The ability to shape public perceptions is vital for both performers and politicians, and during wartime, the stakes are even higher. As Aeschylus observed more than two millennia ago, “In war, the first casualty is truth.”Footnote 1 World War I saw an unprecedented deployment of propaganda in the United States by both Germany and Great Britain—first to persuade the reluctant neutral nation to join the conflict, and then to maintain US loyalty to the Allied cause in the face of devastating losses and crushing financial commitments. Part of this campaign for the hearts and minds of American voters involved a battle over the role of Austro-German music and musicians in American concert life. The works of Central European composers from Bach to Richard Strauss dominated the concert halls of the New World just as they did those of the Old World, and German-speaking immigrants had played crucial roles in the development of American musical institutions in the nineteenth century. During the course of the war, this immigrant group came increasingly under attack.

From the beginning of the European War in summer 1914 through the US declaration of war on April 6, 1917, little changed in the concert organizations of the United States. From that point to the Armistice on November 11, 1918, however, opposition to German musical influence grew increasingly strident, as objections fell into two broad categories. One line of attack focused on the prevalence of German repertoire on American concert programs, with distinctions parsed among vocal music in the original language and in translation as well as among instrumental works by living Austro-German composers and those by composers of previous generations. As we will see, the debate centered on whether German cultural products like operas or symphonies could serve to lower American resolve and morale, or whether they were the neutral cultural property of all people. A second line of attack targeted conductors, soloists, and orchestral players of German background, with attention to how long the musicians had been resident in the United States and whether they had begun or completed the naturalization process. In this case, the debate went beyond the impact on American morale to include the possibility that some musicians of foreign birth might be acting as spies. The growing opposition was potently symbolized in the famous incident that took place on October 30, 1917 in Providence, Rhode Island, when the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) ignored a request to play “The Star-Spangled Banner” at a concert there, leading to nationwide condemnation of the orchestra's German-born conductor, Karl Muck, who had not been informed of the request. The incident brought the two broad concerns of repertoire and personnel together in such a symbolically charged way that the controversy continued to simmer for months before again boiling over in March 1918.

The voluminous scholarly literature on this incident has thoroughly documented the extensive debates in contemporary newspapers as well as the federal investigations and eventual arrest of Muck in March 1918, but it has not addressed the crucial role played by a shadowy propaganda magazine named The Chronicle, published in New York from March 1917 to November 1918. This journal was marketed to the United States’ wealthy elite and was available to subscribers by invitation only. In its pages, the editor Richard Fletcher urged his upper-crust readers to root out German culture wherever they found it lurking in US society. Employing no professional journalists, he invited readers to submit articles regardless of their qualifications. By strategic publication of spurious news stories and xenophobic editorials, he spread fear and suspicion through the most rarefied strata of US society. The journal was instrumental in blacklisting suspicious arts organizations and fomenting prejudice against enemy aliens. Using the pages of The Chronicle, Fletcher played an important role in shaping the discourse about German music, culture, and musicians in the United States during the final year of World War I. This article examines for the first time this little-known but influential journal, shedding light on the origins of twentieth-century propaganda techniques and the manipulation of musical taste for political ends, a topic with significant implications in the following century.

The Chronicle as an Organ for High Society

The relevance of the Muck “Star-Spangled Banner” incident to the evolution of musical culture in the United States, along with the intriguing personal stories of the principal actors in the drama, have inspired generations of scholars to delve ever deeper into the documentary evidence. The bibliography lists over a dozen such studies, three of which are worthy of mention here.

Irving Lowens published the first scholarly discussion of the incident in “L'affaire Muck: A Study in War Hysteria (1917–1918)” in 1947. Writing shortly after the end of World War II, he noted, “From the evidence at hand, it appears that Dr. Muck was an innocent victim of our violent World War I anti-German hysteria, so fortunately missing in World War II; yet the legend of his culpability lives on.”Footnote 2 In the context of 1947, Lowens provided an important perspective on the atmosphere of World War I. As Annegret Fauser has demonstrated in her study of American music during World War II, American concertgoers did not demand the elimination of German music as they had during the previous war.Footnote 3 Lucy Claire Church examined the incident as part of a 2015 dissertation on the impact of World War I on musical ethics in the United States, chronicling more extensively than any previous scholar the role of Mrs. William (Lucie) Jay in the attacks on Muck.Footnote 4 Most recently, Melissa Burrage published an entire book on the topic.Footnote 5 Burrage's study introduces extensive background information drawn from a variety of sources along with a voluminous number of citations on the campaign to oust Muck. As I will show later in this article, however, the author has misdated several crucial citations, leading to erroneous conclusions on the timing and significance of the contributions of Mrs. Jay.Footnote 6

Without exception, these scholarly analyses point out that the US press and public treated Muck unfairly. Whatever the flaws in his personal character—and Muck was not a likable person—repeated studies have shown that he was not to blame for the omission of the anthem from the Providence program and furthermore that he moved quickly to rectify the situation by playing the anthem in every subsequent concert. The opposition to him was part of a larger movement in the United States that would soon alter the repertoire of orchestras and opera companies and would force the retirement from the stage of numerous musicians, including the popular Austrian violin soloist Fritz Kreisler and all the unnaturalized members of the Philadelphia Orchestra. In this campaign to eliminate German music and musicians, The Chronicle played a crucial role during the brief span of World War I and helped to establish precedents that would haunt music in the United States for generations.

The role played by The Chronicle was not immediately obvious. Persons close to the center of the Muck controversy and other anti-German music publicity seemed to be aware of its existence, but it was usually mentioned in passing without further comment. Among all the scholarly studies of Muck, only four refer to it: Lowens quotes briefly from a Chronicle article with no source citation; Gayle Turk quotes a clipping from The Chronicle found in a BSO scrapbook; Church reproduces a New York Times quotation from a Chronicle article but states that she was unable to identify the journal or find a copy; and Burrage mentions the journal in passing.Footnote 7 This magazine is indeed challenging to locate, as WorldCat lists only seven libraries that hold issues of it. The fact that the word “chronicle” appears in so many unrelated book and journal titles complicates the identification process. Owing to copyright deposit requirements, there is a complete run of the journal in the Library of Congress, making it possible to survey the entire publication history of this obscure journal.Footnote 8

The Chronicle began publishing in March 1917 (a month before the United States declared war) and ceased publication in November 1918, the month of the Armistice. It appeared at the beginning of each month, for a total of twenty-one issues. Published on luxurious handmade Italian paper (more on that below), the journal was unpaginated and contained no advertisements in its first six monthly issues. As noted on the masthead, it was available by subscription only, but subscribers had to be invited by the editors (Figure 1). At twelve dollars a year, the sixteen-page sheet was reputedly the United States’ most expensive journal in an era when most daily newspapers in major metropolitan areas had a cover price of one cent per issue.Footnote 9 The limited subscriber list and lack of advertising raise questions about how the journal could have sustained itself financially, even with such a high cover price. Everything about this journal seems designed to be exclusive, like a private club to which only a select few are admitted.

Figure 1. Masthead of the first issue of The Chronicle, March 1917. Digital image supplied by Library of Congress Duplication Services.

The journal's editorial policies were as exclusive as its subscription policies. The executive editor was Rebecca Lemist Esler, the wife of Wall Street banker Frederick Esler; the rest of the staff consisted of publisher James W. Pennock Jr. and editor Richard Fletcher. The articles in The Chronicle were written by subscribers, and advance publicity stated that it was “of Society, by Society, and for Society.”Footnote 10 The first issue took pains to communicate that in keeping with the seriousness of the times, society was becoming less frivolous. This journal provided an outlet for America's social leaders to share their thoughts in “a medium through which intelligent people who are not professional writers may speak to the public on the topics of the day.”Footnote 11

The mainstream press poked fun at the first issue of the journal in March 1917, especially its protestations of earnestness. A lengthy review in the New York Tribune was skeptical of high society's ability to shed frivolity for seriousness, citing an array of articles in the inaugural issue on topics such as tennis, amateur actors, and techniques for hosting artistic celebrities with the right balance of deference and condescension.Footnote 12 In the face of criticism and ridicule, Mrs. Esler announced in the last week of March that she had severed her ties with The Chronicle, leaving it in the hands of publisher Pennock and editor Fletcher. In a frank interview with a reporter from the New York World, she revealed her understanding that Pennock, who had previously worked as a traveling salesman for a wholesale clothing house, supplied the financial backing for the venture. She was not complimentary of the work of her colleagues on the first issue, stating, “I disliked the editorials in the first number. I called them ‘cheap.’ There were absurd misspellings in the articles. But Mr. Pennock likes the proofreader and editorial writer, Mr. Fletcher. He does—what do you call it?—the setting up of the magazine.”Footnote 13 The final impetus for her departure had been Pennock's desire to write an article for the second issue entitled “What Men Should Wear.” In her view, his background as a clothier did not qualify him to give fashion advice to the men of New York's exclusive Four Hundred.

Despite the initial controversy, The Chronicle continued to appear monthly throughout the summer and fall of 1917. After the United States Congress voted to declare war on Germany on April 6, 1917, subsequent issues of The Chronicle gradually incorporated more commentary on the war and high society's relation to it. The October 1917 issue contained a remarkable four-page article entitled “America First and the German-Born” that printed over fifty statements from German-born citizens regarding the US entry into the war. Most were perfunctory sentences of unwavering loyalty, but a few dared to be more nuanced, like Richard Schiedt of Lancaster, Pennsylvania: “I swore my oath of allegiance on the eighth of October, 1892 without reservation and restriction, and my Prussian training has taught me that the violation of an oath is self-annihilation. However, allegiance does not mean blind submission. I was, and will continue to be, opposed to the entrance of our country into this war.”Footnote 14 As before, the views expressed in the magazine were read only by subscribers and did not achieve wide currency in American culture.

In August, a United Press reporter tried to get more information on this elusive vehicle for social communication. Visiting the journal's offices at 507 Fifth Avenue (across the street from the recently constructed New York Public Library), he met Pennock, whom he described as “a dapper little man who talks high-browish and wears suits, ties and hose of the same shade of green, brown, violet or gray.”Footnote 15 Pennock told the reporter, “Yes, I'm in charge here. It's immaterial who the publishers of The Chronicle are,” refusing to let the journalist see a copy of the magazine.Footnote 16 He confirmed that contributors were subscribers, and that subscription was available by invitation only. The U.P. reporter went on to state, “The editor is Richard Fletcher, who says, ‘Fawncy that, now,’ and calls you ‘Old Top.’ He's only been over from London a short while. And he says he ‘cawn't’ tell you much about The Chronicle. He did reveal the names of some of the subscribers-contributors,” all prominent members of the social register whose names would have been recognizable to readers as wealthy, politically connected members of New York's elite society.Footnote 17 Astute readers would also have noted that this short list included three widows and one divorcee, a fact whose significance will become clear shortly. The United Press article again poked fun at the pretensions of the new journal, ending with the question, “How is The Chronicle ever going to convince the public that society is 100 per cent pure if the public is never to see The Chronicle?”Footnote 18

With the September issue, the magazine began accepting advertisements, but like its contributors, the advertisers were admitted by invitation only to ensure their appropriateness for the readership.Footnote 19 There were none of the splashy ads for patent medicines, cleaning products, or gadgets that filled the pages of contemporary popular magazines. Instead, The Chronicle's advertisements were limited to high-toned products from upscale advertisers. The September 1917 issue, for instance, offered “Early English Furniture” from an antique dealer on East Forty-Fourth Street, “Pearls and Jewels” from a Fifth Avenue jeweler, “Interiors and Furniture” from a Park Avenue decorating company, “Old English Silver” from Crichton Bros. of London, along with antique tapestries, Old Master paintings, and engraved stationery.

The Chronicle's Campaign against German Music and Musicians

Starting with the November 1917 issue, The Chronicle devoted much of its attention to a campaign against German music and musicians in the United States. This campaign proved singularly effective because of the unique intersection between the magazine's editorial policies and its exclusive subscriber list, which happened to include influential patrons of opera companies and symphony orchestras. This readership was significant because of the means by which classical music concerts were financed in the United States. Unlike in Europe, where concert organizations were generously funded by governments, orchestras and opera companies in the United States raised their own support. In order to keep ticket prices within the reach of the general public, these organizations relied on the generosity of wealthy patrons to provide additional financial underwriting. For some organizations, a single benefactor covered all deficits, as for instance Henry Lee Higginson for the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Harry Harkness Flagler for the New York Symphony Orchestra. Other organizations, for example the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and the Metropolitan Opera Company, were dependent on a broader group of patrons who served as board members with decision-making capacity as well as financial contributors. It was especially these persons whom The Chronicle targeted for its subscribers.

The November issue appeared the day after the Providence incident, or too early to comment on the events of the previous night,Footnote 20 but it presciently contained two articles that related directly to the topic that would be on everyone's mind during the coming weeks. Fletcher wrote an article entitled “Boston Symphony and Boston Discord,” in which he stated that “numerous subscribers there [in Boston] are in revolt against Doctor Muck's further incumbency of his position because of his connection with the land of our enemy.” He went on reporting that an unidentified group of these “numerous” symphony subscribers planned to cancel their subscriptions or boycott the concerts in protest to Muck's presence on the podium. BSO patron Higginson was allowed to comment, and he pointed out that the members of the orchestra encompassed twelve different nationalities who had continued to work collegially since the beginning of the war because of their commitment to art. He objected strongly to Fletcher's statements, writing, “Sundry falsehoods have been spread in order to hurt the Orchestra, and to please whom? The Orchestra has been built up through many years to give art and pleasure to people throughout the land. The best way to destroy it is to spread lies about it. The best way to keep it fine is to regard it as an art institution, and nothing more.”Footnote 21 Fletcher used his prerogative as editor to conclude the article with a rebuttal of Higginson's plea for moderation: “The Chronicle has always maintained that during our life and death struggle against German Autocracy that ‘he who is not with us, is against us.’ Persisting in this inviolate principle, it is clear that even art must stand aside. The necessity of national unity precludes any conflicting interest. … Art must not be used, as the Germans have used civilians, as a shield against their enemies.”Footnote 22 His timing was fortuitous, as the November issue reached its exclusive subscribers just days after the Providence incident involving “The Star-Spangled Banner” on October 30.

The November issue also included an article by Mrs. William Jay entitled “German Music and German Opera.” In her first-ever published article, Mrs. Jay, who was the only woman on the New York Philharmonic board, argued that German instrumental music by “Bach, Mozart, Haydn, and others” was acceptable to American audiences, but she stated that “to give the German operas, particularly those of Wagner, at this time would be a great mistake. Given as they must be in the German language, and depicting in many cases scenes of violence and conflict, they must inevitably draw our minds back to the spirit of greed and barbarism which has led to so much suffering.”Footnote 23 As the 1911 photograph of her in Figure 2 clearly demonstrates, Mrs. Jay was not always opposed to Wagnerian themes, but the war inspired her change of attitude. Editor Fletcher added a postscript that raised the emotional temperature with a threat:

The Metropolitan Opera Company announces the entire category of operas by Wagner for its ensuing season in New York, Brooklyn and Philadelphia. Mrs. Jay valiantly fires the first shot against the menace of this insidious German propaganda. If the operatic arbiters persist in presenting these works in German, the controversy shall be taken to the officials in Washington. German art is literally the mortar in the crumbling structure of Pan-Germanism—the genius of Beethoven, Goethe, Schiller, Heine, Bach, has always been employed to further the Teutonic plan for world dominion.Footnote 24

Figure 2. Theodore C. Marceau, photographer. “Mrs. William Jay, full-length-portrait, standing, dressed in theatrical costume, holding a spear,” ca. 1911.

It is impossible to know for sure how influential this threat may have been, but on November 2, just two days after the publication of the November issue of The Chronicle, the New York Times quoted Mrs. Jay's article and reported that the Metropolitan Opera board was discussing her demands. The following day, the Met announced that it would suspend performances of German opera and singers for the duration of the war. Otto H. Kahn, Chairman of the Board of Directors, refused to comment on the decision except to say that the vote had been unanimous. General manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza's statement expressed his views trenchantly: “I have no vote on the directorate board. Personally I have always held that reason and fairness should rule in these matters, but of course one must expect that at a time like this, emotion is a much stronger force than reason. My duty merely is to carry out the wishes of the directing board.”Footnote 25

Gatti-Casazza's contrast between reason and fairness, on the one hand, and emotion, on the other, gets at the essence of wartime propaganda. The preceding quotations from Fletcher illustrate how thoroughly he was imbued with the British propaganda literature that was circulating in the United States. Early in the war, as the United States maintained a steadfast commitment to neutrality, both the British and German governments had launched propaganda campaigns to influence American public opinion about the European war. Recognizing that the nine million Americans of German ancestry would constitute a crucial voting bloc in the event that the United States could be drawn into the conflict, the European adversaries were eager to influence public opinion in this neutral country that would eventually play such an important role in the war's final days. The Germans resolutely pursued a strategy of logical persuasion through public lectures and policy statements full of facts and figures illustrating the justifiability of the German position and urging Americans to form a dispassionate view of the issues at stake.Footnote 26 The British propagandists, on the other hand, recognized that Americans could be more easily swayed by emotion than by logic. Sir Gilbert Parker's team working out of London's Wellington House used innuendo and rumor to gain the sympathy of American readers. In the analysis of historian Stewart Halsey Ross, “When lies were called for, Parker lied glibly; and when atrocities were found to play well in the press, Parker created enormous German barbarities. Most important, Parker and his team at Wellington House went about their propaganda work quietly—so discreetly, in fact, that few in America, and until the end of the war only a handful even in Parliament, knew that the British government had a formal propaganda apparatus trained on the U.S.”Footnote 27 Among the most successful falsehoods circulated by British propagandists was the claim that German soldiers used civilians as a shield in battle. The notion of a Pan-Germanic quest for global domination was another rumor that was used to instill fear in the United States.Footnote 28

Riding their unexpected notoriety and relevance, Fletcher and his stable of well-connected authors spewed out an increasingly vitriolic stream of articles opposing German music and musicians. In December 1917, Fletcher claimed without supporting evidence that Mrs. Jay's November article was the reason that the Metropolitan Opera eliminated German works from its repertoire. He labeled Americans who objected to the Met's decision “broad-minded fools,” stating that “The elimination of German Opera and the dignified rebuke to Karl Muck has brought out a crop of idiots, very much as a heavy rain brings forth a myriad of angle-worms.”Footnote 29 In January 1918 he paralleled the Ring Cycle to rumored German military atrocities, claiming that recent events had clarified that Wagner's story was not a mythical legend of bygone ages, but was actually a potent analogy to current events. The same issue praised the citizens of Pittsburgh for banning German music and musicians. In February, an article detailed a shakeup in the New York Philharmonic Board, applauding the forced resignations of “the pacifist president, Oswald Garrison Villard, and the German treasurer, Rudolph E. F. Flinsch.” Fletcher went on to suggest that there had been a German-American conspiracy in this orchestra to deny Americans the privilege of hearing Russian music: “Only in recent years have we heard of such brilliant and consummate musicians as Rimsky-Korsakoff and Moussorsky [sic]. Why? The Germans would permit no rivalry for Wagner. They knew that the scientific and intellectual magnificence of Wagner would be dimmed by the pulsating, humanizing and sympathetic qualities of the Russians.”Footnote 30

In The Chronicle's March issue, Mrs. Jay renewed her call for the ouster of Muck in an article entitled “Doktor Muck Must Go.” She and several other New York women had written a public letter to Higginson demanding that he fire Muck. When he explained his reasons for standing by his conductor, she wrote a second, stronger letter accusing him of giving “aid and comfort to the enemy” by retaining Muck and challenged New York audiences to boycott the upcoming BSO concerts in their city. As in the past, Fletcher introduced Jay's comments with inflammatory language condemning the “odious cosmopolitanism” of New York audiences and claiming that “Doktor Karl Muck, by his unchanging pro-Germanism, has become a storm-centre no less than the fortified town of Cambrai.”Footnote 31 The April issue of The Chronicle, appearing just days after Muck's March 25 arrest in Boston, published five pages of gloating from prominent socialites under the headline “Doktor Muck Will Go.”

Between the articles attacking German music and musicians, the magazine also addressed other topics of interest to its distinctive readership. One of the recurring topics of editorials was the bohemian community of Greenwich Village. Fletcher characterized its residents as “idlers and poseurs,” noting with satisfaction the positive impact of the US entry into the war: “For the most part, these boys and girls awoke from their egoistic nightmare. They realized that there was something in the world beyond batik and incense and turquoise rings. The men changed their corduroys for the suit of honor. The women bent their energies to the Cause. The wheat and chaff were separated.”Footnote 32 Most of the articles were clearly opinion pieces, but some presented spurious facts under the guise of news, as when Mrs. George K. Collins reported that reading the German language was bad for one's eyesight and increased the need for eyeglasses.Footnote 33

Emboldened by the success of his campaign against Karl Muck, Fletcher turned his attention to other targets. An article in the May 1918 issue taunted Higginson and Boston patron Isabella Stewart Gardner (another staunch supporter of Muck even after his arrest) while also starting a whisper campaign of rumors against New York Philharmonic conductor Josef Stransky. By summer 1918, the journal was increasingly on the attack, with articles like “Taking the German Muse out of Music” (July), “Intern All German Music” by the tireless Mrs. Jay (August), and “There is Danger in German Music” by Cleveland Moffett (September). The October 1918 issue printed three pages of testimonials from musicians on why German music should be banned from stages in the United States under the headline “German Music is Interned.” These testimonials were elicited by letters from Fletcher to prominent performers in the United States that hinted at public shaming if they failed to declare their patriotism publicly.Footnote 34

As an illustration of the tactics of argumentation that pervade The Chronicle, Moffett's article lends itself to more thorough analysis. Cleveland Moffett (1863–1926) worked as a journalist early in his career, and he later gained renown as an author of short stories and plays. The biography before his Chronicle article credits him with active opposition to German propagandists before the United States entered the war. His short essay entitled “There is Danger in German Music” draws on the sensationalist techniques that were put to such effective use in British propaganda materials. The first paragraph strikes a polemical tone by ascribing an extreme position to his opponents. He then shoots down this “straw man” with an equally extreme counterargument:

Let us concede that German music is the finest music in the world—which it is not. Let us admit that Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Liszt, Strauss and all the rest of them are the greatest musicians the world has ever known or ever will know—which is an absurdity. All that being granted, I, nevertheless, maintain that we should drive German music out of America; from all homes, churches, theatres, concert halls, opera houses and other places where music is played, sung or produced.

After this confrontational opening, he admits that German music is beautiful, but he argues that its very beauty is what makes it dangerous. He asserts that rather than a “universal world treasure” that can be enjoyed by all, German music must be recognized by any American as a product of the German soul that cannot be separated from other aspects of German character:

The musicians of Germany speak with the soul of Germany, and out of the soul of Germany came the ravishing of Belgium, the sinking of the Lusitania. German music is beautiful—yes, but it tends to soften our hearts when we must harden them against compromise with evil: it has a sinister potency as German propaganda. There is danger to the Allies in German music.

He goes on to argue that any music composed or performed by a German, whether in the privacy of Americans’ homes or in public places, is an outrage against the mothers, wives, and sweethearts of Allied soldiers. Combining the age-old military tactic of dehumanizing the adversary with the logical fallacy of false equivalence, he concludes his short essay with an explicit call to action:

Am I preaching hatred of Germany?

Yes—for the present!

Germany wanted this war and prepared for it for years. Germany could have prevented this war even at the last moment, and did not. Why should we not hate Germany?

We must hate the Germans, just as we must use poison gas against them, and bombard their cities with long-distance guns and follow all their hellish methods of war efficiency.

Hate is a weapon!

“Lord forgive them not for they know what they are doing!” cries the French poet in the French hymn of hate.

I agree with him.Footnote 35

Moffett claims—as British propagandists did relentlessly throughout the war—that Germany wanted the war and chose not to prevent it, even though they could have done so. He then appeals to the emotions of readers by demanding retaliation. He justifies hatred and violence as retribution for the actions of the enemy. And knowing that his readers will never have the chance to fight in Europe, he urges them to boycott German music as their contribution to the war. Equating German music with German military atrocities is clearly an example of false equivalence, but in this time of war hysteria, the argument resonated with American readers.

An exchange of letters in the November 1918 issue between Mrs. Jay and Otto H. Kahn, president of the French-American Association of Musical Art and member of the board of directors of the Metropolitan Opera Company, brought the debate full circle. Just a year earlier, in November 1917, Mrs. Jay had advocated the elimination of German operas while acknowledging that German symphonic music of the Classical era posed no threat to American sensibilities. Now she took Kahn to task for refusing to condemn the orchestral music of Beethoven. He had pointed out that Beethoven was still performed in Paris and London during the war with no apparent conflict of interest, and he argued that “There is a very clear line of demarcation between the spirit of old and new Germany. The former is the enemy of the latter. We should recognize and encourage the former and destroy, as we are doing, the latter.” She countered that conditions were different in the United States, and that it was his duty to fight against German music here and also to use his position of influence to advocate against the performance of Beethoven by the orchestra of the Conservatoire National in Paris.Footnote 36 Later that month, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the Armistice took effect, and The Chronicle ceased publication.

The Chronicle had kept up a relentless attack on German music and musicians from November 1917 through its last issue in November 1918. Other newspapers also printed editorials against German music and musicians, but the persistence and virulence of Fletcher's attacks were unique. As noted in many of the studies of the Muck incident, the nation experienced a collective hysteria that fed on itself during the last year of the war. Fletcher helped fuel this hysteria by deriding newspaper editors for being insufficiently anti-German in articles entitled “The Reptile Press” (June 1918) and “Evening Post-Mortems” (August 1918). He argued against any moderation or impartiality in public discourse, calling on fellow editors to throw the full weight of their influence behind the war effort.

The renowned music critic W. J. Henderson (1855–1937) lamented the events of November 1917 in an article entitled “Rising Tide of Sentiment against German Music,” published in the New York Sun on Sunday, December 2, 1917. He suggested that the root of the problem stretched back years earlier, when arrogant German musicians openly celebrated the sinking of the Lusitania and attempted to sway the opinions of “stupid Yankees” to support the Central Powers (another oft-repeated rumor based on hearsay rather than evidence). He lamented that “the simple, devout soul of Sebastian Bach” and the universal beauty of Mozart and Haydn had been tainted by the machinations of enemy aliens. He applauded the directors of the Metropolitan Opera for eliminating German opera and the German singers who had been among the worst offenders of American values, but he regretted that the violinist Fritz Kreisler had been swept up in the hysteria: “It has been shown in no uncertain manner that this great artist is to suffer in most places for the sins of the propagandists, who have transformed the mildest of music lovers into determined foes of all things Teutonic.”Footnote 37

Henderson acknowledged that it was not the “blundering of the Boston Symphony Orchestra people” that had caused this hostility. Rather, “the explosion touched off by the Providence incident was of powder waiting for the touch of the match. Now the fire burns.” He astutely summarized the change in American attitudes that had transpired since the spring of 1917 and could not for the moment be reversed:

In short there are evidences that since the latter part of last season the entire situation has changed. At that time there was apparently no question as to the acceptability of the offerings of Teutonic musicians or the enjoyment of Teutonic musical compositions.

At this writing there is incontestably a deep feeling about it in the hearts of a large number of American-born people and it is impossible to foresee just how powerful the influence of this feeling may grow to be. But regrettable as it may be, there is ground for fear that sooner or later everything German in music will have to be temporarily retired and all the German interpreters or conductors permanently removed from the stage.

As to the fairness or justice of such a proceeding The Sun's musical recorder is not obliged to speak. It is most emphatically none of his business.Footnote 38

The Chronicle's virulent articles must be counted among “the sins of the propagandists” that Henderson laments. Despite a lifelong admiration for Wagner and a thorough professional familiarity with the range of German composers and performers to be heard in the concert life of New York, Henderson acknowledged that the climate in the country had changed and that nothing could presently be done about it. What he had no way of knowing in December 1917 was how far one of Fletcher's most ardent authors would go to expand her anti-German campaign beyond the pages of The Chronicle.

Mrs. William Jay and her Campaign against German Music

Fletcher's most active contributor was Lucie Jay (1854–1931), the wealthy widow whose first published article played a role in banning German-language opera at the Met. Her husband, William Jay (1841–1915), came from a distinguished line of American statesmen. His great-grandfather, John Jay (1745–1829), was one of the most prominent of the founding fathers as a signer of the Declaration of Independence, co-author of the Federalist Papers, first chief justice of the United States, and later governor of New York. His grandfather, William Jay (1789–1858), was a judge and a prominent abolitionist whose writings were influential in shaping public opinion before the Civil War. His father, John Jay (1817–1894), was a lawyer who argued several important anti-slavery cases and was appointed US Minister to the Austro-Hungarian Empire after the Civil War. William was also a lawyer who served as a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War (reportedly in the same regiment as Henry Lee Higginson) and was later a vice president of the New York Herald as well as an avid horseman. In contrast to her husband, Lucie was the daughter of a wealthy German immigrant, Henry Oelrichs, partner in a Baltimore shipping firm with ties to Bremen in North Germany.Footnote 39 Her father's wealth allowed her to study in Europe and become friends with members of the New York elite, including Charles McKim, who went on to become one of the country's leading architects. Mr. and Mrs. Jay traveled often to Europe, and in fact they were there when war broke out in 1914. By the time the United States entered World War I three years later, Mrs. Jay had been preceded in death by her husband and two of her three daughters; the other daughter had been married since 1904 to textile merchant Arthur Iselin.Footnote 40

Starting in late 1917, the recently widowed Mrs. Jay threw herself into the campaign against German music with remarkable zeal.Footnote 41 After establishing her reputation with articles in The Chronicle, she began sending letters to the editors of New York's daily newspapers, where her strong views and colorful prose became a memorable feature of wartime journalism. Her letters often seemed to defy reason, as when she refused to let the Muck case rest, even after the orchestra added the anthem to all of its concerts and the management defended the conductor against charges of disloyalty.

When the BSO was scheduled to return to New York for the season's final series of three concerts in March 1918 (four and a half months after the Providence incident), Mrs. Jay led a vigorous campaign to bar the orchestra from performing, aided by extensive articles in the notoriously sensationalist New York Herald, her husband's former employer. She questioned Muck's motives with the statement, “It is beyond me, that any sensitive musician can persist in the face of the righteous indignation of Americans, to thrust himself before their presence unless he were actuated by some deeper motive than merely earning his living.”Footnote 42 Muck's first concert in Carnegie Hall on March 14 was sold out, and the crowd applauded enthusiastically after he played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” A squad of policemen that had been provided to maintain order in case of protests proved unnecessary. Mrs. Jay released a statement condemning those who attended and vowing to keep up her fight, while the BSO management refused to comment.Footnote 43 The following night's audience in Brooklyn on March 15 was again cordial, but Mrs. Jay renewed her personal attack: “I have the greatest respect for a pro-American German, as I have the greatest contempt for a pro-German Swiss. I believe I am expressing a truly American sentiment when I say a man should be judged by the feelings in his heart and not by the papers in his pocket.”Footnote 44 Though Muck had been born in Darmstadt, Germany, he was a citizen of Switzerland, as his father had been. Mrs. Jay was repeating rumors that his true loyalties lay with the Kaiser rather than with the country of his citizenship, which may well have been true. However, her assertion that “the feelings in his heart” mattered more than his legal status flies in the face of US law. She invited subscribers to boycott the next day's matinee in Carnegie Hall and to send their tickets to her in order to protest their disapproval with empty seats.Footnote 45

For the final concert of the series on the afternoon of March 16, Mrs. Jay resorted to a theatrical stunt. She brought seven blind children with flags pinned to their chests into the concert (presumably using tickets sent to her in response to her letter of the previous day), stating that “only those who could properly listen to the beautiful music of the orchestra were those who could not see the face of the Kaiser's friend.”Footnote 46 After this inflammatory tactic, the Herald reported: “Richard Fletcher, representing Mrs. Jay, said last night that the leader of the agitation against the man who at one time played for the Kaiser has received a large number of abusive and threatening letters. The latter, he said, have been turned over to the proper authorities.”Footnote 47 This statement clarifies Fletcher's ongoing connection with Jay, but it gives no clue as to the extent of his role in instigating her behavior. Her public relations campaign surrounding the New York concerts was followed nine days later by Muck's arrest in Boston on Federal charges. Agents of the Bureau of Investigation had been probing his activities for months and finally determined that they had sufficient evidence to take the conductor into custody. He spent the remainder of the war interned at Camp Oglethorpe in Georgia before being allowed to return to Germany on August 21, 1919.Footnote 48

With Muck behind bars in late March, Mrs. Jay turned her attention to Josef Stransky of the New York Philharmonic. She resigned her position on the Philharmonic board in April 1918 (the month after Muck's internment) and announced her intention to bring down Stransky.Footnote 49 During the next year, she continued to attack Stransky in The Chronicle and other papers. He proved a more difficult adversary, in part because his nationality was Czech rather than German, but primarily because he had performed “The Star-Spangled Banner” consistently since the beginning of the season. By the end of the war, the popular conductor retained the firm support of the board from which Mrs. Jay had resigned. A similar attack on conductor Walter Damrosch of the New York Symphony Orchestra in The Chronicle's November 1918 issue did not succeed in denting his career either. Fletcher and Jay's efforts were aimed at East Coast musicians, and they did not to my knowledge join the attacks on Frederick Stock of the Chicago Symphony or Ernst Kunwald of the Cincinnati Symphony.

Mrs. Jay's most visible work for the remainder of 1918 and the first half of 1919 was her continued campaign to root out enemies of the United States and to eradicate all German music from concert programs. In April 1918 she formed an “Intimate Committee for the Severance of All Social and Professional Relations with Enemy Sympathizers,” whose public protests against a curious array of targets were reported nationwide. The committee's first campaign was launched against the Irish Progressive League, which she alleged was “for the purpose of stirring up trouble for England, and would, therefore, be pro-German in its results.”Footnote 50 For the remainder of 1918, the committee directed its attention primarily against “disloyal newspapers” published by William Randolph Hearst.Footnote 51

In the months after the Armistice, she continued to protest the performance of German music, and in March 1919 she founded an “Anti-German Music League.” In statements to the press at this time, she expressed the view that German music was such an insidious form of cultural poison that it should not be tolerated in any form: “Realizing the persistence of German music propaganda which is increasing alarmingly, I pledge myself to boycott all concerts, artists and institutions which continue the exploitation of German music and German kultur before the world is assured of Germany's reformation and repentance. Why make any limitations? If we eliminate some, why not all? This is not a fight against particular German composers. What we are opposed to is the peculiar methods they employ to poison America and gain her sympathy.”Footnote 52 In protest against several planned concerts of German music in April 1919, she accused the performers of attempting “to inculcate the Germanic spirit in the souls of young persons of German extraction and also to prolong the Germanism of natives of the Fatherland.” She ominously added that the feelings of returning American soldiers and sailors were so strong that anyone attending concerts of German music did so “at great personal risk.”Footnote 53 Her threats and arguments did not achieve her desired result, as the planned concerts went ahead without incident.

Among musicians, Lucie Jay's incessant attacks did not go unnoticed. Although her denunciation of Walter Damrosch in November 1918 did little to damage his reputation, he recalled her efforts bitterly in his 1923 memoir: “There was in New York a small but noisy group led by a few women who sought to demonstrate their ‘patriotism’ by hysterical outbursts and newspaper protests against the performance of all music composed by Germans, no matter how many years ago. Some of these women, through the curious psychosis of war, really thought that they were serving their country by their protests.”Footnote 54 In October 1918, columnist Frederick Donaghey of the Chicago Tribune wrote, “The Metropolitan discarded its Wagner repertoire last year because of the fuss kicked up by a bloodthirsty lady, Mrs. Jay, who then established a paper, The Chronicle, in which to carry on against Dr. Muck, Mr. Stransky, and others who fell within her facile capacity for suspicion.”Footnote 55 Fletcher responded to the Tribune that the magazine had been in operation for nine months before she began writing for it, but he did not deny the assertion that anti-German sentiment was stronger in the East than in the Midwest.

American pianist Olga Samaroff made the strongest counterargument to Jay's growing campaign against German music. Samaroff's husband Leopold Stokowski—along with other prominent performers—received a letter from Fletcher dated August 12, 1918 asking for his testimonial against German music. The letter included a copy of Jay's article in that month's issue of The Chronicle entitled “Intern all German Music” with the request that he write a statement for publication in the next issue. Samaroff sent Fletcher's letter to her friend Col. Edward Mandell House, President Woodrow Wilson's advisor, along with a nine-page letter asking for his help in dealing with Jay and Fletcher. She outlined her views on the importance of German music to American audiences and music students, and she described how British and French performers had briefly eliminated German music from their programs early in the war but had since moderated their views. She went on to describe a piano student from a poor family in Texas whose parents were making sacrifices to allow her one year of study in New York in order to hear concerts and learn from great performers. Samaroff urged House to consider that,

If Mrs. Jay has her way, not only this student but thousands of others will be placed in the position of students of English literature who were suddenly deprived of Shakespeare, Milton, Carlysle and Thackeray. I cannot help feeling that President Wilson, and he alone, if he could devote to this matter a few of the wise and eloquent words with which he has guided us in other things (such as his magnificent speech on lynching)Footnote 56 could free the performance of the great classical composers from the taint of Germanism by calling to the mind of the people the very true fact that they do not in any way belong to the Germany of to-day. This fact once established their performance could not be used by propagandists and a great art treasure would be saved to us.Footnote 57

Samaroff received a positive response from House, who was currently hosting President Wilson at his summer home. According to her autobiography, she and her friend Clara Clemens Gabrilowitsch (daughter of Mark Twain and wife of another prominent pianist and conductor) met with President Wilson and his advisor House to secure a statement from the president decrying this form of extremism.Footnote 58 Whether or not the personal meeting took place, Stokowski declined to participate in Mrs. Jay's “forum.”

Jay's notoriety as an opponent of all things German made her abrupt about-face in June 1919 a surprise. Since late May, she had been uncharacteristically silent, and on June 28, 1919, the date when Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles agreeing to war reparations and other conditions of surrender, Mrs. Jay sent a letter to news outlets announcing her withdrawal from the campaign. The text of her statement, as printed in the New York Times, read as follows:

To the Editor of The New York Times:

Peace has come at last! Germany is on her knees before outraged but forgiving humanity. Since our entry into the world war I have stood firmly and consistently against the performances of German opera, German plays, and German music. The committee and league which I founded uncovered ample evidence that German propaganda lurked in these apparently harmless entertainments, while victory was in the laps of the gods and a “soft” peace was a remote and unfair possibility.

Now all is changed. No further protests against the German productions, whenever and wherever given in the United States, will come from me, for I know that henceforth materialism will weigh too heavily against a pro-German attitude, and I pray that the former friends of German Kultur will uphold the principles of freedom, honesty, and justice, which they now see triumphant and everlasting.

LUCIE JAY (MRS. WILLIAM JAY.)

New York, June 28, 1919.Footnote 59

After twenty months of relentless campaigning during which her name became synonymous with uncompromising opposition to all aspects of German culture, Lucie Jay nonchalantly withdrew from the field of rhetorical battle. The New York Times printed her letter without comment, but other editors were frankly incredulous, as reflected by the commentary of the Wichita Daily Eagle: “A mimeographed letter marked ‘not to be published until the signing of peace treaty’ has been sent to the press by Mrs. William Jay, a New York woman, creator of the League-Opposed-to-Everything-German, who brought herself into the limelight during the war by her newspaper attacks on Beethoven, Wagner and other German masters, living and dead. In addition to her violent assaults on all forms of ‘enemy alien art,’ Mrs. Jay was interested in an ‘exclusive’ society publication, the Chronicle, in which monthly she published her opinions. The Chronicle suspended publication many months ago.”Footnote 60 Upon her death in January 1931, the New York Times devoted a significant portion of its obituary to her campaign against German music in the World War, the best-known episode of an otherwise quiet life in New York's high society.Footnote 61

Richard Fletcher (a.k.a. Fechheimer), Editor of The Chronicle

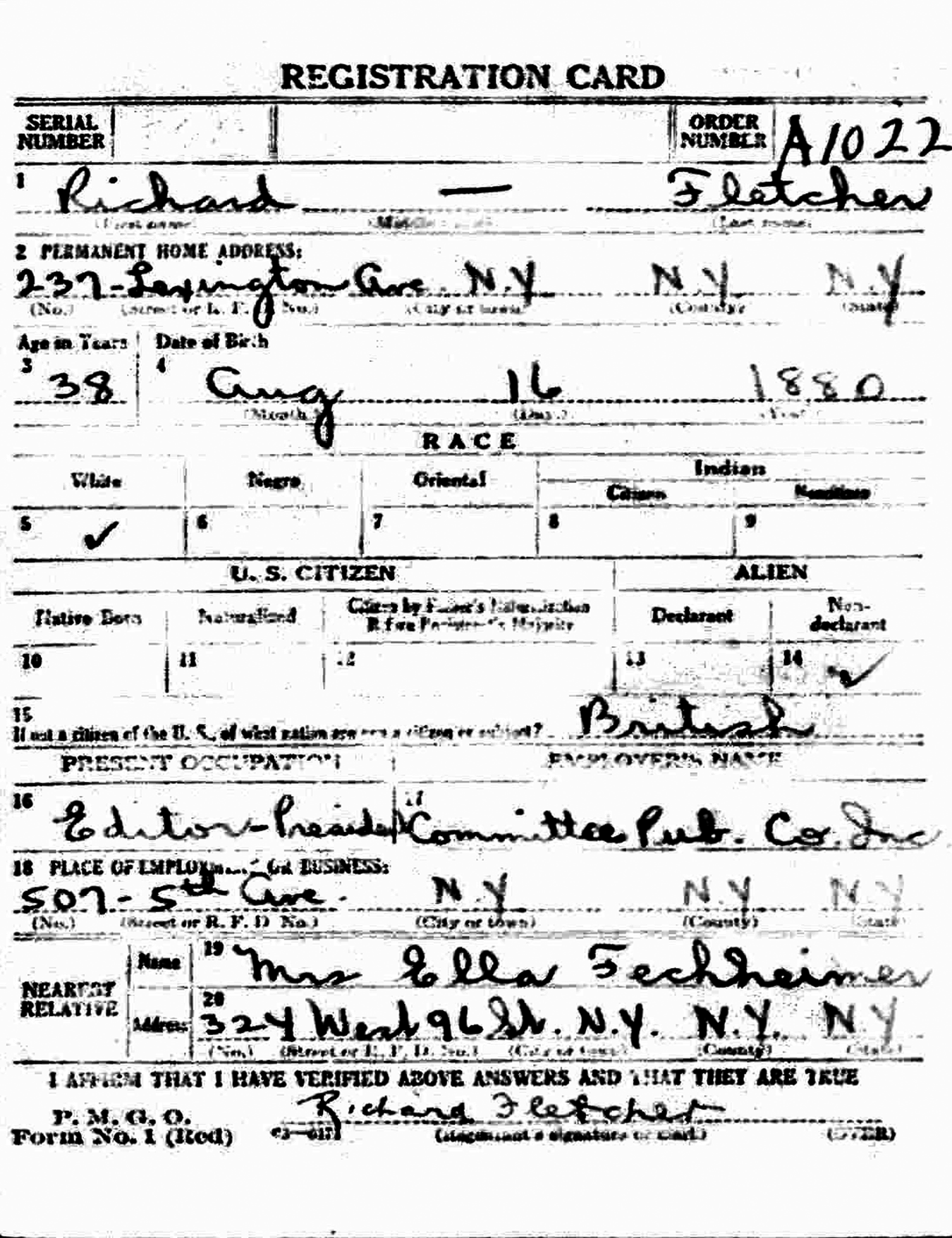

Behind the scenes of the movement to eliminate German influence on music was the editor of The Chronicle, Richard Fletcher, whose name is so common that it creates a challenge for researchers wishing to learn more about his background. Like Smith or Jones, the name “Fletcher” is shared by so many persons on both sides of the Atlantic that it afforded its owner a cloak of anonymity. The Rosetta Stone for unlocking Fletcher's identity proved to be the registration card he filled out for the Selective Service in September 1918 (Figure 3). His occupation as Editor-Publisher of the Committee Publishing Company at 507 Fifth Avenue marked him as the right man, but it was unclear why a thirty-eight-year-old British citizen would register for the draft. The answer was found in the person he listed as his nearest relative, Mrs. Ella Fechheimer, who turned out to be his mother. With this decidedly uncommon name, it is possible to reconstruct Fletcher's personal history.Footnote 62

Figure 3. Selective Service registration card for Richard Fletcher (a.k.a. Fechheimer). Registration State: New York; Registration County: New York; Roll: 1766146; Draft Board: 123.

Richard Fechheimer was born in Cincinnati on August 16, 1880, to a family of German Jewish ancestry. His father was a partner in a successful family clothing business when Richard was a child, but after the business failed in the late 1890s, the family left Ohio. The 1900 US census found them in Colorado Springs, and the 1905 New York census showed them living in Brooklyn. By this time, Richard Fechheimer was working, listing his occupation as “newspaperman.” After the death of his father in February 1906, Fechheimer moved away from home, trying his hand as a press agent and theatrical manager. He served as press agent for a North American tour by the British theatrical star Mrs. Patrick Campbell, who later played the original Eliza Doolittle in the 1914 London premiere of George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion. Fechheimer's work in organizing a benefit concert for earthquake victims in 1909 was highly praised by the Philadelphia Inquirer.Footnote 63 The 1910 US census lists him as a writer, living as a boarder with a young married couple on Fifth Avenue in New York.

A year later, the footloose man was living in London, now calling himself Fletcher, and listing his occupation in the 1911 Census of England and Wales as “writer and journalist.” He became a naturalized British citizen in February 1915, adding “playwright” to his list of occupations. His oath of allegiance reads, “I, Richard Fletcher, swear by Almighty God that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to His Majesty, King George the Fifth, His Heirs and Successors, according to law.”Footnote 64 Less than two months later, on April 4, 1915, he enlisted as a “Temporary 2nd Lieutenant” in the British Army, resigning his commission three months later on July 23, 1915 owing to ill health. In September 1915, he sailed back to the United States, where a year and a half later, he became editor of The Chronicle.

The peripatetic career of this writer is an interesting historical backdrop to the influential role he played as editor of The Chronicle. Declassified files in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland confirm that his background was more than interesting—it was also suspicious. Both the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation (the precursor to the FBI) and the recently established Military Intelligence Section opened investigative files on Fletcher and The Chronicle shortly after its inception in 1917. Their interest had little to do with music, as federal agents investigated not only the material published in the pages of The Chronicle, but also the actions of its editor behind the scenes.

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, it had no military intelligence organization. It took a month of strategic lobbying before Major Ralph Van Deman convinced the War Department that it would be worthwhile to establish its own intelligence corps rather than simply rely on the British and French for all its intelligence needs. During the summer of 1917, Van Deman laid the foundations of a workable intelligence network using the extremely limited staff that he was allotted. By creative personnel management and the help of civilian groups like the American Protective League, Van Deman gradually built his fledgling Military Intelligence Section (MIS) into a formidable counterintelligence operation. In his efforts to identify potential threats in the United States, Van Deman worked closely with the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation (BOI), sharing information and occasionally pursuing independent investigations on the same suspect.Footnote 65

Fletcher first came to the attention of the BOI in connection with the letter he used in August 1917 to solicit the above-mentioned comments from German Americans for the article “America First and the German-Born.” Addressed to 200 selected recipients, it read:

We are addressing the leading persons of German birth in this country with the request that they take this opportunity of affirming or re-affirming their allegiance to the United States. Therefore, without wishing to inconvenience you, we do ask that you write in the space below whatever sentiments you care to express. THE CHRONICLE is a journal of opinion with a breadth of view and we hope you will agree that it is a fitting medium for an exchange of mind of just such an international character. In the absence of a response from you, we shall conclude that your attitude toward the entrance of the United States in the war is one of negation or disapproval. Therefore, an early reply would be mutually desirable.Footnote 66

The Justice Department received complaints from German-American recipients of the letter who felt pressured to respond and were concerned that their responses might be used to shame them publicly. (As noted previously, the October issue would eventually contain over fifty responses to the initial 200 letters.) An agent interviewed the magazine's staff in September, after which Fletcher provided a list of the persons contacted, along with their responses. Under questioning by Assistant US Attorney Harold A. Content, Fletcher explained that his motives were “honorable and patriotic.” His statement continued, “Rather to give prominent men and a few celebrated women a chance to praise the action of the United States than to confound the pro-German still lurking in the mental caves of black Prussianism actuated the Chronicle letter, which brought forth these interesting replies.”Footnote 67 He turned over copies of all the responses he had received, both positive and negative, and he agreed not to publish any negative responses. On the basis of this interview, Content was able to compile a list of German Americans who, though not strictly treasonous, were unwilling to endorse the US entry into World War I. Among the ten negative responses to Fletcher's initial mailing of two hundred letters were the well-known German-American editor George Sylvester Viereck, the musician John Orth of Boston, and the lawyer Theodore Sutro, uncle of the duo piano team Rose and Ottilie Sutro. After the interview, the Assistant US Attorney characterized Fletcher as “an infernal ass, but perfectly harmless.”Footnote 68

The intelligence files from MIS and BOI contain no new documents between September 1917 and April 1918. If investigators were watching Fletcher and The Chronicle, they would have seen only a series of strongly pro-Ally editorials and news reports. Whether his campaign against German musicians was an effort on Fletcher's part to reassure the government, or whether it was a manifestation of the nationwide war hysteria, there could be no questioning the magazine's loyalty between the elimination of German opera at the Met in early November 1917 and the arrest of Karl Muck in late March 1918.

By the spring of 1918, allegations against Fletcher were growing more serious. The chief of the BOI, Bruce Bielaski, shared what he knew in a memo to the head of Military Intelligence, Ralph Van Deman, dated April 24, 1918, and requested that Van Deman ask British Intelligence what they knew about Fletcher. Bielaski's summary stated in part, “He changed his name [from Fechheimer] to Fletcher; went to England and spoke very disparagingly of this country, saying that he never desired to return; entered the British Army and was discharged therefrom (it has been said dishonorably, but information as to the manner of his discharge is not definite). He has been engaged in efforts to sell worthless stock on one occasion and it is believed that he is using The Chronicle as a cloak to cover some form of blackmail.”Footnote 69 A report dated May 3, 1918 from William Gilman Low Jr., the liaison official between the YMCA War Work Council and the Military Intelligence Branch, communicated a complaint against Fletcher by Henry E. Cooper, a Wall Street banker who served as treasurer of the New York Philharmonic. It included the statement: “It is understood that [Fletcher] left Great Britain for reasons which he does not disclose but are believed to be of a seriously immoral character. He is reported to have secured a considerable amount of influence over a woman of high standing in this community, Mrs. William Jay, widow of Colonel William Jay, and it is not known precisely what his object is in utilising her influence.”Footnote 70

In the face of these accusations, Van Deman consulted Lieutenant Colonel Hercules Pakenham, the British liaison officer to the American Military Intelligence Branch. His response downplayed the threat: “I heard about this man a few days ago, and what I heard was not so bad as is shown in this letter. … He is the proprietor and editor of the Chronicle, a publication run on subscription among his friends and backers, with a very small circulation. He is not flush of money and is a nuisance to people who have once helped him, as he pursues them. I do not think from what I heard that the man is dangerous from a National point of view, in fact he is very keen on a sort of amateur detective work, I could probably get more about him if the information is wanted.”Footnote 71 Pakenham's response is surprisingly cavalier, considering that it concerned a British citizen working in the United States during wartime.

American investigators, though, grew increasingly interested. By late May 1918, investigators in the Bureau of Investigation learned that Fletcher was circulating another letter, this time claiming to have assisted the Department of Justice and the Military Intelligence Section. The audacious attempt to boost circulation included the statement:

As an organ of American propaganda, The Chronicle has performed genuine service and has assisted both the Department of Justice and the Military Intelligence Department by its operations in exterminating the evil of the “enemy within.” Most important of these achievements was the successful campaign against the pro-German Doktor Muck, which began last October and culminated in the German sympathizer's arrest and internment. So it will be seen that, apart from the entertaining and informative services of The Chronicle, there is the more valuable effort toward—“Winning the War.”Footnote 72

Fletcher implies in this statement that his campaign against Muck led to the conductor's arrest and internment. While it is undoubtedly true that Fletcher and Mrs. Jay contributed to public resentment of Muck through their campaign, his arrest was the result of months of investigative work by agents of the federal government. His letter goes on to list the prominent men and women who had contributed articles to the magazine, stating that their contributions “give unimpeachable evidence of its integrity and prestige.” The last paragraph of the letter reinforces Fletcher's claim to exclusivity:

The Chronicle is published on the first day of every month for subscribers only and is printed on hand-made paper, of which there is an adequate stock on hand. It is interesting and reassuring to know that the money spent on this beautiful paper goes to our Italian Allies, in reality to those in the Venetian Province. By giving your support, through your subscription to the movement, which The Chronicle reflects and directs, you will be helping in the enormous work for this country's preservation as well as for the fostering of American ideals and American art.Footnote 73

The fallacious claims in Fletcher's latest letter led to another visit from BOI agent J. M. Bischoff on June 8, when Fletcher was ordered to desist from calling himself a government informant and using this for commercial benefit. He was also challenged in regard to the statement in the subscription letter claiming that his use of Italian paper aided the Allies in Europe. Under intense questioning, Fletcher admitted that not all copies of the magazine were printed on the handmade Italian paper owing to a shortage of supplies. He further admitted that the money paid by The Chronicle to purchase the paper from his Baltimore printer was not in fact aiding the Italian war effort but was simply going to an Italian firm. Agent Bischoff summarized his lengthy report with an acknowledgment of the ambiguity of Fletcher's position: “In the opinion of the writer the June number of The Chronicle, which was read carefully, has some very fine articles in support of the Allies and also a glowing tribute to our President, Woodrow Wilson, but the business methods which Mr. Fletcher adopts in securing subscribers for his paper are misleading and I believe that this matter should be called to the attention of the postal authorities.”Footnote 74 In response to Bischoff's recommendation, Chief Bielaski urged his agents to refocus their investigation on mail fraud in connection with the false claims about paper. He referred the matter to the Post Office Inspector with the opinion, “Fletcher seems clearly to be crooked.”Footnote 75

Also in June, the Military Intelligence Division continued to receive reports about Fletcher and his magazine. A follow-up interview in early June with Henry Cooper, the Wall Street banker who served as treasurer of the New York Philharmonic, included this secondhand report: “MR. COOPER said that a friend of his had been told by a MR. KARL FREUND that RICHARD FLETCHER, alias FECHTHEIMER [sic], editor of ‘The Chronicle,’ a society journal published in New York, was engaged in vicious, perverse and degenerate practices with young sailors and soldiers.”Footnote 76 This memo was forwarded to Chief Van Deman as well as to Captain T. N. Pfeiffer in New York for further investigation.Footnote 77

Shaken by these latest interviews, Fletcher responded with an unusual tactic. He published an article in the July issue of The Chronicle opining that the fine men of the investigative branches of government were “underpaid disgracefully,” and recommending that their pay be at least doubled. This thinly disguised offer of bribery was brought to the attention of the Chief of the Bureau in a memo of July 5 marked “Personal and Confidential”: “Did you note the editorial in the July 1918 number of the ‘Chronicle,’ denouncing alleged failure of the Government to pay proper compensation to Special Agents of the Department of Justice and the United States Secret Service?”Footnote 78 In addition to a copy of the article in question, Agent DeWoody included a copy of the article entitled “Taking the German Muse Out of Music” from the same issue of The Chronicle.

As investigators of both agencies closed in on the editor, they focused increasingly on his financial dealings. A memo of July 23 to Chief Van Deman reported, “A statement was made to me by an officer who has known this man for some years, that he believes this publication to be a blind, and that the connections obtained through it are used to obtain information. Fechheimer was absolutely without money when he started this journal, and is well supplied with cash at present, although the profits from a publication of such a character could hardly be expected to amount to very much in the short time that the paper has existed.”Footnote 79 A detailed report submitted on August 1, 1918 by agents of the American Protective League (APL), a volunteer organization devoted to supporting the work of the Military Intelligence Division, gave further specifics about the financial status of the magazine. This report noted that the annual rent on the Fifth Avenue editorial office was $1,080, and that the average balance in the magazine's bank account was $7,000. An officer from Fletcher's bank informed the APL investigator that the “subject stated he was backed by Harry Payne Whitney and others, and showed bank investigator letters from various prominent people.” When Whitney's secretary was asked about this statement, he revealed that “Mr. Whitney has never seen Fletcher to his knowledge nor does he remember ever having seen a copy of the Chronicle, nor has he ever heard of Fletcher.”Footnote 80

During the investigations of spring and summer 1918, American intelligence again contacted British intelligence, who again downplayed the threat posed by Fletcher's activities. General Grant of the British Commission offered to contact London to find out whether Fletcher had been dishonorably discharged from the military, but he warned that it would take at least three months to get an answer.Footnote 81 The files contain no follow-up to this inquiry, as the Armistice occurred three months later.

The most interesting British document in the military intelligence files was a report by Major Norman Thwaites of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), who was involved in clandestine counterintelligence work in New York during the war.Footnote 82 Thwaites was fluent in German and was a long-time reporter on the New York World, where he served as personal secretary to editor Joseph Pulitzer. He served briefly in the British army in 1914 but was discharged after being wounded. A perceptive writer whose fluency in German, familiarity with New York, and uncanny memory for people made him useful as an intelligence agent, Thwaites spent much of the war in New York. His memoir, published in 1932, is devoted primarily to his own combat experience early in the war and to his more sensational efforts to foil bomb plots by German spies and to discredit German diplomats in the United States, but he gives a telling comment about the efforts of his team in New York: “We representatives of Great Britain relied largely upon our memories when engaged in intelligence work, keeping few notes and no diaries.”Footnote 83 Though the British intelligence officers maintained cordial relations with their American counterparts, the clandestine nature of their mission is confirmed by a September 1918 memo from Thwaites’ commanding officer, Sir William Wiseman, to his own supervisor stating that “The details and extent of our organization [the US authorities] have never known, and don't know to this day.”Footnote 84 When the Americans asked the British for information on Fletcher, Thwaites provided a report with just the right balance of hearsay and innuendo:

The above-named man has been known to me for some ten years. When I first met him he was a reporter on the New York World doing Society Gossip. On the death of his father, or soon after, he changed his name from Richard Fechheimer to Richard Fletcher, and was engaged by Mrs. Patrick Campbell as a sort of Press Agent for her tour in America. I think he has been Press Agent for several theatrical stars. I next met him in London, where he developed his already noticeable British accent and continued Society contributions for the papers. On the outbreak of the war he joined the British Forces, and, unless I am very much mistaken, I saw him at the Carlton Hotel in London in uniform. Later on I saw him in mufti [civilian clothes], and he told me that he had been invalided out of the Service on account of poor heart action. He took out naturalization papers, and is now a British subject, unless he has changed back again to American citizenship. His mother and sisters are very nice people. He returned to this country about a year ago [sic] and got up several benefits for Allied Charities by means of his theatrical affiliations,Footnote 85 and is now engaged in publishing a paper known as the Chronicle, which is a literary paper, for which he gets contributions unpaid by Society ladies, debutantes, and others. It is an amusing rag. I have never heard a suggestion that he was anything but heart and soul pro-Ally, although there are persons who suspect his private life has not been quite wholesome. I believe he owes a good deal of money here, and he is a person who is chronically hard up. Some months ago he was in the moving picture business, when he represented Christ in some film. For this purpose he grew a beard, which enabled him, I am told, to “duck” some of his creditors.Footnote 86

The picture of Fletcher that Thwaites paints for his American counterparts is of a somewhat bumbling ne'er-do-well. He has trouble managing money, but he is basically harmless. He is “heart and soul pro-Ally,” even if he does not pay the contributors to his “amusing rag.” His mother and sisters are “very nice,” although census records list only a younger brother and no sisters. Like several previous informants, Thwaites drops a hint about Fletcher's private life, but without corroboration or details. Ending the report with the anecdote about ducking his creditors by growing a beard for a movie role (for which I have found no evidence whatsoever) is brilliant, as it makes Fletcher seem harmless and self-serving rather than nefarious.

This assurance from British Intelligence seems to have prompted American Military Intelligence to let the matter rest, as there are no more documents in Fletcher's personnel file after this one. The Bureau of Investigation files include just two items: a clipping from September 1918 in which Fletcher calls for greater recognition of the role played by newspapermen in combatting German propaganda, and one more communication from Fletcher, who in December 1918 (a month after the Armistice and the discontinuation of his magazine) wrote to Bielaski denouncing conductor Josef Stransky of the New York Philharmonic. The Chronicle ceased publication after the November 1918 issue, and there is no indication that either of the intelligence agencies pursued any further inquiries into this quirky editor. After his magazine was discontinued, Fletcher remained in the United States until May 1919, when he sailed on the Cunard liner “Royal George” arriving in Liverpool on May 30. The thirty-eight-year-old passenger listed his occupation as “author” and his destination as the Berkeley Hotel in London. The death of his mother Ella Fechheimer on June 4, 1919 was less than a week after his arrival in England, but he did not return to the United States in response to the news.

Follow the Money

The intelligence files make it possible to reconstruct the chain of events that allowed an obscure Ohio-born press agent to play such a vital role in the conversation about classical music in the United States during World War I, but the shadowy nature of The Chronicle and its readership leave some questions unanswered. Although the intelligence files provide extensive details on Richard Fletcher's business activities, they do not provide a convincing explanation of his motives, nor do they explain how Fletcher was able to start his magazine. These require a certain amount of speculation to fill in the missing pieces of the puzzle. The persistent theme through all the intelligence documents is money and its role in financing The Chronicle's publication. By following the money, we can posit two different—but not mutually exclusive—hypotheses about this journal and its influence on American musical attitudes during the First World War.

Hypothesis No. 1: Fletcher as Con Man. According to Norman Thwaites, Richard Fletcher was forced to leave England because of debts he could not pay. In this scenario, he arrived penniless in New York in September 1915 but immediately set about bettering his situation. Impressing those he met with his distinct British accent and his unflagging patriotism, he was able to win supporters for his proposed magazine. James W. Pennock Jr., the former traveling salesman, supplied the initial funding for The Chronicle, allowing Fletcher to use it as a springboard for a variety of ancillary activities. His letter to prominent German Americans in the summer of 1917 shows how he used insinuation to pressure his victims into a response. Like all con artists, he targeted the vulnerable. Although there were nine million German Americans in the United States, those who were wealthy Easterners stood to lose the most if they came under suspicion because of their ethnic background. The possibility of blackmailing this vulnerable group explains why Fletcher sent his letter to that slice of the American populace. It also explains why there were so many wealthy widows among his readers. Lucie Jay is a perfect example of the type of person who would be susceptible to his coercion: she was recently widowed with no children at home, she had enjoyed the benefits of her husband's wealth and Revolutionary War heritage for many years, and her German ancestry made her susceptible to ostracism as the war hysteria grew.

The complaints and subsequent investigation into that initial letter put Fletcher on the defensive. Knowing that he was under suspicion for blackmail, he needed to find a way to make it more difficult for the authorities to cause him trouble. His answer was to launch a vigorous patriotic campaign against all things German. As Agent Bischoff noted in his report from summer 1918, the magazine contained much patriotic material in support of the Allied cause, despite the editor's shady business dealings. This tactic provided cover for his continued contact with wealthy socialites (and their bank accounts). Several informants hinted that the magazine was being used as a cover for some form of blackmail, which may have been to extort money from subscribers, or it may simply have been to convince them to write more virulent articles to support his cover. I believe it is more than a coincidence that Jay continued her relentless campaign against all forms of German music for six months after the Armistice, but that she suddenly went silent and renounced the campaign when Fletcher sailed to England.