Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2005

This article examines evolving linguistic practices in the Spanish-Rapa Nui (Polynesian) bilingual community of Easter Island, Chile, and in particular the transformation of Rapa Nui Spanish speech styles. The island's rapid integration into the national and world economy and a vibrant indigenous movement have profoundly influenced the everyday lives of island residents. Although community-wide language shift toward Spanish has been evident over the past four decades, the Rapa Nui have in this period also expanded their speech style repertoire by creating Rapa Nui Spanish and syncretic Rapa Nui speech styles. Predominantly Spanish-speaking Rapa Nui children who have imperfect command over Rapa Nui are today adopting a new Rapa Nui Spanish style. Ethnographic and linguistic analysis of recorded face-to-face verbal interactions are utilized to analyze the development, structure, and social significance of Rapa Nui Spanish varieties and to locate them within the complex process of language shift.I wish to express my appreciation to the Rapa Nui and other residents of Easter Island for so kindly welcoming me into their homes and allowing me to participate in their daily life. I would also like to thank my research assistant, Ivonne Calderón Haoa, who helped me record and transcribe speech events. This article is based on field research supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant No. SBR-9313658), the Wenner-Gren Foundation (Grant No. 5670), the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Yale University, and the Institute for Intercultural Studies. Parts of this article were presented at the 2004 meeting of the Linguistic Society of America and the 2004 meeting of the Association for Social Anthropology in Oceania. I thank those who offered comments on earlier versions, in particular two anonymous reviewers, Jane Hill, Robert and Nancy Weber, Christine Jourdan, Niko Besnier, Jean Mitchell, and Lamont Lindstrom.

Language use and social identity among the Rapa Nui of Easter Island have been profoundly influenced by the events of recent history.1

Earlier encounters with outsiders nearly devastated the Rapa Nui community. The island's population, roughly estimated to have been about five thousand in 1860, collapsed within the following two decades to little more than one hundred as a result of slave raids for agricultural work in Peru, and the consequent spread of disease (McCall 1980). Given this history, it is remarkable that the Rapa Nui language survives today. Chile annexed the island in 1888, and during the following two-thirds of a century it gradually established authority over its colony, primarily by delegating control to a private sheep ranch company aptly named the “Easter Island Exploitation Company.” This company leased the island from Chile between 1895 and 1955 and confined the Rapa Nui to Hanga Roa

village, leading to several revolts. The Chilean navy took control of the island in 1953. The Rapa Nui were not granted full citizenship rights until 1966 (El Consejo de Jefes de Rapanui & Hotus 1988; Porteous 1981). In the mid-1950s, Chile sought ways to increase the integration of the island into the nation-state by sending a dozen Rapa Nui children and young people to study on the mainland. Upon their return in the mid-1960s, many of these Rapa Nui worked in newly created civilian institutions on the island, including the school and local government, and became important community leaders.

Nonetheless, many Rapa Nui children have grown up speaking Spanish. Today about half of the island's 3700 residents are Rapa Nui, while most others are Chilean “Continentals” from the mainland. Virtually all residents speak Spanish. By my estimate, roughly two-thirds of the Rapa Nui can speak Rapa Nui, but most of these speakers are adults. According to studies by two resident American linguists from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (Thiesen de Weber & Weber 1998), the proportion of local elementary school children who speak Rapa Nui as a maternal or predominant language decreased sharply from 77% in 1977 to 25% in 1989. Among children enrolled in kindergarten through seventh grade in 1997, none were considered Rapa Nui-dominant, only 7.5% (49 students) were considered balanced bilingual, and only an additional 12.3% (80 students) spoke Rapa Nui well or regularly.

My focus in this article is on the transformation of the Rapa Nui Spanish speech style and on the role played by predominantly Spanish-speaking Rapa Nui children in shaping it. Although definitions of bilinguality vary widely, by most definitions Rapa Nui children would be considered, at best, as only marginally bilingual.2

See Bloomfield 1935 for an example of the restrictive definition of bilinguality, and Macnamara 1967 for a very broad definition which regards minimal competence in comprehension as sufficient to consider an individual bilingual. See Hamers & Blanc 2000 for a discussion of the conceptual range and its theoretical and methodological implications.

Studies of language shift and loss have identified three major areas of change in declining languages: structural simplification (increased regularity and loss of productivity), domain restriction, and style reduction.3

See, for example, contributions to Dorian 1989 and Brenzinger 1992.

See also Kulick (1992:1–3) for a discussion of the maintenance and divergence of dialects and languages in Papua New Guinea despite extensive contact.

Although a process of language shift to Spanish is advanced and undeniable on Rapa Nui, it has been accompanied by an important and simultaneous diversification of the local communicative style repertoire. Significant elements of this diversification are the development of Rapa Nui ways of speaking Spanish (or Rapa Nui Spanish speech styles) and, more recently, syncretic ways of speaking Rapa Nui (or syncretic Rapa Nui speech styles). These new ways of speaking have come to characterize much of daily linguistic practice among the Rapa Nui. I use the terms “styles” (Irvine 2001) or “ways of speaking” (Hymes 1974b) to describe the use of linguistic varieties in order to foreground the speakers' role in creating their orientations toward the world and the situatedness of performance. I will highlight the interplay between innovations and constraints in interpreting changing linguistic practices, in particular in the use of the spreading language in a situation of language shift.

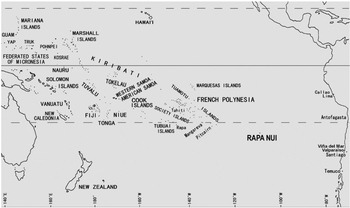

Locally significant Spanish speech styles are Chilean Spanish and Rapa Nui Spanish. Chilean Spanish is a set of Spanish varieties originally spoken in mainland Chile, particularly in the Santiago-Valparaíso-Viña del Mar metropolitan area (see Fig. 1). Rapa Nui Spanish originated out of strategies of second language acquisition employed by native Rapa Nui speakers during the initial spread of Spanish and development of bilingualism during the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, after Chile annexed the island in 1888. Rapa Nui Spanish is characterized by linguistic simplification and “interference” of Rapa Nui features and other contact phenomena.5

In his discussion of bilingualism among the Rapa Nui in the 1970s, Chilean sociolinguist Gómez Macker described the “Island Spanish” as one of the most “dialectalized varieties” of Spanish spoken in Chile (1982:96).

Thomason 2001 uses the term “interference” as a cover term encompassing a wide range of contact-induced change and discusses various subtypes such as “borrowing”, shift-induced “substratum interference” through imperfect learning, “code-switching”, and “code alteration” (the latter two are equivalent of Gumperz's (1982) “conversational code switching” and “situational code switching” respectively). My use of the term “interference” is narrower in the sense that it does not include neither conversational or situational codeswitching, and I treat interference and conversational codeswitching, but not situational codeswitching, as kinds of bilingual simultaneity. I view bilingual simultaneity as a phenomenon that is definable structurally (i.e., having bilingual elements present simultaneously) and whether or not the simultaneity or its indexical meaning is intended by the speaker.

Map: Rapa Nui in the Pacific Ocean

I employ the term “syncretism” to refer to the relatively new ways of speaking Rapa Nui that have emerged since the 1970s and 1980s and which characterize much of contemporary linguistic practice among the Rapa Nui and index their new ethnic identity. Rapa Nui-Spanish bilingual speakers use various forms of bilingual simultaneity such as interference and frequent conversational codeswitching, “the juxtaposition within the same speech exchange of passages of speech belonging to two different grammatical systems or subsystems” (Gumperz 1982:59).7

Linguistic syncretism is produced by various forms of bilingual simultaneity (e.g., interference, conversational codeswitching, convergence, bivalency). See Hill 1989 for a characterization of syncretic speech as an active and strategic linguistic practice on the part of speakers. Through such linguistic choices speakers variably highlight, suppress, or make ambiguous the oppositions found in historical associations between linguistic materials and social meanings. See pages 737 and 742 for examples of convergence and bivalency.

Syncretic speech which constitutes a speech style that is widely diffused in a community has been described as a “code-switching mode” by Poplack 1980. Such characterization of “unmarked choice” (Myers-Scotton 1988) of language alteration suggests that the contextualization value of each individual switch has been weakened through frequent juxtapositions. It also raises the question of whether code distinctiveness and the speakers' awareness of language boundaries and intention in switching are necessary for their linguistic behavior to be called codeswitching. See Alvarez Cáccamo 1998 for a discussion of codeswitching and language alteration, in particular how language alteration does not necessarily constitute codeswitching. See Gardner-Chloros's (1995) and Woolard's (1998) critiques of focusing on and idealizing codeswitching thereby reiterating discrete linguistic systems in bilingual usage.

The Rapa Nui have come to view syncretic speech as such a normal way of speaking in informal in-group interactions that they would find it unnatural or difficult to speak Rapa Nui void of any Spanish elements. As such, the concept of syncretism applies not only to linguistic characteristics of Rapa Nui speech but also to the dominant interactional norm in in-group interactions in which the language users allow and expect bilingual simultaneities and demonstrate great accommodation toward speakers of varying bilingual competence and preference. I have elsewhere examined the expansion of syncretic Rapa Nui use among adult Rapa Nui in public and political speech situations in the context of the rising indigenous movement and political negotiations with the national government, and the ways this has contributed to breakdown of the previously established sociolinguistic hierarchy and of diglossic functional compartmentalization of languages (Makihara 2004).

In the present essay, I focus on explaining the continuation and transformation of Rapa Nui ways of speaking Spanish. The language socialization contexts have allowed Rapa Nui children to develop and maintain at least passive knowledge of the Rapa Nui language. They are acquiring Rapa Nui Spanish in addition to Chilean Spanish, but they are developing their own Rapa Nui ways of speaking Spanish, which are structurally distinct from older Rapa Nui Spanish. To distinguish the two, I will employ the abbreviation R2S1 – Rapa Nui as a second language, Spanish first – to identify this newer Rapa Nui Spanish in contrast to the older but persistent R1S2, the Rapa Nui Spanish variety spoken mainly by Rapa Nui adults. Unlike R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish, R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish is characterized mainly by the inclusion of Rapa Nui lexical items.

A growing literature in the field of “language socialization” (Ochs & Schieffelin 1984) – socialization through language and socialization to use language – emphasizes the importance of the sociocultural context in the development of children's “communicative competence” (Hymes 1972), their ability to use language appropriately in the community, and the importance of its central role in the construction of selfhood and social relations.9

See Garrett & Baquedano-López 2002 for a recent review of the literature.

It is difficult to say with precision what people were initially responsible for developing the R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish speech style, because Spanish speech with Rapa Nui lexical interference or codeswitches is used by all of the following three groups: monolingual or predominantly Spanish-speaking Rapa Nui (mostly children), long-term continental Chilean residents who are familiar with Rapa Nui, and Rapa Nui-Spanish bilinguals (mostly Rapa Nui adults). What is interesting to note is that this speech style is emerging as one stylistically differentiated from R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish, in a way that I interpret to be associated with a Rapa Nui “voice” in Spanish that is sometimes “ventriloquated” (Bakhtin 1981) or appropriated by fluent Rapa Nui speakers when speaking to Rapa Nui children.

Although children's imbalanced productive competence in Spanish and Rapa Nui motivates the structural characteristics of the new Rapa Nui Spanish speech style they use, I argue that this alone does not explain the reason for its usage. By taking a “discourse-centered” approach to language, identity and culture (Sherzer 1987),10

See, for example, Lutz & Abu-Lughod 1990, Duranti & Goodwin 1992, and Eckert & McConnell-Ginet 1992 for an approach that stresses the situatedness of meaning and the role of verbal performance and practice in the construction of culture, identity, and social relations.

The present study is based on an ethnographic and linguistic analysis of face-to-face verbal interactions recorded during three years of field research on the island over the past decade. The article is organized as follows. The next section analyzes the linguistic characteristics of adults' speech styles which form part of the communicative style repertoire of the Rapa Nui community. The third section focuses on children's speech and the characteristics of its environment by describing bilingual language socialization and the syncretic interactional norm. It also discusses how the characteristics of adults' and children's Rapa Nui Spanish speech relate to bilingual competence and sociolinguistic change. The conclusion discusses the social meanings of Rapa Nui Spanish speech styles and how they relate to ethnic identity formation and language shift.

The development of a speech style involves differentiation within a system of possibilities, linking co-occurring linguistic features to social meanings, and constituting and indexing social formations such as distinctiveness of individuals and groups in specific contexts of communicative situations (Irvine 2001). To understand the nature and social meanings of Rapa Nui ways of speaking Spanish, it is necessary to consider how these speech styles relate to others in the communicative style repertoire. For this purpose, I find it useful to identify at least four speech styles: syncretic Rapa Nui, R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish, R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish, and Chilean Spanish. Chilean Spanish and especially Rapa Nui Spanish speech styles intersect with syncretic Rapa Nui as they are recruited to serve as resources for conversational codeswitching and other forms of bilingual simultaneity. R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish, which originated with strategies of second language learning, continues to be used along with the target variety, Chilean Spanish, while an emerging new variety of Rapa Nui Spanish (R2S1) is being added to the expanding communicative style repertoire. Below I will describe the linguistic characteristics of the adults' speech styles and their use, followed by children's speech styles in the next section.

This variety of Rapa Nui Spanish is spoken primarily by adult bilingual Rapa Nui speakers and is characterized by simplification, or rule-generalization, and Rapa Nui interference, originating in imperfect second language acquisition. Linguistic simplification is a process of rule generalization which involves “the higher frequency of use of a form X in context Y (i.e. generalization) at the expense of a form Z, usually in competition with and semantically closely related to X” (Silva-Corvalán 1994:3), and it results in simplified linguistic systems or subsystems. Although often distinguished as external and internal factors, respectively, both interference and simplification occur commonly in the context of language contact – second language acquisition and shift-induced language attrition alike – and many linguistic consequences may be interpreted to have been caused by the combination of these two processes.

At the phonological level, sounds that are unique to Spanish are replaced to various degrees by Rapa Nui sounds in R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish. Spanish has a larger set of consonants, and those that are not part of the Rapa Nui phonological inventory are (but not always) replaced by Rapa Nui sounds with approximately the same place or manner of articulation, e.g.,

.

11For example, jarro

‘jar, jug’ may be pronounced /karo/, guitarra

‘guitar’ as /kitara/, familia ‘family’ as /famiria/, idea ‘idea’ as /irea/, sábana ‘sheet’ as /tavana/, and calzoncillo

‘underwear’ as /karsonsio/∼/kasontio/. A range of phonological interference can be illustrated in the multiple realizations of después ‘afterwards’: /despues/, /despue/, /despue/, /depue /, or /repue/, listed here in order of increasing conformity to Rapa Nui phonology. The variant choice is sometimes predictable from the individual's bilingual competence and preference, but the same person may use multiple variants, which potentially constitutes strategic interference pointing toward Rapa Nuiness or Chileanness. Presently, the Rapa Nui speakers replace [l, d] with

more often than [g, x] with [k], and replacing

with [t] (or even with [k] as in /fektivo/ for festivo ‘festive’) rarely occurs except in proper nouns (e.g., /tire/ for Chile

), reflecting differential nativization or incorporation of these sounds.

For example, canasto ‘basket’ is pronounced either /kanasto/ or /kanato/ in Rapa Nui Spanish, and /kanato/ has been incorporated as a loanword in Rapa Nui, leading a semantic change in the Rapa Nui synonym kete, which has come to denote ‘pocket’. Note, however, that the Chilean Spanish variant for canasto involves aspiration: /kanahto/. The word-final /d/ and the pre-consonantal and word-final /s/ are sociolinguistic markers of speakers' education and formality of speech situation in continental Chile (Rabanales 1992).

At the morphosyntactic level, simplification, sometimes in combination with Rapa Nui interference, is commonly observed, especially in the use of nominal and adjectival gender, verbal conjugations, and determiners. For example, a 75-year-old woman uttered the following while telling me a story over her kitchen table13

Rapa Nui elements, in italics, are transcribed using a single closing quote ['] for the glottal stop,

for the velar nasal, and a macron for the five long vowels. For Spanish elements, a close-to-standard Spanish orthography is used except when forms significantly diverge from standard Spanish, which is provided in parentheses. Spanish borrowings are underlined and italicized, non-Spanish borrowings italicized and broken-underlined. The equal sign [=] to connect two utterances indicates that they were produced with noticeably less transition time between them than usual. The names of all speakers are pseudonyms.

The following abbreviations are used in glosses: 1, 2, 3, first, second, third person; DO, direct object; fem., feminine; ind., indicative mood; masc., masculine; PERS, person marker; pl., plural; pres., present tense; PRF, perfective aspect marker; PRO, pronoun; PROG, progressive aspect marker; refl., reflexive; RN, Rapa Nui; sing., singular; Sp., Spanish.

From the context of the story, she meant ‘he saw him’, which would be expressed in standard Spanish as El lo vió. The use of the feminine third-person pronoun eia (ella ‘she’) instead of él ‘he’ probably arises from the combination of rule-generalization and the indirect interference of the Rapa Nui pronoun system, in which gender distinction is not made (e.g., 3 sing. ia). The substitutions of

in eia ‘she’ and [r] for [l] in ro ‘him’ result most likely from phonological interference from Rapa Nui, which does not have lateral approximant phonemes

. The subject of this sentence, a eia, shows another instance of interference. It includes a, which is most likely the Rapa Nui personal particle a which precedes pronouns and names of persons and places.

14From the context of the narrative, the alternative interpretation, to take a to be a hesitation marker or the Spanish complement preposition in the noun phrase fronted for the purpose of topicalization, is less likely.

In the verbal inflections of R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish we can observe abundant simplification at work, possibly also resulting from indirect interference. Unlike in Spanish, in Rapa Nui tense is not an overt grammatical category and person is not grammaticalized in the form of verbal inflections. In R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish, present indicative verbal forms are commonly used in lieu of other tenses, aspects, and moods (e.g., preterit, imperfect, progressive, future, conditional and subjunctive). In addition to the preference for present tense and indicative mood, R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish speakers also show preference for third-person singular forms regardless of contextual person and number. For example, the 3rd sing. indicative present verb form is used instead of the 1st sing. indicative present (see ex. 2), the 2nd sing. imperative (3), the 1st plural subjunctive (4), or the 1st sing. preterit (5). In (6), the verb is conjugated in the past tense but the 3rd sing. form is used instead of the 1st plural form. The preference for 3rd sing. forms is motivated by their higher frequency of occurrence in standard Spanish varieties, in which the 3rd sing. forms coincide with the forms required with the formal second person pronoun usted (as opposed to the informal tú).15

The third person singular (rather than the infinitive) form is also the form that Spanish verbs take when transferred into otherwise Rapa Nui utterance, and this may also reinforce the preferred status given to this form within Rapa Nui Spanish. Spanish verbs, predominantly in their 3rd sing. forms, are also sometimes used as nouns in the Spanish environment or are transferred into Rapa Nui as nouns, which seems to reflect the fluid distinction between noun and verb in Rapa Nui and other Polynesian languages (Biggs 1971, Broschart 1997, Tchekoff 1984). See Makihara 2001 for a discussion of the mechanisms of adaptation of Spanish elements in Rapa Nui.

The simplification of the linguistic system is common in change resulting from language contact and is often accelerated by contact in both the spreading and the receding language in situations of language shift.16

Contact-induced change, however, does not necessarily involve simplification. Irvine & Gal 2000, for example, analyze the social and ideological contexts of acquisition by Nguni speakers of clicks borrowed from neighboring Khoi languages.

Language contact situations often accelerate changes that are latent in the receding or spreading languages.17

For discussions of internally motivated and contact-induced changes involving simplification in other languages in a language shift situation, see Dressler 1981 and Maandi 1989.

R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish intersects with Rapa Nui through combinations of forms of bilingual simultaneity: codeswitching (e.g., ex.10) and convergence (11) in combination with interference. In (10), the speaker employs the Rapa Nui ergative construction by using the agent marker e followed by the definite article te. Equivalents in standard Chilean Spanish can take either a passive or an active construction. The passive construction would have required the use of a past participle, whose subject, if a pronoun instead of a noun, must be marked for gender and number (e.g., estos/estas tiene/tienen que ser estudiado/a por la comisión de desarrollo). The active construction would have required making the agent (la Comisión de Desarrollo) into a grammatical subject to be placed in front of the auxiliary verb tiene, and using the direct object clitic, which must be marked for gender and number (lo/la/los/las). Rather than explaining the resulting utterance as resulting from extensive simplification in combination with elements of Rapa Nui interference with e te replacing the Spanish elements por el, it makes better sense to view this as codeswitching after the topicalized prepositional phrase to syncretic Rapa Nui, in which Rapa Nui provides the morphosyntactic frame. The notion of the matrix language (Myers-Scotton 2002) – the language that provides the morphosyntactic frame of bilingual utterances – is useful. The switch may have been triggered by the use of the Spanish modal tiene que, which is commonly used in Rapa Nui speech to express obligation or necessity and is beginning to replace the Rapa Nui construction with the prepositional imperfective aspect particle e.18

See Makihara 2001 for a discussion of the introduction of tiene que and its syntactic adaptation in modern Rapa Nui speech.

Ex. (11) illustrates a case in which both Spanish and Rapa Nui influence the morphosyntactic frame where one can speak of convergence. Convergence is defined as the process by which certain aspects of the grammatical systems of languages under contact become similar to one another, which may be directly caused by interference or by internally motivated changes accelerated by contact (Silva-Corvalán 1994). In this utterance, a codeswitch to Chilean Spanish introduces the quoted speech. As for the rest, although most of the morphemes come from Spanish, the utterance is syntactically congruent in both Rapa Nui (VS basic order; subject complement may be fronted) and Spanish (SV basic order; predicate may be fronted), creating a “composite matrix language” (Myers-Scotton 2002). The Rapa Nui possessive preposition ’a19

Similarly to other Polynesian languages, but unlike Spanish, Rapa Nui has two classes of possessives: O and A categories, whose choice is generally determined by the given relationship that the possessor has with the possessed. A-possession is the marked form, which indicates the active or dominant possessor. While possessive class choice in Rapa Nui is relatively predictable and predetermined given possession relationships (for example, A-class for one's child), the speaker's choice of class can alter the meaning of the nature of the possession relationship (see Makihara 2001 for examples). Here the use of the A-class possessive possibly adds emphasis to the control and responsibility that the possessor should have toward the possessed – that is, the president of Chile toward his promise.

There are at least two subvarieties of Chilean Spanish used by the Rapa Nui. Formal Chilean Spanish tends to be used in interethnic communication in state-sponsored institutional settings in written and spoken modes, and its choice is characterized by diglossic situational codeswitching. Informal Chilean Spanish is used in informal settings and both among the Rapa Nui and communication with the Continentals. Its spread was accelerated with increasing intermarriage with Continentals and the influx of Continental residents that followed the opening of the air route from Santiago and the arrival of television transmissions in the late 1960s and the 1970s. Among the Rapa Nui, teenagers and young adults tend to use informal Chilean Spanish more frequently, and it is often embedded in syncretic interactions that involve Rapa Nui speakers. With the arrival and spread of computer-mediated writing and communication, young Rapa Nui have begun to write in informal Chilean Spanish more frequently as well.

The following transcript, Text 1, illustrates the situationally motivated choice of formal Chilean Spanish in a community meeting to discuss the newly enacted Indigenous Law in 1994. The 55-year-old bilingual Rapa Nui man, who runs a tourism business and is active in local politics, is having an exchange with a Continental resident lawyer working for the local municipality. The excerpts show a number of complex verbal conjugational forms and syntactic constructions such as present and imperfect subjunctive moods, pluperfect tense, and passive voice, and of pragmatic features such as clitic-doubling for emphasis, the use of titles, por favor ‘please,’ and requests using conditional and subordinate clauses in imperfect subjunctive for politeness.

Features of informal Chilean Spanish include extensive lexical items and phrases such as pololo/polola ‘boy-/girlfriend,’ fome ‘boring’, al tiro ‘right away,’ de acuerdo ‘OK’. At the morphological level, it includes the use of diminutive and appreciative -it- (e.g., chiquito and chiquitito ‘small’) and “mixed verbal voseo” (Rona 1967, Torrejón 1991) – the use of the pronoun tú with the verbal paradigm associated with the pronoun vos in other varieties of Spanish, for example, ¿Cachai? ‘Follow me/Did you understand?’ from English catch, or ¿Cómo estai? ‘How are you?’. In (12a) a mother addresses her 13-year-old niece, using andai (vos form of the verb andar ‘to walk’) instead of (tú) andas ∼ (usted) anda (see also 12b and 12c). The pronoun vos is not used in Rapa Nui Spanish (see also Text 2).

Many Rapa Nui speakers who have by now acquired Chilean Spanish continue to use Rapa Nui Spanish both in interactions with non-Rapa Nui and among themselves. Rapa Nui Spanish is often embedded within syncretic Rapa Nui speech styles. Imperfect Spanish acquisition (illustrated by older speakers in exx. 1–8) is no longer the primary factor in the continued use of Rapa Nui Spanish. Although there is a proficiency continuum between R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish and Chilean Spanish which broadly corresponds to speakers' age, features such as phonological interference and simplified verbal morphology continue to be used by younger adult Rapa Nui speakers, suggesting maintenance of features that originally involved “involuntary” (Thomason 2001:141) second language acquisition strategies. Simplified usage of Indonesian pronouns among Javanese Indonesians, as another example, can hardly be explained by a second language acquisition strategy or cognitive load lessening. As Errington 1998 argues, such linguistic changes need to be examined carefully for the ways in which speakers create new social meanings using multiple speech styles, and for how these choices relate to the larger context of the political economy and ideology of language. With rising Spanish competence, the degree of simplification and interference, along with variability in resulting forms, may have been reduced, but such forms continue to be maintained through speakers' preference for Rapa Nui Spanish, and they are becoming what Labov 1972 calls “markers,” which show not only ethnic but also stylistic stratification.

For example, in a public meeting conducted entirely in Spanish between some 200 Rapa Nui participants and eight visiting Chilean government officials to debate the then recently proposed Indigenous Law of 1994, a young Rapa Nui male political activist in his early thirties rose to argue against the law. Text 2 is a brief extract from his long exposition in Rapa Nui Spanish.

Although the speaker speaks Spanish often and I have heard him speak with considerably fewer R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish features, his speech on this occasion was replete with Rapa Nui Spanish features (e.g., phonology, and gender and number agreement). His linguistic choices served better to establish Rapa Nui distinctiveness and underline Rapa Nui claims to self-determination in front of Chilean government officials at a critical political juncture. The speaker, in fact, stands out from others in his age cohort who speak Chilean Spanish more frequently. He seems to be actively resisting assimilating his speech toward Chilean Spanish. His choice of the 2 pl. pronoun vosotros (line 3) is also interesting in this regard, as the form is used almost exclusively in northern and central Spain and contrasts with the standard (informal and formal) Chilean Spanish form ustedes, which the speaker uses in other parts of his speech (e.g., line 5).20

I have observed another, female Rapa Nui political activist also employing vosotros in a similar situation in 2003, embedding the term within otherwise Chilean Spanish speech. She later explained to me that she had heard this pronoun used by delegates at a UN function she had participated in abroad. In characterizing Chilean Spanish, Rabanales (1992:578) notes that vosotros (with the corresponding verbal forms) is used rarely and only in rhetorical style in the “formal educated” variety. I have not heard the Rapa Nui use vos, the informal second person singular pronoun, which is used along with tú in Chilean and other varieties of New World Spanish. See Torrejón 1991 for a description of the use of pronominal voseo (vos) and verbal voseo (e.g., tú llegái ‘you arrive’) in continental Chile.

In addition to such situationally motivated choices, Rapa Nui-Spanish bilingual speakers have come to use their bilingual semiotic resources (languages, speech styles, and forms of bilingual simultaneity) within the same speech situations. Based on linguistic analysis, one can establish the “matrix” and “embedded” languages of given bilingual utterances, the degrees and direction of linguistic integration, diffusion, cognitive membership of items in the two lexicons, and the levels of linguistic organization involved, in order to interpret particular choices of linguistic elements as borrowing vs. interference vs. codeswitching.21

The degree of conscious and strategic awareness on the part of the speaker and the audience are, however, difficult to be certain about, and one should use caution in ascribing intention and meaning in individual codeswitches or assuming salience of the distinction between the “languages” or “codes” between which switching occurs. In discussing “contextualization cues,” Gumperz (1982:131) notes that “[f]or the most part [they] are habitually used and perceived but rarely consciously noted and almost never talked about directly.” The taken-for-granted nature of such linguistic elements is especially pervasive for prosodic, phonological, and grammatical variants, which are relatively nonreferential (Silverstein 1981).

Codeswitching and other forms of bilingual simultaneity in syncretic speech style may serve a range of discourse and indexical functions as contextualization cues. They help to signal contextual presuppositions, or linguistically to mark changes in “footing,” or the alignment between speaker and audience, and the “participation frame” of a speech event (Goffman 1981, Gumperz 1982) (see Text 5 for use of codeswitching in quoting). Text 3 below illustrates the use of codeswitching to index reported speech, though this case is likely a non-homologous representation of code choice (or an invented speech event), in which the narrator strategically modifies the “original” speech act through manipulation of language choice within the narrative reporting of the speech event. The text is taken from a casual joking conversation among five Rapa Nui men ranging in age from early thirties to early forties. Manu Iri claimed that he was of English descent, implicitly suggesting that he was a descendant of the British-Rapa Nui Edmunds family.22

As one of the Rapa Nui kin groups, the Edmunds family owes its name to Percy Henry Edmunds, a Scottish administrator of the Easter Island Exploitation Company, who was on the island between 1905 and 1929 and left eight children.

Paratoa is a borrowing from French paletot ‘overcoat.’ What the speaker meant by “the time of paratoa” was the old time when such foreign items and words were introduced, alluding also to his grandfather's father and other non-Chilean foreigners' presence.

Manu Iri initiates the report in Rapa Nui: ‘Listen, my grandfather Urupano [Rapa Nui Spanish for ‘Urbano’] said that, he said to me’, rephrasing the Rapa Nui indirect quotation introducer pe nei e ‘like this’ to the direct quotation structure followed by the vocative phrase ‘Listen son’. Then he switches to Spanish to report his grandfather's speech. The repeated term íngris ‘English’ is a rendition of the English word rather than of Spanish inglés. The speaker's choice of Spanish for the quoted speeches in constructing the exchange with his grandfather is contrasted with his use of Rapa Nui he kı mai ‘(he) says/said to me’ and he kı o'oku ‘I say/said’ in introducing the quoted speech. The choice of Spanish likely is owed to the limitation of the speaker's linguistic repertoire, which does not include English, whereas the foreignness of Spanish is exploited. Thus the choice of Spanish in the reported speech, as opposed to Rapa Nui – which more likely was used in the original speech if it did occur – renders the Englishness or foreignness of his grandfather more authentic. At the same time, his use of Rapa Nui kin terms ata ‘eldest son’ (shortened form of atariki) and makupuna ‘grandchild’ in the quoted speech validates his Rapa Nui ancestry. His use of Rapa Nui Spanish and informal Chilean Spanish features – the Spanish kin term abuero ‘grandfather’ (Sp. abuelo) and an informal Chilean Spanish adverb po24

Po derives from the standard Spanish adverb pues ‘then, well, well then’, and is used frequently in informal Chilean Spanish in clause-final position, signifying something like ‘certainly’ to underscore the point. Though semantically related, the syntactic position of po diverges from pues: Sí po (Chilean Spanish) vs. Pues sí (standard Spanish), both of which mean ‘Yes, certainly’.

As another example of the discourse function of codeswitching, I have elsewhere discussed an example of participant-turn-related codeswitches in which speakers seem effectively to exploit the differences between the Spanish and Rapa Nui grammatical systems (in that case, overt vs. covert grammatical gender marking) in unreciprocated code choice across speakers (Makihara 2004, Table 2). An example of less code-contrasting but still structurally sophisticated use of interference can be seen in the following Rapa Nui Spanish utterance, in which a Rapa Nui grammatical morpheme – the postverbal progressive aspect marker 'a – is added at the end of an otherwise Spanish sentence.

The particle is normally used within the Rapa Nui verbal frame, with preverbal e for an imperfective aspect, or with preverbal ko for a perfect aspect (e.g., Text 5, line 1), and here it serves to emphasize the enduring visible and known quality of the expressed state, in this case that the speaker is still young. This element can be interpreted to have a certain “bivalent” quality – another type of bilingual simultaneity (Woolard 1998) – because it is phonologically similar to and syntactically congruent with the Chilean Spanish clause-final discourse marker ah to indicate emphasis and reiteration (Makihara, 2004, Table 1).

The above descriptions illustrate the level of linguistic heterogeneity in adults' speech style repertoire. In the next section, I turn the focus to contexts of family language socialization and the characteristics of emerging subvarieties of Rapa Nui Spanish speech styles.

Rapa Nui language socialization practices changed markedly after the mid-1960s, when the small island community found itself at the beginning of a period of accelerated social transition. Spanish quickly entered into family domains, especially via increasing intermarriage with Continentals. An intergenerational gap in bilingual competence soon developed as the proportion of “semi-speakers” (Dorian 1981) of Rapa Nui increased in the population younger than thirty. Today, most Rapa Nui children receive relatively greater exposure to Spanish than to Rapa Nui in their daily life, especially through school and TV and radio programs, as well as from their peers and siblings, with whom they interact predominantly in Spanish. Since the mid-1970s, the influence of Chilean television programs and videos has been intense; many Rapa Nui residents spend several hours a day in front of the television set. Broadcasts were predominantly in Spanish until 1999, when a local municipal television station started also to broadcast some bilingual and Rapa Nui programs. In all but a few Rapa Nui households, children are now growing up with Spanish dominance, and the few Rapa Nui children who enter preschools with Rapa Nui dominance make the shift to Spanish dominance, often in a matter of weeks. This is partly because of preference shift after increased exposure to Spanish and because they are teased by other children for speaking Rapa Nui.

Local school instruction in Spanish began in 1934. The teaching of Rapa Nui as a subject was officially incorporated into the curriculum in 1976, although the Rapa Nui have participated as teachers and directors of the school since mid-1960s and had helped Rapa Nui students learn all subjects using that language.25

For decades classes were conducted mainly by Continental Chilean Roman Catholic catechists until 1971, when the Chilean Ministry of Education began to send teachers. The school has gradually expanded its levels, up to sixth grade in 1953, and twelfth by 1989. Today the municipal school has about 1000 students, although many students enroll in high schools on the mainland, aided either by governmental scholarship programs or funded by relatives. Literacy is still associated predominantly with Spanish. While Rapa Nui literacy practices have been on the rise in the last two decades (e.g., Rapa Nui classes at the local school, published and unpublished stories, poems, and songs), its orthography is still being standardized and there are variations in orthographic systems in use.

Spanish also plays an important part in Rapa Nui family life. Young siblings interact mostly in Spanish. I have observed some Rapa Nui parents talking to their preverbal young children using a Spanish baby talk register modeled after the Chilean style – simple phrases with repetitions, in a high-pitched voice with puckered lips, expressing affect and asking and answering questions on behalf of the babies. In one-on-one interactions, many Rapa Nui parents often address their children in Spanish rather than Rapa Nui. When addressed in Rapa Nui by an adult, children sometimes remain silent, or simply respond with Spanish ¿qué? ‘what?’, perhaps not having understood what was said or wishing to confirm what they understood by hearing it again in Spanish. Adults tend not to repeat their exact Rapa Nui utterances to a child, but they may accommodate and switch to Spanish. Alternatively, they may continue in syncretic Rapa Nui. As discussed below, such code choice is common in multiparty interactions involving more than one bilingual adult (e.g., Text 5, lines 12, 17–18; Text 6, lines 2 and 9). The children may maintain the conversation by responding in Spanish to adults who continue in syncretic Rapa Nui, constructing interactions characterized by what Gal 1979 calls “unreciprocal” code choice.

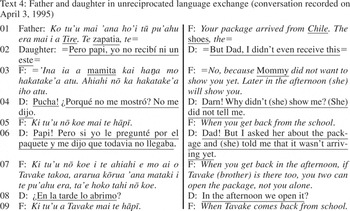

Text 4 below is an example of unreciprocated code choice in a dyadic interaction between a five-year-old child and her father, recorded in my absence, in which the child clearly understands what is said in Rapa Nui while insisting on her Spanish code choice.

Until three decades ago, Rapa Nui identity was associated with a naturally expected productive knowledge and performance of the Rapa Nui language, but it has since been reformulated to accommodate individuals with varying bilingual competences, preferences, and actual uses of the Rapa Nui and Spanish languages. Thus, unreciprocated language choice and codeswitching can be viewed as a manifestation of shifting Rapa Nui ethnolinguistic identity. Although intergenerational unreciprocated language choice reflects changing language acquisition patterns and language loyalties and the community-wide language shift, children participate actively in syncretic Rapa Nui interactions through which they develop and maintain at least passive communicative knowledge of Rapa Nui.

There is no denying that Spanish occupies a dominant place in the language socialization of Rapa Nui children, almost all of whom have higher proficiency in Spanish than in Rapa Nui, but they do receive quite rich exposure to Rapa Nui in their extended family environments. Especially when Rapa Nui adults are already engaged in conversation in syncretic Rapa Nui speech styles, they are likely to continue to speak among themselves and to address children in Rapa Nui. Such multiparty conversations are very common in Rapa Nui's extended family environment. Text 5 below illustrates such a context (see also Text 6). It is taken from an interaction recorded in my absence and involves a four-year-old child, Rosa, who has been described as always dominant in Spanish, although she receives relatively rich Rapa Nui input from her extended family members. Grandmother Lucia sits down next to Rosa, while continuing to talk in Rapa Nui with her co-mother26

Following a Hispanic Catholic custom, comadre or RN komaere ‘co-mother’ refers to the relationship between a mother and the godmother of her child.

Isa tells Lucia about how she had earlier chased away Rosa, who had been pestering her, by mockingly telling a dog to bite at her. Lucia, to whom Rosa had run, then quotes Rosa's words in Spanish, ‘The nua over there told the dog to eat me up!’ (line 4). The grandmother also reports on how her adult son, Kai, had laughed out loud upon hearing Rosa's accusation. Lucia continues to report that when Rosa was asked ‘What happened?’ in Spanish, she answered, ‘The nua made me eat with the dog’ (line 9). The reformulation of Rosa's report in terms of who was doing the eating, which is possibly due to Rosa's weak comprehension in Rapa Nui, causes further amusement among the adults. The teasing and laughter goes on in front of this child. Most of it is in Rapa Nui except for quoted speech in Spanish, which most likely helps draw Rosa's attention to the fact that they are talking about her. When Rosa approaches a tape recorder to touch it, her mother, Florencia, tries to stop her and tells Rosa in Rapa Nui to let go of it. Rosa defends herself in Spanish (unreciprocal language choice) by exclaiming Deja escuchar ‘Let listen’ (line 11, a nonstandard form of Déjame escuchar). When Rosa again approaches the player, Lucia draws other adults' attention in Rapa Nui, to which Rosa responds by saying again ‘Let listen’ in Spanish (lines 13–14). Ema proposes in Rapa Nui to take away the recorder, to which Isa agrees, and then both Lucia and Isa explain to Rosa in Rapa Nui that the recorder is her mother's and she is taking it to her house (lines 15–18). The latter part of the interaction (lines 11–18) involves the direct use of Rapa Nui by the adults toward the child, who protests in Spanish, constituting unreciprocated code insistence (see also Text 4).27

This contrasts with other communities, such as Catalans, Dyirbals, or Hungarians in Austria, where code choice is primarily interlocutor-based (Gal 1987, Schmidt 1985, Woolard 1989).

Schmidt 1985 observed among Dyirbal speakers in the Jambun Aboriginal community of northeastern Australia that elderly, fluent Dyirbal speakers constantly corrected younger people's Dyirbal speech. Schmidt argued that this was a significant factor in the declining use and ultimate obsolescence of the Dyirbal language.28

In Gapun, Papua New Guinea, Kulick (1992:220) observed that adults do not correct errors in Tok Pisin but do correct Taiap speech by children, who conversely mock parents' errors in Tok Pisin. For Mexicano-speaking communities of central Mexico, Hill & Hill 1986 discuss how the practice of purist quizzing and correctional acts by middle-aged men, which lead speakers to question “the moral and aesthetic value of Mexicano,” may work against the survival of the language (1986:140–41). Literature on Mexican-U.S. borderland identity points to the role of similar kind of “linguistic terrorism” (Anzaldúa 1987) in creating intraethnic group divisions, ethnolinguistic identity insecurity, and accelerating language shift to English in Hispanic communities in the United States.

The extended family is an important environment for language socialization in Rapa Nui for children, especially those who have a Continental parent or dominantly Spanish-speaking Rapa Nui (often young) parents. Many young adults and their children live within the same compound or neighborhood as the adults' Rapa Nui parent(s) and frequently spend time with their extended family, especially the children's grandparents and aunts (see Text 4). In the warmer seasons, and particularly during the school summer vacation between December and March, extended families and friends take their children to spend time away from the village by the coast, fishing, cooking, re-creating, and camping.

Rapa Nui children's preference for Spanish is not categorical: They prefer to use their dominant language, Spanish, in a way that marks it as Rapa Nui Spanish. The way in which these predominantly Spanish-speaking Rapa Nui children incorporate features of Rapa Nui into R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish differs fundamentally from how Rapa Nui features are incorporated into the R1S2 spoken primarily by fluent Rapa Nui speakers. As discussed above, R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish is characterized by grammatical features (e.g., phonological and morphosyntactic interference and simplification) and conversational codeswitching. R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish, in contrast, is characterized predominantly by lexical interference or borrowing from Rapa Nui.

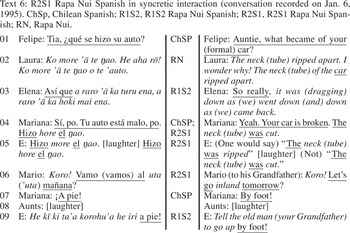

Text 6 illustrates the syncretic interactional context in the extended family, out of which new R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish has developed. The transcript is taken from a conversation among members of a large extended family gathered in preparation for the annual Tapati Rapa Nui cultural festival (Makihara 2005). Children helped as adults prepared the bark of a type of banana tree called maika ri'o to make cloth (kahu) for the festival costumes. Just prior to the transcribed segment, Elena, her cousin Laura, and I had been talking in Rapa Nui about the breakdown of the truck that had transported the bark. The transcript begins as six-year-old Felipe, who had just overheard our conversation, asks his aunt Laura in Chilean Spanish to explain what has happened. The middle column identifies the speech styles used in each speech turn or segment.

The text illustrates the stylistic multiplicity of syncretic interaction in which the new R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish is embedded. Laura explains to her nephew in Rapa Nui that the truck's ‘neck’

or motor hose was “ripped apart” (more) (line 2). Mariana, a six-year-old niece who understands more Rapa Nui than Felipe, adds in Chilean Spanish ‘Yeah, your car is broken’, and switches to R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish for ‘The neck got cut’, using the Rapa Nui terms for ‘neck’ and ‘to cut’ (hore):

This utterance rephrases Laura's earlier Rapa Nui utterance ([15]):

It is also equivalent to the following Spanish sentence, which would involve the use of the reflexive verb cortarse ‘to cut’. This may explain Mariana's choice of the Rapa Nui word hore ‘to cut’, or its relatively earlier acquisition in comparison to more ‘to rip apart’.

The nonstandard use or, more frequently, the deletion of the reflexive pronoun is also observed in adults' Rapa Nui Spanish (e.g., exx. 4, 19) and in children's Spanish (e.g., Text 5, lines 11 and 14). Amused by Mariana's use of the term hore ‘to cut’ (14), her other aunt, Elena, didactically rephrases ‘the neck was ripped’ in R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish, correcting only the choice of verb while following the R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish construction as formulated by Mariana:

Here, in order to rephrase the perfective aspect of Laura's utterance (expressed in Rapa Nui with ko + verb + 'a construction), Mariana uses the Spanish verb hacer ‘to do/to make’, conjugating it for past tense and thus using it as a carrier of tense+aspect in an auxiliary construction. In fact, such a ‘do’ construction is a common way to translate Rapa Nui verbal frames that involve pre- and post-verbal morphology into R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish.29

Although Spanish is the receding language among English-Spanish bilinguals in Los Angeles, Silva-Corvalán 1994 observes that the similar construction with hacer in which hacer serves as a carrier of tense-mood-aspect occurs in their Spanish speech. Myers-Scotton (2002:134ff.) discusses how the ‘do’ verb construction which carries inflection (as required by the matrix language frame) is a common means for introducing a verb from another language (the embedded language) in codeswitching, attested in typologically diverse languages.

Toward the end of the transcript, Mario, also six years old, yells out to his grandfather sitting on the bench several meters away in R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish, using Rapa Nui terms for ‘grandfather’ and ‘inland’:

Koro and nua are Rapa Nui terms for respected man and woman respectively. Although newer kin terms which derive from Spanish are often used to designate one's parents generation in Rapa Nui speech –

‘father’, mama ‘mother’, mama-tia ‘aunt’, and papa-tio ‘uncle’ (from Spanish papá ‘father’, mamá ‘mother’, tio ‘uncle’, and tia ‘aunt’), the Rapa Nui terms koro and nua are retained and often used to refer to grandfather, grandmother, and other older Rapa Nui persons in Rapa Nui as well as Rapa Nui Spanish speech. See Texts 5 and 6 for uses of mama, nua, koro, and komaere ‘co-mother’.

Mario's use of uta ‘inland’ with the word-initial glottal stop (a phoneme in Rapa Nui but not in Spanish) is deleted points to Spanish interference, similarly to the case of Mariana's word choice of hore, possibly influenced by her knowledge of Spanish. The word-initial glottal stop is undergoing a process of allophonization and is often dropped by those speaking Rapa Nui as a second language, particularly those with lower productive competence. Similar influence from Spanish phonology occurs in the realization of the velar nasal

as a combination of alveolar nasal and velar stop, [ng], for example in the main village's name, usually written Hanga Roa. Similarly, but to a lesser extent, the Rapa Nui phonemic distinction between short and long vowels is allophonized. These changes are made more frequently by monolingual Spanish speakers or semi-speakers in Rapa Nui, but I have also observed them among bilingual Rapa Nui, especially when the Rapa Nui terms are embedded within otherwise Spanish discourse. These linguistic changes are thus apparent in synchronically observable variations.

Knowing that the truck was broken, Mariana quips in Chilean Spanish that going to inland will have to be ‘by foot!’, causing a round of laughter. Mariana's speech acts in this short excerpt reflect her highly developed passive knowledge of Rapa Nui. Furthermore, she is able to use Rapa Nui words to create Rapa Nui Spanish utterances and to use style-shifting much in the same way that adults codeswitch between Rapa Nui and Rapa Nui Spanish.

The asymmetry in bilingual acquisition patterns and competences that exists between R1S2 and R2S1 learners provides an obvious starting point for explaining the differences between R1S2 and R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish. Thomason & Kaufman (1988:14) argue that, although “any linguistic feature can be transferred from any language to any other language,” the characteristics of interference (structural vs. lexical) between two languages in contact depend on speakers' relative degrees of competence in the two languages. Just as in first language acquisition, in second language acquisition lexicon comes before grammatical structure, and thus structural (or grammatical) interference – such as transfer of grammatical morphemes and word order – requires greater knowledge of the language from which features are transferred (the “donor” language). Two types of relationship between the donor and the recipient languages can be distinguished. First, in the transfer of features from the speakers' dominant language (L1) to the second language under acquisition (L2), structural transfer tends to precede lexical transfer. Second, in the adaptation of L2 features into L1, lexical transfer precedes structural transfer. Rapa Nui interference in R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish exemplifies the first type: Structural features of the speakers' L1 (Rapa Nui) are transferred into their L2 (Spanish), originally owing to their imperfect learning of L2 (e.g., phonological interference; see ex. 1). Rapa Nui interference in R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish exemplifies the second type, where lexical but not structural features of the speakers' L2 (Rapa Nui) are transferred into their L1 (Spanish). Spanish structural interference (e.g., phonological) within the Rapa Nui lexical transfers in children's R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish illustrates the first type. The kinds of interference in syncretic speech styles also exemplify the second type, where lexical as well as structural features are involved, reflecting the high level of competence in L2 held by the current native Rapa Nui speakers, the R1S2 speakers (e.g., exx. 10, 11, and 13).

Research in sociolinguistics and language acquisition has highlighted age and linguistic competence as factors in structural changes of a language in a contact situation. In a range of processes of language change, such as koineization (dialect leveling), second language acquisition, and creole genesis, the researchers point to adults as more likely to be “innovators” of new forms and children as “restructurers” (Slobin 1977:205) who tend to choose the less marked options available and thus regularize innovations through “linguistic focusing” (Kerswill & Williams 2000) or homogenization.31

See also DeGraff 1999, Kegl, Senghas & Coppola 1999, and Long 1990.

The ways in which R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish speakers often engage in codeswitching behavior are characterized structurally by having Rapa Nui commonly as the main matrix language.32

In relatively fewer cases, a “composite matrix language” can be observed, as illustrated in (10) and (11).

Children are encouraged to participate in Rapa Nui cultural and community activities and do so actively. The number and the scale of cultural activities has been increasing steadily in recent years in this community where heritage tourism and indigenous movements are important. The most important event for Rapa Nui cultural and linguistic maintenance and innovation, and the major tourist event of the year, is Tapati Rapa Nui (‘Rapa Nui Week’), celebrated annually since the late 1960s. Its success has led the event to become ever larger and more complex, and it is now celebrated with over two weeks of nonstop activities. Although originally modeled after a Chilean town festival, Tapati has since become distinctively Rapa Nui in its character. It involves hundreds of competitions in sports, music, and crafts such as singing riu (‘song’), performing kaikai (‘string figure poems'), weaving pe'ue (‘totora mat’), exhibiting takona (‘tattoo’), playing ’upa'upa (‘accordion’) and dancing the Rapa Nui-style tango. All are carried out to support and gather points for the two or three candidates for Rapa Nui queen of the year. An important qualification of a queen candidate is her Rapa Nui linguistic and cultural skills. Verbal arts in Rapa Nui are included, and the event encourages young people to learn Rapa Nui language and traditions. Planning and preparation take place months if not a year ahead of time and require a great deal of human and material resources which can be gathered only by mobilizing entire extended-family networks. Kinship and family ties are renewed and obligations are renegotiated among the participants, hundreds of whom must be recruited for each candidate to prepare for, and participate in, the competitions and presentations.

In addition, an increasing number of public events in the community include presentations by local school students, such as the annual national independence day parades, the local school's “day of the Rapa Nui language,” and musical troops' performances for tourists. Many of these presentations feature young children's performances in dance, song, and other Rapa Nui cultural performances. Even those performances that feature only adults are rehearsed in family compounds, with children typically involved. Such events are also shown on the local television station, along with images from other Polynesian islands. Through such active environments of Rapa Nui cultural construction, children directly and indirectly participate in the Rapa Nui community. Yet although they are adept and eager dancers and even singers in Rapa Nui performative arts, younger children tend to shy away from speaking in Rapa Nui.

Unequal linguistic competence in the two languages obviously constrains the kinds of bilingual simultaneity used by individual speakers and provides an explanation for the origin of the characteristics of speech styles. Such cognitive constraints alone do not, however, fully explain the actual use of bilingual simultaneities, since R1S2 features have persisted and spread beyond the removal of these constraints. Similarly, cognitive constraints do not explain children's choice of R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish over Chilean Spanish when speaking to other Rapa Nui. Rather than debate whether the Rapa Nui elements in R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish are instances of codeswitches or borrowing,33

The distinction between borrowing and codeswitching in characterizing singly occurring lexical elements in bilingual and multilingual utterances has been a subject of extensive debate in the linguistics literature, with the corollary evaluation of speakers' levels of bilingual competence, activation processes, and the status of the items within each language's lexicon (e.g., Myers-Scotton 2002; Poplack 1980). Codeswitching and borrowing form a diachronic continuum over which a word is adopted initially by a bilingual speaker and, through linguistic and social integration, becomes nativized to belong to the lexicon of the recipient language and is used by monolingual speakers of that language, while synchronic variation likely exists across instances of usage in a community where bilingualism is developing or language shift is occurring.

The ways in which adult bilingual speakers mix R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish, Chilean Spanish, and Rapa Nui in conversations involve various forms of bilingual simultaneity: grammatical interference, and what Muysken 2000 calls “alternation” as well as “insertion” types of codeswitching. Rapa Nui speech includes numerous Spanish words from legal, technological, and emotion terminologies and other semantic fields, whose borrowing and nativization is facilitated by the existence of a lexical gap (Makihara 2001). In contrast, children's R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish is limited to lexical insertions, primarily content morphemes (sometimes referred to as “open-class” words) and, in particular, nouns.34

The difference in language processing between content and system morphemes (also referred to as lexical and grammatical morphemes) is reflected in a wide range of language processes: their different statuses in first and second language acquisition order; their becoming the object of purism and other language planning efforts; and their frequency in language contact phenomena such as borrowing, codeswitching, and dialect-shifting. See Levelt 1989, Muysken 2000, Myers-Scotton 2002, Prince 1987, Silverstein 1981, and Thomas 1991.

Psycholinguistic research in bilingual language acquisition has also found that children in a bilingual environment develop an early metalinguistic awareness (e.g., Hakuta & Diaz 1985).

See Makihara (2005) for a discussion of the ways in which Rapa Nui words in children's Rapa Nui Spanish serve as contextualization cues, or “nonreferential and creative indexes” (Silverstein 1981), to establish their Rapa Nui voice and identity. Non-Rapa Nui long-term residents also engage in similar attempts at using a solidarity code, since the majority of them are not able to speak Rapa Nui at all but interpolate a few words that they know in their Spanish speech.

Rapa Nui children contribute to the construction and transformation of syncretic norms of interactional language use through unreciprocated language choice (e.g., see Text 5) and through their use of R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish, influencing the present and future characteristics of the community's speech style repertoire more broadly. Fluent Rapa Nui speakers (R1S2 speakers) have started to differentiate R1S2 and R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish in their linguistic repertoire. For example, in Text 6 above, the adult Rapa Nui speaker adopts R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish in her interactions with R2S1-speaking children, demonstrating speech accommodation and codeswitching. Upon hearing her niece's R2S1 utterance (line 4, which rephrases her cousin's previous Rapa Nui utterance on line 2), the speaker offers a repair in R2S1 (line 5) (see exx. 14, 15, and 17). Text 7 below provides another example of the use of R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish by a bilingual adult speaker addressing an R2S1-speaking young child, although this case involves more than mere rephrasing.

The conversation took place as four-year-old Uka, who has some passive knowledge of Rapa Nui, had been closely watching as her aunt Rotia combed and braided an older girl's hair before school. Adults around them had been speaking in syncretic Rapa Nui. Noticing Uka's curiosity, Rotia lovingly teases Uka by telling Uka's grandmother in Rapa Nui that Uka is standing like a guard watching to make sure she combs properly (line 1). As Uka leans forward and gets in the way, Rotia scolds her mildly in R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish, using Rapa Nui terms hahari ‘comb,’ pu'oko ‘head, hair,’ and

‘name’ (here ‘godchild’).

Lexicon is an area of language that is highly surface-segmentable and most available for metapragmatic awareness. This seems to explain the readiness with which Rapa Nui-Spanish bilingual adults adopt this style in addressing predominantly Spanish-speaking children, expecting perhaps that these children will understand their utterances better or that its use will contribute to teaching them the Rapa Nui language. Such a high degree of metalinguistic awareness of the distinctiveness of R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish is leading to substyle differentiation of this newer Rapa Nui way of speaking Spanish.

An important element in understanding younger Rapa Nui children's choice of Spanish in their performance of Rapa Nui identity is to see that their “acts of identity” (Le Page & Tabouret-Keller 1985) are shaped in part by their own assessment and evaluation of “communicative resources, individual competence, and the goals of the participants” (Bauman 1977:38) in formulating interpersonal communicative strategies within the context of particular speech situations. The target audience of the children's speech acts in R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish are the Rapa Nui adults present, and more generally the imagined audience of the Rapa Nui community. Ethnic identity formation and an active indigenous movement among old and young adults have clearly affected these children's awareness of shifting and permeable social and linguistic boundaries. Although they are constrained by lack of bilingual competence, they are able to approximate the symbolic function of Rapa Nui as the ethnic language (or its use in syncretic speech styles) by using Rapa Nui Spanish, thus appropriating Spanish as a vehicle of ethnic solidarity-based participation. The use of R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish speech styles as “a solidarity code” (Hill 1989) can be interpreted as what Bucholtz & Hall 2004 call “tactics of adequation,” which serve to establish sameness in terms of identification. Ethnic identification, in this case, is being established across a language-based distinction that had previously served to separate Chilean from Rapa Nui.

It is important to children that their messages be heard. Thus they prefer to speak Spanish. Even those few who are able to speak Rapa Nui prefer to use Rapa Nui Spanish instead of their nonfluent Rapa Nui to establish or retain authority to be heard and believed within family contexts. Instead of interpreting their preference for and choice of Spanish as reflecting a negative attitude toward Rapa Nui culture and language (particularly since there is little evidence to suggest such an attitude), I view the children's Rapa Nui Spanish choice as stemming out of locally managed conversational contexts and interpersonal power struggles within them. By marking their Spanish with Rapa Nui, these children are at the same time using and investing in their competence and constructing and claiming as theirs one of multiple Rapa Nui “voices” (Bakhtin 1981; see also Hill 1985), credibly foregrounding and performing their ethnic identity, and this in turn is transforming the ethnolinguistic identity of Rapa Nui. Their “speaking Rapa Nui in Spanish,” to borrow from Alvarez Cáccamo's (1998) phrase “speaking Galician in Spanish,” is an act of expression and participation, a display of their Rapa Nui identification and solidarity.

Meanings of linguistic elements and social identities are socially constructed and jointly produced. Accordingly, these children's speech acts are subject to the addressees' and other audience's evaluation. Positive evaluation, although largely implicit in bilingual Rapa Nui adults' continued inclusion of these children in Rapa Nui or in syncretic speech style interactions, leads to positive motivation for the children to cultivate their Rapa Nui Spanish. What might be called an ideology of inclusiveness in Rapa Nui identification is practiced in terms of language skills through the everyday inclusion of these children in linguistically syncretic interactions. Adults' own adoption of R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish speech styles in interactions with these children constitutes an explicit positive evaluation, acknowledging its unique linguistic characteristics, its social meaning, and the children's authorship. Adult Rapa Nui are aware of the ongoing language shift whereby many children are unable to speak Rapa Nui. Rather than essentializing their identity to the Rapa Nui language, the Rapa Nui are cultivating multiple voices of “identity work” – including those expressed in Spanish in communicating not only with outsiders but also among themselves.

The choices these children are making between linguistic varieties and their adoptions of new speech styles are helping transform the ways in which language differences are mapped onto social and ethnic identity differences. Language shift is a complex social process to which children actively contribute. Passive knowledge of Rapa Nui and the positive symbolic value placed on it are crucial to understanding these children's speech behaviors, which, albeit indirectly, contribute to authorize and legitimize the Rapa Nui and the Spanish languages in a new way.

I cannot yet predict if this new way of speaking Rapa Nui Spanish will stabilize, but an examination of its linguistic, cognitive, social, and interactional dimensions is important in understanding the complex process of linguistic and cultural change occurring in this community. An observer of the macro-sociolinguistic change that has taken place on Rapa Nui might remark on the ironic and “contradictory” way in which these children's linguistic choices, motivated by their wish to belong to their ethnic language community, are nonetheless contributing to the loss of their ethnic language. Yet, at the micro-interactional and semiotic level, these children are making rational choices to use their dominant language, Spanish, in interactions and in the performance of their Rapa Nui identity. When they become older, they may come to regret their weak Rapa Nui language ability, may wish to (re)claim it, and may realize that in order to make that happen they must make conscious efforts to speak Rapa Nui. Some older teenagers and young adults who grew up speaking Spanish and have become vigorously engaged in cultural revival movements are making that conscious effort.37

Similar patterns of the development of language loyalty among adolescents and young adults who relearn their parents' language have been discussed by Timm 2003 for “neo-Breton” speakers in France, by Dorian (1981:106–10) for East Sutherland Gaelic in Scotland, by Hill & Hill (1986:121–22) for Mexicano, by Waterhouse 1949 for Chontal Hokan in Mexico, by Hinton 1994 for indigenous languages in California, and by Garzon 1998 for Isletan Tiwa in New Mexico.

Map: Rapa Nui in the Pacific Ocean