Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 June 2005

Following the return of sovereignty from Britain to China, Hong Kong has undergone significant sociopolitical and educational changes. This study is a quantitative investigation of the language attitudes of 1,048 secondary students from the first postcolonial generation brought up amid the significant changes after the political handover. The results show that the respondents feel the most integratively inclined to Cantonese (the vernacular variety), and they perceive English (the colonizers' language) as the language of the highest instrumental value and social status, while Putonghua (the language of the new ruler) is rated the lowest from both the integrative and the instrumental perspectives. Unlike what has been predicted by scholars, Putonghua has not yet taken the place of English as the language of power. Despite this, there are signs of a subtle transition toward an accommodating attitude to Putonghua, mainly induced by the growing instrumental value of the language for economic purposes.

Discussion of language attitudes has a long history, but this seemingly old topic has never failed to catch the attention of scholars and educators over the past decades. In fact, language attitudes interact dynamically with the changes of time and sociopolitical environment. It is this fluid nature of the topic that keeps fresh in different times and contexts. With Hong Kong entering the period of “decolonisation without independence” (Pierson 1994a) or of being “China's new colony” as described in Vines 1998, issues around language attitudes take on new significance. Li 2000 argues that Hong Kong people are not passive victims of linguistic imperialism (cf. Phillipson 1992) but active agents of pragmatism in their choice of languages. In the new sociopolitical context after the change of sovereignty in 1997, attitudes of Hong Kong people toward different language varieties may have undergone interesting developments while these active pragmatists are repositioning themselves in the new scenario of power, making the language choices wisest for their interests.

Hong Kong is a city in southern China; more than 90% of its population is ethnic Chinese. Since 1997, Hong Kong has undergone great changes in various senses. Upon the political handover, Hong Kong was no longer a British colony but a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the PRC (People's Republic of China). No matter how resistant one might feel about the change of sovereignty, it is now an indisputable fact that Hong Kong is politically part of China (Lau 1997). Before 1997, English (the colonizers' language) and Cantonese (the vernacular language) formed a diglossic situation (Fishman 1967) in which both languages were used in different domains and for different functions. English was a prestige language for the formal institutions of government, law, education, and business, while Cantonese was used by the vast majority of the Hong Kong population as their usual variety in family and other informal daily-life settings (Pierson 1994a). However, with the political handover, it was commonly believed that Putonghua (the national language of the PRC, also known as Mandarin) would replace English as the language of politics (Pierson 1994a). This prediction started to materialize after the handover when the chief executive of the first Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) government declared the policy of “Biliteracy and Trilingualism” in his first policy address in October 1997, through which Putonghua was formally introduced into the sociolinguistic setting of Hong Kong. Hence, Hongkongers of the postcolonial generation will have to be able to write Chinese and English and speak not only Cantonese and English, but also Putonghua.

Apart from the political change, Hong Kong experienced the most serious economic downturn in its history shortly after the change of sovereignty in 1997. Following the economic slump were bankruptcies, closing down of companies, and cutting of expenditures in all sectors. Unemployment rates soared from 2.1% in 1997 before the change of sovereignty to 7.7% in 2002 (Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department 7/2002). Being unable to find desirable jobs in the shrinking local labor market, more and more people sought employment in the PRC. As a result, Putonghua became important linguistic capital for Hong Kong people as an increasing number of jobs required competence in the language (Adamson & Auyeung-Lai 1997).

Two months after the handover in July 1997, significant changes also took place in education. As a gesture of decolonization, the new HKSAR government announced the mandatory Mother Tongue Education Policy for foundational education from Primary 1 to Secondary 3.1

%1 Formal schooling in Hong Kong comprises 6 primary years, 5 secondary years, and 2 preparatory years for university entrance. “Foundation” education, which is universal and compulsory, refers to the 6 years of primary and the first 3 years of secondary school.

Apart from the enforcement of mother-tongue education, the importance of Putonghua was also significantly enhanced in schools. Before 1997, the language was taught in most schools only in the course of extracurricular activities. Since 1998, Putonghua has become a core subject in the school curriculum from Primary 1 to Secondary 3. In 2000, it also became an elective subject for the Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examination (GCSE equivalent).

The new postcolonial context described above may have significant impacts on the language attitudes of different groups of people in Hong Kong. Among them, the most notable group is those who started secondary-school education in 1998, when Hong Kong had been returned to the sovereignty of the PRC for one year, the effects of the economic slump had become widespread and distinct, and the new policy of “Biliteracy and Trilingualism” and the mother-tongue education policy had just been introduced. This group of students was at the beginning of Secondary 4 studies at the time of my research in October 2001, and they were the first generation of Hong Kong secondary school students brought up amid all the changes after the handover. This study aims to find out the attitudes of this particular group of students toward Cantonese, Putonghua, and English in the new sociopolitical context of Hong Kong. Responses thus elicited will reflect significantly on how this group of active pragmatists (Li 2000) interprets the postcolonial scenario and reacts according to their best interests. Given the postcolonial situation in Hong Kong, which favors the development of Putonghua, it is expected that the respondents of this study will show a significantly positive attitude toward that language. Although this study starts from a micro perspective that investigates how the first postcolonial generation in Hong Kong secondary schools perceives different language varieties in specific social contexts, it is hoped that information thus collected will ultimately throw light on macro issues such as language shift and development of multilingualism in a society.

In many discussions in social psychology, the concept of “attitude” is defined as a tendency to react favorably or unfavorably to a class of objects (e.g. Edwards 1994, Foddy 1993). Attitude is a latent process that is internal to a person and therefore cannot be directly measured but can be inferred through observable responses elicited by stimuli (Eagly & Chaiken 1993). When summing up social scientists' attempts to measure attitudes, Gardner 1985 points out that attitude is usually measured through individuals' reactions to evaluatively worded belief statements. From an operational point of view, Gardner describes attitude as “an evaluative reaction to some referent or attitude object, inferred on the basis of the individual's beliefs or opinions about the referent” (1985:9). In fact, such a method has been used widely in studies of language attitudes for decades in Hong Kong. Although other methods – such as the matched guise test and content analysis – were also used (e.g. Lyczak et al. 1976, Pierson 1994b), most of the studies of language attitudes were conducted in the form of questionnaire surveys, through which individuals' reactions to a number of evaluatively worded statements were graded on the Likert scale.

Of the many previous studies conducted in Hong Kong, Pierson et al. 1980 has been influential and has attracted subsequent replications. To elicit the respondents' attitudes about English, Pierson and colleagues surveyed 466 Hong Kong secondary students' attitudes to English and Chinese by direct and indirect methods. The direct method was to ask students to rate 23 statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “absolutely agree” to “absolutely disagree.” The indirect measure was to ask the students to rate the degree to which a number of stereotypes fit themselves, their ideal selves, native speakers of Cantonese in Hong Kong, and native speakers of English in Hong Kong. The results suggest that the subjects clearly realized the pragmatic functions of English in Hong Kong while they demonstrated strong in-group loyalty to Chinese cultural identity. Many of the subjects claimed that they felt unpatriotic when using English. As for the indirect measure, it was found that Chinese speakers were usually rated high for traits related to in-group qualities like friendliness, trustworthiness, sincerity, and gentleness, while English speakers were rated high for attractiveness, affability, and clear thinking.

Pennington & Yue 1993 replicated the study of Pierson et al. 1980 for attitudes toward English and Chinese and compared their findings with those of the original study. The replication was done only on the direct measure; the indirect measure was abandoned because it was considered too abstract for secondary students. A 4-point Likert scale was used instead of a 5-point scale to avoid a central tendency. In Pennington & Yue 1993, 285 Hong Kong students from F.1 to F.6 (aged 11–18 years) attending eight different schools were asked to answer a questionnaire containing the same items as the original study. Similar to the findings of Pierson et al. 1980, Pennington & Yue 1993 found that the subjects were positive about English. Most of them expressed a wish to speak fluent and accurate English. English was seen as a symbol of high status, and they agreed that a command of English was very helpful in understanding foreigners and their culture. However, as regards ethnolinguistic identity, there was a clear difference between the two studies. While Pierson's subjects agreed that using English would make them feel less Chinese and not patriotic, those of Pennington & Yue did not agree that using English would have negative effects on their identity. Pennington & Yue therefore concluded that the old antagonism of Chinese vs. English observed in the early 1980s had become outdated.

Axler and his associates replicated the same study in 1994. Similar to the findings of Pennington & Yue 1993, Hong Kong young people were found to perceive themselves as a pragmatic bilingual group who would not feel “un-Chinese” when using English. English no longer carried the connotation of a colonizer, but was seen as an international language for wider communication (Axler et al. 1998).

Hyland 1997 reported on a similar questionnaire study with 900 university students shortly before the political handover in 1997. The analysis was conducted in terms of five factors on a 4-point Likert scale. Although English, Cantonese, and Putonghua were mentioned in the questionnaire, all of the five factors were devised with English as the focus. The findings showed that although English was recognized for its instrumental value, it was not significant in familial contexts or as a status marker.

In an attempt to put a balanced focus on all three language varieties advocated in Hong Kong after the political handover (Cantonese, English, and Putonghua), I conducted a questionnaire survey after the change of sovereignty in 1999 with 134 senior secondary students, also on a 4-point Likert scale. The main purpose of the study was to compare the attitudes of middle-class elites and working-class low achievers toward Cantonese, English, and Putonghua. The results showed that there were few significant differences in perception between the two groups. Both groups expressed positive attitudes toward the three spoken varieties, with English being the language with the highest instrumental value, Cantonese the language for in-group identity, and Putonghua the language for nationwide communication. Although many Hong Kong people expected a higher status for Putonghua in Hong Kong after 1997, it was rated last after English and Cantonese in terms of status and importance (Lai 2001).

Adopting the methods of the previous research, this study continues the exploration of language attitudes through a questionnaire survey on a larger scale (1,048 respondents). In view of the need for triangulation, other research instruments – a matched guise test and focus group interviews – were also used to substantiate the findings gathered from the questionnaire survey (Lai 2002). However, owing to the limitation of length, this article reports only on the construction and findings of the questionnaire survey, although references will be made to the other two parts of the study when necessary.

Much like the previous studies reviewed above, this questionnaire survey aims at collecting individuals' reactions to a list of evaluatively worded statements (Gardner 1985). In order to give a clear focus to the research, this survey was devised especially to explore the students' attitudes in terms of their integrative and instrumental orientation toward the three spoken varieties.

According to Gardner & Lambert 1972, “instrumental orientation” refers to a positive inclination toward a language for pragmatic reasons, such as obtaining a job or higher education opportunity; and “integrative orientation” refers to a favorable inclination toward a language in order to become a valued member of a given community. “Integrativeness” thus implies not only an interest in a language, but also an open attitude toward another cultural group; in the extreme, it suggests emotional identification with the community of the target language (Gardner 2001). Although such a sociocultural model is often criticized as being too simplistic to explain L2 learning motivation (Dornyei 2001), it offers a macro perspective that allows researchers to characterize the perceptions of a community as a whole.

When Gardner & Lambert first proposed the notion of integrative and instrumental orientation, the main focus of discussion was about motivation to second language learning. However, when the theory is applied to the research on language attitudes in this study, the attitude's object is no longer the learning of an L2, but the target language itself and its community. Through an exploration of the integrative orientation of the first postcolonial secondary-school generation, this study therefore aims at finding out how much the respondents favor a language because of their emotional identification with the language and the language group. Similarly, their instrumental orientation will reveal how much they favor a language because of its instrumental value and social status.

Based on the above understanding of integrative and instrumental orientation, specific research questions were devised for this survey: (i) How strongly are the respondents integratively oriented toward Cantonese, English, and Putonghua? (ii) How strongly are the respondents instrumentally oriented toward Cantonese, English, and Putonghua? And (iii) how do the three spoken varieties rank in terms of the respondents' integrative and instrumental orientations?

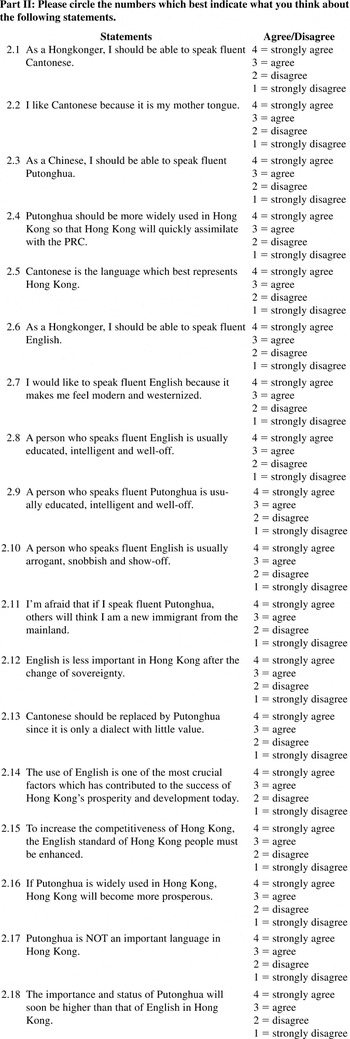

A bilingual questionnaire in Chinese and English was devised to collect students' responses toward Cantonese, English, and Putonghua. In search of answers to the research questions, statements were devised along six prescribed parameters: (i) integrative orientation toward Cantonese, (ii) integrative orientation toward English, (iii) integrative orientation toward Putonghua, (iv) instrumental orientation toward Cantonese, (v) instrumental orientation toward English, and (vi) instrumental orientation toward Putonghua.

Following Pennington & Yue 1993, Hyland 1997, and Lai 2001, a 4-point Likert scale was used to avoid a central tendency. The questionnaire was divided into the following parts: Part I, personal information; Part II, 18 statements devised on a 4-point Likert scale (4 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree, etc.); Part III, 6 statements devised on a 4-point Likert scale, requiring respondents to evaluate the three target languages on the same statements (see the questionnaire in the Appendix). Statements of Parts II and III were devised along the same parameters, but separated into different sections for reasons of format. Since the two parts consisted of statements on the same 4-point scale, they were combined for statistical analysis.

A total of 49 in-service secondary English language teachers participating in the same professional training course were invited to administer the questionnaire to one of the Secondary 4 classes (about 40 students) in each of their schools through convenience sampling. If the teachers did not meet any Secondary 4 classes, they were requested to borrow lesson time from colleagues. In the end, because of rejection by teachers and principals, only 28 teachers agreed to administer the survey. In order to reduce discrepancies among different questionnaire administrators, standard instructions were recorded on audio-cassette tapes in Cantonese (the students' mother tongue) by the researcher, which were then played to the subjects while they were answering the questionnaire. The questionnaire was piloted two times, first with a group of undergraduates in the researcher's university, and second with the participating teachers. Following their suggestions, changes were made mainly in the wording of the questions and the layout of the options. All parties involved (principals, teachers and students) were informed clearly about the purpose of the survey and told that participation was voluntary.

A total of 1,120 completed questionnaires from 28 different schools was returned. To ensure measurement validity, initial data cleaning was carried out by the researcher. As a result, 72 problem questionnaires were excluded because the credibility of the responses was dubious (e.g., the same answer to all questions). In the end, a total of 1,048 questionnaires was used for statistical analysis.

To facilitate a focused discussion, factor analysis was used to reduce data into different matrices so that comparisons between factors could be carried out more efficiently. However, in view of warnings in the literature that exploratory factor analysis does not always produce matrices that are meaningful (e.g. Gorsuch 1983, Comrey & Lee 1992), confirmatory factor analysis was used instead to test the construct validity of the six prescribed factors (i.e., three factors on integrative orientation and three factors on instrumental orientation). The goodness-of-fit test was then used to show how well the six fixed factors specified the model of language attitudes in this study (Stapleton 1997).2

According to Stapleton 1997, “Confirmatory factor analysis is a theory-testing model … the researcher begins with a hypothesis or model prior to the analysis. This model, then, specifies which variables will be correlated with which factors and which factors are correlated. Confirmatory factor analysis offers the researcher a more viable method for evaluating construct validity. The researcher is able to explicitly test hypotheses concerning the factor structure of the data due to having the predetermined model specifying the number and composition of the factors.” In the case of this study, data were put into six parameters by the researcher according to Gardner & Lambert's (1972) motivation theory, and confirmatory factor analysis helps to show whether such a construct is accepted or rejected.

The optimal values for GFI (goodness-of-fit index) and NFI (normed fit index) are 0.9–1 (Comrey & Lee 1992, Mok 2000b).

Means and standard deviations (SD) were also calculated on each item in the questionnaire. Any mean values greater than 2.54

In response to comments by an anonymous referee, clarification about the midpoint of a 4-point scale is provided as follows: Since respondents were not given the option “0”, the midpoint is 2.5 for a 4-point Likert scale, having options 1 and 2 on the negative side (i.e., strongly disagree and disagree) and options 3 and 4 on the positive side (agree and strongly agree). 2.5 therefore indicates a neutral tendency which does not skew to either side of the scale. For a 5-point scale with 1 being the lowest option, the midpoint is 3.

As mentioned before, a total of 1,048 questionnaires collected from 28 mainstream secondary schools in Hong Kong was used for statistical analysis. The respondents were all at the beginning of their Secondary 4 studies (ages 15–17) at the time of research. All of them are ethnic Chinese. The large majority (N = 833) were born in Hong Kong; 167 were born in mainland China; 11 were born in other places; and 37 respondents did not provide information on this aspect. Regarding language use, apart from 42 missing cases, the vast majority of the respondents (N = 958) used Cantonese as their home language; 31 spoke other Chinese dialects at home; 13 spoke Putonghua; and four used English as their home language. As regards cultural identity, among those who responded, 611 claimed a local identity as Hongkongers; only 134 identified themselves as Chinese, and 201 claimed a double identity as Hongkong-Chinese.

In this section, the statistical results will be described in search of answers to the research questions set out for this study. The findings for each question will be presented in order.

As revealed in the high composite mean value for Factor 1 in Table 1, secondary students of the first postcolonial generation seem to show a highly positive inclination toward Cantonese (the vernacular language) from the integrative perspective. Despite the disparity in views as shown by the standard deviation values, the respondents seem to agree quite strongly that they like Cantonese because it is their mother tongue and a characteristic of Hong Kong. As Hongkongers, the respondents agree that they should be able to speak fluent Cantonese. They also tend to disagree quite strongly with the statement “Cantonese should be abandoned since it is only a dialect with little value.” In addition, they claim rather strong affection for vernacular Cantonese and its speakers.

Factor 1: Integrative orientation toward Cantonese (α = 0.67).In response to comments by an anonymous referee, clarification about a reversed mean is provided as follows: If the mean for a statement is 1.88, it means that it is 0.88 away from the lowest end of the scale (i.e. 1); when reversed, it should be 0.88 from the highest end of the scale (i.e. 4). Since 4 − 0.88 equals 3.12, the reversed mean of 1.88 is therefore 3.12.

As shown in Table 2, means are clearly greater than 2.5 for all positively worded statements and less than 2.5 for the negatively worded one. This reveals a generally positive attitude of the respondents toward English. Although the SD values have warned about the disparity in the respondents' attitudes, on the whole students tend to agree rather strongly that they like English and its speakers, and the language is a symbol of modernity and westernization. Students also tend to agree, though less strongly, that English suggests positive attributes like education, intelligence, and wealth. Little negative sentiment is detected toward English because respondents inclined to disagree with a statement that people who speak fluent English are usually snobbish and arrogant.

Factor 2: Integrative orientation toward English (α = 0.62).

As shown by the composite mean in Table 3, the integrative orientation of the respondents toward Putonghua is near the central point (i.e. X = 2.47). In fact, means of all statements within this factor largely reveal a negative tendency toward the language. In addition, respondents inclined to disagree that they have the obligation to speak fluent Putonghua because they are Chinese. They also tend to disagree that Putonghua should be used as a means to quicken assimilation between the PRC and Hong Kong. Nevertheless, respondents seem to be quite positive about Putonghua speakers, and they tend to disagree that speaking Putonghua would make them seem like mainlanders. Although little resistance to Putonghua speakers is detected, the respondents do not seem to show much integrative enthusiasm for the Putonghua group because it does not suggest education, intelligence, or wealth (see Statement 2.9). However, while the mean values are used as important indicators of the respondents' attitudinal inclinations, one must be cautious about the diversity in views shown by the relatively large SD values; it is unrealistic to expect unanimous attitudes among a sample of 1,048 students.

Factor 3: Integrative orientation toward Putonghua (α = 0.75).

After the study of integrative orientation, students' attitudes toward Cantonese, English, and Putonghua were examined from the instrumental perspective. As revealed from the statistical results in Table 4 below, the respondents tend to agree rather strongly that Cantonese is a highly regarded language in Hong Kong. It is helpful for both their future studies and their career development, and they tend to wish quite strongly to master the variety with high proficiency.

Factor 4: Instrumental orientation toward Cantonese (α = 0.69).

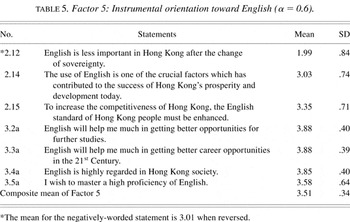

The high mean values revealed in this factor seem to show students' high evaluation of English for its instrumental value and status. As shown in the statistical results below, the respondents tend to agree strongly that English is a highly regarded language in Hong Kong society, and it is a very helpful language that enables them to obtain better opportunities for further studies and career development. As revealed by the small SD value of this factor (s = 0.34), students' perceptions in this regard seem to be virtually unanimous.

Factor 5: Instrumental orientation toward English (α = 0.6).

Though less strongly, students also show a clear tendency in agreeing that English is a key to social prosperity. If Hong Kong has to increase its competitiveness, the English proficiency of Hong Kong people must be enhanced. Although many scholars predicted that the status of English would decline after the change of sovereignty, respondents of this study tend to disagree. Instead, students express strong wishes to master English with high proficiency.

Although the composite mean of Factor 6 is not high (X = 2.66), it reveals students' positive perception of Putonghua in the instrumental aspect. However, clear indicators seem to be missing in many of the statements because the mean values are mostly marginal, being very close to the central point. This is perhaps understandable because Putonghua is new to the sociolinguistic scene of Hong Kong, and its role as a second language is not yet consolidated. As shown in Table 6, students tend to agree quite strongly that Putonghua can help them a great deal in getting better career opportunities in the 21st century. Such a response is perhaps unsurprising, since it is commonly believed that more job opportunities will be available in the PRC subsequent to its joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. What is more, being able to seek employment in the PRC became increasingly important for Hong Kong people as a result of the economic downturn and the shrinking manpower demand in Hong Kong after 1997. Though marginally, students also tend to agree that Putonghua is a highly regarded language in Hong Kong that will help them obtain better opportunities for further studies, and they wish to master it with high proficiency.

Factor 6: Instrumental orientation toward Putonghua (α = 0.83).

Although students tend to agree that Putonghua is an important language, its status does not seem equal to that of English. In fact, the correlation between Putonghua and social prosperity turns out to be far weaker than that of English: The mean value of Statement 2.16 (“If Putonghua is used widely in Hong Kong, Hong Kong will become more prosperous”) is only marginal (X = 2.51), whereas that of a comparable statement for English (2.14: “The use of English is one of the most crucial factors which has contributed to the success of Hong Kong's prosperity and development today”) is 3.03. Apart from this, the comparatively larger SD values found in all Putonghua-related factors reveal greater disagreement among the respondents in their attitude toward Putonghua as compared to those toward Cantonese and English. This again reflects the immature development of Putonghua in the sociolinguistic scene of Hong Kong. Perceptions among respondents are more divided when roles and functions of the language are not yet consolidated.

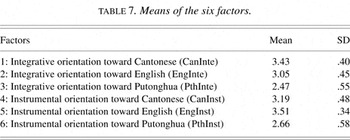

As shown in the composite mean values in Table 7, secondary students of the first postcolonial generation tend to show the most positive integrative inclination toward vernacular Cantonese (X = 3.43), and the second strongest integrative inclination toward English (X = 3.05) while that for Putonghua tends to be neutral (X = 2.47), indicating that the respondents have the weakest integrative inclination toward the national language of China. Such a difference between the integrative orientations toward the three target varieties is proved statistically highly significant through one-way ANOVA with p < 0.0005.6

To compare three means, one-way ANOVA was used. The significance value displayed in the SPSS output is .000; it in fact means p < 0.0005. Since this value is much smaller than that at the usual significance level (0.05), it shows that the difference between the three varieties is highly significant.

Means of the six factors.

In the instrumental domain, the respondents' inclinations toward all of the three language varieties tend to be positive. English is perceived as the language of the highest instrumental value and status (X = 3.51), and Cantonese the second (X = 3.19), while Putonghua the last among the three language varieties (X = 2.66). Similar to integrative orientation, one-way ANOVA was applied to compare the respondents' perceptions of the three target varieties in the instrumental domain. The result proves that the difference is statistically highly significant with p < 0.0005. As regards SD, the lowest value (s = 0.34) is found with English, showing the smallest disparity in the perceptions of the respondents; Cantonese has the second lowest SD (s = 0.48), while that of Putonghua is the highest (s = 0.58), indicating the highest level of disagreement among the respondents.

After comparisons across Cantonese, English, and Putonghua, attempts were made to compare students' integrative and instrumental orientation to the same language variety. A paired-samples t-test was therefore applied, and the results showed that the difference between the respondents' integrative and instrumental orientation toward Cantonese is statistically highly significant with p < 0.0005, and so are the differences between the two types of orientation for English and Putonghua. As regards Cantonese, students' integrative orientation is found to be much stronger than their instrumental orientation, showing that the respondents favor the mother tongue and its community mainly for affective reasons. In contrast, English and Putonghua are valued more for the instrumental values that they can bring. This seems logical, since English and Putonghua are nonnative languages that students seldom use for daily-life communication, and they learn them only as compulsory subjects in school.

In brief, the first postcolonial generation in Hong Kong secondary schools examined in this study is largely positive in integrative orientation toward Cantonese and English, whereas that toward Putonghua is near the central point. From the instrumental perspective, the respondents' orientation toward all three spoken varieties is also positive. Despite the fact that the postcolonial context does favor the development of Putonghua, students rate the language positively only for its instrumental value while they remain emotionally rather detached from its group.

Although the respondents' attitudes toward the three spoken varieties generally fall within the positive range, the intensity of such a positive orientation is substantially different for each variety. As far as their integrative orientation is concerned, the findings show that the respondents like Cantonese most, English second, and Putonghua least. They like Cantonese most because it is their mother tongue and the language that best represents Hong Kong. Although their integrative orientation toward English is also positive, as revealed from the statistical analysis of the questionnaires, it is significantly less strong than that for Cantonese, though a lot stronger than that for Putonghua. Although it seems entirely understandable why students like Cantonese and its speakers most, it is rather surprising to find students expressing stronger integrative orientation toward English (the colonizers' language) than toward Putonghua (the national language of their motherland). As revealed in this survey, the most likely reason is that English is always equated with high education, intelligence, and westernization whereas Putonghua is not. The English community is therefore the group with which the respondents would desire more to identify.

Similarly, although the respondents' instrumental orientation toward the three spoken varieties is generally positive, the intensity of their positiveness varies significantly. Among the three varieties, the students show the strongest instrumental orientation toward English because it maintains its role as a gatekeeper for upward and outward social mobility. Even in the postcolonial context of Hong Kong, the hegemonic position of English as the language of power seems to remain unshaken. Cantonese ranks second in this regard mainly because it is the language used most widely within the Hong Kong territory. Despite the economic boom in the PRC and the enhanced status of Putonghua in Hong Kong after the change of sovereignty, that language still ranks last because it is not considered as important as English for future studies and career. While a strong instrumental orientation toward English is unsurprising, the fact that Putonghua ranks lower than Cantonese in this aspect is quite unexpected, since it is commonly claimed that Putonghua has gained much greater importance in Hong Kong society after the change of sovereignty (e.g. Bauer 2000, Boyle 2000).

When students' integrative and instrumental orientation toward the same language are compared, it shows that students of this study favor Cantonese, their mother tongue, much more on affective grounds, while they value English and Putonghua (the nonnative languages) mainly for instrumental reasons.

In fact, validity of the above findings is supported through the matched guise test (MGT), which was used in the same study for the purpose of triangulation. In brief, apart from answering the questionnaire, subjects of this study were also asked to listen to three voices reading the same passage in different varieties, Cantonese, English, and Putonghua, and to judge them on 13 personality traits. The fact that the speaker for all guises was the same person was not revealed to the respondents. Since individual paralinguistic variables, such as tone, pitch, and rhythm, were eliminated, the responses thus elicited were considered true reactions toward the language variety itself, rather than toward the speakers (Edwards 1994). Similar to the questionnaire survey, the MGT results showed that Cantonese was rated the highest on traits of solidarity (e.g. friendly, trustworthy, kind), implying integrative orientation toward the mother tongue; and English the highest on traits of power (wealthy, modern, highly educated, etc.), indicating the strongest instrumental orientation toward the language. Similarly, Putonghua was rated the lowest in both categories in the MGT (Lai 2002). Since the findings of both studies are much in line with each other, validity of the findings gathered through the questionnaire survey is further supported.

This study set out to examine students' language attitudes in the postcolonial context of Hong Kong. However, as pointed out by Loomba 1998, “postcolonial” is a problematic term. If “colonialism” is defined as political sovereignty, Hong Kong has undoubtedly entered its postcolonial era after its return to the PRC. Yet if “colonialism” is understood as the domination of Western ideologies and penetration of economic systems, then Hong Kong may still be in its colonial state. With reference to Mazrui's (2002) description of the language scenario in African countries, Hong Kong largely resembles some former British colonies in Africa (e.g. South Africa, Kenya) in that English remains the most highly valued language even after the period of colonization. In these countries, English was often a gatekeeper language in colonial days, and only those who spoke and behaved in the image of the colonizer would be rewarded with better education and social opportunities (Memmi 1998 [1968]). As a country enters the postcolonial era, the same ideology will usually persist and the old colonizers' language continue to be valued as a higher variety.

Like many former British colonies in Africa, the HKSAR government has attempted to replace English-medium instruction with compulsory vernacular education in Cantonese to bring about decolonization immediately after the change of sovereignty, and yet this effort was met with great resistance from parents because the role of English in gatekeeping remains unchanged (Lai 1999, Tsui et al. 1999). For people of Hong Kong, English is still a prestigious language for upward and outward mobility and therefore is indispensable even after the change of sovereignty.

The hegemonic position of English is, however, not merely an effect of colonization in the political sense, which, in some cases, has been proved to be unessential in sustaining the influence of a language. In the similar case of Vietnam, the colonial period under France did not leave “a reserve of French language skills in the country” (Wright 2002:231). Similarly, people in Macau, a former Portuguese colony in South China, were never too keen to learn Portuguese even during the colonial period because it was not considered a useful language (Adamson & Li 1999). The fact that English is rated so highly for its instrumental values in this study is due largely to the coincidence that English is also the language that dominates the world. For this reason, many former British colonies, for example Malaysia, Singapore, India, and South Africa, find it hard to do without the colonial language even after independence, and Hong Kong is no exception as long as it wishes to remain a member of the global village.

As revealed in this study, an interesting development of Hong Kong students' attitudes toward English was detected through related studies in the past two decades. Pierson et al. 1980 found that English was considered a threat to Chinese identity and students felt unpatriotic when using English. Thirteen years later, in the replication by Pennington & Yue 1993, it was concluded that the old antagonism between English and Chinese had become outdated, and English was well received as a helpful means to understand foreigners and their culture. A similar result was found by Axler et al. 1998: English was no longer learned as the language of the colonizer, but as an international language for wider communication. Up until the present study, the importance of English has developed further from that of an international language into a marker of Hong Kong identity. This is supported by the respondents' positive response to the statement “As a Hongkonger, I should be able to speak English” (mean = 2.9). In fact, such an association between English and Hong Kong identity was reiterated in the focus group interviews, when many respondents claimed that English is part of their life and that they would feel surprised to find any Hongkongers without knowledge of the language, since it is used widely in Hong Kong and is taught in schools beginning in kindergarten (Lai 2003).

From an alien foreign language that threatened students' cultural identity to an element of Hong Kong identity, English has undergone an interesting development over the past decades in its relationship with the linguistic identity of Hong Kong students. The linkage between English and Hong Kong identity has not in any way become weakened after the change of sovereignty. Quite the contrary, its significance as a marker of Hong Kong identity has become even stronger in the postcolonial era.

As reported by Lau 1997, the large majority of the respondents who participated in the series of studies that he conducted from 1985 to 1995 held a stronger identity as “Hongkongers” than as “Chinese.” Although there was no strong indication in the findings to suggest a change in the trend, Lau found “a long-term though slow increase of the proportion of people claiming both identities as Hong Kong-Chinese” (1997:5). He expected this trend to become stronger after Hong Kong became part of China after 1997. Lau also suggested several factors that might help to strengthen identification with the Chinese nation among Hong Kong people: (i) the fact that Hong Kong is politically part of China; (ii) the growing military power and international status of China; (iii) increasing economic interdependency between Hong Kong and China; (iv) the modernization of China; (v) the propagation of nationalist values in Hong Kong; and (vi) the strengthening of social and cultural ties between the people in both places.

In fact, the conditions mentioned by Lau 1997 have started to materialize in the years after the change of sovereignty in Hong Kong. Following the active participation of the PRC in international affairs, China has gained higher political influence and prestige in the world (e.g. joining the World Trade Organization, hosting the 2008 Olympic Games). In addition, the social, cultural, and economic exchange between mainland China and Hong Kong has become extremely busy after the political handover. Passenger traffic in and out of Hong Kong grew by 11.7% from 1998 to 1999, and the growth was mainly attributable to the heavy cross-boundary traffic between Hong Kong and the PRC after reunification (HKSAR Government 1999). Thus, a stronger national identity with China should have developed among Hong Kong people, which in the end should help foster positive attitudes toward Putonghua. However, such a prediction is unsupported in this study because the large majority of respondents still identify themselves as Hongkongers (65%), 21% claim a double identity of Hongkong-Chinese, and only 14% call themselves Chinese. This perhaps explains the high integrative orientation of the respondents toward Cantonese, the vernacular marker of Hong Kong identity that people generally cling to in the postcolonial era as an icon of “two systems” under the PRC regime. As suggested by Pennington 1998, Cantonese is the most politically correct language variety, which symbolizes decolonization without arousing sentiments of recolonization. Upon entering the postcolonial era, Cantonese maintains its role as the lingua franca used for all intragroup communication. It is the most popular language variety among people and is highly valued for its function as a marker of Hong Kong identity. That function, however, has become even more prominent since the neocolonial days because people are eager to uphold a conspicuous marker that distinguishes them from mainlanders. Being representative of such common psychology of Hong Kong, Mrs. Anson Chan, the retired chief secretary for administration of the first HKSAR Government, restates the importance of maintaining the difference of Hong Kong from the PRC in an article in the Financial Times: “Hong Kong has thrived on its ability to blend the best tradition of East and West. Although it is necessary to smooth the flow of people, goods and capital between Hong Kong and the mainland, we must be careful not to blur the dividing line between two systems” (cited from SCMP, 1/7/02).

English also serves the function of a marker of Hong Kong identity. As mentioned in the previous section, such a relationship between English and Hong Kong identity was less prominent before the change of sovereignty, when English was considered a language of the colonizer and the out-group, and speaking it signified disloyalty to the country (Pierson et al. 1980). However, such an association between English and the British colonizers has become outdated. Owing to the rapid development of English as a world language, English is losing its national cultural base since it is no longer clear who the L2 speakers are (Dornyei & Csizer 2002). Hence, respondents in this study show a clearly positive integrative orientation toward English because the “English community” may simply mean fellow elite Hongkongers.

As regards Putonghua, although it is true that it has become more popular in the postcolonial context, it is rated positively only for its instrumental value. Since the respondents' sense of Chinese nationality is still far from strong, and Putonghua speakers as a group are considered not highly educated, intelligent, or well off (Statement 2.9), the first postcolonial generation in Hong Kong secondary schools expresses faint integrative orientation toward the language.

As reflected in the findings of this study, the vitality of Cantonese and English is still very high in postcolonial Hong Kong. Despite the fact that Putonghua has received much more social attention in the new political and economic scene, its vitality is not strong because its instrumental value is not as high as that of the other two languages, and people still feel emotionally detached from the Putonghua-speaking group. Without proper social engineering, it is not very likely that Hong Kong will reach a high level of trilingualism.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, Li 2000 argues that Hong Kong people are not passive victims of linguistic imperialism but active language pragmatists. Hence, the market value of a language seems to be the most important factor in determining its popularity and status. Hong Kong people's strong attachment to English is due not at all to their loyalty to the colonizer, but to their eagerness to gain assets for their future. Similarly, if Putonghua can prove itself a form of linguistic capital for its learners, then its status and popularity will be greatly enhanced. In fact, such a change is taking place in Hong Kong as more and more people are engaged in China trade, and the PRC is providing more business and job opportunities to Hong Kong people than anywhere else in the world. Li 2000 says that Hong Kong people's enthusiasm for English is a consequence of supply and demand; the same economic theory can be applied to Putonghua. If the demand for Putonghua grows high, the public will welcome plans and policies to increase the “supply” of the language. Such a force of market demand will be stronger than any kind of political imposition in changing language attitudes and thus inducing language shift in the end.

Hong Kong people may be active pragmatists in regard to English, yet as shown in the present study, respondents' attitude toward Putonghua is still rather reactive. Hence, students would need suitably stronger signals in their immediate environment to induce higher motivation to learn Putonghua. Possible ways may include adopting Putonghua as an official language in schools, extending the language into the senior secondary curriculum as a core subject and an elective subject for HKCEE (GCSE equivalent), and sending explicit messages to students about the importance of Putonghua as linguistic capital and the national language. In addition, celebrities and elites can be used as examples of good Putonghua speakers in order to strengthen the association of the language with the prestigious and highly educated group. Although the vitality of Putonghua in Hong Kong is relatively low at the moment, it is to be hoped that Hong Kong will move further toward being a trilingual society when Putonghua is better received for both integrative and instrumental reasons.

During the postcolonial era, Hong Kong's first generation in secondary schools has been found to be strongly integratively attached to Cantonese, the vernacular language, while they rely highly on English as a social ladder. Despite the political and economic changes after the handover, students do not show great enthusiasm for Putonghua. To maintain the role of Hong Kong as a bilingual city and to enable students to reach a high level of biliteracy and trilingualism, room has to be made for the development of all three language varieties in the society. For this reason, more government support and publicity are necessary for the promotion of Putonghua. In fact, future prospects for Putonghua are not at all dark. Although students' attitudes toward Putonghua are not as positive as those to the other two varieties at present, respondents are showing some signs of an accommodating attitude toward Putonghua, especially in the instrumental perspective. Given more time, it is to be hoped that students' attitudes will grow more positive in this regard. The political transition in Hong Kong may have been completed, yet the cultural and linguistic transitions may have just begun.

Factor 1: Integrative orientation toward Cantonese (α = 0.67).In response to comments by an anonymous referee, clarification about a reversed mean is provided as follows: If the mean for a statement is 1.88, it means that it is 0.88 away from the lowest end of the scale (i.e. 1); when reversed, it should be 0.88 from the highest end of the scale (i.e. 4). Since 4 − 0.88 equals 3.12, the reversed mean of 1.88 is therefore 3.12.

Factor 2: Integrative orientation toward English (α = 0.62).

Factor 3: Integrative orientation toward Putonghua (α = 0.75).

Factor 4: Instrumental orientation toward Cantonese (α = 0.69).

Factor 5: Instrumental orientation toward English (α = 0.6).

Factor 6: Instrumental orientation toward Putonghua (α = 0.83).

Means of the six factors.