucial in work toward its decipherment (e.g., Anderson Reference Anderson1993; Ayala Reference Ayala, Ochoa and Lee1983; Justeson and Kaufman Reference Justeson and Kaufman1993, Reference Justeson, Kaufman, Arnold and Pool2008, Reference Loughlin2018; Macri Reference Macri, Smith and Schmidt1991; Macri and Stark Reference Macri and Stark1993; Méluzin Reference Méluzin1992, Reference Méluzin1995; Winfield Capitaine Reference Capitaine1988).

Holmes devoted most of his paper to comments solicited from leading American authorities on Mayan epigraphy. Only Charles Peabody Bowditch, an eminent authority of the day, recognized that its hieroglyphic text was not Mayan, writing

I have made careful researches regarding these glyphs and have compared them with a card catalog (which I have had made for my own use) of all the glyphs contained in the three Maya manuscripts. . . . I can not find any real likeness between the two kinds of glyphs [Holmes Reference Holmes1907:695].

Bowditch was correct. Inscriptions in the same script are now known from 11 other objects.Footnote 1 Two in private collections have uncertain provenience, but the others are first-century BC to sixth-century AD texts discovered in or near sites with Late Formative (400–1 BC) to Protoclassic (AD 1–300) epi-Olmec occupations, as defined archaeologically (e.g., Lowe Reference Lowe, Sharer and Grove1988:61–65): in and around Chiapa de Corzo in the southern focus of epi-Olmec culture and otherwise in its northern focus in the Papaloapan basin, from Tres Zapotes northwestward to the Mixtequilla.

In a July 11, 1902, letter addressed to W[illiam] de C[hastignier] Ravenel, an administrative assistant at the Smithsonian, Mason wrote, “The idol in question does not belong to me, but to a Mexican friend of mine. I have been trying to get possession of the idol for the Smithsonian Institution, but as yet he has declined to part with it.” Later, Holmes was contacted by R[ichard] E[mil] Ulbricht, then a certified public accountant for various banking and railroad interests. Ulbricht wrote on July 4, 1903, for “a friend of mine in Orizaba, Mexico,” whom he said “showed me an old—as he believes—Aztec idol.”

Following this letter is a string of correspondence between Holmes and Ulbricht, and between Holmes and his brother-in-law, who visited Ulbricht in New York. Eventually, Ulbricht apparently wrote to “a contact in Mexico,” otherwise identifiable as the owner of the statuette, requesting further information about how it was found and saying that some of the people at the Smithsonian thought it might not be genuine. This elicited what Ulbricht characterized as an “indignant” response from the owner, one F. Cházaro of Tlacotalpan, Veracruz, defending its authenticity. Details of the correspondence indicate that Cházaro was not only Ulbricht's friend in Orizaba but was also the statuette's owner. Ulbricht forwarded to Holmes an English translation of Cházaro's response in Ulbricht's handwriting (see Appendix A for a transcription). Ulbricht had the Spanish original of Cházaro's letter, which he offered to send to Holmes if requested, but we have not located it.

Holmes (Reference Holmes1907:692) stated that the Smithsonian acquired the statuette “after a brief correspondence carried on with a view to verifying the story of its discovery. . . . Every possible effort has been made to learn more of its history, but without avail.” This statement was wide of the mark. In defense of the statuette's authenticity, the English translation of Cházaro's letter states,

It was found by an indian while plowing a corn field in Hacienda de Hueyapam, Canton de Tuxtla, state of Vera Cruz. This hacienda belongs to my father in law, and no where around this place will you find any stone of that quality.Footnote 2 Very close to where this idol was found there is a very large one called “La Cabeza Colozal de Hueyapam,” which has been offered by my father in law to the Mexican Government for the Museum [Cházaro Reference Cházaro1904].

This “Cabeza Colozal” (now designated Monument A), the first of two Olmec colossal heads to be found at Tres Zapotes, was on the property of the Hacienda de Hueyapan. Cházaro's letter, then, is far more specific about the origin of the statuette than Mason's vague attribution to the “district of San Andrés Tuxtla.”

Had Holmes published Cházaro's more specific localization of the statuette, it should have been associated with Tres Zapotes at least from the time of Stirling's expedition to that site, in 1939. Instead, it acquired a name—“the Tuxtla Statuette”—that led to confusion about and misreporting of its origin. Holmes's discussion opens by quoting Mason that the statuette was found “in the district of San Andrés Tuxtla.” Mason's “district” translated cantón, and San Andrés was the head town of the Cantón de los Tuxtlas; it is in reference to the cantón that, for example, Blom and La Farge (Reference Blom and Farge1926:16) correctly reported the source of the statuette. Most attributions, however, have been either to the Tuxtla Mountains (e.g., Covarrubias Reference Covarrubias1946:86; Diehl Reference Diehl2004:184; Pool Reference Pool2007:40) or more specifically to the municipio (township) of San Andrés Tuxtla (e.g., Saville Reference Saville1929:278; Stirling Reference Stirling1939:183; Stuart Reference Stuart1993:1700; Winfield Capitaine Reference Winfield Capitaine1990:67). The second of the two “Tuxtlas” for which the cantón was named is Santiago Tuxtla, the municipio that contains Tres Zapotes and most of the lands belonging to the Hacienda de Hueyapan. Though the older of the two towns, having been founded in 1525, it was not designated a municipio until 1932, long after the municipio of San Andrés was formed in 1825.

Owner of the Statuette

The owner of the statuette at or shortly after the beginning of the Smithsonian correspondence can be shown to have been the F. Cházaro who wrote the letter presented in English translation in Appendix A.

In a letter to Holmes dated May 22, 1904, Ulbricht wrote, “I will at once write to the gentleman from whom I got it, and when his answer is received, I will send it to you.” He wrote to Cházaro on May 27, to an Orizaba address; his letter was eventually forwarded to Cházaro at his home in Tlacotalpan, and (F.) Cházaro replied on August 8. Ulbricht forwarded the reply to Holmes on September 20, writing, “I hand you herewith copy of my friend's letter.” Cházaro, then, was the person from whom Ulbricht had gotten the statuette.

Furthermore, in his May 22 letter, Ulbricht stated that “the gentleman who owned it was formerly in Mr. Mason's employ”; explaining the delay in his reply, Cházaro notes that he had left his job with the Vera Cruz and Pacific Railroad Company, whose offices were in Orizaba, in January 1904 (see Appendix A for relevant excerpts from the correspondence).

The F. Cházaro who owned the statuette can be identified specifically as Félix Prospero Cházaro Guzmán of Tlacotalpan, the only Cházaro who was a son-in-law of an owner of the Hacienda de Hueyapan.

A letter published in Siglo XIX on December 14, 1870 (republished by Rodríguez Prampolini [Reference Rodríguez Prampolini1997:162–163]), indicates that the owner of the Hacienda de Hueyapan, a brother of Venancio Benito Muriel, had recently died and left the property to his widow. Longinos Benito Muriel, who owned several haciendas, was the only brother of Venancio Benito Muriel; he left all his property to his wife María de la Cruz Muriel de Muriel, and Venancio served as her legal representative after her husband's death (Peralta Flores Reference Peralta Flores2005:34–38).

The next owner of the property was evidently Ramón López, a Spaniard from Santander, Cantabria, in northern Spain. López bought the hacienda at the urging of his son-in-law, Pedro Mimendi Camacho of Tlacotalpan (personal communication 2011, by the late Veracruz artist, Francisco Galí Malpica, a relative of the Mimendis), whose father was also a Spaniard (Bosch García Reference Bosch García1994:519). Mimendi assured López that he knew how to make it flourish through his own efforts; Galí states that they acquired the property “aproximademente en 1870.” López was the owner (propietario) of the Hacienda de Hueyapan until his death, after which it was inherited by his only child, Severa López Niño de Mimendi (Archivo General del Estado de Veracruz [AGEV] exp. 1436, f. 66), the wife of Pedro Mimendi Camacho. She remained its legal owner.

Nonetheless, Pedro Mimendi was universally known as the “dueño” of the Hacienda de Hueyapan—presumably in the meaning of “master/administrator,” rather than “owner.” He is known as such by his descendants (who are also descendants of Ramón López). In a letter dated March 27, 1897, Pedro Mimendi wrote to Guillermo Pous, then director of the Museo Nacional, to confirm third-party correspondence that he was offering to donate the colossal head of Hueyapan (i.e., of Tres Zapotes) to the museum (Archivo Histórico del Museo Nacional de Antropología [AHMNA], v.10, exp. 015, f. 61; cf. ff. 62–63). Seemingly, he had the authority to dispose of hacienda property, and García y Alva referred to Mimendi as “dueño de la Hacienda de Hueyapam” in a newspaper article referring to this donation (El Imparcial, May 9, 1909; Lombardo de Ruíz Reference Lombardo de Ruíz1994:2:533). Mimendi and his family left the hacienda headquarters at the onset of the Mexican Revolution of 1910; he later returned to deal with the hacienda's cattle holdings (Gutiérrez Vázquez Reference Gutiérrez Vázquez2010).

Pedro Mimendi Camacho had three daughters: Rosalia, María del Carmen Isabel (born July 8, 1877; also known by her relatives as María del Carmen and Carmen Isabel), and María. María del Carmen Mimendi López is the only one of Mimendi's daughters to marry a Cházaro. Her husband was Félix Cházaro Guzmán, born in Tlacotalpan on July 29, 1877; he lived there most of his life (Figure 2). There can be no doubt he was the F. Cházaro of Tlacotalpan who wrote to Holmes and who in 1902 was the owner of the Tuxtla Statuette.

Figure 2. The home of Félix Cházaro Guzmán in Tlacotalpan. (Photograph by Christopher A. Pool.) (Color online)

Members of the family today (Guadalupe Mimendi Porragas and Concepción Díaz Cházaro, personal communication 2011) tell us that Cházaro and María del Carmen Mimendi were committed to marrying for several years before their actual wedding, and that during this time Cházaro was treated by Pedro Mimendi as his son-in-law. They state that the wedding was delayed because Cházaro's work frequently took him away from home; the Smithsonian correspondence documents part of this absence, when he worked in Orizaba for the Ferrocarril Vera Cruz al Pacifico, at least from 1903 and perhaps during 1902 or earlier, when Mason was acquainted with him, returning to Tlacotalpan in January 1904. In his 1904 letter to Ulbricht, he referred to Mimendi as his father-in-law.

Félix Cházaro and María del Carmen Mimendi were married in Tlacotalpan on November 20, 1907, both at 30 years of age. They had two daughters: María del Carmen Cházaro Mimendi, born November 1, 1908, was named for her mother; and Felisa Cházaro Mimendi, born June 24, 1910, was named for her father. Figure 3 presents the relevant genealogical information.

Figure 3. Simplified genealogical chart of Hacienda de Hueyapan owners and their descendants.

Inasmuch as the statuette was found in one of Pedro Mimendi's cornfields and its location was known, Mimendi was presumably its original owner. The fact that Cházaro was associated with the statuette in 1902 and was its owner at least by sometime in 1903—four years before marrying Mimendi's daughter—shows that he did not own it by virtue of its being her property. This suggests that it had been a gift from either Pedro Mimendi or María del Carmen Mimendi. The letters indicate that Cházaro did not want to part with it, that he was particularly interested in finding out what its hieroglyphic text said, and that he had hopes that someone in the Museo Nacional or the Smithsonian might be able to decipher it. Considering that Pedro Mimendi had donated a collection of local artifacts to the Museo Nacional by 1892 (Paso y Troncoso Reference Paso y Troncoso1892:23) and had offered the colossal head to it in 1897 (AHMNA v.10, exp. 015, f. 61), we hazard that the gift reflected the two men's shared interest in Mexican antiquities and their cultural significance.

We do not know why Cházaro ultimately parted with the statuette—only that he gave it to Ulbricht and that Mason had been trying to induce Cházaro to give it to the Smithsonian. Given that Mason was Cházaro's employer at the time, he may have had some leverage in this regard.

Mapping the Hacienda de Hueyapan

This section addresses the key issue of this article, the location at which the Tuxtla Statuette was discovered.

How Close to the Colossal Head?

Cházaro stated that the statuette was found during the plowing of a cornfield on the hacienda lands, and, “Very close to where this idol was found there is a very large one called ’La Cabeza Colozal de Hueyapam’” (Cházaro Reference Cházaro1904).

The identification of the hacienda as the Hacienda de Hueyapan de Mimendi is confirmed in the demanda of April 24, 1923, by the residents of the Congregación de Tres Zapotes to form an ejido (communal agricultural collective), specifying that the lands to be affected belonged to the Hacienda de Hueyapan, property of Pedro Mimendi, and that the Cabeza Colosal de Hueyapan lay about 1,000 m from the village (poblado) of Tres Zapotes (Gaceta Oficial, Tomo XI, Num. 71, pp. 10–11; AGEV exp. 385, f. 26–27; cf. Taladoire Reference Taladoire2010). Stirling (Reference Stirling1943:17) identifies the head's location as Tres Zapotes Group 1; Weiant (Reference Weiant1943:Map 3, pp. 6–7) places it specifically on the southern edge of that group's plaza, a placement confirmed by Richard Stewart's photograph of the excavation (Figure 4) and Pool and Barba's (Reference Pool and Pingarron1999) topographic mapping of the plaza, which located the mostly filled-in excavation.

Figure 4. The Cabeza Colosal de Hueyapan (Tres Zapotes Monument A). (Photograph by Richard Stewart, Smithsonian Olmec Legacy Database, Catalog ID stirling_12.)

Although the Spanish original of Cházaro's Reference Cházaro1904 letter does not survive, the most likely words he used for “very close” are muy cerca or cerquita; in local Spanish, both terms indicate a location within eyeshot of a viewer (Terrence Kaufman, personal communication 2011, confirmed by Ortiz and Rodríguez). The find-spot was therefore most likely in or adjacent to the Middle Formative to Protoclassic mound-plaza Group 1 on the southwestern edge of the archaeological site of Tres Zapotes, whose period of occupation is consistent with the statuette's inscribed date, corresponding to AD 162.

According to Melgar y Serrano (Reference Melgar y Serrano1869:292), the head was found during clearing for a milpa; this was in the 1850s, “pocos años antes de” his visit in 1862; in 1870, El Fomento dated it more specifically as 1856 (Rodríguez Prampolini Reference Rodríguez Prampolini1997:162). Cházaro's phrasing—that there is a large idol near where this one was found—suggests two different times of discovery. We therefore believe that it was a subsequent plowing of this field or of one nearby that turned up the statuette. Seler-Sachs (Reference Seler-Sachs and Lehmann1922:544) reported that when she and Eduard Seler examined the head in 1905, it was in an area of tree growth (“im Walde”). The statuette may have been discovered long enough before 1905 that the field lay in fallow and was overgrown with secondary forest.

However, Stirling (Reference Stirling1939:188) thought that the statuette was found in 1902. While we are aware of no evidence to the contrary, a date of discovery does not appear in any of the surviving Smithsonian correspondence, which as far as we know is the only source of information about the circumstances of the discovery. Stirling may have had access to records now lost, but his errors concerning its origin suggest that he did not consult such files. We think it more likely that his statement arose through some confusion relating to the date of Mason's first letter about it. If Stirling's report is correct, the statuette would have to have been found in a field adjacent to or nearby the colossal head.

Alternatively, and much less restrictively, “very close” might have related the statuette's proximity to the colossal head relative to the overall extent of the hacienda. If so, we must assign an explicit interpretation to a vague measurement and also determine the bounds of the hacienda.

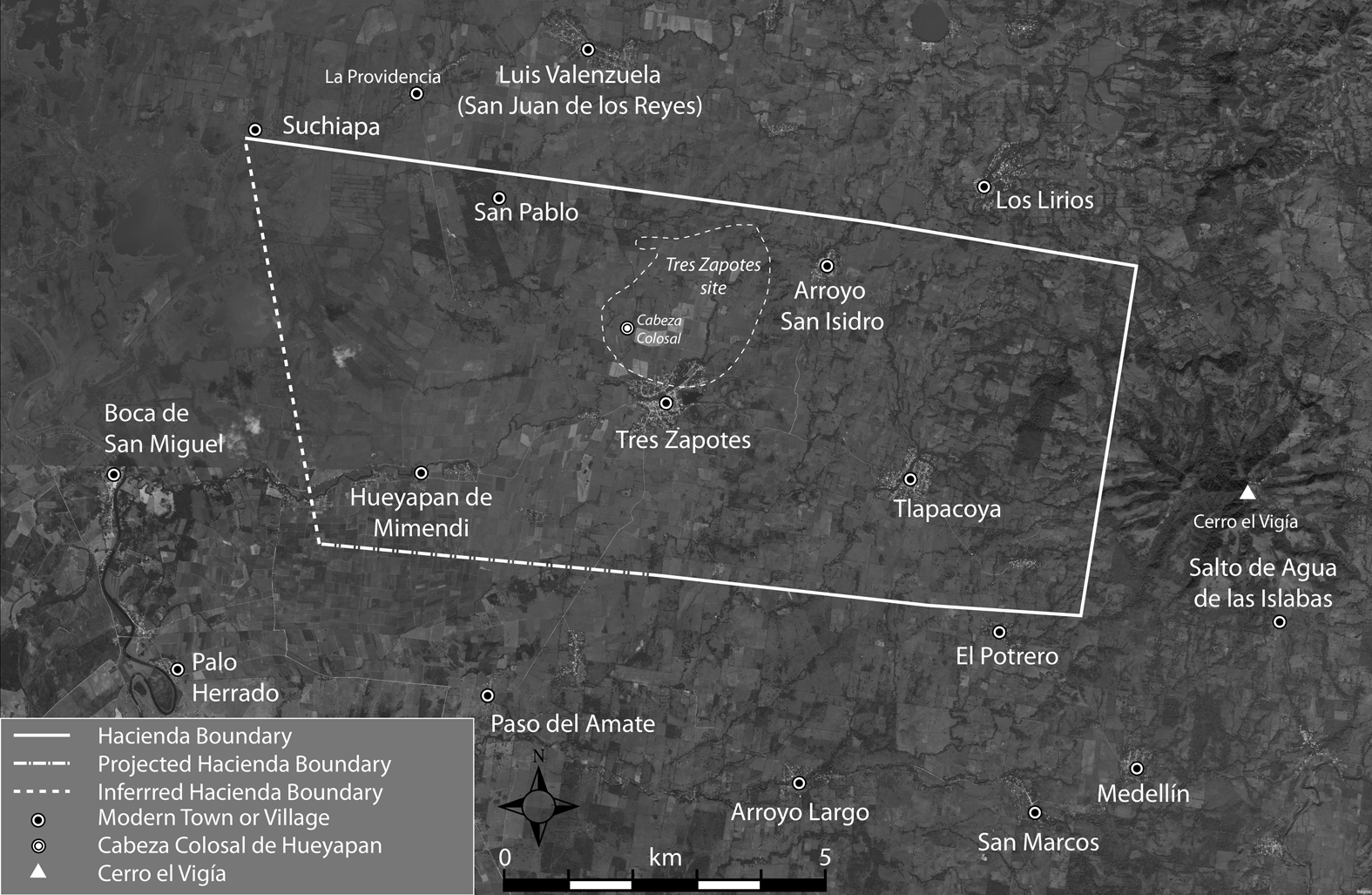

One feature of any explicit measure is straightforward; because the colossal head is relatively near the center of the hacienda lands (Figure 5), we treat the very farthest points on the hacienda from the colossal head, in any direction, as maximal distances, and being found right by the head as the minimal distance (= 0).

Figure 5. Map showing inferred boundaries of the Hacienda de Hueyapan, extent of the archaeological site of Tres Zapotes, location of the Cabeza Colosal de Hueyapan (Tres Zapotes Momument A), and locations of population centers for ejidos mentioned in the text.

Any specific “nearness” metric within these limits is conjectural, so we apply two: one we design to fit as precisely as possible the intuitive constraints on what “very close” should mean; the other we design to be overly broad.

(1) Intuitively, a closeness metric has three major divisions: near, far, and neither near nor far (i.e., intermediate). Because special pleading would be needed to justify specific unequal spans for these categories, we treat them for purposes of estimation as equal: that is, we treat “close” points as those that are at most one-third of the distance from the colossal head to the nearest boundary of the hacienda, and “distant” points as those at most one-third of the distance from the boundary toward the colossal head. This, however, is not a model for “very close”: applying the same three-way division—very close, moderately close, and less close—we model the zone that is at most one-ninth of the distance from the head to the nearest point on the hacienda boundary as a best explicit approximation to the part of the hacienda that would be straightforwardly characterized as being “very close” to the colossal head.

(2) Although the procedure described in (1) gives our best estimate for the region within which the statuette was found, we also calculate overly inclusive limits for the region within which it might have been found—that is, a zone whose limits are more distant from the colossal head, in every direction, than what the previous procedure would yield for cerquita or muy cerca. Such limits can be determined by dividing the hacienda lands between those that are nearer to the colossal head than to a hacienda boundary, and, correspondingly, treating as “very close” those points in the closer half of the “close” span, within one-fourth of the distance from the colossal head to the hacienda limits.

The Bounds of the Hacienda de Hueyapan

Félix Cházaro was, among other things, a surveyor and cartographer, and he produced a map of the hacienda that survived until very recently in his hometown of Tlacotalpan. Unfortunately, it was evidently lost in the floods that took place in the fall of 2010, only months before our visit in January 2011. One relative believes that a copy exists in the possession of another relative, but we have been unable to confirm this, and other relatives are skeptical about this possibility. We have not succeeded in locating this or any other map of the hacienda beyond those of dotaciones of lands for ejidos created from the hacienda.

Nonetheless, there is a good deal of information on which to base an approximation to the boundaries of the hacienda that should be sufficiently close for present purposes, based mainly on archival records and interviews with family members.

Areas of Ejido Endowments

We have recovered detailed data on the surface area of sections of the Hacienda from AGEV records of ejido endowments made after the Mexican Revolution of 1910 (Table 1). These records show that the total surface area of the hacienda at the beginning of the endowment process was 7,706.5025 ha (AGEV exp. 385, f. 104).

Table 1. Areas of Some Ejido Endowments Formed from the Hacienda de Hueyapan.

a The initial dotación of 828 ha was made in 1929; an additional 325 ha were transmitted in 1932.

b Only 237 ha were transmitted to Salto de Agua de los Islaba in 1935; the remaining 458 ha were transmitted in 1999.

Archival records also show that ejidos were formed from Hacienda de Hueyapan lands in Tlapacoyan de Abajo and Tlapacoyan de Arriba (AGEV exp. 762, f. 173), to the south and east of Tres Zapotes; we have not found explicit statements about the surface area included in these endowments, but Pool confirmed their boundaries in the course of his recent (2014–2017) archaeological survey.

The adjacent ejidos of San Juan de los Reyes (now Luis Valenzuela) and Los Lirios were formed in 1917 from national lands to the north of the Hacienda de Hueyapan (AGEV exp. 83). Other adjacent ejidos came from privately held lands (predios), some of them also extensive. They provide limits to the holdings of the hacienda. Population centers of several of these bordering zones are marked on the map.

Testimony from Descendants and Former Residents

We also conducted interviews of many of the descendants and other relatives of Pedro Mimendi Camacho, in which we asked for information about the hacienda. The fullest data on the extent of the hacienda lands come from Manuel Ramírez, who described Mimendi variously as his uncle and as his patrón, and Leonardo Rascón Cano, who described the son, Pedro Mimendi López, as his maestro for having taught him to play the harmonica. Manuel Ramírez died in 2015 at a reported age of 104. Leonardo Rascón was 93 years, 4 months old when interviewed on August 1, 2015. He passed away two years later, in August 2017 (Rogelio A. Rascón Azamar, personal communication 2018).

Ramírez identified a house in the hamlet of Hueyapan de Mimendi (named for its association with the hacienda) as the hacienda's casco, or administrative center (Figure 6). He stated that Mimendi had given him the house, which he lived in for many years. The identity of this house and its location appear to be well known in Tres Zapotes; it is known at least to the Ramírez family and their associates, to some of the Tres Zapotes site museum's staff, and to some relatives of Pedro Mimendi Camacho who now live in the city of Veracruz. As the crow flies, the casco is located about 3.8 km from the colossal head; following along the courses of the two main arroyos, and cutting across where they near one another, the distance would be about 4.5 km—consistent with the estimated distance of one league (4.2 km) in El Siglo XIX's detailed report of the discovery of the colossal head (Rodríguez Prampolini Reference Rodríguez Prampolini1997:162–163).

Figure 6. Photograph of the remaining structure of the casco of the Hacienda de Hueyapan de Mimendi. (Photograph by Christopher A. Pool.) (Color online)

Some family members living in the city of Veracruz state that the casco was burned at the time of the revolution. However, some also stated that they had visited at the house as children. One granddaughter, who volunteered that the hacienda house had been burned, stated that her last visit when the house was still intact took place when she was six years old, which would have been in 1923–1924. It is unclear whether the house had ever completely burned down. A neighbor of Manuel Ramírez told us there had been three structures and that only the one where tortillas were made burned. This fire may have been fairly recent, since a 1982 topographic map (INEGI 1982) indicates three structures in this location.

In 2011, Justeson and Pool visited the occupant of one of the structures, Pío Ramírez, with whom Pool has long been acquainted and who is the son of Manuel Ramírez. Ramírez confirmed his father's account of its history. He stated that the structure was about 200 years old and pointed out some areas where it had been remodeled; for example, its thatched roof has been replaced by a tin roof. A few of the rafters show signs of having been partly burned; we do not know whether this is connected with the accounts of the house having burned down.

Pedro Mimendi evidently did not live in this structure in its heyday; he was a resident of Tlacotalpan, from which his correspondence to the Museo Nacional originated. From its size, the structure seems unlikely to have been the primary home of the hacienda's owners. This suggests to us that it was occupied by the hacienda's administrator or that it is a repurposed building on the grounds of the casco. The 1870 account of the discovery in Fomento de los Tuxtlas (quoted December 14, 1870, in Siglo XIX, republished in Rodríguez Prampolini Reference Rodríguez Prampolini1997:162–163) is not explicit on the point but seems to associate the 1856 administrator Manuel María Artigas, who was responsible for overseeing the investigation of the colossal head on its discovery, with the casco. Melgar y Serrano (Reference Melgar y Serrano1869:292) refers to Artigas—without naming him, but as the person who oversaw the investigation of the head—first as the amo and later as the dueño of the hacienda. Starting around 1870, Mimendi effectively served as the hacienda's chief administrator.

Manuel Ramírez provided data on the extent of the hacienda lands figured from Tres Zapotes: La Boca (de San Miguel), due west on the Rio San Agustín; Paso del Amate to the south; midway to San Juan de los Reyes to the north; Los Lirios to the northeast; Tlapacoya(n) and “medio cerro” to the east. These limits were corroborated by Leonardo Rascón, who stated that the Río San Agustín formed the western boundary of the ejido, extending southward as far as the lands of Palo Herrado, which lies nearly due west of Paso del Amate. Rascón further described the northern boundary as running eastward from the Río San Agustín past San Pablo and Los Lirios.

Archival records show that San Juan de los Reyes and Los Lirios were outside the limits of the Hacienda de Hueyapan and that their ejidos were endowed from “tierras nacionales” that abutted the hacienda to the north, whereas the ejidos in Tlapacoyan de Abajo and Tlapacoyan de Arriba were endowed from Hacienda de Hueyapan lands. Thus, it appears that Ramírez was giving us accurate information about the major centers near but not always within the limits of the hacienda lands. He did not mention the southeastern limits of the hacienda, for which, however, we have fairly precise data.

During the archaeological survey in the area in 2014, while discussing ejido boundaries, Pool learned that “medio cerro” is a common general reference to midway up Cerro el Vigía. Archival records indicate that part of the proposed endowment to Salto de Agua de Pío was from uncultivable pedregal along the flanks of Cerro el Vigía. In the vicinity of Tlapacoyan de Arriba, closest to el Vigía, elevations are mostly below 50 m and are cultivable. The mountain has a fairly well-defined skirt that rises fairly evenly to about 300 m, after which it begins to rise much more sharply to its peak at about 860 m (Geissert Reference Geissert K., Guevara S., Laborde D. and Sánchez-Ríos2004:Cuadro 1). A substantial part of the 584 ha of the Salto de Agua endowment was located on this skirt (AGEV exp. 1365, f. 179–182).

Overall, the hacienda occupied a west–east swath from near Río San Agustín to the southern escarpment of Cerro el Vigía and extending northward near the center of the hacienda from south of the town of Tres Zapotes to the southern borders of the San Juan de los Reyes and Los Lirios ejidos.

Hacienda Limits before the Revolution

Maps of the dotaciones of lands for the ejidos of San Juan de los Reyes (now Luis Valenzuela, AGEV exp. 83) and Medellín (AGEV exp. 1436, two maps) delimit the northern, eastern, and southeastern boundaries of the Hacienda de Hueyapan, as well as parcels that were purchased or ceded from it (Figure 7). A map drawn in 1915 of “los terrenos denominados San Juan de los Reyes [now Luis Valenzuela] y Los Lirios” clearly indicates that the northern boundary of the hacienda “Hueyapam” then extended eastward 14 km from the community of “Suchiapam” (Suchiapa) and passed 2 km south of San Juan de los Reyes (directions were plotted to magnetic north on the original maps). This line corresponds closely to modern property lines and to the partial northern hacienda boundary on the larger of the two Medellín maps. The larger map clarifies that the northeast corner of the hacienda lies at the eastern terminus of the line on the San Juan map, where the boundary of the San Juan dotación turns northward along what are marked as ejido lands of Santiago Tuxtla. From this point, the Medellín maps show the eastern boundary running southward to the northeast corner of a property owned by Fernando Díaz, where the hacienda boundary turns eastward, about 500 m north of the community of El Potrero; the predio (plot of agricultural land) El Potrero, belonging to Guillermo Reyes Palacio, borders the hacienda on the south. These eastern boundaries enclose lands designated for Salto de Agua de los Islabas, Salto de Agua de Pio, and two discontinuous parcels for Medellín, as well as the congregación of Tlapacoya. Again, the boundaries shown on the Medellín maps correspond closely to modern property lines. For additional details concerning our reconstruction of the hacienda's limits before the Mexican Revolution, see Appendix B.

Figure 7. Map showing archivally documented boundaries of ejido endowments, modern ejido boundaries documented on survey, and inferred boundaries of the Hacienda de Hueyapan.

Results

Figures 5 and 7 present our approximation to the hacienda's land holdings that best conforms to all the data and inferences. Boundaries on the north, east, and eastern half of the southern limit of the hacienda are based on the San Juan de los Reyes and Medellín maps (AGEV exp. 83, AGEV exp. 1436) and are most secure. The southern boundary is extended to the west, following contemporary field boundaries. The western boundary is estimated based on the requirement that the hacienda covered 7,706.5025 ha, but it may have been more irregular than shown if it extended along the Arroyo Hueyapan to Boca de San Miguel, as indicated by Manuel Ramírez and Leonardo Rascón. To the extent possible, we have also followed ejido and private field boundaries in satellite imagery from INEGI maps and ESRI World Imagery, corroborated in the course of Pool's regional archaeological survey, and natural boundaries, especially river courses. Overall, the hacienda was concentrated along an east–west swath from near the Río San Agustín to the western slopes of the Cerro el Vigía, also extending northward from the town of Tres Zapotes to the southern boundary of the San Juan de los Reyes lands and northwestward at least as far as the community of Suchiapan. Within it, the colossal head lay near the western edge of the Tres Zapotes archaeological site in Group 1, a civic-ceremonial complex, about halfway between the southern and northern limits of the site as defined by Pool (Reference Pool and Pool2003:91, Fig. 7.1), based on surface and subsurface artifact densities and mounded architecture (Pool and Ohnersorgen Reference Pool, Ohnersorgen and Pool2003; Wendt Reference Wendt and Pool2003). Concentric polygons in Figure 8 mark proportional distances from the colossal head to the approximated limits of the hacienda, at proportions of one-fourth and one-ninth (distance data are reported in Table 2).

Figure 8. Map showing concentric polygons at ¼ and ⅑ the distance from the Cabeza Colosal to the inferred boundaries of the Hacienda de Hueyapan.

Table 2. Estimated Bounds for Proximity of the Find-Spot of the Tuxtla Statuette to the Colossal Head (Tres Zapotes Monument A) and the Tres Zapotes Archaeological Site.

Notes: Based on contours of ¼ and ⅑ of the distance from the monument to the limits of the Hacienda de Hueyapan. These are maximum distances, measured to the corners of the hacienda, not the nearest point.

We conclude that the Tuxtla Statuette almost certainly came from within 2 km (about 1.2 miles) of the site of Tres Zapotes. Using the least biased criterion of one-ninth of the way from the colossal head to the nearest hacienda boundary to mark the limits of being “very close” to the colossal head, only about 21% of the region from which the statuette may have come lies outside the archaeologically defined limits of the site. In these terms, the statuette was probably found at the political center of Tres Zapotes and, in any case, in its immediate vicinity; it is certainly from the political unit dominated by Tres Zapotes.

This is consistent with the archaeology of the site, as reported by Pool (Reference Pool, Arnold and Pool2008; Pool and Ohnersorgen Reference Pool, Ohnersorgen and Pool2003) and Ortiz (Reference Ortiz Ceballos1975). Tres Zapotes was occupied continuously from 1250 BC to AD 900, but was at its apogee during the epi-Olmec era, in particular in the Late Formative (ca. 400–1 BC), when the epi-Olmec text of Stela C was inscribed, and during the Protoclassic period (AD 1–300) to which the statuette belongs. The Protoclassic was a time of much activity in the site's civic-ceremonial complexes and of significant change in the political organization of the Tres Zapotes polity (Pool Reference Pool, Arnold and Pool2008, Reference Pool, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010; Pool and Loughlin Reference Pool, Loughlin and Faulseit2016). Construction in Stirling's (Reference Stirling1943) Mound Group 3 at the northeastern end of the site created a new plaza oriented north–south, at right angles to the group's original plaza (Pool Reference Pool, Arnold and Pool2008). The middle fragment of Stela C was reset at the north end of the new plaza, at the foot of its principal mound, after having been broken into three pieces sometime earlier. Ten meters to the south, another stone slab was set as a plain stela in association with a lip-to-lip ceramic vessel offering containing wood charcoal dated to 1870 ± 50 BP (Beta 115434, 2σ cal. AD 55–250, intercept = cal AD 135) (Pool and Ohnersorgen Reference Pool, Ohnersorgen and Pool2003:23), a range that includes the date of the Tuxtla Statuette. In Mound Group 1, where the colossal head was located, ceramic distributions suggest an alteration of the functional relationships among structures, moving the seat of elite residence and administration from the north to the west end of the group (Pool Reference Pool, Arnold and Pool2008:136, 141).

The Protoclassic alterations in Groups 1 and 3 disrupted the Late Formative spatial order that Pool (Reference Pool, Arnold and Pool2008) designates as the Tres Zapotes Plaza Group (TZPG) layout, which consists of an elongated elite residential/administrative mound on the north side, a conical temple mound on the west end, and a low adoratorio on the long axis of the plaza. Pool (Reference Pool, Arnold and Pool2008:145–146) interpreted the replication of the TZPG layout in the four civic-ceremonial complexes within Tres Zapotes and the nondominance of any one of these TZPGs as an expression of shared governance among political factions, and their Protoclassic alteration as a reassertion of suppressed exclusionary strategies and competition among factional leaders. Similarly, local elites in the hinterland of the Tres Zapotes polity increasingly experimented with new architectural layouts and expressed individual authority in monumental sculpture, as at El Mesón (Loughlin Reference Loughlin2011; Pool and Loughlin Reference Pool, Loughlin and Faulseit2016). Within this dynamic political milieu, the recording of historical events and rituals using the epi-Olmec script bolstered narratives of authority. Our demonstration that the Tuxtla Statuette was found at or very near Tres Zapotes corrects Pool's (Reference Pool, Arnold and Pool2008:150) suggestion that the still-powerful Tres Zapotes had abandoned writing to become an island in the literate world of the Protoclassic. That world included the site of La Mojarra, 40 km west of Tres Zapotes, in the Papaloapan delta, with its long epi-Olmec inscription commemorating events, the last of which occurred only four years earlier the AD 162 date of the statuette. At that time, Tres Zapotes was the dominant center in a region that extended from the Papaloapan delta through the western Tuxtla Mountains. Rather than eschewing the writing and calendrical system their predecessors used two centuries earlier on Stela C, it appears that the elites of Tres Zapotes continued to employ them to proclaim their authority.

Epilogue

It is with regret that we note that this article should never have been necessary. Félix Cházaro Guzmán, the owner of the Tuxtla Statuette, continued to live in Tlacotalpan until his passing in 1964; for 57 years, the man who surveyed the lands on which his statuette was found saw it hailed as one of the most important artifacts from ancient Mexico. In their 1938 and 1939 expeditions, Stirling's group disembarked at Tlacotalpan and spent the afternoon and evening there before continuing to Hueyapan and Tres Zapotes; they almost certainly passed within eyeshot of Cházaro's home, located on the first street after the boat landing, right off the Parque Hidalgo.

Stirling was mindful of the statuette, which he discussed in his initial report on the Tres Zapotes work and described as “probably the most famous archaeological object found in the New World” (Reference Stirling1939:183); he noted that it was made very near Tres Zapotes, assigning it to the Tuxtlas on the basis of Holmes's designation. Had Holmes published the details of its origin that Félix Cházaro of Tlacotalpan had provided him, Stirling and Cházaro should have met, and Cházaro could have given him more detail about where the statuette was found—perhaps the very spot.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the memory of Félix Cházaro Guzmán of Tlacotalpan: surveyor, agricultural specialist, and owner (1902) of the Tuxtla Statuette.

Our research was made possible in large measure by the cooperation of the grandchildren and other relatives of Félix Cházaro Guzmán and Pedro Mimendi Camacho, who shared a detailed knowledge of their families' histories; we are particularly grateful to Concepción Díaz Cházaro, Guadalupe Mimendi Porragas, and Francisco Galí Malpica. We received useful information from residents of Tlacotalpan, Tres Zapotes, and Hueyapan de Mimendi, especially Manuel Ramírez, Pío Ramírez, Leonardo Rascón, and Alberto Sánchez. The directors and staffs of the Archivo Histórico del Museo Nacional de Antropología and the Archivo General del Estado de Veracruz (AGEV) went out of their way to help us: we thank in particular, at the AHMNA, Diana Magaloni and coordinador de acervos José Guadalupe Martínez, and at the AGEV, director Olivia Dominguez Pérez and her assistants. Archaeological fieldwork at Tres Zapotes was conducted with permission of the Instituto Nacional de Arqueología e Historia (Oficio 401.B(4)19.2014/919). No other permits were required.

We owe a particular debt to Felisa Cházaro Mimendi. A 2010 newspaper article about her 100th birthday brought her to our attention as a possible descendant of Pedro Mimendi and of the F. Cházaro who wrote the letter to Ulbricht. It was Justeson's hunch that she might have been named for a father F. Cházaro that led us to unravel the genealogical history that our interviews since confirmed and elaborated. We initiated our interviewing in Veracruz in the hope that she might have been an ear-witness to history—that after the Revolution of 1910, the year of her birth, she might have heard her family talk about the wonderful things that had been found on the plantation, and perhaps, in general terms, where they came from. It was a chance to open a window on the archaeology of more than a century ago that we could not let pass. Because of the family's concerns for her serenity, we were not able to interview her personally, but they found out for us that she knew nothing of such matters; another of Pedro Mimendi's granddaughters, Guadalupe Mimendi, told us that as children they would never hear such talk because they were not privy to adult conversations at family gatherings.

This research was initiated by Justeson and Walsh during Justeson's postdoctoral fellowship at Dumbarton Oaks in fall 2010; the Smithsonian's archives and Dumbarton Oaks's library resources led them to our initial hypotheses about the find-spot of the statuette and the individuals involved. They thank Dumbarton Oaks and the Smithsonian for their support; at Dumbarton Oaks, Justeson thanks Joanne Pillsbury, then director of Pre-Columbian Studies, and the late Bridget Gazzo, Pre-Columbian Librarian, for their consistent helpfulness.

This article benefited significantly from the substantive comments and suggestions of four anonymous reviewers.

The order of authors is simply alphabetical, as all the coauthors made crucial contributions to this article's findings; Justeson and Pool share primary responsibility for writing it.

Data Availability Statement

The documents used in this article are available for inspection at the National Anthropological Archives of the Smithsonian Institution; the Archivo General del Estado de Veracruz, Xalapa, Veracruz; and the Archivo Histórico del Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City. The Tuxtla Statuette is in the collections of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

Appendix A Smithsonian Correspondence Regarding the Statuette

1. Letter from Félix Cházaro Guzmán to Robert E. Ulbricht

Translated version of a letter from F. Cházaro to William Henry Holmes, director of the Smithsonian Institution. The original Spanish version was in the possession of Robert E. Ulbricht and was said to be available if desired, but it does not seem to have been sent to the Smithsonian.

“Tlacotálpam Aug 8.1904

Mr. R. E. Ulbricht

30 Broad Street New York

Dear Mr Ulbricht

Your letter of May 27th was only received a few days ago. I suppose it was addressed to Orizaba; somebody must have opened it there because it brought an envelope marked with a postal mark from that town. Whenever you write to me in future, address your letters to Tlacotálpam, V.C. ― I left the V.C Al P. last January.

Regarding the stone will say: that the stone is genuine, no matter who says the contrary. Either the gentleman that says the stone is not genuine knows nothing about these kind of idols or he is too malicious. For your certainty about the stone will say: that it was found by an indian while plowing a corn field in Hacienda de Hueyapam, Canton de Tuxtla, state of Vera Cruz. This hacienda belongs to my father in law, and no where around this place will you find any stone of that quality. Very close to where this idol was found there is a very large one called ‘La Cabeza Colozal de Hueyapam,’ which has been offered by my father in law to the Mexican Government for the Museum. This is not the only specimen found in this property but many others are found, specially when an excavation is made in one of the many small mounds that the property has. Everything I say is the truth and very easy to prove, and I hope you will believe. Be always sure that you have some thing genuine.

Hoping that you are well, I am

Yours’ sincerely,

F. Cházaro”

2. Cover letter from Ulbricht, forwarding Cházaro's letter to Holmes

A letter from Ulbricht dated Sept 20, 1904, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which was apparently sent with the copy of Chazaro's letter, explains the delay in responding—that he was in Havana on business. It further states:

“I hand you herewith copy of my friend's letter, and if you should wish to have the original, I am willing to send it to you. From Mr. Cházaro's letter you will gather that he is very indignant to have a reflection cast on the genuineness of the idol. If I can be of any further service in the matter please command. Yours truly, R. E. Ulbricht”

3. Excerpt of reply by Ulbricht to Holmes, concerning the suggestion that the statuette might not be genuine

Dated May 22, 1904.

“I am really very much astonished to hear that some doubt as to the genuineness of the little Mexican idol, should have been expressed. The party from whom I got it, is thoroughly reliable; at the time I transmitted it to you I gave you all the facts he had given me viz: where and under what circumstances it had been found; and right here I would like to add, that, as ‘Serpentina’ or Jade is not found in Mexico in its raw state, but many small and larger idols, cut out of that stone, are found in Mexico, I doubt whether the party, who has cast a reflection upon the genuineness of this piece could substantiate that it had been manufactured. Anyhow, for your satisfaction and for my own, I will at once write to the gentleman from whom I got it, and when his answer is received, I will send it to you. Mr Alfred Bishop Mason will probably not know anything further about this piece, than I have given you heretofore. The gentleman who owned it, was formerly in Mr. Mason's employ, & at one time he probably requested Mr. M. to have the signs on the stone deciphered at your institution, as the Museum in the City of Mexico was probably not able to do so.

As soon as I receive an answer from Mexico, I will take pleasure to communicate further with you, and in the meantime, I remain Yours sincerely, R. E. Ulbricht”

4. Letters to the Smithsonian from Alfred Bishop Mason

The relevant portions of Mason's letters are quoted in the text.

Appendix B Additional Details on Reconstruction of the Hacienda Limits

Other AGEV documents (exp. 1731, f. 23, 30, 37, 38) support Manuel Ramírez's and Fernando Rascón's descriptions of the southern limit of the hacienda. In 1938 the ejido of Paso del Amate, covering a total of 364 ha, was formed from lands pertaining to the Hacienda de Hueyapan (153 ha) and from parcels owned by Alonso Lázaro (95 ha) and José Buil (23 ha). As of April 18, 1938, the predios identified as possibly affected by the creation of the ejido were the Hacienda de Hueyapan (by then owned by the Banco Nacional de Crédito Agrícola), with more than 5,000 ha remaining; Alonso Lázaro, with 1,358 ha; Palo Herrado (then owned by José Buil of Loma de Chuniapan), and the “sucesión de Pascual Rosario,” the extent of which is not given.

It is difficult to reconcile the areas of the parcels that formed the Paso del Amate ejido with distances from that community to the community of Palo Herrado to the west, the casco of the Hacienda de Hueyapan to the north, and the southeastern boundary of the Hacienda de Hueyapan indicated on maps of the Medellín ejido. We infer that the ejido lands of Paso del Amate, like those of Medellín, were discontinuous.

Nevertheless, these documents clearly distinguish between the lands of José Buil and those of the hacienda. Because Palo Herrado is well south of the extension of the southern boundary of the Hacienda de Hueyapan marked on the Medellín map, it is unlikely that the predio of Palo Herrado was ever included in the 7,706.5025 ha of the hacienda. Furthermore, the descriptions of these dotaciones verify Manuel Ramírez's statement that the hacienda extended as far as Paso del Amate (evidently the ejido, not the community itself) and Leonardo Rascón's statement that they extended southwest as far as the lands of Palo Herrado.

Apparently, much hacienda land was sold to private parties before many of the ejidal distributions. For example, in 1948, Celso Vázquez Ramírez purchased pastureland originally estimated at 1,204.5025 ha but later measured at 1796.6 ha of the “exhacienda Hueyapan de Mimendi” from the Banco Nacional de Crédito Agrícola y Ganadero (DOF 5 Jun 2001). In 1958 Vázquez sold 796.6 ha to eight individuals in lots of 99.575 ha and 100 ha to the Comisión del Papaloapan, which were later acquired by the Compañia Industrial Azucarera San Pedro. Ultimately, lands that had been part of the original Vázquez purchase were ceded to the ejidos of Hueyapan de Mimendi (396 ha), La Providencia (396 ha), and Salto de Agua de los Islaba (458 ha, completing the 695 ha that had been promised in 1935, see Table 1; DOF 5 Jun 2001). The community of Hueyapan de Mimendi is the location of the hacienda's casco. The ejido of Salto de Agua de los Islabas II is immediately adjacent to Hueyapan de Mimendi on the east, despite being more than 11 km from the parent community. The community of La Providencia lies about a kilometer north of the northern limit of the Hacienda de Hueyapan, as indicated on a 1918 copy of the 1915 San Juan de los Reyes map (AGEV exp. 83).