One day I was introduced to Oscar Fischinger who made abstract films quite precisely articulated on pieces of traditional music. When I was introduced to him, he began to talk with me about the spirit which is inside each of the objects of this world. So, he told me, all we need to do to liberate that spirit is to brush past the object, and to draw forth its sound. That's the idea which led me to percussion.

—John Cage, interview with Daniel Charles, 1968.Footnote 1I have become convinced that percussion and the use of mechanical instruments are a transition to the electrical music of the future. With electrical means and with film means composers will have the entire field of sound available for musical purposes.

—John Cage, “Brief History of this Field of Music,” ca. 1940.Footnote 2In the summer of 1937 the young John Cage arrived at Oskar Fischinger's temporary animation studio in Hollywood, recently hired as the filmmaker's assistant. Cage's brief apprenticeship—by all accounts lasting no more than a few days—soon became a recurring subject in the composer's personal history, retold in interviews and articles.Footnote 3 It is well known that Cage composed his first works for percussion around the same time as his interaction with Fischinger, leading critics, scholars, and artists to speculate on the implications of Cage's claim that his time with the filmmaker “led me to percussion.” Although eureka moments make for excellent memoirs—and Cage's biography is full of such examples—determining any direct lineage or influence for Cage's intellectual or compositional breakthroughs is difficult, given his proclivity for colorful personal narrative that both simplified and obscured the complex web of influences that shaped his career.Footnote 4

Recent scholarship on Cage's early career has made great strides in clarifying dates, contacts, and source materials in an effort to contextualize his work within the blossoming and diverse artistic culture of Los Angeles and the West Coast in general.Footnote 5 Continuing this trend, this article explores recently unearthed archival documentation that clarifies many details of Cage's relationship to Fischinger, and in turn reveals Cage's involvement with contemporary developments in music synthesis and recording technologies for film and other media.Footnote 6 Cage's understanding of these technologies was fostered by a heretofore unacknowledged aspect of his early career: research he undertook for his father, John Cage, Sr., on a series of patents in television and infrared vision technology. Although others writing on Cage's relationship with his father have explored the notion of “invention” as a metaphor for the composer's artistic program in general, this article provides the first documented evidence of Cage Jr.'s understanding of electronic technology and its practical implications in composition.Footnote 7

Cage's connection with Fischinger furthermore highlights the relationship between West Coast composers and the burgeoning entertainment and electronics industries in California. Throughout this period, roughly spanning the introduction of sound film technology in the late 1920s and the consolidation of radio and film industries at the outset of the American engagement in World War II in the early 1940s, Los Angeles offered economic opportunities and refuge from the strife of world events. The sudden influx of artists and intellectuals from war-torn Europe fostered an unprecedented dialogue on the potential of film and radio; implicit in this dialogue was the belief that rapid advances in audio and visual technology would enable radical new approaches to the work of art. Immigrating to Los Angeles in 1936, Fischinger brought with him both the theoretical and technical knowledge of a practice broadly defined as “visual music” and laid the groundwork for aesthetic discussions on the relationship between sound and image.Footnote 8 Fischinger's notion of the “spirit inside each object” was inspired by his research in sound phonography in film. On the audio portion of a sound film a clear visual representation of sound wave structure appears; the visual nature of this phenomenon inspired numerous theories similar to Fischinger's on the indexical relationship between sound and image and its implications for a composite visual music.Footnote 9 Such technological innovations empowered composers such as Cage to explore new methods of temporal organization of sound in a tactile visual interface. The notion that percussion music represented, in Cage's own words, a “transition to the electrical music of the future,” marks a second decisive step in his early career, an idea driven by the technical assistance of Cage Sr. and the inspiration and creative support of fellow artists. Finally, Cage's work with Fischinger and his father sheds new light on the motivations for and significance of his 1940 essay “The Future of Music: Credo,” a statement that summarized rather than prophesied contemporary developments in sound recording and synthesis technologies.

“The Spirit inside Each Object”: European Precedents for “Visual Music”

Cage first encountered precedents for visual music during his travels to Europe in 1930 and 1931. The journal transition, devoted to U.S. artists living in Europe, functioned as a cultural guidebook for Americans abroad and was repeatedly cited by Cage as an important source of information and ideas.Footnote 10 Several articles, echoing the manifestos of early filmmakers and theorists such as Sergei Eisenstein, Germaine Dulac, and Dziga Vertov, extolled the revolutionary potential of the new art form of the sound film.Footnote 11 Calls within transition for experimental approaches to sound film opposed industry norms and encouraged an engagement with the materiality of the medium itself. Throughout the 1920s, Oskar Fischinger and other artists answered the calls in transition. A school of abstract film formed around several venues, particularly in Berlin, and included artists such as Viking Eggeling, Walther Ruttman, and Hans Richter.Footnote 12 In 1926 Fischinger toured with Hungarian composer Alexander László, presenting a series of Farblichtmusik (Color-Light-Music) concerts consisting of simultaneous projections of Fischinger's abstract 35 mm films, colored lights, and the color organ. Fischinger soon parted with László and continued to present multiple projection shows, which combined five 35 mm film projectors and slide projectors in one of the earliest immersive cinematic environments.Footnote 13 Works from Fischinger and others prompted a theoretical and technical debate on the implications of new developments in cinematic technology. Starting in 1930, artists and devotees convened in Berlin for annual “Farbe-Ton-Forschung Kongresse” (Color Music Congresses), organized by Dr. Georg Anschütz, featuring scholarly presentations on synaesthesia, color music, and the color organ.

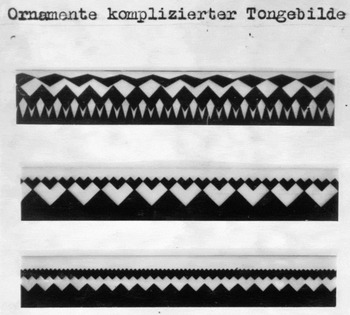

Fischinger had often strived to correlate his geometric abstractions to specific musical sounds, and his realization that these visual “ornaments” bore a substantial resemblance to the patterns generated by sounds on the optical soundtrack led to his notion of a “spirit” within each object. By drawing images directly onto the optical soundtrack, Fischinger experimented with a variety of sound shapes and their corresponding sounds. His early Ornament Ton (Ornament Sound) experiments received international press, and he noted the implications of this new technique in a widely publicized article, “Klingende Ornamente” (Sounding Ornaments). “Now,” he proclaimed, “control of every fine gradation and nuance is granted to the music-painting artist, who bases everything on the primary fundamental of music, namely the wave-vibration or oscillation in and of itself. In the process surface new perceptions that until now were overlooked and remain neglected.”Footnote 14 Fischinger converted his studio to explore this new technique, and photos of mock examples of geometric shapes were widely publicized across GermanyFootnote 15 (see Figure 1). The actual geometric shapes used in the experiments (Figure 2) produced a variety of sounds, some so disturbing that the technicians feared that it might damage their equipment.Footnote 16

Figure 1. Fischinger in Berlin studio with mock publicity Ornament Sound scrolls, ca. 1932. © Fischinger Trust, courtesy Center for Visual Music.

Figure 2. Examples of “ornaments” from Fischinger's Ornament Sound experiments, ca. 1932. © Fischinger Trust, courtesy Center for Visual Music.

Although scholars continue to debate the relationship between Fischinger's work and several contemporaries, central to the theoretical discourse of sound-on-film was the sudden realization of an entirely synthetic, virtual environment of musical space.Footnote 17 Much like the grooves of a phonographic record, the images on the soundtrack were directly linked to the original sound, and this indexical relationship was clearly demonstrated and easily understood.

There is no documentation indicating that Cage was aware of these experiments during his European travels, aside from his attendance at the Neue Musik Berlin festival in 1930, which showcased some of the earliest experiments in overdubbing techniques with phonograph records by Paul Hindemith (a close friend of Fischinger) and Ernst Toch.Footnote 18 However, when Cage returned to Los Angeles in 1931 to begin his musical training, the European avant-garde soon followed. In the increasingly tumultuous Nazi era, experimental artists flocked to the United States, particularly to the blossoming exile community surrounding the Hollywood industry in Los Angeles and the West Coast in general.

“Exiled in Paradise”: Cage and Los Angeles Émigré Culture

Cage's study abroad was cut short by the onset of the Great Depression, forcing his parents to move to an unassuming apartment in the heart of Los Angeles in an area now known as the Rampart Division. Despite these setbacks, Cage's mother Lucretia, as has been noted elsewhere, was instrumental in forming an impressive network of wealthy contacts within the blossoming émigré culture for her son. Along with other supporters, such as his aunt Phoebe James and the musician Mary Carr Moore, he quickly navigated his way among artists and intellectuals.Footnote 19 Two additional women had an equally important effect on Cage's early career: Pauline Schindler and Galka Scheyer. Pauline Schindler, former wife of architect Rudolph Schindler, kept an extensive correspondence surrounding a brief love affair with Cage in early 1935, and these letters aid in mapping out one of Cage's most productive years in Los Angeles.Footnote 20

Galka Scheyer, who would later introduce Cage to Fischinger, was the self-proclaimed West Coast representative of the “Blue Four,” a coterie of expressionist painters centered in Berlin including Lyonel Feininger, Alexej von Jawlensky, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee. Cage first met Scheyer through Pauline Schindler in February of 1935, when he visited her famous Blue Heights Drive residence to view recent works by Kandinsky and Jawlensky.Footnote 21 Cage was clearly enamored of both artists, as Scheyer later recounted, and he purchased Jawlensky's Meditation N. 160 (1934) at the “very low price of $25.00,” for which he made a down payment of $1.Footnote 22 He enthusiastically wrote a short note to Jawlensky, exclaiming, “I'm overjoyed because I've bought one of your pictures: Now it is in me. I write music. You are my teacher.”Footnote 23 Cage's rapture makes sense in the context of the specific Jawlensky “picture” he purchased. The painting was part of an extended series of more than 1,300 variations on the abstract image of a human face (Figure 3). Jawlensky called one of the first paintings in this series the Fore-Form, out of which the rest of the Abstract Heads were based, and Scheyer referred to the musical connection with Schoenberg's serial compositions in later essays.Footnote 24 Scheyer was quick to note in a letter to Jawlensky that Cage was “a very talented composer who is to be a Schoenberg student,” and she was well aware of Schoenberg's upcoming extension courses being offered at UCLA and USC.Footnote 25

Figure 3. Alexei Jawlensky, Abstract Head, Winter Ringing, 1927, oil and pencil on textured cardboard (left); Abstract Head: Life and Death, 1923, oil and pencil on cardboard (middle); Abstract Head, 1923, oil and pencil on cardboard (right). Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California, The Blue Four Galka Scheyer Collection, © 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

John Cage, Sr.'s Early Scientific Experiments

The year 1935 was a busy one for Cage. Having just returned from an intense period of study in New York with Henry Cowell and Schoenberg pupil Adolf Weiss, Cage organized a series of concerts in Los Angeles, began his studies with Schoenberg, eloped with Xenia Kashevaroff, and worked full time for his father as a research assistant.Footnote 26 Of these various activities, the last has received the least scholarly attention. The research John Milton Cage, Sr., conducted was directly related to the two economic pillars of the Southland economy: the entertainment and military-industrial conglomerates. President of Cage Submarine and Boat Company, Cage Sr.'s earliest achievements focused on submarine ventilation and propulsion technology, and he later contracted his engineering skills to several corporations, including the automobile industry.Footnote 27 In the early 1930s Cage Sr. shifted his efforts, and his focus for the next twenty years became the perfection of the cathode ray tube, whose development was essential for the practical realization of television.Footnote 28 Basing his East Coast operations in Schenectady, New York, Cage Sr. worked for General Electric until 1942, when, under the auspices of the U.S. Naval Department, his expertise was directed to the war effort.Footnote 29

Cage Sr.'s study of the fundamental properties of electron beam tubes sparked a period of intense research on electron theory. It was primarily his experimentation with cathode ray tubes that led to his interest in the contemporary debate on the nature of matter and electricity, for it was within the vacuum-sealed apparatus of a glass tube that the first scientific observations on waveforms and X-rays were observed and tested.Footnote 30 In an unpublished essay dating from around 1930, Cage Sr. explicitly rejects many current theories on electromagnetics, proposing instead a version of the “cloud” theory of electrostatic energy—essentially an extension of the long-debated “ether” theory—that attempted to account for the vast amount of empty space that rests between atomic particles and the surrounding electron field. Over the next twenty years, this hypothesis would continue to spark his scientific curiosity.Footnote 31 The cathode ray tube aided scientific investigations of electromagnetic waves beyond the visible spectrum, and Cage Sr. realized the potential of combining the peering lens of a cathode ray tube with another military technology: infrared vision. The prospect of mechanically assisted visualization of material beyond human perception was a preoccupation of Cage Sr. for some time, beginning with his interest in underwater submarine detection after the failure of his earlier projects with gasoline-powered submarine engines.Footnote 32 In 1935 Cage Sr. filed for articles of incorporation with the partnership of Los Angeles lawyer Herbert Sturdy under the appropriately punned name “Sturdy-Cage Projects, Inc.” to develop a new machine.Footnote 33 Working in the garage of the family home in Los Angeles, Cage Sr. began patent preparations for his “Invisible-Ray Vision Machine.”Footnote 34

Cage Jr. was hired by his father in March of 1935 and worked tirelessly to construct the infrared device during his early counterpoint studies with Schoenberg. With forty different claims, this patent was clearly the centerpiece of Cage Sr.'s work, with the goal of jumpstarting “Sturdy-Cage Projects, Inc.” Cage Jr. wrote to Weiss, who had developed a close friendship with Cage Sr., noting: “My father has hopes of becoming wealthy . . . you would have only to whisper a wish and it would be amplified materially.”Footnote 35 Documents Cage Jr. retained from this research reveal his extensive knowledge of electrical engineering and his deftness for scientific inquiry. As he learned, in order for an image to appear on a television screen, the electron beams emitted from the cathode-ray tube are directed through magnetic fields at the end of the cathode. To control the “sweep” of the beam, oscillators directed the electric current across the screen in rapid successive passes on the horizontal and vertical planes to form the image.Footnote 36 Cage Sr.'s device followed this principle, directing the cathode ray tube beam onto a photoreactive plate that highlighted wavelengths beyond the visible spectrum. He assigned his son to construct one version of the machine that deflected a beam of light on mirrors vibrated on two axes at right angles to one another to perform the sweep. As Cage Sr. described in the patent application, the mirrors were controlled by conventional oscillation generators, and it was his son's task to build two such devices.Footnote 37 Coincidentally, in Palo Alto, California, a young engineer by the name of William Hewlett was finishing his master's thesis at Stanford on a similar apparatus. Teaming up with David Packard, a colleague of Cage Sr. at General Electric, the Hewlett-Packard pair began manufacturing an elegantly simple version of just such an oscillator for commercial testing purposes.Footnote 38

Cage kept several working notes from the project, and in one document he sketched out a number of sound-wave structures, including a sine wave with plotted points of frequency, and a combination signal of sine and triangle waves that the frequency oscillator would have generated. The notes outline the mechanics of the scanning apparatus, but Cage noticed something else. In the margins he wrote: “Sawtooth oscillators, reflector plates in tubes” and finally, “electric musical instruments,” an idea he would return to four years later with his first electroacoustic composition, Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939).Footnote 39 Additional sketches bear a striking similarity to a Fourier analysis of a sine wave, and Cage's memory of the rotating mechanism within the cathode ray tube clearly stuck with him many years later. Discussing Rauschenberg's screen-printing works from the late 1950s, Cage recalled the parallel effect obtained by Cage Sr.'s “device made of glass which has inside it a delicately balanced mechanism which revolves in response to infrared rays,” and later made explicit reference to Fourier analysis.Footnote 40

Cage Jr. seemed to float in and out of the work with a quixotic air of curiosity. In one note to Pauline Schindler, he playfully danced around the fundamental concept of the “Invisible Ray Vision” machine with a sensual exuberance:

I am luminous. There is a marvelous extension around me like the things continents have around them in atlas maps. I am on the topmost peaks of sensitivity. I am convex and then I'm concave. I include and exclude. I simmer. I purr. I shall be fired from my job. My father's like a character out of Moliere. Stubborn, one faced like imitation-college short story. He's become an idea, a dissension, a unit molecule taking up position. But I am on top.Footnote 41

Blending technological and scientific discourse with a playful spiritual bent, this note hints at Cage's blossoming interest in an alternative artistic career. Although Cage likely did not realize it at the time, the fundamental concept behind the mirror apparatus he was assigned to construct was quite similar to the technology behind film phonography, priming him for his interaction with Fischinger the following year.

Visualizing Music: Oskar Fischinger and Cage's “Quartet”

While John and Xenia Cage settled as newlyweds in Los Angeles in 1935, Oskar Fischinger's situation in Berlin had reached the breaking point. Even though his popularity garnered him official censor permits for his films, he was forced to resort to a series of complex tactics that redefined his films as outside the purview of “abstract” art. Around the same time an agent for MGM brought several of his films to Hollywood for a test screening at the Filmarte Theater, where they were greeted with riotous approval by a large audience.Footnote 42 Paramount quickly offered a lucrative contract for a short piece to be included in their feature Big Broadcast 1937, and Fischinger arrived in Los Angeles in February 1936. Fischinger immediately encountered the usual frustrations of émigré artists attempting to assimilate into the industrial model of film production. Paramount's refusal to spend money on color film stock for Fischinger's portion of the project heightened these tensions, and he left the project by the middle of the year. Fischinger managed to get by with the help of his many friends in the émigré population, including Galka Scheyer.

In December 1936 Fischinger received a contract from MGM for an animated film, and he rented a small studio space for the animation scaffolding. Galka Scheyer introduced Cage to Fischinger sometime before March of the following year. Cage and Fischinger likely discussed percussion music prior to his apprenticeship, because he sent Fischinger a complimentary ticket to a lecture on percussion music at the home of bookbinder and musician Hazel Dreis in March 1937. Cage's note on the ticket (Figure 4) promised a performance of several compositions on new percussion instruments by the “John Cage Group.”Footnote 43

Figure 4. John Cage, postcard invitation to Oskar Fischinger, 1937. Fischinger Collection, Center for Visual Music.

“Mr. Fischinger and Friends” [Herr Fischinger und Freunde]; “As a guest” [als Gast]; “brand new instruments, various compositions by other composers!” [ganz neue [I]nstrumenten, verschiedene Kompositionen, von anderen Komponisten!]

In early 1937 MGM contracted Fischinger to complete an animated short entitled An Optical Poem, and in hope of a possible future commission, or perhaps out of his own interest in sound phonography, Cage apprenticed briefly for the project (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Fischinger in studio working on An Optical Poem, Hollywood, Calif., 1937. © Fischinger Trust, courtesy Center for Visual Music.

An Optical Poem was shot using stop motion animation; dozens of individual paper cutouts of geometric shapes were arranged on the shooting stage and then repositioned after each frame of film was exposed. To outline the animation, Fischinger sketched a graphic-temporal notation of the movement of individual figures across the screen (Example 1). He used a large scroll of graph paper, where the horizontal plane represented the individual frames. The graph paper was subdivided into individual lines where Fischinger sketched the general movement of the figures over time. The curved lines and straight lines in the example specify a few of the many movements across the screen of the paper cutouts.

Example 1. Oskar Fischinger, graphic animation sketch for An Optical Poem. © Fischinger Trust, courtesy Center for Visual Music.

With these details one can get a sense of the animation process Cage witnessed. Fischinger knew the specific attack points in which each image would appear. In later sections a myriad of figures move across the screen, each corresponding with different attack points, and the coordination of each of the figures within the set was a complex endeavor. As Cage recalled later in life, during his apprenticeship Fischinger looked on, cigar in hand, in the corner of the studio while Cage carefully moved the large paper cutouts of colored geometric shapes a few fractions of a millimeter for each successive frame shot with a large feather attached to a stick. At one point Fischinger fell asleep, dropping ashes from his cigar into a pile of papers and rags and starting a small fire. Frightened, Cage rushed to splash water on the flames, dousing Fischinger and the equipment in the process.Footnote 44 Years later, Cage wrote a mesostic in memory of the encounter:

According to all surviving documentation, Cage's work lasted no more than a few days, and likely ended after the fire incident.

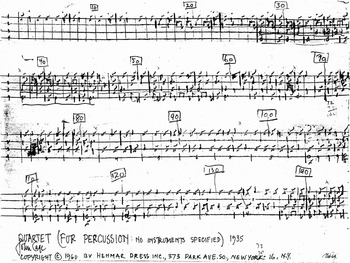

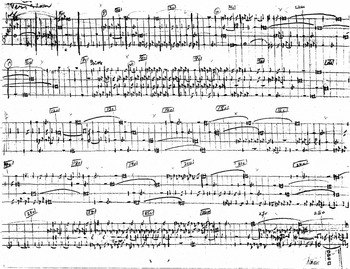

Despite the brevity of Cage's apprenticeship, the influence of Fischinger's animation method can be seen in the manuscript for Cage's first percussion work, Quartet, which displays many similarities to Fischinger's graphic sketches. Although Cage dated the work to 1935—before his first encounter with Fischinger—there is reason to think the date incorrect.Footnote 46 Cage's only other percussion piece from his Los Angeles years, Trio (1936), used conventional notation and was written for specific instruments, whereas his Quartet does not specify instrumentation and is written in a unique graphic notation. Each movement of the manuscript is written in a progressively strict type of proportional notation, beginning with the first movement in loosely drawn lines (Example 2a), followed by the second movement, which attempts to align measures among systems (Example 2b), followed by the third movement, “Axial Asymmetry,” with a strict uniformity of 60 bars per system (Example 2c), and culminating with the final movement, written on graph paper (Example 2d). With this evidence in mind, I would argue that Cage was attempting to create a score that would align with Fischinger's animation method. Given the timing of Cage's interaction with Fischinger, I suggest that the Quartet was in fact composed in 1937.

Example 2a. John Cage, Manuscript for Quartet for Percussion, Movement I, ca. 1937. John Cage Music Manuscript Collection, New York Public Library, Music Division, JPB 95–3, Folder 175. Used by permission of the John Cage Trust.

Example 2b. John Cage, Manuscript for Quartet for Percussion, Movement II, ca. 1937. John Cage Music Manuscript Collection, New York Public Library, Music Division, JPB 95–3, Folder 175. Used by permission of the John Cage Trust.

Example 2c. John Cage, Manuscript for Quartet for Percussion, Movement III, “Axial Symmetry,” ca. 1937. John Cage Music Manuscript Collection, New York Public Library, Music Division, JPB 95–3, Folder 175. Used by permission of the John Cage Trust.

Example 2d. John Cage, Manuscript for Quartet for Percussion, Movement IV, graphic notation details, ca. 1937. John Cage Music Manuscript Collection, New York Public Library, Music Division, JPB 95–3, Folder 175. Used by permission of the John Cage Trust.

Cage's blocking of individual instruments bears a distinct similarity to the animation “staging” in Fischinger's graphs, and it is here that the notion of a “spirit inside each object” has clear scientific and practical artistic implications. Cage had discovered the specific scientific nature of sound-wave structure through film phonography and scientific research for his father, giving him a sense of the indexical relationship between sound and object. In Fischinger's studio he witnessed a miraculous blending of scientific precision with brilliant artistry in the synchronization of sound and image over time. Thus, in just one short encounter, Cage for the first time noticed the connection between sound, object, and duration.

There is no documentation indicating that Cage had further contact with Fischinger until the fall of 1940. Cage Sr. continued with his research on electron beam tubes, research Cage Jr. assisted on until his departure in 1938 to teach at the Cornish School in Seattle.Footnote 47 During the same period, Fischinger reunited with his friend Leopold Stokowski at Paramount and later contended that it was during this time that he first proposed to Stokowski many of the animation ideas that would eventually become Walt Disney's feature-length animated film Fantasia (1940).Footnote 48 After completing An Optical Poem in early 1938 to critical acclaim, Fischinger spent much of the fall in New York, where he came into contact with the Baroness Hilla Rebay, who, with the generous resources of Solomon R. Guggenheim, was laying the foundation for the Museum of Non-Objective Art, later to be renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Rebay encouraged Fischinger to live a bohemian lifestyle in New York by leaving his family and living at her estate, but Stokowski and Hollywood soon called him back to work, this time at Disney studios as a “Motion Picture Cartoon Effects Animator” for the recently greenlighted Fantasia.Footnote 49 Fischinger's ideas did not sit well with Disney's industrial animation methods and were repeatedly dismissed as too “abstract.” Frustrated with the lack of artistic freedom at Disney, Fischinger left the project and requested his name be removed from it. Meanwhile, Stokowski had impressed Disney enough with his ideas for stereophonic sound that they decided to create a highly advanced recording method for the orchestral score to Fantasia: the Fantasound system. This eight-channel system utilized film phonographs to capture the full orchestral texture of the orchestra, and Stokowski worked closely with Disney throughout the process. In order to test the system in theaters, Disney purchased the first eight Variable Frequency Oscillators offered by Hewlett-Packard—the same unit similar to the one manufactured by Cage Jr. just five years earlier—thus bringing the critical initial profits to their new enterprise.Footnote 50

The Future of Music

By 1940 Cage's experiments with electroacoustic music had led to a new focus on the bridge between percussion music and an electronic “music of the future,” leading eventually to the essay “The Future of Music: Credo.” In recent years this essay has been the subject of several critical investigations, the most notable being the discovery by Leta E. Miller that the essay was not delivered until early 1940, in contrast to the 1937 date in the published version found in both the liner notes for Cage's Twenty-Five-Year retrospective concert recording in 1958 and in the 1961 publication of Silence.Footnote 51 Cage's manifesto thus came after his initial investigations in electroacoustic composition at the Cornish School in Seattle and should be viewed more as a summary rather than a prophecy. In addition, the various observations in the essay on contemporary technological advances were the result of Cage's extensive research for a letter-writing campaign in 1940 to establish a center for experimental music.

As many scholars have noted, the text layout of the printed edition of “The Future of Music: Credo” mimics Luigi Russolo's Futurist manifesto “L'arte dei rumori” (1913). In Russolo's text two separate narratives are juxtaposed: a shorter manifesto written in capital letters set against commentary with regular punctuation. Cage's essay follows the same format by offsetting the primary credo, written in capital letters, with commentary on the various uses of music synthesis technologies and electric musical instruments such as the theremin, solovox, and novachord.Footnote 52 Cage acknowledged the precedent of Russolo's manifesto and went so far as to commission his wife Xenia and another member of their percussion ensemble, Renata Garve, to translate the essay.Footnote 53 Cage's explicit division of the text, following Russolo, also sheds light, however, on the origin and purpose of the commentary.

The two surviving manuscripts for the essay, a handwritten draft with the date 1940 and an undated typescript draft, contain only the primary capitalized text with several stricken passages. Although the typescript version of the essay does contain footnotes for the appropriate interjections in the primary text, there are more footnote numbers than there are comments in the printed edition. In the manuscript Cage placed a total of twenty-six footnotes compared to only eight text interjections in the published edition, leading one to assume that Cage had considered several alternate versions of the text.Footnote 54 There are no other complete versions of the essay except for the corrected typescript submitted to Wesleyan University Press in 1960.Footnote 55 However, numerous documents in the voluminous “ephemera” files in the John Cage Collection at Northwestern University contain similar versions of the supplemental text. With this evidence in mind, it could reasonably be argued that the essay itself represents a culmination of a series of research projects and proposals Cage had assembled between 1938 and 1940 in anticipation of establishing a center for experimental music.Footnote 56 These materials highlight Cage's knowledge of contemporary developments in sound recording and synthesis technologies, and the closest influence on, and instigator of, this research was undoubtedly his father Cage Sr., whose patent research during the time mirrored many of the same technologies.

After the spring semester in 1940 Cage resigned from the Cornish School and began a furious letter campaign to drum up funding for a center for experimental music. The material surviving from this project comprises the majority of the “supplemental” commentary to the capitalized credo. Later that year Cage taught at the summer session at Mills College, where he had ample opportunity to work with the former Bauhaus director László Moholy-Nagy.Footnote 57 Cage's dialogue with Moholy-Nagy on Bauhaus-derived theories led to a more nuanced perspective on the theoretical implications of sound synthesis and recording technology, and concepts from his seminal textbook on Bauhaus theory, “The New Vision,” remained central to Cage's emerging thesis on the use of technology in composition.Footnote 58 The six-week summer session at Mills attracted national attention, adding momentum to Cage's fundraising campaign.

However, by August 1940 he found himself again unemployed, and he spent a good part of the fall in Los Angeles working on several research projects for Cage Sr. Ever willing to help his son in the pursuit of new musical resources, Cage Sr. devised a primitive frequency oscillator of his own that August with the help of engineers at the Federal Radio Co., so that he might use the instrument in a similar manner to the frequency records from Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939). As Cage described it in a letter to Henry Cowell, the instrument would be able to vary the waveform, frequency, and amplitude, as well as do “some very interesting things with duration”; unfortunately, no other information survives from this project.Footnote 59 From the description, it may have been an instrument like the one devised for the “Invisible Ray Vision System,” and quite similar to the affordable version offered by Hewlett-Packard. Aware of the innovative technology emerging from Fantasia, Cage rather ambitiously attempted to set up meetings with Leopold Stokowski and Walt Disney to propose a center for experimental music.Footnote 60

Throughout August and into September Cage continued with library research on new developments in sound synthesis. He submitted his first Guggenheim fellowship application with the hope of establishing a center at Mills College for “research in the field of sound and rhythms formerly not considered musical,” with the ultimate goal of creating “electric instruments capable of producing any desired frequency in any desired duration, amplitude, and timbre.”Footnote 61 In the application Cage reworked the credo from the “Future of Music” essay in the personal statement, and compiled a bibliography of relevant books and articles on electrical and synthetic music.Footnote 62 It is clear from the bibliography that Cage was interested in the potential for sound phonography experimentation. One source, a highly technical volume from 1935 by John Mills entitled A Fugue in Cycles and Bels, described in detail several of the leading innovations Cage was interested in, including a thorough examination of sound synthesis techniques in film. Mills describes in detail the process for editing sound waves and suggests that “libraries of templates could be constructed covering all desired combinations of tones.”Footnote 63 Situated in the heart of the film industry, Cage immediately set out to find a facility that could assemble such a library. Cage was tipped off by a September article in the LA Daily News about composer Hanns Eisler's progressive film scores for MGM, and he sought out the head engineer for the studio, Douglas Schearer, who gave him a brief tour of the facilities. Here he was able to witness firsthand the complex sound editing techniques for feature films.Footnote 64 Cage mentioned this occasion in his 1948 lecture at Vassar College, “A Composer's Confessions,” noting that with this equipment “a composer could compose music exactly as a painter paints pictures, that is, directly.”Footnote 65 The “footnoted” portion of Cage's credo contains several passages describing this use of film phonography, such as the often-cited observation: “Every film studio has a library of ‘sound effects’ recorded on film. With a film phonograph it is now possible to control the amplitude and frequency of any one of these sounds and to give to it rhythms within or beyond the reach of our imagination. Given four film phonographs, we can compose and perform a quartet for explosive motor, wind, heartbeat, and landslide.”Footnote 66

New to this portion of the essay, however, is the introduction of the other key element to Cage's thesis: the term, “organization of sound.” The origins of this term resulted in Cage's first interaction with composer Edgard Varèse in Los Angeles. Ironically, just as Cage left for Seattle in 1938, Varèse arrived in Hollywood with the hope of finding interest in his large-scale multimedia work Déserts. As Olivia Mattis discovered, Varèse's initial ideas for the work emerged from another uncompleted project, Espace, which was part of a utopian vision of an all-encompassing artwork that would combine theater, cinema, and light projections. The final version of Déserts completed in 1954, which included the first demonstration of “organized sound” on magnetic tape, was only a small fraction of the initial multimedia version that emerged from his mystical revelations in the deserts of the Southwest.Footnote 67 Varèse was already familiar with Fischinger's earlier films from Europe, and like Fischinger, he struggled to find support for his project, which was largely ignored by the Hollywood industry.Footnote 68 In 1940 Varèse introduced Cage to the ideas behind “organized sound,” a theory he formally outlined in his published essay in December of the same year “Organized Sound for the Sound Film,” a document that Cage typed out word-for word for his own bibliography.Footnote 69 In early incarnations of the term, Varèse was primarily concerned with the creative uses of sound effects and sound design in film as a way of effectively articulating narrative, but he eventually adopted a more encompassing idea of sound organization following the invention of magnetic tape in the postwar period. In the immediate context of their discussions, however, Cage found a fitting description for his essays that he appropriated in a series of articles.Footnote 70 Cage's dialogue in 1940 with Los Angeles composer and concert impresario Peter Yates has been well documented in recent years, particularly the debate surrounding the term “Organized Sound” in a short article drafted by Cage and edited by Yates for the magazine California Arts and Architecture, eventually titled “Organized Sound: notes on the history of a new disagreement: between sound and tone.”Footnote 71 In the letter to Yates Cage noted for the first time the Fischinger anecdote, and the rekindling of this connection to his percussion music likely resulted from a meeting Cage had with Fischinger in the fall of 1940. While touring Los Angeles with several records of his percussion works, Cage visited Fischinger and played some examples, discussing once again the possibility of a film commission. A number of graphs similar to the one used in An Optical Poem in the Fischinger Collection at the Center for Visual Music indicate percussion sounds, although it is unclear from the surviving fragments the specific piece of music in mind.

In the coming years, after Cage and his parents moved away from Los Angeles permanently, Fischinger did not lose sight of his potential Cage film. After reading the impressive Life magazine review of Cage's February 1943 percussion concert at the Museum of Modern Art, Fischinger wrote to Cage, in care of the museum, requesting his newest recordings of percussion music in order to include the commission as part of a new application for Guggenheim support later that summer.Footnote 72 In the letter, Fischinger noted, “I have a clear feeling how fertile, expressive, how rich in color your percussion music is, especially on the screen. Please help me to get your music on the screen, and please do everything possible because it is so important.”Footnote 73 However, Fischinger's struggles with a severely limited budget and his constant personal and artistic battles with Hilla Rebay cut this project short, and it is doubtful that Cage ever received the letter.

As these documents reveal, Cage's anecdote about Oskar Fischinger and the “spirit inside each object” provides insight into several aspects of Cage's emerging ideas on the scientific nature of music. As Cage repeatedly stated in his writing, percussion music was an important transition to the electric music of the future, where recording and synthesis technology required a new approach to the compositional process. The ability to visually interpret sound-wave structure in film phonography provided a tactile medium for creating a time-based structure of sound organization and required new notational approaches in order to coordinate sound and image. As an important by-product of Cage Sr.'s electrical engineering projects, the simple audio frequency oscillator would later form the basis of complex sound synthesis, and the close pairing between industrial and artistic application of technology would continue to be a driving force in Cage's application of new technological resources for experimental music in the postwar period. Finally, as David Nicholls and others have proposed, it seems fitting to view Cage's seminal essay “The Future of Music: Credo” not necessarily as a definitive text (because none survives), but rather more as a summary statement of contemporary developments culled from Cage's own efforts to establish an experimental music center. Reading this document as two different items, the shorter “Credo” and the detailed examples in the “footnoted” text, makes sense in the chronology of events that unfolded in Cage's career in 1940. The second portion contains many similarities to Cage's various project proposals, and it could even be argued that the additional text functioned as a patent “claim” worded with the legalese Cage was intimately familiar with, a strategy he explicitly used in his later essay “Forerunners of Modern Music” (1949).

In a fitting postlude to Cage's early career, in 1976 Cage's ex-wife Xenia hinted at the long-term ramifications of Cage's time in Los Angeles and his patent research for his father. After attending the controversial premiere of Cage's Apartment House 1776 and Renga, she passed along the following note: “I guess I am no different from you in that I didn't know what to expect. I found it dazzling, positive, full of wit and good humor. I think you have achieved what your dear father always hoped—to see through fog.”Footnote 74

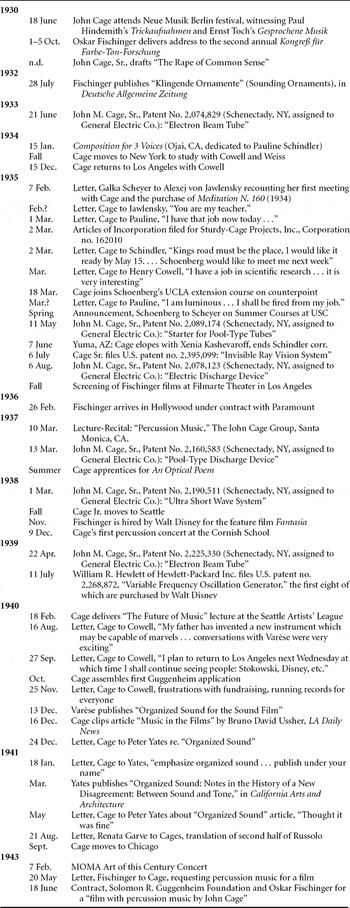

Appendix. Chronology