It was stormy outside. We had some big all black waves up over the boat, man! It was a hurricane. They wouldn't let us out on deck because it was too dangerous. We were so far down on the ship that our porthole was under water. And so Chano said, “Ah, Milt Shaw, throw the mutha’ fucker, throw 'em, throw 'em!” He wanted to throw him over board. . . . I said, “You can't do that, man, you know? Shit!”Footnote 1

This excerpt of an interview with bassist Al McKibbon describes his and Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo's difficult trip to Sweden as members of Dizzy Gillespie's bebop big band on board the S.S. Drottingholm in January 1948. As McKibbon and others have reported, bad weather and very rough seas marred the band's trip across the Atlantic and caused some musicians, including Pozo and McKibbon, to suffer from acute sea sickness.Footnote 2 Adding to the difficult travel conditions were their third-class cabins, which members of the band (led by drummer Kenny Clarke) accused tour manager Milt Shaw of booking in violation of the contract that stipulated first-class travel for the musicians.Footnote 3

McKibbon's story of crossing the Atlantic with an all-black bebop band, including a Cuban of African descent in “the bowels of the ship,” exemplifies the long history of geographical movements (forced and unforced) and cultural exchanges that Paul Gilroy and others have theorized as constituting the black or Afro-Atlantic.Footnote 4 Indeed, there are several reasons why Pozo's time with Gillespie in 1947 and 1948 compels us to situate the big band within an Afro-Atlantic analytical framework. One of these reasons was the language of the “Dark Continent,” that is, the discourse of Africa and black rhythm as primitive, savage, and social contagion.Footnote 5 Many commentators in the United States and Europe espoused this discourse in their descriptions of Pozo and his performances with Gillespie's band. Another reason was the actual music—known as cubop or Afro-Cuban jazz—that Pozo forged with Gillespie and members of the band. Jason Stanyek has credited their music with activating a “distinct lineage [in jazz] of Pan-African music making” and constituting “one of the germinal moments in the history of intercultural music making of the second half of the twentieth century.”Footnote 6 A third reason was the shared African cultural memory that these two musicians claimed, as exemplified in Pozo's statement and retold by Gillespie, that they “both speak African” in lieu of their inability to speak English and Spanish, respectively.Footnote 7 In fact, similar declarations of a shared African history linking black cultures of the New World lay at the crux of particular political, intellectual, and artistic initiatives in the United States during the 1940s.

This article situates Pozo and the Gillespie big band among American anthropologists and jazz historians and African anticolonialists and folkloric dancers who had been working in the United States since the 1930s with a view to promoting an accurate understanding of African culture and (what was commonly referred to then as) the New World Negro. These scholars, activists, and performers challenged longstanding stereotypes that validated the notion of black inferiority by recognizing the historical and cultural vibrancy of Africa and its connections to black Caribbean and African American cultures. For instance, the West African anticolonialist organization African Academy of Arts and Research (AAAR) sponsored many “forms of disseminating accurate information regarding the people of Africa” and their cultural inheritance in the New World.Footnote 8 One of the Academy's concerts, which took place in 1947 prior to Pozo's arrival in New York City, featured Gillespie accompanied by Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Nigerian percussionists performing music that some reporters described as “African bebop.”Footnote 9 Events such as this one begin to explain Gillespie's reasons for hiring Pozo and, most importantly, indicate that the music Gillespie and Pozo created was an expression of a broader and fervent movement to (1) define jazz as a modern African American art form with African and Caribbean roots and (2) transform the knowledge of Africa and its cultural inheritance in the New World.

Paul Berliner, Ingrid Monson, Peter Reinholdsson, and Robert Hodson provide important insight into jazz performance practice, particularly the significance of interaction among musicians in determining the production of the music.Footnote 10 In the same way, this article describes the ways in which Pozo interacted musically with other members of Gillespie's rhythm section, as well as with Gillespie and his arrangers in composing, arranging, and performing the music, and interprets Pozo's musical contributions and performances in dialogue with the ideological intentions of his fellow musicians, Gillespie's audiences, and jazz critics, as well as with those of African anticolonialists, African folkloric dancers, and anthropologists studying New World, Negro culture and history. Like the authors in Afro-Atlantic Dialogues: Anthropology in the Diaspora, I draw from M. M. Bakhtin's notions of heteroglossia (that which decentralizes the production of meaning) and dialogism (the interaction of meanings at the moment of an utterance of a word) to assess the discourses that determined the receptions of Pozo's music with the Gillespie big band and enabled Gillespie and his arrangers to exert their control over the production of his music in the first place.Footnote 11

In the eyes of Gillespie, Pozo was an authentic purveyor of African music via his knowledge of, and association with, the Abakuá, an all-male neo-African secret society of Cuba. Gillespie hired Pozo, therefore, to inscribe an African past into African American music. Pozo was indeed a proud keeper of Afro-Cuban culture and true to the Abakuá tradition of resisting colonialism, racism, and injustice, as he demonstrated, for example, in his reaction to Milt Shaw on the S.S. Drottingholm. Gillespie, along with manager Shaw, also considered Pozo a commercial draw to better promote the band in a jazz market whose disposition toward primitivist discourse was still strong in the late 1940s. Pozo, in turn, complied with Gillespie's and jazz audiences’ expectations, having appropriated Afro-Cuban music and dance in Havana to further his career as a popular composer and entertainer. Yet Gillespie and other members of his band considered some of Pozo's musical contributions too out of step with the harmonic and compositional complexities of modern jazz. Similarly, competing motivations and discourses of Pan-Africanism, anticolonialism, modernism, primitivism, and cultural progress problematized the attempts by anthropologists, jazz historians, and anticolonialists to construct a narrative of jazz history with African and Caribbean origins and redeem an African past for New World black culture, including jazz.

There is a lacuna of critical studies of Afro-Cuban jazz performance practice and history, particularly of its formative period during the emergence of bebop's popularity.Footnote 12 Instead, writers have tended to address Afro-Cuban jazz as part of a linearly conceived narrative of jazz history in the United States. Although we can understand Pozo's collaboration with Gillespie as a singularly significant moment in jazz history, this article explores how their music emerged in dialogue with contemporaneous political, academic, and artistic efforts to transform the discourses of Africa and jazz history. This article does not attempt to define Afro-Cuban jazz as a fixed musical style or genre. Rather, it approaches Pozo's musical contributions to the Gillespie big band as products of their negotiations of jazz and Afro-Cuban principles of performance, the ideological intentions and receptions of which intersected directly with those of related arenas of political, intellectual, and artistic activity and knowledge production in the 1940s.

Debunking the Myth

The period of the 1930s and 1940s was an extraordinary time in the intellectual, political, and artistic affirmation of Africa's importance to black cultures of the New World. In 1930 anthropologist Melville J. Herskovits published one of the earliest statements on the study of the New World Negro, in which he outlined the types of data available, to begin to address how African cultures persisted and interacted with the cultures of Europeans during slavery.Footnote 13 In this article Herskovits introduced the concepts of cultural retention, survival, and intensity as a way to study the process of acculturation among black populations in the New World.Footnote 14 In addition to his publications, Herskovits presented his research to nonacademic audiences in public speeches with the ultimate goal of debunking the myth of black inferiority in mainstream American society. He attributed the myth's persistence to the following normative beliefs: (1) blacks readily accepted and adjusted easily to slavery because of their childlike character, (2) only intellectually inferior Africans were enslaved, (3) blacks in the New World lost their original African ethnic identities, (4) blacks gave up their savage African customs in favor of the superior European customs of their masters, and (5) blacks are, thus, without a past.Footnote 15 Gillespie addressed these beliefs when he claimed to have realized only in 1945, after discussions with Kingsley O. Mbadiwe, the founder of the AAAR, that “white people didn't like the ‘spooks’ over here to get too close to the Africans. . . . It's strange how the white people tried to keep us separate from the Africans and from our heritage. That's why, today, you don't hear in our music, as much as you do in other parts of the world, African heritage, because they took our drum away from us.”Footnote 16

It is very likely that Mbadiwe, a graduate of Columbia University and New York University, as well as Gillespie, had read or heard about Herskovits's work. Jazz historians had also read the work of Herskovits and his German colleagues in comparative musicology, Erich von Hornbostel and Mieczyslaw Kolinski, who claimed to have found the scientific evidence to prove jazz's African origins and challenge the racist attitudes that many black and white Americans harbored toward jazz music. In Shining Trumpets (1946), Rudi Blesh wrote that “the misunderstanding of jazz is to be seen as part of the larger problem of the Negro in our society. And, as the understanding of African music clarifies that of jazz, so knowledge of the Negro character and his past clarifies and helps to solve the problem of the Negro in our democracy. Such a clarification is needed, not only among the whites, but among the many Negroes who have come to accept the myth.”Footnote 17 Blesh depended extensively on Kolinski's transcriptions and analysis of Herskovits's field recordings in Suriname and Dahomey (now Benin) to identify jazz Africanisms such as so-called “blue notes.”Footnote 18 He also quoted Hornbostel's influential, yet ill-conceived thesis of the incompatibility of European and African music to argue that jazz was essentially an African form of music.Footnote 19

Beginning in 1944, two years prior to the publication of Shining Trumpets, British film technician, writer, and novelist Ernest Borneman wrote a series of articles published in the jazz magazine Record Changer exploring the historical origins and social implications of jazz music.Footnote 20 Like Blesh, Borneman stressed the importance of Hornbostel's influence in his explanation of jazz's African origins. Following Herskovits, he also incorporated a broader hemispheric perspective by relating jazz and its musical antecedents in the United States to other Afro-Caribbean and South American folk music.Footnote 21

Meanwhile, African, African American, and Afro-Latin musicians and dancers in the United States worked regularly with academics and African anticolonialist activists who organized programs for white and black audiences that explored the interrelated histories of, and contemporary political and social issues facing, black populations of the Americas and Africa. For instance, for its fourteenth Festival of Music and Fine Arts, which took place in April 1943, Fisk University hosted a four-day program of seminars, concerts, dance recitals, film screenings, and art exhibitions featuring Latin American and African culture.Footnote 22 The seminars included papers on the impact of the West on contemporary African societies, race relations in South America, and the influence of African languages and music in the Americas. Asadata Dafora, a folkloric dancer and musician from Sierra Leone, and his Shologa Aloba Dance Group rounded out the festival with African folkloric dances and drumming, which included two choreographies titled “Primitive Conga” and “Rhumba.” Dafora claimed, in the program notes, that these Afro-Cuban dances had their origins in Africa, specifically Sierra Leone in the case of the “rhumba.”

Dafora's company gave a similar performance dramatizing the African origins of New World music, including jazz, at the USO Arena Auditorium in Norfolk, Virginia in December 1945.Footnote 23 Sponsored by Mbadiwe's AAAR, the program, titled “African Dances and Modern Rhythms,” strategically placed Dafora's performance of his “Festival at Battalakor” on the first part, titled “Africa”; dancers of Cuban and Brazilian music, Princess Orelia and Pedro, and calypso singer Duke of Iron, on the second part, titled “Western Hemisphere (the Caribbean)”; jazz and stride pianist Lucky Roberts on the fourth part, titled “Western Hemisphere (the United States)”; and the entire company on the “Finale.” (The third part featured speakers.) Dafora's “Festival at Battalakor” showcased African music and dance in the dramatization of a festival set in a West African village in the seventeenth century. Among the dances was “The Calinga” from which, the program claims, the Cuban “conga was derived.” The festival ends when slavers capture some of the participants who “mournfully [sing] nostalgic songs of their homeland as they are carried, in the galley of the slave ship, to unknown destinations and a fearful future.” Thus commences a performance suggesting the evolution of jazz (represented in the music of Lucky Roberts) beginning with Brazilian, Trinidadian, and Cuban music and dance.

One other program, mentioned earlier, was especially influential in Gillespie's decision to include Afro-Cuban percussion instruments in his big band: the AAAR's “African Interlude,” which took place on 7 May 1947 at the Hotel Diplomat in Midtown Manhattan. It featured combined performances by African American, African, Cuban, and Puerto Rican musicians and dancers, and consisted of two parts.Footnote 24 The African American weeklies The Pittsburgh Courier and People's Voice described the music of the first part as a “new type of ‘Be-bopping’ to African rhythms,” “African drum beats to modern jazz,” and “musical jazz to the rhythm of Cuban and African drums.” Gillespie and Nigerian drummer Norman Coker, who regularly accompanied Dafora's dance company, led the music. According to some reports, bebop musicians Charlie Parker and Max Roach joined percussionists Billy Álvarez, Pepe Becké, Diego Iborra, Eladio González, and Rafael Mora (Fig. 1). The second part featured the dancing of Asadata Dafora and members of his troupe, accompanied by Gillespie and Parker. During both parts of the program Saudia Gory narrated a poem titled “African Interlude” written by the African American playwright, poet, and author Owen Dodson.

Figure 1. Dizzy Gillespie and Cuban conga drummers, “African Interlude” program, Hotel Diplomat, New York City, New York Amsterdam News, 17 May 1947 (used by permission of the Amsterdam News).

Of this performance, Gillespie stated: “Charlie Parker and I found the connections between Afro-Cuban and African music and discovered the identity of our music with theirs. Those concerts should definitely have been recorded, because we had a ball, discovering our identity.”Footnote 25 An article on Gillespie in the October 1947 volume of Esquire Magazine states that he had “decided to bring three extra drummers to Harlem's Savoy Ballroom. Two of them played the little bongo drums and one the large congo [sic] drum. It was such a success Dizzy decided to use them with his orchestra on concert engagements.”Footnote 26 More than likely, it was Pozo who played the conga drum with Gillespie's big band at the Savoy Ballroom on 25 September 1947, four days before the band's Carnegie Hall concert, whose recordings include Pozo playing conga and Lorenzo Salan playing bongos.Footnote 27 Moreover, this article's reference to the conga drum as a “congo” drum signifies a significant act of semantic slippage. For, as we will see, writers, musicians, and others who commented on Pozo and his singing, dancing, and playing often did so in the language of the Dark Continent.

Jazz critics such as Rudi Blesh and Ernest Borneman and Dafora's dancers and drummers were not alone in disseminating this narrative of jazz's African origins. The African American historian Lawrence D. Reddick, in reviewing the performance of Gillespie's big band in Atlanta in November 1949, observed: “In terms of origin, Bop comes straight out of the popular music heritage of the New World. It is not too difficult to trace it back to its kinsman, Swing, and then to its grandfather, Dixieland, and from that to the Cuban and Haitian rhythms which everybody knows are direct descendants of that Old World Ancestor, the drum beats of West Africa.”Footnote 28 Reddick, a professor of history at the historically black Atlanta University beginning in 1947, had also been the curator of the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature (now known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture) in Harlem, and the chairman of the Board of Directors of the AAAR in the early and mid-1940s, during the time this organization was sponsoring Dafora's performances across the country.Footnote 29 Presumably, Mbadiwe and Dafora's mission, along with the work of Herskovits, Blesh, and Gillespie, had either convinced Reddick of (or reinforced his belief in) the African origins of jazz and the significance of African and Caribbean cultures to the history of African American culture.

These intersections in the discourse of the New World Negro and jazz's African origins remind us of J. Lorand Matory's argument that “African American cultures should not be considered integrated, internally systematic, and bounded in discrete units; they are crosscut . . . by multiple transnational languages, discourses, and dialogues.”Footnote 30 The political and ideological motivations behind these dialogues are also significant in our understanding of the complexities of these discursive intersections. For instance, throughout his stay in the United States, Mbadiwe was concerned first and foremost with the economic and political independence of Africa from European colonial rule. To bring about African independence, he believed that favorable projections of African music, dance, and drama would help to gain the political cooperation of the U.S. public, while also educating them (as he did with Gillespie) in the virtues of African cultures and their link to African American music and dance forms.Footnote 31 According to one report of the performance of Dafora's company in Norfolk, Mbadiwe said as much in his introductory remarks to the audience, stating that “the festival was intended to show the progress of African culture and is being presented periodically as a means of furthering good will between America and Africa.”Footnote 32 An earlier report, anticipating this performance, described Dafora's “Festival at Battalakor” as “[tracing] the evolution from African dances and music to modern rhythms.”Footnote 33 Earlier that year at the AAAR's second festival, which took place in Carnegie Hall, Mbadiwe described the aim of the program, “The March of African Music from Africa to the American Continents,” as showing the influence of African music and dance in U.S. jazz, swing, boogie-woogie, and tap dancing.

Upon his arrival in the United States in 1929, Dafora claimed to have “found a state of almost complete ignorance concerning African dancing and music.”Footnote 34 Mbadiwe similarly encountered indifference toward, and ignorance of, Africa among his fellow African American students at Lincoln University, attributing this ignorance to “adverse propaganda about Africa.”Footnote 35 As their work shows, Mbadiwe and Dafora presented themselves as keepers of the New World Negro's African past in order to refute the myth of black inferiority for political purposes. Yet the impact that Dafora's dance company had on audiences reinforced the very “adverse propaganda” and misinformation that Mbadiwe and Dafora (as well as Herskovits and Blesh) were trying to correct among both white and black audiences.

In his New York World Telegram review of the Dafora company's Carnegie Hall performance of April 1946,Footnote 36 Louis Biancolli drew from the language of the Dark Continent in describing the singing and drumming as “frenzied” and “black magic” and then shifted to a more journalistic tone when reporting that Eleanor Roosevelt, who was the chief sponsor of the AAAR, “praised its work and stressed its interracial value.” Reports published in the African American press also reverted at times to the language of the Dark Continent, as in Rubye Weaver Arnold's glowing review of the Dafora company's performance at the historically black college Clark University in Atlanta in January 1946. She described the effect of Norman Coker's drumming on the audience as “taking them to Africa with the weird torrid notes.”Footnote 37 Another report of the Dafora company's performance in Kansas City asserted: “Acclaimed with enthusiasm by Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt and other prominent Americans, Mr. Dafora's efforts to acquaint American Negroes with the culture of the land of their forefathers have been hailed in many quarters as of great significance and quite in line with the new nationalistic movement among Negroes in various parts of the country in which pride of race and achievement are being stressed with pointed emphasis.”Footnote 38 The signifying impact of these performances by, in the words of Jairo Moreno, “black Others” varied in accordance with the ideological implications that the sounds, bodily movements, dress, and settings had for African American audiences.Footnote 39

Like Mbadiwe and Dafora, Gillespie and Pozo assumed the role of unlocking the history of jazz's African past, thereby contesting the myth of black inferiority. Yet the beliefs that perpetuated the myth proved resilient. As we will see, some of Gillespie's musicians and African American audience members felt uneasy with the musical and social implications of Pozo's joining the band. After all, the musical repertory of this Cuban musician and dancer included the kinds of African chants, drum rhythms, movements, and garb that fascinated, embarrassed, and even frightened black and white audiences in the United States and Europe. Despite their shared intentions, Dafora's and Pozo's performances entered into a multiplicity of dialogical relationships with their audiences, as well as with the signifying histories of their words, movements, and appearances themselves, all of which often materialized in the discourses of cultural progress, primitivism, modernism, and the Dark Continent.

Entering an Arena of Intersecting Discourses: Chano Pozo from Havana to New York City

Luciano “Chano” Pozo González began to work as a professional musician in the late 1930s in Havana, performing in musical reviews in theaters. He quickly became successful in writing popular songs in the style of commercialized rumba. The most popular Cuban big bands at the time recorded his songs, including “Blen, Blen, Blen” (1939), “Parampampin” (1941), “Nagüe” (1942), and “El pin pin” (1946). Many of his songs were popular for his use of textual elements associated with the Abakuá of Cuba, a male initiation society based on several local variants of the Ékpè leopard society of West Africa's Cross River Basin.Footnote 40 For example, “Muna sanganfimba,” recorded by Orquesta Casino de la Playa in 1940, features Miguelito Valdés singing the Abakuá chant “Iyi bari-bari-bari-bari benkama,” which, according to Ivor Miller, is a “ritual phrase paying homage to the celestial bodies.”Footnote 41 Pozo, who was a member of the Abakuá lodge Muñánga Efó, sang this same chant in live versions of “Cubana bop” but not for the studio version, which the Gillespie big band recorded in December 1947.Footnote 42 While writing songs for, and playing percussion on occasion with, all-white Cuban jazz bands, Pozo also performed with comparsas (neighborhood carnival associations) including Los Dandys de Belén in the early 1940s. He also became a featured performer on the Cuban radio station RHC Cadena Azul beginning in 1940.

Pozo traversed various kinds of boundaries during his career in Havana. He actively performed with professional bands in nightclubs, as well as with neighborhood comparsas. Dance choreographers, theater producers, and radio programmers featured him as a performer of authentic Afro-Cuban dance and drumming. Furthermore, he was a commercially successful composer of Cuban popular songs, many of which were also recorded by Latin big bands in New York City. In fact, Pozo's popularity as a composer and entertainer had been established in the U.S. press at least five years before his arrival. In 1942 the Los Angeles Times reported that the Latin American musical revue See, See, Senorita was scheduled to play at the Lobero Theater in Santa Barbara, California.Footnote 43 His “Muna sanganfimba,” which the article described as the “current Afro-Cubano sensation by Havana composer Luciano Pozo,” was among the featured musical numbers.

Two years later Variety published an article by Edward Perkins, who reported from Havana on Pozo's growing popularity, crediting him as the creator of the “amazing new trend of original Afro-Cuban music that is sweeping this republic via radio, night clubs and records, and will soon have potent effect in the United States, Mexico and throughout Latin America.”Footnote 44 Perkins described Pozo as a “champion of authentic Cuban music,” identified “Muna Sanganfimba” as the song that initiated his popularity, and reported that Pozo's nightly thirty-minute radio program on Cadena Azul was the “top audience-getter.” Perkins concluded his article with the following observation: “The late Jim Europe, the real originator of jazz, predicted that, because of its pure melody and hot rhythm, Afro-Cuban music would some day spread throughout the world. . . . Chano Pozo is the answer to those hunches.” One month later Harold Preece quoted much of the content of Perkins's article in the New Journal and Guide, introducing Pozo to readers of this African American newspaper published in Virginia.Footnote 45 In offering a variation of Perkins's concluding remark, Preece added the following rather remarkable prediction: “The old masters of jazz and boogie-woogie will pretty soon be improving upon Chano Pozo who is the Duke Ellington of Cuba.” In fact, it would be the young innovators of bebop (and not the old masters of jazz)—Gillespie and his arrangers—who would aim to “improve” Pozo's compositions beginning in December 1947.

Like many of his fellow Cuban musicians before him, Pozo eventually moved to New York City to further his career as a musician, composer, and entertainer. Most sources claim that he arrived in New York in February 1947.Footnote 46 Based on extant documentation, however, it is more likely that Pozo arrived later that year in June. First, records from the American Federation of Musicians, Local 802 (New York City) indicate that Pozo first applied for union membership on 12 June.Footnote 47 Second, Pozo's name began to appear in advertisements published in La Prensa, New York's primary Spanish-language newspaper, on 20 June. These dates coincide with the arrival in New York of Arsenio Rodríguez, with whom Pozo recorded eight sides for the independent record company Coda Records.Footnote 48 In the following weeks he performed regularly on variety shows in local theaters catering to Latino audiences in East Harlem and the South Bronx and in Midtown nightclubs for mostly non-Latino audiences.

Advertisements and reviews of these shows indicate that Pozo performed típico (traditional) Afro-Cuban music as a featured singer, conga player, and dancer. Apparently, he did not join a Latin band as a regular member. He was first featured on a variety program titled “Revista de las Antillas” (“Antillean Revue”) headlined by Cuban singer Miguelito Valdés that ran at the Teatro Triboro on 125th Street near Third Avenue from 20 to 26 June.Footnote 49 Also on the program was Cuban singer Olga Guillot, who was billed as the “Cuban Lena Horne.” Pozo was also featured along with Olga Guillot at the Belmont Theater on 48th Street in Times Square from 19 to 24 July.Footnote 50 The program included the film musical Bambú, which featured Cuban musical acts set in Santiago de Cuba.Footnote 51 The Belmont Theater invited Pozo back to perform Afro-Cuban dances with his partner and girlfriend Cacha on the following week's program from 25 to 31 July (Fig. 2).Footnote 52

Figure 2. Advertisement for the film Bambú and stage acts Chano Pozo and Cacha, Belmont Theater, New York City, La Prensa, 26 July 1947 (used by permission of EI Diario New York).

Between these two engagements Pozo more than likely performed with other musicians and entertainers on shows that were either not advertised or did not originally include him. He also performed for the Cuban social club Club Cubano Inter-Americano, whose headquarters were located in the South Bronx. On 9 July he participated in the Club Cubano Inter-Americano's program honoring the fathers of Cuban independence José Martí and Antonio Maceo. In addition to Pozo, the program featured Cuban and Puerto Rican artists living in New York City, including Olga Guillot, Willie Capo, Miguelito Valdés, and Marcelino Guerra.Footnote 53

During this time Gillespie's big band performed at the Apollo in Harlem from 20 to 26 June, Downbeat in Manhattan from 10 July to 28 August, White City Palace in Chicago on 31 August, and Summer Theatre in Brooklyn from 7 to 9 September.Footnote 54 In addition to performing with his band and on the “African Interlude” program with Cuban percussionists in May cited above, Metronome reported in July that Gillespie had sat in with the Noro Morales orchestra, one of the most popular Latin bands at the time, at the Havana-Madrid nightclub in Midtown Manhattan.Footnote 55

By September Gillespie's interest in incorporating a Cuban percussionist into the big band had peaked. He invited Pozo to rehearse with the band after consulting with his Cuban friend and former swing band member Mario Bauzá.Footnote 56 Besides his aim to re-Africanize jazz music, Gillespie had commercial motives for having a seasoned musician and stage performer join the band. As Alyn Shipton shows, Gillespie and manager Shaw had invited Ella Fitzgerald to perform with the band in 1946 and 1947 to help increase ticket sales.Footnote 57 According to baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne, Gillespie hired Pozo because “they kept saying we needed something more commercial.”Footnote 58 McKibbon added that Gillespie “wanted something that he could feature in the band. So he got together with Mario Bauzá and Mario told him, ‘I've got a guy for you. He just came [from Cuba].’”Footnote 59 Evidently, Shaw and Gillespie hired Pozo to help fill the commercial void left by Fitzgerald's departure.

Pozo had already addressed Africa's heritage in Cuban culture as a popular composer and entertainer in Havana, but the African-derived religious and musical practices in which he had immersed himself had been the subject of much debate among Cuban political authorities, anthropologists, intellectuals, composers, poets, and others. This debate considered street comparsas, congas, and the cultural practices of the Abakuá and other Afro-Cuban groups as either the embodiment of a cultural mestizaje (miscegenation) that had overcome the original African and Spanish strains of Cuba's cultural and biological body politic, or as the atavistic practices of the slave era that capitalism and imperialism perpetuated to keep black Cubans from attaining their political, economic, and cultural destiny.Footnote 60

In contrast to these assimilationist and Marxist perspectives, Pozo and other black Cuban musicians such as Arsenio Rodríguez held an Afro-centric perspective in which they drew upon ancestral practices of Cuba's African heritage to address contemporary questions of race and cultural identity. Ivor Miller has shown that much of Cuban popular music recorded from the 1920s until the present reveals Abakuá influences musically and lyrically.Footnote 61 He argues that since the founding of the first lodge in 1836 in Cuba, the Abakuá, who are also referred to pejoratively as ñañigo, have represented a rebellious, even anticolonial, segment of Cuban society. Because of this history, Abakuá musicians, including Pozo, have sung about their ongoing contributions to Cuban history and culture, their liberation struggles, and race relations. Pozo continued this work with Gillespie in an attempt to debunk the myth of black inferiority in U.S. society.

For many African American jazz musicians, however, the music and cultural traditions of their black Cuban counterparts embodied, if not the practices of a black Other, then the African past of their modern musical present. As Jairo Moreno argues, Pozo was “regarded as a repository of directly transmitted knowledge and as a living musical archive holding ancestral memories lost to black North Americans.”Footnote 62 Indeed, Gillespie valued Pozo as a direct link to African music itself: “Chano wasn't a writer, but stone African. He knew rhythm—rhythm from Africa.”Footnote 63 Such a proposition, as we will see, was open to various interpretations, including its sublimation within aesthetic, ideological, and commercial imperatives.

The Rhythmic Dialogism of Swing and Clave

The following musical analysis focuses on the playing of Pozo and his fellow rhythm section players as heard on extant studio and live recordings of the Gillespie big band dating from September 1947 through October 1948. What these recordings reveal, particularly in multiple versions of the same pieces, is sonic evidence of Pozo, bassists Al McKibbon and Nelson Boyd, drummers Joe Harris, Kenny Clarke, and Teddy Stewart, and pianists John Lewis and James Foreman adopting and adapting principles of Cuban son and jazz music in response to each other's playing. This analysis builds on the approaches established by African and jazz music scholars to understand processes fundamental to the successful interplay between musicians in jazz and other Afro-Atlantic musics.Footnote 64 As Paul Berliner has shown, “striking a groove” is a fundamental goal of jazz musicians, the achievement of which “requires the negotiation of a shared sense of the beat.”Footnote 65 As I have shown in my work on the Cuban musician Arsenio Rodríguez, the rhythmic texture or groove of the son montuno style is similarly built on a collective sense of the clave beat or time-line.Footnote 66

Despite the importance of collective rhythmic playing in Afro-Atlantic musics, actual rhythmic patterns and the ways musicians deploy them in their playing fundamentally differentiate these repertories. Hence, according to several sources, Pozo's playing in the Gillespie band challenged the musicians, particularly those in the rhythm section, in new ways to reach and maintain a shared sense of the beat, whether that beat was based on a swing or clave groove. What is more, Pozo's compositional contributions, rooted in Afro-Cuban musical aesthetics, evoked a variety of sentiments in Gillespie's arrangers, from an almost trivializing apprehension in Walter Fuller to a musical and spiritual ecumenicism in George Russell. Ultimately, their musical negotiations, ideological rationalizations, and commercial motivations reveal the power inequities that in the end shaped the dynamics of Gillespie's and Pozo's Afro-Atlantic project.

Pozo's first recorded performance with the Gillespie big band took place on 29 September 1947 at Carnegie Hall. The rhythm section consisted of John Lewis (piano), Al McKibbon (bass), Joe Harris (drums), Chano Pozo (conga), and Lorenzo Galan (bongo). When Pozo joined the band, McKibbon became concerned with the clash between the conga's son tumbao (rhythmic pattern) and their underlying “swing” rhythmic structure. As he explains:

I was against it originally because the conga drum makes a different accent than the one we're accustomed to in swing music, you know? His accent is on four-and [sings conga pattern 1 (see Example 1)]. So I thought that would interfere. So Dizzy said, “Nah, nah, it's going to be alright, man. Don't worry about it. Don't you worry.” So he brought Chano in, and in the beginning it was strange 'cause it just was something I hadn't heard. But when we started to play things with a Latin flavor, wow! Some kind of magic happened there, man.Footnote 67

Cuban musician Mario Bauzá similarly noted that Pozo's “conga used to interrupt them, you know, until they found the right kind of approach.”Footnote 68

Example 1. Conga patterns.

Although the rhythm section does indeed strike effective grooves in the “Latin-flavored” pieces “Algo bueno” (originally “Woody ‘n’ You”) and “Manteca,” two conga patterns labeled 1 and 4 in Example 1 did clash with the swing rhythmic and melodic structure of other pieces. This clash is evident in the first sixteen bars of the first chorus of “Good Bait,” arranged by Tadd Dameron and recorded in the studio on 30 December 1947. Here Pozo's two open-tones on beat 4 (pattern 1, measures 3, 4, and 7) and his left hand's underlying “straight” eighth-note attacks (indicated with slashed notes) clash with the swing rhythm marked by the triplet eighth-note phrasing on beats 2 and 4 of Kenny Clarke's high-hat, the similarly phrased melody played by the saxophones, and McKibbon's walking bass line (Example 2).

Example 2. “Good Bait” (William Count Basie and Tadd Dameron), recorded 30 December 1947 by Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra, first chorus. (Used by permission of Alfred Music Co., Inc.)

In the remaining choruses, however, Pozo generally avoids this pattern by playing one open-tone attack on either beat 4 or the following eighth note (henceforth “and-of-4”) (patterns 2 and 3) and softening the left hand's straight eighth-note hand pattern on the drum head. As a result, Pozo emphasizes the backbeat by playing a slap on beat 2 and an open tone on beat 4 or the and-of-4, which contribute more successfully to the shared swing groove. Although it is difficult to determine why Pozo changed his playing after the first chorus in this recording, Gillespie on more than one occasion had to instruct Pozo to change his pattern:

There was one number that we played called “Good Bait” that he [Pozo] understood perfectly. So whenever he got on that wrong beat, I'd go over and whisper in his ear, “da-da, da-da-da” [2–3 clave]. He'd change immediately, because if you're doing boom-boom, and you're supposed to be doing bap on a boom-boom, that's just like beeping when you should have bopped.Footnote 69

Included in Example 2 is the 2–3 clave beat even though it is not actualized on the recording, but it helped Pozo, as Gillespie suggests, in finding the correct beat to execute a slap (“bap”). Based on Gillespie's explanation, Pozo apparently confused beats 2 and 4, the latter of which called for two opened-tone eighth notes (“boom-boom”).

Three recorded versions of “Relaxin’ at Camarillo” further demonstrate the musical choices and changes Pozo made to best contribute to the rhythm section's groove and help accentuate the effects of George Russell's arrangement.Footnote 70 Charlie Parker composed the piece as a standard twelve-bar blues and recorded it on 26 February 1947 with a septet (Charlie Parker's New Stars).Footnote 71 Russell, however, radically transformed the structure and harmonic language of the piece by alternating newly composed polymetric and polytonal sections (based on his Lydian Chromatic Concept) with repeated cycles of the piece's original twelve-bar blues head. In the first recorded version from the band's Carnegie Hall concert, Pozo utilizes pattern 2 for the newly composed sections, and both Galan (bongo) and Pozo drop out in the swing sections. In the A sections the quadruple-metered patterns of the conga (pattern 2), bongo (martillo or “hammer” pattern), and piano (alternating C and B-flat major chords in half notes) join with the triple-metered bass ostinato (doubled by the baritone saxophone) and drum pattern to create a densely rich polymetric and rhythmic texture. For the swing sections, however, we can assume that Gillespie and others in the band still harbored apprehension over Pozo's conga pattern clashing with McKibbon's walking bass line and Joe Harris's swing pattern on the cymbal.

The second recorded performance of “Relaxin’ at Camarillo” is from the band's concert at Cornell University on 18 October 1947. In contrast to his playing less than one month earlier, Pozo executes the tango-congo pattern (pattern 4) throughout the entire arrangement and, in effect, disregards the contrasting rhythmic grooves and moods of the arrangement's sections. Although this pattern does lock in with the other rhythm section's patterns in the A sections, its clash with the swing rhythmic framework of sections B and C is particularly noticeable. By the band's performance of “Relaxin’ at Camarillo” on 2 October 1948 at the Royal Roost nightclub in New York City, Pozo had settled on utilizing pattern 2 for sections A, B, and C, while reserving pattern 1 for the orchestral build-up and coda.Footnote 72 As in the studio recording of “Good Bait,” Pozo's open-tone on beat 4 (pattern 2) did not clash with Nelson Boyd's walking bass and Teddy Stewart's swing patterns in section C. What is more, Pozo plays within the actual arrangement in the second C section by cuing the repetition of the twelve-bar blues chorus with two open-toned attacks, one on the last eighth-note beat of the concluding chorus and another on the downbeat of the next chorus (pattern 5). He executes this same sequence of attacks in the next chorus as he marks both the chord changes from bars 4 to 5 and 8 to 9 of the twelve-bar blues cycle and the section's conclusion leading to the coda.

By February 1948 Pozo had grasped not only the rhythmic intricacies of playing in a jazz rhythm section but also the structural elements of jazz musical forms and the arrangement's dynamics. For example, his playing in “Good Bait” at the Salle Pleyel in Paris on 28 February 1948 shows a thoughtful sensitivity to the laidback swing groove demanded by the arrangement and executed by the entire band.Footnote 73 Again, he locked in with the rhythm section by utilizing patterns 2 and 3 and avoiding pattern 1. He also accentuated the arrangement's climax by introducing “flams” or two sixteenth-note open-toned “attacks” on the and-of-four of several measures in the concluding chorus.

Like in the Salle Pleyel performance of “Good Bait,” Pozo's playing on “One Bass Hit” excels.Footnote 74 It is important to point out that he did not play on “One Bass Hit” at the Carnegie Hall and Cornell University concerts, presumably because he had not yet learned the arrangement's intricate orchestral punches and breaks that accompany the featured bass solo. By the time of the band's performance at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on 19 July 1948, however, Pozo had mastered the arrangement.Footnote 75 In both the Pasadena Civic Auditorium and Royal Roost (2 October 1948) recordings, he is particularly consistent and sensitive to the arrangement's form and dynamics in the patterns he uses for each chorus. His sensitivity to the music is especially notable in the Royal Roost performance in which he changes patterns in the A and B sections of each thirty-two-bar chorus while also joining other players in the rhythm section in hitting with the orchestra. The excitement engendered by the band's exuberantly coordinated performance is clearly audible in the audience's reaction in both recordings, particularly during the last shout chorus when the entire band comes to a slow and screeching halt, which Pozo marks with glissandos on the conga's head; he then immediately dives into the bridge, which is highlighted by orchestral hits on the and-of-three of every bar.

Reviewers of the band's earliest studio recordings with Pozo did not always agree in their assessments. For instance, Down Beat gave “Good Bait” a two out of four “eighth note” rating, complaining that the band's performance was “ponderous, noisy, and sloppy for the most part,” while Will Davidson of the Chicago Daily Tribune praised Gillespie, saying “practically everything he does makes musical sense.”Footnote 76The Record Changer praised “Good Bait's” “exceptionally graceful Cubanish beat, over which the band plays its powerhouse figures with mounting tension and drive.”Footnote 77 By the band's European tour in winter 1948 and its tour of the West Coast later that summer, most writers agreed on the band's exceptional playing and powerful dynamics. Of the performance at the Trianon Ballroom in San Francisco on 16 July, Ralph J. Gleason observed: “[Pozo] and [Teddy] Stewart have so many rhythmic patterns worked out between them that they seem almost to act as one man many times.”Footnote 78 Pozo's and Stewart's playing on “One Bass Hit” in Pasadena just three days later clearly exemplifies Gleason's assessment.

In addition to pieces in which Pozo had to negotiate his playing within a swing rhythmic structure, the Gillespie band also recorded some whose rhythmic frameworks are built significantly on Afro-Cuban musical principles. In the studio recording of “Algo Bueno” made on 22 December 1947, McKibbon uses a common bass pattern in son music known as tresillo, which easily compliments patterns 1, 2, and 3, all of which Pozo uses.Footnote 79 Clarke limits his playing to eighth-note rim shots on beats 3 and 4 of each bar in addition to attacks on the bass drum and cymbals to accentuate orchestral hits. After two choruses, however, a tenor saxophone solo occurs at the bridge, which has a swing rhythmic feel complimented by McKibbon's walking bass, Clarke's swing pattern on the ride cymbal, and Pozo's patterns 2 and 3 (with pattern 1 snuck in for a couple of bars). The band performed “Algo Bueno” at the Salle Pleyel concert in Paris in February 1948. Unlike the studio recording, Pozo plays pattern 1 almost exclusively in the first chorus, locking in easily with the tresillo bass line, Clarke's bass drum hits on each downbeat and dampened eighth-note snare attacks on beats 3 and 4, the whole-note piano chords played by John Lewis, and the eighth-note maraca pattern played by Gillespie.Footnote 80 Clarke's and Lewis's parts in the first two choruses are not typical of either son music or jazz, yet they do seem to fit in with the other rhythm section parts. In addition, the chorus's melody (played by the trombones accompanied by the saxophones and responded to by the trumpets) does not correspond to the clave beat, making “Algo Bueno” like “Manteca” (to be discussed shortly) a quintessential hybrid of Cuban son and bebop music, better known as Cubop.

In his biography of Gillespie, Alyn Shipton suggests that Pozo's playing on “Algo Bueno” is “almost too enthusiastic”Footnote 81 and then continues: “The band feels as if it is being held back a little and strains like a greyhound on the leash at the start of the brief saxophone solo [i.e. at the bridge], where there is suddenly a break into a four-square swing rhythm.”Footnote 82 Eventually Shipton singles out Pozo in order to differentiate Gillespie's big band version of “Algo Bueno” from Coleman Hawkins's earlier version (“Woody 'n’ You”), whose absence of Latin rhythm is, Shipton states, “more than compensated for by Pozo.”Footnote 83 As ethnomusicological perspectives on jazz performance practice show, rhythm section players collectively negotiate a shared sense of the beat to strike a groove, whether that groove is Latin, jazz, or a combination of the two. My analysis above shows that Pozo regularly and imaginatively adjusted his playing to best fit into the band's swing rhythmic framework, as did Gillespie's bassist, pianist, and drummer in the more son and clave-based framework of “Algo Bueno” and other pieces. Even jazz critic Ralph J. Gleason understood the fundamentally collaborative and interactive approach of Gillespie's rhythm section players with Pozo. On the other hand, Shipton's comments also remind us of the occasional unease felt among Gillespie's musicians over Pozo's compositional ideas. For, as the same ethnomusicological perspectives also stress, discursive practices enable the power inequities that ultimately shape and give meaning to the creation and reception of music.

“Manteca” and Bebop's Modernist Imperative

Recorded in the studio on 30 December 1947, “Manteca” became an immediate audience favorite, and it remains one of the most, if not the most, recognized Afro-Cuban jazz pieces. Upon its commercial release in early September 1948, writers gave both sides of the record (“Cool Breeze” was the B side) mostly strong reviews. Down Beat commented that “Manteca” was the highlight of Gillespie's theater performances “because it's a thrilling arrangement and spots some fluent Diz.” “Both [sides],” the review continues, “use the Afro-Cuban rhythmic pattern that he [Gillespie] has done so much with of late.”Footnote 84 The Chicago Defender's “Wot's Hot” column included “Manteca” in its list of bebop and hot jazz records for 25 September.Footnote 85 European reviews were similarly positive. The French periodical Jazz Hot noted that Pozo's playing “est toujours aussi formidable” and that the bass part was “magnifique.”Footnote 86

More than just using Cuban rhythms, “Manteca” juxtaposes compositional structures from son and jazz music. Gillespie's accounts of the genesis of “Manteca” are well documented on audio and print sources and vary little from one account to the next.Footnote 87 The story begins with Pozo approaching Gillespie with an idea for a song. He first sang the bass line (Example 3) followed by the part for the tenor and baritone saxophones (Example 5), the trombone section's part (Example 7), and finally the trumpet section's part, all of which were to be played together in counterpoint. Gillespie stressed that not only did Pozo compose the introduction of “Manteca,” but that his dictation included the arrangement itself. Pozo then dictated the main melody, which would become the A section of the piece's AABA form.

Example 3. “Manteca” (Walter Gilbert Fuller, John Gillespie, and Luciano Chano Pozo Gonzales), recorded 30 December 1947 by Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra, bass line in contratiempo(used by permission of Music Sales Corporation/Gr. Schirmer, Inc. and “A” Side Music LLC).

Drawing on his background as a commercially successful composer, professional musician, and entertainer in Havana, Pozo continued to draw from popular Cuban music sources in his compositional contributions to “Manteca.” Example 3 represents “Manteca's” signature bass pattern introduction, which is played by Al McKibbon and accompanied by Pozo playing pattern 1 on the conga. The bass part's rhythmic pattern, beginning on the “and” of beat 2 and accenting most of the remaining upbeats of the two-bar pattern, had already become one of several patterns that Cuban bassists, violinists, trumpeters, vocalists, and others began to favor by 1944. These patterns formed the basis of performing the “son montuno” style, which Cuban musicians and dancers described as having a “contratiempo” or “against the beat” feel. The combination of cyclic figures in “contratiempo” accounted for the dense and syncopated rhythmic textures that Cuban musicians and dancers valued in their dance music.Footnote 88Example 4 shows a bass figure similar to McKibbon's bass line in “Manteca” taken from a recording of a “son montuno” composed in Havana in 1944 by the Cuban group Arsenio Rodríguez y Su Conjunto. It includes the conga pattern, which alternates patterns 3 and 1 for the two-measure cycle.

Example 4. “Mi china me botó,” recorded 6 July 1944 by Arsenio Rodríguez y Su Conjunto, bass line in contratiempo. (“Mi China Me Boto” by Arsenio Rodriguez Scull. Used by Permission of Peer International Corporation.)

As “Manteca's” opening bass pattern continues, the tenor and baritone saxophones introduce a second two-bar figure (Example 5), which, after beginning on beats 1 and 2, accent most of the remaining upbeats. This same figure was commonly used as violin “guajeos,” or “ostinato figures,” in the “mambo” or final cyclic section of the Cuban danzón. Like the previous bass figure, this pattern also met the expectations of Cuban musicians and dancers for music played in contratiempo (Example 6). Next, the trombones introduce the third and final figure of “Manteca's” introduction. As can be seen in Example 7, this pattern is marked by a triplet figure, which concludes the first bar of the two-bar pattern. Cuban violinists commonly played a similar figure, as seen in Example 8.

Example 5. “Manteca,” saxophone riff.

Example 6. “Arcaño y Su Nuevo Ritmo,” recorded 1944 by Antonio Arcaño y Sus Maravillas, violin guajeo.

Example 7. “Manteca,” trombone riff.

Example 8. “Miñona,” recorded ca. 1948 by Orquesta Ideal, violin guajeo.

Finally, the rhythmic structure and sequence of accents in the main melody of “Manteca” correspond with both the 2–3 clave and syncopated saxophone patterns utilized by Cuban jazz bands. These saxophone patterns were one of the primary musical markers of the mambo, which Cuban big bands helped popularize as early as 1944. In short, Pozo had composed a modern son for big band with all of the stylistic features of the dance music that was popular in Cuba at the time. Gillespie and Fuller, however, fixated their aural gaze on what they perceived as the piece's “repetitiveness” as well as its lack of the bridge section conventional in bebop music at the time. As Gillespie once stated, “Chano wasn't too hip about American music. If I'd let [“Manteca”] go like he wanted it, it would've been strictly Afro-Cuban, all the way. There wouldn't have been a bridge.”Footnote 89 To be sure, the big band performed entire Afro-Cuban pieces composed by and featuring Pozo, as exemplified in “Guarachi guaro” and “Cubana Bop,” in accordance with Gillespie's and Pozo's pan-Africanist and commercial aims. Fuller, however, remained solely emphatic over the importance of keeping jazz modern by making Pozo's musical ideas harmonically and structurally complex. As a result, Gillespie felt compelled to compose a bridge, while Fuller similarly felt compelled to “fix” the piece by completing the arrangement in accordance with his musical modernist expectations.

Writing in The New Yorker in July 1948, Richard Boyer claimed that the leaders of bebop music “resented the apostrophes of critics who referred to [African American jazz musicians of the previous generation], with the most complimentary intent, as modern primitives playing an almost instinctive music.” Boyer later identified Fuller as one of these leaders, and quoted him as saying, “Modern life is fast and complicated, and modern music should be fast and complicated.”Footnote 90 Later, in October 1948, the New York Amsterdam News asked Fuller to help define “this thing called Be-Bop,” to which he gave a concise explanation of the use of extended and altered chords. He also stated that in its use of harmony and melody “Be-Bop is definitely advancing to the level of contemporary serious music,” the composers of which, Fuller noted, were Igor Stravinsky, Paul Hindemith, and Arnold Schoenberg.Footnote 91 Accordingly, record reviewers often singled out Fuller's arrangements for their modernist tendencies. Record Changer, for example, praised “his theories of scoring, which are dangerously advanced” in its review of “Tin Tin Deo,” co-composed by Fuller and Pozo and recorded by James Moody and other members of the Gillespie big band, including Pozo on congas.Footnote 92

Given his predilection for modern or harmonically and structurally complex music, it is no surprise that Fuller complained about Pozo's musical ideas, which he might have credited to Pozo's “instinctive” and, perhaps even “primitive” talent for music. He once suggested that listening to Pozo's “Guarachi guaro” “will drive you nuts because . . . it just keeps going and repeats itself ad infinitum. And it never got off the ground like it should have because it wasn't structured.”Footnote 93 In spite of his concerns, Fuller continued to work with Pozo for James Moody's Blue Note recording session in October 1948, which Fuller actually led. In fact, far from seeing Pozo's music as an anomaly in bebop, Fuller seemed to be motivated by his desire to make Pozo's music sufficiently complex and modern similar to composers of, in his words, “contemporary serious music,” who also drew inspiration from so-called primitive musical sources. Accordingly, writers compared “Manteca” and the band's other Afro-Cuban pieces to Stravinsky's modernist and primitivist compositions, while also utilizing the language of the Dark Continent to make sense of Pozo's drumming, chanting, and dancing.

John Osmundsen reviewed the band's performance in Milwaukee in September 1948 for Down Beat, saying “Manteca” was “done almost as a tribal rite, becoming downright primitive.”Footnote 94 Osmundsen was specifically describing a new section that the band added to “Manteca” for their live performances featuring a conga solo and Abakuá chants performed by Pozo.Footnote 95 Another writer, for the Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet, reviewed the big band's performance at the Vinterpalatset in Stockholm on 27 January 1948 and indicated that he “could not help but think of Stravinsky” as a result of the band's “extremely colorful sound” and “fascinating, sometimes shocking, rhythmic experimentation.”Footnote 96 The 11 October 1948 issue of Life magazine featured Gillespie in a photographic essay sensationalizing the “music cult” of bebop. Of the essay's nine black-and-white photographs taken by Allan Grant, two introduced Life's readers to Pozo playing a conga strapped around his shoulder accompanied by captions that read: “Frenzied drummer named Gonzales (but called Chano Pozo) whips beboppers into fever with Congo beat. Dizzy rates him world's best drummer”; and “Shouting incoherently, drummer goes into a bop transport.”Footnote 97 Grant took at least two more photographs of Pozo; the captions (presumably added by an editor) read “Jungle-type drum being played by drummer of Dizzy Gillespie's band; he beats on the drum with his hands instead of a drum stick.” These photographs, however, were not included in the published version of the essay.Footnote 98

On the one hand, Gillespie and Shaw's plan to capitalize on Pozo's drumming, chanting, and dancing as a featured act worked, but it usually translated into an exoticized spectacle of jazz's African and primitive essence for U.S. and European audiences. In fact, for some writers, Pozo's “frenzied” drumming and “incoherent” chanting was consistent with bebop's dissonant and cultish demeanor. On the other hand, Gillespie's intention to re-Africanize jazz music led to the creation of some of the most critically acclaimed pieces of the bebop era. Record Changer expressed particularly strong excitement over “Manteca's” “promising” introduction (composed and orchestrated by Pozo) but then bemoaned most of the remaining sections of the arrangement (composed and arranged by Gillespie and Fuller): “What sounds as if it's going to be a wonderfully loose experiment in Afro-Cuban tempo becomes an experiment in blatant power.”Footnote 99 Indeed, Gillespie and Fuller exerted their power over the direction of Pozo's compositional ideas because of their concern over losing the complete identity of jazz that was modern to Afro-Cuban music that was too primitive. As we will see in the final section, the confluence of these motivations and discourses came to a head in the creation and performance of “Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop.”

Embodying the Dark Continent

Upon the death of George Russell on 27 July 2009, Ben Ratliff wrote in the New York Times: “Russell was a major figure in one of the most important developments in post-World War II jazz: the emergence of modal jazz, the first major harmonic change in the music after bebop.”Footnote 100 Russell formulated his theory of modal jazz, called the Lydian Chromatic Concept, and began composing in accordance to its tenets in 1947 during the height of bebop's popularity. His first composition to be based on the Lydian Chromatic Concept was “Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop,” a two-movement suite often titled Afro-Cuban Drums Suite, which Gillespie commissioned. The second movement was based on Gillespie's performance with Asadata Dafora, Norman Coker, and the ensemble of Cuban and Puerto Rican percussionists on the “African Interlude” program in May 1947.Footnote 101 Pozo and the band premiered the two-movement suite on 29 September at Carnegie Hall.

Although some reviewers of the concert were quite critical, others reported on the financial success of the event as well as on the success of the suite itself.Footnote 102 For instance, Michael Levin reported in Down Beat that one of the “stand outs” of the program was the second movement. “The crowd,” Levin wrote, “unquestionably liked the Cubano Bop number . . . illustrating a point the Beat has often made: that there is much jazz can pick up on from the South American and Afro-Cuban rhythm styles.”Footnote 103 Despite voicing her disapproval of bebop as represented by Gillespie in this concert, Lillian Scott of The Chicago Defender also noted that the audience “liked [the suite the] most,” adding that the music had “some trace of musical meaning and integrated thought, probably due to co-composer-arranger George Russell.”Footnote 104 And Barry Ulanov somewhat flippantly commented that the band was “remarkably adroit in its negotiation of a new little nothing called the Afro-Cubano Drums Suite [i.e., “Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop”].”Footnote 105 Even jazz enthusiasts in Paris learned of the success of the concert as a result of the “nouveaux effets” and “conceptions originales” of John Lewis's “Toccata for Trumpet” and “Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop.”Footnote 106

One critic writing for the New York Herald Tribune complained, however, about the program title, “The New Jazz,” and about promoter Leonard Feather, who from the stage described Gillespie's music as “modern American music.” According to this critic, the music “goes back [in time] rather than forward” because it “[leans] heavily on the early Stravinsky of ‘Le Sacre du Printemps’ and . . . on the impressionism of Delius and Debussy.”Footnote 107 Although the writer never identified the suite by name, it is likely that the reference is to this piece. Historian Lawrence Reddick similarly described the studio recordings of “Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop” as “Stravinsky-like.”Footnote 108 Indeed, the introduction of “Cubano Be” features two techniques—reiterated chords and cacophonous textures—that also figure prominently in Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps and other early European modernist works. Russell based the introduction on a C7flat9 chord, and thus derived the harmonic and melodic material from this chord's “parent scale,” the B-flat auxiliary diminished scale.Footnote 109 Nevertheless, the tonal, timbral, and textural material of the suite resonated with the modernist and primitivist aesthetics of jazz critics, composers, and arrangers.

After this concert Russell suggested to Gillespie that Pozo “put on his jungle outfit” and sing chants and play rhythms from the Abakuá repertory at the opening of “Cubano Bop.”Footnote 110 Intermingled in Russell's suggestion to sensationalize and further exoticize Pozo by putting him in a “jungle outfit” was his interest in exploring non-Western religions and universality: “We were striving for exactly that kind of world grasp, a kind of universality. There were all kinds of influences in that piece, but chief was the melding of the Afro-Cuban and . . . jazz.”Footnote 111 Pozo's solo was added by the time the band performed at the Boston Symphony Hall on 19 October. As writers now included the language of the Dark Continent to describe Pozo's featured drumming and singing in the suite, some African American members of the audience, according to Russell himself, “laughed” and “were embarrassed by it.” “The cultural snow job had worked so ruthlessly that for the black race in America at the time its native culture was severed from it completely. They were taught to be ashamed of it, and so the black people in the Boston audience were noticeable because they started to laugh when Chano came on stage in his native costume and began.”Footnote 112

Surely, the presence of whites in the audience determined in no small measure the desire among some black audience members to disassociate themselves from this black Other; hence, their reactions to Pozo's singing, drumming, and “jungle outfit.” In addition, the African American press rarely published articles that commented on Pozo's Afro-Cuban contributions, further suggesting the silencing of Pozo, even though these same periodicals regularly printed advertisements and published reports of Gillespie's concerts in Europe as well as in the United States. One exception is the Atlanta Daily World's record review of “Cubana Be” and “Cubana Bop,” which are described as “a pair [of recordings] strongly flavored with Cuban-African vocal and percussion effects with the good ‘ole’ jazz orchestral sounds. ‘Bop’ is the one which features . . . Chano Pozo on congo [sic] drums in the intro; he throws in some weird vocal sounds throughout the piece.”Footnote 113

Ultimately, as Russell pointed out, the “cultural snow job” or discourses of cultural progress and racial uplift “severed” African Americans from their “native culture,” which Pozo's drumming, singing, and dress signified for Russell and Gillespie. Mbadiwe and Dafora actively organized programs and performed African folkloric dances to subvert this predisposition shared among whites and blacks toward the cultural practices of black Others. Similarly, Herskovits and Blesh, along with Gillespie, believed that to clarify the relationships between African Americans and their African past, and, thus, the relationships between jazz and African music, would help “solve the problem of the Negro in our democracy” and, in effect, reclaim African Americans who had “come to accept the myth.” In spite of these efforts, the sounds, movements, and dress embodied in Pozo's featured solo in “Cubano Bop” still resonated deeply with, and thus perpetuated, audiences’ (mis)understandings of Africa.

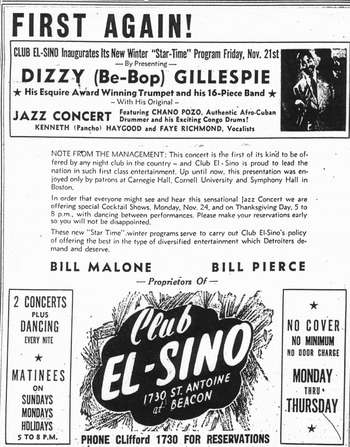

On the eve of the band's two-week run at Detroit's El Sino club later that month, The Michigan Chronicle declared that “the most awaited composition is Gillespie's Afro-Cubano suite [“Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop”] . . . a highly impressionistic number complete with bongo and conga drum solos.”Footnote 114 The advertisement for these shows read in part: “Featuring Chano Pozo, Authentic Afro-Cuban Drummer and his Exciting Congo Drums!” (Fig. 3).Footnote 115 Pozo was also mentioned in a highly sensationalized article by Winthrop Sargeant in Life on 6 October 1947.Footnote 116 Titled “Cuba's Tin Pan Alley,” the article describes Havana's music scene, or in Sargeant's words, “Havana's shabbiest cabarets and voodoo lodges [from which] pours an endless flood of sultry rhythms, which are danced to all over the world.” Predictably, his writing starkly conveys the images of the scene's underworld, brothels, and “bullet-scarred, marijuana-smoking characters.” He also portrays Havana's song publishing industry as hopelessly disorganized and violent. As a case in point, Sargeant retells Pozo's infamous encounter with music publisher Ernesto Roca in Havana in 1945. After describing Pozo as a “big, flashily dressed Negro,” he explained:

Pozo, whose masterpiece was a ditty called El Pin Pin, had achieved some fame on the side as a dancer and a player of the big African conga drum. He approached his publisher, one Ernesto Roca, and demanded an extra thousand dollars as an advance on a new song. Roca refused and Chano Pozo assaulted him. Like all prudent Havana music publishers, Roca had an armed bodyguard who promptly pumped four bullets into Chano Pozo's midriff.Footnote 117

Figure 3. Advertisement for Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra at the El Sino club, Detroit, The Michigan Chronicle, 22 November 1947 (used by permission of the Michigan Chronicle and Frontpage Newspapers).

Also included in the article is a photo of Pozo lounging on satin-covered pillows and looking at the sheet music for “El pin pin.” The article then describes the “underworld of African Cuba,” which, according to Sargeant, is “both musically and spiritually an outpost of a jungle civilization whose headquarters are still near the Niger and Congo rivers across the Atlantic.”Footnote 118 He then identifies the various instruments and musical practices coming from Cuba's “African underworld,” including those of the ñañigos or Abakuá.

This issue of Life was delivered to news stands and homes across the United States just one week after Pozo's performance with the Gillespie band at Carnegie Hall. Even if Gillespie's audiences and critics had not read this article, however, they were still prone to interpreting Pozo's singing and playing as embodying that of the Dark Continent. Some jazz critics in Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, and France made similar uses of the discourse of the Dark Continent in their reviews of Gillespie's performances in Europe from January to March 1948. Recurring observations and themes in reviews of the band's performances throughout this tour included Gillespie as the creator of bebop, the introduction of bebop as performed by a big band to European audiences, Gillespie's virtuosity and high tessitura on the trumpet, the excessive sonic power of the brass section, and the frenzied excitement and, at times, disapproval of the audience.Footnote 119 Many reviewers also commented on the music's strong “Latin American” influence. Although the band's set list included “Manteca,” “Cubano Be,” and “Cubano Bop,” it was the two-movement suite that received most attention.

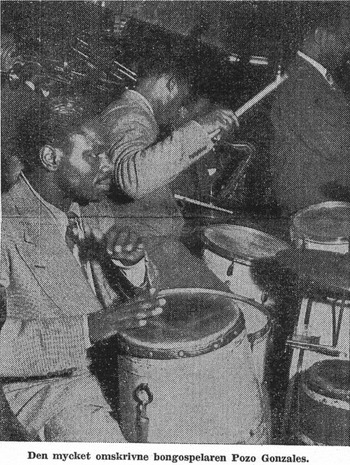

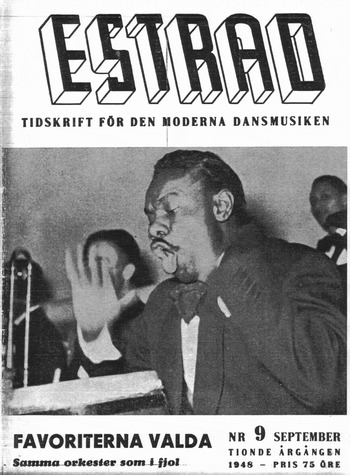

One Swedish reviewer characterized “Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop” as “some sort of hybrid between voodoo worship, rumba and jazz” (Fig. 4),Footnote 120 and a Danish writer remarked that the “brilliant Pozo Gonzales created a real jungle mood with his bongo drums in ‘Afro-Cuban Drum Suite’ [“Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop”] which has a single motive from ancient, ritual black music.”Footnote 121 Two other reviewers of the band's performances at the Vinterpalatset in Stockholm and Cercle Royal et Artistique in Antwerp noted that Pozo's performances of the suite were the highlights of these concerts (Fig. 5).Footnote 122 According to an Italian writer, however, some audience members at the band's first concert on 20 February at the Salle Pleyel in Paris booed not only “Cubano Be” and “Cubano Bop” but also the band's featured vocalist Kenny Hagood. The writer also indicated that for the second concert on 22 February Gillespie cut “certain passages” of the suite, perhaps because of the previous audience's reaction. However, the audience for the third concert on 29 February did not include hecklers, and, thus, “the orchestra was able to be completely at ease.”Footnote 123 It was Pozo's performance at this third concert that French composer and jazz historian André Hodeir referenced in the following:

[The rhythm section] consists of four instruments. . . . The fourth . . . is the bongo [sic], a sort of tam-tam directly adapted from an African instrument. It is played by Pozo Gonzales who has a beautiful head of a native of the West Coast [of Africa]. “A real cannibal,” said one brave lady sitting next to me, with a little shiver of horror at the idea she could meet him at the corner of the jungle. . . . Nevertheless, he was amazing. He was greeted in different ways for his featured number, in which he played in front of the orchestra. One fool shouted: “To Timbuktu,” as if jazz came from St. Petersburg. Yet, the man “took” his public: it's important to note that his disturbed eyes were rolling while he repeated [the word] “Simbad” which was then followed by silence. Then the entire hall fell silent, even the scoffer who had just shouted, as Pozo repeated this word. This was a moment that was truly oppressive. Finally, he shouted again “Simbad!” And then came the audience's general relief, applause, laughter, and euphoria.Footnote 124

Figure 4. Chano Pozo performing in Stockholm, Sweden. The caption reads, “The highly publicized bongo player Pozo Gonzales.” Estrad, February 1948.

Figure 5. Chano Pozo on the cover of the Swedish jazz periodical Estrad, September 1948.

Chano Pozo apparently never gave an interview explaining his intentions in utilizing Abakuá and other Afro-Cuban expressive elements with the Dizzy Gillespie big band.Footnote 125 However, we do have recordings, photographs, and accounts, all of which formed what Bakhtin defined as “an organic part of a heteroglot unity.”Footnote 126 In theorizing the role of the listener's response in the “actual life of speech,” Bakhtin states:

To some extent, primacy belongs to the response, as the activating principle: it creates the ground for understanding. . . . Thus an active understanding . . . establishes a series of complex interrelationships, consonances and dissonances with the word and enriches it with new elements. It is precisely such an understanding that the speaker counts on. Therefore his orientation toward the listener is an orientation toward a specific conceptual horizon, toward the specific world of the listener.Footnote 127

The varied responses to the music and performances presented here constitute discursively thick moments in the sequence of interactions among musicians and dancers, and between performers and their audiences. Based on this formulation, these responses and the discourses in which they were articulated help us understand the intentions of Pozo, Gillespie, Dafora, Mbadiwe, and others as complex, conflicted, and engaged with epistemological notions of Africa and African culture. Some types of responses to their work—nervous embarrassment, fascination, laughter, horror, and disgust—suggest that their efforts, despite their intentions, perpetuated long-held ideas of Africa and stereotypes validating the notion of black inferiority. Other reactions, namely the acceptance of jazz's African and Caribbean origins and the growing musical and ideological currency of Pan-African collaborations among jazz musicians into the 1950s and 1960s, indicate that they indeed helped shape an alternative epistemology of African history and its significance to black cultures of the New World for audiences beyond academia.

This last point lends insight into the question of Afro-Cuban jazz's supposed marginality in the jazz historical narrative. In the 1950s jazz educator and founder of the Institute of Jazz Studies Marshall Stearns adapted the narrative of jazz history originally proposed by Dafora, Blesh, Borneman, and others. Stearns designed charts that visually mapped out the course of jazz's evolution and the interrelationship of its styles, including Afro-Cuban jazz, which was set off to the right side (or the margins) of the chart. Stearns supplemented these charts with recordings when lecturing to his students and audiences, including those in the Middle East for whom the Gillespie big band performed under the auspices of the State Department in 1956.Footnote 128 According to Down Beat, the first half of the program had Gillespie and Charlie Persip “demonstrate African drum rhythms, following which Herb Lance sings several spirituals.”Footnote 129 This discourse of jazz's evolution has been uniquely effective in positing the “progress” of African American music and culture and its relationship to an African and Caribbean past. What it could not and still is not able to do is to chart the dialogues of modern Africans and Afro-Cubans with their African American contemporaries, the intersecting points of which form the crux of jazz's place in the Afro-Atlantic.