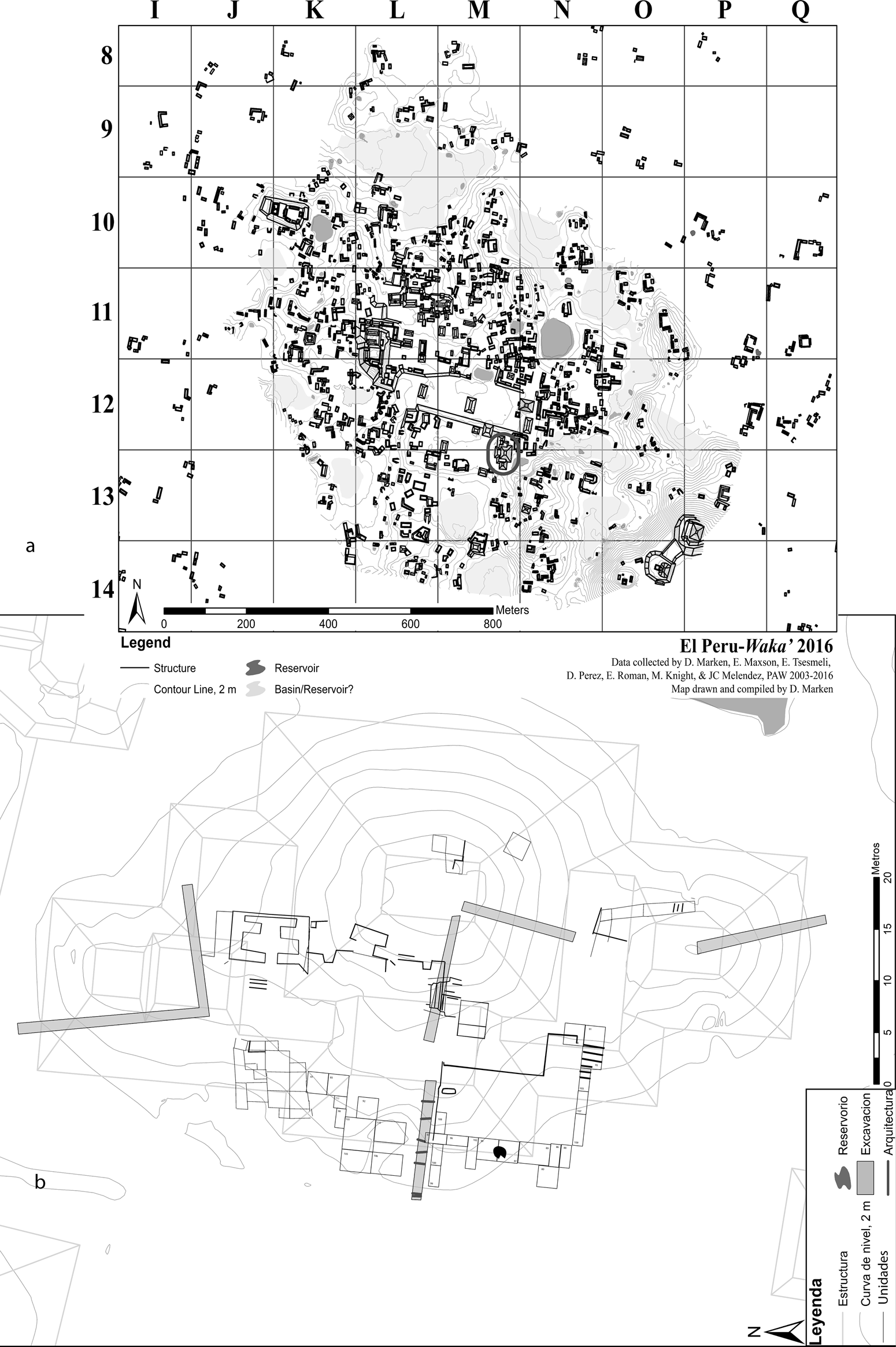

Research on the civic-ceremonial structure dubbed M13-1 in the Classic Maya city of El Perú-Waka’, Petén, Guatemala (hence Waka’; Figure 1), centers on its complex ritual significance. Following indications that non-elite Waka’ citizenry crystallized their memories there during the Terminal Classic (Navarro-Farr Reference Navarro-Farr2009), we probed earlier phases to contextualize these late-term behaviors. We focus here on the discovery of Burial 61, a royal tomb built into a buried subphase. Evidence permits identification of the interred as Lady K'abel, the Late Classic queen of Waka’ who was a kaan princess, also known from El Perú Stela 34 (Figure 2).Footnote 1 We believe these data and their implications contribute to discussions about the intersection of gender and ancient Maya statecraft.

Figure 1. (a) Waka’ map (Structure M13-1 circled) and (b) Structure M13-1 plan map (maps created by Damien Marken).

Figure 2. Front Face of a Stela (Free-standing Stone with Relief), 692. Mesoamerica, Guatemala, Department of the Petén, El Perú (also known as Waka’), Maya people (AD 250–900). Limestone; 274.4 × 182.3 cm. Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1967.29. (Color online)

Waka’ is located in northwestern Petén, Guatemala, overlooking the confluence of the San Juan and San Pedro Mártir Rivers (Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly, Rich and Robles2020:Figure 1). Lidar data indicate that the urban core of Waka’ is approximately 1.34 km2, making it one of the most densely nucleated cities in northwestern Petén (Marken and Pérez Reference Marken, Pérez, Pérez, Pérez and Freidel2018). Its occupation spans the Preclassic, around 300 BC, through the Terminal Classic, around AD 1000 (Eppich Reference Eppich2011). Archaeological investigations have focused on the breadth and nature of the occupational and political history of Waka’ (Navarro-Farr and Rich Reference Navarro-Farr and Rich2014). This report presents evidence contextualizing this history within the broader Classic Maya geopolitical sphere.

Context

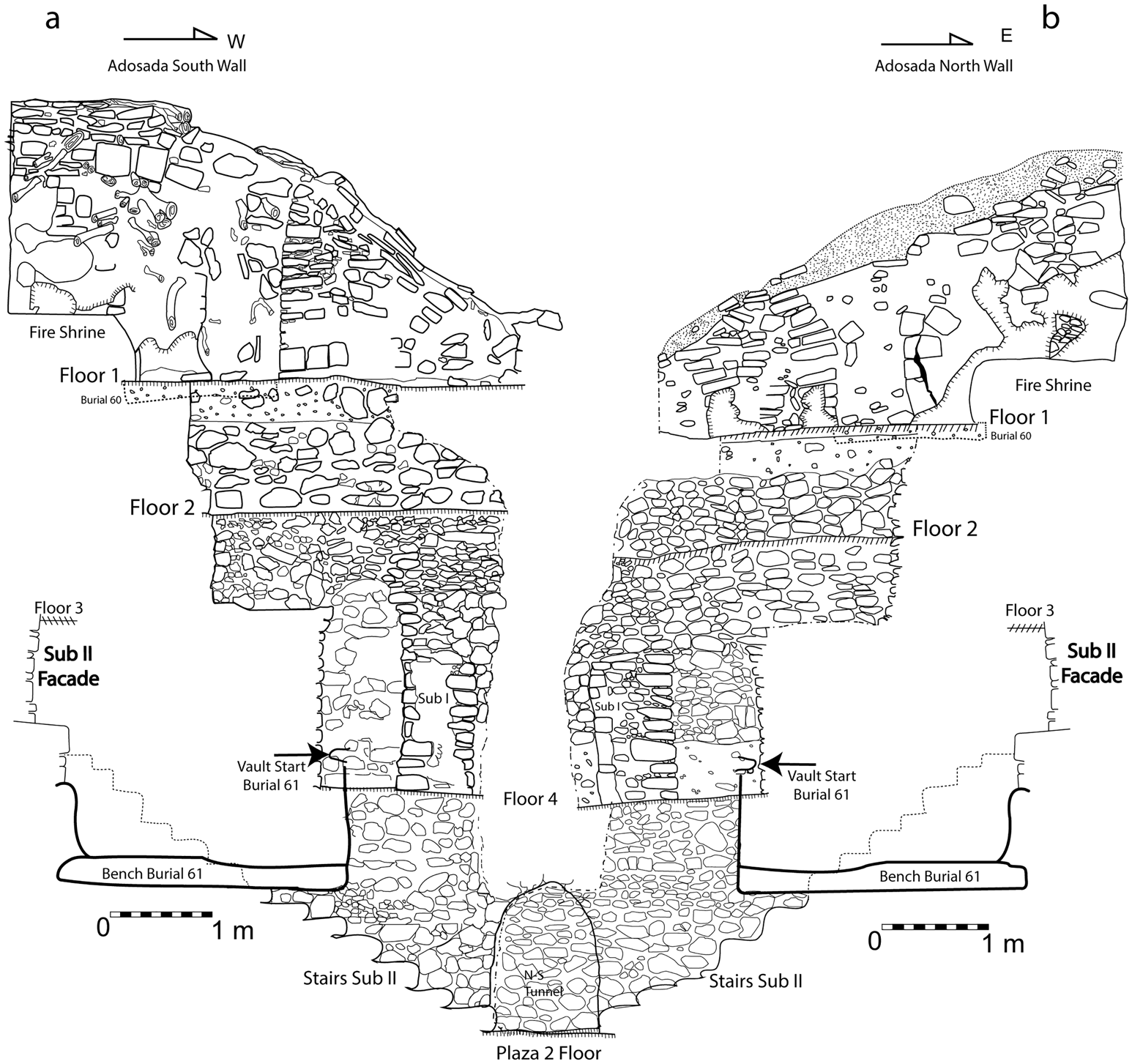

The tomb's construction considerably changed the building's fronting platform (adosada). The tomb chamber was built into the Substructure II (Sub II) staircase (Figure 3a–b). Type-variety analyses of ceramics from sealed contexts and the adosada construction stratigraphy indicate that Sub II dates to the Late Classic (ca. 650–800 AD; see also Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Robles, Bolaños and Calderón2013). The funerary chamber is situated just north of Sub II's centerline and west of the façade. The upper and lateral sides of the Sub II façade were shorn and capped with a floor as part of the chamber construction. That floor, which subsequently collapsed atop the chamber's vault, had no discernible cut. The remodeling that followed the tomb construction resulted in the movement of the centerline axis farther north. It also involved the resetting of the carved Stela 44 (Pérez Robles and Navarro-Farr Reference Pérez Robles, Navarro-Farr and Calderón2013) along that new centerline, where it was subsequently covered by the construction of the building's Substructure I phase.

Figure 3. (a) South and (b) north profiles of Structure M13-1 adosada (illustration by Juan Carlos Pérez Calderon, Griselda Pérez Robles, and Olivia Navarro-Farr).

Although to date there is no direct evidence of tomb reentry, a documented practice at Waka’ (Lee Reference Lee, Escobedo and Freidel2005; Rich Reference Rich2011), there are indications that it might have occurred. We encountered irregularly positioned flat stones under the collapsed floor debris that capped the remains. This same pattern was recorded in association with reentering Waka’ Burial 39 (Rich Reference Rich2011). Heavy burning was also documented above and southeast of the chamber. Additionally, obsidian clusters appear near the chamber's eastern and western ends. Concentrations of knapped obsidian in association with tomb reentry are common in the Maya area (see, among others, Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1996; Hruby and Rich Reference Hruby, Rich, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014; Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy1997; Trik Reference Trik1963). The eastern obsidian clusters appeared above and intermixed with the collapse atop the chamber. The stratigraphic position of these obsidian blades and their proximity to the burnt stone suggest they could have been part of a leave-taking ceremony following reentry, a pattern noted elsewhere at Waka’ (Hruby and Rich Reference Hruby, Rich, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014). The flaked obsidian clusters at the western end appeared both below the collapsed vault stones and the flattish stone layer. Indeed, the abundance of obsidian blade fragments we observed throughout, totaling ~4,644 pieces, is noteworthy. The intact western chamber wall suggests that the eastern sector is the better candidate for a reentry point. Further exploration of Sub II's northeastern façade should help determine whether tomb reentry occurred there.

Excavations revealed that the chamber's construction and the interment were carried out rapidly, based on the adhesion of certain vessels to the funerary bench and weave impressions left on mortar. These impressions included a fragment of mortar retaining a mat impression and impressions of folded cloth visible along the southern surface of the funerary bench. The woven mat, folded cloth, and red-stained lower limbs of the interred suggest the individual was wrapped in textiles, placed atop a mat, and covered in red paint. Importantly, these funerary treatments have been associated with interments of high-ranking individuals (Reese-Taylor et al. Reference Reese-Taylor, Zender, Geller, Guernsey and Kent Reilly2006).

Osteology

A single individual was interred in the Burial 61 tomb in a supine, extended position with the head oriented east. The skeleton (Figure 4a–b) was nearly complete though fragmentary and poorly preserved, which hampered assessment. The skull and femora, elements often removed during tomb reentry, are present. However, their presence does not preclude disturbance in antiquity, as seen in the reentered Waka’ Burial 39 tomb (Rich Reference Rich2011).

Figure 4. (a) Burial 61 and (b) Burial 61 close-up (illustration by Olivia Navarro-Farr; photogrammetry by Francisco Castañeda).

Laboratory analysis revealed the tomb's occupant was a middle-aged to old adult at the time of death. Age and sex were evaluated according to standards outlined by Buikstra and Ubelaker (Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994). The age estimate is based on extensive dental wear, fusion of cranial sutures, and arthritic changes on various bones. Unfortunately, the pelvis, which includes the most diagnostic features for sexing skeletal remains, was too poorly preserved for evaluation. Several cranial features, including the nuchal crest, the glabella, and the supraorbital margin, were evaluated, which gave conflicting indicators of sex. Muscle attachment points, including the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus and the linea aspera of the femur, are relatively pronounced. Importantly, although robust attachment sites are often seen in males, these traits can emerge as a result of high activity levels. Thus, an active female could also have a robust skeleton. Ultimately, the ambiguity of these skeletal features means that sex remains undetermined for this individual.

Due to the fragmentary nature of the skull, cranial modification could not be assessed. All the teeth except three were recovered. Eight were modified in the E-1 style, with a single circular stone inlay in the center of the labial/buccal surface (Romero Molina Reference Romero Molina1986). However, the pattern displayed across the dentition is not common. The right maxillary teeth, from the central incisor to the first premolar, have inlays. The left maxillary teeth are unmodified. The pattern is repeated on the mandibular teeth, except only the left teeth are modified, whereas those of the right side are not.

There were no carious lesions on the teeth. Dental calculus, however, was present on many teeth and is most evident on the mandibular molars. Osteoarthritis was observed on a scapula, patella, the femora, and several vertebrae. There was no other discernible pathology, except for one possible area of periosteal reaction on the left fibula. Overall, these data suggest a relatively healthy individual.

Funerary Offerings

Burial 61 is a rich funerary assemblage indicative of a high-status individual. Because exhaustive discussion of all the tomb contents is not possible here, we limit this discussion to elements that provide chronological information and permit identification of the interred (see also Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Robles, Bolaños and Calderón2013).

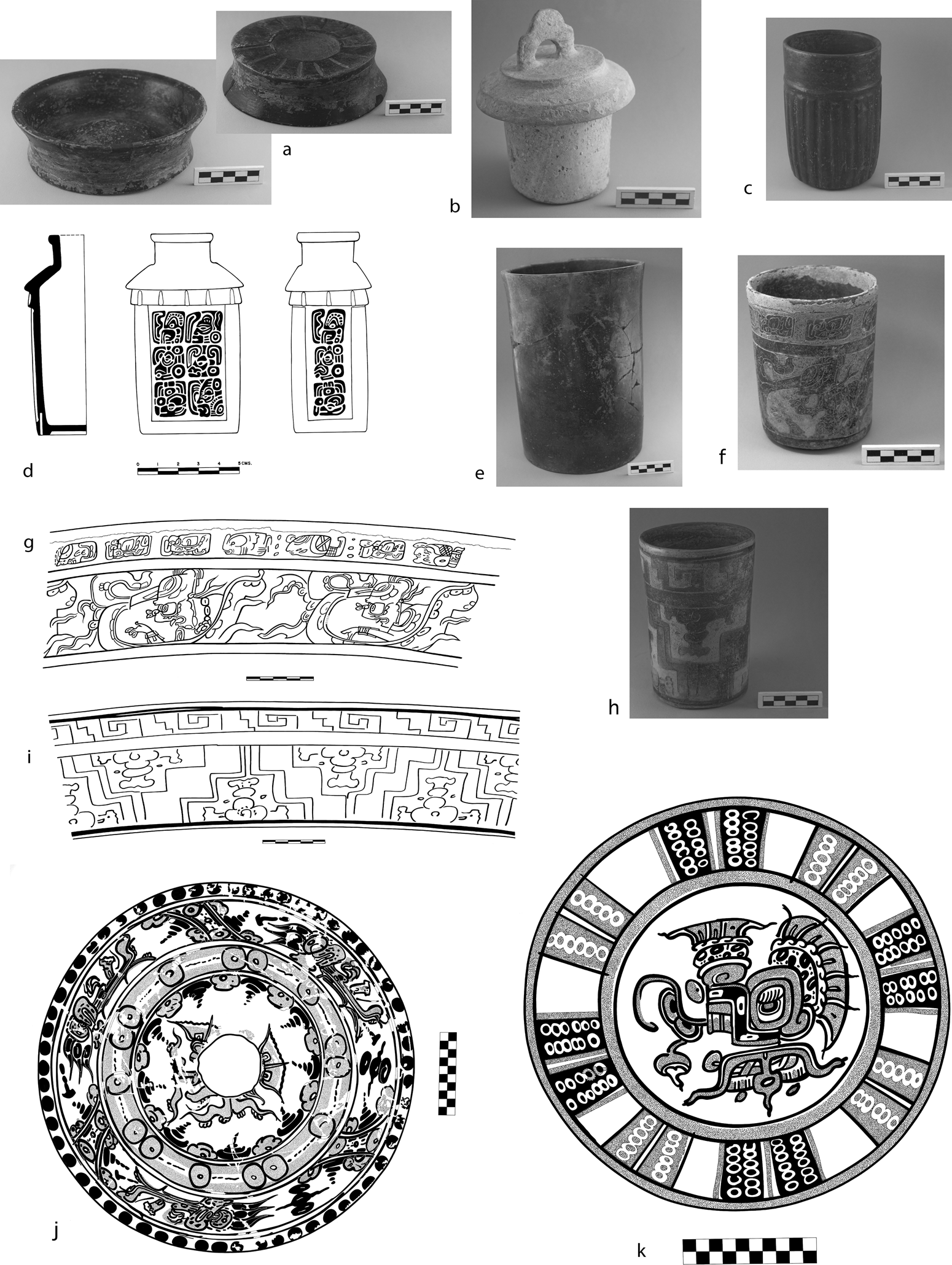

Vessels

Type-variety analysis indicates that the 18-count ceramic assemblage dates to the early/middle eighth century, supporting the identification of the occupant as a Late Classic ruler. Diagnostic vessels include a black-slipped bowl with concave base and outcurving sides (Figure 5a), a stuccoed blue-painted cylinder with trefoil lid (Figure 5b), a Chilar Fluted cylinder (Figure 5c), a small cream-slipped snuff bottle with stamped pseudoglyphs (Figure 5d), a large black-slipped cylinder (Figure 5e), two Kanalkan Composite cylinders (Figures 5f–i), a Late Classic Palmar Orange Polychrome plate (Figure 5j), and a Palmar Orange Polychrome of undefined variety (Figure 5k). Various vessels are foreign to the local potting tradition, especially the snuff bottle, which is identical to those from the Copan region (Card and Zender Reference Card and Zender2016; Eppich and Navarro-Farr Reference Eppich, Navarro-Farr, Loughmiller-Cardinal and Eppich2019); the Late Classic Palmar Orange Polychrome plate likely produced at Calakmul (Dorie Reents-Budet, personal communication 2012); and the Kanalkan cylinders, of a style from the Tikal region (Culbert Reference Culbert1993; Culbert and Kosakowsky Reference Culbert and Kosakowsky2019). Together, these vessels underscore this ruler's extensive geopolitical connections.

Figure 5. (a) Black-slipped bowl, (b) stuccoed and blue-painted cylinder with trefoil lid, (c) Chilar fluted cylinder, (d) stamped cream-slipped snuff bottle, (e) black-slipped cylinder, (f–g) Kanalkan cylinder and corresponding rollout, (h–i) Kanalkan cylinder and corresponding rollout, (j) Late Classic Palmar Orange Polychrome, and (k) Palmar Orange Polychrome undefined variety (photographs by Juan Carlos Pérez Calderon; illustrations by René Ozaeta).

Other Funerary Offerings

Certain items in this assemblage signal the power and importance of the interred for the Waka’ polity, whereas the broader suite of offerings is critical to the identification of the interred as a kaan royal with strong ties to Calakmul, the Late Classic seat of that kingdom. In some instances, items either recall portraits of Lady K'abel (Figure 2) or directly identify her. We review these lines of evidence in this section.

Two small figurines rendered from karstic stone—one zoomorphic (Figure 6a) and the other anthropomorphic (Figure 6b)—and a stuccoed and painted mirror (Figure 6c) underscore the elevated status of the interred while also referencing connections to Waka’. The zoomorphic figurine portrays a small mammal with paws positioned as if holding a ceremonial bar and stylized breath/speech scrolls adorning the mouth. This figurine was placed inside the black-slipped cylinder (Figure 5e) at the chamber's eastern end.

Figure 6. (a) Zoomorphic figurine, (b) anthropomorphic figurine, and (c) reconstructed mirror (photographs [a–b] by Juan Carlos Pérez Calderon; illustration and photograph [c]: René Ozaeta).

The more rustic figurine was situated facedown with the head toward the individual's feet in the pelvis, demonstrating a birthing position. This anthropomorphic figurine depicts an individual standing upright with defined legs and arms, a head with a discernible face, and a protruding belly. Digits are marked by incised lines, and dots indicate eyes and nostrils. Some surfaces retain a light blue-grayish color, and there are no sexual characteristics. The left arm is flush with the body, and the right arm clutches a vertical shaft with a horizontal element at the top poised against the neck. Cinnabar around the mouth and neck suggests a bloodied throat and mouth. Though the composition is rustic and its details are crudely etched, the impression of a creature in the act of self-decapitation and/or vomiting blood suggests this is a rendering of the death god Akan (Grube Reference Grube, Graña-Behrens, Grube, Prager, Sachse, Teufel and Wagner2004; Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1998). Grube (Reference Grube, Graña-Behrens, Grube, Prager, Sachse, Teufel and Wagner2004:Figure 8) discusses numerous examples of Akan in self-decapitation, wherein he wields an axe with one hand, poised to his throat. Akan Yaxaj is a Waka’ patron deity named on El Perú Stelae 16 (Guenter Reference Guenter, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014), 44 (Pérez Robles and Navarro-Farr Reference Pérez Robles, Navarro-Farr and Calderón2013), and 51 (Kelly Reference Kelly, Pérez, Robles and Marken2020). Baron (Reference Baron, Kurnick and Baron2016:127) discusses how Classic period patron deities represented important connections to place for communities. Such deities are often represented in texts and as portable effigies. Baron (Reference Baron, Kurnick and Baron2016:136) argues that rulers negotiated their relationship with communities through interaction with and “ritual responsibility” for both conjuring and caring for these important deities. Guenter (Reference Guenter, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014) notes that Akan Yaxaj is the patron deity referenced on Lintel 3 of Temple IV at Tikal, which was captured after Waka's defeat by Tikal's king, Yik'in Chan K'awiil, in AD 743. These parallelisms in tandem with the placement of this effigy in the birthing position are striking.

The mirror (Figure 6c), an object often identified for its high-status value and divinatory associations (Gallaga M. and Blainey Reference Gallaga M. and Blainey2016), has a thinly stuccoed and painted surface with brilliant red and green/blue hues. The surface retains traces of a painted image revealing a seated figure with right arm extended, who appears atop a centipede, Waka's moniker; thus, it likely references the Waka’ polity. This and the possible Akan effigy connect the interred to Waka’.

Approximately 1,515 pieces of worked jadeite and 280 pieces of worked shell, including earspools, beads, tesserae, discs, and pearls, adorned the interred. Two iconographically salient greenstone adornments include a long tubular bead (Figure 7a–b) representing an animate, deity face (Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:295) and the small anthropomorphic head of a youth (Figure 7c–d). The youthful figure's hair is center parted, with three bands running from above the hairline to the forehead's center. One assemblage of 25 rectangular Spondylus shell plaques (Figure 7e), approximately 50 miniscule stone tesserae, and two hollowed bone hair fasteners were located just off the dais. The Spondylus plaques likely formed a shell-stitched cape resembling one described in Tomb 1 of Structure XV at Calakmul (Vázquez López Reference Vázquez López2017). The small stone tesserae and fasteners may be part of a diadem with a small mosaic mask.

Figure 7. (a–b) Tubular jadeite bead, (c–d) anthropomorphic jadeite bead, (e) Spondylus plaques, (f–g) shell tesserae, various forms, (h) stacked earspools, and (i) mask reconstruction (photographs [a] and [d] by Juan Carlos Pérez Calderon; illustrations [b–c] by René Ozaeta; photographs [e–i] by Elsa Damaris Menéndez Bolaños).

The headdress features numerous tubular jadeite bead clusters (Melgar Tísoc and Andrieu Reference Melgar Tísoc, Andrieu, Pérez and Pérez2016). A small assemblage of tesserae carved from Unionidae, Ampullariidae Pomacea, and Spondylus shells were shaped into miniature long bone, square, rectangular, and other forms (examples in Figure 7f–g). Stacked jadeite earspools (Figure 7h) and a small circular greenstone mosaic mask (reconstructed in Figure 7i) were also part of this assemblage. Such masks are common in kaan royal tombs (Carrasco Vargas Reference Carrasco Vargas2000). Experimental studies (Melgar Tísoc and Andrieu Reference Melgar Tísoc, Andrieu, Pérez and Pérez2016) reveal that Burial 61 jadeite was worked with chert, in a manner similar to manufacturing techniques reported at Calakmul. This suggests Burial 61 jades were manufactured at Calakmul, supporting identification of the interred as a kaan royal. In addition, the numerous stuccoed and blue-painted vessels in this tomb (e.g., Figure 5b) are typical of kaan-style funerary offerings (Boucher and Quiñones Reference Boucher and Quiñones2007).

Two bivalve halves, typical of female regalia (Josserand Reference Josserand and Ardren2002), were also included, one placed atop the right hip mimics the Stela 34 xook shell regalia typical of depictions of kaan royal women (Vázquez López Reference Vázquez López2017:25). A figurine included in the assemblage associated with Waka’ Burial 39 (Rich Reference Rich2011) depicting Lady K'abel (Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly, Rich and Robles2020:Figure 4a) includes a mask in her headdress strikingly similar to the circular greenstone tesserae mask (Figure 7i). This figurine and the image on Stela 34 both feature Lady K'abel holding a shield in her left hand. The Late Classic Palmar Orange Polychrome (Figure 5j) was placed facedown over the occupant's left arm, mimicking a shield and directly paralleling the figurine and the stela portrait.

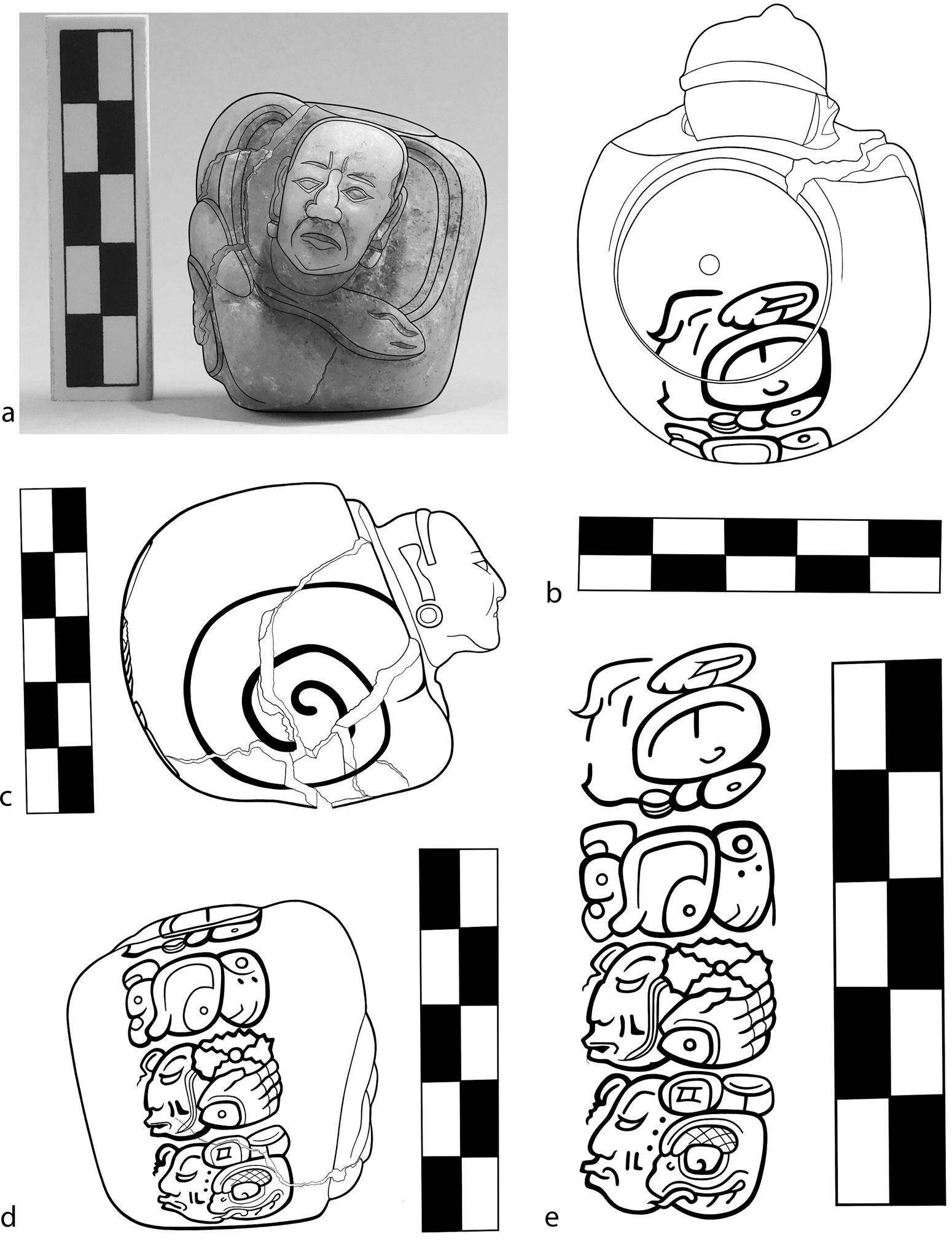

The most compelling object, in terms of identifying the occupant, is a small, lidded alabaster effigy jar with inscriptions bearing her name (Figure 8a–d). The jar, carved as a nautilus shell, features an aged human head emerging from the shell. The right hand/paint brush, a deliberate visual ambiguity, appears beneath the face. The figure's hair is arranged similarly to that of the greenstone head. We posit that the greenstone (Figure 7c–d) and alabaster (Figure 8a) figures depict youthful and aged aspects of the moon deity whose frequent movements are associated with prognostication (Milbrath Reference Milbrath1999). We believe the interred sought association with this deity.

Figure 8. Alabaster effigy vessel: (a) front, (b) top, (c) side, (d) rear, and (e) text (photographs and illustrations by René Ozaeta).

The alabaster jar features four glyphs (Figure 8e). The first is yotoot, “the house of,” indicating the vessel contained the material referenced in the second glyph that, unfortunately, remains undeciphered. David Stuart (personal communication 2019) thinks this is a glyph for face paint. The third and fourth hieroglyphs name the owner as Lady K'abel with her title, ix kaan ajaw, “Lady Snake Lord.” On El Perú Stela 34 (Figure 2) she is given the prestigious title ix kaloomte’, indicating extremely high status (Wanyerka Reference Wanyerka1996). Following Freidel and colleagues (Reference Freidel, Schele and Parker1993), the use of alabaster, the iconography, and the fracture (which we interpret as deliberate) permit its identification as the white soul bearer of its owner, Lady K'abel. The alabaster jar's inclusion in this tomb strongly suggests its owner is the tomb's occupant.

Conclusions

These analyses permit association of the interred with the historically known figure Lady K'abel. This Late Classic queen, hailing from the powerful kaan dynastic seat of Calakmul, married Waka's ruler K'inich Bahlam II. Their joint rule was critical to kaan's hold on Waka’. This report on her interment contributes to further contextualization of the era's geopolitics in general and the nature of kaan authority more specifically. Ultimately, this information advances understanding of the role of queenship among kaan dynasts, including how they advanced statecraft and articulated their power.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala (IDAEH), the Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes de Guatemala (MCDG), and the Departamento de Monumentos Prehispánicos (DEMOPRE) for their support and permission to conduct research. We thank Kristin Hettich, Jerry Glick and the Jerome E. Glick Foundation, the Waka’ Foundation, and the Proyecto Arqueológico Waka’ (PAW) team who supported or contributed to this research, including David Freidel, Francisco Castañeda, Clarissa Cagnato, Jennifer Loughmiller-Cardinal, Emiliano Melgar Tísoc, Chloe Andrieu, Stanley Guenter, Michelle Rich, David McCormick, Zachary Hruby, René Ozaeta, Brett Houk, Evangelia Tsesmeli, Damien Marken, Tessa De Alarcón, and all our local collaborators. We appreciate comments from three anonymous reviewers, the Latin American Antiquity editors including Geoffrey Braswell and Julia Hendon, and College of Wooster (COW) student Olivia Frison De Angelis. This research was supported by the Fundación Patrimonio Cultural y Natural Maya (PACUNAM), the Alphawood Foundation, the Hitz Foundation, the University of New Mexico's Division for Equity and Inclusion, a COW Henry Luce III Fund for Distinguished Scholarship, and a COW Faculty Research Leave. All images are courtesy of MCDG and PAW.

Data Availability Statement

All Burial 61 materials are stored in the PAW laboratory in Guatemala City. For access, contact the PAW Laboratory, Guatemala City, Griselda Pérez, grisroble11@gmail.com; DEMOPRE-IDAEH, demoprearqueologia@gmail.com.