1. Introduction

In discourse comprehension, if all goes well, people tend to create a rich and coherent mental representation of the events described in the text. Halliday and Hasan (Reference Halliday and Hasan1976) claim that most people have the natural ability to determine whether a succession of sentences is a coherent text or an accidental collection of unconnected pieces. Anaphoric associations, the use of a word or a phrase to refer to previously mentioned antecedents in the text, and semantic relations, the logical or rhetorical connections between adjacent textual segments, are two crucial phenomena in the process of constructing a mental coherent representation of the text being read. Pronominal co-referential pointers and discourse connectives are linguistic devices whose function is to guide the building of this representation, thus helping the comprehender to invest less cognitive resources in reading tasks.

As is well known, referential and relational coherence relations have been explored profoundly (Brown-Schmidt, Byron, & Tanenhaus, Reference Brown-Schmidt, Byron and Tanenhaus2005; Cornish, Reference Cornish1999; Halliday & Hasan, Reference Halliday and Hasan1976; Hogeweg & de Hoop, Reference Hogeweg and de Hoop2015; Prandi, Reference Prandi2004; Reinhart, Reference Reinhart1981; Rysová & Rysová, Reference Rysová and Rysová2018; Sanders, Spooren, & Noordman, Reference Sanders, Spooren and Noordman1992, Reference Sanders, Spooren and Noordman1993; Spooren & Sanders, Reference Spooren and Sander2008; van Gompel, Reference van Gompel2013). On the one hand, third person gendered and numbered pronouns or co-referential anaphoric personal links have been studied extensively from diverse perspectives and with focus on an important number of variables (e.g., Asher, Reference Asher1993; Cornish, Reference Cornish1996, Reference Cornish2008; Ehrlich, Reference Ehrlich1980). Particular attention has been devoted to the distance of the preceding antecedent (e.g., Carpenter & Just, Reference Carpenter, Just, Just and Carpenter1977; Çokal, Sturt, & Ferreira, Reference Çokal, Sturt and Ferreira2018; Duffy & Rayner, Reference Duffy and Rayner1990; Ehrlich & Rayner, Reference Ehrlich and Rayner1983; Fukumura & van Gompel, Reference Fukumura and van Gompel2012), and to the gender and syntactic ambiguity that may arise in some contexts (Kennison, Reference Kennison2003; Kennison, Fernandez, & Bowers, Reference Kennison, Fernandez and Bowers2009; Kennison & Trofe, Reference Kennison and Trofe2003; Sturt, Reference Sturt2003, Reference Sturt and van Gompel2013). At the same time, causal and counter-argumentative semantic inter-sentential relations have also been studied intensely from different theoretical perspectives and with differing methodological techniques (Köhne & Demberg, Reference Köhne and Demberg2013; Morera, León, Escudero, & de Vega, Reference Morera, León, Escudero and de Vega2017; Parodi, Julio, & Recio, Reference Parodi, Julio, Nadal, Burdiles and Cruz2018; Prandi, Reference Prandi2004; Recio, Nadal, & Loureda, Reference Recio, Nadal, Loureda, Pons and Loureda2018; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Spooren and Noordman1992, Reference Sanders, Spooren and Noordman1993; Xu, Chen, Panther, & Wu, Reference Xu, Chen, Panther and Wu2018; Zunino, Reference Zunino2017). Yet, rarely do studies center on them together focusing on the binary procedural instruction they provide to the reader (referential and relational), particularly from a distinctive discourse-oriented approach and with eye-tracking techniques (e.g., Ackerman, Reference Ackerman1986; Çokal et al., Reference Çokal, Sturt and Ferreira2018; Koornneef & Sanders, Reference Koornneef and Sanders2013).

Complementarily, in a previous pioneering study, Parodi, Julio, Nadal, Burdiles, and Cruz (Reference Parodi, Julio, Nadal, Burdiles and Cruz2018) demonstrated that the variation of the extension of the preceding referent exerted an influence on the on-line processing of causally related texts written in Spanish, specifically on anaphora resolution of the neuter Spanish pronoun ello (‘extension effect’). In this preliminary eye-tracking research, we observed longer processing times in three reading measures, when the antecedent of the neuter pronoun ello was composed of two causal clauses, compared to a shorter referent comprising only one clause. Furthermore, recent corpus-based studies on disciplinary written genres in Spanish have reported that the neuter pronoun ello occurs as an encapsulator in a much higher proportion in the two selected semantic relations (counter-argumentative and causal) than in others such as temporal or additive (Parodi & Burdiles, Reference Parodi and Burdiles2016, Reference Parodi and Burdiles2019).

Based on previous research, we were interested in studying how different semantic relations may affect the processing of neuter anaphoric encapsulation of varying antecedent extensions. This follow-up study aims to explore the existence of an interaction effect between these two factors: (a) the extension of the referent (short and long antecedent), and (b) the type of semantic relation (counter-argumentative a pesar de, and causal por), when processing the neuter pronoun ello in texts written in Spanish. Our interest in counter-argumentative relations is based on the fact that they introduce a conclusion contrary to the readers’ expectations that could have been inferred from a previous argument (Rudolf, Reference Rudolph1996). While causality fulfills the natural anticipation of human cognition (Sanders, Reference Sanders, Aurnague, Bras, Le Draoulec and Vieu2005), counter-argumentation cancels out these expectations; therefore, these two semantic relations are expected to be processed differently and to impact inversely in their cognitive demands. In direct connection, encapsulation executed by a neuter pronoun ello is a recurrent text cohesion and coherence resource, but it is not known how variation of its extension in different semantic contexts may impact on working memory and on the construction of a situational model (van Dijk & Kintsch, Reference van Dijk and Kintsch1983).

In the following, we will first discuss previous research on causal and counter-argumentative semantic relations (marked by por ello, and a pesar de ello), and then connect this framework to discourse encapsulation processes executed by the neuter pronoun ello. In the Section 2, the method is described, focusing on the experimental design, the materials, and the participants. Section 3 presents the results. Finally, we discuss the findings and present conclusions, highlighting some projections for future research.

1.1. causality and counter-argumentation: por ello ‘as a result of this’ and a pesar de ello ‘in spite of this’

Languages foster discourse units with a fundamentally procedural meaning that makes explicit the argumentative orientation between two text segments, so that they act as guides in the deduction of implications, restricting the possible contexts to which the reader should have access (Blakemore, Reference Blakemore1987; Halliday & Hasan, Reference Halliday and Hasan1976; Loureda & Acín Reference Loureda and Acín2010; Portolés, Reference Portolés2001; Wilson & Sperber, Reference Wilson and Sperber2012). These are invariable linguistic units, which do not exercise a syntactic function in sentence predication, but which guide, according to their various morphosyntactic, semantic, and pragmatic features, the inferences drawn in communication (Cornish, Reference Cornish2008; Graesser, Singer, & Trabasso, Reference Graesser, Singer and Trabasso1994; Martín Zorraquino, & Portolés, Reference Martín Zorraquino, Portolés, Bosque and Demonte1999; McNamara, Kintsch, Songer, & Kintsch, Reference McNamara, Kintsch, Songer and Kintsch1996; Parodi, Reference Parodi2014).

This procedural function is carried out by connective units, such as por ello ‘as a result of this’, which links two co-oriented segments in a cause–consequence relation (1a), and a pesar de ello ‘in spite of this’, which marks a counter-argumentative relation (1b) (Domínguez García, Reference Domínguez García2007):

- (1)

(a) Marta y David practican muchos deportes. Por ello están sanos.

‘Marta and David play a lot of sports. As a result of this, they are healthy.’

(b) Marta y David practican pocos deportes. A pesar de ello están sanos.

‘Marta and David play few sports. In spite of this, they’re healthy.’

The connective expressions por ello and a pesar de ello are units made up of a prepositional phrase in which the preposition por and the prepositional conjunction a pesar de are combined with the neuter pronoun ello in order to establish a referential and relational connection with a previous segment and give rise to a process of cohesion and coherence (Domínguez García, Reference Domínguez García2007; Fuentes, Reference Fuentes2009; Martín Zorraquino & Portolés, Reference Martín Zorraquino, Portolés, Bosque and Demonte1999; Montolío, Reference Montolío2001; Portolés, Reference Portolés2001; Recio et al., Reference Recio, Nadal, Loureda, Pons and Loureda2018; Santos Río, Reference Santos Río2003).

In (1a) a co-oriented argumentative relationship is established between the two discourse segments; in (1b), however, the incoherence of arguments would result from the combination of two anti-oriented arguments (Portolés, Reference Portolés2001). The presence of a linguistic expression would be necessary as an explicit mark of counter-argumentation (e.g., a pesar de ello ‘in spite of this’), since it produces a disruption of the causal chain and a denial of expectations in the discourse (Blakemore Reference Blakemore1989; Nadal, Cruz, Recio, & Loureda, Reference Nadal, Cruz, Recio and Loureda2016; Rudolph, Reference Rudolph1996).

Thus, based on the continuity hypothesis (Murray, Reference Murray1997), it has been experimentally demonstrated that causality is a more predictable relation in discourse, unlike counter-argumentation (Brehm-Jurish, Reference Brehm-Jurish2005; Drenhaus, Demberg, Köhne, & Delogu, Reference Drenhaus, Demberg, Köhne and Delogu2014; Köhne & Demberg, Reference Köhne and Demberg2013; Spooren & Sanders, Reference Spooren and Sander2008; Zunino, Reference Zunino2014, Reference Zunino2016). Causality is inferable by default (‘causality by default hypothesis’) in the absence of a connective unit that makes explicit the discourse relationship between two segments:

… because readers aim at building the most informative representation, they start out assuming the relation between two consecutive sentences is a causal relation (given certain characteristics of two discourse segments). Subsequently, causally related information will be processed faster, because the reader will only arrive at an additive relation if no causal relation can be established. (Sanders, Reference Sanders, Aurnague, Bras, Le Draoulec and Vieu2005, p. 109)

1.2. encapsulation processes: neuter pronoun ello ‘it, this’

Encapsulation is a mechanism of reference and substitution carried out by a linguistic form that contributes to the thematic progression of the text and its referential maintenance, through the condensation or labelling of the meaning of discourse segments, which may precede or follow the encapsulator (Ariel, Reference Ariel1988, Reference Ariel1991; Francis, Reference Francis1986; Halliday & Hasan, Reference Halliday and Hasan1976; Montolío, Reference Montolío2013, Reference Montolío and Montolío2014; Parodi & Burdiles, Reference Parodi and Burdiles2016, Reference Parodi and Burdiles2019; Schmid, Reference Schmid2000; Sinclair, Reference Sinclair, Sinclair, Hoey and Fox1993, Reference Sinclair and Coulthard1994; Tadros, Reference Tadros and Coulthard1994). This connecting mechanism is executed by a variety of linguistic forms, which – interestingly – cannot be categorized as a class of words per se (González-Ruiz, Reference González-Ruiz, Penas and González2009; Llamas, Reference Llamas2010; López Samaniego, Reference López Samaniego2011; López Samaniego & Taranilla, Reference López Samaniego, Taranilla and Montolío2014).

As ello belongs to "a grammatical class of words that designate certain abstract notions" (RAE & ASALE, 2010, p. 24) and has no conceptual meaning, it would have greater interpretative dependency on the preceding clause(s), since it refers to “what has just been said” (Zulaica, Reference Zulaica2009, p. 59). From a psycholinguistic perspective, the neuter pronoun provides a procedural meaning (Cornish, Reference Cornish1999, Reference Cornish2008; Escandell & Leonetti, Reference Escandell, Leonetti, Oliver, Corrales, Izquierdo, García, Corbella, Gómez, Martínez and Cortés2000, Reference Escandell, Leonetti, Escandell and Leonetti2011; López Samaniego, Reference López Samaniego2011; Portolés, Reference Portolés2004; Prandi, Reference Prandi2004) that restricts, although to a lesser extent than in the nominal anaphora, the possible interpretations of the text segments in which it appears and that it relates. The procedural meaning of ello can help connect the necessary contextual information to reach the relevant interpretation of discourse. Therefore, in order to guide the reader, it constrains the inferential processes in communication (Blakemore, Reference Blakemore1987, Reference Blakemore1992, Reference Blakemore1997; Carston, Reference Carston2002, Reference Carston, Horn and Ward2004; Murillo, Reference Murillo, Loureda and Acín2010; Portolés, Reference Portolés2001; Sperber & Wilson, Reference Sperber and Wilson1995). For this reason, this neuter pronoun is one of the encapsulating mechanisms that writers can employ when recovering, in a condensed form, a large propositional content (López Samaniego, Reference López Samaniego2011).

The pronoun ello may have as antecedent sentences, pronouns, or neuter nominal groups, and even several nouns that name things, considered together (Fernández, Reference Fernández, Bosque and Demonte1999; RAE, 2005). In addition to sentences, it admits as antecedents “abstract, often deverbal, names that are interpreted as events or refer to situations or states of things that are usually represented by sentences” (RAE & ASALE, 2010, p. 303). This means that the endophoric reference (Ersan & Akman, Reference Ersan and Akman1994; RAE & ASALE, 2009) can be expressed in text units of different extension, such as noun phrases, clauses or clause complexes, text portions, or even inter-paraphrastic text segments (Borreguero, Reference Borreguero2006; Figueras, Reference Figueras2002; González-Ruiz, Reference González-Ruiz, Penas and González2009; Llamas, Reference Llamas2010; López Samaniego, Reference López Samaniego2011; Montolío, Reference Montolío2013, Reference Montolío and Montolío2014). Parodi and Burdiles (Reference Parodi and Burdiles2016, Reference Parodi and Burdiles2019) have described, from corpus studies of Economics discourse in Spanish, that neuter pronouns encapsulate – mainly in an anaphoric orientation – extensive text antecedents.

According to the above, ello, as an encapsulator, by synthesizing preceding text information, contributes to the cohesive construction of texts; it also contributes to coherence in that it guarantees the construction of consistent representational relationships in the reader’s mind (Louwerse, Reference Louwerse2004). In this regard, it plays an important role at the cognitive level (Ariel, Reference Ariel1988, Reference Ariel1991, Reference Ariel1999; Borreguero, Reference Borreguero2006; Figueras, Reference Figueras2002; López Samaniego, Reference López Samaniego2011), since it guides comprehension by converting what is encapsulated into shared knowledge available to the reader (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair, Sinclair, Hoey and Fox1993, Reference Sinclair and Coulthard1994).

The following examples display part of the problem we are interested in:

- (2)

(a) Los incendios forestales aumentaron en las últimas dos décadas. Por ello la producción maderera experimentó una severa reducción.

‘Forest fires have increased in the last two decades. As a result of this, wood production fell sharply.’

(b) Los incendios forestales aumentaron en las últimas dos décadas. La tasa de lluvias ha disminuido casi por completo. Por ello la producción maderera experimentó una severa reducción.

‘Forest fires have increased in the last two decades. Rainfall rates have almost completely diminished. As a result of this, wood production fell sharply.’

In (2a) there is a short antecedent of ello (one causal clause, e.g., Los incendios forestales aumentaron en las últimas dos décadas), but in (2b) there is, by contrast, a long antecedent (two causal clauses, e.g., Los incendios forestales aumentaron en las últimas dos décadas + La tasa de lluvias ha disminuido casi por completo). In these two examples the reader faces the challenge of causally connecting the neuter pronoun ello to a short previous antecedent (2a), or, in the second case, to a longer and more complex one. In both examples, there is – at the same time – a double marked instruction to the reader, one of referential status (ello) and the other of relational (por). This is the focus of the current study: the binary procedural instruction (relational and referential coherence) contained in two phrasal connectives: a pesar de ello and por ello.

In sum, the general hypothesis that guides this study is that the construction of a cognitive representation based partially on the resolution of a neuter pronoun with an antecedent of a long extension and the establishment of a counter-argumentative semantic relation would demand higher processing cognitive efforts to the reader. These two concurrent growing demands on cognitive processing are due to the increased working memory load (long antecedent) and the denial of expectations (counter-argumentation). This paper thereby aims to move forward the complementary study of both semantic relations and neuter encapsulation processes, as such specificity is crucial for understanding how the mind and brain construct –in connection – referential and relational discourse coherence.

2. Method

2.1. experimental design

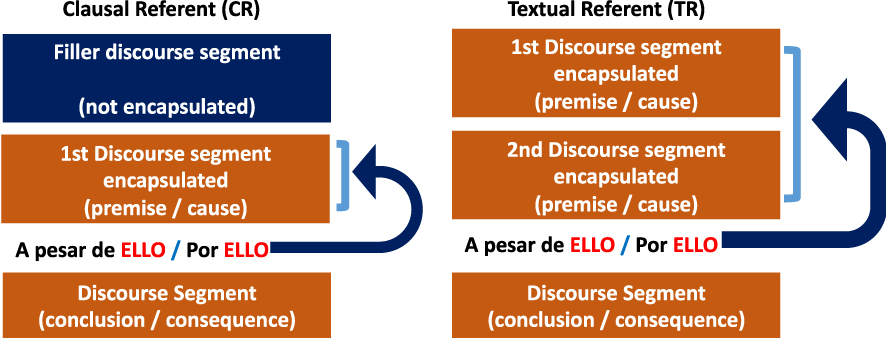

The current study aims to explore the existence of an interaction effect between the extension of the referent (short and long) and the semantic relation (counter-argumentative and causal) on the processing of a neuter pronoun ello in written texts in Spanish. The intra-subject factors are represented by the extension of the referent, which has two levels: short (Clausal Referent) and long (Textual Referent); and by the semantic relation, which also has two levels: counter-argumentative and causal.

In order to carry out the objective, a two-factor within-subjects design was implemented, which included four experimental conditions (see Table 1). The Clausal Referent (CR) is composed of one independent clause or one independent discourse segment that is encapsulated by the neuter pronoun ello. This may also be referred to as the ‘short antecedent’ in the context of a counter-argumentative (a pesar de) or a causal semantic relation (por).

table 1. Four experimental conditions

The Areas of Interest (AOIs) were segmented manually using Data Viewer software (SR-Research). They correspond to the Preceding Text-Portion (PTP) and to the encapsulator ello in both semantic relations. Figure 1 shows an example of the two critical areas (CR and encapsulator ello in a counter-argumentative semantic relation), and Figure 2 shows an example of a long antecedent (TR) in a cause–consequence semantic relation.

Fig. 1. AOIs in a counter-argumentative relation and clausal referent.

Fig. 2. AOIs in a causal relation and textual referent.

The Textual Referent (long version) is composed of two independent clauses or two independent discourse segments that are encapsulated by the neuter pronoun ello. This may also be referred as the ‘long antecedent’ in the context of a counter-argumentative (a pesar de) or a causal semantic relation (por) (see Figure 2).

In order to balance the presentation of the critical texts, the CR is introduced by a previous independent clause that is not part of the encapsulated antecedent required by the neuter pronoun ello. This independent clause is not a potential preceding premise or cause to integrate the counter-argumentative or causal construction. The first clause in the CR condition is a filler discourse segment with no semantic implication in the text (see Figure 1). This addition to the CR provides the reader the same previous co-text to the pronoun ello as in the TR condition (in quantitative terms); that is, two potential candidates for consideration as disambiguating antecedents of the anaphoric pronoun and two discourse segments. Nevertheless, only the second clause in the CR condition is required to establish referential and relational coherence. Figure 3 shows a diagrammatic description of these interactions (four experimental conditions).

Fig. 3. Diagram of the two factors (referential and relational coherence) and the four experimental conditions.

In the long condition, the two previous clauses or discourse segments are required to establish anaphoric referential coherence, and both segments are encapsulated by the neuter pronoun ello. As mentioned previously, these preceding text-portions (short and long) differ in terms of the number of clause segments that are encapsulated by the anaphoric neuter pronoun ello but are tied by two possible different discourse connectives that reinforce a counter-argumentative or a causal connection between the two main discourse segments.

2.2. materials

The target texts focus on general knowledge topics. The experimental conditions were counterbalanced (Latin-square) in order to avoid carry-over and order-learning effects, and to prevent the participants from developing specific reading strategies (Duchowski, Reference Duchowski2007; Seltman, Reference Seltman2015). A set of 32 critical items were created for the experiment, which were distributed in four experimental lists. All participants read two sets of critical items in all conditions (i.e., CR-counter, CR-causal, TR-counter, TR-causal) in different topics. Therefore, all participants read a total of eight critical items. Filler items were added to the critical stimuli in a 2:1 ratio. The texts were presented using Experiment Builder (SR Research). An example of a set of critical items, arranged to represent all conditions, is presented in Table 2.

table 2. Example of a critical item in the four experimental conditions

2.3. participants

The sample of participants in the study was composed of 72 second- or third-year university students attending a private university in Chile (43 females, 29 males, mean age = 20.04, SD = 1.7). All participants were native speakers of Spanish. They were all naive participants, which means that they were unaware of the specific purpose of the study, and none was a specialist in the field of linguistics (Keating & Jegerski, Reference Keating and Jegerski2014). All university students taking part in the experiment gave their written consent to participating in the experiment, as required by the National Commission of Scientific Research and Technology of Chile (CONICYT). None of the participants presented vision disorders that could interfere with the eye-tracker recordings.

The a priori sample size estimation considered the following parameters: (a) significance level α = .05; (b) (1-β) = 0.8; and (c) effect size f = .128. As a result, the minimum required sample size was seventy-two participants. All analyses were conducted using GPower 3.0 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007).

2.4. apparatus

Eye-movements were collected by the Eye-Link 2 Eye Tracker (SR Research, Toronto, Canada). The eye-tracker is a head-mounted infrared video-based tracking system. Eye-Link 2 consists of three miniature cameras mounted on a headband: two cameras for each eye and an optical head-tracking camera that is integrated into the headband. The third camera allows an accurate tracking of the participant’s point of gaze. The Eye Tracker captures gaze data at 500 Hz. Registration can be done either monocularly or binocularly. We performed it for the selected or dominant eye (usually the right eye) by placing the camera and the two infrared lights 4 to 6cm away from the eye. The accuracy of the system is less than 0.5 degrees in optimal conditions.

2.5. dependent variables

Three eye-movement numerical measures were computed as dependent variables:

1. Fixation Time (Holmqvist, Nystrom, Andersson, Dewhurst, Jarodzka, & van de Weijer, Reference Holmqvist, Nystrom, Andersson, Dewhurst, Jarodzka and van de Weijer2011; Hyönä, Lorch & Rinck, Reference Hyönä, Lorch, Rinck, Hyönä, Radach and Deubel2003; Rayner, Reference Rayner2009);

2. Look Back time (Hyönä, Lorch, & Kaakinen, Reference Hyönä, Lorch and Kaakinen2002; Mikkilä-Erdmann, Penttinen, Anto, & Olkinuora, Reference Mikkila-Erdmann, Penttinen, Anto, Olkinuora, Ifenthaler, Pirnay-Dummer and Spector2008); and

3. Look From time (Hyönä et al., Reference Hyönä, Lorch and Kaakinen2002; Hyönä et al., Reference Hyönä, Lorch, Rinck, Hyönä, Radach and Deubel2003; Mikkilä-Erdmann et al., Reference Mikkila-Erdmann, Penttinen, Anto, Olkinuora, Ifenthaler, Pirnay-Dummer and Spector2008).

Fixation Time (also Total Reading Time or Fixation Duration) amounts to the total time spent on an AOI, including rereading the same AOI or all reinspections of the critical region (Hyönä et al., Reference Hyönä, Lorch, Rinck, Hyönä, Radach and Deubel2003; Rayner, Chace, Slattery, & Ashby, Reference Rayner, Chace, Slattery and Ashby2006). Look Back time was obtained by summing the time of all the fixations on an AOI subsequent to its first reading (Hyönä et al., Reference Hyönä, Lorch and Kaakinen2002; Mikkilä-Erdmann et al., Reference Mikkila-Erdmann, Penttinen, Anto, Olkinuora, Ifenthaler, Pirnay-Dummer and Spector2008). In some studies, this measure is also called Second pass reading time (Hyönä et al., Reference Hyönä, Lorch and Kaakinen2002). Look From time was obtained by summing all the durations of the refixations that landed on a preceding AOI (in this study PTP AOI), having a specific AOI as the origin (in this study, from Ello AOI) (Ariasi & Mason, Reference Ariasi and Mason2014; Hyönä et al., Reference Hyönä, Lorch and Kaakinen2002; Mikkilä-Erdmann et al., Reference Mikkila-Erdmann, Penttinen, Anto, Olkinuora, Ifenthaler, Pirnay-Dummer and Spector2008).

These measures were selected for their reliable performance as reading indicators of inter-sentential processing and discourse segments integration (Holmqvist et al., Reference Holmqvist, Nystrom, Andersson, Dewhurst, Jarodzka and van de Weijer2011; Hyönä et al., Reference Hyönä, Lorch and Kaakinen2002; Hyönä et al., Reference Hyönä, Lorch, Rinck, Hyönä, Radach and Deubel2003; Mikkilä-Erdmann et al., Reference Mikkila-Erdmann, Penttinen, Anto, Olkinuora, Ifenthaler, Pirnay-Dummer and Spector2008); furthermore, they may help detect difficulties in the reading process. According to Mikkilä-Erdmann et al. (Reference Mikkila-Erdmann, Penttinen, Anto, Olkinuora, Ifenthaler, Pirnay-Dummer and Spector2008), regressions in text processing might occur when the reader rereads a target discourse segment that causes cognitive problems and has content that needs to be elucidated (look backs). Moreover, when the reader departs from a text segment to read previous text again, there is always a starting point for this regressive movements (look froms).

2.6. procedure

Participants read the texts at their own pace while their eye-movements were recorded. They were seated in a chair facing a computer monitor in a quiet room, at a distance of approximately 70cm from the monitor. To calibrate the head position, a chin rest was used to minimize head movements. An initial calibration pattern was displayed on the computer screen. To avoid miscalibration, a drift correction was performed between each critical stimulus.

Participants were told that they would be shown a series of texts while their eye position was recorded. They were instructed to read silently at a normal pace and to answer a comprehension test at the end of the experiment. After reading the instructions at their own speed, participants moved to the next screen by pressing a key on the keyboard. In order to adjust participants to the eye-tracking equipment and to present the general instructions of the experiment, a short practice trial preceded the recording of the target series of texts. Participants were allowed to start whenever they were ready. The total length of the experimental session was approximately 20–25 minutes.

2.7. clausal vs. textual referents: comparison in both semantic relations in the PTP AOI

To ensure comparisons and due to a possible source of variability in the Preceding Text-Portion (clausal vs. textual antecedents: see Figure 3), statistical analyses were conducted regarding the Total Reading Time. On the one hand, a comparison was implemented between the Filler Discourse Segment and the Premise / Causal Discourse Segment on the short condition. A second comparison was performed between the Premise / Causal Discourse Segment 1 and Premise / Causal Discourse Segment 2 on the long condition. For both comparisons, we conducted paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed ranks tests respectively on Fixation Time in both semantic relations (counter-argumentative and causal).

Results on the short condition showed that Fixation Times were greater on the Premise / Causal Discourse Segment (encapsulated antecedent) than in the Filler Discourse Segment. All differences were statistically significant in both semantic relations (see ‘Appendix 1’). For the long condition, the Premise / Causal Discourse Segment 1 and the Premise / Causal Discourse Segment 2 were also compared on the Fixation Time. No statistically significant differences were observed in both semantic relations (see ‘Appendix 2’). Based on these results, it can be concluded that the Preceding Text-Portion AOI is comparable across all conditions.

2.8. data analysis

To achieve the objective of the study, main effects and interaction analyses were performed for RE (referent extension) and SR (semantic relation) factors. We used mixed-effects models for the three measures on the Ello AOI and the PTP AOI because they offer the opportunity of including “subjects and items as crossed, independent, random effects, as opposed to hierarchical or multilevel models in which random effects are assumed to be nested” (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, Reference Baayen, Davidson and Bates2008, p. 391). Hence, linear mixed-effects models are more appropriate for analyzing eye-tracking linguistic data with several observations by participants than other tests such as ANOVA. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (R Development Core Team, 2008) and lme4 library (Bates, Maechler, & Bolker, Reference Bates, Maechler and Bolker2011; Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2014).

Before the statistical analyses were conducted, all extreme values and outliers were excluded if: (a) the mean per word was < 80 ms in the first-pass reading time and the Look Back was also < 80 ms; for any AOI; and (b) the mean per word was > 800 ms in the total reading time (Pickering, Traxler, & Crocker, Reference Pickering, Traxler and Crocker2000; Reichle, Rayner, & Pollatsek, Reference Reichle, Rayner and Pollatsek2003). All values were corrected using the Holm–Bonferroni method to reduce the possibility of getting erroneous results (i.e., Type I error) (Holm, Reference Holm1979). Of the total observations, 1,086 were considered extreme values (10.8% / 15), most of which were due to technical problems related to the eye-tracking software.

3 Results

In the following section, first, the descriptive of Fixation Time, Look Back, and Look From are presented. Second, the results of the statistical analyses, considering the main effects and the interaction effects, are reported.

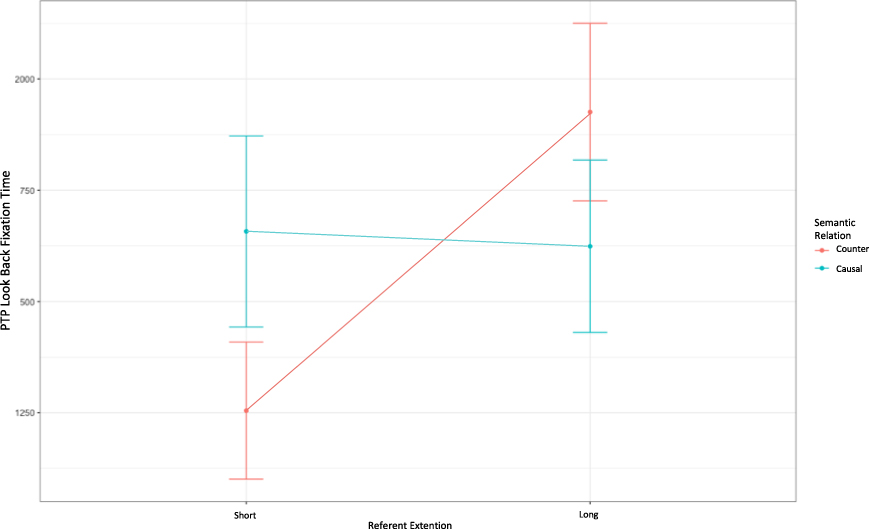

Table 3 reports the descriptives for Fixation Time, Look Back, and Look From for all experimental conditions on the Ello and PTP AOIs. Neither main effects nor interaction effects were found for Fixation Time and Look From on the Ello AOI and on the PTP AOI. On the other hand, as expected, the linear mixed-effects model revealed an interaction effect between the referent extension and the semantic relation in the Look Back measure (Estimate = –704.8, SE = 283, t value = -2.49, p = .014) on the PTP Segment AOI (Table 4).

table 3. Descriptive statistics for Fixation Time, Look Back, and Look From in the Ello and PTP AOIs for all conditions

table 4. Results of linear mixed effects model predicting Look Back to PTP AOIs

notes: *p < .05, **p < .01, *** p < .001.

The observed differences between TR and CR on Look Back were remarkably critical when the semantic relation was counter-argumentative. However, for the causal semantic relation, no differences were observed between TR and CR conditions on the Look Back measure (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Descriptive plot of the interaction between the referent extension and the semantic relation.

4. Discussion and conclusion

As we stated at the beginning of this paper, we intended to contribute to widening the present-day panorama concerning referential and relational coherence relations, particularly focusing on the interaction of the extension of the referent encapsulated by the neuter pronoun ello (short and long antecedent) and two semantic relations (counter-argumentative a pesar de, and causal por). The eye-tracking evidence provided by on-line reading points to the fact that readers devote their time and effort to constructing a mental representation that integrates the text information as one coherent discourse (Halliday & Hasan, Reference Halliday and Hasan1976), and that they are not reading it as a random collection of unrelated pieces. Less expectable semantic marked relations (e.g., counter-argumentative) in the context of complex encapsulated antecedents required a longer time to be processed (Look Back).

Consistent with our own previous study (Parodi et al., Reference Parodi, Julio, Nadal, Burdiles and Cruz2018a), and also with the specialized literature (Escandell & Leonetti, Reference Escandell, Leonetti, Escandell and Leonetti2011; Loureda, Cruz, Rudka, Nadal, Recio, & Borreguero, Reference Loureda, Cruz, Rudka, Nadal, Recio and Borreguero2015; Wilson & Carston, Reference Wilson, Carston and Burton-Roberts2007), we did not find statistically significant differences in the Fixation Time on the Ello AOI regarding the referent extension, that is, between the short discourse segment (CR) and the long discourse segment (TR) conditions. This means that, regardless of whether the antecedent is short or long, the neuter pronoun ello remains rather stable in the time devoted to its processing, despite the kind of semantic relation involved. This finding suggests that comprehenders dedicated almost the same time to the on-line reading of the neuter pronoun, not being affected either by the referent extension or by the semantic relation. It is probable that there are differences in the reading times of the CR and TR conditions that comprise conceptual meaning (premise or causal discourse segment), as opposed to a neuter particle devoid of lexical meaning (Cornish, Reference Cornish2008; Langacker, Reference Langacker2008; Zulaica & Gutiérrez, Reference Zulaica and Gutiérrez2009). Evidence from eye-tracking during reading supports the stable moment-to-moment reading of instructional particles, compared to conceptual or lexical units (Parodi et al., Reference Parodi, Julio, Nadal, Burdiles and Cruz2018a, Reference Parodi, Julio and Recio2018b; Recio et al., Reference Recio, Nadal, Loureda, Pons and Loureda2018).

As is well known, previous studies focusing on the distance of the anaphoric antecedent (Clark & Sengul, Reference Clark and Sengul1979; Daneman & Carpenter, Reference Daneman and Carpenter1980; Ehrlich & Rayner, Reference Ehrlich and Rayner1983) have found that the ‘antecedent search’ (Graesser, Reference Graesser1981; Rayner & Sereno, Reference Rayner, Sereno and Gernsbacher1994; Sanford & Garrod, Reference Sanford and Garrod1981) is not reflected in the pronoun itself (i.e., gendered and numbered pronouns, such as ‘she’ or ‘he’) (Langacker, Reference Langacker2008). A greater distance to the antecedent generally slows down on-line processing, but the delay is not shown by more fixations on the pronoun. The increased difficulty of the distance involved is reflected in other areas of the text being read (Ehrlich & Rayner, Reference Ehrlich and Rayner1983; Rayner, Pollasteck, Ashby, & Clifton, Reference Rayner, Pollastek, Ashby and Clifton2012). In this vein, Recio et al. (Reference Recio, Nadal, Loureda, Pons and Loureda2018) state that these types of connective units (a pesar de ello and por ello), that contain anaphoric elements, do not constitute a focus of attention during the late phase of reanalysis, unlike what happens with grammaticalized connectors of the same paradigm such as por tanto ‘therefore’ (Pons & Loureda, Reference Pons and Loureda2018). On the contrary, the effects of these phrasal connectives as procedural guides unfold over the other conceptual areas involved, for example, a counter-argumentative relation, in which this occurs towards the premise segments being encapsulated.

Focusing on the general objective of the current study, and taking into account the eye-tracking measure Look Back for the PTP AOI, a disordinal interaction between the extension of the referent and the semantic relation was observed: the long antecedent in the counter-argumentative condition reveals the highest reinspection times. This means that the extension of the antecedent appears to be particularly significant when the semantic relation is counter-argumentative. This finding provides supporting evidence to claim that the processing of long encapsulated constructions (two independent clauses) in counter-argumentative relations demands more time and cognitive effort, particularly in late and more strategic integration reading.

In this case, both relational and referential coherence are affected at the same time. This combination of demands forces the readers of the sample to make a greater cognitive effort in order to construct a coherent mental representation of the text. This is, in part, because counter-argumentation has been identified as a more complex discourse relation than, for example, causality. The connector a pesar de ello marks a relation of opposition or restrictive refutation: the second argument introduced by the connective suppresses the conclusions that could have been inferred from the first discourse member and redirects the discursive dynamics (Domínguez García, Reference Domínguez García2007). These are relations that provoke a denial of expectation (Blakemore, Reference Blakemore1989), since they force a modification of the expected causal relation by imposing an exception on what would be the usual consequence (Zunino, Abusamra, & Raiter, Reference Zunino, Abusamra and Raiter2012): “The adversative connective induces a new turn of presupposition: the mental operation is that of expecting something new though in deep interrelation with what has been said” (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph1996, p. 49). Several experimental studies (Brehm-Jurish, Reference Brehm-Jurish2005; Drenhaus et al., Reference Drenhaus, Demberg, Köhne and Delogu2014; Köhne & Demberg, Reference Köhne and Demberg2013; Zunino, Reference Zunino2016, Reference Zunino2017; Zunino et al., Reference Zunino, Abusamra and Raiter2012) have shown that a process of cancellation of inferences, such as the one that occurs in the discourse operation of counter-argumentation, leads to an increase in cognitive demands on the part of the reader, as opposed to a causal relation that allows a direct path from a premise to a conclusion and is, therefore, more expectable. As stated by Sanders (Reference Sanders, Aurnague, Bras, Le Draoulec and Vieu2005), causality is inferable by default, as is also known by the ‘causality by default hypothesis’.

Considering the results of these previous experimental studies, which reveal the difficulty of processing the counter-argumentation, it is not surprising that the greater extension of the referent interacts with this kind of semantic discourse relation. This is associated with the instructional value of the neuter ello, which enables the reader to integrate the correct antecedent into a semantic relation, thus supporting the thematic progression and encapsulation requirements. Based on this, a pesar de ello is clearly not a grammaticalized connecting unit, but a complex phrasal construction or secondary discourse connective (Rysová & Rysová, Reference Rysová and Rysová2018), whose value is constructed from two sources: one referential and one relational. In this binary complex construction, there is a double instruction to the reader, signaled concurrently by a neuter anaphoric pronoun and connective particles. The current data provide experimental evidence to the debate regarding the grammatical and pragmatic features of functional categories such as a pesar de ello and por ello (Pons & Loureda, Reference Pons and Loureda2018). The findings yielded by the Look Back eye-tracking measure confirm the referential value of the neuter pronoun ello, as the extension of the antecedent involved in a counter-argumentative relation clearly influences regression times to the encapsulated long segment.

In this vein, the findings of the present study for the Look Back are plausible: the wider the areas for the construction of the counter-argumentative assumption, the longer the reprocessing time required. The working memory demands imposed by the process of constructing referential coherence indicates to the readers that they must recover the semantic content that disambiguates the neuter pronoun in order to establish the connecting relations with the next discourse segment. This retrieval of the anaphoric content was hindered by the increased extension of the antecedent in the late processes of integration in counter-argumentation.

Experimentally, these findings fit with the existing evidence that processing counter-argumentative relations is more demanding than processing causal relations, particularly in late integrative processes. Nevertheless, compared with previous research on the same semantic relations (Köhne & Demberg, Reference Köhne and Demberg2013; Zunino, Reference Zunino2014, Reference Zunino2016, Reference Zunino2017), and with others focusing on concessive and causal ones (Morera et al., Reference Morera, León, Escudero and de Vega2017; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen, Panther and Wu2018), the current study has novel implications: the combination of two kinds of coherence, presented conjointly and marked by a phrasal connective unit containing a neuter pronoun in Spanish, revealed higher working memory and cognitive load demands.

In sum, our study has provided empirical evidence to sustain that a disordinal interaction was observed between the referent extension and the semantic relation: the long antecedent and the counter-argumentative relation in the Look Back reading measure were the discourse construction that evidenced longer reading times and exerted more cognitive effort on the sample of university readers. The counter-argumentative semantic relation emerged as more critical to the ‘extension effect’. In other words, the complexity of long encapsulation discourse constructions including a neuter pronoun turned out to be particularly intricate when the involved semantic relation was counter-argumentative. Furthermore, reading the neuter pronoun ello was not influenced by the extension of the encapsulated antecedent in any of the conditions under study (short or long).

In general terms, the current findings reconfirm our first and initial hypothesis: the greater the extension of the referent, the greater the reading times of the area that resolves or disambiguates the neuter anaphora in explicitly marked counter-argumentative relations. This tends to occur specifically in the reading stage of late integration as it is identified by the Look Back eye-tracking measure. Based on this, our findings are in agreement with the fine-grained linguistic analysis of relational coherence relations (i.e., conceptual and pragmatic) that asserts that counter-argumentative semantic relations are functionally dissociable from causal relations (e.g., counter-argumentation entails a denial of expectations and involves a restrictive refutation), and that, therefore, relative to processing causal relation, when processing a counter-argumentative one encompasses an additional cognitive process, namely the process of inference cancellation. This result is also in line with the pragmatic and psycholinguistic argument that por ello and a pesar de ello encode a double procedural instruction. On the one hand, the neuter pronoun ello conveys the need for a co-referential disambiguation or anaphoric resolution; at the same time, the particles (a pesar de and por) guide connections between the discourse segments involved in the semantic relation. This way, the two meanings or instructions (referential and relational coherence) demand that the comprehender displays at the same time cognitive resources in both directions. The current research study demonstrates that the distinctions between processing counter-argumentative and causal meanings holds for Spanish, in addition to other languages such as English, Dutch, German, and Chinese.

Our study points to the need for a further examination of the different types of constituting units or entities of the premises and causes as complex antecedents in written discourse (i.e., concrete or abstract referents; coordination or subordination of clauses) and how other kinds of semantic relations may affect the processes of disambiguating neuter anaphors across different experimental tasks. Nevertheless, a future in-depth analysis should take into account the present preliminary findings.

Future eye-tracking studies on this cutting-edge research area must explore more ecological scenarios, employing – for example – texts identified as part of disciplinary discourse genres based on corpus studies. This is unequivocally crucial for this line of investigation, in order to explore naturally occurring genres that represent actual written communication in real-life interactions. Not only will we understand in this way more about the processing of written discourse encapsulation mechanisms with varying antecedent extensions in different semantic contexts, but we will also better understand how referential and relational coherence work together in the construction of a mental representation in moment-to-moment reading. Despite these possible limitations, the current research has scientific significance as it suggests the potential of a novel approach to combining the two types of coherence conjointly (referential and relational) from a discourse-oriented perspective.

Appendices

appendix 1. Comparison between Filler DS and Encapsulated DS within both semantic relations.

appendix 2. Comparison between Encapsulated DS 01 vs. DS 02 within both semantic relations.