“We cannot share experiences so we cannot compare perceived sensations directly.”

—Bartoshuk et al. (Reference Bartoshuk, Duffy, Green, Hoffman, Ko, Lucchina, Marks, Snyder and Weiffenbach2004, p. 110)I. Introduction

Ashenfelter (Reference Ashenfelter2016) considers the expert's role one of two central questions in wine economics as elsewhere in cultural economics (e.g., Ginsburgh, Reference Ginsburgh, Rizzo and Towse2016). Researchers seeking evidence of wine quality often use expert ratings, despite consumer complaints, skepticism that it is “junk science” (e.g., Derbyshire, Reference Derbyshire2013), and considerable literature questioning their validity and reliability (e.g., Ashenfelter, Reference Ashenfelter1986–1997; Ashenfelter and Jones, Reference Ashenfelter and Jones2013; Marks, Reference Marks2015; Storchmann, Reference Storchmann2015).

Considerable research has explored how ratings correlate with transaction prices, testing whether they help “explain” willingness to pay (WTP). The best evidence is mixed, coming primarily from a narrow, though financially important, wine market—commercial auctions of classified Bordeaux (e.g., Oczkowski and Doucouliagos, Reference Oczkowski and Doucouliagos2015; Luxen, Reference Luxen2018; Faye and Le Fur, Reference Faye and Le Fur2019)—which provides rare published data on “market-clearing” transactions.

Mixed results mean that wine ratings are not necessarily reliable guides to wine quality, enjoyment, and WTP. More fundamentally, as a form of hedonic quality index, they involve questionable interpersonal comparisons—say, between experts or between an expert and oneself since different palates may differ over a flavor's appeal. Saying that experts can tell consumers what they will like is questionable unless, of course, knowledge of the expert ratings predetermines the consumer hedonic experience (e.g., Ashenfelter and Jones, Reference Ashenfelter and Jones2013).

This paper explores wine ratings as a form of hedonic psychophysical scaling (PS), using the scaling literature's analytic framework. Well-established critiques of hedonic scaling raise fundamental questions about the reliability of ratings—in effect, adopting someone else's preferences as one's own—and the interpretation of any price-rating correlation.

Food scientists have grappled with the challenge of interpersonal hedonic evaluation, but the underlying point is that interpersonal comparisons are inherently unreliable absent shared preferences. The use of wine ratings in econometric analysis of wine price determinants—and by the public more generally in evaluating wines—has been largely uncritical of their underlying rationale. The logical problems are as much psychophysical as econometric; and, perhaps because this is interdisciplinary, the economics literature has overlooked the psychophysical problems discussed in the following sections.

II. Psychophysical Scaling: Ratings as Hedonic Scales

Broadly defined, winemaking is food processing. Food processors use techniques like PS to choose appealing product characteristics: “[PS quantifies] mental events [responses], especially sensations and perceptions [such as liking/disliking and intensity of sensation], after which it is possible to determine how these quantitative measures…are related to quantitative measures of the physical stimuli [signals]” (Marks and Gescheider, Reference Marks, Gescheider, Pashler and Wixted2002, p. 91).

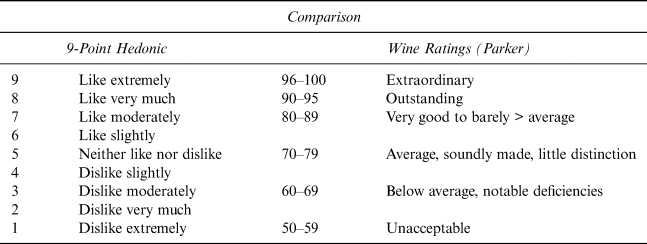

Wine rating resembles hedonic rating, which is one example of PS—a “numerical scale used to indicate degree of liking and/or disliking” (Lawless, Reference Lawless2013, p. 391). It is the familiar worst-to-best scale used to describe preferences for everyday products (e.g., brands of coffee). Wine ratings are simply scores along some numbered like-dislike spectrum with (1) extremes defined by experts’ opinions of best/worst (2) within their selections of a wine's peers with (3) supporting tasting notes. Table 1 provides a popular hedonic scale (left column) next to wine critic Robert Parker's rating scale. The scales are similar but not identical. For example, descriptions of extremes are not precise, and experts may combine hedonic categories. Published rating scales vary, but all follow this general pattern.

Table 1 Wine Ratings as a Hedonic Scale:

An Example (signal = flavor; response = rating)

III. Issues and Our Focus: Interpersonal Comparisons

In a widely cited survey, Lim (Reference Lim2011) critiques hedonic scaling (HS) and discusses important challenges that apply also to ratings:

• The environment in which the scaling occurs, uncontrolled influences on subjects (external (e.g., “pollutants” from various test environments); internal (e.g., impacts of emotion, memory)), and mismeasurement of controlled influences (e.g., recent tasting experiences).

• Measurement problems: Subjects use a scale to represent levels and changes in hedonic responses, but subjects’ articulations of such responses (e.g., scores, ranking, words, distances on a spectrum) and how finely they discriminate differ. Does the available scale allow accurate representation of relative degrees of liking?

Added to this is intrapersonal consistency—an individual's likelihood of consistent responses in repeated trials. This is fundamental in wine rating: an expert should give the same rating in subsequent evaluations. Because retaining and retesting subjects is difficult, evidence of intrapersonal consistency with HS seems almost nonexistent—and similarly for carefully conducted subsequent blind wine tastings.

Of particular importance are interpersonal comparisons—in effect, what consumers do when they formulate their WTP using one or more expert (hedonic) ratings. Interpersonal HS differences have received considerable attention. Marks and Gescheider (Reference Marks, Gescheider, Pashler and Wixted2002) conclude in a survey: “An important [PS] problem…has been to determine how much…variability reflects real interindividual variation in the relation between stimulus and sensation….[M]agnitude estimates given by individual observers cannot be meaningfully compared in any simple or direct manner” (pp. 120, 123; emphasis added). In this context, Lim (Reference Lim2011, p. 739) cites two criticisms of HS. First, “…due to its inequality of scale intervals and the lack of a zero point…the scale can yield only ordinal- or, at best, interval data (i.e., ordered metric). Thus, the scale…cannot provide meaningful comparisons of hedonic perception between individuals and groups…” (emphasis added). Steps on the hedonic scale simply order preferences: hedonic distances between ratings may vary, and the meaning of a one-point change can vary by individual.

Furthermore, lack of a common zero point means that “the ratio of the numbers assigned to objects has no meaning”: for example, 50°C is more thermal energy than 25°C, although not necessarily 100% warmer (Cardello, Reference Cardello, Taub and Singh1998, p. 14). A five-star wine surpasses a four-star but not necessarily by 20%.

Lim's second point is that:

“…from a statistical standpoint, because the data…are categorical and discrete without a true zero point, …statistical analyses [are] limited, i.e., nonparametric statistics. However, it is common practice… to use more powerful parametric statistics [e.g., ANOVA] to analyze data collected with the scale, although it is mathematically inappropriate…”

We do not know the distribution of hedonic data and their parameters, so it is inappropriate to perform statistical analyses that assume otherwise (e.g., multivariate regression).

Bartoshuk highlights not only the misapplication of hedonic ratings but also persistent failure to stop it:

“…except for…mind readers, people cannot share each other's experiences of pleasure and pain. Yet with the misuse of [hedonic] scales, we sometimes act as if we can…. Incidentally, this error keeps being rediscovered.” (Reference Bartoshuk2014, p. 91)

IV. Interpersonal Comparisons with Magnitude Matching

Kalva et al. (Reference Kalva, Sims, Puentes, Snyder and Bartoshuk2014) address this problem with an improved methodology for comparisons. Give Group I (GI) two 9-point scales for rating foods: a hedonic scale (1 = Dislike extremely) and a sensory (intensity) scale (1 = No taste sensation (e.g., bitterness), 9 = Extreme sensation). Ask a statistically comparable Group II (GII), first, to identify four extreme life experiences that set boundaries:

• Among all sensory experiences, “no sensation” (= 0) and the “strongest imaginable sensation” (= 100); and

• Among all hedonic experiences, the “strongest imaginable liking” (= +100) and “strongest imaginable disliking” (= –100).

The GII exercise involves food, so the boundary setting must be orthogonal, involving non-food sensory (e.g., loudness) and hedonic (e.g., visual) experiences.

In effect, GII scales—general Labeled Magnitude Scales (gLMS)—set absolute boundaries of lifelong sensory and hedonic experiences. While differing between any two GII subjects (objectively absolute standards measuring such reactions are nonexistent), each GII subject still compares the foods to “the same” subjective absolute scale (i.e., the limits of each one's hedonic and sensory experience). This norms the ultimate like-dislike scale to the subjects’ best and worst experiences ever. Comparing their relative rankings is closer to using an absolute standard with this than without. This technique of “magnitude matching” (ibid., p. S239) establishes matching scales against which we measure individual sensory and hedonic differences.

Kalva et al. found a more meaningful interpersonal comparison. Subjects with different (sensory) sensitivities exhibited different levels of liking and disliking (hedonic)—in particular, statistically significant positive correlations with liking and negative correlations with disliking—and subsequent studies have concurred (e.g., Williams et al., Reference Williams, Bartoshuk, Fillingim and Dotson2016). Those using the gLMS consistently exhibit a strong correlation between the hedonic intensity of liking (positive) or disliking (negative) and perceived (sensory) intensity. With foods, the authors attribute sensory intensity differences to different degrees of “tasters”— perhaps minimal, medium, and super. For those using simply the 9-point scales, the liking/disliking-sensory intensity correlations were almost never significant (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 While not producing robust interpersonal comparisons (e.g., utility), this model highlights a fundamental problem in comparing hedonic ratings and begins to address it. The significant correlations found between taste sensitivity and degree of liking/disliking are less important than demonstrating that “we cannot compare perceived sensations directly.”

Figure 1 gLMS and 9-Point Hedonic Comparison

Source: Kalva et al. (Reference Kalva, Sims, Puentes, Snyder and Bartoshuk2014, p. S242). Used with permission.

While the difference studied was sensory sensitivity, numerous other potential sources of difference come to mind but remain largely untested: for example, olfactory acuity, age, gender (Bodington and Malfeito-Ferreira, Reference Bodington and Malfeito-Ferreira2018), or perhaps cultural background (“wine cultures” vs. others).

What is the relevance for wine ratings? Acting as if we can compare two conventional hedonic ratings to evaluate differences in coffee drinkers—or taking one's rating (expert) as a good predictor of another's (consumer)—is the mistake that gLMS scaling addresses. Acting as if we can compare two conventional hedonic ratings to compare two wine tasters—or taking one's rating (the expert's) as a good predictor of another's (the consumer's)—is, at best, naïve. Because knowledge of a wine can be elusive, we search for expert advice. When we follow it and are surprised or disappointed, the experts’ errors are in claiming that they know what consumers will enjoy.

Thus, in our popular use of ratings, “we fail to see differences that are real” (Bartoshuk, Reference Bartoshuk2014, p. 92). If the consumer disagrees with the expert, what is wrong? Probably nothing: finding some or all ratings unhelpful may be fully rational.

V. Other Interpersonal Comparisons: Wine Judges

Recent papers analyze wine tasting data—especially evaluating wine judging—and discuss alternative methods for evaluating the consistency of those judgments (e.g., Ginsburgh and Zang, Reference Ginsburgh and Zang2012; Olkin et al., Reference Olkin, Lou, Stokes and Cao2015; Cao and Stokes, Reference Cao and Stokes2017; Bitter, Reference Bitter2017). Maximum ranking consistency—ranking wines in the same order—is desirable; uncorrelated rankings reveal nothing about relative quality (Olkin et al., Reference Olkin, Lou, Stokes and Cao2015, p. 5). These papers address some of the same statistical questions raised here (e.g., nonparametric analyses required for ordinal data (ibid., pp. 8–13)). They do not identify wine ratings as HS, but one paper (ibid.) cites related literature.

To understand this literature's relevance, assume that the consumer is a wine judge, has scored and ranked several wines, and wishes to know how her evaluation compares to others—the putative expert(s). That would be one context in which the consumer could learn from the expert's evaluation: the greater the consistency, the more reliably the consumer might follow that expert's recommendation. If consumers actually evaluated the quality of expert evaluations this carefully, that would mitigate some of our concerns. The consumer could search for the expert rankings most consistent with hers. Others have proposed this after questioning the value of expert ratings (e.g., Cicchetti and Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti and Cicchetti2014).

Compared to rankings, wine ratings present greater challenges. First, they are ordinal but not cardinal. Neither what they are counting nor the equality of one-point changes nor their zero points are well defined. Second, assuming cardinality often leads to assuming an underlying, unobserved wine quality (e.g., Olkin et al., Reference Olkin, Lou, Stokes and Cao2015, p. 17; Cao and Stokes, Reference Cao and Stokes2017, p. 205) around which judges’ ratings are distributed. Our discussion questions that: if ratings are taken as a measure of hedonic enjoyment, the distribution of underlying, unobserved quality can differ by individual. Magnitude matching attempts to adjust for such individual differences in those distributions.

VI. Conclusion

Wine consumers often use expert ratings to guide their WTP. If the expert evaluations include personal enjoyment, then consumers are assuming that they share the experts’ hedonic preferences. The psychophysical literature questions simple comparisons of subjects’ liking and disliking and recognizes that individual hedonic preferences differ, and naïve comparisons can be misleading. Bartoshuk warns of the persistence of this research error (e.g., Pickering and Hayes, Reference Pickering and Hayes2017).

Magnitude matching moves expression of hedonic preferences closer to a shared scale—“the context of all affective experience.” Our focus has been explaining the similarity of hedonic scales to wine rating scales and extrapolating the interpersonal comparison problem from the psychophysical literature to consumers’ use of expert ratings. Research on magnitude matching has demonstrated the problem with simple comparisons by illuminating individual differences that such comparisons mask, “fail[ing] to see differences that are real.”