Introduction

The physical structure of the habitat is an important factor that determines the quality and attractiveness of a territory (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Gray and Hurst2005). Habitats of higher structural complexity (i.e., greater availability of microhabitats and other resources) can support greater species richness (MacArthur & MacArthur 1961). This global pattern (Tews et al. Reference Tews, Brose, Grimm, Tielbörger, Wichmann, Schwager and Jeltsch2004) can be observed in a variety of organisms (e.g., marine invertebrates, Bracewell et al. Reference Bracewell, Clark and Johnston2018; lizards, birds, and small mammals, Scott et al. Reference Scott, Brown, Mahood, Denton, Silburn and Rakotondraparany2006; fish, Willis et al. Reference Willis, Winemiller and Lopez-Fernandez2005). Functional and phylogenetic diversity can also be strongly influenced by habitat type and structure (Klingbeil & Willig Reference Klingbeil and Willig2016, Sobral & Cianciaruso Reference Sobral and Cianciaruso2016, Stark et al. Reference Stark, Lehman, Crawford, Enquist and Blonder2017).

Habitat structure also influences the composition and diversity of the lizard assemblages (e.g., Garda et al. Reference Garda, Wiederhecker, Gainsbury, Costa, Pyron, Vieira, Werneck and Colli2013, Jellinek et al. Reference Jellinek, Driscoll and Kirkpatrick2004, Palmeirim et al. Reference Palmeirim, Farneda, Vieira and Peres2021, Pianka Reference Pianka1966). These organisms are important components of ecosystems in arid and tropical regions of the planet, where they present high taxonomic and functional diversity (Pianka et al. Reference Pianka, Vitt, Pelegrin, Fitzgerald and Winemiller2017, Ramm et al. Reference Ramm, Cantalapiedra, Wagner, Penner, Rödel and Müller2018, Vidan et al. Reference Vidan, Novosolov, Bauer, Herrera, Chirio, Nogueira, Doan, Lewin, Meirte, Nagy, Pincheira-Donoso, Tallowin, Torres-Carvajal, Uetz, Wagner, Wang, Belmaker and Meiri2019). Lizards act in different ecosystem processes, such as seed dispersal and insect population control, and serve as prey for other species (Cortês-Gomez et al. Reference Cortês-Gomez, Ruiz-Agudelo, Valencia-Aguilar and Ladle2015, Ortega-Olivencia et al. Reference Ortega-Olivencia, Rodríguez-Riaño, Pérez-Bote, López, Mayo, Valtueña and Navarro-Pérez2012, Valencia-Aguilar et al. Reference Valencia-Aguilar, Cortés-Gómez and Ruiz-Agudelo2013). Their evolutionary history is directly related to niche partitioning among the species that make up phylogenetically diverse assemblages distributed throughout the world (Vitt & Pianka Reference Vitt and Pianka2005).

The taxonomic diversity of lizard assemblages has been extensively studied in savannas worldwide (e.g., Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Feldman, Bauer, Belmaker, Broadley, Chirio, Itescu, Lebreton, Maza, Meirte, Nagy, Novosolov, Roll, Tallowin, Trape, Vidan and Meiri2016, Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009, Pianka Reference Pianka1973, Powney et al. Reference Powney, Grenyer, Orme, Owens and Meiri2010, Santos et al. Reference Santos, Oliveira and Tozetti2012, Vitt Reference Vitt1991). More recently, some of these studies have included analyses on the mechanisms that determine the functional diversity (e.g., Pianka et al. Reference Pianka, Vitt, Pelegrin, Fitzgerald and Winemiller2017, Ramm et al. Reference Ramm, Cantalapiedra, Wagner, Penner, Rödel and Müller2018, Skeels et al. Reference Skeels, Esquerré and Cardillo2019, Vidan et al. Reference Vidan, Novosolov, Bauer, Herrera, Chirio, Nogueira, Doan, Lewin, Meirte, Nagy, Pincheira-Donoso, Tallowin, Torres-Carvajal, Uetz, Wagner, Wang, Belmaker and Meiri2019) and phylogenetic diversity (e.g., Escoriza Reference Escoriza2018, Ramm et al. Reference Ramm, Cantalapiedra, Wagner, Penner, Rödel and Müller2018, Šmíd et al. Reference Šmíd, Sindaco, Shobrak, Busais, Tamar, Aghová, Simó-Riudalbas, Tarroso, Geniez, Crochet, Els, Burriel-Carranza, Tejero-Cicuéndez and Carranza2021) of these assemblages, some of them referring to lizards from Neotropical savannas (e.g., Gainsbury & Colli Reference Gainsbury and Colli2019, Fenker et al. Reference Fenker, Domingos, Tedeschi, Rosauer, Werneck, Colli, Ledo, Fonseca, Garda, Tucker, Sites, Breitman, Soares, Giugliano and Moritz2020, Lanna et al. Reference Lanna, Colli, Burbrink and Carstens2021).

The Cerrado corresponds to the largest savanna region in South America, covering about two million square kilometres and encompassing a mosaic of different types of open and forested vegetation (Ratter et al. Reference Ratter, Bridgewater and Ribeiro2003, Ribeiro & Walter Reference Ribeiro, Walter, Sano, Almeida and Ribeiro2008). This stratification favours the occurrence of species with different ecological characteristics (Colli et al. Reference Colli, Bastos, Araujo, Oliveira and Marquis2002, Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Valdujo and França2005, Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009), usually associated with specific types of habitats and microhabitats (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009, Vitt et al. Reference Vitt, Colli, Caldwell, Mesquita, Garda and França2007). The extensive contact of the Cerrado with other ecoregions (see Olson et al. Reference Olson, Dinerstein, Wikramanayake, Burgess, Powell, Underwood, D’Amico, Itoua, Strand, Morrison, Loucks, Allnutt, Ricketts, Kura, Lamoreux, Wettengel, Hedao and Kassem2001) also contributes to the taxonomic and ecological variation of the regional lizard fauna (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009, Vitt Reference Vitt1991), comprising at least 57 species (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009). Regional variation of lizard communities across the Cerrado has been little explored (but see Fenker et al. Reference Fenker, Domingos, Tedeschi, Rosauer, Werneck, Colli, Ledo, Fonseca, Garda, Tucker, Sites, Breitman, Soares, Giugliano and Moritz2020) and the use of different measures of diversity can provide more complete information about their structure.

The simplest and most frequently used descriptors to characterise biological communities are taxonomic (e.g., richness, composition, and species diversity; Magurran Reference Magurran2004, Morris et al. Reference Morris, Caruso, Buscot, Fischer, Hancock, Maier, Meiners, Müller, Obermaier, Prati, Socher, Sonnemann, Wäschke, Wubet, Wurst and Rillig2014), with species richness be the most practical and most objective measure. The inclusion of measurements of functional and phylogenetic diversity enables a complementary interpretation of the relationships between communities and the functioning of ecosystems (see Sobral & Cianciaruso Reference Sobral and Cianciaruso2016). Based on such measurements, one can evaluate how species affect specific ecosystem functions and how they respond to environmental variations (Cadotte et al. Reference Cadotte, Dinnage and Tilman2012, Hooper et al. Reference Hooper, Solan, Symstad, Gessner, Buchmann, Degrange, Grime, Hulot, Mermillod-Blondin, Roy, Spehn, Van Peer, Loreau, Naeem and Inchausti2002) and to habitat structure (e.g., Batalha et al. Reference Batalha, Cianciaruso and Motta-Junior2010, Berriozabal-Islas et al. Reference Berriozabal-Islas, Badillo-Saldaña, Ramírez-Bautista and Moreno2017, Sitters et al. Reference Sitters, York, Swan, Christie and Di Stefano2016).

In this study, we propose to analyse how structurally distinct environments influence different aspects of the taxonomic (species richness and composition), functional (diversity), and phylogenetic (richness and variability) structures of lizard assemblages at a site in the western portion of the Brazilian Cerrado, in contact with neighbouring ecoregions. Our general hypothesis is that these measurements are strongly influenced by structural differences between open and forested formations. We expect a distinct species composition in open and forested formations, mainly due to habitat specialisation (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009, Vitt et al. Reference Vitt, Colli, Caldwell, Mesquita, Garda and França2007). Because open formations are predominant throughout Cerrado (Klink et al. Reference Klink, Sato, Cordeiro and Ramos2020, Ratter et al. Reference Ratter, Ribeiro and Bridgewater1997) and present greater climatic stability over evolutionary time (Werneck et al. Reference Werneck, Nogueira, Colli, Sites and Costa2012) – which can favour the diversification of higher number of lizard species (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009, Reference Nogueira, Ribeiro, Costa and Colli2011) – we expect to find greater phylogenetic and species richness in these habitats. In contrast, we expect greater functional diversity in the assemblages from forested formations. The higher heterogeneity in such habitats (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Machado, Silva-Neto, Júnior, Medeiros, Gonzaga, Solórzano, Venturoli and Fagg2017, Pinheiro & Durigan Reference Pinheiro and Durigan2012) can enhance ecological niche partitioning between species (Bazzaz Reference Bazzaz1975), resulting in increased functional diversity among the lizards (Palmeirim et al. Reference Palmeirim, Farneda, Vieira and Peres2021, Peña-Joya et al. Reference Peña-Joya, Cupul-Magaña, Rodríguez-Zaragoza, Moreno and Téllez-López2020).

We also expect to find greater phylogenetic variability in forested formations, mainly due to the higher faunal interchange resulting from current and/or past connections of the Cerrado with surrounding forested phytogeographic units (namely, the Amazonia, the Atlantic Forest, and Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest; Antonelli et al. Reference Antonelli, Zizka, Carvalho, Scharn, Bacon, Silvestro and Condamine2018). Finally, we expect that lizard assemblages from open formations will be functionally and phylogenetically clustered, mainly due to the action of environmental filtering mechanisms on species (e.g. high temperatures, natural fires; Furley Reference Furley1999, Ratter et al. Reference Ratter, Ribeiro and Bridgewater1997).

Material and Methods

Study area

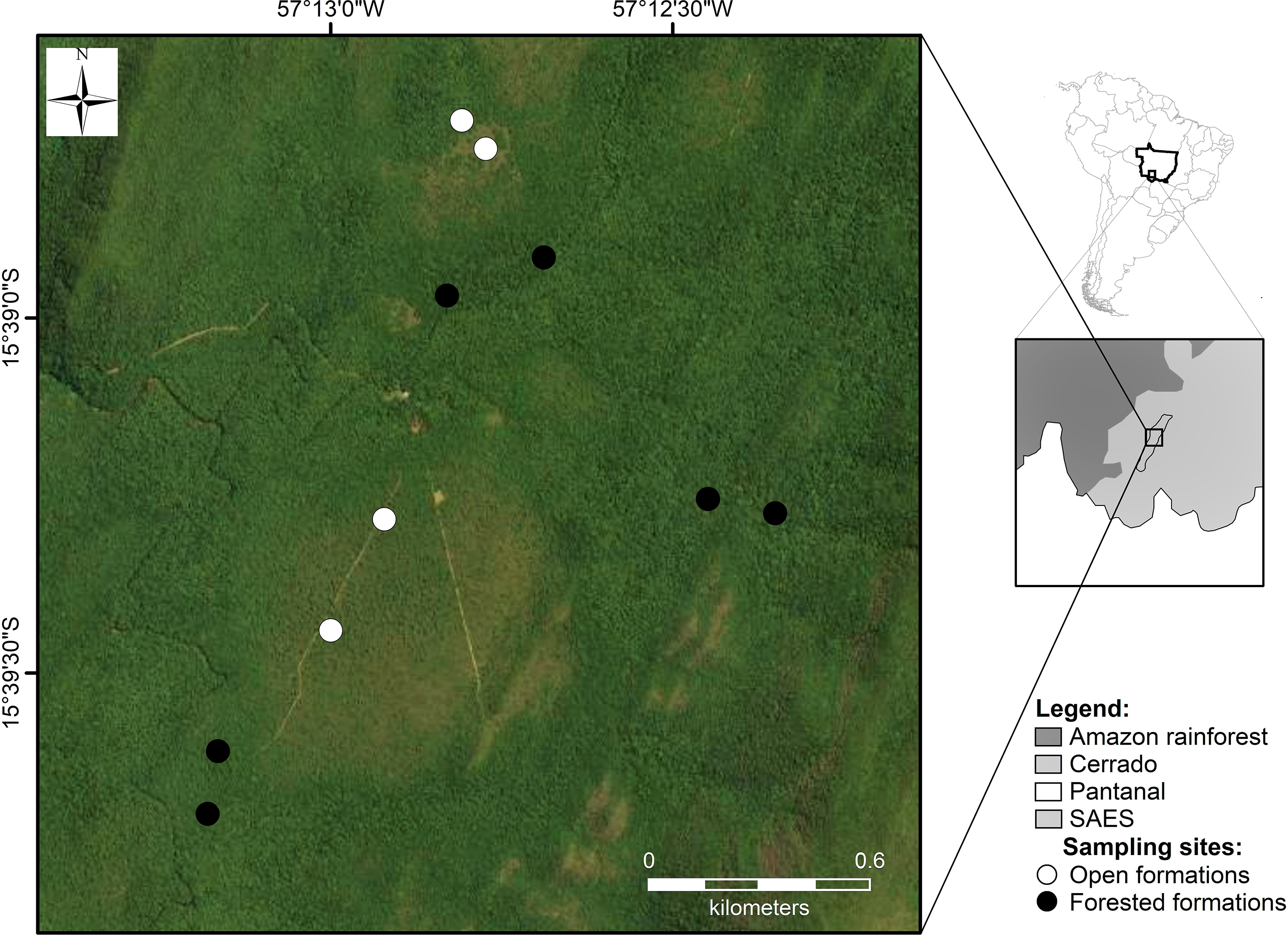

The study was carried out at the Serra das Araras Ecological Station (SAES), a federal conservation unit covering 28,700 hectares located in the southwest of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, in portions of the municipalities of Cáceres and Porto Estrela (15°33 – 57°03 N; 15°39 – 57°19 E; Figure 1). The station is situated in an area of transition between the western portions of the Cerrado and the southern Amazon rainforest, and local vegetation comprises a mosaic of vegetation types (Gonçalves & Gregorin Reference Gonçalves and Gregorin2004, Valadão Reference Valadão2012; see also Marques et al. Reference Marques, Marimon-Junior, Marimon, Matricardi, Mews and Colli2020).

Figure 1. Location of the study site at Serra das Araras Ecological Station (SAES), state of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

The region’s tropical climate is markedly seasonal, of the Aw type according to the Köppen classification (Álvares et al. Reference Álvares, Stape, Sentelhas, Gonçalves and Sparovek2013), with well-defined dry winter (from May to October) and rainy summer (November to April) (Ross Reference Ross1991). The average annual rainfall is 1265 mm and the minimum and maximum temperatures are 18ºC and 33ºC, respectively (Dallacort et al. Reference Dallacort, Neves and Nunes2015).

Lizard specimens were collected in five vegetation types – defined and characterised according to Ribeiro & Walter (Reference Ribeiro, Walter, Sano, Almeida and Ribeiro2008) – two of which are considered here as open formations (cerrado sensu stricto and cerrado parkland) and three considered forested formations (riparian forest, semi-deciduous dry forest, and cerrado woodland, known in Brazil as “cerradão”).

Among open formations, cerrado sensu stricto is a savanna physiognomy, characterised by the presence of small tortuous trees with irregular twisted branches (Ribeiro & Walter Reference Ribeiro, Walter, Sano, Almeida and Ribeiro2008). Termite mounds and piles of debris serve as shelters and spawning sites for lizards (Colli et al. Reference Colli, Bastos, Araujo, Oliveira and Marquis2002, Moreira et al. Reference Moreira, Lúcio, Silva and Jorge2009, Vitt et al. Reference Vitt, Colli, Caldwell, Mesquita, Garda and França2007). Cerrado parkland is characterised by the presence of sparse low trees, grouped on small land elevations, with 5% to 20% tree cover (Ribeiro & Walter Reference Ribeiro, Walter, Sano, Almeida and Ribeiro2008).

Among forested formations, riparian forest is composed of dense vegetation (with trees varying from 20 to 25 m in height), bordered by cerrado woodland or by semi-deciduous dry forest. The latter has an arboreal stratum varying between 15 and 30 m in height, which is fairly dense (approximately 90%) in the rainy season. During the dry season, with the fall of leaves of deciduous plant species, the tree cover drops to 50%. Cerrado woodland is a type of forested formation characterised by shrubby/herbaceous stratum with sparse grasses and a patchwork of plant species from the cerrado sensu stricto, semi-deciduous dry forest, and riparian forest. The trees vary from 8 to 15 m in height, providing conditions for luminosity.

Data collection

The data were collected between April 2009 and April 2010, and also in June and September 2010 at 10 sample points spaced at least 200 m apart and distributed among the five vegetation types (two sampling points in each vegetation type, totaling four sampling points in open formations and six in forested formations). At each sampling point, we installed sets of pitfall traps (Cechin & Martins Reference Cechin and Martins2000), each consisting of ten 60-liter plastic containers (buckets) buried and arranged in a straight line seven meters apart. The upper openings of the containers were interconnected by a drift fence made of plastic mosquito netting, partially buried (ca. 10 cm in the ground), the remaining part forming a barrier 0.5 m high. The containers were left open and checked daily, in the morning, for 4–9 consecutive days each month, making a total of 105 non-consecutive sampling days. When not in use, the containers remained covered. The total sampling effort was 7320 buckets day-1.

Functional traits

We used 14 functional traits to characterise the lizard species (Table 1; Appendix A), including continuous and categorical variables (Petchey & Gaston 2006). Some of the categories of traits in which these variables are included were previously used in studies on the functional diversity of lizards, such as snout-vent length (SVL), tail length (TL), body mass, habit, reproductive strategy, and type of foraging (Lanna et al. Reference Lanna, Colli, Burbrink and Carstens2021, Leavitt & Schalk Reference Leavitt and Schalk2018, Pelegrin et al. Reference Pelegrin, Winemiller, Vitt, Fitzgerald and Pianka2021, Pianka et al. Reference Pianka, Vitt, Pelegrin, Fitzgerald and Winemiller2017).

Table 1. Functional traits used in the quantification of functional diversity in lizard assemblages recorded in open and forested formations at a location in the Brazilian Cerrado.

Morphometric traits were measured only in adult individuals, using a digital caliper (0.5 mm precision). Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 g using spring scales. In the analyses, we used the average value of each morphometric trait.

As for the type of foraging, species that hunt visually and that capture moving prey were classified as sit-and-wait foragers (ambush predation). Species that actively hunt their prey or are able to distinguish them based on chemical senses were classified as active foragers (Vitt et al. Reference Vitt, Magnusson, Ávila-Pires and Lima2008). Those that can make use of both types of foraging were classified as mixed foraging species. Regarding microhabitat use, we classified the species as arboreal, cryptozoic (species found under leaf litter and upper soil layers; Greer & Shea 2004, Ibargüengoytía et al. 2004), terrestrial, or semiarboreal.

Because they are ectotherms, lizards are directly affected by thermal gradients (Pianka et al. Reference Pianka, Vitt, Pelegrin, Fitzgerald and Winemiller2017, Smith & Ballinger Reference Smith and Ballinger2001). Thus, the thermoregulatory behaviour of the species was also characterised, as follows: thermoregulators (or heliothermic – species that actively maintain body temperature within a restricted range of temperatures by basking in the sun, or by contact with warm surfaces; Pough & Gans Reference Pough, Gans, Gans and Pough1982) and thermoconformers (or non-heliothermic – species that do not actively thermoregulate, so their body temperature fluctuates according to the environmental temperature; Huey & Slatkin Reference Huey and Slatkin1976, Huey Reference Huey, Gans and Pough1982). We categorised thermoregulatory behaviour of each species based on our own field observations.

Data analysis

Species composition and richness were used to assess the taxonomic diversity of lizard assemblages. The Mantel test (with 1000 randomisations), relating the distance between the points to differences in species composition at each point, was used to determine the existence of spatial autocorrelations between sampling points. In addition, the significance of the results was tested considering a p-value of < 0.05. The geographical distance between sampling points did not affect the composition of lizard species (R-Mantel = 0.044; p = 0.335).

The variation of species composition between open and forested formations was analysed based on a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 1000 randomisations. This analysis describes space partitioning according to a measure of dissimilarity, with significance values obtained (p-values) by the permutation technique (Anderson Reference Anderson2017). We used Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) to visualise the dissimilarity in species composition. This analysis allows to position objects in a space with reduced dimensionality, while preserving their distance relationships (Legendre & Legendre Reference Legendre, Legendre, Legendre and Legendre2012).

Functional diversity was assessed using a matrix with functional traits, which was converted into a dissimilarity matrix using Gower’s distance measure (Pavoine et al. Reference Pavoine, Vallet, Dufour, Gachet and Daniel2009). The functional dendrogram was produced using the UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) clustering method. The values of functional diversity (FD) – the sum of the branches of the functional dendrogram (Petchey & Gaston Reference Petchey and Gaston2002) – were calculated using the “pd” function of the FD package (Laliberté & Legendre Reference Laliberté and Legendre2010). The FD index is generally influenced by species richness (Mouchet et al. Reference Mouchet, Villéger, Mason and Mouillot2010). To eliminate this influence, we used a null model (Gotelli Reference Gotelli2000). The null model maintains the species richness in each assemblage, but randomises the functional traits of these species (Schleuter et al. Reference Schleuter, Daufresne, Massol and Argillier2010, Swenson Reference Swenson2014).

Using the results of the null model, we calculated the standardised effect size (SES) of FD, using the SES.FD formula = (Meanobs- Meannull)/sdnull, where Meanobs is the observed value of FD, Meannull is the average generated after 999 randomisations over the null model, and sdnull is the standard deviation of 999 randomisations. The SES.FD formula enables one to compare the FD of communities, eliminating the bias associated with differences in species richness (Mouillot et al. Reference Mouillot, Albouy, Guilhaumon, Lasram, Coll, Devictor, Meynard, Pauly, Tomasini, Troussellier, Velez, Watson, Douzery and Mouquet2011, Swenson Reference Swenson2014). Positive values of SES.FD indicate functional overdispersion, while negative values indicate functional clustering (Sobral & Cianciaruso Reference Sobral and Cianciaruso2016).

The phylogenetic diversity of lizard assemblages at the Serra das Araras Ecological Station was analysed using a phylogenetic tree containing all the species sampled, extracted from Tonini et al. (Reference Tonini, Beard, Ferreira, Jetz and Pyron2016). The species Cercosaura parkeri (Ruibal, 1952) and Stenocercus sinesaccus Torres-Carvajal 2005 are not included in the Squamata phylogeny presented by these authors and were therefore replaced by Cercosaura schreibersii Wiegmann 1834 and Stenocercus caducus (Cope, 1862). Given that evolutionary changes generally occur in deep nodes (Mesquita et al. Reference Mesquita, Colli, Pantoja, Shepard, Vieira and Vitt2015), we assume that this substitution should not substantially affect the results. Differences in the phylogenetic diversity of assemblages were then calculated based on two indices: phylogenetic species variability (PSV) – which quantifies the variance in phylogenetic relationships between species in a community, and phylogenetic species richness (PSR) – a measure of species richness multiplied by PSV, to penalise strongly related species within the community (Helmus et al. Reference Helmus, Bland, Williams and Ives2007). Subsequently, differences in species richness, standardised functional diversity (SES.FD), PSR, and PSV between open and forested formations were analysed using Student’s t test for each of the measurements, after making sure the data met the normality requirements.

To analyse the functional structure and the presence of non-random patterns in the assemblages, we calculated three indices: functional diversity (FD) (Petchey & Gaston Reference Petchey and Gaston2002, 2006), mean pairwise distance (MPD), and mean nearest taxon distance (MNTD) (Webb Reference Webb2000, Webb et al. Reference Webb, Ackerly, Mcpeek and Donoghue2002). To evaluate the phylogenetic structure of the assemblages, we calculated three indices: phylogenetic diversity – PD (Faith Reference Faith1992), MPD, and MNTD. These latter ones are calculated using distance measures (Webb Reference Webb2000, Webb et al. Reference Webb, Ackerly, Mcpeek and Donoghue2002), allowing to quantify both the ecological and evolutionary distance between species (Pavoine & Bonsall Reference Pavoine and Bonsall2011). We analysed the significance of our results based on comparisons with a null distribution of the values generated by randomisation of the species in the traits matrix and in the phylogeny (10,000 times). For all indices, positive values and high quantiles (P > 0.95) indicate functional or phylogenetic overdispersion in assemblages, while negative values and low quantiles (P < 0.05) indicate functional or phylogenetic clustering. Communities that do not exhibit functional or phylogenetic structure possess random structure (Kraft et al. Reference Kraft, Cornwell, Webb and Ackerly2007).

The functional and phylogenetic parameters were calculated using the packages ape (Paradis et al. Reference Paradis, Claude and Strimmer2004), FD (Laliberté & Legendre Reference Laliberté and Legendre2010), picante (Kembel et al. Reference Kembel, Cowan, Helmus, Cornwell, Morlon, Ackerly, Blomberg and Webb2010), and SYNCSA (Debastiani & Pilar Reference Debastiani and Pillar2012). The other analyses were performed using the vegan package (Oksanen et al. Reference Oksanen, Blanchet, Friendly, Kindt, Legendre, Mcglinn, Minchin, O’hara, Simpson, Solymos, Henry, Szoecs and Wagner2018). All statistical analyses were performed in the R 3.6.0 programming environment (R Development Core Team 2019).

Results

A total of 292 lizards from 16 species and eight families were recorded (Table 2). The species accumulation curve stabilised after 18 days of sampling (Appendix B), with estimated richness (Jack 1– 16.99 ± 0.99) being similar to observed richness (n = 16), indicating that the effort sampling was satisfactory.

Table 2. Lizard species composition was sampled using pitfall traps with drift fences in open (CS – cerrado sensu stricto; CP – cerrado parkland) and forested formations (CW – cerrado woodland; DF – semi-deciduous dry forest; RF – riparian forest) in a location in the Brazilian Cerrado.

The species composition differed between open and forested formations (PERMANOVA: F = 28.595, p = 0.005). The first two axes of the PCoA explained 87.24% of total variability in species composition among habitats (Figure 2). The species richness was greater in the lizard assemblages from open formations (t = 4.338, df = 8, P = 0.002; Figure 3a), while the functional diversity was greater among lizards of forested formations (t = -4.652, df = 8, p = 0.001; Figure 3b).

Figure 2. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) graph of the composition of lizards in open (white dots) and forested (black dots) formations at a location in the Brazilian Cerrado.

Figure 3. Parameters of lizard diversity recorded in open and forested formations at a location in the Brazilian Cerrado: (a) species richness; (b) functional diversity; (c) phylogenetic variability; and (d) phylogenetic richness. The dark strip in the middle of each box plot represents the median; regions below and above it represent the first and third quartiles, and the bars below and above represent the minimum and maximum values, respectively.

The phylogenetic variability was greater among lizards of forested formations (t = -5.298, df = 8, p < 0.001; Figure 3c). However, the phylogenetic richness did not differ between assemblages (t = 1.698, df = 8, P = 0.127; Figure 3d). The lizard assemblages were functional and phylogenetically clustered in open formations (Table 3), but were randomly structured in the forested formations (Table 3).

Table 3. Values summarising the functional and phylogenetic structures of the lizard assemblages of the Serra das Araras Ecological Station, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Values of Z and P are based on 10,000 randomizations of the taxa in the functional dendrogram or phylogenies. Values in bold type indicate the presence of a significant functional or phylogenetic effect. Legends: Species Richness (SR), Functional Diversity (FD), Phylogenetic Diversity (PD), Mean Pairwise Distance (MPD), Mean Nearest Taxon Distance (MNTD).

Discussion

Our findings indicate distinct taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic patterns (except for phylogenetic richness) in the lizard assemblages from open and forested formations. Assemblages from open formations presented greater species richness, while assemblages from forested formations presented greater functional diversity and phylogenetic variability. Additionally, lizard assemblages from open formations were functionally and phylogenetically clustered. In other lizard assemblages studied around the world, the differences in patterns of taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic diversity were attributed, alternatively, to variations in habitat structure (Berriozabal-Islas et al. Reference Berriozabal-Islas, Badillo-Saldaña, Ramírez-Bautista and Moreno2017, Gainsbury & Colli Reference Gainsbury and Colli2019, Peña-Joya et al. Reference Peña-Joya, Cupul-Magaña, Rodríguez-Zaragoza, Moreno and Téllez-López2020), influence of environmental factors (Palmeirim et al. Reference Palmeirim, Farneda, Vieira and Peres2021, Pelegrin et al. Reference Pelegrin, Winemiller, Vitt, Fitzgerald and Pianka2021, Ramm et al. Reference Ramm, Cantalapiedra, Wagner, Penner, Rödel and Müller2018), and also historical and biogeographical processes (Escoriza Reference Escoriza2018, Fenker et al. Reference Fenker, Domingos, Tedeschi, Rosauer, Werneck, Colli, Ledo, Fonseca, Garda, Tucker, Sites, Breitman, Soares, Giugliano and Moritz2020).

The lizard assemblages from open and forested formations also differed in species composition. Many species of Cerrado lizards are associated with specific types of habitats and microhabitats (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009, Vitt et al. Reference Vitt, Colli, Caldwell, Mesquita, Garda and França2007), which leads to less overlap between the set of species of each of these environments. For example, Manciola guaporicola and Polychrus acutirostris were only found in the open formations (cerrado parkland and cerrado sensu stricto, respectively), while Copeoglossum nigropunctatum and Hoplocercus spinosus were restricted to the forested formations. Variations in species composition reflect the significant structural dissimilarity between these environments, which can therefore act as a dispersal barrier to some species (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009, Reference Nogueira, Colli, Costa, Machado, Diniz, Marinho-Filho, Machado and Cavalcanti2010).

The greater species richness found in the lizard assemblages from open formations corroborates previous studies on the same organisms in the Cerrado (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Valdujo and França2005, Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009). In this ecoregion, open formations occupy a much larger area than forested ones (Klink et al. Reference Klink, Sato, Cordeiro and Ramos2020, Ratter et al. Reference Ratter, Ribeiro and Bridgewater1997) and present greater climatic stability over evolutionary time (Werneck et al. Reference Werneck, Nogueira, Colli, Sites and Costa2012). These same factors probably contributed to the presence of many endemic species among the lizard fauna of the Cerrado’s open formations (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Ribeiro, Costa and Colli2011). Large-scale studies in deserts and savannas worldwide have also revealed high species richness (Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Feldman, Bauer, Belmaker, Broadley, Chirio, Itescu, Lebreton, Maza, Meirte, Nagy, Novosolov, Roll, Tallowin, Trape, Vidan and Meiri2016, Powney et al. Reference Powney, Grenyer, Orme, Owens and Meiri2010, Ramm et al. Reference Ramm, Cantalapiedra, Wagner, Penner, Rödel and Müller2018, Roll et al. Reference Roll, Feldman, Novosolov, Allison, Bauer, Bernard, Böhm, Castro-Herrera, Chirio, Collen, Colli, Dabool, Das, Doan, Grismer, Hoogmoed, Itescu, Kraus, Lebreton, Lewin, Martins, Maza, Meirte, Nagy, Nogueira, Pauwels, Pincheira-Donoso, Powney, Sindaco, Tallowin, Torres-Carvajal, Trape, Vidan, Uetz, Wagner, Wang, Orme, Grenyer and Meiri2017). The observed pattern for lizard species richness in these studies and in the present one might be related to both environmental (Powney et al. Reference Powney, Grenyer, Orme, Owens and Meiri2010, Šmíd et al. Reference Šmíd, Sindaco, Shobrak, Busais, Tamar, Aghová, Simó-Riudalbas, Tarroso, Geniez, Crochet, Els, Burriel-Carranza, Tejero-Cicuéndez and Carranza2021, Tejero-Cicuéndez et al. Reference Tejero-Cicuéndez, Tarroso, Carranza and Rabosky2022), spatial, historical, and biogeographical processes (Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Feldman, Bauer, Belmaker, Broadley, Chirio, Itescu, Lebreton, Maza, Meirte, Nagy, Novosolov, Roll, Tallowin, Trape, Vidan and Meiri2016, Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Ribeiro, Costa and Colli2011, Ramm et al. Reference Ramm, Cantalapiedra, Wagner, Penner, Rödel and Müller2018).

The greater functional diversity in the lizard assemblages from forested formations probably reflects the greater vegetation heterogeneity found in these habitats, in comparison with open formations (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Machado, Silva-Neto, Júnior, Medeiros, Gonzaga, Solórzano, Venturoli and Fagg2017, Pinheiro & Durigan Reference Pinheiro and Durigan2012). Heterogeneous habitats present a wide diversity of micro-habitats, and therefore allow diverse opportunities for niche partitioning (Bazzaz Reference Bazzaz1975, Londe et al. Reference Londe, Elmore, Davis, Fuhlendorf, Luttbeg and Hovick2020, MacArthur & MacArthur 1961; Šmíd et al. Reference Šmíd, Sindaco, Shobrak, Busais, Tamar, Aghová, Simó-Riudalbas, Tarroso, Geniez, Crochet, Els, Burriel-Carranza, Tejero-Cicuéndez and Carranza2021) and for diversification of species traits (Bergholz et al. Reference Bergholz, May, Giladi, Ristow, Ziv and Jeltsch2017, Chergui et al. Reference Chergui, Pleguezuelos, Fahd and Santos2020, Cursach et al. Reference Cursach, Rita, Gómez-Martínez, Cardona, Capó and Lázaro2020). A global study on the distribution of functional groups of lizards (Vidan et al. Reference Vidan, Novosolov, Bauer, Herrera, Chirio, Nogueira, Doan, Lewin, Meirte, Nagy, Pincheira-Donoso, Tallowin, Torres-Carvajal, Uetz, Wagner, Wang, Belmaker and Meiri2019), for example, demonstrated a high functional diversity in the Amazonia (a structurally heterogeneous region). Similarly, lizard functional diversity was found to be greater in the tropical semi-deciduous forest areas in western Mexico, when compared to more homogeneous habitats in the same region (Peña-Joya et al. Reference Peña-Joya, Cupul-Magaña, Rodríguez-Zaragoza, Moreno and Téllez-López2020).

The higher phylogenetic variability in the lizard assemblages from forested formations indicates that despite the lower species richness, the variability of lineages is greater than in assemblages from open formations. For different biological groups (e.g., plants, arthropods, and vertebrates), fossil records and analyses of species diversification rates have concurrently shown that tropical forests and their associated biological lineages are older than those found in the Cerrado savannas (Antonelli et al. Reference Antonelli, Zizka, Carvalho, Scharn, Bacon, Silvestro and Condamine2018, Azevedo et al. Reference Azevedo, Collevatti, Jaramillo, Strömberg, Guedes, Matos-Maraví, Bacon, Carillo, Faurby, Antonelli, Rull and Carnaval2020). Evidence for that also includes data for lizards (Lanna et al. Reference Lanna, Colli, Burbrink and Carstens2021, Sheu et al. Reference Sheu, Ribeiro-junior, Miguel, Guarino and Werneck2020). The Amazon region has a lizard fauna with one of the greatest values of phylogenetic diversity in the world (Gumbs et al. Reference Gumbs, Gray, Böhm, Hoffmann, Grenyer, Jetz, Meiri, Roll, Owen and Rosindell2020). The connection and faunal exchange between the Amazonia and Cerrado forested formations (Antonelli et al. Reference Antonelli, Zizka, Carvalho, Scharn, Bacon, Silvestro and Condamine2018, Ledo et al. Reference Ledo, Domingos, Giugliano, Sites, Werneck and Colli2020) probably also contributes to the greater phylogenetic variability found among lizards of these latter.

In spite of the marked differences in the species richness reported herein, lizard assemblages from open and forested formations presented similar values of phylogenetic richness. Previously, the equilibrium of phylogenetic diversity values between assemblages with lower and higher species richness was observed among Squamates from xeric habitats in the Arabian (Šmíd et al. Reference Šmíd, Sindaco, Shobrak, Busais, Tamar, Aghová, Simó-Riudalbas, Tarroso, Geniez, Crochet, Els, Burriel-Carranza, Tejero-Cicuéndez and Carranza2021). More recently, it was also observed among lizard assemblages from open and forested habitats studied in another region of the Brazilian savanna (Barros et al. Reference Barros, Dorado-Rodrigue and Strüssmann2022, in press). Together with our results, the above-mentioned studies reinforce that even spatially more restricted or fragmented habitats – such as the forested formations along the Cerrado – can be equally important to maintaining lizard evolutionary history in this primarily open ecoregion.

Both the functional and phylogenetic clustering found among lizards from open formations probably result from environmental filtering mechanisms acting on local species (Emerson & Gillespie Reference Emerson and Gillespie2008, Webb et al. Reference Webb, Ackerly, Mcpeek and Donoghue2002). High temperatures, low moisture, and sporadic wildfires, among other factors, are considered to be responsible for limiting the occupation of savanna landscapes by those lizard species less tolerant to environmental variations (Escoriza Reference Escoriza2018, Gainsbury & Colli Reference Gainsbury and Colli2019, Leavitt & Schalk Reference Leavitt and Schalk2018, Ramm et al. Reference Ramm, Cantalapiedra, Wagner, Penner, Rödel and Müller2018). The action of such environmental filtering mechanisms leads to a higher redundancy in species traits as observed here and in other lizard assemblages from xeric regions (Melville et al. Reference Melville, Harmon and Losos2006, Skeels et al. Reference Skeels, Esquerré and Cardillo2019), which can confer greater resistance and resilience against disturbances to these assemblages (Carmona et al. Reference Carmona, Tamme, Pärtel, De Bello, Brosse, Capdevila, González, González-Suárez, Salguero-Gómez, Vásquez-Valderrama and Toussaint2021, Maure et al. Reference Maure, Rodrigues, Alcântara, Adorno, Santos, Abreu, Tanaka, Gonçalves and Hasui2018).

By isolating particular lineages in the open formations (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Ribeiro, Costa and Colli2011), historical and biogeographical processes can also have contributed to the local functional and phylogenetic clustering, as observed among squamate reptiles from savanna enclaves within the Amazonia (Gainsbury & Colli Reference Gainsbury and Colli2003, Mesquita et al. Reference Mesquita, Colli, França and Vitt2006, Mesquita & Vitt 2007). Among the species we recorded in the open formations, 77% belong to the Gymnophthalmidae, Scincidae, and Teiidae families that make up the Autarchoglossa clade. Autarchoglossa lizards have been more successful in occupying open environments around the world (Vitt et al. Reference Vitt, Pianka, Cooper and Schwenk2003). In the Cerrado, they also dominate open formations, while species from Iguania and Gekkota clades are more diverse in forested formations (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009).

On a finer scale, our findings reveal that although open formations present greater species richness, the assemblages from forested formations present greater functional diversity and phylogenetic variability, a pattern that can be tested further and on a wider scale. The entire Cerrado has been under strong anthropic pressure, with massive habitat loss (Klink & Machado Reference Klink and Machado2005, Klink & Moreira Reference Klink, Moreira, Oliveira and Marquis2002, Strassburg et al. Reference Strassburg, Brooks, Feltran-Barbieri, Iribarrem, Crouzeilles, Loyola, Latawiec, Oliveira-Filho, Scaramuzza, Scarano, Soares-Filho and Balmford2017, Velazco et al. Reference Velazco, Villalobos, Galvão and De Marco-Júnior2019). Besides, some of the areas subject to higher deforestation rates along the ecoregion (De Mello et al. Reference De Mello, Machado and Nogueira2015) harbour higher levels of Squamate endemism, particularly in the south and southwestern Cerrado (Azevedo et al. Reference Azevedo, Valdujo and Nogueira2016, Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Ribeiro, Costa and Colli2011). Changes in the “Brazilian Forest Code” that reduce the extension of “Permanent Preservation Areas” (those aiming to protect areas environmentally significant to the maintenance of water resources, such as the riparian forests) – also put at risk the maintenance of several lizard species from these Cerrado habitats (Ledo & Colli Reference Ledo and Colli2016). All these factors can lead to the local extinction of species with unique functional traits (e.g., Batalha et al. Reference Batalha, Cianciaruso and Motta-Junior2010, Carmona et al. Reference Carmona, Tamme, Pärtel, De Bello, Brosse, Capdevila, González, González-Suárez, Salguero-Gómez, Vásquez-Valderrama and Toussaint2021, Mouillot et al. Reference Mouillot, Bellwood, Baraloto, Chave, Galzin, Harmelin-Vivien, Kulbicki, Lavergne, Lavorel, Mouquet, Paine, Renaud and Thuiller2013), thereby affecting ecosystem processes (Bogoni et al. Reference Bogoni, Peres and Ferraz2020, Carmona et al. Reference Carmona, Tamme, Pärtel, De Bello, Brosse, Capdevila, González, González-Suárez, Salguero-Gómez, Vásquez-Valderrama and Toussaint2021, Neghme et al. Reference Neghme, Santamaría and Calviño-Cancela2017).

Despite the robustness and relevance of our results, there is a possibility that sampling a greater number of habitats and localities along the Cerrado would lead to different results, based on the recognised faunal peculiarities and different biogeographical histories of local lizard assemblages (Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Ribeiro, Costa and Colli2011, Werneck & Colli Reference Werneck and Colli2006). Other limitations of our study include the sampling method considered. The richness reported herein for five vegetation types of the Serra das Araras Ecological Station – based on pitfall traps data only – represents 61% of the 26 species listed by Nogueira et al. (Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009), which employed additional sampling methodologies. These included active searches (which evidently allow to record a higher number of arboreal species) and historical records (some of them, for localities situated outside the limits of the ecological station; C. Nogueira, pers. comm.). Besides, the non-use of individual markings made it impossible to evaluate functional indices based on the variation in species abundance (e.g., functional evenness, divergence, and redundancy functional).

Previously, the influence of the mosaic of open and forested formations on the structure of Cerrado lizard assemblages has been evaluated based on parameters involving taxonomic diversity only (e.g., Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Colli and Martins2009, Reference Nogueira, Colli, Costa, Machado, Diniz, Marinho-Filho, Machado and Cavalcanti2010, Vitt et al. Reference Vitt, Colli, Caldwell, Mesquita, Garda and França2007). Our study was the first to reveal that this mosaic also determines the structure and both the functional and phylogenetic diversity of these assemblages. These results reinforce the importance of using different diversity indices to better understand the processes that shape biological communities.

Studies that use functional and phylogenetic metrics (instead of only taxonomic ones) allow the assessment of the effects of the physical structure of the habitat and the availability of climatic niches on the ecological functions and evolutionary history of biological communities. At different scales, these studies may provide a better understanding on how the loss of specific habitat elements can impact the maintenance of ecosystem functions and biodiversity in different regions of the Cerrado.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of vegetation mosaics in shaping the diversity patterns of lizard assemblages in the Brazilian Cerrado. The taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic descriptors of the evaluated lizard assemblages differed between the open and forested formations. The results suggest that these assemblages have been shaped by different processes, which have influenced not only the species richness and compositions, but also the diversity of ecological traits and lineages represented in each formation. These findings may assist in the establishment of future local conservation initiatives aimed at preserving not only a greater number of species, but also functionally and phylogenetically more diverse lizard assemblages.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many field assistants that helped us in the field, including André Pansonato, Derek Ito, Érika Rodrigues, Gisele Ferreira, Helder Faria, Karla Calcanhoto, Luciana Valério, Marina M.Santos, Miquéias Silva Jr., Tami Mott, Thais Almeida, and the staff from the Estação Ecológica Serra das Araras – Carolina Castro and Vanílio Marques; Felipe Curcio for allowing access to material under his care at the Coleção Zoológica de Vertebrados from the Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso; Leonardo Moreira for fruitful discussions; Beatrice Allain and John Karpinski for English translation.

Financial support

Data collecting was funded by the Programa Cognitus of the Instituto Internacional de Educação do Brasil—IEB and Conservação Internacional do Brasil—CI-Brasil (C.S., Chamada 001/2008). Further financial support was provided by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—CAPES and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Mato Grosso—FAPEMAT (R.A.B., 88882.167007/2018-01), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq (C.S., 3123038/2018-1).

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

The Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio-SISBIO n° 19518-1) provided collecting and research permits.