Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2005

It has been claimed that gossip allows participants to negotiate aspects of group membership, and the inclusion and exclusion of others, by working out shared values. This article examines instances of gossipy storytelling among young friends during which participants negotiate self- and other-identities in particular ways. Participants are found to share judgments not only about others' behavior but also about their own behavior through particular processes of othering. A range of discursive strategies place the characters in gossip-stories (even in the category called “self-gossip”) in marginalized, liminal, or uncertain social spaces. In the gossipy talk episodes examined, social “transgression” might be oriented to as a serious matter and thus pejorated, or oriented to in a playful key and thus celebrated. This ambiguity – “Do we disapprove or approve, of this ‘bad’ behavior?” – means that in negotiating the identity status of “gossipees” liminality is constant. It is argued that othering, as an emergent category, along with the particular discursive strategies that achieve it, is an aspect of gossip that deserves further attention.We thank Jane Hill, two anonymous reviewers, and especially Nik Coupland for their most helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. To clarify the title, from ex.(1), you can pull is British English; in American English perhaps the closest expression to pull is get with, proactively set up a link with someone, probably a sexual one, probably only for one evening or night.

In this article we take stories, or narratives, told among friends during small talk (Coupland 2000, Coupland & Jaworski 2003) and examine the participants' involvement in these stories as instances of gossip. As a starting point, we take gossip to be talk about people and their personal lives that involves some kind of newsworthy element and some form of (usually) pejorative evaluation (Eggins & Slade 1997). Of course, gossip is not only constituted in the telling of stories but can also take the form of accounts or descriptions of people or events. Here, however, we focus on how narratives are used as a resource for gossip, and in particular on how the protagonists featured in gossip stories (we might call them the “gossipees”) become subject to processes of othering by the gossip participants, or “gossipers.”

Folk-linguistically, and in many scholarly definitions (e.g., Brenneis 1992), gossip is linked with “bad,” “nasty,” or otherwise highly critical talk about others, usually absent third parties, and with “women's” language (e.g., Dowling 2001, Guendouzi 2001). Following Statman 1994, Blum-Kulka (2000:213) cites the Hebrew disapproval of “the type of gossip called ‘bad tongue’ (leshon ha-ra), where derogatory yet accurate information is passed about non-present others.” But, quoting Arendt 1968, Blum-Kulka asserts that there is also a positive side to gossip, stressing its “humanizing functions.” Talking about other people, she claims, is “humanizing” in that it is part of our experience of building relationships, sharing with others, and ultimately becoming and being human. This positive perspective on the social functioning of gossip is supported by Eggins & Slade (1997:279), who cite Dunbar (1992:31):

By talking to one person, we can find out a great deal about how others are likely to behave, how we should react to them when we actually meet them, and what kinds of relationships they have with the third parties. All these things allow us to coordinate our social relationships within a group more effectively.

In his ethnographic study of Zinacanteco gossip, Haviland (1977:28) adopts a broad definition of gossip as “conversations about absent third parties.” Gossip is, for Haviland, a useful gloss which covers a wide range of conversational phenomena such as “news, report, slander, libel, ridicule, insult, defamation, and malicious and innocent gossip” (1977:28). He also emphasizes the ambivalent nature of gossip in that it creates nervousness and anxiousness, but also fascination: We may be “doubtful about the propriety of talking behind someone's back, but secretly eager to hear some deliciously awful tidbit” (Haviland 1977:29).

A body of work in the anthropological and sociological literatures establishes some perspective on the social function of gossip. Schneider 1987 sees gossip as a form of talk that is essentially information giving, with much of that information of a confidential or personal nature. Drawing on Gluckmann's (1963) work, Rysman 1977 suggests that gossip functions in at least two ways: as a means of identifying group membership and group boundaries, and as a sanctioning mechanism of moral policing. From this viewpoint, the strategic use of gossip is to debate moral issues, and to assess whether or not the group would sanction certain morally relevant behaviors. Although Rysman's paper specifically links gender issues and the term “gossip,” much of the literature takes a more general approach. Fine's (1985) article identifies three major approaches to the study of gossip: the functional, the strategic, and the situational. The functional approach suggests that gossip serves a particular social purpose. For Gluckmann (1963:31), gossip asserts collective values or establishes normative boundaries, the effect of this being to increase group cohesion. Similarly, Besnier 1989 talks about the need to create collusion between the participants in successful Nukulaelae gossip sessions (see also Haviland 1977). Rosnow's (1977) view of the social functions of gossip is broader. He describes informative gossip, which exists to “provide participants with a cognitive map of their social environment” (1977:159); but in addition, he discusses influential gossip, seen as a manipulative device which we use to gain access to and pass on information that we can use to further our own relational and material goals, and entertainment gossip, which he sees as something we engage in for mutually satisfying amusement. These types are not seen as mutually exclusive; Rosnow (1977:162) points to gossip that both entertains and functions to give information.

Suls 1977 and Yerkovich 1977 both view gossip as being strategically managed information through which we evaluate the social behaviors of others. Yerkovich (1977:192) indicates three factors involved in the process: familiarity of participants, congenial definition of situation, and moral characterization of subject.

Haviland (1977:5) goes as far as to make a “plea for the study of gossip in ethnography” (analogous to Austin's 1961 plea for excuses), making the argument that there is a strong connection between social actors' knowledge of their society and their ability to gossip – that is, to display this knowledge and thus make it accessible to researchers. Another reason that gossip (and excuses) should be rich sites of ethnographic data, according to Haviland, is that both “arise with departures from normality – a symptom of the general axiom that people find only such departures worth talking about” (1977:5), thus providing insights into the underlying moral and social order, categories, objects, and skills.

There has clearly been attention in the literature to the socializing functions of gossip (cf. Blum-Kulka's [2000] discussion of socialization, seen as achieved through negotiating cultural and familial norms in relation to the moral order). This emphasis on positive functions has also developed through feminist sociolinguistic work in the early 1980s. Apparently accepting gossip to be talk in women's domain, in an early major article Jones 1980 examines it as an all-female activity crucially and positively related to women's roles as wives, girlfriends, and mothers: “Gossip is essentially talk between women in our common role as women” (Jones 1980:195). Jones's work is followed up by Coates's (1989) study of all-female conversations (see also Coates 1996), in which gossip is linked with the notion of cooperativity, and with the aim of maintaining good social relations and displaying solidarity through shared goals and identities.

In contrast to Jones, Coates deemphasizes the idea that gossip is used to enact gender-specific roles (mothers, wives, etc.). Recently Coates 1999, 2000 has discussed female “backstage talk” (which would include gossip as we have defined it above) in terms of women “behaving badly” – that is, breaking the mold of the social stereotype that makes women out to be “nice.” Some of Coates's examples include women challenging the idea of the “maternal instinct” by claiming not only that they don't love all children, but that they actively hate some, including their own at times; expressing contempt for other people to whom they must speak respectfully, such as awkward customers in a shop where one of the women works; or admiring outrageous behavior of other women, such as one participant's mother's arrival at her ex-husband's funeral on a milk float.

Coates argues that women's derogation of self and others and their celebration of women's “bad” behavior (which is typically deemed to be “unfeminine”) are features of their “backstage” (private, secret, off-the-record) activities (Goffman 1971). The backstage nature of women's stories about their own and others' bad behavior is said to allow women to perform being “not nice,” otherwise proscribed for them by social norms. Men, claims Coates, are able to be “nasty” in “frontstage” (public, open, on-the-record) contexts. She cites Pilkington (1992:57), whose study of men's and women's strategies when gossiping together in small same-sex groups indicates that men saw verbally abusive behavior toward each other as positive, and polite behavior as negative: “Don't try to make out I'm nice,” says one of the men to another.

However, in the past few decades in mediated contexts, frontstage gossip by both women and men has gained a prominent place. On various public-participation, magazine, and “reality” shows on television, and in Internet chat rooms (cf. Fairclough's 1992 notion of “conversationalisation” of public discourse), gossip as a talk activity is joined by both genders. And recent work on gossip (in both the front and back stages; Pilkington 1992, Johnson & Finlay 1996, Cameron 1997) has attended to men's involvement. To take one example, Cameron 1997 analyzes an informal conversation among five American college students in the classroom “time-out” situation, who enact their male, heterosexual identity by engaging in a disparaging exchange of opinions about other, mutually known men, as “gays.” In this specific instance and frame of talk, references to “gayness” are largely ritualistic, boundary-marking activities, as the classification of people as “gay” in their conversation is focused mostly on disapproved items of clothing (cycling shorts, socks) and has little to do with the known or suspected sexuality of the objects of their gossip. However, displaying hostility to gay men is a way for these conversationalists to establish their preferred version of their own (heterosexual) masculinity in this particular context of an all-male peer group, by othering those with dispreferred self-presentational habits.

These studies evidence the function of gossip in building group identity and boundary marking. In Cameron's study, the gossiping men construe other men as “gay,” not quite “real” men, or men who do not display “normal” manly conduct and therefore are to be pejorated (cf. above-mentioned reference by Haviland 1977 to gossip as “departure from normality”). The women in Coates's studies create distance between themselves, or the protagonists in their stories, and the traditional models of femininity, and they celebrate that distance. In each case, gossipees' or protagonists' identities are rendered uncertain or ambiguous in relation to social categories such as gender: hence unmanly men (“gays”) or unfeminine women (“badly behaved”). Such ambivalent and, as a consequence, newsworthy or tellable (Coates 2003) positioning of subjects is what we refer to as “othering.” This is an aspect of gossipy talk that deserves but has not yet received sustained attention, and it is to this we turn in our analysis of gossip episodes below.

Our data sample is derived from approximately 60 audio-recorded conversations collected by undergraduate students enrolled in the undergraduate course “Men, Women and Language” taught by Adam Jaworski in Cardiff in 1997–1998. The students were asked to record their own conversations with their friends, housemates, or family members in the casual, leisurely context of their own student or family home. The recordings were then used by the students for analysis in their own assignments on aspects of gender-related communication. The students were also asked whether they would be willing to deposit copies of their recordings with their tutor for his use in research. They were assured of the sole purpose of collecting the recordings from them and about the confidential treatment of the tapes. Only one student refused to donate her recording to the collection.

The students were predominantly female, in the 18–22 years age bracket. Most of the recordings were made in student homes in Cardiff among housemates/friends. Some were made in students' parental homes between students and their family members or among friends, usually in dyads and triads, talking during their leisure time – over drinks, cooking or eating, watching television, or getting ready to go out for the evening. In each case, the recording was made by one of the conversationalists. All names in the extracts below are pseudonyms.

Our aim in this article is twofold. First, we want to demonstrate that our student friends' storytelling contains “gossipy episodes” that focus largely, although not exclusively, on derogatory/disparaging gossip, and to a lesser extent on celebratory gossip. We follow earlier studies (notably Eggins & Slade 1997) in claiming that this type of activity allows participants jointly to accomplish group solidarity and to strengthen group identity. But second, we argue that if gossip achieves social cohesion through (mostly pejorative) evaluation in the storytelling, it does so by specific processes of “othering” whereby the protagonist in the gossip-story, or gossipee, is subjected to imposition of a borderline or liminal identity. We aim, then, to trace the discursive strategies of othering in gossip.

Hall 1996 claims that the foremost instrument for the construction of one's identity is invoking difference. With references to Derrida 1981, Laclau 1990, and Butler 1993, Hall states that “it is only through the relation to the Other, the relation to what it is not, to precisely what it lacks, to what has been called its constitutive outside that the ‘positive’ meaning of any term – and thus its ‘identity’ – can be constructed” (Hall 1996:4–5). Identity construction is then an act of drawing boundaries and creating exclusion zones through the process of “closure” (Bhabha 1994, Hall 1993). Hall illustrates this by referring to such contrasts as “white” being defined by “black” (and vice versa), “day” being defined by “night,” “masculine” by “feminine,” and so on. Thus “us” vs. “them” is realized through a simple contrast or difference between such entities as man/woman or black/white. However, Hall 1997 conflates “difference” and “otherness,” arguing that both are endowed with inherent ambivalence. He cites examples from the British press that represent top black athletes simultaneously as “heroes and villains” (winning gold Olympic medals and taking drugs), or as “superhumans and animals” (winning medals and being likened to gorillas).

Riggins 1997a uses the designation “other” (or “others”) in a similarly dual fashion. He argues that others are members of different ethnic groups, opposite sexes, and different ages, residents of different regions (such as New Yorkers or Californians vs. Midwestern Americans), conservatives and Marxists, tourists and natives, and so on. These relations are typically understood as distinctions between the type self and the external other, I and You, We and They. The second meaning of the term “other(s),” which is dominant in Riggins's discussion, is that of a stereotyped, dehumanized, diminished, inferior, odd, irrational, exoticized, and evil other, an other which is also possibly desired, not least through eroticization (see also Hall 1997, Said 1978).

This conflation of “difference” and “otherness” is problematic, and we want to distinguish between identity-building based on the difference between self and non-self (of the day/night variety), and othering. The former is based on simple binary systems of oppositions and can be glossed as the preserve of autonomy. Self and non-self are different because of their separately embodied subjectivities. Othering, in contrast, occurs when an individual or a group of people is denied a clearly defined status – for example, when an individual or a group is designated as “anomalous,” “peculiar,” or “deviant,” or is objectified, stereotyped, naturalized, or essentialized (as discussed in Hall 1997 and Riggins 1997a; see also contributions to Riggins 1997b, Blommaert & Verschueren 1998, Valentine 1998).

Othering can be linked, then, with the social anthropological tradition of work on classificatory systems (Hall 1997 also makes this link with references to Douglas 1966). In her overview, Babcock-Abrahams 1975 states:

Since any description of the world must discriminate categories in the form “p is what not-p is not” (Leach 1964 and 1969), and since every category system is based on the principle of difference, such primitive logic is seen as intrinsically binary. But, as Leach points out, if the logic of our thought leads us to distinguish we from they, how can we bridge the gap and establish social, economic, and sexual relations with the others without throwing our categories into confusion? The usual answer is that mediation is achieved through the introduction of a third category such as amphibian, which is ambiguous or anomalous in terms of the ordinary categories of land and water animals. Such abnormal middle forms are regarded as dangerous and powerful and are typically the focus of taboo and ritual observance (cf. Leach 1969:10–11). (Babcock-Abrahams 1975:169)

Further, Leach 1976, 1982 argues that, in a world structured in oppositions of this kind, humans attach the status of “normality” to everything they perceive as simple, intelligible, and logically ordered, in contrast to the “abnormality” of that which is disorderly and unintelligible. The perception of a feature as normal or abnormal is never a question of “objective” fact, but of the circumstances in which it is observed; for example, “sexual activity, which is in itself a normal part of normal life, can suddenly become abnormal when it is classified as ‘dirty’” (Leach 1982:115). And it follows: “Whatever is felt to be abnormal is a source of anxiety. Abnormalities which are recurrent and frequent become hedged about by cultural barriers and prohibitions which have the force of signals: ‘Danger; keep out; don't touch!’ Breach of such prohibitions constitutes the prototype of moral evil; the essence of sin is disobedience to a taboo” (Leach 1982:115).

We can argue, then, that the status of other persons or groups can be altered or manipulated depending on whether we want to represent them as “same” or “different.” In either case, identity is definite, unambiguous, and clear. It does not cause anxiety and maintains the status quo. However, the identity of a person can be altered so that he or she will be perceived as someone who belongs neither to “us” nor to any accepted, normal, and unambiguous “they”; such people can be thought of as “outcasts,” “rejects,” “freaks,” and so on. In fact, as Thurlow (2001:32) observes, the word “gay” is the most common term of homophobic abuse in British schools, yet “this is ironically the very word that many young homosexual people will more than likely be choosing to use to describe themselves.” “Gay,” then, can be used both for clear self-identification and for othering.

The main reason why it is possible to redefine one's status and, even more important, to make it anomalous is that social boundaries have fuzzy edges. Consequently social concepts overlap, and these overlapping areas are by definition ambiguous. Following the examples quoted by Leach, such entities as “Man” and “God,” “Life” and “Death” involve intermediate concepts, respectively, of a mediator, “a god-man towards whom all religious ritual is addressed and who is thought of as the source of metaphysical power” (Leach 1977:17), and “sickness where the individual is neither altogether alive nor altogether dead” (Leach 1977:17–18).

The individual's ambiguous status can also be manipulated depending on the situation. Leach illustrates this point with the example of “criminals” and “policemen,” who both have an abnormal status because they represent an intermediate state between the society at large and its individual members. “Criminals” can be said to be the mediators between the society and its members defined as “rebels,” while “policemen” (“heroes” or “rulers”) mediate between the society and the ruled. In the act of breaking into a private house by a criminal or by a policeman, for example, the treatment of an individual as a criminal or a policeman “will depend, not on the facts of the case but what we believe to be the case with regard to the legitimacy of the situation” (Leach 1977:16). Thus, Leach's category of taboo does not always involve negativity of status. Gods, royals, policemen, and in some cases also the devil, rebels, and criminals can be revered, admired, and emulated, yet they remain inaccessible, remote, and marginalized.

A useful example of the discursive manipulation of the boundaries of self and non-self and of othering is Neuman, Bekerman & Kaplan's (2002) study of the rhetoric used by an Ultra-Orthodox rabbi, Uri Zohar, in a speech addressing an audience of Sephardi Jews in Pardes Katz, a poor suburb of Tel Aviv. The main aim of the speech was to convert Sephardi Jews, who are non-Orthodox but positively oriented to traditional Judaism, to an Ultra-Orthodox way of life. In doing so, Rabbi Zohar blurs the religious distinction between self (Ultra-Orthodox) and that of his audience (non-Orthodox) along three other dimensions: (i) moral (sacred vs. unsacred), in that he names Pardes Katz as a place where “sacredness dwells”; and (ii and iii) ethnic/economic, in that he contrasts the good reception he enjoys among the low-income Sephardi Jews with the hostility of the affluent, predominantly left-wing, liberal Ashkenazi Jews. Rabbi Zohar and his Sephardic audience share right-wing political views and aversion to non-Jews, mainly Arabs and Americans. It is by othering secular Jews and non-Jews that the rabbi further creates a sense of unity with his audience:

First, the secular Jew is associated sociologically with Ashkenazi Jews from the upper class. This “type” of Jew is clearly not the appreciated model of the audience not only because of the different socioeconomical character, but also because it is presented as having “left wing, humanist” opinions manifested in a political caricature that wants to “give half of the land of Israel to three quarters of it to the Arabs,” and this type also supports interracial marriages of Jews and gentiles (“Hundreds of Jewish girls marry Arabs”)… . Moreover, on the personal rather than the socioeconomical level, the secular Jew is presented as “Mindless.” … The non-Jew is described with emotionally loaded terms and is portrayed as saturated with sins … the use of the sign “dirt” in its various senses (e.g., impurity, filth, etc.) is the most common symbol for describing the non-Jew, whose representatives in the speech are Christians and Americans. For example, in comparing the Jews to the non-Jews, Rabbi Zohar describes the non-Jews as primitives who climbed on trees like monkeys when “you [the audience] had Isaiah and Jeremiah the prophets.” Describing the non-Jews as monkeys relates to the portrayal of the Americans as beasts and insects and the portrayal of the Pope as the mythical serpent. (Neuman et al. 2002:106–107)

In this example, othering involves construing identities through the use of marked register (e.g., humor, parody, caricature), naming/labeling which symbolically dehumanizes the referent (“monkeys,” “insects,” “beasts,” “serpent”), and accusations of stupid, irrational behavior (e.g., giving land and women away). The Other is impure, sinful, and dirty and threatens to pollute “us.” Just as “dirt” is “matter out of place” (Douglas 1966:48), the Other is a person out of place.

In the next section, we work toward characterizing the discursive strategies used for othering in stories involving gossipy events. The starting point for our textual analysis is N. Coupland's (1999) formulation of the descriptive categories of “‘other’ representation,” although our view of the other is slightly different from his, which is more firmly rooted in intergroup theory (Tajfel & Turner 1979), suggesting that the other is “not only different or distant but also alien and deviant” (N. Coupland 1999: 5). In our view, othering need not apply to out-group members only; it can also apply to in-group members and self, for instance in self-mockery). We agree with Coupland that “othering is the process of representing an individual or a social group to render them distant, alien or deviant” (emphasis in original) and that it “raises issues about group boundaries” (1999:5), but not so much by making these boundaries clear as by blurring them to provoke anxiety or excitement.

Coupland 1999 discusses five general discursive manifestations of othering: homogenization (stereotyping), pejoration (typically represented by various terms of verbal abuse, racial slurs, etc.), suppression and silencing (e.g., omission, selective representation), displaying “liberalism” (e.g., hedging racist remarks by claiming nonprejudicial intent), and subverting tolerance (e.g., ridiculing “political correctness,” humorous, parodic mockery of minorities). Focusing for the most part on the disparaging and minoritizing aspects of “other representation,” Coupland also flags the possibility of nonstigmatizing instances of “other representation,” including “self-othering” and subverting hegemonic (e.g., racist) ideologies (see also Simmel's 1971 notion of the “stranger”; and Riggins 1997a). He also emphasizes “other representation” as context-bound and interactionally emergent. What we propose to do in this article, then, is to apply and extend Coupland's framework to analyze othering in locally managed interaction. We demonstrate that othering is a strategically deployed resource for the regulation of interpersonal distance between interactants and third parties in casual conversation, operating momentarily, usually at very short intervals/stretches of talk. Although, for the most part, our data manifest othering of individuals rather than of groups, and as a negative rather than a positive typing, we also identify instances of positive othering, othering of a durable rather than short-lived nature, and instances of talk that could have led to instances of othering but did not, for particular salient reasons, as we will show.

In the analyses that follow, we trace patterns of othering in gossip over quite lengthy episodes of talk in order to be able to direct sustained analytic attention to the complex identity work (Eggins & Slade 1997) the participants manage together.

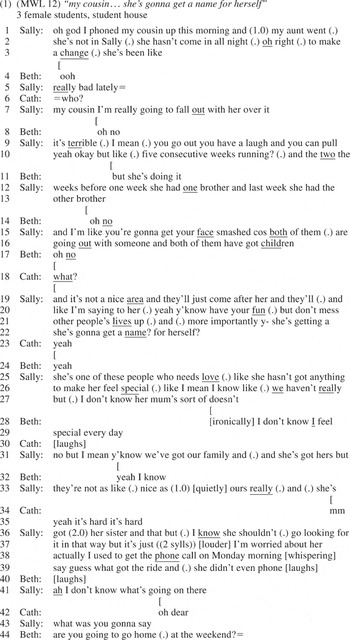

This talk episode is arguably an archetypal instance of the genre of gossip, with the sociocultural functions of moral policing and reinforcing group norms (Gluckmann 1953, Eggins & Slade 1997). The narrative is framed by more general small talk, with the behavior of Sally's cousin reported, elaborated upon, and scrutinized; the three women together cooperate to establish and reinforce pejorative evaluation. The gossipee is a cousin of Sally, the teller, and so through family ties, “like” the teller, and vicariously “known” by Beth and Cath, therefore with potential to be treated as an in-group member. Instead the handling of the gossip clearly marginalizes the cousin (see especially line 7). Close analysis of the episode enables us to examine the particular discursive strategies employed in the pejorative evaluation and concomitant othering of the cousin.

Sally starts the gossipy event with a formulaic interjection, oh god (line 1) signaling a strong emotional investment in what is going to follow (cf. Heritage 1984, Schiffrin 1987 on the meaning of oh); the interjection also functions here as a formulaic marker of a new performance (Bauman 2001 [1975]). She immediately proceeds to the disclosure of the “trigger event,” the phone call made by Sally and the news announcement by her aunt on line 2, she hasn't come in all night. The teller registers her shock (and subsequent cynicism) through reported speech, oh right (.) to make a change. The evaluation of the gossipee's behavior, already instigated in make a change, is made more explicitly pejorative in she's been like really bad lately (lines 3–5). At this point in the narrative, the recipients, Beth and Cath, are unfamiliar not only with the story but also with its protagonist (cf. Cath's who? on line 6). But Sally already orients to “othering” her cousin, not just in the framing of the narrative but more generally in her projected relational distancing owing to her bad (line 5) behavior: I'm really going to fall out with her over it (line 7). The pejorative evaluation (line 9) it's terrible is accelerated in lines 9–10 when Sally claims the moral high ground by rehearsing what is apparently her position on “normal” or acceptable behavior for her in-group as she sees it: you go out you have a laugh and you can pull yeah ok but like (.) five consecutive weeks running? At this point we see the onset of display of group consensus, with Beth, presumably picking up on what Sally has said on lines 3–5, overlapping but she's doing it (line 10), clearly implying agreement with Sally's evaluative stance.

Lines 9–10 and 12–13 comprise the disclosure of “substantiating behavior” (Eggins & Slade 1997:285: “The speaker describes an event which highlights some departure from normality … this is then used as a hook on which to hang the evaluation”). The claim in lines 12–13 – one week she had one brother and last week she had the other brother – works to justify Sally's appraisal of the other's behavior as terrible (line 9). And on line 15 she progresses the gossip by reporting her speech to the “other” – I'm like you're gonna get your face smashed and adding further information to account for making this prediction: the cousin's sexual partners have complex existing relationship commitments. The performed disbelief in Beth's oh no (lines 14 and 17) and Cath's what (line 18) now confirms the group consensus on how unacceptable they find the cousin's behavior.

But on line 19, when Sally turns to discussing the consequences of her cousin's actions, there is a shift from othering the individual, the cousin, to othering the group the cousin has come to be involved with, defined by the geographical/social class/symbolic space they are construed to inhabit. Line 19, it's not a nice area and they'll just come after her, takes the narrative into imagined aberrant revenge by those living in the not…nice “othered” space. Again, on line 20, Sally uses reported speech, now to claim the right to evaluate and advise the other, apparently voicing in-group norms (have your fun) and how they have been broken – but don't mess other people's lives up (a similar pattern, it would seem, to lines 9 and 10).

Of course, one of the most powerful mechanisms of othering is labeling or categorization, implicated by Sally on line 22: more importantly … she's gonna get a name for herself. The “name” she refers to does not need to be made explicit in this context.

On line 25, we see a shift in the way that othering is oriented to by the group. Some display of “liberalism” work begins (cf. also Eggins & Slade's 1977: 297 related notion of “concession”) with Sally accounting for her cousin's sexual transgressions in ostensibly more sympathetic terms. However, the liberalism is achieved via homogenizing: she's one of these people who needs love. And even as this display of liberalism toward the cousin is played out, the cousin's immediate family are “othered” by contrast with the families of Sally, Beth, and Cath. The in-grouping (still, notably, homogenization) implicit in our family (line 31) and as like (.) nice as (1.0) ours (line 33) nicely points up the comparison. Cath's response on line 35 also shows this liberalism (yeah it's hard it's hard). Finally, Sally makes a statement that acknowledges the aberrant behavior – I know she shouldn't (.) go looking for it in that way (lines 36–37) – and indicates the problematic nature of the liminal space she has thus “earned”: I'm worried about her actually (lines 37–38). This may be facework done to mitigate the earlier pejoration, but the effects in terms of out-grouping and in-grouping are much the same. The final comment before the topic is left serves to confirm the uncertain and ambiguous nature of the cousin's behavior in the comment about uncertainty on line 41, ah I don't know what's going on there. We might interpret this exchange as a clear example of young women negotiating and reconfirming what appropriate and acceptable sexual behavior for their group might be, and performing and therefore acknowledging the sanctions (attracting othering talk) that this may bring.

Ex. (1) represents talk on issues such as family solidarity and support and sexual and social reputation where the othering is oriented to as quite a serious matter. Ex. (2) also evidences gossip and pejorative evaluation, but we interpret this othering more as play. Nevertheless, the discursive strategies used to frame, establish, and sustain the othering are quite similar.

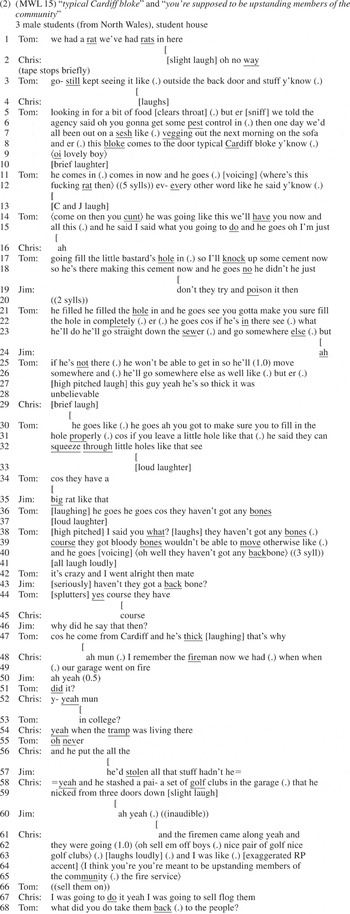

Ex. (2) provides two clear examples of gossip storytelling with pejorative evaluation. From early in the first storytelling, the identity of the gossipee is marginalized (line 8). First this is achieved through categorization and homogenization, in the gossiper's framing of the story: this bloke comes to the door typical Cardiff bloke y'know. So here we have three young men from North Wales sharing a story about, and out-grouping, a Cardiffian, a form of Welsh snobbery (Garrett, Coupland & Williams 2003). As it turns out, the story portrays “Cardiff bloke” as uneducated, or at least stupid, a working-class city-dweller with a menial job – in a story told by an undergraduate with rural origins. The marginalization is sustained by use of voicing, with the teller's very fast tempo of speech, high-pitched voice, louder than normal (line 9) or softer than normal (line 11–12) volume, as well as shifting to broader, generalized Welsh accent and dialect forms such as oi lovely boy (line 9) and where's this fucking rat then (lines 11–12). The voicing here has the teller momentarily “becoming” the caricatured other he describes, and therefore occupying a liminal identity-space for the performance, a phenomenon that recurs in the story about the firemen following the one under discussion (see lines 62–65).

In the first story, the gossiper discontinues the voicing from line 15, although he continues the gossipy storytelling frame and the use of quotatives toward the end of line 18, which is picked up again toward the end of line 26 (until line 47). In these stretches of talk, however (e.g., lines 14, 15–17), the quotatives are not heard as voicing. Here, Tom uses fewer mimetic props, “devices that aid directly in imagining the story world” (Clark & Van Der Wege 2001:779), to mark the quotatives as instances of voicing approximating his normal speaking voice (most notably, there is no perceptible shift from his own base accent, with only some pitch and volume modulation). Between lines 18 and 26, in response to Tom's question don't they try and poison it then? (line 19), Tom switches away from the gossipy frame to a factual, explanatory frame signaled by a shift to his normal tone of voice, including all the instances of reported speech (cf. lines 21–23).

Up to line 12, if there is pejorative evaluation it is implied, although the nature of Chris's and Jim's laughter arguably indicates derision; but on line 12, Tom begins to provide the supporting evidence (Eggins & Slade 1997) of aberrant behavior, first in the frequency of his use of taboo language, which is marked as newsworthy – every other word like he said y'know (.) come on then you cunt he was going like this.

As the story of “Cardiff bloke's” actions and reasoning is reported (lines 15–40), Jim indicates (line 19) his confusion over the course of action being taken; at this stage he has not made the inferences necessary to “other” the protagonist. But Tom narrates Cardiff bloke's (aberrant) behavior (lines 21–32), embedding a pejorative evaluation and hyperbole on lines 27–28: this guy yeah he's so thick it was unbelievable. This derision of Cardiff bloke is clearly a source of enjoyment; evoking loud, repeated, and prolonged laughter over several turns. This is not oriented to as a serious matter, but the laughter and the ridicule it signifies are another way of achieving othering. This “other” is not a villain but a dope. And the climax of the story is reached on line 36 when the other's claim that rats haven't got any bones (again, expressed through voicing marked by hysterical laughter and extreme loudness) leads, on lines 38–39, to the gossiper's reported speech to the man ostensibly doing face-to-face othering: I said you what? … course they got bloody bones wouldn't be able to move otherwise like. We cannot, of course, be sure of the veracity of the reported exchange. However, that Tom chooses to represent it thus clearly works to mark off “Cardiff bloke” as ostensibly othered at the time of the storytelling event.

Note that, unlike in (1) where the victim of the gossip is ostensibly treated with some tolerance after the pejorative evaluation, there is no display of liberalism toward “Cardiff bloke.” Liberalism is instead offered to one of the group members, Jim, who reproduces the same position of ignorance that has just been ridiculed on lines 37 and 41. Tom and Chris now withhold or suspend ridicule. The response to Jim's question on line 47 – cause he come from Cardiff and he's thick – momentarily equates Cardiff with being thick (using homogenization and pejoration), but it spares Jim from being ridiculed and othered by his friends.

Chris now offers another story, linked to the first by the theme of odd, unacceptable or aberrant behavior, beginning on lines 48–49. The “tramp” living in the garage and filling it with stolen goods is unambiguously “different” from the presumably law-abiding family living in the main house, therefore out of place in the family's garage; and Jim, at least, indicates that he has heard about the tramp before (see line 57). But the firemen's behavior is worthy of more prolonged gossip. The teller uses voicing to “other” the firemen, who notably are represented as speaking with one voice, and thus further homogenized (lines 62–63). He shifts to a more markedly North Walian accent (local to his home, then): oh sell em off boys (.) nice pair of golf nice golf clubs. When he reports his own response in the story-time, he performs audible accent-divergence by shifting “up” to Received Pronunciation and therefore “away” from the performed regional accent of the firemen, and continuing to shift “up” in this direction through the turn: I think you're you're meant to be upstanding members of the community (.) the fire service (lines 64–65). The firemen “are” or “should be” respectable, doing a respected job as members of the emergency services, in this sense being liminally heroic, but they do not behave respectably when they propose criminal activity and therefore occupy a liminally villainous space, equally or even more newsworthy and worth remarking on. The teller's performed “proper or respectable” persona, represented by voicing RP, ostensibly albeit momentarily distances himself from the firemen-as-other/s. But on line 67, the teller rescinds this “proper” position by disclosing in his very next turn, I was going to do it yeah I was going to sell flog them. In the performance of the gossip at least, there is identity fluctuation here. Chris positions himself within moments as performing the role of good citizen, expressing disapproval of the firemen, and the role of an inferrably hard-up student tempted by criminal money-raising. On two occasions in this extract, then, we have seen participants putting themselves potentially into liminal spaces: On the first occasion, after Jim's ill-informed questions on lines 43 and 46, his friends resist othering him by glossing over his ignorance; and in the second, Chris, even as he flirts with criminality, rejects it (cf. was going to sell flog them).

In the following extract, we see further evidence of an interactant talking himself into a liminal space by the way the stories are told.

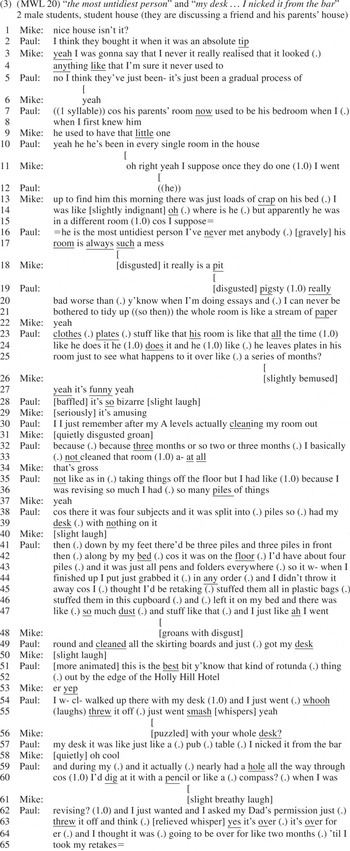

The initial othering in this talk episode (in the gossip about the “most untidiest person”) is not achieved through conventional storytelling. It begins on line 13 with an indication of the friend's nonconformist behavior: there was just loads of crap on his bed. Paul signals consensus to Mike by giving, in turn, his own evaluation of the other's aberrant behavior: he is the most untidiest person I've never met anybody (.). The evaluative markers they both use are explicitly pejorative: it really is a pit (line 18) pigsty (1.0) really bad (lines 19, 20). Othering is also achieved through comparison of own with the other's norms of behavior: worse than (.) y'know when I'm doing essays (line 20); his room is like that all the time (line 23). Next comes the substantiating behavior (Eggins & Slade 1997:285) with specific exemplars to justify pejoration: like (.) he leaves plates in his room just to see what happens to it over like (.) a series of months? (lines 24–25). However, both the set of evaluation markers that follows (funny, line 27; bizarre, line 28; amusing, line 29) and Paul's upcoming story indicate the ambiguous nature of the interactants' attitudes toward this liminal or marginal behavior: Is it to be derided or lauded?

From line 32, Paul begins othering the self. Between lines 32 and 47, he tells a story about his own room and its untidiness, though he justifies this by adding that this was after my “A” levels (line 30); I was revising so much I had (.) so many piles of things (lines 35–36); at the same time, though, he denies conformity in I didn't throw it away cos I thought I'd be retaking (lines 44–45). The story about the desk, which follows, discloses some morally or ethically questionable norm-breaking and therefore might be described as “self-gossip.” This is, however, notably framed by this is the best bit (line 51; cf. Coupland & Jaworski 2003). This “announcement” clearly construes the bizarre behavior he is to report as comprising a good, newsworthy, tellable story and therefore worth some conversational capital (Bourdieu 1991, Rosnow 1977): I … walked up there with my desk (1.0) and I just went … threw it off (.) just went smash (lines 54–55). The recipient's audible reaction to this confirms the counternormativity of what has just been told: [puzzled] with your whole desk? (line 56). Interestingly, the self-justification that Paul provides refers to other nonconformist, even criminal behavior: it was like just a (.) pub(.) table (.) I nicked it from the bar (line 57).

Paul, the teller, is othering himself by constructing an ambiguous or liminal self-identity in this story. He steals a table, systematically damages its surface (I'd dig at it with a pencil or like a (.) compass? line 60), and finally destroys it. This is a story framed by deep conformity. The desk is used for A-level coursework revision, and Paul tells his listener I asked my dad's permission before he jettisoned the table from the cliff (line 62). The nature of his bid to portray his behavior as liminal is clearly indicated by the positive gloss of this is the best bit (line 51). In turn, the positive evaluation from Mike, the hearer, oh cool (line 58), and his laugh on line 61 confirm that such (albeit mildly) aberrant behavior is to be endorsed. This is indeed a very ambiguously told, mitigated form of morally questionable behavior, and the evidence is that by the end of the story both teller and recipient orient to the teller's othered position as somewhat heroic, meriting celebration or admiration.

One common and nearly inevitable othering strategy present in all the three extracts presented here, with regard to the others-not-present – the “cousin,” “typical Cardiff bloke,” “firemen” and “the most untidiest person” – is silencing (cf. Jaworski 1993). This cannot, of course, be demonstrated in the extracts, but it is quite clear that all these “gossipees” cannot answer the accusations made or account for or mitigate marginalized behavior simply because they are not physically present and therefore are denied access to a voice during the gossip episode. However, where the stories involve or in some way implicate those present, there is discursive opportunity to negotiate a satisfactory identity outcome by suppression or withholding of pejoration (as in ex. 2) or by celebrating marginal behavior (as in ex. 3).

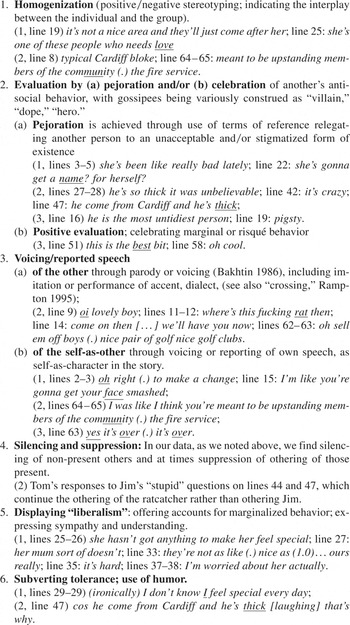

We have traced the following features of strategic othering, proposed by N. Coupland 1999, as they appear to be handled by participants of gossipy storytelling. Our analysis has included some instances of what Coupland calls “non-stigmatising instances of other representation, including self-othering,” but we have found that in the telling of such stories, these instances may be in fact not only nonstigmatizing but actually celebratory. In the list of othering categories below we give some examples, from our data, of each type, which also enable us to review the particular strategic patternings we have uncovered.

In our discussion of “difference” and “othering” above, we followed several authors (Hall, Riggins, N. Coupland) in characterizing the latter term as construing individuals or groups as anomalous, alien, and deviant. The overarching characteristic of othered people, then, is their perceived or imposed ambiguity and norm-breaking. In line with others before us, we also believe that “othering” and gossip are discursive means of asserting and reinforcing group coherence and identity. However, what we propose here is that these functions are achieved not so much by clear boundary marking as by playing with and negotiating around the unclear, fuzzy edges of social categories, norms, and acceptability. For example, in (1) the gossipers position Sally's cousin as an anomalous family member, and in (2) Tom positions the pest-control man, an out-group member who comes into Tom's student house in Cardiff, as anomalous in that social environment, with his status as Cardiffian, for the purposes of the gossip, associated with his limited intelligence. In (3) the living habits of the “most untidiest person” are different enough from those of the two gossipers for the gossipee to be adjudged “bizarre.”

In this sense, our analysis of identity construction in gossipy acts of othering shares some significant points of contact with the model of identity based on intersubjectively negotiated practices and ideologies that has recently been proposed by Bucholtz & Hall 2004a, 2004b. Building on a long tradition of work in social psychology and linguistic anthropology, these authors emphasize the relational, emergent aspect of identity in terms of three pairs of tactics of intersubjectivity, which we summarize all too briefly here. The first pair is adequation, processes that reveal “sufficient” intersubjective similarity, and distinction, processes of social differentiation (2004a:494). The second pair is authentication, the construction of a “true” or veridical identity, and denaturalization, the foregrounding of untruth, pretense in identity positioning (2004a:498). The third pair is authorization, the use of power to legitimate certain social identities, and illegitimation, the withholding of such validation from particular identities (2004a:503). These tactics form continua alongside three intersecting dimensions of identity formation: sameness vs. difference, genuineness vs. artifice, and institutional recognition vs. structural marginalization (2004a:494). To illustrate some of our points of contact with Bucholtz & Hall's theoretical positioning, then, with their terms in italics below, Sally's cousin can be said to be symbolically separated from Sally's family by engaging in the sort of behavior that is sufficiently different from Sally's family's and friends' (Beth and Cath) norms (distinction), but she is not construed as distinct enough to become an outcast. In other words, the emphasis of Sally's cousin's difference from her in-group stops short of her being ideologically constructed through the erasure of any likeness between her and Sally's family. Rather, she is portrayed as temporarily straying into the aberrant social space of another social group in not a nice area (1, line 19) but later reclaimed in I'm worried about her actually (1, lines 37–38), which we might see as exemplifying adequation, bringing her back symbolically as a legitimate in-group member.

Likewise, the pest-control man is not just some out-group member who provides a simple contrast for the identity of the young, North Walian university students. He comes to the door while “we” are vegging out the next morning on the sofa (2, line 7), thus encroaching on the students' territory. Unable to avoid contact with the man and not prepared to accept him as part of the in-group, Tom not only highlights the man's distinctiveness as an out-group member but also denaturalizes his subjectivity in a blatant act of essentializing through stereotyping and disparaging parody: typical Cardiff bloke y'know (.) 〈oi lovely boy〉 (2, lines 8–9), both seemingly invoking the dimensions of sameness–difference and genuineness–artifice. Later Tom uses a tactic of illegitimation by disparaging the man's job-related expertise by explaining to Chris and Jim his poor knowledge of rats' anatomy: cos he come from Cardiff and he's thick (2, line 47).

What we have affirmed here, then, is the dynamic nature of coming to understand who “we” are and who “they” are against the non-normative “others.” So there is the comparison between what “we” do – you go out you have a laugh and you can pull – and what “they” do, five consecutive weeks running? In the general frame of things, others may be either members of the in-group who stray from the accepted norms of behavior, or out-group members who are seen to “encroach” on “our” territory and compete for resources – physically (e.g., asylum seekers, refugees, immigrants) or metaphorically (political or religious opponents, or social, class, or cultural foreigners of the not a nice area or Cardiff bloke type; see also Neuman et al. 2002, quoted above). Othering both in-group and out-group members is fueled by fear of sanctions or changes in circumstance which may be brought about by unsettling the existing balance of power and social relations, the status quo, which may, of course, be different for everyone. We have seen how norms of appropriate behavior within a particular group may involve expressing (dis)approval of transgression (going out and “pulling”; destroying stolen property). Such behavior marks young people out from other groups like their parents. And othering sends out signals to out-group and in-group members alike: “Keep out” and “Stay put,” respectively. If there is no threat of social players moving from one camp to another, there is no need for othering anyone. “Exotic,” distant, unfamiliar people can remain unothered in their difference, different rather than othered as long as they stick to their social and physical spaces. Familiar, close, domesticated people need to know their place, too. Crossing over toward another camp brings about the punishment of othering from both sides.

Of course, it is unrealistic to assume that people will not cross social, political, national, religious, age, gender, and various other boundaries, although sometimes these changes will be more permanent than at other times (cf. the potential transience of the cousin in ex. 1 sleeping with the men from the wrong area). It is also unrealistic to think of different people not coming into contact with one another because of enforced or voluntary flows of people, or simply getting goods and services locally (cf. the students coming into contact with the rat-catcher and the firemen in ex. 2). In each case a boundary is crossed, however briefly, which serves to redraw the lines between one's own group and others.

An analogy to be drawn here is that of people's identities in liminal periods in social life (Turner 1969, 1974). These moments occupy marginal, transitory social spaces where the identities, relationships, and norms of everyday behavior are loosened. To invoke and cope with the momentary unpredictability of social identities and relations in marginal forms of conversation – ritual and de facto insults, for example – participants resort to a range of possible forms of communicative behavior: humor and verbal play (Sherzer 2002), ritual (Eggins & Slade 1997) and scripted talk (Clark & Van Der Wege 2001), language crossing (Rampton 1995), stylization (Coupland 2001, 2004), silence (Basso 1972, Jaworski 1993), and so on.

Various forms of verbal stylization present in our examples (most notably performance of Cardiff dialect, a North Walian accent, and RP in ex. 2) are instances of “crossing,” which, as Rampton 1995 argues, positively enhances liminal moments or periods when normal social relations are loosened or subverted. As we demonstrated above, gossipy events – in themselves little rituals of everyday life, falling into the category of liminal genres (or “liminoid,” Turner's preferred term for acts of play and leisure in modern urban settings) – create liminal identities for the people who are their objects. Appropriating the voice (language) of a different group in the act of crossing, or more generally verbal stylization (see Coupland 2001, 2004), places both the speaker and also the original or legitimate user of the performed voice in a liminal, ambiguous position, as the person speaking is projecting a self which is neither his/her own or that of the targeted individual (or group). Like actors on stage operating at the interface of real and unreal, or, put differently, in the theatrical frame of make-believe (Goffman 1974), crossing individuals momentarily suspend their actual role and assume an illusory one. In effect, they remain themselves and become somebody else at the same time. And while someone else's persona is being invoked, the other being discussed cannot be fully recognized as unambiguously “there.”

The other discursive strategies of othering discussed above lend themselves to a similar interpretation of invoking liminal identities of the objects of gossip: Stereotyping (homogenizing) denies a person's “true” status as an individual; pejoration ultimately relegates people to the tabooed status of “waste”; silencing deprives people of their voice, which is both a symbol of their individuality and humanity. Certainly, othering is a highly face-threatening act to both the gossipees and the tellers and their “accomplices,” which is probably why subverting tolerance and displaying “liberalism” (Coupland 1999) are also necessary othering strategies which work toward managing the face of those doing othering – giving reasons, claiming high moral ground, and so on.

There is another aspect of gossip as a liminal type of activity on which we need to comment. Just as we have argued that gossip creates liminal identities for the gossipees, it is also true for the gossipers. In our overview of gossip above, we mentioned Haviland's (1977) remark that gossip is both anxiety-provoking and exciting in that it produces a sense of fellow spirit among the sanctioned participants through transgression and collusion. In this very act, however fleeting, the gossipers are not merely in-groupers but accomplices in crime, momentary villains, as well as self-styled high priests of moral values, behavioral standards, even wisdom, knowledge, and erudition. As performers of these communicative rituals, they shed their everyday identities and interpersonal connections and enter a “higher” level of existence and bonding. To use Turner's (1969, 1974) term, which he borrows from Van Gennep's (1960 [1909]) work on rites of passage, sharing gossip creates a sense of communitas – a mode of social interrelatedness that suspends the usual social roles, their statuses, and their structural relations. Through/in the state of communitas, relationships are simplified, homogenized, underdifferentiated, egalitarian, direct, and nonrational (although, as Turner argues, not irrational). Yet social structure is not totally absent from communitas. Both modalities stand in a dialectic relationship to each other; for each level and domain of structure there exists a mode of communitas. Turner explains:

It is as if social relations have been emptied of their legal-political structural character, which character, though not, of course, its specific structure, has been imparted to the relations between symbols, ideas, and values rather than between social personae and statuses. In this no-place and no-time that resists classification, the major classifications and categories of the culture emerge within the integuments of myth, symbol, and ritual. (Turner 1974: 259)

Liminal moments can be seen, then, as on the one hand inverting the everyday relations of power and structure, while on the other hand reaffirming them. Once the gossipy event is over, the “normal” in-group relations among the gossipers may be resumed, albeit with the reinforcement of shared transgressive, collusive, complicitous behavior.

Although this may seem a long way from discussing untidy bedrooms in gossip events, Turner (1974:257) mentions other types of transgressive behavior appearing in myths, symbols, and rituals that are characteristic of liminal situations: social and cultural taboos of incest, cannibalism, murder of close kin, and mating with animals. It is the prerogative of gods in many mythologies to kill or injure their fathers, sleep with their mothers or sisters, or have sex with animals symbolizing mortals. In various initiation rites to adulthood or secret societies, acts of symbolic or actual cannibalism are not uncommon. All these mythic and ritual acts play on and affirm the social rules of exogamy, prohibition of incest, respect for the elders, and differentiation between humans and animals. Thus, liminal moments allow an inversion of reality, with the portrayal of the antistructural relations partly for pedagogical reasons, and partly to allow the participants in liminal moments to absorb and impart sacred knowledge that will allow them to wield great power of social control.

Gossip works in a fashion similar to myths. As has been suggested, sharing gossip is a little ritual, a liminal state in which the participants bond in a state of communitas, casting a gossipee as an “other.” On the one hand, this has a didactic, regulatory function reinforcing the axiomatic moral code of everyday social structure. On the other hand, gossip makers step into a temporally liminal space of transgressive and dangerous talk, in which they spontaneously invoke, share, and absorb “sacred” knowledge and exert symbolic power over others (the gossipee). In this act, the gossipee may be deprived of status and authority but also accorded a sacred power, knowledge, or qualities. In other words, the gossipee may be everything that the others are not but may desire to be. Freed of inhibitions, liberated of social constraints, or occupying an otherwise privileged position, the gossipee is simultaneously despised and revered, with his or her persona being enacted in a transient moment of identity construction or appropriation, which the tellers typically signal as performances through the use of special codes or expressions (e.g., swearing), quoting (reported speech), high pitch, whispering, loud laughter, and so on (cf. Bauman 2001 [1975]).

We have demonstrated how gossip creates marginal identities for individuals branded as norm-breakers, which can be either demeaning or praiseworthy. It is probably more commonplace, particularly in more central instances of gossip (as in our ex. 1), that gossip results in negative marginalization of gossipees. However, we have also presented evidence of positive (self-)othering, especially in the story my desk … I nicked it from the bar. It is in such episodes that participants (like the two male students in ex. 3) find affirmation of their bonding in pushing against the norms of the dominant group. So certain types of transgression may be sanctioned by the in-group (stealing a bar table, and later destroying it, being a relatively mild offense as opposed to stabbing the bartender, for example). As such, telling stories of mild transgression such as this one, by pushing at the boundaries of acceptability, allows the group to manifest resistance to the limiting, oppressive, and subjecting norms imposed on them from outside, thus embracing the very idea of liminality.