INTRODUCTION

Rydberg matter was predicted and measured in gases where a static clustering of protons or deuterons to comparably high densities is generated with densities up to 1023 cm−3 (Badiei & Holmlid, Reference Badiei and Holmlid2006). In contrast to gases, the appearance of ultrahigh density clusters of crystal defects in solids were observed in several experiments, where such configurations of very high density hydrogen states could be detected from SQUID measurements of magnetic response and conductivity (Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Heuser, Castanov, Miley, Lyakov and Mitin2005), indicating a special state with superconducting properties. These high density clusters have a long life and with the bosonic nature of deuterons—in contrast to protons—should be in a state of Bose-Einstein-Condensation at room temperature (Miley et al., Reference Miley, Hora, Philberth, Lipson, Shrestha, Marwan and Krivit2009).

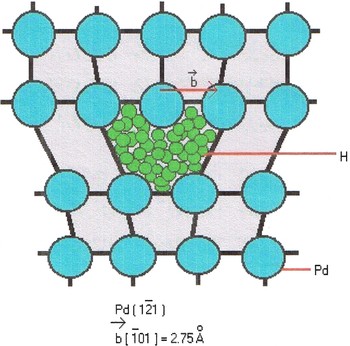

While these clusters were measured in metals at the interface against covering oxides (Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Heuser, Castanov, Miley, Lyakov and Mitin2005), the generation of these states within the whole volume of a metal (palladium, lithium, etc.) with crystal defects (Fig. 1; Miley et al., Reference Miley, Hora, Lipson, Luo and Shrestha2007, Reference Miley and Yang2008) is important. For surface states on metal oxides, the measurement of the ultrahigh ion densities of 1029 cm−3 was directly evident from the ion and neutral emission by laser probing. These surface states were produced involving catalytic techniques (Badiei et al., Reference Badiei, Andersson and Holmlid2009). The distance d between the deuterons was measured to be

compared with the theoretical value of 2.5 pm derived from the properties of inverted Rydberg matter. The energy release of the deuterons from the surface layer was measured as 630 ± 30 eV. The difference between protons and deuterons was directly observed and the deuteron state called D(-1) indicate well the bosonic property against the fermionic protons.

Fig. 1. (Color online) Cluster with more than 100 hydrogen atoms squeezed in palladium crystal defect with superconducting properties measured by SQUIDS (Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Heuser, Castanov, Miley, Lyakov and Mitin2005; Miley et al., Reference Miley, Hora, Lipson, Luo and Shrestha2007) is generated, see Figure 1 in Miley et al. (Reference Miley and Yang2008).

The material used in the experiments (Badiei et al., Reference Badiei, Andersson and Holmlid2009) as a catalyst for producing the ultradense deuterium is a highly porous iron oxide material similar to Fe2O3 doped with K, Ca, and other atoms. Thus, the number of defects or adsorption sites is very high relative to a metal and the open pore volume in the material is large, of course varying with the method used to measure it. Initially, the D(1) phase is formed in the pores, and it is then inverted to the ultradense deuterium D(-1). When probing the porous surface with the grazing incidence laser beam, fragments of the D(1) and D(-1) materials are removed from the sample surface.

The Rydberg matter is a long-lived form of matter, and the lowest possible excitation level D(1) or H(1) exists more or less permanently in the experiments (Badiei et al., Reference Badiei, Andersson and Holmlid2009). The clusters are not formed transiently. There is no indication that the phase D(-1) is not formed almost permanently. In the experiments, both D(1) and D(-1) were observed simultaneously. The experiments indicate that the material changes rapidly with almost no energy difference states D(1) and D(-1).

DENSITY OF CRYSTAL DEFECTS

After it was shown that hydrogen clusters of Rydberg matter are located in crystal defects at the surface, or at interfaces, or in the volume of the metal lattice, it is interesting to know what densities of such defects may be available. The density of defects at the surface of solid materials was found to be very similar in value to many materials around 1010 per cm2. This is known from luminescent materials for the surface traps of electrons into which the thermal mechanisms of loading or removing of electrons determines the activation energy, known from the Riehl-Schön model, as one of the first realization of the band level structure in semiconductors and insulators. This number could be measured also in the standard photoemission materials as the Görlich cathodes Cs3Sb and similar compounds. Filling these traps changes the work function of the emission (Hora & Kantlehner, Reference Hora and Kantlehner1969) and was identified from the temperature dependence of the photoemission (Frischmuth-Hoffmann et al., Reference Frischmuth-Hoffmann, Görlich and Hora1960; Hora et al., Reference Hora, Kantlehner and Riehl1965, Reference Hora and Kabiersch1968). Since Einstein's (Reference Einstein1905) result of a strict linearity of the emitted electrons on the number of incident photons, it was unknown (Frischmuth-Hoffmann et al., Reference Frischmuth-Hoffmann, Görlich and Hora1960; Hora et al., Reference Hora, Kantlehner and Riehl1965; Hora & Kabiersch, Reference Hora and Kabiersch1968; Hora & Kantlehner, Reference Hora and Kantlehner1969) how this strict linearity changed at very high photon densities into sub-linearity. This was especially observed when studying the single- and the two-photon emission, where at high intensities, the quantum yield changed into a square root dependence on the intensity (Boreham et al., Reference Boreham, Newman, Höpfl and Hora1995) for the Görlich cathodes, but also for the photoemission from silicon as measured by Malvezzi et al. (Reference Malvezzi, Kurz and Bloembergen1985). The mentioned standard density of surface traps was the reason that Shockley's Reference Shockley1950 prediction of the field effect transistor (MOS-FET) (O. Ritschel, private communication) could not work until it was possible to reduce the density of the surface traps at least by a factor 100, i.e., below 108 per cm2 for silicon. For the application of the ultradense hydrogen clusters, it is interesting to increase the density. To what extend this will be possible at the surface of crystals may be a question in view of the just mentioned results.

For the generation of higher densities of defects within the bulk (volume) of crystals, several processes are well known. It is possible instead of having the 1029 cm−3 deuteron density located within one place of an atom defect, there can well defects of two or more neighboring empty places be generated as known from the X-ray generated F- and the L-centers. It may be that this kind of centers may normally not be generated by mechanical treatment of the crystals but one may need the well known generation by radiation. This can be seen also from the sub-threshold electron beam irradiation on silicon (Hora, Reference Hora1983; Sari et al., Reference Sari, Osman, Doolan, Ghoranneviss, Hora, Höpfl, Benstetter and Hantehzadeh2005). When changing n- into p-conducting silicon crystals, a defect density of more than 1019 per cm3 was possible well under minor increase of the volume of the crystal and generation of voids as seen from the strongly reduced thermal conductivity of these crystals (Goldsmid et al., Reference Goldsmid, Hora and Paul1984). Therefore densities n D of defects may well be possible with the limit

where n s is the atomic density in the host crystal for the clusters. This means that the clusters may be placed each in an average distance of about 10 atoms in the host lattice. For higher densities and irreversible braking of the host crystal may happen as known from experiments (Hora, Reference Hora1983; Goldsmid et al., Reference Goldsmid, Hora and Paul1984). But if the crystalline voids are filled with the ultradense clusters, their interaction with the neighbor atoms of the host crystal may reduce the stress such that the crystal will not easily be broken into parts.

POSSIBLE HYDROGEN DENSITIES IN CLUSTER FILLED CRYSTALS FOR ICF TARGETS

After densities of 1029 per cm3 deuterium atoms in the clusters have been measured and a volume concentration of defects for hosting the clusters may be achieved under stable conditions with the densities of Eq. (2) in the whole crystal of palladium or preferably of lithium (Miley & Yang, Reference Miley and Yang2008), targets for laser fusion with densities 50:50 deuterium-tritium (DT) mixtures may be prepared. Taking a cluster density of 1/1000th for the clusters, the average DT density within the lithium crystal is then near 1026 per cm3. This is about 2000 times the solid state of DT. It seems to be preferable to ignite such a uniform pellet by indirect drive in a NIF (Moses, Reference Moses2008) experiment in order that the irradiated X-rays will penetrate the pellet uniformly for ignition. This would keep the advantages of indirect (X-ray) drive (Lindl, 2005) but would avoid the numerous problems of spark ignition. For this homogeneous reaction igniting uniformly in the volume of this density, the conditions of volume ignition (Hora & Ray, Reference Hora and Ray1978; Amendt et al., Reference Amendt, Robey, Harry, Park, Tipton, Turner, Milovich, Bono, Hibbard, Wallace and Glebov2005) are automatically fulfilled (Miley et al., Reference Miley, Hora, Osman, Evans and Toups2005), and the gains up to 200 times more fusion energy per incident laser energy may be sufficient for energy production.

Another application would be for the modified fast ignition scheme of Nuckolls and Wood (Reference Nuckolls, Wood, Hora and Miley2005), first disclosed in 2002, where a very intense 5 MeV electron beam is produced with a many petawatt-picosecond (PW-ps) laser pulse to ignite a large amount of modestly (12 times) solid state compressed DT for a controlled fusion reaction to produce energy with a gain of 10,000. However, this is a two step process because the electron beam to be produced by the PW-ps laser pulse at interaction can be generated only after the plasma for interaction has a more than 1000 times solid state by a preceding laser-compression. This pre-compression may in future be avoided by using the cluster target with the average 1000 times solid state DT density for generating the electron beam. This would then be a single step laser fusion energy generation as it was postulated by Dean (Reference Dean2008).

Another fast igniter modification is the side-on ignition of uncompressed DT or of proton-Boron11 fuel (Azizi et al., Reference Azizi, Malekynia, Hora, Ghoranneviss, Miley and He2009). This scheme needs the application of a very unique effect discovered only lately (Hora et al., Reference Hora, Badziak, Boody, Höpfl, Jungwirth, Kralikova, Krasa, Laska, Parys, Perina, Pfeifer and Rohlena2002, Reference Hora, Badziak, Read, Li, Liang, Liu Hong, Zhang, Osman, Miley, Zhang, He, Peng, Glowacz, Jablonski, Wolowski, Skladanowski, Jungwirth, Rohlena and Ullschmied2007) by applying laser pulses with a very high contrast ratio (cut-off prepulse by a factor 108) before the main pulse is interacting in order to avoid the otherwise always appearing relativistic self-focusing. The side-on ignition is the irradiation of laser driven highly directed plasma blocks with higher than 1011 Amps/cm2 ion current densities driven (Hora et al., Reference Hora, Badziak, Boody, Höpfl, Jungwirth, Kralikova, Krasa, Laska, Parys, Perina, Pfeifer and Rohlena2002, Reference Hora, Badziak, Read, Li, Liang, Liu Hong, Zhang, Osman, Miley, Zhang, He, Peng, Glowacz, Jablonski, Wolowski, Skladanowski, Jungwirth, Rohlena and Ullschmied2007) by nonlinear (ponderomotive) force acceleration Hora (Reference Hora1969). If this interaction could use cluster pellets with much higher than solid state density, the ignition condition could be further much more relaxed. Similar simplifications are possible for the proton-fast-igniter (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Brambrink, Audebert, Blazevic, Clarke, Cobble, Ruhl, Schlegel and Schreiber2005; Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, Blasevic, Ni, Rosmej, Roth, Tahir, Tauschwitz, Udrea, Vanentsov, Weyrich and Maron2005; Mulser et al., Reference Mulser, Kanapathipillai and Hoffmann2005) when using the high DT densities in lithium targets with ultrahigh density clusters.