1. Introduction

The analysis of spontaneous speech-accompanying gesture is a privileged avenue for the cross-cultural study of temporal cognition because gestures give researchers access to mental imagery that may not be readily available in temporal language and metaphors. In most psycholinguistic or linguistic anthropological studies that examine temporal thought, participants are generally unaware that the researcher is studying the connection between their gestures and how they think about time, until they are debriefed. In fewer studies, however, participants have been asked to make or interpret explicit temporal gestures, or to tell a story whose main focus was the passage of time. This study follows suit by examining the gestures made by speakers of American English and Chol, a Western Maya language, as they tell the story of A Christmas Carol, a story that deals specifically with time. It also examines temporal conceptualization in the gestures made by a Chol speaker while telling a traditional Chol story.

While an abundance of studies has provided evidence for the widespread – but not universal – nature of mental timelines, research that examines non-linear and non-spatial conceptualizations of time is still the exception, rather than the norm. Sinha et al. (Reference Sinha, Da Silva Sinha, Zinken and Sampaio2011) have argued that space-time mappings are not a feature of the Amondawa language and culture in the Brazilian Amazon. Similarly, other authors have documented event-based conceptions of time in cultures as distant and unrelated as the Malagasy of Madagascar (Dahl, Reference Dahl1995) or the Kabyle Berbers of Algeria (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu and Pitt-Rivers1963). In an event-based conception of time, time is not conceptualized as a line that stretches from the past to the present into the future, or as movement along that line. In event-based conceptions of time, ‘time is when something happens. It is an event’ (Dahl, Reference Dahl1995, p. 202). The event-based units of time, rather than being the regular intervals characteristic of linear-oriented temporal conceptualizations, are concrete – irregular, and non-identical – events, such as ‘the sunset’, ‘a birth’, ‘a feast’, or ‘the harvest’. These kinds of events or experiences are central to Algerian peasants’ notion of time, which is discontinuous, event-based, and comprised of ‘islands of time’ (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu and Pitt-Rivers1963, p. 59), rather than of regular, measurable intervals that can be located along an abstract timeline.

Mayan languages and cultures have recently become of interest to students of temporal language and thought, and some scholars have been using gesture analysis, along with ethnographic observation, to investigate how speakers of Mayan languages conceptualize time. Similarly to the research conducted by Sinha and colleagues in the Amazon culture area, some Mayan languages and cultures have been claimed to have non-linear notions of time, as shown in their speech-accompanying gestures. Yucatec is an interesting case in point, given that researchers have observed different tendencies among speakers of this language. While Kita et al. (Reference Everett and Jaszczolt2001)argue that the temporal gestures of speakers of Yucatec seem to map time flow along a lateral axis with time flowing from right to left, Le Guen and Pool Balam (Reference Le Guen and Pool Balam2012) argue that the timelines that are so commonly observed in speakers of tensed languages are completely absent from the gestural repertoire of Yucatecan speakers. I have studied how temporal relationships between events are represented in the speech and gestures of Chol Mayans, and, like Le Guen and Pool Balam, I found no evidence of metaphorical timelines in the spontaneous gestures of Chol speakers (Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2019, Reference Rodríguez2021). In Chol and in Yucatec, the contrast between completed and non-completed events seems to be, however, an important distinction that may surface in Chol temporal gestures. While the relative positioning of one event respect to the moment of speech or respect to another event seems not to be too relevant – it is grammatically possible, but not mandatory – in some Mayan languages, whether an event is completed or non-completed appears to be central to how the speakers of these languages conceptualize time.

In this study I examine differences in gesture production in narrative contexts between American and Chol Mayan speakers at the narrative, metanarrative, and paranarrative levels of discourse. The study also examines temporal conceptualization as expressed in Chol speakers’ gestural repertoire. Chol Mayans live in the Mexican State of Chiapas and some areas of Guatemala. They are traditionally slash-and-burn agriculturalists, yet some also cultivate coffee, which provides them with supplemental income. Although many Chol depend on the staples they cultivate in their fields – mostly corn, beans, squash, and other popular vegetables in the area such as ch’ajuk (‘hierba mora’ in Spanish) ‘black nightshade’ – as their main means of subsistence, in municipal centers, this population is becoming increasingly less dependent on agriculture as a means of subsistence. In the last couple of decades, some Chol have left their towns to pursue higher education in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, or move out to a nearby state to learn a profession.

2. Elicitation of temporal gestures

Researchers use different techniques for eliciting temporal gestures, but only a few studies have monitored the gestures of participants that were asked explicitly to think and talk about time or time-related concepts. For example, Casasanto and Jasmin (Reference Casasanto and Jasmin2012) asked their study participants to make and interpret explicit temporal gestures. Cooperrider and Núñez (Reference Cooperrider and Núñez2009) had their participants tell a story whose main focus was the passage of time. They showed participants an image that portrayed the compressed story of the universe; then, participants were asked to tell the story of the universe to another participant. These studies showed some good evidence for the psychological reality of the abstract timeline as manifested in English speakers’ gestural repertoire. In their classic study of Aymara gestures, Sweetser and Núñez asked participants to tell stories, anecdotes, or sayings involving time (Núñez & Sweetser, Reference Núñez and Sweetser2006), which resulted in the elicitation of the famous speech-accompanying gestures that mapped the future in the back and the past in front – a pattern that has now also been observed in Vietnamese (Sullivan & Bui, Reference Sullivan and Bui2016). All of these studies show that asking people to think explicitly about time, or to tell stories in which the central topic is the passage of time, is a good strategy for eliciting temporal gestures and studying temporal cognition.

2.1. Method

In the first part of this study, a total of 165 co-speech gestures collected from three speakers of American English and three speakers of Chol Mayan were analyzed for this study, to determine whether significant differences existed between speakers of these two languages in the speech-accompanying gestures that would be produced during their retellings of a story about time travel. The data from speakers of American English were collected in Charlottesville, Virginia (United States), and the Chol data were collected in Chiapas (México), in the villages of Jolpokitiok and Jolñixtie, municipality of Tila. The stories collected in Virginia and Chiapas were video-recorded with the consent of the speakers.

American and Chol Mayan participants were asked to retell the story of A Christmas Carol (Dickens, Reference Dickens1843) to an interviewer. The choice of Dickens’ famous novel was motivated by the central role that time plays in this story. Time is anthropomorphized in the characters of three ghosts that haunt the protagonist, Ebenezer Scrooge, and it is also represented as three different space-time locations which Scrooge visits with the help of the three ghosts. It is thus a story about time, and about time travel. The story also had some elements – for instance, the ghosts communicating with the main character – that could be easily translated both linguistically and culturally into some kind of intelligible narrative in the Chol context.

2.2. Participants

The three American participants were undergraduate students of the University of Virginia, and monolingual speakers of American English; two were male, one was female. The three Chol participants were also monolingual, and all of them were female. Given that this study focused on monolingual speakers, in the Chol area, it is easier to find female monolingual speakers than male monolingual speakers. The older generation of Chol speakers are mostly monolingual in Chol or have some knowledge of Spanish; middle-aged adults tend to be fully bilingual in Chol and Spanish, and children are being increasingly raised monolingually in Spanish, with only some anecdotal knowledge of Chol.

2.3. Procedure

The American participants were asked if they knew the story of A Christmas Carol; they all did. Then, they were asked to tell the story of A Christmas Carol to another person. With the Chol participants, some adjustments had to be made, because, as it was expected, none of them knew the story of A Christmas Carol. Hence, they had to be told the story before they could tell it to someone else. To that end, a very simplified version of the story was translated into Chol.Footnote 1 This version of A Christmas Carol contained the full argument of the story in a nutshell, and kept the most important features and characters of the story. To make the story more understandable from the Chol perspective, we introduced a minor variation: instead of visiting Scrooge while he was awake, in our Chol version of the Christmas Carol, the ghosts visited Scrooge in dreams; this is because Chol Mayans believe that the souls of the dead ancestors can visit the living in dreams. The story contained examples of deictic time and sequential time. Deictic time was introduced in the names of the ghosts, and the past, present, and future times that the protagonist was able to relive in his dream. Sequential time was construed as a succession of events that were ordered with respect to each other: first, the man goes to sleep, then he has a dream, he sees things that occurred in his past, and then he wakes up; the same process of going to sleep, dreaming about a different time, and waking up is repeated three times.

Chol participants were first told the story by a research assistant who was bilingual in Chol and Spanish. At the beginning of the task, I would explain to the participants that my assistant was going to tell them a story, and that I would like them to retell the story to me later. Then, I would leave the room, come back when my assistant had finished telling the story, and ask the speakers to tell me what my assistant had told them. The assistant was instructed not to gesture as he was telling the story to the participant. This was a culturally sensitive procedure, since story-telling is a very common activity in the Chol cultural context; people are used to hearing stories from other people and then retelling those stories to someone else.

Both American and Chol participants would retell the story without being interrupted. However, if after having finished they had not mentioned anything about the dreams, the ghosts, or about the protagonist visiting past, present, and future times – which none of the Chol participants did – we would ask follow-up questions, such as “do you remember what the man dreamt about?” or “was the man visited by any ghosts?” and – if the answer was affirmative – we would ask them to tell us more about the ghosts.

2.4. Narrative levels and gesture coding

Each gesture performed by the American and Chol participants was coded for the following categories: (1) At what narrative level it occurred; 2) Whether it was temporal; and 3) If it was temporal, whether it was linear. The three narrative levels – narrative per se, metanarrative, and paranarrative – were determined by the content of the speech. The narrative level is the plot of a story, which “…consists of references to events from the world of the story proper. The defining characteristic of sentences at this level is that the listener takes them to be a faithful simulacrum of world occurrences in their actual order” (McNeill, Reference McNeill1992, p. 185). The metanarrative level consists of metalinguistic references to the structure of the story; it presents “the story about the story” (ibidem, p. 186). The paranarrative level consists of sentences that make a reference to the context where the story-telling is happening. For example, the speaker may abandon the role of narrator and give his or her opinion about the events in the story, make a reference to an interlocutor, or address his or her audience.

A gesture was defined as temporal when it co-occurred with clearly codable temporal language and when it depicted, represented, or enacted some aspect of the meaning of the speech with which it co-occurred, and did not fulfill any explicit metapragmatic function. Temporal gestures were coded as ‘linear’ when they were spatialized along an axis which represented the shortest possible distance between two separate points, or along which at least three collinear points could be located. This definition of ‘temporal-linear’ excluded gestures that were morphologically linear, but not semantically linear: certain kind of gestures may be morphologically linear, in the sense that the speaker may, for instance, extend her forearm from her lap pointing at something in the landscape, and the trajectory of such a gesture may be linear; or she may make a linear gesture while enacting spatial movement from a character in a story. But this kind of linear movement does not reflect a space-time mapping or a linear conception of time. A temporal gesture was considered semantically ‘linear’ when speakers would “point, trace, enact movement, place characters or objects along an implied lateral, sagittal, or vertical timeline, or connect points along such a timeline” (Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2019, p. 7).

2.5. Results

A Welch’s t-test was used to examine the differences in gesture production between American and Chol participants. The American speakers (M = 46, ST = 12.28) compared to the Chol speakers (M = 9, SD = 11.53) made significantly more gestures t(3.98) = 3.8, p = 0.019. They also made significantly more gestures at the narrative level of discourse t(2.19) = 4.62, p = 0.03. The differences were also striking with respect to temporal gestures and specifically linear temporal gestures; the American participants made significantly more temporal gestures t(2) = 22, p = 0.002 and linear gestures t(2) = 5.19, p = 0.035.

3. Temporal gestures in the American English retellings of A Christmas Carol

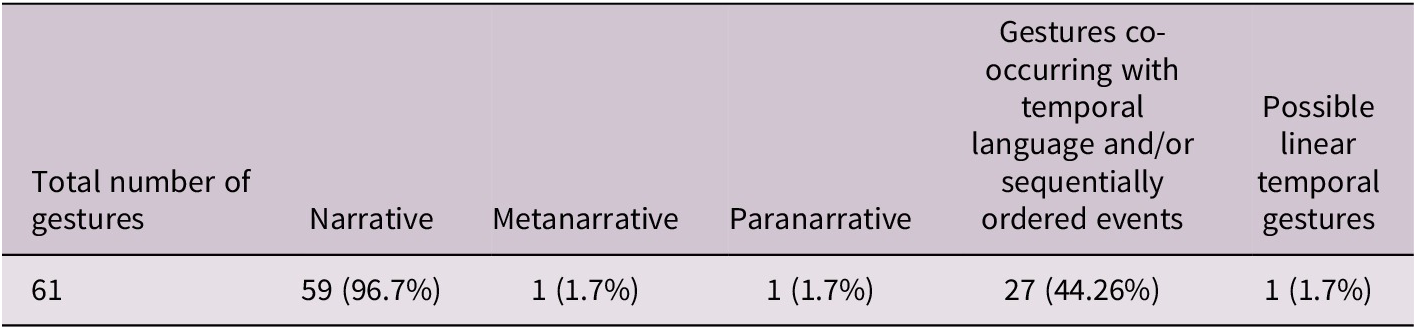

Table 1 summarizes the gestures made by American participants.

Table 1. American English speakers’ gestures

When telling the story of A Christmas Carol, the three American participants produced many gestures accompanying their speech (N = 138), and 13% of these gestures were coded as linear. Overall, most of the gestures (92%) occurred with narrative statements; gestures occurring with metanarrative (2%) and paranarrative (5%) statements were fairly uncommon. This makes sense given the fact that the American participants used very few metanarrative and paranarrative statements in their retellings. Metanarrative statements, if any, happened only at the beginning of the retelling. Occasionally, participants would step out of their role as narrators to make a brief paranarrative comment. But most of the content of the stories told by the American participants was narrative, not metanarrative or paranarrative, and hence it does not come as a surprise that most gestures and all temporal gestures were produced at the narrative level.

3.1. Metanarrative and paranarrative statements and their co-speech gestures

All American retellings begun similarly. ‘Example (1)’ shows how Participant 2 begun his story:

In the previous example, the story is introduced by the metanarrative statement “The Christmas Carol is the story of a man, a very old man named Ebenezer Scrooge…” Another participant introduced the story with another metanarrative statement: “The story is set in England”; these metanarrative statements have co-occurring metaphoric conduit gestures, where an abstract concept is represented as an object that can be held and manipulated by the speaker (McNeill, Reference McNeill1992). Conduit gestures co-occurring with these kinds of metanarrative statements represent the story being told, which is presented as an object – as if being offered for inspection – on the speaker’s palm, or held between the speaker’s hands. Below is an example from Participant 3 (Fig. 1), showing a metaphoric conduit gesture co-occurring with his first statement, “The story is set in England.” Before starting the sentence, both hands are in a relaxed position in his lap. As he says “The story is set in England,” both palms face inward and form a concave shape, as if holding an imaginary object.

Fig. 1. Metaphoric conduit, metanarrative level.

After a very brief introductory metanarrative statement, participants quickly shift to the narrative level; Occasionally, the flow of the narrative may be interrupted by a quick paranarrative comment, like the ones illustrated in ‘examples (3) and (4)’. In ‘example (3)’, for example, the participant makes a quick paranarrative statement when adding a detail about the three ghosts, which he is unsure about:

In the retelling of another participant, he makes a quick paranarrative comment as he reflects on the moral of the story:

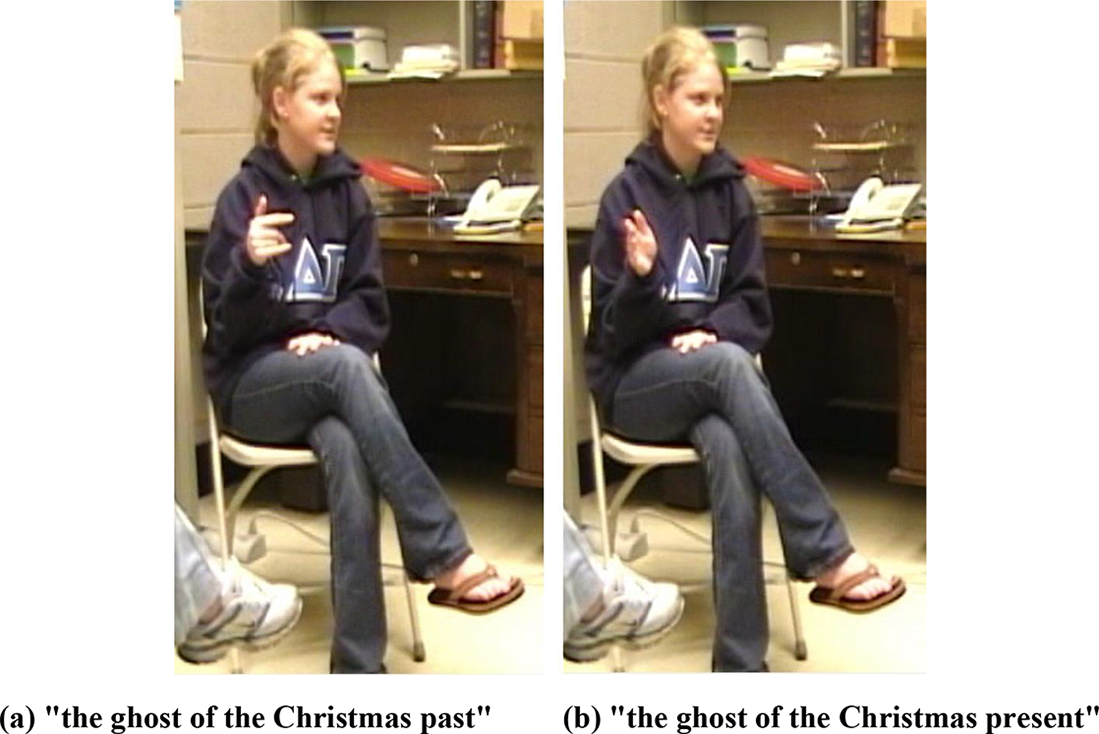

The gestures co-occurring with ‘examples (3) and (4)’ are shown in Fig. 2a,b, respectively. These gestures seem to be examples of what Cooperrider et al. (Reference Cooperrider, Abner and Goldin-Meadow2018)) have called ‘palm-up epistemic gestures’, which are “a variant of the palm-up that prototypically involves lateral separation of the hands. This gesture (…) is used in speaking communities around the world to express a recurring set of epistemic meanings” (Cooperrider et al., Reference Cooperrider, Abner and Goldin-Meadow2018, p. 1). In Fig. 2a, the epistemic palm-up gesture is performed only with the right hand, and in Fig. 2b, it is performed with both hands.

Fig. 2. Palm-up epistemic gestures co-occurring with paranarrative statements.

In the example shown in Fig. 2a, the palm-up epistemic gesture co-occurs with the epistemic statement “I guess,” which conveys the participant’s uncertainty about the information expressed in the previous statement. In ‘example (4)’ (Fig. 2b), the palm-up gesture co-occurs with “you know.” Müller has suggested that one possible meaning of these gestures is the “presentation of discursive objects, which are suggested for agreement” or “presenting arguments and inviting to share perspectives” (Müller, Reference Müller, Müller and Posner2004, pp. 252–253). The gesture shown on Fig. 2b ‘presents’ to his interlocutor the participant’s interpretation of what seems to him to be the moral of the story, that after being visited by the three ghosts he learns his lesson and turns around his life.

3.2. Gestures at the narrative level

Not surprisingly, all temporal gestures co-occurred with narrative statements. Sixteen percentage of the total number of gestures were temporal, and most of these were also linear. All these linear gestures had a lateral or transversal orientation, with time flowing from the gesturer’s left (which represents the past) to his right (which represents the future); the center of the gestural space is reserved for objects, characters, or events that are related to the present or that take place in the present. When gesturing metaphorical timelines, participants sometimes make successive strokes with a vertical palm hitting a series of points that indicate the locations of past, present, and events (Casasanto & Jasmin, Reference Casasanto and Jasmin2012; Cooperrider & Núñez, Reference Cooperrider and Núñez2009; Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2019). American English speakers may also produce deictic gestures with an extended finger that point at any of these spatialized time locations. The examples shown in Fig. 3 illustrate two morphologically different types of abstract deictic gestures: a pointing gesture with the index finger extended (Fig. 3a), and a vertical palm stroke gesture (Fig. 3b). The co-occurring speech is shown in ‘examples (5) and (6)’:

Fig. 3. Abstract deixis in lateral linear gestures.

The gestures in Fig. 3 function indexically to locate past and present along the speaker’s mental timeline. Fig. 3a illustrates how time is presented as a visible location, which can be clearly pointed at. The gesture stroke co-occurs precisely with the word ‘past’. Cooperrider and Núñez (Reference Cooperrider and Núñez2009) also reported that pointing gestures were among the most common temporal gestures when speakers were telling the story of the universe. They argue that such pointing gestures ‘often occur after a speaker has already populated the space with an imaginary timeline’ (Cooperrider & Núñez, Reference Cooperrider and Núñez2009, p. 191). After describing the events that take place in Scrooge’s past, the speaker goes on to narrate that Scrooge is taken ‘back’ to the present. In Fig. 3b, the participant hits the second point in the imaginary timeline with a vertical-palm stroke in front of her body, at the center of the gestural space. The gesture co-occurs in perfect synchrony with the word ‘present’.

The following gesture, as shown in Fig. 4, is slightly different. It is a blend of an iconic gesture – a gesture that depicts, in an image, some aspect of the utterance it accompanies – and a metaphoric space-time location. At the beginning of sentence (7), the participant has both hands resting on her lap. As she begins to say “to the future,” she lifts up her right hand, palm facing downward with her fingers extended, and moves it away from her body toward the right peripheral area of the gestural space.

Fig. 4. Iconic–metaphoric blend of character and temporal location.

Most of the gestures that this participant had produced during her retelling of the story were iconics, gestures that depict or represent in an image some aspect of the accompanying speech. Iconic gestures are, according to McNeill, the most common gesture types occurring at the narrative level (McNeill, Reference McNeill1992). These gestures often depict two different viewpoints that the speaker may adopt when telling a story: the character viewpoint, in which the speaker’s hand or body ‘enact the character’ (McNeill, Reference McNeill1992, p. 190), and the observer viewpoint, in which ‘the depiction is concentrated in the hand, the character shown as a whole hand, and the voice accordingly is that of an observer/narrator’ (ibidem). Up to this point in the narration, most of the gestures that the speaker had produced were observer-viewpoint iconics; from this ‘narrator–observer’ perspective, she would move the characters of the story, represented by her right hand in the shape of a ‘blob’, along the pre-established lateral timeline. But in the gesture shown in Fig. 4, she adopts the character-viewpoint perspective, as if her hand was literally moving an object toward her right periphery, where the future is located. Her hand becomes one of the characters, the ghost, taking Scrooge to the new spatialized time location. This type of gesture is similar to the ‘animating’ gestures described by Cooperrider and Núñez (Reference Cooperrider and Núñez2009, p. 22), or even to Müller’s ‘performing’ gestures, where ‘hands act as if they would perform an instrumental action’ (Cienki & Müller, Reference Cienki and Koenig2008, p. 22), in this case the action of grabbing someone and placing him in a different spatio-temporal location.

4. Temporal gestures in the Dickens in Chol task

4.1. The Chol retellings: Overview of content, relevant themes, and gesture occurrence

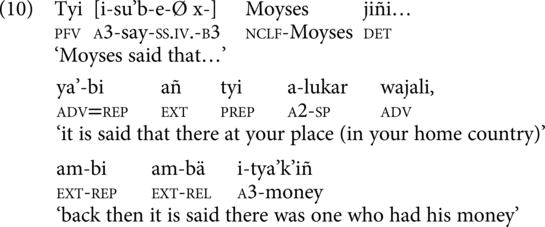

Just as the American English speakers’ retellings of the Christmas Carol were very similar among them, the Chol speakers also gave very similar versions of the Christmas Carol. Furthermore, not surprisingly, the Chol stories were very different in structure and content from the American stories. The fundamental themes in the three Chol narratives were that there was a man who had a lot of money, who did not want to share it with anyone else, and the man did not want to die alone. The theme of the man being visited by ghosts in dreams was secondary. It is no wonder that, instead of capitalizing on the protagonist’s strange ‘time travel’, the two prominent themes mentioned in the Chol stories were the stinginess of the man and his fear of dying alone, as shown in the following excerpt of one of Chol retellings:

In Chol culture, as in many other Maya and Mesoamerican cultures, being rich without redistributing part of one’s riches to the community is socially unacceptable behavior. Therefore, this is one of the elements of the story that caught the Chol speakers’ attention. The fear of dying alone is related to this theme. Chol households are typically not just comprised of a nuclear family; they are comprised of an extended family, which usually includes the elderly. Even if an elderly person may choose to live in his or her own house by himself or herself, their home is usually part of a family compound and is never far away from their children’s homes. Dying alone is something as odd and incomprehensible to a Chol person as not being married or not having children of one’s own by choice. From the Chol perspective, it makes sense that such an odd person, who keeps money for the sake of money and does not want to spend it, would be repudiated and thus condemned to living and dying alone. Instead of reproducing the linear narrative of A Christmas Carol, the Chol narratives simply emphasized those aspects that were more salient to them: the paradoxical behavior of the man who, having money, does not want to spend it, and does not want to have a family of his own, but is afraid of dying alone.

Two Chol participants briefly mentioned the dream. They did remember the details of the dream, but they remembered some isolated scenes; for instance, one of the participants said that the man dreamt about himself, that he was alone and he had no wife; he also dreamt about people who were dead. Another participant added more details, saying that the man had dreamt about the place where he grew up and how it was like when he was a child; he had also dreamt about the cemetery where he was going to be buried, and he did not want to die alone. In other words, it was the places where the protagonist would go – rather than the different times – what were mentioned by some of the Chol participants. Nonetheless, no participant said anything about the three ghosts spontaneously. When asked in a follow-up question whether they could remember anything about any ghosts in the man’s dream, two participants said that those must have been the ghosts of dead people, which again is an interpretation that makes sense in Chol culture. The Chol believe that the dead can communicate with the living through dreams. Furthermore, events and situations that happen in dreams are sometimes taken at face value, as if they had happened in one’s waking-life. Interestingly, none of the participants could remember the names of the three ghosts, not even a participant who talked about different moments in the protagonist’s life, the time when he grew up and the time when he is taken to a cemetery.

The Chol retellings for the most part lacked sequential language to refer to the three episodes of the story, even though that language was carefully included in the stimulus. They did not reflect an argument ‘line’ that followed any kind of sequential order, or where earlier/later relationships between episodes could be established; instead, the Chol participants gave descriptive ‘snapshots’ of the general themes of the story, the stinginess of the man, and his unwillingness to die alone. One of the very few examples of sequential language used by a participant, shown in ‘example (9)’, was not accompanied by a co-speech gesture.

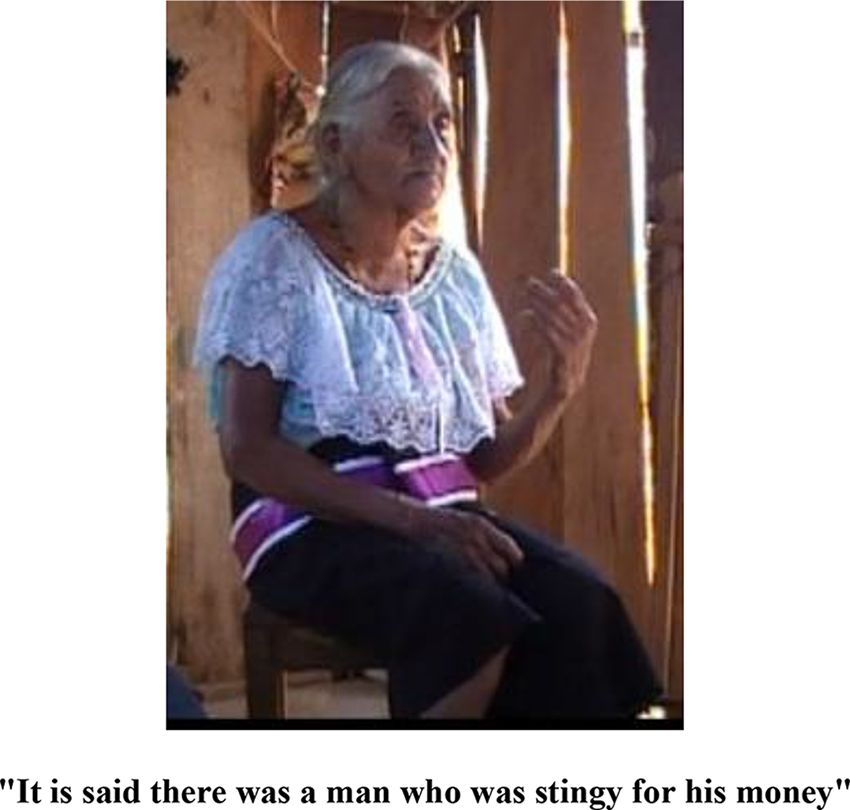

If the two themes that were crucial in the original story, the ghosts, and the concept of travelling between the different times in Scrooge’s life were conspicuously absent from the Chol narratives, how did that affect gesture production? Table 2 summarizes the distribution of gesture occurrences across the three Chol speakers’ narratives.

Table 2. Chol speakers’ gestures

In the three stories, not a single example of any kind of temporal gesture was identified, which is hardly surprising given the non-deictic, non-sequential nature of the Chol retellings. Despite the fact that the stimulus contained explicit temporal reference, in their retellings, the Chol speakers used very few temporal deictic adverbs or sequential language.

Overall, Chol speakers made few gestures, or as in the case of Participant 6, no gestures; while retelling the story, this participant kept her hands in a semi-relaxed position, holding her knees, and only making quick self-adjustments – touching her hair, or rinsing the sweat of her face with her shirt. It is worth noting that in a conversation preceding the Dickens in Chol task, this participant had been gesturing freely, and abundantly. Interestingly, this woman was in her middle twenties, so among the three Chol speakers, she was closest in age to the undergraduate students of the University of Virginia. Her story was the longest and most detailed of the three, and she was the speaker who could recall more details about the dream. In what follows, I will describe how gesture, or its absence in this case, may serve as metapragmatic commentary on the artificiality of the task at hand.

4.2. Gestures at the paranarrative, metanarrative, and narrative levels of discourse

As can be seen in Table 2, most of the gestures in the Chol stories co-occurred with paranarrative statements; few gestures co-occurred with metanarrative or narrative statements. Fig. 5 shows the typical arrangement for the ‘Dickens in Chol’ experiment: Moysés Vázquez, a research assistant, sat at the participant’s right; after he had finished telling the story of A Christmas Carol, the researcher sat down at the participant’s left, and asked her to tell the story that Moysés had just told her. In response to this request, the Chol participants would start framing their stories with a paranarrative statement of the type “he told me that…” These paranarrative commentaries had co-occurring deictic (pointing) gestures, like the one shown in Fig. 5. In this gesture, Participant 5 points at Moysés with her right hand, with a vertical palm moving away from her body toward the right periphery area, which is closer to the person that she is pointing. The gesture was preceded by the speaker’s gaze; she looked at Moysés quickly, then opened up her right arm directing her hand toward him.

Fig. 5. Deictic gesture, paranarrative level of discourse.

Fig. 6. Deictic gesture, paranarrative level of discourse.

This is an interesting example because the sentence does contain temporal reference, the deictic temporal adverb, wajali ‘back then, long time ago, in the past’, which situates the time of the narrated story in the past, long before the moment of speech. It also contains spatial reference ‘there at your place’, which refers to the country where the researcher is from, since Moysés had introduced the story as a tale that is told in the country where the researcher is from.Footnote 4 The paranarrative introduction thus aims at situating the story both in space and time. However, neither the deictic temporal adverb wajali ‘back then’, nor the adverbial (spatial) subordinate clause ya’bi añ tyi alukar ‘there at your place’ had an accompanying gesture; with a vertical palm, the speaker pointed at the bilingual assistant, Moysés, as if showing who was ‘the source’ of the story was more relevant than ‘when’ and ‘where’ the story took place.

It is not surprising finding deictic gestures such as the one illustrated in Fig. 5 co-occurring with paranarrative statements. McNeill has argued that the gestures occurring in narrative contexts are usually adapted to the pragmatic functions of each discourse level:

Iconics appear at the narrative level, where the content consists of emplotted story events; iconic gestures exhibit these events. Metaphorics appear at the metanarrative level, where the content consists of the story structure itself viewed as an object or space; metaphoric gestures present the story as an object or an arrangement in space. Pointing appears at all levels when orientation or change of orientation is the focal content… Finally, beats appear when there are rapid shifts of level (McNeill, Reference McNeill1992, p. 189).

In the Chol retellings, however, the iconic gestures, which according to McNeill typically appear at the narrative level, were almost nonexistent. The following excerpt from ‘example (8)’ and Figs. 6–8 illustrate the gestures typically found at each narrative level:

Fig. 7. Beats, metanarrative and narrative levels of discourse.

Fig. 8. Palm-up presentational gesture, narrative level of discourse.

The retelling begins with the paranarrative statement “he told me that”; as she is uttering that sentence, the participant turns her body slightly toward her right, where the assistant is sitting, and points at him with a vertical palm of her right hand (Fig. 6). This gesture is almost identical to the one shown in Fig. 5.

After this brief paranarrative statement, the participant readjusts her position and faces the researcher. The next two clauses are in an intermediate position between the paranarrative and narrative levels of discourse; semantically, they refer to the events of the story proper, so in this sense, they belong to the narrative level; however, the reportative particle -bi adds a certain narrative distance; it fulfills the metalinguistic function of indicating that what is being said is hearsay. For this reason, it is difficult to classify the utterances that contain this particle into the strictly metanarrative or narrative categories. In this particular example, it seems that the reportative is somehow signaling the transition between the paranarrative frame of the story “he (the assistant) told me that…” and the narrative level proper “he (the character in the story) doesn’t use it (his money).” Hence, the utterance “it is said that there was a stingy man” belongs to an intermediate discourse level that integrates elements from the metanarrative and the narrative levels. The gestures that accompany this sentence are two beats – gestures that do not have a meaning but that rhythmically accompany speech – as illustrated in Fig. 7.

As McNeill has argued, beats take place when a character is introduced in a narrative, and they also “present some of the discourse-pragmatic content that also is part of story-telling (…) Thus a clause in which a beat is found often performs, not the referential function of describing the world, but the metapragmatic function of indexing a relationships between the speaker and the words uttered” (McNeill, Reference McNeill1992, p. 195). This is precisely what the beats are indexing in this example. On the one hand, the introduction of the character of the stingy man. On the other hand, they may also fulfill the metapragmatic function of indicating that the speaker only knows the story because somebody else told her.

After this sentence, there is a slight pause, and the speaker repeats almost the same utterance “it is said he was stingy for his money”; she begins to form a palm-up gesture by first bringing her right hand underneath her left hand, and showing the right palm up. In the next sentence, the left hand comes from underneath the right hand and she shows both palms up to her interlocutor (Fig. 8).

The gesture in Fig. 8 is known in the literature as ‘palm-presenting’ gesture (Kendon, Reference Kendon2004), ‘palm-presentational’ gesture (Cooperrider et al., Reference Cooperrider, Abner and Goldin-Meadow2018), ‘conduit’ gesture (Chu et al., Reference Cienki and Müller2013; McNeill, Reference McNeill1992, Reference McNeill2005), or ‘Palm-Up Open Hand’ gesture (Müller, Reference Müller, Müller and Posner2004). It belongs to the same gesture family as the palm epistemic gesture on Fig. 2b, but instead of moving the hands laterally when making the gesture, these are simply presented to the interlocutor. Some researchers argue that these are interactional or pragmatic gestures, where the speaker is presenting something to an interlocutor, or seems ready to receive something (Kendon, Reference Kendon2004, Reference Kita, Danziger, Stolz and Gattis2017). What Participant 4 is ‘presenting’ in this gesture – as if offering her argument for inspection – is the idea that this is a very selfish man, who does not want to spend his money. With this palm-presenting gesture, the participant invites her interlocutors to share their perspective on what, from the Chol point of view, seems to be the central moral dilemma of the story: what is the point of having money if we do not spend it?

5. Discussion

The American participants produced a consistent pattern of linear temporal gestures, gesturing both deictic (past/present/future) and sequential (earlier/later) temporal relationships along the transversal axis. These results are consistent with the type of temporal gestures reported by previous studies on temporal gestures with different Indo-European languages like English (Casasanto & Jasmin, Reference Casasanto and Jasmin2012; Cienki, Reference Chu, Meyer, Foulkes and Kita1998; Cooperrider & Núñez, Reference Cooperrider and Núñez2009) and French (Calbris, Reference Calbris1990). Chol speakers produced much fewer gestures than the English speakers, and none of the gestures that they produced were identified as temporal. Temporal language was present in the Chol retellings, but it was simply not accompanied by gesture that reflected any spatio-temporal meaning. A key characteristic of the Chol retellings was that they did not seem to be organized according to a linear-sequential alignment of episodes; in other words, in the Chol retellings, the events were not reported in the same order as they were originally presented in the Dickens in Chol text. Rather, the Chol retellings presented independent, self-contained descriptions of particular themes, among which no particular sequential order was established.

One of the main differences between the gestures produced by the English and Chol speakers was that many of the Chol gestures seemed to be more pragmatic in nature than the English retellings, which mostly co-occurred with narrative statements or conveyed meanings that illustrated, enacted, or represented some aspect of the story. By contrast, most of the Chol gestures were palm-up presentational gestures as the one shown in Fig. 9, or pointing gestures directed toward the Chol assistant who had told them the story, or to the researcher, as the ones shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The reportative particle -bi/abi,Footnote 5 (“he said,” “it is said”) was widely used in the Chol retellings; in the three retellings combined, it was mentioned a total of 63 times; on average, Chol participants used it 22 times in each retelling (Table 3).

Table 3. Use of the reportative particle -bi/abi in the Chol retellings

Fig. 9. Vertical linear gesture co-occurring with sequential predicate.

The widespread use of the reportative particle in the Chol retellings fulfilled a double function: first, it served as a metapragmatic commentary on the context in which the retelling of the story was taking place. The reportative particle in Chol, as in other Mayan languages, for example, in Yucatec, ‘provides a means for framing a report of one communication within another, especially speech within speech’ (Lucy, Reference Lucy and Arthur1993, p. 118). Additionally, by presenting the story as reported speech, the speaker adds a certain narrative distance between the content of the speech and herself as originator of that speech. In other Maya languages, like Mopan, the use of the reportative particle to frame speech as hearsay is crucial, especially when reporting ‘under doubtful empirical conditions’ (Danziger, Reference Danziger2010, p. 211). Adding narrative distance in this experimental context thus became a necessity for the participants. It is precisely this phenomenon that may account for the saliency of gesture at the paranarrative level in the Chol speakers’ stories, and for the very few gestures produced at the narrative level, none of which seemed to capture the temporal organization of events in the story. Overall, the study showed a dire contrast between the American and Chol interpretation of the story of A Christmas Carol, and notable differences in the speech-accompanying gestures used by Americans and Chol Mayans, respectively. While American speakers’ temporal utterances were often accompanied by the well-documented lateral timeline gestures, in Chol utterances, no lateral, sagittal, or vertical timeline gestures accompanied any form of temporal reference; the vast majority of gestures were pragmatic and had no explicit temporal content.

6. Temporal reference and gesture in a Chol traditional story

While the results from the Dickens in Chol task may well reflect the non-linear semantics of the Chol retellings, it is an open question whether the lack of linear temporal gesture might have been due to a lack of understanding of the linear development of the story because of cultural differences in the organization of narratives or the narrative content. To rule out the possibility that the striking differences in gesture production between American and Chol speakers were solely due to a misunderstanding of the story of A Christmas Carol, we can examine gesture production in a story of the Chol oral tradition.

6.1. Juanito and the Wits

I now turn to a qualitative analysis of the speech-accompanying gestures in a Chol traditional story, Juanito and the Wits. The speaker who participated in this task was male and in his seventies. The data were collected in a similar setting to the way in which the Dickens in Chol data were collected, the principal researcher sat to the speaker’s left and a research assistant sat to his right. We asked him to tell us a story of his choice, which with his permission we video-recorded. The story he chose to tell is well known in the Chol oral tradition, and it was presented as something that had ‘truly happened’ in a village nearby – this is characteristic of many Chol traditional narratives, which are believed to ‘be true’ by the Chol, or to have happened at an earlier time. In other words, the storyteller took the content of this story at face value. He told the story of a man named Juanito who was captured by the Wits, also known in Spanish as ‘el Dueño del Cerro’ – The Owner of the Mountain/Hill. The Wits is a mythological figure of the Chol oral tradition who dwells on mountains and caves, and controls the underworld and the animals that live in it, especially snakes and other wild animals that live in the woods that surround Chol villages. The Chol believe that, if he is not shown respect through the proper rituals, he may ruin their cornfields, or take a person’s soul. People are generally wary and fearful of the Wits, to the point where some do not even like to say his name. When a person’s soul is kidnapped by the Wits, it is believed that the person can die if proper retribution is not offered to him in exchange for their soul. When a person’s soul is captured by the Wits, he or she goes to live ‘inside’ the mountain or in a cave. This ‘inside’ space in the Chol folklore does not represent the physical interior of a cave or mountain; it is part of the underworld, where all kinds of non-human entities live. Once a person goes to the underworld, he or she rarely comes back to the world of the living.

The story of Juanito and the Wits has an internal chronology with episodes that succeed one another. In this story, the main character, Juanito, is kidnapped by the Wits, who is annoyed at him because Juanito likes to hunt his animals. While at the Wits’ home, the Wits’ daughter falls in love with Juanito and they get married. He remains 2 days inside the mountain, but, eventually, he wants to come back to visit his parents. He promises his wife that he will come back, and the wife gives him instructions, so he can visit his parents and then come back to live with her inside the mountain. She tells him specifically not to allow his parents to touch him when they see him, but as soon as they see him, his parents run to hug him, and at that moment Juanito forgets everything that happened, including his promise to his wife. Time goes by and Juanito’s parents decide it is time for him to get married, so they find him a wife. But just when they are about to get married, his ‘true’ wife – the Wits’ daughter – shows up, violently beats up the woman Juanito was about to marry, and at that moment he remembers everything. He is faithful to his wife and returns to the mountain with her and the Wits, leaving his parents forever.

This story presents an excellent material to analyze temporal gesture because it contains all kinds of temporal reference; it comprises a series of episodes that can be chronologically ordered, durations of events, and, most importantly, the story contains 27 examples of gestures that co-occur with temporal expressions and language that conveys deictic and sequential relationships between events, which are the linguistic expressions that commonly yield temporal linear gestures.

6.2. Overall gesture occurrence and narrative levels

Using a traditional narrative clearly paid off in terms of gesture occurrence. In the story of Juanito and the Wits, more gestures were identified (a total of 61 gestures) than the gestures made by the three Chol speakers combined (27 gestures) in the Dickens in Chol task. For each of these gestures, it was coded the narrative level – narrative, metanarrative, or paranarrative – at which they occurred. Table 4 also shows the gestures that co-occurred with clearly codable temporal expressions, or language that expressed deictic or sequential relationships between events. Finally, each of the 27 gestures co-occurring with temporal language was coded for presence or absence of linearity.

Table 4. Gestures in a traditional Chol narrative

The first striking difference between the gestures made by this participant and the other Chol participants is that in this traditional story, the vast majority of gestures (96.7%) occurred at the narrative level of discourse. This may be due to the fact that the story is well known in the Chol oral tradition and to the speaker, just like A Christmas Carol was well known to all American participants. For this Chol speaker, as for the American participants, there appears to be less of a need to emphasize the origin of the story, and a stronger tendency to bask in the details and content of the story. In this respect, the Chol traditional story is more similar to the American retellings than to the Chol retellings of A Christmas Carol. Because of the abundance of gestures at the narrative level of discourse, the vast majority of gestures in Juanito and the Wits are not pragmatically motivated, and they reflect both character viewpoint and narrator viewpoint. Like in the American retellings of A Christmas Carol, sometimes the storyteller “‘impersonates’ the actions and movements of characters in the story, but he also uses gestures that reflect the narrator’s perspective.

6.3. Gestures co-occurring with temporal reference

As Table 4 shows, of the 27 gestures that co-occurred with temporal expressions (deictic reference, sequential reference, durations of events, and temporal metaphors), only one of them was coded as being temporal-linear. This coding was maximally conservative, since it is extremely unclear whether this gesture is morphologically linear (simply enacting linear spatial movement) or semantically linear (representing a metaphorical timeline). ‘Example (6)’ shows the co-occurring speech for this gesture, which is shown in Fig. 9. At this point in the story, Juanito had been told by the Wits to go heal a deer he had wounded. Then, in sentence (6), he is told to blow through the hollow stalk of a plant named jaläl. Footnote 6

Sentence (6) is a sequential predicate (Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2019), a type of grammatical construction that expresses a sequential ordering between two or more different temporal events. Sequential predicates are not to be confused with simple yuxtaposed sentences (albeit yuxtaposition of clauses is also quite frequent in Chol and sometimes the yuxtaposed clauses can also express temporal or sequential relationshipsFootnote 7), and prosodic features are crucial to identify this type of construction. Sequential predicates are marked by rising intonation after the first predicate and falling intonation after the final predicate (Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2019). In sequential predicates, usually the first predicate becomes the anchor event or reference point for the events described in the following predicates. In (6), the first predicate refers to the moment when Juanito has finished healing the animal that he had wounded, and as soon as that action has been completed – this is marked with perfective aspect in the verb – someone (later, we learn that the person speaking to Juanito is his wife) instructs Juanito to ‘blow the jaläl’.

The gesture co-occurring with this sequential predicate shown in Fig. 9 has two parts. The first stroke is an abstract deictic gesture with a right finger extended at the center of the gesture space, right in front of the speaker. This first stroke co-occurs with the first clause of the sequential predicate “he finished healing it.” After making this pointing gesture, the speaker retracts his right hand for a second. In the second part of the gesture, the speaker moves his right hand vertically and performs a second abstract pointing gesture with his right index finger extended, pointing at a spot right above his head. This second abstract pointing gesture co-occurs with “he was told ‘blow the jaläl’.” Because the speaker is pointing at two locations along an axis, and the co-occurring speech refers to two sequentially ordered events (Juanito finishes healing the animal and after that, his wife speaks to him), to be maximally conservative, we coded this gesture as linear-temporal. If this was the case, what the gesture would be showing the flow of time along a vertical axis, with the first (or anchor) event located at the center of the gesture space, in front of the speaker’s chest, and the posterior event located in the center-upper periphery of the gesture space, over the speaker’s head. This is very interesting, since only languages with a vertical reading and writing orientation, like Mandarin Chinese, have been shown to influence time conceptualization, so that events are located along the vertical axis (Bergen & Chan Lau, Reference Bergen and Chan Lau2012). But it is not possible that reading and writing directions are influencing this particular case, since, first, the speaker was non-literate (something quite common in this area for men of his age), and, second, the alphabetic system for writing down Chol that has been recently developed is horizontal, with left-to-right, not vertical orientation.

Nevertheless, while it is possible that the linearity of this gesture is expressing a sequential connection between the first and second predicates, it is not entirely clear that the two abstract pointing gestures specifically represent the two different event times or a sequential ordering of these different event times. In fact, this speaker has a tendency to use the center-upper periphery of the gesture space throughout the story. Identical pointing gestures that take place in the center-upper periphery are shown in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. Nontemporal upward-pointing gestures.

Another plausible interpretation, therefore, is that in the first gesture, the participant is simply pointing at one of the interviewers (the research assistant, located to his right); conversely, the second abstract pointing gesture may not reflect the second event along a metaphorical timeline, but it may be a catchment gesture. McNeill and colleagues suggest that a catchment gesture “is recognized when two or more of gesture features recur in at least two (not necessarily consecutive) gestures. The logic is that the recurrence of an image in the speaker’s thinking will generate recurrent gesture features. Recurrent images suggest a common discourse theme. In other words, a discourse theme will produce gestures with recurring features” (McNeill et al., Reference McNeill, Quek, Mccullough, Ansari, Duncan, Furuyama, Bryll and Ma2001, p. Reference Bourdieu and Pitt-Rivers2). Morphologically, similar upward-pointing gestures have also been documented in Yucatec as referring to a ‘distant-remote-unknown’ space and time, which comprises both past and future (Le Guen & Pool Balam, Reference Le Guen and Pool Balam2012, p. Reference Cooperrider and Núñez10). Hence, a third possibility is that throughout the whole story, the speaker’s overuse of the upward periphery of the gestural space may reflect an association of this story with a remote space and time. Even if the story was presented to the interviewer as something that happened to someone who lived in a nearby village, once Juanito enters the Wits, he has entered a space and time that are no longer part of the human world.

The remaining 26 gestures co-occurring with temporal expressions do not exhibit linearity of temporal conceptualization; the vast majority of these are representational gestures, pointing gestures, or beats. Fig. 11 shows a typical example of how sequential predicates are usually gestured in this story. In the sequence of events described in ‘example (7)’, the Wits’ daughter is telling Juanito what to do; she tells him “when my dad is starting to show you [how to heal the animal], [you] immediately prick him upwards.” The first event time is described with a progressive predicate, which acts as anchor event for the second predicate: first, the Wits is showing Juanito how to heal the animal he had wounded. Then, the daughter suggests, he must use the stalk he had sharpened ‘immediately’ to prick him ‘upwards’, suggesting that the Wits must be pricked from the bottom up. The predicate “prick him upwards” represents the second event time, and both events are sequentially connected. Fig. 11 shows the speaker performing these two gestures. In Fig. 11a, a beat-like gesture with a right finger extended co-occurs with the first predicate “when dad is starting to show you.” This gesture does not depict any kind of point along a timeline, but rather, it mimics the gestures people often make when giving instructions to others about what to do. In other words, it is a character-viewpoint gesture (McNeill, Reference McNeill1992), where the speaker impersonates the Wits’ daughter talking to Juanito. After that, the right hand is retracted for a second; the second gesture shown in Fig. 11b co-occurs with the second predicate “immediately prick him upwards”; there, the speaker moves quickly his right hand up, doing a small loop inward with his right hand and moving it quickly over his head. This is a representational gesture that simply shows movement ‘upwards’, as the co-occurring speech indicates.

Fig. 11. Beat and representational gestures co-occurring with sequential predicate.

Fig. 12 shows a representational iconic gesture co-occurring with the temporal deictic adverb wa’le, ‘now’. These kinds of temporal deictic adverbs are crucial for studying temporal conceptualization, since they express temporal deictic relationships between events, and in languages that do not have grammatical tense, they may convey tense-related meanings. The gesture spans across two sentences, as shown by the square brackets that mark the onset and retraction of the gesture. The temporal deictic adverb wa’le ‘now’ is accompanied by an iconic gesture showing a man sharpening the jaläl, one of his fingers representing the stalk and the other representing the knife that is used to sharpen it. In spite of reflecting the temporal semantics of the adverb, it simply illustrates (and extends) the action described in the previous sentence. ‘Example (8)’ is also interesting because, in addition to the deictic time expressed by the adverb wa’le, there is also a sequential order between Juanito’s sharpening of the stalk and the Wits’ daughter addressing him. In other words, the Wits’ daughter’s direct speech is anchored in the preceding predicate. It is not that the Wits’ daughter comes, and Juanito starts to sharpen the stalk, but the other way around. This sequential ordering is also not reflected in the gesture, which simply enacts Juanito sharpening the stalk.

Fig. 12. Representational iconic gesture co-occurring with temporal deictic adverb.

Sentence (9) contains a temporal metaphor and a subordinate temporal clause. The temporal metaphor is extremely interesting because it reflects a moving-ego perspective (Clark, Reference Clark and Moore1973), the literal translation of the metaphor tyaj oraj is ‘to find the time’. The word used to refer to time is ‘oraj’, a borrowing from the Spanish word hora (hour), which can be loosely translated as ‘time’ or ‘hour’ and has now become a Chol word to designate time generally, since there is no original word for the abstract concept of time in Chol (Rodríguez & López Reference Rodríguez, López, Pitarch and Kelly2019). An equivalent expression in English would be ‘the time came when…’ or ‘llegó la hora’ in Spanish, but in these English and Spanish metaphors, time is moving toward a static observer/experiencer. In this Chol metaphor, it is not the time that ‘moves’, but the observer-experiencer who ‘finds’ a specific moment in time. The temporal metaphor is followed by a subordinate temporal clause which explains what happens in that ‘moment’, that a girl shows up. The ‘girl’ referred to is the woman with whom Juanito’s parents are trying to arrange a marriage. The co-occurring gestures for ‘example (9)’ are shown in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13. Gestures co-occurring with temporal metaphor and temporal subordinate clause.

Interestingly, the temporal metaphor does not have a co-occurring gesture, as shown in Fig. 12a, but the speaker does make a quick beat gesture (Fig. 12b) co-occurring with the word kwañdo ‘when’, another Spanish borrowing (‘cuando’) that can introduce subordinate temporal clauses in Chol. This quick beat gesture is followed by a small gesture where the speaker briefly shows both palms up (Fig. 12c). It is hard to discern whether this is a quick palm-up presentational gesture, or a simple readjustment gesture where the speaker is just looking at his hands. In any case, what it is clear is that it does not show any kind of linearity.

7. Discussion

A qualitative analysis of the Juanito and the Wits story revealed that, when telling a story of the Chol tradition that is well known to the speaker, pragmatically motivated gestures that occur at the metanarrative and paranarrative levels are much fewer than gestures occurring at the narrative level. Not only is overall gesture production higher when the speaker is telling a story of the Chol oral tradition, but gestures at the narrative level comprise the vast majority of speech-accompanying gestures (96.7% in the Juanito and the Wits story). The most interesting observations, nonetheless, come from the analysis of gestures co-occurring with sequential, deictic temporal expressions and temporal metaphors. Twenty six out of the 27 gestures co-occurring with clearly codable temporal language that were analyzed did not reflect any kind of timeline that resembled those made by the American speakers in the Dickens in Chol task. Only one gesture was marked as possibly reflecting some kind of linear semantics. Given that this was the only possible (yet unclear) example of a linear temporal gesture found in this narrative, and not a similar pattern for gesturing consecutive events was identified, we cannot conclude that this kind of linear vertical gesture is a common way of gesturing sequential ordering of events in Chol. Future research could address whether this type of upward-pointing gesture, which seems morphologically similar to the ‘distant space and time’ gestures reported by Le Guen and Pool Balam for Yucatecan (Le Guen & Pool Balam, Reference Le Guen and Pool Balam2012), may represent events or situations that happen in a remote space or time from the speaker’s perspective, or even a mythical ‘story’ time that sets the events of the story apart from those that happen in everyday life.

8. General discussion

In the first part of this study, we compared overall gesture production by speakers of American English and Chol Maya while retelling the same story. The results showed that the American speakers made significantly more gestures than the Chol speakers, especially at the narrative level of discourse. When examining the production of temporal gestures in both populations, the American participants made significantly more temporal gestures and linear gestures than the Chol participants while retelling the story of A Christmas Carol to an interviewer. Most importantly, in spite of the linear and chronological organization of the stimulus, the Chol participants made no temporal linear gestures in their retellings of A Christmas Carol.

A qualitative analysis of the gestures made by a Chol speaker while telling the traditional story Juanito and the Wits showed that overall, when telling a story of the Chol oral tradition, the vast majority of speech-accompanying gestures occurred at the narrative level. In regard to the presence of gestural timelines, 96.29% of the gestures co-occurring with sequential, deictic temporal expressions and temporal metaphors did not reflect any kind of timeline that resembled those made by the American speakers in the Dickens in Chol task. The only gesture that could possibly contain a dubious linear semantics was morphologically similar to gestures co-occurring with linguistic expressions that did not contain explicit temporal reference.

Appendix: ‘Dickens in Chol’ text, with free translation in English

Añbi juñtyikyil kixtyaño, weñ kabäl itya’k’iñ.

‘It is said there was a person, who had a lot of money.’

Ñoj chukbi.

‘It is said he was very stingy.’

Mukbi iweñ loty majlel ityak’iñ, ma’añbi mi isaj jisañ, ibajñejach icha’añbi.

‘It is said he kept his money well hidden, he wouldn’t share anything, he kept everything for himself.’

Ma’añ iyijñam, ma’añ iyalo’bilob, ma’añ chu’ añ icha’añ.

‘He didn’t have a wife, or kids, he didn’t have any family.’

Jiñachbi tyak’iñ, i ma’añ mi isaj käñ, yä’ächbi ilotyo icha’añ.

‘For that reason, he wouldn’t spend any money, and he kept everything for himself.’

Ambi jump’ej abälel, ta’bi maj tyi wäyel.

‘One night, he went to sleep.’

Tyi kej tyi ñajal.

‘He started to dream.’

Tyi ñajälel ta’bi säk tyäli li Ch’ujlel Wajalixbä.

‘In his dream, he was visited by the Ghost of the Things Past.’

I Ch’ujlel Wajalixbä ta’ bi weñ kej ipäsbeñtyel bajche’ tyi koli wajali, cheñak chutyo.

‘And the Ghost of the Things Past showed him how he grew up, when he was young.’

Tyi kej weñ päsbeñtyel weñ tijikña ipusik’al cheñak chutyo, i bajche’ yila iyotyoty baki tyi koli yik’oty ityatyob, iyerañob, y bajche’ muk tyi alas yik’oty yañbä ipiä’lobä.

‘He started to show him how happy he was when he was still young, and how it was at his home where he grew up with his parents, his brothers, and how he used to play with his friends.’

Che’ jiñi, li wiñik ta’bi p’ixi, i ta’bi cha’ ochi wäyel.

‘And just like that, the man woke up again, and he went back to sleep.’

Ta’bi kej cha’weñ ñajlem yañbä Ch’ujlel, li Ch’ujlel Choñkolbä Ñumel Wa’li.

‘He started to dream another Ghost, the Ghost of What is Happening Now.’

Jiñi Ch’ujlel ta’bi weñ kej ipäsbeñtyel bajche’ choñkol ñuñsañ oraj jiñi wiñiki.

‘This Ghost started to show him how he was living.’

Ta’bi ipäsbe bajche’ ñoj chuk, jiñ cha’añ ma’añ ipiä’lob, ibajñe ichumul tyi iyotyoty.

‘He showed him how stingy he was, and for that reason he didn’t have any friends, he lived all alone in his home.’

Che’ jiñi, li wiñik ta’bi cha’p’ixi, i ta’bi cha’ ochi wäyel.

‘And that way, the man woke up again, and went back to sleep.’

Ta’bi kej cha’weñ ñajlem yañbä Ch’ujlel, li Ch’ujlelbä Tyalbä.

‘He started to dream again with another Ghost, the Ghost of the Things to Come.’

Ili Ch’ujlel ta’bi kej päsbeñ bajche’ mi ikajel tyi ñoxañ i bajche’ mi ikajel tyi sajtyel.

‘This Ghost showed him how he was going to grow old, and how he was going to die.’

Ta’bi ipäsbe baki mi kej mujkel tyi kap’sañto.

‘He showed him how he was going to be buried in the cemetery.’

Chä’äch bajche’ ibajñel, ma’añ majch iyujty’añ.

‘He was all alone, there was nobody to mourn for him.’

Ta’bi icha’p’ixi li wiñiki, ta’bi icha’weñ kej ipeñsaliñ.

‘The man woke up again, and he started to think again.’

“Mach kom bajñel sajtyel, mach kom lajmel che’ bajche’ jiñ” Che’bi.

‘“I don’t want to die alone, I don’t want to end like that” He said.’

Jiñ cha’añ, tyi ik’extyä ipusik’al, ta’bi ikäyä ichuklelbä, i ta’bi iweñ keje tyi ikäñ itya’k’iñ yik’oty ipiälob.

‘For that reason, he changed his heart, and he quit his stinginess, and he started to use his money with his friends.’

Che’bi tyi ujtyi jiñi

‘That’s the end of the story.’