Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 May 2005

The focus of this article is zero copula use in Sri Lankan English speech. Zero copula use has been at the heart of variationist studies, but has received little attention in New English studies because of its limited use in these varieties. In this article I look at zero copula in Sri Lankan English to determine whether the patterns of use parallel those of AAVE, Caribbean Creoles, or other copula studies on varieties of English including New Englishes. The theoretical issue raised in this article is whether zero copula use in Sri Lankan English can be seen as both a creole-like feature and an optional syntactic feature of those who use English a lot, but for whom it is not a native language, or as a substratal influence in language shift. The variable findings for present tense BE demonstrate that speakers of Sri Lankan English make only limited use of BE absence. BE absence appears to be optional in certain environments where Standard English would require the are copula/auxiliary. Zero copula use in Sri Lankan English speech is especially interesting because Sri Lankan English emerged from an educational background and not from a creole setting. However, the linguistic data for zero copula use in Sri Lankan English suggests that the type of complement and the preceding phonological environment play a significant role on zero copula use, which is comparable to that of other varieties of English, focusing on the study of BE absence.A shorter version of this article was presented under a different title at the Triangle Colloquium on Literature and Linguistics held at the University of Sheffield, UK on September 30, 2000. I wish to gratefully acknowledge the excellent comments and insights provided by the two journal reviewers on earlier drafts of this article. Any shortcomings that exist are my own. I would like to dedicate this work to Dr. Anthea Fraser Gupta (University of Leeds) and Prof. Siromi Fernando (University of Colombo).

In this article, I focus on zero copula use in Sri Lankan English. The BE verb is a feature in which a large number of variations can be found. For example:

Sentences with zero copula are available in some but not all contexts. At the same time, corresponding sentences with overt forms of the copula seem to be available in all contexts. The copula is an area in which a large amount of variation can be found. The main source of variability could be the irregular and highly anomalous form and behavior of BE within the morphology of the English verb itself. BE is unique among English verbs, in that it has eight different forms (see Table 1). Moreover, BE is the only verb to have a special form for the first-person singular of the present tense, and two distinct past forms (was, were).

The eight different forms of the BE verb

Throughout the literature on zero copula, the auxiliary and copula uses of BE are discussed together, so that the term “zero copula” is generally used to refer to both uses. Therefore, I will follow the same practice here. I will use the terms “zero copula” and “BE absence” interchangeably.

Sri Lanka is a small island in the Indian Ocean, with a land area of 65,610 square kilometers. Even though the people and culture of Sri Lanka are believed to have originated from India, the people of Sri Lanka, having inhabited the country for several centuries, have tended to identify themselves as a distinct nation from that of South India, which is mainly populated by Dravidian people. Although Sri Lanka has a dynastic history spanning 2500 years, it has been unified politically under a common government for only 150 years (for a detailed review, see Kearney, 1967:3ff.).

Since the introduction of English to Sri Lanka as part of the cultural baggage of colonialism in 1796, language and society in Sri Lanka have undergone massive changes. As A. Fernando (1986:16) noted, this period has seen the demise of the last Sinhala kingdom, the adoption of Western culture and way of life by a certain section of Sri Lankan society, the rise of a class liberated from feudal caste-associated occupations, the resurgence of nationalism, and finally, independence and its aftermath. Language has been linked in one way or another with most, if not all, of these events. Although the Portuguese managed to capture the coastal belt when they first invaded Sri Lanka in the 16th century, the culture and language of the Portuguese did not have a major impact on the people of Sri Lanka. However, the Portuguese language gave rise to the development of a Portuguese Creole in the maritime provinces (Jackson, 1990). However, a separate kingdom, uninfluenced by Western culture and language, remained in the interior of the country for two centuries, through changes from Portuguese to Dutch to British rule of parts of the country. With the capture of the Kandyan kingdom in 1815, the whole country came under colonial rule for the first time in history, thereby changing the course of Sri Lankan history.

In 1833, the British brought Ceylon under an increasingly centralized form of government. The integrity of Ceylon as a separate administrative unit was reinforced by its separation in 1802 from British India. By the time Ceylon gained independence in 1948, the people of Ceylon had shared nearly 150 years of relatively centralized and uniform colonial rule as a separate political unit (Kearney, 1967:3). After the granting of universal franchise in 1931, the Ceylonese began to play an active role in the political process. The revival of nationalism in the early 1930s culminated in independence in 1948. Despite the attainment of independence, however, the country has continued to face major setbacks resulting from social divisions such as class, caste, ethnicity, religion, and so forth.

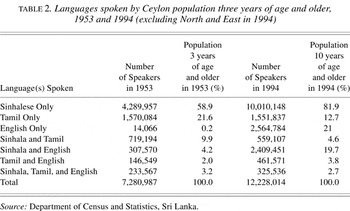

Kearney (1967:16) noted that language is one of the most important attributes delimiting each class and community in Sri Lanka, and that it has been a source of both emotional attachment and division between the different social classes and communities. The official statistics on the number of Sri Lankan English speakers and language use available show that in 1953, 80% of the population spoke only one language. Nearly 60% spoke only Sinhalese and more than 20% spoke only Tamil. English was spoken only by about 2% of the population. Both Sinhala and English were spoken only by 4.2%, while Tamil and English were spoken by 2%. The 1953 census defined the ability to speak a language as “the ability to conduct a short conversation, or understand and answer questions put in that language.”

From Table 2 it can be seen that, in 1953, English was the preserve of a small minority constituting only about 0.2% of the population. Forty years later, the increase in the number of people using English is very significant (21%), so that it can be safely said that even in the remotest parts of Sri Lanka, it would not be a difficult task to find people who have at least a basic knowledge of English. The available data since 1953 indicate how rapidly the English-speaking population has grown in the past 50 years. The numbers of people speaking Sinhala and English show a marked increase from 4.2% to 19.7%. Comparatively, those speaking Tamil and English show only a slight increase from 2.0% to 3.8%. As mentioned before, a large number of the Tamil population has been excluded from the 1994 demographic survey because of problems in the North and East. It is likely that this percentage would be much higher if enumeration had included the Tamil population in the North and East of Sri Lanka.

Languages spoken by Ceylon population three years of age and older, 1953 and 1994 (excluding North and East in 1994)

According to the 1981 population census, the total percentage of people ten years of age and over (both sexes) with the ability to read and write English, in both the rural and urban areas, is approximately 11.7%. Obviously, more people can speak English than claim to be able to read and write in it. Those under ten also speak English, but are not included in this data. Therefore, although the literacy rates for English in 1981 show a dramatic increase from 1953, when only 0.2% of the population were literate in English, actually speaking, this figure could be even higher today. This can be seen from data gathered in the 1994 demographic survey (see Table 2), which shows a dramatic increase in the population using English in 1994, even though it has excluded a large number of Tamil and Moor English speakers.

Despite the fact that the data from the censuses in 1981 and 2001 do not give a true picture of English literacy in Sri Lanka, it is still fairly clear that the use of English has grown immensely. This can be seen by whatever perspective or whatever measurements we use to study the growth of English. Those learning English at whatever level of education have increased in large numbers. According to the 1994 demographic survey, literacy in Sinhala or Tamil or English in Sri Lanka is 90.1%, which puts Sri Lanka on par with developed nations. Similarly, literacy in English has greatly increased (21%). Although there is no completely up-to-date data from 2002 that makes this self-evident, one can safely assume that since independence, the use of English, which was previously the preserve of a privileged few, has increased to include a greater proportion of people from different social strata.

From the commencement of British rule at the end of the 18th century, Sri Lanka was in practice governed in English. The foundation for the modern system of education was laid during this period. To stabilize colonial rule and advance its commercial interests, the British required a nucleus of local loyalists to staff the lower-ranking and middle-grade positions of governmental, commercial, and financial establishments, who were to become the intermediaries between the British and the local majority. English education was perceived as the means through which the essential intellectual and attitudinal preparations needed for such employment could be realized (Kearney, 1967:53). One of the insuperable difficulties of such a mission was the unavailability of suitably qualified English teachers. The missionaries had been practical enough to realize that mass proselytization could only be carried out by using the indigenous languages. Nevertheless, the advantages to be gained from teaching English to a select group of people prevailed, thus laying the foundation for English education in Sri Lanka.

Further impetus for the use of English in administration, the courts, and schools was provided by the Colebrook-Cameron commission report in 1831 (Kearney, 1967:53). Colebrooke called for greater opportunities in the Public service for Ceylonese, but stressed the necessity for recruits to possess competency in English. This proposal preceded by a few years an identical policy voiced in Thomas Macaulay's historic “Minute on Education” in 1835, which stated that English education would lead to the formation of “a class of persons who may be interpreters between us and the millions we govern—a class of person Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals and in intellect”(Education in Ceylon: A Centenary Volume 1969:600).

The policy to educate local people to staff the clerical and lower grades of the public service was also welcomed by caste groups, as it offered an opportunity to transcend barriers to social advancement enacted by the caste system. The emergence of an English-educated middle class created a new form of stratification based on education, wealth, and occupation. The middle class that adopted English as their first language, and with it the westernized mode of life and culture that is part and parcel of English life, gained momentum as a politically powerful and prestigious group (A. Fernando, 1986:18). Therefore, English deeply entrenched itself in this culturally select, educated elite who were the agents of British colonial rule. Thus, under British rule English became the language of a privileged few, while the indigenous languages, Sinhala and Tamil, remained the everyday languages of the majority.

From the early 19th century onward, the missionaries began to provide English education on a limited scale to the children of Europeans as well as the children of the upper classes. Their efforts at English education were fully supported by the government. The establishment of English schools in the late 19th century, however, led to the decline of the traditional Buddhist and Hindu schools, as the government neglected these schools in favor of the newly established English schools. In Sri Lanka, education in the indigenous languages had always been free, but the new English schools levied high fees, and as a result were barred to a majority of the people. This is highlighted by the English literacy rate provided by de Silva & de Silva (1990:10), who claimed that only 6.3% of the total population in 1946 were literate in English. The low literacy rate in English, after over a century of English education, pinpoints to the exclusivity of these schools in providing the secondary education that paved the way for legal and medical professions or good positions in the government. In fact, Passé (1948:75) noted that “the fields in which Ceylonese became famous during this period were the professions of law, medicine and politics.” In opposition, the Sinhala and Tamil schools confined their education to teaching basic literacy skills. Though restricted to a minority elite in the early days of colonialism, English, nonetheless, came to be viewed as a path of upward social mobility by the majority of people.

After independence in 1948, the English-speaking westernized elite, who were comprised of Sinhalese, Tamils, and Muslims,1

In Sri Lanka, the Muslims, or the Moor community, are regarded as a separate ethnic group.

Previous studies on Sri Lankan English (Fernando, 1977; Kandiah, 1979, 1981; Parakrama, 1995) have examined a number of features as being distinctive of Sri Lankan English. These include syntactic deletion in question and answer sequences (Kandiah, 1996), topicalization, word order differences, and so forth. The most distinctive feature of Sri Lankan English speech is its syntax, which has some commonalities with other non-standard contact varieties, as evidenced by this study. These include features such as variable copula use, article use, and variation in word order. In the case of Sri Lanka, these features are also present in the principle substrate language, Sinhala. However, as mentioned before, I will attempt to show that zero copula use in Sri Lankan English is not merely a consequence of the interaction with the substrate, although the fact that there is no copula in the substrate languages may be an important factor, the patterns that emerged suggest that it could more likely be a result of some other factor, such as economizing speech or possibly even universal grammar.

In this article, I examine the discourse of 18 habitual users

2By habitual users, I mean, people who use English a lot, but for whom it is neither a first nor native language. These people frequently use English in different domains but have another language as their “best” and/or “native” language.

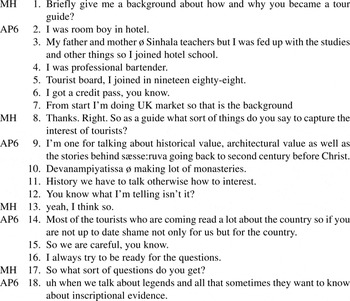

. In this excerpt, MH is the interviewer and AP6 is the interviewee.

Examples of BE variation can be seen in lines (3) and (10). Although there are examples of the use of is and are full forms, there are no examples of contracted is and are forms in this excerpt, and in fact, there are few instances of BE contraction in all my interviews. However, lines (7), (9), and (12) show evidence of the contracted form I'm.

The present study is the first quantitative study of copula absence in Sri Lankan English. My analysis reveals that the copula could have potentially occurred 1419 times (including its use with am and WIT tokens), out of which the copula was absent in 87 instances. I consider this figure to be quite high considering that the data were gathered in interview situations. Moreover, the pattern of zero copula use is consistent with that of other New English varieties and creoles. On the basis of these results, I argue that zero copula use in Sri Lankan English cannot simply be seen as an influence of the substrate language, Sinhala, although language transfer could be considered one possibility among many.

The data for the present analysis were gathered from interviews with 18 habitual speakers of Sri Lankan English, who are tour guides by profession. I was introduced to these people through friends, and these networks helped “create a sense of familiarity between me and my informants and ensure more casual and relaxed interviews” (Hannah, 1997:348). As Labov (1984:31ff.) noted, the central theme of sociolinguistic interviews is a keen awareness of the limitation of individual interviews. But it remains true that no other method will give us the large body of well-recorded data and the demographic information we need to study a certain group systematically. In the sociolinguistic interview, Labov (1984:31) created a “spontaneous” section, to better enable the interviewer to gain the most colloquial range of language by engaging the subjects in conversation, thereby rendering them less conscious of their speech. As my interviews were designed to elicit large amounts of speech, a single interview generally lasted about one hour or a little longer and took place in informants' homes or at the tour guides' office at their convenience. Prior to entering the field I had prepared a list of 25 interview questions. However, in an attempt to keep the tone of the interviews informal, I did not follow my printed questionnaire. Instead, I allowed my informants' interests and work experiences to guide my questions, lingering long over topics that drew them in while passing over ones that seemed to hold little interest for them (Hannah, 1997:349). The topics we explored broadly fell into two categories: (1) nonlinguistic (subject's age, schooling, work experience, family, religious affiliations, etc.) and (2) linguistic (pronunciation, grammar, attitudes toward language).

Although the interviews were conducted in very relaxed and comfortable surroundings, it must be noted that “the possibility of interlocutor effect is virtually inescapable in the interview context” (Hannah, 1997:349). Moreover, as Hannah noted, it is likely that my presence alone as an overhearer, or as a known and ratified listener according to Bell's (1984) schema, could have had a standardizing effect on the speech of my informants. Although it was impossible to remove myself fully from the interview context, I attempted to limit the effect of accommodation as much as possible by allowing my informants to speak as much as they wanted and by taking a less active role in the interviews.

To build the database for this analysis, I examined every potential finite form of BE, excluding a number of cases that include the “don't count” cases (Blake, 1997:57ff.). These cases have some relevant form of BE, but are excluded for other reasons. These include tokens of BE that occur with nonfinite forms, such as:

All other BE forms were included in the analysis. Whereas studies on BE variation in monolingual settings generally do not include BE occurring with the third-person singular pronouns what, it, and that, (referred to as WIT), studies on new varieties of English do, because there is variability in this context. In most studies, these forms usually comprise a large proportion of the data. Similarly, in my corpus, the WIT cases comprise 205 tokens out of 1332 (without absences). There are more cases of BE with pronominal it and that than there are with pronominal what.

Zero copula use is a widely known feature of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and some varieties of Southern American English (Bailey & Maynor, 1985; Feagin, 1979; Labov, 1969; Wolfram, 1974) spoken by working-class White people, in which a form of be is absent in situations where Standard English would normally require one. Rickford et al. (1991) stated that AAVE is the only American dialect where is deletion is found. Rickford et al. (1991) also found occasional instances of are deletion in some European American dialects. He also discussed copula variation playing a large role in the origin debate of AAVE. He presented all previously stated methodologies of the origin debate, including the Dialectologist and also the Creolist approaches, in order to compare all theories of copula variation in AAVE. There are two specific views on the origin of AAVE. The Dialectologist approach (Krapp, 1924, 1925; Kurath, 1928, 1949), followed by Labov (1969), assumed that all of the distinguishing features of AAVE were created out of existing dialects of American English, including the feature of copula absence. Labov (1969) argued that the copula can only delete where contraction is possible and every deleted copula was previously contracted and was an underlying form. Romaine (1982), however, argued that AAVE is a creole created by the African Americans, and is not directly derived from English. In this case, Romaine argued that the copula is not underlyingly present, but is inserted (variably) and then contracted (variably). These different hypotheses have had important implications for the analysis of BE. However, as the origin debate has not ended, and because I will not directly enter this debate, this study will remain neutral with respect to these hypotheses.

Labov (1969) listed a few environmental constraints for copula absence. Listed from most frequent to least frequent, these include: following grammatical category (i.e., before the verb gonna, before a progressive verb, a locative, an adjective, a noun phrase) and preceding grammatical category (i.e., a noun phrase, a pronoun). He also noted that are favors absence over is. Both are and is absences are more likely to follow pronouns than noun phrases. Finally, Labov stated that the complements gonna and verb+ing favor absence over predicate nominatives and predicate adjectives. Labov's constraints were also confirmed by Rickford (1998). Later, Rickford (1999) looked at a few other constraints and found that age is a very important constraint on copula absence. He also found the second-person plural are to be more favorable to absence than the third-person singular is. As the main purpose of this study is to analyze BE absence constraints in the data with the objective of examining similarities and differences between different varieties of English, I will compare the current constraints with those previously found, and examine the claim that are absence is more common than is absence.

As Labov (1972:48) noted, because the absence of the copula is one of the most well-known characteristics of AAVE, in these varieties of English, one can say He working, where Standard English would say He is working. This zero use has frequently been described by linguists as zero copula, although it is sometimes described as zero auxiliary before progressive verb forms, as in He working, and before going to or gon(na), as in He gon do it / he going to do it. This usage is perhaps even more characteristic of AAVE than is invariant habitual be (Labov, 1972:70). Labov said, “forms of BE other than is and are are rarely deleted.” Similarly, as with all dialectal features, zero copula use is more systematic than it might at first appear. As the previous examples indicate, the most frequently used zero forms of BE are the present tense inflected forms (although was and were can also be occasionally zero), and among present forms, the most frequently nonoccurring forms are is and are; am is frequently contracted but rarely deleted. Invariant or nonfinite forms, such as be in You have to be good cannot be zero, nor can forms that are stressed (He is tall) or that come at the end of a clause (That's what he is). In the late 1960s, Labov captured most of these generalizations, stating that wherever Standard English can contract is or are, AAVE can delete it. Equally systematic are the quantitative regularities of the zero copula. Throughout the United States, zero BE is less frequent when followed by a noun (He a man) than when followed by an adjective (He happy). It is most frequent when followed by progressives and gon(na) (Labov, 1969:87). This pattern of zero use is also found in Gullah and Caribbean Creole varieties of English (Bickerton, 1971, 1972; Stewart, 1969). The fact that zero copula use has not been found to be a feature of the British dialects of English that colonial settlers brought to the United States, is seen as one of the strongest indicators that the development of AAVE may have been influenced by Caribbean English creoles or that AAVE itself may have evolved from an American creole-like ancestor. Wolfram (1974:522) reported that he was unable to find evidence of zero copula use in a selective search of the available records of British varieties,3

As Wolfram (1974:522) went on to note: “Of course, it must be admitted that the inability to find copula deletion in British varieties does not necessarily mean that it doesn't occur; but since copula deletion is a rather noticeable phenomenon, one would suspect that if it had occurred, there would be some report of its existence in the major sources.”

Biber et al's study of British English (1999:158) showed evidence that in colloquial British English the auxiliary may be zero only if the subject of the sentence is zero:

They note that a number of these examples would be regarded by purists as incorrect English despite their frequency in real conversation of educated speakers.

Since Labov's ground-breaking study in 1969, zero copula use has been at the heart of much variationist work (Holm, 1984; Wolfram, 1974) and is one of the most studied features of AAVE and a number of other creoles/pidgins and new varieties of English. Most studies on copula absence outside the United States have been designed for the express purpose of comparison with AAVE. While most studies on copula absence examine zero copula behavior in several linguistic environments, the effect of following grammatical category on zero copula has been at the center of discussions. This comes from the fact that researchers have found consistently statistically significant results with this syntactic feature.

Apart from research on the AAVE copula, other interesting works on BE in “New Englishes” include Ho and Platt's (1993:30ff) and Platt and Weber's (1980:62ff) investigation of BE in Singapore English, and Mesthrie's (1992:49ff) examination of BE in South African Indian English (SAIE), which shows a similar systematicity to earlier copula studies. Platt and Weber (1980:62ff) observed that in Singapore English BE is not always realized where it would appear in Standard British English in the copula function, and that it is also not realized as an auxiliary in constructions such as He is working.

Zero copula occurs when either copula or auxiliary BE is absent from an utterance in which BE is possible. For the dependent variable of zero copula, there are three variants. A speaker can either produce a full form (e.g., They are leaving, She is going out), a contracted form (e.g., They're leaving, She's going out), or a zero form (e.g., They [caret ] leaving, She [caret ] going out). Although the respondents in my study often used contraction for I'm and there's, in Sri Lankan English, contracted forms are not very common in conversation, as people tend to use more full forms than contracted forms. Because most of my respondents tended to use the full form of the BE verb rather than the contracted form, I will not distinguish between full and contracted forms in this study.

As in previous studies, in this article I present and discuss my variable findings for present tense copula behavior, considering its absence in relation to several linguistic constraints. The linguistic description presented for zero copula in Sri Lankan English lends new and needed data for understanding the use of BE variation in a new variety of English.

In variable rule analysis, a linguistic feature is realized in alternating forms as opposed to categorical forms. In the case of BE variability, for example, Wolfram (1969:166) stated that “it is essential to separate environments where there is no variability from those where there is legitimate variation between the presence and absence of the copula. Failure to distinguish these environments would skew the figures of systematic variation.” In the following section, then, I discuss the grammatical environments in which BE is possible in Sri Lankan English.

As BE variation in Sri Lankan English has not been studied as a variable feature before, it is somewhat difficult to establish the grammatical environments in which BE is possible. In my data there is some evidence that BE is also possible in environments in which Standard English does not require it, as in structures with BE+stem. These are given below:

Examples 2–9 (from my data) bear a close resemblance to examples given by Gupta (1994) for Singapore Colloquial English. Although BE+stem forms only account for 9 tokens, it shows evidence of the use of BE in environments in which Standard English does not normally require a copula. These tokens could be seen as an attempt at hypercorrection (Gupta, 2000:154) where the speakers are attempting to produce the target norm BE+ing. My examples indicate that this variable construction is possible with present tense forms such as 'm, am, is, and are. Although there is no evidence of the variable use of past forms of BE+stem, the examples from Ho and Platt's (1993:34ff) Singapore English corpus showed that when the past is referred to, the past forms of BE are possible.

There appears to be considerable variation among researchers on matters such as what forms to count and how they should be counted (Blake, 1997:57). It is important to note in this connection that BE presence is very much a feature of colloquial Sri Lankan English speech. There is also no reason to expect my respondents to be anymore consistent across speakers than speakers of other varieties of English, and there is also variation between individual speakers in the corpus.

Almost all copula researchers agree that nonfinite and past tense forms of the copula are almost invariably present in full form, for example, She will be here tomorrow; and She was here yesterday; that am is almost categorically present in contracted form, for example, I'm here; and that the only forms that regularly allow full, contracted and zero options are the remaining forms is and are (Labov, 1969:718ff).

BE variation in monolingual settings has been generally confined to studying the present tense copula, because of the systematic variation observed for these copula forms in previous studies. However, studies done in multilingual settings, such as Singapore and South Africa have shown that BE absence could be possible in past environments proving that the past tense copula behaves in a similar fashion to that of the present tense copula forms. However, these varieties are all ones in which tense marking is optional too.

There are three instances of zero copula with past time reference in my data. These include the present participle (V+ing) and past participle environments (V+ed). This presence suggests that past-time-reference zero copula could be a variant of BE used by some speakers of Sri Lankan English. Although this can be seen as an area which needs further investigation, I have, however, excluded the past-time-reference form was from my analysis, as the tokens are insufficient for a thorough analysis. The three examples are given next:

Although Labov (1969) did not include cases where BE is used with the second-person singular or plural subjects in AAVE, arguing that unlike is, are does not get reduced via a copula deletion rule, all subsequent research on BE variation include are in their analysis (Baugh, 1979; Mesthrie, 1992; Ho & Platt, 1993; Platt, Weber, & Ho, 1984; Platt & Weber, 1980; Rickford et al., 1991; Wolfram, 1974). Rickford et al. (1991:105ff) found that, “is and are behave similarly enough to be treated together, making the data pool larger and more robust, and ensuring that their similarities in constraints effects need to be stated only once.” However, because my sample shows that BE absence is more likely with copula are than with copula is, I will separate BE absence involving are and is.

A few examples from my data in which BE is not realized where it would appear in Standard English either as a copula or auxiliary are given next. These examples exemplify the fact that the realization of BE depends to a great extent on the type of grammatical environment that follows the verb.

In analyzing BE variation in my data, I use some of the main grammatical environments used by Labov (1969), Wolfram (1974), Rickford et al. (1991:109), Platt et al. (1984), and Platt and Weber (1980).

In this article, BE absence is calculated by tabulating the proportion of cases in which the form actually occurs in the relevant environment, compared to the number of absent, contracted, and full forms.

I will begin my analysis of zero copula use by first discussing the relative frequency of zero copula by form absent for the individual speakers in my corpus, as well as for the whole group. Figures are broken down according to whether the absent copula form is is or are. Table 3 summarizes the rate of zero copula for the forms is and are, as well as the rate of total BE absences for each individual speaker. Although the pool of BE tokens is small for my sample, the absences are revealing. The speakers reveal a pattern of BE absence in which are copula absence is favored over is, depending on the following grammatical environment. However, Table 3 indicates that unlike in Singapore English and other varieties of New English, I am or I'm is never reduced to I, although occasionally the auxiliary is left out with third-person singular 's or is if the subject of the sentence is zero.

Zero copula by individual speakers (This data does not include the count for am)

Although there is anectodal evidence of BE variation in Sri Lankan English, it is noteworthy that the results shown in Table 3 for Sri Lankan English speakers are the first of its kind, as the use of BE variation has not been previously studied as a feature of Sri Lankan English. Kandiah (1996:114) provided some examples of zero copula in his discussion of syntactic deletion in Sri Lankan English where copula is is absent.

In my data, the speakers who use zero copula display a preference for BE absence with are rather than with is. From Table 3 it can be seen that the respondents' use of zero copula is quite low. When comparing the respondents' BE absence of is and are, the data shows that there is considerably more are absence (17.2%), but fairly limited is absence (2.4%). In fact, 2 of the 18 informants I studied did not show any BE absence at all, and out of the 16 informants who used BE absence, 7 did not use is absence at all. This data is somewhat similar to Wolfram's (1974:507–514) data for White speakers in Franklin County, Mississippi. Thirty of the 45 White speakers whose speech was analyzed by Wolfram showed no is absence at all, and among those who used BE absence, are absence was considerably higher (58%) compared to is absence (6.5%), which was quite limited. In terms of is absence, then, the difference between my data and copula studies in creole varieties is noticeable, and qualitative, like Wolfram's data for the White speakers from Mississippi. Similarly, the overall patterns for Feagin's (1979) study of White speakers from Alabama resemble my data. In her data, the percentages are low for is absence: 1.7% for the upper class, 5.8% for the urban working class, and 6.8% for the rural working class. For are absence, however, the figures are higher: 17.9% for the upper class, 35.3% for the urban working class, and 56.3% for the rural working class. The fact that BE absence does not appear in British dialects whose historical antecedents can be seen as the source for all these varieties of English, led Wolfram (1974:524) to suggest that “copula absence in white Southern speech may have been assimilated from decreolizing black speech.” This however, does not explain the similar patterns that occur in Sri Lankan English and other Englishes.

Like most other varieties of English, one of the environments in which the respondents mostly used are absence was in the future environment going to (referred to as gonna in the literature on copula studies), and before adjectives and past participles, which seemed to be treated on a par. They appeared to use the least number of are absence with locative and NP environments (see Table 4).

Are absence by type of complement

This pattern (going to > Adj/Past participle > V-ing > NP > Loc) is not consistent with the general pattern of previous studies, which is gonna/V-ing > Adj/Past participle > Loc > NP. What is most interesting about the Sri Lankan English data is the 54% rate for the future marker going to. As in most other studies, the future marker appears to favor zero are followed by adjectives (these places [caret ] very bad) and past participles (e.g., worried, forgotten), which seem to behave similarly. The 17% absence in the adjective environment is much lower than in other copula studies, although quite high for Sri Lankan English.

Baugh's (1979) reanalysis of Labov's (1969) data found a pattern that Holm (1984) suggested should be prominent, that is, the zero copula occurs much more frequently in the adjective environment than the locative environment. In the following years, this pattern, along with the type of complement hierarchy was also found for varieties of English that do not have a creole ancestry, but is the result of education. However, the adjective/locative distinction has not been consistent either in the Afro American Englishes or in the New English studies done to date. For instance, Baugh (1979) did not find the same pattern for the adjective environment that he found for Labov's (1969) corpus when analyzing his own data.

In my data, there is no are absence in the locative position, whereas adjectives seem to favor absence. Furthermore, the locative, NP, and present participle environments are ranked somewhat differently among my informants; in actuality their use of are absence is very low with the NP environment (1%), whereas their adjective and past participle rates are very close to one another. The type of complement is the most interesting in the analysis for are absence, with going to most favorable to zeros, followed by adjectives and past participles, which are on a par, and present participles, which is in the middle, and NPs and locatives last.

The fact that are absence appears to have the highest rate of zeros with the going to environment, as in other studies, is quite intriguing. Although the rate of zeros is high for going to, Sri Lankan English differs from other copula studies in having locatives as the least favorable environment. Singler's (1991) copula absence findings for acrolect speakers of Liberian Settler English showed that his results for zeros with type of complement are somewhat similar to my data. For example, his informants did not have any zeros in the locative environment (see Table 5) although their zero use in the NP environment is slightly higher (5%) than my data (1%). Likewise, Singler's data also confirmed that adjectives are favorable to zeros (13%). The only difference in his data is the absence of zeros in the present participle and future going to environments. Similarly, Wolfram's (1974) data from White speakers in Mississippi confirmed that locatives do not favor zeros. Hence, these data suggest that the pattern for copula absence is not consistent, even among White varieties of English.

Zero copula usage by type of complement in AAVE, Creoles, White American Vernacular English, and New Englishes

The two environments that may be preceded by BE, present participle and future going to, rank differently in my data, with the future marker going to showing the highest rate of zero copula and the present participle environment taking a lower rate of zero copula tokens (see Figure 1). In my corpus zero copula is least likely to occur in the locative environment. Apart from the future going to environment, the other environments that appear to influence zero copula use are the adjective and past participle environments. The rate that a zero copula was used with the adjective and past participle environments is almost identical (adjective 17%, past participles 16%). If combined, the percentage of BE absence for adjectives and V+ed would remain unchanged at 17%, hence the justification for treating them together. The reason why the percentage of BE absence for adjectives and past participles match very closely could be because adjectives behave similarly to -ed verbs. For instance, Holm (1984:298) noted that adjectives can function as a subclass of verbs, and therefore, would require a copula no more than a verb (requiring a copula) would. On this basis, he claimed that the adjectival environment could be expected to be more favorable to BE absence.

BE absence by type of complement

As in other New Englishes, particularly Singapore English (Ho & Platt, 1993:40), the absence of BE in Sri Lankan English speech is particularly high if the predicative adjective contains an intensifier such as very. Ho and Platt's (1993:40ff) and Platt and Weber's (1980:62ff) statistical findings for BE absence in Singapore English also show that the highest number of nonoccurrences of BE is before predicative adjectives. Some examples of BE absence from Singapore English are given next:

As can be seen, although Singapore English has zero copula with the first person singular I, this is not a feature of Sri Lankan English speech. BE absence in Sri Lankan English appears to be more common with other person-number categories such as you, we, and they.

Platt and Weber (1980:174) also provided evidence for BE absence from Malaysian English, explaining how the BE verb is not always used before adjectives, predicate nominals, in adverbial constructions referring to location, and in auxiliary constructions.

Singapore English and Malaysian English, like Sri Lankan English, arose as a result of formalized colonial education. Presumably, they do not have a creole ancestry such as that of AAVE or other Caribbean Creoles. Nevertheless, the presence of BE variation in these Englishes is quite intriguing. As Bickerton (1986) and Mufwene (1996) suggested, this may be because speakers of English today learn the rules of a “restructured” English, as a consequence of its contact with other languages and it is far removed from the English learned during colonial times. For instance, in Sri Lankan English speech, the future marker going to appears to be the most favorable for are absence (see Table 5). This is similar to BE absence in the speech of White folk speakers from Eastern Central Texas, as reported in Bailey and Maynor (1985). Not only did the White folk speakers show considerably more are absence (36%) than is absence (2%), but the effect of following grammatical environment is also similar, with more absences with gonna (54%) and V+ing (34%) and the least absences with locative and NP environments. The ordering of following grammatical category in (African) American varieties, however, shows a clearer split between auxiliary gonna/V+ing and copula (Adj, Loc, NP) than do the orderings in other varieties of English listed in Table 5.

As discussed before, although the type of complement has a significant effect on zero copula in different Englishes, the pattern itself is not consistent across different varieties of English used in multilingual and monolingual settings. For example, in South African Indian English (SAIE) (Mesthrie, 1992:67–70), the patterns of nonphonological copula absence by type of complement are quite different from that of studies of AAVE. In SAIE, copula absence is highest (33%) before NPs, and lower before adjectives (15%) and prepositional phrases (11%) (Mesthrie, 1992:50). Similarly, the pattern in Sri Lankan English is different from that of SAIE, with the exception that Sri Lankan English appears to have the highest rate of zero copula for the future going to environment. Whether similar or different patterns would show up in other varieties of English, and the extent to which we can draw a firm line between second language acquisition / shift and pidginization / creolization (cf., Anderson, 1983) remains to be determined. As Rickford (1998:180) noted, at present, the typological similarities and sociohistorical links between creoles and other varieties of English suggest that they may have been subject to similar creolizing (if not decreolizing) influences.

Overall, the results for are absence by type of complement show much variation across studies. The only similarity between Sri Lanken English and other New Englishes appears to be the use of BE absence before adjectival intensifiers. Thus, it can be assumed that are absence is a result of a complex process other than influence from the indigenous languages.

In terms of preceding phonological environment, a vowel appears to favor are absence more than a preceding consonant (see Table 6). Fasold and Nakano (1996:389) claimed that the effect of the preceding phonological environment is a better candidate for decisive quantitative data, because the effects of preceding consonants and vowels tend to favor and inhibit contraction and deletion in opposing ways. According to them, zero copula is more likely to occur after consonants, because consonants favor deletion, whereas vowels favor contraction. Likewise, Rickford et al. (1991:130) suggested that the phonological environment may be a constraint on BE absence based on the fact that all the pronouns end in a vowel. This is confirmed by Mesthrie (1992:49) who showed that BE absence in SAIE is mostly phonological in nature, the segment most affected in this variety being

. In SAIE, are or its reduced form 're is often zero between a word-final vowel and a word-initial consonant, as in you [caret ] very clever.

Form zero by preceding phonological environment

BE variation by preceding phonological environment

My respondents also appear to leave out are with vowels more than with consonants. This could be because 20 of the subject NPs used in my data end in a vowel, in addition to the pronouns, which end in a vowel, that is, first-person plural (we), second-person plural (you), and third-person plural (they), which include 30 tokens. A zero copula was more often used with NPs that had word-final consonants than with word-final vowels (see Table 7).

Zero copula by subject NP type

Zero copula is used more where an are is generally required than in environments where is is used. Within the zero is/are subset of tokens there is a clear distinction between a preceding consonant and a preceding vowel (Table 6). For instance, are is absent more with preceding vowels (10.7%) than with preceding consonants (6.5%), whereas is is absent more with preceding consonants (1.6%) compared with preceding vowels (0.7%).

Some examples are:

With the subject environments (see Figure 3) much the same pattern appears as with preceding phonological environment. For all the respondents, the rate of absence with subject NPs is higher than with personal pronouns.

BE variation by type of subject

The subject environments in which zero BE can potentially occur include absence that involves first-person singular (I), second-person plural/singular (you), third-person singular (s/he), plural pronouns (we, you, they, you all), and singular and plural noun subjects.

What is striking about this data (see Figure 3) is the clear contrast that can be seen between personal pronouns and other pronouns, such as what, it, and that, which show no BE absence at all. For all the respondents who use zero copula, BE absence is possible with personal pronouns but not with other pronouns, such as what, it, and that. Although zero copula is used with personal pronouns, a glance at Figure 3 shows that the rate of absence with personal pronouns is much less than with NPs. Interestingly, however, there is no BE absence with other pronouns such as this and those and the dummy subjects it, that, and what. This suggests that the subject environment is not all that influential on BE absence in Sri Lankan English speech.

As with other studies on BE absence, zero copula use with subject environment in Sri Lankan English shows some parallels with other new varieties of English, with respondents using zero copula with a preceding subject NP followed by personal pronouns, in particular, you. However, there is no BE absence with the pronouns I and s/he (see Figure 3). At the other end, there is an interesting contrast with pronouns such as it, that, and what and other pronouns such as which, there, and somebody. Because of the pro-drop feature in Sri Lankan English, in environments where it is possible to use it as an empty subject, very often people might leave out both it + the auxiliary.

It is, however, difficult to discuss these results in a meaningful way, as there are many inconsistencies across different studies. Some new varieties of English use zero copula with it, that, and what, whereas others do not. For instance, Singapore colloquial English does not use a zero auxiliary with it, because it does not have it as a dummy subject (Gupta, 1994). Similarly, SAIE appears to favor absence with that, this, and what, but not it. Some examples from SAIE are given next:

Finally, BE absence does not appear to be used with the person of the subject, for example, first-person singular (I am), and third-person singular (s/he is). In Sri Lankan English a zero copula is mostly used with the second-person singular / plural forms of BE, but it is never used with the first-person singular (I am).

In the previous section we have seen that are absence is more common in Sri Lankan English speech than is absence. Are absence appears to be constrained by following grammatical environment and preceding phonological environment. Most copula studies of AAVE, while not describing are absence in detail, maintain that is absence is unique to AAVE. In his ground-breaking study, Labov (1969:754–755) claimed that there was no evidence of is absence in varieties of White English, and this was confirmed by other linguists such as Fasold and Wolfram (1970:68) who, on the basis of preliminary evidence, concluded that is absence is not possible for White speakers. This evidence suggests that is absence is not as likely to be used in varieties of English that arose as a result of colonialism. Because is absence is very low compared to are absence in my data, I tabulated the incidence of is absence for my informants using the same general strategy used in tabulating are absence. From the data provided in Table 3, our attention is immediately drawn to the low overall nonuse of is. And for those who use is absence, the realization is generally limited to rather few examples. Only 6 of the 16 informants who used are absence used is absence. Out of these 6 informants only 3 informants had more than one instance of is absence. The low incidence of is absence among speakers suggests that is absence is not optional in Sri Lankan English speech. As Wolfram (1974:514) suggested for his White speakers, it is possible that these informants have two lects with reference to BE absence: one where it is not possible, and one where it is possible to a quite limited extent.

Although I am dealing with a very limited number of examples of is absence, because of its overall restriction in Sri Lankan English speech, it is possible to see if the same environments constraining are absence are found to have an affect on is absence. The effect of following grammatical environment on is absence is shown in Table 8.

Is absence by following grammatical environment

Despite the limited number of examples, the figures for is absence, except for going to (see Table 8), tend to support the constraints discussed for are. At any rate, the figures certainly do not seriously contradict the content discussed for are absence. The patterning of is absence, although limited in terms of the number of informants who use it and the frequency with which it is used, does certainly appear to be a feature found among some Sri Lankan English speakers. The ability to vary the use of the copula by using it in certain instances and not in others appears to give speakers a measure of power over the language. It allows speakers to manipulate and appropriate the language in pragmatically meaningful ways. Although not widespread, the use of BE variation suggests that it is indeed a characteristic of Sri Lankan English speech.

Zero copula has been studied as a feature of universal grammar. The preceding discussion shows that Sri Lankan English speakers only make limited use of zero copula. From the analysis it appears that the use of BE is optional in Sri Lankan English speech, so that it is possible to use it or not. As we have seen, BE absence is most common when the BE form required is are.

There is no obvious equivalent to the English copula in spoken Sinhala (Gair, 1998:88), which takes the following structure:

As we can see, there is no overt copula linking the two nominal phrases in the Sinhala example. Therefore, in speech, Sri Lankan English speakers could vary between, for example,

Although on the surface, the lack of an overt copula in Sinhala could be seen as a reason for the use of a zero copula or auxiliary, this fails to explain the pattern of BE absence that is noticeable in Sri Lankan English. Then how do we explain BE absence in Sri Lankan English? Sri Lankan English (like many other New Englishes) is a variety of English that has resulted from being spoken by people who use more than one language. Schneider (2003) noted that the contact situation can often result in the grammatical structure of the native language being transferred to the second language. Another possible theory that suggests itself is Bybee's (2001) view that it is constant language use that produces over time the distribution found in the lexicon. She suggested that regularly used grammatical items may become absent to make production more efficient and economical. From the data, it is apparent that speakers only make limited use of zero copula in their speech, and as mentioned before, BE presence is as much a feature of Sri Lankan English speech as absence. The essential question at this point, then, is how we might explain this tendency and what this ultimately means with respect to the grammar of Sri Lankan English. Because this is the first systematic analysis of BE variation in Sri Lankan English, I suggest that more investigations need to be carried out on the speech of other Sri Lankan English speakers, preferably in more unmonitored contexts, before venturing an explanation. Though the links to other varieties of English (and to other languages) support the universal grammar arguments.

In this article, I have identified several major trends in the data. First, the type of complement appears to have a significant effect on zero copula use with a favoring for the future marker going to and adjectival environments. Second, a preceding vowel / consonant distinction appears to have an important effect on zero use and may be a more influential factor than the type of subject or type of complement, but more research needs to be done to establish this fact. Third, the data appears to favor NPs over personal pronouns, whereas other pronouns totally disfavor zero use. Finally, the person of the subject, for example, first-person singular and third-person singular, shows no favoring for zeros. The only person of the subject that appears to favor zero copula is the second-person plural / singular.

I have presented data from a variety of New English, namely colloquial Sri Lankan English, which I hope has contributed, even in a small way, to better understanding the syntactic features of New Englishes. In previous literature, zero copula use has not been systematically studied as a feature of Sri Lankan English. My data, however, exhibit frequencies of variable BE use that are almost equal to those found among adult speakers from other New English contexts, such as Singapore and South Africa. Moreover, the pattern for zero copula use exhibited in the present data resembles to some extent those patterns found for other varieties of English, particularly with regard to the type of complement following BE and the vowel / consonant distinction, and are therefore not wholly attributable to influence from Sinhala. These results suggests that variable zero copula use in Sri Lankan English speech may, in fact, be the result of universal grammar tendencies.

Much of the debate surrounding the syntactic features of New Englishes hinges on the source of a particular feature. To explain the source of BE variation in varieties of English that have developed in an educational setting, it would prove useful to study the behavior of the BE verb in particular grammatical environments in New English contexts.

In addition, this study also suggests that we have to look closely at different ways of collecting data. As Hannah (1997:365) noted, it is not possible to assume that a speaker's entire linguistic repertoire can be captured within the course of a sociolinguistic interview. For instance, the high rate of BE presence in my data suggests that despite the interviews being informal and friendly, my sample may not be completely representative of the most colloquial range. In unmonitored speech, the rate of zero copula use might be even higher (Hannah, 1997:366).

Moreover, the overall presence of BE in the data highlights the speakers' awareness of Standard English rules. Although aware of Standard English rules, the ease with which the rules are manipulated shows that for these speakers zero are is optional in certain grammatical environments.

Languages spoken by Ceylon population three years of age and older, 1953 and 1994 (excluding North and East in 1994)

Zero copula by individual speakers (This data does not include the count for am)

Are absence by type of complement

Zero copula usage by type of complement in AAVE, Creoles, White American Vernacular English, and New Englishes

BE absence by type of complement

Form zero by preceding phonological environment

BE variation by preceding phonological environment

Zero copula by subject NP type

BE variation by type of subject

Is absence by following grammatical environment