“Gentlemen, in the little moment that remains to us between the crisis and the catastrophe, we may as well drink a glass of champagne.”

—Paul Claudel (“In Time of Trouble,” Reference Claudel1956, p. 264)I. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a once-in-a-lifetime event that has already shown major effects on societies and economies around the globe. In this article, we use survey data to investigate its impact on the drinking behavior of wine consumers in France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. More specifically, we assess if the lockdown led to a change in the frequency of wine consumption. Then, we explore possible heterogeneities at country and individual levels controlling for demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial variables. For more details about lockdown policies across Europe, see Plümper and Neumayer (Reference Plümper and Neumayer2020).

The objectives of this article are twofold. From a practical perspective, the wine industry is confronted with an unprecedented level of uncertainty. It is, therefore, important for all market players to have precise data about how wine consumption and purchasing patterns have evolved during the first lockdown. Moreover, reliable information on emerging trends, which may affect the demand for wine in the coming months, is urgently required. From an academic point of view, this situation represents a unique opportunity to investigate the drivers of wine consumption during periods of high uncertainty. Some researchers already expect a public health crisis resulting from alcohol use and abuse in the context of social isolation and stress during the COVID-19 lockdown (Clay and Parker, Reference Clay and Parker2020),Footnote 1 yet some of the most reputed newspapers have published advice to help their readers organize virtual happy hours to maintain some form of socialization.Footnote 2

To achieve the article's objectives, we conducted a large-scale online survey in France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain—Latin countries that share several cultural similarities. The survey includes questions related to consumer consumption and purchasing habits of wine and other alcoholic beverages (beer and spirits) before and during the lockdown; possible economic, emotional, and psychological effects of the lockdown; and sociodemographic variables. The study comprises 7,324 respondents from these four countries (6,920 living in those countries and 404 living abroad).

Our results can be summarized as follows. First, we explore the first lockdown trends in wine consumption in the whole sample and by country using, respectively, chi-square tests and the Marascuilo procedure. More respondents maintained their wine consumption frequency than increased or decreased their consumption. Wine consumption frequency significantly held up better than other alcoholic beverages. Nevertheless, country specificities appear in France, where the proportion of respondents who increased their wine consumption frequency is not significantly different from the proportion of those who maintained it, and in Portugal, where maintenance is significantly higher than elsewhere.

Second, we explore the individual heterogeneity of behaviors for the whole sample and by country using an ordered logit model. We note both substitution effects with other alcoholic beverages and the loyalty of wine consumers to wine. Respondents who increased their wine consumption frequency were moderate drinkers before the lockdown. They also increased their spending per bottle of wine.

Changes in consumption situations also have appeared. Consumption frequency has been maintained overall. The fewer digital gatherings, the more Italian and Portuguese respondents reduced their wine consumption. Family consumption increased in Italy. The relationship between anxiety and wine consumption frequency increasing is more ambiguous than suggested by the literature, except partially in France. However, the significant association of wine consumption frequency with certain consumption motivations (relaxing, health), or low perception of the crisis as an opportunity for positive social and environmental changes, suggests that anxiety could be related to the increase in consumption.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. Section II briefly reviews the existing literature resulting in four research questions. Section III presents the dataset. Section IV is devoted to the empirical analysis, and Section V concludes.

II. Uncertainty and the Consumption of Alcoholic Beverages

A. Review of the Literature

Mass tragic events such as infectious diseases or epidemic events often generate waves of intense fear and anxiety, negatively affecting individuals’ well-being (Balaratnasingam and Janca, Reference Balaratnasingam and Janca2006), as well as increasing psychological disorders, traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, O'Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely, Arseneault, Ballard, Christensen, Cohen Silver, Everall, Ford, John, Kabir, King, Madan, Michie, Przybylski, Shafran, Sweeney, Worthman, Yardley, Cowan, Cope, Hotopf and Bullmore2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang, Wong and Hyun2020; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Rospleszcz, Greiner, Dellavalle and Berger2020). Specifically, COVID-19 has disrupted people's routines and generated extreme fear and anxiety. Arpaci, Karataş, and Baloğlu (Reference Arpaci, Karataş and Baloğlu2020) go as far as to propose the use of the term corona phobia in addition to already existing types of fears (natural environment, animal, blood-infection injury, situational, social phobia, and agoraphobia) (APA, Reference American Psychiatric Association2013). As a consequence, people can “develop disproportional cognitive, affective, or behavioral responses to the objects and situations that they associate with the COVID-19 pandemic and severe deteriorations may occur in the physiological and psychological functionalities” (Arpaci, Karataş, and Baloğlu, Reference Arpaci, Karataş and Baloğlu2020, p. 2).

Sensationalist headlines in the mass media foster anxiety and fear, inducing people to oscillate between denial and phobia (Pappas et al., Reference Pappas, Kiriaze, Giannakis and Falagas2009). The generalized fear that affects people worldwide has been further fueled by the disease's severe symptoms, uncertainty about its outcome, implementation of massive containment measures (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Ni, Hu, Liang, Ou, Liu, Shan, Lei, Hui, Du, Li, Zeng, Yuen, Chen, Tang, Wang, Chen, Xiang, Li, Wang, Liang, Peng, Wei, Liu, Hu, Peng, Wang, Liu, Chen, Li, Zheng, Qiu, Luo, Ye, Zhu and Zhong2020; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Li, Ren, Zhao, Hu, Zhang, Fan, Xu, Gu, Cheng, Yu, Xia, Wei, Wu, Xie, Yin, Li, Liu, Xiao, Gao, Guo, Xie, Wang, Jiang, Gao, Jin, Wang and Cao2020), and the fact that the event is unprecedented for most individuals (Soraci et al., Reference Soraci, Ferrari, Abbiati, Del Fante, De Pace, Urso and Griffiths2020).

From an economic perspective, the COVID-19 crisis has been an exogenous shock to most local and international markets. For an empirical case study of impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on global beverage markets see Wittwer and Anderson (Reference Wittwer and Anderson2021). In the past, the wine industry has been affected by wars (Chavis and Leslie, Reference Chavis and Leslie2009), terrorist attacks (Gergaud, Livat, and Song, Reference Gergaud, Livat and Song2018), natural disasters such as wildfires (Thach, Reference Thach2018), and earthquakes (Forbes and Wilson, Reference Forbes and Wilson2018), among other events. The COVID-19 crisis is another extreme and tragic event that can have an immediate impact on alcohol consumption because it generates stress and anxiety among virtually all populations. The lockdown has seriously disrupted social habits and consumption. Indeed, the desire to reduce negative affect and to enhance positive affect are central motivational processes underlying alcohol consumption. Research has shown that alcohol consumption is associated with stress exposure and drinkers anticipate a stress-relieving effect (see Bartone et al., Reference Bartone, Johnsen, Eid, Hystad and Laberg2017, in a military context). In that sense, people drink to be able to cope better with negative emotions. People also drink alcohol for social reasons and/or for sensation seeking, leading to enhancement drinking (drinking to enhance positive affect) (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Frone, Russell and Mudar1995). Additionally, high scores on extraversion (associated with sociability) increase the expected frequency of wine consumption (Gustavsen and Rickertsen, Reference Gustavsen and Rickertsen2019).

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, physical separation (or social distancing) to prevent the spread of the virus has led to feelings of isolation and loneliness, increasing the prevalence of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorders, and insomnia in the population (Banerjee and Rai, Reference Banerjee and Rai2020). However, during the lockdown, technological devices have provided a way for people to maintain social connections with friends, family, their social networks, and/or the wider community (Marston, Musselwhite, and Hadley, Reference Marston, Musselwhite and Hadley2020). Digital socialization has created new occasions for alcohol consumption. The mobile phone application WhatsApp, for example, provides opportunities for synchronous drinking in virtually connected, spatially separated locations (Moewaka Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, McCreanor, Goodwin, Lyons, Griffin and and Hutton2016).

B. Research Agenda

Based on this discussion, we examine four related research questions. The literature is yet inconclusive about the impact of uncertainty on wine consumption. The COVID-19 crisis has disrupted distribution channels and reduced social interactions, suggesting a strong reduction in wine consumption frequency. The data enables us to analyze from the perspective of wine drinkers whether their consumption of other alcoholic beverages has been affected in the same way during the lockdown. This leads us to the first question.

-

Question 1: Did respondents consume wine more frequently during the lockdown in both absolute terms and relative to other types of alcohol (beer and spirits)?

If wine has well-known social and cultural roles, these contexts could introduce heterogeneity in wine consumption behavior during the lockdown. Thus, our second question investigates possible country heterogeneity.

-

Question 2: Did wine consumption patterns of respondents during the lockdown significantly depend on their country of residence in Latin Europe?

The heterogeneity of behaviors can be not only social and cultural but also individual. Status, consumption patterns, supply habits, perception of risk and loneliness, and substitution drink effects are all relevant individual factors. Our last two questions investigate this individual level of heterogeneity.

-

Question 3: Which individual factors explain the observable evolution in wine consumption frequency of respondents during the first lockdown in Latin Europe?

-

Question 4: Did the effect of individual heterogeneity have a different profile depending on the country of residence?

Our study is purposely biased toward wine drinkers to discover recent trends that are relevant to the wine industry.

III. Survey and Dataset

Between April 17 and May 10, 2020, exactly 7,324 respondents completed our questionnaire through the SurveyMonkey platform. We used an exponential non-discriminative chain-referral sampling method. Each author used social networks and word of mouth to recruit respondents, which in their turn used social networks and word of mouth to recruit other respondents. We selected this convenience sampling method to find respondents that meet certain criteria to participate in the survey (here wine consumers) and to ease data collection. Although this method is adequate given the urgency of the survey, it also generates a potential sampling bias that we hope to reduce through the large size of the sample. Table 1 details a sample structure that is relatively homogeneous across the four countries.Footnote 3

Table 1 Socio-Economic Characteristics of Respondents

Impression management (tendency to give favorable self-descriptions) often biases self-report data, questioning the validity of survey research (Rosenman, Tennekoon, and Hill, Reference Rosenman, Tennekoon and Hill2011), especially about alcohol consumption (Midanik, Reference Midanik1982; Stockwell, Zhao, and Macdonald, Reference Stockwell, Zhao and Macdonald2014). Because we cannot control this bias, readers should be aware of it but also assess its magnitude. Smith, Wesson, and Apter-Marsh (Reference Smith, Wesson and Apter-Marsh1984) examine this bias in alcohol consumption surveys in the United States by comparing self-reported data with actual sales. Their findings show a strong correlation (.84), especially because they survey adults who are free to participate or not in the study. More recently, Simon et al. (2015) and Karns-Wright et al. (Reference Karns-Wright, Dougherty, Hill-Kapturczak, Mathias and Roache2018) use transdermal alcohol monitoring to measure the validity of self-reported data on alcohol consumption with a correlation varying from .73 to .85. We, therefore, assume that although a bias may exist, its impact theoretically remains only moderate. The survey will not necessarily unveil information about over-consumption but rather in terms of under-consumption.

Our outcome variable concerns changes in individual wine consumption frequency through three modalities: less, as usual, more. For comparison and discussion of possible substitution effects, respondents were asked the same question about their consumption of beer and spirits. In line with our literature review, we explored five categories of individual characteristics that may have affected wine consumption behavior during the lockdown. In addition to respondent sociodemographic characteristics, we also include variables (detailed in the Online Appendix) describing these characteristics:

• Drinking habits. The nature and volume of alcohol usually consumed may influence respondents’ behavior during the lockdown. Three Likert scale variables (Pre-lockdown consumption) self-report the consumption of respondents for each beverage. We consider the possible bias of self-reported alcohol consumption.

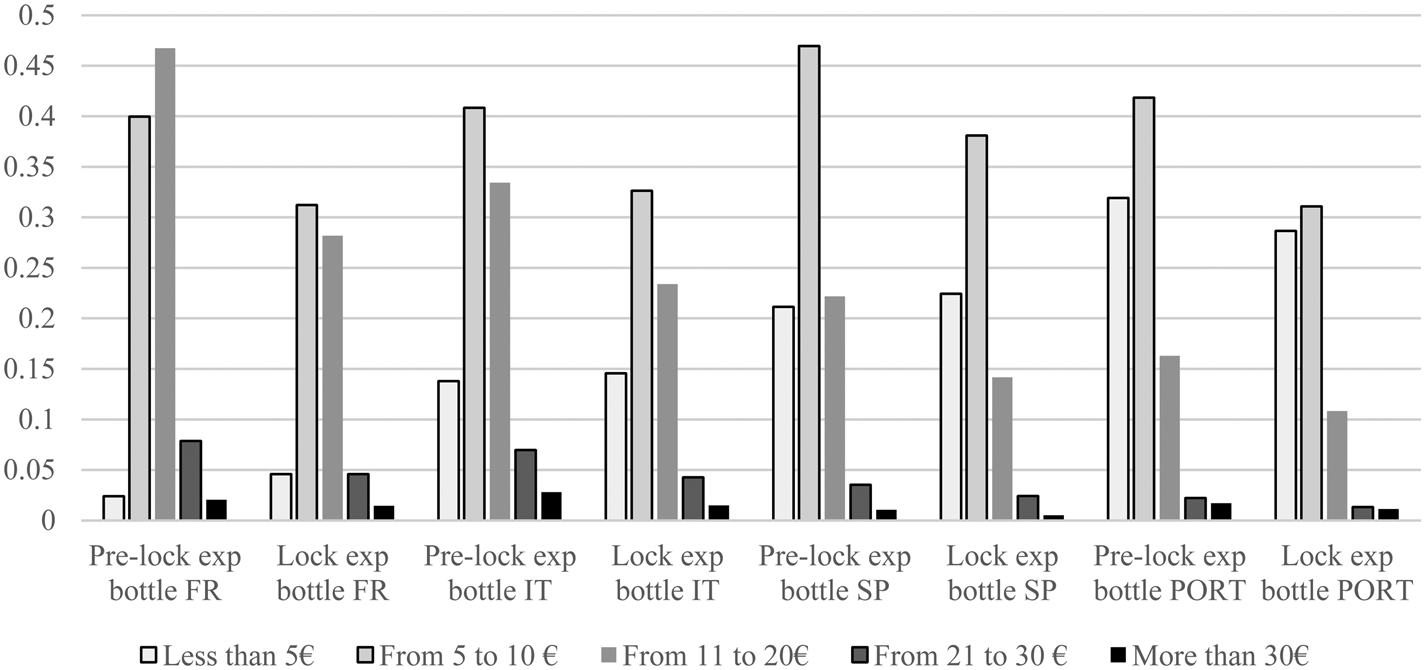

• Expenditure pattern before and during the lockdown. Two scale variables (Pre-lock exp bottle, Lock exp bottle) describe the respondents’ average expenditure in euros to get a bottle of wine before and during the lockdown. To better describe potential cross effects of expenditure among alcoholic beverages, we dispose of three dummies (Lock add exp) describing an additional average expenditure during the lockdown, respectively, for wine, beer, and spirits. Figure 1 indicates that average wine expenditures have been reduced during the lockdown. It may partly explain an increase in the quantities consumed but a decrease in quality consumed. These variables must therefore be considered in the explanation of volume consumption during the lockdown. The respondents who did not buy wine are not represented so that the sum of frequencies is not equal to 1. Figure 1 shows the differences in distribution between a pre-lockdown period and the lockdown period.

• Change in procurement patterns. The specific conditions during the lockdown influence alcohol availability to individuals. A vector of dummies indicates the use of different distribution channels by the respondents before (Pre-lockdown procurement) and during (Lockdown procurement) the lockdown. Figures 2a and 2b describe changes in procurement patterns by country. It appears that the lockdown greatly reduced the proportion of respondents purchasing their alcohol in wineries (particularly in France and Spain) and wine stores (particularly in Italy). Although declining, supermarkets remained the most frequent source, particularly in Italy and Spain. Drive-through supermarkets and online supplies certainly have increased, but less than expected depending on the country.Footnote 4 Consumption of wines held in cellars has dramatically increased, notably in France. These changes in procurement patterns, different in each country, may influence the outcome variable.

• Change in consumption situations. The lockdown has reduced the number of drinking occasions. A vector of dummies indicates the respondents’ consumption situations before (Pre-lockdown consumption) and during (Lockdown consumption) the lockdown. Figures 3a and 3b indicate the proportion of respondents for each situation by country. As expected, we note a dramatic reduction of opportunities to have a drink with friends and colleagues but a significant increase in self-consumption, notably in Portugal and Spain. Family consumption has also held up fairly well. Online consumption situations were far more frequent than before the lockdown, especially in France. Thus, the heterogeneity of consumption situations before and during the lockdown according to the country shows potential changes in wine consumption frequency during the lockdown.

• Motives of wine consumption. The lockdown has contributed to reducing certain motives (“conviviality”) but increased others (“relax,” “sleep,” and so on), resulting in changes in respondents’ consumption patterns. A vector of dummies (motive) describes the usual motivations of respondents. Figure 4 indicates a prominence of taste and food-pairing motivations and a very specific distribution by country, notably in France and Portugal.

• Insecurity regarding health (fear of virus) and wealth (fear of economic crisis). Relationships between stress and alcohol consumption have been discussed in the literature (e.g., Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Hatzenbuehler, Grant and Hasin2012). Insecurity feelings are self-reported on Likert scales. The heterogeneity of the reports (Figure 5) according to the respondents and their country of residence suggests differentiated effects on alcohol consumption frequency. Overall, the proportion distributions suggest that the Spanish were more afraid of the virus than of the economic crisis. The French were more afraid of the economic crisis than of the virus, whereas the Italians and especially the Portuguese feared both.

• Relational connectedness and self-centering. Loneliness is a well-known driver of alcohol consumption (e.g., Akerlind and Hörnquist, Reference Akerlind and Hörnquist1992). Its influence is assessed through a measure of “feeling of isolation,” referring to the psychometric loneliness scale (UCLA),Footnote 5 and by a measure of “feeling of refocusing on oneself” (reported on a five-point Likert scale). Figure 6 shows the distribution of each scale variable with very specific features depending on the country. Note that “feeling of isolation” is a reverted scale; strongly disagree means a high level of perceived loneliness, and strongly agree is a low level of perceived loneliness. “Feeling of refocusing on oneself” is a conventional scale that describes a more psychological than sociological isolation because we can refocus on ourselves even in a family or friendship context.

• Emerging positive initiatives. The lockdown is associated with a negative perception that may favor alcohol consumption. However, we add a scale variable (opportunity for initiatives) enabling respondents to express a vision in which this crisis has also a positive influence on a friendlier environmental and social society. Exploring this positivity also enables us to glimpse a happier drinking experience (drinking to enhance positive affect). Figure 7 indicates a general agreement among Latin European populations about an optimistic vision of the first lockdown.

Figure 1 Proportion of Wine Expenditure per Level (in euros) and by Country, Before and During the Lockdown, for One 75cl Bottle

Figure 2 Procurement Pattern Before (a) and After (b) the Lockdown (Proportion)

Figure 3 Consumption Situation Pattern Before (a) and During (b) the Lockdown (Proportion)

Figure 4 Alcohol Consumption by Motivation During the Lockdown (Proportion by Country)

Figure 5 Distribution of Respondents According to Their Feelings of Fear of the Virus and of the Economic Crisis by Country

Figure 6 Distribution of Respondents According to their Feeling of Isolation (Reverted Scale) and Their Feeling of Refocus on Oneself

Figure 7 From This Period Are Emerging Positive Initiatives

In the following analysis, we will not consider scale variables as continuous but discretized to better capture the specific distribution of respondents per degree (through a Likert scale). From this survey material, we can now address our research questions.

IV. Empirical Analysis

A. Changes in Wine Consumption During the Lockdown

To deal with our first research question, we consider the frequency of changes (less, as usual, more) in wine consumption and comparison with other alcoholic beverages. Figure 8 displays the observed frequency of changes in alcohol consumption by country and type of drink. The proportion of the respondents who have maintained or increased their wine consumption is significantly higher than the proportion of those who have decreased their consumption. And this phenomenon is all the more visible when compared to other alcohols. The answer to our first research question is, therefore, yes; respondents consume wine more frequently during the lockdown in both absolute terms and relative to other alcohol types (beer and spirits).

Figure 8 Proportion Distribution of Change in Alcohol Consumption During the Lockdown by Type of Beverage and Country of Residence

Figure 8 shows that this effect may be different according to the beverage and the country. To examine this intuitive observation, we explore the significant differences in drink consumption change by country (within) (Table 2) and as compared to other countries (between) (Table 3). Each table provides a chi-squared test to assess the equality of proportions (H0) considering the number of responses in each country (Table 2) and the number of respondents for each modality (Table 3). The rejection of the H0 hypothesis confirms significant differences. Below the chi-square test, we perform the Marascuilo procedure (Marascuilo and Serlin, Reference Marascuilo and Serlin1988) comparing all pairs of proportions, which helps to identify which proportions are responsible for the rejection of H0, as well as identifying the homogeneous group of proportions.

Table 2 Chi-square Test and Marascuilo Test of Proportions Equality of Beverage Changes by Country

Notes: Two non-significantly different proportions belong to the same group, identified by a single letter. Two significantly different proportions belong to two different groups, each identified by a specific letter (A, B, C, D, E, F).

Table 3 Chi-2 Test and Marascuilo Test of Proportions Equality of Countries per Beverage Change

Notes: Two non-significantly different proportions belong to the same group, identified by a single letter. Two significantly different proportions belong to two different groups, each identified by a specific letter (A, B, C, D, E, F).

On the one hand, the consumption frequency for all three types of drinks has been mostly stable over the whole sample as well as in every specific country. Wine consumption has been reduced the least, and spirit consumption the most. Most respondents have maintained their alcohol consumption frequency during the lockdown with no significant difference among alcoholic drinks.

On the other hand, we note that the increase in alcohol consumption frequency may be significantly different according to the beverage. Increased consumption frequency of spirits was significantly less common everywhere (except for living abroad respondents). Increased beer consumption was significantly more frequent than spirits (except in Portugal and for foreigners). Finally, wine consumption frequency has increased more than other alcoholic beverages in each of the countries.

Finally, the discussion of research question 1 is more ambiguous than suggested by Figure 8. First, more people maintained their consumption frequency of all alcoholic beverages during the lockdown compared to all other alternatives (“more” or “less”), except for the French and abroad respondents, for which the maintenance in wine consumption is not significantly different from all other alternatives. Second, more people increased their wine consumption as compared to beer and spirits.

Based on these findings, we investigate a possible heterogeneity of wine consumption patterns by country to answer our second research question. Table 3 examines whether the proportion of less, more, or as usual alternatives for each type of alcoholic drink is significantly different or not by country.

Wine consumption changes during the lockdown vary by country. French and respondents who live abroad from France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal had a significant and higher proportion of answering “more.” Portuguese respondents had a significant and lower proportion for answering “less.” The proportion of those who answered “as usual” is significantly different: we observe a very low frequency in France and a very high one in Portugal. These findings are not specific to wine and do not concern the same countries. These decreases in consumption amount reveal an initial heterogeneity of behavior by country. Our third question is more precise, questioning possible individual heterogeneity at the Latin European level and by country.

B. Individual Variables Affecting Changes in Wine Consumption Patterns

To the extent that we focus on the relationship between individual (i) characteristics (X i) and a latent variable ($y{\rm \ast }_i^w$![]() ) describing individual wine consumption in volume during the lockdown, we estimate an ordered logistic model.Footnote 6 The latent variable takes three values noted k (k = 1, 2, 3)

) describing individual wine consumption in volume during the lockdown, we estimate an ordered logistic model.Footnote 6 The latent variable takes three values noted k (k = 1, 2, 3)

where $\gamma _i^w$![]() is the threshold describing the previous individual wine consumption level. The probability distribution function is specified (F), the probability that $y_i^w = k$

is the threshold describing the previous individual wine consumption level. The probability distribution function is specified (F), the probability that $y_i^w = k$![]() is noted.

is noted.

We can then determine the parameters (β w) of this model by maximizing the likelihood function.

After testing different forms of probability distribution on all data, we retain a logit form for all estimates to facilitate the comparison. The likelihood function is then

Heteroskedasticity is controlled by using quasi-ML algorithms (Huber-White standard errors). The statistical impact of variables is based on the p-values. Due to their length, we fragment the results and their commentaries by category of variables (see Section III).

Each table presents the estimated coefficients of the ordered logit model and the marginal effects for each k value. Marginal effects are calculated at the means. For continuous variables, marginal effects indicate the change in the probability (Pr(y = k)) when the explanatory variable increases by one unit. For dummies, the marginal effect represents the change in probability (Pr(y = k)) when the variable changes from 0 to 1.

The following findings discuss our research questions 3 and 4 together, referring to Table 4 for the whole sample and Tables 5a to 5e for country samples (threshold values and predicted performance of each country model are included in Table 5e).

Table 4 Ordered Logit Estimates (ME: Marginal Effects; k = 1: less; k = 2: as usual; k = 3: more), All Data (n = 7,324)

Notes: *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 5a Status Effect (ME: Marginal Effects; k = 1: less; k = 2: as usual; k = 3: more)

Notes: *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 5b Expenditure Effects (ME: Marginal Effects; k = 1: less; k = 2: as usual; k = 3: more)

Notes: *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 5c Procurement Patterns’ Effects (ME: Marginal Effects; k = 1: less; k = 2: as usual; k =3: more)

Notes: *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 5d Drinking Habits and Substitution Effects (ME: Marginal Effects; k = 1: less; k = 2: as usual; k = 3: more)

Notes: *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 5e Consumption Situation and Motivation Effects (ME: Marginal Effects; k = 1: less; k = 2: as usual; k = 3: more)

Notes: *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

The overall sample reveals a significant effect of status variables on changes in wine consumption frequency during the lockdown for age and household size. All age categories are significantly correlated to an increase in wine consumption frequency, and the older the respondents, the lower the probability of reduced consumption. The age has different effects by country: in France, the categories of respondents between 18 and 29 and older than 51 years increase its probability of additional consumption, while it is the 30–40 years old segment for Italy and below 18 years old segment for Spain (no significant effect in Portugal). Concerning household size (number of children), a positive effect is significantly observed in France and Italy. Does this mean that the lockdown has increased the consumption frequency of older children who have returned home with their families? Or did the continuous and exhausting presence of young children encourage parents to drink more often in the evening? No doubt, a study of drinking motivations will tell us more about the effects of household size on alcohol consumption.

Gender has a significant negative effect on consumption, verified in Italy, where males consumed wine less often during the lockdown. We note that income levels do not have any significant effect on consumption in the whole sample. Only in France respondents with the lowest incomes increased their wine consumption.

Because wine price scales are different from one country to another, we focus our comments on variables describing the change in expenditure among the different types of alcoholic beverages. The variable lockdown additional expenditure is a dummy that takes the value 1 if the respondent has increased the average expenditure during the lockdown. In the whole sample, as well as in all subsamples, we note that an increase in wine expenditure is associated with maintenance or an increase in consumption frequency. Beyond what we learn from Figure 4, we may conclude that the lockdown has had a positive effect on both the volume of wine consumed and on quality (price) for a significant proportion of respondents. Results also reveal a significant cross-effect among alcoholic beverages. A substitution effect appears between wine and spirits to the extent that a higher expenditure in spirits decreases the frequency of wine consumption globally, and notably in France. Conversely, a complementary effect appears between wine and beer: a higher expenditure on beer increases the frequency of wine consumption in France.

We expected that purchasing habits, as well as the ability of consumers to adapt to the local lockdown conditions, could have a significant influence on consumption frequency.

First, we could expect that an autonomous wine supply (personal cellar) could encourage wine consumption during the lockdown. Throughout Latin Europe, the availability of a personal cellar is not significantly associated with wine consumption frequency. However, the estimates by country reveal different profiles. The influence of a personal cellar is significant only in Portugal. These results raise questions about purchasing behavior after the lockdown. Some households will certainly refill their depleted stocks, which might reinforce existing relationships with wine stores and wineries.

Second, we expected that disruption and overcrowding anxiety in common distribution channels (supermarket, grocery, wine stores) could contribute to reducing respondents’ wine consumption frequency during the lockdown. However, in the whole of Latin Europe, people using these distribution channels have not significantly changed their consumption patterns. Here, again, some differences appear depending on the country. Wine procurement in supermarkets and wine stores has not been sufficient to guarantee the stability of wine consumption frequency in Spain, perhaps because of a specific epidemiologic and psychological context (Rodriguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz, and Collado, Reference Rodríguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz and Collado2020).

Third, we anticipated that online and drive-through distribution channels would facilitate wine consumption during the lockdown. However, the findings are ambiguous. In the whole of Latin Europe, drive-through wine purchasing had no significant impact on wine consumption. It even hurt consumption frequency in Spain and Portugal. Further research is needed to explain these findings. Surprisingly, despite its development, online shopping did not contribute significantly to changes in wine consumption frequency across Latin Europe.

The strengthening of the relationship between consumers and wineries is an interesting fact to consider in the future. An additional question to our survey regarding the intention to purchase local wines after confinement sheds more light on this trend (Figure 9). All countries show high or very high intentions for replenishing with local supply, creating opportunities for local winemakers.

Figure 9 Since the Lockdown I Feel I Should Purchase More Local Wine

In terms of drinking habits, our results confirm the possible effects of the lockdown on greater alcohol consumption. Regular wine consumers were the least inclined to reduce their consumption frequency and were most prone to increasing it, particularly for the moderate among them (drinking wine at least once a week). Marginal effects by country all confirm this result.

Concerning substitution effects, beer or spirits drinking habits have had a significant negative effect on wine consumption during the lockdown. This result in the overall sample has been verified in all four countries. Complementary effects among alcoholic beverages can be detected in France, where a usual high consumption of spirits reduces the probability of consuming wine as frequently as before the lockdown. In Portugal, it significantly increases the probability of decreasing wine consumption during the lockdown.

During the lockdown, we have detected substitution effects among the types of alcoholic beverages. When beer drinkers increased their consumption, they limited the maintenance or increase of their consumption of wine. We observe certain loyalty of consumers toward their favorite drinks in the whole sample as well as in the country samples. To conclude, the lockdown induced a substitution effect among alcoholic beverages that could lead to significant modifications in market share in the future.

During the lockdown in Latin Europe, overall, most respondents reduced their consumption in all investigated situations except digital consumption. It is nevertheless interesting to note that the effects are of different amplitudes. Those who consumed wine alone or with family and colleagues before the lockdown were significantly more prone to decrease their wine consumption. Conversely, those who consumed with friends were significantly more prone to maintain or increase their wine consumption. However, these results are very partially confirmed in the subsamples by country, and only in Spain and France.

The influence of the type of consumption situation reveals a break in the relationship between consumption situation and consumption frequency during the lockdown. Consuming alone is associated with less frequent consumption globally, and especially in Portugal. The result shows possible negative correlations between isolation and maintenance or an increase in wine consumption frequency. A second interesting feature is a positive association in the whole sample between family consumption and a decrease in the frequency of consumption. Conversely, the whole sample shows a significant positive association between the habit of drinking among friends before the lockdown and the tendency to maintain or increase drinking frequency during the lockdown.

The lockdown has generated new contexts for wine consumption, such as digital happy hours. We expected this substitution with real social interactions to contribute to the maintenance or increase in consumption. However, the results are more complex. In the whole sample, digital gatherings reduced the alcohol drinking frequency compared to before the lockdown. This may be because respondents participating in virtual gatherings were younger than the average respondents, and they usually consume less wine than their older counterparts.

Conviviality and consumption for relaxation motives are positively correlated to maintenance or an increase of wine consumption frequency during the lockdown in the whole sample (verified in Italy and Spain for conviviality and in Portugal for relaxation). Conversely, motives of health and matching wine with foods are negatively correlated to maintenance or an increase of wine consumption frequency. The absence of correlation of consumption change with hedonic motives (taste, food, romance) and the study of motivations reveal a possible link between wine consumption frequency and anxiety. These results question a potential anxiety effect that the variables of loneliness and insecurity could better highlight.

Surprisingly feelings of isolation did not significantly explain any change in wine consumption in the whole sample. A low feeling of isolation has a significant impact in only two countries: in Spain, where it encourages the maintenance of wine consumption, and in France, where it encourages the decrease of wine consumption. According to the motivation results, we can suspect an impression management bias self-reported by respondents. The variable “feeling of refocusing on oneself” describes a more psychological than physical isolation and does not reveal any positive association between isolation and wine consumption. Conversely, this variable tends to reduce the probability of over-consumption overall, in each country, but in a decreasing (or less significant) way as the feeling of refocusing increases.

Table 5f Loneliness and Insecurity Feelings’ Effects (ME: Marginal Effects; k = 1: less; k = 2: as usual; k = 3: more)

Notes: *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Conversely to what was expected, fear of the virus did not significantly alter wine consumption in any country sample. The fear of an economic crisis is significantly associated with wine consumption frequency, but negatively. It decreases the proportion of people who have maintained or increased their wine consumption frequency during the lockdown. It also increases the number of those who have reduced their consumption frequency. Only in Portugal, the low fear of economic crisis is significantly correlated to maintenance or increase of wine consumption frequency.

To conclude, loneliness and insecurity feelings have not had any significant effect on wine consumption or were negatively associated with wine consumption (feeling of refocusing on oneself, less negative as the variable increases; fear of economic crisis). According to our results, the expected relationship between anxiety and an increase in alcohol consumption is undetermined. The motivation effect suggests that bias may affect the self-reported feeling perception. We note that the variable describing an optimistic perception of the lockdown is positively and significantly associated with an increase or maintenance of wine consumption frequency in the whole sample. However, findings by country specify these general results. In France and Italy, to disagree or strongly disagree with the idea that the lockdown might contribute to positive initiatives is significantly associated with increased wine consumption frequency. In this last finding only, we can observe a correlation between wine consumption and perceived anxiety.

V. Conclusion

This article documents how the first COVID-19 lockdown has affected the drinking behavior of wine consumers in France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Using a large online survey (n = 7,324 individuals), we analyze respondents’ purchasing and consumption patterns during that time. Our study examines wine consumption trends during the lockdown and its national and individual heterogeneity. Given the design of the survey and the methodological choices made in its treatment, several major results emerge.

Our first research question concerns the possible increase of wine consumption resulting from anxiety and the feeling of loneliness, as well as commercial and social disruption. The findings indicate that the proportion of people maintaining their wine consumption frequency during the lockdown has been significantly higher than all other alternatives (“more” or “less”). Additionally, when the lockdown contributed to increased alcohol consumption, wine was the most frequently consumed alcoholic beverage.

Our second research question explores the wine consumption heterogeneities across countries through the social and cultural specificities of wine consumption. Findings indicate that French and abroad respondents display an increase in wine consumption frequency that is not significantly different from the maintenance in wine consumption frequency. Portuguese respondents display significant maintenance of their wine consumption frequency.

Our third and fourth research questions explore the individual heterogeneity of behavior, respectively, for the whole sample and by country. Some key results with strategic implications for market players are worth highlighting. We have found substitution between alcoholic beverages everywhere. But we observe a loyalty of wine consumers to wine, and those who increased their consumption frequency also increased its quality. Average pre-lockdown consumption is positively associated with an increase in consumption frequency during the lockdown.

There have also been situational changes in the consumption of alcohol. The shift from personal meetings to online meetings has lowered the proportion of those who decrease their consumption frequency only in two countries. The vast majority of European respondents do not have the intention to continue digital gatherings after the lockdown. The supply structure has also changed.

Finally, the correlation between the context of anxiety (fear of the economic crisis, fear of the virus, feelings of loneliness, or refocusing on oneself) and wine consumption frequency increase was not significant, except partially in France. However, the significant influence of certain consumption motivations (relaxing, health), or low perception of the crisis as an opportunity for social and environmental changes, leaves doubt as to the impact of this anxiety-provoking context. This result suggests that we could have performed a better measurement of those perceptions. Sales data and sociological surveys will come within a few months to confirm or clarify some of our inferences. Undoubtedly, concerning the threshold values and predictive performance of our models, country-specific functional forms and better measurement of the variables will improve these results. Our reactivity in front of the surge of the COVID-19 crisis has come at this cost.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/jwe.2021.19.