Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 October 2006

A quantitative/interpretative approach to the comparative linguistic analysis of media texts is proposed and applied to a contrastive analysis of texts from the English-language China Daily and the UK Times to look for evidence of differences in what Labov calls “evaluation.” These differences are then correlated to differences in the roles played by the media in Britain and China in their respective societies. The aim is to demonstrate that, despite reservations related to the Chinese texts not being written in the journalists' native language, a direct linguistic comparison of British media texts with Chinese media texts written in English can yield valuable insights into the workings of the Chinese media that supplement nonlinguistic studies.

Sophisticated linguistic tools such as those used in critical discourse analysis (CDA) have long been available for the precise analysis of media texts in English. In the UK alone, much work has been done on debunking, for example, the idea that news coverage of events is the unbiased reporting of “hard facts” (e.g., Fowler 1991; Glasgow University Media Group 1976, 1980; Hall et al. 1978, 1980). The UK literature is also good on analyzing what Fowler 1991 calls the “social construction of news” through processes of selection (i.e., choices about what has “news value”) and transformation (i.e., choices about how news is presented – often linguistic choices, but also involving elements such as layout, headline size, and position in a newspaper) (e.g., Glasgow University Media Group 1976, 1980; Hall et al. 1978; Philo 1983).

Similarly, work has been done on news stereotypes and the way these reinforce themselves (Fowler 1991) and on the social and economic factors involved in news selection (Fowler 1991, Philo 1983, Cohen & Young 1973, Hall 1980). There have also been forays into contrastive functional linguistics, including attempts (e.g., Ghadessy 1988, Carter 1988) to match “situational factors” with “linguistic features” in written media texts – that is, to look at how the situational constraints (commercial pressures, expectations of target audience) acting upon a medium influence the particular linguistic choices made in presenting the news. These studies have combined to give linguists, social scientists, and media commentators a sophisticated understanding of the complex functional role the media plays in UK society.

The Western literature also contains a number of studies of the media in China. Various commentators (e.g., Li 1999, Zhao 1998, Lee 1990) have written of the comparative lack of freedom enjoyed by the Chinese media compared with the media in so-called Western societies, even in the present period, when Chinese journalists perhaps enjoy more freedom than they have for some time. Zhao, a former Chinese journalist himself, concedes that over the past decade or so there have been significant changes in the news media in China. Nevertheless, he insists that the Chinese Communist Party still retains “overt political control” of the news media, one of whose roles is to serve as a government mouthpiece. Zhao writes:

It is certainly true that the rise of mass communication, especially television, has brought profound changes to the ideological landscape. The increasing variety and liveliness of cultural entertainment forms, together with a reduced, explicitly propagandist content, has resulted in a proliferation of new symbolic forms. This does not mean, however, that the media are no longer doing ideological work or politically dominating. Indeed, the media's promotion of consumerism is no less ideological than their promotion of class struggle during the Mao era. (1998:6)

On the evidence of the literature, the roles played by the media in the two societies appear different. The mainstream government-controlled media in China – newspapers such as the People's Daily, Guangming Daily, and Economic Daily, which, according to Zhao (1998:129), are not available to buy on the streets but are subscribed to with public money and circulated in offices, classrooms, and other workplaces – are largely expected to report positive events and/or put a positive spin on other events that are reported (Zhang 1997, Conley & Tripoli 1992). When the “correct” positive line to be adopted is not apparent – for example, at times of uncertainty such as the Tiananmen crisis of 1989, when for a week disarray within the Chinese Communist Party was so complete that Propaganda Department officials did not hold their regular meetings with top Beijing editors – newspapers may be left floundering, unsure of the line to take. In the case mentioned, many ultimately adopted an ultra-cautious line (Conley & Tripoli 1992).

By contrast, the British and British-influenced press industries are commercial at heart, relying on newspaper sales to generate advertising revenue. Fowler goes so far as to say:

The main economic purpose of newspapers appears to be to sell advertising space…. Consumer advertising is based on the representation of ideal fictional worlds, i.e. sets of beliefs about desirable personal and social behaviour in relation to such products as cars, deodorants, coffee, hair care, washing powders and sweets. The texts of newspapers themselves also offer fictional model worlds, for example the obsessive discussion in the tabloids of television soap operas as if real, of actors, personalities and stars, the escapism of the travel pages in the middle class papers. (1991:121)

Where mainstream Chinese media accentuate the positive, British and British-influenced newspapers appear to thrive on conflict and on negative news stories. Thus, the then editor of the British-influenced South China Morning News – based in Hong Kong, not a million miles away from Beijing – is quoted by Knight & Nakano (1999:173) as saying; “News is conflict. News is where there is disagreement…. News is where someone puts up something and someone else on the other side says where they have problems with it.”

Unfortunately, although much useful work has been done on the role of the media both in Britain and in China, a direct linguistic comparison (at least at the level of CDA) between the media in a Western English-language society such as the UK and the media in China, though likely to yield fascinating insights into role differences between the two country's media and how these affect language choices made by journalists, has always been difficult because journalists in the two societies work in different languages. I believe, however, that a contrastive critical discourse analysis of the English-language China Daily and English-language newspapers from a Western society such as the UK may yield interesting insights into how the differing roles of the media in the two societies affect the ways in which journalists in the two countries approach the writing of texts, as evidenced by the linguistic choices they make.

Obviously, just as no single UK newspaper can be taken as representative of the UK print media in general, no single Chinese newspaper can be taken as typical of the Chinese print media generally – especially when that newspaper is not even written in Chinese. Nevertheless, I would argue that a substantial portion of the ideological and political constraints operating upon the Chinese-language media generally operate also upon the China Daily, making contrastive analysis interesting and fruitful – a claim that will be discussed further below, along with my reasons for choosing the UK Times to represent the Western print media.

The aim of this article, then, is to demonstrate that a linguistic analytic system that focuses on one specific aspect of language – what Labov has called “evaluation” – can be fruitfully applied to a comparative analysis of these particular British and Chinese print media to reveal differences between the patterns of language choices made. This, in turn, can deepen our understanding of the differences in the roles played by the media in the two societies, and it can supplement existing nonlinguistic comparisons of the two countries' media.

My general field of interest is contrastive functional linguistics. My particular aim in this study is to sketch a method for unpicking one aspect of what Carter (1988:8) describes as “the degrees of neutrality or bias which are inscribed in the choice of words which reporters make,” and to apply it to a contrastive analysis of British and Chinese media texts taken from the Times and the English-language China Daily.

The tool I have chosen for doing this is a particular aspect of language which Labov 1972 terms “evaluation.” Evaluation is an aspect of the narrative structure of a text. The term “evaluation,” Labov says, refers to “the means used by the narrator to indicate the point of the narrative, its raison d'être: why it was told and what the narrator was getting at” (1972:207).

The effect of evaluative elements is to enrich the narrative. Evaluative devices say to us: “This was terrifying, dangerous, weird, wild, crazy; or amusing, hilarious, wonderful; more generally that it was strange, uncommon or unusual – that is, worth reporting. It was not ordinary, plain, humdrum, everyday or run-of-the-mill” (Labov 1972:209).

Labov developed the concept of evaluation while studying the speech patterns of African Americans in south central Harlem, New York. In an attempt to study the way they used their verbal skills to evaluate their own experience, he asked a range of subjects, including pre-adolescents, adolescents, and adults, to record oral narratives in which they talked spontaneously, with the help of a little prompting from the interviewer, about personal experiences or events from their past. When analyzing these narratives, he identified an important element of discourse that he labeled the “evaluation of the narrative,” which broadly had to do with the way in which the speaker embellished his or her narrative to make it more interesting.

Labov identified and labeled a number of linguistic devices that narrators employed – consciously or unconsciously – to do this. They fall into four main categories, which Labov labeled intensifiers, comparators, correlatives and explicatives. Intensifiers select one of the events that are organized in a linear series in a narrative discourse and strengthen or intensify it. Intensifier devices include repetition, as well as what Labov calls “quantifiers,” such as all, some, a lot, much, many, few, all of which add emphasis. Comparators provide a way of evaluating events by placing them against the background of other events that might have happened but did not; thus, they enrich the telling of what did indeed happen. Correlatives bring together two events that actually occurred so that they are conjoined in a single independent clause. Explicatives are used to explain why or how an event happens; they are often carried out using conjunctions such as while and though, or connectives such as since or because (Labov 1972).

By analyzing the use of such elements, we can learn much about the cultural context within which a linguistic exchange takes place. They help, in a sense, to fix the immediate linguistic exchange within a much richer, deeper cultural context. They also reveal a good deal about the relationship between speaker or writer and listener or reader, and about their expectations and perceptions of each other.

Evaluation was developed in the context of analyzing African American spoken English vernacular in 1970s Harlem. It could be argued that it is a big step from that to the kind of written media discourse being analyzed here. I believe, however, that there are two reasons why the use of evaluation is justified in a study of this nature. First, the difference between the written discourse being analyzed here and the spoken discourse on which Labov was working when he developed the concept of evaluation is not as great as it at first appears. The oral narratives on which Labov worked in the early 1970s were not themselves examples of spontaneous conversation. He did try to record such spontaneous conversations in the form of face-to-face interviews, but he found that the resulting discourse was frequently interrupted and broken. Even worse, he found that because of the formal nature of the interviews, the conversation he was obtaining was over-monitored by the speakers themselves, and therefore atypical of unmonitored African American vernacular. To overcome this, and to obtain large bodies of uninterrupted, unmonitored speech, he resorted to suggesting topics to his subjects, encouraging them to talk about important events from their own past in an uninterrupted way. In this way, he wrote, he was able to produce “narratives of personal experience, in which the speaker becomes deeply involved in rehearsing or even reliving events of his past” (Labov 1972: 207).

The point here is that the examples of discourse Labov obtained were atypical of the fragmented, broken nature of ordinary unmonitored speech, containing as they did a strong, uninterrupted narrative structure. In that sense, they are not unlike newspaper texts. Labov himself developed a model to represent the structural elements that make up the kind of narrative he was analyzing, identifying six elements: the abstract, which sets out what a narrative is about; the orientation, which establishes the who, where, when, why, and what; the complicating action (Then what happened?); the evaluation (So what?); the resolution (What was the outcome?); and the coda, which signals a return to the present. I would argue that a typical news report conforms very closely to this model of narrative: indeed, with the possible exception of the coda, it could arguably serve as a good model for journalism schools to use when teaching the writing of a news report.

Second, evaluation was developed as a way of understanding vernacular narratives where the audience could not be taken for granted. The whole point about evaluative devices is that they are a way of enriching a narrative, of grabbing and holding attention. In what circumstances might a newspaper need to do this? It seems plausible that a newspaper would need to do this if its very survival depended on attracting and holding a large readership. This is certainly the case with Western newspapers such as the Times, commercial operations that rely for their economic survival on attracting advertising, which in turn is directly related to the size of the newspaper's readership. It is not the case with the China Daily, which, as will become clear, is not even available to buy on the street and is instead circulated by public subscription. This fundamental difference between the two newspapers is precisely the point of using evaluation in this study. Given that the point of evaluation is to grab attention and make a narrative interesting, we would expect a commercial newspaper like the Times to be rich in evaluation, while a publicly subscribed newspaper like the China Daily, essentially a publicly funded government mouthpiece, would not need to bother with the extra textual work that evaluation involves. The results do indeed seem to bear this out – a sufficient justification in itself for using the technique.

For reasons largely of economy of scale, this study will look at only one category of evaluation when comparing the two sets of texts being analyzed: comparators. To conduct an analysis of all four types of evaluators in an essay of this scope would be unrealistic, and an initial analysis revealed that the most interesting differences between the two sets of texts being examined occurred in the use of comparators.

Comparators add richness and complexity to a narrative by placing the events described against the background of events that might have happened but in fact did not, or events that have not happened yet. For the purposes of this study, and again for reasons of scope, I will furthermore be concerned with only three main types of comparators, those that Labov calls negative evaluators, future evaluators, and modal evaluators.

Negative evaluators – such as the element has no plans in the sentence The headmaster at William Straw's school says he has no plans to suspend or discipline the teenager – specifically place the events described in the context of what could have been the case, but in fact is not. In this sentence, William Straw's headmaster could have suspended the teenager, but in fact he has not. Future evaluators – for example, will make in The mainland will make greater effort towards furthering cross-straits ties – tend to be used when reporting on future events or developments, things that will be the case in the future but are not at present. Modal evaluators – like could be taken away in the sentence Inquiries could be taken away from (police) forces and carried out by independent investigators – make possible speculation about events that could or might or should come to be, but that are not the case at present.

Negative evaluation, as I hope will become apparent from the examples analyzed below, is a very rich and effective linguistic device for heightening and enriching the drama of a narrative; at times, it even makes it possible to construct a reportable narrative out of very little. Future evaluation is used when talking about what will be. Modal evaluation can be used in a number of ways, including speculation and also exhortation.

This study will examine the use of evaluation in a corpus of 50 texts from the Times and 50 from the China Daily. Of particular interest will be not only the difference in the frequency of use of evaluation by journalists working for the two newspapers, but also the difference in the ways they use evaluation. These differences, I believe, can be interpreted so as to throw interesting light on the different roles played by the media in China and Britain.

As already acknowledged, no single newspaper can be held to be fully representational of the print media in either the UK or China. Nevertheless, it is necessary to restrict the analysis to just a single newspaper from each culture in order to keep the study manageable, and also to reduce the problem of variation among different newspapers from the same country and hence to produce a clearer set of data for comparison. The use of a single newspaper from each culture to, in a sense, represent the media of that culture, while admittedly less than ideal, is not without precedent. Kathleen Jamieson and Karlyn Kohrs Campbell argue that it is acceptable to use “elite” newspapers to stand in for others in samples because they shape opinion in ways that others do not (Jamieson & Kohrs Campbell 1992:18–19).

The China Daily was chosen because it is the principal English-language newspaper in China. Being written in English, it is targeted mainly at non-Chinese people with an interest in China. Jean Conley and Stephen Tripoli, two American journalists who worked as sub-editors on the China Daily from 1986 to 1987, point out that “it is one of the major voices to the outside world of the People's Republic of China” (Conley & Tripoli 1992:27). Nevertheless, I would argue that it operates under many of the same cultural, political, and social constraints as other mainstream national Chinese newspapers. It is, in fact, owned by China's principal Chinese-language daily newspaper, the People's Daily, and is produced in the same building in Beijing.

Zhao 1998 distinguishes between two main categories of newspaper in China: those, mainly local evening newspapers, that are sold on the streets; and those – the major Party organs such as the People's Daily and specialized newspapers published by government departments – that are rarely sold on the streets but rather are subscribed to with public money and are circulated for consumption in offices, classrooms, and other places of work. The former, Zhao says, are largely under the direct control of the municipal Party propaganda committee, but they at least have a more diversified content than Communist Party organs and are more entertainment-oriented. The latter – to which group the China Daily, effectively an English-language sister paper of the People's Daily, certainly belongs – are much more directly under the control of the Party.

Being so closely connected with the People's Daily, the China Daily draws on many of the same sources of information as its sister paper and adopts the same line on major news items. It is written in English by Chinese journalists, whose work is then “polished” by foreign journalists working as sub-editors. These “polishers,” say Conley & Tripoli, regularly participate in daily editorial meetings but have little influence over editorial line: “Polishers had virtually no influence on, and often little knowledge of, decisions involving the most sensitive matters” (Conley & Tripoli 1992:27).

Conley & Tripoli leave no doubt about the extent of Party control over the content of China Daily: “The Party's control over the news media is exercised through the Propaganda Department, which answers directly to the Central Committee” (1992: 36). Moreover, “Propaganda officials, according to China Daily staff members, meet with media leaders regularly (usually every two weeks) to discuss news events and to deliver the Party line on how they should be covered.” Given that the China Daily is so closely associated with the People's Daily – and is so clearly subject to the same processes of Party control as its sister paper – I would argue that, even though it is written in English, its use for the purposes of this contrastive analysis is meaningful and can reasonably be expected to shed some light on the role and workings of China's national, paid-for-by-subscription Party newspapers

Similarly, I would not attempt to argue that the Times can be held to be fully representational of the full breadth and diversity of the British print media. The differences in editorial policy, target readership, style, and criteria for selection of items found among the various British print media are well documented in the literature. It is not, however, these differences in which I am interested. For the purposes of this analysis, what British newspapers have in common is more important. They are all commercial operations, which rely on selling as many newspapers as possible to generate the advertising revenue necessary for economic survival; they are independent of direct political (though not commercial) control; they appear to thrive on conflict and negative reporting; and they all generally make similar claims about wanting to inform and entertain readers. In these respects at least, I held the Times to be fairly representative of British newspapers – sufficiently representative, at least, to make a direct linguistic comparison between it and the China Daily interesting. The Times also has the advantage, from the point of view of this study, of being a broadsheet, as is the China Daily. It is, in fact, one of the longest established broadsheet national daily newspapers published in the UK, and arguably one of the country's most influential newspapers. Moreover, at the time of gathering materials (1998), it was the British newspaper most readily available on the Internet.

A total of 50 reports each was analyzed from the Times and from the China Daily. Certain criteria were used when selecting particular newspaper texts for analysis, so as to maximize points of comparison between the two sets of texts. These criteria were as follows: articles were to be between 200 and 600 words in length, about “home” news (i.e., British news for the Times, Chinese news for the China Daily), and published over the Internet in the period January to March 1998. The first 50 texts from each newspaper that I found on the Internet that met these criteria were chosen for the analysis.

The approach to analysis and interpretation of data texts adopted here is essentially what Grotjahn 1987 describes as a “Paradigm 7” approach to research in applied linguistics – that is, an exploratory or nonexperimental, quantitative, interpretative approach. The 100 newspaper texts were analyzed and instances of negative, future, and modal comparator evaluation recorded and tabulated. The data for the two sets of texts were then compared for evidence of quantitative differences in the use of evaluation. To complement this quantitative approach, texts displaying particularly interesting usages of certain types of evaluation were also analyzed qualitatively, and the results of the combined quantitative and qualitative analyses were used to shed further light on role and cultural differences between the two media.

The results of the quantitative analysis are summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14. In what follows, I will first highlight some of the most striking quantitative differences between the two sets of texts. I will then attempt to interpret these differences qualitatively by examining in some detail texts that display interesting features, looking at evaluators of each category in turn.

Frequency of negative, future and modal comparators in Times and China Daily texts.

Frequency of comparators in Times and China Daily texts: words/comparator.

Frequency of negative, future and modal comparators in the Times and China Daily (words/comparator).

Spread of negative, future and modal comparators in the Times and China Daily.

Breakdown of comparator evaluation found in Times and China Daily by direct speech, reported speech, and narrative text.

Negative evaluation found in Times article 38, and its attribution.

Negative evaluation in China Daily article 20 and its attribution.

Negative evaluation in the Times and China Daily: direct speech, reported speech, and narrative.

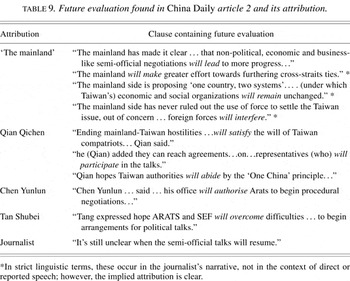

Future evaluation found in China Daily article 2 and its attribution.

Future evaluation in the Times and China Daily: direct speech, reported speech and narrative.

Future evaluation found in Times article 22 and its attribution.

Modal evaluation in Times article 31 and its attribution.

Modal evaluation in China Daily article 2 and its attribution.

Modal evaluation in the Times and China Daily: direct speech, reported speech, and narrative.

It is clear from the quantitative analysis that, overall, use of negative, future, and modal comparators is higher in the Times texts than in the China Daily texts. There are just 227 instances of such comparators to be found in the 50 China Daily texts altogether, compared to 434 in the 50 Times texts (see Table 1). On a standard t test of significance, the probability P that such a result is random over a sample of this size is P = 0.00011. The result is significant.

The greater number of comparator evaluators found in the corpus of Times texts is not simply a function of the greater word length of the Times texts. The average length of Times texts analyzed is 400 words, and that of China Daily texts 332 words. Even so, Times texts show an instance of comparator evaluation on average once every 46.1 words, and China Daily texts on average once every 73.1 words (see Table 2). Here, the probability P that such a result is random over a sample of this size is P = 0.01827, again significant.

Even more interesting than this general difference in use of comparator evaluation, however, are the differences in frequency of occurrence of each particular type of comparator evaluator analyzed. Negative evaluators appear in the Times on average once every 187 words, compared to once every 395 words in China Daily; future evaluators appear once every 144 words in the Times, and once every 155 words in China Daily; and modal comparators appear once every 106 words in the Times and once every 213 in China Daily (see Table 3). What the breakdown appears to show is that, although the frequency of use of future comparators is roughly the same in both sets of texts, the frequency of use of both negative and modal comparators in the Times is roughly double that in the China Daily. A t-test of significance reveals that the differences in frequency of occurrence of both negative and modal evaluators between the two sets of texts are highly significant (P = 0.000831 in the case of negative evaluators, and P = 0.006012 in the case of modal evaluators; hence the differences are not likely to be random over a sample of this size). Only in the case of future evaluators, where P = 0.097584, is the difference between the two sets of texts not significant.

It is also interesting to compare the spread of use of comparators between the two sets of texts. The analysis reveals (see Table 4) that the use of negative, future, and modal comparators in the corpus of China Daily texts is “clumpy: that is, a relatively large number of comparators appear in a relatively small number of texts, with many texts showing no use of comparators at all. In the corpus of Times texts, however, comparator use is spread more evenly throughout the texts. Thus, in the Times corpus there are only two texts (4% of the total) that display no use of negative, future, or modal comparators at all, compared to nine (18%) of China Daily texts. Yet the top five China Daily texts in terms of frequency of use of negative, future, and modal comparators contain 33% of all such comparators found in the China Daily corpus, compared with 24% in the top five Times texts (see Table 4).

The comparison is even more interesting when broken down into negative, future, and modal comparators. Only 18 of 50 (36%) of China Daily texts contain any negative comparators, compared to 40 of 50 (80%) of Times texts; 33 of 50 China Daily texts (66%) contain future evaluators, compared to 37 of 50 (74%) of Times texts; and 21 of 50 (42%) of China Daily texts contain modal evaluators, compared to 44 of 50 (88%) of Times texts. Again, while the pattern of use of future evaluators is similar between the two sets of texts, the use of negatives and modals is quite different.

There is one final breakdown of the statistical data that deserves consideration before we look at the texts in more detail. The negative, future, and modal comparators that occur in each of the sets of texts were categorized into three types: (i) those that occurred in direct speech (and hence were purportedly the actual words of a person who was being reported on, selected but otherwise uninfluenced by the journalist reporting them); (ii) those that occurred in indirect or reported speech (supposedly a representation of a speaker's own words, but with a chance for a reporter to add his or her own slant or color); and (iii) those that occurred in the narrative (and hence can be taken to be entirely the result of the reporter's or editor's own choice).

What the results appear to show (see Table 5) is that in the Times corpus, relatively more evaluation appears to occur in the narrative (51% of all instances); while in China Daily more evaluation appears in reported speech.

Since the effect of evaluation is to enrich a narrative, to make it more dramatic and interesting, and since a dramatic, interesting narrative can be expected to be of importance to a commercial newspaper such as the Times, it is tempting to infer from this result that one reason for the greater use of evaluation in the Times texts is that journalists are themselves employing it in their own narrative in an attempt to brighten up their writing. However, a more detailed breakdown of the figures, as will be shown later, reveals that the pattern is rather more complex than this.

To attempt to understand the patterns that the quantitative data reveal, I will now look more closely at the texts themselves, considering each category of evaluator in turn.

Negative evaluators serve to place the narrative action against a background of events that did not, in fact, happen, but that could have happened. Examples of this are given in the texts analyzed below. One effect of placing narrative events against a wider contextual background is to heighten the dramatic impact of a narrative – by making the reader aware, for example, of how lucky or improbable the actual sequence of events was.

The quantitative data reveal that use of negatives is considerably higher in the Times articles than in the China Daily articles. There are 107 instances of negative evaluation in The Times texts, compared to just 42 in the China Daily. Negative evaluation occurs on average once every 187 words in The Times, but just once every 395 words in the China Daily.

As we have seen, these differences are statistically significant. A closer look at some of the texts displaying a very high or very low incidence of negative evaluation gives insight into why they may exist. The Times text showing the greatest degree of negative evaluation (nine instances altogether, excluding the headline) is Times article 38. Headlined “School will not punish Straw's son,” it is an account of how the headmaster of the school at which Home Secretary Jack Straw's son William was a pupil said he would not punish the boy for selling marijuana because he had been punished enough already by the media publicity. Interestingly, there is even a negative in the headline, which gives some indication of the way in which things will go.

The negative evaluators found in the text are set out in Table 6.

The first thing that is striking about this article is that the whole narrative is predicated on a negative. The very first paragraph says that the headmaster has no plans to suspend or discipline the teenager. Selling marijuana is not very serious, it is not the end of the world, and while Jack Straw wishes the incident had not happened, police are not taking any action, and anyway, say William's fellow pupils, the boy doesn't deal and would never buy drugs. The entire story is in fact about nothing happening. But if there is nothing happening, where is the story? The story is in the denial; which is to say, it is in the negative evaluation. By beginning the article with the statement that the headmaster has no plans to suspend or discipline the teenager, the journalist immediately raises in the reader's mind the possibility that the headmaster was seriously considering doing so but has decided not to. In other words, the story is in what might have happened but didn't. The reader is left wondering what would have happened if the headmaster had decided otherwise – and is also left with the feeling that because the head teacher has spoken out to say he was not intending disciplinary action, and because a newspaper thought that decision worth reporting, the possibility that the headmaster might have decided otherwise was a very real one.

Much the same is true of the other, subsidiary negatives that support the remainder of the story. When Jack Straw says he wishes the incident had not happened, it reminds readers that it did and emphasizes the fact that it was a serious matter. When a pupil insists there is no stigma about buying drugs, it makes readers feel that there is, or why does the pupil even need to bother denying it? When the police are said to have recommended no action, it makes the readers realize that they could easily have done so, and that this would have been a serious matter.

In all these cases, negative evaluation is being used to contrast what is with what might have been. But this contrast is being achieved in different ways. In some instances, it is used to create a reportable narrative description of a situation in which there is no real narrative action at all. Thus, in the clause The headmaster at William Straw's school says he has no plans to suspend or discipline the teenager, the fact that the head teacher has no such plans itself becomes a positive, reportable act, and the fact that he is not taking punitive action is contrasted with the possibility that he might have decided otherwise. In other instances, negative evaluation is used to turn a denial (rather than an absence of action) into a reportable act, thereby making it possible to state precisely that which is being denied. Thus, a schoolmate of William Straw says, Will doesn't deal. He would never buy drugs – and by reporting those words, the journalist raises in the mind of the reader the possibility that perhaps William might after all. In yet other instances, negative evaluation is being used for dramatic emphasis. I really don't think it is the end of the world, says the head teacher, and by saying so somehow manages to imply that it almost was. It was inevitable for a parent to … . wish the incident had not happened, Jack Straw is indirectly reported as saying, emphasizing once more how serious was the fact that it did.

The reason this story is newsworthy, even though it is actually about nothing happening, is that the main protagonist is the son of an important and powerful man. The importance of the protagonist means the journalist considers it worthwhile to use certain linguistic techniques (including negative evaluation) to construct a reportable narrative even when very little has actually happened. The technique employed here of using a negative (or series of negatives) to do this is one that, I would argue, is commonly used by Western journalists. If there is a rumor about a scandal involving a famous person and it can't be proved, get the person in question to deny it, and you've got your story.

Is the pattern of use of negative evaluation found in Times article 38 repeated in other Times articles showing comparatively high use of evaluation? Essentially yes. Times article 5, which has seven instances of negative evaluation, is headlined “Blair condemns Diana stories.” A look at a few instances of negative evaluation in the article reveal that, again, it derives much of its drama and richness from the contrast between what is and what might have been. Thus: Blair's staff said his remarks should not be seen as criticism of Fayed constitutes a denial which itself becomes a reportable act and allows what is being denied to be repeated, prompting instant speculation that what is being denied might actually be the case. [Fayed] told a newspaper he … did not believe the crash was an accident emphasizes that there was more to the crash than meets the eye, by contrasting the current belief that it was an accident with the possibility that it was not. He [Blair] is not singling out any individual or enterprise, insisted one spokesman is another denial, leaving the lingering suspicion that Blair may be doing precisely what the spokesman says he is not doing, a suspicion reinforced by use of the verb insisted, with its rather negative overtones. Blair has not discussed his views of the speculation surrounding Diana's death with the Prince of Wales makes a “positive out of a negative,” like William Straw's headmaster is not going to take disciplinary action; the journalist is able to make something positively reportable out of the fact that Blair has not done something simply by reporting that he hasn't done it.

Much the same pattern is seen in Times article 40, headlined “Queen pops into haunted local,” which also contains seven instances of negative evaluation. Here, we are told that there was no sign of Nancy the resident ghost – a sentence that neatly establishes the apparent fact of the ghost's existence by saying she wasn't there. Later, the pub's landlady is quoted as saying, “I did not offer her a drink and she [the Queen] did not ask for one;” by saying so, she succeeds in efficiently making a narrative out of a complete absence of event by contrasting actual with potential happenings.

Although the Times articles generally use more evaluation than the China Daily texts analyzed, there are Times texts that display little or no evaluation. One such is Times article 48. The article, headlined “Relatives see film of sunken trawler,” is an account of an inquiry into the sinking of a ship, the Westhaven. The events being investigated are actually very dramatic, but the report is distant and impersonal: a mere recital of facts rather than a colorful narrative. Thus, The boat was dragged to the seabed so quickly that one of the liferafts was caught in the mast and a second failed to inflate. Mr Pattison and his crew, Alan Cunningham, 28, Chris Prouse, 23, and Mark Hannah, 30, died. There is no attempt here to get into the minds of the crew as they died; no “they could not get to safety because the liferafts failed.” The story is allowed to tell itself, and the suffering of the men is left to the reader's imagination. The contrast with the evaluatively rich articles analyzed above – which are actually reports of far less dramatic events – is great.

Negative evaluation, clearly, is a rich and effective linguistic device for heightening and enriching the drama of a narrative – and even for constructing a narrative out of little or nothing. It does this essentially by contrasting what is with what is not but might have been. There are a number of ways in which this is achieved in the articles so far considered: by making a positive out of a negative and creating a reportable narrative description of a situation in which there is no real narrative action at all; by turning a denial into a reportable act, thereby making it possible to state precisely that which is being denied; by reminding us of what might have been and so increasing dramatic emphasis; and by heightening dramatic tension by contrasting two different possible realities (as in Fayed's saying he did not believe the crash was an accident).

Negative evaluation is comparatively rare in the China Daily texts analyzed, and, as the quantitative data reveal, its distribution through the corpus of texts is comparatively clumpy. Of the 50 texts analyzed, 32 contain no negative evaluators at all, while the top five texts in terms of frequency of negative evaluation contain 52% of all instances of negative evaluation found in the corpus.

The China Daily text that displays the greatest use of negative evaluation is text 20. This text, headlined “Beijing tightens control over fireworks in city proper,” contains no fewer than eight instances of negative evaluation – almost one-fifth of the total for all 50 China Daily texts studied. The instances of negative evaluation that occur are set out in Table 7.

Clearly, there is an element here of “what is” being contrasted with “what is not, but might have been”: The officially arranged fireworks displays ought to have been a pacifier (what is not) but actually became a fuse sparking further trouble (what is); no fireworks-caused fires have been reported (what is), but they might well have been (what is not, but could have been).

Equally clearly, though, there are no examples in this text of negative evaluators being used to bolster or brighten a narrative, as is often the case in the Times articles – no turning of denials into reportable fact, no making a positive out of a negative to create a narrative where really there is none (unless the people's congress ruled that no firecrackers would be allowed is counted). The tone imparted by the negatives here is one of disapproval – almost as though the authorities, through their mouthpiece the newspaper, are saying, “This is what we warned would happen if you behaved like this.”

The China Daily text displaying the next highest use of negative evaluation is text 42, headlined “Mainland to export live chickens to Hong Kong.” The article is an account of attempts by the Chinese government to resume export of chickens from southern China to Hong Kong following a scare (prophetic, in the light of SARS) caused by an outbreak of avian flu. It contains five instances of negative evaluation: the chickens will not reach markets until Sunday; the price for live chickens is not expected to increase greatly; no case [of avian flu] had been detected either in humans or among poultry in Guangdong Province; no case of humans infected by the bird flu has been reported; although no cases of A H5N1 bird flu in human beings and chickens have been reported…. Guangdong will further tighten its testing.

What is notable about these cases of negative evaluation is that they are all, without exception, flat statements of fact, presented with the ring of absolute authority. China Daily text 42 in fact reads, to Western eyes, more like a government press release than an independent news report. The litany of no cases somehow has the effect of bludgeoning the reader into acceptance of what is said rather than, as is the case in Times articles rich in negative evaluation, raising in the reader's mind the possibility that what is denied may actually be the case.

The difference may have something to do with the way in which negative evaluation in the Times texts tends to be personalized, whereas in the China Daily it is not. In Times text 38, about Jack Straw's son, all but one of the instances of negative evaluation occur in the context of either direct or reported speech, and hence the denial which it represents can be attributed to an identified individual (the headmaster, Philip Barnard; Jack Straw himself; three unnamed but distinct fellow-pupils of William Straw) (see Table 6). Much the same is true of Times text 5, “Blair condemns Diana stories,” where, variously, Tony Blair's staff, Blair's spokesman (and indirectly through him, Blair himself), and Mohamed al-Fayed are all associated with denials.

In the few China Daily texts that display relatively high use of negative evaluation, this is not the case. In China Daily article 20 about firework controls in Beijing, negative evaluation is associated with, in order: a 1994 regulation ratified by the city people's congress (the city people's congress ruled that no firecrackers would be allowed); what appears to be a rather preachy authorial expression of opinion (However, the displays became not a pacifier but a fuse); other apparent authorial statements of fact that are actually drawn from a report in the Beijing Youth Daily, which is itself based upon a report from the Beijing Fireworks Ban Office; and statements by a generalized category of doctors, the authority for which also comes ultimately from the report in Beijing Youth News (see Table 7).

This depersonalization of negative evaluation is equally marked in China Daily text 42, where it is indirectly associated with two sources; the World Health Organization and Guangdong Province's poultry export agency, the Guangnanhang Company. The effect is to give an air of authority to the denials, to institutionalize them so that the reader feels he or she has little choice but to accept them. The effect of the personalization of negative evaluation as found in the Times, by contrast, is to heighten the sense of human drama, and simultaneously to decrease the authoritativeness of the denials (since a denial by a single, fallible human will always carry less weight than one by an institution the size of the World Health Organization).

Given the contrasting role played by the Times and China Daily in their respective societies, it would seem reasonable to predict that this pattern of personalization and depersonalization of negative evaluation would be repeated throughout the corpus of Times and China Daily texts. If so, we might expect to find that the proportion of negative evaluators that occur in the context of direct or reported speech is higher in the Times texts than in the China Daily.

The quantitative data summarized in Table 5 above revealed that, in general, comparator evaluation in the context of direct and reported speech was proportionally less likely to be found in the Times than in the China Daily. Specifically, just 49% of negative, future, and modal evaluation in the corpus of Times texts occurred in the context of direct or reported speech, compared to 60% per cent of that found in the China Daily texts. This seems counter to what might be expected on the basis of the discussion above. Break the data down, however, and the picture is different. In regard to negative evaluation, a significantly higher percentage occurs in the context of direct or reported speech in the Times (69% of all instances) than in the China Daily (43% of all instances) (Table 8). This would seem to support the conclusion that the pattern of personalization and depersonalization of negative evaluation noted above is repeated throughout the corpus of texts.

There is one other interesting aspect of the China Daily articles examined above. In each case, most instances of negative evaluation that occur appear to be used in the context of the narrative of the text itself; in other words, they appear to be in the journalist's own “voice.” Closer examination of the texts, however, reveals – as noted above – that while they may appear to be authorial statements of fact, in truth there is a specific authority given for these statements. China Daily article 42, about avian flu, is a good example. The litany of no cases appears to be simple statements of fact in the author's own voice, but in fact, it is clear that the information actually derives from the World Health Organization.

As Table 3 shows, the Times texts analyzed use approximately twice as many negative and modal evaluators as the China Daily texts. Future evaluation, however, is different in that there is no significant difference in the frequency with which it is used in the two sets of texts (a future evaluator occurs on average once every 144 words in the Times, once every 155 words in China Daily). This is not, on the face of it, what might have been expected. So what is happening?

Future evaluators serve to place the narrative action – the actual sequence of events, taking place now or in the recent past, that are the subject of the narrative – in the context of events that have not yet happened but could happen in the future. They serve to contrast the now with the maybe, or the could be, or with what we want, hope, or expect might come to be.

In common with most other comparators, they heighten the interest of a narrative by placing it against a rich background of other events that have not actually happened, but could. It is not surprising, therefore, that they are one of the more commonly used forms of evaluation found in the Times texts. But why are they so widely used in the China Daily?

A closer examination of the China Daily texts that are richest in use of future evaluators gives some clues. These are China Daily article 2 with 11 instances, and China Daily articles 13 and 28 with nine instances each. China Daily article 2, headlined “One country, two systems,” is a clearly political piece stressing the importance of closer ties between the Chinese mainland and Taiwan. It is a comparatively long article, which might in part account for the number of future evaluators, but nevertheless, the way in which these evaluators are used is interesting. The instances of future evaluation found are set out in Table 9.

The future evaluators used here express plans, intentions, and hopes for the future. More generally, when taken together, they add up to a political vision of the future – a vision held by senior Chinese Party officials. If such and such happens, they say, then so and so will also happen, as a consequence of such and such or as part of a plan. The vision of the future held out here is implicitly contrasted with the present; implicit in the whole text is the sense that things are not, at present, the way the Party would like them to be. A better future will be the reward if certain things are done, runs the message.

China Daily article 13, headlined “New fares to encourage residents to take taxis,” is about a much less politically sensitive and important issue – promoting the use of taxis to take some of the strain off Shanghai's public transport system – but it still clearly encapsulates a vision of the future. Thus: Next month, taxis will charge ten yuan … . instead of 14.4 yuan; each kilometre after the first three … will be charged at two yuan; people who take a taxi seven kilometres or less will be paying slightly less; taxi drivers … say the change will hurt business; “The new pricing member will have a great impact on us,” said [taxi driver] Xiao Li; “I will earn just 30 yuan”; Bargaining will only result in unfair competition.

Here, a local government policy is being set out; we are being told simply what will come to pass. Interesting here is the fact that a voice of dissent is allowed to intrude: taxi drivers say the move will hurt their business, and that they will be worse off as a result of it. Such a voice of dissent is comparatively rare in the Chinese texts analyzed. It has perhaps been allowed here because the issue is not seen as a very important or sensitive one.

Finally, China Daily article 28, headlined “Chongqing plans ambitious move,” sets out another vision of the future – the city of Chongqing's plans to attempt to compete economically with Shanghai. Here we see future evaluators in clauses such as the following: Chongqing will provide more favourable conditions for foreign investors; “We will make Chongqing one of the best investment choices in China; more workers will be laid off from State-owned enterprises; the municipal government seems confident the problems will be solved. Again, intention and aspiration is the order of the day, with the repeated use of the future will implying a firmness and singleness of purpose that will brook no argument.

In the China Daily texts, then, future evaluators appear in the context of articles that set out official visions of the future. Doubts are occasionally allowed to creep in (taxi drivers fear they will be worse off; workers will be laid off), but the overall tone of the articles expresses firmness of purpose and planned progress, moving forward toward a planned better future.

A possible explanation for the comparatively frequent use of future evaluators in the China Daily texts, therefore, might be that the China Daily, in its role as mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, is seeking in the articles in which such future evaluation is found to present the authorities' plans for a better future, and to portray the events of today as though they are taking place on the road toward a definite future goal.

This is reinforced by the fact that, unlike in the case of negative evaluation, the greater proportion of future evaluators in the China Daily texts occur in the context of either reported or direct speech; in other words, they are personalized. A total of 62% of instances of future evaluation found in the China Daily occur in the context of either reported or direct speech (see Table 10). What we are seeing, I would suggest, is senior party or other authority figures giving their views about the way forward.

China Daily article 2, discussed above, is a good example of this. Of the ten instances of future evaluation found, five occur in the mouths (in the context of either direct or indirect speech) of three named senior officials: Chinese foreign minister Qian Qichen; Chen Yunlun, director of China's Taiwan Affairs Office; or Tang Shubei, vice-chairman of the Association for Relations Across the Straits, Arats (see Table 9). Four more, though not all necessarily strictly in the form of reported or direct speech, are clearly associated with a shadowy authority referred to only as the mainland, which in the context of this article refers to the government of the People's Republic of China, and thus to the Communist Party. Only one is genuinely in the voice of the journalist: the brief statement It's still unclear when the semi-official talks will resume.

This personalization of future evaluation does not appear to occur to the same extent in the Times texts analyzed. While the frequency and spread of use of future evaluators in the Times appears, from the initial quantitative data, to be superficially similar to that in the China Daily, Table 10 reveals that, in contrast with the China Daily, only 15% of instances of future evaluation occur in the form of either direct or reported speech. The vast majority appear directly in the narrative.

The Times article displaying the greatest use of future evaluation is text 22, headlined “Middle class to foot bill for Budget reforms.” Here, future evaluators occur no fewer than 24 times. Of these, however, 20 are in the journalist's own voice. Just four occur in the form of readily attributable direct or reported speech (the one example marked * occurs in the narrative voice but can be reasonably attributed) (see Table 11).

Times text 22 is a preview of Chancellor Gordon Brown's first full budget, and the repeated use of futures is a result of predicting what the chancellor will do. It is certainly not a negative or hostile piece; rather, it is a speculative piece such as is not uncommon in the British press. Presumably the journalist has some grounds for writing what he or she has (possibly based on an advance copy or summary of the chancellor's speech, or on an off-the-record briefing by an aide, a supposition supported by two quotes directly from an unnamed source), but there is almost no attempt to attribute any of the information given. It is almost all delivered, quite flatly, in the reporter's own voice. The effect of this, I would suggest, is to distance the newspaper from Gordon Brown's plans, thus allowing it to stand back from them and assess or analyze them in what appears to be a more independent and objective manner.

The contrast with the way future evaluation is used in China Daily texts is clear. There, it occurs in the context of reported or direct speech attributable mainly to named individuals or organizations. The effect is for those organizations or individuals to be able to claim ownership (and hence credit) for the plans or intentions being reported, and at the same time to make the newspaper seem supportive of them. The Times, by reporting such plans in the form of simple statements of fact in the author's own voice, actually manages to sound more distant and skeptical about them, and is able to place them in the context of an article which appears to be weighing the merits of the plans in the balance.

The same is true of other Times texts. The one showing the second greatest use of future evaluation is text 50, headlined “Tax credit for poorer families will go to women,” which contains 11 instances. They include: A new tax credit to top up the income of lower paid families will now go automatically to women; couples will fill out a joint form, which will include a box which women can tick; the new credit will also include a special payment for childcare; It will be more generous than the family credit. Again, we see little or no attempt to place the facts stated in the voice, direct or indirect, of any government official or spokesman, allowing for a more distant, skeptical, and analytical article.

The third type of comparator being looked at here is the modal evaluator. In traditional grammar, modals in English mainly indicate the attitudes, abilities, or opinions of the subjects of a particular clause toward the actions or states described in that clause. These attitudes or abilities may include willingness (I would love to go if the weather's OK); ability (he can read: I can't); obligation (you must go); permissibility (you may go); possibility (you might be able to get there that way); and volition (I will go!). Here, though, we are examining the role of modals as comparators: deliberate linguistic choices made by the narrator to enrich the actual sequence of events reported on by setting them against a wider background of things which may, or could, or will, or must, or can't happen.

A look at the quantitative data reveals that the Times articles analyzed use over twice as many modal evaluators (188) as the China Daily articles analyzed (78) (see Table 1). Again, this is not principally a function of the longer length of the Times articles. Even when the slightly shorter average length of the China Daily texts is taken into account, modal evaluators appear twice as frequently in the Times texts analyzed (on average once every 106 words) as in the China Daily texts (once every 213 words) (see Table 3). As we saw, these differences are highly significant. Use of modal evaluation is also more evenly spread through the corpus of Times texts than is the case with the China Daily texts. 88% of all Times texts analyzed contain a modal evaluator, compared with just 42% of China Daily texts; the top five Times texts contain 32% of all modal evaluators found in the corpus, compared to 46% in the top five China Daily texts (see Table 4).

Clearly, the pattern and frequency of use of modal evaluation is quite different in the Times texts and China Daily texts analyzed. But why?

The Times article showing the greatest use of modal evaluation is Times article 31, which contains 15 instances. Headlined “Outside agencies may investigate police complaints,” the article is an account of proposals to take away responsibility for investigating complaints against the police from the police themselves and instead to appoint independent investigators. Modal evaluation found is set out in Table 12.

Here, as was the case with future evaluation, we are looking at a text that is talking about a vision of a possible future. Implicit in the story is a contrast between the situation now – in which the police themselves handle complaints made against them – and what the situation could be in the future, with those complaints handled by external investigators. The difference between the vision of the future expressed here and the visions of the future expressed using future evaluation in the texts analyzed earlier is that here we are talking not about definite plans for the future, but about possibilities – something that participants would like to bring about, if it were possible. There is a lesser degree of certainty implied in this possible vision of the future than if future evaluators had been used. If, for example, Jack Straw had said Inquiries will be taken away from police forces, that would have been a definite intention, a planned future move. By saying they could be taken away, he is talking about something that may happen, but also may not.

Times article 46, headlined “Irvine calls for curbs that would suppress Cook story,” shows the second highest usage of modal evaluators (13 instances). This is an article looking at the impact of new curbs on press freedom being called for by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Irving. Modal evaluators include the following: Robin Cook's affair with his mistress … would not have been disclosed under new curbs; people could go to the commission and ask it to stop stories being published; In an interview … Lord Irvine is asked if he would have expected the commission to order the News of the World not to print the story; “I would hope that that would be the view that the PCC would form in a case like that,” he said.

Here, again, we have a vision of a possible future that is contrasted sharply with the reality of the today of the article. Robin Cook's affair was in fact reported, but it would not have been if the suggested new curbs on press freedom had been in place. Again, though, the use of modal evaluators lessens the sense of certainty or inevitability that this vision of the future will come about. People will be able to go to the commission would have implied this will be the case; people could go to the commission implies it may be the case if something else also comes to be – here, clearly, if the Press Complaints Commission issues tough new privacy guidelines. In this article, the lack of certainty appears to derive from the fact that it is not Lord Irvine himself who has the power to issue such guidelines. He can only call upon the Press Complaints Commission to do so.

Times texts 19 and 30, both comparatively rich in use of modal evaluators, show a similar pattern. Text 19, headlined “Supermarket and hospital car parking may be taxed,” is an account of government proposals to levy a tax on parking spaces, but these are only measures being considered. Thus, we read The money would probably be levied voluntarily and the proposed charge could raise £650 million. Times article 30, headlined “Police chiefs get power to sack corrupt officers,” is a story about definite powers to be granted by Home Secretary Jack Straw. It does therefore include future evaluators (The Home Secretary will announce the biggest shake-up of the handling of police complaints). Where the modals begin to appear is when the journalist begins to speculate about precisely what the shake-up will mean: If officers refuse to answer questions this could be used against them; Officers who are lazy or incompetent could also find themselves facing the sack. In the Times articles, then, modal evaluation clearly is being used primarily to describe a vision of a future, but a possible, or wished-for, or speculative vision of the future rather than a planned, intended one as is the case when future evaluation is used.

Modal evaluation occurs considerably less frequently in the China Daily texts than in the Times texts, but it does occur. A closer look at the China Daily text displaying the greatest use of modal evaluation – article 2, headlined “One country, two systems,” about the importance of improved business and economic relations with Taiwan, which contains 10 instances – reveals, however, that this device is not being used in the same way as in the Times. China Daily article 2 – also the Chinese text that displays the greatest use of future evaluation – clearly sets out a vision of a better future. But the modal evaluators found tend to be those of obligation, rather than of possibility as in the Times texts (see Table 13).

All but one of the modal evaluators found in China Daily article 2, in fact, is a modal of obligation such as must, can, or should; and, as Table 13 shows, most of them are directly attributable to a senior government source, China's then vice-premier and foreign minister, Qian Qichen.

The contrast with the type of modal evaluation found in Times article 31 is interesting. As with the China Daily text, most of the modal evaluators found in Times article 31 are attributable to a senior government source, in this case Jack Straw, then home secretary. But the types of modals used by Straw are almost exclusively modals of possibility or speculation. Straw uses only a single modal of obligation (bad officers must be dealt with) and the Commons Select Committee on Home Affairs another (the Home Office should look at) (see Table 12).

This difference in types of modal evaluators possibly says as much about the relationship between the government and the governed in the two societies as it does about the roles of the media. The pattern of China Daily texts using modals of obligation and Times texts using modals of speculation is, however, repeated throughout the corpus of texts. Of the 74 modal comparators found in the China Daily texts, 52 (70%) are modals of obligation such as must, can, or should. In the Times texts, just 30 out of 186 (16%) of modal comparators are modals of obligation. The vast majority of modal comparators in the Times texts (145/186, or 78%) are those of possibility or speculation (would, could, may, might). This compares with just 22/74 (30%) of the modal comparators in the China Daily texts.

Given the probing, speculative nature of much Western reporting, it might be expected that one reason for the large proportion of modals of speculation found in the Times corpus is that they occur in the context of the narrative and are the result of the journalist's speculating on, for example, what certain government proposals might mean. There are indeed a couple of examples of this kind of use in Times article 31 (new legislation … would take some time to arrange). By and large, however, as Table 14 reveals, it is not the case that significantly more modals of evaluation occur in the context of narrative as opposed to direct or reported speech in the Times than in the China Daily. In the Times, 38% of modal evaluators occur in the context of narrative; in the China Daily, this is only slightly lower, at 33%.

A contrastive, quantitative/interpretative analysis of 50 texts from the Times and 50 texts from the China Daily has revealed that there are interesting differences in the ways in which evaluation is being used in the two sets of texts. These can, I believe, be plausibly interpreted in the light of the different roles played by the two newspapers in their respective societies.

The Times belongs to the Western tradition of journalism. It is commercial, relying on newspaper sales to generate advertising; it is independent of direct political (though not commercial) control; it thrives on conflict and negative reporting, including adopting a questioning, skeptical attitude toward the words and actions of authority figures. Claims of the Western media to provide unbiased reporting of hard fact have, however, been widely debunked.

The China Daily is quite different. Despite being published in the English language, it belongs to a group of Chinese newspapers subscribed to with public money and generally under the close control of the Communist Party. Party control is exerted on the China Daily and other publicly subscribed Chinese newspapers through the Propaganda Department. It is written in English by Chinese journalists, whose language is “polished” by foreign sub-editors. These foreign “polishers,” however, have no say on the editorial line. Effectively, the China Daily serves as a mouthpiece for the Party in its efforts to communicate with the wider world. As such, in common with other publicly subscribed newspapers, it is generally expected to report positive events and/or put a positive spin on other events reported.

The effect of evaluation is to enrich a narrative; to make it more dramatic and interesting. It is unsurprising, then, to find that the Times, which relies for its economic survival on selling newspapers, is richer in use of evaluation than the China Daily, which does not. This, however, is a comparatively trivial finding. Of much more interest are the differences in the ways in which particular types of evaluative comparators are used.

Negative evaluation in the Times is twice as common as in the China Daily, and moreover it is used in a quite different way. The Times needs to develop stories about people its readers are perceived to be interested in, and to write those stories in a style that is entertaining and dramatic. Use of negative evaluation in the Times reflects this, effectively heightening and enriching the narrative, or even making it possible to construct a narrative out of nothing. The fact that a good proportion of negative evaluation found in the Times is personalized only heightens the sense of drama; the reports involve real individuals involved in real crises.

In the China Daily, use of negative evaluation is quite different. It is far less common, and when it is used, it is more often than not depersonalized; well over half of all instances occur in the narrative rather than being attributable to an individual, and even where attribution is possible, it is often to an organization rather than an individual. Negative evaluation here occurs largely in the context of flat statements of fact, presented with the ring of absolute authority. This is exactly what might be expected from a mouthpiece for an authority such as the Chinese Communist Party.

Future evaluation appears in both sets of texts in the context of articles about future plans and intentions. Future evaluators appear with a similar frequency in each set of texts, but again, the way in which they are used is different. In the China Daily, future evaluation appears in articles that present an essentially political vision of a better future. Future evaluation is largely personalized; almost two-thirds of instances occur in the context of either direct or reported speech, and even many of those that appear in narrative are directly or indirectly attributable, often to a government official or body. The effect is to give the named Party individuals or organizations ownership of the plans being expressed. In the Times, future evaluators also appear in the context of articles about the future. Here, however, future evaluation is depersonalized. The vast majority of instances – 85% – occur in the narrative, and there is often little attempt to attribute the information about future plans that is presented. The effect is to distance the newspaper from those plans, and to allow it to appraise them in what appears to be an independent manner. Again, the differences in use of future evaluation fit well with what might be expected given the different role of the two newspapers.

Modal evaluation appears about twice as frequently in the Times as in the China Daily. Again, instances appear in the context of articles that discuss future plans. The key difference between the two newspapers is that in the Times, the evaluators tend to be modals of speculation – this might happen – whereas in the China Daily, they are modals of obligation – this must or should happen.

This, again, is what might be expected given the different roles the two newspapers play. In both sets of texts, however, the majority of modal evaluators are attributable, occurring in the context either of direct or reported speech. It may be that the difference in use of evaluators therefore says as much about the relationship between authority figures and those they have authority over (i.e., those their remarks are addressed to, either directly or through the medium of the newspapers) as about the role of the two newspapers themselves.

These are all interesting findings in themselves. The wider significance of this study, however, is that it demonstrates that the sophisticated tools of critical discourse analysis, which have been applied so fruitfully to analysis of the English-language media and have added so greatly to our understanding of the way those media operate, can also be applied usefully to analysis of Chinese media, albeit Chinese media written in English. This makes it possible to supplement nonlinguistic studies of the Chinese media with studies conducted upon hard linguistic grounds, as well as making possible contrastive studies, such as this one, in which certain sections of the Chinese media can be directly compared with Western English-language media at the level of CDA and functional grammar.1

NOTE: Complete analytical data in the form of detailed tables are available from the author.

Frequency of negative, future and modal comparators in Times and China Daily texts.

Frequency of comparators in Times and China Daily texts: words/comparator.

Frequency of negative, future and modal comparators in the Times and China Daily (words/comparator).

Spread of negative, future and modal comparators in the Times and China Daily.

Breakdown of comparator evaluation found in Times and China Daily by direct speech, reported speech, and narrative text.

Negative evaluation found in Times article 38, and its attribution.

Negative evaluation in China Daily article 20 and its attribution.

Negative evaluation in the Times and China Daily: direct speech, reported speech, and narrative.

Future evaluation found in China Daily article 2 and its attribution.

Future evaluation in the Times and China Daily: direct speech, reported speech and narrative.

Future evaluation found in Times article 22 and its attribution.

Modal evaluation in Times article 31 and its attribution.

Modal evaluation in China Daily article 2 and its attribution.

Modal evaluation in the Times and China Daily: direct speech, reported speech, and narrative.