SETTINGS THAT CURRENTLY FOSTER CONTACT BETWEEN LSM AND ASL

Cities of the southwestern United States that lie along the border with Mexico are fertile areas for the study of language contact, and the most common examples of contact in these areas involve Spanish and English. However, these cities also contain Deaf1

The capitalized “Deaf” will be used to refer to an individual as part of the Deaf community and culture. This is contrasted with the lowercase “deaf” to refer only to one's audiological status.

Mexican Sign Language, or LSM, has also referred to by various other titles such as el Lenguaje de Señas Mexicanas, el Lenguaje de Señas Mexicano, and el Lenguaje de Signos Mexicano. Many Deaf people in Mexico simply refer to Mexican Sign Language as SEÑA ESPAÑOL ‘Spanish sign’.

A substantial number of Deaf Mexicans have immigrated to the United States and settled in border towns and beyond; many of these people are in search of employment and/or educational opportunities for their children. Social services for Deaf people in Mexico are not widespread, although there does exist some accommodation for communication (e.g., Spanish–LSM interpreting services), primarily in larger cities such as state capitals. Unfortunately, the number of skilled sign language interpreters appears to be small, and often payment for their services must come from the deaf people themselves, a “patron” who wishes to support the services, or a combination of the two. There also appears to be limited availability of educational programs catering to deaf children who live in rural areas, and schools that do exist in larger cities primarily offer programs for deaf children up to the fifth-grade level. Perhaps as a result of these issues and others, there are various examples of individuals, couples, and even families who have moved north of the border, and this has created settings that foster contact between LSM and ASL.

Early evidence for the existence of Mexican Deaf in the United States came from social service agencies along some parts of the U.S.–Mexico border that provide services to Deaf individuals. For example, agencies that contract interpretation services for Deaf individuals in El Paso and cities of the southern Texas Valley3

The larger cities that comprise the southern Texas valley are Brownsville, San Benito, Harlingen, Weslaco, San Juan, Pharr, McAllen, and Edinburg.

It seems that most of the everyday users of LSM who currently reside in the United States were born in Mexico, and they hail from various parts of the Republic. In 2001, two social service agencies that provided services to Deaf individuals in El Paso and the Texas Valley estimated that Mexican Deaf living in each of these border areas ranged from 50 to approximately 150, which was perhaps 10% or less of the Deaf signing population in those areas at that time. Of course, numbers such as these fluctuate regularly based on the return to Mexico of some and the new arrival of others. While there are Mexican Deaf individuals who cross the border regularly (some on a daily basis) but who live in Mexico, there also exist families comprised mostly (or entirely) of Deaf individuals from Mexico who live in U.S. border towns. These Deaf families often interact with other Deaf from Mexico who have moved north of the border. For example, in one city of the Texas Valley, several Mexican families, comprised mostly of Deaf parents with Deaf children and/or hearing children, live in one mobile home park. This allows them to interact frequently with one another. Additionally, Mexican Deaf interact with American Deaf in these border towns at community gatherings such as events planned by social service providers, religious settings, and gatherings at people's homes.

The Deaf people of these border areas, including those from Mexico and the United States, possess a wide range of abilities in the two most common signed languages (LSM and ASL) and the two most common spoken/written languages (Spanish and English) of the area. Regarding signed language, some are mostly monolingual signers of ASL or LSM, others are bilingual signers of both languages (with various levels of proficiency), and others, such as those from rural areas of Mexico who received little exposure to LSM throughout their early years, use home sign systems or gestures in addition to elements of LSM and ASL for communication. In many cases, hearing or Deaf users of ASL learn some LSM signs in order to communicate with Deaf individuals from Mexico, but it appears more generally that the Mexican Deaf learn ASL in order to communicate with ASL signers.4

All of these characteristics of language use may not necessarily be true in Mexican border towns. Anecdotal accounts of the language use of Mexican Deaf in some Mexican border towns suggest that ASL is used only minimally on the Mexican side of the border. Thus, if an American Deaf individual would travel to a Mexican border town, she would likely encounter much more LSM than ASL. However, there are also anecdotal accounts that ASL is used by many Mexican Deaf who live in Tijuana, a Mexican border town near San Diego, California. Gestures and home signs are also used by some Mexican Deaf individuals. The focus of this work is on the language use of Deaf people who reside on the U.S. side of the border.

In the 1970s, English-based sign systems were developed for educational purposes. These systems are not natural languages, but they do use various elements of ASL to represent English visually. See Supalla & McKee 2002 for a discussion of the inappropriateness of these systems for Deaf education in the United States.

In terms of spoken/written language, Mexican Deaf possess various degrees of proficiency in Spanish, and some have English skills as well. U.S. Deaf who live along the border might also have some proficiency in Spanish – often influenced by family members who may be a part of Latino culture and/or by exposure to the language, both written and spoken, in various ways (e.g., television, advertisements, and interaction with hearing Latinos).

The existence of the frequent use of all of these languages along the border was confirmed by a survey that was administered in 1999 to state-certified interpreters for the Deaf in Texas.6

The survey was administered by the then Texas Commission for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Hispanic Trilingual Task Force. That state agency is now known as the Texas Department of Assistive and Rehabilitative Services, Office for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Services (DARS-DHHS). The Trilingual Task Force has been in existence since around 1994 and has been addressing issues of trilingual or multilingual interpreting in Texas. Currently, DARS-DHHS is working with the University of Arizona's National Center on Interpretation in order to develop a trilingual (English-Spanish-ASL) test to assess the skills of interpreters who work in these situations. LSM is not included in the current test development project.

“Mouthing” refers to the mouth configurations and lip movements that signal the voiceless articulation of words from a spoken language. These articulations usually occur simultaneously with a sign that is a semantic equivalent to the mouthed word. This phenomenon is discussed in more detail later in this work. Fingerspelling in LSM or ASL is the articulation of sequences of handshapes (and, at times, movements) with one hand that represent the letters of written language words.

In sum, Mexican Deaf are living in U.S. border towns and are learning ASL and interacting with U.S. Deaf. This has set the stage for contact between two signed languages, although elements of the spoken/written languages also make their way into the sign production of the signers. The next section summarizes some of the structural effects of contact of this nature.

STRUCTURAL EFFECTS OF CONTACT WITHIN THE SIGNED MODALITY

Throughout various works, Lucas & Valli 1989, 1991, 1992 suggest several possible structural (i.e., linguistic) outcomes of contact between two signed languages. Their major categories are the following: lexical influence from one language on the other (e.g., borrowing, loan blends, nonce borrowing, and loan shifts/translation), foreigner talk, interference, and the creation of pidgins, creoles, and mixed systems. The authors caution that it would be difficult to determine the difference between an instance of lexical borrowing and code-switching (or code-mixing) in signed languages. The issue is that borrowings, in spoken-language work, have been traditionally characterized by phonological integration of the borrowed word into the phonology of the other language, but this integration may not be as evident in signed languages because, the authors note, signed language phonologies share many basic components with one another. Thus, in an environment in which two signed languages are frequently used, it might be difficult to determine definitively, in some instances, which phonology (e.g., that of Language A or Language B) the signer may be accessing.

Examples of interference in the signed modality may be evident at various levels of language structure, but the focus here is on the phonological parameters of sign formation. Lucas & Valli (1992:35) refer to this type of interference: “It might be precisely the lack of phonological integration that might signal interference – for example, the involuntary use of a handshape, location, palm orientation, movement, or facial expression from one sign language in the discourse of the other.”

Languages (varieties) A & B: influence (interference) from one on the production of the other

Language interference, as defined by Lehiste (1988:1–2), constitutes the “deviations from the norms of either language that occur in the speech of bilinguals as a result of their familiarity with more than one language.” Such deviations have been described as involuntary. As noted above, interference can occur at various levels of language structure, such as the phonological, lexical, and syntactic levels (Grosjean 1989, Lehiste 1988). For example, two languages that are in contact may have a phoneme that is defined similarly across the languages, but their phonetic realizations of that phoneme may be different. Thus, in a contact situation, the pronunciation of a word that contains that phoneme may be influenced by the phonetic realization of the phoneme from the other language. Lehiste explains that this type of interference is often referred to as sound substitution.8

In this work, “interference” is described from a language-production perspective. Studies (e.g., Cesar-Lee 1999) that address the perception of deviant productions are necessary to determine the extent to which interlocutors would claim that such interference causes a “foreign accent” in signed language.

the phoneme /t/ is found in Slavic languages as well as in English, but in Slavic languages /t/ is normally dental (articulated with the tip of the tongue against the inner surface of the upper front teeth), whereas in English /t/ is normally alveolar (articulated with the tip of the tongue against the alveolar ridge). In Slavic languages the phoneme /r/ is realized as a tongue-tip trill, whereas in American English /r/ is a retroflex continuant.

This means that a person who natively speaks a Slavic language and who acquired English as an adult may systematically pronounce instances of /t/ in English words as dental consonants rather than alveolar consonants. Likewise, instantiations of /r/ for a native speaker of a Slavic language who learns English as an adult may tend to surface as tongue-tip trills instead of retroflex continuants.

Some authors may distinguish between different types of interference. For example, Grosjean (1989:9) suggests:

[i]nterferences can be of two kinds: static interferences which reflect permanent traces of one language on the other (such as “foreign accent”), and the dynamic interferences, which are the ephemeral and accidental intrusions of the other language (as is the case of the accidental slip on the stress pattern of a word due to the stress rules of the other language, or the mo[m]entary use of a syntactic structure taken from the language not being spoken). These latter interferences occur more or less randomly whereas the first type are systematic.

Exploring the effects of language interference between very different, albeit historically related languages such as English and various Slavic languages, as in the example from Lehiste 1988, may be quite different from determining what occurs with two languages that are more closely related. Portuguese and Spanish, both Romance languages, provide the linguistic content from which to investigate interference between closely related languages; and the border between Uruguay and Brazil in South America provides the context for the study of such contact. A description of various contact phenomena that were demonstrated by speakers of Portuguese and Spanish along that border can be found in Hensey 1993. As part of the data, he describes instances of phonological interference from Portuguese in the Spanish spoken by schoolchildren. In particular, the children reduced standard Spanish diphthongs to monophthongs and articulated standard Spanish simple vowels as diphthongs. In essence, features from one language were found in articulations of the other language.

One way in which interference might manifest itself in two sign languages: Descriptions of phonemes in signed language

In groundbreaking works on the sublexical structure of American Sign Language (ASL), William Stokoe and colleagues (Stokoe 1960, Stokoe et al. 1965) identified three independent phonological parameters of sign formation: hand configuration, place of articulation, and movement. Later, palm orientation was added to the list (Battison 1974). Every sign in a sign language can be described according to these parameters, and values of parameters (e.g., specific handshapes or places of articulation) may differ across sign languages. The parameters have also been shown to parallel some of the phonological features of spoken languages. For example, minimal pairs based on changing the value of a single parameter can be described (e.g., see Klima & Bellugi 1979), and each parameter can be considered to be psychologically real based on evidence from production errors referred to commonly as “slips of the hand” (see Klima & Bellugi 1979 for ASL; Hohenberger et al. 2002 for German Sign Language). Other works (e.g., Brentari 2001, Liddell & Johnson 1989) have provided models of the phonological structure of ASL.

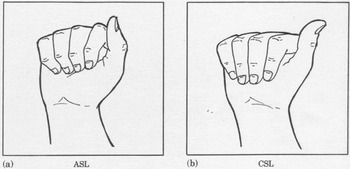

Allophones of /A/ in ASL (adapted from Klima & Bellugi 1979:44). Reprinted by permission of the publisher from The signs of language by Edward Klima and Ursula Bellugi, pp. 44, 161, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, copyright ©1979 by the President of the Fellows of Harvard College.

In a foundational volume about the linguistic structure of ASL, Klima & Bellugi 1979 discussed various handshape phonemes, which they termed “Hand Configuration primes,” for ASL. For instance, /A/ was identified as a phoneme of the language, and allophones (which they termed “subprimes”) could be

as in the sign TOMORROW, [AS] as in the sign TO-FIGHT, and [AT] as in the initialized sign TEAM.

The closed fist handshape (a) in ASL and (b) Chinese Sign Language [CSL] (adapted from Klima & Bellugi 1979:161) Reprinted by permission of the publisher from The signs of language by Edward Klima and Ursula Bellugi, pp. 44, 161, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, copyright ©1979 by the President of the Fellows of Harvard College.

In the same book, Klima & Bellugi included a chapter devoted to the comparison of various signs from Chinese Sign Language (CSL) and ASL. In particular, they noted similarities between the CSL and ASL closed fist handshape (mentioned above as /A/) in signs that appear to be similarly articulated between the two languages but that have different meanings. For example, they described how the ASL sign SECRET and the CSL sign FATHER appear to be articulated in the same way. However, they also explain subtle differences of articulation of the handshapes for those signs in CSL versus ASL.

According to the authors, the ASL variant can be characterized as “relaxed, with fingers loosely curved as they close against the palm” (1979:161) and with contact between the two fingers at the index finger's first joint and the entire back of the thumb; this leaves only the tip of the thumb protruding above the line made by the bent knuckles. By comparison, the CSL handshape displays fingers that are rigid, not curved, and folded over further onto the palm. Also, contact between the index finger and thumb is such that the thumb protrudes upward more prominently than in the ASL shape. As these descriptions suggest, there are subtle differences between these two handshapes though they may appear at first sight to be the same.

Where to look for interference in sign: Some differences between LSM & ASL

LSM and ASL are similar in some ways, and this is perhaps due in part to their ties to French Sign Language of the 1800s (hereafter referred to as Old LSF; Old Langue des Signes Française), yet they are distinct languages (Faurot et al. 1999). The history of LSM and of the Deaf community in Mexico can be traced to the arrival of a Deaf Frenchman, Edouard Huet, in Mexico City in the mid to late 1860s. Upon his arrival, Huet established a school for deaf children in Mexico City (Guerra Currie 1999). Huet was presumably fluent in French Sign Language of the 1800s, so it is commonly believed that the development of LSM was influenced by Old LSF, creating a historical link between the two languages. ASL can also be linked to Old LSF, but by contact via another Deaf Frenchman, Laurent Clerc, who arrived in the United States in 1816. The development of ASL was likely also influenced by indigenous signed languages that existed before the arrival of Gallaudet (Fischer 1975, Groce 1985, Woodward 1978). It is not known if the development of LSM was influenced by indigenous signed language(s) that existed in Mexico before the arrival of Huet. However, there are current accounts of at least one other indigenous sign language in Mexico, Maya Sign Language (Johnson 1991), which is reported to be widespread throughout villages in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico and may reach into areas of Guatemala.

If the account of the development of LSM in Mexico is similar to that for ASL in the United States, one might suggest that the school for the Deaf in Mexico City had great influence on the beginnings of LSM. Early and later contact with home-signers throughout the country, as well as possible contact with speakers of other sign languages, likely created the LSM of the twenty-first century. Modern LSM is reported to be a single language that is used throughout Mexico (Bickford 1991, Smith-Stark 1986), especially in urban areas, although there is variation based on various factors. Bickford 1991 suggests that age is the most significant factor in dialectal variation in LSM, and most of the variation appears at the phonological rather than the lexical level. Guerra Currie 1999 proposes that phonological variation in LSM signs is more common within the handshape and movement parameters of sign articulation, whereas the place of articulation parameter is relatively stable and less prone to dialectal influence. Faurot et al. 1999 suggest that religious differences between signers (e.g., Catholic versus Protestant), levels of education, and geographical distribution of signers also account for variation in the language.

Mexican Deaf are exposed to LSM in various places: in religious settings, at community gatherings, at school, or from Deaf acquaintances who have interacted with others in the language. In cities where LSM can be found at a school for the Deaf (even if a school follows an oral philosophy of Deaf education, students are sometimes exposed to LSM outside the classroom), the school likely provides an important venue for the acquisition of LSM. Additionally, many Deaf children in Mexico benefit from interaction with an older, more experienced signer who serves as an LSM model and someone who can demonstrate Deaf cultural values as well (Ramsey & Ruiz Bedolla 2006). Some Mexican Deaf travel throughout the country and interact with other Mexican Deaf through their participation in Deaf sports tournaments. Yet other Mexican deaf individuals do not have the benefit of interacting with LSM users and therefore find themselves without the signed language skills to interact with other LSM users in an efficient manner.

As briefly mentioned earlier, LSM and ASL have been described anecdotally and via linguistic writings as mutually unintelligible (Faurot et al. 1999, Guerra Currie 1999) despite the fact that many signs look alike or are articulated similarly (i.e., they share some or all of the articulation values for the phonological parameters of handshape, place, movement, and orientation). For instance, the LSM sign AYUDAR ‘help’ (Figure 3a) and the ASL sign HELP (Figure 3b) seem to share the same values for all phonological parameters.

FIGURE 3a: The LSM sign AYUDAR ‘help’. Reprinted with permission of the illustrator and author, Victor Palma.

FIGURE 3b: The ASL sign HELP. From Humphries and Padden Learning American Sign Language, 2/e, published by Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA. Copyright ©2004 by Pearson Education. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Others have described signs that share the same values for at least two of the phonological parameters as similarly articulated signs (Guerra Currie 1999, Guerra Currie et al. 2002, McKee & Kennedy 2000).9

Bickford 1991 also performed analyses on signs between LSM and ASL that are articulated similarly, although his analysis seems to have allowed for categorization of such signs with one or two possible phonological differences.

LSM-ASL similarly articulated but semantically unrelated (SASU) signs are discussed in Quinto-Pozos 2002.

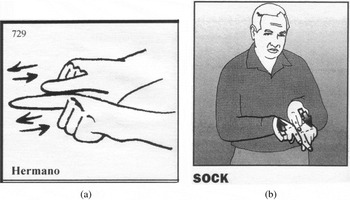

FIGURE 4a: The LSM sign HERMANO ‘brother’. Reprinted with permission of the illustrator and author, Victor Palma.

FIGURE 4b: The ASL sign SOCK. From Humphries and Padden Learning American Sign Language, 2/e, published by Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA. Copyright ©2004 by Pearson Education. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Despite the perceived similarities between the languages, there are ways in which they differ from each other. Those ways would be logical areas to look for “interference” or an “accent” in signed language. In LSM and ASL we might want to look where the languages are phonetically similar but differ in perceivable or measurable ways. Alternatively, the lens could be focused on where the languages utilize a similar structure that is articulated differently across the two languages. Such areas of structural similarity but articulatory difference between LSM and ASL are the sources of the data presented in this article. Specifically, the focus will be on select LSM and ASL handshapes, non-manual signals, and the “mouthings” (voiceless articulation of spoken language words) that can accompany sign production.

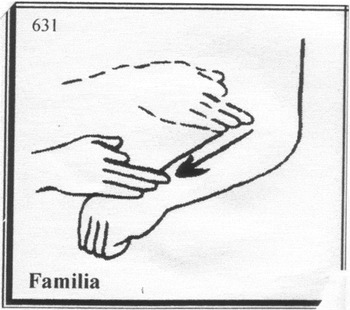

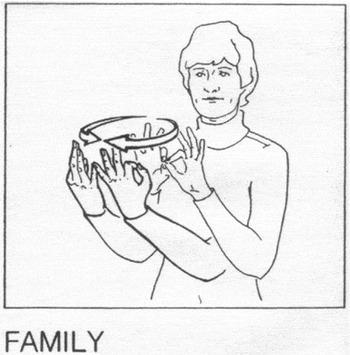

Handshape

LSM and ASL both utilize a handshape that is commonly referred to as an “F-handshape,” which may have come about because some signs in each of those languages refer to items that begin with the letter “f” in the spoken versions of the language. For instance, the LSM sign FAMILIA (Figure 5) is formed with an LSM F-hs, and the ASL sign FAMILY (Figure 6) is articulated with an ASL F-hs. Such signs have been commonly referred to as “initialized signs.”

The LSM sign FAMILIA ‘family’. Reprinted with permission of the illustrator and author, Victor Palma.

The ASL sign FAMILY. From A Basic Course in American Sign Language, published by TJ Publishers, Carrollton, TX. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

In Figures 7 and 8 the handshapes used in these signs are shown more clearly. Note that LSM F is similar to modern-day ASL F, but there are two apparent differences: (i) the contact point between the index finger and the thumb, and (ii) the amount of spread (i.e., space) between the middle, ring, and pinky fingers. Following the Prosodic model of ASL phonology (Brentari 2001), the index finger and the thumb in these handshapes would be referred to as “selected fingers,” and the middle, ring, and pinky fingers would be labeled as “non-selected fingers.” In Figure 8, one can see that, in ASL F, the tips of the index finger and thumb (i.e., the selected fingers) contact each other and the three extended fingers (i.e., the non-selected fingers) are spread apart.11

An older version of ASL F-hs has been reported in at least a couple of early works on ASL. Woodward 1976, in sketches of ASL and French Sign Language handshapes, identifies an “old” variant of ASL F-hs with similar thumb and index-finger contact to that of LSM F-hs, although the reported spread of the fingers in that older version seems to be similar to that of the current ASL F-hs. Additionally, the ASL F-hs that is pictured in the manual alphabet chart given in Stokoe 1960 and Stokoe et al. 1965 is similar to modern-day LSM F-hs in both features discussed here.

In Quinto-Pozos 2002, it was suggested that the three extended fingers in LSM F were in a similar configuration to ASL F, but further investigation has shown that that is not true in all cases. One possible reason is that there may exist allophonic variation in some LSM signs between LSM F-hs with spread non-selected fingers and LSM F-hs with non-spread non-selected fingers. Additionally, some informants suggest that the ASL F-hs is used in some LSM classifier constructions.

LSM F-hs.

ASL F-hs.

Non-manual signals

Another difference between LSM and ASL, according to Eatough 2000, is in the articulation of non-manual signals (NMS) used in the two languages for questions. It is commonly known that in ASL furrowed brows are obligatory markers of root wh-questions and raised eyebrows mark yes/no questions (Bahan 1996, Baker-Shenk 1983, Liddell 1980), whereas Eatough found that in LSM a backward head tilt is used for both yes/no and content questions. Quinto 1999 also reported that LSM utilizes a backward head tilt for the non-manual marking of content questions.13

One reviewer commented that backward head tilts may occur in some question signs in ASL, even though they may not be obligatory. I thank that anonymous reviewer for pointing this out. In most cases, however, the backward head tilt is an obligatory NMS with LSM content questions whereas the furrowed brows are obligatory markers of ASL content questions. There may be other NMS (e.g., a shoulder shrug) that also accompany content question constructions in LSM.

Differences in mouthing

Studies of contact between a signed language and a spoken language have shown that one feature of such contact can be described as the mouth configurations that signal the voiceless articulation of words; these mouth configurations occur simultaneously with the production of signs. Several authors have addressed this phenomenon, which is widely referred to as “mouthing,” with data from ASL and English (Davis 1989, 1990a, 1990b; Lucas & Valli 1992), Swiss German Sign Language and German (Boyes Braem 2001), British Sign Language and English (Sutton-Spence & Day 2001), among others (Boyes Braem & Sutton-Spence 2001). Boyes Braem and Sutton-Spence (2001:2) note, “Mouthings are mouth patterns derived from the spoken language.” They are, of course, referring to the ambient spoken language with which a signed language is frequently in contact. In most cases, the mouthed element is a spoken-language word that is a semantic equivalent to the sign being produced. For instance, Deaf signers in the United States sometimes mouth English words while producing ASL signs, whereas Deaf signers in Mexico sometimes mouth Spanish words while producing LSM signs. In some cases, the mouthed element is a reduced form, articulatorily speaking, of the spoken language equivalent (e.g., see Hohenberger & Happ 2001, Vogt-Svendsen 2001). There are also instances where the mouthed element has become obligatory (i.e., lexicalized) and is a concomitant part of the sign (Davis 1989, 1990a, 1990b; Sutton-Spence & Day 2001). In more recent writings, mouthing has been claimed to fulfill semantic and prosodic roles in signed languages (Sandler & Lillo-Martin 2006).14

Recent studies have explored another facet of contact between English and ASL in a phenomenon referred to as “code-blending,” the simultaneously signed and spoken utterances of bimodal bilinguals, with a focus on the hearing children of Deaf signing adults who are native users of signed and spoken languages (Emmorey et al. 2003, Bishop 2006). Among other claims, the authors of these studies report that code-blends seem to differ from simultaneous communication, or SimCom, in various ways.

DATA COLLECTION METHODOLOGY

The language production data that are presented here are from six one-on-one interviews and two group discussions that contained four people each. In particular, the group discussions were intended to mirror the types of interactions (including the varied linguistic profiles of the participants and the content matter discussed) that take place in border areas where contact between LSM and ASL is common. Identical data collection procedures were followed with two different sets of four participants at two sites (El Paso and a location in the southern Texas Valley). At each site, interviews and group discussions were led by a Deaf bilingual (LSM-ASL) signer. In addition, at least one other bilingual signer and two largely monolingual signers – one whose primary language is ASL and the other whose primary language is LSM – also participated. A complete and detailed description of the data collection methodology, including the coding of the collected data, can be found in Quinto-Pozos 2002.

Participants

Participants resided in the area in which those particular data were collected. In particular, the El Paso participants lived in El Paso, while each of the Texas Valley participants lived in one of the south Texas valley cities (see note 3). Seven of the eight participants self-identified as Deaf, whereas one labeled himself “hard of hearing.” There was no literacy requirement for inclusion in this study nor was there a requirement regarding length of time in which a participant had lived in either of the areas in which the data were collected. In most cases, the participants at each site knew each other and had interacted previously. Also, in each set of participants there were Deaf parents who have Deaf children; those children attend public school in the United States

There were, however, language considerations for the selection of participants. As mentioned above, there were bilingual and mostly monolingual signers in each set of participants. At each site, a Deaf interviewer was chosen based on a high level of fluency in both LSM and ASL, an ability to communicate with monolingual signers of either language, and frequent interaction with members of the Deaf community. In both cases, the interviewer was recognized by other members of the Deaf community as someone who was very competent in both LSM and ASL. The other bilingual participant for each site and the two monolinguals were chosen based on their own claims about language use as well as suggestions from other Deaf members of their communities. Thus, other Deaf individuals who did not participate in this study helped to identify who was monolingual and who was bilingual.

Tables 1 and 2 minimally describe the participants for both data collection sites. More thorough descriptions of each participant are provided in Quinto-Pozos 2002, which also provides details about the participant responses to the interview questions. Note that TV3 was born in Guatemala, but he also reported having lived in various Mexican cities (Oaxaca, Mexico City, and Guadalajara), which provided him access to LSM. Even though he was born in Guatemala, he did not report knowing any sign language that is used in that country.

El Paso (EP) participants.

Texas Valley (TV) participants.

Information about the author of this work is also important in order for the reader to gain a perspective about how he is situated in relation to the community being studied. I am a hearing signer of ASL (advanced fluency) and LSM (intermediate fluency) who is not from a border community, but I did grow up in a community in the southwestern United States in which contact between English and Spanish was prevalent. I studied ASL and sign language interpretation as an undergraduate in college and am a nationally certified ASL–English interpreter. I had been learning LSM for approximately three years at the time of data collection. I had initially been exposed to LSM at a one-week intensive course taught by a native LSM signer, but further skills had been gained by multiple trips to Mexico during graduate school. One of those trips included data collection for a study on basic word order in LSM (as reported in Quinto 1999).

Procedures for language elicitation and data coding

The data collection at each site consisted of questions that were asked by the bilingual Deaf interviewer in two settings: one-on-one interviews and group discussions. The one-on-one interviews were designed to gather information about personal history (e.g., basic demographic information, movement history, educational experiences, and occupation) and language use (including self-reported fluency and use) of each participant. The group sessions, on the other hand, were designed to mirror similar situations of LSM–ASL contact along the U.S.–Mexico border, where bilinguals of various degrees and monolinguals interact. The discussion questions were aimed at comparing the participants' perceptions of various aspects of life in Mexico and in the United States, which were designed to encourage casual and comfortable group conversation about various topics. With these questions as a guide, the Deaf interviewer asked the participants to compare such aspects of life as common foods, types of candy, and clothing, along with prices of those items, transportation systems, and holiday and birthday traditions. This design was implemented in hopes of mitigating the “observer's paradox” that many researchers have tried to avoid while collecting naturalistic data. In order to create as natural an environment as possible, everyday concerns about which most people would have already formed opinions were the focus of the conversations. Additionally, at both data collection sites, members of the Deaf communities from those areas were recruited in the hope that their familiarity with one another would allow them to interact naturally without drastically changing their language production in response to being videotaped. Finally, data collection venues that the Deaf participants were familiar with were used, which perhaps allowed them to be more comfortable during the videotaping process. The effects on participants' responses of the necessary use of a video camera to capture language production is a common concern in signed language research, and every effort to mitigate such effects is necessary.

The one-on-one interview portion of the study occurred first at each location, and this portion was followed by a group discussion with all four participants. Prior to the interviews, the investigator explained the interview questions to the Deaf interviewer, including the details that he or she would be interviewing three other participants – one at a time. A Deaf interviewer was selected so that the participants would not necessarily change their signing style to accommodate the investigator's signing skills as a hearing non-native signer of ASL and LSM. The investigator also explained that he would be sitting in the corner of the room behind the participant being interviewed in order to sign each question to the interviewer. This method was utilized in order to minimize any potential influence from written English or Spanish on the way in which the interviewers would frame the questions to their interlocutor(s). The interviewer would, after watching the investigator, sign the question to the interviewee. The interviewer was instructed to use whatever language production – ASL, LSM, or gestures – that he or she felt necessary to conduct the interview with each participant.

The group discussion session at each site was conducted upon completion of the three interviews. For this portion of the data collection, all participants sat facing each other in a circle. These sessions were recorded using two cameras in order to capture the language production of all four participants. As with the interview data collection, the investigator signed questions to the interviewer that he or she, in turn, would pose to the group. After other participants had responded and group discussion had ensued about a question, the interviewer at each site would often participate by answering the question as well. Frequently, another participant would direct a question back at the interviewer. Thus, all participants had an opportunity to answer the questions and give their opinions.

A total of 64 minutes of the language data was coded (28 minutes of group discussions and 36 minutes of one-on-one interviews). The coding involved identification of each meaningful element (e.g., sign of either language, instance of fingerspelling, deictic point, classifier, nonlinguistic gesture) and the recording of various phonological features of signs.15

The analysis was not focused on units below the sign/word level (e.g., bound morphemes), but rather on elements that could stand alone semantically.

DATA PRESENTATION AND DISCUSSION

Phonological interference: Handshape examples

The following presentation and discussion of data from this study includes examples of participants articulating signs with hand configurations that differ – albeit minimally in some cases – from the usual hand configuration used in those signs.16

This work focuses on phonological interference as seen in the hand configurations of LSM F and ASL F. Quinto-Pozos 2002 also touches upon possible instances of interference based on the thumb extension in LSM G and LSM H versus the usual lack of such thumb extension in ASL G and ASL H.

In several instances, participants utilized part of the configuration of an LSM F-hs to articulate an ASL sign, or used an ASL F-hs to articulate an LSM sign. This was done by at least five of the eight participants in this study. Two features of the LSM-F and ASL-F handshapes must be discussed as they appear in the data: the contact between the thumb and index finger (i.e., contact between the selected fingers), and the amount of spread between the middle finger, ring finger, and pinky (i.e., amount of spread in the non-selected fingers). The following examples focus on the use of the ASL sign FAMILY within the group discussion data.

One bilingual signer (EP1) who was born and raised in Mexico consistently produced both phonetic features (selected finger contact and non-selected finger spread) of an LSM F-hs in an ASL sign that normally calls for the use of the ASL F-hs. The example in (1) illustrates this phenomenon with the ASL sign FAMILY, although EP1 also produced a similar articulation with the ASL sign FRIDAY in an example not provided here. In the examples given here, the signs that contain an unexpected handshape are shown in boldface; transcription conventions can be found in the Appendix.

However, in (2) and (3), two other Mexican-born signers (EP3 was primarily an LSM user while TV2 was a strong bilingual) produced an F-hs with LSM F-hs selected-finger contact and ASL F-hs non-selected-finger spread. These two examples demonstrate a mixing of LSM and ASL handshape features in the ASL sign FAMILY.17

In Quinto-Pozos 2002, these signs were identified as exhibiting LSM F-handshapes because the focus in that analysis was on the contact between the thumb and index finger. This work adds to that analysis by describing differences in contact and also the amount of spread between non-selected fingers.

This is the variant of CHRISTMAS/NAVIDAD that indicates a long beard (as if referring to the beard of Santa Claus). This is not the variant that is initialized in ASL with a C-hs or in LSM with an N-hs. Those two variants are articulated in different locations and with different movements.

In examples (1), (2), and (3), the participants articulated the ASL sign FAMILY with all or some features of LSM F-hs rather than all features of the ASL F-hs. Note that the other signs in these segments are either signs that are articulated similarly across the two languages or signs unique to ASL. Thus, it is not the case that the participants produced LSM F-hand configurations in these ASL signs because there were only signs unique to LSM produced shortly before or after the sign FAMILY that might have influenced the signer to use an LSM hand configuration.

Yet it may also be that the linguistic environment of a form could influence what a signer produces. In (4), EP3, the same Mexican-born signer who produced ASL FAMILY with ASL non-selected finger spread in (2), displays the LSM F-hs feature of spread (“-spread”) for the non-selected fingers in the ASL sign FAMILY.

In (4), EP3 is commenting on how her family is comprised of many hearing members and, in the context of the conversation, that has an effect on how people interact and what is done on special occasions. As far as the phonetic description is concerned, she articulates the ASL sign FAMILY with non-selected fingers that appear most like the LSM F-hs, even though she does not seem to produce it in that fashion in most of the other instances of her articulation of F-handshapes in ASL signs. However, note that the following sign is the LSM sign FAMILIA, which may have influenced the articulation in the sign immediately preceding it. In FAMILIA, the spread of the non-selected fingers seems to be that of the LSM F-hs. Thus, this code-switching from a sign in one language to a sign in the other may also exemplify the anticipation of a feature of the following handshape: the non-selected fingers.

Below is an example of a participant producing the selected finger contact of ASL F-hs with an LSM sign, which is the reverse of EP1, a native signer of LSM, as exemplified in (1). Specifically, TV1, a bilingual who signed ASL before learning LSM, signed FEBRERO ‘February’ in (5) with the contact of ASL F-hs, although the spread of her non-selected fingers seemed closer to those of LSM F-hs rather than ASL F-hs.

Note that the interviewer in (5) is repeating signs that another participant just produced. TV2 articulated an LSM F-hs with both features of that handshape, whereas TV1 articulated the same handshape with ASL phonetic features.

Some participants exhibited tendencies in their articulations of the ASL-F and LSM-F handshape, while others were more variable. However, because of the naturalistic character of the data (i.e., specific lexical items were not elicited by the investigator), some participants produced a lexical item several times while others did not produce the same item at all. Data of this sort make it difficult to perform inter-participant comparisons with regard to frequency of specific details of language production.

Despite limitations that do not allow for robust inter-participant comparisons, a few trends from the F-hs data were evident. First, of the eight signers from the two locations who participated in the data collection sessions, three of them (EP1, EP2, EP4) consistently produced F-handshapes that most closely matched the F-handshape of their first signed language (LSM, ASL, and ASL respectively) in both phonetic features. This type of interference could be described as static or systematic interference, which has been defined as interference that reflects “permanent traces of one language on the other such as a ‘foreign accent’” (Grosjean 1989:9).

In contrast, four of the participants (EP3, TV1, TV2, and TV4) produced handshapes with phonetic features of both handshapes, and no discernible patterns have been found in the data with regard to the articulation of the F-hs. One of these participants (TV1) was raised in the United States and had access to ASL as her primary signed language through her early years. She went on to become a fluent user of LSM and appears currently to have contact with LSM signers on a regular basis. TV1 has also traveled to Mexico many times and has years of experience with LSM. EP3, TV2 and TV4 were all born in Mexico but have moved to the United States. TV2 and TV4 learned ASL and interact with the American Deaf community on what appears to be a regular basis. EP3 reported to have first been exposed to ASL via a Deaf friend in Ciudad Juarez, just across the border from El Paso. She also noted that she did not have any education as a child, so presumably the lack of exposure to LSM or ASL until later in life may have influenced her variable use of some of the characteristics of the F-hs in both languages. It may be that any interference produced by these four participants could be characterized as dynamic interference, which is more random in nature and has been defined as “the ephemeral and accidental intrusions of the other language” (Grosjean 1989:9). As reported in the discussion of example (4), the linguistic context of a sign might also influence the articulation of the previous sign and cause what may appear to be interference from the other language. It should be noted that one participant (TV3) did not produce the lexical items that would allow for the investigation of interference between LSM F-hs and ASL F-hs in his signing.

Interference with non-manual signals

In the data from this study, there are several instances of the articulation of a content question sign from one language with the non-manual signal(s) (NMS) from the other language. For instance, in the Texas Valley group discussion, TV4 produced the phrase given in (6) during a conversation about family Christmas traditions in Mexico versus those in the United States.

In (6), TV4, a native of Mexico who signed LSM before learning ASL, did not furrow his brows at any time, but rather articulated the LSM content question NMS (a backward head tilt, “bht”) while producing ASL signs. In fact, TV4 leaned his torso toward TV1 while asking the question, but his backward head tilt continued for the duration of the phrase. This is an example of the production of an ASL sign with a NMS from LSM, whereas the reverse also occurred in the data. An example is given in (7) below, in which TV1 articulated the LSM sign CUÁNDO ‘when’ twice within a phrase of other LSM signs.

In the case of the phrase in (7), TV1, the bilingual signer who was raised in the United States, furrowed her brows (indicated in the transcription with a line and the lowercase “fb”), which is the ASL NMS for content questions, during the two instances of signing the LSM sign CUÁNDO ‘when’ followed by a deictic point.

Because the production of a backward head tilt and furrowed brows involves different and independent muscles of the face and neck, one could posit that both of these articulations could take place simultaneously. This occurs in at least one production of the LSM sign QUÉ by TV1. In this example, TV1 has asked TV2 about her favorite food. TV2 responds with the question: ‘Do you mean favorite Mexican food or favorite American food?’ TV1's response is given in (8).

The onset of the backward head tilt (bht) and the furrowed brows (fb) in (8) occurs before the LSM sign QUÉ. Specifically, those non-manual signals co-occur with a gesture that has been labeled “come-on” and continue as the signer points to TV2 and then signs QUÉ. The gesture “come-on,” in this case, is produced in neutral space with the hand configuration of ONE/UNO, the palm facing the signer, and hand-internal movement of the index finger toward and away from the signer. Despite the simultaneous articulation of wh-question NMS from both LSM and ASL, the interlocutor (in this case, TV2) seems to understand TV1 perfectly; TV2 does not hesitate with her response. In fact, this was also the case with the mixing of NMS from one language with signs from the other as presented in (6) and (7).

Interference with mouthing

There were various examples of mouthing in the data. Many of the examples followed patterns of mouthing that are expected with LSM and ASL: mouthing some English words while signing ASL, and mouthing some Spanish words while signing LSM. As noted earlier in this article, this type of mouthing is an expected outcome of contact between a signed and a spoken language. However, in addition to the expected type of mouthing, participants also provided examples of mouthing an English word while producing an LSM sign, a Spanish word while producing an ASL sign, or an English or Spanish word while producing an LSM-ASL similarly articulated sign. EP3 provided several examples of the production of an ASL sign with the simultaneous mouthing of a Spanish word, and two of those examples are provided in (9) and (10).

In (9), the Spanish word mamá ‘mother’ was mouthed while EP3 signed the ASL sign MOTHER. One could claim that it is possible to confuse the mouthing of mamá with that of mother because both words begin with a bilabial consonant. However, articulation of the low back vowels of mamá encourage a wider opening of the mouth than the centralized vowels for mother, and this fact was used as a clue for determining which mouthed word was likely used in this example. In (10), EP3 mouthed the Spanish word igual ‘same’, while signing the ASL sign SAME during a discussion of prices of the food items in Mexico versus food prices in the United States. Davis 1989, 1990a, 1990b labeled mouthings such as these as examples of “code-mixing” since they involve the simultaneous mixing of elements of one language (the mouthed items) with elements of another (the signed language).

These examples of mouthing are consistent with the results of the signed-language interpreter survey that I presented in the introductory section. In that investigation, 72% of U.S. interpreters who had been in a situation influenced by Spanish and/or LSM claimed that they had seen their clients mouth Spanish words. The degree to which mouthing accompanies sign production is not the focus of this study, but it is clear that mouthing words from a spoken language while simultaneously articulating signs is one characteristic of contact between LSM and ASL.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The data presented in this article reflect examples of interference from the native sign language of the user in the production of forms from a second sign language. That is, in these examples the signers deviated from the articulatory norms of either LSM or ASL and presumably did so because of influence from the language of their childhood. Such deviation may be common in these contact situations, although such a generalization requires the in-depth study of more participants and how they are situated vis-à-vis other language users. Sociolinguistic questions concerning prestige and attitude were not considered in this study, although it seems that one signed variety (ASL) is more prestigious whereas the other (LSM) is less so.

The examples of interference described here could be likened to signers producing particular signs with “foreign accents.” However, such a purported “accent” might not be detected by native signers because of various characteristics of the deviant forms. For example, whereas the focus of this phonological analysis of sign formation has been on handshape, other simultaneous parameters such as movement or place of articulation may also influence the degree to which deviant forms are detected. A handshape difference between two sign languages, especially if it is a subtle articulatory difference such as where the signer's index finger contacts the thumb, may not prove to be very salient if the handshape is moving quickly through space in the production of a sign. With regard to LSM F-hs and ASL F-hs, it is unclear which of the two phonetic features (selected fingers contact and non-selected fingers spread) or which combination of other factors would influence a native signer to notice a difference from her mother-tongue sign language. One could hypothesize that the spread of the non-selected fingers in F-handshapes would be more salient or noticeable to viewers than the location of contact between the selected fingers. Yet this is an empirical question that would need to be investigated using instrumental measures and judgments from native signers.

In the case of LSM F-hs and ASL F-hs, the articulatory differences in these hand configurations may be different phonetic realizations of a single phoneme. Earlier in this work, I discussed Lehiste's 1988 definition of sound substitution, or a “foreign accent,” which is a phenomenon that can result from contact between two languages that have an identically defined phoneme but different phonetic realizations of that phoneme. In some cases of the phenomenon of foreign accent, a speaker will articulate a word from the foreign language with an allophone from her native language. It seems reasonable to presume that the influence of Old LSF on the development of both LSM and ASL could result in the existence of a similar phoneme in the two languages – a phoneme that has different allophonic realizations in the two languages. This suggestion awaits further work of a historical nature to confirm its plausibility.

As mentioned earlier, it is not entirely clear whether or not a specific signer will reliably produce a form from her native language as opposed to the form from the second language. Some signers seemed reliably to articulate a handshape in a certain way, which was presumably the handshape of the language that they used in childhood. However, in the cases of other signers, a mixture of features from the two languages was present in the articulation of the F-hs. Such signers seemed to be mixing features of both languages in their production, and some of these signers also purportedly used only one of the signed languages during childhood. The linguistic behavior of the participants is most likely influenced by the signers with whom they have interacted and by internal factors (e.g., ability to learn a new language, age of exposure to an L2). It should also be noted that, with regard to the articulation of LSM F-hs and ASL F-hs, no participant in this study accurately produced features of his or her non-childhood language with consistency.

It may also be that the LSM F-hs as it is used in parts of Mexico is changing. The change may be based on influence from ASL, language-internal changes, or some other factor. As noted earlier, there is a substantial amount of handshape variation in LSM (Guerra Currie 1999), and such variation might include differences in the articulation of the F-handshape. As a result, one or both features (selected fingers contact or non-selected fingers spread) of ASL F-hs may have become allophonic in LSM and be used in some signs. If so, the use of that allophone of /F/ would be a normal part of LSM. Further work on the phonetic and phonological structure of LSM is required to determine whether this is the case. However, it seems that LSM F-hs is rare in most varieties of modern-day ASL (although a minority of signers, mostly from older generations, may have this variant in their ASL), so its use with ASL signs is clearly marked.

At no time during the data collection did production of forms that exhibit phonological interference cause the participants to suspend their discussions in favor of discussions of the appropriateness or “correctness” of the forms. Rather, conversations among the participants appeared to continue to flow smoothly, and the participants seemed to understand each other during the production of these forms. This suggests that participants may be accustomed to such differences and aware that communication in these contact situations often involves such language mixing.

These cases confirm the suggestion by Lucas & Valli (1992:35) that interference may occur in situations of contact between two signed languages: “It might be precisely the lack of phonological integration that might signal interference – for example, the involuntary use of a hand configuration, location, palm orientation, movement, or facial expression from one sign language in the discourse of another.” Yoel 2001, in her study of the attrition of Russian Sign Language among Russian Deaf immigrants in Israel, also shows that signers substitute phonological parameters from one signed language in the production of signs from the other signed language. In that work, Yoel suggests that phonological interference can occur with all parameters of sign formation (hand configuration, place of articulation, movement, and palm orientation).

It should be noted that contact between sign languages, especially two purported genetically related sign languages such as LSM and ASL, may not result in very obvious structural differences. In the examples of F-hs discussed in this work, we had to look carefully at subtle aspects of articulation in order to examine how contact between fingers and amount of finger spread in the handshape parameter of phonology can perhaps be loci for examining interference from one sign language to another. As described in the discussion above of the two different realizations of the /A/ handshape in ASL and Chinese Sign Language (CSL), what appears to be the same handshape on the surface really is different when one considers various aspects of articulation. Subtle differences between two signed languages may parallel differences between structurally similar spoken languages such as Portuguese and Spanish, as was suggested earlier. Whether or not unrelated sign languages would exhibit types of contact phenomena similar to those observed in LSM and ASL remains to be seen. This is, however, a very interesting theoretical question, since some authors have claimed that unrelated signed languages appear to be more similar to each other than unrelated spoken languages – the result, in large part, of iconicity in signed language (Guerra Currie et al. 2002).

This article also includes descriptions of ways in which mouthing, a phenomenon that signals contact between a sign language and the ambient spoken language in which it is produced, can figure into a language-contact situation between two sign languages if those languages are produced in ambient spoken-language environments that differ between the two countries or locations. In the case of ASL as used in the United States, Lucas & Valli 1992 have noted that such mouthing is a common feature of the contact, and such mouthing may signal the use of contact sign. The signing of the participants in the present study certainly represents other examples of contact sign. One might also expect comparable patterns of mouthing along the border of Quebec and Ontario, two provinces of Canada where different spoken languages (French and English) and sign languages (Quebec Sign Language [LSQ] and American Sign Language) are used by some of the residents (e.g., see Mayberry 1978 and Miller 2001 for discussions of LSQ), or in parts of Spain where Spanish Sign Language (LSE) and Catalan Sign Language (LSC) interact with Spanish and Catalan. However, a similar situation may not necessarily occur along the border of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, a border where different sign languages may be used but not different spoken languages.

Addressing the use of NMS (in the cases presented here, those that accompany content question signs) and the use of mouthing while articulating signs makes it evident that some facets of signed language contact are different from most types of spoken language contact. The reason is that spoken language production does not allow for multiple articulators (e.g., the hands/arms. mouth, and head in general) to be working simultaneously and producing concomitant articulations from different languages. One of the most salient differences between signed and spoken modalities is the tendency for simultaneous structure in sign and sequential structure in speech (Klima & Bellugi 1979, Meier 2002). The present work uses data from a contact situation to provide more evidence for that claim.

The examples of interference discussed here represent only one aspect of contact between two signed languages. Quinto-Pozos 2002 suggests that various other phenomena result from such contact. Some of the results parallel contact between spoken languages (e.g., code-switching; also see Quinto-Pozos in press for other accounts of LSM–ASL code-switching from these border data). But that study also reports on the substantial use of gestures and points for communication in these settings and how such devices may serve as buttresses to comprehension for monolingual signed-language users in these contact settings. Continued work on contact may reveal even more similarities, and some differences, between languages in contact within each modality.

SUMMARY

It seems that contact between two sign languages exhibits some of the same types of phenomena that ensue when two spoken languages come into contact with each other. This is true for the concept of interference. However, it also seems that contact between sign languages may be unique in some respects, and this has to do with the fact that sign language users can use several articulators (e.g., the hands, the head, and the mouth) simultaneously in order to provide various types of linguistic material concomitantly. One point that is particularly interesting from the data presented here is that some signers predictably and systematically produce forms from their second language that are influenced by their first sign language, but not all signers do. This is an area that merits further exploration, and a suggested focus could be on the perception of examples of interference in an effort to determine the degrees of salience of various aspects of the suggested interference.

APPENDIX

Transcription conventions:

Words in uppercase letters denote glosses of LSM or ASL signs; LSM signs are in Spanish and ASL signs are in English

Semantically equivalent ASL and LSM signs separated by a slash, “/”, denote signs that are articulated similarly (i.e., at least two phonological parameter values are shared) between the two languages.

Dashes between uppercase letters denote fingerspelled items.

Lowercase letters denote several items: points, descriptions of classifiers, and gestures.

CL denotes the use of one of the classifier types described in Supalla 1986

+ denotes a single cycle of repetition in the movement parameter of sign formation.

Any non-manual signal (NMS) is shown on a line above the element(s) that it accompanies, but a NMS is included in the transcription only when it is relevant to the discussion.